- 1Department of Psychology, University of Kaiserslautern-Landau, Landau, Germany

- 2Human Ecology Programme, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 3Department of Architecture and Built Environment, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

The consequences of climate change are becoming increasingly visible. Recent research suggests that people may respond to climate change and its predicted consequences with a specific anxiety. Yet, little is known about potential antecedents of climate anxiety. The current study aimed to understand the contribution of climate risk perception to climate anxiety, along with nature-connectedness, self-efficacy, and political orientation. With a sample of 204 German adults, we assessed these constructs together with environmental policy support that may result from climate anxiety. Stronger risk perception and a left political orientation predicted climate anxiety. Self-efficacy and nature connectedness, however, were unrelated to climate anxiety. In line with previous studies, climate anxiety correlated positively with environmental policy support but did not predict environmental policy support when controlling for climate risk perception. We discuss results with regard to further developing the concept of climate anxiety and its dynamics and suggest directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the severe transformations within our planetary systems (Steffen et al., 2015), with detrimental consequences for biodiversity and human health, to name a few (IPCC, 2021). Consequently, people may feel a range of uncomfortable or even disturbing emotions (Albrecht, 2012; Pihkala, 2022), such as climate anxiety (Pihkala, 2020; Ojala et al., 2021; Wullenkord et al., 2021). Climate anxiety refers to an “anxiety which is significantly related to anthropogenic climate change” (Pihkala, 2020). There is a general consensus in the literature that climate anxiety is not pathological but “may be an adaptive, reasonable response to an existential threat” (Hogg et al., 2021; Kurth and Pihkala, 2022). Nevertheless, for some people climate anxiety may be so severe that it is associated with impairments in daily functioning (Cunsolo et al., 2020; Heeren et al., 2022).

With this uptake in research on climate anxiety, the current study set out to further understanding of the foundations of climate anxiety and its manifestation in the form of impairments in daily life. Specifically, we sought to shed light on relations between climate anxiety and psychological constructs that may be particularly relevant drivers of climate anxiety, and relations to pro-environmental behavior. To do so, we assessed the perceived risk climate change poses, people's connectedness to nature, their self-efficacy beliefs, and their political orientation.

1.1. Predicting climate anxiety

Empirical research assessing the antecedents of climate anxiety is scarce. Recently, a few conceptual (Crandon et al., 2022) and empirical studies with mixed results have emerged (e.g., Wullenkord et al., 2021; Whitmarsh et al., 2022) that contribute to a more nuanced understanding of climate anxiety. Building upon these studies, we argue that the perception of climate risk may be an important, yet uninvestigated key to understanding climate anxious responses. We therefore assessed climate risk perception with other known predictors to test its unique contribution toward climate anxiety.

Climate risk perception. Risk perception refers to “the process of discerning and interpreting signals from diverse sources regarding uncertain events, and forming a subjective judgement of the probability and severity of current or future harm associated with these events” (Bradley et al., 2020). In line with this conceptualization, appraisal theories of emotion (e.g., Lazarus, 1991) propose that the experience of anxiety can result from perceptions of such potentially threatening events. Being regularly confronted with threatening information about the climate crisis likely affects perceptions of climate risk. Climate risk perceptions are associated with negative affect (Leiserowitz, 2006) and predict pro-environmental behaviors (see also Lee et al., 2015). As Bradley et al. (2020) argue, risk perceptions may causally affect such pro-environmental behaviors through increased efficacy beliefs. Accordingly, being exposed to climate change impacts in the media (Ogunbode et al., 2022) and seeking climate change information (perhaps as a proxy of perceived climate risk) is related to climate anxiety (Whitmarsh et al., 2022). Therefore, we assume that higher climate risk perceptions relate to stronger climate anxiety (H1a) and support for climate policies (H1b).

Nature connectedness. Nature connectedness entails the affective experience of the integral connection between nature and the self (Mayer and Frantz, 2004). While some recommend fostering nature connectedness as a coping strategy for dealing with climate anxiety (Baudon and Jachens, 2021), feeling such a connection with nature may actually increase people's sensitivity to the potential loss of nature as something valuable (see also Whitmarsh et al., 2022). It may influence perceptions of already existing degradation of nature due to climate change, which may exacerbate feelings of climate anxiety. These conceptual thoughts are mirrored in tentative evidence for a positive relationship of nature connectedness with climate worry (Galway et al., 2021; Curll et al., 2022) and climate anxiety (Whitmarsh et al., 2022). The existing studies operationalized nature connectedness as a partially cognitive construct, rather than as the affective construct that Mayer and Frantz (2004) propose. Nevertheless, we assume similar relations of climate anxiety with the affective experience of nature connectedness and expect that stronger nature connectedness relates to stronger climate anxiety (H1c).

Self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to the belief that one's own actions can contribute to reaching specific goals (Bandura, 1997). A plethora of studies in the environmental domain suggest that self-efficacy can motivate pro-environmental action (Jugert et al., 2016; Reese and Junge, 2017; Hamann and Reese, 2020; Hamann et al., 2023). As the general conviction of controllability (i.e., that one can constructively cope with problems), self-efficacy may entail lower climate anxiety, because anxiety is often characterized by feelings of uncontrollability (Lazarus, 1991). In fact, in a recent study, climate anxiety was positively related to competence need frustration but not satisfaction, a concept similar to self-efficacy (Wullenkord et al., 2021). Furthermore, self-efficacy can buffer mental distress (e.g., Shahrour and Dardas, 2020). We therefore assume that self-efficacy relates to weaker climate anxiety (H1d).

Political orientation. Political orientation is a crucial predictor of climate change beliefs and pro-environmental actions (e.g., Häkkinen and Akrami, 2014). For example, the more left political orientation people report, the more strongly they are concerned about anthropogenic climate change (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2022). It is likely people on the left of the political spectrum report stronger climate anxiety. In fact, Wullenkord et al. (2021) found a weak but statistically significant relation between both variables (while also identifying more complex relations with indicators of right-wing ideology). We therefore expect that the more left people self-indicate their political orientation, the stronger their climate anxiety (H1e).

1.2. Relations of climate anxiety and climate action

Climate anxiety as a “practical anxiety” (Kurth and Pihkala, 2022) may trigger problem-focused coping with climate change and foster pro-environmental behavior and climate action. Indeed, climate anxiety has been found to be associated with pro-environmental intentions and climate policy support in Germany (Wullenkord et al., 2021), general pro-environmental behavior and climate activism across 28 countries (Ogunbode et al., 2022), climate activism in the US (Schwartz et al., 2022), and “green behaviors” in the UK (Whitmarsh et al., 2022). However, findings are inconclusive [e.g., absence of a correlation with meat consumption in the UK (Whitmarsh et al., 2022) and general pro-environmental behavior in the US (Clayton and Karazsia, 2020)]. One particularly relevant behavior for systemic change is policy support. Based on findings that stronger climate risk perception and climate policy support are related (Schwartz et al., 2022) and that climate anxiety and climate policy support correlated positively in a German sample (Wullenkord et al., 2021), we assume that stronger climate anxiety relates to stronger support for environmental policies (H2).

1.3. The present study

The present study aims at furthering the understanding of climate anxiety. More specifically, its primary novel contribution lies in investigating the predictive power of climate risk perceptions on climate anxiety, along with other predictors, and elucidating relations with environmental policy support. To this end, we assessed measures of climate anxiety, climate risk perception, nature connectedness, self-efficacy, political orientation, environmental policy support, age, and gender. Beyond the derived hypotheses, we explored which of these variables are most predictive for the experience of climate anxiety, controlling for age and gender (assuming that young people (Crandon et al., 2022) and women (Wullenkord et al., 2021) report higher climate anxiety]. Since this is one of the first studies that empirically addresses a set of different predictors, we refrain from specific hypotheses about individual contributions. Furthermore, we explore the predictive power of climate anxiety for policy support, in a model that includes all assessed variables as predictors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

A sample of N = 204 German-speaking participants (139 women, 62 men, 1 diverse, 2 without indication, Mage = 30.95 years, SDage = 14.09) completed the questionnaire, hosted on the online survey tool SoSci survey (Leiner, 2020). Participants were formally well-educated (44.6% high-school degree, 12.7% bachelor's degree, 15.7% master's degree, 7.8% PhD; 19.2% other). The study was advertised as a study on perceptions of and responses to climate change and was distributed through various channels such as the first author's university's mailing list and social media. After fully consenting to study information and data protection policies, participants responded to the actual questionnaire.

2.2. Materials

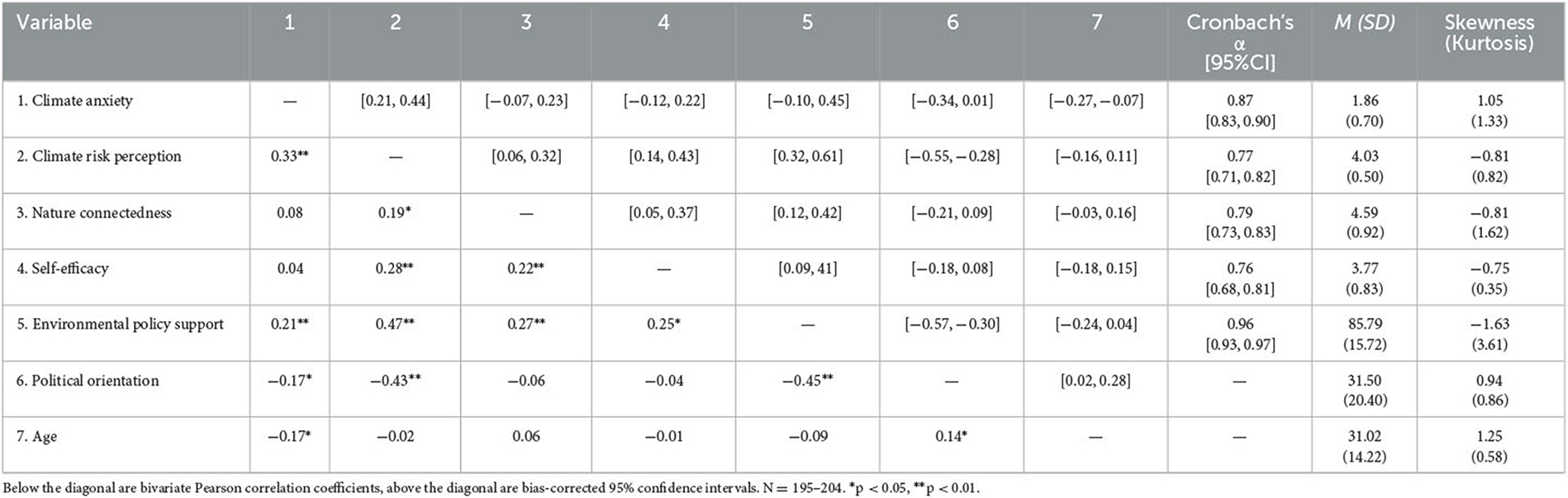

If not otherwise indicated, we used Likert scales ranging from 1 (“totally disagree”) to 5 (“totally agree”). When no validated translations existed, we translated the materials ourselves using back-translation by two independent researchers. Table 1 displays psychometric properties.

Climate anxiety. We measured impairment due to climate anxiety with the 13-item validated German translation (Wullenkord et al., 2021) of the climate anxiety scale (Hamann et al., 2023). Following the validation study (Wullenkord et al., 2021), we used only 12 items and analyzed the construct on one factor, rather than the originally proposed two factors.1

Climate risk perception. We measured climate risk perception with a nine-item risk perception scale (Leiserowitz, 2006) (own translation). Depending on the items, response options ranged from “not at all” (= 1) to “very much” (= 5), or from “not likely at all” (= 1) to “very likely” (= 5).

Nature connectedness. We measured nature connectedness with 12 items of the state measure of nature connectedness (Mayer et al., 2009) (own translation), using a 7-point Likert scale.

Self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was measured with four items (Heath and Gifford, 2006) (own translation).

Political orientation. We measured political orientation on a left–right dimension measure (Wullenkord et al., 2021), using a slider-bar ranging from 0 (left) to 100 (right). This means that lower values indicate self-positioning as “rather left-wing” and higher values indicate self-positioning “rather right-wing.”

Environmental policy support. We measured environmental policy support with a set of seven items that ask people to express their agreement with two opposing policies that are placed at the polar ends of a 100-point slider-bar (Drews and Reese, 2018).

2.3. Data preparation and statistical analysis

We used SPSS version 26 to perform statistical analyses. According to G*Power (Faul et al., 2007), a sample size of N = 98 was required to detect a medium sized regression effect for predicting climate anxiety from the proposed predictors, assuming 1-β = 0.80 and α = 0.05. To predict policy support from the proposed predictors and climate anxiety, given the same parameters, a sample size of N = 103 was required. Prior to data analysis, we examined variables for accuracy of data entry and missing data.

Before conducting the multiple regression analyses, we first tested for outliers (using Mahalanobis distance), multicollinearity (using the variance inflation factor, VIF), and heteroscedasticity (using scatter plots and the modified Breusch–Pagan-Test).

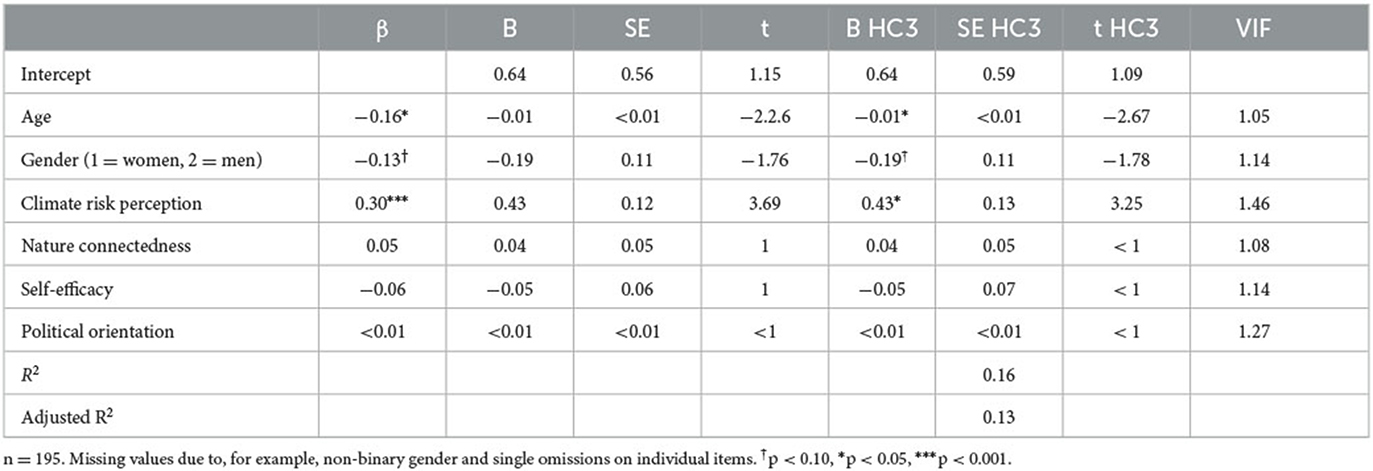

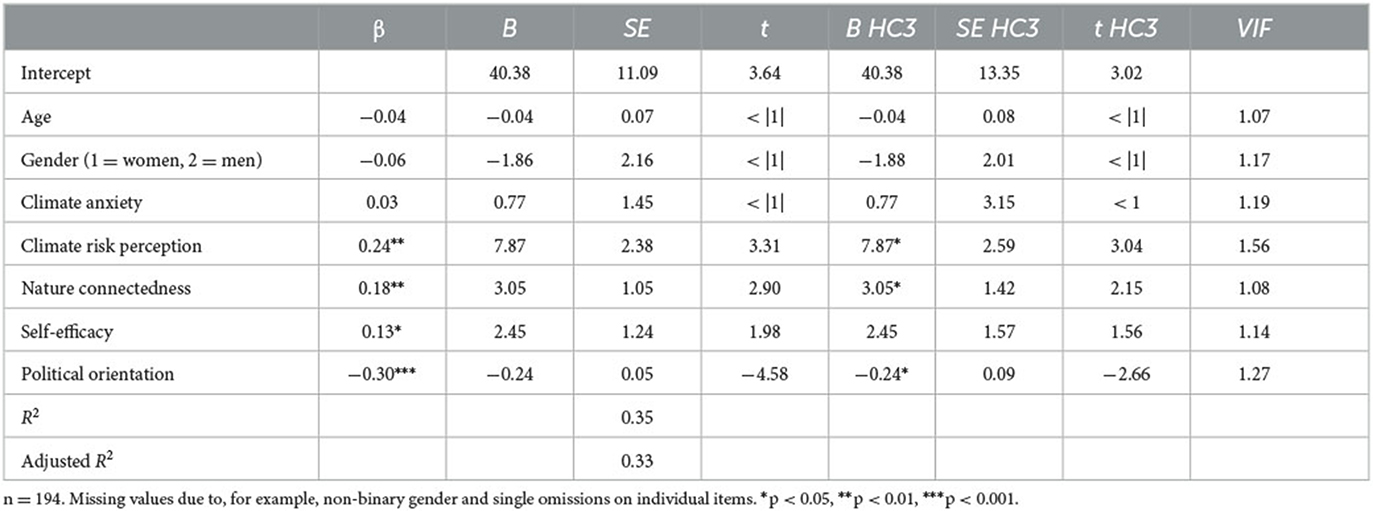

According to Mahalanobis distance, there were no outliers (p < 0.001 for both regressions). There was no multicollinearity, as can be seen in Tables 2, 3: The VIF was close to one for all analyses, and thereby much lower than the threshold of 10. For both regression analyses, we detected heteroscedasticity (i.e., significant Breusch–Pagan-test and through visual inspection of the residual plots) so that we also estimated standard errors with the robust HC3 estimator.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of findings

The summary of characteristics of our main variables are displayed in Table 1. As can be seen in Table 1, climate anxiety was relatively low in our sample (95%CI [1.76–1.95]), while participants reported high levels of risk perceptions (95%CI [3.98–4.21]), relatively high nature connectedness (95%CI [4.46–4.73]), relatively high self-efficacy (95%CI [3.67–3.90]), a rather left political orientation (95%CI [28.86–34.04]), and rather strong policy support (95%CI [83.52–88.02]).

Climate anxiety correlated positively with perceived climate risk (supporting H1a) and policy support (supporting H2) and negatively with (right-wing) political orientation (supporting H1e). It neither correlated with nature connectedness nor self-efficacy (not supporting H1c and H1d).

3.2. Predicting climate anxiety

To assess the contributions of the potential antecedents in explaining variance in climate anxiety, we conducted a multiple regression analysis with climate anxiety as dependent variable, and perceived climate risk, nature connectedness, self-efficacy, and political orientation as independent variables. Age and gender served as control variables. The overall model explained 16% of the variance in climate anxiety [F(6, 188) = 5.92, p < 0.001, Table 2]. Perceived climate risk was the strongest predictor, such that higher perceived climate risk predicted higher climate anxiety. Age (and descriptively) gender were additional predictors of climate change anxiety such that younger participants and women indicated stronger climate anxiety. Nature connectedness, self-efficacy and political orientation were non-significant in the model. Robust standard error estimates revealed the same conclusion.

3.3. Predicting policy support

To assess the contributions that the potential antecedents and climate anxiety could make in explaining variance in policy support, we conducted a multiple regression analysis with policy support as dependent variable and climate anxiety, perceived climate risk, nature connectedness, self-efficacy, and political orientation as independent variables. Age and gender served as control variables. The overall model explained 35% of the variance in environmental policy support [F(7, 186) = 17.05, p < 0.001, Table 3]. Political orientation was the strongest predictor of environmental policies, such that the more left political orientation participants reported, the stronger their policy support (supporting H1b). With a similar effect size, stronger perceived climate risk and higher nature connectedness predicted stronger policy support. Self-efficacy was also positively related to policy support. All other relations were non-significant. Robust standard error estimates come to the same conclusion, with the exception that the relation between self-efficacy and policy support was now non-significant.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that climate risk perception represents a strong and distinct predictor of climate anxiety. This relation remained significant even after controlling for potentially substantial covariates: nature connectedness, self-efficacy, political orientation, age, and gender. This indicates that risk perception may explain a large amount of variance in climate anxiety, and suggests that the cognitive profile of climate anxiety in fact revolves around notions of threat, as suggested by appraisal theories of emotion (e.g., Lazarus, 1991). Furthermore, it seems that positive relationships between information seeking and climate anxiety (Whitmarsh et al., 2022) and exposure to information about climate change impact and climate anxiety (Ogunbode et al., 2022) might be mediated by risk perception. Future research should investigate this proposition.

Regarding the relation between climate anxiety and environmental policy support, the evidence is inconsistent. While we replicated previous findings suggesting a correlation (e.g., Wullenkord et al., 2021), the relation was not significant in the regression model, probably due to uncovered mediation effects that would require experimental analysis. Previous inconsistent findings of the association of climate anxiety and climate action (e.g., Clayton and Karazsia, 2020; Whitmarsh et al., 2022) indicate that there is a need to understand the subtleties in the climate anxiety construct. In fact, it remains unclear under which circumstances climate anxiety may be a so-called “practical anxiety” (Kurth and Pihkala, 2022), and when it might be associated with inaction. Possibly, the impairment-focused climate anxiety scale may not be suitable for assessing practical, coping-oriented anxiety (Pihkala, 2021). Furthermore, there are theoretical considerations about potential moderators of climate anxiety effects (i.e., factors that ease or hamper action as a function of climate anxiety, such as attachment to places, communities, or use of media (Crandon et al., 2022), empirical evidence remains scarce.

Interestingly, and opposing our hypothesis, we found no relationship of nature connectedness and climate anxiety. This suggests that relations are likely more complex than a simple positive or negative relationship. Indeed, some evidence suggests that nature connectedness is more associated with wellbeing outcomes in people who are less engaged with climate change (Whelan et al., 2022). For those, feeling connected with nature may induce positive feelings of restoration or perhaps provide refuge from problems in everyday life. For those strongly engaged with climate change, nature connectedness may act in an opposite direction, inducing more anxiety through increased perceptions of threat or anticipated loss, as well as increasing goal relevance (Hickman, 2020). Future research should investigate how nature connectedness might influence the appraisal pattern of climate anxiety and what consequences fostering nature connectedness may have on both emotional wellbeing and associated stewardship behavior in times of environmental crisis (Crandon et al., 2022; Larson et al., 2022). There are possibly different relations with different aspects of nature connectedness (such as identifying with the environment or seeing nature and the self as truly interconnected) (Clayton et al., 2021).

Furthermore, we found no relationship between self-efficacy and climate anxiety. This may appear, somewhat surprising, given that we used efficacy items that were directly related to people's sense of efficacy in the climate domain (Leiner, 2020). Possibly, the items were too broad and unspecific (e.g., “There are simple things that I can do that will have a meaningful effect to alleviate the negative effects of global warming”) to connect them to individual anxiety or functional impairment. However, given that responses to global environmental crises require larger-scale systemic change (rather than merely individual behavior change) and collective, group-based efforts, it is likely that self-efficacy has its limits to predict climate anxiety. Specifically, we believe that collective representations of the self (e.g., in terms of identifying with specific groups or movements) may result in stronger motivation to act through higher collective efficacy beliefs and salient social norms (Fritsche et al., 2018). In fact, such efficacy beliefs and joint action can bolster feelings of being moved and empowerment that individual actions can hardly satisfy (Bamberg et al., 2018; Landmann and Rohmann, 2020). Furthermore, systemic interactions between societal layers and individual emotional responses and actions are increasingly acknowledged but need further exploration (Hamann et al., 2021; Wullenkord and Hamann, 2021; Chater and Loewenstein, 2022). Another reason might be that some people may manage to maintain high levels of self-efficacy in the face of high anxiety—perhaps because they have more psychological resources to draw upon [such as meaning-focused coping strategies as proposed by Ojala (2013)] —while others' self-efficacy may decrease. In the future, person-centered analyses could help shed light on those potential relations.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

While the current study sheds light on some psychological constructs that predict climate anxiety, it is limited to its homogeneous convenience sample of well-educated adults in the Global North. Future studies should explicitly address more heterogeneous and diverse samples (for an attempt, see Heeren et al., 2022). Furthermore, our study is cross-sectional—while we find theoretically derived relations between risk perceptions and climate anxiety, we cannot draw causal inferences. Future studies should systematize the study of climate anxiety and shed light on causal relations, using ecologically valid measures and constructs, to derive recommendations for coping with climate anxiety. The climate anxiety scale we used to measure climate anxiety, may only assess a limited facet of climate anxiety, namely impairment due to climate change, but may not assess the complete cognitive profile of climate anxiety or its affective components (see Wullenkord et al., 2021). Future research should use a range of validated methods to assess climate anxiety. Finally, we think it is imperative to explore the relations between a broader anxiety toward environmental degradation (i.e., eco-anxiety or eco-grief; see also Ágoston et al., 2022) and nature connectedness. Possibly, increasing nature connectedness could result in stronger concern about what will be lost, driving pro-environmental action.

5. Conclusion

Experiencing climate anxiety may be rational, and apparently, people who perceive stronger risks of climate change are also those who respond with more anxiety. This study therefore contributes to our understanding of how climate anxiety may emerge. What is needed now is an increased understanding under which circumstances this anxiety is funneled into coherent and concerted climate action rather than paralyze. Besides anxiety, there is still hope and the belief that we as humans can act together to address this crisis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

GR: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing (original draft, review, and editing), visualization, and project administration. MR: conceptualization, data curation, and editing. MW: writing (original draft, review, and editing) and visualization. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the authors and the students (Sofie Menke, Martin Marx, and Lotta Fädler) who were involved in this project for their invaluable help in data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The climate anxiety scale has been validated in a range of non-English speaking countries [e.g., France and Northern Africa (Mouguiama-Daouda et al., 2022), Italy (Innocenti et al., 2021), Poland (Larionow et al., 2022), and the Philippines (Simon et al., 2022)]. Generally, evidence for the originally proposed factor structure of the climate anxiety scale has been limited (perhaps due to cultural variation) and authors have generally proposed and tested a range of different factor structures.

References

Ágoston, C., Csaba, B., Nagy, B., Kováry, Z., Dúll, A., Rácz, J., et al. (2022). Identifying types of eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, eco-grief, and eco-coping in a climate-sensitive population: a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 19, 2461. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042461

Albrecht, G. (2012). “Psychoterratic conditions in a scientific and technological world,” in Ecopsychology: Science, Totems, and the Technological Species, eds P. H. Kahn, and P. H. Hasbach (New York, NY: MIT Press), 241–264.

Bamberg, S., Rees, J. H., and Schulte, M. (2018). Environmental protection through societal change: what psychology knows about collective climate action—and what it needs to find out. Psychol. Clim. Change 30, 185–213. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813130-5.00008-4

Baudon, P., and Jachens, L. A. (2021). scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 18, 9636. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189636

Bradley, G. L., Babutsidze, Z., Chai, A., and Reser, J. P. (2020). The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: a two nation study. J. Environ. Psychol. 68, 101410. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101410

Chater, N., and Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: how focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 1–60. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4046264

Clayton, S., Czellar, S., Nartova-Bochaver, S., Skibins, J. C., Salazar, G., Tseng, Y. C., et al. (2021). Cross-cultural validation of a revised environmental identity scale. Sustainability. 13, 2387. doi: 10.3390/su13042387

Clayton, S., and Karazsia, B. T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 69, 101434. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434

Crandon, T. J., Scott, J. G., Charlson, F. J., and Thomas, H. J. (2022). A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 123–131. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01251-y

Cunsolo, A., Harper, S. L., Minor, K., Hayes, K., Williams, K. G., Howard, C., et al. (2020). Ecological grief and anxiety: the start of a healthy response to climate change? The Lancet Planet. Health 4, e261–e263. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30144-3

Curll, S. L., Stanley, S. K., Brown, P. M., and O'Brien, L. V. (2022). Nature connectedness in the climate change context: Implications for climate action and mental health. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 8, 448–460. doi: 10.1037/tps0000329

Drews, S., and Reese, G. (2018). “Degrowth” vs. other types of growth: labeling affects emotions but not attitudes. Environ. Commun. 12, 763–772. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1472127

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., and Reese, G. A. (2018). Social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 125, 245–269. doi: 10.1037/rev0000090

Galway, L. P., Beery, T., Buse, C., and Gislason, M. K. (2021). What drives climate action in Canada's provincial North? Exploring the role of connectedness to nature, climate worry, and talking with friends and family. Climate 9, 10. doi: 10.3390/cli9100146

Häkkinen, K., and Akrami, N. (2014). Ideology and climate change denial. Pers. Ind. Diff. 70, 62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.030

Hamann, K. R. S., Holz, J. R., and Reese, G. (2021). Coaching for a sustainability transition: empowering student-led sustainability initiatives by developing skills, group identification, and efficacy beliefs. Front. Psychol. 12, 623972. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623972

Hamann, K. R. S., and Reese, G. (2020). My influence on the world (of others): Goal efficacy beliefs and efficacy affect predict private, public, and activist pro-environmental behavior. J. Soc. Issues 76, 35–53. doi: 10.1111/josi.12369

Hamann, K. R. S., Wullenkord, M. C., Reese, G., and van Zomeren, M. (2023). Believing that we can change our world for the better: a triple-a (agent-action-aim) framework of personal and collective self-efficacy beliefs in the context of social and ecological change. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 29, 10888683231178056. doi: 10.1177/10888683231178056

Heath, Y., and Gifford, R. (2006). Free-market ideology and environmental degradation: the case of belief in global climate change. Environ. Behav. 38, 48–71. doi: 10.1177/0013916505277998

Heeren, A., Mouguiama-Daouda, C., and Contreras, A. (2022). On climate anxiety and the threat it may pose to daily life functioning and adaptation: a study among European and African French-speaking participants. Clim. Change 173, 15. doi: 10.1007/s10584-022-03402-2

Hickman, C. (2020). We need to (find a way to) talk about … Eco-anxiety. J. Soc. Work Prac. 34, 411–424. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2020.1844166

Hogg, T. L., Stanley, S. K., O'Brien, L. V., and Wilson, M. S. (2021). The hogg eco-anxiety scale: development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Global Environ. Change 71, 102391. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102391

Innocenti, M., Santarelli, G., Faggi, V., Castellini, G., Manelli, I., Magrini, G., et al. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the climate change anxiety scale. J. Clim. Change Health 3, 100080. doi: 10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100080

IPCC (2021). Climate Change the Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 14.

Jugert, P., Greenaway, K. H., Barth, M., Büchner, R., Eisentraut, S., Fritsche, I., et al. (2016). Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 48, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.08.003

Kurth, C., and Pihkala, P. (2022). Eco-anxiety: what it is and why it matters. Front. Psychol. 13, 981814. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.981814

Landmann, H., and Rohmann, A. (2020). Being moved by protest: Collective efficacy beliefs and injustice appraisals enhance collective action intentions for forest protection via positive and negative emotions. J. Environ. Psychol. 71, 101491. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101491

Larionow, P., Sołtys, M., Izdebski, P., Mudło-Głagolska, K., Golonka, J., Demski, M., et al. (2022). Climate change anxiety assessment: the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the climate anxiety scale. Front. Psychol. 13, 870392. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.870392

Larson, B. M. H., Fischer, B., and Clayton, S. (2022). Should we connect children to nature in the Anthropocene? People Nat. 4, 53–61. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10267

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 46, 819–834. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. Y., and Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1014–1020. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2728

Leiner, D. J. (2020). SoSci Survey. Available online at: https://www.soscisurvey.de (accessed October 4, 2023).

Leiserowitz, A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: the role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Change 77, 45–72. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9059-9

Mayer, F. S., and Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: a measure of individuals' feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 24, 503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001

Mayer, F. S., Frantz, C. M., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., and Dolliver, K. (2009). Why is nature beneficial?: the role of connectedness to nature. Environ. Behav. 41, 607–643. doi: 10.1177/0013916508319745

Mouguiama-Daouda, C., Blanchard, M. A., Coussement, C., and Heeren, A. (2022). On the measurement of climate change anxiety: French validation of the climate anxiety scale. Psychol. Belgica 62, 123–135. doi: 10.5334/pb.1137

Ogunbode, C. A., Doran, R., Hanss, D., Ojala, M., Salmela-Aro, K., van den Broek, K. L., et al. (2022). Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 6, 101887. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101887

Ojala, M. (2013). Regulating worry, promoting hope: how do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 8, 537–561.

Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C. A., and Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: a narrative review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 46, 35–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

Pihkala, P. (2020). Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 12, 7836. doi: 10.3390/su12197836

Pihkala, P. (2021). Commentary: Three tasks for eco-anxiety research – a commentary on Thompson et al. (2021). Child Adol. Mental Health 12, 12529. doi: 10.1111/camh.12529

Pihkala, P. (2022). Toward a taxonomy of climate emotions. Front. Clim. 3, 738154. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2021.738154

Reese, G., and Junge, E. A. (2017). Keep on rockin' in a (plastic-)free world: Collective efficacy and pro-environmental intentions as a function of task difficulty. Sustainability. 9, 200. doi: 10.3390/su9020200

Schwartz, S. E. O., Benoit, L., Clayton, S., Parnes, M. F., Swenson, L., Lowe, S. R., et al. (2022). Climate change anxiety and mental health: environmental activism as buffer. Curr. Psychol. 28, 1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6

Shahrour, G., and Dardas, L. A. (2020). Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1686–1695. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13124

Simon, P. D., Pakingan, K. A., and Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2022). Measurement of climate change anxiety and its mediating effect between experience of climate change and mitigation actions of Filipino youth. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 39, 17–27. doi: 10.1080/20590776.2022.2037390

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockstrom, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., et al. (2015). Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 206–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

Whelan, M., Rahimi-Golkhandan, S., and Brymer, E. (2022). The relationship between climate change issue engagement, connection to nature and mental wellbeing. Front. Pub. Health 28, 790578. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.790578

Whitmarsh, L., Player, L., Jiongco, A., James, M., Williams, M., Marks, E., et al. (2022). Climate anxiety: what predicts it and how is it related to climate action? J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 101866. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101866

Wullenkord, M. C., and Hamann, K. R. S. (2021). We need to change: Integrating psychological perspectives into the multilevel perspective on socio-ecological transformations. Front. Psychol. 12, 655352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655352

Keywords: climate anxiety, climate risk perception, nature connectedness, self-efficacy, policy support

Citation: Reese G, Rueff M and Wullenkord MC (2023) No risk, no fun…ctioning? Perceived climate risks, but not nature connectedness or self-efficacy predict climate anxiety. Front. Clim. 5:1158451. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2023.1158451

Received: 03 February 2023; Accepted: 27 September 2023;

Published: 17 October 2023.

Edited by:

Corinne Schuster-Wallace, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaReviewed by:

Fiona Shirani, Cardiff University, United KingdomPanu Pihkala, University of Helsinki, Finland

Pierpaolo Angelini, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Pavel Sabadosh, Institute of Psychology (RAS), Russia

Mohamed R. Abonazel, Cairo University, Egypt

Copyright © 2023 Reese, Rueff and Wullenkord. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gerhard Reese, Z2VyaGFyZC5yZWVzZUBycHR1LmRl

Gerhard Reese

Gerhard Reese Maria Rueff2

Maria Rueff2 Marlis C. Wullenkord

Marlis C. Wullenkord