94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Clim. , 07 November 2022

Sec. Climate Services

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.922504

This article is part of the Research Topic Gendered Impacts of Climate Change: Women and Transformative Research, Policy and Practice View all 10 articles

Every year 10,000 climate-induced migrants in Bangladesh leave their homes seeking safer locations away from the climate-induced disasters they have experienced. They commonly migrate to nearby urban areas or the capital city after losing their livelihoods in their place of origin. However, the unplanned urbanization, limited capacities of urban infrastructures, service sector deficiencies, man-made disasters, and other social vulnerabilities further push these migrants into an (in)secure state. Hopes of security and capacity to adapt in their new homes can be impacted by the patriarchal society where gender is often associated with unequal social relations and hierarchies. These might extend from every day to long term (in)security. This study draws on qualitative data collected as part of research conducted for two PhD projects. In both cases, climate-induced migrants were forced to migrate from their places of origin due to sea level rise, river erosion, and soil salinity to Dhaka (capital city) and Coxes Bazar (coastal city) of Bangladesh. In this context, are their adaptive capacities influenced by gender relations? How are these adaptive capacities shaped through different institutions? And, how can these adaptive actions improve/strengthen human security? Gendered power relations are the main analytical framework for this paper as power is an influential factor to shape adaptive capabilities. It argues that (in)security, as an outcome of unsustainable adaptability, further pushes climate-induced migrants in vulnerable conditions in their newly settled urban areas. The vulnerability, capacity to adapt, and (in)security are gendered. This will contribute to understand for whom, where, and how the exclusive adaptative initiatives would further place the climate-induced migrants in vulnerable and (in)secure conditions in their newly settled areas.

Bangladesh is a densely populated and riverine South Asian country. The country is regularly impacted by extreme climatic events such as tropical cyclones, river erosion, and high floods due its unique geographical location, and the impacts on the community and economy are compounded by a lack of resources to recover the losses. Bangladesh suffered its longest (40 days) and worst riverine flood in 2018 (IPCC, 2022). The country has experienced such severe floods since 1998. Such flooding events, exacerbated by climate change, are pushing millions of people out of their places of origin, creating a new pattern of displacement and fueling rapid, unplanned, and chaotic urbanization. It is very difficult to define climate-induced migrants and economic migrants as they are very closely interconnected with each other. Climate-induced migrants are described as: “persons or groups of persons who, for compelling reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad” (IOM, 2009, p. 13). Nearly 700,000 people were displaced each year per average over the last decade (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2021). In addition to this average annual people migration, associated with riverbed erosion, sea level rise, and salinity intrusion resulting in crop failure, the loss of livelihoods displacement spikes have also occurred following major disasters. For example, Amphan, a catastrophic cyclone in 2020, displaced 4.4 million people in Chottogram, Sylhet, Rangpur, Mymensingh, and Dhaka (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2021). It is projected that the varied impacts of climate change will displace 13.3 million people by 2050 and remain the country's primary driver of internal migration (World Bank, 2017). Here, the study describes these displaced people as climate-induced migrants since the compounding impacts of climate change leave people no option but to flee from their place of origin or homeland to seek a better life. Various scholars (El-Hinnawi, 1985; Myers, 1993; Jacobson, 1998; Black, 2001; Gorlick, 2007; Mallick and Vogt, 2013; Alam and Miler, 2019) have identified three categories of climate-induced migrants and the triggering mechanisms of their displacement: (i) temporary migration due to climate stress; (ii) permanent migration associated with significant destruction of their living environment; (iii) and migration for a better livelihood due to environmental disruptions in their places of origin. This article refers to climate-induced migrants predominantly from the southern and south-eastern parts of Bangladesh, the regions most vulnerable to climate change impacts (Shamsuddoha et al., 2012), which broadly fall under the three categories defined above.

Unexpected flows of migration shape both the nature of cities and development processes. Climate-induced migrants face vulnerability, i.e., exposure to risk, both at their place of origin and newly settled places (IPCC, 2022). Migrants in cities migrate with the trauma of losing their family members, relatives and friends, and memories of the places of origin. Large numbers of migration have the potential to impact significantly many aspects of urban life including housing, education, utility services, health care, and transportation (Pryer, 2017). However, due to the lack of ability of the state to meet this increasing demand for basic services, resources, infrastructure and facilities in urban areas, climate-induced migrants are often pushed to the margins of development, often in urban fringe areas or abandoned government land, and into situations of significant insecurity. Whether these climate-induced migrants can develop adaptive capacity and overcome this insecurity is key to human health and wellbeing. The aim of this study is to explore the (in)securities of climate-induced migrants through their everyday adaptation practices and gendered experiences of vulnerabilities.

Security is context specific. Different societies have their own meaning of security under the adaptation process. This study found that people are not able to experience or feel secure due to their lack of freedom and restrictions placed on the potential for a flourishing life. This (in)security also arises not only from “being a woman” or “being a migrant,” but is also due to specific practices, processes, and power relations within the social institutions. Therefore, every day experiences can also be understood in this research from a relational perspective. “[A]ll human beings exist at a fundamental level in relation to others” (p. 54). As such, urban space and nature are considered here as a product of hybrid relationships between social and material worlds (Swyngedouw and Nikolas, 2003), where power relations among the residents shapes their everyday lives.

Gender, as a socio-cultural construct, is key to understanding power relations between men and women. The process of gender construction is a part of every individual identity. Gender together with socio-economic conditions, environmental factors, cultural practices and norms, residents or citizenship status, etc., greatly influence the manifestation, negotiation, and resistance to power relations in people's everyday lives during adaptation. Hence, the use of a “gender lens” is helpful to apprehend social processes and is an influencing factor for gendered differences in the adaptation process. An effective gender lens can examine how gender-specific vulnerabilities and disproportionate burdens of gendered responsibilities shape adaptation capabilities. The gender relations between men and women (a heterogenous group) are being socially and culturally produced and reproduced within a particular context (UNDP, 2010). Migrant women's (in)security has also been analyzed from “relational” lens by Alam et al. (2020), who examine migrants' women's negotiation of urban ecologies to negotiate resettlement. “Whereas mobility is normalized for men whose work takes place outside of the house, women's mobility is often constrained by the cultural norms prevailing in the migrants' agrarian origins” (p. 1587). It argues that insecurity is compounded for migrant women because of social power dynamics on top of their “women” and “migrant” status. In Bangladesh, the existing gender norms limit women's access to and control over resources and contribute to the acceptance of the lower status of women in the family (Alston, 2015; Khatun et al., 2017; Parvin et al., 2019), which influence in shaping family power dynamics. According to Khalil et al. (2019), unequal social relations, such as women's marginalized social positions, cultural and religious gender norms, limited access to natural recourses, lack of education, knowledge, information, social networking, and political power are the main determinant of women's vulnerabilities due to climate change. These vulnerabilities include food insecurity, health hazards, less involvement in decision-making, and lack of policy and institutional support for adaptation (Sultana, 2010; Arora-Jonsson, 2011; Alston, 2015; Tanjeela and Rutherfor, 2018).

In this backdrop, the study will pose three research questions: How are the adaptive capacities of climate-induced migrants in urban settlements influenced by gender relations? How are these adaptive capacities shaped/supported by different institutions? And do these adaptive actions improve human security? Gendered power relations are the main analytical framework for this study as power is an influential factor to shape adaptive capabilities. The argument will be put forward in this article that security as an outcome of sustainable adaptability further pushes climate-induced migrants in vulnerable conditions into their newly settled urban areas. Here, sustainable adaptation means the importance of ensuring adaptation in such a way that it not only reduces poverty but also reduces infrastructural and socio-environmental vulnerabilities of climate-induced migrants (Erikson and Brown, 2011). The vulnerability, capacity to adapt, and (in)security are gendered where it refers to variable and fluid meanings and notions regarding femininity and masculinity. This will contribute to understanding for whom, where, and how the exclusive adaptative initiatives would further place the climate-induced migrants in vulnerable and (in)secure conditions in their newly settled areas.

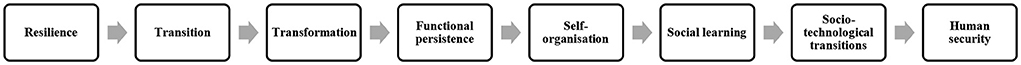

Adaptation is a social and a political act (Figure 1). Adaptation for climate change adaptation is also an opportunity for social reform. It questions the values which drive inequalities in development and unsustainable relationships human beings have with the environment. Contrasting roles performed by different perceived actors are also recognized by adaptation. There is a wide range of literature that covers different scopes and timings for adaptive interventions (for example, IPCC Assessment Report 6).

Figure 1. Frameworks of the analysis of adaptation (Adopted from Peiling, 2011, p. 30).

Power is positioned at the center of conceptualizing adaptation. “Power asymmetries determine for whom, where, and when the impacts of climate change are felt, and the scope for recovery. The power held by an actor in a social system, translated into a stake for upholding the status quo, also plays a great role in shaping an actor's support or resistance toward adaptation or the building of adaptive capacity when this has implications for change in social, economic, cultural or political relations, or in the ways natural assets are viewed and used” (Peiling, 2011, p. 04). People who stay at the center of power in different social institutions avail more options and opportunities to increase their capabilities. Diversified capacities/capabilities provide more sense of security to climate-induced migrants for their adaptation in their newly settled areas for adaptation.

Adaptation has two subcategories, such as adaptation capacity and adaptive action. Capacity creates an opportunity for action. This can foster or hinder the future capacity to act. Vulnerability and its inverse components are conceptualized as adaptive capacity (Susan et al., 2008). Over time, vulnerability and adaptation interact and influence each other. They are shaped by flows of power, assets between actors, and information. Under an analysis within wider socio-ecological systems, the type of hazard risk and the position of the social unit determines the relationship between vulnerability and adaptive capacity.

According to Barnett and Adger (2007), climate change is a human-security threat based on empirical evidence from all over the world both at the national and community level. The human-security threat arises due to conflict over resources that sustain livelihoods, loss of livelihoods, and the undermining of the capacity of states to act in ways that promote human security (Barnett, 2003; Barnett and Adger, 2007). Climate-induced migrants' security regarding food, health, housing, livelihood, and even the decision to migrate, is very much gendered and is the result of a complex combination of sociocultural and economic factors (Dalrymple et al., 2009). Power relations between the feminine and masculine experience serve as a dynamic analytical and political tool and challenge the understandings of women's security arising from men's security perspectives. Both men and women are threatened by the conventional gendered security approach, which restricts their freedom in different ways. It also determines economic and educational opportunities, as well as associated power over resources in terms of access to and control of resources (Kabeer, 1994; Nussbaum, 2005) for being a woman or a man in society. This inequality is seen in regard to the gender-differentiated effects of disasters, where they are more vulnerable in any disaster condition due to their lower socio-economic position (Denton, 2002). This research article considers gender as an important socio-cultural factor to analyze the power relations in the research study areas.

People feel insecure if they do not have freedom. Expansion of freedom is the pathway to development that ensures security. Security is defined as freedom from any risk that withstands escaping two basic risks: the risk of being severely deprived and the possibility of experiencing new risks (Cameron and Thomas, 1954). This definition of security illustrates the central protective function performed by the state through different state organs and operations. As such, the state was, and continues to be, considered central to ensuring security. Then again, individual security cannot be separated from the operations of states (Barnett and Adger, 2007). It is the prime responsibility of the state to ensure protections and opportunities for its citizens through policy and practices (Sen, 1990a). Amartya Sen argued that an individual's life is achieved by the combination of “functioning” and “beings or doings” (Sen, 1990b, p. 113). The actual freedom of an individual person depends on the set of capabilities they possess for determining the alternate lives that they could lead. “Individual claims are to be assessed not by the resources or primary goods the persons respectively hold, but by the freedoms they actually enjoy to choose between different ways of living that they can have reason to value” (Sen, 1990b, p. 114). Freedom is experienced through the capacity to achieve various “functioning” and “beings and doings.” Gender plays an important role to utilize the capacity of “functioning” and “beings and doings” among the climate-induced migrants to protect themselves from the existing vulnerabilities in newly settled urban areas; utilize the adaptation options and opportunities; and thus, their hopeful journey toward urban areas turns into a vicious cycle of uncertainty and confinement.

Everyday insecurities affect climate-induced migrants' long-term human fulfillment. Human development has been defined as the expansion of capability, where capability reflects a person's freedom to choose between different ways of being and living (Sen, 1990a, 1999). In this article, long-term human fulfillment has been considered as an immaterial perspective of human development. It seeks to evaluate the quality of life through understanding freedom at an individual level and proposes alternative ways to view resources and utilitarian-based forms of people's capability rather than poverty. Similarly, people feel secure by protecting their vital core (multidimensional human rights and human freedoms based on practical reason) from direct and indirect threats without impeding long-term human fulfillment (Alkire, 2003; p. 8). (In)security here means a lack of protection or the possibility of being open to any threat. Climate-induced migrants are forced to leave their places of origin and take away the available opportunities for the development of their capabilities, which in return provide them freedom of choice and a sense of security. It is widely grounded that migration has emerged as a strong legitimate option for adaptation (Tacoli, 2009; Warner et al., 2010; Black et al., 2011; Government Office for Science, 2011). Studies illustrate “the coexistence of framings that depict the populations as victims of security threats (with the nexus understood in terms of displacement), as adaptive agents (with migration seen as a coping mechanism or adaptation strategy), and as political subjects (for an overview of this framings” (Bettini and Gioli, 2016, p. 349). This framing that migration as “adaptation” strategies might send out normative and depoliticized narratives as there are intricate unequal power relation and distribution of benefits as an outcome of migration. For women, migration of climate-induced people becomes “maladaptation” if their freedom of choice for achieving capabilities is restricted. Varying degrees of achieving capabilities are connected with women's state of (in)security in their newly settled areas.

This research represents the analysis of cases drawn from field research associated with two PhD research projects1. The first study area is located between Mirpur-11 and Mirpur-12 in the capital city, Dhaka with good roads and connectivity to the other residential areas. The land is owned by the Bangladesh government and regarded as Khaas (abandoned) land. Locally, the place is known as “Jheeler Paar (bank of lake).” People started to migrate from Bhola island, one of the islands in the Southern parts of Bangladesh, after the devastating cyclone in 1970. The migrants found the place suitable for living together as time passed and named the settlement on their place of origin as Bhola slum (informal settlement). The place is still receiving new 2/3 new migrants every month. From the very beginning, the migrants were struggling with the lack of space to settle. The migrants used to fill up the lake with solid waste and soil to make the land livable. The fieldwork in Bhola settlement was carried out from 2016 to 2017. Story-telling, such as life histories, and methodology with open-ended interview approach were followed during the fieldwork. This approach is slowly emerging in the field of anthropology and cultural studies for doing research on climate change migration, (im)mobility, and displacement (Ayeb-Karlsson et al., 2016, 2019; Conway et al., 2019; Ayeb-Karlsson, 2020; Singh et al., 2022). The storytelling methodology has been adopted for this study to understand people's perception on vulnerabilities, adaptation practices, and (in)securities both at the place of origin and the newly settled area at the center of the analysis. In total, 52 in-depth interviews and 6 focus group discussions were conducted. The interview sessions were 2/3 h long and follow-up interviews were also conducted for some of the respondents. The age of the participants ranged from 15 to 60 years. The participants were purposefully selected and followed the snowball sampling method. During the reconnaissance survey and a transect walk, it was clear that the settlement was divided into two parts, long-term migrants and new migrants. Livelihood divisions, relations with neighborhoods, gender divisions of labor, and power relations within the settlements were divided according to their stay in the settlements.

Pictures of study areas are given in separate files.

The second study area was in two urban settlements of hilly slopes named Mohazerpara and Jadipahar in Cox's Bazar. Cox's Bazar is a district of the Chittagong division and one of the world's longest (120 km) natural sea beaches. It is situated in the basin of the Bay of Bengal in the south and west. Cox's Bazaar district is comprised of islands, rivers, hills, and flat lands with an area of 2,491.86 square km (p. 4). Cox's Bazar, a highly landslide-prone zone of the country, where every year casualties are reported from the disaster during the monsoon season (June–September) was triggered by heavy rains. These urban settlements are around 30 years old, and the habitants' number is increasing day by day. Most of the settlers migrated from nearby islands due to sequential cyclones and sea-level rise. The migrated populations who live in the hilly urban settlement are the group most affected and at risk of a landslide hazard. A total of three trips was made to this area during the fieldwork (2014–2015) to observe local geographical conditions and climatic change impacts; to conduct focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews with the migrated community staying 3–5 days each time. Three FGDs were conducted with the selected communities in particular areas, each comprising 10–12 participants. One was a mixed male–female participants group and two were with female participants only.

The age group of the FGD participants was 18–65 years. No formal place was used for the FGDs, and they were allowed to decide the time and venue at their convenience. Most of the FGDs were about 2 h long and conducted during afternoons when participants were free. Local level government officers and NGO staff were used as gate-keepers. Women were purposefully selected from the participants for in-depth interviews to prepare life stories on their lived experiences. Women were purposefully chosen based on four factors: women who were more expressive about their problems and solutions; women who had direct disaster experiences; women who attempted to overcome the situation; and women involved in a process of changing their lives. This was purposive selection because the purpose was to reveal women's individual experiences to understand their roles, indigenous knowledge, and resilience in climate change adaptation more intensively. These in-depth discussions allowed the respondents to depict their daily life experiences, raise issues about their environment, climate change, and their livelihood patterns to cope with the situation from a women's perspective. Furthermore, they offered valuable insights into gender issues regarding vulnerability and adaptive capacity. For these in-depth interviews, a researcher needed to spend an extensive period with them at their houses. They allowed the interviewer to talk alongside their household work as it was difficult for them to spare 4 or 5 h for an interview. In addition, five interviews were conducted with local-level government officials, NGO staff, community leaders, and local government representatives from the area.

These climate-induced migrants of both the study areas are highly vulnerable to climate change in terms of storm surge, cyclones, coastal erosion, and salinity which resulted in the loss of livelihoods and homeland. These environmental changes left these people no choice but to migrate to urban areas (our study areas). Interviews were conducted in Bengali, and the migrant participants were recruited/selected if they were forcefully displaced due to environmental causes such as coastal erosion and storm surges and cyclones. The researchers sought assistance from the community consultants in the study areas to identify those who met the criteria for inclusion. The focus groups were arranged based on their gender and socio-economic profiles. For example, focus groups for males and females and leaders consisting of 6–10 members were organized separately.

Practitioners and local leaders in Bangladesh working on climate issues were interviewed as key informants for the research. The key informant interviews (including both at the community and subject experts at the national level) were conducted in total. They were asked about the settlement history of those places, the legal aspects of lands of their stay, their socio-economic and environmental problems and challenges in the newly settled areas, and information about the ongoing and future plans or projects of government and NGOs. It was used as Supplementary information to understand their security and vulnerability nexus.

The interview schedules and consents were collected prior to interviews through verbal or written forms. All the interviews were recorded, transcribed into English, and all information was secured on university-funded cloud storage which were only accessible to the researchers and their supervisors. Pseudonyms were used and interview place and time were selected according to the choices of the interviewees for protecting their privacy. Interview data from both the study areas underwent thematic analysis. In both cases, community's livelihood patterns, environmental and man-made vulnerabilities, available aid project fund, conflicts within the community, relationship with the neighborhood communities, fear factors, security threats, future plans, government services, etc. These analyses were supplemented by the existing literature, researcher's own observations, and key informant interviews.

The Environmental Justice Forum has defined climate-induced migrants as “persons or groups of persons who, for reasons of sudden or progressive climate-related change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad” (Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), 2021). This reason for migration is widely acknowledged as a response to changing climate, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) recognizes migration as a strategy for adaptation.

Climatic conditions in two of the sites, Bhola and Cox's Bazar, have forced the residents to leave their places due to the continuous negative influence of the climate change that impacts their lives and livelihoods. The ongoing climate crisis pushes the male family members first to move toward cities for better livelihood options. The following is a statement of a climate-induced migrant from Bhola island (now living in Bhola settlement, Dhaka) and he states the problem:

I did not get any jobs right away when I came here. I spent the first few days dilly-dallying, living on my savings trying to understand the circumstances here. I could not pay my room rent regularly. Now, I have come to know many people, realized the circumstances of this place. Bhola is not the same as it was before. We fell victim to the river bank erosion 7–8 times and lost all we had. (Source: Sabur, In Depth Interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

On the other side, the hilly slopes of Cox's Bazar became the informal urban settlement for the migrating populations from the islands (e.g., Sandwip, Hatia, Moheshkhali, Sonadiya) of the southern-east part of the country. Many of these settlers are mostly displaced from their homeland because of natural hazards like cyclones, tidal surges, sea level rises, and riverbank erosion. These settlements have grown over the decades due to a large number of the population migrating from their previous homelands as a way of adapting to climate-induced natural disasters. The residents of Jadirpahar, South Bharchara, and Mohazer Para communities of Cox's Bazar municipality describe the reason behind their settlement in such risky places. As the inhabitants of the community stated:

The reason is that people do not want to go back to such places that can be inundated anytime and cause the inhabitants to lose their homes again. For homeless people, these hilly slopes were cheap lands for habitation. We have not got enough money to buy lands in plains to avoid these risky areas. Thus, we struggle to survive in this unsafe place without minimal services for quality lives (Source: FGD. Women Group; FGD. Men Group, Cox's Bazar).

The above-mentioned statements reflect that the male family members had to migrate temporarily or permanently for the reduction of farm productivity. Men leave female members of their households behind in their coastal villages during the first phase of migration (Kartiki, 2011). This creates a new form of social injustice as women are not only exposed to the negative impacts of the climate crisis to a larger extent but they also face the challenges of maintaining a farming livelihood as they confront patriarchal socio-cultural norms and expectations during the absence of male members of the families. This is due to restrictions from interacting alone with men to whom they are not related and the socio-cultural norms including Pardah, which reduces their access to the knowledge and resources that flows through male-dominated social networks (Kartiki, 2011).

During the focus group discussion with a women's group named “Mohazer Para Mohila Somitee” (FGD. Women Group) in Cox's Bazar, one of the destination sites of climate-induced migrants, the participants said that most of the women of their community are involved in home-based informal economic activities to support their families. Seashells are the main source of income since they get them from the sea and need not spend money collecting them. They can run small craft-making businesses dependent on these natural resources without any capital. Their children collect seashells from the beach and they make ornaments, home-decorating pieces, and household materials. Several beach-side markets have flourished, thanks to the resources of the Bay of Bengal where women are the main informal labor source. This is an example of how women use natural resources in many different ways and support the household economy. In addition, local level informants said that women are the main labor force of informal economic sectors such as dry fish and food preparation, cloth embroidery, and street food vending in this coastal town.

Climate change impacts force men first to leave behind their family members from environmental disaster-prone areas for their loss of livelihoods. Even if they are able to migrate with their family members, they face more natural and man-made disasters (for example, flood, water logging, heat stress, land-slides, flash floods, fire, etc.). Women have to take on more livelihood role in urban areas for their adaptation which push them to more vulnerable condition for their survival and thus, feel insecure. The following story of a young girl living in “Jadipahar” settlement depicts a women's struggle after losing the breadwinner of a family.

I have seen that these people did not come to help us when we used to starve. My mother had to work from dawn to night to feed us. Most of the people can show sympathy but only a few offers real help. My life has taught me that I need to work hard to reach my goal (An In-depth Interview in Cox's Bazar).

Institutions refer to the formal and informal rules of the society in the form of legislation on the one hand, and values, social norms, conventions, and contracts between private parties on the other (Vrooman, 2009). Institutions matter includes “regulatory” aspects (behavioral constraints or rules that enable people), perceptions of the implied social reality, and the judgments. The allocation of certain resources is operated by institutions. They also create a meaningful social order, inequality, and cohesion theoretically. From this above-mentioned, conceptualization of institutions, there are two forms of institutions formal and informal. Various forms of organizations are closely aligned with institutions. If society is played by the rules of the institutions, organizations and individuals are the players of this game. Effective institutions need adequate organizations. People and organizations respond and adapt to the opportunities structured by the institutions. However, they are not merely rule takers but also rule makers. “Actors typically try to change the rules in order to obtain a better fit with their interests, preferences, and ideals, partly through their participation in different policy arenas” (Vrooman and Coenders, 2020, p. 179). This is very much similar to the analysis on Commons (Gibson-Graham et al., 2013), which leads the strength-based approach for governing the support of marginalized communities in Bangladesh's cities (Waliuzzaman and Alam, 2022). Both formal and informal institutions can create opportunities by ensuring justice in sharing the benefits of common resources within the informal settlements.

Here, we explore the complex and multiple links between institutions and issues of social inclusion and exclusion in their collective survivals. In these aspects' climate-induced migrants are positioned at the lower tier of the power hierarchy not only in urban governance due to their climate-induced migrant/migrant identities but also having lost their networks for migration. It affects their development of skills and increases capabilities to effective adaptation and achieve a more secure life. The following is a reflection of climate-induced migrant's hindrance of entering into the formal institution although having all the personal qualifications:

I worked as a teacher in a school, also in a vaccination project run by ICCDRB. But I could not find any other good job after the project had come to an end. It is very difficult to manage a job if you don't have any strong references. I gave an interview for “Shurovi School.” But the influential candidates got the jobs without even appearing at the interview. Sometimes, officials from NGOs come and tell us that they are looking for people as they have job openings. But finally, they hire their relatives. Outsiders like us hardly get any jobs. (Source: In-depth interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

Climate-induced migrants have lesser social networks than others. So, they have merely no access to formal employment opportunities. They are mostly engaged in informal job sectors in urban areas. Female climate-induced migrants have access to the informal labor market in urban areas as domestic helpers, garment workers, and many other informal jobs. On the other hand, a day laborer, a rickshaw puller, a driver, construction workers, or other physical labor-intensive job options are available for male climate-induced migrants. So, the gender division of labor is strongly visible even in the labor market. It is not only sex but also based on their age. The job markets are available for the young climate-induced migrants, but not for old-aged people. These informal forms of employment neither enhance their skills over the years nor have any job security. They may lose these types of employment contracts at any time as most of the employment options are physical labor based without any other security coverage.

It is said that a family is the first institution where gender disparity is mostly visible in a patriarchal society like Bangladesh. Although some recent studies show that son preference is decreasing in Bangladesh among parents, actual fertility decisions are still shaped by son preference (Kabeer et al., 2014; Asadullah et al., 2020). Sex-selective abortions, gender difference in allocation of household resources, opportunities for capacity building favor boy over girl children in the families. Women are considered secondary earners and men as “head of the household.” The condition is not exceptional for the climate-induced migrants, but rather worse than others, due to their already vulnerable condition in urban settings. Even if they were able to overcome all the disparities and be able to enter the job market, their family members do not provide them with adequate support and recognition.

Society or community as another significant informal institution creates and nurtures gendered social values and norms. It determines gender roles and responsibilities. If there is any deviation from these societies disowns them. Women and girls are victims of gender-based violence as they have to participate in changed gender roles for their survival as Climate-induced migrants. The following is an example of such experiences of respondents:

Girls fall victims to domestic violence because of the surroundings. If the majority are good, one cannot be bad. But if the majority are bad, one can hardly be good. Sometimes guys become violent because of unemployment. They get sick, don't feel energized and become aggressive because of frustration. Women have no relative or friends to take shelter assistance after violence here (Source: Focus Group Discussion, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

Some respondents from Cox's bazar field informed that they were a victim of violence and sexual or economical exploitation and polygamy. One migrant woman (30 years old) from Mohajerpara slum states that:

“I came here 7 years back with my husband and two children. One of my neighbors brought me to an apartment to work as a housemaid. Since I was not used to such kind of household activities, whenever I made any mistake, I was scolded by employed family members and I never got a full salary in any month due to my wrong doings. Next, I started working in a male hostel and I was sexually assaulted there. I could not continue that work too. Now I run my own small business- selling vegetable and cake at roadside.” (Source: In-depth Interview, Cox's Bazar).

In addition, adult females suffer from illnesses related to reproductive health due to poor nutrition and unhygienic living conditions. Further, they even do not seek medical assistance, in particular for issues related to their reproductive health due to lack of money, information, and mobility. Thus, their health issues particularly, reproductive rights, are commonly ignored and are not considered. A respondent (25 years old) from Jadipagar settlement who moved to the city indicated:

“I left my village in this monsoon so I am a new resident of this area and do not know where to go for “meyeli rog” (gynecological disease). It is also shameful to share such types of problems with anyone. Moreover, we do not have enough money to spend for treatment or buying medicine. I heard some NGO Apa (female NGO workers) used to come and from her we can take help but yet I did not meet anyone” (Source: In-depth interview, Cox's Bazar).

Besides environmental factors, capability deals with other socio-political factors that assist with understanding the complex nature of human security. There are five important factors that determine the varying degree of security: personal heterogeneity; environmental diversities; variation in social services; differences in relational perspectives, and distribution within the family (Sen, 1999, p. 70). These factors have a significant impact on this research as migrants in the new settlements are not a homogenous group. Their personal and social capacities differ according to age and gender. Broadly, they are divided into groups based on their duration of stay and their gender.

Women's issues can be integrated into the operational activities fully when the community considers them active partners. However, in practice, this is yet to be considered an important concern. An expert from the non-government sector expresses a suggestion about gender and adaptation interface at the community level:

Climate change is just a new way of framing women's issues, but the issues exist in society. The vital aspects of gender inequality such as the inability to exercise rights, restricted mobility, and uneven distribution of resources, at both individual and collective level, all affect women differently in the era of climate change. The overall gender-blind system that is in practice is fully unfavorable for women. This situation undermines women's full participation in any developmental activities and their issues remain unrepresented and unnoticed (Source: Key Informant Interview, Dhaka).

Unequal gender power relations create a male-biased environment within most social and political institutions, which creates unfavorable situations for women. Most of the female participants in the study indicated that they faced discriminatory practices in public spaces. In a patriarchal society, women are always considered subordinate to men and their male counterparts do not easily accept women into similar positions. Even when holding the same position, many men do not consider women as their equals. Since men are the traditional power bearers in the family as well as in society, they are not eager to give up or share their power with their female counterparts. The lack of cooperation by male colleagues is a significant barrier to women's effectiveness in decision-making positions. A health organizer (a master's degree holder) from Cox's Bazar municipality described the situation she faces: “I am proud to say that I am more/ better qualified than some of my male colleagues though they try to oppress me in many ways since I am a woman” (Source: Local level Key Informant Interview, Cox's Bazar).

According to a political theorist Buzan: “Security is one of the most fundamental human needs: an irrefutable guarantee of safety and wellbeing, economic assurance and possibility, sociability and order; of a life lived freely without fear or hardship. That security is a universal good available to all, and a solemn pledge between citizens and their political leaders, to whom their people's security is “the first duty,” the overriding goal of domestic and international policy-making” (Buzan, 1991, p. 7). This definition of security illustrates the central protective function performed by the state through different state organs and operations. Hence, climate-change-related migration needs to study through a human rights lens. “In some cases, migration is an important adaptation strategy to avoid potentially harmful human rights impacts. In other cases, migration is compelled by climate change-related human rights impacts, which exacerbate situations of vulnerability. Such vulnerability to harm acts as a driver of human mobility” (UNHR, 2021). Therefore, human rights and individual security cannot be separated from state functions. People feel secure when they enjoy the freedom to utilize and acquire their capacities. An individual person can have different levels of freedom and different capacities to convert their existing resources into functioning for increasing their adaptive capacities and reducing vulnerabilities. The capabilities may vary according to gender, sex, age, education, and other endowments, even though a person may have the same bundle of primary goods as another person. Climate-induced migrants are vulnerable due to their “climate-induced migrant” status within urban governance and lack of resources (both tangible and non-tangible) to increase their capability and enjoy a secure life. Therefore, climate-induced migrants are more insecure in comparison to other migrants in urban areas susceptible to vulnerabilities, which was depicted through the following statement by climate-induced migrants living in Bhola settlement, Dhaka:

“The people of the adjacent neighbourhood look down upon us... They want us to go away from this place.” (Source: Focus Group Discussion, Bhola settlement, Dhaka).

The feeling of exclusion by the climate-induced migrants is very subjective to their climate-induced migrant identity and regarded as “rootless” by the surrounding neighborhoods. This mistrust and unacceptance hinder climate-induced migrant's adaptation in terms of employment opportunities and social cohesion.

As a part of survival and/or adaptation strategy, climate-induced migrants are forced to do menial and grueling jobs at the very early stages of their life. These are detrimental for their career development through proper education and maintenance of good health in the long run. Respondents who have to start working at an early age are deprived of going to school. For example:

My work starts from 8 AM, lunch time starts from 1 PM. When I do overtime, I usually cannot get back home before 9–10 PM. Fridays are holidays for us. I have struggled a lot in my life. I wanted to go to school and study but ultimately discarded this goal for not to starve. Initially, I did not like the job here. I used to cry a lot because the job seemed too tough to me. But gradually, I have to come to love and adapt to it. (Source: In Depth Interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

It also affects both men's and women's health conditions and could not continue for a long time. Due to their lack of skills, they have to do physical labor-intensive work. It is a vicious cycle and ends up with decaying health conditions, early death, organ loss for occupational hazards, life-long dependency over medication, etc. The following statement is a glimpse of these consequences:

What will I do by going back to my home with this health condition. I won't even be able to earn the money that is required to buy my medicine. At best, I can earn 100 taka daily in my village but I need to purchase medicine of 100 taka daily. What will I do with that money, buy medicine or food? Here I earn around 200 taka daily, I buy medicine for 100 taka and spend another 100 for foodstuff. I cannot help my wife in any household work. I feel exhausted all the time. But one should do some household works and share the burden with one's wife. But I am sick and she gets tired. I could help her If I were not sick. But right now, I cannot even wash my own clothes. (Source: In-depth Interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

Then again, skilled climate-induced migrants are capable enough to survive and have the capacity to ensure a secure life for themselves and their families. However, due to the lack of any institutional support and society-defined gendered roles, they are unable to feel secure as parents.

I wanted to educate all my children properly. I wanted to raise them as my parents have raised us. But I failed to do that with my eldest son. I worked outside leaving him home alone. I could not be as caring and as watchful as I should have been. That's why he has become like this. For this reason, I stay home full time now. I am ready to earn and eat less but want to raise my other two children in the right way. (Source: In-depth Interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

Theoretically, society is structured by institutions and their related forms of organization. Development programs/projects of government and non-government organizations and political parties are institutions that seem inclusive in nature and follow right-based approaches for the vulnerable groups. A study conducted by also states that attempts by the city government to improve services to the poorest of its citizens are hampered by entrenched patron-client practices perpetuated by local political representatives of the city government acting as gatekeepers, blocking access to services for the urban poor. Unfortunately, power relations also exist here in terms of access and distribution of resources. Women as members of the climate-induced migrant community hold the lowest position to utilize their own social networks and avail the support from these development initiatives.

When any fund comes for us, it does not reach the settlement people. People across the street make shady deals and grab hold of the money. I have never gone to any NGOs for any kind of help. I do not go to any gatherings. I feel uncomfortable. I would not come to terms with them. We would differ in opinions. Rich people will go to rich people. Why would they come to us? We are no match for them in terms of money and power. So, why should I go to them? My name is never proposed when it comes to get enlisted in different NGOs developmental or aid projects as nobody knows me here. So many henchmen are there in this Bhola community. Aid provided by NGOs is often snatched away by those henchmen and never comes to me. If I go to any leader for persuasion, he would assure me by saying that he would take care of the matter. But Nothing happens. To whom should I go? Everyone is a fraud. (Source: In-depth Interview, Bhola Settlement, Dhaka).

Climate-induced migrants always have the fear of eviction (as it is owned by the government), being cheated due to lack of social capital as climate-induced migrants, hostility for competition over limited resources, children's future capacity development, police harassment, natural and man-made disasters, etc. Additionally, women have the fear of harassment and sexual assaults on their way to work and domestic violence. Women in Bhola settlement and Cox's Bazar have been abandoned by formal urban planning and are surrounded by neighborhoods with services, amenities, and standard housing provided and maintained by government authorities. The lack of integration between informal settlements and surrounding neighborhoods, the absence of socio-cultural acceptance, plus the denial of basic material conditions, such as utility services, proper housing, and other resources, contribute to people's experiences of (in)security and feelings of fear and powerlessness (Skogan and Maxfield, 1981; Van der Wurff and Stringer, 1988; Pain, 1991). Feelings of abandonment create fear. Fear is the ultimate experience of unfreedom and results in insecurity.

In addition to that, the experience of indignity creates insecurity and destroys people's self-confidence to reduce their vulnerabilities. According to Howard and Donnelly, “human dignity defines the particular cultural understandings of the inner moral worth of the human person and his or her proper political relations with society” (Howard and Donnelly, 1986, p. 82). Dignity is a cultural construct, and different societies have different understandings of dignity based on their gender. One of the female climate-induced migrants defines her loss of dignity in the following way:

I never had to work outside home when I was in Bhola. But now it is required for survival. I would never work outside if not we were stricken by poverty. I feel bad that I work as a house maid in other people's houses. I would have not come here if my husband had not been sick. He would have sent me money every month for my living. (Source: In-depth interview, Bhola settlement, Dhaka).

Bhola and south-eastern islands people experience indignity in terms of lack of privacy, humiliation, exploitation, suspicion, and mistrust for being climate-induced migrants in urban areas. Particularly, women suffer from privacy due to the overcrowded environment. This leads to stress, difficult social relations, and behavioral problems (Priemus, 1986). No secret can be kept from neighbors and no private space is shielded from the prying eyes of passers-by. Single mother's or divorced women's position are not dignified. Socialization process teaches girls to obey their husbands and consider them as their guardians after marriage. Humiliation, including physical and verbal abuse, is compounded by a sense of (in)security as women have no other option than to stay with an abusive husband and in-laws. Women who used to belong to a wealthy family once now came to the street due to climate-change impacts. Nature has taken away their prestigious identity and portrayed them as “climate-induced migrant” which is most disgraceful as a human being and an obstacle to secure their urban life.

The rural–urban migration trend that is apparent in Bangladesh and other countries around the world has changed the pattern of the urban labor market shifting the idea of women's sole role from homemakers to that of breadwinners. Women, who share a large portion of the urban labor force in Bangladesh, represent a substantial transformation of traditional patriarchal gender roles at present as they engage in the garment sector and serve as domestic workers providing some financial independence via earning a salary. In both our research communities, women's contributions to household income became crucial, with workforce engagement in both formal and informal sectors. Conversely, despite the rising stake of women in the paid formal and informal labor market, the wage gap between men and women is still large. Aside from the garments sector, both in Dhaka city and Cox's Bazar, female employment is concentrated in sectors with low returns on their labor and insecure work such as house helpers, beauty parlor workers, and home-based outsourcing works. These poor migrant women who are not permanently employed bear the brunt of poverty and exploitation. Additionally, environmental risk factors affect women's hygiene and reproductive health for climate migrants in urban informal settlements. Women migrants also spend more time in their homes than men in the informal settlements, like those studied here in Dhaka and Cox's Bazar, increasing their exposure to man-made and natural hazards, for example, floods, water logging, air pollution, and fire.

The empirical evidence presented suggests that due to the clear dichotomy between public and private domains in patriarchal societies, women are customarily discouraged from engaging in activities related to the public sphere. Studying the (in)securities of climate-induced migrants living in informal settlements, particularly in Bhola and Cox's Bazar settlements, is significant for two reasons. First, the special characteristics of these settlements warrant investigation as there are clear links between migration and environmental processes. People live a life of precarity, as they are regarded as “rootless” people (BBS, 2015, p. 6) having lost their land in their place of origin. Secondly, climate-induced migrants often live on illegal land in urban areas. This condition restricts them from obtaining basic services and makes them dependent on powerful people (such as political leaders) to access services. They are economically vulnerable and socially marginalized in the city, reliant on a tight network of relations and contacts, though these do not always exist. Therefore, environmental forces, the politics of space (for patron-client relationship), and overall socio-economic status of climate-induced migrants have an overlapping influence on their experiences of (in)security while adapting to cope with their vulnerabilities.

Available adaptation studies overlook this dimension, particularly how migrant women are taking significant roles (productive gender role) at the family level for adaptation, and in turn, this changing responsibility is adding new security threats for them. In concert, traditional gender norms constrain women's access to all sorts of available resources. Women face challenges to obtain adequate and quality food due to the feminization of poverty. Sohel et al. (2021) affirm that women workers in informal sectors experience social, economic, and mental difficulties, including domestic violence, decreased purchasing power, and stress during the pandemic. For instance, rates of maternal mortality remain high due to low investment in women's health and food consumption, showing poor nutritional status among women and girls in urban slums. Further, the situation becomes worst for the urban poor pregnant women to seek for health care services due to socio-cultural and economic factors and the lack of information (Kamal and Rashid, 2004). Informal settlement dwellers who have migrated from rural areas have limited fire-hazard experience and they are less able to comprehend the severity and take early effective mitigation measures (Islam and Mokaddem, 2018). Jabeen (2019) argued that public, private, and parochial spaces in urban informal settlements of Bangladesh are very much gendered and women, particularly migrants, face difficulties for coping and adapting because of their low negotiation capacities. While women's vulnerabilities to climate change are well-documented in many Bangladesh-focused studies, few have explored women's security and human rights challenges, particularly how they occur amongst climate-induced female migrants. As an emerging positive influence on families, communities, and organizations as household earners and decision makers, such security and human rights challenges require further exploration so as to ensure female potential in society is optimized.

As well as their migration-related status, climate-induced migrants face structural inequalities in terms of access to opportunities, information, and freedom due to their migration status and gender. Social networks, education, knowledge, and skills all shape climate-induced migrant's coping capacity (Sen, 1999, 2000; Nussbaum, 2005) in new settlement areas. This restricts women's capacity development and freedom of choice for adaptation options. As a consequence, the inability to choose their own way of living greatly constrains their ability to feel a sense of security and dignity. Though these migrant women leave their home land in search of more financially secure lives, ultimately, they are confined in a vicious cycle of vulnerabilities and experience an immense feeling of insecurity both at the origin (rural), associated with increased anxiety about environmental changes and livelihood loss, and destination (urban), due to insufficient social networks, inadequate services, and opportunities for safe and secure employment. This change maybe associated with the findings of Asadullah et al. (2020) who identified a gradual changing notion of son preferences in Bangladeshi society as women are starting to share the financial burden within the family.

Urban climate migrants become victims of capability deprivation in Bangladesh like other developing countries as different supports offered by both government and non-governmental organizations tend to focus on rural sufferers. The livelihood strategies of poor people in Bangladesh are shaped by the urban–rural divide. For instance, the National Rural Development Policy-2001 worked to secure and save the rural poor, but a similar policy was not initiated in urban areas. The somewhat outdated Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy Action Plan-2009 also lacks recognition of the need for adaptation plans or programs for climate migrants in urban areas. Further, infrastructural development in peri-urban areas and small towns has not received priority to create a strong job market, economic mobility, or sufficient housing and services for the urban poor (including climate-induced migrants). Similarly, the country's first National Social Security Strategy-2015 has not prioritized the increasing number of urban poor compared to rural poor. A recent review about social protection indicates that only about 5% of total SP (social protection) focuses on urban poor, and women have a minimal share in that (Coudouel, 2021). Due to the lack of gender sensitivity, inadequate governmental initiatives and effective arrangements in the government sector, the institutional level efforts for gender transformation are still narrowly situated within the non-government sectors such as NGOs and international development agencies in Bangladesh (Brock, 2002; ELIAMEP, 2008; Roddick, 2011). Thus, migration toward urban informal settlements of climate-induced migrants is not their mere adaptation choice but their only available survival strategy, which drags them into a vicious cycle of vulnerability and insecurity.

This research highlights the ongoing challenges for climate-induced migrants, and in particular, women in Bangladesh, a country significantly vulnerable to climate-induced environmental change and extreme events. Those who leave their affected communities seeking improved livelihoods and living conditions are faced with a different set of challenges, including increased insecurity. Hence, migration as an adaptation solution brings new issues, commonly most felt by females. It contributes to the political geography of environmental migration through a focus on the migrants' destination location and an exploration of their freedom of choice. Further, the gender-specific adaptation discourse emphasis not only focuses on the “freedom from want” as it pertains to livelihoods but also leaves women in a precarious condition where they are entangled with greater household responsibilities, cultural restrictions on property and legal rights, and restricts their possibilities of accessing credits and capability development training that constraint their ability to secure their livelihoods in newly settled areas (Roddick, 2011). Therefore, climate change as a threat multiplier must be seen within a broader “holistic approach” to human security. Climate change is not merely increased insecurity, rather it creates long-term heightened tension over livelihoods and scarce resources. An environmentally vulnerable community becomes the subject of adaptation and state, not as an active actor, enforces, and facilitates the climate-induced migrants within the market economy. Climate-induced migrants are featured in the narratives of migration as an adaptation option (Bettini et al., 2017) without addressing their “freedom of choice” and (in)securities. Thus, their hopeful journey toward urban areas turns into a peril.

Our study findings must be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Firstly, the case-study design of the study identified perspectives at one point in time and hence does not consider the seasonal variations of vulnerabilities and coping practices of the study population that may exist. Data and information from both study areas were collected during the dry/winter season, and in a different season, they might face different livelihood challenges, which the study failed to capture. Secondly, both the study areas focused on only two types of disasters associated with risk at either the source destination hence limiting example diversity. For instance, coastal erosion was considered the reason for migration for the Dhaka slum population, whereas landslide hazard was a consideration for the Cox's Bazaar destination population. Finally, the respondents' age limits were fixed and both studies focused on only women participants' issues. Therefore, other issues of intersectionality such as age, gender, and people with disabilities are not considered in the study.

This research highlights the dimensions and motivations that are responsible for people's decision for moving, and that their decisions about where to move to are crucial for planning future settlements. Moreover, the study sheds light on how existing development challenges particularly in urban, destination locations that include population density, natural and manmade disasters, shortage of land, food security, and human health status are overlayed with the additional vulnerabilities that climate-induced migrants, particularly women bring to these settlements. Placing gender as a priority issue in institutions is not an easy task for a country like Bangladesh, which has always had to deal with many problems related to socio-economic development such as poverty, unemployment, and infrastructure development. Thus, gender issues receive less priority, and they are yet to be considered as a matter that cuts across climate change adaptation-related activities, particularly in urban settings of Bangladesh (Climate Change Cell (CCC), 2009). Disaster-specific vulnerability assessment and security threat identification are important areas of further research to better understand the policy option of climate-induced migration as a sustainable adaptation in Bangladesh where urban settlements are already overwhelmed. Further research with larger study populations will also be important to better understand the specific needs of female, climate-induced migrants allowing for more voices from the migrants themselves, the communities in which they live following their migration, and the NGO and government providers of services they seek to access.

This research highlights that to improve security for female migrants, investment and policy support are urgently required to improve gender-appropriate social supports (often lost during moves to urban settlements) and increased access, including recognition of the need for access to necessary employment, childcare, education, and health services (including reproductive health and counseling). Key strategy and planning documents, such as the Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy Action Plan (BCCSAP) 2009, must consider the research and knowledge management, capacity building, and institutional strengthening required to ensure that urban migrant communities, particularly women, get the focus they need to ensure that the migration trends that occur to ensure the security are considered as important vulnerable populations when planning for services and like research and knowledge management, which can help to develop sustainable strategy and mechanisms to support this migration trend and ensure their security and develop their resiliency.

Although the study was unable to explore the security concern and seasonal vulnerabilities holistically due to the time limits as part of PhD field works. The capability approach (Sen, 1990a, 1999) is used to understand people's freedom of choice and exercise of agency. Those who have greater freedom of choice are more capable of living a worthy life. This argues that policies should focus on what people are able to do and by removing the obstacles from their lives so that they enjoy more freedom and enjoy a life where they have more reason to feel secure in their adaptation phase. Security is socially-differentiated, and security concerns regarding environmental migration are experienced differently by migrants. Women and men face different types of (in)security due to the gendered nature of social norms and practices (Nussbaum, 2005) and economic opportunities (Kabeer, 1994). Gender inequalities also intersect with environmental risks and vulnerabilities. Women are already in a disadvantageous position due to the strongly patriarchal nature of many social systems. When they have to migrate due to environmental changes and settle in an unfamiliar place, their feelings of (in)security change. The transition from natural to non-natural resource-based livelihoods in urban areas potentially brings economic opportunities, but also has a high risk of (in)security for migrants, particularly for women as their former knowledge is undervalued, networks are disrupted, and institutional supports are weakened. Thus, a hopeful journey toward the urban areas placed women in between gendered vulnerability and adaptation with a varying degree of feeling of insecurity in their everyday life.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Macquarie University Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2022.922504/full#supplementary-material

1. ^The research has ethics approval from Australian universities: Macquarie university (Ref no. 5201600616) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (GIR/03/13/ HREC).

Alam, A., McGregor, A., and Houston, D. (2020). Women's mobility, neighbourhood socio-ecologies and homemaking in urban informal settlements. Hous. Stud. 35, 1586–1606. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2019.1708277

Alam, A., and Miler, F. (2019). Slow, Small and Shared Voluntary Relocations: Learning Experience of Migrants Living on the Urban Fringes of Khulna, Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. p. 1–14. doi: 10.1111/apv.12244

Alkire, S. (2003). A Conceptual Framework for Human Security. Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity (CRISE) Paper. London: University of Oxford.

Arora-Jonsson, S. (2011). Virtue and vulnerability: discourses on women, gender and climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005

Asadullah, M., Niaz, M. N., Randazzo, T., and Wahhaj, Z. (2020). Is Son Preference disappearing from Bangladesh? Discussion paper series: 13996. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labour Economics. p. 1–38. Available online at: https://docs.iza.org/dp13996.pdf (accessed October 16, 2021).

Ayeb-Karlsson, S. (2020). No power without knowledge: A discursive subjectivities approach to investigate climate-induced (im)mobility and wellbeing. Soc. Sci. 9, 103. doi: 10.3390/socsci9060103

Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Fox, G., and Kniveton, D. (2019). Embracing uncertainty: A discursive approach to understanding pathways for climate adaptation in Senegal. Reg. Environ. Chang. 19, 1585–1596. doi: 10.1007/s10113-019-01495-7

Ayeb-Karlsson, S., van der Geest, K., Ahmed, I., Huq, S., and Warner, K. (2016). A people-centred perspective on climate change, environmental stress, and livelihood resilience in Bangladesh. Sustain. Sci. 11, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0379-z

Barnett, J. (2003). Security and climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 13, 7–17. doi: 10.1016/S0959-3780(02)00080-8

Barnett, J., and Adger, W. N. (2007). Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Polit. Geogr. 26, 639–655. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.03.003

BBS (2015). Population Distribution and Internal Migration in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Information Division.

Bettini, G., and Gioli, G. (2016). Waltz with development: insights on the developmentalization of climate-induced migration. Migrat. Dev. 5, 171–189. doi: 10.1080/21632324.2015.1096143

Bettini, G., Nash, S. L., and Gioli, G. (2017). One step forward, two steps back? The fading contours of (in)justice in competing discourses. Geograph. J. Royal Geograph. Soc. 183, 348–358. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12192

Black, R. (2001). Environmental Refugees: Myth or Reality? Working Paper No.34. Brighton: University of Sussex. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/research/working/3ae6a0d00/environmental-refugees-myth-reality-richard-black.html (accessed October 18, 2022).

Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M., and Beddington, J. R. (2011). Climate change: Migration as adaptation. Nature. 478, 447–449. Available online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/478477a

Brock, H. (2002). Climate Change: Drivers of Insecurity and the Global South. London: Oxford Research Group.

Buzan, B. (1991). People, State and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era, 2nd Edn, London: Pearson Longman.

Cameron, W. B., and McCormick, T. C. (1954). Concepts of security and insecurity. Am. J. Sociol. 59, 556–564. doi: 10.1086/221442

Climate Change Cell (CCC). (2009). Climate Change, Gender and Vulnerable Groups in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Department of Environment (DoE), Ministry of Environment and Forests and Component 4B, Comprehensive Disaster Management Program (CDMP) Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, Dhaka, Bangladesh. p. 1–82. Available online at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/48024281.pdf (accessed October 18, 2022).

Conway, W., Nicholls, R. J., Brown, S., Tebboth, M., Adger, W. N., et al. (2019). The need for bottom-up assessments of climate risks and adaptation in climate sensitive regions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 503–11. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0502-0

Coudouel, A. (2021). Bangladesh Social Protection: Public Expenditure Review. Washington, D. C: World Bank Group. Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/829251631088806963/Bangladesh-Social-Protection-Public-Expenditure-Review (accessed March 10, 2022).

Dalrymple, S., Hiscock, H., Kalam, A., Husain, N., and Rahman, Z. (2009). Climate Change and Security in Bangladesh: A Case Study. Dhaka: Saferworld and Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies (BIISS).

Denton, F. (2002). Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: why does gender matter? Gend. Dev. 10, 10–20. doi: 10.1080/13552070215903

El-Hinnawi, E. (1985). Environmental Refugees. Nairobi: United Nations Development Programme (UNEP). Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/121267?ln=en (accessed October 18, 2022).

ELIAMEP (2008). Gender, Climate Change and Human Security: Lessons from Bangladesh, Ghana and Senegal. Women's Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) with ABANTU for Development in Ghana, ActionAid Bangladesh and ENDA in Senegal.

Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF). (2021). The Urgent Need for Legal Protections for Climate Justice. London: Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF). Available online at: https://ejfoundation.org/reports/the-urgent-need-for-legal-protections-for-climate-refugees (accessed October 17, 2022).

Erikson, S., and Brown, K. (2011). Sustainable adaptation to climate change. Clim. Dev. 3, 3–6. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2010.0064

Gibson-Graham, J. K., Cameron, J., and Healy, S. (2013). Take Back the Economy. An Ethical Guide for Transforming our Communities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gorlick, B. (2007). Environmentally Displaced Persons: A UNHCR Perspective. Presentation at Environmental Refugees: The Forgotten Migrants meeting, New York. Available online at: www.ony.unu.edu/seminars/2007/16May2007/presentation_gorlick.ppt (accessed June 12, 2014).

Government Office for Science (2011). Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities. Final Project Report. London: Foresight. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287717/11-1116-migration-and-global-environmental-change.pdf (accessed October 18, 2022).

Howard, R. E., and Donnelly, J. (1986). Human dignity, human rights, and political regimes. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 80, 801–817. doi: 10.2307/1960539

Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, IDMC. (2021). Displacement Data by Country: Bangladesh. Geneva, Switzerland. Available online at: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/bangladesh (accessed February 25, 2022).

IOM (2009). Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

IPCC (2022). Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP).

Islam, Z., and Mokaddem, H. (2018). Fire hazards in dhaka city: an exploratory study on mitigation measures. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 12, 46–56. doi: 10.9790/2402-1205014656

Jabeen, H. (2019). Gendered space and climate resilience in informal settlements in Khulna City, Bangladesh. Environ. Urban. 31, 115–138. doi: 10.1177/0956247819828274

Jacobson, J. L. (1998). Environmental refugees: a yardstick of habitality. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 8, 257–258. doi: 10.1177/027046768800800304

Kabeer, N., Huq, L., and Mahmud, S. (2014). Diverging stories of missing women in South Asia: is son preference weakening in Bangladesh? Fem. Econ. 20, 138–163. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2013.857423

Kamal, N., and Rashid, R. (2004). Environmental risk factors associated with RTI/STD symptoms among women in the Urban Slums. J. Dev. Areas. 38, 107–121. doi: 10.1353/jda.2005.0009

Kartiki, K. (2011). Climate change and migration: a case study from rural Bangladesh. Gender Dev. 19, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2011.554017

Khalil, M. B., Brent, C. J., Kylie, M., and Natasha, K. (2019). Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 12, 664–676. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2019.1676188

Khatun, M. R., Gossami, G. C., Akter, S., Paul, G. C., and Barman, M. C. (2017). Impact of tropical cyclone aila along the coast of Bangladesh. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 8, 1592–1599.

Mallick, B., and Vogt, J. (2013). Population Displacement After Cyclone and Its Consequences: Empirical Evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Natural Hazards: Springer. doi: 10.1007/s11069-013-0803-y

Myers, N. (1993). Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 357, 609–613. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0953

Nussbaum, M. (2005). Women's bodies: violence, security, capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 6, 167–183. doi: 10.1080/14649880500120509

Pain, R. (1991). Space, sexual violence and social control: integrating geographical and feminist analyses of women's fear of crime. Prog. Hum. Geograph. 15, 415–431. doi: 10.1177/030913259101500403

Parvin, G. A., Sakamoto, M., Shaw, R., Nakagawa, H., and Sadik, M. S. (2019). Evacuation scenarios of cyclone aila in bangladesh: investigating the factors influencing evacuation decision and destination. Prog. Dis. Sci. 2, 100032. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100032

Peiling, M. (2011). Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Priemus, H. (1986). Housing as a social adaptation process: a conceptual scheme. Environ. Behav. 18, 31–52. doi: 10.1177/0013916586181

Pryer, J. A. (2017). Poverty and Vulnerability in Dhaka Slums: The Urban Livelihoods Study. London: Taylor & Francis.