95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Clim. , 10 January 2022

Sec. Climate Risk Management

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.657241

This article is part of the Research Topic Affective Dimensions of Climate Risk View all 9 articles

This article examines the public perceptions on the drafting process of Finnish Climate Act amendment, which is a legislation on the climate policy that aims to mitigate climate change and secure adaptive capacity. In this paper we present results of a thematic analysis, which reveals citizens' perceptions of the procedural values, with respect to transparency, participation, and acceptance, and the objectives of the amendment, such as the climate neutrality target for 2035. The research data consisted of 2,458 answers to a citizen survey on the Finnish Climate Change Act amendment. Our results reveal that the opinions of citizens ranged from highlighting the urgency of political action to climate denials, with varying perceptions on process and proposed outcomes. While over half of citizens felt positively about the 2035 climate neutrality target created in the Climate Change Amendment Act, only a third believed that there was appropriate opportunity for public participation in the amendment process. Based on these findings, we suggest that participatory and transparent processes in legislative drafting are prerequisites for the sustainability transition and the implementation of international climate mitigation targets.

Various dimensions of justice related to climate change mitigation and adaptation policies are crucial to develop and implement fair and just policies, provide compensation for adverse impacts, and assist adaptation (Paavola, 2005; Klinsky et al., 2017; Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, 2019). For instance, the yellow vest protests in France in 2018 partly originated from the workers' demands for fair design of carbon-related fuel taxes (Vona, 2019). Currently, finding the means for effective GHG cuts while developing pathway to sustainable and fair society is high on the political agenda, for example via the European Green Deal (European Commission, 2020) and the EU's legislative proposals and policy initiatives of the ‘Fit for 55 package’ (European Council, 2021). Despite that the majority of policymakers and scientists nowadays agree on the urgency climate action, not all citizens agree with the statement that warming is human induced or associate it with elitism (see, e.g., Wetts, 2019; for the UK by YouGov, 2014).

Climate legislation aims to mitigate climate change, reduce the potential harm and losses caused by climate change and to increase and maintain the benefits of climate adaptation. Timely national legislation is necessary to enforce the legal obligations created by international climate agreements, such as the Paris Agreement [UNFCC., 2015; signed in 2016]. Several countries, such as the UK (2008), Austria (2011), Bulgaria and Denmark (2014), Ireland, France, and Finland (2015), and Sweden (2017), have adopted climate legislation to impose binding climate objectives and to establish a framework for national climate policy (Bodansky, 2016; Duwe and Evans, 2020). The main purpose of the national framework legislation is to steer governmental action toward carbon neutrality (Duwe and Evans, 2020). The multi-level nature of climate policy and the co-existence of multiple political authority as well as the necessity of all economic sectors to reduce GHG emissions can raise significant resistance and criticism, which give an apparent reason to emphasize public participation in national climate policy (Bäckstrand et al., 2018; Vihma et al., 2021). Some countries have included stakeholder mechanisms to ensure public participation in national climate legislation.

In this paper, we analyze public perception on procedural values and proposed outcomes in Finnish Climate Change Act amendment. We have chosen to analyze Finland, which is a civil law country with an established consultation procedure for legislative drafting (Airaksinen and Albrecht, 2019). In the Scandinavian civil law tradition, participation in legislative drafting through public consultation procedures has received increasing attention (Keinänen and Kemiläinen, 2016; Airaksinen and Albrecht, 2019; Meriläinen et al., 2020). We analyze responses to a survey that was available online in December 2019, which was part of the public consultation of the amendment of the Finnish Climate Change Act (609/2015). The Climate Change Act establishes a framework for national climate policy and sets obligations for the state to reduce the carbon emission levels of the 1990s by 80% and aims to improve public participation and access to information (Pölönen, 2014). The main objective of the amendment of Finnish Climate Change Act is to introduce a target of zero emissions by 2035 and negative emissions by 2050, and to update the framework for organizing climate policy among different authorities (Finnish government., 2019). In comparison, European climate law aims for net zero by 2050 (European Council., 2019).

Public perceptions of climate regulation are important to explore for several reasons. First, these studies can provide insight into the local socio-political contexts that can assist policy makers and legislative drafters in designing timely climate legislation (Crona et al., 2013; Bollettino et al., 2020). Second, it can improve the acceptance of the regulation, as well as ensure transferrable policies and support the implementation phase. Third, it can help to explain citizens' actions and inaction in the mitigation and adaptation of climate change (Bollettino et al., 2020). Little is known, particularly on a national scale, about public opinion in relation to the procedural values and the overall objective of a legislative proposal. We aim to reveal the spectrum of public perception in terms of support for ambitious climate change initiatives and procedural values related to participation, transparency, and acceptance of the objectives of the amendment. Therefore, we examine an element of climate justice: procedural justice, which can be gained through transparent, fair, and inclusive participation processes of societal decision-making (Tyler, 1990; Lawrence et al., 1997; Ageyman and Evans, 2004; Emami et al., 2015). This knowledge can support the policymakers to plan climate policy initiatives. With this paper we aim to shed light on procedural justice within the climate justice debate and its potential to foster climate action. We aim to answer the following research question:

How do citizens perceive the procedural values of the Finnish Climate Change Act amendment, such as participation, transparency, and acceptance?

What kind of citizen attitudes exist toward the objectives of the Finnish Climate Change Act amendment, such as the 2035 climate neutrality target?

Climate justice refers to justice dimensions which are linked to demands to reduce emissions from fossil fuels, support for a just transition to clean energy, climate leadership and promotion of participation (Gardiner, 2011; Schlosberg and Collins, 2014). In the context of climate policy, justice has been connected to demands to mitigate climate change and stay under the 1.5°C global average temperature (Robinson and Shine, 2018) as well as to restore the losses caused by climate actions (e.g., employment) (McCauley and Heffron, 2018). According to a recent IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report, the damage to livelihoods and biodiversity will increase if this objective is not met (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018).

Climate change widens the existing social, geographical, economic, and intergenerational inequalities (Schlosberg, 2013; Walker, 2020). Certain communities, such as indigenous groups or rural citizens living in developing countries are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change [Schlosberg, 1999; Holifield, 2001; Martinez-Alier, 2002; Horton, 2006, p. 128]. According to Sanson and Burke (2020) climate justice is also about fighting structural violence as climate change affects those who have contributed less to the problem on a global scale. Intergenerational justice becomes central aspect within climate justice, as younger generations need to live longer with the consequences of climate change—with increasing threat to health, food security, water availability, housing, agriculture, and natural ecosystems which threatens the basic rights of human beings (Albrecht et al., 2020a; Sanson and Burke, 2020).

In this paper, we base our analysis on the concept of procedural justice, which in the context of national climate policy entails opportunities of public in shaping climate policies as well as experiences of public on participation and procedural fairness (e.g., Lind and Tyler, 1988; Klinsky and Dowlatabadi, 2009; Emami et al., 2015). Within the climate policy literature, two aspects of justice are often described: distributive justice related to the possible beneficial or adverse impacts resulting from the implementation or non-implementation of a decision (Young, 1994; Klinsky and Dowlatabadi, 2009), and procedural justice related to how parties perceive their position and engagement in the processes of policymaking (Tyler, 1990; Lawrence et al., 1997; Emami et al., 2015). How citizens and interest groups perceive their positions and engagement has previously been studied, for example, in relation to energy transitions (Williams and Doyon, 2019; Vringer and Carabain, 2020; Devine-Wright et al., 2021), renewable energy projects (Goedkoop and Devine-Wright, 2016) and climate change adaptation within agricultural sector (Popke et al., 2016).

Procedural justice is of crucial importance for the perception of fairness, trust, and public satisfaction (Thibaut et al., 1974; Tyler, 1990; Lawrence et al., 1997; Goedkoop and Devine-Wright, 2016). It consists of e.g., recognition, participation and transparency in environmental planning, decision-making, and governance (Lind and Tyler, 1988; Schlosberg, 1999; Fraser, 2001; Schrader-Frechette, 2005; Paavola, 2008). Recognition, though it could be considered as its own pillar of justice alongside procedural and distributive justice, does not directly include participation (Fraser, 2001; Honneth, 2004). It is about acknowledging the existence of group of stakeholders or citizens e.g., one can be Finnish resident but not Finnish citizen, whereby citizenship is required to vote in parliament elections. All EU (European Union) citizens should be treated equally, and they can vote in EU and municipal elections. Voting rights start at the age of 18 and therefore young people are often treated as citizens to be.

Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development states that environmental issues should include the participation of all concerned citizens and that participation should be facilitated by states to encourage public awareness (United Nations., 1992). After the Rio Declaration, it has been widely emphasized that more effort should be diverted to the engagement and participation of citizens in the processes of solving burning societal problems, such as climate change (Bunders et al., 2010; Reed and Abernethy, 2018). Participation can take many forms, from simply hearing affected parties to giving them power in decision-making (Paavola, 2005). Participation also requires recognition, which implies respect and being valued (Fraser, 2001; Paavola, 2005; Williams and Doyon, 2019). Finland has been active in developing consultation procedures through guidelines for public hearings (Finnish Council of State., 2016). In the Finnish legislative tradition, this process perspective is addressed through transparent legislative procedures and participatory consultation procedures in which interest groups and citizens are heard (Tala 2005, p. 132; Airaksinen and Albrecht, 2019). For example, legislative drafting includes ex ante policy appraisal during which impacts to different societal groups are assessed (Tala, 2005)—then, identifying and addressing all relevant societal groups is crucial for procedural justice. In this regard, citizen participation in broader terms, as stated in the objectives of the Finnish Climate Change Act, is unusual in Finnish hearing procedures, and therefore this procedure can be interpreted as formal way to acknowledge participants. According to the Finnish constitution (paragraph 20), the right to participate in decision making concerning the environment is to be safeguarded by the authorities.

In addition, the transparency and openness of legislative drafting improve the assessment of the impact of public consultation on legislative proposals (Keinänen and Kemiläinen, 2016; Meriläinen et al., 2020). Transparency is a concept that highlights access to information and the principle of legal certainty, which aims to safeguard the transparency and openness of the processes of legislative drafting, e.g., transparency requirements of the Paris Agreement aim at more ambitious national climate policies (Weikmans et al., 2020). In international climate negotiations, transparency toward the member states and the international community has been highlighted. Transparency in public consultations is also the main objective of the guidelines for legislative drafting and is emphasized in the guidelines from the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) for better regulation (OECD., 2010; Finnish Council of State., 2016). Interest groups have a significant role in Scandinavian legislative politics, which has also been characterized as corporatism (Teräväinen-Litardo, 2015; Vesa et al., 2018). This can cause challenges to the transparency objectives. In our paper, participation through public consultations is expected to contribute to the procedural quality of legislative drafting through perceived transparency and fairness.

Next, we describe the materials and methods and then turn to the analysis results.

The research data consisted of 2,458 responses to the survey on citizen perceptions of the Finnish Climate Change Act amendment. The Ministry of the Environment of Finland opened a survey utilizing the Webropol web survey platform, which was open from 2nd of November 2019 to 9th of December 2019. The survey launched the consultation process, which precedes the law drafting. The survey was targeted to the public, and it was accessible through the webpage of the Ministry of the Environment and social media in 6 different languages: Finnish, Swedish, English and three Sami languages. Anyone interested in Finnish Climate Change Act amendment could participate in the survey. Accessibility of participation was addressed using e-consultation methods in the form of an online survey, which can improve opportunities for participation for different social groups from various geographic locations (Albrecht et al., 2021). Open web surveys attract participants who take part in climate action and are concerned about climate change or are opposing climate policy in a form of climate denial, which is why a survey might construct the public in limited ways (Capstick et al., 2015). The part of society that holds a neutral opinion toward climate policy, and represents most voters, could remain underrepresented in such a survey.

The survey was comprised of 19 questions with yes, no, and I do not know options with open-ended questions, which could then be further expanded upon in an open form (see Appendix 1 for translated survey). Additionally, the survey included themes of transparency and opportunities for participation, public acceptance, scope of application, and legal measures. The survey design was piloted in cooperation with the research project All-Youth, which also received a permission for the further analysis of this data from the Ministry of Environment, Finland.

We conducted a mixed-method analysis, which can combine quantitative and qualitative analytical elements and therefore aims to gain a deeper understanding and add validity of the findings (e.g., Hurmerinta-Peltomaki and Nummela, 2006; Creswell et al., 2011; McKim, 2015). Our analysis consisted of simplistic statistics and thematic analysis (e.g., Boyatzis, 1998; Guest et al., 2011) to reveal differences in the public perceptions toward participation, transparency, and acceptance of the Finnish Climate Change Act. The analysis was conducted through qualitative coding with the software Atlas.ti 8, because of the considerable number of responses to the open-ended questions that were used to give the respondents the opportunity to reflect on climate policy issues. Atlas.ti software can be used to create keywords that are linked to quotations, which can then be grouped and sorted (Friese, 2019). We created qualitative codes based on the variety of answer options to the open-ended questions. Our qualitative coding resulted in 1778 hits on 336 qualitative codes of which we only selected verified quotations with a qualitative code that had occurred at least 10 times. These were 178 qualitative codes in total, and based on them, the answers to the open-ended questions were sorted into five groups according to urgency of climate action from those calling for climate urgency to those denying climate change (Albrecht et al., 2020b). These codes were grouped under themes of transparency, participation, acceptance, and objectives of the Climate Change Act amendment e.g., carbon neutrality by 2035.

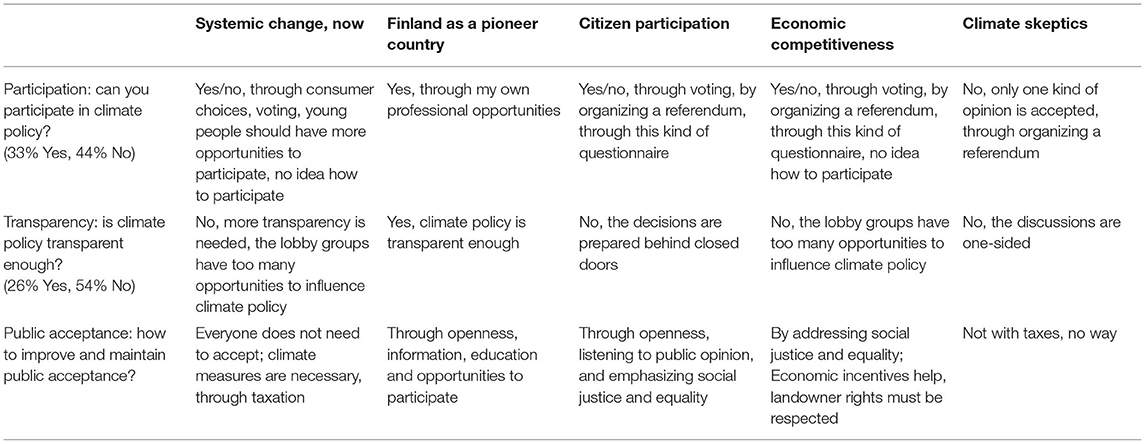

In this section, we present the results of the thematic analysis that focused on the variation of public perceptions toward the Climate Change Act amendment. The results allowed us to scrutinize the spectrum of attitudes, which varied from those calling for urgent climate action to those denying climate change. We divided the respondents into five categories following the climate orientation of the respondents. We labeled these categories “systemic change, now,” “Finland as a pioneer country,” “citizen participation,” “economic competitiveness,” and “climate change deniers” (see Table 1).

Table 1. The results of the theme analysis ranged from citizens who supported additional climate change initiatives to climate skeptics.

When asked, “can you participate sufficiently in the climate policy,” 37% of the respondents replied that they could participate sufficiently, and 44% of the respondents could not participate sufficiently in the climate policy. In the survey results, it is noteworthy that those respondents who highlighted the need for greater climate change action often stated that they could participate in the legislative process through their professional activity: “I can participate through my own activity and work and of course through voting.” The members of this group of respondents were more likely to be responding to the questionnaire as an expert, which demonstrates that climate expertise is gaining momentum in addition to strong forest and agriculture advocacy, which is characteristic of the Finnish policy style.

The survey results showed that the implementation of participatory rights for a wide audience as included in the Finnish Climate Change Act from 2015 has been challenging. The “I don't feel like I'm being heard” type of responses demonstrate that despite the formal consultation procedure, creating a feeling of being heard requires more participatory methods and integration of the results of the consultation into the legislative proposal. The respondents stressing the urgency of climate action (systemic change, now) emphasized citizen action through the choices of NGOs and consumers. This can widen the gap between the climate movement and policy makers, as these forms of participation are beyond the scope of legislative drafting, which relies on formal hearing procedures of the public and interest groups. Those respondents who called for more climate action also called for more youth participation. In particular, the young respondents emphasized that despite the hearings, there was not enough climate action: “I feel that the concerns of citizens, especially young people that worry about climate change, are not taken seriously and actions that aim to mitigate climate change are not done fast enough.”

The respondents emphasizing parliamentary democracy as a form of citizen participation were most likely to mention elections and referendums, surveys, and e-deliberation to improve the participatory condition. Novel approaches that supplement the democratic institutions, such as online surveys, e-deliberation and mini-publics have also been referred to as democratic innovations (Jäske and Setälä, 2019). Climate skeptics also lamented participation and discussion culture. They stated that only one kind of opinion was accepted as a basis for participation and declared that the public discussion was narrow while applying quasi-scientific argumentation.

When asked, “whose participatory possibilities should particularly be improved,” out of 1,552 responses, 1,297 were classified to 10 groups (Figure 1). Children, young people, and young adults were mentioned 453 times in the open field. Researchers and experts were mentioned 220 times. Citizens (137), everyone (125) and agriculture and forestry stakeholders (117) were also mentioned over 100 times. Citizens with small income (31), industry representatives (30), industry representatives (30), nobody (15) and consumers (14) were mentioned over 10 times. Other 255 responses were mentioned <10 times or remained unclassified, part of that since they were populist statements against green and left politics or climate sciences.

In the survey, participants were asked: “Is Finnish climate policy transparent enough?” 54% of the respondents stated that Finnish climate policy was not transparent enough. Some respondents described Finnish climate policy as “cabinet politics,” where the lobby groups command control. Additionally, the respondents emphasizing citizen participation stated that the citizens should be better informed about climate policy: “There is not enough information available in my opinion.” In the citizen survey, the demand for more information, in a comprehensible format, was expressed many times, as it would also improve the acceptance of climate policy. The climate change deniers were also concerned about the lack of information; however, they stated that alternative facts were not considered. The media plays a key role in shaping public perception and policy agendas, which is why media reports on climate change matter (Andersson, 2009).

The respondents stating that climate policy was sufficiently transparent belonged to the “Finland as a pioneer country” group. They reasoned that there is enough media debate and visibility on climate issues: “Climate policy is widely discussed in media, and it is easy to find more information online.” These respondents were more informed about climate policy because of their expertise.

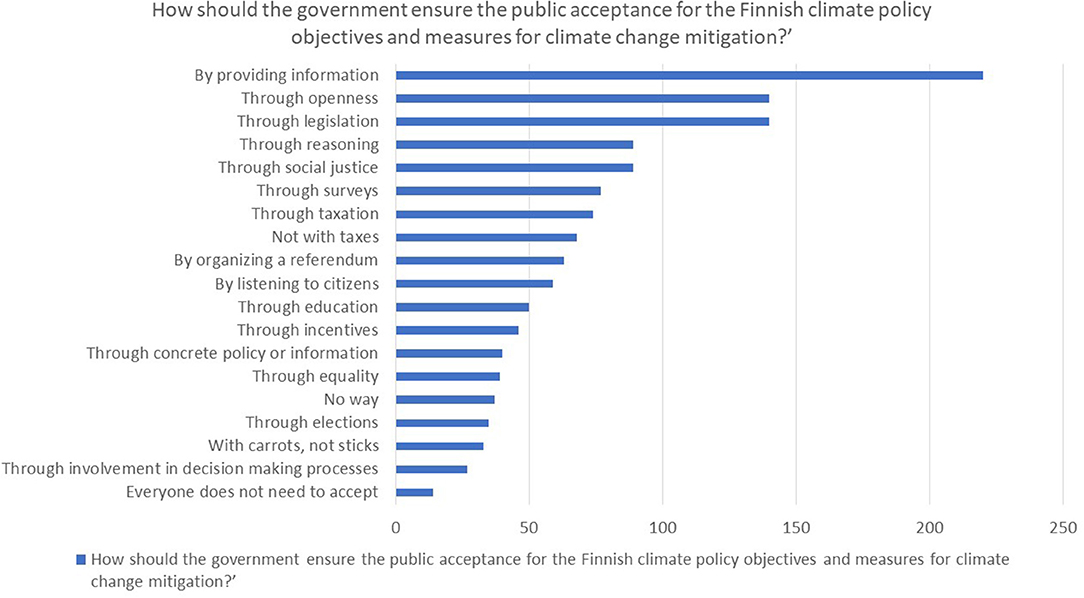

When asked: “How should the government ensure the public acceptance for the Finnish climate policy objectives and measures for climate change mitigation?” most reactions stated that public acceptance could be increased through sufficient and understandable information, openness and transparency, and additional opportunities for participation. These are elements of procedural justice that contribute to the quality of ex-ante policy appraisal. Within 1,822 answers to the open question, we summarized 1,340 reactions into 19 categories that were mentioned at least 10 times (Figure 2).

Figure 2. How should the government ensure the public acceptance for the Finnish climate policy objectives and measures for climate change mitigation?

The respondents emphasized that it is not sufficient to simply hear the public; public opinion should also impact decision making: “Interest groups and citizens should be heard, and the ideas derived from these consultations should be fully considered.” Respondents emphasized that access to information can increase the acceptance of climate policy, the information should be easy to access and to comprehend. The role of experts and expertise was highlighted, especially in the “Finland as a pioneer country” group of respondents. Here especially the role of the Finnish Climate Panel, which is a scientific advisory organization that aims to bring scientific knowledge into decision making, was highlighted.

In addition, increasing the ambition of climate policy would bring more acceptance, according to those respondents that support the 2035 climate neutrality objective (“systemic change, now” group). More effective and concrete climate policy could be achieved e.g., with carbon taxation, meet taxation and other policies that reduce emission and motivate people to make choices e.g., for vegetarian food. The survey results reveal that those who highlighted citizen participation were more likely to state that public acceptance could be improved and maintained by addressing social justice and equality: “The citizens accept if the issues are reasoned to them and at the same time society and equality are safeguarded.” As the Finnish Climate Change Act is amended to bring its objectives in line with the targets of the Paris Agreement, more of the burden of climate mitigation will be transferred to various parts of society according to the NDCs (nationally determined contributions) (Weikmans et al., 2020).

We noted that respondents tended to favor their own perspective when asserting measures that would be influential in obtaining further public acceptance of climate change policy. For instance, respondents who highlighted citizen participation argued for participatory rights, citizen polls and referendums, and respondents who emphasized economic competitiveness stated that economic incentives would help gain public acceptance. The latter actors stressed the importance of the landowners' right to decide on the use of their property. This was highlighted in the survey results when participants were asked “should the regulatory measures for carbon emissions and sinks be included in the Climate Change Act?” and whether “the sector-specific emission reduction targets should be included in the Climate Change Act.”

In the survey, respondents were asked whether the 2035 objective should be included in the legislation and whether other objectives and means for carbon emission reduction should be included in the Climate Change Act, such as measures to regulate the emissions and sinks from land use, land use changed and forestry, total amount of emissions, carbon budgets to each sector or climate compensations. The results of the respondents' perceptions of these proposed measures are summarized in Table 2.

Fifty-five percent of the respondents were in favor of the targets of carbon neutrality by 2035 and carbon negativity by 2050. These targets were particularly supported by the “systemic change, now” and “Finland as a pioneer country.” The inclusion of a paragraph on carbon emissions and sinks in the Finnish Climate Change Act gained the most support from the public (63%). The respondents supporting this (from the systemic change, now and citizen participation groups) stated that this paragraph should be formulated to adhere to the objectives of the EU LULUCF regulation. In the “economic competitiveness group,” forest and landowners” interests were represented: “I would like to stress the interests of economic forestry.” In the systemic change now, Finland as a pioneer country and citizen participation groups the importance of forest conservation and old growth forests were stressed.

The inclusion of a paragraph on climate compensation gained the least support (35%), as most respondents (48%) stated that it was not an efficient measure for carbon emission reductions and would lead to increased inequality. Members of the “Finland as a pioneer country” group were most likely to be in favor of this aim. Climate compensation takes the idea of distributional justice to the next, more global level, as most of the climate compensation projects are in the Global South. However, regulating climate compensation would ensure that they are providing carbon reduction as promised.

In our study, public perception varied from strong emphasis on climate action to denial of anthropogenic climate change. The respondents who emphasized the urgency of climate action were most concerned about the impacts of climate change. For this group considering climate justice (e.g., Gardiner, 2011; Schlosberg and Collins, 2014) in a form of effective and binding climate policy and more possibilities to participate would increase the acceptance of the Climate Change Amendment. However, this “systemic change now” group of respondents consists of small group practicing green lifestyle. Similarly, study of public perception of UK climate policy showed that most of the public attributes climate change to human activities, and a small group of citizens practicing a green lifestyle is extremely concerned about climate change (Upham et al., 2011).

Previous studies have shown a strong link between perceived climate concern and climate responsibility (e.g., Hagen et al., 2016; Rhodes et al., 2017; Pohjolainen et al., 2021). Our analysis adds to this pool of studies on climate concern and responsibility, as we revealed a group of respondents that emphasized climate change mitigation as an economic possibility and relied on climate expertise, which was most positive toward their possibilities to participate in climate policy and were positive toward binding climate policy, including the carbon neutrality 2035 target. In our analysis belonging to expert community or trust in climate experts enhances the support to binding climate policy.

Procedural values gained through transparency and openness of information, opportunities to participate in legislative drafting can increase the acceptance of legislation and support its implementation (e.g., OECD., 2010; Keinänen and Kemiläinen, 2016; Meriläinen et al., 2020; Albrecht et al., 2021). Our analysis revealed a group of respondents highlighted the citizen participation and democratic goals of legislative consultations that was particularly concerned about these procedural values. Most respondents were critical toward the possibilities to participate and transparency of Finnish Climate Change Act amendment. Yet most respondents support the objectives of the amendment. More research is needed on whether opportunities to participate would increase the acceptance of the legislation, as most empirical studies focus on particular institutional device, e.g., e-deliberation (Jäske and Setälä, 2019).

The survey results show that young people were the most often mentioned group which should have more possibilities to participate. Young people are often overly concerned about the impacts of climate change, they use digital platforms and participate in a cause-oriented way (Allaste and Cairns, 2016; Harris, 2016; Bowman, 2019; Albrecht et al., 2021). Especially for the respondents between 18 and 25 increased ambition of climate policy, such as integrating the 2035 climate neutrality objective would contribute to acceptance of climate policy. Our findings also suggest that sufficient information in an understandable form would improve the acceptability of climate policy. This is in line with findings of a literature review on carbon pricing policies, that states that people's satisfaction with information provided by the government increases acceptability (Maestre-Andrés et al., 2019).

We also revealed a group of respondents that favors economic competitiveness to binding climate policy. These respondents were stating that economic incentives are useful, the freedoms of citizens must be maintained, and landowners' rights must be protected. In previous research, Finland has been described as a country with strong agriculture and forestry advocacy and a corporatist policy style (e.g., Teräväinen-Litardo, 2015; Harrinkari et al., 2016; Gronow and Ylä-Anttila, 2019). According to Gronow and Ylä-Anttila (2019), this can, contrary to the expectations of good climate performance, hinder climate policy development, as environmental NGOs are toothless when it comes to initiating policies that motivate businesses to reduce their emissions. The perceptions on the role of forests in the Finnish climate policy varied from the economic forestry to banning clear cuts and forest conservation, which is similar with findings from a study by Takala et al. (2017), in which Finnish forest owners' discourses range from forest management and the economic use of forests to forest conservation.

Finally, a significant group of respondents adopted a skeptical attitude toward human-caused climate change. Climate change as an abstract and complex phenomenon is an ideal target for populists to claim that this issue is an elitist project (Huber et al., 2020). Anti-climate rhetoric, which portrays climate change as an abstract and technical concern of the cosmopolitan elite, has become increasingly important for right-wing populist parties (Duijndam and van Beukering, 2020). This anti-climate rhetoric and trolling was visible in the survey, although it did remain marginal. Achieving transition to climate neutrality is not only in the hands of the group of citizens and expert-community that listens to climate science. In an Australian study on climate expertise (Tangley, 2018), the rhetoric's, which bases of climate science and modeling and has been applied by political elites, has been counterproductive for energy transition and wider perspective on resilience and climate adaptation is needed. The challenge lies in getting the policy makers and society on board.

We have analyzed public perception on procedural values and proposed outcomes in Finnish Climate Change Act amendment. We have identified distinct groups of respondents, which have different interpretations of procedural justice. Sometimes those perceptions are similar across groups that have hugely different beliefs i.e., climate skeptics and structural change now groups feel excluded and argue that only certain types of actors are included. We also noticed that respondents tended to favor their own perspectives, when reasoning for the transparency, participation, acceptance, and objectives of the regulatory amendment. The objectives of the proposal were well-received among the public although the transparency and participatory opportunities of legislative drafting were criticized. According to our findings, youth was a particular group which should have more possibilities to participate. They are often minor and therefore not able to participate through traditional democracy. In addition, they are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as they must live longer with the consequences.

Our analysis adds to the literature that emphasizes procedural values gained through transparency and openness of information, opportunities to participate in legislative drafting (e.g., Keinänen and Kemiläinen, 2016; Meriläinen et al., 2020; Albrecht et al., 2021). In the context of Finnish legislative drafting, there is evidence that acceptance of legislation increases when public consultations are organized in a manner such that the participants feel that they have been heard (Ahtonen and Keinänen, 2012). Despite of this, the Finnish authorities have been reluctant to integrate the results of public hearings in legislation (Meriläinen et al., 2020). In this regard, it would be useful to evaluate, which, if any of these statements from the public translate to the actual paragraphs of law (see Airaksinen and Albrecht, 2019). In addition, the guidelines for better regulation emphasize transparency through consultation and communication as a driver for effective regulation. Therefore, the findings of this study can support the planning of an ex-ante impact assessment of regulations. Furthermore, we suggest that a wider perspective on climate justice would be beneficial within climate policy and law. Climate mitigation and adaptation is gaining importance with the aim to achieve Paris Agreement's targets (Michaelowa and Allen, 2018; Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, 2019). Keeping this in mind, the democratic institutions need to take an active role toward drafting legislation that supports climate action.

The data supporting the conclusion can be made available upon request from the Ministry of the Environment, Finland and the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

EA as a lead author initiated this manuscript and all authors participated in the planning and writing of it. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research has been funded by the Academy of Finland, All Youth Want to Rule Their World research project (grant nos. 312689 and 326604). This work was funded by the Strategic Research Council at the Academy of Finland (grant no. 313013).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2021.657241/full#supplementary-material

Ageyman, J., and Evans, B. (2004). ‘Just sustainability’ The emerging discourse of environmental justice in Britain? Geogr. J. 170, 155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.00117.x

Ahtonen R, and Keinnen A. (2012). The impact of stakeholders on legislative drafting: empirical analysis on committee hearings (Sidosryhmien vaikuttaminen lainvalmisteluun: empiirinen analyysi valiokuntakuulemisista). Edilex–sarja 2012/5. (Helsinki: Edita Publishing Oy)

Airaksinen, J., and Albrecht, E. (2019). Arguments and their effects-A case study on drafting the legislation on the environmental impacts of peat extraction in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 226, 1004–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.161

Albrecht E, Leppäkoski E, Vaara E, Meriläinen N, and Viljanen J. Youth participation in Climate Act Amendment. (Nuorten osallistuminen ilmastolain valmisteluun). Nuorisotutkimus hbox, (2021) 25:46–61. (Turku: Hansaprint).

Albrecht, E., Tokola, N., Leppäkoski, E., Sinkkonen, J., Mustalahti, I., Ratamäki, O., et al. (2020a). “Nuorten ilmastohuoli ja ympäristökansalaisuuden muotoutuminen,” in Maapallon tulevaisuus ja lapsen oikeudet. Lapsiasiavaltuutetun toimiston julkaisuja, eds Pekkarinen, E. and Tuukkanen T. (Turenki: Hansaprint), 99–110.

Albrecht, E., Viljanen, J., and Vaara, E. (2020b). Ilmastopolitiikan hyväksyttävyys ja kansalaisosallistuminen ilmastolain uudistuksessa. Helsinki: Ympäristöpolitiikan ja -oikeuden vuosikirja XIII, 369, 369–415.

Allaste, A.-A., and Cairns, D. (2016). “Understanding online activism in a transition society,” in Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood, ed F. Andy (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 308–315.

Andersson, A. (2009). Media, politics, and climate change: towards a new research agenda. Sociol. Compass 3, 166–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x

Bäckstrand, K., Zelli, F., and Schleifer, P. (2018). “Legitimacy and accountability in polycentric climate governance In Jordan,” in Governing climate change. Polycentricity in Action? eds Huitema, A. D., van Asselt, H., and Forster, J. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 338–356. doi: 10.1017/9781108284646.020

Bodansky, D. (2016). The legal character of the Paris Agreement. RECIEL. 25, 142–150. doi: 10.1111/reel.12154

Bollettino, V., Alcayna-Stevens, T., Sharma, M., Dy, P., Pham, P., and Vinck, P. (2020). Public perception of climate change and disaster preparedness: evidence from the Philippines. Clim. Risk Manag. 30, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2020.100250

Bowman, B. (2019). Imagining future worlds alongside young climate activists: a new framework for research. Fennia 197, 295–230. doi: 10.11143/fennia.85151

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information. Thematic Analysis and Code Development. London: Sage Publications.

Bunders, J. F., Broerse, J. E., Keil, F., Pohl, C., and Scholz, R. W. Z. (2010). “How can transdisciplinary research contribute to knowledge democracy?” in Knowledge Democracy, ed R. in 't Veld (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 125–152. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-11381-9_11

Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L. P., Upham, P. (2015). International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. WIREs Clim Change 6, 35–61. doi: 10.1002/wcc.321

Creswell, J. W., Norman, K., and Denzin, Y. S. (2011). “Controversies in mixed methods research,” in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (Los Angeles; London; New Delhi; Singapore; Washington, DC: Sage), 269–284.

Crona, B., Wutich, A., Brewis, A., and Gartin, M. (2013). Perceptions of climate change: linking local and global perceptions through a cultural knowledge approach. Clim. Change 119, 519–531. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0708-5

Devine-Wright, P., Ryder, S., Dickie, J., Evensen, D., Varley, A., and Whitmarsh, L. (2021). Induced seismicity or political ploy?: using a novel mix of methods to identify multiple publics and track responses over time to shale gas policy change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 81:102247. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102247

Duijndam, S., and van Beukering, P. (2020). Understanding public concern about climate change in Europe, 2008–2017: the influence of economic factors and right-wing populism. Clim. Policy 1–15. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2020.1831431

Duwe M, Evans N. Climate Laws in Europe: Good Practices in Net-Zero Management. Climate policy (2020) 21:353–67. Available Online at: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2020/climatelawsineurope_fullreport_0.pdf

Emami, P., Xu, W., Bjornlund, H., and Johnston, T. (2015). A framework for assessing the procedural justice in integrated resource planning processes. Sustain. Dev. Plann. 7, 119–130. doi: 10.2495/SDP150101

European Commission (2020). A European Grean Deal. Retreived from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en. (accessed April 23, 2020).

European Council (2021). Fit for 55 – The EU's Plan for Green transition. Brussels : European Council of the European Union (2021). Available Online at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/.

Finnish Council of State. (2016). Finnish Council of State Resolution of Guidelines for Public Hearing in Law-Drafting 4, 2.2016. (Valtioneuvoston periaatepäätös säädösvalmistelun kuulemisohjeesta). Helsinki. Available online at: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/76626 (accessed November 09, 2020).

Finnish government. (2019). Inclusive and Competent Finland—a Socially, Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Society. Helsinki: Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin's Government 2019.

Fraser, N. (2001). Recognition without ethics? Theory Cult. Soc. 18, 21–42. doi: 10.1177/02632760122051760

Gardiner, S. (2011). “Climate justice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, eds J. Dryzek, R. Norgaard, and D. Schlosberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 309–322. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0021

Goedkoop, F., and Devine-Wright, P. (2016). Partnership or placation? The role of trust and justice in the shared ownership of renewable energy projects. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 17, 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2016.04.021

Gronow, A., and Ylä-Anttila, T. (2019). Cooptation of ENGOs or treadmill of production? Advocacy coalitions and climate change policy in Finland. Policy Stud. J. 47, 860–881. doi: 10.1111/psj.12185

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied Thematic Analysis. London: Sage Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436

Hagen, B., Middal, A., and Pijawka, D. (2016). European climate change perceptions: public support for mitigation and adaptation policies. Environ. Policy Govern. 26, 170–183. doi: 10.1002/eet.1701

Harrinkari, T., Katila, P., and Karppinen, H. (2016). Stakeholder coalition in forest politics: revision of Finnish Forest Act. For. Policy Econ. 67, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2016.02.006

Harris, A. (2016). “Young people, politics and citizenship,” in Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood, ed F. Andy (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 295–300.

Holifield, R. (2001). Defining environmental justice and environmental racism. Urban Geogr. 22 78–90. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.22.1.78

Honneth, A. (2004). Recognition and justice - outline of a plural theory of justice. Acta Sociol. 47, 351–364. doi: 10.1177/0001699304048668

Horton, D. (2006). “Demonstrating environmental citizenship? A study of everyday life among green activists,” in Environmental Citizenship, eds A. Dobson and D. Bell (Cambridge, MA; London: The MIT Press), 127–150.

Huber, R., Fesenfeld, L., and Bernauer, T. (2020). Political populism, responsiveness, and public support for climate mitigation. Clim. Policy 20, 373–386. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2020.1736490

Hurmerinta-Peltomaki, L., and Nummela, N. (2006). Mixed methods in international business research: a value-added perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 46, 439–459. doi: 10.1007/s11575-006-0100-z

Jäske, M. and Setälä, M. (2019). A functionalist approach to democratic innovations. Represent. J. Represent. Democr. 56, 467–483. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1691639

Keinänen, A., and Kemiläinen, M. (2016). Filing in the feedback from public consultations: does the transparency of legislative drafting actualize? (Lausunnosta saadun palautteen kirjaaminen lainvalmistelussa: Toteutuuko lainvalmistelun avoimuus?). Helsinki: Edilex Edita Publishing Oy 2016/29, 1–22.

Klinsky, S., and Dowlatabadi, H. (2009). Conceptualizations of justice in climate policy. Clim. Policy 9, 88–108. doi: 10.3763/cpol.2008.0583b

Klinsky, S., Roberts, T., Huq, S., Okereke, C., Newell, P., Dauvergne, P., et al. (2017). Why equity is fundamental in climate change policy research. Glob. Environ. Change 44, 170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.08.002

Lawrence, R. L., Daniels, S. E., and Stankey, G. H. (1997). procedural justice and public involvement in natural resource decision making. Soc. Nat. Resour. 10, 577–589. doi: 10.1080/08941929709381054

Lind, E. A., and Tyler, T. R. (1988). The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. New York, NY: Plenum Press; Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2115-4

Maestre-Andr?s, S., Drews, S., and ja van den Bergh, J. (2019). Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: a review of the literature. Clim. Pol. 19, 1186–1204. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2019.1639490

Markkanen, S., and Anger-Kraavi, A. (2019). Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality. Clim. Policy 19, 827–844. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2019.1596873

Martinez-Alier, J. (2002). The Environmentalism of the Poor – A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi: 10.4337/9781843765486

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H. O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P. R., et al. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5° C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (p. 32). Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization.

McCauley, D., and Heffron, R. J. (2018). Just transition: integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy 119, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

McKim, C. A. (2015). The value of mixed methods research: a mixed methods study. J. Mixed Methods Res. 11, 202–222. doi: 10.1177/1558689815607096

Meriläinen, M., Heiskanen, H.-E., and Viljanen, J. (2020). Participation of young people in legislative processes: a case study of the General Upper Secondary School Act in Finland—a school bullying narrative. J. Legisl. Stud. 1–32. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2020.1826095. [Epub ahead of print].

Michaelowa, A., and Allen, M. (2018). Policy instruments for limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C – can humanity rise to the challenge? Clim. Policy 18, 275–286. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1426977

OECD. (2010). Better Regulation in Europe. Finland. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/betterregulationineuropefinland.htm. (accessed November 09, 2020).

Paavola, J. (2005). Seeking justice: international environmental governance and climate change. Globalizations 2, 309–322. doi: 10.1080/14747730500367850

Paavola, J. (2008). Science and social justice in the governance of adaptation to climate change. Environ. Politics 17, 644–659. doi: 10.1080/09644010802193609

Pohjolainen, P., Kukkonen, I., Jokinen, P., Poortinga, W., Ogunbode, C. A., Böhm, G., et al. (2021). The role of national affluence, carbon emissions, and democracy in Europeans' climate perceptions, innovation. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2021.1909465

Pölönen, I. (2014). The Finnish Climate Change Act: architecture, functions, and challenges. Clim. Law 4, 301–326. doi: 10.1163/18786561-00404006

Popke, J., Curtis, S., and Gamble, D. W. (2016). A social justice framing of climate change discourse and policy: adaptation, resilience and vulnerability in a Jamaican agricultural landscape. Geoforum 73, 70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.003

Reed, M. G., and Abernethy, P. (2018). Facilitating co-production of transdisciplinary knowledge for sustainability: working with Canadian Biosphere Reserve practitioners. Soc. Nat. Resour. 31, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2017.1383545

Rhodes, E., Axsen, J., and Jaccard, M. (2017). Exploring citizen support for different types of climate policy. Ecol. Econ. 137, 56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.027

Robinson, M., and Shine, T. (2018). Achieving a climate justice pathway to 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 564–569. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0189-7

Sanson, A. V., and Burke, S. E. L. (2020). “Climate change and children: an issue of intergenerational justice,” in Children and Peace. Peace Psychology Book Series, eds N. Balvin and D. Christie (Cham: Springer), 343–362. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-22176-8_21

Schlosberg, B., and Collins, L. B. (2014). From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of climate justice. Wires Clim. Change 5, 359–374. doi: 10.1002/wcc.275

Schlosberg, D. (1999). Environmental Justice and the New Pluralism: The Challenge of Difference for Environmentalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schlosberg, D. (2013). Theorizing environmental justice: the expanding sphere of the discourse. Environ. Politics 22, 37–55. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.755387

Schrader-Frechette, K. S. (2005). Environmental justice: Creating Equality, Reclaiming Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takala, T., Hujala, M., Tanskanen, M., and Tikkanen, J. (2017). The order of forest owners' discourses: hegemonic and marginalized truths about the forest and forest ownership. J. Rural Stud. 51, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.01.014

Tala, J. (2005). Drafting the Impacts of Law. (Lakien laadinta ja vaikutukset). Helsinki: Edita Publishing.

Tangley, P. (2018). Between conflation and denial – the politics of climate expertise in Australia. Austral. J. Political Sci. 54, 131–149. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2018.1551482

Teräväinen-Litardo, T. (2015). “Negotiating green growth as a pathway towards sustainable transition in Finland,” in Rethinking the Green State. Environmental Governance Towards Climate and Sustainability Transitions in Finland, eds K. Bäckstrand and A. Kronsell (London: Routledge), 174–190. doi: 10.4324/9781315761978-21

Thibaut, J., Walker, L., LaTour, S., and Houlden, P. (1974). Procedural justice as fairness. Stanford Law Rev. 26, 1271–1290. doi: 10.2307/1227990

UNFCC. (2015). “Paris agreement,” in Conference of parties. Twenty-first session, Paris, 30 November to 11 December 2015. Paris: FCCC/CP/2015/L.9

Upham, P., Dendler, L., and Bleda, M. (2011). Carbon labelling of grocery products: public perceptions and potential emissions reductions. J. Clean. Prod. 19, 348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.05.014

Vesa, J., Kantola, A., and Skorkjær Binderkrantz, A. (2018). A stronghold of routine corporatism? The involvement of interest groups in policy making in Finland. Scand. Political Stud. 41, 239–262. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12128

Vihma, A., Reischl, G., and Andersen, A. N. (2021). A climate backlash: comparing populist parties' climate policies in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. J. Environ. Dev. 30, 219–239. doi: 10.1177/10704965211027748

Vona, F. (2019). Job losses and political acceptability of climate policies: why the ‘job-killing’ argument is so persistent and how to overturn it. Clim. Policy 19, 524–532. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1532871

Vringer, K., and Carabain, C. L. (2020). Measuring the legitimacy of energy transition policy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy 138:111229. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111229

Walker, C. (2020). Uneven solidarity: the school strikes for climate in global and intergenerational perspective. Sustain. Earth 3:5. doi: 10.1186/s42055-020-00024-3

Weikmans, R., van Asselt, H., and Roberts, J. T. (2020). Transparency requirements under the Paris Agreement and their (un)likely impact on strengthening the ambition of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Clim.ate Policy 20, 511–526. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2019.1695571

Wetts, R. (2019). Models and morals: elite-oriented and value-neutral discourse dominates American organizations' framings of climate change. Soc. Forces. 98, 1339–1369. doi: 10.1093/sf/soz027

Williams, S., and Doyon, A. (2019). Justice in energy transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 31, 144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.12.001

YouGov (2014). Tracking British attitudes to climate change. Retreived from: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2014/04/16/ (accessed August 27, 2021).

Keywords: climate policy, public perception, procedural justice, carbon neutrality, Finnish Climate Change Act

Citation: Albrecht E, Pietilä I and Saarela S-R (2022) Public Perceptions on the Procedural Values and Proposed Outcomes of the Finnish Climate Change Act Amendment. Front. Clim. 3:657241. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2021.657241

Received: 22 January 2021; Accepted: 06 December 2021;

Published: 10 January 2022.

Edited by:

Nicole Lisa Klenk, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Stacia Ryder, University of Exeter, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Albrecht, Pietilä and Saarela. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eerika Albrecht, ZWVyaWthLmFsYnJlY2h0QHVlZi5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.