- LVR Clinic Duesseldorf, Department for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy, Clinics of the Heinrich-Heine-University, Duesseldorf, Germany

This study presents the validation of the parent version of the Inventory of School Attendance Problems (ISAP-P), which assesses a broad spectrum of symptoms associated with school attendance problems. A model with 49 items loading on 13 factors derived from the child version showed an acceptable fit (N = 296). Correlations with other measures indicated convergent and discriminant validity of the scales, but associations with the extent of school absences were not detected. Concordant scales of the child vs. parent version were correlated in the expected directions, but some scales showed low interrater agreement. Albeit these initial results support the validity of the ISAP parent version, further studies on its psychometric properties as well as on children's and parents diverging views on SAPs are needed.

Introduction

Students who are absent from school to a problematic degree have been found to have an elevated risk for mental illnesses, unemployment, drug misuse, school dropout, and many other psychosocial problems across the lifespan (1–3). School attendance problems (SAPs) can occur in many different forms. Recent conceptualizations (4) distinguish between school exclusion (school absences initiated by the school, e.g., because of misbehavior), parental withdrawal (parent motivated absences, e.g., keeping the child at home in order to help there), truancy (child-motivated, generally unexcused school absence due to a lack of motivation and without knowledge of the parents, often accompanied by externalizing symptoms) and school refusal (child-motivated, generally excused school absence with knowledge of the parents because of internalizing symptoms such as anxiety, psychosomatic complaints, or depression).

While consensus regarding these definitions has fostered research into SAPs in the recent years, most researchers acknowledge that these constructs can overlap, coexist, or influence one another. E.g., initial truancy can develop into school refusal, and school absences due to depressive symptoms such as loss of energy and interest can be misinterpreted as a part of truant behavior or a conduct disorder (4, 5). Without a thorough and differentiated assessment of the heterogeneous nature of SAPs, interventions cannot be tailored according to the individual needs of school absent youths. Therefore, several instruments with different foci have been developed to obtain a more detailed picture of SAPs [see (6), for a comprehensive review]. The School Non-Attendance Checklist [SNACK (4);] is a short screening tool which can be used to categorize SAPs according to their reasons (parent report) and is the only measure that not only assesses child-motivated SAPs (truancy, school refusal), but also includes items for school exclusion and parental withdrawal. The majority of the available questionnaires, though, focusses on child-motivated SAPs. Instruments like the widely used SRAS-R [School Refusal Assessment Scale Revised; (7, 8)] or the ARSNA [Assessing Reasons for School Non-Attendance; (9)] subsume different aspects of SAPs under rather broad categories or dimensions (e.g., avoidance of negative affect, escape from aversive social situations, pursuit of attention, and pursuit of tangible reinforcement as functions of SAPs in the SRAS-R). The SCREEN [School Refusal Evaluation Scale (10)] and the SEQ-SS [Self-efficacy Questionnaire for School Situations (11)], on the other hand, can be used for an in-depth assessment of selected features of SAPs (e.g., SCREEN-subscale “Anxious Anticipation” as a facet of school refusal).

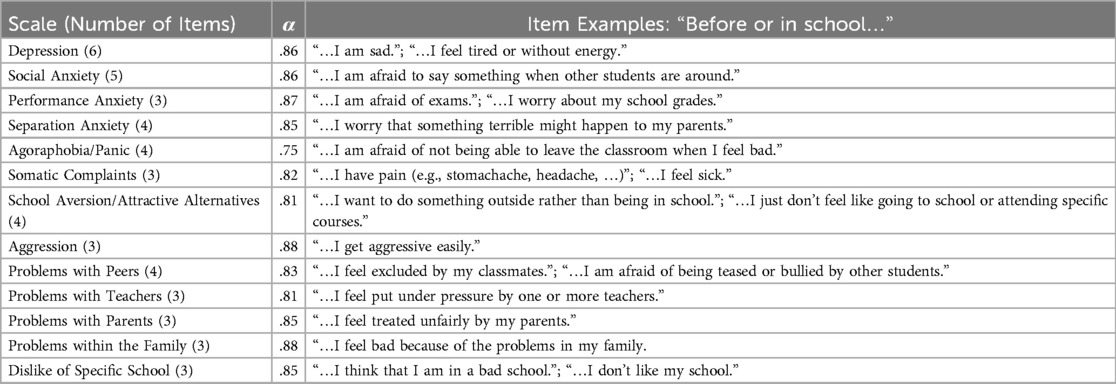

The Inventory of School Attendance Problems [ISAP, (12)] complements and extends the range of the existing measures by offering both a comprehensive and differentiated screening of SAPs. It incorporates the most relevant aspects of SAPs as separate scales, which assess specific symptoms often associated with SAPs such as depression, social phobia, separation anxiety, and somatic complaints as well as the impact of common stressors associated with SAPs (e.g., bullying, intrafamily problems; see Table 1). Its items were constructed inductively based on answers of patients of a specialized outpatient unit for SAPs during clinical exploration. It offers an integrative assessment of both the presence of a given symptom prior to or at school and its impact on school attendance. In the left column, under the heading “Before or in school/school time…”, the items are presented (e.g., “…I feel sad.”). In the middle column, students first rate how good an item applies to them (heading “Applies to me”). Then, in the right column, students rate how strongly this item is connected to their SAPs (heading “That's why I miss school/attending school is hard for me”; response scale for both questions: never—sometimes—often—most of the time). Separate scores for symptom presence and symptom impact can be calculated for each scale, which enables practitioners to rank symptoms according to their impact on the student's SAPs and thus to identify the most pivotal targets for interventions. For the statistical analyses, however, testlets were formed for each item by aggregating the values of both response scales (13).

Explorative factor analyses (N = 245 patients, item pool: 124 items/testlets) resulted in 48 items loading on 13 factors. These 13 scales assess externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as emotional distress resulting from stressors in the school and family context (see Table 1). The pattern of the scales' associations with the Youth Self Report (YSR), a German version of the SRAS, and with the extent of school absenteeism supported their construct validity. For example, internalizing symptoms in the YSR and SRAS (e.g., scale “Avoidance of Negative Affect”) were associated with ISAP-scales measuring internalizing symptoms, while the scales aggression and school aversion showed stronger correlations with externalizing symptoms (YSR) and the SRAS-scale “Pursuit of Tangible Rewards”. Furthermore, most of the scales showed weak to moderate positive associations with the extent of school absenteeism.

Up to date only a child version of the ISAP is available, so that the perspective of the parents on their child's SAPs is missing. The multi-informant assessment approach is the gold standard in child psychology (14), and models and studies on SAPs empathize their embeddedness in interacting social contexts (15, 16). Parents are one of the most important proximal factors of SAPs; thus, the aim of this study is to validate the parent version of the ISAP (ISAP-P). As a content analysis of clinical parent interviews about their perception of their child's SAPs during the construction phase of the ISAP-P (see below) yielded the same categories than the child interviews for the youth version (12), we expected

- A confirmation of the 13 factors for the parent version (factorial validity).

- Associations with the CBCL (discriminant validity), the parent version of the SRAS (convergent validity), and the extent of school absenteeism (criterial validity) comparable to those obtained for the ISAP child version with respective child versions of the measures mentioned above.

Method

Participants

Approval by the ethics committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen and written informed consent from patients and their parents was obtained prior to data collection. Criteria for inclusion were being a parent with sufficient language and reading skills of a child with SAPs, age ≥ 8, an IQ > 69, and no severe mental illness (e.g., psychosis). Only questionnaires with no missing answers were included.

The final sample consisted of 296 parents of patients of a specialized outpatient unit for children and adolescents with SAPs of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Essen, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. Either a single parent or both parents together filled out the ISAP. (only one questionnaire per child). 56% of their children were male; their mean age was 14.4 years (SD = 3.51, range 8–18). 3.1% reported school absences between 0 and 4 school days during the last 12 school weeks, 18.6% up to 12, 27.7% up to 36, and 10.8% up to 48 school days. 15.2% reported that their child missed more than 48 days and 23.3% stated that their child did not attend school at all (1.3% missing values).

Measures

ISAP-P

The construction of items of the parent version followed the procedure used for the child version. Content analysis of clinical parent interviews prior to item construction (N = 162) yielded twenty-five aspects of SAPs identical to those obtained for the child version (12). For each aspect, three to five items were generated, resulting in an item pool of 124 items parallel to those of the child version. Out of these, the 48 items parallel to those of the final ISAP child version were used for the analyses.

Other measures

A modified German version of the parent version of the School Refusal Assessment Scale (ESV-P-R) was administered (17). Its three scales measure three symptom clusters of SAPs and their associated functions in terms of positive or negative reinforcement: Separation Anxiety/Attention Seeking Behavior, School Anxiety/Avoidance of Negative Affect, and Alternative Activities/Tangible Rewards. The German version of the Child Behavior Checklist was used to assess general psychopathology [CBCL; (18), scales: Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, Anxiety and Depression, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behavior, Delinquent Behavior]. The extent of school absence during the last twelve weeks was measured by a question on the first page of the ISAP-P (0–4 days—all days, see above). For a comparison of the child and the parent version of the ISAP, N = 145 ISAP child versions were available.

Data analysis

In order to test if the factor structure of the ISAP child version can be replicated for the parent version, we used explorative structural equation modelling (19). This approach integrates the advantages of explorative and confirmative factor analysis. It is recommended for testing the structure of measures at a rather early stage of development with high numbers of assumed factors, as it allows integrating cross loadings in the model specification (20). This approach was chosen as the current stage of development of the ISAP-P is somewhere between exploration (parents as different source of information, high probability of necessary changes compared to the child version) and confirmative validation of its structure (approach to data analysis informed by the results of the child version, preselected items, 13 factors expected). The characteristics of the resulting scales and their construct validity were analyzed using descriptive statistics, T-tests, and correlations.

Results and discussion

Internal structure

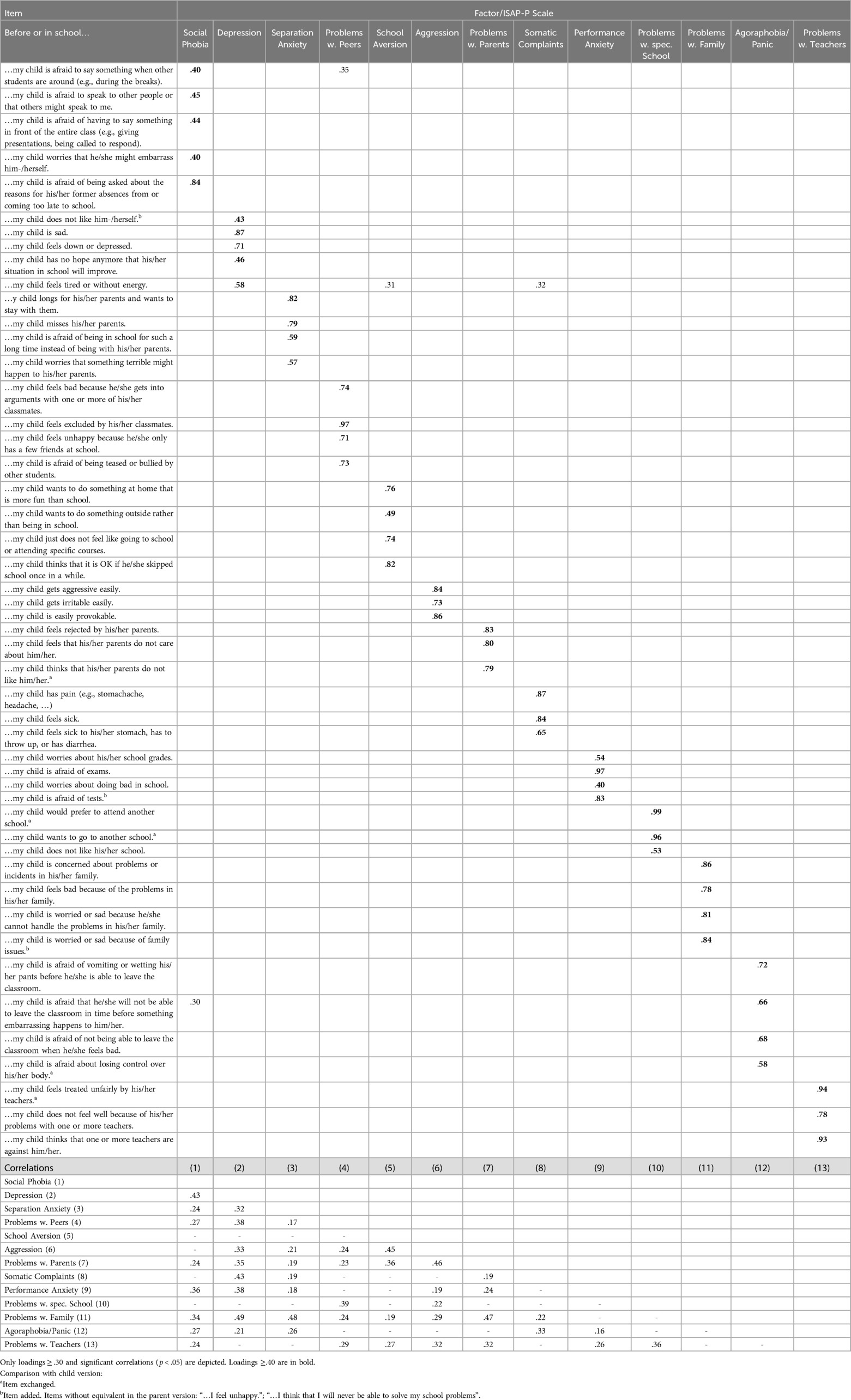

Initial analyses of the 48 items parallel to those of the child version showed an inadequate fit of the model. Items with ambiguous loading patterns were deleted or tentatively replaced by other items from the item pool generated for the same SAP aspect or scale (see Table 2 for details). E.g., the item “…my child feels unhappy.” of the scale “Depression” was replaced by the item “…my child does not like him-/herself.”. Furthermore, one item was added to each of the scales “Problems within the Family” and “Performance Anxiety” because they showed an insufficient differentiation with regard to other scales (“Problems with Parents” and 'Social Phobia', respectively, see Table 2). Following the modification indices, ten covariances between error terms of items from the same scale, with identical item stems, and very similar wording were modelled. These modifications led to an acceptable model fit (CFI = .93; RMSEA = 0.05) and clear loading patterns (see Table 2), while other tested model specifications with less or more factors showed an unacceptable fit (e.g., models with 9, 10,11, or 14 factors: CFI < .85). Despite the small item numbers, for all scales Cronbach's α was ≥.75. As expected, the integration of cross loadings resulted in decreased scale intercorrelations compared to those of the child version (12). While the pattern of most scale intercorrelations mirrored the respective scales' affiliation to the internalizing vs. externalizing spectrum, the scales measuring stressors in the family or school context showed weak to moderate associations with both internalizing and externalizing scales.

Construct validity

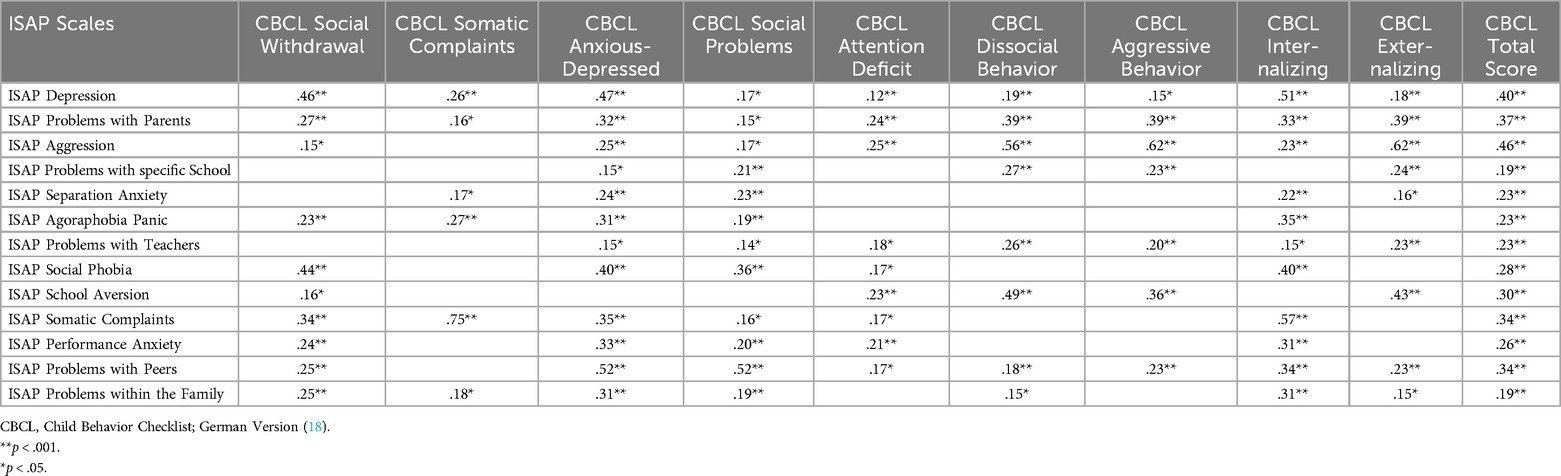

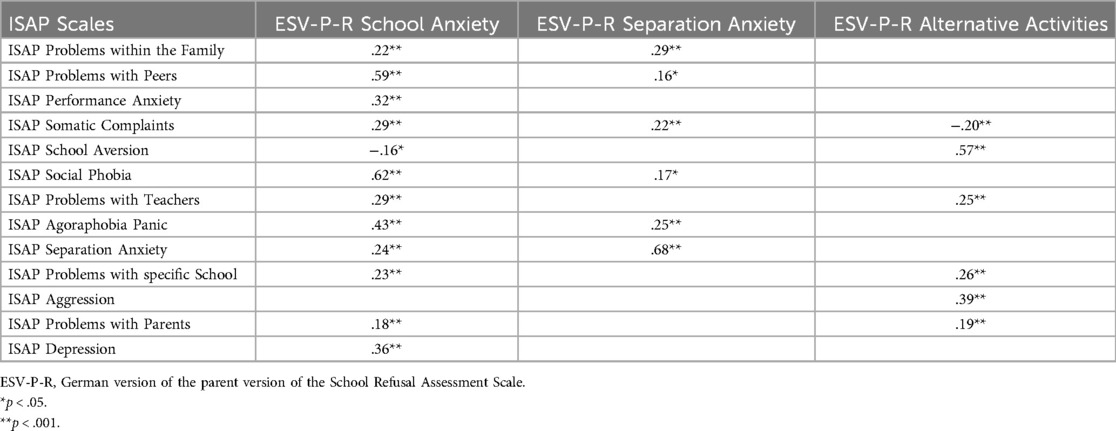

The correlations between the ISAP, the CBCL, the ESV-P-R, and the extent of school absences are depicted in Tables 3, 4. Regarding convergent validity, the expected pattern of associations was obtained. E.g., school anxiety as measured by the ESV-P-R correlated strongly with the ISAP-P scales “Social Phobia” and “Peer Problems”, the ESV-P-R scale “Alternative Activities” was associated with the ISAP-P scales “School Aversion”, and the separation anxiety scales of both measures were highly correlated. ISAP-P scales measuring internalizing symptoms such as depression and anxiety showed marked correlations with the respective CBCL scales, while the ISAP-P scales “School Aversion” and “Aggression” showed strong associations with the CBCL scales measuring externalizing symptoms. The discriminant validity was supported by the magnitude of these associations, which was only moderate (vs. high). Furthermore, for the ISAP-P scales measuring stressors in the family and school context, which have no equivalent in the CBCL, the weakest associations were observed.

In contrast to the ISAP child version and to findings regarding the scales of the parent version of the SRAS (8), none of the ISAP-P scales showed significant associations with the extent of school absenteeism. Since a parent rating of school absences has been used in this study, these findings could be attributable to a lack of parental knowledge about the real extent of school absenteeism of their child (21). Furthermore, other parental factors that were not assessed and that are known to be associated with school absences (e.g., socioeconomic status) could mediate or moderate the association between the ISAP-P and school attendance rates (22).

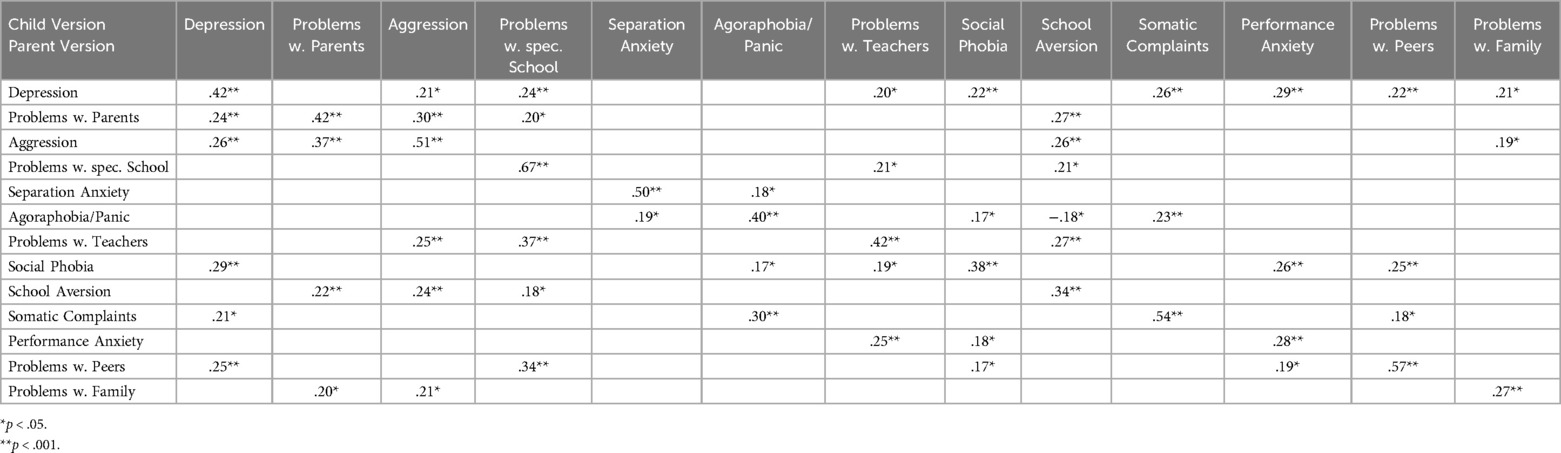

The analysis of the interrater agreement in terms of associations between parallel scales of the parent vs. child version of the ISAP yielded mostly moderate to strong correlations (see Table 5). However, for some scales (e.g., Problems within the Family, Performance Anxiety), only weak to moderate correlations were obtained. Comparisons of the means of concordant parent vs. child scales showed significantly higher means of the scales of the parent version in all cases (T values between 4.49 and 14.31, all p < .0001). This could reflect parents' high levels of worries and distress due to their child's SAPs, possible dissimulation of some children, or conflicts between parent and child (23).

Questions regarding the differences between child and parent version remain to be answered by future research, which should also address the major limitations of this study. Besides the low validity of the measure of school absences mentioned above, important information about the sample is missing (e.g., diagnoses, socioeconomic status), and due to its clinical nature (predominantly youths with severe SAPs) conclusions regarding the factor structure and the construct validity of the ISAP in the general student population cannot be drawn. The factor structure of the child version, however, has recently been confirmed in community samples (24, 25).

Although preliminary, the first results of the evaluation of the ISAP-P indicate that it is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the parent perspective on students' SAPs. Integrating the parents' view in the diagnostic process is essential. Possible “blind spots” or biases of the children's reports can be detected (and vice versa); furthermore, the parent's reports can shed light on their subjective theories about the nature of the problems of their child. Discrepancies between the child's and the parents' conceptualization of the SAP can be detected and integrated into a shared model, which is the prerequisite for the establishment of a treatment plan that both child and parents can agree on (26). Furthermore, results of the ISAP-P can inform psychoeducation and sensitization of parents with regard to their child's problems as well as the design and implementation of parent- or family-centered treatment modules for SAPs. Future studies should cross-validate the ISAP-P in community or school samples and across different cultural contexts. Beyond that, longitudinal studies could use the ISAP and the ISAP-P to investigate the development of SAPs throughout childhood and adolescence from different perspectives, whereas interventional studies could address the potential of the ISAP and the ISAP-P to inform the development of multimodal treatments for SAPs and to evaluate their effectiveness.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed tobWFydGluLmtub2xsbWFubjJAbHZyLmRl.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from patients and their parents was obtained prior to data collection.

Author contributions

MK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. VR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients and their parents who took part in this study. Furthermore, we would like to thank Prof. Dr. Christoph U. Correll (Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy, Charité Clinic, Berlin) for his help on the translation of the items of the ISAP into English.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Elliot JG, Place M. Practitioner review: school refusal: developments in conceptualisation and treatment since 2000. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2019) 60(1):4–15. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12848

2. Kearney CA. School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: a contemporary review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2008) 28:451–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012

3. Knollmann M, Knoll S, Reissner V, Metzelaars J, Hebebrand J. School avoidance from the point of view of child and adolescent psychiatry: symptomatology, development, course, and treatment. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Int. (2010) 107:43–9. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0043

4. Heyne D, Gren-Landell M, Melvin G, Gentle-Genitty C. Differentiation between school attendance problems: why and how? Cogn Behav Pract. (2019) 26(1):8–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.006

5. Havik T, Ingul JM. How to understand school refusal. Front Educ. (2021) 6:715177. Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.715177

6. Gonzálvez C, Kearney CA, Vicent M, Sanmartín R. Assessing school attendance problems: a critical systematic review of questionnaires. Int J Educ Res. (2021) 105:101702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101702

7. Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the school refusal assessment scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. (2002) 24:235–45. doi: 10.1023/A:1020774932043

8. Kearney CA. Forms and functions of school refusal behavior in youth: an empirical analysis of absenteeism severity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2007) 48(1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01634.x

9. Havik T, Bru E, Estesvåg SK. Assessing reasons for school non-attendance. Scand J Educ Res. (2015) 59(3):316–36. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2014.904424

10. Gallé-Tessonneau M, Gana K. Development and validation of the school refusal evaluation scale for adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. (2019) 44(2):153–63. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy061

11. Heyne D, King N, Tonge B, Rollings S, Pritchard M, Young D, et al. The self-efficacy questionnaire for school situations: development and psychometric evaluation. Behav Change. (1998) 15(1):31–40. doi: 10.1017/S081348390000588X

12. Knollmann M, Reissner V, Hebebrand J. Towards a comprehensive assessment of school absenteeism: development and initial validation of the inventory of school attendance problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 28:399–414. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1204-2

13. Wainer H, Lewis C. Toward a psychometrics for testlets. J Educ Meas. (1990) 27:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.1990.tb00730.x

14. De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, et al. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol Bull. (2015) 141(4):858. doi: 10.1037/a0038498

15. Melvin G, Heyne D, Gray KM, Hastings RP, Totsika V, Tonge B, et al. The kids and teens at school framework: the application of an inclusive nested framework to understand school absenteeism and school attendance problems. Front Educ. (2019) 4:61. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00061

16. Gray L, Hill V, Pellicano E. “He’s shouting so loud but nobody’s hearing him”: a multi-informant study of autistic pupils’ experiences of school non-attendance and exclusion. Autism Dev Lang Impairments. (2023) 8:23969415231207816. doi: 10.1177/23969415231207816

17. Knollmann M, Sicking A, Hebebrand J, Reissner V. The school refusal assessment scale: psychometric properties and validation of a modified German version. Z Kinder JugendpsychiatrPsychother. (2017) 45:265–80. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000415

18. Döpfner M, Schmeck K, Berner W, Lehmkuhl G, Poustka F. Reliability and factorial validity of the child behavior checklist–an analysis of a clinical and field sample. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. (1994) 22(3):189–205.

19. Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Model. (2009) 16:397–438. doi: 10.1080/10705510903008204

20. Marsh HW, Morin AJ, Parker PD, Kaur G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: an integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2014) 10(1):85–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700

21. Berlinski S, Busso M, Dinkelman T, Martínez C. Reducing parent-school information gaps and improving education outcomes: evidence from high-frequency text messages. J Hum Resour. (2022) 60:1121–11992R2. doi: 10.3368/jhr.1121-11992R2

22. Klein M, Sosu EM, Dare S. Mapping inequalities in school attendance: the relationship between dimensions of socioeconomic status and forms of school absence. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 118:105432. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105432

23. De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychol Assess. (2004) 16(3):330–4. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.330

24. Niemi S, Lagerström M, Alanko K. School attendance problems in adolescent with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front. Psychol. (2022) 13:1017619. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1017619

25. Laine C. Psychometric Properties of the Finnish Version of the Inventory of School Attendance Problems (2023). Available online at: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe20231026141596 (Accessed January 15, 2025).

Keywords: school absenteeism, school refusal, truancy, assessment, questionnaire

Citation: Knollmann M and Reissner V (2025) Validation of the parent version of the inventory of school attendance problems (ISAP-P). Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 4:1543527. doi: 10.3389/frcha.2025.1543527

Received: 11 December 2024; Accepted: 12 February 2025;

Published: 25 February 2025.

Edited by:

Carolina Gonzálvez, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Tara Ćirić, Maynooth University, IrelandMariola Giménez-Miralles, Valencian International University, Spain

Copyright: © 2025 Knollmann and Reissner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Knollmann, bWFydGluLmtub2xsbWFubjJAbHZyLmRl

Martin Knollmann

Martin Knollmann Volker Reissner

Volker Reissner