- 1General Education Department, Anhui Xinhua University, Hefei, China

- 2Department of Mathematics, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan

- 3Mathematics Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Natural Sciences and Humanities, University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore(RCET), Lahore, Pakistan

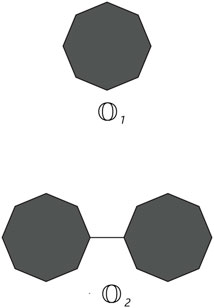

Cyclooctane is classified as a cycloalkane, characterized by the chemical formula C8H16. It consists of a closed ring structure composed of eight carbon atoms and sixteen hydrogen atoms. A cyclooctane chain typically refers to a series of cyclooctane molecules linked together. Cyclooctane and its derivatives find various applications in chemistry, materials science, and industry. Topological indices are numerical values associated with the molecular graph of a chemical compound, predicting certain physical or chemical properties. In this study, we calculated the expected values of degree-based and neighborhood degree-based topological descriptors for random cyclooctane chains. A comparison of these topological indices’ expected values is presented at the end.

1 Introduction

Cyclooctane itself is a cyclic molecule, forming a stable ring structure with eight carbon atoms and saturated with hydrogen atoms. One way to modify cyclooctane is by substituting some of its hydrogen atoms with other functional groups, leading to various derivatives with different properties and reactivities. Substituted cyclooctane derivatives can serve as essential building blocks in organic synthesis.

The unique structure and strain of cyclooctane can influence the reactions it undergoes, potentially leading to interesting transformations. Cyclooctane rings can be part of larger molecules, where their strain energy might play a role in the overall reactivity and stability of the molecule. The strain energy in cyclooctane rings, attributed to their angle strain, can make them more reactive in certain reactions, possibly resulting in unexpected products.

Cyclooctane and its derivatives are intriguing subjects for computational chemistry studies, aiding researchers in understanding their structures, energies, and reactivities (Bharadwaj, 2000; Salamci et al., 2006; Alamdari et al., 2008; Ali et al., 2012; Banu et al., 2015). These derivatives find applications in combustion kinetics, drug synthesis, organic synthesis, and more. For instance, cyclooctane-1,2,5,6-tetrol is utilized in the osmium-catalyzed bis-dihydroxylation of 1,5-cyclooctadiene (Salamci et al., 2006). Alamdari (Alamdari et al., 2008), conducted a study on the synthesis of some cyclooctane-based quinoxalines and pyrazines.

The molecular structures, specifically the graphs depicting carbon atoms, in cyclooctanes form cyclooctane systems (also referred to as octagonal systems (Brunvoll et al., 1997)). In these systems, each inner face is enclosed by a regular octagon, and any two octagons are linked by an edge. Let G be a graph with a vertex set and an edge set denoted by V and E. A vertex v is called the neighbor of vertex w if there is an edge between them (or vw ∈ E). Let N(v) denote the set of neighbors of v. The degree of vertex v is the number of edges incident to it and is denoted by d(v). We use the notation δ(v) to denote the neighborhood degree of a vertex v and is defined as the sum of the degree of the vertices that are adjacent to v, i. e., δ(v) = ∑u∈N(v)d(u). For basic definitions related to graph theory, see (West, 2001).

Topological indices are numerical descriptors that provide information about the connectivity and structure of molecules. Up until now, many topological indices have been proposed by different researchers with applications in chemistry. Among these topological indices, the ones most studied are those based on the degree of vertices in a graph. Milan Randic introduced the first degree-based topological index known as the branching index (Randic, 1975). Randic noted that this index is well-suited for assessing the degree of branching within the carbon atom skelton of saturated hydrocarbons. For a graph G, the Randic index is the sum of

The Randic index shows strong correlations with various physico-chemical properties of alkanes, including but not limited to boiling points, enthalpies of formation, chromatographic retention periods, surface areas, and parameters in the Antoine equation for vapor pressure (Kier et al., 1975).

The second Gourava index was proposed by Kulli (Kulli, 2017), in 2017 and is defined as

Recently, Mondal et al. (Das and Trinajstic, 2010; Imran et al., 2017; Ali et al., 2019), proposed some topological indices based on neighborhood degree. The modified neighborhood forgotten index of a graph G is denoted by

The second modified neighborhood Zagreb index of a graph G is defined as

It was observed that these two topological descriptors show a very good correlation with two physical properties, namely, the acentric factor and the entropy of the octane isomers. Therefore, these topological descriptors are of chemical importance. In, Mondal et al. proposed a few more topological descriptors based on neighborhood degree. He named these topological descriptors the third NDe index and the fourth NDe index. These topological indices are defined as

Different researchers have studied the expected values of random molecular structures in the recent past. Raza et al. (Raza et al., 2023a), conducted calculations for the expected values of sum-connectivity, harmonic, Sombor, and Zagreb indices in cyclooctane chains. In the work presented in (Raza, 2022), expected values for the harmonic and second Zagreb indices were determined for random spiro chains and polyphenyl. Additionally, Raza et al. (Raza et al., 2023b), computed the expected value of the first Zagreb connection index in random cyclooctane chains, random polyphenyl chains, and random chain networks. Explicit formulas for the expected values of certain degree-based topological descriptors of random phenylene chains were provided by Hui et al. (Hui et al., 2023). Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2018), discussed the topological indices of generalized bridge molecular graphs, while in separate works (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023), they computed the topological indices of some supramolecular chains using graph invariants. For more details on this topic of research, readers can see the following papers (Mondal et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020; Mondal et al., 2021; Raza, 2021).

The main aim of this work is to find the expected values of the Randic index, the second Gourava index, the modified neighborhood forgotten index, the third degree neighborhood index, and the fourth degree neighborhood index of the random cyclooctane chain. Moreover, we give a comparison between the expected values of these topological indices.

2 Expected values of topological descriptors for random cyclooctane chains

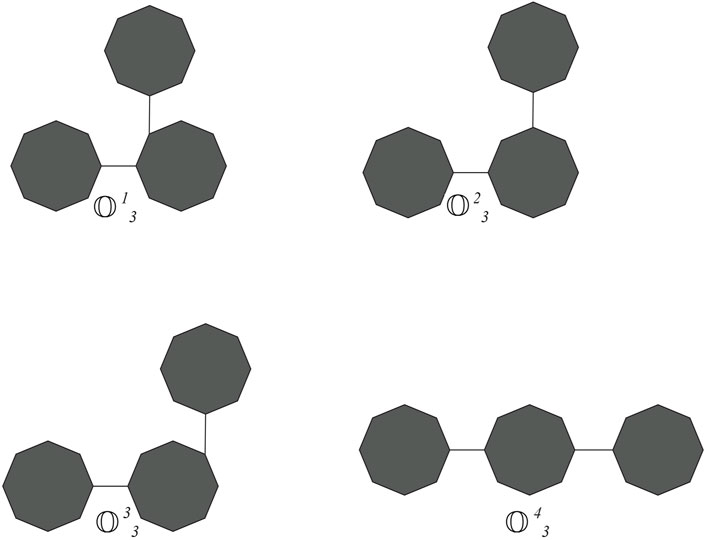

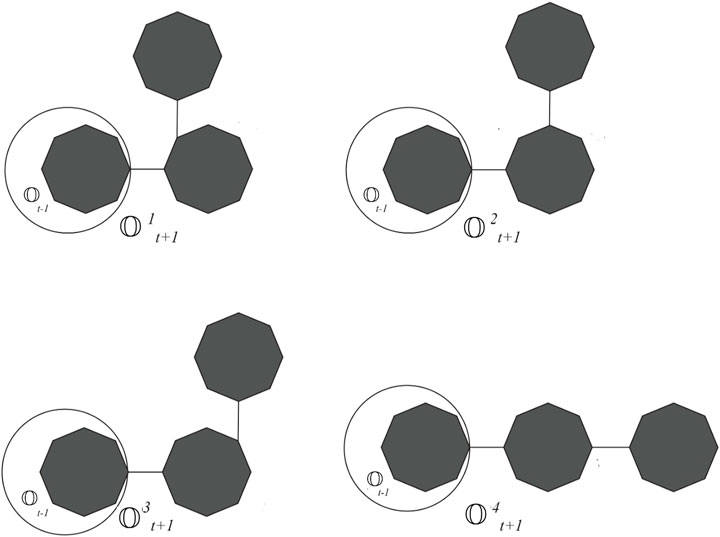

Cyclooctane is a cyclic hydrocarbon with eight carbon atoms arranged in a ring. While it does not form chains itself, neighboring cyclooctane molecules can interact through intermolecular forces. Understanding these interactions is crucial for studying the physical properties and behavior of cyclooctane and similar cycloalkanes. Cyclooctane graphs are examples of cyclic graphs, which are graphs containing a single cycle as their main structural component. A random cyclooctane chain with a length of t is obtained by connecting t octagons in a linear arrangement, where any two consecutive octagons are randomly joined by an edge between vertices. We use the notation

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

From the graph of the cyclooctane chain, it is easy to see that there are only (2,2), (2,3), and (3,3) types of edges. Let xij denote the number of edges of

Since

Theorem 2.1. Let

Proof. Let t = 2, then

A) If

B) If

C) If

D) If

Now, we have

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (7), we obtain

Theorem 2.2. Let

Proof. Let t = 2, then E2 = 366, which is indeed true. For t ≥ 3, there are four possibilities

A) If

B) If

C) If

D) If

Thus, we obtain

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (8), we obtain

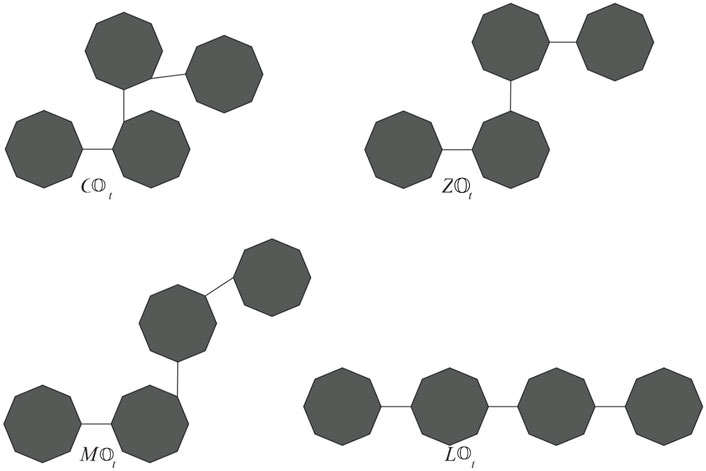

If the probability is invariable to the step parameter and constant, then this process is called a zeroth-order Markov process. We obtain some special classes of cyclooctane chains if we take one of the values of p1,p2, p3, and p4 as one. Let

Corollary 2.3. Let t ≥ 2, then

1. •

•

•

•

2. •

•

•

•

Next, we compute the expected values of topological indices depending on neighborhood degree. For this, we need to find the partition of the edge set of

Theorem 2.4. Let

Proof. For t = 3, we have

A) If

B) If

C) If

d) If

Thus, we obtain

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (13), we obtain

Theorem 2.5. Let

Proof. For t = 3, we have

A) If

B) If

C) If

D) If

Thus, we obtain

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (14), we obtain

Theorem 2.6. Let

Proof. For t = 3, we have

A) If

B) If

C) If

D) If

Thus, we obtain

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (15), we obtain

Theorem 2.7. Let

Proof. For t = 3, we have

A) If

B) If

C) If

D) If

Thus, we obtain

By employing the operator E on both sides and considering the fact that

Finally, solving the recurrence relation (16), we obtain

Corollary 2.8. For t ≥ 3, we have

1. •

•

•

•

2. •

•

•

•

3. •

•

•

•

4. •

•

•

•

3 A comparison between the expected values of topological indices for random cyclooctane chains

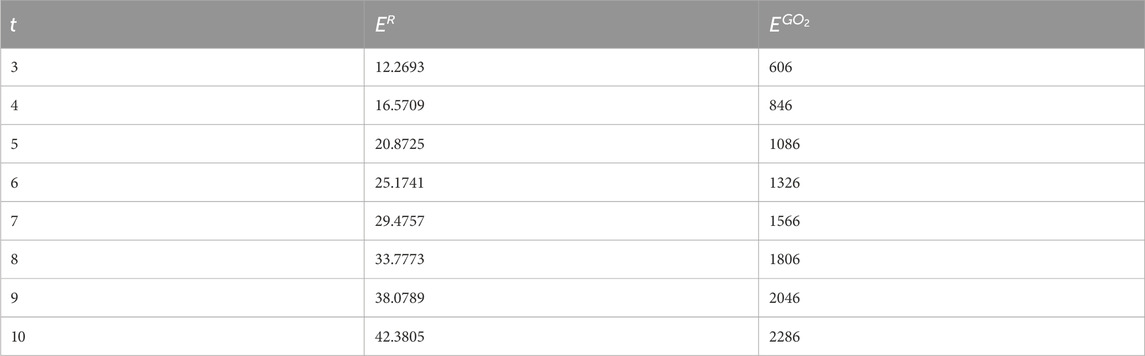

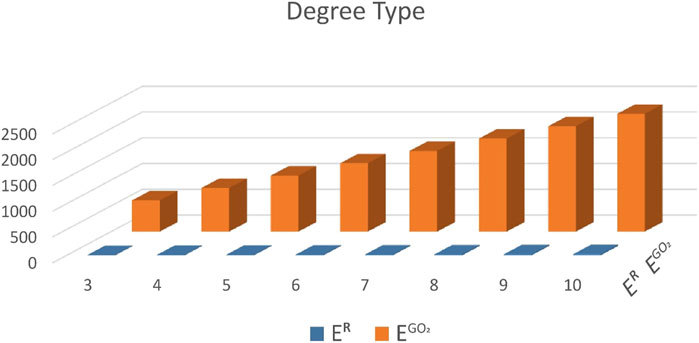

In this section, we give a comparison between the expected values of the considered topological indices for Random Cyclooctane Chains. In Table 1, we have calculated the expected values of the forgotten index and the second Gourava index of random cyclooctane chains for t = 3, 4, … , 10. The plot of the expected values of these topological indices for different values of t is depicted in Figure 5. Observe that the expected values for the forgotten index are always less than the expected value of the second Gourava index for all t ≥ 3. Now, we give an explicit proof of the fact that for any t ≥ 3 the expected value of second Gourava index is always greater than the expected value of the forgotten index in random cyclooctane chains.

Theorem 3.1. Let t ≥ 3, then

Proof. For t = 3, the result follows immediately. By applying Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we get

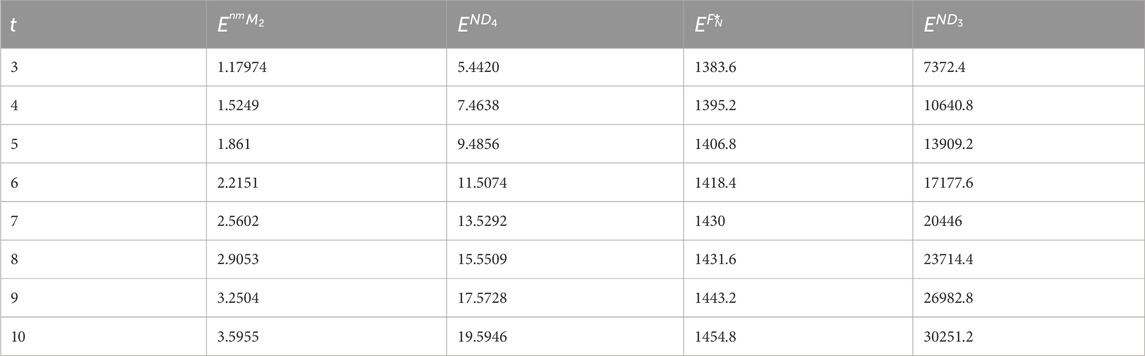

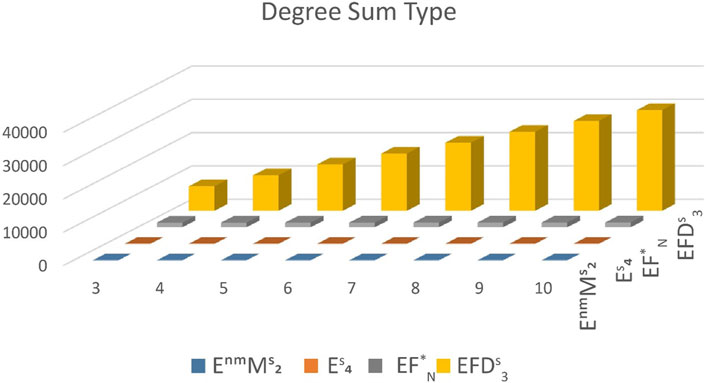

Next, we give a comparison between the expected values of the topological indices based on the neighborhood degree for cyclooctane chains. The expected values of the modified neighborhood Forgotten index, the modified neighborhood second Zagreb index, the third neighborhood index, and the fourth neighborhood index are calculated and depicted in Table 2 for t = 3, 4, … , 10. A 2D plot of these values is shown in Figure 6. Observe that

Theorem 3.2. Let t ≥ 3, then

Proof. For t = 3, the result follows immediately. By applying Theorems 2.7 and 2.5, we get

Theorem 3.3. Let t ≥ 3, then

Proof. For t = 3, the result follows immediately. By applying Theorems 2.7 and 2.4, we get

Theorem 3.4. For t ≥ 3, we have

Proof. For t = 3, the result follows immediately. So, we get

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we have studied the behaviour of cyclooctane chains and calculated the expected values of the neighbourhood sum of some topological indices, which are the neighbourhood forgotten index, general Randić index, modified second Zagreb index, and third, fourth and fifth (NDe) indices of cyclooctane chains. It has been observed that the neighbourhood third (NDe) index has highest value and neighbourhood modified second Zagreb descriptor has the smallest value. In addition, the expected values of cyclooctane chains in some special cases have been computed. The results may be helpful in studying various physical/chemical properties of cyclooctane chains.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LJ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing. SY: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–original draft. SF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–original draft. FT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing. AA: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research project is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province Higher School (No. 2022AH051864, KJ2021A1154) and Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R401), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alamdari, M. H., Helliwell, M., Baradarani, M. M., and Joule, J. A. (2008). Synthesis of some cyclooctane-based pyrazines and quinoxalines. Ieice Tech. Rep. Electron Devices 2008 (14), 166–179. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0009.e17

Ali, A., Zhong, L., and Gutman, I. (2019). Harmonic index and its generalizations: extremal results and bounds. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 81, 249–311.

Ali, K. A., Hosni, H. M., Ragab, E. A., and El-Moez, S. I. A. (2012). Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of some new cyclooctanones and cyclooctane-based heterocycles. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 345 (3), 231–239. doi:10.1002/ardp.201100186

Banu, I., Manta, C. M., Bercaru, G., and Bozga, G. (2015). Combustion kinetics of cyclooctane and its binary mixture with o-xylene over a Pt/γ -alumina catalyst. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 102, 399–406. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2015.07.012

Bharadwaj, R. K. (2000). Conformational properties of cyclooctane: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Molec Phys. 98 (4), 211–218. doi:10.1080/002689700162630

Brunvoll, J., Cyvin, S. J., and Cyvin, B. N. (1997). Enumeration of tree-like octagonal systems. J. Math. Chem. 21 (2), 193–196. doi:10.1023/a:1019122419384

Das, K. C., and Trinajstic, N. (2010). Comparison between first geometric-arithmetic index and atom-bond connectivity index. Chem. Phys. Lett. 497, 149–151. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2010.07.097

Hui, Z.-hao, Yousaf, S., Aslam, A., and Kanwal, S. (2023). On expected values of some degree based topological descriptors of random Phenylene chains. Mol. Phys. 121, 16. doi:10.1080/00268976.2023.2225648

Imran, A. S., Raza, M., and Bounds, Z. (2017). Bounds for the general sum-connectivity index of composite graphs. J. Inequalities Appl. 2017 (2017), 76. doi:10.1186/s13660-017-1350-y

Kier, L. B., Hall, L. H., Murray, W. J., Randi, M., and Molecular, C. I. (1975). Molecular connectivity I: relationship to nonspecific local anesthesia. J. Pharm. Sci. 64 (Issue 12), 1971–1974. doi:10.1002/jps.2600641214

Kulli, V. R. (2017). The Gourava indices and coindices of graphs. Ann. Pure Appl. Math. 14 (1), 33–38. doi:10.22457/apam.v14n1a4

Mondal, S., De, N., and Pal, A. (2019). On some general neighborhood degree based topological indices. Int. J. Appl. Math. 32 (6), 1037. doi:10.12732/ijam.v32i6.10

Mondal, S., Imran, M., De, N., and Pal, A. (2021). Neighborhood M-polynomial of titanium compounds. Arabian J. Chem. 14 (8), 103244. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103244

Randic, M. (1975). Characterization of molecular branching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 6609–6615. doi:10.1021/ja00856a001

Raza, Z. (2021). The expected values of some indices in random phenylene chains. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136 (1), 91–15. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01082-y

Raza, Z. (2022). The harmonic and second Zagreb indices in random polyphenyl and spiro chains. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42, 671–680. doi:10.1080/10406638.2020.1749089

Raza, Z., Akhter, S., and Shang, Y. (2023b). Expected value of first Zagreb connection index in random cyclooctatetraene chain, random polyphenyls chain, and random chain network. Front. Chem. 10, 1067874. doi:10.3389/fchem.2022.1067874

Raza, Z., Arockiaraj, M., Bataineh, M. S., and Maaran, A. (2023a). Cyclooctane chains: mathematical expected values based on atom degree and sum-degree of Zagreb, harmonic, sum-connectivity, and Sombor descriptors. Eur. Phys. J. Special Top., 1–10. doi:10.1140/epjs/s11734-023-00809-5

Salamci, E., Ustabas, R., Coruh, U., Yavuz, M., and Vázquez-López, E. M. (2006). Cyclooctane-1,2,5,6-tetrayl tetraacetate. Acta Cryst. E (62), o2401–o2402. doi:10.1107/s1600536806018204

Xu, P., Azeem, M., Izhar, M. M., Shah, S. M., Binyamin, M. A., and Aslam, A. (2020). On topological descriptors of certain metal-organic frameworks. J. Chem. 2020, 1–12. doi:10.1155/2020/8819008

Zhang, X., Kanwal, M. T. A., Azeem, M., Jamil, M. K., and Mukhtar, M. (2022). Finite vertex-based resolvability of supramolecular chain in dialkyltin. Main. Group Metal. Chem. 45 (1), 255–264. doi:10.1515/mgmc-2022-0027

Zhang, X., Saleem, U., Waheed, M., Jamil, M. K., and Zeeshan, M. (2023). Comparative study of five topological invariants of supramolecular chain of different complexes of N-salicylidene-L-valine. Math. Biosci. Eng. 20 (7), 11528–11544. doi:10.3934/mbe.2023511

Keywords: chemical graph theory, topological indices, cyclooctane chains, expected values, Randic index

Citation: Jing L, Yousaf S, Farhad S, Tchier F and Aslam A (2024) Analyzing the expected values of neighborhood degree-based topological indices in random cyclooctane chains. Front. Chem. 12:1388097. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1388097

Received: 19 February 2024; Accepted: 25 March 2024;

Published: 26 April 2024.

Edited by:

Santanab Giri, Haldia Institute of Technology, IndiaReviewed by:

Savari Prabhu, Rajalakshmi Engineering College, IndiaJoseph Clement, VIT University, India

Copyright © 2024 Jing, Yousaf, Farhad, Tchier and Aslam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adnan Aslam, YWRuYW5hc2xhbTE1QHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Shamaila Yousaf, c2h1bWFpbGEueW91c2FmQHVvZy5lZHUucGs=

Liang Jing1

Liang Jing1 Shamaila Yousaf

Shamaila Yousaf Fairouz Tchier

Fairouz Tchier Adnan Aslam

Adnan Aslam