94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 21 April 2023

Sec. Electrochemistry

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1169896

This article is part of the Research Topic Interfacial Chemistry in Solid-State Lithium-Ion and Lithium Metal Batteries and Beyond View all 4 articles

Li+ conduction in all-solid-state lithium batteries is limited compared with that in lithium-ion batteries based on liquid electrolytes because of the lack of an infiltrative network for Li+ transportation. Especially for the cathode, the practically available capacity is constrained due to the limited Li+ diffusivity. In this study, all-solid-state thin-film lithium batteries based on LiCoO2 thin films with varying thicknesses were fabricated and tested. To guide the cathode material development and cell design of all-solid-state lithium batteries, a one-dimensional model was utilized to explore the characteristic size for a cathode with varying Li+ diffusivity that would not constrain the available capacity. The results indicated that the available capacity of cathode materials was only 65.6% of the expected value when the area capacity was as high as 1.2 mAh/cm2. The uneven Li distribution in cathode thin films owing to the restricted Li+ diffusivity was revealed. The characteristic size for a cathode with varying Li+ diffusivity that would not constrain the available capacity was explored to guide the cathode material development and cell design of all-solid-state lithium batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries have been widely applied in consumer electronics, electric vehicles, and smart grids (Hannan et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Zubi et al., 2018). However, the flammable liquid electrolytes induce frightening safety problems (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018; Duan et al., 2020). In addition, the lithium dendrite growth in liquid electrolytes impedes the use of lithium metal anodes and restricts lithium-based batteries to low energy densities (Liu and Lu, 2017; Kong et al., 2018; Wang T et al., 2020). All-solid-state lithium batteries (ASSLBs), which employ solid electrolytes and metallic lithium anodes, hold great promise for developing the next generation of energy storage technologies with high energy density and safety (Manthiram et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018; Randau et al., 2020).

In the past decades, the R&D on solid electrolyte technologies has made considerable strides in the aspects of materials, process, equipment, and compatibility with lithium metal anodes (Xia et al., 2019; Miao et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Guan et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021; Mou et al., 2021; Song et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2023a). Meanwhile, the cathode has been the major bottleneck for achieving ASSLBs with high energy densities (Chen et al., 2017; Judez et al., 2018; Ma, 2018). The Li+ conduction in the cathode of ASSLBs is limited due to the lack of an infiltrative network for Li+ transportation, compared with the lithium-ion batteries based on liquid electrolytes. The capacity utilization ratio of the cathode in ASSLBs, which is the ratio of practically available capacity to the theoretical expectation, decreases as the particle size and/or thickness of the cathode increases. Although the Li+ diffusivity of cathode materials could be improved via element doping and surface coating (Mou et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2023b; Liu et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020), it is necessary to determine the characteristic size for cathode materials with different Li+ diffusivities that would not impair the capacity utilization rate (CU). The determined characteristic sizes would help design the diameter of cathode particles or the thickness of cathode thin films and promote the development of advanced cathode technologies.

In this work, all-solid-state, thin-film lithium batteries (ASSTFLBs), with the cell structure of LiCoO2-LiPON-Li (Supplementary Figure S1), were chosen as the model system to investigate the characteristic sizes of cathode because the thickness of LiCoO2 thin films can be easily controlled in the experimental and modeling studies. ASSTFLBs based on LiCoO2 thin films with different thicknesses were fabricated and tested. An area capacity of 1.2 mAh/cm2 was achieved when the thickness of LiCoO2 thin film was 25.7 μm. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest value yet reported for ASSTFLBs. However, the CU decreased from 99.2% to 65.6% as the thickness of LiCoO2 thin films increased from 1.21 to 25.7 μm. To analyze the bottleneck factors that affect the CU, a one-dimensional (1D) model of ASSTFLBs was established. The simulations showed that the ASSTFLBs with thicker cathodes possess higher solid-phase lithium concentration (SPLC) after Li extraction, and the uneven distribution of the SPLC also intensifies as the LiCoO2 thickness increases. Additionally, the increased Li+ diffusivity effectively reduces the SPLC in thick LiCoO2 thin films after Li extraction. Thus, the constrained CU should be mainly attributed to the limited Li+ conduction in the cathode. Finally, the quantitative relationship between the CU of the cathode thin film and its thickness is calculated for cathodes with an assumed Li+ diffusivity of 1 × 10−15, 10−14, and 10−13 m2/s, respectively.

ASSTFLBs with the structure of (Ti-Pt)-LiCoO2-LiPON-Li-(Cu-Pt) were fabricated on glass substrates via physical vapor depositions analogous to the method reported in Donders et al. (2013) and Song et al. (2010) (Figure 1). First, a metallic titanium (Ti) thin film with a thickness of 20 nm was deposited on a glass substrate via DC sputtering, followed by a metallic platinum (Pt) thin film with a thickness of 100 nm. The deposited double-layered thin film was then annealed at 400 °C for 30 min. Afterward, the temperature of the annealing chamber was controlled to decrease to room temperature linearly within 4 h. Second, a LiCoO2 thin film was deposited on the Ti-Pt current collector (CC) via sputtering supplied by RF and DC hybrid power. By controlling the sputtering time, LiCoO2 thin films with thicknesses of 1.21, 2.56, 10.17, and 25.70 μm were obtained. The samples were heated to 500 °C with a ramp rate of 300 °C/h and annealed at 500 °C for 900 min. Then, the samples were linearly cooled to room temperature within 7 h. Third, a ∼2-μm thin film of LiPON electrolyte was sputter-deposited on LiCoO2 using the RF and DC hybrid power supply. Fourth, 20 nm of copper (Cu), followed by 100 nm of platinum (Pt), was sputter-deposited using a DC power supply to fabricate the Cu-Pt CC for the Li metal anode. Fifth, 2 μm of lithium metal was deposited using an evaporator in a dry room with a dew point of −50 °C. Sixth, UV glue was applied to the ASSTFBs before they were covered with mica sheets. The packaged cells were cured for 5 min under a UV lamp in the dry room. The footprint of the fabricated ASSTFLBs is 1.2 × 1.2 cm2.

The thickness of LiCoO2 thin films was determined using cross-sectional images obtained by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300) at 10 kV. The cycling performance tests of the ASSTFLBs were performed between 2.7 and 4.2 V using vs. Li+/Li with varied charge–discharge rates at room temperature by the battery test equipment (NEWARE CT-3008). According to the theoretical specific capacity of LiCoO2 (149 mAh/g for the cutoff voltage from 2.7 to 4.2 vs. Li+/Li), ASSTFLBs with a cathode of 1.21, 2.56, and 10.17 μm were first cycled at a low rate of 0.1C for three laps, and then cycled at 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5C for one lap, and finally charged and discharged at 10 C. The ASSTFLBs with the 25.70-μm cathodes were tested at a rate of 0.05C for charge and discharge cycles. The expected capacities for fabricated ASSTFLBs with cathodes of 1.21, 2.56, 10.17, and 25.70 μm LiCoO2 are 0.08, 0.18, 0.69, and 1.18 mAh/cm2, respectively. The CU was determined by dividing the measured or calculated capacities of the LiCoO2 cathode by the theoretically expected values. The theoretical capacities of experimental ASSTFLBs are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

A 1D model of ASSTFLBs with a 2-μm lithium metal anode, a 2-μm LiPON electrolyte, and a LiCoO2 cathode with different thicknesses (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μm) was constructed using COMSOL Multiphysics software (Ramadesigan et al., 2012; Kazemi et al., 2019; Geng et al., 2021). The key parameters and their values in the presented model are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The Li+ diffusivity of the LiCoO2 thin film was assumed to be 1 × 10−15 (D15), 1 × 10−14 (D14), and 1 × 10−13 m2/s (D13), based on the progress of cathode material research (Wang X et al., 2020; Mou et al., 2021). The charge–discharge curves and SPLC of LiCoO2 in the modeled ASSTFLBs were calculated.

The electrode reaction is described by the Butler–Volmer equation:

where ia is the anodic current, ic is the cathodic current, F is the Faraday constant, k is the reaction rate constant, C0 is the concentration of the species, e is the natural constant, α is the charge transfer coefficient of the reaction, R is the molar gas constant, T is the temperature, and η is overpotential (Danilov et al., 2011; Raijmakers et al., 2020).

The mass transfer process in a solid is described by the Nernst–Planck equation:

where Di is the diffusion coefficient (m2/s), ∇ci is the ion concentration gradient (mol/cm3), Zi is the charge of substance, um,i is the mobility (s.mol/kg), ∇∅ represents the potential gradient, and u represents the velocity vector (m/s) (Doyle et al., 1993; Fuller et al., 1994).

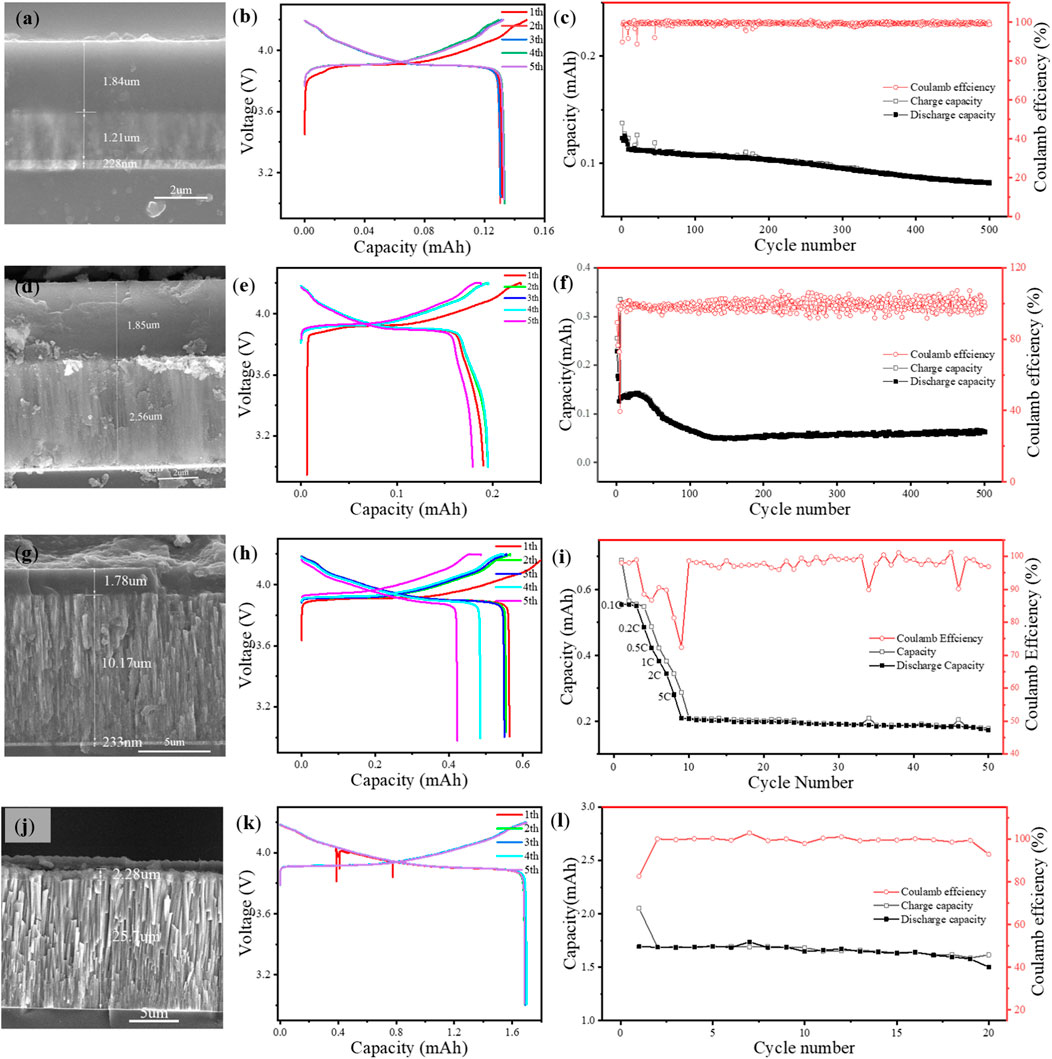

The charge–discharge cycling performance of the ASSTFLBs with different cathode thicknesses was experimentally studied (Figure 2). The simulated ASSTFLBs were charged and discharged at 0.1 mA. When the LiCoO2 thin film is 1.21 μm (Figure 2A), the initial capacity of the ASSTFLBs is 0.12 mAh (Figure 2B) and the corresponding CU is 99.2%. The reversible capacity decreased considerably after 200 cycles, but the Coulombic efficiency remained at a high level of 98.82% at the 500th cycle (Figure 2C). As the thicknesses of the LiCoO2 thin films were increased to 2.56 and 10.17 μm (Figures 2D, G), the CU associated with the initial capacity (0.19 and 0.56 mAh) decreased to 74.2% and 55.1%, respectively (Figures 2E, H). Although the reversible capacity became steady after the fast ramping at the beginning stage, the Coulombic efficiency fluctuated (Figures 2F, I). This implies the continuous materials decay during charge and discharge. The ASSTFLB with a 25.7-μm LiCoO2 cathode (Figure 2J) cannot be cycled at 10 C due to the limited charge transport kinetics. It performed an initial capacity of 1.69 mAh at 0.05 C, corresponding to a CU of 65.7% (Figure 2K). The Coulombic efficiency at the 20th cycle decreased to 92.92% (Figure 2L). The practically available capacity of ASSTFLBs decreased as the thickness of LiCoO2 thin films increased.

FIGURE 2. Cross-sectional SEM images, charge and discharge curves of first five cycles, and cycling performance of ASSTFLBs with varying thicknesses of LiCoO2 thin film: 1.21 μm (A–C), 2.56 μm (D–F), 10.17 (G–I), and 25.7 μm (J–L).

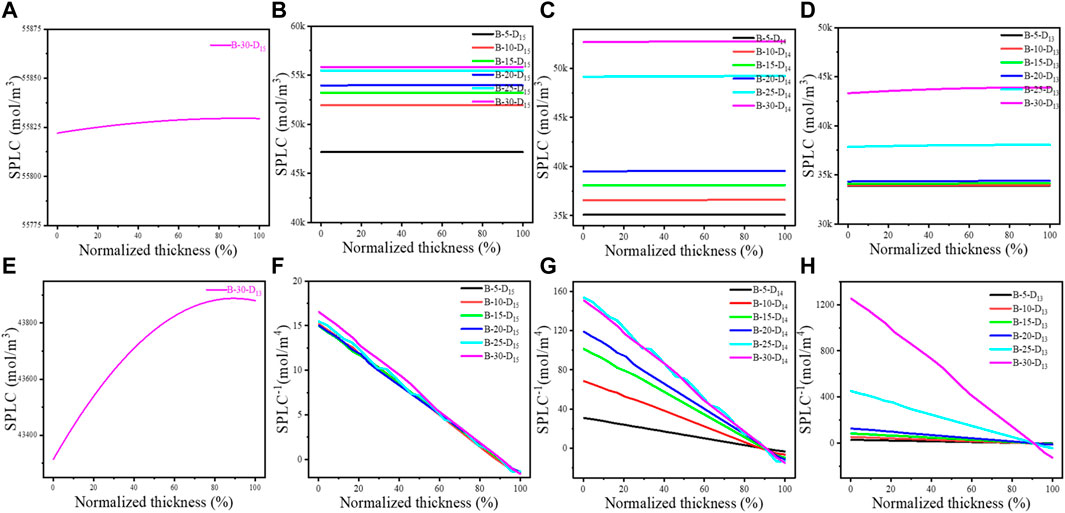

To further understand the effect of Li+ conduction on CU, the SPLCs of the LiCoO2 thin films in ASSTFLBs after charging, which denotes the degree of Li+ extraction from the cathode, were calculated using the presented 1D model. The charging cutoff voltage was set as 4.2 V vs. Li+/Li. The initial point of the abscissa refers to the LiCoO2-LiPON interface, and the endpoint is the LiCoO2-CC interface (Figure 3). Universally, the SPLC at the LiCoO2-LiPON interface is lower than that close to the LiCoO2-CC interface (Figures 3A–E), which indicates that the Li+ is not promptly transported to the LiCoO2-LiPON interface because of the limited Li+ conduction kinetics. For LiCoO2 with a specific Li+ diffusivity, the SPLC increases as its thickness increases (Figures 3B–D). This implies the negative effect of limited Li+ conductibility on CU in the thicker cathode. In addition, the increased Li+ diffusivity would lead to a lower SPLC for the LiCoO2 thin films with the same thickness (Figures 3B–D). Moreover, the calculated SPLCs were lower than 35 k mol/m3 until the thickness of LiCoO2 thin films exceeded 20 μm when Li+ diffusivity was assumed to be 1 × 10−13 m2/s. On the other hand, the SPLC was always higher than 45 k mol/m3 when Li+ diffusivity was assumed to be 1 × 10−15 m2/s. In other words, the enhanced Li+ conductibility would help extract more Li+ from LiCoO2 during the charging process.

FIGURE 3. Calculated SPLC (A–E) and its gradients (F–H) in the LiCoO2 cathodes of the modeled ASSTFLBs. For the denotation of the sample labels, please see Supplementary Table S2.

It is generally believed that the higher Li+ diffusivity would result in a more even distribution of SPLC in the LiCoO2 thin film. However, the distribution of SPLC of the LiCoO2 thin film with the assumed Li+ diffusivity of 1 × 10−15 m2/s was more even than that with the assumed Li+ diffusivity of 1 × 10−13 m2/s when their thicknesses were the same (Figures 3A, E). Furthermore, the LiCoO2 thin films with the Li+ diffusivity of 1 × 10−15 m2/s possessed a reduced SPLC gradient compared with their counterparts (Figures 3F–H). This should be attributed to the retention of Li+ in the LiCoO2 lattice because Li+ diffusivity is very low, which is consistent with the calculated SPLC (Figure 3B) and CU (Table 1). The simulated discharge capacity of the first cycle of the simulated ASSTFLBs can be seen in Supplementary Figure S2. Notably, the LiCoO2 thin films with the assumed Li+ diffusivity of 1 × 10−13 m2/s also perform the considerable gradients of SPLC, especially if the thickness goes over 20 μm. Therefore, it is necessary to pursue a Li+ diffusivity higher than 1 × 10−13 m2/s for the cathode in ASSLBs.

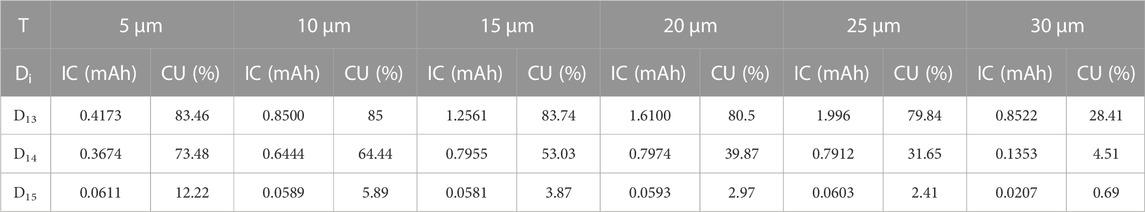

TABLE 1. Calculated initial capacity (IC) and corresponding CU of LiCoO2 thin films in ASSTFLBs with different Li+ diffusivities (Di) and thicknesses (T).

The initial capacities and corresponding CU of ASSTFLBs with different Li+ diffusivities and thicknesses of LiCoO2 thin films were also calculated using the 1D model (Table 1). The charge and discharge current density was set as 0.1 mA, and the cutoff voltage varied from 2.7 to 4.2 V vs. Li+/Li. The trend of CU decreasing as the thickness of the LiCoO2 thin film increased was consistent with the experiment. In addition, the simulations also showed that the improved Li+ diffusivities help achieve higher CU for the thick cathode. The thickness-dependent initial capacity and corresponding CU of LiCoO2 thin films in ASSTFLBs are plotted in Figure 4. When the Li+ diffusivity of the cathode thin film was lower than 1 × 10−14 m2/s, the gain of the capacity of ASSTFLBs due to increased thickness is negligible. If the Li+ diffusivity of the cathode thin film reached 1 × 10−13 m2/s, the capacity linearly increased until its thickness exceeded 20 μm. However, the CU remained lower than 85%, which further demonstrated the necessity to enhance the Li conductibility of the cathode for the development of high-performance ASSLBs.

To summarize, the effects of limited Li+ conduction on the capacity utilization of the cathodes in ASSTFLBs were investigated via experimentation and simulation. One of the highest area capacities of ASSTFLBs (T 298 k, 1.18 mAh/cm2) was achieved via increasing the thickness of cathode thin films, but its capacity utilization ratio was far below expectations. The simulations demonstrated that Li+ in the cathode of ASSTFLBs cannot be readily transported to the cathode–electrolyte interface during charging, even though the Li+ diffusivity was assumed to be one to two orders of magnitude higher than the typical value of pristine LiCoO2. Specifically, the capacity utilization ratio of the cathode in ASSTFLBs was always lower than 85%, while the practically available capacity increased considerably as its thickness increased if the Li+ diffusivity reached 1 × 10−13 m2/s and the thickness did not exceed 20 μm. These results emphasize the demand for enhancing the kinetics of charge transport for the following cathode materials studies. Although it remains a challenge to break the bottleneck of Li+ conduction in the cathodes of ASSLBs, this study provides feasible analysis methods and quantitative guiding data for future efforts.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was supported partly by the National Science Funds of China (Grant No. 21905040) and startup funds from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (Grant No. Y03019023601008001).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2023.1169896/full#supplementary-material

Chen, R. J., Zhang, Y. B., Liu, T., Shen, Y., Li, L.L., Xu, B. Q., et al. (2017). All-solid-state lithium battery with high capacity enabled by a new way of composite cathode design. Solid State Ionics 310, 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2017.07.026

Danilov, D., Niessen, R. A. H., and Notten, P. (2011). Modeling All-solid-state li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem Soc. 158 (3), 215–222. doi:10.1149/1.3521414

Donders, M. E., Arnoldbik, W. M., Knoops, H. C. M., Kessels, W. M. M., and Notten, P. H. L. (2013). Atomic layer deposition of LiCoO2 thin-film electrodes for all-solid-state Li-ion micro-batteries. J. Electrochem Soc. 160 (5), A3066–A3071. doi:10.1149/2.011305jes

Doyle, M., Fuller, T. F., and Newman, J. (1993). Modeling of galvanostatic charge and discharge of the lithium/polymer/insertion cell. J. Electrochem Soc. 140 (6), 1526–1533. doi:10.1149/1.2221597

Duan, J., Tang, X., Dai, H., Yang, Y., Wu, W., Wei, X., et al. (2020). Building safe lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: A review. Electrochem Energy R. 3 (1), 1–42. doi:10.1007/s41918-019-00060-4

Fuller, T. F., Doyle, M., and Newman, J. (1994). Simulation and optimization of the dual lithium ion insertion cell. J. Electrochem Soc. 141 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1149/1.2054684

Gao, Z., Sun, H., Fu, L., Ye, F., Zhang, Y., Luo, W., et al. (2018). Promises, Challenges, and recent progress of inorganic solid-state electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Adv. Mater 30 (17), 1705702–1705727. doi:10.1002/adma.201705702

Geng, Z., Wang, S., Lacey, M. J., Brandell, D., and Thiringer, T. (2021). Bridging physics-based and equivalent circuit models for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 372, 137829. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2021.137829

Guan, M., Huang, K., Mou, S. W., Jiang, C. Z., Pang, Y., Xiang, A., et al. (2021). Superior ionic conduction in LiAlO2 thin-film enabled by triply coordinated nitrogen. AIP Adv. 11 (6), 065310. doi:10.1063/5.0047625

Hannan, M. A., Hoque, M. M., Hussain, A., Yusof, Y., and Ker, P. J. (2018). State-of-the-art and energy management system of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicle applications: Issues and recommendations. Ieee Access 6, 19362–19378. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2817655

Judez, X., Eshetu, G. G., Li, C., Rodriguez-Martinez, L. M., Zhang, H., and Armand, M. (2018). Opportunities for rechargeable solid-state batteries based on Li-intercalation cathodes. Joule 2 (11), 2208–2224. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.09.008

Kazemi, N., Danilov, D. L., Haverkate, L., Dudney, N. J., Unnikrishnan, S., and Notten, P. H. (2019). Modeling of all-solid-state thin-film Li-ion batteries: Accuracy improvement. Solid State Ionics 334, 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2019.02.003

Kong, L., Xing, Y., and Pecht, M. G. (2018). <italic>in-situ</italic> Observations of Lithium Dendrite Growth. Ieee Access 6, 8387–8393. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2805281

Li, M., Lu, J., Chen, Z., and Amine, K. (2018). 30 years of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater 30 (33), 1800561. doi:10.1002/adma.201800561

Liu, G., and Lu, W. (2017). A model of concurrent lithium dendrite growth, SEI growth, SEI penetration and regrowth. J. Electrochem Soc. 164, A1826–A1833. doi:10.1149/2.0381709jes

Liu, Q., Su, X., Lei, D., Qin, Y., Wen, J., Guo, F., et al. (2018). Approaching the capacity limit of lithium cobalt oxide in lithiumion batteries via lanthanum and aluminium doping. Nat. Energy 3 (11), 936–943. doi:10.1038/s41560-018-0180-6

Lu, P., Liu, L., Wang, S., Xu, J., Peng, J., Yan, W., et al. (2021). Superior all-solid-state batteries enabled by a gas-phase-synthesized sulfide electrolyte with ultrahigh moisture stability and ionic conductivity. Adv. Mater 33 (32), 2100921. doi:10.1002/adma.202100921

Ma, Y. (2018). Computer simulation of cathode materials for lithium ion and lithium batteries: A review. Energ Environ. Mater 1 (3), 148–173. doi:10.1002/eem2.12017

Manthiram, A., Yu, X., and Wang, S. (2017). Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater 2 (4), 16103–16133. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2016.103

Miao, X., Wang, H., Sun, R., Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Yin, L. W., et al. (2020). Interface engineering of inorganic solid-state electrolytes for high-performance lithium metal batteries. Energ Environ. Sci. 13 (11), 3780–3822. doi:10.1039/d0ee01435d

Mou, S. W., Huang, K., Guan, M., Ma, X., Chen, J. S., Xiang, Y., et al. (2021). Reduced energy barrier for Li+ diffusion in LiCoO2 via dual doping of Ba and Ga. J. Power Sources 505, 230067–230074. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230067

Peng, X., Huang, K., Song, S. P., Wu, F., Xiang, Y., and Zhang, X. (2020). Garnet-polymer composite electrolytes with high Li+ conductivity and transference number via well-fused grain boundaries in microporous frameworks. ChemElectroChem 7 (11), 2389–2394. doi:10.1002/celc.202000202

Raijmakers, L., Danilov, D., Eichel, R., and Notten, P. (2020). An advanced all-solid-state Li-ion battery model. Electrochimica Acta 330, 135147–135152. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135147

Ramadesigan, V., Northrop, P., Santhanagopalan, S., Braatz, R. D., and Subramanian, V. R. (2012). Modeling and simulation of lithium-ion batteries from a systems engineering perspective. J. Electrochem Soc. 159 (3), 31–45. doi:10.1149/2.018203jes

Randau, S., Weber, D. A., Kötz, O., Koerver, R., Braun, P., Weber, A., et al. (2020). Benchmarking the performance of all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nat. Energy 5 (3), 259–270. doi:10.1038/s41560-020-0565-1

Song, S. P., Peng, X., Huang, K., Zhang, H., Wu, F., Xiang, Y., et al. (2020). Improved cycling stability of LiCoO2 at 4.5 V via surface modification of electrodes with conductive amorphous LLTO thin film. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 110–10. doi:10.1186/s11671-020-03335-8

Song, S. P., Yang, C., Jiang, C. Z., Wu, Y. M., Guo, R., Sun, H., et al. (2022). Increasing ionic conductivity in Li0.33La0.56TiO3 thin-films via optimization of processing atmosphere and temperature. Rare Met. 41, 179–188. doi:10.1007/s12598-021-01782-5

Song, S. W., Choi, H., Park, H. Y., Park, G. B., Lee, K. C., and Lee, H. J. (2010). High rate-induced structural changes in thin-film lithium batteries on flexible substrate. J. Power Sources 195 (24), 8275–8279. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.06.113

Wang, Q., Jiang, L., Yan, Y., and Sun, J. (2018). Progress of enhancing the safety of lithium ion battery from the electrolyte aspect. Nano Energy 55, 93–114. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.10.035

Wang, Q., Ping, P., Zhao, X., Chu, G., Sun, J., and Chen, C. (2012). Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 208 (24), 210–224. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.02.038

Wang, T., Li, Y., Zhang, J., and Yan, K. (2020). Jaumaux, P. Immunizing lithium metal anodes against dendrite growth using protein molecules to achieve high energy batteries. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1–9.

Wang, X., Ding, Y. L., Deng, Y. P., and Chen, Z. (2020). Ni-rich/Co-poor layered cathode for automotive li-ion batteries: Promises and challenges. Adv. Energy Mater 10 (12), 1903864–1903892. doi:10.1002/aenm.201903864

Wei, C., Chen, S., Yu, C., Wang, R., Luo, Q., Chen, S., et al. (2023b). Achieving high-performance Li6. 5Sb0. 5Ge0. 5S5I-based all-solid-state lithium batteries. Appl. Mater. Today 31, 101770–101778. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2023.101770

Wei, C., Yu, C., Wang, R., Peng, L., Chen, S., Miao, X., et al. (2023a). Sb and O dual doping of Chlorine-rich lithium argyrodite to improve air stability and lithium compatibility for all-solid-state batteries. J. Power Sources 559 (559), 232659–232668. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2023.232659

Xia, S., Wu, X., Zhang, Z., Cui, Y., and Liu, W. (2019). Practical Challenges and future perspectives of all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Chem 5, 753–785. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.11.013

Zhu, Y. L., Wu, S., Pan, Y., Zhang, X., Yan, Z., and Xiang, Y. (2020). Reduced energy barrier for Li+ transport across grain boundaries with amorphous domains in LLZO thin films. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15 (1), 153–158. doi:10.1186/s11671-020-03378-x

Keywords: all-solid-state lithium batteries, cathode, capacity, Li+ diffusivity, modeling

Citation: Wang Z, Song S, Jiang C, Wu Y, Xiang Y and Zhang X (2023) Effects of Li+ conduction on the capacity utilization of cathodes in all-solid-state lithium batteries. Front. Chem. 11:1169896. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2023.1169896

Received: 20 February 2023; Accepted: 13 March 2023;

Published: 21 April 2023.

Edited by:

Haisheng Fang, Kunming University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Shan Liu, North China Institute of Science and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Wang, Song, Jiang, Wu, Xiang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongmin Wu, d3V5bTIwMTRAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Yong Xiang, eHlnQHVlc3RjLmVkdS5jbg==; Xiaokun Zhang, enhrQHVlc3RjLmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.