95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 23 January 2023

Sec. Inorganic Chemistry

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1089501

This article is part of the Research Topic Radioiodine Detection and Management View all 8 articles

Waste management for radioiodine is a key issue for the sustainable nuclear fuel cycle. The iodine adsorption behavior on a bed column of a silver-impregnated alumina sorbent (AgA) under conditions designed to match those of the Rokkasho reprocessing facility dissolver off-gas (DOG) system was investigated using different volatilized iodine concentrations. Cross-sectional observations of iodine-bearing AgA grains revealed that iodine was adsorbed as silver iodide and silver iodate, and gradually distributed from the surface to the inside of the AgA. The iodine distribution throughout the AgA beds allowed us to estimate the length of the mass-transfer zone. This suggests that the iodine load fraction in AgA (adsorbed iodine/total impregnated silver) will be averaged to 50% in the expected facility equipment design. This study also describes the waste form durability after disposal. To reproduce the average iodine loading in the waste form, 100%-loaded AgA grains were mixed with an equal amount of commercially available alumina reagents and consolidated through hot isostatic pressing at 175 MPa and 1,325°C for 3 h. The resultant 50%-loaded solid was used for the static leaching test over 4.5 years, where the leached iodine was less than 0.2% under simple reducing conditions. This suggested that the HIPed solid of AgA from Rokkasho DOG showed preferable water resistance for after disposal safety.

Silver-impregnated materials are widely used as radioactive iodine adsorbents in the nuclear industry. The nuclear fuel reprocessing facility in Rokkasho, Japan contains several off-gas treatment systems, including the dissolver off-gas (DOG), vessel off-gas, and melter off-gas, which remove radioiodine. The DOG stream has the highest iodine concentration, where the radioiodine discharged from spent fuel dissolution is removed by the silver-impregnated alumina sorbent (AgA) to prevent radioactive emission to the environment. The total amount of spent AgA and total 129I inventory are estimated to be 137 tons and 5.1 × 1013 Bq, respectively, from 40 years of reprocess operation at 32,000 MTU (Federation of Electric Power Companies (FEPC) and Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA), 2007); The Nuclear Waste Management Organization of Japan (NUMO, 2018). Waste management of spent AgA for disposal deep underground is a key issue, because 129I has an extremely long half-life (1.6 × 107 years) and is mobile in engineered and geologic barrier systems. Thus, additional stabilization treatments for iodine-bearing waste are needed to meet the long-term performance requirements of waste disposal.

Since the 1980s, several waste forms, such as simple iodine compounds, glasses, and iodine-bearing minerals, have been suggested for iodine immobilization (Audubert et al., 1997; Vance and Hartman, 1999; Hyatt et al., 2003; Sakuragi et al., 2008; Stennett et al., 2012; Haruguchi et al., 2013; Jubin and Bruffey, 2014) and were reviewed by Riley et al. (2016). In recent times, iodine immobilization remains a significant concern for reprocessing and subsequent waste management, thus warranting further dedicated research on durable waste form development (Idemitsu and Sakuragi, 2015; Mukunoki et al., 2016; Sakuragi et al., 2016; Yamashita et al., 2016; Coulon et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Vance et al., 2018; Asmussen et al., 2019).

Hot isostatic pressing (HIP) is a promising consolidation treatment for iodine immobilization to produce durable iodine-bearing waste (Fujihara et al., 1999; Vance et al., 2005; Sakuragi et al., 2015; Masuda et al., 2016; Matyas et al., 2016; Maddrell et al., 2019). Direct consolidation of spent AgA is advantageous, as it is a simple process that does not generate secondary waste. This is because alumina, a base material of AgA, can be used as a solidification matrix without iodine desorption from the spent AgA. The waste form characteristics are thus characterized by the properties of spent AgA, such as iodine loading. However, little to no information was found on the actual iodine load fraction (fload) relevant to the DOG system of the Rokkasho reprocessing facility. In previous studies, several simulated waste forms were synthesized using AgA with an iodine loading of 100% (Sakuragi et al., 2015; Masuda et al., 2016).

Gas-phase iodine capture has been studied in silver sorbents using inorganic or organic iodine (Fukasawa et al., 1994; Sakurai et al., 1997; Takeshita and Azegami, 2004; Maddrell et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015; Bruffey et al., 2016). In every case, the adsorption bed length was as small as 100 mm or shorter (Fukasawa et al., 1994; Sakurai et al., 1997; Takeshita and Azegami, 2004; Bruffey et al., 2016), or batch adsorption was performed (Maddrell et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015). The iodine filter columns of the Rokkasho DOG have a bed length of 850 mm. This study investigates the adsorption of stable iodine onto AgA in a scaled-up system under simulated conditions of the Rokkasho DOG stream. Iodine filters are replaced when a breakthrough occurs. Thus, the mass transfer zone (MTZ) of iodine in the bed column provides information on the fload of spent AgA in the DOG. Based on the MTZ results, the targeted load fraction of AgA was reproduced by blending the saturated AgA (100% load) with alumina powder; then, the simulated AgA was consolidated using HIP. A static leach test over 4.5 years was performed under reducing conditions using the HIPed solid.

Silver-impregnated iodine sorbents (AgA) used in the DOG treatment system of the Rokkasho reprocessing facility were obtained. The silver content of the porous AgA beads was over 10% by weight in nitrate form. AgA specifications are listed in Table 1.

Adsorption experiments were performed by passing iodine through the AgA beds. As a preliminary test, small-scale adsorption experiments were performed using three sorbent beds placed in series. The first, second, and third beds were 20 mm deep, had a 54 mm inner diameter, and were separated by 25 mm thick glass wool in the same glass column. Iodine (I2) at 160 ppm was passed through the column beds maintained at 150°C for 6 h. The load fraction, speciation, and distribution of the iodine adsorbed on the sorbents were investigated.

In the next step, adsorption tests were performed using the column system under low and high iodine concentrations and different bed lengths up to 1,200 mm. The scale-up tests using the actual adsorbents better simulated the Rokkasho DOG system in terms of bed length, temperature, and flow rate. Iodine concentrations are assumed as high and low, because the concentration cannot be adjusted exactly to that in the DOG. The HNO3 concentration in the off-gas was not considered in this study because they are recovered before iodine adsorption. Figure 1 shows the apparatus used for column adsorption tests. The carrier nitrogen gas flowed through the system. Iodine was generated in the first thermostatic chamber, composed of two containers containing iodine maintained at 40°C. The iodine concentration was controlled in a second thermostatic chamber kept at 20°C, where iodine was diluted using nitrogen gas supplied from another line. The iodine was flushed through a bypass line until the concentration remained constant. Then, a given concentration of iodine was pre-heated and rectified in the inlet of a column filled with alumina balls and passed through the adsorption bed filled with AgA beads at 150°C. The temperature inside the bed was monitored during the test. The operation times were set taking the iodine concentration into consideration. The column test conditions are summarized in Table 2.

After the adsorption tests, AgA was collected from a predetermined location in the beds. The elemental distribution in the AgA beads was observed using an electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA) (JEOL, EPMA8800RL). After crushing and dissolving, the amounts of Ag and I loaded on AgA were measured using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (Shimadzu, ICPS-800), and NO3− and IO3− were measured using ion chromatography (DIONES, DX-500, ICS-3000).

Based on the results obtained from the iodine adsorption experiments, the simulated 50% iodine-loaded AgA was consolidated using HIP. In the present work, 50%-loaded AgA simulants were prepared by blending α-alumina with saturated AgA (100% iodine loading), obtained by loading non-radioactive iodine onto virgin AgA and passing it through excess I2 at 150°C. The 100%-loaded AgA was crushed into particles of approximately 40 μm before mixing. The α-alumina (Taimicron, TM-DAR) was obtained from Taimei Chemicals Co., Ltd. This alumina powder has a high purity over 99.99%, BET surface area of 14.5 m2/g, diameter of 0.10 μm, and sintered density of 3.96 g/cm3. Two materials were uniformly mixed in an equivalent weight ratio and the mixture was encapsulated in a stainless steel can (50 cm3) and heated at 450°C under high vacuum (<133 × 10−5 Pa) for 2 h to remove volatile components. This thermal treatment before HIP allows all iodine species to change to silver iodide (AgI) and the solid to become denser (Masuda et al., 2016). The HIP treatment was then performed at 1,325°C and 175 MPa for 3 h using an Ar gas-pressurized HIP system (Kobelco, Dr. HIP). The solid porosity was determined using the Archimedes method (Japanese Industrial Standards, 1992).

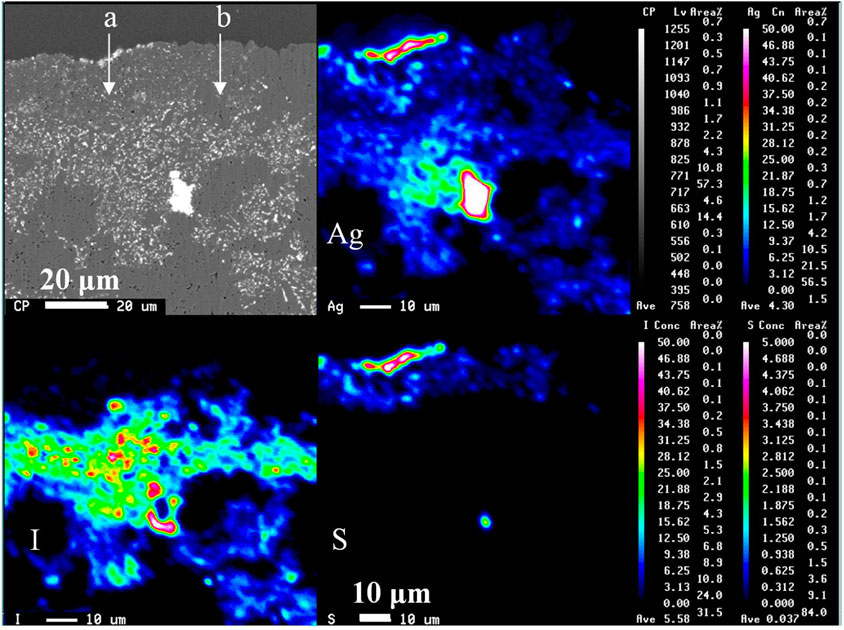

The HIPed solid with 50% iodine loading for the leaching test was cut into 10 mm cubes and washed with a dilute sodium sulfide (Na2S) solution (3 × 10−3 M) under ultrasound for 20 min to remove the AgI exposed on the specimen surface. This procedure was repeated five times, and the samples were rinsed with deionized water. Less than 1% of the total iodine in the solid was lost during the washing procedure. The static leaching test was carried out in 600 ml deionized water (surface-to-volume ratio of 0.01 cm−1) for 1,687 days at room temperature (22°C–23°C). The immersed sample was kept in a glove box purged with N2 gas (oxygen concentration <1 ppm). During the test, the pH and Eh of the solution were checked regularly. A small portion of the 600 ml leaching solution was obtained for each sampling period to analyze the concentrations of the leached elements using ICP-MS (PerkinElmer, ELAN DRC II and Agilent 7,700x). After 1,687 days, the solid was removed, and the cross-section was observed using the EPMA.

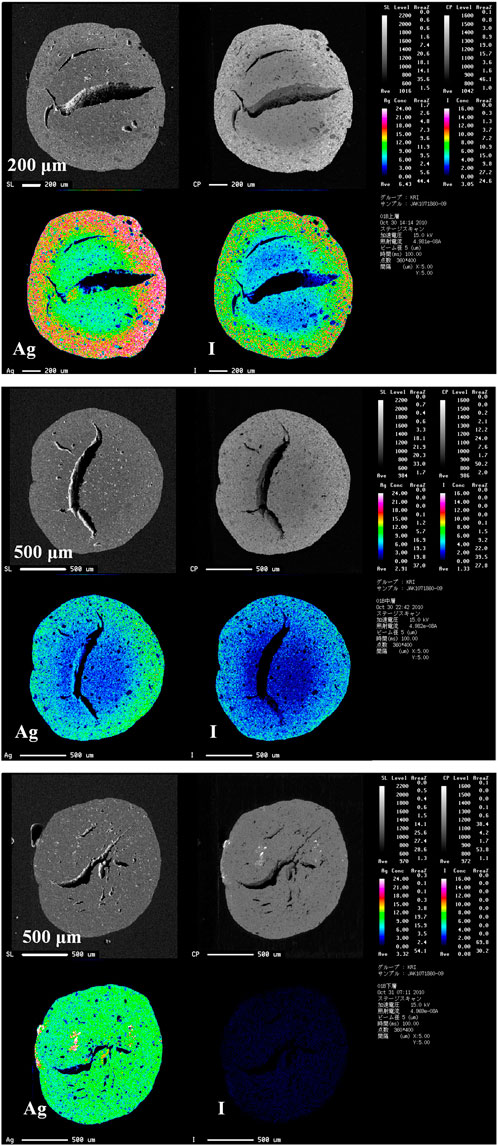

Figure 2 shows the EPMA cross-section images of AgA after iodine loading in the small-scale three-bed adsorption experiment. Large voids could be observed in the AgA. Iodine co-existed with silver and was distributed from the outside to the inside of the AgA, except for the third bed. This suggests that the silver was impregnated heterogeneously in the original AgA, and that the iodine adsorbed onto the silver to form compounds, such as AgI and AgIO3. The presence of AgI and AgIO3 was confirmed through X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of 100%-loaded AgA (Masuda et al., 2016).

FIGURE 2. Electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA) images for AgA cross-section AgA after iodine adsorption in a small-scale adsorption experiment equipped with three bed columns. The top, middle, and bottom images represent iodine-bearing AgA obtained from the first, second, and third beds, respectively. The iodine loadings are summarized in Table 3.

The

where

TABLE 3. Iodine loading on AgA obtained from the small-scale adsorption experiment using three beds.

Figure 3 shows the iodine adsorption behavior onto the AgA bed column in the scale-up experiments to estimate the realistic load fraction of spent AgA in the DOG. The fload decreased rapidly with bed length, but reached the outlet of the column in both short-column tests, suggesting a breakthrough from the 100 mm beds. Owing to the low iodine concentration of 8 ppm, the fload values also decreased to zero at the inlet in a bed length of 300 mm for the 900 mm column. Thus, the MTZ (fload = 0.05–0.95) was not clear for the 900 mm column. In the 1,200 mm column test with 160 ppm iodine shown in Figure 3, the fully loaded fraction decreased from 600 mm to 900 mm, and then fload values decreased to 0.5 at 1,190 mm. Considering the symmetry and the midpoint of 750 mm between 600 mm and 900 mm as the fload value of 0.95, the MTZ length could be estimated at 880 mm. The iodine filter columns of the Rokkasho DOG have a bed length of 850 mm and will be replaced when breakthrough occurs. Thus, the average fload value of the spent AgA was roughly estimated as 50%. The difference between iodine concentrations of 8 and 160 ppm may have been too large. The MTZ data might not be sufficient for detailed verification; however, the present study assumed a 50% loading for subsequent investigations regarding AgA solidification and its leaching behavior.

The porosity of the HIPed solid synthesized using the simulated 50% iodine-loaded AgA was 4.4%. This porosity corresponds to previous data for a 100%-loaded solid (Masuda et al., 2016). The HIP process for iodine-bearing AgA confirmed that fine AgI was retained uniformly in the crystal grain boundaries of the α-alumina (Al2O3) matrices (Sakuragi et al., 2015; Masuda et al., 2016). Figure 4 shows the appearance of 50% solid loading after immersion. The solid surface (left image) was dark gray, because the sample was washed with Na2S solution before immersion, suggesting that silver sulfide (Ag2S) formed on the surface as follows: 2AgI + HS− = Ag2S + 2I− + H+. Inagaki et al. (2007) used XRD to confirm the formation of Ag2S on the surface of AgI particles in contact with Na2S solution. Alteration was limited only to the surface and the light gray area in the cross-section represents pristine α-alumina and slight, fine AgI.

FIGURE 4. Photographs showing 50% solid loading after immersion test. The left represents the solid surface. The right represents the cross-section.

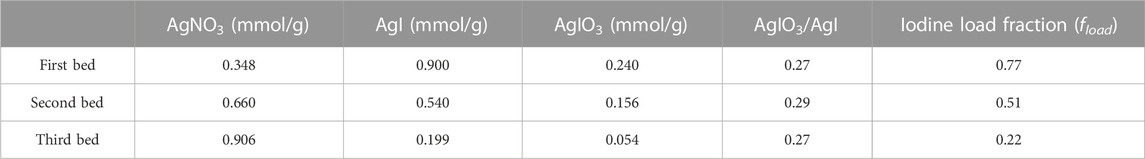

The leaching test results are shown in Figure 5. We obtained the normalized elemental mass loss (NL, g/m2) using the following equation:

where

FIGURE 5. The normalized mass loss (NL) of iodine and aluminum during the static leaching test using 50% solid loading. The dashed line represents the aluminum detection limit.

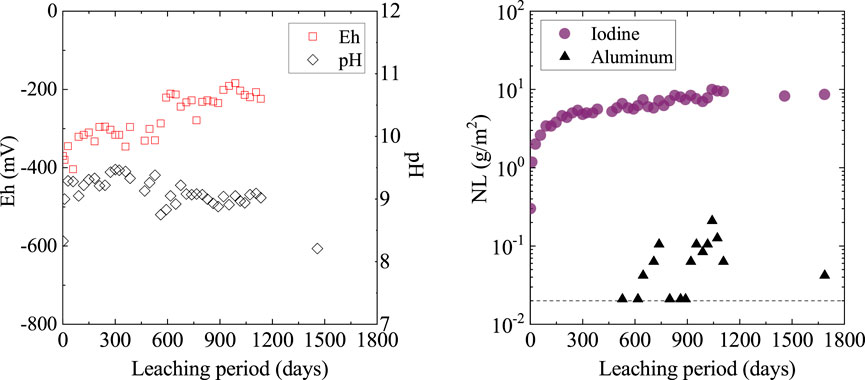

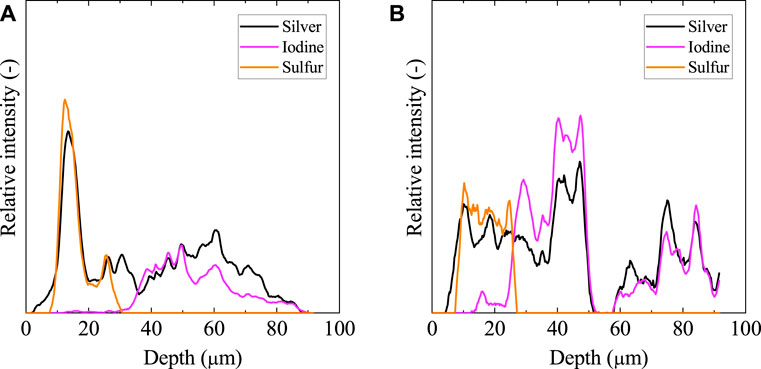

Figure 6 shows the elemental distribution of the solid cross-section after the leaching test using an EPMA. Figure 7 also shows the element distribution via line analysis from the surface to the inside of the solid, obtained from the EPMA results in Figure 6. Silver co-existed with sulfur and iodine at the solid surface and inside, respectively. Sulfur was located only on the solid surface as Ag2S due to surface washing before immersion, as mentioned previously. Iodine was distributed immediately below the surface of the Ag2S layer. Evidently, only a small amount of iodine was released from the solid.

FIGURE 6. EPMA analysis of cross section at 50%-loaded solid after 1,687 days of aqueous immersion. The top of images shows the solid/water interface. The symbols a and b represent the direction of line analysis in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7. Elemental distributions from the surface to the inside for the 50%-loaded solid after immersion obtained in Figure 6. The left (A) and right (B) represent the results for the a and b directions in the EPMA image, respectively.

The above results suggest that the dense 50%-loaded solid showed preferable water resistance under reducing conditions, unless aggressive reducing agents, such as hydrosulfide, were present. The kinetic study of AgI dissolution supports the present results, as iodine release proceeds at an extremely slow rate because of the formation of a protective Ag layer at the AgI surface under reducing conditions with Fe2+ (Inagaki et al., 2008). However, under high hydrosulfide conditions, iodine leaching from HIPed solids is accelerated by a strong silver-sulfur reaction (Sakuragi et al., 2015).

In the present work, realistic 50% iodine loading onto AgA was achieved via iodine adsorption experiments using a 1,200 mm length column under simulated conditions for the DOG system in the Rokkasho reprocessing facility. A simulated 50%-loaded solid was synthesized using HIP, and its durability and iodine immobilization performance were investigated for long-term disposal safety. Over 4.5 years, the leaching test under reducing aqueous conditions showed that leached iodine was less than 0.2% of the iodine in the solid owing to the protective role of the dense Al2O3 matrix and the passive layer on the AgI surface. These results suggested that the HIP solidification for iodine-bearing wastes from the nuclear fuel cycle is promising for the waste management to meet the long-term disposal safety. It will be a future challenge to investigate the detailed leaching process relevant to the microstructure of alumina matrices. The performance of the solid under more severe conditions, such as higher pH conditions, where the alumina matrix dissolves is of interest.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

TS contributed to the conception and design of the study. SY and OK performed some of the experiments, interpreted the data, and performed the data analysis. TS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

This study was carried out as a part of an R&D supporting program titled “Advanced technology development for geological disposal of TRU waste” under contract with the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) (Grant Number: JPJ007597).

SY and OK were employed by the Company Kobe Steel, Ltd.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Asmussen, R. M., Ryan, J. V., Matyas, J., Crum, J. V., Reiser, J. T., Avalos, N., et al. (2019). Investigating the durability of iodine waste forms in dilute conditions. Materials 12, 686–707. doi:10.3390/ma12050686

Audubert, F., Carpena, J., Lacout, J. L., and Tetard, F. (1997). Elaboration of an iodine-bearing apatite iodine diffusion into a Pb3(VO4)2 matrix. Solid State Ion. 95, 113–119. doi:10.1016/s0167-2738(96)00570-x

Bruffey, S. H., Jubin, R. T., and Jordan, J. A. (2016). Capture of elemental and organic iodine from dilute gas streams by silver-exchanged mordenite. Procedia Chem. 21, 293–299. doi:10.1016/j.proche.2016.10.041

Coulon, A., Grandjean, A., Laurencin, D., Jollivet, P., Rossignol, S., and Campayo, L. (2017). Durability testing of an iodate-substituted hydroxyapatite designed for the conditioning of 129I. J. Nucl. Mater. 484, 324–331. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2016.10.047

Federation of Electric Power Companies (FEPC) and Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) (2007). Second progress report on research and development for TRU waste disposal in Japan. Tokai, Ibaraki, Japan: Japan Atomic Energy Agency.

Fujihara, H., Murase, T., Wada, R., Nishimura, T., Imakita, T., Sugimura, Y., et al. (1999). “Fixation of radioactive iodine by hot isostatic pressing,” in Proc. ASME 7th International Conference on Environmental Remediation and Radioactive Waste Management, 26-30 September 1999 (Japan: Nagoya).

Fukasawa, T., Funabashi, K., and Kondo, Y. (1994). Separation technology for radioactive iodine from off-gas streams of nuclear facilities. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 31, 1073–1083. doi:10.1080/18811248.1994.9735261

Haruguchi, Y., Higuchi, S., Obata, M., Sakuragi, T., Takahashi, R., and Owada, H. (2013). A study on iodine release behavior from iodine-immobilizing cement solid. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1518, 85–90. doi:10.1557/opl.2013.68

Hyatt, N. C., Hriljac, J. A., Choudhry, A., Malpass, L., Sheppard, G. P., and Maddrell, E. R. (2003). Zeolite – salt occlusion: A potential route for the immobilisation of iodine-129? Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 807, 359–364. doi:10.1557/proc-807-359

Idemitsu, K., and Sakuragi, T. (2015). Current status of immobilization techniques for geological disposal of radioactive iodine in Japan. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1744, 3–13. doi:10.1557/opl.2015.297

Inagaki, Y., Imamura, T., Idemitsu, K., Arima, T., Kato, O., Asano, H., et al. (2007). Aqueous dissolution of silver iodide and associated iodine release under reducing conditions with sulfide. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 985, 431–436. doi:10.1557/PROC-985-0985-NN12-12

Inagaki, Y., Imamura, T., Idemitsu, K., Arima, T., Kato, O., Nishimura, T., et al. (2008). Aqueous dissolution of silver iodide and associated iodine release under reducing conditions with FeCl2 solution. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 45, 859–866. doi:10.1080/18811248.2008.9711487

Jubin, R. T., and Bruffey, S. H. (2014). “High-temperature pressing of silver-exchanged mordenite into a potential iodine waste form,” in Proc. WM2014 Conference, Phoenix, Arizona, USA, 2–6 March 2014 (Phoenix, AZ: U.S. Department of Energy).

Maddrell, E. R., Vance, E. R., Grant, C., Aly, Z., Stopic, A., Palmer, T., et al. (2019). Silver iodide sodalite – wasteform/Hip canister interactions and aqueous durability. J. Nucl. Mater. 517, 71–79. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.02.002

Maddrell, E. R., Vance, E. R., and Gregg, D. J. (2015). Capture of iodine from the vapour phase and immobilisation as sodalite. J. Nucl. Mater. 467, 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.09.038

Masuda, K., Kato, O., Tanaka, Y., Nakajima, S., Okamoto, S., Sakuragi, T., et al. (2016). Iodine immobilization: Development of solidification process for spent silver-sorbent using hot isostatic press technique. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 92, 267–272. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2015.09.012

Matyas, J., Canfield, N., Sulaiman, S., and Zumhoff, M. (2016). Silica-based waste form for immobilization of iodine from reprocessing plant off-gas streams. J. Nucl. Mater. 476, 255–261. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2016.04.047

Mukunoki, A., Chiba, T., Benino, Y., and Sakuragi, T. (2016). Microscopic structural analysis of lead borate-based glass. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 91, 339–344. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2016.05.008

NUMO (2018). The nuclear waste management organization of Japan (NUMO). Japan: NUMO Safety Case. NUMO-TR-18-03.

Riley, B. J., Vienna, J. D., Strachan, D. M., McCloy, J. S., and Jerden, J. L. (2016). Materials and processes for the effective capture and immobilization of radioiodine: A review. J. Nucl. Mater. 470, 307–326. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.11.038

Sakuragi, T., Nishimura, T., Nasu, Y., Asano, H., Hoshino, K., and Iino, K. (2008). Immobilization of radioactive iodine using AgI vitrification technique for the TRU wastes disposal: Evaluation of leaching and surface properties. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1107, 279–285. doi:10.1557/proc-1107-279

Sakuragi, T., Yamashita, Y., and Kikuchi, S. (2016). Effect of hydration heat on iodine distribution in gypsum additive calcium aluminate cement. Adv. Mater. Sci. Environ. Energy Technol. V Ceram. Trans. 260, 185–197. doi:10.1002/9781119323624.ch17

Sakuragi, T., Yoshida, S., Kato, O., and Masuda, K. (2015). Effects of hydrosulfide and pH on iodine release from an alumina matrix solid confining silver iodide. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1744, 21–28. doi:10.1557/opl.2015.393

Sakurai, T., Takahashi, A., Ye, M-l., Kihara, T., and Fujine, S. (1997). Trapping and measuring radioiodine (iodine-129) in cartridge filters. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 34, 211–216. doi:10.1080/18811248.1997.9733648

Stennett, M. C., Pinnock, I. J., and Hyatt, N. C. (2012). Rapid microwave synthesis of Pb5(VO4)3X (X=F, Cl, Br and I) vanadinite apatites for the immobilisation of halide radioisotopes. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1475, 221–226. doi:10.1557/opl.2012.580

Takeshita, K., and Azegami, Y. (2004). Development of thermal swing adsorption (TSA) process for complete recovery of iodine in dissolver off-gas. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 41, 91–94. doi:10.1080/18811248.2004.9715463

Vance, E. R., Grant, C., Karatchevtseva, I., Aly, Z., Stopic, A., Harrison, J., et al. (2018). Immobilization of iodine via copper iodide. J. Nucl. Mater. 505, 143–148. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2018.04.002

Vance, E. R., and Hartman, J. S. (1999). Effects of halides and sulphates in synroc-C. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 556, 41–46. doi:10.1557/proc-556-41

Vance, E. R., Perera, D. S., Moricca, S., Aly, Z., and Begg, B. D. (2005). Immobilisation of 129I by encapsulation in tin by hot-pressing at 200 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 341, 93–96. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2005.01.011

Yamashita, Y., Higuchi, S., Kaneko, M., Takahashi, R., Sakuragi, T., and Owada, H. (2016). Iodine release behavior from iodine-immobilized cement solid under geological disposal conditions. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 92, 273–278. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2016.04.016

Yang, J. H., Cho, Y. J., Shin, J. M., and Yim, M. S. (2015). Bismuth-embedded SBA-15 mesoporous silica for radioactive iodine capture and stable storage. J. Nucl. Mater. 465, 556–564. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.06.043

Keywords: waste management, TRU waste, iodine, AGA, sorption, mass transfer zone, immobilization, hot isostatic press

Citation: Sakuragi T, Yoshida S and Kato O (2023) Characteristics of iodine-bearing silver-impregnated alumina sorbents and their direct solidification via hot isostatic pressing. Front. Chem. 11:1089501. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2023.1089501

Received: 04 November 2022; Accepted: 03 January 2023;

Published: 23 January 2023.

Edited by:

Joshua Turner, National Nuclear Laboratory, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sam Walling, The University of Sheffield, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Sakuragi, Yoshida and Kato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomofumi Sakuragi, c2FrdXJhZ2lAcndtYy5vci5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.