- 1Department of Nuclear Engineering and Management, School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Photon Science Center, School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Research Institute for Photon Science and Laser Technology, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

We report the formulation of a new, cost-effective approximation method in the time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster (TD-OCC) framework [T. Sato et al., J. Chem. Phys. 148, 051101 (2018)] for first-principles simulations of multielectron dynamics in an intense laser field. The method, designated as TD-OCCD(T), is a time-dependent, orbital-optimized extension of the “gold-standard” CCSD(T) method in the ground-state electronic structure theory. The equations of motion for the orbital functions and the coupled-cluster amplitudes are derived based on the real-valued time-dependent variational principle using the fourth-order Lagrangian. The TD-OCCD(T) is size extensive and gauge invariant, and scales as O(N7) with respect to the number of active orbitals N. The pilot application of the TD-OCCD(T) method to the strong-field ionization and high-order harmonic generation from a Kr atom is reported in comparison with the results of the previously developed methods, such as the time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent field (TD-CASSCF), TD-OCC with double and triple excitations (TD-OCCDT), TD-OCC with double excitations (TD-OCCD), and the time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) methods.

1 Introduction

Recent years witnessed unprecedented progress in laser technologies, which made it possible to observe the motions of electrons at the attosecond time scale (Itatani et al. (2004); Corkum and Krausz (2007); Krausz and Ivanov (2009); Baker et al. (2006)). On the other hand, various theoretical and numerical methods have been developed for interpreting, understanding, and predicting the experiments.

The multi-configuration time-dependent Hartree-Fock (MCTDHF) method (Caillat et al. (2005); Kato and Kono (2004); Nest et al. (2005); Haxton et al. (2011); Hochstuhl and Bonitz (2011)), and the time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent-field (TD-CASSCF) method (Sato and Ishikawa (2013); Sato et al. (2016); Sato et al. (2018a)) are the most rigorous approaches to solve time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) of many-electron systems, where the wavefunction is given by the full configuration interaction (FCI) expansion,

with both CI coefficients {CI(t)} and orbital functions {ψp(t)} constituting Slater determinants {ΦI(t)} are propagated in time according to the time-dependent variational principle (TDVP). The TD-CASSCF method broadens the applicability of the MCTDHF method by flexibly classifying the orbital subspace into frozen-core, dynamical-core, and active. Unfortunately, the factorial computational scaling impedes large-scale applications. There are reports of various affordable size-inextensive methods (Miyagi and Madsen (2013, 2014); Haxton and McCurdy (2015); Sato and Ishikawa (2015)) developed by limiting the CI expansion of the wavefunction. Alternatively, the size-extensive coupled-cluster method, which relies on an exponential wavefunction, is a superior choice to address these problems with a polynomial cost-scaling (Kümmel (2003); Shavitt and Bartlett (2009)). We have developed an explicitly time-dependent coupled-cluster method considering optimized orthonormal orbitals within the flexibly chosen active space, called the time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster (TD-OCC) method, (Sato et al. (2018b)) including double (TD-OCCD) and double and triple excitation amplitudes (TD-OCCDT). Our method is a time-dependent formulation of the stationary optimized coupled-cluster method (Scuseria and Schaefer (1987); Sherrill et al. (1998); Krylov et al. (1998)). Kvaal (Kvaal (2012)) also developed an orbital adaptive time-dependent coupled-cluster (OATDCC) method using biorthogonal orbitals. We take note of a few reports on the time-dependent coupled-cluster methods (Huber and Klamroth (2011); Pigg et al. (2012); Nascimento and DePrince (2016)), using time-independent orbitals, and their interpretation (Pedersen and Kvaal (2019); Pedersen et al. (2021)), including the very initial attempts (Schonhammer (1978); Hoodbhoy and Negele (1978, 1979)).

The TD-OCCDT scales as O(N8) (N= the number of active orbitals), not ideally suited for applications to larger chemical systems. Therefore, we have developed a few lower cost methods in the TD-OCC framework (Pathak et al. (2020b,c,a, 2021)). We find triple excitations are necessary, including perfect optimization of the orbitals. Therefore, we are interested in developing affordable TD-OCC methods retaining a part of the triples. The most popular coupled-cluster method that treats the triple excitation amplitudes approximately is called CCSD(T) (Raghavachari et al. (1989); Watts et al. (1993)). Bozkaya et al, (Bozkaya and Schaefer (2012)) included various symmetric and asymmetric triple excitation corrections to their optimized double (OD) method.

In this communication, we report the formulation and implementation of the CCSD(T) method in the time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster framework, TD-OCCD(T). Following our previous works (Sato et al. (2018b); Pathak et al. (2020b,c, 2021)), we exclude single excitation amplitudes but optimize the orbitals according to time-dependent variational principle (TDVP). As the first application of this method, we study electron dynamics in Kr using intense near-infrared laser fields.

2 Methods

The second quantization representation of the Hamiltonian, including the laser field, is as follows,

where

where xi = (ri, σi) represents a composite spatial-spin coordinate. h0 is the field free one-electronic Hamiltonian and Vext = A(t)pz in the velocity gauge, A(t) = −∫tE(t′)dt′ is the vector potential, with E(t) being the laser electric field linearly polarized along the z axis.

The complete set of 2nbas spin-orbitals (labeled with μ, ν, γ, λ) is divided into nocc occupied (o, p, q, r, s) and 2nbas − nocc virtual spin-orbitals. The coupled-cluster (or CI) wavefunction is constructed only with occupied spin-orbitals, which are time-dependent in general, and virtual spin-orbitals form the orthogonal complement of the occupied spin-orbital space. The occupied spin-orbitals are classified into ncore core spin-orbitals, which are occupied in the reference Φ and kept uncorrelated, and N = nocc − ncore active spin-orbitals (t, u, v, w) among which the active electrons are correlated. The active spin-orbitals are further split into those in the hole space (i, j, k, l) and the particle space (a, b, c, d), which are defined as those occupied and unoccupied, respectively, in the reference Φ. The core spin-orbitals can further be split into frozen-core space (i′′, j′′), fixed in time and the dynamical-core space (i′, j′), propagated in time (Sato and Ishikawa (2013)) (See. Figure 1 in Sato et al. (2018b) for a pictorial illustration).

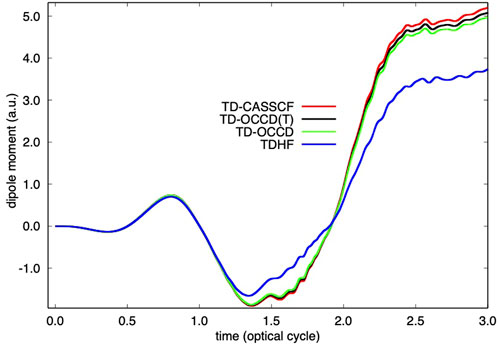

FIGURE 1. Time evolution of dipole moment of Kr irradiated by a laser pulse with a wavelength of 800 nm and a peak intensity of 2 × 1014 W/cm2 calculated with TDHF, TD-OCCD, TD-OCCD(T), and TD-CASSCF methods.

The real action formulation of the TDVP with orthonormal orbitals is our guiding principle, (Sato et al. (2018b))

where

For deriving the TD-OCCD(T) method, we first construct a fourth-order Lagrangian defined in Pathak et al. (2021). We make a further approximation to the Lagrangian and write separating it into two parts,

where

where p(μν) and p(μ|νγ) are the permutation operators; p(μν)Aμν = Aμν − Aνμ, and p(μ/νγ) = 1 − p(μν) − p(μγ).

The EOM for the orbitals can be written down in the following form Sato et al. (2016),

where

where D and P are Hermitialized one- (1RDM) and two- (2RDM) particle reduced density matrices defined in Sato et al. (2018b), and

3 Numerical results and discussion

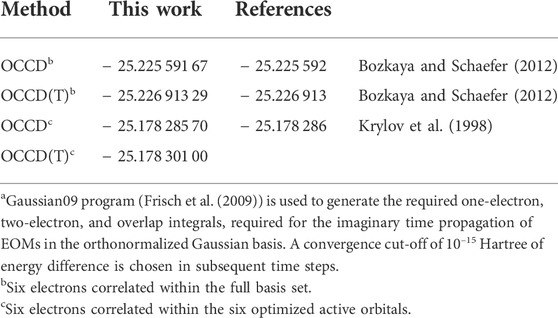

Our numerical implementation has an interface with the Gaussian09 program (Frisch et al. (2009)) for checking ground state energy with the standard Gaussian basis results. We study BH molecule with double-ζ plus polarization (DZP). We have reported ground state energy computed by propagating in the imaginary time for OCCD and OCCD(T) methods in Table 1 and compared those with the optimized double and asymmetric triple excitation corrections for the orbital-optimized doubles method of Bozkaya et al., Bozkaya and Schaefer (2012). We also compare our OCCD ground state energy result with Krylov et al.,Krylov et al. (1998) within the chosen active space of six electrons correlated among the six optimized active orbitals. We obtained a perfect agreement for all available values.

TABLE 1. Comparison of the ground state energy of BH (re=2.4 bohr) molecule in DZP basisa.

We have used a spherical-finite-element-discrete-variable representation (FEDVR) basis for representing orbital functions, Sato et al. (2016); Orimo et al. (2018)

We report the time evolution of dipole moment of Kr in Figure 1 and in Figure 2 single electron ionization probability. Time-dependent dipole moment is evaluated as a trace

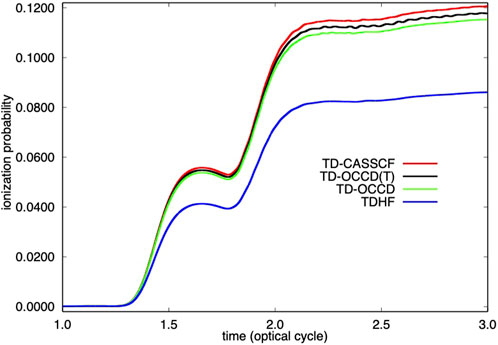

FIGURE 2. Time evolution of single ionization probability of Kr irradiated by a laser pulse with a wavelength of 800 nm and a peak intensity of 2 × 1014 W/cm2 calculated with TDHF, TD-OCCD, TD-OCCD(T), and TD-CASSCF methods.

We observe a substantial underestimation (both in Figure 1, and Figure 2) by the TDHF method due to the lack of correlation treatment. All correlation methods perform according to their ability to treat electron correlation. We also computed results using the TD-OCCDT method but not reported here since those results are not identifiable from the TD-CASSCF results within the graphical resolution.

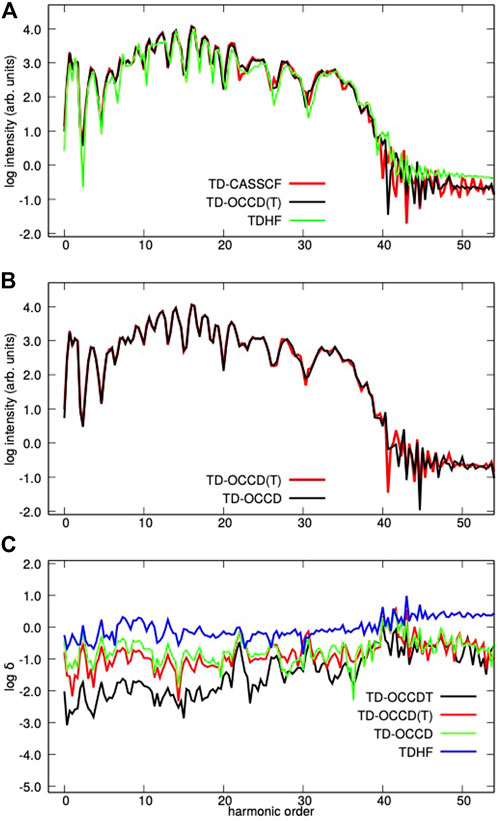

Next, we report high-harmonic generation in Figure 3. It is calculated by squaring the modulus I(ω) = |a(ω)|2 of the Fourier transform of the expectation value of the dipole acceleration with a modified Ehrenfest expression (Sato et al. (2016)). In panel (c) of Figure 3, we plot the absolute relative deviation (δ(ω), of the spectral amplitude a(ω) from the TD-CASSCF value for each method. All methods qualitatively predict similar HHG spectra with TDHF underestimates the spectral intensity. The relative deviation of results from TD-CASSCF ones follows the general trend TDHF

FIGURE 3. The HHG spectra (A,B) and the relative deviation (C) of the spectral amplitude from the TD-CASSCF spectrum from Kr irradiated by a laser pulse with a wavelength of 800 nm and a peak intensity of 2 × 1014 W/cm2 with various methods.

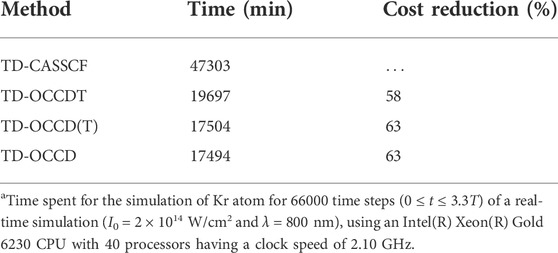

Finally, we make a tally of computational costs for all the methods considered in this article. All simulations performed using an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6,230 central processing unit (CPU) with 40 processors with a clock speed of 2.10 GHz, and report total simulations time in Table 2. Further, we report a reduction in the computational cost for various TD-OCC methods relative to the TD-CASSCF. We see a massive 63% cost reduction for the TD-OCCD(T) method, which is larger than for the TD-OCCDT method (58%), and a minimal increase from the TD-OCCD method.

TABLE 2. Comparison of the total simulation timea (in min) spent for TD-CASSCF, TD-OCCDT, TDCCD(T), and TD-OCCD methods.

4 Concluding remarks

We have reported the formulation and implementation of the TD-OCCD(T) method. As the first application, we employed this method to study laser-driven dynamics in Kr exposed to an intense near-infrared laser pulse. We observe a 63% cost reduction in comparison to the TD-CASSCF method without losing much accuracy. Therefore, we conclude that TD-OCCD(T) method will certainly be beneficial in exploring highly accurate ab initio simulations of electron dynamics in larger chemical systems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HP and TS formulated the method. HP numerically implemented the method and performed simulations. All the authors analyzed the results and contributed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grants No. JP18H03891 and No. JP19H00869) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. This research was also partially supported by JST COI (Grant No. JPMJCE1313), JST CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR15N1), and by MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT Q-LEAP) Grant Number JPMXS0118067246.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baker, S., Robinson, J. S., Haworth, C., Teng, H., Smith, R., Chirilă, C., et al. (2006). Probing proton dynamics in molecules on an attosecond time scale. Science 312, 424–427. doi:10.1126/science.1123904

Bozkaya, U., and Schaefer, H. F. (2012). Symmetric and asymmetric triple excitation corrections for the orbital-optimized coupled-cluster doubles method: Improving upon ccsd (t) and ccsd (t) λ: Preliminary application. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 204114. doi:10.1063/1.4720382

Caillat, J., Zanghellini, J., Kitzler, M., Koch, O., Kreuzer, W., and Scrinzi, A. (2005). Correlated multielectron systems in strong laser fields: A multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree-Fock approach. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 71, 012712. doi:10.1103/physreva.71.012712

Corkum, P. á., and Krausz, F. (2007). Attosecond science. Nat. Phys. 3, 381–387. doi:10.1038/nphys620

[Dataset] Frisch, M., Trucks, G., Schlegel, H., Scuseria, G., Robb, M., Cheeseman, J., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, revision d. 01.

Haxton, D. J., Lawler, K. V., and McCurdy, C. W. (2011). Multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree-Fock treatment of electronic and nuclear dynamics in diatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 83, 063416. doi:10.1103/physreva.83.063416

Haxton, D. J., and McCurdy, C. W. (2015). Two methods for restricted configuration spaces within the multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree-Fock method. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 91, 012509. doi:10.1103/physreva.91.012509

Hochbruck, M., and Ostermann, A. (2010). Exponential integrators. Acta Numer. 19, 209–286. doi:10.1017/s0962492910000048

Hochstuhl, D., and Bonitz, M. (2011). Two-photon ionization of helium studied with the multiconfigurational time-dependent Hartree–Fock method. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 084106. doi:10.1063/1.3553176

Hoodbhoy, P., and Negele, J. W. (1978). Time-dependent coupled-cluster approximation to nuclear dynamics. i. application to a solvable model. Phys. Rev. C 18, 2380–2394. doi:10.1103/physrevc.18.2380

Hoodbhoy, P., and Negele, J. W. (1979). Time-dependent coupled-cluster approximation to nuclear dynamics. ii. general formulation. Phys. Rev. C 19, 1971–1982. doi:10.1103/physrevc.19.1971

Huber, C., and Klamroth, T. (2011). Explicitly time-dependent coupled cluster singles doubles calculations of laser-driven many-electron dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 054113. doi:10.1063/1.3530807

Itatani, J., Levesque, J., Zeidler, D., Niikura, H., Pépin, H., Kieffer, J. C., et al. (2004). Tomographic imaging of molecular orbitals. Nature 432, 867–871. doi:10.1038/nature03183

Kato, T., and Kono, H. (2004). Time-dependent multiconfiguration theory for electronic dynamics of molecules in an intense laser field. Chem. Phys. Lett. 392, 533–540. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2004.05.106

Krausz, F., and Ivanov, M. (2009). Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 163–234. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.81.163

Krylov, A. I., Sherrill, C. D., Byrd, E. F., and Head-Gordon, M. (1998). Size-consistent wave functions for nondynamical correlation energy: The valence active space optimized orbital coupled–cluster doubles model. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 10669–10678. doi:10.1063/1.477764

Kümmel, H. G. (2003). A biography of the coupled cluster method. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 17, 5311–5325. doi:10.1142/s0217979203020442

Kvaal, S. (2012). Ab initio quantum dynamics using coupled-cluster. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 194109. doi:10.1063/1.4718427

Miyagi, H., and Madsen, L. B. (2013). Time-dependent restricted-active-space self-consistent-field theory for laser-driven many-electron dynamics. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 87, 062511. doi:10.1103/physreva.87.062511

Miyagi, H., and Madsen, L. B. (2014). Time-dependent restricted-active-space self-consistent-field theory for laser-driven many-electron dynamics. ii. extended formulation and numerical analysis. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 89, 063416. doi:10.1103/physreva.89.063416

Nascimento, D. R., and DePrince, A. E. (2016). Linear absorption spectra from explicitly time-dependent equation-of-motion coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 5834–5840. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00796

Nest, M., Klamroth, T., and Saalfrank, P. (2005). The multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree–Fock method for quantum chemical calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 124102. doi:10.1063/1.1862243

Orimo, Y., Sato, T., Scrinzi, A., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2018). Implementation of the infinite-range exterior complex scaling to the time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent-field method. Phys. Rev. A. Coll. Park. 97, 023423. doi:10.1103/physreva.97.023423

Pathak, H., Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2020a). Study of laser-driven multielectron dynamics of ne atom using time-dependent optimised second-order many-body perturbation theory. Mol. Phys. 118, e1813910. doi:10.1080/00268976.2020.1813910

Pathak, H., Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2021). Time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster method for multielectron dynamics iv: Approximate consideration of the triple excitation amplitudes. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 234104. doi:10.1063/5.0054743

Pathak, H., Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2020b). Time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster method for multielectron dynamics. ii. a coupled electron-pair approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 124115. doi:10.1063/1.5143747

Pathak, H., Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2020c). Time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster method for multielectron dynamics. iii. a second-order many-body perturbation approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 034110. doi:10.1063/5.0008789

Pedersen, T. B., Kristiansen, H. E., Bodenstein, T., Kvaal, S., and Schøyen, Ø. S. (2021). Interpretation of coupled-cluster many-electron dynamics in terms of stationary states. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 388–404. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00977

Pedersen, T. B., and Kvaal, S. (2019). Symplectic integration and physical interpretation of time-dependent coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 144106. doi:10.1063/1.5085390

Pigg, D. A., Hagen, G., Nam, H., and Papenbrock, T. (2012). Time-dependent coupled-cluster method for atomic nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 86, 014308. doi:10.1103/physrevc.86.014308

Raghavachari, K., Trucks, G. W., Pople, J. A., and Head-Gordon, M. (1989). A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157, 479–483. doi:10.1016/s0009-2614(89)87395-6

Sato, T., Ishikawa, K. L., Březinová, I., Lackner, F., Nagele, S., and Burgdörfer, J. (2016). Time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent-field method for atoms: Application to high-order harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 94, 023405. doi:10.1103/physreva.94.023405

Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2013). Time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent-field method for multielectron dynamics in intense laser fields. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 88, 023402. doi:10.1103/physreva.88.023402

Sato, T., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2015). Time-dependent multiconfiguration self-consistent-field method based on the occupation-restricted multiple-active-space model for multielectron dynamics in intense laser fields. Phys. Rev. A . Coll. Park. 91, 023417. doi:10.1103/physreva.91.023417

Sato, T., Orimo, Y., Teramura, T., Tugs, O., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2018a). “Time-dependent complete-active-space self-consistent-field method for ultrafast intense laser science,” in Progress in ultrafast intense laser science XIV (Berlin, Germany: Springer), 143–171.

Sato, T., Pathak, H., Orimo, Y., and Ishikawa, K. L. (2018b). Communication: Time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster method for multielectron dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 051101. doi:10.1063/1.5020633

Schonhammer, K., and Gunnarsson, O. (1978). Time-dependent approach to the calculation of spectral functions. Phys. Rev. B 18, 6606. doi:10.1103/physrevb.18.6606

Scuseria, G. E., and Schaefer, H. F. (1987). The optimization of molecular orbitals for coupled cluster wavefunctions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 142, 354–358. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(87)85122-9

Shavitt, I., and Bartlett, R. J. (2009). Many-body methods in chemistry and physics: MBPT and coupled-cluster theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sherrill, C. D., Krylov, A. I., Byrd, E. F., and Head-Gordon, M. (1998). Energies and analytic gradients for a coupled-cluster doubles model using variational brueckner orbitals: Application to symmetry breaking in o 4+. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 4171–4181. doi:10.1063/1.477023

Keywords: multielectron dynamics, time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster, high harmonic generation, strong laser field, strong field ionization

Citation: Pathak H, Sato T and Ishikawa KL (2022) Time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster method with doubles and perturbative triples for first principles simulation of multielectron dynamics. Front. Chem. 10:982120. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.982120

Received: 30 June 2022; Accepted: 09 August 2022;

Published: 13 September 2022.

Edited by:

Yuichi Fujimura, Tohoku University, JapanReviewed by:

Xiaowei Sheng, Anhui Normal University, ChinaShu Ohmura, Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan

Copyright © 2022 Pathak, Sato and Ishikawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takeshi Sato, c2F0b0BhdHRvLnQudS10b2t5by5hYy5qcA==

Himadri Pathak

Himadri Pathak Takeshi Sato

Takeshi Sato Kenichi L. Ishikawa

Kenichi L. Ishikawa