95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 09 May 2022

Sec. Chemical Physics and Physical Chemistry

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.888033

This article is part of the Research Topic Efficient Near-Infrared-Emitting Materials: Design, Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Applications View all 5 articles

Yule Zhang1†

Yule Zhang1† Yatian Zhang2†

Yatian Zhang2† Zhijin Yang1

Zhijin Yang1 Yan Fan1

Yan Fan1 Mengya Chen1

Mengya Chen1 Mantong Zhao3

Mantong Zhao3 Bo Dai1

Bo Dai1 Lulu Zheng1*

Lulu Zheng1* Dawei Zhang1,4*

Dawei Zhang1,4*Iron oxide (Fe3O4), a classical magnetic material, has been widely utilized in the field of biological magnetic resonance imaging Graphene oxide (GO) has also been extensively applied as a drug carrier due to its high specific surface area and other properties. Recently, numerous studies have synthesized Fe3O4/GO nanomaterials for biological diagnosis and treatments, including photothermal therapy and magnetic thermal therapy. However, the biosafety of the synthesized Fe3O4/GO nanomaterials still needs to be further identified. Therefore, this research intended to ascertain the cytotoxicity of Fe3O4/GO after treatment with different conditions in HBE cells. The results indicated the time-dependent and concentration-dependent cytotoxicity of Fe3O4/GO. Meanwhile, exposure to Fe3O4/GO nanomaterials increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, calcium ions levels, and oxidative stress in mitochondria produced by these nanomaterials activated Caspase-9 and Caspase-3, ultimately leading to cell apoptosis.

Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Fe3O4 NPs) are also a classical magnetic substance, which have attracted increasing attention because they have been successfully approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in MRI (Chen et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2021). Currently, Fe3O4 NPs are frequently used in MRI, biological separation, hyperthermia therapy, and other biomedical fields.

As another interesting nanocomponent commonly employed in drug delivery, GO has hydrophilic and hydrophobic oxygen-containing functional groups, like hydroxyl, carboxyl, and epoxy groups, making it easily soluble in water and various organic solvents (Metin et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2018). Its unusual properties, including electrical, optical, thermal, and mechanical properties, are predominantly determined by the chemical structure of the Sp3 carbon domain surrounded by the Sp2 carbon domain (Zakharova et al., 2021). On the other hand, GO has another critical feature of its structure with a large specific surface area. GO has become the focus of widespread interest in the field of materials over the past few years because of its unique thermal, electronic, and optical properties, and high drug delivery rate of up to 200% (Vannozz et al., 2021). Therefore, GO-based nanocomposites have aroused extensive attention in the biomedical field, especially in the diagnosis and treatment of tumors.

Mounting literature indicated that the GO coupled with magnetic nanoparticles could serve as a potential material for the diagnosis and treatment of cancers (Chen H. et al., 2021). Currently, several researches reported various methods to synthesize magnetic and graphite nanostructured composites (Fe3O4/GO) for catalytic, water purification, biomedical diagnostic, and therapeutic applications (Jedrzejczak-Silicka, 2017; Yan et al., 2019; Niu et al., 2021; Sadighian et al., 2021). This combination of topical hyperthermia materials is also regarded as a promising candidate for drug delivery (Karimi and Namazi, 2021; Wen et al., 2021). Nowadays, some of these attractive metal oxides have been documented to be cytotoxic and genotoxic, potentially leading to the destruction of mitochondrial membrane integrity, DNA fragmentation, and cell death (Li et al., 2018). Due to the tremendous potential of Fe3O4/GO in biomedical and other fields, recent researches have focused on the potential cytotoxicity and genetic toxicity of these hybrids (Ahamed et al., 2020; Zhang H. et al., 2020). However, the relationship of Fe3O4/GO exposure with ROS and calcium ion levels and apoptosis remains enigmatic. Advances in understanding the relationship between physicochemical parameters and the potential cytotoxic impacts of synthetic hybrids, including these analyses, need to be clarified and should correspond to mainstream nanotechnology and its wide range of biomedical applications (Qiang et al., 2021). Therefore, this study set out to evaluate cellular responses, including ROS levels, calcium ion levels, mitochondrial superoxide levels, and apoptosis levels of human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cell lines, after Fe3O4/GO exposure.

As reported, calcium influx can activate Caspase-9 to facilitate the cleavage of Caspase-3 and activate Caspase-3, contributing to cell apoptosis (Valdiglesias, 2022; Ayse Kaplan et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2005). In this study, we investigated the cytotoxicity of Fe3O4/GO after incubation with HBE cells. The results manifested that exposure to Fe3O4/GO with high concentration increased ROS levels, Ca2+ influx, and mitochondrial dysfunction and then induced apoptosis. It was verified that nanomaterial exposure augmented oxidative stress, calcium influx, and mitochondrial superoxide generation, which promoted the activation of Caspase-9/Caspase-3, ultimately resulting in cell apoptosis.

All chemical reagents for synthetic materials were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Reagents used in cell culture such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin were provided by Gibco, Invitrogen. Cell count kit-8 (cck-8) and Fluo-4AM were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology. 2'7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), Mitosox red, and 4', 6-diamidine-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) were provided by Sigma–Aldrich. Antibodies of Caspase-9/Caspase-3 were obtained from a protein technology company. The secondary antibody used Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse and Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit, which were purchased from Servicebio. Calcein-AM/PI and Annexin-V/PI double staining kits were purchased from Dojindo laboratories.

In order to produce Fe3O4/GO, glycine is used as a linker. First, 20 mg Fe3O4 nanospheres were dispersed in 0.5 mg/ml water, ultrasonic treatment until uniform dispersion, and then functionalized with glycine so that the -NH2 group was attached to its surface. 20 mg GO sample was ultrasonically stripped in 60 ml H2O to generate a homogeneous GO aqueous suspension. The carboxyl groups on the surface of GO were then activated by 8 mg N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 10 mg 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl-1)-3-ethylcarbondiimide (EDC). The mixture of modified Fe3O4 and GO was stirred for 2 h, and the resulting product was centrifuged, washed with water and ethanol several times, and dried at 100°C.

The images of NP morphology were obtained using a transmission electron microscope (TEM; Philips/FEI Company CM300 FEG-ST). Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was analyzed by IRTracer-100, Japan. Hydrodynamic sizes of Fe3O4/GO were evaluated by dynamic light scattering (DLS) via Malvern (Zetasizer Nano S90) in water and DMEM, respectively. The Zeta potential of Fe3O4/GO was analyzed by Malvern, Zetasizer Nano S90.

HBE cells and Ad12-SV40 2B (BEAS-2B) cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, United States). Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell viability was measured by cck-8. HBE cells and BEAS-2B cells were seeded in 96-well plates overnight and Fe3O4/GO in DMEM was added to each well at a dose of 0, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml for 3 replicates per group. HBE cells were tested after 6, 12, 24, and 48 h of co-incubation and BEAS-2B cells were tested after 12, 24 h of co-incubation later according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

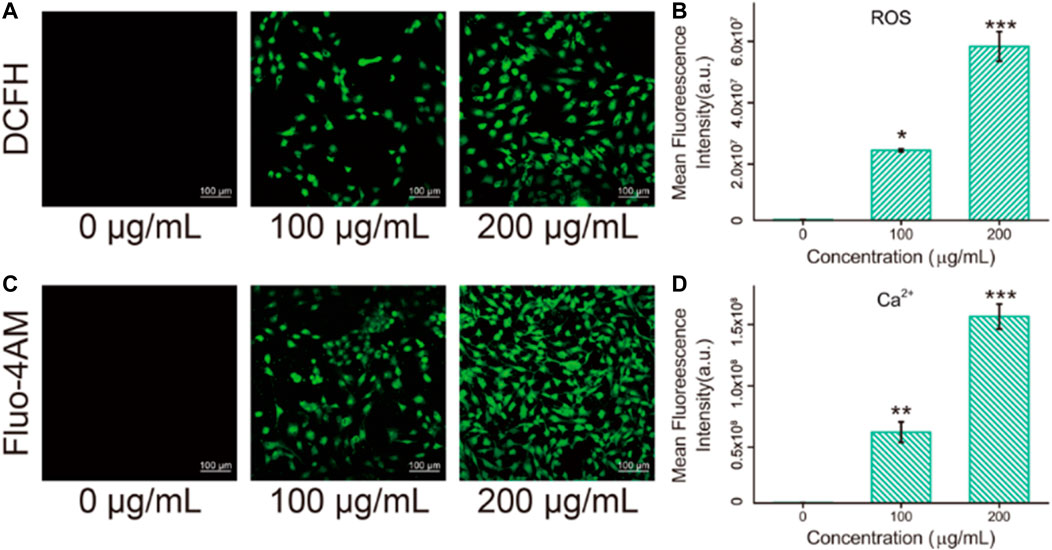

Oxidative stress changes are represented by reactive oxygen species (ROS). The fluorescence intensity of DCFH-DA is the most commonly used method to detect intracellular ROS levels. HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (0, 100, 200 μg/ml) in DMEM was added and then coincubated after 24 h. Then, it was cleaned with PBS three times, then prepared DCFH-DA staining solution was added and incubated for 15 min. It was cleaned with PBS three times, observed, and analyzed by using a confocal microscope (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany) (Ex: 505 nm Em: 525 nm).

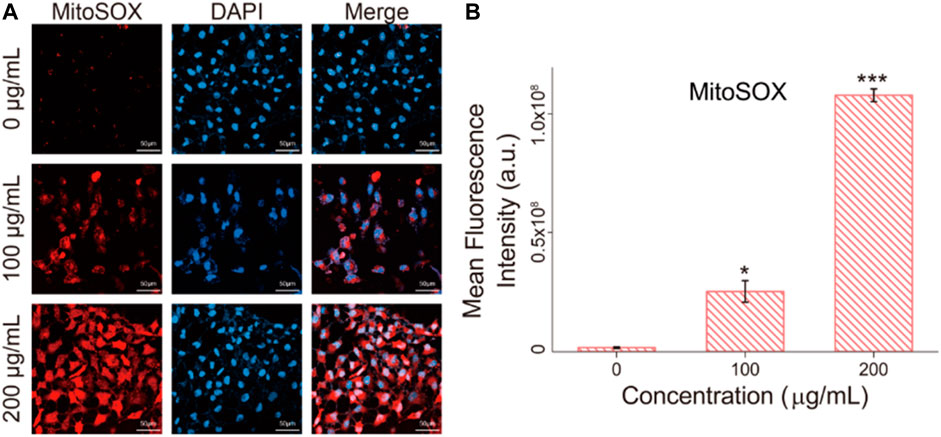

Mitosox red is a mitochondrial superoxide indicator. HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (0, 100, 200 μg/ml) in DMEM was added and then coincubated after 24 h. Then, it was cleaned with PBS three times, prepared Mitosox red and DAPI staining solution was added and incubated for 15 min. It was cleaned with PBS three times, observed, and analyzed via a confocal microscope (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany) (Mitosox red, Ex: 510 nm Em: 580 nm; DAPI, Ex: 350 nm Em: 461 nm).

Ca2+ levels were detected by Fluo-4AM. HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (0, 100, 200 μg/ml) was added and then co-incubated for 24 h. Then, it was cleaned with PBS three times and then prepared Fluo-4AM staining solution was added, and incubated for 15 min. It was cleaned with PBS three times, observed, and analyzed under a confocal microscope (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany) (Ex: 494 nm Em: 516 nm).

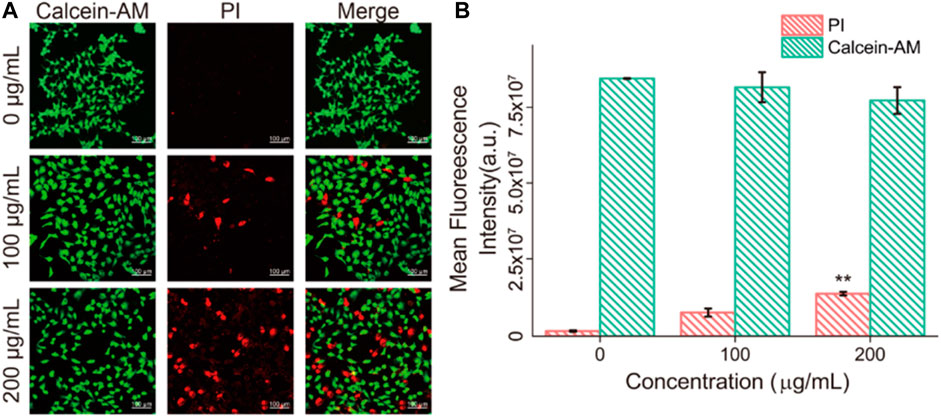

Dead/live cells were analyzed by using a calcein-AM/PI double staining kit. HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (0, 100, 200 μg/ml) in DMEM was added and then coincubated for 24 h. Then, it was cleaned with PBS three times and prepared calcein-AM/PI staining solution was added and incubated for 15 min. It was cleaned with PBS three times, observed, and analyzed under a confocal microscope (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany) (Calcein-AM, Ex: 490 nm Em: 515 nm; PI, Ex: 530 nm Em: 617 nm).

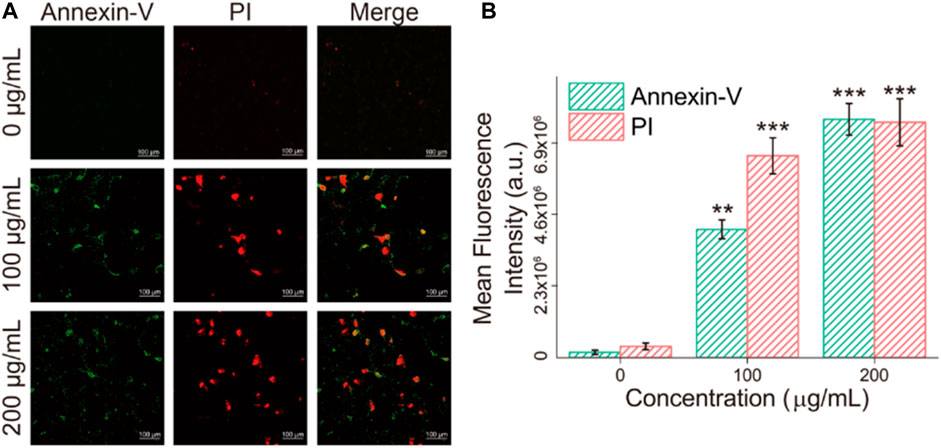

HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (0, 100, 200 μg/ml) in DMEM was added and then coincubated for 24 h. Then, cells were stained with Annexin-V FITC/PI and analyzed by confocal microscope. (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany) (Annexin-V FITC, Ex: 488 nm Em: 515 nm; PI, Ex: 530 nm Em: 617 nm).

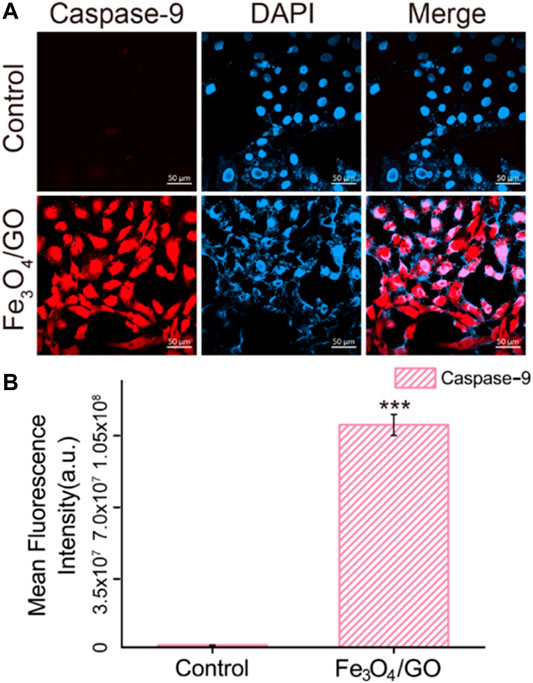

HBE cells were seeded in confocal dishes overnight. Fe3O4/GO (200 μg/ml) in DMEM was added and then co-incubated for 24 h. Then, cells were immunofluorescence stained by Caspase-3 antibody and Caspase-9 antibody and observed under a confocal microscope (LSM 900, ZEISS, Germany).

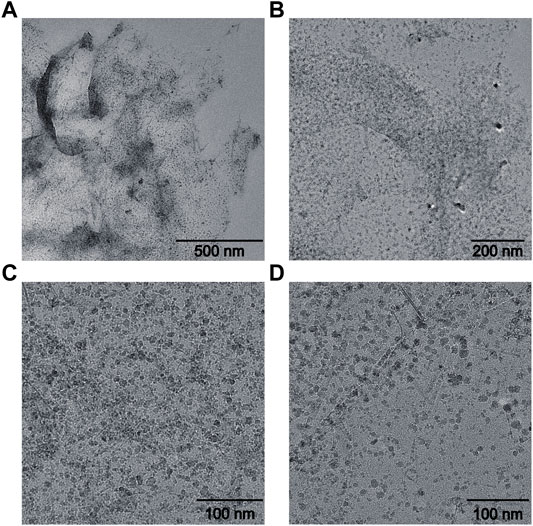

It could be found that GO showed transparent sheet-like gauze with folds at the edge of the sheet. The research of Ajayan et al. suggested that folding was majorly attributable to the destruction of the C=C double bond caused by Sp2 hybrid oxygen-containing functional groups on the graphite oxide (Datta et al., 2018; Sadighian et al., 2021). Fe3O4 particles prepared by a coprecipitation method have a diameter of approximately 10 nm. However, due to the interaction between coulomb force and van der Waals force among the nanoparticles, a few of the nanoparticles exhibit the agglomeration phenomenon (Dyer et al., 2015; Fu and Li, 2014). Therefore, some Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the composite have a particle size of 30–50 nm after agglomeration in Figure 1 (Narayanaswamy and Srivastava, 2017). However, the overall dispersion is favorable.

FIGURE 1. TEM characterization of Fe3O4/GO. (A) scale bar: 500 nm, (B) scale bar: 200 nm, (C–D) scale bar: 100 nm.

As displayed in Figure 2, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of Fe3O4/GO was analyzed. The absorption peak at 3,434 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of OH from GO, and the absorption peak near 2,926 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of CH2 from synthetic Fe3O4/GO (Hanh et al., 2018). The absorption peak at 1,624 cm−1 was accounted for by the C=O stretching vibration at the GO edge (Narayanaswamy and Srivastava, 2017). The absorption peak at 1,379 cm−1 was caused by the C-O-C stretching vibration on the GO surface (Seyyed et al., 2021). The absorption peak at 580 cm−1 was induced by the stretching vibration of Fe-O-Fe (Zhang et al., 2017). In summary, it was indicated that Fe3O4/GO nanoparticle complex with high purity was prepared.

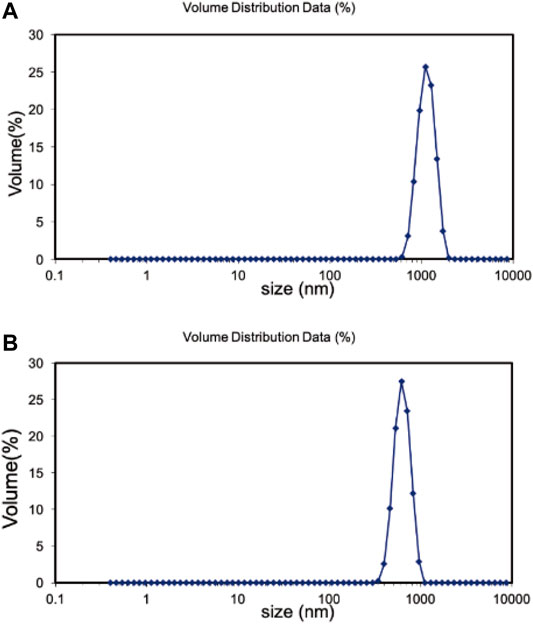

The hydration particle size of Fe3O4/GO was analyzed in deionized (DI) water and DMEM, respectively by DLS. As shown in Figure 3A, Fe3O4/GO was 1,325 nm in dH2O. There is a certain aggregation in DI water, so the measured particle size is larger. Due to the presence of serum in the medium, the serum protein such as albumin could form a corona which stabilization of the materials in the suspension (Wang et al., 2016). Thus, Fe3O4/GO had better dispersion in the medium with a particle size of 1,164 nm in Figure 3B. The Zeta potential of materials was in the range of 3.96 mV and −13.6 mV in DI water and DMEM, respectively, which changes the positive charge in DI to negative charge in DMEM (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. (A) Hadrodynamic sizes (nm) of Fe3O4/GO in dH2O. (B) Hadrodynamic sizes (nm) of Fe3O4/GO in DMEM.

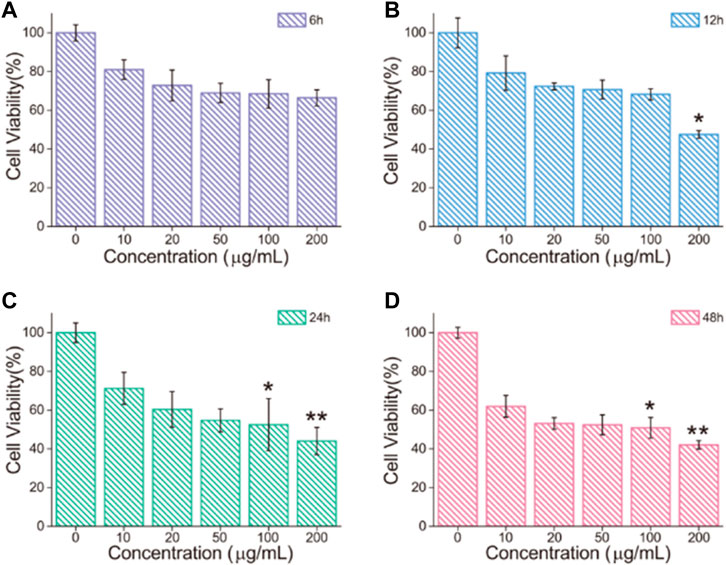

It was evaluated at different concentration and different times of Fe3O4/GO cytotoxicity via cck-8 assay, respectively. HBE cells were cultured with different concentrations (0, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml) of Fe3O4/GO, and cell viability was detected after 6, 12, 24, and 48 h by cck-8 assay. As shown in Figure 5A, the cell survival rate still reached more than 60% after 6 h Fe3O4/GO exposure at 200 μg/ml. In short periods, even high concentrations of Fe3O4/GO can have a rational biosafety profile. After 12 h, we can significantly infer that cell viability was decreased to 47.55% after the highest concentration of Fe3O4/GO exposure shown in Figure 5B. Compared with Figure 5A, the results indicated that cytotoxicity of Fe3O4/GO was time-dependent. In Figures, 5C,D, HBE cell viability was only around 40% after 24 and 48 h Fe3O4/GO stimulation at the concentration of 200 μg/ml. It is worth noting that cell viability was less than 60% after 48 h, even at low concentrations (20 μg/ml). However, other reports indicated that these nanoparticles had the potential to produce toxic effects in cells, and their toxic effects were related to their size, concentration, time, shape, and the cell type (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang S. et al., 2020). Thus, we also verified the cytotoxicity effects of Fe3O4/GO in BEAS-2B cells, which also belong to human lung epithelial cells. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, with an increasing concentration of Fe3O4/GO, the BEAS-2B cell’s cytotoxicity was Fe3O4/GO nanosheet concentration-dependent and time-dependent after 12 and 24 h co-incubation. This study showed that the cytotoxicity effects of Fe3O4/GO on cells was time-dependent and concentration-dependent.

FIGURE 5. (A–D) HBE cell viability after treatment with different concentrations of Fe3O4/GO for 6, 12, 24 and 48 h, respectively, (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

The imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants favors oxidants and may culminate in so-called “oxidative stress” (Salvador et al., 2021). As a product of oxidative stress reaction, ROS produced by the interaction between nanomaterials and cells has been reported as one of the pivotal causes of cell damage. It has been previously reported by several researchers that ROS [such as superoxide anions (O2•−), hydroxyl radicals (HO•), and hydrogen peroxide] levels could enhance in human cells after exposure to Fe3O4/GO nanosheets. Literature also unravels that iron oxide nanoparticles can induce cytotoxicity by activating oxidative stress responses (Ahamed et al., 2020). To further detect whether Fe3O4/GO induces ROS production in HBE cells, DCFH staining was used. Oxidative stress levels were expressed as ROS levels and detected by DCFH fluorescent probe. As shown in Figure 6A, it can be found that the green fluorescence (DCFH fluorescent probe) in the cells increased significantly in response to Fe3O4/GO concentration after 24 h of co-incubation, indicating that the oxidative stress level of the cells increases significantly after Fe3O4/GO stimulation. In addition, our quantitative data (Figure 6B) showed that ROS levels in the Fe3O4/GO group were significantly higher than in other control group in a concentration-dependent manner. These results suggested that Fe3O4/GO induced ROS production and resulted in oxidative stress in HBE cells.

FIGURE 6. (A) ROS levels in HBE cells were detected by DCFH after co-incubation with different concentration of Fe3O4/GO after 24 h (scale bar: 100 μm). (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of DCFH after co-incubation for 24 h. (C) Ca2+ levels in HBE cells were detected by Fluo-4AM after co-incubation with different concentration of Fe3O4/GO after 24 h (scale bar: 100 μm). (D) Mean fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4AM after co-incubation for 24 h.

Fluo-4AM was used to detect the calcium ion levels in cells by means of confocal observation. As shown in Figures 6C, D, fluorescence intensity enhanced significantly with the increase of concentration after coincubation with Fe3O4/GO for 24 h. Most studies elucidated that ROS in the mitochondrial respiratory chain could elevate Ca2+ levels (Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, intracellular free Ca2+ may be implicated in the mechanisms of apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2015). In this study, it was confirmed that Fe3O4/GO induced ROS generation and Ca2+ influx in HBE cells. Considering that calcium signaling is a crucial manipulator of cell function, ER is the dominant source of intracellular calcium and assumes an essential role in the process of cell apoptosis. Following Fe3O4/GO exposure, intracellular calcium levels were increased by releasing Ca2+ of ER. The disruption of intracellular calcium homeostasis contributes to calcium metabolism disorders and impairs protein folding. The long-term accumulation of misfolded proteins in ER results in ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Thus, we can infer that Fe3O4/GO may lead to HBE apoptosis via ROS-induced Ca2+ influx, which was verified in subsequent experiments.

Mitochondrial dysfunction was verified by Mitosox red, which is a mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Wang et al., 2013). Mitochondria are stimulated to produce mitochondrial superoxide, which leads to impaired mitochondrial function. As shown in Figure 7, after Fe3O4/GO exposure, red fluorescent was enhanced with concentration increased, which indicated mitochondrial generated superoxide. We can infer that ER-Ca2+ may induce mitochondrial dysfunction, after Fe3O4/GO exposure.

FIGURE 7. (A) mitochondrial superoxide levels in HBE cells were detected by Mitosox red after co-incubation with different concentration of Fe3O4/GO after 24 h (scale bar: 50 μm). (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of Mitosox red after co-incubation for 24 h.

The state of dead and alive cells was verified by calcein-AM/PI staining, where calcein-AM represented living cells (green fluorescent) and PI (red fluorescent) represented dead cells (Zheng et al., 2020). Figure 8 showed that after 24 h coincubation with Fe3O4/GO, part of the HBE cells died and the amount of dead cells response to increased Fe3O4/GO concentration.

FIGURE 8. (A) HBE cells dead/live were detected by PI/Calcein-AM (red/green) after co-incubation with different concentration of Fe3O4/GO after 24 h (scale bar: 100 μm). (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of PI/Calcein-AM after co-incubation for 24 h.

Apoptosis detection was performed to verify the death mode of cells after incubation with Fe3O4/GO, which was characterized via Annexin-V/PI in Figure 9. After Fe3O4/GO exposure, fluorescence of Annexin-V and PI were obviously increased response to Fe3O4/GO nanoparticle concentration, which were concordant with the results of the cck-8 assay. It indicated high concentration Fe3O4/GO can lead to HBE cell apoptotic (Chen M. et al., 2021).

FIGURE 9. (A) HBE cells apoptosis were detected by Annexin-V/PI (green/red) after co-incubation with different concentration of Fe3O4/GO after 24 h (scale bar: 100 μm). (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of Annexin-V/PI (green/red) after co-incubation after 24 h.

So far, we have confirmed that Fe3O4/GO can stimulate HBE cells to produce oxidative stress, calcium influx, and mitochondrial superoxide, ultimately leading to apoptosis, and these phenomena are concentration-dependent. In order to explore the specific pathway through which Fe3O4/GO stimulates HBE cell genesis, we characterized the expression levels of Caspase-9 and Caspase-3.

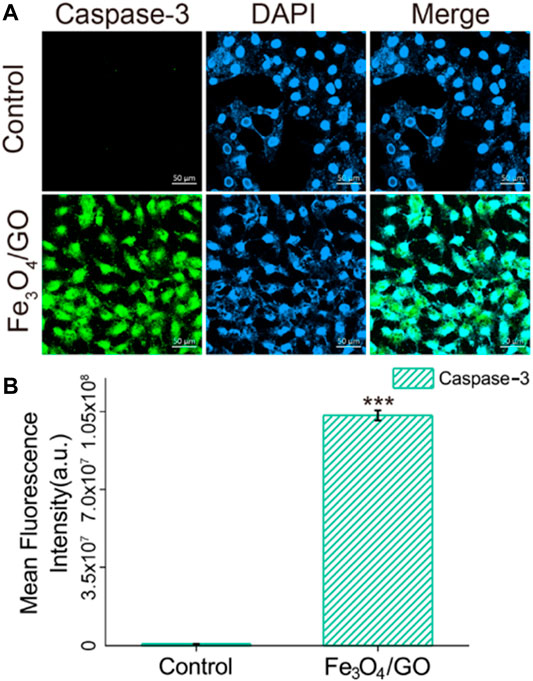

After coincubation with Fe3O4/GO, the fluorescence of Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 was significantly enhanced in Figures 10, 11, confirming that both Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 were activated. All these results indicated that Ca2+-ER stress led to mitochondrial dysfunction, which promoted the activation of Caspase-9 and activation of Caspase-3, resulted in cell apoptosis (Chen et al., 2005).

FIGURE 10. (A) Immunefluorescence of Caspase-9 after Fe3O4/GO exposure. (scale bar: 50 μm) (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of Caspase-9 after Fe3O4/GO nanoparticle exposure.

FIGURE 11. (A) Immunefluorescence of Caspase-3 after Fe3O4/GO exposure. (scale bar: 50 μm) (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of Caspase-3 after Fe3O4/GO exposure.

ROS are produced in cells via a variety of mechanisms. High intracellular ROS increased Ca2+ levels, which can trigger a series of mitochondrial related events, including endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, then activated Caspase-9/Caspase-3 relate apoptosis, these proteins are important in apoptotic pathway (Figure 12) (Hailan et al., 2022). Our study demonstrated that after HBE cells co-incubation with Fe3O4/GO, ROS levels increased and Ca2+ levels enhanced, lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, and then, resulting in Caspase-9/Caspase-3 related apoptotic of HBE cells.

In this study, the obtained results elaborated the cytotoxicity effects of Fe3O4/GO. Specifically, after exposure to high concentration of Fe3O4/GO nanomaterials, ROS levels and Ca2+ influx enhanced, and then, mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby leading to cell apoptosis via the Caspase-9/Caspase-3 pathway ultimately. The results also demonstrated that the cytotoxicity of Fe3O4/GO was in time-dependent and concentration-dependent manners. Therefore, it is still a challenging task in the future to transform Fe3O4/GO nanocomposites with cytotoxicity into biocompatible Fe3O4/GO nanocomposites.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conceptualization, LZ and YLZ. Methodology, YTZ and ZY. Software, YF. Validation, YLZ and YTZ. Formal analysis, YTZ and MZ. Investigation, MC. Writing—original draft preparation, YLZ.Writing—review and editing, LZ. Visualization, ZY and YF. Supervision, DZ. Project administration, LZ. Funding acquisition, LZ and BD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The work is financially funded by the National Special Fund for the Development of Major Research Equipment and Instrument (No. 2020YFF01014503), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021YFE0111300), and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No.19441904100, 22140900900).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.888033/full#supplementary-material

Ahamed, M., Akhtar, M. J., and Khan, M. A. M. (2020). Investigation of Cytotoxicity, Apoptosis, and Oxidative Stress Response of Fe3O4-RGO Nanocomposites in Human Liver HepG2 Cells. materials 13, 660. doi:10.3390/ma13030660

Chen, H, H., Xing, L., Guo, H., Luo, C., and Zhang, X. (2021). Dual-targeting SERS-Encoded Graphene Oxide Nanocarrier for Intracellular Co-delivery of Doxorubicin and 9-aminoacridine with Enhanced Combination Therapy. Analyst 146, 6893–6901. doi:10.1039/d1an01237a

Chen, M., Zhang, Y., Cui, L., Cao, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, W., et al. (2021). Protonated 2D Carbon Nitride Sensitized with Ce6 as a Smart Metal-free Nanoplatform for Boosted Acute Multimodal Photo-Sono Tumor Inactivation and Long-Term Cancer Immunotherapy. Chem. Eng. J. 422, 130089. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.130089

Chen, W., Yi, P., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Deng, Z., and Zhang, Z. (2011). Composites of Aminodextran-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Graphene Oxide for Cellular Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 3, 4085–4091. doi:10.1021/am2009647

Chen, X., Zhang, X., Kubo, H., Harris, D. M., Mills, G. D., Moyer, J., et al. (2005). Ca2+ Influx-Induced Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Overload Causes Mitochondrial-dependent Apoptosis in Ventricular Myocytes. Circ. Res. 97, 1009–1017. doi:10.1161/01.res.0000189270.72915.d1

Datta, D., Khatri, P., Singh, A., Saha, D. R., Verma, G., Raman, R., et al. (2018). Mycobacterium Fortuitum-Induced ER-Mitochondrial Calcium Dynamics Promotes Calpain/Caspase-12/Caspase-9 Mediated Apoptosis in Fish Macrophages. Cel Death Discov. 4, 30. doi:10.1038/s41420-018-0034-9

Dyer, T., Thamwattana, N., and Jalili, R. (2015). Modelling the Interaction of Graphene Oxide Using an Atomistic-Continuum Model. RSC. Adv. 5, 94. doi:10.1039/c5ra13353j

Fu, M., and Li, J. (2014). One-Pot Solvothermal Synthesis and Adsorption Property of Pb(II) of Superparamagnetic Monodisperse Fe3O4/Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite. Nanosci Nanotechnol Lett. 6, 1116–1122. doi:10.1166/nnl.2014.1927

García-Salvador, A., Katsumiti, A., Rojas, E., Aristimuño, C., Betanzos, M., Martínez-Moro, M., et al. (2021). A Complete In Vitro Toxicological Assessment of the Biological Effects of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: From Acute Toxicity to Multi-Dose Subchronic Cytotoxicity Study. Nanomaterials 11, 1577. doi:10.3390/nano11061577

Hailan, W. A., Al-Anazi, K. M., Farah, M. A., Ali, M. A., Al-Kawmani, A. A., and Abou-Tarboush, F. M. (2022). Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Cytotoxicity in Liver Carcinoma Cells Induced by Silver Nanoparticles Biosynthesized Using Schinus Molle Extract. Nanomaterials 12, 161. doi:10.3390/nano12010161

Hanh, N. T., Xuyen, N. T., and Thuy, T. T. T. (2018). Synthesis and Characterization of Fe3O4/GO Nanocomposite for Drug Carrier. Vjch 56, 642–646. doi:10.1002/vjch.201800063

Jedrzejczak-Silicka, M. (2017). Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of GO-Fe3O4 Hybrid in Cultured Mammalian Cells. Pol. J. Chem. Techno. 19, 27–33. doi:10.1515/pjct-2017-0004

Kaplan, A., Kutlu, H. M., and Ciftci, G. A. (2019). Fe3O4 Nanopowders: Genomic and Apoptotic Evaluations on A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cell Line. Nutr. Cancer 72, 708–721. doi:10.1080/01635581.2019.1643031

Karimi, S., and Namazi, H. (2021). Fe3O4@PEG-coated Dendrimer Modified Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite as a pH-Sensitive Drug Carrier for Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin. J. Alloys Compd. 879, 160426. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160426

Li, D., Deng, M., Yu, Z., Liu, W., Zhou, G., Li, W., et al. (2018). Biocompatible and Stable GO-Coated Fe3O4 Nanocomposite: A Robust Drug Delivery Carrier for Simultaneous Tumor MR Imaging and Targeted Therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 2143–2154. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00029

Metin, Ö., Aydoğan, Ş., and Meral, K. (2014). A New Route for the Synthesis of Graphene Oxide-Fe3O4 (GO-Fe3O4) Nanocomposites and Their Schottky Diode Applications. J. Alloys Compd. 585, 681–688. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.09.159

Narayanaswamy, V., and Srivastava, C. (2017). GO-Fe3O4 Nanoparticle Composite for Selective Targeting of Cancer Cells. Nano Biomed. Eng. 9, 96–102. doi:10.5101/nbe.v9i1.p96-102

Niu, Z., Murakonda, G. K., Jarubula, R., and Dai, M. (2021). Fabrication of Graphene Oxide-Fe3O4 Nanocomposites for Application in Bone Regeneration and Treatment of Leukemia. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 63, 102412. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102412

Qiang, S., Li, Z., Zhang, L., Luo, D., Geng, R., Zeng, X., et al. (2021). Cytotoxic Effect of Graphene Oxide Nanoribbons on Escherichia coli. Nanomaterials 11, 1339. doi:10.3390/nano11051339

Sadighian, S., Bayat, N., Najaflou, S., Kermanian, M., and Hamidi, M. (2021). Preparation of Graphene Oxide/Fe3O4 Nanocomposite as a Potential Magnetic Nanocarrier and MRI Contrast Agent. ChemistrySelect 6, 2862–2868. doi:10.1002/slct.202100195

Seyyed, M., Ahmad, G., Navid, O., Maryam, Z., Sonia, B., Khadije, Y., et al. (2021). Bioinorganic Synthesis of Polyrhodanine Stabilized Fe3O4/Graphene Oxide in Microbial Supernatant Media for Anticancer and Antibacterial Applications. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl., 9972664. doi:10.1155/2021/9972664

Tang, Z., Zhao, L., Yang, Z., Liu, Z., Gu, J., Bai, B., et al. (2018). Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Autophagy Involved in Graphene Oxide Nanomaterial Anti-osteosarcoma Effect. Ijn Vol. 13, 2907–2919. doi:10.2147/ijn.s159388

Valdiglesias, V. (2022). Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 12, 634. doi:10.3390/nano12040634

Vannozzi, L., Catalano, E., Telkhozhayeva, M., Teblum, E., Yarmolenko, A., Avraham, E. S., et al. (2021). Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanoflakes Coated with Glycol Chitosan, Propylene Glycol Alginate, and Polydopamine: Characterization and Cytotoxicity in Human Chondrocytes. Nanomaterials 11, 2105. doi:10.3390/nano11082105

Wang, C.-l., Liu, C., Niu, L.-l., Wang, L.-r., Hou, L.-h., and Cao, X.-h. (2013). Surfactin-Induced Apoptosis through ROS-ERS-Ca2+-ERK Pathways in HepG2 Cells. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 67, 1433–1439. doi:10.1007/s12013-013-9676-7

Wang, J., Fang, P., Li, X., Wu, S., Zhang, W., and Li, S. (2016). Preparation of Hollow Core Shell Fe3O4 Graphene Oxide Composites as Magnetic Targeting Drug Nanocarriers. J. Biomat. Sci. Polym. Edition 28, 37–349. doi:10.1080/09205063.2016.1268463

Wang, X., Chang, C. H., Jiang, J., Liu, X., Li, J., Liu, Q., et al. (2020). Mechanistic Differences in Cell Death Responses to Metal-Based Engineered Nanomaterials in Kupffer Cells and Hepatocytes. Small 16, e2000528. doi:10.1002/smll.202000528

Wen, C., Cheng, R., Gong, T., Huang, Y., Li, D., Zhao, X., et al. (2021). β-Cyclodextrin-cholic Acid-Hyaluronic Acid Polymer Coated Fe3O4-Graphene Oxide Nanohybrids as Local Chemo-Photothermal Synergistic Agents for Enhanced Liver Tumor Therapy. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 199, 111510. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111510

Wu, Q., Yu, R., Zhou, Z., Liu, H., and Jiang, R. (2021). Encapsulation of a Core-Shell Porous Fe3O4@Carbon Material with Reduced Graphene Oxide for Li+ Battery Anodes with Long Cyclability. Langmuir 37, 785–792. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c03126

Yan, F., Liu, Z., Zhang, T., Zhang, Q., Chen, Y., Xie, Y., et al. (2019). Biphasic Injectable Bone Cement with Fe3O4/GO Nanocomposites for the Minimally Invasive Treatment of Tumor-Induced Bone Destruction. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 5833–5843. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00472

Zakharova, O. V., Mastalygina, E. E., Golokhvast, K. S., and Gusev, A. A. (2021). Graphene Nanoribbons: Prospects of Application in Biomedicine and Toxicity. Nanomaterials 11, 2425. doi:10.3390/nano11092425

Zhang, H, H., Li, S., Liu, Y., Yu, Y., Lin, S., Wang, Q., et al. (2020). Fe3O4@GO Magnetic Nanocomposites Protect Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Promote Osteogenic Differentiation of Rat Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomater. Sci. 8, 5984–5993. doi:10.1039/d0bm00906g

Zhang, S., Wu, S., Shen, Y., Xiao, Y., Gao, L., and Shi, S. (2020). Cytotoxicity Studies of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles in Chicken Macrophage Cells. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191561. doi:10.1098/rsos.191561

Zhang, X., Cai, W., Hao, L., Feng, S., Lin, Q., and Jiang, W. (2017). Preparation of Fe3O4/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites with Good Dispersibility for Delivery of Paclitaxel. J. Nanomater. 2017, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2017/6702890

Zhang, Y., Han, L., Qi, W., Cheng, D., Ma, X., Hou, L., et al. (2015). Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Induced Apoptosis in HepG2 Cells through ROS-Ca2+-JNK Mitochondrial Pathways. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 456, 926–932. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.036

Zhang, Y., Kang, S., Lin, H., Chen, M., Li, Y., Cui, L., et al. (2022). Regulation of Zeolite-Derived Upconversion Photocatalytic System for Near Infrared Light/Ultrasound Dual-Triggered Multimodal Melanoma Therapy under a Boosted Hypoxia Relief Tumor Microenvironment via Autophagy. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132484. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132484

Zheng, L., Zhang, Y., Lin, H., Kang, S., Li, Y., Sun, D., et al. (2020). Ultrasound and Near-Infrared Light Dual-Triggered Upconversion Zeolite-Based Nanocomposite for Hyperthermia-Enhanced Multimodal Melanoma Therapy via a Precise Apoptotic Mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 12, 32420–32431. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c07297

Keywords: Fe3O4/GO nanosheets, cytotoxicity effects, oxidative stress, Ca2+ influx, apoptosis

Citation: Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Fan Y, Chen M, Zhao M, Dai B, Zheng L and Zhang D (2022) Cytotoxicity Effect of Iron Oxide (Fe3O4)/Graphene Oxide (GO) Nanosheets in Cultured HBE Cells. Front. Chem. 10:888033. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.888033

Received: 02 March 2022; Accepted: 31 March 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Chenghui Xia, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), FranceReviewed by:

Raviraj Vankayala, Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Zhang, Yang, Fan, Chen, Zhao, Dai, Zheng and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lulu Zheng, bGx6aGVuZ0B1c3N0LmVkdS5jbg==; Dawei Zhang, ZHd6aGFuZ0B1c3N0LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.