94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 04 January 2023

Sec. Electrochemistry

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.1104844

Cobalt (Co) as a substitute of noble-metal catalysts shows high catalytic capability for production of the widely used primary amines through the reductive amination. However, the synthesis of Co catalysts usually involves the introduction of organic compounds and the high-temperature pyrolysis, which is complicated and difficult for large-scale applications. Herein, we demonstrated a facile and efficient strategy for the preparation of Co catalysts through the in situ reconstruction of cobalt borate (CoBOx) during the reductive amination, delivering a high catalytic activity for production of benzylamine from benzaldehyde and ammonia. Initially, CoBOx was transformed into Co(OH)2 through the interaction with ammonia and subsequently reduced to Co nanoparticles by H2 under the reaction environments. The in situ generated Co catalysts exhibited a satisfactory activity and selectivity to the target product, which overmatched the commonly used Co/C, Pt or Raney Ni catalysts. We anticipate that such an in situ reconstruction of CoBOx by reactants during the reaction could provide a new approach for the design and optimization of catalysts to produce primary amines.

Primary amines are essential raw materials and intermediates in fine chemical industry, playing significant roles in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, biomolecules, advanced polymers, and agrochemicals (Kim et al., 2013; Cabrero-Antonino et al., 2019; Afanasyev et al., 2020; Irrgang and Kempe, 2020; Murugesan, et al., 2020). Various strategies have been investigated to synthesize primary amines, including reductive amination (Ball et al., 2018; Murugesan et al., 2019; Sukhorukov, 2020), aryl halides amination (Schranck and Tlili, 2018; Wang et al., 2022), nitriles hydrogenation (Garduño and García, 2020; Lévay and Hegedűs, 2018; Chen et al., 2016), olefins hydroamination (Miller et al., 2019; Sengupta et al., 2020), etc. Owing to the application of economical ammonia as well as the accessible reaction engineering, the reductive amination with usage of ammonia as the nitrogen resource represents one of the most cost-effective methods to manufacture primary amines. However, this process usually suffers from the selectivity challenge due to the side reactions including over hydrogenation of imines and reduction of carbonyl compounds to the corresponding alcohols (Chandra et al., 2018; Gallardo-Donaire et al., 2018). Thus, to design the appropriate catalyst to achieve selective production of primary amines through the reductive amination is highly desired.

Both traditional homogeneous metal complexes and heterogeneous catalysts have been successfully applied to produce primary amines through reductive amination, in which heterogeneous catalysts are more applicable in industrial field with the advantages of good durability, easy recycling and high potential for scale-up. Previously, noble metal-based catalysts (Pt, Pd, Ru, Rh, etc.) have exhibited satisfactory selectivity for target product (Dong et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2015; Chatterjee et al., 2016; Komanoya et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2020; Jv et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the high price of noble metals increases the production cost and limits the practical application. Consequently, the development of the non-noble metal-based heterogeneous catalysts is highly expected.

On account of the relatively high abundance and low price, Co has been employed as a reasonable non-noble metal-based catalysts in reductive amination among different substitutes for noble metals. As shown in Table 1, several heterogeneous Co-based catalysts were successfully reported (Jagadeesh et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2019; Senthamarai et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2022), including Co-DABCO-TPA@C-800, Co@NC-800, Co/mCN-900, etc. With Co nanoparticles as the active sites, these catalysts delivered satisfactory reactivity and realized the selective synthesis of benzylamine. Generally, the synthesis of the reported Co nanocatalysts was achieved through the thermal pyrolysis of various organometallic cobalt complexes. Although such synthetic method has been proved efficacious to prepare Co-based catalysts, the complicated operating procedures and high-temperature pyrolysis constrain its further application. Thus, an alternative method with the simplified procedure and mild condition is highly demanded.

Herein, we reported a facile method to prepare Co catalysts through the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx under the reductive amination environment, which delivered a high catalytic activity for the production of benzylamine between benzaldehyde and ammonia. In this method, the original CoBOx reacted with ammonia to yield surface Co(OH)2 initially, which was then reduced by hydrogen (H2) to form Co nanoparticles during the reductive amination. In comparison with the previously reported strategies to prepare Co catalysts, such reconstructed Co catalysts realized the in situ formation of Co active sites and avoided the introduction of organic complexes as well as the high-temperature pyrolysis, in accordance with the requirements for green chemistry. The in situ synthesized Co catalysts delivered high capability for the selective conversion of benzaldehyde and ammonia towards benzylamine (> 95%). This reconstruction synthetic method may provide a new approach for the design of non-noble metal-based heterogeneous catalysts for reductive amination.

Based on a previous work (Chen et al., 2016), the CoBOx nanosheets were synthesized through a facile and scalable wet chemistry method. Typically, 3 mmol of Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 7.5 mmol of NaBH4 were dissolved in 285 ml and 15 ml distilled water, respectively. Then, the freshly prepared aqueous NaBH4 solution was added into the Co(NO3)2 solution and the mixture was placed under the stirring of 800 rpm at room temperature for 1 h. After 2 h of aging, the solids were centrifuged off and washed by distilled water and ethanol alternatively for three times. Finally, the collected CoBOx was dried at 60°C for 12 h in a vacuum oven and then stored for future use.

C supports were synthesized from the nitric acid treatment of the commercial carbon black. The details could be found in a previous report (Zhang et al., 2022). To synthesize SiO2 supports, 300 mg of the commercial SiO2 was well dispersed in 50 ml of ethanol, then 100 μl of 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)-1-propanamine was added into the suspension. Next, the mixture was heated under 90°C for 4 h and washed by ethanol for three times. Finally, the prepared SiO2 was dried at 60°C for 24 h and stored in a vacuum oven.

The Pt/C catalysts were synthesized through an impregnation method. Firstly, 300 mg of the nitric acid-treated carbon black was well dispersed in 30 ml of distilled water by ultrasonication. Then, 0.75 ml of 2 mg ml−1 of Na2PtCl6·6H2O was added and the suspension was placed under the stirring of 800 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the mixture was heated at 80°C until the complete evaporation of the solution and the collected solid was treated under H2/Ar atmosphere at 300°C for 2 h. Finally, the Pt/C catalysts were dried in vacuum at 60°C for 12 h. The Pt/SiO2 catalysts were prepared through the similar procedure.

To synthesize Co/C catalysts, 300 mg of the nitric acid-treated carbon black was well dispersed in 30 ml of distilled water by ultrasonication. Then, 3 ml of 5 mg ml−1 Co(NO3)2·6H2O solution was added and the suspension was placed under the stirring of 800 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the mixture was heated at 80°C until the complete evaporation of the solution and the collected solid was treated under H2/Ar atmosphere at 300°C for 2 h with a heating rate of 5°C/min. Finally, the Co/C catalysts were dried and stored in a vacuum oven.

To synthesize Co(OH)2, 1.16 g of Co(NO3)2·6H2O and 19.2 g of NaOH were dissolved in 10 ml and 70 ml of distilled water, respectively. After 1 h of rigorous stirring, the two solutions were mixed and then transferred to a 100 ml of stainless autoclave. After 100°C of hydrothermal for 24 h, the solids were centrifuged off and washed by distilled water and ethanol alternatively for three times. Finally, the collected Co(OH)2 was dried at 60°C in a vacuum oven for 12 h and then stored for future use. For the synthesis of Co3O4, 300 mg of the as-synthesized CoBOx was calcinated at 500°C under air for 3 h, then the solids were collected and stored after cooling to room temperature.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were conducted on Hitachi HT-7700 with the accelerating voltage of 120 kV. High resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was performed on a JEOL JEM-F200 microscope with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were acquired from a Rigaku Powder X-ray diffractometer with the Cu Kα radiation, and X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were obtained on a Thermo Electron Model K-Alpha with Al Kα as the excitation sources.

The reductive amination of benzaldehyde and aqueous ammonia was carried out in a 30 ml of stainless autoclave. Initially, the CoBOx catalysts, benzaldehyde, ammonia and isopropanol with the desired amounts were mixed in the autoclave. Next, the stainless autoclave was pressurized with 2 MPa of H2, and the reaction temperature was raised to 80°C with a heating rate of 5°C/min. Finally, the reaction was processed under the stirring (600 rpm) at 80°C. When the reaction finished, the reaction mixture was centrifugated off and diluted with ethyl acetate. After the dehydration by anhydrous magnesium sulfate, the reaction products were analyzed by gas chromatography. The conversion of benzaldehyde (X) and the product selectivity (Si) were calculated by the following equations:

Where [Benzaldehyde]0 and [Benzaldehyde]t were the initial concentration and the residual concentration of benzaldehyde, respectively. [Product]i was the concentration of the product i in the residual mixture and Ni was the stoichiometric coefficient for product i with reference to benzaldehyde.

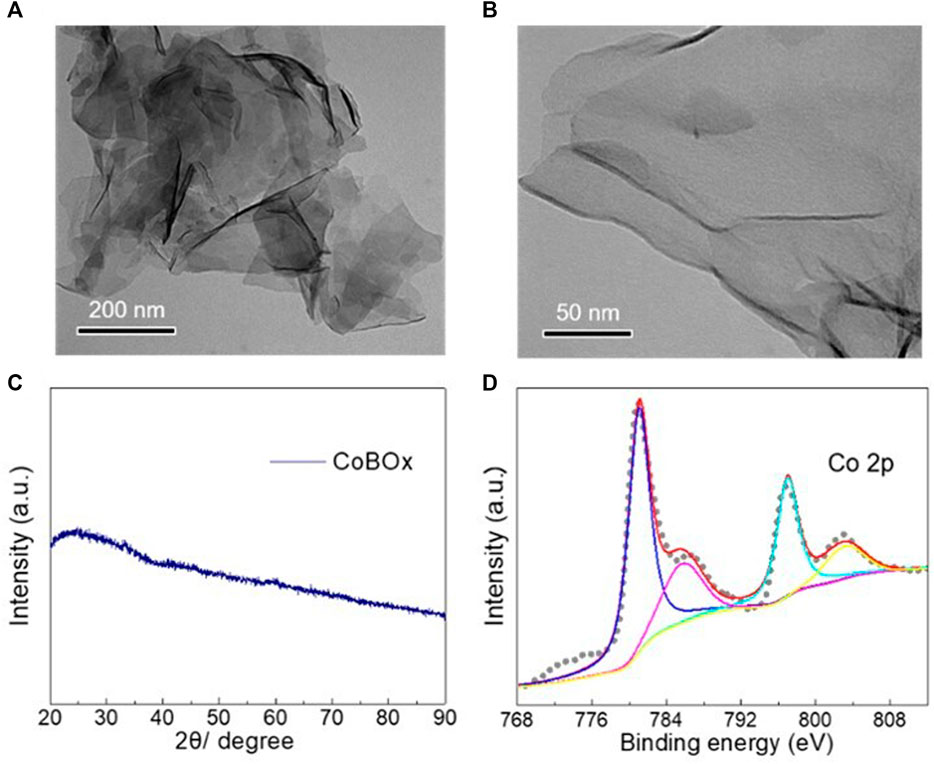

The morphology of the as-synthesized CoBOx catalysts was examined by the transmission electron microscopy. As shown in Figures 1A, B, the as-synthesized CoBOx nanomaterials exhibited a nanosheet morphology with the smooth surface. No XRD characteristic peaks were observed for the CoBOx nanosheets, indicating their amorphous feature (Figure 1C). Afterwards, the valence state of Co element in CoBOx catalysts was analyzed by XPS. As shown in Figure 1D, Co2+ primarily existed on the surface of CoBOx, indicated by the characteristic peaks at 780.9 eV and the presence of a satellite peak. Meanwhile, there was no apparent peak at approximate 778.0 eV, further confirming the absence of Co0 in the as-synthesized nanosheets.

FIGURE 1. Characterizations of the fresh CoBOx catalysts. (A,B) TEM images of the CoBOx nanosheets with different magnification times. (C) XRD pattern and (D) XPS spectrum of Co 2p of the CoBOx nanosheets.

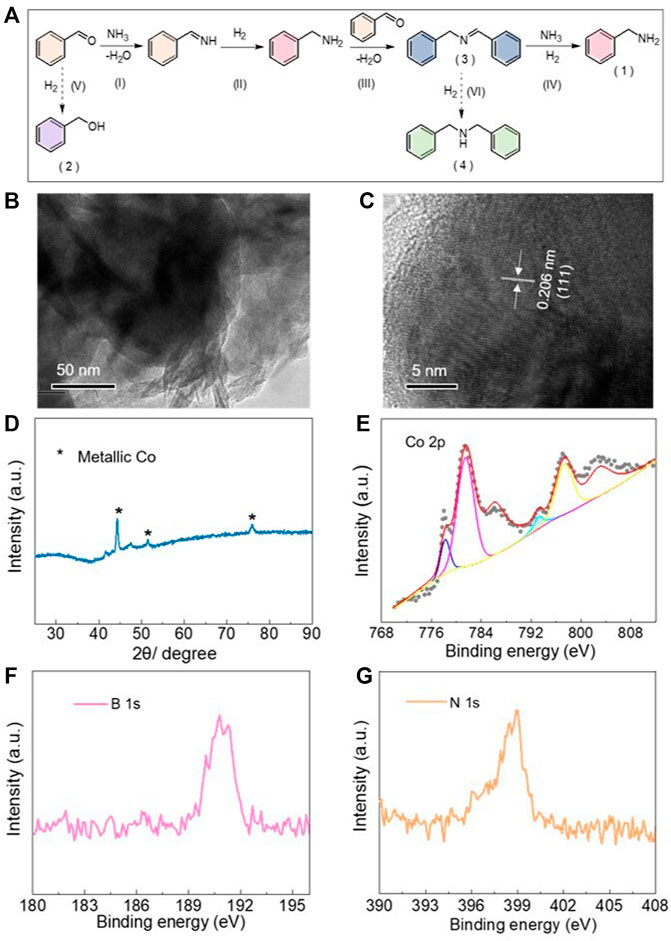

The reductive amination between benzaldehyde and aqueous ammonia (25 wt%–28 wt%) to produce benzylamine was applied to explore the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx as well as the catalytic performance. Generally, the following steps are included in the reductive amination of benzaldehyde and ammonia into benzylamine (Figure 2A): (I) the condensation between benzaldehyde and ammonia to generate benzylideneimine; (II) the reduction of benzylideneimine to benzylamine; (III) the condensation between the produced benzylamine and benzaldehyde to intermediate N-benzylidenebenzylamine; and (IV) the following reductive amination of N-benzylidenebenzylamine to target product benzylamine (product 1). Nevertheless, the side reactions of (V) the hydrogenation of benzaldehyde into benzyl alcohol (product 2) and (VI) the over-hydrogenation of N-benzylidenebenzylamine (product 3) into dibenzylamine (product 4) decrease the selectivity of the target product, limiting the practical application of this process.

FIGURE 2. (A) Possible reaction pathway for the reductive amination between benzaldehyde and ammonia. (B) TEM and (C) HRTEM images of the reconstructed CoBOx. (D) XRD pattern and (E) XPS spectrum of Co 2p of the treated CoBOx. (F) XPS spectrum of B 1s and (G) N 1s of the treated CoBOx.

Considering the cation exchange between Co2+ and NH4+ ions of ammonia and the existence of hydrogen in this reaction system, Co nanoparticles could be reconstructed on the surface of CoBOx in the presence of ammonia with a high concentration and H2. To further examine this possibility, the CoBOx nanosheets were mixed with ammonia, benzaldehyde, and isopropanol (IPA) under 80°C and 2 MPa of H2 for 15 h. Afterwards, the treated CoBOx was centrifuged off and characterized in comparison with the freshly prepared CoBOx. Different from the as-synthesized CoBOx with the light grey color and fluffy accumulation, the treated CoBOx was in black color with a needle-like appearance, which displayed a strong magnetic response (Supplementary Figure S1). Considering the strong magnetism of the metallic Co, the as-synthesized CoBOx might be in situ transformed into Co nanoparticles in the presence of ammonia and H2.

Afterwards, the treated CoBOx was analyzed by various characterizations. Derived from the dark field TEM and HRTEM (Figures 2B, C), the morphology of the treated CoBOx was totally distinguished from the as-synthesized CoBOx. The original nanosheet structure was obviously destructed. As shown in Figure 2C, the measured lattice fringe spacing of 0.206 nm was observed, which was consistent with that of Co (111) crystal plane, suggesting the existence of Co nanoparticles in the treated CoBOx. In addition, the formation of the Co nanoparticles was further revealed from its XRD pattern. As shown in Figure 2D, the XRD pattern of the treated CoBOx was in accordance with that of metallic Co (PDF 15–0806), in which a sharp peak could be found around 44.5°, and other small peaks was approximate in 51.6° and 76.1°, respectively. Besides, small peaks at around 41.7° and 47.8° could be attributed to the formation of Co2B. To further prove the existence of the Co0, XPS measurements were also employed. As shown in XPS spectrum of Co 2p (Figure 2E), the characteristic peak at 778.1 eV and the peak at 780.9 eV as well as satellite peak indicated the co-existence of Co0 and Co2+ in the reconstructed catalysts. The derived fraction of Co0 was only 14.7%, which could be attributed to the residual CoBOx as well as the oxidation of cobalt upon the exposure of catalysts in air during the measurements. In addition, apparent peaks observed on B 1s and N 1s spectrum revealed the presence of B and N along with the generation of Co nanoparticles (Figures 2F, G). The XPS results were in accordance with that of TEM and XRD tests, suggesting the successful in situ generation of Co nanoparticles. As expected, the original CoBOx nanosheets could react with ammonia under H2 atmosphere during the reductive amination of benzaldehyde and ammonia.

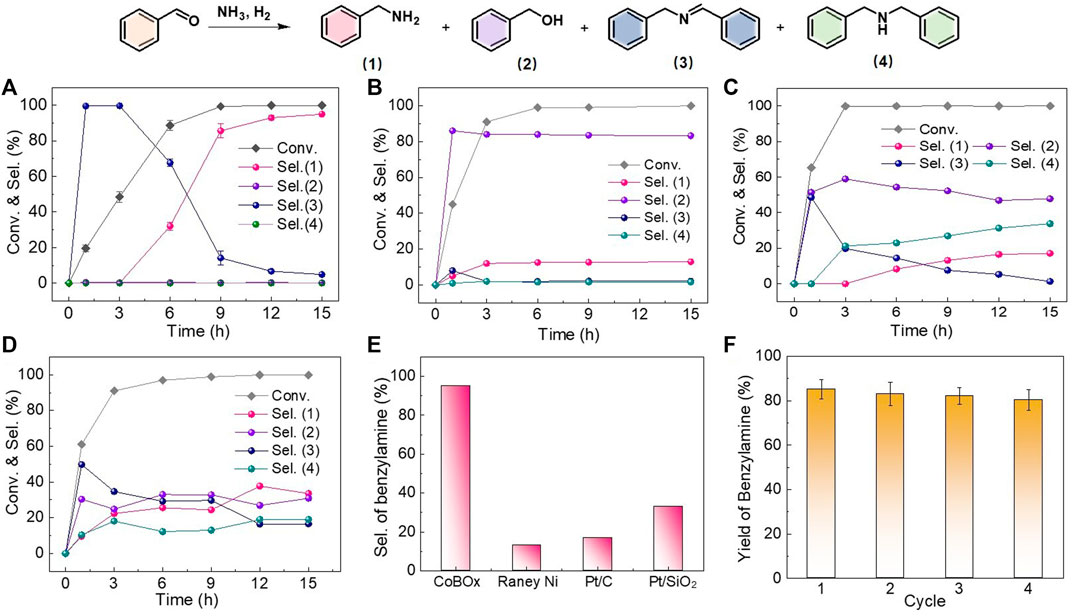

Then, the catalytic performance of the reconstructed Co nanoparticles was performed for the reductive amination between benzaldehyde and ammonia. After the optimization of solvent (Supplementary Figure S2), the reaction was conducted in isopropanol under 2 MPa of H2 and 80°C. Meanwhile, the catalytic performance of the Raney Ni, Pt/C, and Pt/SiO2 as the controlled catalysts was also examined. When the reconstructed CoBOx was used as the catalysts (Figure 3A), benzaldehyde was converted to intermediate N-benzylidenebenzylamine at the initial 3 h (Step I-III), and further hydrogenated to the target benzylamine as reaction proceeded (Step IV). Finally, the conversion of benzaldehyde reached to > 99% with a selectivity of benzylamine of 95.2% at 15 h. Except for the intermediate N-benzylidenebenzylamine and the target product benzylamine, by products of benzyl alcohol and dibenzylamine were not detected, indicating the high reactivity and chemoselectivity of the reconstructed CoBOx catalysts. In contrast, the main product appeared to be benzyl alcohol on Raney Ni. The selectivity of benzylamine was only 12.1% after the 15 h, indicating that the Step V was predominant on Raney Ni (Figure 3B). On Pt-based catalysts, by products of benzyl alcohol and dibenzylamine were both detected, indicating the occurrence of the Step V and Step VI. The selectivity of benzylamine on Pt/C and Pt/SiO2 were 17.1% and 33.6%, respectively (Figures 3C, D). According to the experimental results, the Co nanoparticles generated from the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx could effectively inhibit the side reactions of benzaldehyde direct hydrogenation and N-benzylidenebenzylamine over hydrogenation, avoiding the production of by-products and exhibiting a superior selectivity towards benzylamine in the reductive amination between benzaldehyde and ammonia. As shown in Figure 3E, the selectivity of benzylamine on CoBOx was 7.9, 5.6, and 2.8 times of that on Raney Ni, Pt/C and Pt/SiO2, respectively.

FIGURE 3. Catalytic performance of (A) CoBOx, (B) Raney Ni, (C) Pt/C and (D) Pt/SiO2 catalysts. (E) Comparison on the selectivity of benzylamine at the end of the reaction. (F) Cycling test of CoBOx catalysts. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol benzaldehyde, 80°C, 2 MPa H2, 4 ml IPA, 20 mg CoBOx, or 20 mg 0.5 wt% Pt/C, 20 mg 0.5 wt% Pt/SiO2, or 5 mg Raney Ni catalysts. The error bars in (A,F) were calculated based on three trials.

Afterwards, the stability of the in situ formed Co nanoparticles was examined by cycling test. Due to the strong magnetism, the used catalysts could be easily separated from the reaction mixture by a magnet. Without other treatments, the collected catalysts were applied for the next cycle on the identical reaction conditions. As shown in Figure 3F, the reaction time was controlled as 9 h and the catalysts could be reused at least four cycles with the yields of benzylamine maintained over 80%, suggesting the good catalytic stability of the in situ formed Co nanoparticles. Meanwhile, the reaction mixture was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES), and Co was not detected. The slight reduction of the yield of benzylamine might be resulted from the catalyst loss during the cycling test.

Based on the characterizations and the experimental results, it could be confirmed that CoBOx could react with ammonia and H2 under the reductive amination environments, resulting in the formation of Co nanoparticles through the in situ reconstruction. Moreover, the Co nanoparticles efficiently suppressed the side reactions and realized the selective production of benzylamine. In order to clarify the active sites on the reconstructed CoBOx, various Co-based catalysts were prepared. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, Co3O4 and Co(OH)2 were synthesized by the calcination of CoBOx and the hydrothermal of Co(NO3)2·6H2O, respectively (Supplementary Figures S3, S4). The yield of benzylamine was below 1% when catalyzed by either Co3O4 or Co(OH)2. Thus, the metallic Co should play a significant role in the production of benzylamine. Afterwards, the Co/C catalysts were prepared and employed in this reaction, presenting an obvious lower yield of benzylamine (40.0%) compared with the in situ generated Co nanoparticles. As a result, the high selectivity of re-constructed CoBOx was not only attributed to the formation of metallic Co, but also the in situ catalytic environment.

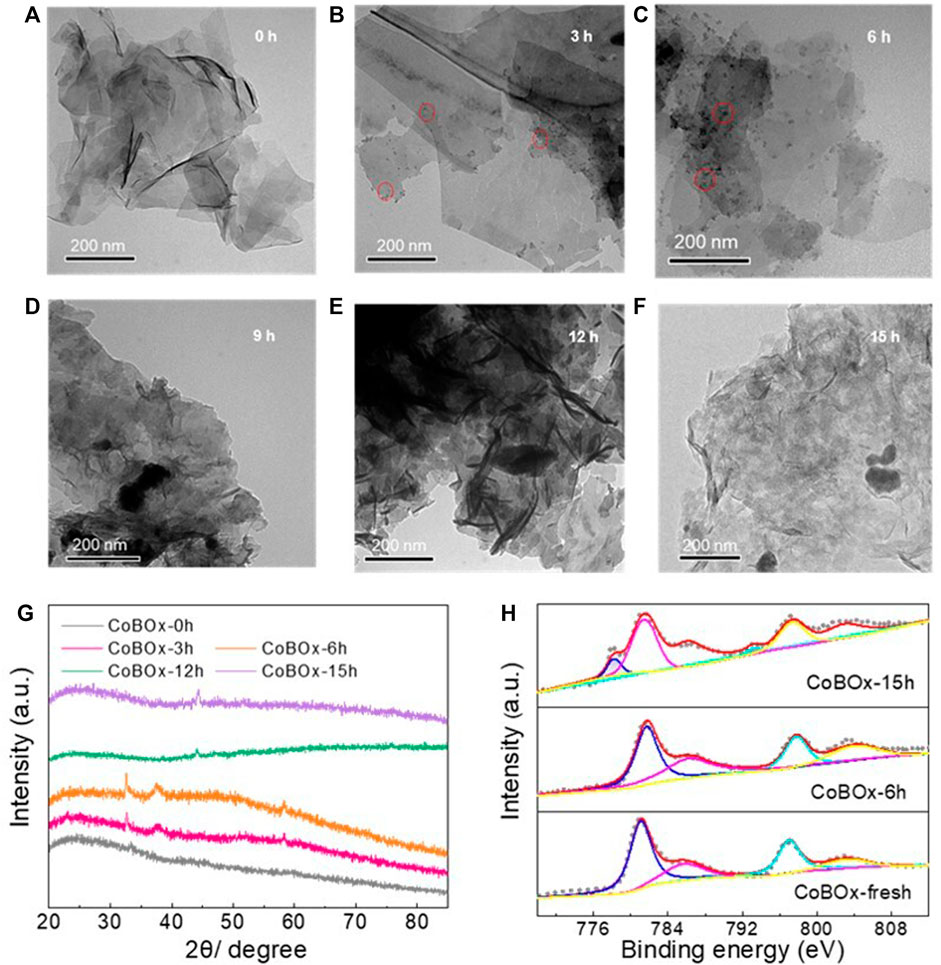

Afterwards, the reconstruction pathway of CoBOx was explored. The reconstruction of CoBOx should be a dynamic process, including the reduction of Co2+ to Co0 and the crystallization of metallic Co. To further investigate the dynamic change of CoBOx during the reductive amination between benzaldehyde and ammonia, the catalysts were collected after the 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, and 15 h reaction, respectively, which are named by CoBOx-3 h, CoBOx-6 h, CoBOx-9 h, CoBOx-12 h, CoBOx-15 h. After the thoroughly washing and vacuum drying, these catalysts were analyzed. According to TEM images, it could be observed that nanoparticles were formed on the surface of CoBOx during the reaction and they aggregated and grew up as reaction proceeded (Figures 4B, C). To further demonstrate the reconstruction of CoBOx, XRD and XPS tests were performed on the various CoBOx catalysts. According to Figure 4G, the peaks at 32.6°, 38.1°, and 58.2° were observed on CoBOx-3 h and CoBOx-6 h, which was in consistent with the characteristic peaks of Co(OH)2 (PDF no. 51–1731), indicating the formation of Co(OH)2 from CoBOx during the first 6 h of the reaction. As the reaction continued, the characteristic peaks of Co(OH)2 disappeared, and the typical peaks of metallic Co were observed, indicating the reduction of Co(OH)2 to Co nanoparticles. Moreover, the XPS analysis exhibited the similar phenomenon, in which Co0 peaks couldn’t be found on the original CoBOx and CoBOx-6 h, but existed in CoBOx-15 h (Figure 4H).

FIGURE 4. TEM images of (A) CoBOx-fresh, (B) CoBOx-3 h, (C) CoBOx-6 h, (D) CoBOx-9 h, (E) CoBOx-12 h, (F) CoBOx-15 h (G) XRD pattern and (H) XPS spectrum of Co 2p of different CoBOx catalysts.

Integrating the results of TEM, XRD, and XPS, the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx might be summarized into the following steps: 1) Given the high concentration of ammonia (∼4.5 mmol/ml) in the reaction system, NH4+ and OH− could be easily formed through ionization and separately reacted with CoBOx (Eq. 1). Consequently, Co2+ in CoBOx could be substituted by NH4+ and then interacted with OH−, resulting in the formation of Co(OH)2 (Eqs 2, 3). 2) Under H2 atmosphere, Co(OH)2 was finally reduced to Co nanoparticles (Eq. 4). The chemical formulas of CoBOx reconstruction process are shown below:

As discussed above, the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx follows the order of CoBOx→Co(OH)2→Co nanoparticles, with which benzaldehyde is selectively transformed to the target product benzylamine. The whole reconstruction process is demonstrated in Scheme 1. According to Scheme 1, ammonia and H2 play significant roles in the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx. To further investigate the influences of ammonia volume and H2 pressure, the CoBOx nanosheets were treated under different volume of ammonia and pressure of H2. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, only when the volume of ammonia > 2 ml and the pressure of H2 > 2 MPa could the CoBOx be in situ reconstructed. Thus, adequate ammonia volume and H2 pressure are necessary for the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx. Besides, NaOH was also applied to replace ammonia, it turned out that Co nanoparticles were not formed, further confirming the indispensability of ammonia.

In this work, we reported the formation of Co nanoparticles through the in situ reconstruction of CoBOx during the reductive amination of benzaldehyde and ammonia, which delivered a high catalytic performance for the synthesis of benzylamine from benzaldehyde and ammonia. In the presence of ammonia and H2, the cation exchange between Co2+ and NH4+ leads to the formation of Co(OH)2 on CoBOx, which was subsequently reduced to Co nanoparticles. The in situ generated Co nanoparticles could suppress the side reactions and realize the selective reductive amination to give primary amine. The selectivity of benzylamine was 95.2% catalyzed by the reconstructed CoBOx, which was obvious higher than Raney Ni, Pt/C or Pt/SiO2 catalysts. Such an in situ reconstruction strategy provided a new approach for the synthesis of the highly performed metallic Co for production of primary amines.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

MZ designed and conducted the experiments, and wrote the original draft. SZ conducted investigations and edited the manuscript. YM conceptualized the work and edited the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (D5000210283, D5000210601, and D5000210829) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (21872109 and 22002115). SZ was also supported by the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2019QNRC001) and the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 22038011).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.1104844/full#supplementary-material

Afanasyev, O. I., Kuchuk, E., Usanov, D. L., and Chusov, D. (2020). Reductive amination in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 119, 11857–11911. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00383

Ball, M. R., Wesley, T. S., Rivera-dones, K. R., Huber, G. W., and Dumesic, J. A. (2018). Amination of 1-hexanol on bimetallic AuPd/TiO2 catalysts. Green Chem. 20, 4695–4709. doi:10.1039/C8GC02321B

Cabrero-Antonino, J. R., Adam, R., and Beller, M. (2019). Reductive N-alkylations using CO2 and carboxylic acid derivatives: Recent progress and developments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 12820–12838. doi:10.1002/anie.201810121

Chandra, D., Inoue, Y., Sasase, M., Kitano, M., Bhaumik, A., Kamata, K., et al. (2018). A high performance catalyst of shape-specific ruthenium nanoparticles for production of primary amines by reductive amination of carbonyl compounds. Chem. Sci. 9, 5949–5956. doi:10.1039/C8SC01197D

Chatterjee, M., Ishizaka, T., and Kawanami, H. (2016). Reductive amination of furfural to furfurylamine using aqueous ammonia solution and molecular hydrogen: An environmentally friendly approach. Green Chem. 18, 487–496. doi:10.1039/C5GC01352F

Chen, F., Topf, C. Radnik J., Kreyenschulte, C., Lund, H., Schneider, M., Surkus, A. -E., et al. (2016a). Stable and inert cobalt catalysts for highly selective and practical hydrogenation of C≡N and C═O bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8781–8788. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b03439

Chen, P., Xu, K., Zhou, T., Tong, Y., Wu, J., Cheng, H., et al. (2016b). Strong-coupled cobalt borate nanosheets/graphene hybrid as electrocatalyst for water oxidation under both alkaline and neutral conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2488–2492. doi:10.1002/anie.201511032

Dong, B., Guo, X. C., Zhang, B., Chen, X., Guan, J., Qi, Y., et al. (2015). Heterogeneous Ru-based catalysts for one-pot synthesis of primary amines from aldehydes and ammonia. Catalysts 5, 2258–2270. doi:10.3390/catal5042258

Dong, C., Wang, H., Du, H., Peng, J., Cai, Y., Guo, S., et al. (2020). Ru/HZSM-5 as an efficient and recyclable catalyst for reductive amination of furfural to furfurylamine. Mol. Catal. 482, 110755. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2019.110755

Gallardo-Donaire, J., Hermsen, M., Wysocki, J., Ernst, M., Rominger, F., Trapp, O., et al. (2018). Direct asymmetric ruthenium-catalyzed reductive amination of alkyl−aryl ketones with ammonia and hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 355–361. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b10496

Garduño, J. A., and García, J. J. (2020). Toward amines, imines, and imidazoles: A viewpoint on the 3d transition-metal-catalyzed homogeneous hydrogenation of nitriles. ACS Catal 10, 8012–8022. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c02283

Guo, W., Tong, T., Liu, X., Guo, Y., and Wang, Y. (2019). Morphology-tuned activity of Ru/Nb2O5 catalysts for ketone reductive amination. ChemCatChem 11, 4130–4138. doi:10.1002/cctc.201900335

Irrgang, T., and Kempe, R. (2020). Transition-metal-catalyzed reductive amination employing hydrogen. Chem. Rev. 120, 9583–9674. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00248

Jagadeesh, R. V., Murugesan, K., Alshammari, A. S., Neumann, H., Pohl, M.-M., Jörg Radnik, J., et al. (2017). MOF-derived cobalt nanoparticles catalyze a general synthesis of amines. Science 358, 326–332. doi:10.1126/science.aan6245

Jv, X., Sun, S., Zhang, Q., Du, M., Wang, L., and Wang, Bo. (2020). Efficient and mild reductive amination of carbonyl compounds catalyzed by dual-function palladium nanoparticles. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 1618–1626. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06464

Kim, J., Kim, H. J., and Chang, S. (2013). Synthetic uses of ammonia in transition-metal catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 16, 3201–3213. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300164

Komanoya, T., Kinemura, T., Kita, Y., Kamata, K., and Hara, M. (2017). Electronic effect of ruthenium nanoparticles on efficient reductive amination of carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11493–11499. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04481

Lévay, K., and Hegedűs, L. (2018). Selective heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of nitriles to primary amines. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 62, 476–488. doi:10.3311/PPch.12787

Liang, G., Wang, A., Li, L., Xu, G., Yan, N., and Zhang, T. (2017). Production of primary amines by reductive amination of biomass-derived aldehydes/ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3050–3054. doi:10.1002/anie.201610964

Liu, J., Guo, W., Sun, H., Li, R., Feng, Z., Zhou, X., et al. (2019). Reductive amination of carbonyl compounds with ammonia and hydrogenation of nitriles to primary amines with heterogeneous cobalt catalysts. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 35, 457–462. doi:10.1007/s40242-019-8390-4

Ma, Z., Zhou, B., Li, X., Kadam, R. G., Gawande, M. B., Petr, M., et al. (2022). Reusable Co-nanoparticles for general and selective N-alkylation of amines and ammonia with alcohols. Chem. Sci. 13, 111–117. doi:10.1039/d1sc05913k

Miller, D. C., Ganley, J. M., Musacchio, A. J., Sherwood, T. C., Ewing, W. R., and Knowles, R. R. (2019). Anti-markovnikov hydroamination of unactivated alkenes with primary alkyl amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16590–16594. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b08746

Murugesan, K., Beller, M., and Jagadeesh, R. V. (2019). Reusable nickel nanoparticles-catalyzed reductive amination for selective synthesis of primary amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5064–5068. doi:10.1002/anie.201812100

Murugesan, K., Senthamarai, T., Chandrashekhar, V. G., Natte, K., Kamer, P. C. J., Beller, M., et al. (2020). Catalytic reductive aminations using molecular hydrogen for synthesis of different kinds of amines. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6273–6328. doi:10.1039/C9CS00286C

Nakamura, Y., Kon, K., Touchy, A. S., Shimizu, K., and Ueda, W. (2015). Selective synthesis of primary amines by reductive amination of ketones with ammonia over supported Pt catalysts. ChemCatChem 7, 921–924. doi:10.1002/cctc.201402996

Qi, H., Yang, J., Liu, F., Zhang, L., Yang, J., Liu, X., et al. (2021). Highly selective and robust single-atom catalyst Ru1/NC for reductive amination of aldehydes/ketones. Nat. Commun. 12, 3295. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23429-w

Schranck, J., and Tlili, A. (2018). Transition-metal-catalyzed monoarylation of ammonia. ACS Catal. 8, 405–418. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b03215

Sengupta, M., Das, S., Islam, S. M., and Bordoloi, A. (2020). Heterogeneously catalysed hydroamination. ChemCatChem 13, 1089–1104. doi:10.1002/cctc.202001394

Senthamarai, T., Chandrashekhar, V. G., Gawande, M. B., Kalevaru, N. V., Zboril, R., Kamer, P. C. J., et al. (2020). Ultra-small cobalt nanoparticles from molecularly-defined Co-salen complexes for catalytic synthesis of amines. Chem. Sci. 11, 2973–2981. doi:10.1039/c9sc04963k

Sukhorukov, A. Y. (2020). Catalytic reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones with nitro compounds: New light on an old reaction. Front. Chem. 8, 215. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00215

Wang, H., Zheng, Y., Xu, H., Zou, J., Jin, C., J, A., et al. (2022). Metal-free synthesis of N-heterocycles via intramolecular electrochemical C-H aminationsToward amines, imines, and imidazoles: A viewpoint on the 3d transition-metal-catalyzed homogeneous hydrogenation of nitriles. Front. Chem.ACS Catal. 1010, 9506358012–9506358022. doi:10.3389/fchem.2022.950635arduño10.1021/acscatal.0c02283

Yuan, Z., Liu, B., Zhou, P., Zhang, Z., and Chi, Q. (2019). Preparation of nitrogen-doped carbon supported cobalt catalysts and its application in the reductive amination. J. Catal. 370, 347–356. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2019.01.004

Keywords: heterogeneous catalysis, reductive amination, primary amine, in-situ reconstruction, cobalt

Citation: Zhang M, Zhang S and Ma Y (2023) In-situ reconstruction of CoBOx enables formation of Co for synthesis of benzylamine through reductive amination. Front. Chem. 10:1104844. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.1104844

Received: 22 November 2022; Accepted: 14 December 2022;

Published: 04 January 2023.

Edited by:

Xifei Li, Xi’an University of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Zhang, Zhang and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sai Zhang, emhhbmdzYWkxMTEyQG53cHUuZWR1LmNu; Yuanyuan Ma, eXltYUBud3B1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.