- 1School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China

- 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China

In the past years, metal halide perovskite (MHP) single crystals have become promising candidates for optoelectronic devices since they possess better optical and charge transport properties than their polycrystalline counterparts. Despite these advantages, traditional bulk growth methods do not lend MHP single crystals to device integration as readily as their polycrystalline analogues. Perovskite nanocrystals (NCs), nanometer-scale perovskite single crystals capped with surfactant molecules and dispersed in non-polar solution, are widely investigated in solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), because of the direct bandgap, tunable bandgaps, long charge diffusion length, and high carrier mobility, as well as solution-processed film fabrication and convenient substrate integration. In this review, we summarize recent developments in the optoelectronic application of perovskite nanocrystal, including solar cells, LEDs, and lasers. We highlight strategies for optimizing the device performance. This review aims to guide the future design of perovskite nanocrystals for various optoelectronic applications.

Introduction

Metal halide perovskite materials have drawn great attention for optoelectronic applications due to their superior electrical properties (Chen et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2018). They are a class of materials with a formula of ABX3 in which A is a monovalent cation, B is a divalent metal ion, and X is a halide anion (Chen et al., 2019a). The outstanding optical and electrical properties of metal halide perovskites include high absorption coefficient, high carrier mobility, long carrier lifetime, long carrier diffusion length, and high defect tolerance (Wang et al., 2017). After only 10-year development, the efficiency of perovskite solar cells has rocketed from 3.8% to 25.5%, showing great potential for commercial application (Feng et al., 2020). Besides, metal halide perovskite materials are also widely investigated in other optoelectronic devices, such as sensitive photodetectors and x-ray detectors, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) (Chen et al., 2019b; Sun et al., 2020).

Polycrystalline thin films and single crystals are two forms of metal halide perovskite materials for optoelectronic application. The former contains large amounts of grain boundaries that are rich in charge traps, causing adverse effect on the optoelectronic properties, and stability of the perovskite materials (Lin et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). In comparison, perovskite single crystals are free of grain boundaries and are demonstrated with lower defect density, better optoelectronic properties, and higher stability than the polycrystalline thin films (Jiang et al., 2020a). Dong et al. observed the ultra-low trap state density of 1010 cm−3 and ultra-long charge carrier diffusion lengths of 175 μm under one Sun illumination in methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) single crystals (Dong et al., 2015). Chen et al. reported that mixed cation and mixed halide perovskite single crystals remained stable even after 10,000 h water-oxygen and 1,000 h light aging (Chen et al., 2019a). In fact, it is universally recognized that perovskite single crystals are intriguing for higher-performance and more stable optoelectronic devices (Cheng et al., 2020).

The morphology control is a key factor determining the optoelectronic application of perovskite single crystals (Bao et al., 2017). Millimeter- or centimeter-sized perovskite bulk single crystals are ideal candidates for high-energy radiation detection due to the large thickness and existence of heavy atom (Wu et al., 2021). However, their large thickness leads to ineffective carrier collection and thus low external quantum efficiency (EQE) of solar cells. Besides, the challenges of integration with substrates and low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) also limits application of bulk single crystals (Jiang et al., 2019). In this case, single crystal thin films (SCTF), micro single crystals, single crystal wire/plate, and single crystal quantum dots are developed for high-performance solar cells, photodetectors, lasers, and LEDs, respectively (Shao et al., 2017). For example, the efficiency of single crystal solar cells reaches 21.1% when using SCTF with a thickness of 20 um, which is competitive with the perovskite polycrystalline solar cells (Chen et al., 2019c).

Perovskite nanocrystals (NCs), nanometer-scale perovskite single crystals capped with surfactant molecules and dispersed in non-polar solution (Wang et al., 2021), are promising for optoelectronic applications, such as solar cells, LEDs, lasers, scintillation (Wang et al., 2019), and solar concentrators (Liu et al., 2021), due to their convenient deposition on conductive substrates based on solution-based processes (Zhao et al., 2019a; Zeng et al., 2019). Significant research efforts have been achieved for passivating defects in perovskite NCs, pushing the performance of perovskite NC-based optoelectronic devices better and better. In this manuscript, we summarize progress in perovskite NC solar cells, light-emitting diodes, and lasers, as well as challenges and possible solutions.

Perovskite NC Solar Cells

The large crystal thickness hinders application of perovskite bulk single crystals in photovoltaic application. Recently, space-confined strategy has been widely used to grow perovskite single-crystal thin films and efficient solar cells are achieved (Chen et al., 2019c). In this method, the lateral size of the single-crystal thin films is only several millimeters, leading to small-sized solar cells. In contrast, perovskite NCs can be processed by spin-coating, blade-coating to achieve large-area devices, which can satisfy the requirement of commercial application.

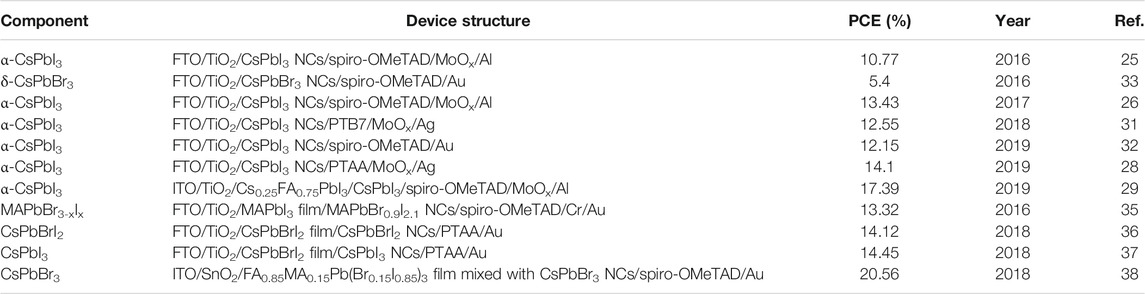

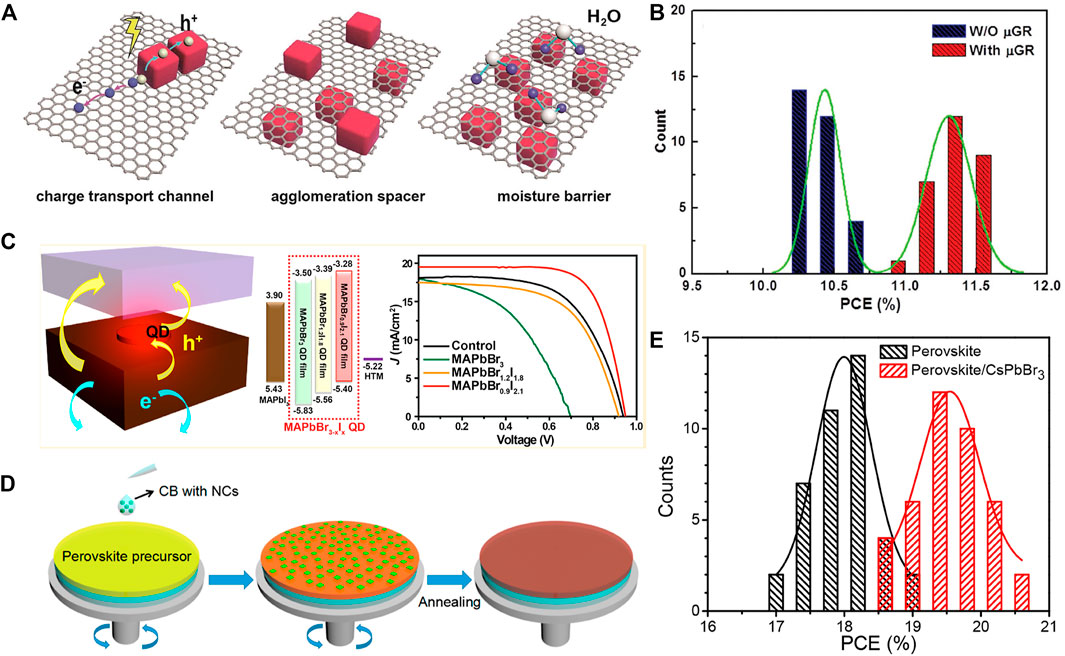

The first perovskite NC solar cells belong to the “dye-sensitized” type, and the MAPbI3 and MAPbBr3 NCs were employed as the sensitizer (Figure 1A). The NCs were prepared using a templated-based approach, with 2–3 nm in diameter (Figure 1B), yielding a PCE of 3.8% (Kojima et al., 2009). Several years later, the device performance increased to 6.54% through surface modification of the TiO2 electron transport layer (ETL) and post-anneal of the devices (Im et al., 2011). Later, the liquid electrolyte was replaced with a solid hole transport layer (HTL), the spiro-OMeTAD film, to enhance the device stability (Figures 1C,D). Sensitized meso-TiO2 devices showing PCEs of 8% and 9.7% (Figures 1E,F) were achieved using MAPbI3 and MAPbI2Cl NCs, respectively (Kim et al., 2012). Through replacing the meso-TiO2 with meso-Al2O3, the device PCE further improved to 10.9% (Lee et al., 2012). The Al2O3 is a large bandgap semiconductor, which is inefficient for electron extraction (Figure 1C), revealing that the perovskites can also act as a charge-transporting material (Sum and Mathews, 2014). To better control over the perovskite NC growth over mesoporous metal oxide, a sequential deposition method was introduced by Gratzel and coworkers (Burschka et al., 2013). Limited PbI2 NCs around 22 nm were deposited over a nanoporous TiO2 at the first step (Figure 1D), then transformed into perovskite NCs through exposing to a MAI solution (Figure 1E). This method offers much controllable device morphology than previously reported and led to a much improved PCE of 15% (Figure 1F).

FIGURE 1. (A) Crystal structures of perovskite compounds. (B) SEM image of particles of nanocrystalline CH3NH3PbBr3 deposited on the TiO2 surface. The arrow indicates a particle, and the scale bar shows 10 nm. Reproduced with permission (Wang et al., 2019). Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. (C) Cross-sectional SEM image of the device. (D) Active layer–underlayer–FTO interfacial junction structure. (E) Photocurrent density as a function of the forward bias voltage. (F) EQE as a function of incident wavelength. Reproduced with permission (Zeng et al., 2019). Copyright 2012, Springer Nature.

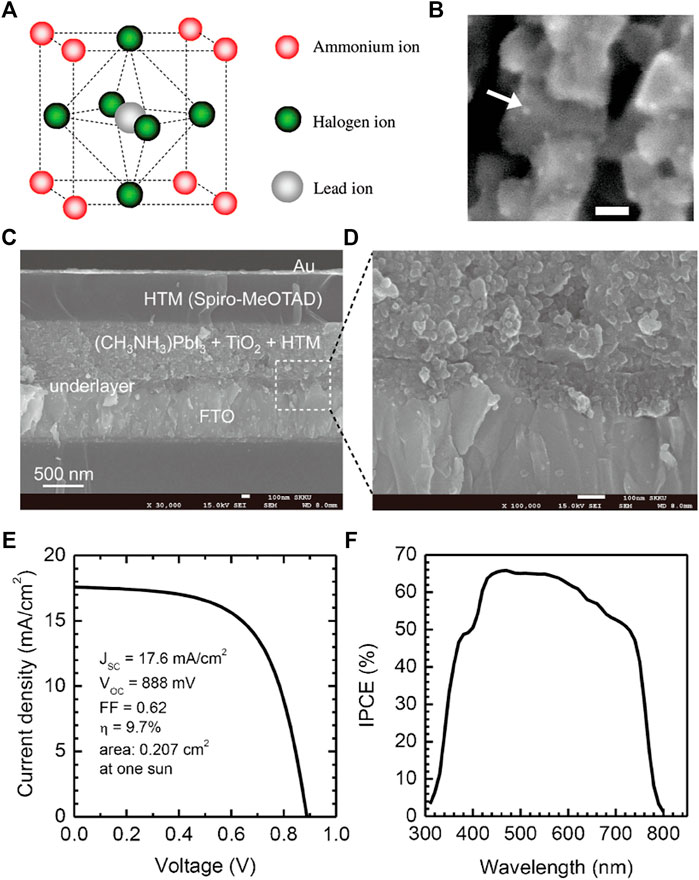

The size distribution and crystal surface of template-synthesized perovskite NCs, which is the basis of device performance, are difficult to control. To overcome this, solution-chemistry synthesis methods were employed to produce high-quality perovskite NCs through ligand control. Luther et al. synthesized 9-nm α-CsPbI3 NCs using the hot-injection method (Swarnkar et al., 2016), and purified the NCs using methyl acetate (MeOAc) as an antisolvent to remove surface ligands without inducing agglomeration or defect states. A planer device structure was employed. The best-performing device, employing CsPbI3 NCs with an Eg of 1.73 eV, showed 10.77% PCE for a device made and tested under ambient conditions. The maximum device VOC has reached ∼85% of the NC bandgap, but the JSC is limited, which mainly suffers from the high electric resistance due to the presence of capping ligands. In order to overcome this limitation, Luther and coworkers post-treated the NC film using a cation halide (AX) salt, which has greatly enhanced the charge carrier mobility (Sanehira et al., 2017). With the help of FAI post-treatments, the device JSC was greatly enhanced; thus, a high PCE of 13.4% was achieved. Luther’s group went further into the FAI treatment chemistry by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry in a subsequent study (Wheeler et al., 2018). They demonstrated that initial FAI treatments lead to strong coupling across the thickness of the film, but there also exists a concentration gradient that transforms the film into a FA-rich bulk phase by extended treatment time (Figures 2A,B), providing basic rules for fabrication of high-quality, electronically coupled perovskite NC films that maintain quantum confinement. After that, Ma and coworkers developed a cesium acetate post-treatment method for CsPbI3 NCs to fill the NC surface vacancy and improve electron coupling between NCs. As a result, the carrier lifetime, diffusion length, and mobility of the CsPbI3 NC film were improved, delivering an impressive efficiency of 14.01% for CsPbI3 NC cells (Figures 2C,D) (Ling et al., 2019). The cesium acetate-treated CsPbI3 NC devices exhibit improved stability against moisture due to the improved NC surface environment. Very recently, Luther and coworkers demonstrated that optimizing the heterojunction position as well as the composition will greatly change the device performance, and they have successfully enhanced the PCE of CsPbI3 NC solar cells to a high value of 17.39% by introducing the charge separating heterostructure (Zhao et al., 2019b).

FIGURE 2. (A) A cartoon of surface composition showing CsPbI3 films that were treated with MeOAc and then with solutions of FAI in EtOAc for 3, 10, 30, and 90 s. (B) Current density–voltage with stabilized power output shown as square markers. Reproduced with permission (Sum and Mathews, 2014). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (C) J–V curves of the best cells without (control) and with CsAc post-treatment and PCE distribution histograms (inserted) of 32 control and CsAc-treated cells, measured under reverse scan. (D) EQE curves and integrated J of the best cells. Reproduced with permission (Burschka et al., 2013). Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH.

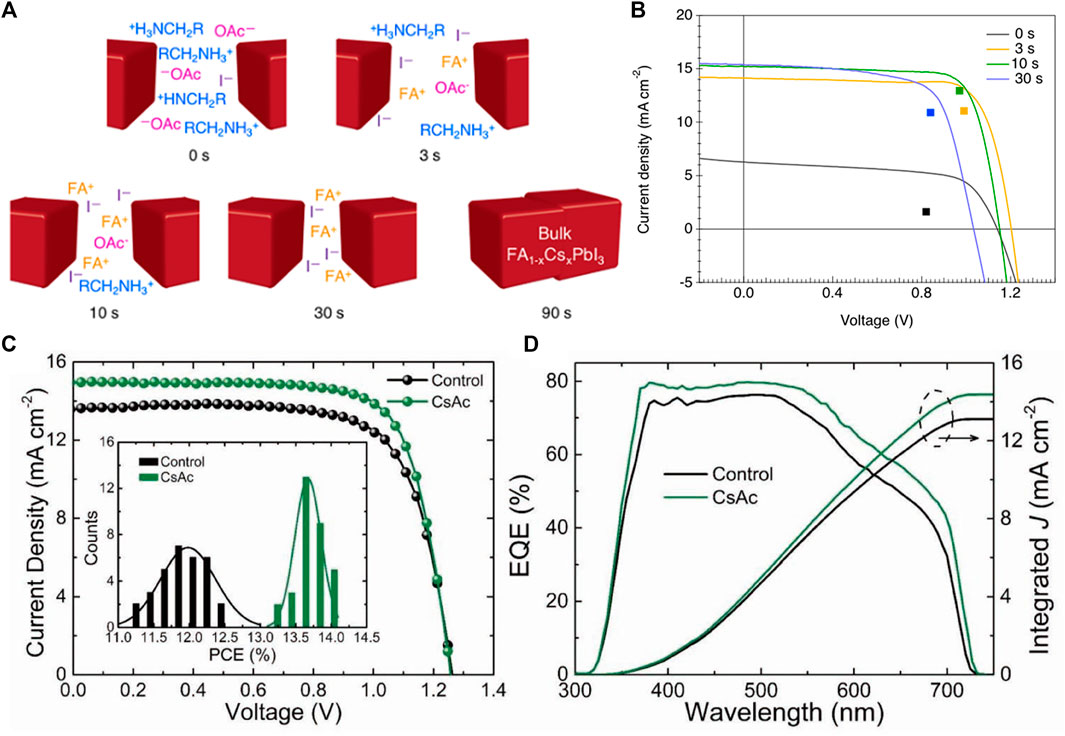

At the same time, other strategies have also been developed to improve the electronic coupling. The charge carrier transport properties of CsPbI3 NC films were greatly enhanced by using μ-graphene to cross-link CsPbI3 NCs (Wang et al., 2018), increasing the device PCE to 11.4%, together with enhanced moisture and thermal stabilities (Figures 3A,B). Yuan et al. employed a dopant-free polymeric (PTB7) as the hole transport materials, realizing a loss energy loss (0.45 V) and thus a high PCE of 12.55% (Yuan et al., 2018). Liu and coworkers prepared highly stable CsPbI3 NCs with the assistance of GeI2 and achieved stable devices (85% retained of the initial performance after storage for 90 days) with a PCE of 12.15% (Liu et al., 2019). There are also attempts to commercialize; for that, CsPbBr3 NC inks have been prepared through replacing the bulky organic ligands by short low-boiling-point ligands during synthesis (Akkerman et al., 2016). Films from the CsPbBr3 NC inks showed high conductivity, which is benefiting from the short capping ligands, and the corresponding cells exhibited a decent PCE of 5.4% and good stability.

FIGURE 3. (A) Schematic drawing of the charge transport process and stabilization mechanism for the µGR/CsPbI3 NC-based solar cells. (B) Comparison of the PCE distribution for the CsPbI3 and µGR/CsPbI3 devices. Reproduced with permission (Sanehira et al., 2017). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (C) Schematic illustration, Energy diagram, and J–V curves of devices employing MAPb(BrI)3 NCs as the interface-regulating material. Reproduced with permission (Yuan et al., 2018). Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (D) Schematic diagram of the deposition method for the perovskite film with CsPbBr3 NCs; the green dots represent CsPbBr3 NCs. (E) Histogram of solar cell efficiencies for 40 devices fabricated without and with 2 mg/ml CsPbBr3 NCs in the dripping solvent. Reproduced with permission (Chen et al., 2015a). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Benefiting from the easily tuned bandgap, the perovskite NCs have been used as interface materials to optimize the interfacial band alignment of solution-processed solar cells (Chen et al., 2015a). For example, MAPb(BrI)3 NCs have been chosen to engineer the interface between MAPbI3 films and HTLs. The energy levels of MAPb(BrI)3 NCs were adjusted by changing the Br:I ratios, and with the help of MAPbBr0.9I2.1 NC films, the device performance has been enhanced by 29% (Figure 3C), suggesting that the hole extraction was improved (Cha et al., 2016). All inorganic perovskite NCs with better thermal stability have also been employed as interface materials (Zhang et al., 2018a). For example, Bian and co-workers used an assembled film with CsPbI3 NCs to optimize the energy-level alignment for better carrier collection. The authors developed multiple strategies including Mn2+ doping, FAI treatment, and thiocyanate capping to the perovskite NCs, resulting in reduced trap states, enhanced carrier mobility, and improved chemical stability, and thus higher device PCE (Bian et al., 2018). Recently, Zai et al. used CsPbBr3 NC solution as the antisolvent to prepare FAMAPb(I0.85Br0.15)3 films, resulting in reduced carrier recombination process and more favorable energy alignment, which boosted the device PCE to 20.56% (Figures 3D,E) (Zai et al., 2018). We summarized the component of perovskite NCs employed and corresponded device structures and performances in Table 1.

Since charge carrier transport, which is determined by the carrier mobilities and carrier lifetime, determines the solar cell performance (Chen et al., 2013a), it is crucial to prepare high-quality active layers with low trap density towards high PCEs (Yao et al., 2015). Being different from the bulk perovskites, charge carrier transport mechanisms in perovskite NC films include resonant energy transfer, variable range hopping, and tunneling between adjacent NCs (Chen et al., 2015b). Carrier transport through all these mechanisms can be enhanced by reducing the inter-nanocrystal distance, which means that exchanging long original ligands to short ligands or removing the surface ligands will lead to high-quality perovskite NC films with excellent carrier transport performance. To date, the perovskite NC film thicknesses in best-performing cells are approximately 200 nm, which is thinner than that (∼500 nm) in bulk film devices, indicating that the photocurrent of NC cells can become higher through increasing the active layer thickness while ensuring efficient carrier transport. Thus, efforts should be paid on developing new methods towards efficient ligand exchange and ligand removing. Besides, beyond the single-junction photovoltaics, combining perovskite NC cells with other type of devices to form tandem solar cells may also be promising.

Perovskite NC LEDs

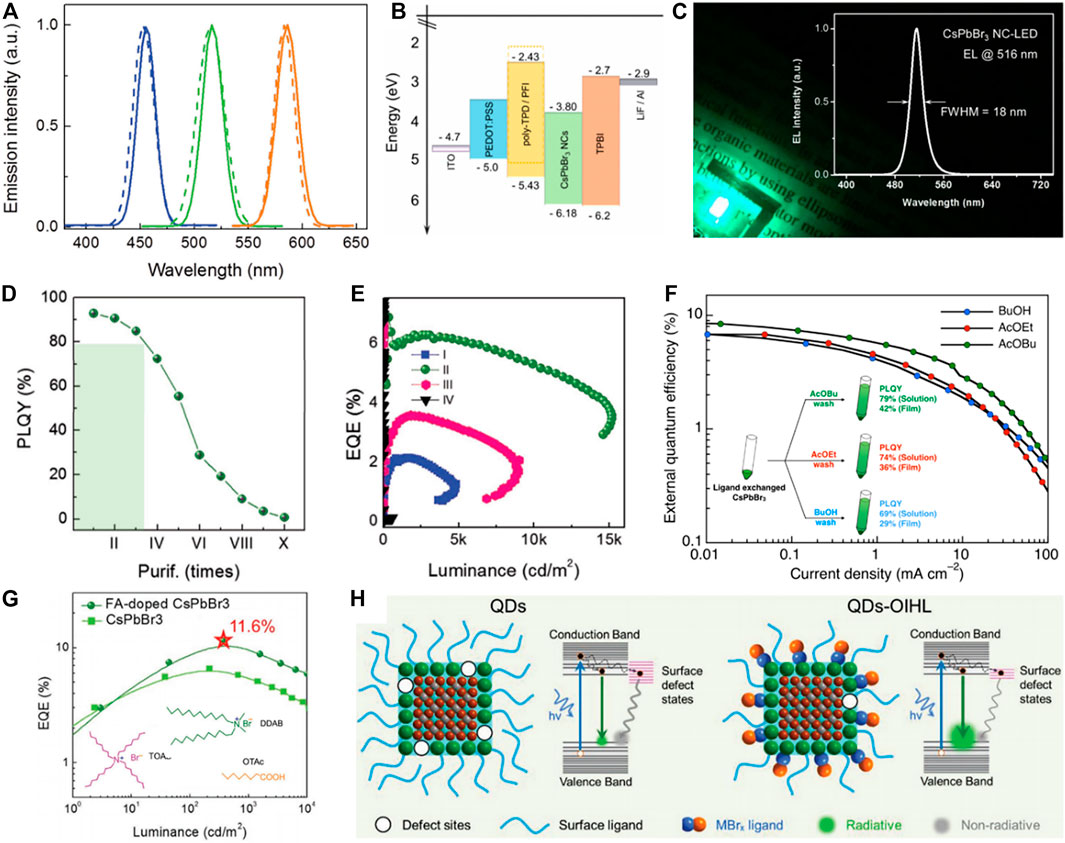

Room-temperature electroluminescence (EL) of perovskite NC LEDs was first demonstrated by Prieto and coworkers in 2014. Free MAPbBr3 NCs with a quantum yield (QY) of 20% were used as the emitters, and only low brightness and poor device performance were reported. The brightness of perovskite NC-based LEDs was improved by Zeng and coworkers by employing bright CsPbBr3 NCs (PL QY over 85%) as the emitters, which reaches 946 cd m−2 under the voltage of 8.8 V. Blue and red LEDs with mixed halogen component perovskite NCs have also been shown (Figure 4A) (Song et al., 2015). Later, Zhang et al. enhanced the hole injection efficiency by introducing a thin film of perfluorinated ionomer (PFI) sandwiched between the hole transporting layer and the CsPbBr3 emitting layer (Figure 4B), which led to a narrow EL emission at 516 nm with FWHM = 18 nm and a peak brightness of 1,377 cd m−2 (Figure 4C) (Zhang et al., 2016a). Those initial works highlighting the promise of perovskite NCs for applications in light emission (Sutherland and Sargent, 2016).

FIGURE 4. (A) The EL spectra (straight line) of red-, green-, and blue-perovskite NC LEDs, and the PL spectra (dashed line) of NCs dispersed in hexane. Reproduced with permission (Zai et al., 2018). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (B) Overall energy band diagram of the LED structure. The hole injection becomes more efficient after introducing the PFI. (C) A photo of a bright CsPbBr3 NC LED, with its narrow EL spectrum as inset. Reproduced with permission (Chen et al., 2013a). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (D) PL QY of CsPbBr3 NC inks with different purifying cycles dispersed in hexane. (E) EQE as a function of luminance of devices with different purifying cycles. Reproduced with permission (Song et al., 2015). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (F) EQE as a function of current density of devices employing NCs that use different washing process with BuOH, AcOEt, and AcOBu, respectively. Reproduced with permission (Zhang et al., 2016a). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (G) EQE of the devices as a function of luminance. Inset shows the surface ligands employed. Reproduced with permission (Sutherland and Sargent, 2016). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (H) Schematic description of radiative and nonradiative recombination of NCs. Reproduced with permission (Zhang et al., 2016b). Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH.

Then, the performances of CsPbBr3 NC LEDs entered a rapid development stage. Through using dual-phase CsPbBr3-CsPb2Br5 composites, Sun and coworkers reduced exciton diffusion length and decreased the trap density of perovskite NC films, which led to an enhanced EQE of 2.21% (Zhang et al., 2016b). Later, Zeng and coworkers developed a ligand density control method to balance the surface passivation and carrier injection (Figure 4D), and an EQE of 6.27% was obtained for the CsPbBr3 LEDs (Figure 4E) (Li et al., 2017a). Kido and coworkers employed a similar method, that is, to wash the CsPbBr3 NCs several times with butyl acetate, to remove excess ligands from the NCs (Chiba et al., 2017). Their NC-LED exhibited a maximum EQE of 8.73% (Figure 4F), revealing the important role of the NC surface towards high device performance. The EQE of CsPbBr3 NC-LEDs increased to 11.6% through FA cation doping and employing a group of short surface ligands including TOAB (tetraoctylammonium bromide), DDAB (didodecyldimethylammonium bromide), and OTAc (octanoic acid) (Figure 4G) (Song et al., 2018a). To further passivate perovskite NCs and improve electrical transportation properties of NC films, Zeng and coworkers developed a general organic–inorganic hybrid ligand strategy (Figure 4H), which has led to a maximum peak EQE of 16.48%, the highest value for green NC-based LEDs to date (Song et al., 2018b).

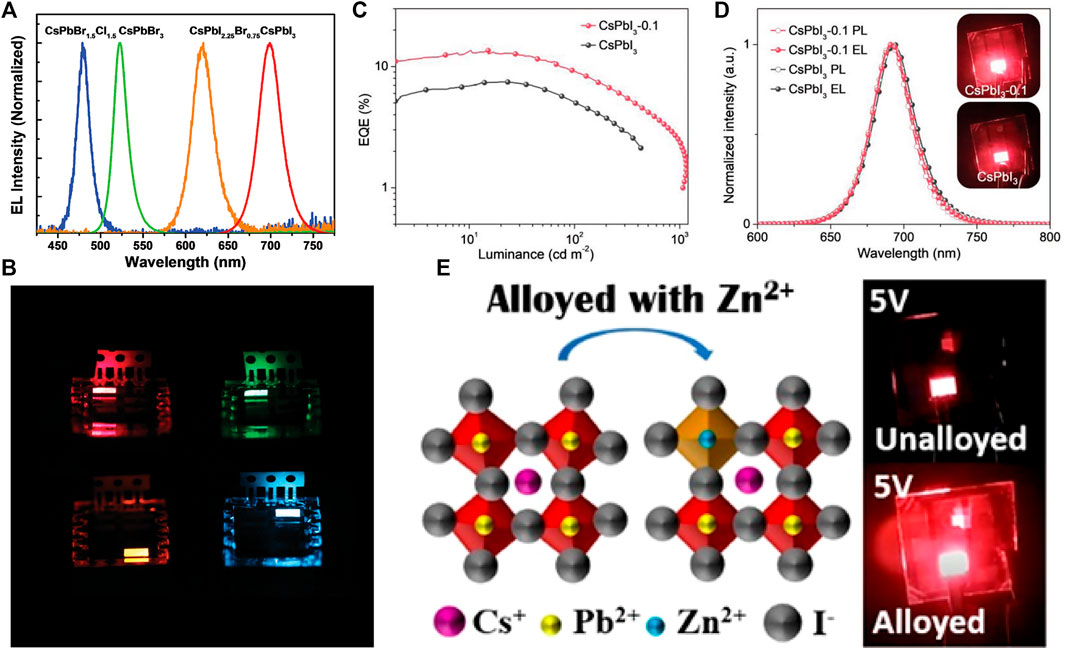

Compared to NC LEDs based on the bromine components, efficient iodine-based perovskite NC LEDs are more difficult to obtain because of the unstable nature of the iodine-based NC materials. Initial studies of CsPbI3 NC LEDs were focused on their device performances. Through a trimethylkaluminum (TMA) vapor-based cross-linking method, the electron-hole capture ability of the compact CsPbI3 NC film was enhanced, giving rise to high-performance red LEDs with a peak EQE of 5.7% (Figures 5A,B) (Li et al., 2016). Later, Zhang et al. demonstrated that through a simple post treatment to the CsPbI3 NCs with polyethylenimine (PEI), the NC surface defects could be well passivated, leading to a remarkable EL efficiency of 7.25% (Zhang et al., 2016c). After that, the researchers began to think over the device stability as well. Pan et al. passivated CsPbI3 NCs using a bidentate ligand 2,2′-iminodibenzoic acid (IDA), and obtained bright NCs with improved stability. Although the performance of IDA passivated LEDs was lower than previously reported values, the corresponded device stability was enhanced (Pan et al., 2018). Soon after that, both the performance and the stability of CsPbI3 NC LEDs were greatly enhanced by using PbS to cap the CsPbI3 NCs. Zhang et al. developed a strategy to simultaneously enhance the optical properties and stability of CsPbI3 NCs without damaging the semiconducting properties, which is realized by epitaxial growth of PbS semiconductor on the surface of CsPbI3 NCs. With PbS capping, the CsPbI3 NC film switched from n-type behavior to nearly ambipolar, allowing to fabricate LEDs using p-i-n structures. The thus-fabricated LEDs showed enhanced storage and operation stability, and an EQE of 11.8% (Zhang et al., 2018b). To make the LEDs more stable and efficient, Lu et al. developed a method to improve both the PL and the EL efficiency through using SrCl2 as a co-precursor when synthesizing CsPbI3 NCs (Figures 5C,D). As a result, NCs with simultaneous Sr doping and Cl surface passivation were obtained, and devices using these emitters showed enhanced stability and a high EQE of 13.5% (Lu et al., 2018). Soon after that, the device EQE was further improved to 15.1% through using Zn-alloyed CsPbI3 NCs as the emitters (Figure 5E) (Shen et al., 2019). The most efficient and stable NCs have the component of CsPb0.64Zn0.36I3.

FIGURE 5. (A) Electroluminescence spectra of red-, orange-, green-, and blue-emitting perovskite nanocrystal LEDs. (B) Images of perovskite nanocrystal LEDs in operation. Reproduced with permission (Li et al., 2017a). Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH. (C) External quantum efficiency versus luminance of the same devices. (D) PL and EL spectra of the CsPbI3 and CsPbI3-0.1 NC-based LED; inset shows photographs of the two devices. Reproduced with permission (Li et al., 2016). Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (E) Schematic diagram of the Zn2+ doping for the CsPbI3 NCs and the light from the respective working devices. Reproduced with permission (Zhang et al., 2016c). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Except for NC LEDs based on those pure Br or I component NCs, devices that employ mixed halogen perovskite NCs have also been studied. Mixed halogen NCs offer more choices on the emitting color, which is promising in high-purity color display. We summarized some representative results of perovskite NC LEDs in Table 2. To date, the most efficient perovskite NC LEDs that exhibited an EQE of 21.3% are based on CsPb(Br/I)3 NCs, which is obtained through anion exchange between CsPbBr3 NCs and ammonium iodine salts (Chiba et al., 2018).

Perovskite NC Lasers

Lasers are devices that can emit light through an optical amplification process, which takes advantage of the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation (Yakunin et al., 2015). Perovskite NCs offer bright tunable emission and are flexibly afforded by colloidal synthesis, ensuring that they are promising for laser applications. Sun and coworkers employed CsPbX3 NCs (PL from 470 to 620 nm) with sizes of approximately 10 nm to fabricate thin films and demonstrated room-temperature amplification of spontaneous emission in the visible spectral range. The PL peak position changed with pump intensities, and the PL spectra become narrower (FWHM = 5 nm) when the pump intensity was increased (Wang et al., 2015). The threshold was reduced to as low as 5 μJ cm−2 (400 nm at 100 fs) by using whispering-gallery-mode (WGM) lasing in which CsPbX3 NCs were coated onto silica spheres. The laser possessed high modal net gain values of at least 450 ± 30 cm−161. Xu et al. demonstrated that CsPbBr3 NCs can excite large optical gain (>500 cm−1) in thin films, and the clear stable two-photon pumped lasing for CsPbBr3 NCs doped in microtubule resonators has a threshold of 0.8 mJ cm−2 (Xu et al., 2016). Li et al. fabricated bright perovskite NC-SiO2 composite films by anchoring NCs onto silica nanospheres, which show random lasing with thresholds down to 40 μJ cm−2 (400 nm at 100 fs) (Li et al., 2017b). These examples reveal the strong nonlinear properties in the emerging perovskite NCs and suggest that CsPbX3 lasers hold promise for future nonlinear photonic devices.

Challenges and Perspective

The past years have witnessed great development of optoelectronic devices based on perovskite NCs; however, the most recent development is relatively sluggish. To provide instructive guidelines for future development, the challenges in this research field are discussed and possible solutions are proposed.

1) The PLQY of perovskite NCs films is usually smaller than solution, a general problem for any kind of NCs (Zhou et al., 2011), which should be increased to improve the EQE of LEDs. The decrease of PLQY may be due to the aggregation of perovskite NCs in solid state. To overcome this problem, construction of core-shell structures may be promising towards highly emissive solid-state perovskite NCs (Chen et al., 2014).

2) The electronic coupling between adjacent NCs are vital for carrier transport for both NCs solar cells and LEDs (Chen et al., 2013b). The existence of long-chain surfactant can passivate the surface dangling bond, but is adverse for carrier transport. Therefore, developing advanced ligand exchange strategy is required to ensure effective carrier transport and defect passivation. Learning from PbS NCs solar cells, bidentate ligand containing N, S atoms can interact with adjacent NCs and may solve this key challenges.

3) The toxic lead ions of halide perovskite materials are harmful for researchers and environment. Lots of advanced encapsulation techniques have been developed to avoid leakage of lead ions. In comparison, developing lead-free perovskite materials can overcome this problem basically. Up to now, a lot of lead-free perovskite materials have been developed, such as Bi-, Cu-, and Mn-based perovskites (Jiang et al., 2020b). Nevertheless, their material properties and corresponding device performance still cannot compete with the lead halide perovskites. To reduce the toxicity of perovskite materials, exploring novel lead-free perovskite materials should be further pursued. In this case, high-throughput computational screening and density functional theory can be combined to discover new perovskites with superior properties.

4) Doping is an effective way to modify perovskite polycrystalline thin films; however, doping perovskite NCs is relatively sluggish. Moreover, although doping in perovskite NCs have been demonstrated to improve emission properties, their application in LED devices should be explored. Guided by theoretical calculation, more rational, and effective doping will be raised to improve the properties of perovskite NCs and the EQE of LEDs.

5) In comparison to green, red, and yellow emission, blue-light perovskite NCs are relatively rare and the PLQY is smaller, leading to blue LEDs with low EQE. To overcome this point, effective B-site doping should be conducted in CsPbCl3 NCs, which may solve the bottleneck of blue-emission devices. Meanwhile, some B-site ions, such as Mn doping, can lead to broad emission due to existence of self-trapped excitons, which demonstrate the potential of applications in white-light applications.

Author Contributions

JH and XX wrote the article.

Funding

This work was economically supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52002221). University Scientific Research Project of Anhui Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. KJ2020A0709).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akkerman, Q. A., Gandini, M., Di Stasio, F., Rastogi, P., Palazon, F., Bertoni, G., et al. (2016). Strongly Emissive Perovskite Nanocrystal Inks for High-Voltage Solar Cells. Nat. Energ. 2, 16194. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.194

Bao, C., Chen, Z., Fang, Y., Wei, H., Deng, Y., Xiao, X., et al. (2017). Low‐Noise and Large‐Linear‐Dynamic‐Range Photodetectors Based on Hybrid‐Perovskite Thin‐Single‐Crystals. Adv. Mater. 29, 1703209. doi:10.1002/adma.201703209

Bian, H., Bai, D., Jin, Z., Wang, K., Liang, L., Wang, H., et al. (2018). Graded Bandgap CsPbI2+xBr1−x Perovskite Solar Cells with a Stabilized Efficiency of 14.4%. Joule 2, 1500–1510. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.04.012

Burschka, J., Pellet, N., Moon, S.-J., Humphry-Baker, R., Gao, P., Nazeeruddin, M. K., et al. (2013). Sequential Deposition as a Route to High-Performance Perovskite-Sensitized Solar Cells. Nature 499, 316–319. doi:10.1038/nature12340

Cha, M., Da, P., Wang, J., Wang, W., Chen, Z., Xiu, F., et al. (2016). Enhancing Perovskite Solar Cell Performance by Interface Engineering Using CH3NH3PbBr0.9I2.1 Quantum Dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8581–8587. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b04519

Chen, L., Tan, Y.-Y., Chen, Z.-X., Wang, T., Hu, S., Nan, Z.-A., et al. (2019). Toward Long-Term Stability: Single-Crystal Alloys of Cesium-Containing Mixed Cation and Mixed Halide Perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1665–1671. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11610

Chen, Z., Dong, Q., Liu, Y., Bao, C., Fang, Y., Lin, Y., et al. (2017). Thin Single crystal Perovskite Solar Cells to Harvest Below-Bandgap Light Absorption. Nat. Commun. 8, 1890. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02039-5

Chen, Z., Li, C., Zhumekenov, A. A., Zheng, X., Yang, C., Yang, H., et al. (2019). Solution‐Processed Visible‐Blind Ultraviolet Photodetectors with Nanosecond Response Time and High Detectivity. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1900506. doi:10.1002/adom.201900506

Chen, Z., Liu, F., Zeng, Q., Cheng, Z., Du, X., Jin, G., et al. (2015). Efficient Aqueous-Processed Hybrid Solar Cells from a Polymer with a Wide Bandgap. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 10969–10975. doi:10.1039/C5TA02285A

Chen, Z., Turedi, B., Alsalloum, A. Y., Yang, C., Zheng, X., Gereige, I., et al. (2019). Single-Crystal MAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells Exceeding 21% Power Conversion Efficiency. ACS Energ. Lett. 4, 1258–1259. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00847

Chen, Z., Zeng, Q., Liu, F., Jin, G., Du, X., Du, J., et al. (2015). Efficient Inorganic Solar Cells from Aqueous Nanocrystals: the Impact of Composition on Carrier Dynamics. RSC Adv. 5, 74263–74269. doi:10.1039/C5RA15805B

Chen, Z., Zhang, H., Xing, Z., Hou, J., Li, J., Wei, H., et al. (2013). Aqueous-solution-processed Hybrid Solar Cells with Good thermal and Morphological Stability. Solar Energ. Mater. Solar Cell 109, 254–261. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2012.11.018

Chen, Z., Zhang, H., Yu, W., Li, Z., Hou, J., Wei, H., et al. (2013). Inverted Hybrid Solar Cells from Aqueous Materials with a PCE of 3.61%. Adv. Energ. Mater. 3, 433–437. doi:10.1002/aenm.201200741

Chen, Z., Zhang, H., Zeng, Q., Wang, Y., Xu, D., Wang, L., et al. (2014). In Situ Construction of Nanoscale CdTe-CdS Bulk Heterojunctions for Inorganic Nanocrystal Solar Cells. Adv. Energ. Mater. 4, 1400235. doi:10.1002/aenm.201400235

Cheng, X., Yang, S., Cao, B., Tao, X., and Chen, Z. (2020). Single Crystal Perovskite Solar Cells: Development and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1905021. doi:10.1002/adfm.201905021

Chiba, T., Hayashi, Y., Ebe, H., Hoshi, K., Sato, J., Sato, S., et al. (2018). Anion-exchange Red Perovskite Quantum Dots with Ammonium Iodine Salts for Highly Efficient Light-Emitting Devices. Nat. Photon 12, 681–687. doi:10.1038/s41566-018-0260-y

Chiba, T., Hoshi, K., Pu, Y.-J., Takeda, Y., Hayashi, Y., Ohisa, S., et al. (2017). High-Efficiency Perovskite Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Devices by Effective Washing Process and Interfacial Energy Level Alignment. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 9, 18054–18060. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b03382

Dong, Q., Fang, Y., Shao, Y., Mulligan, P., Qiu, J., Cao, L., et al. (2015). Electron-hole Diffusion Lengths > 175 μm in Solution-Grown CH 3 NH 3 PbI 3 Single Crystals. Science 347, 967–970. doi:10.1126/science.aaa5760

Feng, A., Jiang, X., Zhang, X., Zheng, X., Zheng, W., Mohammed, O. F., et al. (2020). Shape Control of Metal Halide Perovskite Single Crystals: From Bulk to Nanoscale. Chem. Mater. 32, 7602–7617. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c02269

Im, J. H., Lee, C. R., Lee, J. W., Park, S. W., and Park, N. G. (2011). 6.5% Efficient Perovskite Quantum-Dot-Sensitized Solar Cell. Nanoscale 3, 4088–4093. doi:10.1039/C1NR10867K

Jiang, X., Chen, Z., and Tao, X. (2020). (1-C5H14N2Br)2MnBr4: A Lead-Free Zero-Dimensional Organic-Metal Halide with Intense Green Photoluminescence. Front. Chem. 8, 352. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00352

Jiang, X., Fu, X., Ju, D., Yang, S., Chen, Z., and Tao, X. (2020). Designing Large-Area Single-Crystal Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Energ. Lett. 5, 1797–1803. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.0c00436

Jiang, X., Xia, S., Zhang, J., Ju, D., Liu, Y., Hu, X., et al. (2019). Exploring Organic Metal Halides with Reversible Temperature‐Responsive Dual‐Emissive Photoluminescence. ChemSusChem 12, 5228–5232. doi:10.1002/cssc.201902481

Kim, H. S., Lee, C. R., Im, J. H., Lee, K. B., Moehl, T., Marchioro, A., et al. (2012). Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%. Sci. Rep. 2, 591. doi:10.1038/srep00591

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y., and Miyasaka, T. (2009). Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051. doi:10.1021/ja809598r

Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N., and Snaith, H. J. (2012). Efficient Hybrid Solar Cells Based on Meso-Superstructured Organometal Halide Perovskites. Science 338, 643–647. doi:10.1126/science.1228604

Li, G., Rivarola, F. W. R., Davis, N. J. L. K., Bai, S., Jellicoe, T. C., de la Peña, F., et al. (2016). Highly Efficient Perovskite Nanocrystal Light-Emitting Diodes Enabled by a Universal Crosslinking Method. Adv. Mater. 28, 3528–3534. doi:10.1002/adma.201600064

Li, J., Xu, L., Wang, T., Song, J., Chen, J., Xue, J., et al. (2017). 50-Fold EQE Improvement up to 6.27% of Solution-Processed All-Inorganic Perovskite CsPbBr3 QLEDs via Surface Ligand Density Control. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603885. doi:10.1002/adma.201603885

Li, X., Wang, Y., Sun, H., and Zeng, H. (2017). Amino-Mediated Anchoring Perovskite Quantum Dots for Stable and Low-Threshold Random Lasing. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701185. doi:10.1002/adma.201701185

Lin, Y., Bai, Y., Fang, Y., Chen, Z., Yang, S., Zheng, X., et al. (2018). Enhanced Thermal Stability in Perovskite Solar Cells by Assembling 2D/3D Stacking Structures. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 654–658. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02679

Ling, X., Zhou, S., Yuan, J., Shi, J., Qian, Y., Larson, B. W., et al. (2019). 14.1% CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dot Solar Cells via Cesium Cation Passivation. Adv. Energ. Mater. 9, 1900721. doi:10.1002/aenm.201900721

Liu, F., Ding, C., Zhang, Y., Kamisaka, T., Zhao, Q., Luther, J. M., et al. (2019). GeI2 Additive for High Optoelectronic Quality CsPbI3 Quantum Dots and Their Application in Photovoltaic Devices. Chem. Mater. 31, 798–807. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b03871

Liu, Y., Li, N., Sun, R., Zheng, W., Liu, T., Li, H., et al. (2021). Stable Metal-Halide Perovskites for Luminescent Solar Concentrators of Real-Device Integration. Nano Energy 85, 105960. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.105960

Lu, M., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Guo, J., Shen, X., Yu, W. W., et al. (2018). Simultaneous Strontium Doping and Chlorine Surface Passivation Improve Luminescence Intensity and Stability of CsPbI 3 Nanocrystals Enabling Efficient Light‐Emitting Devices. Adv. Mater. 30, 1804691. doi:10.1002/adma.201804691

Pan, J., Shang, Y., Yin, J., De Bastiani, M., Peng, W., Dursun, I., et al. (2018). Bidentate Ligand-Passivated CsPbI3 Perovskite Nanocrystals for Stable Near-Unity Photoluminescence Quantum Yield and Efficient Red Light-Emitting Diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 562–565. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b10647

Sanehira, E. M., Marshall, A. R., Christians, J. A., Harvey, S. P., Ciesielski, P. N., Wheeler, L. M., et al. (2017). Enhanced Mobility CsPbI3 Quantum Dot Arrays for Record-Efficiency, High-Voltage Photovoltaic Cells. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao4204. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao4204

Shao, Y., Liu, Y., Chen, X., Chen, C., Sarpkaya, I., Chen, Z., et al. (2017). Stable Graphene-Two-Dimensional Multiphase Perovskite Heterostructure Phototransistors with High Gain. Nano Lett. 17, 7330–7338. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02980

Shen, X., Zhang, Y., Kershaw, S. V., Li, T., Wang, C., Zhang, X., et al. (2019). Zn-Alloyed CsPbI3 Nanocrystals for Highly Efficient Perovskite Light-Emitting Devices. Nano Lett. 19, 1552–1559. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b04339

Song, J., Fang, T., Li, J., Xu, L., Zhang, F., Han, B., et al. (2018). Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Passivation Enables Perovskite QLEDs with an EQE of 16.48. Adv. Mater. 30, e1805409. doi:10.1002/adma.201805409

Song, J., Li, J., Xu, L., Li, J., Zhang, F., Han, B., et al. (2018). Room-Temperature Triple-Ligand Surface Engineering Synergistically Boosts Ink Stability, Recombination Dynamics, and Charge Injection toward EQE-11.6% Perovskite QLEDs. Adv. Mater. 30, e1800764. doi:10.1002/adma.201800764

Song, J., Li, J., Li, X., Xu, L., Dong, Y., and Zeng, H. (2015). Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Inorganic Perovskite Cesium Lead Halides (CsPbX3). Adv. Mater. 27, 7162–7167. doi:10.1002/adma.201502567

Sum, T. C., and Mathews, N. (2014). Advancements in Perovskite Solar Cells: Photophysics behind the Photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2518–2534. doi:10.1039/C4EE00673A

Sun, L., Li, W., Zhu, W., and Chen, Z. (2020). Single-crystal Perovskite Detectors: Development and Perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 11664–11674. doi:10.1039/D0TC02944K

Sutherland, B. R., and Sargent, E. H. (2016). Perovskite Photonic Sources. Nat. Photon 10, 295–302. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2016.62

Swarnkar, A., Marshall, A. R., Sanehira, E. M., Chernomordik, B. D., Moore, D. T., Christians, J. A., et al. (2016). Quantum Dot-Induced Phase Stabilization of α-CsPbI 3 Perovskite for High-Efficiency Photovoltaics. Science 354, 92–95. doi:10.1126/science.aag2700

Wang, L., Fu, K., Sun, R., Lian, H., Hu, X., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Ultra-stable CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanosheets for X-Ray Imaging Screen. Nano-micro Lett. 11, 52. doi:10.1007/s40820-019-0283-z

Wang, Q., Jin, Z., Chen, D., Bai, D., Bian, H., Sun, J., et al. (2018). Μ-Graphene Crosslinked CsPbI3 Quantum Dots for High Efficiency Solar Cells with Much Improved Stability. Adv. Energ. Mater. 8, 1800007. doi:10.1002/aenm.201800007

Wang, Q., Zheng, X., Deng, Y., Zhao, J., Chen, Z., and Huang, J. (2017). Stabilizing the α-Phase of CsPbI3 Perovskite by Sulfobetaine Zwitterions in One-step Spin-Coating Films. Joule 1, 371–382. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2017.07.017

Wang, X., Liu, Y., Liu, N., Sun, R., Zheng, W., Liu, H., et al. (2021). Revisiting the Nanocrystal Formation Process of Zero-Dimensional Perovskite. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9, 4658–4663. doi:10.1039/D1TA00428J

Wang, Y., Li, X., Song, J., Xiao, L., Zeng, H., and Sun, H. (2015). All-Inorganic Colloidal Perovskite Quantum Dots: A New Class of Lasing Materials with Favorable Characteristics. Adv. Mater. 27, 7101–7108. doi:10.1002/adma.201503573

Wheeler, L. M., Sanehira, E. M., Marshall, A. R., Schulz, P., Suri, M., Anderson, N. C., et al. (2018). Targeted Ligand-Exchange Chemistry on Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots for High-Efficiency Photovoltaics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10504–10513. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b04984

Wu, J., Wang, L., Feng, A., Yang, S., Li, N., Jiang, X., et al. (2021). Self-Powered FA0.55MA0.45PbI3 Single-Crystal Perovskite X-Ray Detectors with High Sensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109149. doi:10.1002/adfm.202109149

Xu, Y., Chen, Q., Zhang, C., Wang, R., Wu, H., Zhang, X., et al. (2016). Two-Photon-Pumped Perovskite Semiconductor Nanocrystal Lasers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3761–3768. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b12662

Yakunin, S., Protesescu, L., Krieg, F., Bodnarchuk, M. I., Nedelcu, G., Humer, M., et al. (2015). Low-threshold Amplified Spontaneous Emission and Lasing from Colloidal Nanocrystals of Caesium lead Halide Perovskites. Nat. Commun. 6, 8056. doi:10.1038/ncomms9056

Yao, S., Chen, Z., Li, F., Xu, B., Song, J., Yan, L., et al. (2015). High-Efficiency Aqueous-Solution-Processed Hybrid Solar Cells Based on P3HT Dots and CdTe Nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 7, 7146–7152. doi:10.1021/am508985q

Yuan, J., Ling, X., Yang, D., Li, F., Zhou, S., Shi, J., et al. (2018). Band-Aligned Polymeric Hole Transport Materials for Extremely Low Energy Loss α-CsPbI3 Perovskite Nanocrystal Solar Cells. Joule 2, 2450–2463. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.08.011

Zai, H., Zhu, C., Xie, H., Zhao, Y., Shi, C., Chen, Z., et al. (2018). Congeneric Incorporation of CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals in a Hybrid Perovskite Heterojunction for Photovoltaic Efficiency Enhancement. ACS Energ. Lett. 3, 30–38. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00925

Zeng, Q., Zhang, X., Feng, X., Lu, S., Chen, Z., Yong, X., et al. (2018). Polymer-Passivated Inorganic Cesium Lead Mixed-Halide Perovskites for Stable and Efficient Solar Cells with High Open-Circuit Voltage over 1.3 V. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705393. doi:10.1002/adma.201705393

Zeng, Q., Zhang, X., Liu, C., Feng, T., Chen, Z., Zhang, W., et al. (2019). Inorganic CsPbI2 Br Perovskite Solar Cells: The Progress and Perspective. Sol. RRL 3, 1800239. doi:10.1002/solr.201800239

Zhang, J., Jin, Z., Liang, L., Wang, H., Bai, D., Bian, H., et al. (2018). Iodine-Optimized Interface for Inorganic CsPbI2Br Perovskite Solar Cell to Attain High Stabilized Efficiency Exceeding 14. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 5, 1801123. doi:10.1002/advs.201801123

Zhang, X., Lin, H., Huang, H., Reckmeier, C., Zhang, Y., Choy, W. C. H., et al. (2016). Enhancing the Brightness of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystal Based Green Light-Emitting Devices through the Interface Engineering with Perfluorinated Ionomer. Nano Lett. 16, 1415–1420. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04959

Zhang, X., Lu, M., Zhang, Y., Wu, H., Shen, X., Zhang, W., et al. (2018). PbS Capped CsPbI3 Nanocrystals for Efficient and Stable Light-Emitting Devices Using P-I-N Structures. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 1352–1359. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.8b00386

Zhang, X., Sun, C., Zhang, Y., Wu, H., Ji, C., Chuai, Y., et al. (2016). Bright Perovskite Nanocrystal Films for Efficient Light-Emitting Devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 4602–4610. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02073

Zhang, X., Xu, B., Zhang, J., Gao, Y., Zheng, Y., Wang, K., et al. (2016). All-Inorganic Perovskite Nanocrystals for High-Efficiency Light Emitting Diodes: Dual-phase CsPbBr3 -CsPb2 Br5 Composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 4595–4600. doi:10.1002/adfm.201600958

Zhao, H., Sun, R., Wang, Z., Fu, K., Hu, X., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Zero‐Dimensional Perovskite Nanocrystals for Efficient Luminescent Solar Concentrators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1902262. doi:10.1002/adfm.201902262

Zhao, Q., Hazarika, A., Chen, X., Harvey, S. P., Larson, B. W., Teeter, G. R., et al. (2019). High Efficiency Perovskite Quantum Dot Solar Cells with Charge Separating Heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 10, 2842. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10856-z

Zheng, X., Troughton, J., Gasparini, N., Lin, Y., Wei, M., Hou, Y., et al. (2019). Quantum Dots Supply Bulk- and Surface-Passivation Agents for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Joule 3, 1963–1976. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.05.005

Keywords: metal halide perovskite, nanocrystals, solar cells, light-emitting diodes, lasers

Citation: Hao J and Xiao X (2022) Recent Development of Optoelectronic Application Based on Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Front. Chem. 9:822106. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.822106

Received: 25 November 2021; Accepted: 01 December 2021;

Published: 05 January 2022.

Edited by:

Zhaolai Chen, Shandong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yang Bai, The University of Queensland, AustraliaYuhai Zhang, University of Jinan, China

Copyright © 2022 Hao and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xing Xiao, MTg4M0BzZGhvc3BpdGFsLmNvbS5jbg==

Jianxiu Hao

Jianxiu Hao Xing Xiao

Xing Xiao