94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem., 08 July 2021

Sec. Analytical Chemistry

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.708374

This article is part of the Research TopicWomen in Analytical ChemistryView all 19 articles

We have developed a dual enzymatic system assay involving liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS) to screen AChE and BACE1 ligands. A fused silica capillary (30 cm × 0.1 mm i.d. × 0.362 mm e.d.) was used as solid support. The co-immobilization procedure encompassed two steps and random immobilization. The resulting huAChE+BACE1-ICER/MS was characterized by using acetylcholine (ACh) and JMV2236 as substrates. The best conditions for the dual enzymatic system assay were evaluated and compared to the conditions of the individual enzymatic system assays. Analysis was performed in series for each enzyme. The kinetic parameters (KMapp) and inhibition assays were evaluated. To validate the system, galantamine and a β-secretase inhibitor were employed as standard inhibitors, which confirmed that the developed screening assay was able to identify reference ligands and to provide quantitative parameters. The combination of these two enzymes in a single on-line system allowed possible multi-target inhibitors to be screened and identified. The innovative huAChE+BACE1-ICER/MS dual enzymatic system reported herein proved to be a reliable tool to identify and to characterize hit ligands for AChE and BACE1 in an enzymatic competitive environment. This innovative system assay involved lower costs; measured the product from enzymatic hydrolysis directly by MS; enabled immediate recovery of the enzymatic activity; showed specificity, selectivity, and sensitivity; and mimicked the cellular process.

Enzymes, play a fundamental role in cellular biochemical processes and are involved in many pathologies, have been investigated by researchers in the field of drug discovery and development. Investigations into the interaction of proteins and enzymes with target ligands provide essential information about biological systems, contributing to the design of new therapeutic interventions (Silber, 2010; Mignani et al., 2016; Cass et al., 2020).

Given that various small molecules are available for the production of new drugs and in view of the numerous biological targets known to date, new strategies must be adopted to develop relevant, reproducible, reliable, and robust moderate to high-throughput screening platforms for drug discovery (Janzen, 2014; Hage, 2017).

In this context, robust screening assays that employ enzymes immobilized on solid supports have received increasing attention because they offer advantages like improved stability and the possibility of proteins being reused (de Moraes et al., 2016). Such screening assays are based on bioaffinity chromatography, which combines the specificity and sensitivity of an enzymatic reaction with the automation and reproducibility of a chromatographic system (Acker and Auld, 2014; de Moraes et al., 2019).

Current approaches for high-throughput screening (HTS) are based on the search for compounds with efficacy toward a single target. However, a new paradigm is emerging in pharmacological research-exploration of the bioactivity of compounds at multiple targets (Mignani et al., 2016). This could enhance the therapeutic efficacy for diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which has heterogeneous etiology and complex mechanism and is the most common form of dementia leading to neurodegeneration (Anand et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2016; Ramsay et al., 2018). Indeed, existing treatments for AD have shortcomings or result in failure, so researchers have been devoted to changing drug design strategies to investigate multitarget-directed ligands (Hughes et al., 2016; de Freitas Silva et al., 2018; Maramai et al., 2020; Uddin et al., 2021).

Because the enzymes acetylcholinesterase and beta-secretase are the main targets involved in AD progression, they have been widely studied, paving the way for future pharmacological treatment of the disease (Deardorff et al., 2015; Coimbra et al., 2018). Acetylcholinesterase (AChE, EC 3.1.1.7), a carboxyl transferase found in neuromuscular junctions and cholinergic brain synapses, occurs in all species belonging to the animal kingdom. AChE regulates the end of the transmission of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in cholinergic synapses (Fotiou et al., 2015). In turn, beta-secretase 1 (BACE1, EC 3.4.23.48), an aspartyl protease found in the brain, plays a pivotal part in the formation of the myelin sheath in peripheral nerve cells. BACE1 initiates the proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) at the luminal end of the cell membrane, forming the C-terminal fragment that is subsequently cleaved by γ-secretase at the N-terminal end, to generate the amyloid peptide (Aβ peptide) (Willem et al., 2006). Regulating both AChE and BACE1 during the treatment of AD is important and has motivated the scientific community to search for molecules that can inhibit these enzymes more efficiently (Deardorff et al., 2015; Fotiou et al., 2015; Prati et al., 2018).

Ligand screening studies based on assays with AChE (Vanzolini et al., 2018; Seidl et al., 2019) and BACE (Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso, 2017; Schejbal et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2021) immobilized on solid supports have been reported. However, the modulating effect of the screened bioactive compound may present limitations in the entire biological system in vivo, so targeting a single target can produce undesirable dual or synergistic effects (Pang et al., 2012). Therefore, developing dual enzymatic system assays that can mimic cellular process has become relevant for better understanding of these mechanisms of action in biological systems and drug discovery research.

Immobilized enzymes are widely used in many other sectors such as the pharmaceutical, chemical, and cosmetic industries, food processing, biofuel production, medical devices and biosensors, (Basso and Serban, 2019; Basso and Serban, 2020), and proteomic analyses by online protein digestion (Wang et al., 2016; Toth et al., 2017).

Multi-target systems can be developed by co-immobilization (Orrego et al., 2020) and have aroused interest due to their different applications, which include screening of ligands (Chen et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020), syntheses of products (Betancor and Luckarift, 2010), design of biocatalyst cascades (Kang et al., 2014), and construction of biosensors to detect diseases (Zhang et al., 2012).

Given the inability of the one-target one-molecule strategy to develop efficient drugs for AD treatment over the last 20 years (Blaikie et al., 2019), we were motivated to develop a dual system assay to screen multitarget-directed ligands that are more fitting to AD treatment. To contribute to this field, here we report the development of an innovative, automated dual enzymatic system assay based on AChE and BACE1 co-immobilized on the inner surface of a fused silica capillary (30 cm × 0.1 mm i.d. × 0.362 mm e.d.) to screen ligands. Co-immobilization comprised two steps: first, the fused silica capillary was activated; then, the enzymes were covalently attached via amine-glutaraldehyde reaction. The resulting huAChE+BACE1-ICER was connected as a bioaffinity column to a liquid chromatographic system (LC) coupled to mass spectrometry (MS), to measure the activities of the enzymes. Comparisons with individual enzymatic systems were made. Next, the dual enzymatic system assay was validated, which allowed us to confirm standard inhibitors for both enzymes by determining the half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50). The dual enzymatic system assay proved to be an improvement on the HTS technique and can aid the search for multitarget-directed ligands in drug discovery for complex diseases.

The lyophilized powders of the enzymes β-secretase (BACE1, EC 3.4.23.48, human extracellular domain and recombinant C-terminal FLAG®-tagged expressed in HEK 293 cells) and acetylcholinesterase (huAChE EC 3.1.1.7, 1,000 units.mg−1 from human recombinant, expressed in HEK 293 cells), the β-secretase inhibitor, acetylcholine iodide (ACh), and galantamine hydrobromide were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). The peptide substrate ortho-aminobenzoyl (Abz)-(Asn670, Leu671)-Amyloid β A4 Protein Precursor770 (669–674) – ethylenediamine 2,4-dinitrophenol (EDDnp) trifluoroacetate salt (named JMV2236 hereafter) was acquired from Bachem AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Glutaraldehyde solution (25%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), solution components, and all the chemicals used during the immobilization procedure were of analytical grade and were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, United States), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Synth (São Paulo, Brazil), or Acros (Geel, Belgium).

The water used in all the preparations was deionized in a Millipore Milli-Q® system (Millipore, São Paulo, Brazil). The fused silica capillary (0.362 mm × 0.1 mm i.d.) was purchased from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ, United States).

The mobile phases were prepared daily. The JMV2236 (1 mM) and β-secretase inhibitor (1 mM) stock solutions were prepared in DMSO and stored at -20°C. The ACh (1 mM) and galantamine (1 mM) stock solutions were prepared in ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5) and stored at -6°C.

The LC-MS analyses were conducted on an LC system Nexera XR HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with two LC 20AD pumps, an SIL-20A autosampler, a DGU 20A degasser, a CTO-20A oven, and an interfaced CBM-20A system. The LC system was coupled to an AmaZon speed Ion Trap (IT) Mass Spectrometry (MS) (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an Electrospray Ionization (ESI) interface. Individual and dual enzymatic systems (30 cm × 0.1 mm i.d. × 0.362 mm e.d.) were placed in the LC system as the bioaffinity column for on-flow MS.

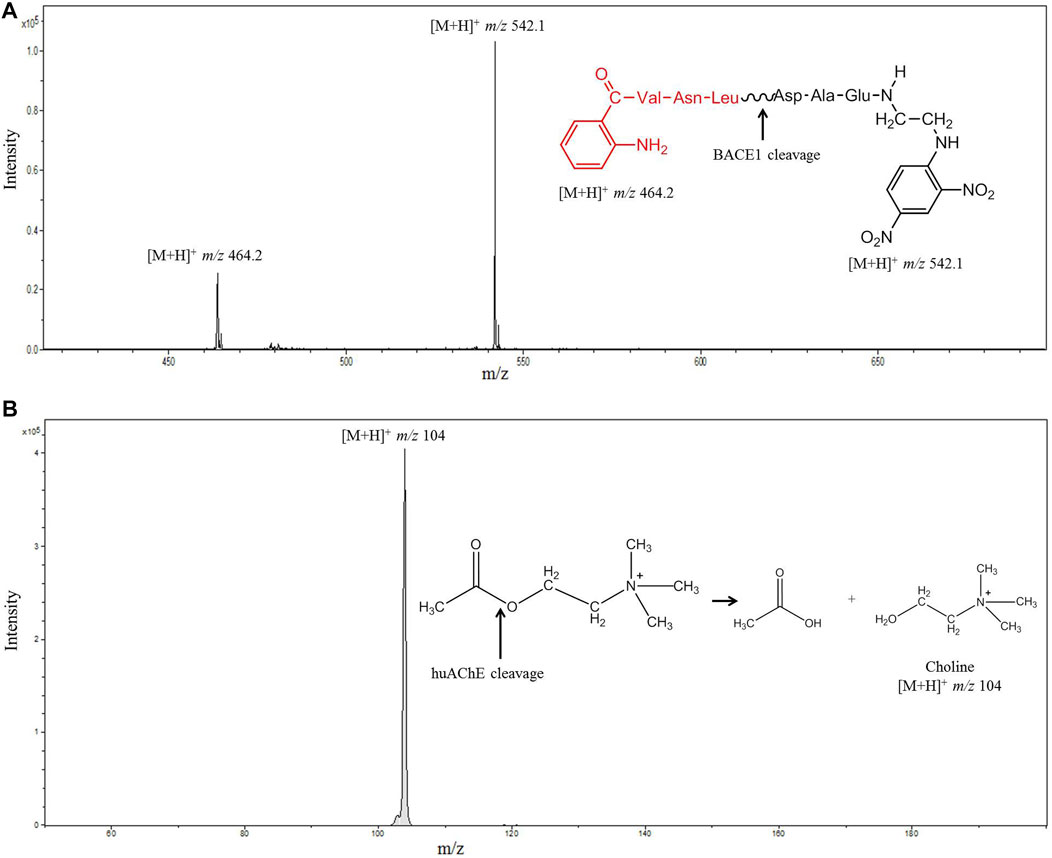

The ESI ionization parameters were as follows: capillary voltage = 4.000 V, end plate voltage = 500 V, drying gas flow = 6 L min−1, drying temperature = 270°C, and nebulizer pressure = 18 psi. MS operating in the single ion-monitoring mode under positive ionization as follows: for huAChE (UltraScan 50–250 m/z), detection of the cations [M+H]+m/z 146 (ACh) and [M+H]+m/z 104 (Ch, the product of the enzymatic catalysis); for BACE1 (enhanced resolution 300–1,000 m/z), detection of the cations [M+H]+m/z 987.5 (JMV2236) and [M+H]+m/z 464.2 and m/z 542.1 (JMV2236 product of BACE1-catalyzed hydrolysis).

The LC analyses were performed at 37°C; 15 mM ammonium acetate solution pH 4.5 was used as mobile phase (pump A) at a flow rate of 20 μL min−1, and a second pump (B) delivered methanol after the ICER and before the IT-MS throughout a “T” shaped connection, at the same flow rate as the mobile phase of pump A (See Table 1).

The data were collected with the Bruker Daltonics Data Analysis software (version 4.3).

A syringe pump model 11 Plus advanced single (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, United States) was used to infuse all the solutions during the immobilization procedure.

huAChE (17 units.ml−1 in 50 mM phosphate solution, pH 7.4) and BACE1 (942.8 units.ml−1 in 50 mM phosphate solution, pH 7.4) were immobilized, separately, on the internal surface of an open tubular silica capillary (100 cm × 0.1 mm i.d × 0.362 mm e.d.) by following previous protocols for individual enzyme immobilization as described in (Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso, 2017).

In each case, the 100-cm capillary was divided, to produce three 30-cm-long huAChE-ICERs or BACE1-ICERs.

For huAChE-ICER and BACE1-ICER, 10-µL aliquots of ACh (70 µM) or JMV2236 (100 µM) solution at different pH values (from 4.0 to 6.0) were injected into the individual enzymatic system operating at 0.02 ml min−1 and 37°C.

The KMapp constant of huAChE-ICER was obtained by using different ACh concentrations (25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 250, or 1,000 μM) in ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5). To this end, 20 μL of each solution was further diluted to a final volume of 100 μL with ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 8.0 or pH 4.5). The final solutions were vortex-mixed for 10 s, and 10-μL aliquots were injected into the huAChE-ICER-LC-MS system in triplicate.

The KMapp constant of BACE1-ICER was obtained. Briefly, 5-µL aliquots of JMV2236 solution at various concentrations (from 10 to 100 µM) were injected into the BACE1-ICER-MS system, in triplicate. The assayed solutions were obtained by addition of 25 µL of JMV2236 solution at different concentrations, completed to a final volume of 50 µL with ammonium acetate solution (2 mM, pH 4.5) as described in Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso (2017).

The data were fitted by using nonlinear regression in a Michaelis-Menten plot, and the KMapp values were obtained with the software GraphPad Prism version 5.0.

To determine the half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50), galantamine and a β-secretase inhibitor were used as reference inhibitors for BACE1-ICER and huAChE-ICER, respectively (Andrau et al., 2003; Darvesh et al., 2003; Marques et al., 2011).

For huAChE-ICER, 10-µL aliquots of solutions containing increasing galantamine (0.05–50 µM) concentrations and ACh (70 µM) were injected into the huAChE-ICER-LC-MS system, in triplicate. The assay solutions were obtained by using 20 µL of a solution containing ACh (350 µM) and 10 µL of a solution containing different galantamine concentrations (0.05, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.0, 10, 15, 25, or 50 µM). The final volume was completed to 100 µL with ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5).

The product areas obtained in the presence (Pi) and absence (P0) of the inhibitor were compared, and the percentage of inhibition was calculated by using Eq. 1:

For each standard inhibitor, an inhibition curve was constructed by plotting the % inhibition versus the concentration of the inhibitor. The software GraphPad Prism 5 was used to obtain the IC50 values by nonlinear regression analysis.

The IC50 for BACE1 was obtained by injecting 5 uL aliquots of solutions containing increasing concentrations of the β-secretase inhibitor (from 0.05 to 10 µM) and JMV2236 (5 µM) into the BACE1-ICER-MS system, in triplicate. The assayed solutions were obtained by addition of 10 µL of JMV2236 (50 µM) and 10 µL of a solution containing different concentrations of reference inhibitor, completed to a final volume of 50 µL with ammonium acetate solution (2 mM, pH 4.5) (Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso, 2017).

huAChE and BACE1 were co-immobilized on the internal surface of an open tubular silica capillary (100 cm × 0.1 mm i.d. × 0.362 mm e.d.) according to previous protocols described for individual enzymes (Vanzolini et al., 2013; Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso, 2017), with minor modifications.

A mixture of the enzymes was infused through the capillary at 50 μL min−1. The mixture consisted of 500 μL of huAChE solution (17 units.ml−1 in 50 mM phosphate solution, pH 7.4) and 500 μL of BACE1 solution at 942.8 units.ml−1 (20 µL of BACE1 solution in 20 mM Hepes solution, pH 7.4, containing 125 mM NaCl, diluted to 500 ml with 50 mM phosphate solution, pH 7.4). The solution was collected, and this step was repeated five times by using the same solution.

The 100-cm capillary was divided, to give three 30-cm-long huAChE+BACE1-ICERs.

While huAChE+BACE1-ICER was not being used, it was maintained at 4°C, with both extremities immersed in 50 mM phosphate solution, pH 7.4.

The apparent kinetic constant (KMapp) was obtained independently for both substrates, ACh and JMV2236, by varying their concentrations.

For the huAChE, ACh stock solutions were prepared (25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 250, and 1,000 μM) in ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5), and 20 μL of each solution was further diluted to a final volume of 100 μL with the ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5). The final solutions were vortex-mixed for 10 s, and 10-μL aliquots were injected into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system, in triplicate.

For the BACE1, JMV2236 stock solutions were prepared (40, 60, 80, 100, 160, 200, 400, and 1,000 µM) in DMSO, and 25 µL of each solution was completed to a final volume of 50 µL with ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5). The final solutions were vortex-mixed for 10 s, and 10-μL aliquots were injected into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system, in triplicate. The conditions are listed in Table 1.

The software GraphPad Prism 5 was used to obtain Michaelis–Menten plots by nonlinear regression analysis.

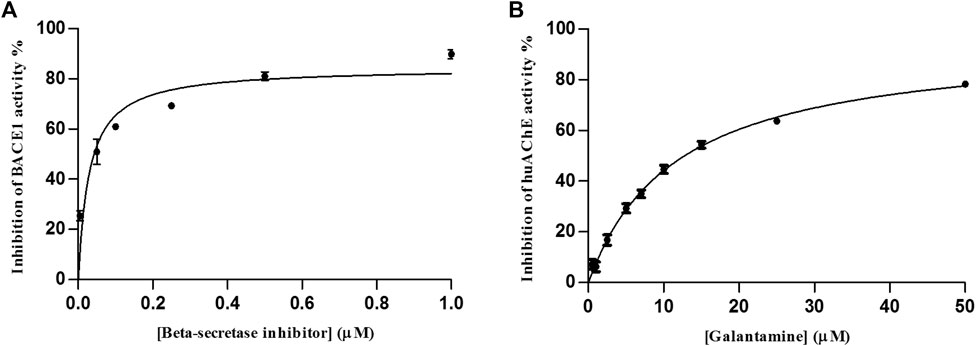

To validate the assay, IC50 parameters were calculated for β-secretase inhibitor and galantamine, standard inhibitors for huAChE and BACE1, respectively (Andrau et al., 2003; Darvesh et al., 2003).

For each enzyme, fixed concentrations of their substrates with increasing concentrations of the standard inhibitors were employed.

For the huAChE, 10-µL aliquots of solutions containing increasing galantamine concentrations (0.05–50 µM) and ACh (70 µM) were injected into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system, in triplicate.

The assay solutions were obtained by adding 20 µL of a solution containing ACh (350 µM) and 10 µL of a solution containing different galantamine concentrations (0.05, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.0, 10, 15, 25, or 50 µM). The final volume was completed to 100 µL with ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5).

For the BACE1, 10-µL aliquots of solutions containing increasing concentrations of the β-secretase inhibitor (0.05–10 µM) and JMV2236 (100 µM) were injected into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system, in triplicate.

The assay solutions were obtained by adding 10 µL of a solution containing JMV2236 (1,000 µM in DMSO) and 10 µL of a solution containing different concentrations of the β-secretase inhibitor (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, or 2.5 in DMSO). The final volume was completed to 50 µL with ammonium acetate solution (15 mM, pH 4.5).

The assay conditions are described in Table 1.

The percentage of inhibition was calculated according to Eq. 1.

For each standard inhibitor, an inhibition curve was constructed by plotting the % inhibition versus the concentration of the inhibitor. The software GraphPad Prism 5 was used to obtain the IC50 values by nonlinear regression analysis.

Before we developed the dual enzymatic system assay by co-immobilization of huAChE and BACE1, we studied the individual enzymes huAChE and BACE1 on the basis of previous works by Vanzolini et al. (2013), Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso (2017) to evaluate the best conditions for monitoring both enzymes in the dual enzymatic system assay by LC-MS.

We successfully immobilized huAChE and BACE1, individually, on the internal surface of an open tubular fused silica capillary, to obtain huAChE-ICER and BACE1-ICER, respectively.

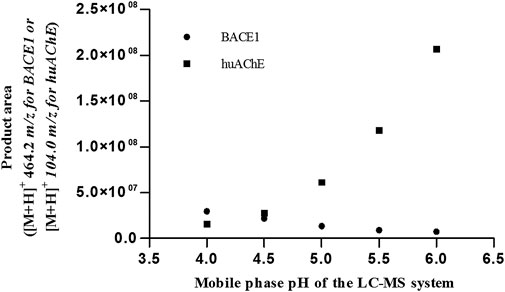

The pH study was crucial because the enzymes have optimal catalytic functions at different pH levels. BACE1 is an aspartyl protease with optimal activity in acidic pH, and AChE, an esterase, works best at pH between 7 and 8.5. On the basis of this information, we investigated the ideal pH for the dual enzymatic system assay.

The enzymatic activity can also be determined at a pH outside the optimum range, but smaller activity values must be accepted. In this way, a larger number of enzymes can be measured at one standardized pH (Bisswanger, 2014).

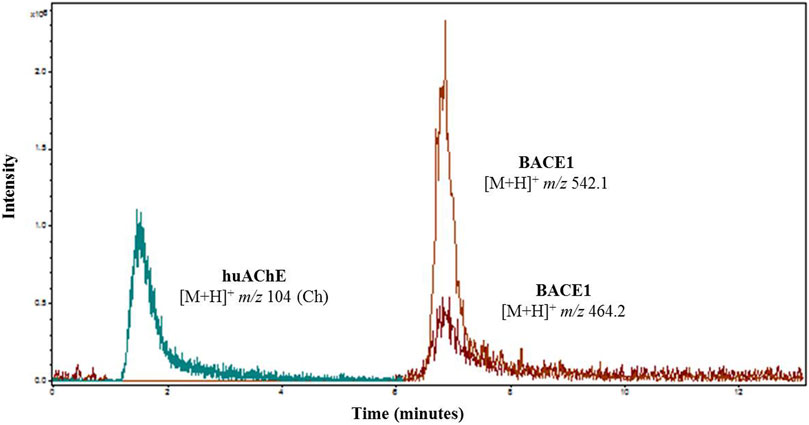

According to Figures 1, 2, at pH values above 5.5, BACE1-ICER does not function well. As for huAChE-ICER, we were able to evaluate its activity in a wide pH range. Our results showed that the ideal pH of the mobile phase for monitoring the dual enzymatic system should be 4.5.

FIGURE 1. Activities of huAChE-ICER and BACE1-ICER in individual enzymatic system assays as a function of the pH of the mobile phase.

FIGURE 2. Overlap of extracted ion chromatogram obtained after injection of 50 µM ACh into the huAChE-ICER-LC-MS system and 50 µM JMV2236 into the BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system. The products of enzymatic hydrolysis were monitored at pH 4.5.

On the basis of these studies, we standardized the mobile phase pH so as to measure the enzymatic catalysis for both enzymes in the dual enzymatic system assay.

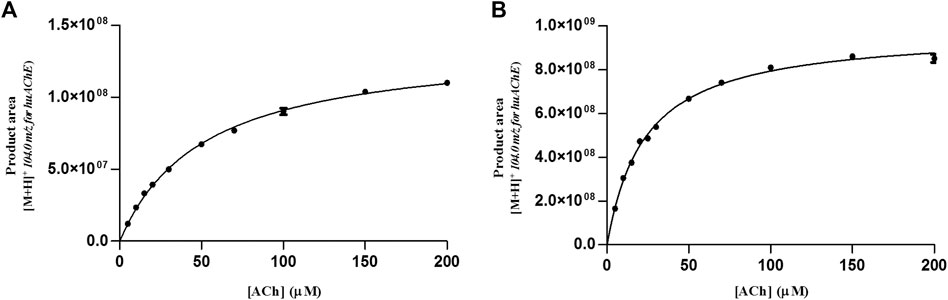

The constant KMapp depends on the reaction medium conditions, so we investigated changes in this constant as a function of the conditions of the enzymatic reactions. BACE1-ICER had been previously studied, and its KMapp is described in Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso (2017). As for huAChE-ICER, KMapp studies were carried out for two mobile phase pH values, 8.0 (optimal for huAChE) and 4.5 (selected for monitoring of the dual enzymatic system assay).

KMapp was calculated as 51.5 ± 2 µM at pH 4.5 and 23.3 ± 1 µM at pH 8.0 (Figure 3). Compared to the value obtained at the optimal pH (8.0) for huAChE, KMapp at pH 4.5 was twice as large and will be used to carry out the ligand screening studies.

FIGURE 3. Michaelis-plots of the product area obtained for huAChE-ICER by using ACh as the substrate. (A) mobile phase pH 4.5 and (B) mobile phase pH 8.0. See Table 1 for conditions.

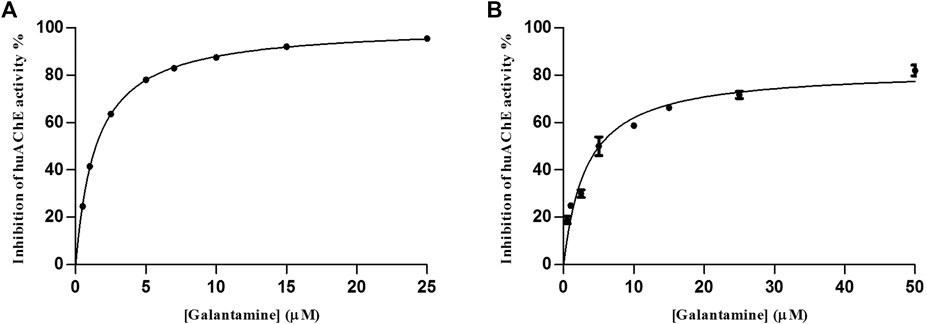

To validate the huAChE-ICER-LC-MS system for ligand screening, we used galantamine, a known inhibitor of cholinesterases (Darvesh et al., 2003). We also calculated the IC50 values for huAChE-ICER at two mobile phase pH values, 8.0 (optimal for huAChE) and 4.5 (selected for monitoring of the dual enzymatic system assay). The IC50 value for BACE1 has been described in (Ferreira Lopes Vilela and Cardoso, 2017).

We determined the IC50 values as 3.29 ± 0.4 µM at pH 4.5 and 1.47 ± 0.03 µM at pH 8.0 (Figure 4), which showed that the huAChE-ICER-LC-MS system was able to identify the standard inhibitor on a micro-scale as compared to data previously reported for this inhibitor.

FIGURE 4. Inhibitory potency curve obtained for huAChE-ICER by using ACh as a substrate. (A) mobile phase pH 4.5 and (B) mobile phase pH 8.0. See Table 1 for conditions.

On the basis of these findings for the individual enzymatic system assays, we were able to establish the best conditions for the dual enzymatic system assay (Table 1).

The co-immobilization process used herein was successful: the activities of both enzymes were preserved after co-immobilization in the fused silica capillary. The random co-immobilization method (Schoffelen and van Hest, 2013) employed glutaraldehyde as linker, to produce covalent interactions with the mixture of enzymes on the support. The LC-MS system and the configuration used to monitor the enzymatic activities allowed us to measure the hydrolysis products by MS directly. We analyzed both enzymes in series, BACE1 and huAChE, respectively. Figure 5 illustrates the results.

FIGURE 5. Mass spectrum obtained after injection of JMV2236 (100 µM) into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system. (A) The product of enzymatic hydrolysis ([M+H]+m/z 464.2 and 542.1) was monitored. (B) Mass spectrum obtained after injection of ACh (70 µM) into the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system by monitoring the product of enzymatic hydrolysis ([M+H]+m/z 104) (Conditions listed in Table 1).

We validated the assay according to guidelines for bioanalytical methods (Cassiano et al., 2009). The calibration curve revealed a linear relationship for JMV2236 concentrations ranging from 10 to 25 µM. For ACh, the calibration curve was linear (1.0–15 μM).

To evaluate the selectivity of the method, we carried out blank runs (15 mM ammonium acetate pH 4.5), where the target analytes were not present. These runs revealed no interference, demonstrating that no carry over occurred between analyses.

For ACh, the limit of quantification (LQ) was 1 µM (RSD = 2.4%, n = 3, and accuracy = 100.0%), and the limit of detection (LD) was 0.5 µM, calculated by the signal-to-noize ratio. For JMV2236, the limit of quantification (LQ) was 10 µM (RSD = 9.2%, n = 3, and accuracy = 100.6%), and the limit of detection (LD) was 5.0 µM, calculated by the signal-to-noize ratio.

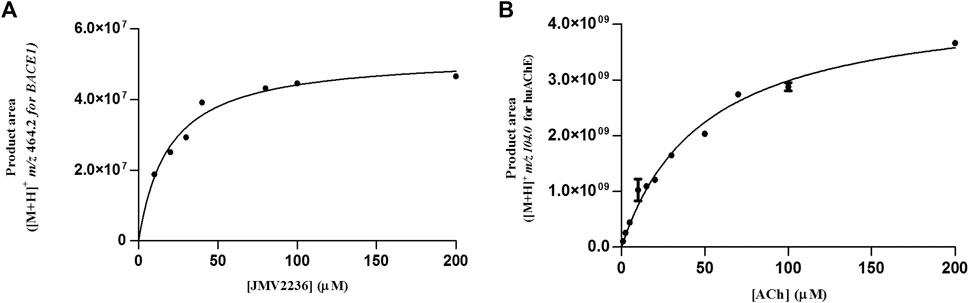

We evaluated the KMapp constants for both enzymes in the dual enzymatic system, to verify whether the values changed due to co-immobilization. We found values of 19.25 ± 3 and 49.6 ± 4 µM for BACE1 and huAChE in the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system, respectively (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Michaelis-Menten plots of the product area obtained for huAChE (A) and BACE1 (B) in the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system by using ACh and JMV2236 as substrates, respectively.

Table 2 compares the KMapp values obtained for the dual and individual system assays. There were no significant differences due to the random co-immobilization and immobilization process.

The individual and dual enzymatic systems developed herein showed that the enzymes catalyzed their substrates in a similar fashion in both systems; that is, their affinities and specificities were not affected. Therefore, we were able to mimic an in vitro cellular environment with two enzymes with distinct catalytic properties in a unique system. Other advantages of the proposed method include reduced costs of reagents and shorter preparation time. In addition, the same mobile phase and bioaffinity column can be used in the analyses, allowing ligands from synthetic or semi-synthetic combinatorial libraries and natural products or marine extracts to be identified and characterized, not to mention that the method can be applied to multi-target ligands. The proposed dual-enzymatic system assay did not allow the two substrates and products cleaved by the enzymes to be detected simultaneously due to the employed MS detector. However, the biocatalysis products were directly quantified in series by an MS detector.

Although the assay for huAChE was not performed under optimal catalysis conditions, we were able to evaluate its activity and selectivity with the same efficacy provided by individual enzymatic system. To validate the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system for the screening of ligands, we used galantamine and the β-secretase inhibitor as reference inhibitors of BACE-1 and huAChE, respectively (Andrau et al., 2003; Darvesh et al., 2003). The IC50 values were 11.6 ± 0.8 µM for galantamine and 0.03 ± 0.008 µM for the β-secretase inhibitor (Figure 7). On the basis of these values, the dual enzymatic system assay was able to identify the standard inhibitors on a micro-scale as compared to data previously reported for these inhibitors.

FIGURE 7. IC50 curve obtained for huAChE (A) and BACE1 (B) in the huAChE+BACE1-ICER-LC-MS system by using ACh and JMV2236 as substrates, respectively.

Each enzyme studied in the dual enzymatic system was selective and specific for its substrate and inhibitor without interference and/or problems during method development (30 days); the enzymatic activities were maintained for over 60 days. The KMapp and IC50 studies showed that co-immobilization did not alter the affinity of BACE1 and huAChEhu, indicating that the approach used herein can be applied to screen multi-target-directed ligands in a competitive environment. This efficient system is a remarkable alternative to common single-enzyme screening methods at various levels during the drug discovery process.

We have described an innovative dual enzymatic system assay based on co-immobilization of huAChE and BACE1 and on-flow LC-MS detection. This is the first time that a dual enzymatic system assay has been developed to screen ligands by a label-free automated screening system bearing two enzymes involved in AD etiology. We developed the novel dual enzymatic system assay by employing an effective random co-immobilization process that provided a system to evaluate the activities of huAChE and BACE1 on-flow by LC-MS through a mobile phase with the same ionic strength and pH even though the enzymes have different kinetic properties.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

AF: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. VN: Methodology, Validation. CC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing.

This investigation was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq - Grants 145013/2019-7, and 303723/2018-1) and the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP - Grants 2019/05363-0; 2014/50249-8 and GSK). This study was partially financed by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (CAPES), Finance Code 001. CC and AF acknowledge the Sao Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the PhD scholarship (2016/02873-0) and CNPq (145013/2019-7).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acker, M. G., and Auld, D. S. (2014). Considerations for the Design and Reporting of Enzyme Assays in High-Throughput Screening Applications. Perspect. Sci. 1, 56–73. doi:10.1016/j.pisc.2013.12.001

Anand, R., Gill, K. D., and Mahdi, A. A. (2014). Therapeutics of Alzheimer's Disease: Past, Present and Future. Neuropharmacology. 76, 27–50. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.004

Andrau, D., Dumanchin-Njock, C., Ayral, E., Vizzavona, J., Farzan, M., Boisbrun, M., et al. (2003). BACE1- and BACE2-Expressing Human Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25859–25866. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302622200

Basso, A., and Serban, S. (2019). Industrial Applications of Immobilized Enzymes-A Review. Mol. Catal. 479, 110607. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2019.110607

Basso, A., and Serban, S. (2020). Overview of Immobilized Enzymes' Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, and Food Industry. Methods Mol Biol. 2100, 27–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0215-7_2

Betancor, L., and Luckarift, H. R. (2010). Co-immobilized Coupled Enzyme Systems in Biotechnology. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 27, 95–114. doi:10.1080/02648725.2010.10648146

Blaikie, L., Kay, G., and Kong Thoo Lin, P. (2019). Current and Emerging Therapeutic Targets of Alzheimer's Disease for the Design of Multi-Target Directed Ligands. Med. Chem. Commun. 10, 2052–2072. doi:10.1039/c9md00337a

Cass, Q. B., Massolini, G., Cardoso, C. L., and Calleri, E. (2020). Editorial: Advances in Bioanalytical Methods for Probing Ligand-Target Interactions. Front. Chem. 8, 8–10. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00378

Cassiano, N. M., Barreiro, J. C., Martins, L. R. R., Oliveira, R. V., and Cass, Q. B. (2009). Validação em métodos cromatográficos para análises de pequenas moléculas em matrizes biológicas. Quím. Nova 32, 1021–1030. doi:10.1590/s0100-40422009000400033

Chen, L., Wang, X., Liu, Y., and Di, X. (2017). Dual-target Screening of Bioactive Components from Traditional Chinese Medicines by Hollow Fiber-Based Ligand Fishing Combined with Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 143, 269–276. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.06.001

Coimbra, J. R. M., Marques, D. F. F., Baptista, S. J., Pereira, C. M. F., Moreira, P. I., Dinis, T. C. P., et al. (2018). Highlights in BACE1 Inhibitors for Alzheimer's Disease Treatment. Front. Chem. 6, 1–10. doi:10.3389/fchem.2018.00178

Darvesh, S., Walsh, R., Kumar, R., Caines, A., Roberts, S., Magee, D., et al. (2003). Inhibition of Human Cholinesterases by Drugs Used to Treat Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis. Associated Disord. 17, 117–126. doi:10.1097/00002093-200304000-00011

de Freitas Silva, M., Dias, K. S. T., Gontijo, V. S., Ortiz, C. J. C., and Viegas, C. (2018). Multi-Target Directed Drugs as a Modern Approach for Drug Design towards Alzheimer's Disease: An Update. Curr Med Chem. 25, 3491–3525. doi:10.2174/0929867325666180111101843

de Moraes, M. C., Cardoso, C. L., and Cass, Q. B. (2019). Solid-Supported Proteins in the Liquid Chromatography Domain to Probe Ligand-Target Interactions. Front. Chem. 7, 1–16. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00752

Deardorff, W. J., Feen, E., and Grossberg, G. T. (2015). The Use of Cholinesterase Inhibitors across All Stages of Alzheimer's Disease. Drugs Aging. 32, 537–547. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0273-x

Ferreira Lopes Vilela, A., and Cardoso, C. L. (2017). An On-Flow Assay for Screening of β-secretase Ligands by Immobilised Capillary Reactor-Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Methods. 9, 2189–2196. doi:10.1039/C7AY00284J

Fotiou, D., Kaltsatou, A., Tsiptsios, D., and Nakou, M. (2015). Evaluation of the Cholinergic Hypothesis in Alzheimer's Disease with Neuropsychological Methods. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 27, 727–733. doi:10.1007/s40520-015-0321-8

Hage, D. S. (2017). Analysis of Biological Interactions by Affinity Chromatography: Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Clin. Chem. 63, 1083–1093. doi:10.1373/CLINCHEM.2016.262253

Hughes, R. E., Nikolic, K., and Ramsay, R. R. (2016). One for All? Hitting Multiple Alzheimer's Disease Targets with One Drug. Front. Neurosci. 10. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00177

Janzen, W. P. (2014). Screening Technologies for Small Molecule Discovery: The State of the Art. Chem. Biol. 21, 1162–1170. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.07.015

Kang, W., Liu, J., Wang, J., Nie, Y., Guo, Z., and Xia, J. (2014). Cascade Biocatalysis by Multienzyme-Nanoparticle Assemblies. Bioconjug. Chem. 25, 1387–1394. doi:10.1021/bc5002399

Maramai, S., Benchekroun, M., Gabr, M. T., and Yahiaoui, S. (2020). Multitarget Therapeutic Strategies for Alzheimer's Disease: Review on Emerging Target Combinations. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 1–27. doi:10.1155/2020/5120230

Marques, L. A., Maada, I., de Kanter, F. J. J., Lingeman, H., Irth, H., Niessen, W. M. A., et al. (2011). Stability-indicating Study of the Anti-alzheimer's Drug Galantamine Hydrobromide. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 55, 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2011.01.022

Mignani, S., Huber, S., Tomás, H., Rodrigues, J., and Majoral, J.-P. (2016). Why and How Have Drug Discovery Strategies in Pharma Changed? what Are the New Mindsets? Drug Discov. Today 21, 239–249. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2015.09.007

Moraes, M. C., Cardoso, C., Seidl, C., Moaddel, R., and Cass, Q. (2016). Targeting Anti-cancer Active Compounds: Affinity-Based Chromatographic Assays. Curr Pharm Des. 22, 5976–5987. doi:10.2174/1381612822666160614080506

Orrego, A. H., López-Gallego, F., Fernandez-Lorente, G., Guisan, J. M., and Rocha-Martín, J. (2020). Co-Immobilization and Co-localization of Multi-Enzyme Systems on Porous Materials. Methods Mol. Biol. 2100, 297–308. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0215-7_19

Pang, M.-H., Kim, Y., Jung, K. W., Cho, S., and Lee, D. H. (2012). A Series of Case Studies: Practical Methodology for Identifying Antinociceptive Multi-Target Drugs. Drug Discov. Today. 17, 425–434. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.003

Prati, F., Bottegoni, G., Bolognesi, M. L., and Cavalli, A. (2018). BACE-1 Inhibitors: From Recent Single-Target Molecules to Multitarget Compounds for Alzheimer's Disease. J. Med. Chem. 61, 619–637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00393

Ramsay, R. R., Popovic‐Nikolic, M. R., Nikolic, K., Uliassi, E., and Bolognesi, M. L. (2018). A Perspective on Multi‐target Drug Discovery and Design for Complex Diseases. Clin. Translational Med. 7, 3. doi:10.1186/s40169-017-0181-2

Schejbal, J., Šefraná, Š., Řemínek, R., and Glatz, Z. (2019). Capillary Electrophoresis Integrated Immobilized Enzyme Reactor for Kinetic and Inhibition Assays of β‐secretase as the Alzheimer's Disease Drug Target*. J. Sep. Sci. 42, 1067–1076. doi:10.1002/jssc.201800947

Schoffelen, S., and van Hest, J. C. (2013). Chemical Approaches for the Construction of Multi-Enzyme Reaction Systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 613–621. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2013.06.010

Seidl, C., Vilela, A. F. L., Lima, J. M., Leme, G. M., and Cardoso, C. L. (2019). A Novel On-Flow Mass Spectrometry-Based Dual Enzyme Assay. Analytica Chim. Acta. 1072, 81–86. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2019.04.057

Silber, B. M. (2010). COMMENTARY Driving Drug Discovery : The Fundamental Role of Academic Labs. Sci Transl Med, 2, 1–7. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000169

Toth, C. A., Kuklenyik, Z., Jones, J. I., Parks, B. A., Gardner, M. S., Schieltz, D. M., et al. (2017). On-column Trypsin Digestion Coupled with LC-MS/MS for Quantification of Apolipoproteins. J. Proteomics. 150, 258–267. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2016.09.011

Uddin, M. S., Al Mamun, A., Kabir, M. T., Ashraf, G. M., Bin-Jumah, M. N., and Abdel-Daim, M. M. (2021). Multi-Target Drug Candidates for Multifactorial Alzheimer's Disease: AChE and NMDAR as Molecular Targets. Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 281–303. doi:10.1007/s12035-020-02116-9

Vanzolini, K. L., da F. Sprenger, R., Leme, G. M., de S. Moraes, V. R., Vilela, A. F. L., Cardoso, C. L., et al. (2018). Acetylcholinesterase Affinity-Based Screening Assay on Lippia Gracilis Schauer Extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 153, 232–237. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2018.02.035

Vanzolini, K. L., Vieira, L. C. C., Corrêa, A. G., Cardoso, C. L., and Cass, Q. B. (2013). Acetylcholinesterase Immobilized Capillary Reactors-Tandem Mass Spectrometry: An On-Flow Tool for Ligand Screening. J. Med. Chem. 56, 2038–2044. doi:10.1021/jm301732a

Wang, B., Shangguan, L., Wang, S., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., and Liu, F. (2016). Preparation and Application of Immobilized Enzymatic Reactors for Consecutive Digestion with Two Enzymes. J. Chromatogr. A. 1477, 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2016.11.027

Willem, M., Garratt, A. N., Novak, B., Citron, M., Kaufmann, S., Rittger, A., et al. (2006). Control of Peripheral Nerve Myelination by the -Secretase BACE1. Science. 314, 664–666. doi:10.1126/science.1132341

Wu, Z.-Y., Zhang, H., Yang, Y.-Y., and Yang, F.-Q. (2020). An Online Dual-Enzyme Co-immobilized Microreactor Based on Capillary Electrophoresis for Enzyme Kinetics Assays and Screening of Dual-Target Inhibitors against Thrombin and Factor Xa. J. Chromatogr. A. 1619, 460948. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2020.460948

Ye, L.-H., Zhang, R., and Cao, J. (2021). Screening of β-secretase Inhibitors from Dendrobii Caulis by Covalently Enzyme-Immobilized Magnetic Beads Coupled with Ultra-high-performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 195, 113845. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113845

Keywords: co-immobilization procedure, dual enzymatic system assay, screening dual- target ligands, acetylcholinesterase, beta-secretase1

Citation: Vilela AFL, Narciso dos Reis VE and Cardoso CL (2021) Co-Immobilized Capillary Enzyme Reactor Based on Beta-Secretase1 and Acetylcholinesterase: A Model for Dual-Ligand Screening. Front. Chem. 9:708374. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.708374

Received: 11 May 2021; Accepted: 23 June 2021;

Published: 08 July 2021.

Edited by:

Eugenia Gallardo, Universidade da Beira Interior, PortugalReviewed by:

Shouyu Wang, Jiangnan University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Vilela, Narciso dos Reis and Cardoso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carmen Lúcia Cardoso, Y2NhcmRvc29AZmZjbHJwLnVzcC5icg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.