- 1Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The Second Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Rare Earth Resource Utilization, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (CIAC), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Changchun, China

- 3Department of Clinical Laboratory, The Second Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

- 4Department of Radiology, The Second Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

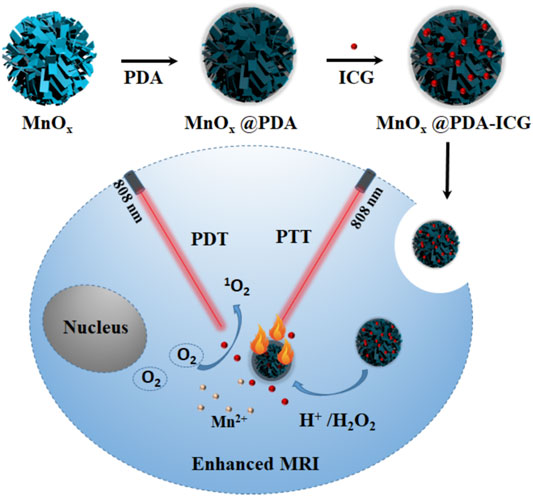

Surgery is the main treatment for liver cancer in clinic owing to its low sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but this results in high mortality, recurrence, and metastasis rates. It is a feasible strategy to construct tumor microenvironments activated by nanotheranostics agents for the diagnosis and therapy of liver cancer. This study reports on a nanotheranostic agent (MONs@PDA-ICG) with manganese oxide nanoflowers (MONs) as core and polydopamine (PDA) as shell loading, with ICG as a photosensitizer and photothermal agent. MONs@PDA-ICG can not only produce ROS to kill cancer cells but also exhibit good photothermal performance for photothermal therapy (PTT). Importantly, O2 generated by MONs decomposition can relieve the tumor hypoxia and further enhance the treatment effects of photodynamic therapy (PDT). In addition, the released Mn2+ ions make MONs@PDA-ICG serve as tumor microenvironments responsive to MRI contrast for highly sensitive and specific liver cancer diagnosis.

Introduction

Liver cancer is the second leading cause of death among all kinds of cancer in the world (Llovet et al., 2016). Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, missing a more treatable stage. At present, because liver cancer is not sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, surgery is the main treatment. However, the recurrence and metastasis rate is 40–70% in the 5 years after operation (Llovet et al., 2005). Therefore, a new treatment with high sensitivity, specificity, and therapeutic efficacy for liver cancer is required.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising treatment of cancer that has attracted increasing attention in recent years, owing to its high selectivity, noninvasiveness, low side effects, and no drug resistance (Agostinis et al., 2011; Lan et al., 2019). Indocyanine green (ICG) is a NIR photosensitizer that has been approved by The US food and drug administration (FDA) for use in clinical diagnosis and therapy (Luo et al., 2011). ICG can not only be excited by NIR light to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS, i.e., singlet oxygen, 1O2) but can also transfer NIR light energy to heat, killing the cancer cells through local high temperature (Trachootham et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016). The synergistic effect of PDT and photothermal therapy (PTT) can improve the treatment efficacy. However, O2 is the key factor of PDT, the hypoxia of tumor microenvironments leads to unsatisfactory treatment effects, severely limiting the further application of PDT in clinical settings (Fan et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Sahu et al., 2020). Therefore, adjusting the TME is a promising strategy to boost the treatment efficacy of PDT.

Early diagnosis plays an important role in ameliorating the prognosis in patients with liver cancer due to its long incubation period, high mortality, and extremely poor prognosis. Molecular imaging technology is the common diagnostic method for liver cancer, including MRI, CT, ultrasonography, and so on (Janib et al., 2010). However, it is difficult to distinguish small liver cancers from cirrhotic nodules by conventional diagnostic imaging technologies. Tumor microenvironments are closely related to tumor formation and metastasis, featuring low pH, hypoxia, a high concentration of glutathione (GSH), and overexpression of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Bo et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2017). Exploring the responsive imaging probes of the tumor microenvironments could improve the sensitivity and specificity of liver cancer, as they generate an imaging signal in the tumor site.

The present study constructed a nanotheranostic agent with manganese oxide nanoflowers (MONs) as core and polydopamine (PDA) as shell loading with ICG as a photosensitizer and photothermal agent (MONs@PDA-ICG) for tumor microenvironments responsive MRI and PDT/PTT synergistic therapy of liver cancer (Scheme 1). Under 808 nm laser illumination, MONs@PDA-ICG can not only produce ROS to kill the cancer cells but also exhibits good photothermal performance. More importantly, MONs core in tumor microenvironments (acidic conditions can produce O2 to improve the treatment effect of PDT. In addition, the paramagnetic Mn2+ ions obtained by MONs core disintegration can achieve pH-activated T1-weighted MRI (Kim et al., 2013; Banobre-Lopez et al., 2018; He et al., 2019). Therefore, MONs@PDA-ICG is promising for the diagnosis and treatment of liver cancer with high sensitivity, specificity, and treatment effects.

SCHEME 1. Schematic illustration of MONs@PDA-ICG for enhanced T1-guided synergetic photodynamic and photothermal therapy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Potassium permanganate (KMnO4), Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris), ethanol, and H2O2 (30%) were obtained from the Beijing Chemical Reagents Company. Oleic acid (OA, >90%) and dopamine hydrochloride were from Aladdin. 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) was separately purchased from Alfa Aesar and Sigma-Aldrich, and CCK-8 was purchased from Changchun Sanbang Pharmaceutical Technology Co (Changchun, China).

Synthesis of MONs

Manganese oxide nanoflowers were synthesized by a previously reported method (Ding et al., 2020). In brief, 50 ml solutions containing 0.1 g KMnO4 were stirred for 30°min, then 1 ml OA was dropped slowly into the mixture and vigorously stirred for another 5 h at room temperature. The dark brown precipitates were dispersed in deionized water after washing with water and ethanol.

Synthesis of MONs@PDA

10 mg MONs and 24 mg Tris were dissolved into 70 ml deionized water. Then 10 mg dopamine hydrochloride solutions (1 mg ml−1) were added drop by drop under ultrasound and stirring. After 2 h, the color of the mixture gradually changed from dark brown to black, and it was then subject to another 8 h stirring. The black solutions were then washed with water and stored at 4°C for future use.

ICG Loading on MONs@PDA

MONs@PDA-ICG was performed by mixing 5 mg ICG and 5 mg MONs@PDA in 5 ml deionized water and stirring overnight in the dark at room temperature. They were then gently washed twice with deionized water and all the washing supernatants were collected to calculate the ICG loading content by UV−vis.

Extracellular O2 Generation From MONs@PDA

60 μL H2O2 (1 M) was added into MONs@PDA (150 μg ml−1, 30 mL) under stirring. Then the dissolved oxygen meter was used to monitor the generated concentrations of O2.

Extracellular 1O2 Detection

0.4 mg MONs@PDA-ICG were dispersed in a 2 ml solution containing ethanol and water at a ratio of 6:4. Then 0.5 μl H2O2 (1 M) and 20 μl DPBF (10 mM) were added. Subsequently, the mixture was exposed to 808 nm irradiation (0.8 W cm−2) for different times (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min) and the 1O2 by UV−vis was measured.

Photothermal Effect and Thermal Stability of MONs@PDA-ICG

Configured solutions with different MONs@PDA-ICG (0, 25, 50, 100 μg ml−1) were irradiated with 808 nm laser for 10 min (1.5 W cm-2) and measured by thermocouple probe to record the changing temperature every 30 s. Every 2 min, thermal photos were taken by an infrared thermal imaging camera. For the evaluation of thermal Stability, MONs@PDA-ICG solution (50 μg ml−1) in quartz cuvette was illuminated for 10 min and naturally cooled down to room temperature. These procedures were duplicated three times.

Cytotoxicity Assay of MONs@PDA-ICG

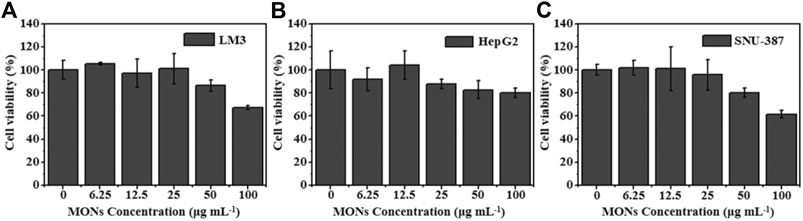

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines (LM3, HepG2, SNU-387) were used to assess the cytotoxicity of MONs@PDA-ICG. They were all seeded in 96-well plates at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After 24 h of being cultured, different MONs@PDA-ICG instead of the completed medium were added for another 24 h incubation. The cytotoxicity was then detected by the CCK-8 method. 100 μl CCK-8 medium was added for 4 h and the absorbance (450 nm) was measured by a plate reader.

In Vitro Therapy

For in vitro treatment, expose the LM3, HepG2, SNU-387 cells, incubated with various MONs@PDA-ICG (0, 6.25,12.5, 25, 50 μg ml−1) for 24 h, to 808 nm laser for 10 min (1.3 W cm−2). Then the same method was manipulated to calculate the cell viability.

In Vitro MRI

The MR images were acquired by measuring different MONs@PDA solutions (Mn content: 0.0325, 0.075, 0.15, 0.3, and 0.6 mM) dispersed with different pH (7.4 and 6.5). The T1 relaxation time was taken by the clinical 3.0 T MRI scanner.

Results and Discussion

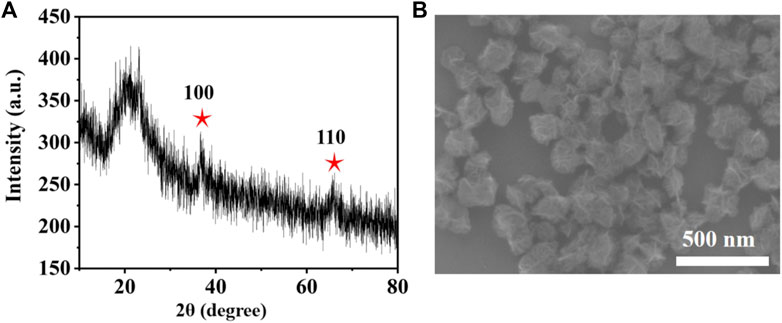

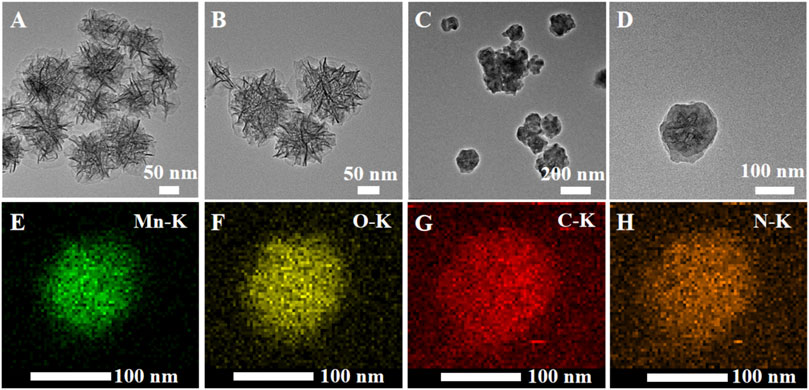

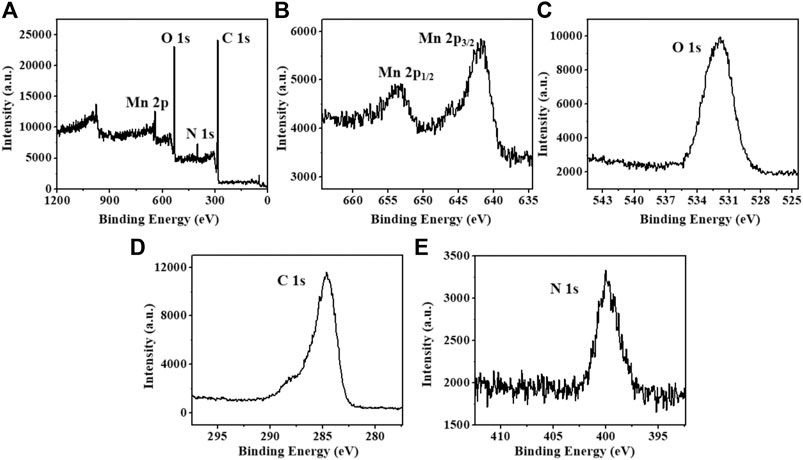

MONs were prepared following previous literature with slight modification (Ding et al., 2020). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern reveals the amorphous structure of MONs (Figure 1A). The scanning electron microscope (SEM) and transmission electron microscope (TEM) images (Figure 1B, Figures 2A,B) show the uniform morphology of MONs with a diameter of about 100 nm. PDA shell was wrapped on the surface of MONs for loading ICG and improving the biocompatibility. As shown in Figures 2C,D, the morphology of MONs@PDA was unchanged after coating with PDA. HAADF-STEM and elemental mapping analysis indicated that Mn, O, N, and C elements were uniformly distributed, demonstrating the successful coating of PDA (Figures 2E–H). The presence of N in the X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of MONs@PDA further confirms that PDA is successfully wrapping (Figure 3). Then, ICG was loading on the surface of MONs@PDA via π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions with a content of 0.372 mg mg−1.

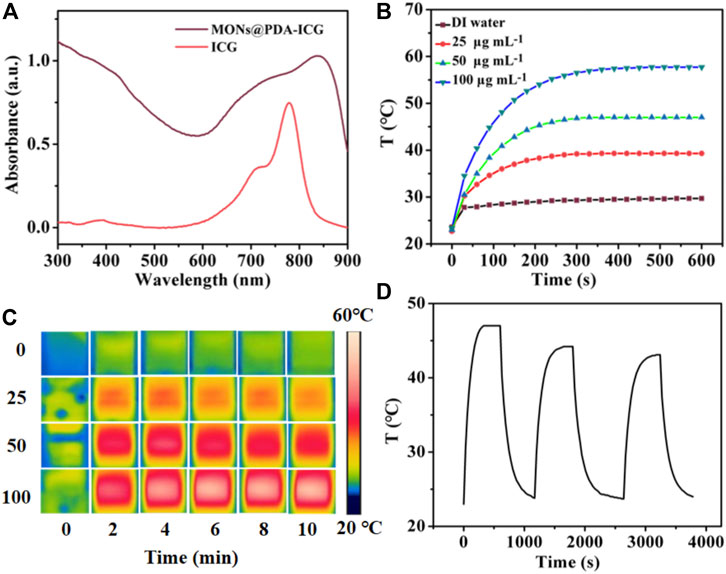

The UV-vis spectrum of MONs@PDA-ICG shows strong NIR absorption owing to the introduction of PDA shell and ICG (Figure 4A). We then investigated the photothermal performance of MONs@PDA-ICG with different concentrations under irradiation with an 808 nm laser (1.5 W cm−2). As shown in Figure 4B , compared to the water, the temperature of MONs@PDA-ICG increased from 23.4 °C to 57.7 °C at a concentration of 100 μg ml−1 after irradiation 10 min (Figures 4B,C). This high temperature can kill cancer cells (Soares et al., 2012). Alternating heating and cooling experiments show that MONs@PDA-ICG has good photothermal stability after three cycles (Figure 4D) and excellent photothermal conversion efficiency (63.32%). The high photothermal conversion efficiency and good photostability enable MONs@PDA-ICG to act as a promising photothermal agent.

FIGURE 4. (A) UV-vis absorption spectrum of MONs@PDA-ICG and Free ICG. (B) Temperature curve of MONs@PDA-ICG with different concentrations under 808 nm laser (1.5 W cm−2) for 10 min (C) Infrared thermal images every 2 min. (D) Cycle curve of MONs@PDA-ICG at 50 μg mL−1.

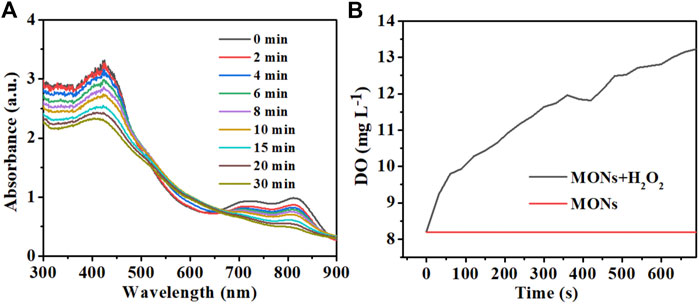

ROS generation is the key factor of PDT, so we evaluated the ROS generation ability of MONs@PDA-ICG using the 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) as the probe whose absorbance at 410 nm decreased in the presence of 1O2. As shown in Figure 5A, the absorbance of DPBF was diminished with the time of irradiation, extending the 808 nm laser, indicating the production of singlet 1O2. In addition, the ability of MONs@PDA was investigated in tumor microenvironments to catalyze the H2O2 decomposition to produce O2. We measured the O2 generation of MONs@PDA after adding 2 mM H2O2 in acidic conditions. As shown in Figure 5B, compared with no H2O2 group, the presence of H2O2 makes MONs@PDA produce more O2 over 10 min. This released that H2O2 was decomposed and generated O2 catalyzed by MONs@PDA, relieving the hypoxia of the tumor. MONs@PDA-ICG is thus promising for highly effective PDT due to this good ROS generation and its ability to modulate tumor microenvironments.

FIGURE 5. (A) UV-vis spectrum of MONs@PDA-ICG with DPBF (20 μL) and H2O2 (10 μL) at different times for detection of the 1O2 generation. (B) O2 generation of MONs@PDA in the presence of 2 mM H2O2.

In tumor microenvironments, MONs@PDA can not only catalyze the H2O2 decomposition to produce O2 but also be dissolved into Mn2+ ions (Equation 1), achieving a tumor microenvironment responsive MRI (Cai et al., 2019).

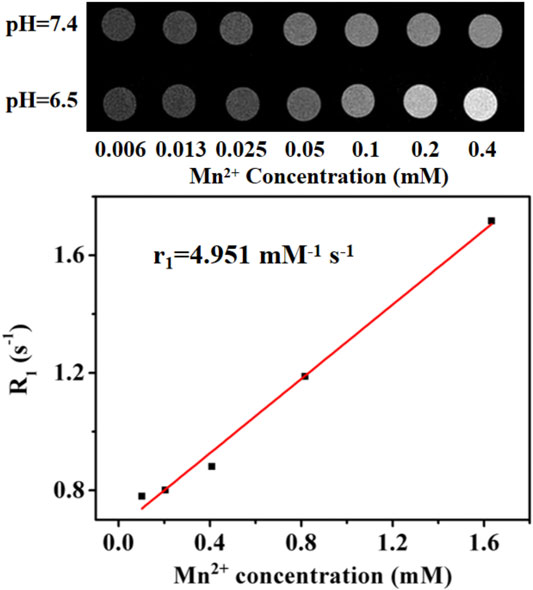

As shown in Figure 6, the MR signals are unchanged with the increase of MONs@PDA in the normal physiological microenvironment (pH 7.4), but the MR signals became stronger at the same concentration of MONs@PDA tumor microenvironment (pH 6.5 and 2 mM H2O2), with the longitudinal relaxation (r1) value of 4.951 mM−1 s−1. The results show that MONs@PDA could act as a tumor microenvironment responsive MRI contrast for highly sensitive and specific liver cancer diagnosis.

FIGURE 6. MRI images of MONs@PDA with increased Mn2+ content (0.006, 0.013, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4 mM) at different pH and T1 relaxation time.

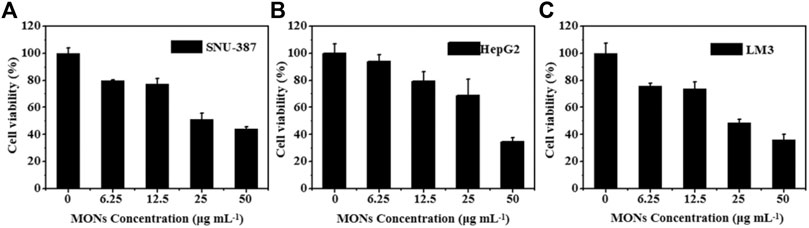

Encouraged by the good ROS generation capacity and photothermal properties, we further investigated the potential of MONs@PDA-ICG as a nanotheranostic agent for synergistic PTT and PDT in vitro. The LM3, HepG2, SNU-387 were chosen to assess the cytotoxicity of MONs@PDA by cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assay. As shown in Figure 7, after incubating with MONs@PDA with different concentrations (6.25–100 μg/ml) for 24 h, the cell viabilities were higher than 80% at 50 μg ml−1 for LM3, HepG2, and SNU-387, indicating their good biocompatibility. Then, the treatment effect of synergistic PTT and PDT was evaluated using LM3, HepG2, SNU-387. After irradiation with 808 nm NIR laser for 10 min, the cell viability of LM3, HepG2, SNU-387 cells was no more than 40% (Figure 8), displaying the highly efficient therapeutic efficacy of synergistic PTT and PDT for liver cancer.

FIGURE 8. The therapy effect in vitro. (A) SNU-387 (B) HepG2, and (C) LM3 were exposed to 808 nm irradiation for 10 min (1.3 W cm−2).

Conclusion

In summary, we successfully synthesized a nanotheranostic agent for tumor microenvironment responsive MRI and combinatorial PTT and PDT for liver cancer. The designed MONs@PDA-ICG worked as both a photosensitizer and photothermal agent under 808 nm NIR irradiation. Meanwhile, MONs@PDA-ICG can release oxygen and Mn2+ ions in tumor microenvironments. The oxygen produced, relieved the tumor hypoxia and further enhanced the treatment effect of PDT. In addition, the release of Mn2+ ions makes MONs@PDA-ICG serve as a tumor microenvironment responsive MRI contrast for highly sensitive and specific liver cancer diagnosis. This outstanding treatment effect was demonstrated by the representative liver cancer cells, including LM3, HepG2, SNU-387. These findings validate the conclusion that the nanotheranostic agent based on MONs@PDA has potential in future liver cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

XZ and YX designed experiments; YZ and MD carried out experiments; NX analyzed experimental results. YZ and YX wrote the manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by the project of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Disease Translational Medicine Platform Construction (2017F009).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Agostinis, P., Berg, K., Cengel, K. A., Foster, T. H., Girotti, A. W., Gollnick, S. O., et al. (2011). Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J. Clin. 61 (4), 250–281. doi:10.3322/caac.20114

Bañobre-López, M., García-Hevia, L., Cerqueira, M. F., Rivadulla, F., and Gallo, J. (2018). Tunable performance of manganese oxide nanostructures as MRI contrast agents. Chem. Eur. J. 24 (6), 1295–1303. doi:10.1002/chem.201704861

Bo, H., Gong, Z., Zhang, W., Li, X., Zeng, Y., Liao, Q., et al. (2015). Upregulated long non-coding RNA AFAP1-AS1 expression is associated with progression and poor prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget 6 (24), 20404–20418. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.4057

Cai, X., Zhu, Q., Zeng, Y., Zeng, Q., Chen, X., and Zhan, Y. (2019). Manganese oxide nanoparticles as MRI contrast agents in tumor multimodal imaging and therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 14, 8321–8344. doi:10.2147/IJN.S218085

Chen, Q., Feng, L., Liu, J., Zhu, W., Dong, Z., Wu, Y., et al. (2018). Intelligent albumin-MnO2 nanoparticles as pH-/H2 O2 -responsive dissociable nanocarriers to modulate tumor hypoxia for effective combination therapy. Adv. Mater. 30 (8), 1707414. doi:10.1002/adma.201707414

Dai, Y., Xu, C., Sun, X., and Chen, X. (2017). Nanoparticle design strategies for enhanced anticancer therapy by exploiting the tumour microenvironment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (12), 3830–3852. doi:10.1039/c6cs00592f

Ding, B., Zheng, P., Jiang, F., Zhao, Y., Wang, M., Chang, M., et al. (2020). MnO x nanospikes as nanoadjuvants and immunogenic cell death drugs with enhanced antitumor immunity and antimetastatic effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (38), 16381–16384. doi:10.1002/anie.202005111

Fan, W., Bu, W., Shen, B., He, Q., Cui, Z., Liu, Y., et al. (2015). Intelligent MnO2 nanosheets anchored with upconversion nanoprobes for concurrent pH-/H2O2-responsive UCL imaging and oxygen-elevated synergetic therapy. Adv. Mater. 27 (28), 4155–4161. doi:10.1002/adma.201405141

He, M., Chen, Y., Tao, C., Tian, Q., An, L., Lin, J., et al. (2019). Mn-porphyrin-based metal-organic framework with high longitudinal relaxivity for magnetic resonance imaging guidance and oxygen self-supplementing photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 11 (45), 41946–41956. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b15083

Janib, S. M., Moses, A. S., and MacKay, J. A. (2010). Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 62 (11), 1052–1063. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004

Kim, S. M., Im, G. H., Lee, D.-G., Lee, J. H., Lee, W. J., and Lee, I. S. (2013). Mn2+-doped silica nanoparticles for hepatocyte-targeted detection of liver cancer in T1-weighted MRI. Biomaterials 34 (35), 8941–8948. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.009

Lan, M., Zhao, S., Liu, W., Lee, C. S., Zhang, W., and Wang, P. (2019). Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8 (13), e1900132. doi:10.1002/adhm.201900132

Liu, J., Du, P., Liu, T., Córdova Wong, B. J., Wang, W., Ju, H., et al. (2019). A black phosphorus/manganese dioxide nanoplatform: oxygen self-supply monitoring, photodynamic therapy enhancement and feedback. Biomaterials 192, 179–188. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.018

Llovet, J. M., Schwartz, M., and Mazzaferro, V. (2005). Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 25 (2), 181–200. doi:10.1055/s-2005-871198

Llovet, J. M., Zucman-Rossi, J., Pikarsky, E., Sangro, B., Schwartz, M., Sherman, M., et al. (2016). Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16018. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.18

Luo, S., Zhang, E., Su, Y., Cheng, T., and Shi, C. (2011). A review of NIR dyes in cancer targeting and imaging. Biomaterials 32 (29), 7127–7138. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.024

Sahu, A., Kwon, I., and Tae, G. (2020). Improving cancer therapy through the nanomaterials-assisted alleviation of hypoxia. Biomaterials 228, 119578. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119578

Soares, P. I. P, Ferreira, I. M. M, Igreja, R. A. G. N, Novo, C. M. M, and Borges, J. P.M. R (2012). Application of hyperthermia for cancer treatment: recent patents review. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 7 (1), 64–73. doi:10.2174/157489212798358038

Trachootham, D., Alexandre, J., and Huang, P. (2009). Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8 (7), 579–591. doi:10.1038/nrd2803

Yuan, A., Tang, X., Qiu, X., Jiang, K., Wu, J., and Hu, Y. (2015). Activatable photodynamic destruction of cancer cells by NIR dye/photosensitizer loaded liposomes. Chem. Commun. (CAMB). 51 (16), 3340–3342. doi:10.1039/c4cc09689d

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, nanomaterials, photodynamic therapy, photothermal therapy, magnetic resonance imaging, manganese oxide

Citation: Zhu Y, Deng M, Xu N, Xie Y and Zhang X (2021) A Tumor Microenvironment Responsive Nanotheranostics Agent for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Synergistic Photodynamic Therapy/Photothermal Therapy of Liver Cancer. Front. Chem. 9:650899. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.650899

Received: 08 January 2021; Accepted: 09 February 2021;

Published: 07 April 2021.

Edited by:

Kelong Ai, Central South University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yunlu Dai, University of Macau, ChinaZhen Liu, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, China

Copyright © 2021 Zhu, Deng, Xu, Xie and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuewen Zhang, emhhbmd4d0BqbHUuZWR1LmNu; Yingjun Xie, eGlleno1NEAxNjMuY29t

Yuwan Zhu

Yuwan Zhu Mo Deng3

Mo Deng3 Yingjun Xie

Yingjun Xie Xuewen Zhang

Xuewen Zhang