- 1Organic Semiconductor Centre, Scottish Universities Physics Alliance (SUPA), School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St. Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom

- 2Organic Semiconductor Centre, EaStCHEM School of Chemistry, University of St. Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom

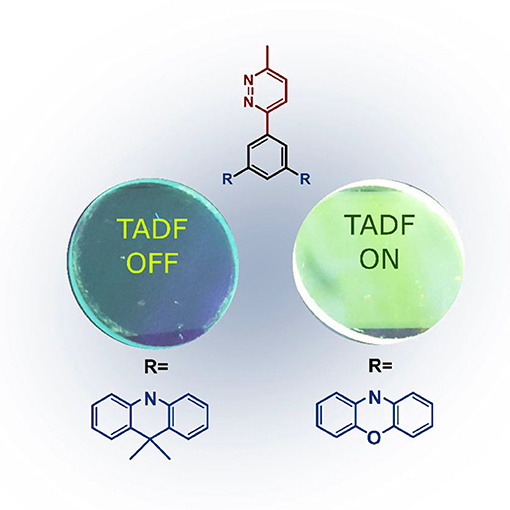

Three novel donor-acceptor molecules comprising the underexplored pyridazine (Pydz) acceptor moiety have been synthesized and their structural, electrochemical and photophysical properties thoroughly characterized. Combining Pydz with two phenoxazine donor units linked via a phenyl bridge in a meta configuration (dPXZMePydz) leads to high reverse intersystem crossing rate kRISC = 3.9 · 106 s−1 and fast thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) with <500 ns delayed emission lifetime. Efficient triplet harvesting via the TADF mechanism is demonstrated in OLEDs using dPXZMePydz as the emitter but does not occur for compounds bearing weaker donor units.

Graphical Abstract. Thin film luminecence under UV light of pyridazine-based emitters, dPXZMePydz (left) and dCzMePydz (right).

Introduction

Electroluminescence (EL) from organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) originates from the radiative decay of neutral excited states (excitons) formed by the recombination of holes and electrons. Spin statistics dictate that three quarters of the excitons created in working OLEDs are triplets. Since the ground state of most organic luminophores is singlet, considerable effort has been concentrated on development of materials that exhibit fast spin conversion from triplet to singlet states. The first breakthrough in EL efficiency was thus achieved by introducing organometallic phosphorescent emitters (Baldo et al., 1998; Adachi et al., 2001). The heavy atom effect in these materials enhances spin-orbit coupling, promoting phosphorescence with microsecond lifetime, and, importantly external quantum efficiencies (EQEs) that surpass the limit of 5% for fluorescent materials. However, the most commonly used organometallic complexes are based on iridium(III) and platinum(II) and these materials are not sustainable given their ultra-low abundance in the Earth's crust. While efficient and stable red and green phosphorescent OLEDs are now commercialized, and encouraging pure blue phosphorescent OLEDs were demonstrated recently (Lee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Pal et al., 2018), blue device stability remains an unresolved issue (Yang et al., 2015; Jacquemin and Escudero, 2017). For these reasons, alternative routes to harvest both singlet and triplet states using purely organic emitters via delayed fluorescence channels, namely, triplet-triplet annihilation (TTA) (Kondakov et al., 2009) and thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) (Uoyama et al., 2012; Wong and Zysman-Colman, 2017), are being hotly pursued. TADF is based on triplet up-conversion to the first excited singlet level via reverse intersystem crossing (rISC). For the rate of this process (krISC) to be sufficiently high to outcompete the non-radiative internal conversion of the triplet state, a small singlet-triplet splitting energy ΔEST is required, which is achieved in intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) states present in molecules composed of electron-donating (D) and electron-accepting (A) units. Concomitantly, high photoluminescence quantum yield (ΦPL) is needed in high performance emitters for OLEDs. Indeed, competitively efficient TADF OLEDs based on D-A emitter architectures have now been reported for all relevant display colors (Tao et al., 2014). An ongoing research effort is also aimed at addressing issues related to device stability and the link to the structure of the emitters. In particular, the design of emitters that show fast krISC and short delayed fluorescence lifetimes is desired in order to mitigate against bimolecular interactions, such as TTA and triplet-polaron annihilation. This is currently pursued via controlled molecular fine-tuning of the spatial separation and twist angles between D and A units, as well as D/A unit strength (Milián-Medina and Gierschner, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2013; Im et al., 2017).

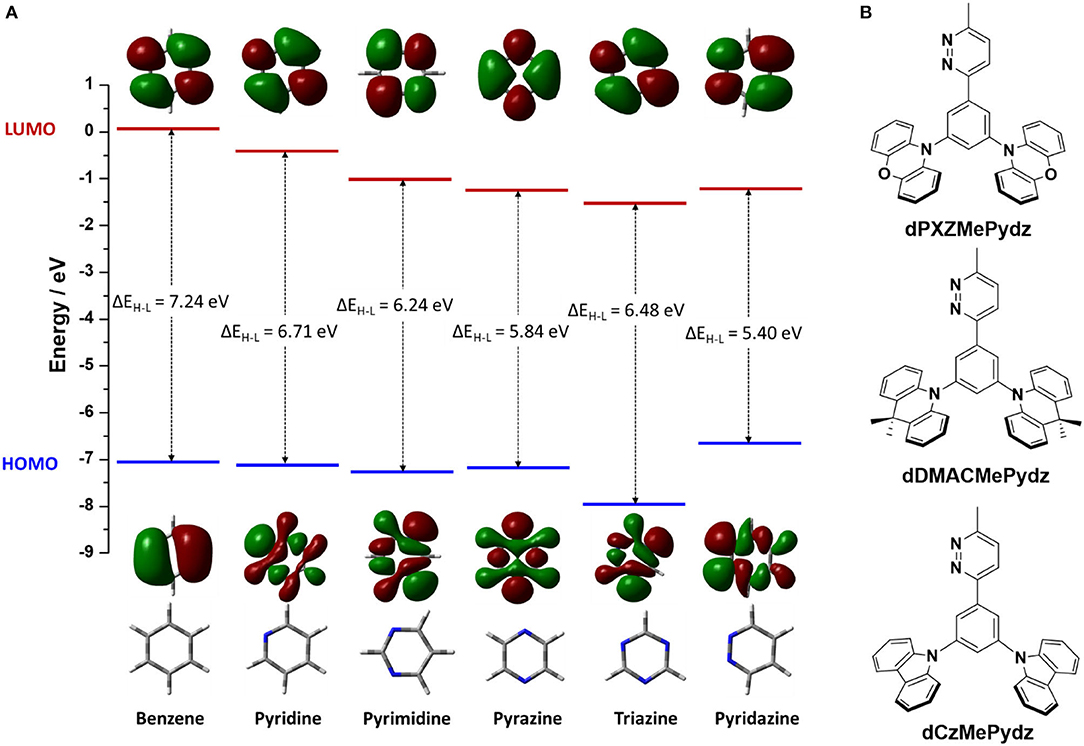

Among the N-heterocyclic electron-acceptors, 1,3,5-triazine is one of the most employed (Wong and Zysman-Colman, 2017; Huang et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Woo et al., 2019). Other heterocycles used in this role include pyridines (Rajamalli et al., 2017, 2018a,b, 2019), pyrimidines (Komatsu et al., 2016; Nakao et al., 2017; dos Santos et al., 2019), and pyrazines (Figure 1A) (dos Santos et al., 2019; Kato et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019). Missing from this family of heterocycles is pyridazine (Pydz), which is investigated in this work as an acceptor in three novel D-A compounds (Figure 1B). Pyridazine-based compounds have been employed as ligands in phosphorescent emitters (Guo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016), as well as hosts for phosphorescent OLEDs (Jia et al., 2019), and as fluorescent probes (Qu et al., 2020). To date, there are no examples of pyridazine-based TADF emitters used in OLEDs.

Figure 1. (A) Structure of benzene and other azines, together with their corresponding HOMO and LUMO electron density distributions (isovalue = 0.02) and energy levels, calculated at PBE0/6-31G(d,p) level in vacuum. (B) Chemical structures of compounds with pyridazine acceptor.

Results and Discussion

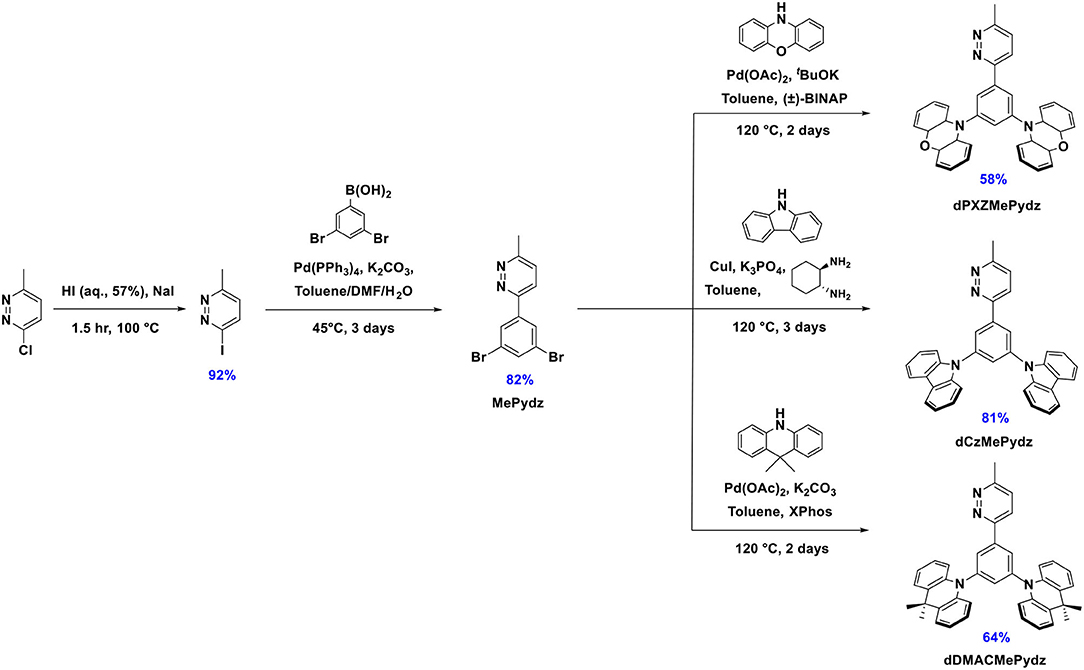

Synthesis

To evaluate the electron-accepting ability of pyridazine it is essential to consider the energy level of its lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Density functional theory (DFT) calculated LUMO levels of benzene and related N-heterocycles predict that pyridazine possesses a comparable LUMO level to those of triazine and pyrazine (Figure 1A) (Ortiz et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2017; Jin et al., 2019). Pyridazine possesses a more destabilized highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) as compared to other studied azines, thus yielding the smallest HOMO-LUMO gap, ΔEH−L. Substituted pyridazines are most easily synthesized at the three and six positions (i.e., ortho to the nitrogen atoms). We thus envisaged the three targeted emitters in Figure 1B containing a phenylene bridge, which was expected to induce a certain degree of N···H intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the Pydz and the phenylene and a co-planar conformation. Decoration of the phenylene with electron donors of different strength connected at the meta positions would strongly electronically decouple these groups from the Pydz acceptor, leading to potential TADF emitters.

Each of the three emitters in this study comprised a 3-methyl-pyridazine (MePydz) acceptor moiety linked by a phenylene bridge to two identical donor units disposed in a meta configuration with respect to the position of the acceptor (Figure 1B). The donor units chosen were phenoxazine (PXZ, compound dPXZMePydz), 9,9-dimethyl-9,10-dihydroacridine (DMAC, dDMACMePydz), and carbazole (Cz, dCzMePydz). By weakening the donor strength from PXZ to DMAC to Cz we expected to systematically shift the emission energy of the compounds toward the blue. Conjugation between donor and acceptor groups should be greatly reduced owing to their meta disposition about the central phenylene. As such, the exchange integral between the HOMO and the LUMO will be small, leading to a correspondingly small singlet-triplet energy gap, ΔEST, between the lowest singlet and triplet excited states, which is desired for an efficient TADF mechanism.

The synthesis of the three pyridazine-containing compounds is shown in Scheme 1. Key intermediate MePydz was prepared by Suzuki-Miyaura (Suzuki, 2005) cross-coupling reaction between 3-iodo-6-methylpyridazine and (3,5-dibromophenyl)boronic acid. Coupling of MePydz to PXZ, DMAC and Cz under either Buchwald-Hartwig (Forero-Cortés and Haydl, 2019) or modified Ullmann coupling (Antilla et al., 2004) conditions yielded the target materials dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively, in average to high yields. The chemical structures of the three derivatives were identified by a combination of 1H, 13C NMR spectroscopy (Supplementary Figures 1–8), high resolution mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figures 9–11) and elemental analysis. The compounds were purified by column chromatography, and purity was ascertained by HPLC (Supplementary Figures 12–14) and elemental analysis (Supplementary Figures 15–17).

Structural Characterization

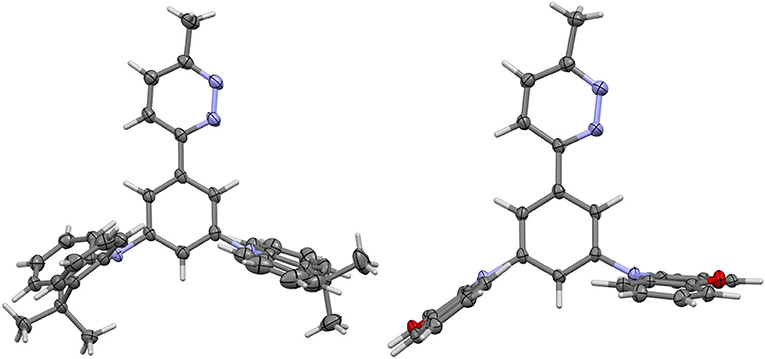

The structures of dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz were also confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). The structure of dPXZMePydz contained two independent molecules, one of which showed a similar pyrazine-phenylene geometry to dDMACMePydz, the other of which showed a different geometry. The dihedral angle between the pyridazine and the adjacent phenylene was found to be relatively small for dDMACMePydz and the equivalent dPXZMePydz (13.12 and 11.37°, respectively), although a much greater angle was seen for the second independent molecule in dPXZMePydz (42.63°), while in all cases, the mean planes of the donor groups are disposed close to orthogonal with respect to the plane of the phenylene bridge (66.41 – 80.86°). The DMAC donor anti to the diazine in dDMACMePydz was found to have a 38.51° pucker angle across its central ring, the other adopting a flat conformation (3.57° pucker). In contrast, none of the PXZ donors in dPXZMePydz showed the same extent of ring-pucker. In one independent molecule the diazine-facing PXZ adopted a flatter conformation than the anti donor group (6.12 vs. 14.11°), while in the second, the diazine-facing PXZ was more puckered than the anti donor (11.88 vs. 4.88°). The other significant geometric difference between the structures is in the degree of pyramidalisation of the nitrogen of the donor groups. In dDMACMePydz both donor nitrogens showed similar slight degrees of pyramidalisation (Cphenylene-N···CMe2 169.00 and 171.82°), but in dPXZMePydz each independent molecule showed different patterns of nitrogen pyramidalisation. One of these showed a more pyramidal nitrogen in the anti donor group (Cphenylene-N···O 160.52 and 179.51, for anti and syn donors groups, respectively), whereas the other showed a more pyramidal nitrogen in the syn donor group (Cphenylene···N···O 174.46 and 155.26, for anti and syn donors groups, respectively).

Figure 2. Thermal ellipsoid plots of the crystal structures of (left) dDMACMePydz and (right) one independent molecule of dPXZMePydz. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Theoretical Calculations

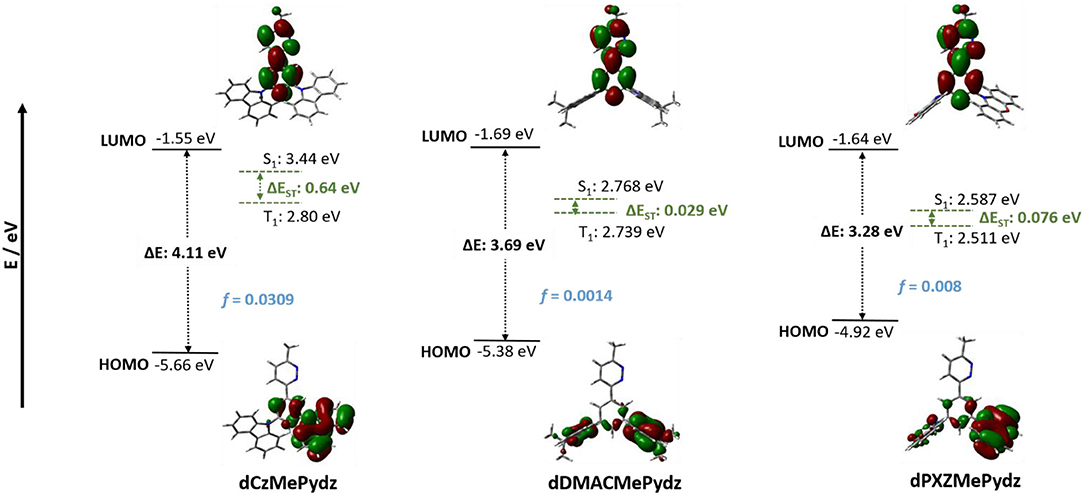

DFT calculated energies of the first excited singlet and triplet states, S1 and T1, respectively, and the HOMO and LUMO levels for the three compounds are shown in Figure 3 along with the electron-density distribution of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals. The HOMOs for dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz are localized on the donor moieties with only a minor contribution associated with the phenylene bridge, while for dCzMePydz the HOMO is delocalized over the phenylene bridge and one of the two carbazole groups. The multi-donor design should lead to a degeneracy of frontier orbitals. This is evidenced by the HOMO-1 being close in energy (~70–200 meV) to HOMO in each of the compounds (see Supplementary Figure 19). The HOMO levels reflect the strength of the donor moieties with values of −4.92, −5.38, and −5.66 eV for dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. The LUMOs for all three compounds are delocalized along the MePydz acceptor and phenylene bridge. The trend in LUMO energies mirrors that observed for the HOMO levels, but the influence of the donor on the LUMO level is significantly attenuated, with LUMO levels of −1.64, −1.69, and −1.55 eV for dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. The ΔEH−L values thus increase from 3.28 to 3.69 to 4.11 eV for dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. The Tamm-Dancoff approximation to time-dependent DFT calculations predict the transition from the ground state to the lowest excited state (S0-S1) to have ICT character for all three molecules. The S0-T1 transitions of dDMACMePydz and dPXZMePydz are likewise CT in nature, while the S0-T1 transition of dCzMePydz possesses local exciton (LE) character within the acceptor moiety. The calculated energies and oscillator strengths for the transitions from ground state to S1,2 and T1,2,3,4 levels are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. For dPXZMePydz, the S1 state is at 2.58 eV, while it increases in energy to 2.77 eV and 3.44 eV for dDMACMePydz and dCzMePydz, respectively. Thus, as expected, a blue-shift in emission is predicted with the decreasing donor unit strength. The frontier molecular orbitals of dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz are well-separated. This is reflected in the small calculated oscillator strengths (f = 8.0·10−3 and 1.4·10−3, respectively) as well as small singlet-triplet splitting energies (ΔEST = 76 and 29 meV, respectively). On the other hand, there is significant HOMO-LUMO overlap in dCzMePydz, which is reflected in much larger f of 3.1·10−2 and large ΔEST of 635 meV. Thus, this latter compound would not be expected to exhibit efficient TADF while the other two emitters would. The T2 and T3 states of dPXZMePydz are energetically very close to the S2 state (ΔES2T2 = 41 meV and ΔES2T3 = 9 meV, respectively, see Supplementary Figure 20, Supplementary Table 2). For dDMACMePydz there is a similar alignment of higher lying singlet and triplet excited states (ΔES1T2 = −35 meV, ΔES2T3 = 33 meV), while for dCzMePydz only T4 is close to S1 (ΔES1T4 = −15 meV). However, it is unlikely that dCzMePydz would undergo triplet exciton harvesting from T4 since internal conversion proceeding via T3 and T2 is highly likely to trap triplet excitons in the T1 state.

Figure 3. Frontier molecular orbitals (isovalue = 0.02) and corresponding energy values calculated at PBE0/6-31G(d,p) level in vacuum.

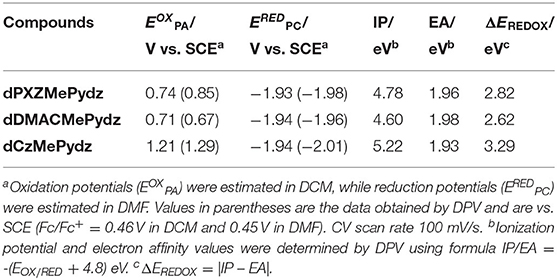

Electrochemistry

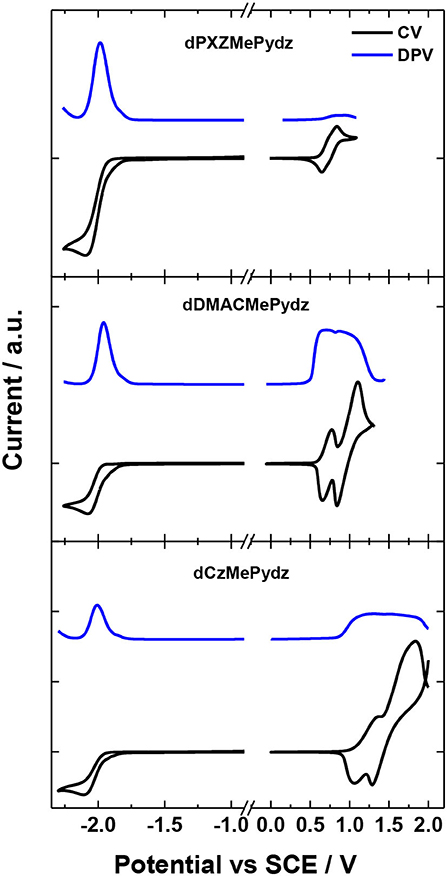

Figure 4 and Table 1 summarize the electrochemical characterization of the compounds. Cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry (CV and DPV, respectively) were employed in order to elucidate the energy levels of the studied materials. The oxidation potentials were 0.74 V, 0.71 V, and 1.21 V for the dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. Only dPXZMePydz demonstrated reversible oxidation, while other two compounds show quasi-reversible oxidation. As expected, the use of the weaker Cz electron donor in dCzMePydz resulted in a significantly more anodic oxidation potential, which is consistent with oxidation of other carbazole-based emitters (Kukhta et al., 2017). The for dDMACMePydz is cathodically shifted by only 0.03 V compared to that of dPXZMePydz, thereby indicating that within these emitters DMAC and PXZ possess comparable donating strength. All three compounds demonstrated almost identical reduction potentials with ERED values of −1.93 V, −1.94 V, and −1.94 V for the dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. Ionization potential and electron affinity values calculated based on oxidation and reduction potentials obtained from the DPV experiments follow the same trends. Expectedly, the HOMO level is destabilized with increasing strength of the donor with ionization potential values of 5.22 eV for dCzMePydz, 4.60 eV for dDMACMePydz and 4.78 eV for dPXZMePydz. The nature of the donor has no notable effect on the LUMO levels, with electron affinity values of 1.96 eV, 1.98 eV, and 1.93 eV for dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz, respectively. These results indicate essentially no electronic coupling between the donor and acceptor moieties. As a result, the electrochemical bandgap is systematically increased as a function of weakening donor strength along the DMAC to PXZ to Cz.

Figure 4. CV and DPV curves of dPXZMePydz, dDMACMePydz, and dCzMePydz. Oxidation measured in DCM and reduction in DMF (scan rate: 0.03 V/s).

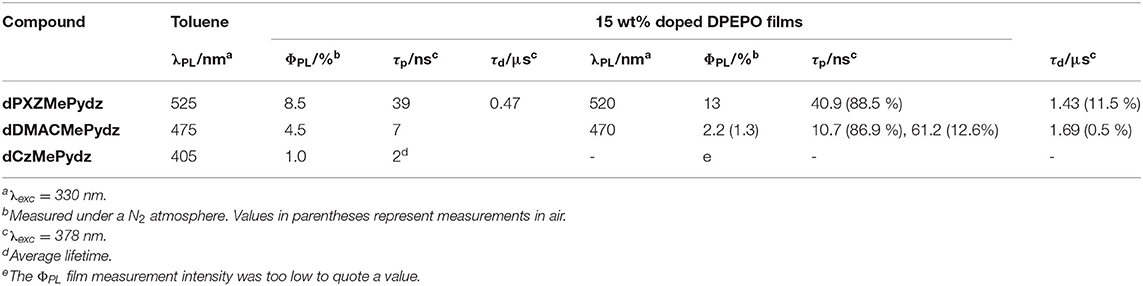

Photophysics

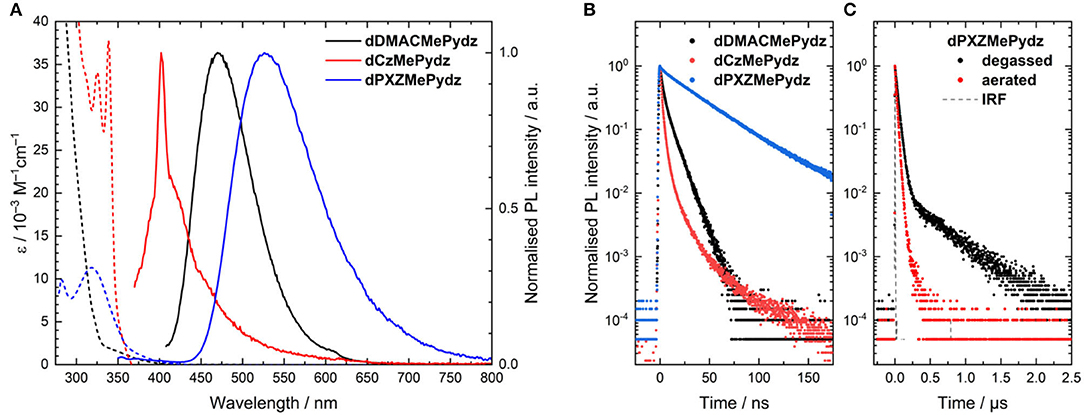

The absorption spectra in toluene are shown in Figure 5. All spectra resemble those of the donor units used, with the absorption spectrum of dPXZMePydz having a more notable lowest energy band located at 370–450 nm. A hypsochromic shift in the absorption onset is observed (λabs = 445 nm in dPXZMePydz, λabs = 415 nm for dDMACMePydz, and λabs = 360 nm for dCzMePydz). Weak and structureless lower energy absorption bands are attributed to the ICT transition between the D and A units, in line with the trends observed in theoretically simulated absorption spectra (Supplementary Figure 18). Predicted absorption spectra for dDMACMePydz and dPXZMePydz contain low energy bands located between 400 nm and 480 nm, which are composed of S0−1,2 excitations, which are of the same ICT character, just involving the other donor (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 19). In the case of dCzMePydz, the S0−1,2 excitations are also of ICT character; however, they are in competition with similar energy local excitations (S0−3) in the acceptor moiety.

Figure 5. (A) Solution absorption (dashed lines) and emission spectra (solid lines) of the pyridazine-based compounds in toluene (λexc = 300 nm for dDMACMePydz, λexc = 360 nm for dCzMePydz, λexc = 315 nm for dPXZMePydz). Peak at 400 nm in emission spectra of dCzMePydz is an instrument artifact; (B) Time resolved photoluminescence spectra in degassed toluene (λexc = 378 nm); (C) Time resolved photoluminescence of dPXZMePydz in aerated and degassed toluene (λexc = 378 nm) at room temperature.

The steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra in toluene (Figure 5A) also show the same trend as that found in the absorption spectra, with a progressive red-shift in the emission maxima as a function of Cz>DMAC>PXZ (Table 2). The red-shift of emission is accompanied by an increase in ΦPL. dCzMePydz exhibits a ΦPL value of 1.0%, compared to 4.5% for dDMACMePydz and 8.5% for dPXZMePydz. The time-resolved PL of dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz (Figure 5B) show a mono-exponential prompt component with lifetimes of τp = 39 ns and 7 ns, respectively. The prompt component of the PL of dCzMePydz has a multiexponential form with an average lifetime of τp = 2 ns. The transient PL of dPXZMePydz shows a remarkably fast delayed emission with a lifetime of τd = 0.47 μs in degassed solution. Such a short delayed emission lifetime of dPXZMePydz is a result of modular design strategy. Use of meta disposition of D and A moieties around the central phenylene bridge was previously shown to produce emitters showing high ICT character for their S1 and T1 states, small ΔEST, as well as short τd and fast krISC (Wong et al., 2018; Kukhta et al., 2019). The delayed component is quenched upon exposing the solution to air, thus implicating accessible triplet states and corroborating that emission in this compound proceeds via TADF. For both dDMACMePydz and dCzMePydz no delayed PL component could be detected in toluene.

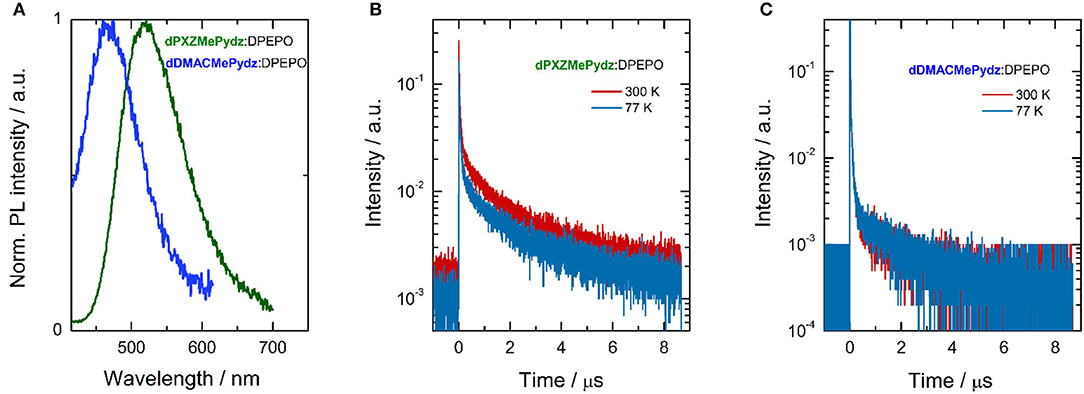

We next assessed the photophysical properties of the emitters in a polar, wide band-gap host, bis[2-(diphenylphosphino)phenyl]ether oxide (DPEPO). Doped thin films of the emitters in DPEPO were produced via vacuum deposition. dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz were investigated only, due to their higher ΦPL values in solution and their greater likelihood of being TADF materials based on the DFT calculations. The optimal emitter concentration was found to be around 15 wt%. Slightly blue-shifted emission (λPL = 520 and 470 nm for dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz, respectively) was recorded compared to those measured in toluene (Figure 6A). dPXZMePydz exhibited a slightly higher ΦPL of 11% in DPEPO film while dDMACMePydz showed a slightly lower ΦPL of 2%. The blue-shift of the emission and changes in ΦPL in thin films may be attributed to the ICT state sensitivity to the different polarity of the environment as well as different molecular conformations in the solid state. For dPXZMePydz, prompt (τp = 41 ns, 88.5% weighting) and delayed components (τd = 1.43 μs, 11.5% weighting) were recorded in time-resolved PL decay experiment. Slight ΦPL sensitivity to air and an appreciable delayed component, which decreases upon cooling to 77 K [Figure 6B, τp = 47.6 ns (89.8%), τd = 1.58 μs (10.2%)] indicate that TADF is occurring in dPXZMePydz. A high krISC value of 3.9 · 106 s−1 and triplet state up-conversion yield ΦrISC close to unity was estimated from the thin film photophysics (Dias et al., 2017) (Supplementary Table 3). On the other hand, dDMACMePydz exhibited a PL transient dominated by multiple prompt components [τp1 = 10.7 ns (86.9%), and τp2 = 61.2 ns (12.6%)] and only a weak delayed fluorescence signal [τd = 1.69 μs (0.5 %)] despite the calculated ΔEST of both compounds being similar (Figure 6C). In the case of dDMACMePydz, the higher-lying T2 triplet state should be taken into account (Supplementary Figure 22) as higher energy triplet states are believed to play a crucial role in facilitating TADF mechanism (Etherington et al., 2016; Kobayashi et al., 2017; Noda et al., 2019). Indeed, a very high krISC = 1.4 · 107 s−1 was estimated in dDMACMePydz assuming that ISC and rISC occur predominantly via T2 (Tsuchiya et al., 2020). However, rISC is outcompeted by fast internal conversion to T1 and a low probability of endothermic up-conversion to T2, leading to negligible ΦrISC ≈ 0.01 (Supplementary Table 4). The ΔESTs were measured in PMMA films doped with 10 wt% of dDMACMePydz and dPXZMePydz (Supplementary Figure 21) and the values were found to be 241 nm and 53 meV, respectively. Changing the host material from PMMA to DPEPO (15 wt% doping) resulted in a further reduction of ΔEST due to the increased polarity of the host, which preferentially stabilizes the 1CT state. The ΔEST values for dDMACMePydz and dPXZMePydz in DPEPO were found to decrease to 25 nm and 15 meV, respectively.

Figure 6. Steady-state and time-resolved photoluminescence of thin films; (A) integrated emission spectra (λexc = 330 nm); time-resolved PL (λexc = 378 nm) of (B) dPXZMePydz:DPEPO (15 wt%), and (C) dDMACMePydz:DPEPO (15 wt%) at 300 K (red solid line) and 77 K (blue solid line).

In summary, the combination of DFT calculations and PL studies indicate that all three compounds exhibit a significant degree of intersystem crossing as a result of their D-A molecular design. S0−1,2,3 excitations dominate the absorption spectrum of dCzMePydz and have the highest oscillator strengths among the series. We reason about the fast intersystem crossing in dCzMePydz based on a combination of theoretical and experimental evidence. According to DFT calculations this compound should show the strongest PL emission since its oscillator strength for S0−1 transition is an order of magnitude larger than in dPXZMePydz and dDMACMePydz compounds. This is also corroborated with the absorption spectra (Figure 5) where the low energy absorption of dCzMePydz exhibits the highest molar extinction coefficient values. However, PL experiments show the opposite trend, dCzMePydz exhibits negligible luminescence signal and is the poorest emitter among the series. This must be due to higher non-radiative decay in this compound. To explain this, there must be a different excited state deactivation mechanism other than via the singlet channel. DFT calculations provide a plausible compelling explanation that intersystem crossing to a higher energy triplet state T4 is the most likely transition due to its close proximity to S1 (Supplementary Figure 20C) and the large exchange integral values due to larger overlap of the corresponding orbitals. RISC is unlikely to occur as it is outcompeted by internal conversion. The fast krISC = 3.9 · 106 s−1 of dPXZMePydz is a result of the small ΔEST, which leads to efficient and fast delayed emission (<500 ns in toluene). Although a similarly small ΔEST is calculated for dDMACMePydz, no delayed fluorescence is observed, likely due to additional non-radiative decay channel similar to the case of dCzMePydz (Supplementary Figure 20B).

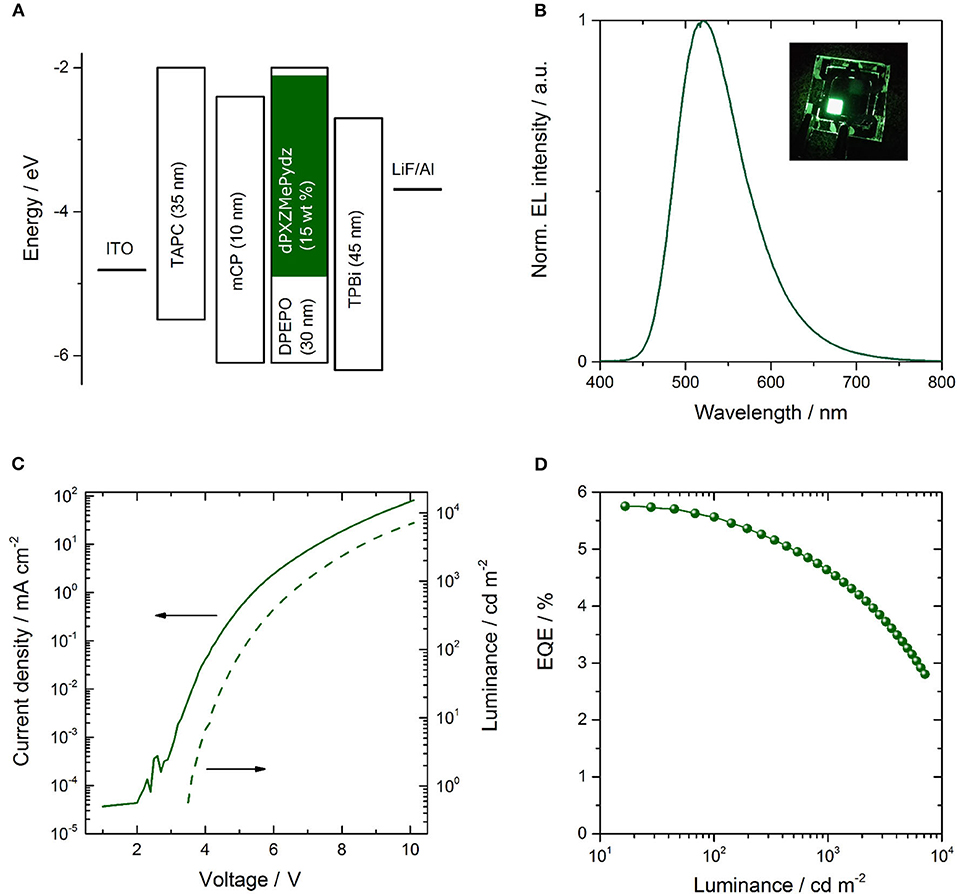

Electroluminescence

Due to the presence of TADF in dPXZMePydz and this compound having the highest ΦPL of the three compounds, this emitter was incorporated into an OLED structure (Figure 7A). The device structure was: ITO (90 nm)/TAPC (35 nm)/mCP (10 nm)/ dPXZMePydz:DPEPO (15 wt%, 30 nm)/TPBi (45 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (100 nm), where 4,4′-cyclohexylidene-bis[N,N-bis(4-methylphenyl)benzenamine] (TAPC) is the hole transporting material, 1,3-bis(carbazol-9-yl)benzene (mCP) acts as an electron blocker, and 1,3,5-tris(1-phenyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)benzene (TPBi) is the electron transport layer. The DPEPO host is electron-transporting and has a high triplet energy (ET = 2.9 eV). The mCP interlayer near the expected exciton recombination position also serves to prevent emitter triplet diffusion and quenching. The resulting EL spectrum, current-voltage-luminance and external quantum efficiency (EQE)-luminance characteristics are shown in Figures 7B–D. The OLED exhibits green emission with CIE coordinates of (0.30,0.55) and EQEmax of 5.8%. The device performance is summarized in Table 3.

Figure 7. Performance of OLED incorporating dPXZMePydz emitter; (A) functional layer sequence, layer thicknesses and respective energy levels; (B) electroluminescence spectrum, (C) current-voltage-luminance characteristics, and (D) external quantum efficiency (EQE) vs. luminance.

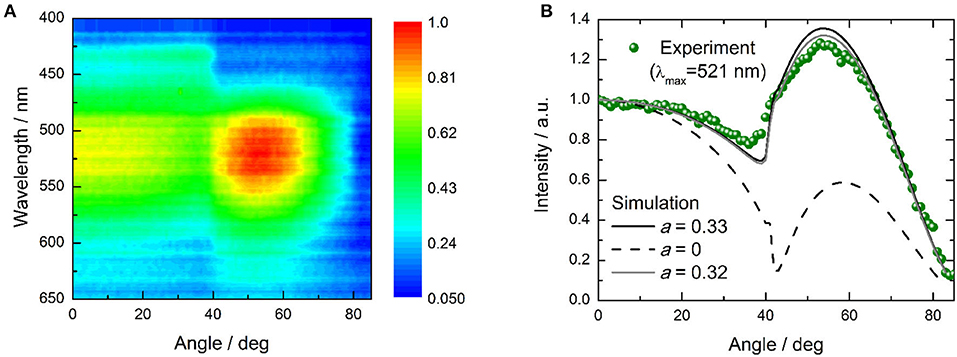

The OLED performance is higher than the theoretical spin statistic limit for a fluorescent OLED. Thus, triplet harvesting clearly occurs during electroluminescence. Assuming that 100% triplets are harvested, the outcoupling efficiency is 0.2–0.3, and taking into account ΦPL of the dPXZMePydz:DPEPO (15 wt%) film, the expected EQE of the OLED is 2.6–3.9%, indicating that the recorded EQEs are higher than would be expected even for effective triplet harvesting by TADF. One possibility to explain this is a light outcoupling enhancement due to a deviation from an isotropic emitter orientation to a more horizontal orientation (Liehm et al., 2012; Kim and Kim, 2018). To quantify the effect of the emitter orientation in dPXZMePydz:DPEPO films, angular polarized PL experiments were carried out (Figure 8A). The experimental data were then fitted to the optical model with the orientation factor a as the fitting parameter as described in Ref. (Graf et al., 2014). The isotropic case is represented by a = 0.33 and fully horizontal alignment results in a = 0. However, the actual average emitter orientation was found to be very close to the isotropic case (a = 0.32, Figure 8B), thus ruling out the explanation of a preferential orientation of the transition dipole moment. Weak microcavity effects could be partially responsible for the higher than expected EQE. A further contribution might arise from differences between the PL and EL processes. In particular, in EL charges could trap on the emitter, leading to direct excitation of the emitter. By contrast, in PL some of the excitation light may be absorbed by the DPEPO host and if energy transfer to the emitter is not perfectly efficient, this would lead to a loss in PL that is not present in EL.

Figure 8. Polarized angular emission spectroscopy characterization of dPXZMePydz:DPEPO (15 wt%) film; (A) angular dependence of the photoluminescence spectrum (λexc = 365 nm); (B) angular dependence of emission intensity at peak emission wavelength (λ = 521 nm, green disks), and simulated angular dependence for the case of horizontal (a = 0, black dashed line) and isotropic (a = 0.33, black solid line) emitter orientation as well as for the closest match to the experimental data which was achieved with a = 0.32 (gray solid line).

Conclusions

Herein, pyridazine was explored within three newly synthesized D-A compounds with varying electron-donating strength. Photophysical and DFT calculations revealed strong intersystem crossing occurring in these purely organic compounds. Compounds dCzMePydz and dDMACMePydz, comprising carbazole and acridine donors, respectively, were poorly emissive and exhibited pure fluorescent emission in the blue and blue-green spectral regions. On the other hand, combining Pydz with phenoxazine resulted in emitter dPXZMePydz with moderate green luminescence with ΦPL of 8.5% and a fast delayed emission lifetime of 470 ns in toluene. Experiments in aerated and degassed solutions confirmed TADF being the mechanism responsible for the observed delayed emission. Upon deposition of a thin film containing dPXZMePydz, ΦPL increased to 10.9% with an estimated high reverse intersystem crossing rate krISC = 3.9 · 106 s−1 and a small singlet-triplet splitting value ΔEST = 86 meV, which was corroborated by TDA-DFT calculations. Theoretical calculations also revealed low energy intermediate triplet states lying in the vicinity of S1 and T1 in dCzMePydz and dDMACMePydz compounds. Finally, OLED comprising dPXZMePydz in DPEPO host at an optimal concentration of 15 wt% were fabricated via thermal evaporation in vacuum. These OLEDs demonstrated EQEmax over 5.8%, confirming efficient triplet utilization in the device via TADF. Our results suggest that some pyridazine-containing molecules are of interest as an approach to TADF molecules with high rates of rISC.

Data Availability Statement

The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/3f2695c7-e6d5-4e11-a0b1-dcf1a54d4bb5.

Author Contributions

SK co-wrote the manuscript, undertook some of the photophysical measurements, undertook some of the analysis of the data, and fabricated all of the devices. TM co-wrote the manuscript, conducted the DFT calculations, and undertook some of the analysis of the data. SD co-wrote the manuscript, undertook some of the photophysical measurements, and analysis of the data. GC synthesized the compounds, conducted the electrochemical measurements, and some of the photophysical measurements. EA and CK co-wrote the manuscript and undertook some of the orientation measurements. DC co-wrote the manuscript and solved the X-ray structures. AS supervised DC and funded the acquisition of the XRD equipment used in this study. MG co-wrote the manuscript, undertook some of the analysis of the orientation measurements, and supervised EA and CK. IDWS co-managed the project, co-wrote the manuscript, undertook some of the analysis of the data, supervised SK, and co-supervised SD. EZ-C conceived of the molecular design, co-managed the project, co-wrote the manuscript, undertook some of the analysis of the data and supervised TM, GC, and co-supervised SD. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC for financial support (grants EP/P010482/1, EP/R035164/1, and EP/L017008/1). We thank the EPSRC UK National Mass Spectrometry Facility at Swansea University for analytical services. CK acknowledges support from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1A6A3A03012331).

Instrumentation details, synthesis, and chemical characterization (NMR spectra, HRMS, elemental analysis reports, HPLC chromatograms), crystal structure information (CCDC: 2002948-2002949), computational details, photophysical properties as well as device characterization are available in supporting information.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.572862/full#supplementary-material

References

Adachi, C., Baldo, M. A., Thompson, M. E., and Forrest, S. R. (2001). Nearly 100% internal phosphorescence efficiency in an organic light-emitting device. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 5048–5051. doi: 10.1063/1.1409582

Antilla, J. C., Baskin, J. M., Barder, T. E., and Buchwald, S. L. (2004). Copper-Diamine-Catalyzed N -Arylation of Pyrroles, Pyrazoles, Indazoles, Imidazoles, and Triazoles. J. Org. Chem. 69, 5578–5587. doi: 10.1021/jo049658b

Baldo, M. A., O'Brien, D. F., You, Y., Shoustikov, A., Sibley, S., Thompson, M. E., et al. (1998). Highly efficient phosphorescent emission from organic electroluminescent devices. Nature 395, 151–4. doi: 10.1038/25954

Dias, F. B., Penfold, T. J., and Monkman, A. P. (2017). Photophysics of thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 5:012001. doi: 10.1088/2050-6120/aa537e

dos Santos, P. L., Chen, D., Rajamalli, P., Matulaitis, T., Cordes, D. B., Slawin, A. M. Z., et al. (2019). Use of pyrimidine and pyrazine bridges as a design strategy to improve the performance of thermally activated delayed fluorescence organic light emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 45171–45179. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b16952

Etherington, M. K., Gibson, J., Higginbotham, H. F., Penfold, T. J., and Monkman, A. P. (2016). Revealing the spin-vibronic coupling mechanism of thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Commun. 7:13680. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13680

Forero-Cortés, P. A., and Haydl, A. M. (2019). The 25th anniversary of the buchwald-hartwig amination: development, applications, and outlook. Org. Process Res. Dev. 23, 1478–1483. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00161

Graf, A., Liehm, P., Murawski, C., Hofmann, S., Leo, K., and Gather, M. C. (2014). Correlating the transition dipole moment orientation of phosphorescent emitter molecules in OLEDs with basic material properties. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 10298–10304. doi: 10.1039/C4TC00997E

Guo, L. Y., Zhang, X. L., Wang, H. S., Liu, C., Li, Z. G., Liao, Z. J., et al. (2015). New homoleptic iridium complexes with CN=N type ligand for high efficiency orange and single emissive-layer white OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 5412–5418. doi: 10.1039/C5TC00458F

Huang, W., Einzinger, M., Maurano, A., Zhu, T., Tiepelt, J., Yu, C., et al. (2019). Large increase in external quantum efficiency by dihedral angle tuning in a sky-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7:1900476. doi: 10.1002/adom.201900476

Im, Y., Kim, M., Cho, Y. J., Seo, J. A., Yook, K. S., and Lee, J. Y. (2017). Molecular design strategy of organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Chem. Mater. 29, 1946–1963. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b05324

Jacquemin, D., and Escudero, D. (2017). The short device lifetimes of blue PhOLEDs: Insights into the photostability of blue Ir(III) complexes. Chem. Sci. 8, 7844–7850. doi: 10.1039/C7SC03905K

Jia, B., Lian, H., Sun, T., Wei, J., Yang, J., Zhou, H., et al. (2019). New bipolar host materials based on methyl substituted pyridazine for high-performance green and red phosphorescent OLEDs. Dye Pigment. 168, 212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.04.058

Jin, J., Long, G., Gao, Y., Zhang, J., Ou, C., Zhu, C., et al. (2019). Supramolecular design of donor-acceptor complexes via heteroatom replacement toward structure and electrical transporting property tailoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 1109–1116. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b16561

Kato, Y., Sasabe, H., Hayasaka, Y., Watanabe, Y., Arai, H., and Kido, J. (2019). A sky blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter to achieve efficient white light emission through in situ metal complex formation. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 3146–3149. doi: 10.1039/C8TC06041J

Kim, K. H., and Kim, J. J. (2018). Origin and control of orientation of phosphorescent and TADF dyes for high-efficiency OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 30:1705600. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705600

Kobayashi, T., Niwa, A., Takaki, K., Haseyama, S., Nagase, T., Goushi, K., et al. (2017). Contributions of a higher triplet excited state to the emission properties of a thermally activated delayed-fluorescence emitter. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7:034002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.7.034002

Komatsu, R., Sasabe, H., Seino, Y., Nakao, K., and Kido, J. (2016). Light-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent emitters realizing a high external quantum efficiency of 25% and unprecedented low drive voltages in OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 2274–2278. doi: 10.1039/C5TC04057D

Kondakov, D. Y., Pawlik, T. D., Hatwar, T. K., and Spindler, J. P. (2009). Triplet annihilation exceeding spin statistical limit in highly efficient fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 106:124510. doi: 10.1063/1.3273407

Kukhta, N. A., Higginbotham, H. F., Matulaitis, T., Danos, A., Bismillah, A. N., Haase, N., et al. (2019). Revealing resonance effects and intramolecular dipole interactions in the positional isomers of benzonitrile-core thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 9184–9194. doi: 10.1039/C9TC02742D

Kukhta, N. A., Matulaitis, T., Volyniuk, D., Ivaniuk, K., Turyk, P., Stakhira, P., et al. (2017). Deep-blue high-efficiency TTA OLED using Para - and meta-conjugated cyanotriphenylbenzene and carbazole derivatives as emitter and host. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 6199–6205. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02867

Lee, J., Chen, H. F., Batagoda, T., Coburn, C., Djurovich, P. I., Thompson, M. E., et al. (2016). Deep-blue high-efficiency TTA OLED using Para - and meta-conjugated cyanotriphenylbenzene and carbazole derivatives as emitter and host. Nat. Mater. 15, 92–98. doi: 10.1038/nmat4446

Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhao, Z., Wang, L., Yang, H., Chang, Q., et al. (2018). Deep blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes with CIE y value of 0.11 and external quantum efficiency up to 22.5%. Adv. Mater. 30:1705005. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705005

Liehm, P., Murawski, C., Furno, M., Lüssem, B., Leo, K., and Gather, M. C. (2012). Comparing the emissive dipole orientation of two similar phosphorescent green emitter molecules in highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101:253304. doi: 10.1063/1.4773188

Liu, J., Zhou, K., Wang, D., Deng, C., Duan, K., Ai, Q., et al. (2019). Pyrazine-based blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials: combine small singlet-triplet splitting with large fluorescence rate. Front. Chem. 7:312. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00312

Liu, S., Zhang, X., Ou, C., Wang, S., Yang, X., Zhou, X., et al. (2017). Structure-property study on two new D-A type materials comprising pyridazine moiety and the OLED application as host. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 26242–26251. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b04859

Milián-Medina, B., and Gierschner, J. (2012). Computational design of low singlet-triplet gap all-organic molecules for OLED application. Org. Electron. 13, 985–991. doi: 10.1016/j.orgel.2012.02.010

Nakao, K., Sasabe, H., Komatsu, R., Hayasaka, Y., Ohsawa, T., and Kido, J. (2017). Significant enhancement of blue OLED performances through molecular engineering of pyrimidine-based emitter. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5:1600843. doi: 10.1002/adom.201600843

Noda, H., Chen, X. K., Nakanotani, H., Hosokai, T., Miyajima, M., Notsuka, N., et al. (2019). Critical role of intermediate electronic states for spin-flip processes in charge-transfer-type organic molecules with multiple donors and acceptors. Nat. Mater. 18, 1084–1090. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0465-6

Ortiz, R. P., Casado, J., Hernández, V., Navarrete, J. T. L., Letizia, J. A., Ratner, M. A., et al. (2009). Thiophene-diazine molecular semiconductors: synthesis, structural, electrochemical, optical, and electronic structural properties; implementation in organic field-effect transistors. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 5023–5039. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802424

Pal, A. K., Krotkus, S., Fontani, M., Mackenzie, C. F. R., Cordes, D. B., Slawin, A. M. Z., et al. (2018). High-efficiency deep-blue-emitting organic light-emitting diodes based on iridium(III) carbene complexes. Adv. Mater. 30:1804231. doi: 10.1002/adma.201804231

Qu, Y., Pander, P., Vybornyi, O., Vasylieva, M., Guillot, R., Miomandre, F., et al. (2020). Donor-acceptor 1,2,4,5-tetrazines prepared by the buchwald-hartwig cross-coupling reaction and their photoluminescence turn-on property by inverse electron demand diels-alder reaction. J. Org. Chem. 85, 3407–3416. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02817

Rajamalli, P., Chen, D., Li, W., Samuel, I. D. W., Cordes, D. B., Slawin, A. M. Z., et al. (2019). Enhanced thermally activated delayed fluorescence through bridge modification in sulfone-based emitters employed in deep blue organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 6664–6671. doi: 10.1039/C9TC01498E

Rajamalli, P., Martir, D. R., and Zysman-Colman, E. (2018a). Molecular design strategy for a two-component gel based on a thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 649–654. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.7b00161

Rajamalli, P., Rota Martir, D., and Zysman-Colman, E. (2018b). Pyridine-functionalized carbazole donor and benzophenone acceptor design for thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters in blue organic light-emitting diodes. J. Photonics Energy 8:032106. doi: 10.1117/1.JPE.8.032106

Rajamalli, P., Senthilkumar, N., Huang, P. Y., Ren-Wu, C. C., Lin, H. W., and Cheng, C. H. (2017). New molecular design concurrently providing superior pure blue, thermally activated delayed fluorescence and optical out-coupling efficiencies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10948–10951. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03848

Sharma, N., Spuling, E., Mattern, C. M., Li, W., Fuhr, O., Tsuchiya, Y., et al. (2019). Turn on of sky-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence and circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) via increased torsion by a bulky carbazolophane donor. Chem. Sci. 10, 6689–6696. doi: 10.1039/C9SC01821B

Tanaka, H., Shizu, K., Nakanotani, H., and Adachi, C. (2013). Twisted intramolecular charge transfer state for long-wavelength thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Chem. Mater. 25, 3766–3771. doi: 10.1021/cm402428a

Tao, Y., Yuan, K., Chen, T., Xu, P., Li, H., Chen, R., et al. (2014). Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials towards the breakthrough of organoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 26, 7931–7958. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402532

Tsuchiya, Y., Tsuji, K., Inada, K., Bencheikh, F., Geng, Y., Kwak, H. S., et al. (2020). Molecular design based on donor-weak donor scaffold for blue thermally-activated delayed fluorescence designed by combinatorial DFT calculations. Front. Chem. 8:403. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00403

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H., and Adachi, C. (2012). Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11687

Wang, Y. F., Lu, H. Y., Shen, Y. F., Li, M., and Chen, C. F. (2019). Novel oxacalix[2]arene[2]triazines with thermally activated delayed fluorescence and aggregation-induced emission properties. Chem. Commun. 55, 9559–9562. doi: 10.1039/C9CC04995A

Wong, M. Y., Krotkus, S., Copley, G., Li, W., Murawski, C., Hall, D., et al. (2018). Deep blue oxadiazole-containing thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters for organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 33360–33372. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b11136

Wong, M. Y., and Zysman-Colman, E. (2017). Purely organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 29:1605444. doi: 10.1002/adma.201605444

Woo, S. J., Kim, Y., Kim, Y. H., Kwon, S. K., and Kim, J. J. (2019). A spiro-silafluorene-phenazasiline donor-based efficient blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter and its host-dependent device characteristics. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 4191–4198. doi: 10.1039/C9TC00193J

Yang, X., Xu, X., and Zhou, G. (2015). J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 913–944. Recent advances of the emitters for high performance deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. doi: 10.1039/C4TC02474E

Keywords: thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF), pyridazine, organic light-emitting diode (OLED), reverse intersystem crossing (rISC), donor-acceptor (D–A) architecture

Citation: Krotkus S, Matulaitis T, Diesing S, Copley G, Archer E, Keum C, Cordes DB, Slawin AMZ, Gather MC, Zysman-Colman E and Samuel IDW (2021) Fast Delayed Emission in New Pyridazine-Based Compounds. Front. Chem. 8:572862. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.572862

Received: 15 June 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020;

Published: 07 January 2021.

Edited by:

Guigen Li, Texas Tech University, United StatesReviewed by:

Xu-Lin Chen, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaJuozas Vidas Grazulevicius, Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

Anastasia Klimash, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Krotkus, Matulaitis, Diesing, Copley, Archer, Keum, Cordes, Slawin, Gather, Zysman-Colman and Samuel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eli Zysman-Colman, ZWxpLnp5c21hbi1jb2xtYW5Ac3QtYW5kcmV3cy5hYy51aw==; Ifor D. W. Samuel, aWR3c0BzdC1hbmQuYWMudWs=

†Present address: Simonas Krotkus, AIXTRON SE, Herzogenrath, Germany

Graeme Copley, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Simonas Krotkus

Simonas Krotkus Tomas Matulaitis

Tomas Matulaitis Stefan Diesing

Stefan Diesing Graeme Copley

Graeme Copley Emily Archer

Emily Archer Changmin Keum1

Changmin Keum1 David B. Cordes

David B. Cordes Malte C. Gather

Malte C. Gather Eli Zysman-Colman

Eli Zysman-Colman