94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 23 August 2019

Sec. Theoretical and Computational Chemistry

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2019.00586

This article is part of the Research Topic Computational Chemistry in Homogeneous Catalysis View all 7 articles

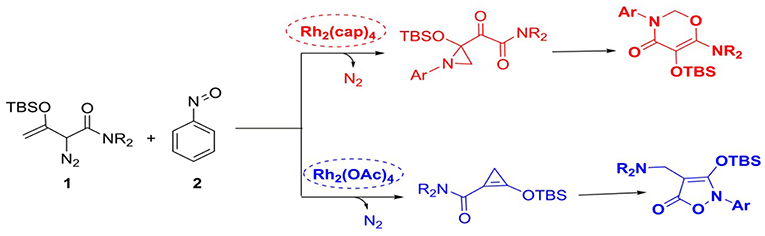

N-O heterocycle compounds play an important role in various fields. Doyle et al. (Cheng et al., 2017) have recently reported an efficient catalyst-controlled selective cyclization reactions of tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS)-protected enoldiazoacetamides with nitrosoarenes in which the multifunctionalized products 5-isoxazolones and 1,3-oxazin-4-ones were formed through [3+2]- and [5+1]-cyclizations using Rh2(oct)4 and Rh2(cap)4 as catalysts, respectively. The present work studied the mechanism of the reactions in question and the origins of the catalyst-dependent chemoselectivity by the density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the M06-D3/SMD/6-311+G(d,p)//B3LYP-D3/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The computed results illustrate the importance of the different dirhodium catalysts to gain diversified N-O heterocycle compounds and suggest the specific interaction between the reactants by the real catalyst model. Meanwhile, it is the steric hindrance and electronic effect of the ligands of dirhodium catalysts that control the reaction mechanism. Furthermore, the other auxiliary theoretical analysis, natural bond orbital calculation and distortion/interaction analysis, make the electronic effects, and steric hindrance more distinct.

Diazo compounds play a significant role in organic synthetic field, and these compounds are always classified as three typical classes: acceptor, donor/acceptor, and acceptor/acceptor, according to the electronic effect of the substituents (Davies and Beckwith, 2003; Zhu et al., 2008), as shown in Scheme 1. However, the thermal stability of these diazo compounds is not good, which is depended on the electronic effect of the substituents connected with the diazo carbon atom, and the acceptor/acceptor type is the most stable one (Regitz and Maas, 1986; Mass, 2009). Because of their poor thermal stability, diazocompounds can become to the active carbene with one molecule nitrogen expulsed in the presence of heat, light, or metal catalyst. And under the circumstance of the heat and light, the diazo compounds will come into being free carbene, which is limitedly applied owing to the extremely unstable character. However, the metal carbenes generated by the interaction of metal catalyst with diazo compoundsare more stable and also well-applied in organic synthesis (Doyle et al., 1998; Mass, 2009), and these two ways of carbene formation are shown in Scheme 2. As for the formation of metal carbene, this is a nucleophilic addition step between metal catalyst and diazo compound (Holzwarth et al., 2012). Due to their good stability, high activity, and significant selectivities (chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivities), those metal carbenes have been paid more attention by chemists in recent years (Denton and Davies, 2009). Moreover, the active metal carbenes were widely used in the reactions of C-H bond functionalization, C-H insertion, alkene cyclopropanation, and ylide formation (Doyle et al., 1998; Davies and Beckwith, 2003; Li and Davies, 2009).

Due to the difference of substituents in diazo compound, the corresponding metal carbenes show different characteristics. Moreover, the diverse metal carbenes have certain pertinence to different reactions. For example, the metal carbene generated by the reaction of metal catalyst with acceptor-substituted diazo compound has a great stereoselectivity for alkene cyclopropanation reactions (Hu et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2008), while the characters of donor/acceptor-substituted carbenes, like vinyldiazoesters, and aryldiazoesters, have been greatly improved and can be applied to more reactions (Davies, 1999; Davies and Beckwith, 2003). However, the acceptor/acceptor metal carbenes take on low activity and poor enatioselectivity for asymmetric cyclopropanation reactions (Doyle, 1986; Davies and Beckwith, 2003; Zhu et al., 2008). Therefore, the selection of substituents is so important for chemical reaction.

On the other hand, the diverse metal catalysts interacted with diazo compounds gain a number of metal carbenes, such as copper-carbene (Salomon and Kochi, 1973; Zhao et al., 2012), iron-carbene (Holzwarth et al., 2012), gold-carbene (Ye et al., 2010), rhodium-carbene (Denton and Davies, 2009; Shi et al., 2013), and other transition metal carbenes. Among the various metal carbenes, the rhodium-carbene with high catalytic activity is the most prominent. By the way, most of rhodium catalysts are dimers and have good symmetry, like the cage compound. Besides the aforementioned C-H bond functionalization, C-H insertion, and alkene cyclopropanation reactions, rhodium-carbene compounds have also significant reactivity for cycloaddition reactions, especially for the synthesis of five- and six-membered heterocyclic compounds (Pirrung and Blume, 1999; Mehta and Muthusamy, 2002; Reddy and Davies, 2007). Such as the illudins, epoxysorbicilinol, brevicomin, and other important natural products, they all can be successfully synthesized by the cycloaddition reaction of rhodium carbene compounds (Muthusamy et al., 2007). Among multitudinous dirhodium(II) carbenoids, the simplest one is the dirhodium acetate carbenoid (Rh2(OAc)4). Furthermore, by changing the ligands of the dirhodium catalysts, the electron-rich or electron-deficient dirhodium catalysts can be obtained. And then various dirhoduim(II) carbenes are generated and widely used in organic synthesis. Through the electronic and steric hindrance effects of the ligands, the corresponding dirhoduim(II) carbene owns the better selectivity characters (Vitale et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2018). For example, Rh2(cap)4 catalyst is formed through the substituting to four acetate ligands in Rh2(OAc)4 using caprolactamate groups and then becomes Rh2(cap)4-carbenoid compound. Noticeably, the most important thing is that divergent catalysts can catalyze the same substrates to produce different products through different reactions, as reported recently by Dolye group (Cheng et al., 2017). They reported the cyclization reactions between tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS)-protected enoldiazoacetamides and nitrosoarenes catalyzed by divergent dirhodium compounds, in which when the catalyst was Rh2(OAc)4, Rh2(oct)4, Rh2(tpa)4, or Rh2(pfb)4, the final main product was observed to be the five-membered ring compound by [3+2]-cycloaddition, while there was a six-membered ring product through [5+1]-cycloaddition with the Rh2(cap)4 being the catalyst. Hence, it can be seen that the diverse dirhodium catalysts act a significant role in synthetic chemistry.

With the recent development of theoretical methods, the combination of quantum chemical calculations with the experimental researches has made the significant advances in the chemistry. Among the theoretical computational study, the density functional theory (DFT) is the most prominent method (Kohn and Sham, 1965; Dreizler and Gross, 2012; Gross and Dreizler, 2013; Koch and Holthausen, 2015). Theoretical study can explain the experimental phenomena from the microscopic molecular and atomic levels, and reveal the reaction details. Therefore, more and more chemists solve the chemical problems by using the combing of experiment with computational study. Based on this, our group had studied a series of reactions catalyzed by dirhodium via the theoretical study and explained the experimental phenomena very well. At now, we have previously reported [3+3]-, [3+2]-cycloadditions catalyzed by dirhodium carbene compound (Yang et al., 2014, 2016; Zhang et al., 2018), and other computational study on reactions catalyzed by rhodium. Hence, based on our previous research, we are interested in the reactions catalyzed by divergent dirhodium catalysts reported by Dolye group (Cheng et al., 2017). In their experiments (shown in Scheme 3), they detected the presence of certain intermediates, but the mechanism remained unclear. And the most important thing is that there is no specific data to verify the hypothesis mechanism proposed by the experiment author and explain the role of two different catalysts in the system. Therefore, for the deeper understanding of the reaction, we shall adopt DFT method to investigate the reaction mechanism and reveal the special functions of divergent catalysts to produce diverse outcomes in molecular level.

Scheme 3. The cycloaddition reactions of enodiazoacetamide and nitrosoarene catalyzed by divergent dirhodium catalysts.

The theoretical calculations were performed by the use of B3LYP density functional method (Lee et al., 1988; Becke, 1993a,b), augmented with D3 empirical dispersion correction (Grimme et al., 2010; Grimme, 2011). As for geometry optimization in the gas phase, the 6-31G (d, p) basis set was used for all non-metal elements (C, H, O, N, and Si), while the 1997 Stuttgart relativistic small-core effective core-potential combined with a 4f function [ζf (Rh) = 1.350] [Stuttgart RSC 1997 ECP+4f] for rhodium element (Kaupp et al., 1991; Bergner et al., 1993; Hansen et al., 2009). This mixed basis set is donated to BS1. In order to confirm the stationary points as minima without imaginary frequencies or the transition states with only one imaginary frequency, the harmonic frequency calculations were employed at the level of B3LYP-D3/BS1. Moreover, the transition states connected with correct reactants and appropriate products were verified by the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) analysis (Fukui, 1970, 1981).

Because the M06 functional (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008; Deng et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018) is more accurate in energy calculation, the latter single-point energies were calculated for all the B3LYP-D3/BS1-optimized structures in chloroform (the solvent used experimentally, ε = 4.71) with the SMD solvation model (Marenich et al., 2009; Ribeiro et al., 2011), one typical model of polarisable continuum model (PCM; Miertuš et al., 1981; Tomasi et al., 2005) at the level of M06-D3/BS2. BS2 denotes a mixed basis set of 6-311+G(d,p) for all non-metal elements and [Stuttgart RSC 1997 ECP+4f] for rhodium atom. These M06-D3/SMD/BS2 electronic energies were then added to the free energy correction evaluated from the unscaled vibrational frequencies on the B3LYP-D3/BS1 optimized geometries in the gas phase at 298.15 K and 1 atm to obtain the Gibbs free energies in chloroform solvent. Nature bond orbital (NBO) analysis was done with the B3LYP-D3/BS1 method. All the DFT calculations were performed by the use of Gaussian 09 program (Frisch et al., 2009). And the non-covalent interaction (NCIplot) analysis was carried out with program Multiwfn (Lu and Chen, 2012).

We first studied the [3+2]-cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by Rh2(OAc)4, for which the following mechanisms were hypothesized according to our previous study and the mechanism provided by the experimental author (Cheng et al., 2017), as shown in Scheme 4. There are three pathways, named paths A, B, and C, respectively, and the mechanism starts with the Rh2(OAc)4-carbene (OAc-cb) generated by the interaction of Rh2(OAc)4 with diazo compound 1. Then the carbenoid comes into being the three-membered cyclopropene compound 3 by intramolecular cyclization via transition state ts1, which is the common first step of paths A, B, and C. By the way, it's worth mentioning that this cyclopropene 3 was detected in the [3+2]-cycloaddition process of Rh2(OAc)4-catalyzed diazo compound as the intermediate (Cheng et al., 2017), therefore, the reaction mechanism must go through this step. Next, three pathways for the following steps are taken into consideration after cyclopropane formation. In fact, the processes of these three pathways are the same, which are differentiated by the reaction sites of catalyst.

For path A, after the formation of cyclopropene, the dirhodium catalyst separated away, and there is no catalyst in the subsequent steps. The N atom of nitro of nitrosoarene 2 interacts with the C = C bond of cyclopropene compound via transition state A-ts2 and then generates intermediate A-int1. Then the ring of three-membered intermediate breaks and turns into intermediate A-int2 through A-ts3 transition state. And the following step is NR2 group transferring to the vinyl group by the four-membered ring transition state A-ts4 and then electron rearrangement gives A-int3. Finally, the ketene analog A-int3 comes into being the five-membered ring product which goes through the interaction of O atom of nitro with C atom of C = O bond by the way of intramolecular ring closed. As mentioned earlier, the processes of path B and path C are similar to path A, but these two pathways both have the dirhodium catalyst interaction. In path B, the Rh2(OAc)4 interacts with the O atom of C = O group of 3, which is adjacent with NR2 group from beginning to end. However, the dirhodium catalyst always reacts with the O atom of the nitro group in 2 in path C.

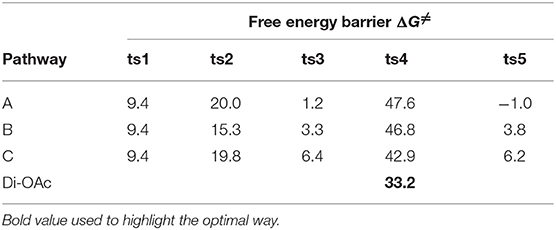

The free energy profiles of aforementioned pathways are depicted in Figure 1 and the corresponding free energy barriers are shown in Table 1. As shown in free energy profile, the blue line is path A, the pink color represents path B and the black one indicates path C. By the way, the energy barriers in Table 1 are more simple and clear. At first glance, the free energies of activation of ts4 are too high among all three pathways. Separately, the generation of cyclopropene 3 from Rh2(OAc)4 carbene compound needs free energy barrier of 9.4 kcal/mol. For the step of cyclopropene addition, the free energy barrier is 20.0, 15.3, and 19.8 kcal/mol for paths A, B, and C orderly. Compared with the ts2, the free energy barrier of ts3 in three pathways is much lower, being 1.2, 3.3, 6.4 kcal/mol, respectively, and this means that three-membered ring breaking is much easier to occur. However, the most difficult step is NR2 group transfer, with the high free energy barrier in 47.6, 46.8, 42.9 kcal/mol, respectively. Finally, owing to the high activity of ketene analog A-int3, it can quickly react to final product without free energy barrier (−1.0 kcal/mol) in path A, however, there need 3.8 and 6.2 kcal/mol free energy barriers in path B and path C. That's to say, the interaction of Rh2(OAc)4 with ketene analog A-int3 can make it more stable. In addition, with the high free energy barrier of ts4, the transfer step of NR2 group cannot take place like this in all three pathways.

Table 1. The free energy barriers (ΔG≠, kcal/mol) of three pathways of Rh2(OAc)4-catalyzed [3+2]-cycloaddition reaction.

On the base of the previous calculation results, we have tried our best to decrease the free energy barrier of ts4 formation and we find that the two molecule Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst, one interacting with O atom in nitro group and the other one reacting with O atom of C = O group, named Di-OAc-ts4 (the red color in Figure 1), can make the barrier lower, with 33.2 kcal/mol (this is based on path B, and 38.0 kcal/mol on path C) which is the lowest barrier that we found (see some other transition state structures in Figure S1 of Supporting information). To sum up, the better pathway is path B with the rhodium catalyst interacting with the C = O group. Hence, the whole mechanism of [3+2]-cycloaddition catalyzed by Rh2(OAc)4 includes mainly five steps, formation of cyclopropane (ts1), cyclopropene addition (B-ts2), three-membered ring open (B-ts3), NR2 group transfer (Di-OAc-ts4), and five-membered outcome generated (B-ts5), and the process of NR2 group transfer with two molecular catalyst to stable the reaction system is the rate-limiting step.

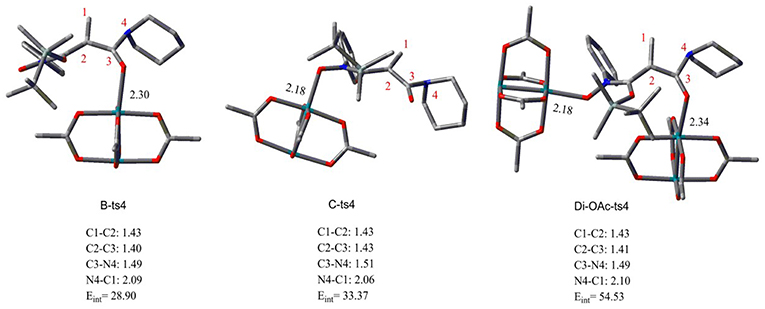

Aimed at the NR2 group transfer step, the structures of the B-ts4, C-ts4, and Di-OAc-ts4 are compared clearly, the results are vividly depicted in Figure 2. In order to make the structure more distinct, we just show the molecular skeleton. Firstly, in terms of reaction center, the Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst has little effect on it, and the bond length of the reaction center hardly changes. However, the distances of Rh-O in B-ts4, C-ts4, and Di-OAc-ts4 are more different. So as you see from Figure 2, the Rh-O bond of B-ts4 is 2.30 Å, C-ts4 is 2.18 Å, and two bond lengths in Di-OAc-ts4 are 2.18 Å and 2.34 Å as well. In terms of the bond length, the shorter bond in C-ts4, we can get that, suggests that there is a stronger interaction in C-ts4 than in B-ts4. And the relative free energy also accords with the result, that the free energy of C-ts4 is 8.7 kcal/mol lower than B-ts4. Moreover, the value of interaction energy (Eint) also verifies the conclusion. And Eint is 28.90 kcal/mol and 33.37 kcal/mol in B-ts4 and C-ts4, respectively. Noticeably, the interaction energy of two-molecule catalysts in Di-OAc-ts4 is 54.53 kcal/mol, it can be seen that the Di-OAc-ts4 is the most stable one with the huge interaction energy.

Figure 2. The structures of transition states B-ts4, C-ts4, and Di-OAc-ts4 (bond length in Å and energy in kcal/mol).

Regard to mechanism of the [5+1]-cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by Rh2(cap)4, we put forward the following pathways, as shown in Scheme 5. In this part, start with reactants (1 and 2), and Rh2(cap)4 catalyst. Here, the [5+1]-cycloaddition reaction may generate five-membered ring intermediate int2 and then expands into a six-membered ring product. Hence, we hypothesized three different pathways in the process of int2 formation and one path to ring enlargement.

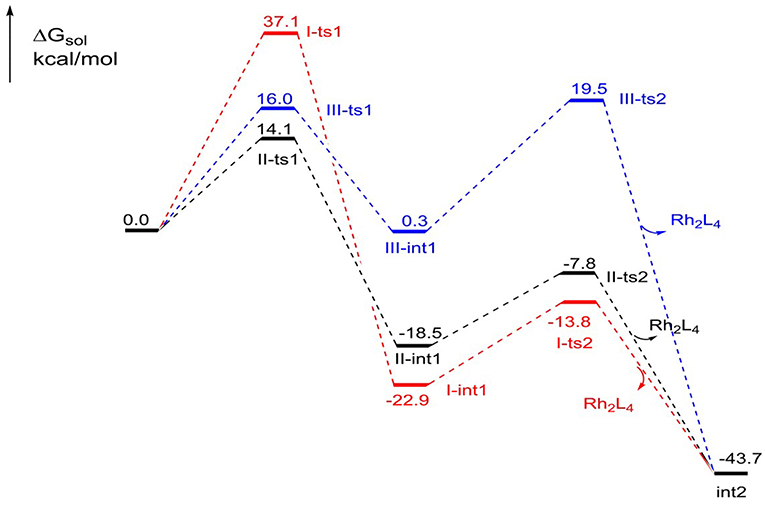

As to the formation of five-membered ring intermediate int2, three pathways are path I, path II, and path III, respectively. For path I, firstly, the Rh2(cap)4 interacts with N atom of nitro of reactant 2 to form compound 4. Then the O atom of nitro in 4 reacts with the diazo group of reactant 1, and nitrogen goes away to generate A-int1 by the transition state I-ts1. Next, the N atom of nitro attacks the terminal alkenyl leading to the formation of the five-membered ring intermediate int2 by the transition state I-ts2. Obviously, the other two ways are more different, and they begin with the cap-cb generated by the interaction of Rh2(cap)4 with reactant 1. In Path II, the first step is that O atom of nitro reacts with carbene center via transition state II-ts1, and catalyst transfers to interact with C = O group to form II-int1. Then N atom attacks the terminal alkenyl group to produce int2 through five-membered ring closed, which called carbene addition step. Differently, the order in path III is reverse. Firstly, the N atom of nitro interacts with the terminal alkenyl group via III-ts1, and then ring closes to form int2 which we called alkenyl addition step. During the formation of int2 by closed-ring process, the dirhodium catalyst leaves away the reaction system.

As shown in Scheme 5, after the various ways to int2, the initial N-O bond will break to generate int3 by N-O bond heterolysis. Next, the intermediate int3 goes directly to compound 5, which was detected in the experiment (Cheng et al., 2017). And the following step is three-membered ring open to turn into int4 with the transition state ts4. Then, the TBS (tert-butyldimethylsilyl) group transfers to the adjacent carbonyl group by the way of five-membered ring transition state ts5. Finally, the alkenyl group formed by three-membered ring open reacts with the carbonyl group connected with NR2 group to give the six-membered ring product. Owing to the departure of the Rh2(cap)4 catalyst in the formation of int2, the steps from int2 to final product are no catalyst interaction.

The free energy profiles of the three foregoing addition pathways to int2 formation are shown in Figure 3. The red, black, and bluelines represent path I, path II, and path III, respectively. At first glance, the step of N2 away has high energy barrier in 37.1 kcal/mol in path I, and the next intramolecular closed-loop step is in 9.1 kcal/mol. Compared to other two ways, it is more difficult to take place. For the path II, the free energy barrier of carbene center addition step is 14.1 kcal/mol, and it is 23.0 kcal/mol lower than I-ts1, and 1.9 kcal/mol lower than III-ts1. Moreover, the closed-ring step owns a free energy barrier of 10.7 kcal/mol. Meanwhile, the free energy barriers of the two steps in third path are 16.0 and 19.2 kcal/mol, respectively, and the second step is 8.5 kcal/mol higher than II-ts2 in path II. By comparison, for the formation of the five-membered intermediate int2, the path II is the most favorable way with the lowest free energy barrier. This result overturns the experiment author's hypothesis, which suggests the mechanism is going like path I (Cheng et al., 2017).

Figure 3. The free energy profiles of three pathways in the formation of the five-membered ring compound int2.

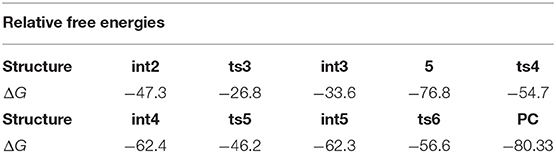

The relative free energies to separated reactants for the intermediates and transition states in subsequent steps are shown in Table 2. As we can see, the free energy barrier from int2 to ts3, five-membered ring open, is 20.5 kcal/mol. It's worth noting that there is no free energy barrier from int3 to three-membered N-heterocycle compound 5. The scanning of this process was performed and no transition state was located in its potential energy surface. Next, the ring-opening of 5 has a free energy barrier of 22.1 kcal/mol. What's more, the free energy barrier of TBS group transfer is in 16.2 kcal/mol and the formation of final six-membered product needs the free energy barrier of 5.7 kcal/mol. In brief, among the free energy barrier values of the whole reaction mechanism, the ring-breaking step of N-heterocycle compound 5 (from 5 to int4 via ts4 in Scheme 5) has the most high free energy barrier, 22.1 kcal/mol, and is the rate-limiting step of the [5+1]-cycloaddition catalyzed by Rh2(cap)4. By the way, the step of catalyst-deciding is carbene addition.

Table 2. The relative free energies (ΔG, kcal/mol) of intermediates and transition states (from int2 to PC) to separated reactants.

For the barrier-free process from int3 to 5, the natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis was carried out, and the charge changes from int2 to compound 5 are shown in Figure 4. According to charge changes, the results suggest that the process of N-O bond breaking goes through the heterolysis way, and the electrons transfer to N1 atom. This way makes the charge of N atom more negative (−0.26 e−), and O5 atom positive. And then electron rearrangement, electrons transfer from O6 atom to O5 atom, makes charge of O5 change invariant. However, the intermediate int3 is not stable enough, and it comes into being compound 5, with the huge energy release of 43.2 kcal/mol, which is the interaction of positive and negative charges. We speculated that the most possible reason is the difference in stability between the two structures.

For aforementioned [3+2]-cycloaddition and [5+1]-cycloaddition reactions, there is bewilderment unknown: why the different catalysts can obtain different products for the same reactants. In order to understand the origin of catalyst-dependent chemoselectivity in these dirhodium-catalyzed cyclization reactions, we will analyze and compare the two [3+2]-cycloaddition and [5+1]-cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by different catalysts Rh2(OAc)4 and Rh2(cap)4 in several ways.

Firstly, the Rh2(II)-carbene formation step is taken into consideration. In this process, reactant 1 reacts with different catalysts Rh2(OAc)4 and Rh2(cap)4, respectively, to form the corresponding Rh2(II)-carbene with the elimination of N2 molecule. The free energy barriers and transition structures are shown in Figure 5. Beginning with the two catalysts, the charges of center rhodium are different on account of the electronic effect differences of the ligands in catalysts. And the charge of center rhodium in Rh2(OAc)4 is 0.50, while 0.44 for Rh2(cap)4. Then the catalyst reacts with reactant 1, the formation of transition state OAc-N2-ts (for Rh2(OAc)4) needs the free energy of activation (ΔG≠) of 10.3 kcal/mol, and the free energy barrier of cap-N2-ts (for Rh2(cap)4) is 19.4 kcal/mol, which is 9.1 kcal/mol higher than the former. There is little difference between the bond lengths of the reaction centers in transition states. The bond distances of Rh-C and C-N bonds are 2.16 Å and 1.70 Å in OAc-N2-ts, respectively. Similarly, the Rh-C bond is 2.20 Å, and C-N bond is 1.74 Å for transition state cap-N2-ts. However, the main distinction is the electron transfer number. During the course of Rh2(OAc)4 becoming to OAc-N2-ts, there is 0.18 e− (from 0.50 to 0.68) transferring from catalyst to reactant 1. Moreover, the electron transfer number is 0.38 e− in the Rh2(cap)4 catalyzed process. So it can be concluded that the dirhodium catalyst in this step is in the type of electron donor. Hence, the electronic effect of the ligand in catalyst is most important for the catalyst activity.

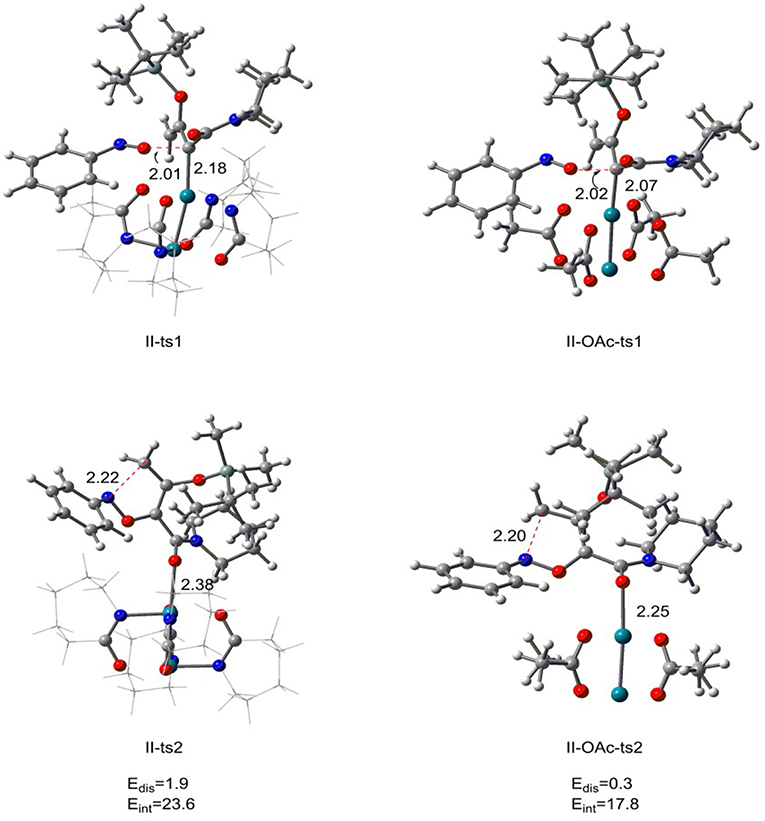

From the previous discussion, we know that the optimal catalyst interaction pathway of Rh2(cap)4-catalyzed [5+1]-cycloaddition reaction is carbene addition way (path II). Therefore, in order to compare the two different catalysts, we changed the Rh2(cap)4 with Rh2(OAc)4 in carbene addition step, and the results are displayed in Figure 6. For the first step, the relative free energy of II-OAc-ts1 is 10.4 kcal/mol which is 3.7 kcal/mol lower than II-ts1 (14.1 kcal/mol) in [5+1]-cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by Rh2(cap)4, and this computational result suggests that II-OAc-ts1 is more stable than II-ts1. And this difference is caused by the bond length of Rh-C bond. In Figure 6, the Rh-C bond distance is 2.18 Å in II-ts1 structure, and 2.07 Å in II-OAc-ts1, and the shorter bond means stronger interaction, which makes transition state II-OAc-ts1 more stable.

Figure 6. The transition state structures of II-ts1, II-ts2 in [5+1]-cycloadditioncatalyzed by Rh2(cap)4 and II-OAc-ts1, II-OAc-ts2 in [5+1]-cycloadditioncatalyzed by Rh2(OAc)4 along with the distortion/interaction analysis (bond length is in Å, energies are given in kcal/mol).

However, the bond length is inconsistent with the stability in the five-membered ring closed step. The Rh-O bond of II-ts2 is 2.38 Å, and 2.25 Å in II-OAc-ts2, but the relative free energies of II-ts2 and II-OAc-ts2 are −7.8 and 7.0 kcal/mol, respectively, which suggests that transition state II-ts2 is more stable than II-OAc-ts2. In addition, the distortion/interaction analysis (Zhang et al., 2018) was adopted to explain this phenomenon. Edis means the total distortion energy [combining catalyst part with reaction part (the system except rhodium catalyst)], and Eint represents the interaction energy between the catalyst and reaction part. Comparing the distortion energies between two transition states II-ts2 and II-OAc-ts2, there is very small difference of 1.6 kcal/mol. However, the interaction energy Eint of II-ts2 is 23.6 kcal/mol, 5.8 kcal/mol higher than that of II-OAc-ts2. The stronger interaction between the rhodium catalyst and reaction part in II-ts2 than in II-OAc-ts2 makes II-ts2 more stable, with 14.8 kcal/mol lower than II-OAc-ts2 in free energy. That's to say, the Rh2(cap)4 is more conducive to the formation of int2, so as to complete the subsequent ring enlargement to form six-element ring products. In other words, this computational result reveals it is Rh2(cap)4 that catalyzes [5+1]-cycloaddition.

For the [3+2]-cycloaddition catalyzed by Rh2(OAc)4, the rate-limiting step is NR2 group transfer with two molecular catalysts interacted. In order to explore the catalyst role, we changed the Rh2(OAc)4 with Rh2(cap)4, and the transition state named Di-cap-ts4. The electronic effect and steric hindrance effect analyses are considered, and the results are shown in Figures 7, 8. In terms of electronic effect, the results in Figure 7 suggest that the charge of reaction center with tiny change is caused by the different catalysts. By comparing the direction of electron flow, we can get that the Rh2(cap)4 catalyst acts as the electron acceptor with the charges of C1, C2, C3 atoms becoming positive, and O5 charge being more negative, as shown by the arrow in Di-cap-ts4. By the way, the more negative C1 atom is, the more easy NR2 group transfer.

And then the non-covalent interaction (NCIplot) analysis was carried out, the results are shown in Figure 8. Firstly, the bond length of two Rh-O bonds should be illustrated. The Rh-O bond of nitro in Di-OAc-ts4 structure is 2.18 Å, and the Rh-O bond of carbonyl is 2.34 Å, while the bond length is 2.57 Å, and 2.43 Å in Di-cap-ts4, respectively, which shows the Di-OAc-ts4 is more stable than the one in Rh2(cap)4 replaced with two shorter bonds. Meanwhile, the result of steric hindrance effect is consistent with the previous conclusion. The steric hindrance of Di-cap-ts4 is larger than Di-OAc-ts4, furthermore, there is a space repulsion between the two molecular catalysts in Di-cap-ts4 and this repulsion effect main depends on the larger cap ligand. Hence, the huge steric hindrance makes it unstable, in other words, Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst is more favorable for [3+2]-cycloaddition reaction, and this theoretical result explains why no five-membered ring product appeared when Rh2(cap)4 was used as the catalyst.

The DFT B3LYP-D3 method has been employed to investigate reaction mechanism of cyclization reactions between enoldiazoacetamides and nitrosoarens catalyzed by divergent rhodium catalysts. When Rh2(OAc)4 acts as the catalyst, among three pathways considered, path B with catalyst interacting with O = C group is the most feasible way, and the NR2 group transfer step involved in two-molecule Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst is the rate-limiting step. While, the most favorable path is path II, carbene addition, when the Rh2(cap)4 was the catalyst, and the N-heterocycle compound ring open step is the rate-limiting step. By the way, the catalyst-deciding step is inconsistent with the rate-limiting step. The important effects of catalyst on this reaction system is mainly due to electronic effect and steric hindrance effect of the ligand in divergent catalysts. For the initial carbene formation step, Rh2(cap)4 is harder than Rh2(OAc)4 owing to the electronic effect. The Rh2(cap)4 cannot catalyze [3+2]-cycloaddition reaction also due to both electronic effect and steric hindrance effect, because the huge steric hindrance between the ligands on the catalyst. Meanwhile, the Rh2(OAc)4 will not catalyze [5+1]-cycloaddition on account of the stability of transition structure, which decided by the interaction between catalyst, and reaction part. The mechanisms of cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by divergent dirhodium, and the important role of catalysts are firstly studied in detail in this computation paper, which can take on deep understanding of cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by diverse dirhodium catalysts.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the Supplementary File.

YX designed the research. YZ, YY, and RZ were involved in the calculations. YZ, YY, and XW analyzed the data. YZ and YX wrote the manuscript.

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21573153).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2019.00586/full#supplementary-material

Becke, A. D. (1993a). A new mixing of hartree–fock and local density-functional theories. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 1372–1377. doi: 10.1063/1.464304

Becke, A. D. (1993b). Density-functional thermochemistry. III. the role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913

Bergner, A., Dolg, M., Küchle, W., Stoll, H., and Preuß, H. (1993). Ab initio energy-adjusted pseudopotentials for elements of groups 13–17. Mol. Phys. 80, 1431–1441. doi: 10.1080/00268979300103121

Cheng, Q. Q., Lankelma, M., Wherritt, D., Arman, H., and Doyle, M. P. (2017). Divergent rhodium-catalyzed cyclization reactions of enoldiazoacetamides with nitrosoarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9839–9842. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05840

Davies, H. M., and Beckwith, R. E. (2003). Catalytic enantioselective C–H activation by means of metal–carbenoid-induced C–H insertion. Chem. Rev. 103, 2861–2904. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217

Davies, H. M. L. (1999). Dirhodium tetra (N-arylsulfonylprolinates) as chiral catalysts for asymmetric transformations of vinyl-and aryldiazoacetates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 10, 2459–2469. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0690(199910)1999:10<2459::AID-EJOC2459>3.0.CO;2-R

Deng, C., Zhang, J. X., and Lin, Z. Y. (2017). Theoretical studies on Pd(II)-catalyzed meta-selective C-H bond arylation of arenes. ACS. Catal. 8, 2498–2507. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b03588

Denton, J. R., and Davies, H. M. L. (2009). Enantioselective reaction of doner/acceptor carbenoids derived from α-Aryl-α-Diazoketones. Org. Lett. 11, 787–790. doi: 10.1021/ol802614j

Doyle, M. P. (1986). Catalytic methods for metal carbene transformations. Chem. Rev. 86, 919–939. doi: 10.1021/cr00075a013

Doyle, M. P., McKervey, M. A., and Ye, T. (1998). Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis With Diazo Compounds: From Cyclopropanes to Ylides. New York, NY: Wiley.

Dreizler, R. M., and Gross, E. K. (2012). Density Functional Theory: An Approach to the Quantum Many-Body Problem. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York, NY; London; Paris; Tokyo; Hong Kong; Barcelona: Springer Science & Business Media.

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, Revision D.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.

Fukui, K. (1970). Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys Chem. 74, 4161–4163. doi: 10.1021/j100717a029

Fukui, K. (1981). The path of chemical reactions-the IRC approach. Accounts. Chem Res. 14, 363–368. doi: 10.1021/ar00072a001

Grimme, S. (2011). Density functional theory with London dispersion corrections. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. 1, 211–228. doi: 10.1002/wcms.30

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S., and Krieg, H. (2010). A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132:154104. doi: 10.1063/1.3382344

Gross, E. K., and Dreizler, R. M. (Eds.) (2013). Density Functional Theory (Vol. 337). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Hansen, J., Autschbach, J., and Davies, H. M. (2009). Computational study on the selectivity of donor/acceptor-substituted rhodium carbenoids. J. Org. Chem. 74, 6555–6563. doi: 10.1021/jo9009968

Holzwarth, M. S., Alt, I., and Plietker, B. (2012). Catalytic activation of diazo compounds using electron-rich, defined iron complexes for carbene-transfer reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5351–5354. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201409

Hu, W., Timmons, D. J., and Doyle, M. P. (2002). In search of high stereocontrol for the construction of cis-disubstituted cyclopropane compounds. total synthesis of a cyclopropane-configured urea-PETT analogue that is a HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Org. Lett. 4, 901–904. doi: 10.1021/ol017276b

Kaupp, M., Schleyer, P. V. R., Stoll, H., and Preuss, H. (1991). Pseudopotential approaches to Ca, Sr, and Ba hydrides. why are some alkaline earth MX2 compounds bent? J. Chem. Phys. 94, 1360–1366. doi: 10.1063/1.459993

Koch, W., and Holthausen, M. C. (2015). A Chemist's Guide to Density Functional Theory. John Wiley & Sons.

Kohn, W., and Sham, L. J. (1965). Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140:A1133. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133

Lee, C., Yang, W., and Parr, R. G. (1988). Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37:785. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785

Li, Z., and Davies, H. M. (2009). Enantioselective C– C bond formation by rhodium-catalyzed tandem ylide formation/[2, 3]-sigmatropic rearrangement between donor/acceptor carbenoids and allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 396–401. doi: 10.1021/ja9075293

Lu, T., and Chen, F. (2012). Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem.33, 580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J., and Truhlar, D. G. (2009). Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys Chem. B 113, 6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n

Mass, G. (2009). New syntheses of diazo compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 8186–8195. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902785

Mehta, G., and Muthusamy, S. (2002). Tandem cyclization–cycloaddition reactions of rhodium generated carbenoids from alpha-diazo carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron 58, 9477–9504. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01187-0

Miertuš, S., Scrocco, E., and Tomasi, J. (1981). Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilizaion of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. J. Chem. Phys. 55, 117–129. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2

Muthusamy, S., Krishnamurthi, J., Babu, S. A., and Suresh, E. (2007). Anomalous reaction of Rh2(OAc)4-generated transient carbonyl ylides: chemoselective synthesis of epoxy-bridged tetrahydropyranone, oxepanone, oxocinone, and oxoninone ring systems. J. Org. Chem. 72, 1252–1262. doi: 10.1021/jo0621726

Pirrung, M. C., and Blume, F. (1999). Rhodium-mediated dipolar cycloaddition of diazoquinolinediones. J. Org. Chem. 64, 3642–3649. doi: 10.1021/jo982503h

Reddy, R. P., and Davies, H. M. (2007). Asymmetric synthesis of tropanes by rhodium-catalyzed [4+ 3] cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10312–10313. doi: 10.1021/ja072936e

Regitz, M., and Maas, G. (1986). Diazo Compounds—Properties and Synthesis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Ribeiro, R. F., Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J., and Truhlar, D. G. (2011). Use of solution-phase vibrational frequencies in continuum models for the free energy of solvation. J. Phys Chem. B 115, 14556–14562. doi: 10.1021/jp205508z

Salomon, R. G., and Kochi, J. K. (1973). Copper (I) catalysis in cyclopropanations with diazo compounds. role of olefin coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 3300–3310. doi: 10.1021/ja00791a038

Shi, Z., Koester, D. C., Boultadakis-Arapinis, M., and Glorius, F. (2013). Rh (III)-catalyzed synthesis of multisubstituted isoquinoline and pyridine N-oxides from oximes and diazo compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12204–12207. doi: 10.1021/ja406338r

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B., and Cammi, R. (2005). Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009

Vitale, M., Lecourt, T., Sheldon, C. G., and Aggarwal, V. K. (2006). ligand-induced control of C– H versus aliphatic C– C migration reactions of Rh carbenoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2524–2525. doi: 10.1021/ja057739z

Wu, H. L., Li, X. J., Tang, X. Y., Feng, C., and Huang, G. P. (2018). Mechanisms of rhodium(III)-catalyzed C-H functionalizations of benzamides with α,α-difluoromethylene alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 83, 9220–9230. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01229

Yang, X., Xu, P., and Xue, Y. (2014). Mechanism and regioselectivity of the cycloaddition between nitrone and dirhodium vinylcarbene catalyzed by Rh2(O2CH)4: a computational study. Theor. Chem. Acc. 133:1549. doi: 10.1007/s00214-014-1549-7

Yang, X., Yang, Y., Rees, R. J., Yang, Q., Tian, Z., and Xue, Y. (2016). How dirhodium catalyst controls the enantioselectivity of [3+2]-cycloaddition between nitrone and vinyldiazoacetate: a density functional theory study. J. Org. Chem. 81, 8082–8086. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01447

Ye, L., Cui, L., Zhang, G., and Zhang, L. (2010). Alkynes as equivalents of α-diazo ketones in generating α-oxo metal carbenes: a gold-catalyzed expedient synthesis of dihydrofuran-3-ones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3258–3259. doi: 10.1021/ja100041e

Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Zhao, J., and Xue, Y. (2018). Mechanism and diastereoselectivity of [3+3] cycloaddition between enol diazoacetate and azomethine imine catalyzed by dirhodium tetracarboxylate: a theoretical study. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 3086–3094. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201800261

Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., and Wang, J. (2012). Recent developments in copper-catalyzed reactions of diazo compounds. Chem. Commun. 48, 10162–10173. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34406h

Zhao, Y., and Truhlar, D. G. (2008). The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. doi: 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x

Keywords: DFT, mechanism, cyclization, dirhodium, chemoselectivity

Citation: Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhu R, Wang X and Xue Y (2019) Catalyst-Dependent Chemoselectivity in the Dirhodium-Catalyzed Cyclization Reactions Between Enodiazoacetamide and Nitrosoarene: A Theoretical Study. Front. Chem. 7:586. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00586

Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 05 August 2019;

Published: 23 August 2019.

Edited by:

Zexing Cao, Xiamen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Hujun Xie, Zhejiang Gongshang University, ChinaCopyright © 2019 Zhang, Yang, Zhu, Wang and Xue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Xue, eXh1ZUBzY3UuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.