95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 23 July 2019

Sec. Inorganic Chemistry

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2019.00520

This article is part of the Research Topic Inorganic Chemistry Editor’s Pick 2021 View all 20 articles

Karolina Kniec*

Karolina Kniec* Lukasz Marciniak*

Lukasz Marciniak*The spectroscopic properties of LaGaO3, doped with V ions, were examined in terms of the possibility of the stabilization of particular vanadium oxidation states. It was shown that three different approaches may be applied in order to control the ionic charge of vanadium, namely, charge compensation, via incorporation of Mg2+/Ca2+ ions, citric acid (CA)-assisted synthesis, with various CA concentrations and grain size tuning through annealing temperature regulation. Each of utilized method enables the significant reduction of V5+ emission band at 520 nm associated with the V4+→ O2− CT transition in respect to the 2E→ 2T2 emission band of V4+ at 645 nm and 1E2 → 3T1g emission band of V3+ at 712 nm. The most efficient V oxidation state stabilization was obtained by the use of grain size modulation, which bases on fact of different localization of the V ions of given charge in the nanoparticles. Moreover, the CA-assisted synthesis of LaGaO3:V determines V valence states but also provides significant separation of the nanograins. It was found that superior charge compensation was achieved when Mg2+ ions were introduced in the matrix, due the more efficient lability, resulting from the comparable ionic radii between Mg2+ and V ions.

It is well-known that the electronic configuration of optically active ions and thus their spectroscopic properties depend strongly on the their oxidation state (Weber and Riseberg, 1971; Felice et al., 2001; Gupta et al., 2014; Matin et al., 2017; Drabik et al., 2018; Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b; Trejgis and Marciniak, 2018). These features may in turn be influenced by many factors, such as type of the lattice, in which the ions are embedded and coordination number of the substituted ion, synthesis method, size of phosphor grain etc. (McKittrick et al., 1999; Azkargorta et al., 2016; Marciniak et al., 2017; Kniec and Marciniak, 2018b; Zhang et al., 2018). The difference in the spectroscopic properties of optically active ions depending on the oxidation state in the case of lanthanides in especially well-manifested for europium ions, which may occur in two 2+ and 3+ oxidation states. Emission spectra of its trivalent ions consist of narrow lines attributed to intraconfigurational f-f electronic transitions whose spectral position is almost independent on the type of host material. On the other hand emission of Eu2+ is characterized by broad d-d emission band of maxima which can be tuned by the modification of the crystal field strength (Peng and Hong, 2007; Mao et al., 2009; Mao and Wang, 2010; Sato et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Similar differences can be found in the case of transition metal (TM) ions, where electronic transitions between d states are responsible for luminescence. In turn the luminescence of TM on different oxidation state is conditioned by presence of either octahedral or tetrahedral local site symmetries, where the optically active ion is substituted (Grinberg et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2018; Elzbieciak et al., 2018). This points to the importance of the appropriate choice of the local ion's environment and thus the host material to obtain efficient luminescence. The valence state of TM influences their output color, what is the most frequently encountered in case of manganese and chromium ions (Brik et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2016, 2018; Elzbieciak et al., 2018). Cr3+ ions may reveal red and NIR luminescence ascribed to the 2Eg → 4A2g spin-forbidden and 4T2g → 4A2g spin-allowed transition and (Struve and Huber, 1985; Brik et al., 2016; Elzbieciak et al., 2018), whereas Cr4+ ions exhibit emission in NIR region (around 1,100 nm), which is attributed to the 3A2 → 3T1 transition (Devi et al., 1996). Different emission color is also observed for manganese ions, where Mn2+, Mn3+ and Mn4+ ions show blue (4A2 → 4T1), yellow-orange (4T1g → 6A1g) or red (5T2 → 5E) luminescence, respectively (Trejgis and Marciniak, 2018). This phenomenon is also observed for titanium ions, where Ti4+ and Ti3+ possess blue and red emission color, which related to the O2− → T2 (CT, λem ~ 450 nm) and 2Eg → 2T2g (λem ~ 800 nm) transitions, respectively (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2005; Pathak and Mandal, 2011; Drabik et al., 2018). The possibility of charge modulation is not only interesting in terms of spectroscopic tunability but also to get rid of some valence states, being marked by toxic properties and reducing the potential biological deployment, which is very important in case of chromium and cobalt ions (Buzea et al., 2007; Chowdhury and Yanful, 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Scharf et al., 2014).

One of the least known transition metal ion, whose optical properties strongly depend on the oxidation state is vanadium. Several oxidation states of vanadium can be found like V5+, V4+, V3+, V2+ of the 3d0, 3d1, 3d2, 3d3 electronic configuration, respectively. Recently we presented the potential application of V ions emission for luminescent nanothermometry, where V ions were incorporated into inorganic hosts, such as YAG (Y3Al5O12) (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018b) and LaGaO3 (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a). As it was shown its high susceptibility to the thermal changes enables to detect the local temperatures with satisfactory sensitivity (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). Depending on the host material different V oxidation states were found, namely V5+, V3+ and V5+, V4+, V3+, for YAG and LaGaO3 lattices, respectively. What is more, an immense impact of synthesis method and annealing temperature on crystalline size, dispersion factor of the particles, size distribution were presented (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b), which in turn lead to the presence of different V valence states, characterized by distinct luminescent properties and susceptibility to changes of local ion environment. Due to good spectral separation of emission bands of particular oxidation states of vanadium ions the qualitatively verification of their presence can be done basing on the analysis of the luminescent properties of vanadium doped phosphor. The V5+, V4+, and V3+ luminescence is related with V4+ → O2− CT transition (λem = 520 nm), broad band 2E → 2T2 d-d electronic transition (λem = 645 nm) and narrow line 1E2 → 3T1g d-d electronic transition (λem = 712 nm), respectively (Ryba-Romanowski et al., 1999a; Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b).

In the course of our previous studies it was found that broad emission band of V5+ with the maxima at around 497 nm (V4+ → O2− CT emission) predominates in the emission spectra (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). However, as it was already proved the 2E → 2T2 emission of V4+ ions is characterized by higher susceptibility to luminescence thermal quenching and hence reveals the best performance to non-contact readout. As it was already shown in the case of YAG nanocrystals, due to the spatial segregation of different vanadium oxidation states within the nanoparticle, the emission intensity ratio of V5+ to V3+ can be easily modulated through size of the nanoparticles. Moreover, the involvement of CA during the synthesis caused the reduction of oxidation state of vanadium substrate, namely from pentavalent to trivalent valence states, being observed by the changes of color of the solution, from yellow to blue, respectively (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). Citric acid is a complexing agent, which is highly soluble in polar solvents and widely used in the synthesis of nanoparticles, guaranteeing the incorporation of each metal into the material, maintaining local stoichiometry (Davar et al., 2013), which is possible due the presence of three carboxylic group (−COOH) and one hydroxyl group (−OH) in the CA chain (Gutierrez et al., 2015; Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). It is well-known as a reducing and capping agent, providing possibility of charge modulation, nano-sized particles and relatively good size distribution, due the high chemical stability, steric impediment and generation of electrostatic repulsive forces (Zhang and Gao, 2004; Thio et al., 2011; Davar et al., 2013; Gutierrez et al., 2015; Shinohara et al., 2018). However, the addition of PEG, entering into polyesterification with CA, leads to discoloration of the solution (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). This phenomenon may be explained as a decrease of reducing properties of CA, resulting from the interaction between carboxylic and hydroxyl group of CA and PEG, respectively. Another approach which was frequently used in terms of stabilization of oxidation state of vanadium ions in the crystals but never in the case of nanocrystals is charge compensation. In this paper the potential possibilities of the modulation of vanadium oxidation states by varying charge compensation process, annealing temperature and the choice of appropriate synthesis conditions have been presented. Employment of these modifications leads to the changes in vanadium valence states and in consequence modify spectroscopic properties, such as emission color.

The LaGaO3:xV nanocrystals have been successfully synthesized by the use of citric acid assisted sol-gel method. The first steps of preparation were carried out analogously to the previous synthesis of LaGaO3 (see Table S1) (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a). Lanthanum oxide (La2O3 with 99.999% purity from Stanford Materials Corporation), gallium nitrate nonahydrate [Ga(NO3)3·9H2O with 99.999% purity from Alfa Aesar], ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO3 with 99% purity from Alfa Aesar) and citric acid (CA, C6H8O7, 99.5+% purity from Alfa Aesar,) were used as substrates of the reaction. Stoichiometric amount of lanthanum oxide was dissolved in distilled water and ultrapure nitric acid (96%). The created lanthanum nitrate was recrystallized three times using small quantities of distilled water. After this, adequate quantities of Ga(NO3)3·9H2O and NH4VO3 were diluted in distilled water and added to aqueous solution of obtained lanthanum nitrate. The mixture was stirred with citric acid using magnetic stirrer and heated up to 90°C for 1 h to provide the metal complexation process. Afterwards, the solution was dried for 1 week at 90°C to create a resin. Finally, the nanocrystals were received by annealing the resin in air for 8 h at 800, 900, 1,000, and 1,100°C, respectively. The vanadium dopant was used in the amount of x = 0.1% in respect to number of moles of Ga3+ ions. The CA were used in different molar ratio in respect to all metals (M), namely 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 6:1, 8:1, and 10:1.

The LaGaO3:V nanocrystals with Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions as a charge compensators have been successfully obtained using the same Pechini method, which was exploited to synthesized the previous presented LaGaO3:V powders (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a). The lanthanum oxide was recrystallized. Appropriate quantities of Ga(NO3)3·9H2O, NH4VO3, magnesium nitrate heksahydrate [Mg(NO3)2·6H2O with 99.999% purity from Alfa Aesar] or calcium nitrate tetrahydrate [Ca(NO3)2·4H2O with 99.995% purity from Alfa Aesar] were added to the mixture of all reactants and stirred with citric acid for 1 h at 90°C, where the citric acid was used in the 6-fold excess in respect to total amount of metals moles. Than appropriate volume of PEG-200 (1 PEG-200: 1 CA) was dropped to the solution. The reaction was carried out for 2 h with simultaneous heating. After this synthesis the received solutions were dried for 1 week at 90°C. The powders of LaGaO3:V, Mg2+(Ca2+) were finally obtained by annealing in air for 8 h at 800°C. The concentration of V ions was 0.1% in respect to number of moles of Ga2+ ions, whereas the total amount of Mg2+ (Ca2+) was used in the ratio of 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, and 8:1 in respect to the vanadium ions.

Powder diffraction studies were carried out on PANalytical X'Pert Pro diffractometer equipped with Anton Paar TCU 1000 N Temperature Control Unit using Ni-filtered Cu Kα radiation (V = 40 kV, I = 30 mA).

Transmission electron microscopy images were obtained using the Tecnai G2 20 S/TEM Microscope from FEI Company. The microscope was equipped with a thermionic LaB6 emitter and EDS detector for elemental analysis. The study was conducted in the TEM mode at maximum voltage of 200 kV. Micrographs were taken at various magnifications, including high resolution images with lattice fringes.

The emission spectra were measured using the 266 nm excitation line from a laser diode (LD) and a Silver-Nova Super Range TEC Spectrometer form Stellarnet (1 nm spectral resolution) as a detector.

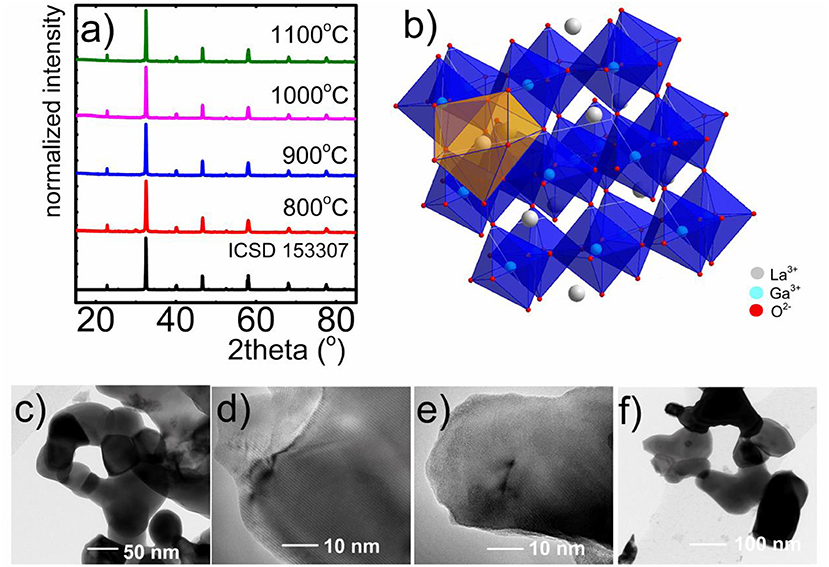

The phase purity and crystalline structure of obtained LaGaO3:V powders with different amounts of CA and the employment of charge compensating ions was examined using the XRD analysis (Figure 1a, see also Figures S1, S2). Moreover, the influence of annealing temperature on the LaGaO3 structure, especially on the grain size, was analyzed (Figures 1a,c-f). Comparing the reference peaks (ICSD 153307) with measured XRD patterns it was confirmed that obtained phosphors crystalized in orthorhombic structure and centrosymmetric Pbnm space group. Additional reflection peaks found for the sample annealed at 800°C, without charge compensation, originate from La2O3 and Ga2O3 impurities. These results confirm that the sol-gel citric acid-assisted synthesis with and without charge compensation allows to obtain the LaGaO3:V nanocrystals of high structural purity. The analyzed structure consists of 6-fold coordinated Ga3+ (GaO6)9− and 8-fold coordinated La3+ ions, where La3+ sites are situated between slightly tilted and distorted (GaO6)9− layers (Marti et al., 1994; Ryba-Romanowski et al., 1999a,b; Kamal et al., 2017; Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a) (Figure 1b). As it was mentioned in the previous work (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a), due the similarities in valence states and ionic radii between Ga3+ and V ions (0.76, 0.78, 0.72, and 0.54 Å Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a, for Ga3+, V3+, V4+, and V5+, respectively) V occupy octahedral site of Ga3+ ions in the LaGaO3 matrix. Representative TEM images of the nanocrystals (Figures 1c–f), which were synthesized using the citric acid-assisted sol-gel method reveal well-crystalized agglomerated nanoparticles. Additionally it can be noticed that this synthesis method provides higher degree of grains dispersion and their separation in respect to the previously described modified Pechini method (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a). According to our predictions the increase of annealing temperature results in the enlargement of the average grain size: from 66 nm for 800°C, 79 for 900°C, 114 nm for 1,000°C to 145 nm for 1,100°C. It is worth mentioning, that the highest grain size of LaGaO3:V annealed at 1,100°C is more than 2-fold smaller in respect to the counterpart synthesized using Pechini method (381.8 nm) (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a). However, the increase of CA does not cause the evident changes in grain size.

Figure 1. XRD patterns of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals synthesized by citric acid-assisted sol-gel method (M:CA 1:1) annealed at different temperatures (a); visualization of LaGaO3 perovskite structure (b); respective TEM images of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals with the 10-fold excess of citric acid, annealed at 800°C (c), 900°C (d), 1,000°C (e), and 1,100°C (f).

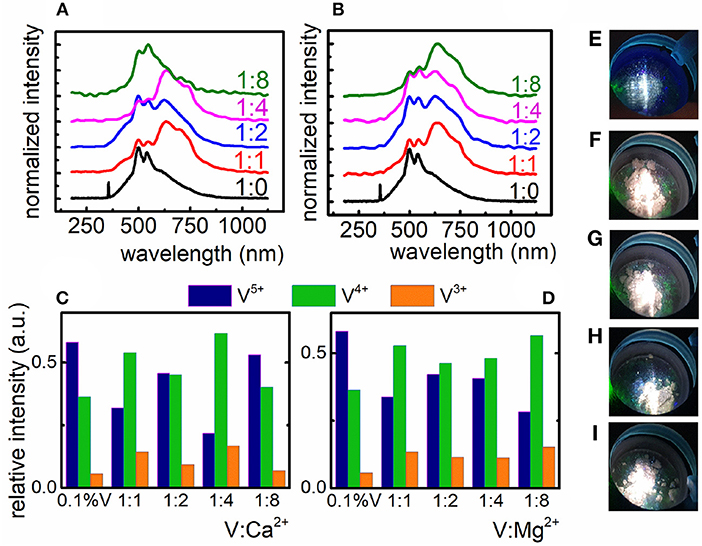

The first approach employed by us to control the valence state of vanadium ions was compensation method. Two series of nanocrystals with different molar ratio of Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions in respect to the V ions were prepared. Proposed charge compensation can be written as follows:

Two Ga3+ sites were substituted by one V4+ ion and one Ca2+/Mg2+ ion so that the excess electron could be transferred to the compensating ion. Taking into consideration the structural properties of compensated material, it is worth mentioning, that the introduction of even large excess of Ca2+/Mg2+ ions does not influence the changes of XRD patterns (Figure S1). According to our predictions, the introduction of Mg2+ and Ca2+ in the crystal structure caused the rise of the V4+ emission intensity (λem = 633 nm) in respect to the uncompensated counterpart (Figures 2A–D). Due to the fact that no structural changes can be found in the XRD pattern even for high Ca2+/Mg2+, the observed changes are the confirmation of the successful charge compensation and thus the increase of V4+ concentration. One can notice that even a small addition of Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions to the LaGaO3:0.1%V crystal lattice affects the shape of emission spectra (Figures 2C,D) significantly. It can be found that Mg2+ ions revealed better, in respect to the Ca2+ ions, performance to charge compensation which is reflected in the dominant emission of V4+ ions over the emission of V3+ and V5+ ions for each amount of compensating ion. However, the most satisfactory charge compensation was found in the case of incorporation of 8-fold excess of Mg2+ in respect to V (Figures 2B,D). This effect may be explained in terms of superior lability of Mg2+ ions in the lattice, which results from their smaller ionic radius (0.78 Å) compared to Ca2+ ions (1.06 Å). The impact of the amount of compensating ions on the emission intensity of the particular oxidation state of vanadium ions is presented in Figures 2C,D. In the case of Mg2+ gradual increase of its concentration causes gradual decrease of V5+ emission intensity and enhancement of V4+ intensity while V3+ becomes almost constant. The changes observed in the case of Ca2+ are rather irregular. The consequence of observed charge compensation is the modulation of emission color (Figures 2E–I). It is also worth noting that in the case of calcium ions there is a concentration limit (1:8), above which V5+ emission intensity becomes anew dominant (Figures 2A,C).

Figure 2. Influence of the Ca2+ (A) and Mg2+ (B) compensating ions on the V emission spectrum in LaGaO3 nanocrystals; relative emission intensity of the V ions after charge compensation with Ca2+ (C) and Mg2+ ions (D); emission color of uncompensated LaGaO3:V nanocrystals (E) and compensated LaGaO3:V nanocrystals with the V:Mg2+ ratio of 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8 (F–I), respectively.

The incorporation of compensating ions caused the enhancement of V4+ emission intensity, however the luminescence of both V5+ and V3+ ions is still observed and cannot be completely reduced. The contribution of V5+ emission intensity in the emission spectra of LaGaO3:V is relevant and that is why the emission color does not changes significantly (Figures 2E–I) indicating that charge compensation does not provide sufficient ability to modulation of vanadium oxidation states. Based on these results new approach to charge modulation was proposed.

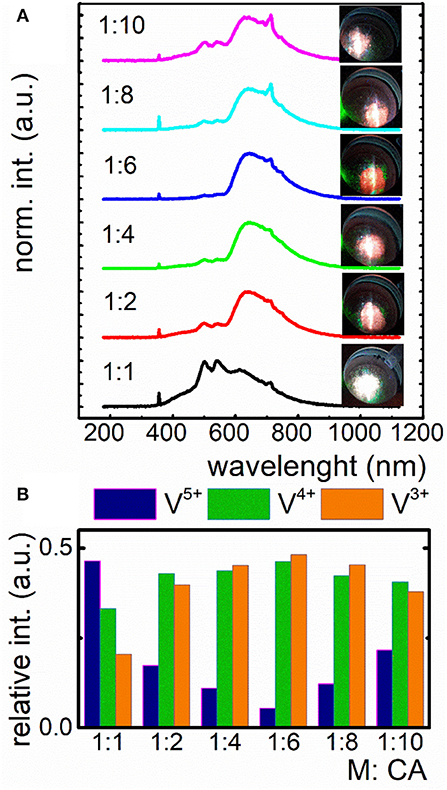

Taking advantage from the fact that PEG, which was used in the case of previously described Pechini method is well-known from its oxidizing properties and may lead to the increase of V5+ concentration, in the second approach we decided to use sol-gel method to eliminate PEG as a reagent, being involved in the resin creation. The issue was to involve all COOH groups to reduction reaction. Cit3− ions were used in different molar quantity in respect to the total amount of metal ions (M) in the lattice (Figure 3). To verify the capability of V oxidation states modulation by the CA concentration, the emission spectra of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals were recorded at −150°C under 266 nm excitation. Low measurement temperature provides the highest emission intensity, being to a lesser extent affected by lattice vibrations, reducing the luminescence temperature quenching (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018a,b). The employment of the same molar amounts of ions and CA caused the presence of three emitting V oxidation states, namely V5+, V4+, and V3+, with the predominant emission intensity of V5+. This phenomenon indicates that this molar ratio is insufficient to provide significant reduction of V5+. The employment of 2-fold excess of CA (1:2) leads to the apparent domination of V4+ emission and thereby the change of emission color (Figures 3A,B), pointing to the immense impact on the V luminescence properties. Increasing the quantity of capping agent to 6-fold excess in respect to metal ions, the V5+ emission intensity decreases with the simultaneously rise of V4+ and V3+ luminescence (Figure 3B), being a limit value, above which a reversed dependence occurs. This phenomenon determines the color output of LaGaO3:V, which changes from white to red, while the emission is being red-shifted (V4+ and V3+) and becomes whitish as the V5+ amount increases (Figure 3A, see also Figures S3, S5). It is worth noting that although initially with the increase of CA concentration the emission intensity of V5+ decreases in respect to the V4+ and V3+, above 1:8 ratio the V5+ emission band appears anew. The enhancement of V5+ luminescence may be due the fact, that higher content of Cit3− provides the stabilization of more positive charge on V. In turn the V charge lowering confirms the reducing properties of CA even in the nanoscale materials. On the other hand, as it was already proved in the case of nanocrystalline phosphors doped with vanadium ions the V5+ ions are mainly located in the surface part of the grains, while V4+ and V3+ in the core part (Kniec and Marciniak, 2018b). Therefore, the enhancement of the V5+ emission at higher CA concentration may be related with the higher dispersion of the LaGaO3 nanocrystals leading also to the higher separation of the grains. This is in agreement with the TEM images presented in Figure S4. The observed changes of the relative emission intensity of particular V oxidation state causes modulation of the emission color (Figures 3A,B).

Figure 3. Influence of the different amount of citric acid (CA) in respect to V ions on the emission spectrum of nanocrystalline LaGaO3:V and the corresponding emission color (A); contribution of emission intensity of particular V ions in the total luminescence of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals (B).

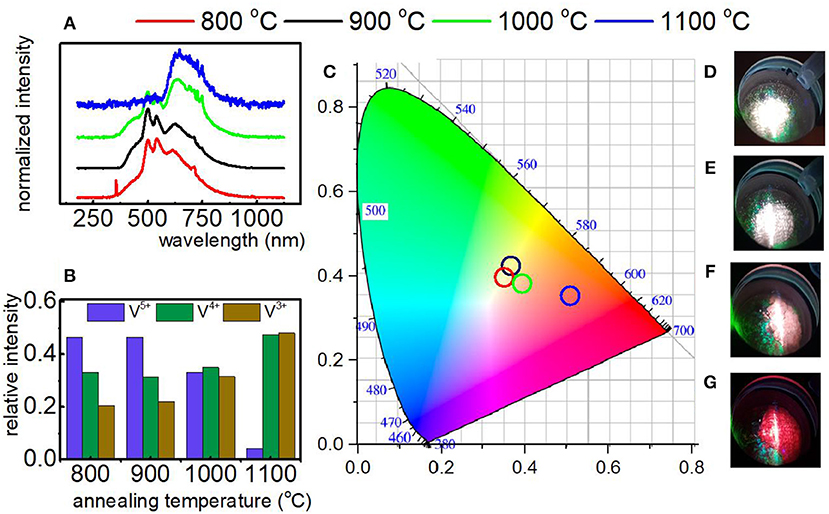

In the course of our studies it was found that in the case of YAG:V and LaGaO3:V nanocrystals the vanadium on its higher oxidation state is mainly located at the surface part of the grain. Therefore, in the last approach we verified either size of the nanocrystals may enable the reduction of the V5+ emission intensity in respect to the V4+ and V3+. The size of the nanocrystals was controlled by the annealing temperature for constant molar ratio of CA:V (1:1). As it can be observed the increase of grain size causes gradual increase of bands associated with the 2E → 2T2 and 1E2 → 3T1g electronic transitions of V4+ and V3+, respectively in respect to the V4+ → O2− band of V5+ (Figure 4A). This is due to the fact that the rise of grain size causes a decrease in the surface-to-volume ratio of the nanocrystals and thus a drop of the amount of emitting V5+ ions compared to V4+ and V3+ ions. The most apparent emission changes take part by the annealing temperature increase from 1,000 to 1,100°C, whereas least relevant are between 800 and 900°C (Figure 4B), being strictly related to enlargement of the grain size by 42.94 and 2.53 nm, respectively. Therefore, the emission color changes can be observed, ranging from white, connected with the domination of V5+ luminescence, trough pinkish, related to the presence of each V ions, ending on red color, originating from predominant V4+ and V3+ luminescence (Figures 4B,D–G). This in turn enables the modulation of color output of LaGaO3:V, which varies depending on the total contribution of each V ions in the luminescence (Figures 4B,D–G). The contribution of each Vn+ ions into total emission spectra was estimated by the calculation of the integrals in the range of 400–570, 580–675, and 680–750 nm integral emission intensity for V3+, V4+, and V5+, respectively. In addition, knowing the average grain size of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals, the possibility of establishment of the emission spectrum and, consequently, predict the color output was affirmed (Figure 4C). The same dependence, concerning the size effect on the V oxidation states was also observed for LaGaO3:V nanocrystals, where citric acid was incorporated in higher concentration (see Figure S3).

Figure 4. Emission spectrum of LaGaO3:V nanocrystals as a function of annealing temperature recorded at −150°C under 266 nm excitation (A); the relative emission of each V ions in the LaGaO3 nanocrystals annealed at different temperatures (B); the CIE 1,931 chromatic coordinates calculated for LaGaO3:V nanocrystals annealed at different temperatures (C); LaGaO3:V emission colors at −150°C after annealing at 800, 900, 1,000, and 1,100°C (D–G), respectively.

As it can be observed, that all presented approaches led to the decrease of V5+ emission intensity, however the last method, based on the modification of the sizes of the LaGaO3 nanocrystals, is the most efficient.

In this paper three approaches to stabilize and modulate the V oxidation states in LaGaO3 nanocrystals and thus their emission color have been demonstrated. It was found that in this perovskite lattice three different V valence states are present, namely V5+, V4+, and V3+, showing the emission, being related to the V4+ → O2− CT transition (λem = 520 nm), 2E → 2T2 (λem = 645 nm) and narrow line 1E2 → 3T1g (λem = 712 nm) d-d electronic transition, respectively.

Furthermore it was concluded that at −150°C under 266 irradiation V4+ ions exhibit broad band emission, whereas V3+ ions reveals narrow line luminescence. It was presented that three different approaches including the implementation of compensating ions, by altering the ratio of citric acid to metal ions and the tuning of the size of the nanocrystals in range 66–145 nm through change of annealing temperature in 800–1,100°C range may provide the ability to regulate the valence state of vanadium ions. It was found that in the case of charge compensation method the introducing of Mg2+ ions is much more efficient, due the similar ionic radius to V ions and higher lability of compensating ions in respect to Ca2+. In turn the citric acid-assisted synthesis, where CA was used in the excess in respect to total amount of metals in the lattice, leads to the significant increase of V4+ and V3+ luminescent intensity with the simultaneous improvement of nanocrystals separation and narrower size distribution in respect to the powders obtained using Pechini method. Basing on the fact, that particular oxidation states of V ions are localized in different part of the LaGaO3 nanocrystals, namely V5+ in the surface, V4+ and V3+ in the core part, respectively, the influence of the grain size of V emission intensity was investigated. The increase of the annealing temperature and thereby the size of the nanocrystals, leads to the decrease of V5+ luminescence and simultaneously causing the enhancement of V4+ and V3+ ones. The most significant V5+ emission changes are observed when the annealing temperature increase from 1,000 to 1,100°C, which corresponds to the enlargement of the grain size by 43 nm. All of the presented approaches provide the differences of V emission intensity, however the most efficient method based on the modification of the grain size, which is confirmed by the most apparent changes in LaGaO3:V color output. Taking into account that different oxidation states of vanadium ions possess favorable optical properties for i.e., lightning and luminescent thermometry, we believe that this study may be of relevant importance for further application of vanadium based nanocrystalline phosphors.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and the Supplementary Files.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The High Sensitive Thermal Imaging for Biomedical and Microelectronic Application project is carried out within the First Team programme of the Foundation for Polish Science co-financed by the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2019.00520/full#supplementary-material

Azkargorta, J., Marciniak, L., Iparraguirre, I., Balda, R., Strek, W., Barredo-Zuriarrain, M., et al. (2016). Influence of grain size and Nd3+ concentration on the stimulated emission of LiLa1−xNdxP4O12 crystal powders. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 63, 3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2016.07.016

Brik, M. G., Pan, Y. X., and Liu, G. K. (2011). Spectroscopic and crystal field analysis of absorption and photoluminescence properties of red phosphor CaAl12O19:Mn4+ modified by MgO. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 1452–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.11.117

Brik, M. G., Papan, J., Jovanović, D. J., and Dramićanin, M. D. (2016). Luminescence of Cr3+ ions in ZnAl2O4 and MgAl2O4 spinels: correlation between experimental spectroscopic studies and crystal field calculations. J. Lumin. 177, 145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.04.043

Buzea, C., Pacheco, I. I., and Robbie, K. (2007). Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity. Biointerphases 2, MR17–MR71. doi: 10.1116/1.2815690

Cao, R., Ceng, X., Huang, J., Xia, X., Guo, S., and Fu, J. (2016). A double-perovskite Sr2ZnWO6:Mn4+ deep red phosphor: synthesis and luminescence properties. Ceram. Int. 42, 16817–16821. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.07.173

Cao, R., Zhang, F., Xiao, H., Chen, T., Guo, S., Zheng, G., et al. (2018). Perovskite La2LiRO6:Mn4+ (R = Nb, Ta, Sb) phosphors: synthesis and luminescence properties. Inorganica Chim. Acta 483, 593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2018.09.015.

Chowdhury, S. R., and Yanful, E. K. (2010). Arsenic and chromium removal by mixed magnetite-maghemite nanoparticles and the effect of phosphate on removal. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 2238–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.06.003

Davar, F., Hassankhani, A., and Loghman-Estarki, M. R. (2013). Controllable synthesis of metastable tetragonal zirconia nanocrystals using citric acid assisted sol-gel method. Ceram. Int. 39, 2933–2941. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.09.067

Devi, P. S., Gafney, H. D., Petricevic, V., and Alfano, R. R. (1996). Synthesis and spectroscopic properties of (Cr4+) doped sol-gels. J. Non Cryst. Solids 203, 78–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3093(96)00336-5

Drabik, J., Cichy, B., and Marciniak, L. (2018). New type of nanocrystalline luminescent thermometers based on Ti3+/Ti4+ and Ti4+/Ln3+ (Ln3+ = Nd3+, Eu3+, Dy3+) luminescence intensity ratio. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 14928–14936. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b02328

Elzbieciak, K., Bednarkiewicz, A., and Marciniak, L. (2018). Temperature sensitivity modulation through crystal field engineering in Ga3+ co-doped Gd3Al5−xGaxO12:Cr3+, Nd3+ nanothermometers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.04.157

Felice, V., Dussardier, B., Jones, J. K., Monnom, G., and Ostrowsky, D. B. (2001). Chromium-doped silica optical fibres: influence of the core composition on the Cr oxidation states and crystal field. Opt. Mater. 16, 269–277. doi: 10.1016/S0925-3467(00)00087-2

Grinberg, M., Lesniewski, T., Mahlik, S., and Liu, R. S. (2017). 3d3 system–comparison of Mn4+ and Cr3+ in different lattices. Opt. Mater. 74, 93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2017.03.057

Gupta, S. K., Kadam, R. M., Natarajan, V., and Godbole, S. V. (2014). Oxidation state of manganese in zinc pyrophosphate: probed by luminescence and EPR studies. AIP Conf. Proc. 1591, 1699–1701. doi: 10.1063/1.4873082

Gutierrez, L., Aubry, C., Cornejo, M., and Croue, J. P. (2015). Citrate-coated silver nanoparticles interactions with effluent organic matter: influence of capping agent and solution conditions. Langmuir 31, 8865–8872. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02067

Kamal, C. S., Rao, T. K. V., Samuel, T., Reddy, P. V. S. S. S. N., Jasinski, J. B., Ramakrishna, Y., et al. (2017). Blue to magenta tunable luminescence from LaGaO3: Bi3+, Cr3+ doped phosphors for field emission display applications. RSC Adv. 7, 44915–44922. doi: 10.1039/C7RA08864G

Kniec, K., and Marciniak, L. (2018a). Spectroscopic properties of LaGaO3:V, Nd3+ nanocrystals as a potential luminescent thermometer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 21598–21606. doi: 10.1039/C8CP04080J

Kniec, K., and Marciniak, L. (2018b). The influence of grain size and vanadium concentration on the spectroscopic properties of YAG:V3+, V5+ and YAG: V, Ln3+ (Ln3+ = Eu3+, Dy3+, Nd3+) nanocrystalline luminescent thermometers. Sensors Actuators B Chem. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.02.189

Mao, Z. Y., and Wang, D. J. (2010). Color tuning of direct white light of lanthanum aluminate with mixed-valence europium. Inorg. Chem. 49, 4922–4927. doi: 10.1021/ic902538a

Mao, Z. Y., Wang, D. J., Lu, Q. F., Yu, W. H., and Yuan, Z. H. (2009). Tunable single-doped single-host full-color-emitting LaAlO3:Eu phosphor via valence state-controlled means. Chem. Commun. 2009, 346–348. doi: 10.1039/b814535k

Marciniak, L., Bednarkiewicz, A., and Strek, W. (2017). The impact of nanocrystals size on luminescent properties and thermometry capabilities of Cr, Nd doped nanophosphors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 238, 381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.07.080

Marti, W., Fischer, P., Altorfer, F., Scheel, H. J., and Tadin, M. (1994). Crystal structures and phase transitions of orthorhombic and rhombohedral RGaO3 (R = La, Pr, Nd) investigated by neutron powder diffraction. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 6, 127–135. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/6/1/014

Martínez-Martínez, R., García-Hipólito, M., Ramos-Brito, F., Hernández-Pozos, J. L., Caldiño, U., and Falcony, C. (2005). Blue and red photoluminescence from Al2O3:Ce3+:Mn2+ films deposited by spray pyrolysis. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 17, 3647–3656. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/17/23/016

Matin, M. A., Islam, M. M., Bredow, T., and Aziz, M. A. (2017). The effects of oxidation states, spin states and solvents on molecular structure, stability and spectroscopic properties of fe-catechol complexes: a theoretical study. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 7, 137–153. doi: 10.4236/aces.2017.72011

McKittrick, J., Shea, L. E., Bacalski, C. F., and Bosze, E. J. (1999). Influence of processing parameters on luminescent oxides produced by combustion synthesis. Displays 19, 169–172. doi: 10.1016/S0141-9382(98)00046-8

Pathak, C. S., and Mandal, M. K. (2011). Yellow light emission from Mn2+ doped ZnS nanoparticles. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. Rapid Commun. 5, 211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.physe.2008.04.013

Peng, M., and Hong, G. (2007). Reduction from Eu3+ to Eu2+ in BaAl2O4:Eu phosphor prepared in an oxidizing atmosphere and luminescent properties of BaAl2O4:Eu. J. Lumin. 127, 735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2007.04.012

Ryba-Romanowski, W., Golab, S., Dominiak-Dzik, G., and Berkowski, M. (1999a). Optical spectra of a LaGaO3 crystal singly doped with chromium, vanadium and cobalt. J. Alloys Compd. 288, 262–268. doi: 10.1016/S0925-8388(99)00117-6

Ryba-Romanowski, W., Golab, S., Dominiak-Dzik, G., Sokolska, I., and Berkowski, M. (1999b). “Growth and optical properties of chromium doped LaGaO3 crystal,” in Proceedings of SPIE–The International Society for Optical Engineering, 43–46. Available online at: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0032669535&partnerID=40&md5=318115d07d121bfee5802f921a39653c

Sato, Y., Kato, H., Kobayashi, M., Masaki, T., Yoon, D. H., and Kakihana, M. (2014). Tailoring of deep-red luminescence in Ca2SiO4:Eu2+. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7756–7759. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402520

Scharf, B., Clement, C. C., Zolla, V., Perino, G., Yan, B., Elci, S. G., et al. (2014). Molecular analysis of chromium and cobalt-related toxicity. Sci. Rep. 4:5729. doi: 10.1038/srep05729

Shinohara, S., Eom, N., Teh, E. J., Tamada, K., Parsons, D., and Craig, V. S. J. (2018). The Role of citric acid in the stabilization of nanoparticles and colloidal particles in the environment: measurement of surface forces between hafnium oxide surfaces in the presence of citric acid. Langmuir 34, 2595–2605. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b03116

Struve, B., and Huber, G. (1985). The effect of the crystal field strength on the optical spectra of Cr3+ in gallium garnet laser crystals. Appl. Phys. B Photophys. Laser Chem. 36, 195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00704574

Thio, B. J., Montes, M. O., Mahmoud, M. A., Lee, D. W., Zhou, D., and Keller, A. A. (2011). Mobility of capped silver nanoparticles under relevant conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 6985–6991. doi: 10.1021/es203596w

Trejgis, K., and Marciniak, L. (2018). The influence of manganese concentration on the sensitivity of bandshape and lifetime luminescent thermometers based on Y3Al5O12:Mn3+, Mn4+, Nd3+ nanocrystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 9574–9581. doi: 10.1039/c8cp00558c

Wang, M. Q., Li, H., He, Y. D., Wang, C., Tao, W. J., and Du, Y. J. (2012). Efficacy of dietary chromium (III) supplementation on tissue chromium deposition in finishing pigs. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 148, 316–321. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9369-x

Weber, M. J., and Riseberg, L. A. (1971). Optical spectra of vanadium ions in yttrium aluminum garnet. J. Chem. Phys. 55, 2032–2038. doi: 10.1063/1.1676370

Zhang, J., and Gao, L. (2004). Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline tin oxide by sol-gel method. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 1425–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2003.11.024

Zhang, J., Zhang, G. X., Cai, G. M., and Jin, Z. P. (2018). Reduction of Ce(IV) to Ce(III) induced by structural characteristics and performance characterization of pyrophosphate MgIn2P4O14-based phosphors. J. Lumin. 203, 590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.07.015

Keywords: vanadium, charge compensation, citric acid, luminescence, nanocrystals

Citation: Kniec K and Marciniak L (2019) Different Strategies of Stabilization of Vanadium Oxidation States in Lagao3 Nanocrystals. Front. Chem. 7:520. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00520

Received: 19 April 2019; Accepted: 08 July 2019;

Published: 23 July 2019.

Edited by:

Soumyajit Roy, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, IndiaReviewed by:

Yoshihito Hayashi, Kanazawa University, JapanCopyright © 2019 Kniec and Marciniak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karolina Kniec, ay5rbmllY0BpbnRpYnMucGw=; Lukasz Marciniak, bC5tYXJjaW5pYWtAaW50aWJzLnBs

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.