- Faculty of Materials Science and Chemistry, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China

Cation disordered rock-salt lithium-excess oxides are promising candidate cathode materials for next-generation electric vehicles due to their extra high capacities. However, one major issue for these materials is the distinct decline of discharge capacities during charge/discharge cycles. In this study, Al2O3 layers were coated on cation disordered Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO) using atomic layer deposition (ALD) method to optimize its electrochemical performance. The discharge capacity after 15 cycles increased from 228.1 to 266.7 mAh g−1 for LTMO after coated with Al2O3 for 24 ALD cycles, and the corresponding capacity retention enhanced from 79.7 to 90.9%. The improved cycling stability of the coated sample was ascribed to the alleviation of oxygen release and the inhibition on the undesirable side reactions. Our work has provided a new possible solution to address some of the capacity fading issues related to the cation disordered rock-salt cathode materials.

Introduction

Cathode materials with high energy densities are crucial for next generation of lithium-ion batteries, especially when used in hybrid and electric vehicles (Zu and Li, 2011; Goodenough and Park, 2013; Rui et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017; Lv et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). For this reason, Layer-structured Li-excess materials, which could deliver capacities as high as 300 mAh g−1, have been researched for more than 10 years (Lu et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2018). But these materials undergo irreversible O loss in the first cycle, which may cause structure densification and voltage degradation in subsequent cycles (Xu et al., 2011). Recently, cation disordered rock-salt Li-excess materials, sharing similar chemical compositions with layered Li-excess materials, have also attracted lots of attentions because of their high capacities (Yabuuchi et al., 2011, 2015, 2016a,b; Lee et al., 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018; Twu et al., 2015; Freire et al., 2016, 2017; Cambaz et al., 2018; Kitchaev et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019). Besides, it is reported that the O redox may undergo reversible reactions in the first cycle in this material (Wang et al., 2015), which provides the possibility to achieve reversible changes during the lengthy electrochemical cycles. However, many of these materials have problems in their cycling performances. Wang et al. prepared a cation disordered Li1.23Ni0.155Ru0.615O2 material, and the capacity drops from 295.3 to 250 mAh g−1 only after 5 charge-discharge cycles (Wang et al., 2017). Okada's group prepared another cation disordered Li1.2Mn0.4Ti0.4O2 material, but its capacity drops from 226 to about 200 mAh g−1 just after 6 cycles (Kitajou et al., 2016).

Similar problems happened to layered Li-excess materials, and some literatures have reported that atomic layer deposition (ALD) method may be an effective method to alleviate the problem. ALD is a powerful technique to precisely render a uniform and conformal layer at Å level on arbitrary substrate surfaces due to its pulsing and controllable reaction. Belharouak's team coated Li1.2Ni0.13Mn0.54Co0.13O2 porous powder with ultrathin Al2O3 film using ALD technique, and the coated material shows higher first cycle coulombic efficiency and improved cycling performance (Zhang et al., 2013). Xiao et al. reported that the AlPO4 coating layer by ALD can effectively protect the Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 against the attack from the electrolyte, and can significantly improve its initial coulombic efficiency and thermal stability (Xiao et al., 2017a). Meanwhile, Oxide-based coatings at the surface of different cathode materials via ALD method have been demonstrated to be very conformal and uniform as reported in the literatures (Zhao and Wang, 2012; Zhao et al., 2012; Zhao and Wang, 2013a,b), thus they can effectively prevent from the electrolyte attack for enhanced cycling stability of the coated cathode.

In this study, we coated a cation disordered rock-salt Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 material with different thicknesses of Al2O3 layers by ALD technique and studied their effects on the cycling stabilities. Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 is a typical cation disordered rock-salt material but with poor cycling performances (Kitajou et al., 2016; Yabuuchi et al., 2016a). In our previous study, we found that the valence of Mn in disordered materials may be lower than 3+ after the first cycle (Wang et al., 2015), and this low valence may cause Mn dissolution into the electrolyte (Nicolau et al., 2018). In this case, we infer that Al2O3 coating may be an effective method to increase the reversibility and cycling performances of this cation disordered material.

Experimental

Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 was synthesized by the traditional solid-state reaction using the precursors of Li2CO3 (99%, Alfa Aesar), Mn2O3 (98%, Alfa Aesar), and TiO2 (99%, Sigma-Aldrich). Stoichiometric amounts of precursors were ball-milled for 4 h and then pressed into a pellet. The pellet was calcinated at 900°C for 12 h in Ar, then pulverized and ball-milled at 300 rpm for 4 h. The obtained material was denoted as LTMO.

Coating was achieved by the Atomic Layer deposition (ALD) method using an Ensure Nanotech ALD system (LabNano-9100). During the ALD process, as-prepared LTMO sample was first placed in a home-made sample holder and heated to 200°C in the reaction chamber under ca. 1.0 mbar. Nitrogen with a flow rate of 20 sccm was used as the carrying and purge gas. The Al(CH3)3 and water were employed as aluminum and oxygen precursors, respectively. In each cycle, pulse time of Al(CH3)3 was controlled at 0.02 s, and exposure time water precursor was 0.02 s. 8 s nitrogen purge steps were used after Al(CH3)3 and water exposures. The LTMO sample was coated with Al2O3 layers for 16, 24, 40 ALD cycles. The coated samples were denoted as LTMO/nAl2O3, where n stands for the number of ALD cycles.

Morphologies and crystal structures of LTMO with or without Al2O3 layers were analyzed by scanning electron microscope (SEM, SU 8010) and powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance), respectively. High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscope (HRTEM, TF 20) was used to record detailed crystalline structures of the samples. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALab 250Xi) with monochromatic Al K-α radiation was carried out to investigate the valences of the species in the samples.

To fabricate the cathode electrode, different Al2O3-coated LTMO samples were firstly ball-milled with Ketjen black at 150 rpm for 4 h, then manually mixed with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) binder. The mixture was rolled into a thin film, in which the weight ratios of LTMO/nAl2O3, Ketjen black, and PTFE are 70: 20: 10. The surface mass density of each electrode film is about 4.4 mg cm−2. Cells were assembled according to our previous study (Wang et al., 2015). Typically, a two electrode swagelok cell was fabricated using the Al2O3-coated LTMO thin film and lithium foil as the working electrode and the counter electrode, respectively. Borosilicate glass fiber membrane (Whatman) was used as the separator, and 1 M solution of LiPF6 dissolved in ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (1:1 by volume) was used as the electrolyte. All cells were cycled on an LANHE CT2001A system (Wuhan LAND Electronics Co.) between 4.8 and 1.5 V with a current density of 10 mA g−1 at room temperature. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data were recorded using a Gamry Reference 3,000 equipment. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was measured on a CHI760E electrochemical workstation with the scanning rate of 0.5 mV s−1 and the potential range of 4.8–1.5 V.

Results and Discussion

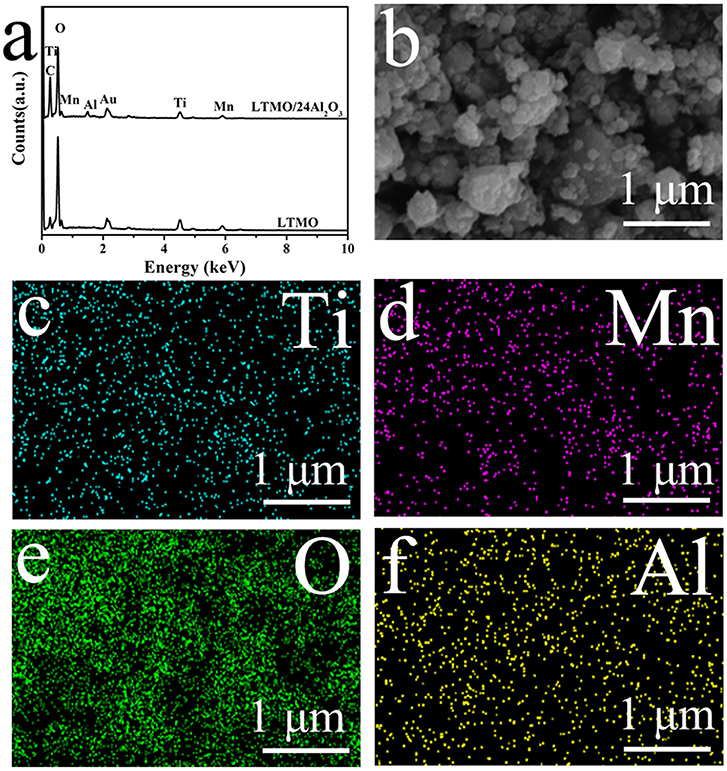

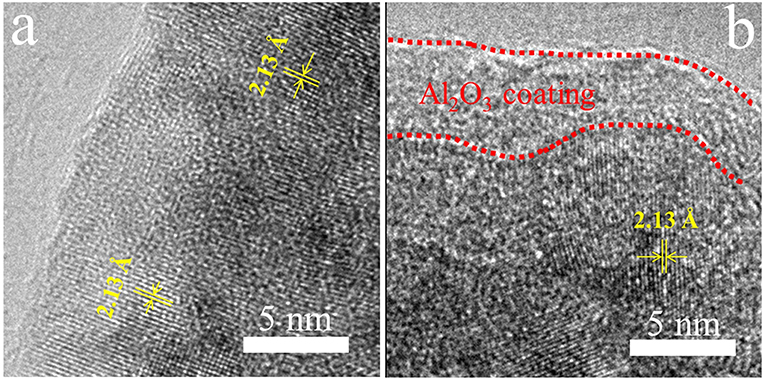

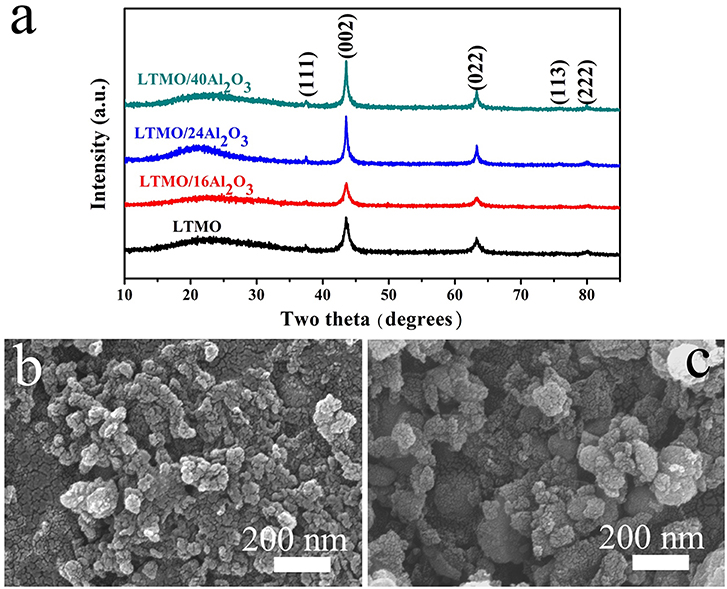

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples are shown in Figure 1a, and all the results correspond well to the disordered rock-salt structure. According to previous studies, cations are randomly placed on the 4b position (1/2, 1/2, 1/2), and the O atom is placed on the 4a position (0, 0, 0) (Wang et al., 2015). In cation disordered rock-salt materials, Li excess could build the 0-TM channels, through which Li ions could move out and back into the cathode material (Lee et al., 2015). According to the XRD patterns, no signal of Al2O3 is detected, and the reason may be that the amount of coated Al2O3 is too small or the coated Al2O3 is amorphous. The morphologies of LTMO before and after Al2O3 coating are shown in Figures 1b,c. No obvious differences are observed, indicating the coated Al2O3 particle may be too small to be surveyed in SEM. Energy Dispersive Spectrometers of the two samples are shown in Figure 2a. The characteristic peak of Al element could clearly be observed in the LTMO/24Al2O3 sample, while didn't show up in the LTMO sample. The LTMO/24Al2O3 sample was further examined by the elemental mapping experiments. and the results are shown in Figures 2b-f. Results show that Ti, Mn, O and Al elements distribute uniformly in the sample, which infer the Al2O3 layer exists uniformly in the sample.

Figure 1. (a) XRD pattern of the bare LTMO and different Al2O3-coated LTMO; SEM image of (b) LTMO and (c) LTMO/24Al2O3.

In order to directly observe the coating Al2O3 layers on the surface of LTMO particles, we investigate bare LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3 samples using high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). Figure 3a is the HR-TEM image of bare LTMO particles, showing well-defined lattice fringes in the surface region as well as those in the bulk region. In contrast, an obvious coating film in the surface region is clearly observed for LTMO/24Al2O3 sample (Figure 3b). It is different from the inner areas, and we infer it may be the Al2O3 coating layer. The thickness of the coating layer is around 3–5 nm.

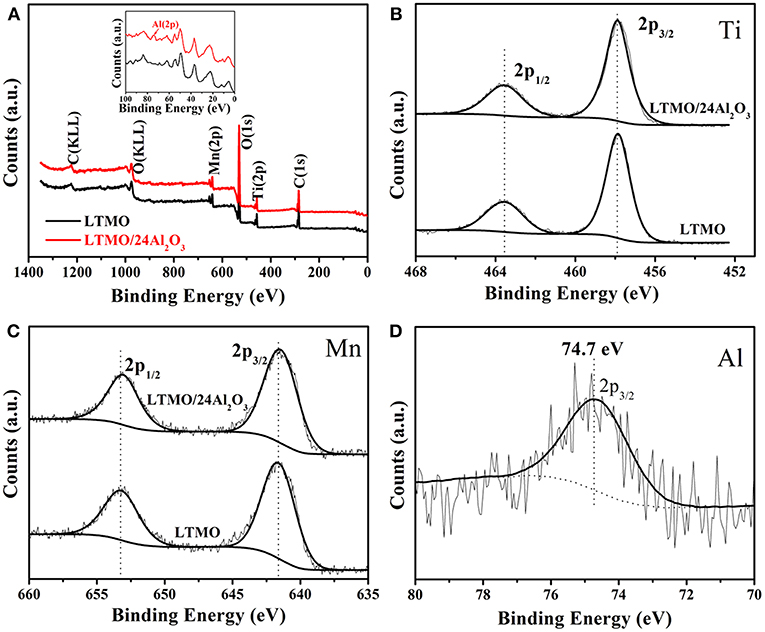

In order to confirm Al2O3 layer exists on the sample surfaces, XPS was used to probe the surface compositions of the LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3. All spectra were calibrated with the C 1s peak at 284.6 eV. Figure 4A presents the elemental XPS spectra of LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3 samples, showing both samples contain the characteristic peaks of Ti, Mn, O, and C. From the partial enlarged figure (inset of the Figure 4A), the elemental peak of Al is only observed in the LTMO/24Al2O3 spectrum. The core level binding energies of Ti are aligned at 457.9 eV (2p3/2) and 463.6 eV (2p1/2) (Figure 4B), which is in good agreement with Ti4+ ions in other titanium-based compounds (Kim et al., 2017). The Mn 2p XPS spectra of LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3 reveal peaks at 641.6 eV and 653.2 eV (Figure 4C), which are characteristic peaks of Mn3+ 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 (Das et al., 2011, 2013). This result confirms the valences of Mn in both samples are 3+. The Al 2p3/2 core level XPS spectrum displays a binding energy of 74.7 eV for the LTMO/24Al2O3 (Figure 4D), affirming that the chemical composition of the surface coating is Al2O3 for the LTMO/24Al2O3 sample.

Figure 4. (A) XPS survey spectrum and core level spectra of transition metals of LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3: (B) Ti 2p; (C) Mn 2p; (D) Al 2p.

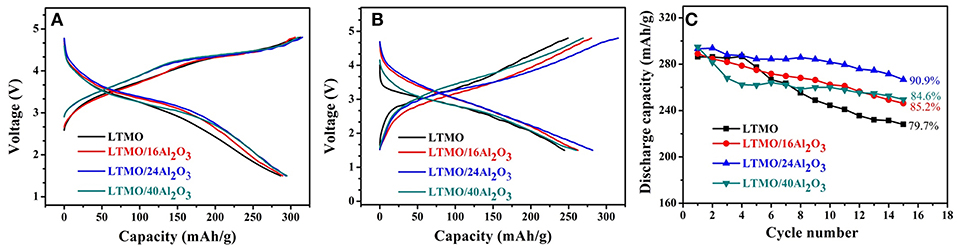

The charge and discharge profiles of uncoated and coated LTMO samples for the first cycle are shown in Figure 5A, showing all the samples have the identical profiles except for the voltage platform and capacity. It is obviously seen that all the coated LTMO samples have higher first discharge plateau and coulombic efficiency, and we think this may be the effect of Al2O3 layer. Though the O reaction in LTMO may happen in the form of O redox, there might still be little amount of oxygen release in the first cycle. We infer the Al2O3 layer may alleviate this oxygen release and improve the O reaction reversibility, thus improve the discharge plateau and coulombic efficiency. The charge and discharge profiles for the 10th cycle are shown in Figure 5B, and the LTMO/24Al2O3 sample presents the largest discharge capacity. Figure 5C shows the cycling stability of the pristine and ALD coated samples. Bare LTMO shows an initial discharge capacity of 286.3 mAh g−1 (818.6 Wh kg−1) and the capacity drops rapidly to 228.1 mAh g−1 (587.7 Wh kg−1) after 15 cycles, which is only 79.7% for its initial discharge capacity. After coated with Al2O3 for 16 ALD cycles, an initial discharge of 289.1 mAh g−1 (856.6 Wh kg−1) is observed and the capacity retention reaches 85.2%. It is worth noting that the LTMO/24Al2O3 sample could deliver a capacity of 293.4 mAh g−1 and energy density of 884.5 Wh kg−1 in the first cycle. After 15 cycles, the capacity and energy density could still maintain 266.7 mAh g−1 and 709.5 Wh kg−1, respectively. And the capacity retention after 15 cycles is 90.9%, which is 11.2% higher than that of the pristine LTMO. Besides, the coulombic efficiencies also increased from 91.5 to 93.0% after the 24 cycles ALD coating. However, further increasing the ALD cycle numbers of coated Al2O3, the inferior performance for LTMO/40Al2O3 is obtained, and the capacity retention decreases to 84.6%. The reason should be the thick insulated Al2O3 layer may inhibit the electric and ionic transportation (Jung et al., 2010). Based on above results, it can be concluded that proper thickness of Al2O3 layer can greatly improve the cycling stability of LTMO electrodes, while the over-thick Al2O3 layer leads to the reverse effect on the electrode.

Figure 5. (A) Initial charge-discharge curves; (B) 10th charge-discharge curves; (C) cyclic performance of the pristine LTMO and Al2O3-coated LTMO electrodes.

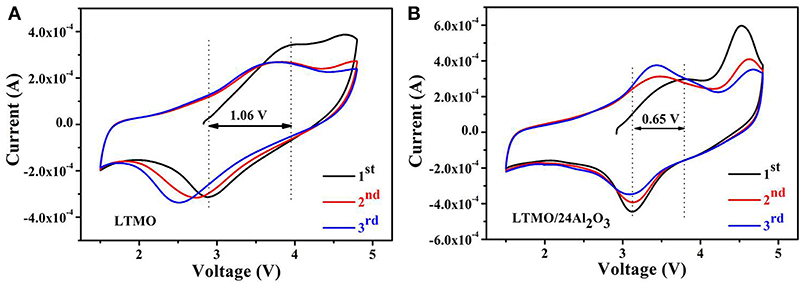

Figure 6 show the cyclic voltammetric (CV) curves of LTMO and LTMO/24Al2O3 samples in the first three cycles at a scanning rate of 0.5 mV s−1. For the LTMO electrode (shown in the Figure 6A), the anodic peaks located at about 3.95 V corresponds to the oxidation of Mn3+ to Mn4+ (Xiao et al., 2017b) during the initial charge process. Another anodic peaks at around 4.63 V may be attributed to the oxygen loss from the crystal structure and formation of or O2 from O2−, which is usually observed on the Mn-based Li-excess cathode materials (Ma et al., 2016). While this peak disappears in the subsequent cycles, showing the irreversibility of the oxidation of O2− in the LTMO electrode. In the following cathodic process, the peak at around 2.89 V corresponds to the reduction of Mn4+ to Mn3+ (Kong et al., 2017). It can be clearly seen that this peak moves to lower voltage range in the following cycles, indicating the decreasing of the valence of Mn. As to LTMO/24Al2O3 (shown in Figure 6B), two differences can be observed. First, the anodic peak at around 4.63 V still can be observed in the second and third cycles. Second, the cathodic peak located at around 3.17 V doesn't move during the cycles. These results infer the oxygen loss from the crystal structure in LTMO/24Al2O3 is milder than in LTMO. As a result, the Mn redox reaction in LTMO/24Al2O3 happens between Mn4+ and Mn3+. While Mn in pristine LTMO reduces to lower than 3+ because of the O loss and related densification in the first cycle.

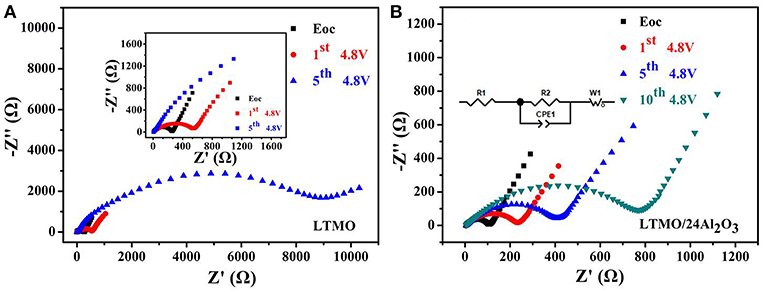

In order to investigate the intrinsic factor of the improvement in the electrochemical performance of the LTMO/24Al2O3 sample, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) were collected on the bare LTMO and the LTMO/24Al2O3 after charging to 4.8 V and resting for 4 h at the different cycles, shown in Figures 7A,B, respectively. All the Nyquist plots comprised a depressed semicircle from high to middle frequencies and an inclined line at low frequency. The simulated equivalent circuit is presented as an inset. The R1 represents the Ohmic resistance coming from the separator, electrolyte and other components. The semicircle shows the charge transfer reaction composed of a charge transfer resistor (R2) and a constant phase element (CPE1), the inclined line stands for the Warburg diffusion impedance (ZW). The LTMO/24Al2O3 electrode shows the smaller R2 of 101.6 Ω before cycling and remains at 228.4 Ω, 433.8 Ω and 851.3 Ω after 1st, 5, and 10th cycling, respectively. Nevertheless, the much larger R2 values of the LTMO electrode are seen (i.e., 255.8 Ω before cycling and changed to 557.7 Ω after 1st cycling, even to 10,207 Ω for the 5th cycling, respectively), which infer complex side reactions may happen on the electrode surface and these reaction products may have blocked the ionic transfer process and result in worse cycling performance. Thus, it can be concluded that an appropriate thickness of Al2O3 layer guarantees the stable charge transfer and structural integrity of the cathode electrodes, which led to good cycling performance.

Figure 7. EIS profiles of (A) LTMO and (B) LTMO/24Al2O3 at the charge state of 4.8 V in the different cycles; inset: an equivalent-circuit simulation model.

Conclusion

ALD technique was successfully used to deposit ultrathin Al2O3 coating layer onto the surface of the LTMO particles. Comparing with the uncoated LTMO, ALD process can reduce the polarization, restrain the undesirable side reactions, and suppress the increasing charge transfer resistance during cycling, which results in the significantly improved electrochemical performance of Al2O3-coated LTMO (LTMO/24Al2O3). The controllable ALD technology provides a promising guideline for the surface modification of disordered rock-salt cathode materials with high electrochemical performance.

Author Contributions

RW conceived and designed the research. BaH carried out the experiments. YG and HW contributed to the discussion. RW wrote the manuscript with the help of BeH. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51702294 and 51702295).

References

Cambaz, M. A., Vinayan, B. P., Euchner, H., Johnsen, R. E., Guda, A. A., Mazilkin, A., et al. (2018). Design of nickel-based cation-disordered rock-salt oxides: the effect of transition Metal (M = V, Ti, Zr) Substitution in LiNi0.5M0.5O2 binary systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 21957–21964. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b02266

Das, R., Jaiswal, A., Adyanthaya, S., and Poddar, P. (2011). Effect of particle size and annealing on spin and phonon behavior in TbMnO3. J. Appl. Phys.109:064309. doi: 10.1063/1.3563571

Das, R., Jaiswal, A., and Poddar, P. (2013). Static and dynamic magnetic properties and interplay of Dy3+, Gd3+ and Mn3+ spins in orthorhombic DyMnO3 and GdMnO3 nanoparticles. J. Phys. D. 46:045301. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/46/4/045301

Freire, M., Kosova, N. V., Jordy, C., Chateigner, D., Lebedev, O. I., Maignan, A., et al. (2016). A new active Li-Mn-O compound for high energy density Li-ion batteries. Nat. Mater.15, 173–177. doi: 10.1038/nmat4479

Freire, M., Lebedev, O. I., Maignan, A., Jordy, C., and Pralong, V. (2017). Nanostructured Li2MnO3: a disordered rock salt type structure for high energy density Li ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 21898–21902. doi: 10.1039/c7ta07476j

Goodenough, J. B., and Park, K. S. (2013). The Li-ion rechargeable battery: a perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1167–1176. doi: 10.1021/ja3091438

Hu, E., Yu, X., Lin, R., Bi, X., Lu, J., Bak, S., et al. (2018). Evolution of redox couples in Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials and mitigation of voltage fade by reducing oxygen release. Nat. Energy 3, 690–698. doi: 10.1038/s41560-018-0207-z

Jung, Y. S., Cavanagh, A. S., Dillon, A. C., Groner, M. D., George, S. M., and Lee, S.-H. (2010). Enhanced stability of LiCoO2 cathodes in lithium-ion batteries using surface modification by atomic layer deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A75–A81. doi: 10.1149/1.3258274

Kim, D., Quang, N. D., Hien, T. T., Chinh, N. D., Kim, C., and Kim, D. (2017). 3D inverse-opal structured Li4Ti5O12 Anode for fast Li-Ion storage capabilities. Electr. Mater. Lett. 13, 505–511. doi: 10.1007/s13391-017-7101-x

Kitajou, A., Tanaka, K., Miki, H., Koga, H., Okajima, T., and Okada, S. (2016). Improvement of cathode properties by lithium excess in disordered rocksalt Li2+2xMn1−xTi1−xO4. Electrochemistry 84, 597–600. doi: 10.5796/electrochemistry.84.597

Kitchaev, D. A., Lun, Z., Richards, W. D., Ji, H., Clément, R. J., Balasubramanian, M., et al. (2018). Design principles for high transition metal capacity in disordered rocksalt Li-ion cathodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 2159–2171. doi: 10.1039/c8ee00816g

Kong, J.-Z., Zhai, H.-F., Qian, X., Wang, M., Wang, Q.-Z., Li, A.-D., et al. (2017). Improved electrochemical performance of Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 cathode material coated with ultrathin ZnO. J. Alloys Compd. 694, 848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.10.045

Lee, J., Kitchaev, D. A., Kwon, D.-H., Lee, C. W., Papp, J. K., Liu, Y. S., et al. (2018). Reversible Mn2+/Mn4+ double redox in lithium-excess cathode materials. Nature 556, 185–190. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0015-4

Lee, J., Papp, J. K., Clement, R. J., Sallis, S., Kwon, D. H., Shi, T., et al. (2017). Mitigating oxygen loss to improve the cycling performance of high capacity cation-disordered cathode materials. Nat. Commun. 8:981. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01115-0

Lee, J., Seo, D.-H., Balasubramanian, M., Twu, N., Li, X., and Ceder, G. (2015). A new class of high capacity cation-disordered oxides for rechargeable lithium batteries: Li–Ni–Ti–Mo oxides. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 3255–3265. doi: 10.1039/c5ee02329g

Lee, J., Urban, A., Li, X., Su, D., Hautier, G., and Ceder, G. (2014). Unlocking the potential -disordered oxides for rechargeable lithium batteries. Science 343, 519–522. doi: 10.1126/science.1246432

Lu, Z., Beaulieu, L. Y., Donaberger, R. A., Thomas, C. L., and Dahn, J. R. (2002). Synthesis, Structure, and Electrochemical Behavior of Li[NixLi1/3–2x/3Mn2/3−x/3]O2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A778–A791. doi: 10.1149/1.1471541

Lv, Z., Luo, Y., Tang, Y., Wei, J., Zhu, Z., Zhou, X., et al. (2018). Editable Supercapacitors with Customizable stretchability based on mechanically strengthened ultralong MnO2 nanowire composite. Adv. Mater. 30:1704531. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704531

Ma, Q., Li, R., Zheng, R., Liu, Y., Huo, H., and Dai, C. (2016). Improving rate capability and decelerating voltage decay of Li-rich layered oxide cathodes via selenium doping to stabilize oxygen. J. Power Sources 331, 112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.08.137

Nicolau, B. G., Petronico, A., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Ghadar, Y., Haasch, R. T., Soares, J. A. N. T., et al. (2018). Controlling interfacial properties of lithium-ion battery cathodes with alkylphosphonate self-assembled monolayers. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5:1701292. doi: 10.1002/admi.201701292

Rui, X., Sun, W., Wu, C., Yu, Y., and Yan, Q. (2015). An advanced sodium-ion battery composed of carbon coated Na3V2(PO4)3 in a porous graphene network. Adv. Mater. 27, 6670–6676. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502864

Tan, H., Xu, L., Geng, H., Rui, X., Li, C., and Huang, S. (2018). Nanostructured Li3V2(PO4)3 Cathodes, Small 14:1800567. doi: 10.1002/smll.201800567

Twu, N., Li, X., Urban, A., Balasubramanian, M., Lee, J., and Liu, L. (2015). Designing new lithium-excess cathode materials from percolation theory: nanohighways in LixNi2−4x/3Sbx/3O2. Nano Lett. 15, 596–602. doi: 10.1021/nl5040754

Wang, R., He, X., He, L., Wang, F., Xiao, R., Gu, L., et al. (2013). Atomic structure of Li2MnO3 after partial delithiation and re-lithiation. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 1358–1367. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201200842

Wang, R., Li, X., Liu, L., Lee, J., Seo, D.-H., Bo, S.-H., et al. (2015). A disordered rock-salt Li-excess cathode material with high capacity and substantial oxygen redox activity: Li1.25Nb0.25Mn0.5O2. Electrochem. Commun. 60, 70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2015.08.003

Wang, R., Li, X., Wang, Z., and Zhang, H. (2017). Electrochemical analysis graphite/electrolyte interface in lithium-ion batteries: p-Toluenesulfonyl isocyanate as electrolyte additive. Nano Energy 34, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.02.037

Wang, X., Huang, W., Tao, S., Xie, H., Wu, C., Yu, Z., et al. (2017). Attainable high capacity in Li-excess Li-Ni-Ru-O rock-salt cathode for lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 359, 270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.05.070

Xiao, B., Liu, H., Liu, J., Sun, Q., Wang, B., Kaliyappan, K., et al. (2017a). Nanoscale manipulation of spinel lithium nickel manganese oxide surface by multisite Ti occupation as high-performance cathode. Adv. Mater. 29:1703764. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703764

Xiao, B., Wang, B., Liu, J., Kaliyappan, K., Sun, Q., Liu, Y., et al. (2017b). Highly stable Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 enabled by novel atomic layer deposited AlPO4 coating. Nano Energy 34, 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.02.015

Xu, B., Fell, C. R., Chi, M., and Meng, Y. S. (2011). Identifying surface structural changes in layered Li-excess nickel manganese oxides in high voltage lithium ion batteries: A joint experimental and theoretical study. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2223–2233. doi: 10.1039/c1ee01131f

Yabuuchi, N., Nakayama, M., Takeuchi, M., Komaba, S., Hashimoto, Y., Mukai, T., et al. (2016a). Origin of stabilization and destabilization in solid-state redox reaction of oxide ions for lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 7:13814. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13814

Yabuuchi, N., Takeuchi, M., Komaba, S., Ichikawa, S., Ozaki, T., and Inamasu, T. (2016b). Synthesis and electrochemical properties of Li1.3Nb0.3V0.4O2 as a positive electrode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Chem. Commun. 52, 2051–2054. doi: 10.1039/c5cc08034g

Yabuuchi, N., Takeuchi, M., Nakayama, M., Shiiba, H., Ogawa, M., Nakayama, K., et al. (2015). High-capacity electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries: Li3NbO4-based system with cation-disordered rocksalt structure. PNAS 112, 7650–7655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504901112

Yabuuchi, N., Yoshii, K., Myung, S. T., Nakai, I., and Komaba, S. (2011). Detailed studies of a high-capacity electrode material for rechargeable batteries, Li2MnO3-LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4404–4419. doi: 10.1021/ja108588y

Yu, X., Lyu, Y., Gu, L., Wu, H., Bak, S.-M., Zhou, Y., et al. (2014). Understanding the rate capability of high-energy-density li-rich layered Li1.2Ni0.15Co0.1Mn0.55O2 cathode materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 4:1300950. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201300950

Zhang, X., Belharouak, I., Li, L., Lei, Y., Elam, J. W., Nie, A., et al. (2013). Structural and Electrochemical Study of Al2O3 and TiO2 Coated Li1.2Ni0.13Mn0.54Co0.13O2 Cathode Material Using ALD. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 1299–1307. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201300269

Zhang, X., Rui, X., Chen, D., Tan, H., Yang, D., Huang, S., et al. (2019). Na3V2(PO4)3: an advanced cathode for sodium-ion batteries, Nanoscale 11, 2556–2576. doi: 10.1039/C8NR09391A

Zhao, E., He, L., Wang, B., Li, X., Zhang, J., Wu, Y., et al. (2019). Structural and mechanistic revelations on high capacity cation-disordered Li-rich oxides for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 16, 354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2018.06.016

Zhao, J., Qu, G., Flake, J. C., and Wang, Y. (2012). Low temperature preparation of crystalline ZrO2 coatings for improved elevated-temperature performances of Li-ion battery cathodes. Chem. Commun. 48, 8108–8110. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33522k

Zhao, J., and Wang, Y. (2012). Ultrathin surface coatings for improved electrochemical performance of lithium ion battery electrodes at elevated temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 11867–11876. doi: 10.1021/jp3010629

Zhao, J., and Wang, Y. (2013a). Atomic layer deposition of epitaxial ZrO2 coating on LiMn2O4 nanoparticles for high-rate lithium ion batteries at elevated temperature. Nano Energy 2, 882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2013.03.005

Zhao, J., and Wang, Y. (2013b). Surface modifications of Li-ion battery electrodes with various ultrathin amphoteric oxide coatings for enhanced cycleability. J. Solid State Electrochem. 17, 1049–1058. doi: 10.1007/s10008-012-1962-6

Keywords: lithium-ion batteries, cathode, cation disorder, rock-salt, Li-excess

Citation: Huang B, Wang R, Gong Y, He B and Wang H (2019) Enhanced Cycling Stability of Cation Disordered Rock-Salt Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 Material by Surface Modification With Al2O3. Front. Chem. 7:107. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00107

Received: 25 December 2018; Accepted: 11 February 2019;

Published: 04 March 2019.

Edited by:

Yuxin Tang, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeReviewed by:

Xianhong Rui, Guangdong University of Technology, ChinaJianqing Zhao, Soochow University, China

Renheng Wang, Shenzhen University, China

Copyright © 2019 Huang, Wang, Gong, He and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rui Wang, d2FuZ3J1aUBjdWcuZWR1LmNu

Beibei He, YmFieWZseUBtYWlsLnVzdGMuZWR1LmNu

Baojun Huang

Baojun Huang Rui Wang

Rui Wang Huanwen Wang

Huanwen Wang