94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem., 04 April 2018

Sec. Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00098

This article is part of the Research TopicVirtual Drug DesignView all 24 articles

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) plays a pivotal role in inflammatory response. Dysregulation of TNF can lead to a variety of disastrous pathological effects, including auto-inflammatory diseases. Antibodies that directly targeting TNF-α have been proven effective in suppressing symptoms of these disorders. Compared to protein drugs, small molecule drugs are normally orally available and less expensive. Till now, peptide and small molecule TNF-α inhibitors are still in the early stage of development, and much more efforts should be made. In a previously study, we reported a TNF-α inhibitor, EJMC-1 with modest activity. Here, we optimized this compound by shape screen and rational design. In the first round, we screened commercial compound library for EJMC-1 analogs based on shape similarity. Out of the 68 compounds tested, 20 compounds showed better binding affinity than EJMC-1 in the SPR competitive binding assay. These 20 compounds were tested in cell assay and the most potent compound was 2-oxo-N-phenyl-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide (S10) with an IC50 of 14 μM, which was 2.2-fold stronger than EJMC-1. Based on the docking analysis of S10 and EJMC-1 binding with TNF-α, in the second round, we designed S10 analogs, purchased seven of them, and synthesized seven new compounds. The best compound, 4e showed an IC50-value of 3 μM in cell assay, which was 14-fold stronger than EJMC-1. 4e was among the most potent TNF-α organic compound inhibitors reported so far. Our study demonstrated that 2-oxo-N-phenyl-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide analogs could be developed as potent TNF-α inhibitors. 4e can be further optimized for its activity and properties. Our study provides insights into designing small molecule inhibitors directly targeting TNF-α and for protein–protein interaction inhibitor design.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), an important cytokine mediator involved in inflammatory responses, is commonly used as a marker for many inflammatory disorders (Wajant et al., 2003). Antibodies that directly targeting TNF-α have achieved success in the treatment of inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis (Bongartz et al., 2005; Jacobi et al., 2006). However, these biologics possess the possibility to cause anti-antibody immune responses and weaken the immune system to opportunistic infections (Scheinfeld, 2004; Ai et al., 2015).

Thus, developing inhibitors to block TNF-α is still of great importance. Zhu et al. have reported several rationally designed proteins that directly bound to TNF-α. They grafted three key residues from a virus viral 2L protein to a de novo designed small protein DS119, and then optimized their residues at the interface, which provided some small proteins that bind TNF-α with sub-micromolar affinities (Zhu et al., 2016). Other than small proteins, bicyclic peptides and helical peptides were also designed as peptidic antagonists of TNF-α (Lian et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013).

In addition to peptide inhibitors, small molecular inhibitors that directly targeting TNF-α have also been discovered (Leung et al., 2012; Davis and Colangelo, 2013; Shen et al., 2014). Suramin was thought to be the first small compound inhibitor that directly disrupts the interactions between TNF-α and its receptor (TNFR) (Grazioli et al., 1992). But its potency was too low to be used in clinic (Alzani et al., 1993). No breakthrough was made until 2005, when SPD304 was reported as the first potent small molecule inhibitor that directly targeting TNF-α, with an IC50 of 22 μM by ELISA. And the co-crystal structure of SPD304 in complex with TNF-α dimer was solved (He et al., 2005). However, as the 3-alkylindole moiety of SPD304 can be metabolized by cytochrome P450s to produce toxic electrophilic intermediates, its further applications in vivo is limited (Sun and Yost, 2008). After that, several novel TNF-α inhibitors were discovered using structure-based virtual screening (VS) of different chemical libraries. Chan et al. identified two compounds using high-throughput ligand-docking-based VS (Figure 1, quinuclidine 1 and indoloquinolizidine 2), and their experimental tests showed that quinuclidine 1 is more effective than indoloquinolizidine 2 in inhibition of TNF-α induced NF-κB signaling in HepG2 cells, with IC50-values of 5 and >30 μM, respectively (Chan et al., 2010). Choi and colleagues discovered a series of pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione derivatives from a 240,000-compound library. The best compound (Figure 1, Oxole-1) showed 64% inhibition at 10 μM (Choi et al., 2010). Leung et al. reported a novel iridium(III)-based direct inhibitor of TNF-α (Figure 1, [Ir(ppy)2(biq)]PF6; Leung et al., 2012). Mouhsine et al. used combined in silico/in vitro/in vivo screening approaches to identify orally available TNF-α inhibitors with IC50 of 10 μM (Figure 1, Benzenesulfonamide-1; Mouhsine et al., 2017). Other efforts to develop TNF-α inhibitors were also reported (Mancini et al., 1999; Buller et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2012; Alexiou et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2016). However, due to the low potency and high cytotoxicity, small molecule TNF-α inhibitors still have a long way to go for clinical applications (Davis and Colangelo, 2013). Highly active TNF-α inhibitors with novel chemical structures need to be developed. In a previous study, we have discovered a compound (Figure 1, EJMC-1) that directly bound TNF-α (Shen et al., 2014). The scaffold of the compound, 2-oxo-N-phenyl-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide, has been reported as inhibitors of West Nile virus (Gu et al., 2006), RORγ inhibitors (Zhang et al., 2014), and BET bromodomain inhibitors (Xue et al., 2016; Mouhsine et al., 2017). Considering the good druggability of this scaffold, its analogs may be valuable for developing potent TNF-α inhibitors. In the present study, we used the scaffold of compound EJMC-1 to perform similarity-based virtual screen and experimental testing. Top-ranking compounds were first tested for their abilities to reduce TNF-α binding with TNFR using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Then the cell-based NF-κB reporter gene assay was used to test the activities of the compounds to reduce TNF-α induced signaling. New compounds were further designed, synthesized, and tested. The structure-activity relationship of these compounds was analyzed.

HEK293T cells were received as a gift from Professor Jincai Luo (Peking University, China). The extracellular domain of the TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1-ECD) was purchased from R&D Systems. The selected compounds were purchased from the SPECS database with purity higher than 90% and for most compounds >95% (confirmed by the supplier, using NMR or LC-MS data available through the website). Other biochemistry reagents were from Sigma Aldrich unless indicated otherwise. The organic reagents and solvents were commercially available and purified according to conventional methods. All reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC), using silica gel 60 F-254 aluminum sheets and UV light (254 and 366 nm) for detection. All title compounds gave satisfactory 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectrometry analyses. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker-400 M spectrometer using TMS as internal standard. High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker Apex IV FTMS mass spectrometer using ESI (electrospray ionization).

2 was prepared based on the adoption of method by Kamal et al. (2012). Napthalic anhydride (1.98 g, 10 mmol), hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.69 mg, 10 mmol), and dry pyridine (5 ml) were added to dried three-necked flask. Heating was discontinued after reflux for 1 h, than benzenesulfonyl chloride (5 g) was added portion wise to cause controlled boiling. Finally, heating was resumed for 1 h, and the hot mixture was poured into water (30 ml). The crystalline precipitate was collected, washed with 0.5 N NaOH and water. The crystals were boiled with water (15 ml) and ethanol (5 ml) containing sodium hydroxide (5 g) for 2 h, during the second of which, ethanol was allowed to distill out. The solution was acidified with concentrated hydrochloric acid (3 ml), carbon dioxide being evolved and yellow crystals deposited. Next day, the crystals were washed, and dried to give light yellow needles (1.25 g, 74%). Mp175–179°C; 1H NMR (DMSO, 300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.05 (d, 1H, J = 6.7 Hz), 8.01 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.75–7.70 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.40 (dd, 1H, J = 7.5, 6.7 Hz), 6.94 (d, 1H, J = 6.7 Hz).

3 was prepared based on the adoption of method by Talukdar et al. (2010). Chlorosulfonic acid (3.2 ml) was added slowly to 2 (1.0 g, 5.9 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 0°C for 1 h and at room temperature for 2 h. The mixture was then poured into ice water (20 ml). The precipitate was washed with water (2 × 10 ml) and dried to give product as yellow solid (0.66 g, 38%). Used without further purification.

A mixture of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonyl chloride (100 mg, 0.37 mmol), 0.37 mmol aniline, 0.4 ml Et3N, 20 mg DMAP was dissolved in 5 ml DMF, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature, the reaction was detected by TLC, after the reaction was finished, extracted with 50 ml ethyl acetate and 20 ml water, washed with water 20 ml three times, then 20 ml saturated NH4Cl aqueous, 20 ml brine. The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by Column chromatography.

Seventy-six milligrams, yield 54%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.66 (s, 2H), 6.52 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (dd, J = 7.9, 4.0 Hz, 3H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.18 (s, 1H), 11.07 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.70, 144.73, 142.65, 132.68, 132.01, 130.51, 130.23, 129.48, 128.50, 126.64, 126.46, 125.92, 124.71, 124.56, 123.29, 122.84, 122.76, 121.03, 110.30, 107.63, 104.54. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C21H16N3O3S, [(M+H)+], 391.0912, found 390.0896.

Thirty-four milligrams, yield 26%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.20–1.29 (m, 2H), 4.67–5.36 (m, 2H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (ddd, J = 8.1, 6.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 11.12 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.10, 143.82, 142.21, 132.68, 132.21, 130.81, 130.01, 129.31, 128.65, 126.66, 126.45, 125.87, 124.63, 124.53, 123.39, 122.81, 122.77, 121.03, 110.60, 106.63, 103.59. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C21H16N3O3S, [(M+H)+], 390.0912, found 390.0896.

Sixty-eight milligrams, yield 48%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.31–1.42 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.74 (m, 2H), 2.55–2.70 (m, 2H), 4.33 (dd, J = 9.7, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.93–6.97 (m, 2H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.90–7.95 (m, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 8.35 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 11.16 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.31, 142.98, 137.57, 136.86, 132.65, 130.89, 130.37, 130.12, 129.17, 128.95, 127.41, 127.35, 126.67, 126.10, 125.31, 124.82, 105.17, 51.51, 30.68, 28.87, 19.68. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C42H36N4NaO6S2, [(2M+Na)+], 779.1974, found 799.1939.

Fifteen milligrams, yield 10%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 4.43 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.36 (m, 3H), 7.41 (ddd, J = 8.1, 6.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.72–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.85–7.90 (m, 2H), 7.98 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 11.10 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.29, 133.54, 132.94, 132.84, 131.08, 130.74, 130.04, 128.93, 128.69, 128.47, 127.29, 126.52, 126.33, 126.07, 125.47, 125.13, 124.74, 123.89, 104.98, 44.73. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C44H33N4O6S2, [(2M+H)+], 777.1842, found 777.1804.

Ninety-one milligrams, yield 68%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 6.21–6.27 (m, 1H), 6.67 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 10.20 (s, 1H), 10.91 (s, 1H), 11.11 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.15, 143.24, 136.18, 133.83, 131.41, 130.96, 129.77, 128.07, 127.28, 126.38, 125.87, 125.29, 124.90, 120.64, 114.44, 105.02, 104.61, 101.32. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C38H27N6O6S2, [(2M+H)+], 727.1433, found 727.1428.

Seventy-six milligrams, yield 51%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 3.84 (s, 3H), 6.80 (dt, J = 5.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.09 – 7.13 (m, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.90 – 7.95 (m, 1H), 7.98 (s, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 10.59 (s, 1H), 11.16 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.25, 143.33, 136.18, 133.83, 133.56, 131.41, 130.96, 130.51, 129.77, 128.07, 127.28, 126.38, 125.87, 125.29, 124.90, 124.64, 119.44, 117.82, 117.61, 114.32, 40.51. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C21H17N4O3S, [(M+H)+], 405.1021, found 405.1086.

Eighty milligrams, yield 62%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.37-7.31 (m, 2H), 7.69–7.75 (m, 1H), 7.82 (dt, J = 8.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.93–8.03 (m, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.19 (s, 1H), 11.35 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.46, 145.77, 143.47, 142.38, 136.22, 132.11, 129.83, 127.72, 127.05, 126.04, 125.57, 125.46, 124.71, 123.50, 122.77, 120.65, 112.18, 104.85. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C36H23N6O6S2, [(2M+H)+], 699.1120, found 699.1135.

Binding interactions between TNF-α and TNFR1-ECD in the presence/absence of small molecule inhibitors were examined on the SPR-based Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare). TNFR1-ECD was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip using standard amine-coupling at 25°C with 1X running buffer PBS-P (GE Healthcare). A reference flow cell was activated and blocked in the absence of TNFR1-ECD. All experiments were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-EP buffer (10 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 150 mM NaCl, 3.7 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) at 25°C with a flow rate of 50 μl/min. A final concentration of 20 nM TNF-α was mixed with each compound at various concentrations (as indicated in section Results) in PBS-EP and the mixture was injected. Equal amounts of TNF-α mixed with PBS-EP were used as a control. Regeneration was achieved by extended washing with glycine hydrochloride buffer (10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.1) after each sample injection.

The cellular assay were carried out as described previously (Zhang et al., 2013). HEK293T cells were grown to 70% confluence in 6 cm dish at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), then transfected with purified plasmids 0.6 μg pGL4.32 (luc2P/NF-κB-RE/Hygro plasmid) and 0.4 μg pGL4.74 (hRluc/TK) with ViaFect transfection reagent (Promega). After 24 h, the transfected cells were seeded in 96-wells plate, 40,000 cells per well. Twelve hours later, 100 μL pre-incubated mixture of TNF-α and small molecules was added to stimulate the cells for 6 h and the luciferase assays were carried out using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) with a BioTek synergy 4 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. The final concentration of TNF-α in each well was 10 ng/ml. Equal amounts of TNF-α without small molecular were added to the cells as a negative control to calculate the percentage of activity inhibition.

The crystal structure of TNF-α dimer (PDB code: 2AZ5) was used for grid generation. The program Glide Standard Precise (SP) mode was used to do the molecular docking studies (Friesner et al., 2004; Halgren et al., 2004). EJMC-1 was first docked to TNF-α dimer, and its conformation in the complex was used for Shape Screening of the SPECS library (May 2013 version for 10 mg; 197,276 compounds). The Shape Similarity indexes between each compound in the library and the reference compound were calculated. A total of 587 compounds with indexes between 0.8 and 0.99 were selected as candidates for the second round manual selection with the following selection criteria: (a) containing at least one ring which provides hydrophobic interaction; (b) containing no metal atoms; and (c) shared in multiple structures. A total of 68 compounds were purchased from SPECS for experimental testing.

The complex structure of TNF-α with SPD304 (PDB code: 2AZ5) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank and docking was performed with maestro (Schrödinger, Inc., version 10.2). Compound EJMC-1, S10, and 4e were docked into TNF-α dimer protein using Glide Docking module (Friesner et al., 2004; Halgren et al., 2004). The details of the docking workflow are listed below: (1) Protein was prepared using the “Protein Preparation Wizard” workflow. All water molecules were removed from the structure of the complex. Hydrogen atoms and charges were added during a brief relaxation. After optimizing the hydrogen bond network, the crystal structure was minimized using the OPLS_2005 force field with the maximum root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.3 Å. (2) The ligand was prepared with LigPrep module in Maestro, including adding hydrogen atoms, ionizing at a pH range from 7.2 to 7.4, and producing the corresponding low-energy 3D structure. (3) Pose prediction mode of Glide Docking modules were adopted to dock the molecules into the SPD304-binding site with the default parameters. The center of the grid box was defined with SPD304. The top-ranking poses of molecule EJMC-1, S10, and 4e were retained. The LigPrep mol2 format output was also docked using AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010) with standard protocols. The computed binding free energies and structures for the top conformations were saved for post-docking analysis.

Cell assay was repeated for three times. Statistical analysis was performed using OriginPro 9.1, data was fit by DoseResp using Origin 9.1. DoseResp was a three-parameter Hill equation. Results were expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation value).

Seven derivatives of dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide were synthesized using a three-step synthetic route (Scheme 1) with yields between 10 and 68%. Napthalic anhydride was transformed to benzo[cd]indol-2(1H)-one by aminolysis reaction smoothly, with a yield of 74%. Then, benzo[cd]indol-2(1H)-one underwent nucleophile substitution reaction with chlorosulfonic acid to get key intermediate 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonyl chloride (3), with a yield of 38%. Reactions of compound 3 with various amines in the presence of a catalyst system consisting of DMAP, Et3N, afforded 4 and derivatives in good yields. The original spectra of featured compounds shown in Supplementary Image 1.

We used compound EJMC-1 as the reference compound for similarity search (Figure 1). The binding conformation of EJMC-1 with TNF-α was generated using molecular docking and used in pharmacophore based shape screening over the SPECS library. Compounds with similarity index between 0.80 and 0.99 with EJMC-1 were subjected to further manual selection. A total of 68 compounds were selected for experimental testing (Table S1). The chemical structures of these compounds fall into two classes, sulfonates and sulfonamides. The sulfonamides contain both N-aryl sulfonamides and N-alkylsulfonamides, with or without substituted aminocarbonyl group (Table S1).

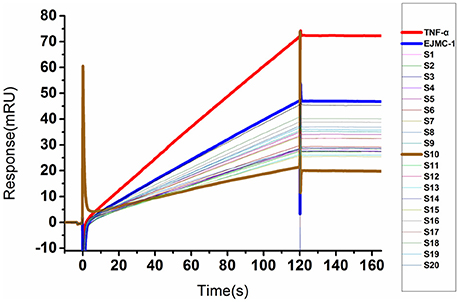

We used a SPR competitive assay to test whether these compounds can more efficiently block TNF-α and TNFR binding than EJMC-1. TNF-α with or without compounds flowed over the chip surface where the extracellular domain of TNFR was immobilized. At the concentration of 100 μM, 20 of the 68 compounds reduced the TNF-α binding signal compared to EJMC-1 (Figure 2). These 20 candidates were selected for further cell-based inhibition studies. The specs ID of these 20 compounds were listed in Table S2, and the corresponding chemical structures were in supporting information. All the sulfonamide derivatives of EJMC-1 showed competitive binding with TNF-α against TNFR1, while sulfonates could not.

Figure 2. SPR competitive binding curves of compounds from shape screening of EJMC-1. Compounds showed competitive binding to TNF-α. The Red curve was TNF-α binding with TNFR1-ECD alone, and the other curves were TNF-α TNFR1-ECD in the presence of compounds at 100 μM. The reference compound EJMC-1 was colored blue and the best compound in SPR assay S10 was colored brown.

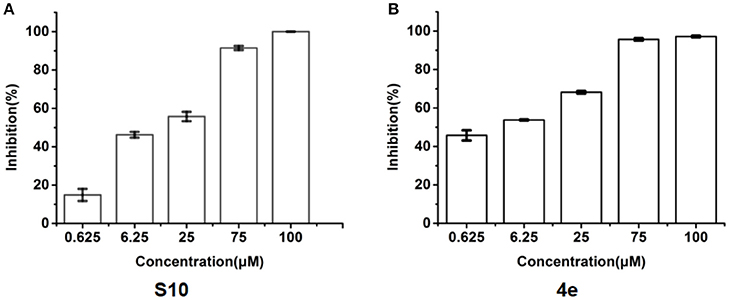

To explore whether these compounds with enhanced abilities to reduce TNF-α binding with receptor were active under cellular environment, we used a luciferase assay to monitor their influences on NF-κB transcriptional activity. In this assay, in transfected cells, TNF-α induces NF-κB activation through TNFR1, which then drives the expression of the luciferase. The cell-level inhibitory effects of these 20 compounds were measured using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System. With two dose screen, two compounds, S3 and S10 showed better activity than EJMC-1 (Table S2). The best compound, S10, suppressed NF-κB transcriptional activity dose-dependently (Figure 3A) with an IC50 of 19.1 ± 2.2 μM. The positive control, SPD304, displayed an IC50 of 6.4 ± 0.6 μM in the side-by-side experiment.

Figure 3. Inhibition of TNF-α induced NF-κB transcription activity. (A) Dose-response of compounds S10 in the cell based assay in 293T cell line. (B) Dose-response of compounds 4e in the cell based assay in 293T cell line. The data was reported as means ± errors from three independent experiments.

Molecular docking gave clues on rational designing compounds with potential enhanced activities and understanding SAR. In the complex structure of TNF-α with SPD304, SPD304 bound to a pocket in the TNF-α dimer (He et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2014). EJMC-1 was shown to bind with the same site (He et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2014). Both Glide and AutoDock Vina were used in the docking study. We first tested whether the binding pose of SPD304 can be reproduced. We have tried many times with different parameters, but was unable to get a binding pose that is close to that in the crystal structure (with the minimum RMSD up to 4 Å). We then used AutoDock Vina to dock SPD 304 to the TNF-α dimer and the lowest binding free energy conformation obtained was closed to its crystal conformation with a RMSD of 0.70 Å. Despite of the different binding conformations obtained for SPD304 by using two docking software, the top ranking conformations of EJMC-1 were almost the same from the docking runs using both Glide and AutoDock Vina. These differences might due to the flexibility of SPD304, which adopted a U shape conformation, and the conformational sampling preference of the docking software. As there are no essential differences in the docking poses of the compounds other than SPD304, we used the Glide docking poses of these compounds to compare to SPD304 in the crystal structure. Compared to EJMC-1, S10 had increased hydrophobic interaction with the Tyr59 residue (Figures 4A,B). In addition to the nonpolar interactions with TNF-α as in the case of SPD304, the scaffold of EJMC-1 and S10 provide further polar interactions, strengthening the specificity and activity (Figure 4C). As EJMC-1 is smaller than that of SPD304 with unoccupied hydrophobic space in the pocket (Figure 4C), several analogs with larger substituted group of sulfonamide of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide were designed and docked to this site. Compound 4e, with larger hydrophobic group size and additional H-bond donor, interacts favorably with TNF-α and might be more potent (Figure 4D). Based on the docking analysis, the designed analogs were purchased or synthesized for cell assay.

Figure 4. The predicted binding modes of TNF-α inhibitors. Predicted binding mode of compounds EJMC-1 and 4e to TNF-α. The binding site was shown as surface, the key residues were shown as sticks (green). (A) compound EJMC-1 (yellow). (B) Compound S10 (cyan). (C) EJMC-1 compare to SPD304 (gray). (D) compound 4e (magenta).

As shown in the cell assay, the inhibition activity of S10 increased about 2-fold than that of EJMC-1. The introduction of the naphthalene ring provides stronger hydrophobic interactions. Based on the docking analysis and increased activity of S10, we try to: (1) Keep naphthalene ring, changed N-substituted groups of dihydrobenzo[cd]indole, (2) Keep N-H of dihydrobenzo[cd]indole, optimize the hydrophobic R group, (3) optimize both N-substituted groups of dihydrobenzo[cd]indole and the hydrophobic R group (Figure 5). Seven commercially available analogs of S10 were purchased for testing (Table 1). The SPECS ID of these seven S10 analogues were listed in Table S3. We further synthesized seven new compounds in three steps from 1,8-Naphthalic anhydride through conventional reactions (Scheme 1 and Figure 5). All compounds passed the PAINS (pan assay interference compounds) remover, which filters out compounds that appear as frequent hitters (promiscuous compounds) in many biochemical high throughput screens (Baell and Holloway, 2010).

All the compounds were tested using the TNF-α induced NF-κB reporter assay. The structures and activities were listed in Table 1. For S10, methyl or ethyl group substitution on the amide of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide had no obviously enhanced inhibition (S21 and S22), and the α or β substitution of the naphthyl group did not affect the inhibition (S23, S24, and S25). The size of the N-substituted groups of sulfonamide was important for inhibition activity (EJMC-1, S10, and S27). The flexibility and aromaticity of the N-substituted two-ring group of sulfonamide played dominant role, too rigid or too flexible dramatically reduced the activity (4g, 4d). The fact that N-(5-aminonaphthalen-1-yl) and N-(3-aminonaphthalen-1-yl) group substituted compounds lost functions might be caused by the conformation change due to additional amino group on the naphthalene ring. Introducing heterocycle significantly increases the inhibition activity (4e and 4f). The N-(1H-indol-6-yl) substituted sulfonamides (4e) were 6-fold more potent than S10, even better than SPD304 (Table 1, Figure 3B). Though S10 and 4e had similar size of substitution group on sulfonamide, 4e shown better inhibition activity than S10 might due to the additional H-bond that 4e forms with the backbone carbonyl of Gly121 (Figure 4C). Meanwhile, the indolyl group of 4e was also deeper in the binding pocket than that of naphthyl group on S10 (Figure 4D).

We have optimized a previously reported TNF-α inhibitor EJMC-1 using similarity-based VS and rational design. An analog of EJMC-1, S10 was found with 2-fold TNF-α increased inhibition activity. Based on the structures of EJMC-1, S10, and their interactions with TNF-α, we designed derivatives of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide. Several commercially available ones were purchased and seven new compounds were synthesized for SAR study. After two rounds of design, we obtained 4e with an IC50 of 3.0 ± 0.8 μM, which is one of the most potent TNF-α small molecule inhibitors reported so far. Compound 4e provides a good starting point for developing more potent TNF-α small molecule inhibitors.

LL and YL designed and guided this study; XD designed the research, performed molecular docking and similarity search, and conducted the chemical synthesis; XZ performed the cell assay; HL and QS participated in the cell assay; BT performed the SPR binding assay; XD, LL, and YL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors; XD and XZ have equal contribution of this work.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFA0502303, 2015CB910300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21633001, 21573012).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2018.00098/full#supplementary-material

Ai, J. W., Zhang, S., Ruan, Q. L., Yu, Y. Q., Zhang, B. Y., Liu, Q. H., et al. (2015). The risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist: a metaanalysis of both randomized controlled trials and registry/cohort studies. J. Rheumatol. 42, 2229–2237. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150057

Alexiou, P., Papakyriakou, A., Ntougkos, E., Papaneophytou, C. P., Liepouri, F., Mettou, A., et al. (2014). Rationally designed less toxic SPD-304 analogs and preliminary evaluation of their TNF inhibitory effects. Arch. Pharm. 347, 798–805. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201400198

Alzani, R., Corti, A., Grazioli, L., Cozzi, E., Ghezzi, P., and Marcucci, F. (1993). Suramin induces deoligomerization of human tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 12526–12529.

Baell, J. B., and Holloway, G. A. (2010). New substructure filters for removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j

Bongartz, T., Matteson, E. L., and Orenstein, R. (2005). Tumor necrosis factor antagonists and infections: the small print on the price tag. Arth. Rheum. 53, 631–635. doi: 10.1002/art.21471

Buller, F., Zhang, Y. X., Scheuermann, J., Schäfer, J., Bühlmann, P., and Neri, D. (2009). Discovery of TNF inhibitors from a DNA-encoded chemical library based on diels-alder cycloaddition. Chem. Biol. 16, 1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.09.011

Chan, D. S., Lee, H. M., Yang, F., Che, C. M., Wong, C. C., Abagyan, R., et al. (2010). Structure-based discovery of natural-product-like TNF-α inhibitors. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 2860–2864. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907360

Choi, H., Lee, Y., Park, H., and Oh, D. S. (2010). Discovery of the inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor alpha with structure-based virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 6195–6198. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.116

Davis, J. M., and Colangelo, J. (2013). Small-molecule inhibitors of the interaction between TNF and TNFR. Future Med. Chem. 5, 69–79. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.192

Friesner, R. A., Banks, J. L., Murphy, R. B., Halgren, T. A., Klicic, J. J., Mainz, D. T., et al. (2004). Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 47, 1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430

Grazioli, L., Alzani, R., Ciomei, M., Mariani, M., Restivo, A., Cozzi, E., et al. (1992). Inhibitory effect of suramin on receptor binding and cytotoxic activity of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 14, 637–642. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90125-5

Gu, B. H., Ouzunov, S., Wang, L. G., Mason, P., Bourne, N., Cuconati, A., et al. (2006). Discovery of small molecule inhibitors of West Nile virus using a high-throughput sub-genomic replicon screen. Antiviral Res. 70, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.01.005

Halgren, T. A., Murphy, R. B., Friesner, R. A., Beard, H. S., Frye, L. L., Pollard, W. T., et al. (2004). Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem. 47, 1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s

He, M. M., Smith, A. S., Oslob, J. D., Flanagan, W. M., Braisted, A. C., Whitty, A., et al. (2005). Small-molecule inhibition of TNF-α. Science 310, 1022–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1116304

Hu, Z., Qin, J., Zhang, H., Wang, D., Hua, Y., Ding, J., et al. (2012). Japonicone A antagonizes the activity of TNF-α by directly targeting this cytokine and selectively disrupting its interaction with TNF receptor-1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84, 1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.08.025

Jacobi, A., Mahler, V., Schuler, G., and Hertl, M. (2006). Treatment of inflammatory dermatoses by tumour necrosis factor antagonists. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 20, 1171–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01733.x

Kamal, A., Ramakrishna, G., Lakshma Nayak, V., Raju, P., Subba Rao, A. V., Viswanath, A., et al. (2012). Design and synthesis of benzo[c,d]indolone-pyrrolobenzodiazepine conjugates as potential anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.003

Kang, T. S., Mao, Z., Ng, C. T., Wang, M., Wang, W., Wang, C., et al. (2016). Identification of an iridium(III)-based inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4026–4031. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00112

Leung, C. H., Chan, D. S. H., Kwan, M. H. T., Cheng, Z., Wong, C. Y., Zhu, G. Y., et al. (2011). Structure-based repurposing of FDA-approved drugs as TNF-α inhibitors. ChemMedChem 6, 765–768. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100016

Leung, C. H., Zhong, H. J., Yang, H., Cheng, Z., Chan, D. S., Ma, V. P., et al. (2012). A metal-based inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-α. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 9010–9014. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202937

Lian, W. L., Upadhyaya, P., Rhodes, C. A., Liu, Y. S., and Pei, D. H. (2013). Screening bicyclic peptide libraries for protein-protein interaction inhibitors: discovery of a tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11990–11995. doi: 10.1021/ja405106u

Ma, L., Gong, H., Zhu, H., Ji, Q., Su, P., Liu, P., et al. (2014). A novel small-molecule tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor attenuates inflammation in a hepatitis mouse model. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 12457–12466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521708

Mancini, F., Toro, C. M., Mabilia, M., Giannangeli, M., Pinza, M., and Milanese, C. (1999). Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha)/TNF-alpha receptor binding by structural analogues of suramin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58, 851–859. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00150-1

Mouhsine, H., Guillemain, H., Moreau, G., Fourati, N., Zerrouki, C., Baron, B., et al. (2017). Identification of an in vivo orally active dual-binding protein-protein interaction inhibitor targeting TNFα through combined in silico/in vitro/in vivo screening. Sci. Rep. 7:3424. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03427-z

Scheinfeld, N. (2004). A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 15, 280–294. doi: 10.1080/09546630410017275

Shen, Q., Chen, J., Wang, Q., Deng, X., Liu, Y., and Lai, L. (2014). Discovery of highly potent TNFalpha inhibitors using virtual screen. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 85, 119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.091

Sun, H., and Yost, G. S. (2008). Metabolic activation of a novel 3-substituted indole-containing TNF-alpha inhibitor: dehydrogenation and inactivation of CYP3A4. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 374–385. doi: 10.1021/tx700294g

Talukdar, A., Morgunova, E., Duan, J., Meining, W., Foloppe, N., Nilsson, L., et al. (2010). Virtual screening, selection and development of a benzindolone structural scaffold for inhibition of lumazine synthase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 3518–3534. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.072

Trott, O., and Olson, A. J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334

Wajant, H., Pfizenmaier, K., and Scheurich, P. (2003). Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401189

Xue, X. Q., Zhang, Y., Liu, Z. X., Song, M., Xing, Y. L., Xiang, Q. P., et al. (2016). Discovery of benzo[cd]indol-2(1H)-ones as potent and specific BET bromodomain inhibitors: structure-based virtual screening, optimization, and biological evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 59, 1565–1579. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01511

Zhang, C. S., Shen, Q., Tang, B., and Lai, L. H. (2013). Computational design of helical peptides targeting TNFα. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 11059–11062. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305963

Zhang, Y., Xue, X., Jin, X., Song, Y., Li, J., Luo, X., et al. (2014). Discovery of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide derivatives as new RORγ inhibitors using virtual screening, synthesis and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 78, 431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.065

Keywords: TNF-α inhibitor, dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide, virtual screening, synthesis, structure activity analysis

Citation: Deng X, Zhang X, Tang B, Liu H, Shen Q, Liu Y and Lai L (2018) Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Dihydrobenzo[cd]indole-6-sulfonamide as TNF-α Inhibitors. Front. Chem. 6:98. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00098

Received: 10 January 2018; Accepted: 20 March 2018;

Published: 04 April 2018.

Edited by:

Daniela Schuster, Paracelsus Medizinische Privatuniversität, AustriaReviewed by:

Hyun Lee, University of Illinois at Chicago, United StatesCopyright © 2018 Deng, Zhang, Tang, Liu, Shen, Liu and Lai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Liu, bGl1eWluZ0Bwa3UuZWR1LmNu

Luhua Lai, bGhsYWlAcGt1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.