94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem., 30 October 2017

Sec. Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Volume 5 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2017.00085

This study was carried out to isolate chemical constituents from the lipid enriched fraction of Ganoderma lucidum extract and to evaluate their anti-proliferative effect on tumor cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Ergosterol derivatives (1–14) were isolated and purified from the lipid enriched fraction of G. lucidum. Their chemical structures were established by spectroscopic analyses or by comparison of mass and NMR spectral data with those reported previously. Amongst, compound 1 was purified and identified as a new one. All the compounds were evaluated for their anti-proliferative effect on human tumor cells and HUVECs in vitro. Compounds 9–13 displayed inhibitory activity against two types of human tumor cells and HUVECs, which indicated that these four compounds had both anti-tumor and anti-angiogenesis activities. Compound 2 had significant selective inhibition against two tumor cell lines, while 3 exhibited selective inhibition against HUVECs. The structure–activity relationships for inhibiting human HepG2 cells were revealed by 3D-QASR. Ergosterol content in different parts of the raw material and products of G. lucidum was quantified. This study provides a basis for further development and utilization of ergosterol derivatives as natural nutraceuticals and functional food ingredients, or as source of new potential antitumor or anti-angiogenesis chemotherapy agent.

Tumor, characterized by abnormal cell proliferation and metastasis, is one of the most attracted chronic diseases and remains the leading cause of death worldwide. Tumor development is accompanied by tumor angiogenesis. Angiogenesis plays a key role in tumor formation, growth, invasion, and metastasis. Inhibiting the angiogenesis of tumors can not only cut off the supply of nutrients such as, oxygen and nutrients needed for tumor growth, but also cut the way of tumor cell metastasis (Folkman, 1971; Papetti and Herman, 2002; McDougall et al., 2006; Berz and Wanebo, 2011). Therefore, inhibitors of tumor angiogenesis are considered to be an effective strategy for the treatment of cancer.

Back-to-nature has become a chasing idea in recent decades. Edible or medicinal fungi have attracted more and more attention due to their extensive pharmacological effect for chronic diseases (Loria-Kohen et al., 2014), especially for preventing or complementary treating cancer. As one of the most famous medicinal fungi, Ganoderma lucidum (Ganodermataceae), firstly recorded in Shen Nong's Herbal Classic, was believed by the ancient people to promote longevity and even revive the dead with beautiful legends. The mystery of G. lucidum aroused widespread interest of researchers in modern times. G. lucidum was demonstrated to possess activities including anti-cancer (Sliva, 2006; Rios et al., 2012; Boh, 2013; Gill et al., 2016), antidiabetic (Chang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2015), hepatoprotective (Ha do et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016), antiviral (especially anti-HIV activities; Min et al., 1998), and immunomodulating (Wang et al., 2014a,b). The anti-cancer of G. lucidum research is very popular in recent decades. It's believed that triterpenoids and polysaccharide are responsible for the anti-cancer effect. Besides, steroids and other kinds of compounds were also found in G. lucidum.

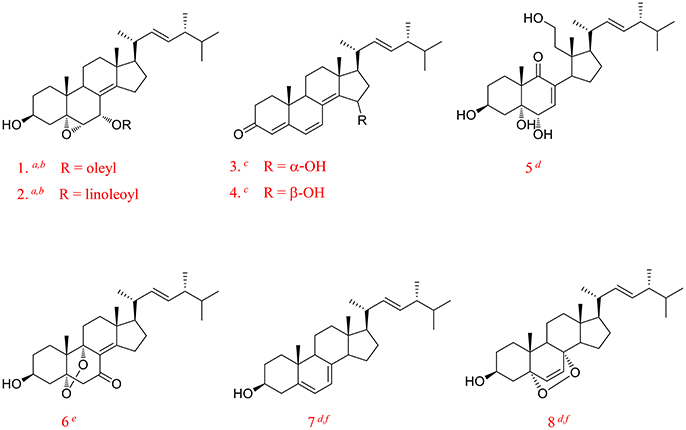

In recent years, we began to search bioactive secondary metabolites from edible and medicinal fungi and to study their mechanisms on chronic diseases. We had reported ergosterol peroxide from G. lucidum and ergosterol isolated from Amauroderma rude inhibiting cancer growth by up-regulating multiple tumor suppressors (Li et al., 2015, 2016). Steroids were a class of rich and important ingredients in edible and medicinal fungi since they play a pivotal role in maintaining normal structure and function of cell membranes and also act as precursors for the synthesis of metabolites like steroid hormones (Weete and Laseter, 1974; Mille-Lindblom et al., 2004; de Macedo-Silva et al., 2015). Sterols are reported to demonstrate immune-modulating (Bouic, 2002), anti-tumor (Yasukawa et al., 1994; Loza-Mejia and Salazar, 2015; Montserrat-de la Paz et al., 2015; Kiem et al., 2017), anti-inflammatory (Yasukawa et al., 1994; Kuo et al., 2011; Joy et al., 2017), anti-oxidative (Zhang et al., 2002), and other pharmacological activities (Kim and Ta, 2011; Zhu et al., 2014). Figure 1 showed some of the biologically active ergosterol derivatives reported from common edible fungi (Fan et al., 2006; Weng et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011; Zhao, 2013; Li et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Kikuchi et al., 2016). As ergosterol derivatives were multi-active and rich in fungi, they must be brought into focus during fungi research and development. However, current understanding of ergosterols composition in fungi is still not enough, especially on pharmacological mechanisms and structure-activity relationship.

Figure 1. Some of the biologically active ergosterol derivatives from common edible mushrooms from literature. (1, Erinarol A; 2, Erinarol B; 3, Ganodermaside A; 4, Ganodermaside B; 5, (22E)-3β, 5α, 6α, 11-tetrahydroxy-9(11)-seco-ergosta-7, 22-dien-9-one; 6, Gargalols B; 7, Ergosterol; 8, Ergosterol peroxide; a PPAR transactivational effect; b Cytotoxicity; c Anti-aging; d Anti-inflammatory; e Suppressing osteoclast-forming; f Anti-cancer).

In order to enrich the understanding of the diversity of ergosterols and to find more bioactive or higher active ergosterol derivatives, we carried out current work on G. lucidum. We now isolated 14 ergosterol derivatives, including one new compound, all of which showed anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic activities in vitro in different levels. Herein, we described the structural elucidation and activity assay of these compounds. Their structure–activity relationships of cytotoxicity were also discussed. Besides that, the content of ergosterol in different parts of raw material and preparation of G. lucidum was also quantified.

Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 with an Agilent DAD spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) and a YMC-Pack Pro C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, YMC Ltd., Japan). Preparative HPLC was performed on a Shimadzu LC-20A spectrophotometer and a YMC-Pack Pro C18 column (5 μm, 20 × 250 mm). NMR (1D and 2D) spectra were recorded by a Bruker AVANCE III 600 spectrometer. The ESI-MS spectra were measured on a 6430 Triple Quad mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The HR-ESI-MS spectra were recorded using a Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). UV and IR data were measured using a JASCO V-550 UV/vis and a JASCO FT/IR-480 plus spectrometers (Jasco, Japan), respectively. Normal phase silica-gel (200–300 mesh) was purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Octadecylsilanized silica (ODS) gel (50 μm) was purchased from YMC Ltd. in Japan. The optical density was measured on a Tecan Infinite®200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan, Swiss).

The fruiting bodies of G. lucidum had the same origination as that in our last published paper (Chen et al., 2017). They were all provided by Yuewei Edible Fungi Technology Co. Ltd., Guangzhou, China, and they originated from Dabie Mountain, Anhui, China. The voucher specimen (No. GL20160117) was deposited in State Key Laboratory of Applied Microbiology Southern China, Guangdong Institute of Microbiology.

The extraction and isolation procedure was similar to that of our last published paper (Chen et al., 2017). The dried fruiting bodies of G. lucidum (5.0 kg) were powdered and extracted with 95% ethanol (100 L × 2, liquid ratio 20:1) by heating-reflux to give a black crude extract (marked as GL, 116.2 g). As the extract was well dissolved in methanol-chloroform mixture, GL (100 g) was dissolved with methanol-chloroform (1:1) and mixed with silica gel. After solvent evaporating, the sample was added to an open ODS silica gel column and eluted with 35, 50, 75, and 100% methanol in sequence to give four fractions (marked as GL-1 to GL-4). GL-4 exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects on human tumor cells. Accordingly, GL-4 was selected for further isolation. Fraction GL-4 was subjected to an open silica-gel column chromatography eluted with cyclohexane-ethyl acetate-methanol (90:10:0, 80:20:0, 70:30:0, 50:50:0, 30:70:0.5, 0:100:1, 0:0:100) successively to afford 7 fractions marked as Fr. 4.1–Fr. 4.7. As the polarity of constituents in Frs. 4.5 and 4.6 were suitable for further isolation and purification based on TLC and HPLC analysis, Frs. 4.5 and 4.6 had been chosen for the subsequent isolation. Fr. 4.5 was further chose to purified on an ODS silica gel column and eluted with MeOH–H2O (50:50, 70:30, 80:20, 90:10, and 100:0) to produce 5 subfractions (Fr. 4.5.1–Fr. 4.5.5). Constituents in Frs. 4.5.4 and 4.5.3 had good peaks shape and resolution factor by HPLC analysis. Fr. 4.5.4 was purified on preparative HPLC eluted by 85% MeOH to afford compounds 2, 3, 4, 5, and 1. Fr. 4.5.3 was further purified on prep-HPLC by 70% MeOH to give compounds 6, 7, and 8. Fr. 4.6 was further subjected to a ODS column eluted with MeOH–H2O (50:50, 70:30, 80:20, 90:10, and 100:0) to afford five subfractions (Fr. 4.6.1–Fr. 4.6.5). Compound 12 was isolated from Fr. 4.6.5 by recrystallization. Similarly, Fr. 4.6.4 was suitable for further isolation. Fr. 4.6.4 was purified by preparative HPLC (MeOH–H2O, 90:10) to afford compounds 9, 10, 11, and 13. Compound 14 was isolated from Fr. 4.6.3 by prep-HPLC with 80% MeOH elution.

Human breast carcinoma cells MDA-MB-231, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2, and human lung carcinoma cells A549, were purchased from ATCC, or were gifted by Professor Burton B. Yang from University of Toronto, Canada. The anti-proliferative effect of total extract (GL), fractions (GL1–GL4), and compounds 1–14 on tumor cell lines was evaluated by MTT assay (Franchi et al., 2012). Total extract (GL) and fractions (GL1–GL4) were evaluated for their anti-proliferative effect on three types of carcinoma cells (MDA-MB-231, HepG2, and A549). Compounds 1–14 were chosen to evaluate for their anti-proliferative effect against MDA-MB-231 and HepG2 cells. Hundred microliters of cells suspension (5 × 104 cells/mL) was seeded into wells of a 96-well plate. After being incubated for 4 h, different concentrations of fractions/compounds were added onto the cells and incubated. After 48 h, 150 μL of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (Sigma) was added to each well, and cells were kept being incubated for 4 h. After removing the MTT/medium, DMSO (100 μL) of was added to each well and was agitated at 60 rpm for 5 min. The optical density of the assay 96-well plate was read (λ = 540 nm) on a microplate reader.

HUVECs (KeyGEN BioTECH Co., Ltd, Jiangsu, China) were cultured in ECM (endothelial cell medium) with 5% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) ECGS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (w/v) at 37°C in a cell incubator. The MTT assay was employed to assess the anti-angiogenic effect of the isolated compounds against HUVECs as described previously with mild modification (Liang et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2015). Briefly, HUVECs were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated. Different concentrations of compounds 1–14 were added onto the cells after 4 h, and continued to be co-incubated for 48 h. Next, the cells were co-incubated with MTT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to a final concentration of 0.05% for another 4 h. Then, replacing the MTT solution with 150 mL DMSO, and kept the plates being shaken for 3 min. The optical density of each well was measured on a microplate reader at λ = 570 nm.

IC50-values were calculated and analyzed using SPSS with three replications, each carried out in triplicate. Data were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by two-tailed Student's t-test. A difference was considered significant at the P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 level.

From the compounds, 15 compounds with accurate IC50s were chosen for 3D QSAR model establishment with Discovery Studio 3.1 (Luo et al., 2014; Sang et al., 2014). Firstly, the selected compounds were randomized into trainging set for model generation and test set for model validation, where training set divided 80% ratio. The remaining 20% (three compounds) for test set were compound 8, 14, and kaempferol. Then, the observed IC50s (μM) were converted to pIC50s, which were used as response variables. In model generation, force field was selected as CHARMm. Electrostatic potential were described by probing with a + 1e point charge and solvation were mimicked with distance dependent dielectric constant. Van der Waals potential was depicted by probing with a carbon atom of 1.73 Å in radius. The cut-off for electrostatic and steric energies was 30 kcal/mol. Others were kept as default.

Analyses were performed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC instrument, equipped with a G1311A pump and a G1314A UV detector. The chromatographic separation was achieved on an Agilent prep-C18 analytical column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Agilent) eluted with 95% methanol at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, maintained at 35°C. The choice UV detection wavelength was 282 nm. All injection volumes were 20 μL.

Ergosterol was accurately weighed and dissolved in methanol at 2.00 μg/mL. The stock solution was stored at 4°C protected against bright light.

To 1.00 g of the powdered raw material of G. lucidum add 50.0 mL 95% ethanol. Weigh and heat under a reflux condenser for 1 h. Allow to cool. Make up the weight loss with the same solvent, mix well, and filter. Transfer the solution into a 50.0 mL volumetric flask and bring to volume with methanol. To 0.40 g of the spore oil or the spore extract of G. lucidum transfer to a 10.0 mL volumetric flask, add 95% ethanol to the scale line and mix well. All the test solution was filtered respectively through a 0.45 μm membrane prior to an injection into HPLC system. Carry out the assay protected against bright light.

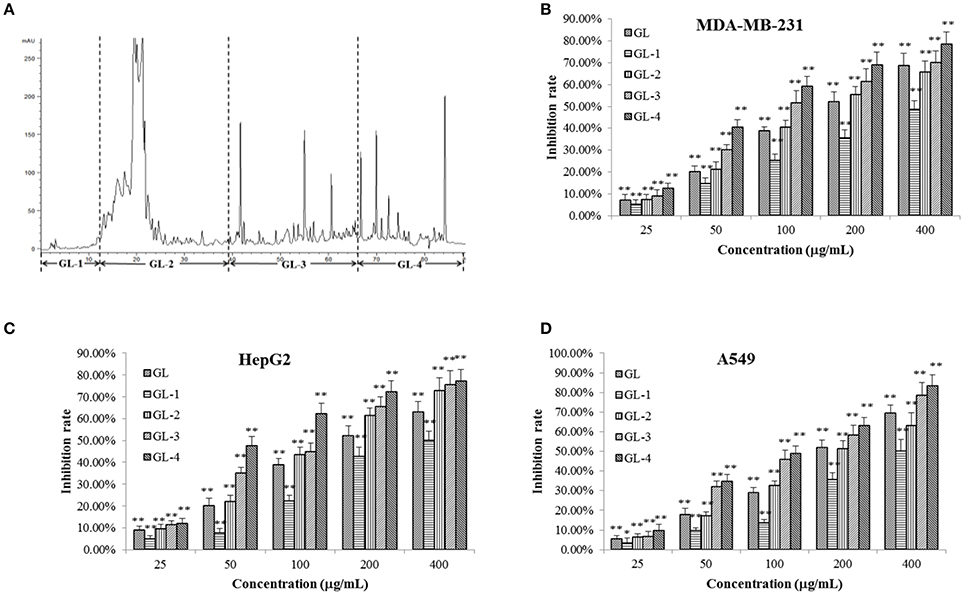

In brief, the dried fruiting bodies of G. lucidum were powdered and extracted with 95% ethanol by heating-reflux to give a black crude extract (marked as GL). GL was dissolved with methanol-chloroform and mixed with silica gel. After solvent evaporating, the sample was loaded to an open ODS silica-gel column chromatograph eluted by gradient 30, 50, 75, and 100% methanol in sequence to give four fractions, which were marked as: water soluble fraction (marked as GL-1, 25.8 g), ganoderic acid enriched fraction (GL-2, 19.1 g), ganoderol enriched fraction (GL-3, 6.5 g), and lipids enriched fraction (GL-4, 34.8 g). Figure 2A showed the constituents complexity of GL-1–GL-4 by HPLC analysis at λ 254 nm.

Figure 2. Chromatrogram of the GL extract (A) at 254 nm and anti-proliferative effects of its fractions against MDA-MB-231 (B), HepG2 (C), and A549 (D) cells. The asterisms indicate that the values were significantly different from the controls (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

An MTT assay was employed to assess the inhibitory effects of GL samples on MDA-MB-231, HepG2, and A549 cells (Figures 2B–D). It was observed that GL samples (p < 0.05) inhibited the proliferation of three tumor cell lines compared to the blank control. For all the three tumor cells, within the concentration of 25–400 μg/mL, all samples inhibited the proliferation of three types of human cancer cells concentration-dependently. All samples possessed similar capability to inhibit the growth of MDA-MB-231, HepG2, and A549 cells. Significant reductions (p < 0.01) in cell viabilities were observed under the interference of GL, GL-2, GL-3, and GL-4 fractions except GL-1. This suggested that the active constituents may concentrate in the GL2, GL3, and GL4 fractions. GF-4 fraction displayed a much higher inhibition rate (p < 0.01) than GF. Besides, GF-4 also showed higher inhibition rate (p < 0.05) than GL-2 and GL-3, indicating GL-4 were the best bioactive fraction. Since the total triterpenoids fraction (GL-2 and GL-3) has been studied in our previous research (Chen et al., 2017), as well as the lipids enriched fraction (GL-4) showed higher inhibitory effects on tumor cells than other fractions. Therefore, GL-4 was selected for further research in this paper.

Bioassay-guided fraction (GL-4) of G. lucidum extract (GL) led to 14 ergostane-type sterols. Their chemical structures were established based on comprehensive spectroscopic analyses or comparison of mass and NMR spectroscopic data with those literatures reported.

Compound 1 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. Its molecular formula of C29H46O3 was determined based on the HR-ESI-MS m/z 443.3505 [M + H]+ (calcd for C29H47O3, 443.3525), indicating the presence of seven degrees of unsaturation in the molecule. A strong absorption (λmax) at 245 nm in UV spectrum declaring a conjugated diene system existed in the chemical structure. The 13C NMR together with DEPT-135 spectra presented 29 carbons, which attributed to seven methyls inclusive of one methoxyl, six methylenes, 12 methines (three oxygenated), and four quaternary carbons. Typical signals of a sterol, such as, a side-chain olefine (δH 5.15–5.19, m; 5.19–5.22, m), four doublet methyls (δH 0.82, d, 6.6; 0.85, d, 6.6; 0.92, d, 6.6; 1.02, d, 6.0), and two singlet methyls (δH 0.63, s; 1.30, s) were observed from the 1H-NMR spectrum. Comparison of the 1H- and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of compound 1 with those of (22E)-4α,5α-epoxyergosta-7,22-diene-3β,6β-diol, an ergostane-type steriod with molecular formula C28H44O3, isolated from another mushroom Pleurotus eryngii (Kikuchi et al., 2016), the 13C-NMR data were almost the same except for an obvious different chemical shift of C-6. The downshift of C-6 from δH 72.0 to 80.9 suggested that the hydroxyl at C-6 was methylated. The location of the methoxyl at C-6 could also be verified by HMBC correlation from the methoxyl signal at δH 3.38 to δC 80.9 (C-6). Thus, the structure of 1 was determined to be (22E)-4α, 5α-epoxy-6β-methoxyergosta-7, 22-diene-3β-ol (Figure 3). Compound 1 was a new compound has not been reported. The complete assignment of the protons and carbons were summarized in Table 1. The key HMBC and 1H-1H COSY correlations were also shown in Figure 4.

(3β, 5α, 6β, 22E)-ergosta-7, 9 (11), 22-triene-3, 5, 6-triol (2): a white powder; Its negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) at 427 [M–H]−, 855 [2M–H] − indicated the molecular weight was 428. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 4.10–4.12 (1H, m, H-3), 3.80 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.45 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 5.75 (1H, d, 6.6, H-11), 0.62 (3H, s, H-18), 1.28 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.26 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 29.7 (C-1), 31.0 (C-2), 67.7 (C-3), 42.2 (C-4), 75.3 (C-5), 74.0 (C-6), 118.2 (C-7), 138.9 (C-8), 140.0 (C-9), 40.7 (C-10), 126.4 (C-11), 42.6 (C-12), 42.6 (C-13), 51.5 (C-14), 23.2 (C-15), 28.7 (C-16), 56.0 (C-17), 11.5 (C-18), 26.3 (C-19), 40.3 (C-20), 20.8 (C-21), 135.2 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.1 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Based on these 1H- and 13C-NMR data, compound 2 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6β, 22E)-ergosta-7, 9 (11), 22-triene-3, 5, 6-triol by comparison with the data reported previously (Ishizuka et al., 1997).

(3β, 5α, 6β, 9α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9-tetrol (3): a white powder; Its molecular weight was 446 by negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) at 445 [M–H]−, 891 [2M–H] −. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.41–3.43 (1H, m, H-3), 3.55 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.78 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.60 (3H, s, H-18), 1.11 (3H, s, H-19), 1.00 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.13 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.82 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26, 27) and 0.92 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 29.3 (C-1), 31.6 (C-2), 67.5 (C-3), 40.8 (C-4), 75.5 (C-5), 72.3 (C-6), 121.3 (C-7), 141.7 (C-8), 78.6 (C-9), 41.3 (C-10), 28.5 (C-11), 35.6 (C-12), 44.5 (C-13), 50.9 (C-14), 23.4 (C-15), 28.5 (C-16), 57.1 (C-17), 12.1 (C-18), 22.5 (C-19), 40.4 (C-20), 21.4 (C-21), 135.4 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.5 (C-25), 19.9 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 17.7 (C-28). The 1H- and 13C-NMR data for compound 3 were found to be in agreement with published data for (3β, 5α, 6β, 9α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9-tetrol (Zou et al., 2013).

(3β, 5α, 6β, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6-triol (4): a white powder; The negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) at 429 [M–H]−, 859 [2M–H] −, indicated a molecular weight of 430. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 4.05–4.07 (1H, m, H-3), 3.60 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.38 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.60 (3H, s, H-18), 1.08 (3H, s, H-19), 1.00 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.13 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.82 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26, 27) and 0.92 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 33.0 (C-1), 31.1 (C-2), 67.5 (C-3), 39.6 (C-4), 75.9 (C-5), 73.8 (C-6), 117.6 (C-7), 143.9 (C-8), 43.6 (C-9), 37.2 (C-10), 22.1 (C-11), 39.2 (C-12), 43.7 (C-13), 54.9 (C-14), 22.8 (C-15), 28.0 (C-16), 56.1 (C-17), 12.1 (C-18), 18.9 (C-19), 40.4 (C-20), 21.4 (C-21), 135.4 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.3 (C-25), 19.9 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 17.7 (C-28). Thus, compound 4 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6β, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6-triol by comparison the 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data with the data reported previously (Kawagishi et al., 1988).

(3β, 5α, 6α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6-triol (5): a white powder; The molecular weight of 430 was also determined by negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) at 429 [M–H]−, 859 [2M–H]−. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.98–4.02 (1H, m, H-3), 3.94 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.00 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.59 (3H, s, H-18), 1.05 (3H, s, H-19), 1.26 (3H, d, 6.0, H-21), 5.13 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.82 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.88 (6H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.95 (3H, d, 6.6 Hz, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 39.6 (C-1), 32.2 (C-2), 67.0 (C-3), 32.5 (C-4), 75.8 (C-5), 70.3 (C-6), 121.3 (C-7), 140.8 (C-8), 33.2 (C-9), 39.2 (C-10), 21.5 (C-11), 41.0 (C-12), 43.7 (C-13), 54.9 (C-14), 22.8 (C-15), 28.5 (C-16), 56.0 (C-17), 12.2 (C-18), 17.8 (C-19), 40.4 (C-20), 21.4 (C-21), 135.4 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 40.7 (C-25), 21.3 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 19.7 (C-28). Compound 5 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6-triol by comparison with the data reported previously (Chen et al., 1991).

(3β, 5α, 6α, 9α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9-tetrol (6): a white powder; The negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) displayed quasi-molecular ion peaks at 445 [M–H]−, 891 [2M–H]−, thus its molecular weight was 446. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 4.00–4.03 (1H, m, H-3), 3.93 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.10 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.60 (3H, s, H-18), 1.07 (3H, s, H-19), 1.02 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.15 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.82 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26, 27) and 0.92 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 26.5 (C-1), 30.6 (C-2), 67.4 (C-3), 40.2 (C-4), 77.0 (C-5), 70.3 (C-6), 120.3 (C-7), 142.5 (C-8), 74.6 (C-9), 41.1 (C-10), 28.4 (C-11), 35.4 (C-12), 43.9 (C-13), 50.7 (C-14), 23.0 (C-15), 28.5 (C-16), 56.1 (C-17), 11.9 (C-18), 20.5 (C-19), 40.4 (C-20), 21.4 (C-21), 135.4 (C-22), 132.5 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.3 (C-25), 19.9 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 17.7 (C-28). Based on these 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data, compound 6 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6α, 9α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9-tetrol by comparison with the data reported previously (Yaoita et al., 1998).

(3β, 5α, 6β, 14α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 9 (11), 22-triene-3, 5, 6, 14-tetrol (7): a white powder; Its negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) 443 [M–H]−, 887 [2M–H] − indicated a molecular weight of 444. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 4.04–4.08 (1H, m, H-3), 3.80 (1H, br.s, H-6), 5.85 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 5.55 (1H, d, 6.6, H-11), 0.80 (3H, s, H-18), 1.22 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.26 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 31.3 (C-1), 31.0 (C-2), 67.5 (C-3), 38.3 (C-4), 75.1 (C-5), 73.5 (C-6), 120.2 (C-7), 137.3 (C-8), 138.2 (C-9), 39.4 (C-10), 124.2 (C-11), 37.8 (C-12), 46.0 (C-13), 81.5 (C-14), 35.2 (C-15), 23.8 (C-16), 50.0 (C-17), 16.5 (C-18), 24.3 (C-19), 40.0 (C-20), 22.3 (C-21), 134.5 (C-22), 133.3 (C-23), 43.1 (C-24), 33.0 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Based on these 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data, compound 7 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6β, 14α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 9 (11), 22-triene-3, 5, 6, 14-tetrol by comparison with the data reported previously (Zang et al., 2013).

(3β, 5α, 6β, 9α, 14α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9, 14-pentol (8): a white powder; Its negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) displayed quasi-molecular ion peaks at 461 [M–H]−, 921 [2M–H] −, indicating a molecular weight of 462. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, C5D5N): δH 4.84–4.87 (1H, m, H-3), 4.57 (1H, br.s, H-6), 7.10 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 3.26–3.29 (1H, m, H-15), 1.41 (3H, s, H-18), 1.62 (3H, s, H-19), 1.24 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.75 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.42 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.92 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26, 27) and 1.05 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, C5D5N): δC 27.9 (C-1), 32.7 (C-2), 67.5 (C-3), 42.2 (C-4), 78.6 (C-5), 74.0 (C-6), 123.9 (C-7), 145.0 (C-8), 75.9 (C-9), 41.9 (C-10), 28.5 (C-11), 38.1 (C-12), 48.5 (C-13), 84.7 (C-14), 42.2 (C-15), 28.4 (C-16), 56.6 (C-17), 17.5 (C-18), 22.2 (C-19), 39.9 (C-20), 23.0 (C-21), 135.9 (C-22), 132.8 (C-23), 43.5 (C-24), 33.5 (C-25), 19.9 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 18.1 (C-28). Based on these 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data, compound 8 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6β, 9α, 14α, 22E)-ergosta-7, 22-diene-3, 5, 6, 9, 14-pentol by comparison with the data reported previously (Zhang et al., 2008).

(3β, 5α, 6α, 7α, 22E)-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8, 22-diene-3, 7-diol (9): a white powder; Its negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) displayed quasi-molecular ion peaks at 427 [M–H]−, 855 [2M–H]−, indicating a molecular weight of 428. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.93–3.96 (1H, m, H-3), 3.31 (1H, br.s, H-6), 4.25 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.60 (3H, s, H-18), 1.15 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 30.3 (C-1), 31.0 (C-2), 68.6 (C-3), 39.3 (C-4), 65.7 (C-5), 62.6 (C-6), 67.1 (C-7), 127.0 (C-8), 134.2 (C-9), 38.2 (C-10), 23.4 (C-11), 35.8 (C-12), 42.0 (C-13), 49.6 (C-14), 23.8 (C-15), 28.8 (C-16), 53.7 (C-17), 11.5 (C-18), 22.8 (C-19), 40.4 (C-20), 20.9 (C-21), 135.5 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.0 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Compound 9 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6α, 7α, 22E)-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8, 22-diene-3, 7-diol (Della Greca et al., 1993).

(3β, 5α, 6α, 7α, 22E)-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8 (14), 22-diene-3, 7-diol (10): a white powder; Its molecular weight was also 428 by negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) 427 [M–H]−, 855 [2M–H]−. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.91–3.93 (1H, m, H-3), 3.12 (1H, br.s, H-6), 4.40 (1H, d, 6.0, H-7), 0.86 (6H, s, H-18, 19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.0, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 32.3 (C-1), 31.0 (C-2), 68.6 (C-3), 39.5 (C-4), 67.7 (C-5), 61.3 (C-6), 65.1 (C-7), 125.0 (C-8), 38.8 (C-9), 35.8 (C-10), 19.0 (C-11), 36.6 (C-12), 43.0 (C-13), 152.6 (C-14), 25.0 (C-15), 27.1 (C-16), 56.7 (C-17), 18.1 (C-18), 16.5 (C-19), 39.4 (C-20), 21.0 (C-21), 135.5 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.0 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data of compound 10 were in agreement with previously published data for (3β, 5α, 6α, 7α, 22E)-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8 (14), 22-diene-3, 7-diol (Della Greca et al., 1993).

(3β, 5α, 8α, 22E)-5, 8-epidioxy-ergosta-6, 22-dien-3-ol (11): a white powder; Its molecular weight was the same as compounds 9 and 10. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.91–3.93 (1H, m, H-3), 6.24 (1H, d, 8.4, H-6), 6.50 (1H, d, 8.4, H-7), 0.81 (3H, s, H-18), 0.88 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 34.7 (C-1), 30.1 (C-2), 66.6 (C-3), 37.0 (C-4), 82.2 (C-5), 135.4 (C-6), 130.8 (C-7), 79.4 (C-8), 51.1 (C-9), 36.9 (C-10), 23.4 (C-11), 39.4 (C-12), 44.6 (C-13), 51.6 (C-14), 20.6 (C-15), 28.6 (C-16), 56.2 (C-17), 12.9 (C-18), 18.2 (C-19), 39.7 (C-20), 21.0 (C-21), 135.2 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.0 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Compound 11 was identified as (3β, 5α, 8α, 22E)-5, 8-epidioxy-ergosta-6, 22-dien-3-ol by comparison with the data reported previously (Liu et al., 2007).

(3β, 22E)-ergosta-5, 7, 22-trien-3-ol (12): Colorless crystal; Its molecular weight was 396 also by negative-ion ESI-MS. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.63–3.66 (1H, m, H-3), 5.60 (1H, dd, 6.6, 6.0, H-6), 5.40–5.44 (1H, m, H-7), 0.62 (3H, s, H-18), 0.96 (3H, s, H-19), 1.04 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.18 (1H, dd, 15.6, 7.2, H-22), 5.22 (1H, dd, 15.6, 7.2, H-23), 0.85 (6H, d, 6.6, H-26, 27) and 0.92 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 39.1 (C-1), 32.0 (C-2), 70.5 (C-3), 40.8 (C-4), 139.8 (C-5), 119.6 (C-6), 116.3 (C-7), 141.4 (C-8), 46.2 (C-9), 37.0 (C-10), 21.3 (C-11), 38.4 (C-12), 42.8 (C-13), 54.6 (C-14), 23.0 (C-15), 28.3 (C-16), 55.5 (C-17), 12.1 (C-18), 16.3 (C-19), 40.2 (C-20), 21.3 (C-21), 135.5 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 43.1 (C-24), 33.0 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data for compound 12 were in agreement with previously published data for ergosterol (Kang et al., 2003).

(3β, 5α, 8α, 22E)-5, 8-epidioxy-ergosta-6, 9 (11), 22-trien-3-ol (13): a white powder; Its negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) displayed quasi-molecular ion peaks at 425 [M–H]−, 851 [2M–H]−, indicating a molecular weight of 426. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.91–3.93 (1H, m, H-3), 6.24 (1H, d, 8.4, H-6), 6.50 (1H, d, 8.4, H-7), 0.81 (3H, s, H-18), 0.88 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.81 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.91 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 34.7 (C-1), 30.1 (C-2), 66.6 (C-3), 37.0 (C-4), 82.2 (C-5), 136.4 (C-6), 130.9 (C-7), 78.8 (C-8), 144.2 (C-9), 38.6 (C-10), 119.2 (C-11), 41.5 (C-12), 43.9 (C-13), 48.9 (C-14), 21.6 (C-15), 28.9 (C-16), 56.2 (C-17), 13.2 (C-18), 25.7 (C-19), 40.0 (C-20), 21.0 (C-21), 135.5 (C-22), 132.3 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.4 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Compound 13 was identified as (3β, 5α, 8α, 22E)-5, 8-epidioxy-ergosta-6, 22-dien-3-ol by comparison with the data reported (Ma et al., 1994).

(3β, 5α, 6α, 14α, 22E)-3, 14-dihydroxy-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8, 22-dien-7-one (14): a white powder; The molecular weight of 442 was determined by negative-ion ESI-MS (m/z) 441 [M–H]−, 883 [2M–H] −. 1H-NMR (600MHz, CDCl3): δH 3.94–3.96 (1H, m, H-3), 3.35 (1H, s, H-6), 0.92 (3H, s, H-18), 1.21 (3H, s, H-19), 1.01 (3H, d, 6.6, H-21), 5.16 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-22), 5.25 (1H, dd, 15.0, 7.2, H-23), 0.80 (3H, d, 6.6, H-26), 0.83 (3H, d, 6.6, H-27) and 0.88 (3H, d, 6.6, H-28). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δC 28.9 (C-1), 30.1 (C-2), 68.6 (C-3), 38.3 (C-4), 65.6 (C-5), 62.3 (C-6), 200.2 (C-7), 133.1 (C-8), 157.0 (C-9), 40.7 (C-10), 23.0 (C-11), 29.8 (C-12), 44.9 (C-13), 80.9 (C-14), 35.4 (C-15), 25.9 (C-16), 44.8 (C-17), 16.3 (C-18), 23.0 (C-19), 39.8 (C-20), 21.0 (C-21), 135.0 (C-22), 132.7 (C-23), 42.8 (C-24), 33.2 (C-25), 19.7 (C-26), 20.0 (C-27), and 17.6 (C-28). Compound 14 was identified as (3β, 5α, 6α, 14α, 22E)-3, 14-dihydroxy-5, 6-epoxy-ergosta-8, 22-dien-7-one (Wu et al., 2011).

Among the 13 known compounds, compound 7 and 14 were isolated from G. lucidum for the first time. This work further enriched our knowledge about the chemical constituents of G. lucidum.

Anti-proliferative activity evaluation against two types of human cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 and HepG2), HUVECs and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NIH/3T3, used as normal cells) were then carried out. The activities results were shown in Table 2. Compounds 2, 9–13 showed inhibitory activities against the two tumor cell lines, with IC50-values below 100 μM. Especially compounds 9–11 exhibited stronger inhibition against cancer cells compared to the positive control drug kaempferol. Compound 2 exhibited a significant selective inhibition against cancer cells rather than the human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Compounds 3, 9–13 showed inhibitory activities against HUVECs, with IC50-values in the range of 27.9–84.0 μM. Among these bioactive compounds, compounds 9 and 11 showed the strongest activities. Compounds 9–13 showed inhibitory activities against two tumor cell lines as well as HUVECs, which indicated that these four compounds may had multi-target effects on tumor. In additional, all the tested compounds showed no obvious cytotoxicity on the normal cells NIH/3T3, with selective index (SI) greater than 2.

Previously our research group had found ergosterol peroxide and ergosterol, which were also found in G. lucidum in current work (compounds 11 and 12), could activate Foxo3-mediated cell apoptosis signaling in human hepatocellular carcimoma cells and human breast carcimoma cells (Li et al., 2015, 2016). In present work, we found compounds 11 and 12 inhibited the proliferation of HUVECs, which reminded us that the anti-tumor mechanism of compound 11 and 12 may include multi-targets and multi-approaches except tumor cell apoptosis pathway. Signaling pathways about cell death as well as angiogenesis should be considered. Besides, compound 9 exhibited stronger inhibitory effect against tumor cells than that of ergosterol peroxide (11) and ergosterol (12). The anti-tumor mechanism of compound 9 in vitro and in vivo will also be explored in our future work.

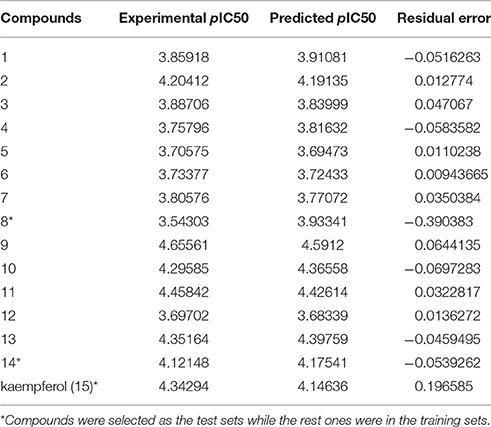

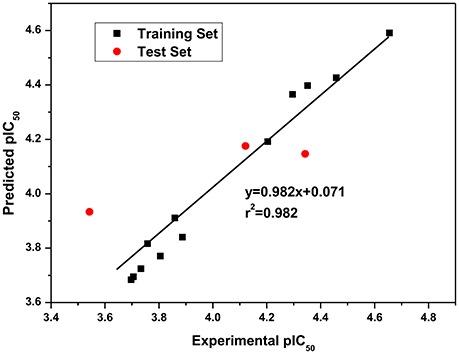

Since QSAR was a valuable method for novel drug discovery from knowledge in literature and tested bioactive data (Liao et al., 2011), 3D-QSAR was performed for human HepG2 cells. Herein, the selected compounds (1–15) for model establishment with IC50s spanning from 21.2 to 286.4 μM were randomized into training set with the ration of 0.80 and test set of 0.20 by Generate Training and Test Data in DS. pIC50s converted were between 3.70 and 4.66. The established model presented a good correlation coefficient (r2) up to 0.982 between observed and predicted activities for training set and 0.861 for test set, which suggested the reliability in external validation. In model generation, 5-fold cross validation of the training set molecules was performed to validating the model, where RMS was at 0.337 and q2 at 0.002. This suggested the reliability of this model in internal validation. The pIC50s of assayed and predicted with this model and residual errors were shown (Table 3). Illustratively, a plot was offered (Figure 5), where the correlative relationship between actual and predicted values suggested that this model was reliable for forecasting activities of compounds for HepG2 cells.

Table 3. Experimental and predicted inhibitory activities of 15 compounds by 3D-QSAR model against HepG2.

Figure 5. Experimental versus predicted HepG2 inhibitory activities of the training set and the test set. The well agreement between predicted pIC50-value and experimental pIC50-value for both test sets and training sets indicated that this model was reliable in forecasting activity for the listed compounds.

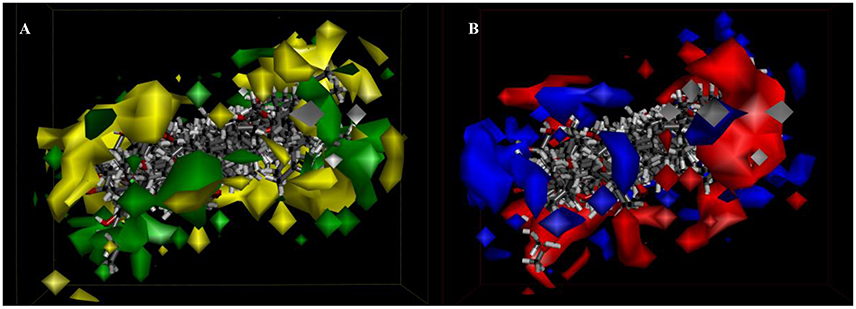

Besides, iso-surfaces of the model on van der Waals (Figure 6A) and electrostatic potential grids (Figure 6B) were provided and aligned by compounds. Accordingly, at C-2, C-3, C-22, and C-28 sites some bulk substituents with slight negative charges might enhance compound 2's activity. Also, at C-20 and C-18 slight large groups with some positive charge could elevate activity for compound 2. But at C-1, C-4, C-11, C-26, and C-27, bulk substitutes might lower activity. Moreover, interchange of C-1, C-2, and C-3 by atoms of negative charge might enhance activity. Evidently, partial hydroxyl negative groups with slight steric hindrance at C-9 and C-14 decline activity to 286.4 μM (IC50) for compound 8 (approximately 4.6-folds) in comparison with compound 2 (62.5 μM). However, the introduction of partial hydroxyl negative groups with slight steric hindrance at C-7 and replacement of double hydroxyl groups at C-5 and C-6 with a more slight steric hindrance and more negative epoxy group increase the activity to 22.1 μM for compound 9 (approximately 3-folds) compared with compound 2. In the words of the most bioactive compound 9, replacement of hydroxyl group at C-7 with a bulky and negative group may increase its activity. Besides, introduction of small positive group at C-28 may elevate its activity. The results will be helpful for designing higher active ergosterol derivatives in our future work.

Figure 6. 3D-QSAR model. (A) 3D-QSAR model coefficients of the listed compounds on van der Waals grids. Green represents positive coefficients; yellow represents negative coefficients. (B) 3D-QSAR model coefficients on electrostatic potential grids. Blue represents positive coefficients; red represents negative coefficients.

Ergosterol, the pro-vitamin D2, is a characteristic secondary metabolite of medicinal and edible fungi, and shows a variety of biological activities. In our previous study, we found that ergosterol purified from A. rude, induced tumor cell death and inhibited tumor cell cycle progression, cell migration, and colony growth of MDA-MB-231 cells (Li et al., 2015). Ergosterol prolonged animal survival by upregulating Foxo3 and its downstream molecules Bim, Fas, and Fas L. Ergosterol was also rich in G. lucidum and other fungi.

As an important active component in G. lucidum, we quantified the contents of ergosterol in different parts of G. lucidum and functional foods derived from G. lucidum by HPLC. The calibration curves, linear ranges, and recovery of the HPLC method were performed. The linear range of ergosterol was from 20 to 200 μg/mL (r = 0. 9994) with an average recovery of 93.32% (RSD was 2.60%, n = 9), demonstrating that the HPLC method was precise and accurate enough for quantitative evaluation of ergosterol.

Table 4 showed the content of ergosterol in different parts, including fruiting body, spore and, mycelium of G. lucidum and functional foods (spore extract capsule and spore oil capsule) derived from G. lucidum. The results suggested the content of ergosterol in different part of raw material of G. lucidum was mycelium > fruiting body > spore. Ergosterol in mycelium was about 20 times higher than that in spore. For G. lucidum spore products, the ergosterol content was much higher than that of spore raw material. However, the quality homogeneity of G. lucidum spore oil capsule products was poor. Considering the significant difference of ergosterol content of G. lucidum spore oil capsule, the content variation of G. lucidum products may attribute to: (1) Variation of preparation techniques, and (2) Variation of raw materials.

Fourteen ergosterol derivatives including a new one were isolated from the lipids enriched fraction of G. lucidum. Compounds 9–13 displayed potential inhibitory activity against MDA-MB-231, HepG2, and HUVECs, which indicated that these four compounds had both anti-tumor and anti-angiogenesis activities. Compound 2 had significant selective inhibition against two tumor cell lines, while 3 exhibited selective inhibition against HUVECs. All the compounds showed no obvious cytotoxicity on the normal cells. Their structure–activity relationships for inhibiting HepG2 cells were studied by 3D-QASR. The content of ergosterol in different parts of raw material and preparations of G. lucidum were compared, and ergosterol was the highest contented in mycelium. However, the quality homogeneity of G. lucidum spore oil capsule products was poor. This study not only enriches the understanding of the diversity of ergosterols in G. lucidum, but also provides a basis for further development and utilization of ergosterol derivatives as natural nutraceuticals and functional food ingredients, or as source of new potential antitumor or anti-angiogenesis chemotherapy agent.

SC was responsible for the concept and design of the study. SC did the isolation and identification of the chemical constituents, evaluated the compounds' activities and wrote the manuscript. TY conducted the QSAR experiment and YZ performed the quantitative analysis. JS, CJ, and YX conducted part of the experiments. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript, and have approved the final version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was funded by the High-level Leading Talent Introduction Program of GDAS (No. 2016GDASRC-0102), Guangdong Province Science and Technology Project (No. 2016A030303041, 2017A030303055) and Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (No. 201707020022).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2017.00085/full#supplementary-material

Berz, D., and Wanebo, H. (2011). Targeting the growth factors and angiogenesis pathways: small molecules in solid tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 103, 574–586. doi: 10.1002/jso.21776

Boh, B. (2013). Ganoderma lucidum: a potential for biotechnological production of anti-cancer and immunomodulatory drugs. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 8, 255–287. doi: 10.2174/1574891X113089990036

Bouic, P. J. (2002). Sterols and sterolins: new drugs for the immune system? Drug Discov. Today 7, 775–778. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(02)02343-7

Chang, C. J., Lin, C. S., Lu, C. C., Martel, J., Ko, Y. F., Ojcius, D. M., et al. (2015). Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 6:7489. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8489

Chen, R., Wang, Y., and Yu, D. (1991). Chemical constituents of the spores from Ganoderma lucidum. Zhiwu Xuebao 33, 65–68.

Chen, S., Li, X., Yong, T., Wang, Z., Su, J., Jiao, C., et al. (2017). Cytotoxic lanostane-type triterpenoids from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum and their structure-activity relationships. Oncotarget 8, 10071–10084. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14336

Della Greca, M., Fiorentino, A., Molinaro, A., Monaco, P., and Previtera, L. (1993). Steroidal 5,6-epoxides from Arum italicum. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2, 27–32. doi: 10.1080/10575639308043450

de Macedo-Silva, S. T., de Souza, W., and Rodrigues, J. C. (2015). Sterol biosynthesis pathway as an alternative for the anti-protozoan parasite chemotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 22, 2186–2198. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150319120337

Fan, L., Pan, H., Soccol, A. T., Pandey, A., and Soccol, C. R. (2006). Advances in mushroom research in the last decade. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 44, 303–311.

Folkman, J. (1971). Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 285, 1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108

Franchi, G. C. Jr., Moraes, C. S., Toreti, V. C., Daugsch, A., Nowill, A. E., and Park, Y. K. (2012). Comparison of effects of the ethanolic extracts of brazilian propolis on human leukemic cells as assessed with the MTT assay. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012:918956. doi: 10.1155/2012/918956

Gill, B. S., Sharma, P., Kumar, R., and Kumar, S. (2016). Misconstrued versatility of Ganoderma lucidum: a key player in multi-targeted cellular signaling. Tumour Biol. 37, 2789–2804. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4709-z

Ha do, T., Oh, J., Khoi, N. M., Dao, T. T., Dung le, V., Do, T. N., et al. (2013). In vitro and in vivo hepatoprotective effect of ganodermanontriol against t-BHP-induced oxidative stress. J. Ethnopharmacol. 150, 875–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.039

Ishizuka, T., Yaoita, Y., and Kikuchi, M. (1997). Sterol constituents from the fruit bodies of Grifola frondosa (Fr.) S. F. gray. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 45, 1756–1760. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.1756

Joy, M., Chakraborty, K., and Raola, V. K. (2017). New sterols with anti-inflammatory potentials against cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase from Paphia malabarica. Nat. Prod. Res. 31, 1286–1298. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1242001

Kang, J., Wang, H., and Chen, R. (2003). Studies on the constituents of the mycelium produced by fermenting culture of Flammulina velutipes (W. Curt.:Fr.) Singer (Agaricomycetideae). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 5, 391–396. doi: 10.1615/InterJMedicMush.v5.i4.60

Kawagishi, H., Katsumi, R., Sazawa, T., Mizuno, T., Hagiwara, T., and Nakamura, T. (1988). Cytotoxic steroids from the mushroom Agaricus blazei. Phytochemistry 27, 2777–2779. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80662-9

Kiem, P. V., Dung, D. T., Trang, D. T., Quang, T. H., Nguyen, T. T. N., Ha, T. M., et al. (2017). Constituents from Ircinia echinata and their antiproliferative effect on six human cancer cell strains. Lett. Org. Chem. 14, 248–253. doi: 10.2174/1570178614666170310123051

Kikuchi, T., Maekawa, Y., Tomio, A., Masumoto, Y., Yamamoto, T., In, Y., et al. (2016). Six new ergostane-type steroids from king trumpet mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii) and their inhibitory effects on nitric oxide production. Steroids 115, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.07.005

Kim, S. K., and Ta, Q. V. (2011). Potential beneficial effects of marine algal sterols on human health. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 64, 191–198. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387669-0.00014-4

Kuo, C. F., Hsieh, C. H., and Lin, W. Y. (2011). Proteomic response of LAP-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages to the anti-inflammatory property of fungal ergosterol. Food Chem. 126, 207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.10.101

Li, B., Lee, D. S., Kang, Y., Yao, N. Q., An, R. B., and Kim, Y. C. (2013). Protective effect of ganodermanondiol isolated from the Lingzhi mushroom against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatotoxicity through Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 53, 317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.016

Li, W., Zhou, W., Song, S. B., Shim, S. H., and Kim, Y. H. (2014). Sterol fatty acid esters from the mushroom Hericium erinaceum and their PPAR transactivational effects. J. Nat. Prod. 77, 2611–2618. doi: 10.1021/np500234f

Li, X., Wu, Q., Bu, M., Hu, L., Du, W. W., Jiao, C., et al. (2016). Ergosterol peroxide activates Foxo3-mediated cell death signaling by inhibiting AKT and c-Myc in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 7, 33948–33959. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8608

Li, X., Wu, Q., Xie, Y., Ding, Y., Du, W. W., Sdiri, M., et al. (2015). Ergosterol purified from medicinal mushroom Amauroderma rude inhibits cancer growth in vitro and in vivo by up-regulating multiple tumor suppressors. Oncotarget 6, 17832–17846. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4026

Liang, F., Han, Y., Gao, H., Xin, S., Chen, S., Wang, N., et al. (2015). Kaempferol identified by zebrafish assay and fine fractionations strategy from Dysosma versipellis inhibits angiogenesis through VEGF and FGF pathways. Sci. Rep. 5:14468. doi: 10.1038/srep14468

Liao, C., Sitzmann, M., Pugliese, A., and Nicklaus, M. C. (2011). Software and resources for computational medicinal chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 3, 1057–1085. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.63

Liu, C., Wang, H. Q., Li, B. M., and Chen, R. Y. (2007). Studies on chemical constituents from the fruiting bodies of ganoderma sinense Zhao, Xu et Zhang. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 32, 235–237.

Loria-Kohen, V., Lourenco-Nogueira, T., Espinosa-Salinas, I., Marin, F. R., Soler-Rivas, C., and Ramirez de Molina, A. (2014). Nutritional and functional properties of edible mushrooms: a food with promising health claims. J. Pharm. Nutr. Sci. 4, 187–198. doi: 10.6000/1927-5951.2014.04.03.4

Loza-Mejia, M. A., and Salazar, J. R. (2015). Sterols and triterpenoids as potential anti-inflammatories: molecular docking studies for binding to some enzymes involved in inflammatory pathways. J. Mol. Graphics Model. 62, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2015.08.010

Luo, Y., Zhou, Y., Fu, J., and Zhu, H. L. (2014). 4,5-Dihydropyrazole derivatives containing oxygen-bearing heterocycles as potential telomerase inhibitors with anticancer activity. RSC Adv. 4, 23904–23913. doi: 10.1039/c4ra02200a

Ma, H. T., Hsieh, J. F., and Chen, S. T. (2015). Anti-diabetic effects of Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochemistry 114, 109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.02.017

Ma, W., Li, X., Wang, D., and Yang, C. (1994). Ergosterol peroxides from Cryptoporus volvatus. Yunnan Zhiwu Yanjiu 16, 196–200.

McDougall, S. R., Anderson, A. R., and Chaplain, M. A. (2006). Mathematical modelling of dynamic adaptive tumour-induced angiogenesis: clinical implications and therapeutic targeting strategies. J. Theor. Biol. 241, 564–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.12.022

Mille-Lindblom, C., von Wachenfeldt, E., and Tranvik, L. J. (2004). Ergosterol as a measure of living fungal biomass: persistence in environmental samples after fungal death. J. Microbiol. Methods 59, 253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.07.010

Min, B. S., Nakamura, N., Miyashiro, H., Bae, K. W., and Hattori, M. (1998). Triterpenes from the spores of Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 46, 1607–1612. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1607

Montserrat-de la Paz, S., Fernandez-Arche, M. A., Bermudez, B., and Garcia-Gimenez, M. D. (2015). The sterols isolated from evening primrose oil inhibit human colon adenocarcinoma cell proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest through upregulation of LXR. J. Funct. Foods 12, 64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.11.004

Nguyen, V. T., Tung, N. T., Cuong, T. D., Hung, T. M., Kim, J. A., Woo, M. H., et al. (2015). Cytotoxic and anti-angiogenic effects of lanostane triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochem. Lett. 12, 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2015.02.012

Pan, D., Wang, L., Chen, C., Hu, B., and Zhou, P. (2015). Isolation and characterization of a hyperbranched proteoglycan from Ganoderma lucidum for anti-diabetes. Carbohydr. Polym. 117, 106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.09.051

Papetti, M., and Herman, I. M. (2002). Mechanisms of normal and tumor-derived angiogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C947–C970. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00389.2001

Rios, J. L., Andujar, I., Recio, M. C., and Giner, R. M. (2012). Lanostanoids from fungi: a group of potential anticancer compounds. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 2016–2044. doi: 10.1021/np300412h

Sang, Y. L., Duan, Y. T., Qiu, H. Y., Wang, P. F., Makawana, J. A., Wang, Z. C., et al. (2014). Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking of novel metronidazole derivatives as selective and potent JAK3 inhibitors. RSC Adv. 4, 16694–16704. doi: 10.1039/C4RA01444H

Sliva, D. (2006). Ganoderma lucidum in cancer research. Leuk. Res. 30, 767–768. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.12.015

Wang, J., Yuan, Y., and Yue, T. (2014a). Immunostimulatory activities of beta-d-glucan from Ganoderma Lucidum. Carbohydr. Polym. 102, 47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.087

Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Yuan, Y., and Yue, T. (2014b). Immunomodulatory of selenium nano-particles decorated by sulfated Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides. Food Chem. Toxicol. 68, 183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.003

Weete, J. D., and Laseter, J. L. (1974). Distribution of sterols in the fungi. I. Fungal spores. Lipids 9, 575–581. doi: 10.1007/BF02532507

Weng, Y., Xiang, L., Matsuura, A., Zhang, Y., Huang, Q., and Qi, J. (2010). Ganodermasides A and B, two novel anti-aging ergosterols from spores of a medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum on yeast via UTH1 gene. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 999–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.070

Wu, J., Choi, J. H., Yoshida, M., Hirai, H., Harada, E., Masuda, K., et al. (2011). Osteoclast-forming suppressing compounds, gargalols A, B, and C, from the edible mushroom Grifola gargal. Tetrahedron 67, 6576–6581. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.05.091

Wu, J. G., Kan, Y. J., Wu, Y. B., Yi, J., Chen, T. Q., and Wu, J. Z. (2016). Hepatoprotective effect of ganoderma triterpenoids against oxidative damage induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide in human hepatic HepG2 cells. Pharm. Biol. 54, 919–929. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1091481

Yaoita, Y., Amemiya, K., Ohnuma, H., Furumura, K., Masaki, A., Matsuki, T., et al. (1998). Sterol constituents from five edible mushrooms. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 46, 944–950. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.944

Yasukawa, K., Aoki, T., Takido, M., Ikekawa, T., Saito, H., and Matsuzawa, T. (1994). Inhibitory effects of ergosterol isolated from the edible mushroom Hypsizigus marmoreus on TPA-induced inflammatory ear oedema and tumour promotion in mice. Phytother. Res. 8, 10–13. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650080103

Zang, Y., Xiong, J., Zhai, W. Z., Cao, L., Zhang, S. P., Tang, Y., et al. (2013). Fomentarols A-D, sterols from the polypore macrofungus Fomes fomentarius. Phytochemistry 92, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.05.003

Zhang, C. R., Yang, S. P., and Yue, J. M. (2008). Sterols and triterpenoids from the spores of Ganoderma lucidum. Nat. Prod. Res. 22, 1137–1142. doi: 10.1080/14786410601129721

Zhang, Y., Mills, G. L., and Nair, M. G. (2002). Cyclooxygenase inhibitory and antioxidant compounds from the mycelia of the edible mushroom Grifola frondosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 7581–7585. doi: 10.1021/jf0257648

Zhao, Y. Y. (2013). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and quality control of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 149, 35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.031

Zhu, R., Zheng, R., Deng, Y., Chen, Y., and Zhang, S. (2014). Ergosterol peroxide from cordyceps cicadae ameliorates TGF-β1-induced activation of kidney fibroblasts. Phytomedicine 21, 372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.08.022

Keywords: Ganoderma lucidum, ergosterols, anti-tumor, anti-angiogenic, QSAR

Citation: Chen S, Yong T, Zhang Y, Su J, Jiao C and Xie Y (2017) Anti-tumor and Anti-angiogenic Ergosterols from Ganoderma lucidum. Front. Chem. 5:85. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00085

Received: 03 August 2017; Accepted: 09 October 2017;

Published: 30 October 2017.

Edited by:

Weien Yuan, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jun-Seok Lee, Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), South KoreaCopyright © 2017 Chen, Yong, Zhang, Su, Jiao and Xie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaodan Chen, c2hhb2RhbmNoZW5AMTI2LmNvbQ==

Yizhen Xie, MTM2MjIyMTY0OTBAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.