- Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, MD, United States

Inflammation-related disorders, such as autoimmune diseases and cancer, impose a significant global health burden. Zinc finger proteins (ZFs) are ubiquitous metalloproteins which regulate inflammation and many biological signaling pathways related to growth, development, and immune function. Numerous ZFs are involved in the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) pathway, associating them with inflammation-related diseases that feature chronically elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines. This review highlights the predominance of ZFs in NFκB-related signaling and summarizes the breadth of functions that these proteins perform. The cysteine-specific post-translational modification (PTM) of persulfidation is also discussed in the context of these cysteine-rich ZFs, including what is known from the few available reports on the functional implications of ZF persulfidation. Persulfidation, mediated by endogenously produced hydrogen sulfide (H2S), has a recently established role in signaling inflammation. This work will summarize the known connections between ZFs and persulfidation and has the potential to inform on the development of related therapies.

1 Introduction

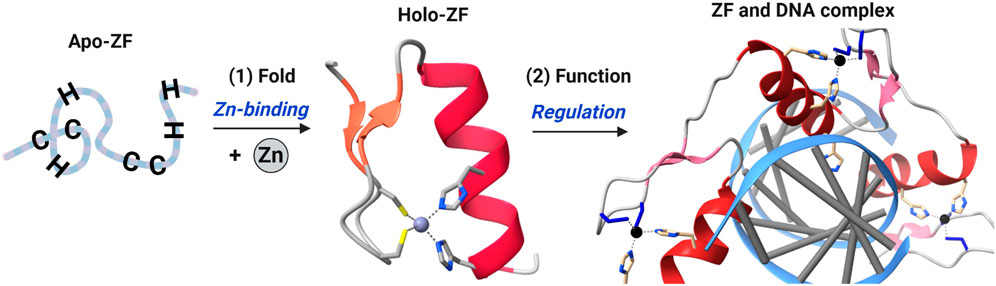

Metals are critically important to biological processes. In cells, metal-cofactored proteins or metalloproteins constitute about 30–40% of the total proteome, and new biological roles continue to be discovered (Rosato et al., 2016; Zhang and Zheng, 2020). Common metal co-factors in proteins include transition metals such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and alkali/alkali-earth metals such as sodium (Na), calcium (Ca) and potassium (K). Zn(II) is the second most common transition metal found in biology, after iron (Hierons et al., 2021; Jomova et al., 2022; O'Halloran and Culotta, 2000; Robinson and Glasfeld, 2020). Three roles have been ascribed to zinc: structural, catalytic and signaling. The structural role for zinc involves the metal binding to specific ligands of a protein leading to a defined protein structure. These proteins are called zinc finger (ZF) proteins (Lee and Michel, 2014) (Figure 1). The catalytic role involves zinc binding to specific ligands of a protein that includes an open site for substrate binding, with typical chemistry including hydrolysis and electron transfer; examples of these proteins include carbonic anhydrase, thermolysin and metallo β-lactamases (Coleman, 1998; Pettinati et al., 2016; Zastrow and Pecoraro, 2014). A signaling role for zinc has been invoked when describing zinc ‘sparks’ during embryonic development and, more broadly, for cell cycle progression (Lo et al., 2020; Que et al., 2015; Warowicka et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2013; Zinatizadeh et al., 2021). Similarly, ZFs contribute to multiple signaling pathways by functioning as transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulators. ZF dysfunction has been linked to numerous pathologies, including developmental, neurodegenerative, and immune disorders (Behrens and Heissmeyer, 2022; Bu et al., 2021; Cassandri et al., 2017; Patial and Blackshear, 2016; Sun, 2017; Todorova et al., 2015; Vilas et al., 2018; Yoshinaga and Takeuchi, 2019). These conditions are associated with chronic inflammation and increased inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, interleukins, etc.), in part from persistent activation of the NFκB signaling pathway.

Figure 1. Cartoon diagram of zinc finger (ZF) domain structure and function. Zn(II) binding to a ZF domain results in a folded domain which can then recognize and bind to another macromolecule (often DNA or RNA) to function via regulation of transcription or translation. ZF shown is Zif268, PDB ID – 1AAY.

The NFκB pathway is stimulated by a plethora of endogenous and exogenous agonists (i.e., TNFα and LPS, respectively) which ultimately lead to formation of an NFκB complex that translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to act as a transcriptional activator of stress-response genes. ZFs are heavily involved in both the transduction (pro-inflammatory) and the repression (anti-inflammatory) of the signal. Post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, are essential to NFκB signaling and mediated, in part, by ZF activity. As ZFs are Cys-rich domains, they are also subject to several sulfur centered modifications, such as nitrosylation (Cys-SNO), persulfidation (Cys-SSH), and glutathionylation (Cys-SSG) (Checconi et al., 2019; Dyer et al., 2019; Vignane and Filipovic, 2023). There are many ways for the cell to adjust ZF function via PTMs and modulate their regulation of signaling. This review discusses the role of ZFs throughout the NFκB pathway, their associations with disease, and the functional implications of ZF persulfidation, a recently identified PTM of ZFs (Li et al., 2024; Stoltzfus et al., 2024).

2 Zinc finger proteins: origins, classifications, and ubiquity in mammalian biology

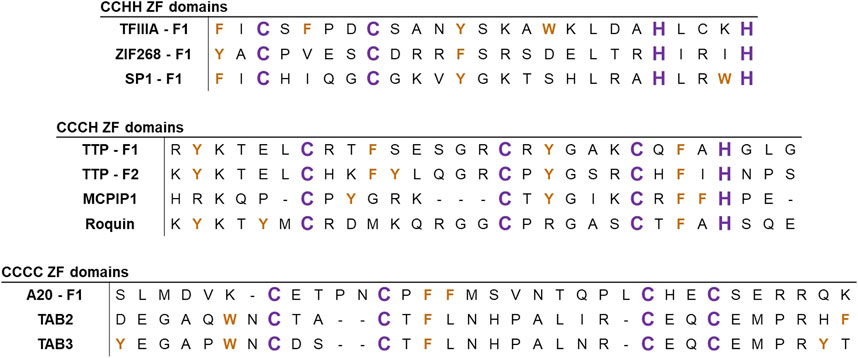

ZF proteins contain conserved repeats of four cysteine (Cys, C) and/or histidine (His, H) residues within their primary amino acid sequence (Besold et al., 2010; Michalek et al., 2011). These residues serve as ligands to coordinate zinc in a tetrahedral geometry resulting in a folded protein (Lee and Michel, 2014). The first protein to be identified as a ZF was transcription factor IIIA (TFIIIA) from Xenopus laevis (Miller et al., 1985; Taylor and Segall, 1985). TFIIIA contains eight ZF domains with a sequence of CX4-CX12-HX3-H along with a singular domain of CX4-CX6-HX5-H (Shastry, 1996). Bioinformatic comparisons of TFIIIA’s sequence led to the structural proposal of finger-shaped domain repeats which could bind non-coding regions of DNA and regulate downstream transcription (Berg, 1986). The first ZF crystal structure of Zif268, in addition to subsequent structures of TFIIIA and related homologs, established the ββα fold of the “classical” ZF domain (Foster et al., 1997; Pavletich and Pabo, 1991). Upon zinc binding, the classical ZF adopts a structure in which each domain has a ββα fold with a hydrophobic core made up of three conserved aromatic residues (W, Y, F) preceding the first Cys and in the CX12-H linker region (Figure 2, top) (Padjasek et al., 2020). Classical (CCHH) ZFs are transcription factors, and each ZF domain binds to specific GC-rich DNA sequences via hydrogen bonding interactions between side chains on the α helices and bases on the DNA (Chabert et al., 2019; Kluska et al., 2018; Negi et al., 2023).

Figure 2. Alignments of the ZF sequences of several representative ZFs. Sequences are aligned based on C/H domains, with examples of ZFs involved in NFκB signaling. Zn(II)-coordinating ligands (C and H) are colored in purple and aromatic residues (W, Y, and F) are colored in orange.

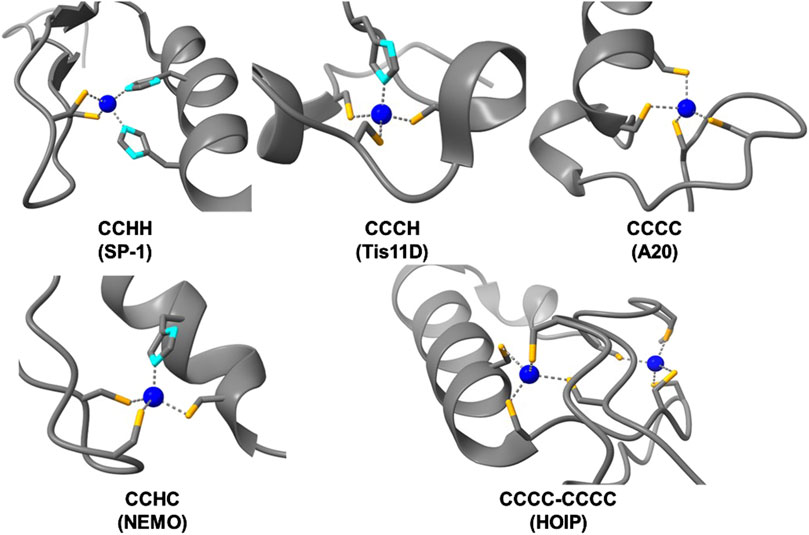

Since the discovery of CCHH ZFs in the 1980s, more than 30 types of non-classical ZFs have been identified. These ZFs are predominantly known for RNA binding and other forms of post-transcriptional regulation. Non-classical ZFs contain different combinations of Cys and His ligands (e.g., CCCH, CCHC, and CCCC) with varied spacing between the ligands (Michalek et al., 2011; Padjasek et al., 2020; Pritts and Michel, 2022) (Figure 2, middle and bottom). In total, ZF domains exhibit a diverse array of peptide folds and DNA/RNA binding modalities across the multitude of classes and structures (Figure 3) (Lee and Michel, 2014; Ok et al., 2021; Yoshinaga and Takeuchi, 2019). As such, ZFs are integral regulators of cell signaling at the level of transcription, translation, and post-translation (i.e., stabilizing and/or destabilizing ubiquitination) (Fennell et al., 2018; Kaczynski et al., 2003; Louis et al., 2021; Pikkarainen et al., 2004; Tu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2013).

Figure 3. Structures of zinc bound ZF domains of varying Cys/His compositions (Cys-sulfur atoms are colored in orange, His-nitrogen atoms are colored in light blue, and Zn(II) atoms are colored in dark blue). PDBs used, from top left to bottom right: SP1 – 1VA1, Tis11D – 1RGO, A20 – 3OJ3, NEMO – 5AAY, HOIP – 6SC6.

As the complexity of organisms increases, so too does the abundance of ZFs within the respective proteomes (Andreini et al., 2006b). This abundance and diversity of ZFs is exemplified in humans, where 8.9% of all proteins contain at least one ZF domain (Andreini et al., 2006a; Bertini et al., 2010). The abundance of Cys residues relative to all amino acids similarly increases with organism complexity, with humans having the highest proportion, at 2.3% Cys (Garrido Ruiz et al., 2022; Go et al., 2015; Wiedemann et al., 2020). This increase in ZFs may be related to the increase in Cys sites, as Zn(II) is redox inert, offering protection for redox sensitive Cys thiols during oxidative stress. The increased frequency and utilization of ZF domains highlights their importance in biological development and cell signaling pathways.

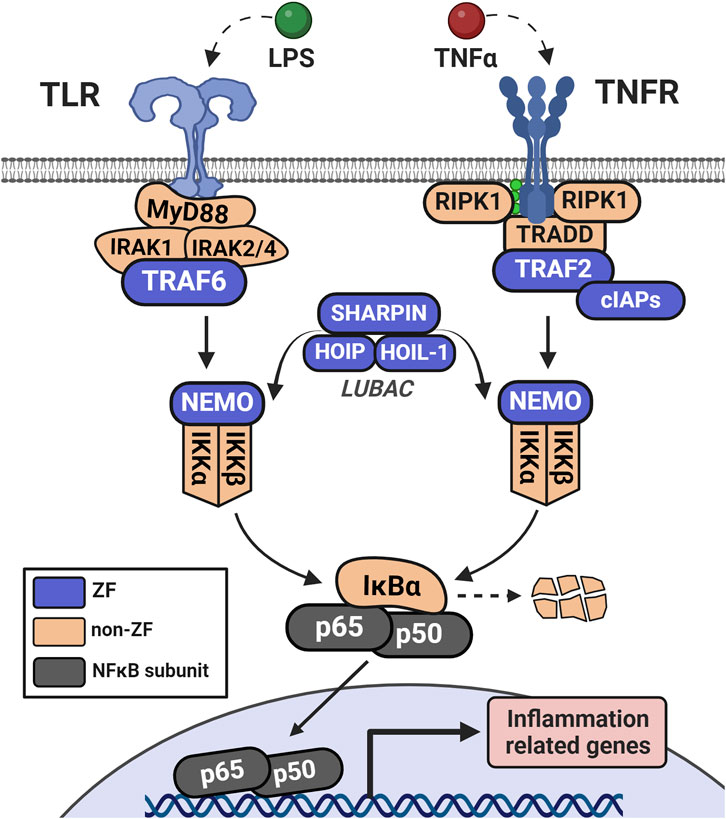

One pathway for which ZFs play key roles is the nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) signaling pathway, where ZFs modulate NFκB activity throughout the phases of stimulation, signal transduction, and resolution (Figure 4) (Tokunaga et al., 2011). ZFs are associated with immune modulation, apoptosis, cell proliferation, and cancer (Guo et al., 2017; Jarosz et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2021; Lipkowitz and Weissman, 2011; Park et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019). There are a variety of stimuli for distinct NFκB subunits, leading to canonical or non-canonical NFκB activation. Canonical activation occurs when the NFκB subunits p65 and p50 are liberated from their NFκB-inhibitor-alpha (IκBα)-mediated cytoplasmic restriction, translocate to the nucleus, and dimerize to act as a transcriptional regulator (Lu et al., 2021). The non-canonical pathway initiates with signal-induced p100 processing, regulated by NFκB-inducible kinase (NIK)-dependent phosphorylation, leading to non-canonical NFκB subunits p52 and RELB translocating and upregulating transcription (Sun, 2017). There is overlap of the stimuli and receptors (for example, TNFα/TNF-receptor family) which lead to activation of either pathway, and thus NFκB signaling often occurs via both mechanisms simultaneously rather than discretely (Lu et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2022). This review focuses on the canonical NFκB pathway and associated ZFs.

Figure 4. Initiation of NFκB signaling via LPS or TNFα involves distinct receptor-adaptor complexes that both lead to activation of the IKK complex (IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO). This complex phosphorylates IκBα which leads to its ubiquitination and degradation, de-repressing the NFκB complex (in this case, p50 and p65) and allowing it to translocate to the nucleus. NFκB then acts as a transcription factor to upregulate a host of inflammation-related genes.

3 ZF regulation of the NFκB signaling pathway

3.1 Human proteome sorting of ZFs involved in NFκB signaling

To identify the ZFs that play roles in NFκB signaling, the full list of reviewed H. sapiens proteins in Uniprot (n = 20,428 total proteins) was filtered based upon the presence of at least one annotated ZF domain (n = 1,814 total proteins with ZF annotation). This list of ZFs was then analyzed using DAVID software (NIH), a web-based server for functional enrichment analysis of gene lists, using H. sapiens as the background gene list to match the Uniprot accessions (Sherman et al., 2022). With the gene list in DAVID, pathway analysis by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) knowledge database was selected (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000). KEGG analysis was employed because it yielded the highest number of gene hits (17) for ZFs in the NF-kappa B signaling pathway (KEGG designation hsa04064; Table 1; Supplementary Table S1).

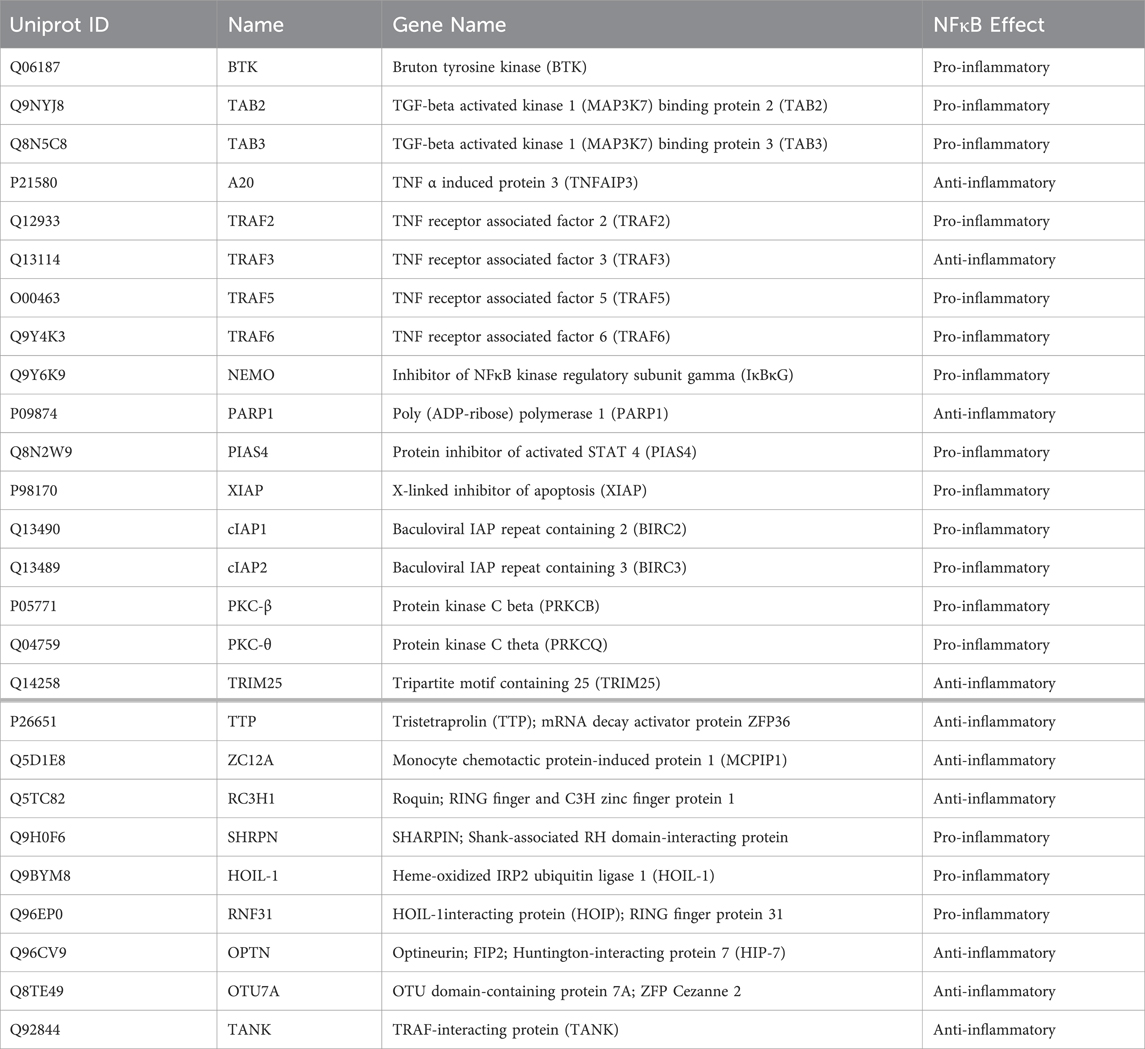

Table 1. Listing of Uniprot-annotated Zinc Finger proteins (ZFs) which are involved in NFκB signaling. ZFs above the bold line were identified in the KEGG analysis in Section 2.1; those below the bold line are included for their roles in NFκB signaling and are discussed in this review.

Of the 17 associated gene hits, 13 are pro-inflammatory in their NFκB function, indicating that the KEGG pathway analysis is limited in its included proteins to early signaling/pathway activation. There are additional NFκB-responsive ZFs that were not identified in the KEGG analysis which are included in Table 1 and are discussed in this review. These proteins include Tristetraprolin (TTP), MCP-1-induced protein-1 (MCPIP1), and Roquin, which negatively regulate the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines produced by NFκB activation (Fu and Blackshear, 2017; Makita et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2012). Ubiquitin-editing ZFs are also included, such as the anti-inflammatory mediators optineurin (OPTN) and OTU domain-containing protein 7A (OTU7A), as well as the pro-inflammatory ZFs SHARPIN, HOIL-1L, and HOIP. The latter three form the linear ubiquitination chain assembly complex (LUBAC) (Fennell et al., 2018; Tokunaga et al., 2011) which catalyzes many forms of protein ubiquitination, enabling protein-protein interactions (PPIs) required for NFκB activation. M1-linked linear polyubiquitination (LUBAC) and K63-linked ubiquitination (LUBAC and others) are forms of ubiquitination that are unique to canonical NFκB activation (Sun, 2017; Tao et al., 2022). Eight other ZFs in the list from Table 1 have ubiquitin E3 ligase activity, demonstrating the essentiality of this PTM, and ZFs, in NFκB signaling.

All of the ZF gene hits from the DAVID analysis, along with the additional ZFs described above, are included in this holistic review that focuses on the importance of ZFs in NFκB signaling and related pathways (i.e., apoptosis, cancer, etc.).

3.2 Activation of pathway signaling

The tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors (TRAFs) are a family of ZFs that act as early transducers of NFκB signaling. All members contain multiple CCCC ZF domains and one RING finger domain which connects various stimulated receptors (for example, TNFRs and toll-like receptors, TLRs) with their respective adaptor complexes (TRADD and MyD88, respectively) (Shi and Sun, 2018). In TLR initiation, activated MyD88 forms a complex with and activates IRAK1/2, which is recognized by TRAF6 (Figure 5). The RING finger domains of TRAF6 function as E3 ligases, in tandem with the E2 complex Uev1A:Ubc13, to catalyze the K63-linked ubiquitination of TRAF6 and other substrates (Xie, 2013). K63-linked TRAF6 is recognized by the ZF complex of TGF-beta activated kinase 1 (TAK1) through its subunits of TAK1-binding proteins 2 and 3 (TAB2/3), both containing a single RanBP2 (CCCC-type) ZF which recognizes K63-linked ubiquitin (Park, 2018). This complex is then recognized by NFκB-essential modulator (NEMO) through NEMO’s lone CCHC ZF domain on the N-terminus (Maubach et al., 2017). Interaction of NEMO with the ubiquitinated upstream elements activates the IκBα kinase complex (IKK), which leads to phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα by IKK, and nuclear translocation of the p50/p65 NFκB complex.

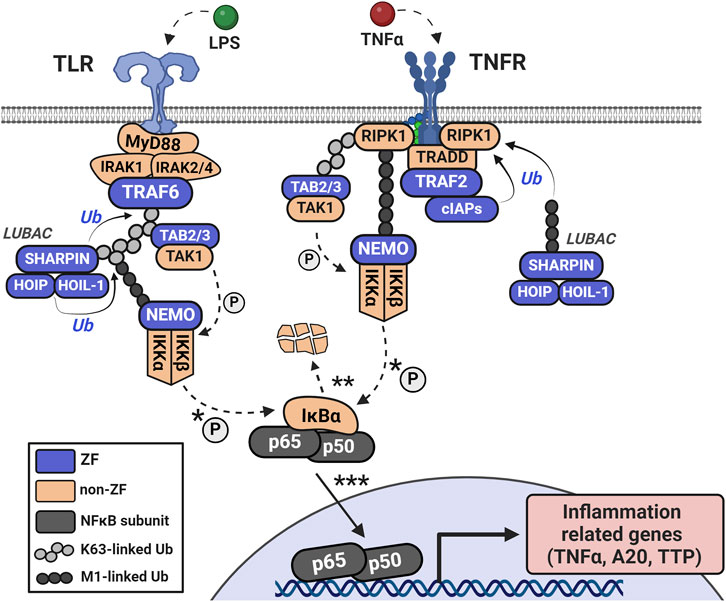

Figure 5. Upon TLR activation, the MyD88 adaptor complex forms with IRAK1/2 and TRAF6. In TNF-mediated NFκB signaling, TNFR recruits an adaptor complex of TRADD, TRAF2, RIP1, and cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP1 and cIAP2). The IAP ZFs have K63-ubiquitin ligase activity and modify RIP1. Ubiquitination of RIP1 or TRAF6 auto-ubiquitination signals recognition by the RanBP2 ZFs of TAB2/3 which specifically recognize K63-linked ubiquitin. The K63-linkages create a scaffold for interaction with the LUBAC complex (SHARPIN, HOIP, and HOIL-1 each having Ubiquitin-associating domains) and recognition by the N-terminal CCHC ZF domain of NEMO. M1-linked ubiquitination via LUBAC supplements K63-linked ubiquitination, functioning similarly to stabilize substrates. The interaction of NEMO with these ubiquitinated elements activates the IKK complex, which phosphorylates and degrades IκBα, leading to the nuclear translocation of the p50/p65 NFκB complex.

For TNF-mediated activation of NFκB signaling, TNFR forms a signaling complex with TNF receptor-associated death domain (TRADD), TRAF2 or TRAF5, receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIP1), and the cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP1 and cIAP2) (Shi and Sun, 2018) (Figure 5). The IAP family are ZFs with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity which ubiquitinate RIP1 and recruit LUBAC (Gyrd-Hansen and Meier, 2010). LUBAC is comprised of 3 ZFs: SHANK-associated RH domain-interacting protein (SHARPIN), heme-oxidized iron regulatory protein ubiquitin ligase (HOIL-1), and HOIL-1 interacting protein (HOIP) (Fuseya and Iwai, 2021; Kasirer-Friede et al., 2019). Both HOIL-1 and HOIP have an arrangement of the following ZF domains: RING1, In-Between-RING (IBR), and RING2; these domains confer the E3 ubiquitin ligase functionality. LUBAC’s subunits also have domains that promote and stabilize their trimeric association, such as the ubiquitin-associating domain of HOIP and the ubiquitin-like domains of HOIL-1 and SHARPIN. LUBAC can uniquely conjugate linear ubiquitin to substrates via the Met1 residue of free ubiquitin; this serves as an additional scaffold for NEMO and others to recognize which is distinct from the branched chains of K63-ubiquitination (Fuseya and Iwai, 2021; Tokunaga et al., 2011).

In both TNFR-mediated or TLR-mediated activation, ubiquitin serves as both a scaffold to relay the signal from receptor to effector (NFκB complex) and to catalyze the degradation of the NFκB inhibitor (IκBα). IKK-mediated degradation of IκBα, and subsequent liberation of p50 and p65 (canonical NFκB subunits) for transcriptional activity, occurs within minutes, leading to a rapid transcriptional activation of NFκB-associated genes (Beg and Baldwin, 1993; Chen et al., 1995). Elevated levels of cytokine mRNAs (e.g., TNFα, interleukins, etc.) are efficiently translated into proteins, acting as positive feedback of this pathway, as RNA-regulatory ZFs, such as tristetraprolin (TTP), are not yet fully responsive (Rappl et al., 2021). Expressed cytokines and chemokines can also participate in crosstalk with adjacent cells, tissues, etc. This pro-inflammatotory signaling is required to activate the immune system and/or combat invading pathogens.

3.3 Regulation of pro-inflammatory stimuli

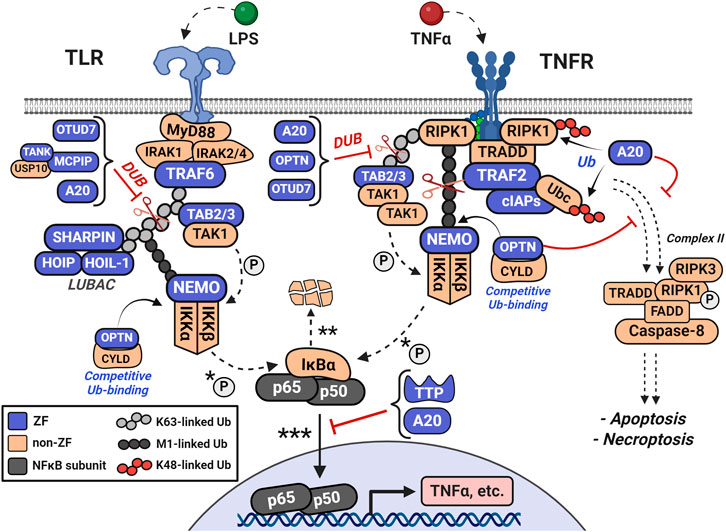

It is important that levels of pro-inflammatory stimuli are controlled by repressors of the pathway, which are also induced by NFκB, to dampen signaling. As shown in Figure 6, one subset of anti-inflammatory mediators are the ubiquitin-editing proteins, including TNFα-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP-3, A20). A20 is a CCCC-type ZF which is rapidly upregulated to act as both a deubiquitinase (DUB) of M1 and K63-ubiquitin linkages and an E3 ligase of K48-ubiquitin linkages (Mooney and Sahingur, 2021; Priem et al., 2020). A20 recognizes many forms of ubiquitinated proteins and disrupts multiple pathway transducers by inhibiting their interactions through ubiquitin. Additionally, it can conjugate K48-ubiquitin chains to early pathway inducers, degrading the substrate, further disrupting the pro-inflammatory signal (Verstrepen et al., 2010). A20 has seven CCCC-type ZF domains, where ZF 4 confers the K48-linked ubiquitin ligase activity and ZF 7 is crucial for polyubiquitin recognition and deubiquitination (Priem et al., 2020). A20 quickly functions to disassemble the ubiquitin frameworks that are the structural basis for continued signaling.

Figure 6. Ubiquitin-editing proteins disrupt NFκB signaling by inhibiting pro-inflammatory interactions among ubiquitinated proteins and by degrading pro-inflammatory mediators via K48-ubiquitination. A20 is rapidly upregulated and acts as both a deubiquitinase (DUB) for M1 and K63-ubiquitin linkages (i.e., of LUBAC and NEMO) and as an E3 ligase for K48-ubiquitin linkages (i.e., RIPK1 and Ubc). Additional ubiquitin-associated proteins include Optineurin (OPTN), OTUD7, and Cylindromatosis (CYLD). OPTN shares high sequence homology with NEMO and competes for M1-and K63-linked polyubiquitin. CYLD, OTUD7, and MCPIP also contribute to ubiquitin-related regulation of the pathway. Together, these ubiquitin-editing enzymes counteract the actions of the cIAP and TRAF families, LUBAC, and NEMO in regulating ubiquitination.

Additional ubiquitin-associated proteins are the ZFs Optineurin (OPTN) and OTUD7, as well as the non-ZFs Cylindromatosis (CYLD), and OTULIN (Fennell et al., 2018). OPTN’s C-terminal UBAN and CCHC ZF domains are required for interaction with ubiquitin-like structures, including linear polyubiquitin and CYLD (Guo et al., 2020). OPTN and NEMO have high sequence homology and signal the NFκB pathway antagonistically through their competition for both linear and K63-linked polyubiquitin (Qiu et al., 2022; Slowicka and van Loo, 2018). CYLD and OTULIN negatively regulate NFκB activity through recognition and de-ubiquitination of polyubiquitinated substrates, including the TRAFs and HOIP (Fennell et al., 2018; Shi and Sun, 2018; Xie, 2013). Collectively, these ubiquitin-editing enzymes regulate ubiquitination antagonistically to NEMO, the LUBAC complex, and the TRAF family.

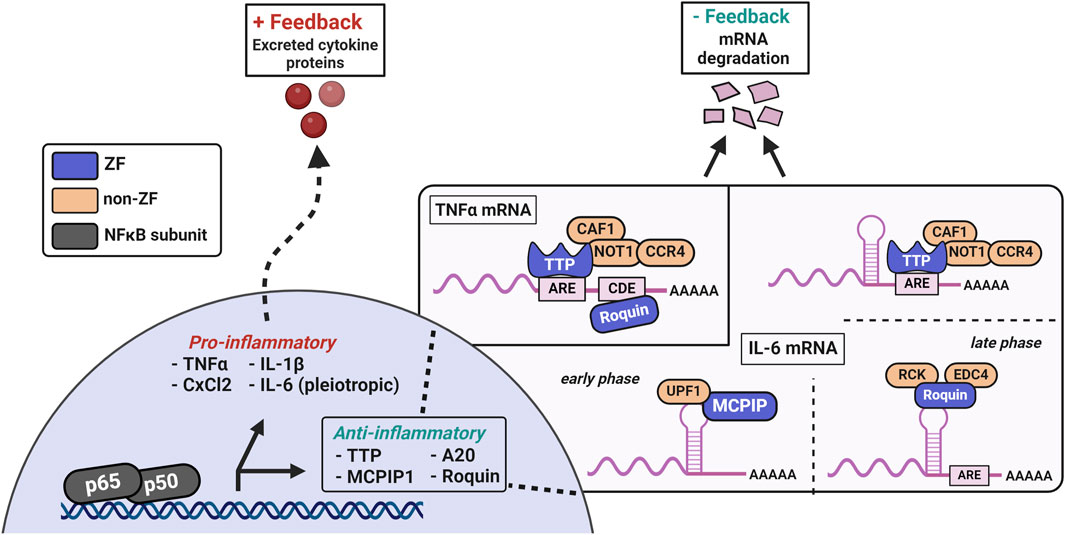

While the DUBs act to prevent further NFκB translocation and activation, RNA-binding ZFs are induced to respond to the NFκB-dependent mRNAs (Behrens and Heissmeyer, 2022; Maeda and Akira, 2017) (Figure 7). TTP and others regulate the positive feedback of cytokine mRNAs by limiting their translation into mature proteins which are capable of further stimulating NFκB-related receptors (ex: TNFα and various interleukins). These RNA-binding ZFs recognize and bind specific ribonucleotide sequences, destabilizing the mRNAs for translation, and ultimately leading to their degradation (Hudson et al., 2004; Kedar et al., 2012; Lai et al., 2000). The complete resolution of these cytokines to basal levels can take upwards of 4 h, depending on the initial concentration and identity of the stimuli (e.g., LPS, TNFα, etc.) (Mulvey et al., 2021).

Figure 7. TTP, MCPIP, and Roquin are induced by NFkB transcriptional activity and negatively regulate excessive pro-inflammatory mediators. MCPIP1 has a single CCCH ZF domain for mRNA recognition, paired with an adjacent PIN RNase domain for mRNA degradation. TTP features two tandem CCCH ZFs that are crucial for recognizing AU-rich sequences in the 3′-UTR of mRNAs. TTP’s ZFs are also necessary for localization to the nucleus and mRNA-processing bodies. The degradation of cytokine mRNAs by TTP involves a conserved C-terminal domain that recruits the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex to the TTP-bound mRNA. Additional modes of TNFα and IL-6 mRNAs regulation are evident in Roquin, which recognizes conserved stem-loop structures and the constitutive decay element (CDE) in cytokine mRNAs. Roquin’s binding recruits the EDC4 and RCK proteins for deadenylation, an event which destabilizes mRNAs and leads to their degradation in the cases of regulation by TTP and Roquin.

TTP, MCPIP, and Roquin are CCCH-type ZFs which negatively regulate excessive pro-inflammatory mRNAs and are essential for proper immune function (Maeda and Akira, 2017; Makita et al., 2021; Rappl et al., 2021). TTP contains two CCCH ZF domains which are required for specific recognition of AU-rich sequences in the 3′-UTR of mRNAs (Hudson et al., 2004). TTP’s ZFs are also necessary for localization to the nucleus and mRNA-processing bodies (Lai et al., 2000). Degradation of cytokine mRNAs requires an evolutionarily conserved C-terminal domain which recruits the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex to TTP-bound mRNA (Fabian et al., 2013). In addition to mRNA destabilization, TTP disrupts NFκB nuclear translocation and participates in alternative splicing in innate immunity (Gu et al., 2013; Schichl et al., 2009; Tu et al., 2020). In canonical NFκB signaling, TTP is one of the main anti-inflammatory mediators due to its simultaneous regulation of thousands of ARE-containing mRNAs (Brooks and Blackshear, 2013; Rappl et al., 2021; Tiedje et al., 2016).

MCPIP1, has an N-terminal ubiquitin-associated domain, a single CCCH ZF domain for mRNA recognition, and an adjacent PIN-like RNase domain for mRNA degradation (Fu and Blackshear, 2017). MCPIP can regulate the NFκB pathway by deubiquitination of TRAF complexes, via its ubiquitin-associated domain, and by degrading cytokine mRNAs, with its inherent endonuclease activity from the adjacent ZF-RNase domains (Xu et al., 2012). Roquin contains two different ZFs: one CCCH domain adjacent to a ROQ domain and one RING ZF domain. The CCCH ZF and ROQ domains are required for mRNA target recognition and recruitment of the decapping complex of mRNA-decapping protein 4 (EDC4) and RCK. The RING ZF is proposed to be important for E3-ubiquitin ligase activity and stress granule association (Zhang et al., 2015). Roquin recognizes conserved stem-loop elements in cytokine mRNAs, such as TNFα, which are spatially distinct from the ARE’s regulated by TTP and represent an overlap in regulation (Maeda and Akira, 2017). MCPIP1 and Roquin also interact in a way that affects the autoregulation of their own mRNAs (Behrens et al., 2021). In addition to the autoregulation of mcpip1 mRNA by MCPIP1, ttp mRNA has multiple ARE elements in its 3′-UTR, which serve as regulatory sites for TTP-mediated degradation. Collectively, these CCCH ZFs are induced by NFκB activation and disrupt the positive feedback loop through degradation of cytokine mRNAs. At some point in the resolution process, activity of these RNA-binding ZFs decreases, and downregulation of their levels restores pathway homeostasis.

4 Post-translational modifications of ZFs in NFκB signaling

4.1 Phosphorylation

ZFs are signaled via PTMs of the ZF domain, or adjacent motifs in the full-length sequence, which affects overall protein function and cell signaling (Fennell et al., 2018; Vignane and Filipovic, 2023; Vilas et al., 2018). In the NFκB pathway, phosphorylation of Ser or Thr residues signals through several ZFs, fine-tuning their activity for a regulated inflammatory response. ZF kinases such as the TAB family (TAB, subunits of TAK1) and protein kinase C family (PKC), in addition to the Ca(II)-mobilizing ZF bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), phosphorylate key substrate proteins to facilitate the early NFκB signal (Altman and Kong, 2014; Kramer et al., 2023; Newton, 2018). For example, the upstream kinases phosphorylate and activate the IKK complex, which then phosphorylates IκBα, leading to ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα, liberating NFκB to translocate to the nucleus (Beg et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1995). Phosphorylation of TTP by MAPK kinases (e.g., MK-2) at S60 and S186 inhibits TTP function via recruitment of the 14-3-3 adaptor complex, permitting the transient increase of cytokine mRNAs during the early inflammatory response (Sandler and Stoecklin, 2008; Tiedje et al., 2014). TTP is then dephosphorylated by PP2A, which directly competes with the 14-3-3 complex, releasing TTP for mRNA regulation.

4.2 Ubiquitination

Another common PTM communicated through ZFs in the NFκB pathway is ubiquitination, which occurs in at least three distinct forms, namely, K48, K63, and M1-linked ubiquitination (Maubach et al., 2017). K48-linked ubiquitination of proteins signals them for degradation via the proteasome. This PTM of IκBα is required to de-repress NFκB and allow for nuclear translocation (Beg and Baldwin, 1993; Beg et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1995). K48-linked ubiquitination is also used by A20, the IAPs, and the TRAFs to regulate early signaling complexes. In contrast, K63-linked ubiquitin and the linearly linked M1-ubiquitin stabilize their substrates and signal as structural scaffolding for downstream interactions of co-activators (i.e., NEMO and SHARPIN) or co-repressors (i.e., TRAF6 and A20) (Fuseya and Iwai, 2021; Kasirer-Friede et al., 2019). In total, the variety of ubiquitination is intertwined with ZF regulation of the NFκB signaling, particularly the RING ZF E3 ligase domains.

4.3 Redox-associated PTMs, cysteine abundance, and persulfidation

Much like phosphorylation and ubiquitination, cysteine-specific PTMs play a role in modifying protein activity during inflammatory signaling, particularly for cysteine-rich ZFs (Chantzoura et al., 2010; Kukulage et al., 2022; Oppong et al., 2023). Human proteins have the highest abundance of cysteines relative to other life forms, and ZF motifs are particularly enriched in their cysteine content (Wiedemann et al., 2020) (See Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). Cysteine residues can be oxidized to disulfides, and while Zn(II) binding to these cysteine residues decreases the susceptibility of cysteine oxidation, such redox changes can occur affecting ZF integrity and function during stress (Doka et al., 2020; Hartle et al., 2016; Kimura, 2015; Kumar and Banerjee, 2021). Adequate redox balance through cellular glutathione and other redox mediators is essential for mitigating oxidative damage to ZFs and other metalloproteins (Fukuto et al., 2020). One cysteine-specific PTM is persulfidation (Cys-SH to Cys-SSH), which modulates protein function and protects the cysteine thiols from oxidation during oxidative stress (Chantzoura et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2023).

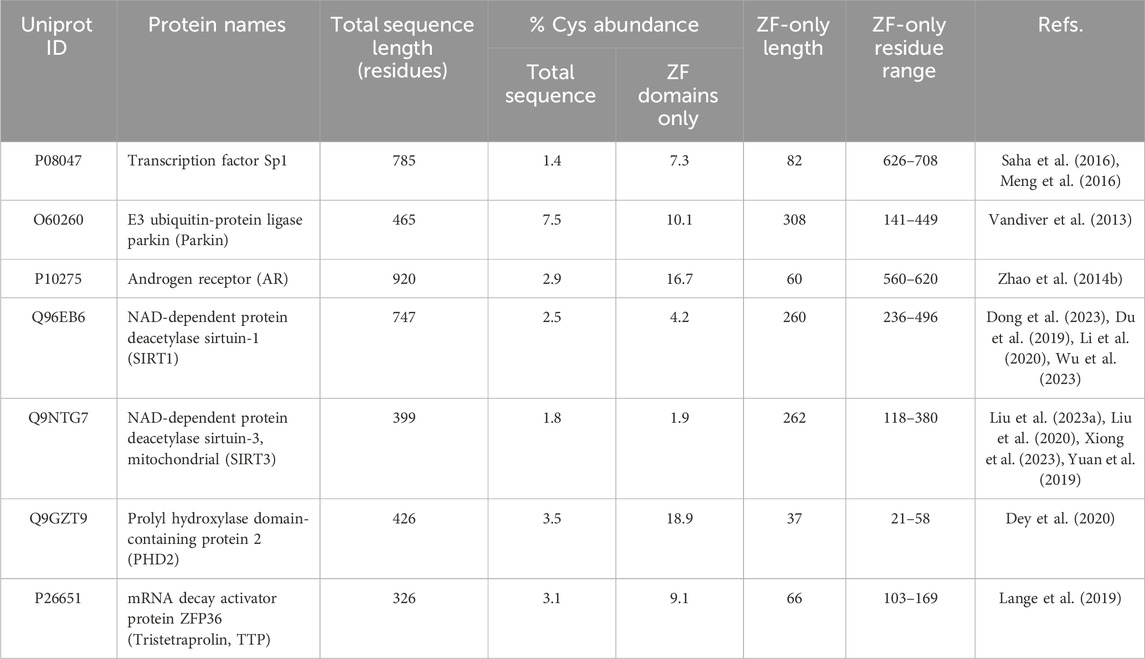

Table 2. ZF-persulfides (ZF-SSHs) examples from literature and their Cys abundance as a function of their full sequence and the sequence excerpt from the beginning of ZF 1 to the end of any additional ZFs in the given protein.

Persulfidation is mediated through the gaseous signaling molecule, hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Cystathionine-gamma-lyase (CSE), cystathionine-beta-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) are the main H2S synthase enzymes. These enzymes constitute the transsulfuration pathway governing the homeostasis of H2S and related sulfur-containing small molecules (Kimura, 2015; Vignane and Filipovic, 2023). H2S can directly form persulfides via reaction with oxidized cysteine residues (disulfides and sulfenic acids) as well with as the Cys-S-Zn sites of ZFs (Cuevasanta et al., 2015; Lange et al., 2019). Protein-persulfides can also be formed co-translationally with cysteinyl-tRNA synthetases (CARS) which functions cooperatively with the transsulfuration pathway, particularly during oxidative stress (Akaike et al., 2017; Sawa et al., 2020). Persulfidation impacts protein structure and can enhance or inhibit activity depending on the specific Cys residue that is modified. As such, the ‘signaling’ property of H2S can be described as modulating regulators and their function. ZFs are directly and indirectly affected by protein persulfidation. Directly, protein stability and activity are altered in the emerging examples of ZF persulfidation (Saha et al., 2016; Vandiver et al., 2013). ZFs are also indirectly induced by persulfidation of other proteins, such as p65 and MEK1, which both contribute to downstream upregulation of PARP-1 and other NFκB-associated ZFs (Dai et al., 2019; Sen et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2014a).

5 ZF persulfidation and functional implications

5.1 ZF-persulfide studies to date

Our laboratory previously reported that the persulfidation of the tandem CCCH ZF domains of TTP leads to disruption of the protein’s structure and obviates TTP/RNA-binding (Lange et al., 2019). TTP-2D reacts with H2S when Zn(II) is bound to the protein and O2 is present. Cryo-electrospray-ionization Mass Spectrometry identified the persulfidated ZF. This method along with orthogonal techniques led to the identification of sulfur- and oxygen-based radicals formed during the persulfidation reaction. A mechanism whereby Zn(II) acts as a conduit for electron transfer between H2S and O2, activating O2 to form superoxide and other reactive species, leading to eventual disulfide formation and Zn(II) ejection was proposed. Cell experiments showed that MEF cells harvested from both WT and ΔCSE mice have similar basal levels of TTP; CSE contributes the majority of protein persulfidation in cells (Filipovic et al., 2018; Paul and Snyder, 2015). Thus, absence of persulfidation did not greatly affect TTP protein stability/abundance, as has been shown in some other examples of ZF-persulfides (Kalous et al., 2021; Saha et al., 2016; Vandiver et al., 2013). TNFα mRNA levels were decreased in the CSE knockout cells, connecting in vitro findings that persulfidation of TTP restricts its RNA binding activity. This loss of structure and function due to TTP persulfidation appears to be a regulatory mechanism for its activity, with H2S serving to “signal” mRNA processing.

We subsequently reported that persulfidation of ZFs is a common PTM. Analysis of persulfide specific proteomics data in multiple mammalian cell lines led to the identification of a large number of persulfidated ZFs. These include ZFs with different ligand sets and regulatory functions (e.g., transcription, translation, ubiquitination, etc.) (Li et al., 2024; Stoltzfus et al., 2024). The finding that ZFs with various ligand sets are persulfidated led us to investigate whether the chemistry that drives persulfidation is affected by ligand set. Using the TTP ZF peptide scaffold as the starting point, a series of mutants that offer one, two, three or four cysteine ligands per ZF domain were prepared and their reactivity with H2S evaluated. In all cases, the TTP ZF peptides were persulfidated by H2S, as long as Zn(II) was bound and O2 was present. These findings suggest a common chemistry amongst ZFs for persulfidation.

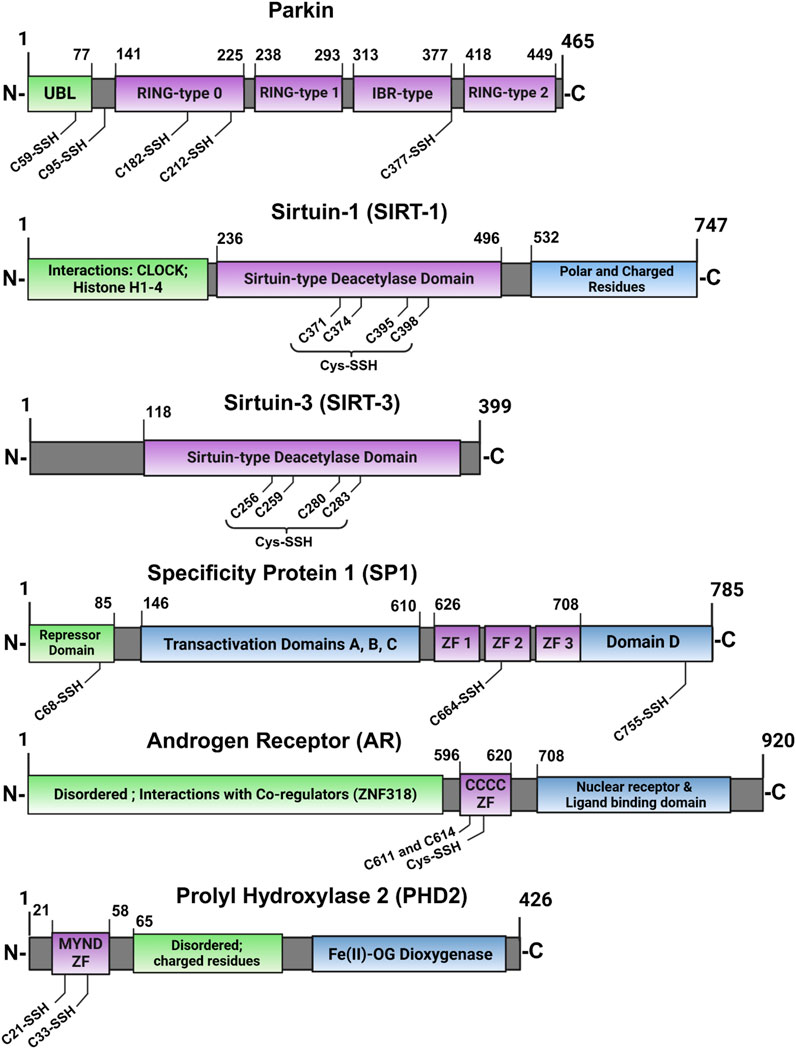

In addition to these proteomics data, there are scattered reports of isolated ZF-persulfides, shown in Figure 8, the earliest of which is Parkin (Vandiver et al., 2013). Parkin contains multiple RING ZF domains which confer E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. This study demonstrated functional activation of Parkin by persulfidation. Parkin was found to be physiologically persulfidated in healthy tissues but depleted in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients and mice models, indicating the loss of Parkin persulfidation and activity as a pathogenic mechanism for sporadic Parkinson’s disease. A slow-releasing H2S-donor (GYY4137) improved Parkin-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of target protein, AIMP2, improving cell viability. As Parkin contains four ZF domains of various classes, this early work highlights the nuance of ZF persulfidation and the need for site-specific determination to consider the full protein sequence and the functional implications of persulfidation. The authors determined the specific residues of Parkin which are persulfidated using mammalian transfection, mutations of Parkin Cys residues, and mass spectrometry. Five Cys residues were determined to be persulfidated but modification of the catalytic C678, involved in ubiquitin transfer, was not observed, suggesting an allosteric effect on Parkin activity by persulfidation of the RING-type 0 (C182 and C212) and IBR-type (C377) ZF domains (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Cartoon depiction of ZFs for which persulfidation was identified for specific residues. Table 2 compiles this list of studied ZF-SSHs along with their Uniprot accession IDs and their percentage of Cys content based on their sequences (purple = ZF domain).

The classical ZF, SP1 (CCHH domain) has also been reported to be persulfidated. SPI acts as a transcriptional activator or repressor of GC-rich gene promoters (Beishline and Azizkhan-Clifford, 2015; Kaczynski et al., 2003; Vizcaino et al., 2015; Yin and Wang, 2021). SP1 was found to be upregulated during NFκB pathway stimulation by TNFα, leading to increased H2S production and persulfidation through SP1-mediated transcriptional activation of CSE (Sen et al., 2012). More recently, Saha and coworkers showed that SP1 is itself persulfidated, dependent on functional CBS, leading to enhanced transcription of VEGF-1 by SP1 (Saha et al., 2016). The authors again used an MS/MS technique to show that persulfidation of SP1 at C68 and C755 are necessary for optimal transcriptional activity in the maintenance of endothelial cell function. Although the persulfidated residues are outside of the ZF domains of SP1, they play a role in stabilizing the protein, resulting in higher SP1 protein levels, leading to optimal binding of its transcriptional elements. As CBS converts homocysteine to H2S in the transsulfuration pathway, knockdown of CBS led to hyperhomocysteinemia and a reduction in H2S and GSH levels (Miles and Kraus, 2004). Furthermore, SP1 had decreased binding to the VEGFR-2 promoter and endothelial cells displayed a phenotype with compromised chemotaxis. All outcomes were ameliorated by treatment with H2S, but not glutathione, demonstrating the importance of SP1 persulfidation mediated by proper CBS activity.

The MYND-type ZF (CCCC-CCHC) prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing protein 2 (PHD2) constitutively hydroxylates HIF-1α leading to ubiquitination and degradation (Dey et al., 2020; Maxwell et al., 1999). Hypoxic conditions lead to inhibition of PHD2 activity, stabilization of HIF-1α, complexation with HIF-1beta, and transcription of hypoxia-related survival genes. Dey and coworkers discovered that PHD2 is persulfidated at C21 and C33 residues of its MYND-type ZF domain (Figure 8), leading to enhanced hydroxylation of HIF-1α by PHD2 (Dey et al., 2020). Disruption of CBS in zebrafish lead to abnormal development, diminished persulfidation of PHD2, and stabilized HIF-1α. All phenotypes were rescued by H2S supplementation. These data support a role for persulfidation in healthy endothelial cell development.

The sirtuin family of ZFs has also been shown to be persulfidated (Kalous et al., 2021). This ZF family features a singular, conserved CCCC-type ZF domain that provides a structural element to deacetylate histones and activate transcription of stress-response genes. The SIRT1 and SIRT3 proteins have been shown to undergo persulfidation during various types of cell stress. Persulfidation improves SIRT1 protein levels in the cell by increasing Zn-binding affinity and reducing ubiquitination, both of which lead to enhanced protein stability and deacetylase activity (Dong et al., 2023; Du et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2023). Similar observations have been made for SIRT3, localized in the mitochondria (Liu F. et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2019). Liu et al. established that persulfidation is essential for optimal SIRT3 activity in two ways: first, by the direct stabilization and activation of SIRT3 by persulfidation, and second by the indirect upregulation of SIRT3 transcription by Nrf-2, which is also indirectly activated by persulfidation of Keap1 (Liu et al., 2020). This Nrf-2/Keap1/SIRT3 persulfidation axis is perturbed during conditions of oxidative stress and can be rescued by exogenous NaHS supplementation. For both SIRT1 and SIRT3, the cumulative evidence highlights a role for ZF persulfidation leading to enhanced deacetylation activity, which is an essential factor for increased antioxidant gene expression by the sirtuin ZF family.

In contrast to the ZF-persulfides discussed so far, which have enhanced protein activity, there are also examples of protein inactivation by persulfidation, such as TTP-2D and androgen receptor (AR). Zhao and coworkers focused on AR, a CCCC type ZF that functions as a transcriptional activator of androgen-responsive gene elements, in androgen-resistance and the development of prostate cancer (Zhao et al., 2014b). They found that CSE expression was diminished in human prostate cancer tissue and androgen-resistant cell lines, suggesting a possible deficiency in H2S-associated signaling in this disease state. CSE overexpression repressed the expression of AR-target genes and remediated pathogenic phenotypes in mice models. They also found that mutation of the ZF domains of AR at C611 and C614 abrogated the rescue potential of CSE overexpression, indicating that persulfidation of these residues is required for regulation of AR via inhibition of AR dimerization and gene transcription.

5.2 Structure/function implications of ZF-SSH case studies

The broader biological prevalence and significance of ZF persulfidation have not been fully appreciated and reviewed. To connect the signaling role of H2S and persulfidation of Cys-rich ZFs, it is necessary to consider the local environment and location of specific residues found to be persulfidated. Of the six ZF-SSHs listed in Section 5.1 which were studied in cell (Parkin, SP1, PHD2, SIRT1, SIRT3, and AR), five ZFs had enhanced activity with persulfidation, as well as ameliorative effects in cells and tissue. What’s left to unravel are the connections between modified Cys residues and the fate of overall protein activity, although the commonality is activation by persulfidation. This may prove helpful in screening and characterizing potentially pathogenic mutations which lead to some loss-of-function due to diminished protein persulfidation.

One example is Parkin which was found to be persulfidated but to a diminished degree in Parkinson’s patients. Only three of five Cys mutants could be expressed and functionally assessed by iteratively mutating these residues from Cys to Ser. The three mutants (C59, C95, and C182) that were assessed are integral to the auto-regulatory inhibition of Parkin in its inactive, basal state. This suggests that persulfidation of these residues may contribute to the “opening” and activation of Parkin, as seen in the well-studied phosphorylation of Parkin by PINK1 (Barazzuol et al., 2020). Persulfidation of these residues likely does not directly enhance Parkin’s catalytic activity (as catalytic C678 was not modified), but rather it contributes to a greater pool of active Parkin and indirectly increases the ubiquitation of substrates.

As described in Section 5.1, SP1 persulfidation at C68 and C755 enhances its binding and transcriptional activation of VEGF (Saha et al., 2016). Separately, persulfidation of the second ZF domain at C664 is required for SP1-mediated inhibition of Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) expression (Meng G. et al., 2016). These two cases illustrate that further characterization and partner/target binding studies are required for novel ZF-SSHs. Persulfidation of certain residues might enhance interactions with either a corepressing or a coactivating protein, depending on factors of the local environment such as surface accessibility. Further in-depth studies of ZF-SSHs can utilize the approaches from these examples and expand our basis of knowledge concerning the signals of persulfidation through ZFs.

5.3 Looking forward

A powerful tool in cell and animal models are persulfide-specific proteomic approaches which can determine enriched signaling pathways and new ZF-SSHs of interest. There are several persulfide-labeling approaches for proteomic identification (Li et al., 2024) and many can be used to corroborate protein-persulfides with non-reducing gel electrophoretic methods of labeled cell lysates. These labeling methods may be applied to other methods of visualization, such as microscopy and flow cytometry, to inform on cellular localization (Zivanovic et al., 2019).

As presented by the case studies mentioned here, experiments which identify residue-specific Cys persulfidation (i.e., mass spectrometry and/or protein mutation) are essential for ZF-SSHs. Furthermore, mapping these modifications to reported protein structures can aid in understanding the structural and functional consequences of ZF persulfidation. In cell, applying the techniques cited in Section 5.1 to newly identified ZF-SSHs will be helpful in uncovering the broader implications of ZF persulfidation and H2S signaling. Identified ZF-SSHs can be tested for site-specific persulfidation, which requires mammalian cell transfection, overexpression, and Cys-SSH identification by MS techniques. The cell systems are then utilized to iteratively mutate identified Cys residues and determine the functional fidelity of mutants (ex: Parkin-C182S). Additionally, knockout mice models can broadly (or specifically) reduce persulfidation and provide information about which H2S-generating enzymes contribute to the ZF-SSH of interest. By knocking out or inhibiting any of CSE, CBS, 3-MST, or CARS, direct connections between an enzyme and a ZF’s persulfidation can be elucidated. Similarly, biochemical studies on isolated ZF proteins and peptides, to further characterize persulfidation sites and determine the effects of persulfidation on protein activity will further broaden our understanding of ZF protein persulfidation and the role of H2S.

6 Potential therapies for chronic NFκB-associated syndromes

Dysfunction of NFκB signaling and ZFs is associated with metabolic syndromes, inflammation, cancer, and age-related diseases (Beishline and Azizkhan-Clifford, 2015; Bu et al., 2021; Hosea et al., 2023). Dysregulation of the transsulfuration pathway and protein persulfidation is likewise associated with these chronic conditions (Filipovic et al., 2018; Kabil and Banerjee, 2014). Antibody therapies targeting TNF and these associated pathologies are a large proportion of FDA-approved biologic therapies and are often conjugated with synthetic compounds, such as cytotoxins for cancer combination therapies, for multimodal effects (Lewis Phillips et al., 2008; Tiwari et al., 2016). In lieu of reviewing the intricacy of engineered antibodies, we refer readers to some excellent reviews (Leone et al., 2023; Mitoma et al., 2018; Morita et al., 2022; Shepard et al., 2017). In addition to the NFκB pathologies, ZFs and H2S are known to contribute to proper cardiovascular function (Meng et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2014; Pikkarainen et al., 2004); more recent examples, such as the SIRT ZFs (see Section 5) demonstrate the necessity of ZFs as conduits for persulfidation and H2S signaling. Much of the work to date connect persulfidation with perturbed NFκB signaling and excessive cytokine levels, suggesting that NFκB pathway is a molecular throughfare for ZF and H2S regulation. As more isolated ZF persulfides are characterized, it will become clearer as to how H2S-associated physiological effects are intertwined with ZF function/dysfunction.

Therapeutic efforts related to ZFs and sulfur homeostasis have been studied in several contexts, including gene editing therapies using artificial ZF domains and sulfur donating molecules which seek to restore imbalanced cellular small molecules.

6.1 ZF nucleases

While ZFs are now understood as ubiquitous regulators of transcription and translation, interest in gene editing precedes their discovery (Helene and Toulme, 1990; Kawasaki et al., 1996). ZFs have been studied for their potential in gene editing therapy due to their innate function of oligonucleotide binding. This specificity of binding is tunable for different targets (Bibikova et al., 2001; Kawasaki et al., 1996). ZF nucleases (ZFNs) are chimeric constructs containing multiple ZF domains for recognition of target genes, where each domain recognizes a triplet of nucleotide bases, fused with a nuclease domain (Porteus and Baltimore, 2003). The small recognition patterns provide ZFNs an advantage over other endonucleases, as the fingers can be modularly designed to increase sequence specificity (Hauschild-Quintern et al., 2013). ZFNs have been implemented in human and other mammalian cells, but translation to animal models and human clinical trials is still developing (Jabalameli et al., 2015).

The first human clinical trial using ZFNs was conducted in 2022 to treat mucopolysaccharidosis (n=12) and hemophilia B (n=1) (Harmatz et al., 2022). The authors found adequate safety and tolerance at all tested doses with evidence for successful gene editing and enhanced enzyme expression in liver tissues. However, the hemophilia B subject could not be assessed for gene-editing, and no long-term enzyme expression was observed in any patients. RNA-binding CCCH ZFs, such as MCPIP, are also in development as a potential ZFN design strategy for chronically elevated cytokines which may be disrupted by the stability and translational efficiency of their mRNA (Gaj et al., 2012; Garg et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Paschon et al., 2019). Ultimately, the long-term efficacy of ZFN treatment, as seen in the clinical trial, needs improvement.

6.2 Sulfur donors

Glutathione and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) have been popularized as antioxidant supplements in sports medicine and elsewhere, presumably acting by replenishing a depleted sulfur pool (Fernández-Lázaro et al., 2023). Dick and coworkers recently showed that the beneficial effects of NAC are due in part to endogenous H2S production from the provided Cys (Ezerina et al., 2018). As a result of increased H2S concentrations, persulfide species, including GSSH, were increased. Sulfane sulfur and persulfides have garnered increased interest over the last decade due to the ability of the former to store sulfur and generate various forms of protein- and small molecule-persulfides, which are associated with a multitude of positive biological outcomes in cell and animal studies (Dai et al., 2019; Doka et al., 2016; Donnarumma et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2019; Zivanovic et al., 2019). The highly reactive nature of a persulfide makes it a better radical scavenger than other cellular thiols but also presents an obstacle to therapy as it may react before reaching its target (Filipovic et al., 2018; Fukuto et al., 2020). To overcome this, efforts have been made to create persulfide donor prodrugs which activate upon reaction with specific stimuli, such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and photons (Bora et al., 2018; Chaudhuri et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Other groups are dissecting the chemical reactivity of persulfides based on their local chemical environment, adding to both our fundamental understandings of protein persulfides and the tunable stability of persulfide-related therapies (Fosnacht et al., 2024). These therapeutic methods may restore ZF-SSH function and more broadly aid in biomarker discovery of diseases characterized by chronic inflammation.

7 Conclusion

Zn(II) and ZFs play a major role in the NFκB pathway, which responds to various stimuli for development, immunity, pathogen defense, cell death, etc. (van Loo and Bertrand, 2023). Although the types of ZF families, ligands, and functional partners are broad, all ZFs share the characteristic of binding Zn(II) in a tetrahedral coordination geometry to form a folded domain which is then functional. We are now learning these folded ZF domains can be modified via chemical transformations that affect protein function and offer a new layer of regulation. The transformation of cysteine into cysteine-persulfide, mediated by the gasotransmitter H2S, imparts numerous advantages for the fidelity of ZFs. On the molecular level, protein-persulfides have greater metal affinity and nucleophilicity than their thiol counterparts (Lau and Pluth, 2019). Furthermore, they are reversibly oxidized during stress and can be recovered by cellular reductants. In a broader context, persulfidation and H2S are ameliorative in models of chronic inflammation, such as cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and immune diseases (Liu M. H. et al., 2023; Salti et al., 2024). ZFs regulate pathways related to these diseases and represent a sizeable superfamily of protein domains that are suitable messengers for H2S-related signaling. Persulfide specific proteomics data are uncovering multiple ZFs that are persulfidated. These findings open the door for experiments to decipher how persulfidation affects both specific ZFs and ZF rich signalling pathways. The understanding gained in these areas has the potential to inform on the development of new therapies for diseases impacted by aberrant sulfur homeostasis and ZF function.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. SLJM is grateful to the NIH (R01GM139854) for support of this work.

Acknowledgments

Figures 1, and 4–8 were created using Biorender. Figures 1 and 3 were created using ChimeraX.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchbi.2024.1503390/full#supplementary-material

References

Akaike, T., Ida, T., Wei, F. Y., Nishida, M., Kumagai, Y., Alam, M. M., et al. (2017). Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase governs cysteine polysulfidation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1177. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01311-y

Altman, A., and Kong, K. F. (2014). Protein kinase C inhibitors for immune disorders. Drug Discov. Today 19 (8), 1217–1221. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.05.008

Andreini, C., Banci, L., Bertini, I., and Rosato, A. (2006a). Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J. Proteome. Res. 5 (1), 196–201. doi:10.1021/pr050361j

Andreini, C., Banci, L., Bertini, I., and Rosato, A. (2006b). Zinc through the three domains of life. J. Proteome Res. 5 (11), 3173–3178. doi:10.1021/pr0603699

Barazzuol, L., Giamogante, F., Brini, M., and Cali, T. (2020). PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy, Ca(2+) signalling, and ER-mitochondria contacts in Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (5), 1772. doi:10.3390/ijms21051772

Beg, A. A., and Baldwin, A. S. (1993). The I kappa B proteins: multifunctional regulators of Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factors. Genes Dev. 7 (11), 2064–2070. doi:10.1101/gad.7.11.2064

Beg, A. A., Finco, T. S., Nantermet, P. V., and Baldwin, A. S. (1993). Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of I kappa B alpha: a mechanism for NF-kappa B activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 (6), 3301–3310. doi:10.1128/mcb.13.6.3301

Behrens, G., Edelmann, S. L., Raj, T., Kronbeck, N., Monecke, T., Davydova, E., et al. (2021). Disrupting Roquin-1 interaction with Regnase-1 induces autoimmunity and enhances antitumor responses. Nat. Immunol. 22 (12), 1563–1576. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-01064-3

Behrens, G., and Heissmeyer, V. (2022). Cooperation of RNA-binding proteins - a focus on Roquin function in T cells. Front. Immunol. 13, 839762. article #839762. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.839762

Beishline, K., and Azizkhan-Clifford, J. (2015). Sp1 and the 'hallmarks of cancer. FEBS J. 282 (2), 224–258. doi:10.1111/febs.13148

Berg, J. M. (1986). Potential metal-binding domains in nucleic acid binding proteins. Science 232 (4749), 485–487. doi:10.1126/science.2421409

Bertini, I., Decaria, L., and Rosato, A. (2010). The annotation of full zinc proteomes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 15 (7), 1071–1078. doi:10.1007/s00775-010-0666-6

Besold, A. N., Lee, S. J., Michel, S. L. J., Lue Sue, N., and Cymet, H. J. (2010). Functional characterization of iron-substituted neural zinc finger factor 1: metal and DNA binding. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 15 (4), 583–590. doi:10.1007/s00775-010-0626-1

Bibikova, M., Carroll, D., Segal, D. J., Trautman, J. K., Smith, J., Kim, Y. G., et al. (2001). Stimulation of homologous recombination through targeted cleavage by chimeric nucleases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 (1), 289–297. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.1.289-297.2001

Bora, P., Chauhan, P., Manna, S., and Chakrapani, H. (2018). A vinyl-boronate ester-based persulfide donor controllable by hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species (ROS). Org. Lett. 20 (24), 7916–7920. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03471

Brooks, S. A., and Blackshear, P. J. (2013). Tristetraprolin (TTP): interactions with mRNA and proteins, and current thoughts on mechanisms of action. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 1829 (6-7), 666–679. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.003

Bu, S., Lv, Y., Liu, Y., Qiao, S., and Wang, H. (2021). Zinc finger proteins in neuro-related diseases progression. Front. Neurosci. 15, 760567. article #760567. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.760567

Cassandri, M., Smirnov, A., Novelli, F., Pitolli, C., Agostini, M., Malewicz, M., et al. (2017). Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov. 3, 17071. article #17071. doi:10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.71

Chabert, V., Lebrun, V., Lebrun, C., Latour, J. M., and Seneque, O. (2019). Model peptide for anti-sigma factor domain HHCC zinc fingers: high reactivity toward 1O2 leads to domain unfolding. Chem. Sci. 10 (12), 3608–3615. doi:10.1039/c9sc00341j

Chantzoura, E., Prinarakis, E., Panagopoulos, D., Mosialos, G., and Spyrou, G. (2010). Glutaredoxin-1 regulates TRAF6 activation and the IL-1 receptor/TLR4 signalling. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 403 (3-4), 335–339. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.029

Chaudhuri, A., Venkatesh, Y., Das, J., Gangopadhyay, M., Maiti, T. K., and Singh, N. D. P. (2019). One- and two-photon-activated cysteine persulfide donors for biological targeting. J. Org. Chem. 84 (18), 11441–11449. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b01224

Checconi, P., Limongi, D., Baldelli, S., Ciriolo, M. R., Nencioni, L., and Palamara, A. T. (2019). Role of glutathionylation in infection and inflammation. Nutrients 11 (8), 1952. article #1952. doi:10.3390/nu11081952

Chen, Z., Hagler, J., Palombella, V. J., Melandri, F., Scherer, D., Ballard, D., et al. (1995). Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets I kappa B alpha to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 9 (13), 1586–1597. doi:10.1101/gad.9.13.1586

Coleman, J. E. (1998). Zinc enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2 (2), 222–234. doi:10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80064-1

Cuevasanta, E., Lange, M., Bonanata, J., Coitino, E. L., Ferrer-Sueta, G., Filipovic, M. R., et al. (2015). Reaction of hydrogen sulfide with disulfide and sulfenic acid to form the strongly nucleophilic persulfide. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (45), 26866–26880. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.672816

Dai, L., Qian, Y., Zhou, J., Zhu, C., Jin, L., and Li, S. (2019). Hydrogen sulfide inhibited L-type calcium channels (CaV1.2) via up-regulation of the channel sulfhydration in vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 858, 172455. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172455

Dey, A., Prabhudesai, S., Zhang, Y., Rao, G., Thirugnanam, K., Hossen, M. N., et al. (2020). Cystathione β-synthase regulates HIF-1α stability through persulfidation of PHD2. Sci. Adv. 6 (27), eaaz8534. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz8534

Doka, E., Ida, T., Dagnell, M., Abiko, Y., Luong, N. C., Balog, N., et al. (2020). Control of protein function through oxidation and reduction of persulfidated states. Sci. Adv. 6 (1), eaax8358. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax8358

Doka, E., Pader, I., Biro, A., Johansson, K., Cheng, Q., Ballago, K., et al. (2016). A novel persulfide detection method reveals protein persulfide- and polysulfide-reducing functions of thioredoxin and glutathione systems. Sci. Adv. 2 (1), e1500968. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500968

Dong, B., Sun, Y., Cheng, B., Xue, Y., Li, W., and Sun, X. (2023). Activating transcription factor (ATF) 6 upregulates cystathionine β synthetase (CBS) expression and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) synthesis to ameliorate liver metabolic damage. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28 (1), 540. doi:10.1186/s40001-023-01520-w

Donnarumma, E., Trivedi, R. K., and Lefer, D. J. (2017). Protective actions of H2S in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Compr. Physiol. 7 (2), 583–602. doi:10.1002/cphy.c160023

Du, C., Lin, X., Xu, W., Zheng, F., Cai, J., Yang, J., et al. (2019). Sulfhydrated sirtuin-1 increasing its deacetylation activity is an essential epigenetics mechanism of anti-atherogenesis by hydrogen sulfide. Antioxidants and Redox Signal. 30 (2), 184–197. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7195

Dyer, R. R., Ford, K. I., and Robinson, R. A. S. (2019). The roles of S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation in Alzheimer's disease. Methods Enzym. 626, 499–538. doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2019.08.004

Ezerina, D., Takano, Y., Hanaoka, K., Urano, Y., and Dick, T. P. (2018). N-Acetyl cysteine functions as a fast-acting antioxidant by triggering intracellular H2S and sulfane sulfur production. Cell Chem. Biol. 25 (4), 447–459.e4. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.01.011

Fabian, M. R., Frank, F., Rouya, C., Siddiqui, N., Lai, W. S., Karetnikov, A., et al. (2013). Structural basis for the recruitment of the human CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex by tristetraprolin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20 (6), 735–739. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2572

Fennell, L. M., Rahighi, S., and Ikeda, F. (2018). Linear ubiquitin chain-binding domains. FEBS J. 285 (15), 2746–2761. doi:10.1111/febs.14478

Fernández-Lázaro, D., Domínguez-Ortega, C., Busto, N., Santamaría-Peláez, M., Roche, E., Gutiérez-Abejón, E., et al. (2023). Influence of N-Acetylcysteine supplementation on physical performance and laboratory biomarkers in adult males: a systematic review of controlled trials. Nutrients 15 (11), 2463. doi:10.3390/nu15112463

Filipovic, M. R., Zivanovic, J., Alvarez, B., and Banerjee, R. (2018). Chemical biology of H2S signaling through persulfidation. Chem. Rev. 118 (3), 1253–1337. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00205

Fosnacht, K. G., Sharma, J., Champagne, P. A., and Pluth, M. D. (2024). Transpersulfidation or H2S release? Understanding the landscape of persulfide chemical biology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146 (27), 18689–18698. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c05874

Foster, M. P., Wuttke, D. S., Radhakrishnan, I., Case, D. A., Gottesfeld, J. M., and Wright, P. E. (1997). Domain packing and dynamics in the DNA complex of the N-terminal zinc fingers of TFIIIA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 (8), 605–608. doi:10.1038/nsb0897-605

Fu, M., and Blackshear, P. J. (2017). RNA-binding proteins in immune regulation: a focus on CCCH zinc finger proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17 (2), 130–143. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.129

Fukuto, J. M., Vega, V. S., Works, C., and Lin, J. (2020). The chemical biology of hydrogen sulfide and related hydropersulfides: interactions with biologically relevant metals and metalloproteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 55, 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.11.013

Fuseya, Y., and Iwai, K. (2021). Biochemistry, pathophysiology, and regulation of linear ubiquitination: intricate regulation by coordinated functions of the associated ligase and deubiquitinase. Cells 10 (10), 2706. doi:10.3390/cells10102706

Gaj, T., Guo, J., Kato, Y., Sirk, S. J., and Barbas, C. F. (2012). Targeted gene knockout by direct delivery of zinc-finger nuclease proteins. Nat. Methods 9 (8), 805–807. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2030

Garg, A., Roske, Y., Yamada, S., Uehata, T., Takeuchi, O., and Heinemann, U. (2021). PIN and CCCH Zn-finger domains coordinate RNA targeting in ZC3H12 family endoribonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (9), 5369–5381. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab316

Garrido Ruiz, D., Sandoval-Perez, A., Rangarajan, A. V., Gunderson, E. L., and Jacobson, M. P. (2022). Cysteine oxidation in proteins: structure, biophysics, and simulation. Biochemistry 61 (20), 2165–2176. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00349

Go, Y. M., Chandler, J. D., and Jones, D. P. (2015). The cysteine proteome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 84, 227–245. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.022

Gu, L., Ning, H., Qian, X., Huang, Q., Hou, R., Almourani, R., et al. (2013). Suppression of IL-12 production by tristetraprolin through blocking NF-кB nuclear translocation. J. Immunol. 191 (7), 3922–3930. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300126

Guo, J., Wang, H., Jiang, S., Xia, J., and Jin, S. (2017). The cross-talk between Tristetraprolin and cytokines in cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 17 (11), 1477–1486. doi:10.2174/1871520617666170327155124

Guo, Q., Wang, J., and Weng, Q. (2020). The diverse role of optineurin in pathogenesis of disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 180, 114157. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114157

Gyrd-Hansen, M., and Meier, P. (2010). IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10 (8), 561–574. doi:10.1038/nrc2889

Harmatz, P., Prada, C. E., Burton, B. K., Lau, H., Kessler, C. M., Cao, L., et al. (2022). First-in-human in vivo genome editing via AAV-zinc-finger nucleases for mucopolysaccharidosis I/II and hemophilia B. Mol. Ther. 30 (12), 3587–3600. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.10.010

Hartle, M. D., Delgado, M., Gilbertson, J. D., and Pluth, M. D. (2016). Stabilization of a Zn(II) hydrosulfido complex utilizing a hydrogen-bond accepting ligand. Chem. Commun. 52 (49), 7680–7682. doi:10.1039/c6cc01373b

Hauschild-Quintern, J., Petersen, B., Cost, G. J., and Niemann, H. (2013). Gene knockout and knockin by zinc-finger nucleases: current status and perspectives. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70 (16), 2969–2983. doi:10.1007/s00018-012-1204-1

Helene, C., and Toulme, J. J. (1990). Specific regulation of gene expression by antisense, sense and antigene nucleic acids. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Struct. Expr. 1049 (2), 99–125. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(90)90031-v

Hierons, S. J., Marsh, J. S., Wu, D., Blindauer, C. A., and Stewart, A. J. (2021). The interplay between non-esterified fatty acids and plasma zinc and its influence on thrombotic risk in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (18), 10140. article #10140. doi:10.3390/ijms221810140

Hosea, R., Hillary, S., Wu, S., and Kasim, V. (2023). Targeting transcription factor YY1 for cancer treatment: current strategies and future directions. Cancers (Basel) 15 (13), 3506. doi:10.3390/cancers15133506

Hudson, B. P., Martinez-Yamout, M. A., Dyson, H. J., and Wright, P. E. (2004). Recognition of the mRNA AU-rich element by the zinc finger domain of TIS11d. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 (3), 257–264. doi:10.1038/nsmb738

Jabalameli, H. R., Zahednasab, H., Karimi-Moghaddam, A., and Jabalameli, M. R. (2015). Zinc finger nuclease technology: advances and obstacles in modelling and treating genetic disorders. Gene 558 (1), 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.044

Jarosz, M., Olbert, M., Wyszogrodzka, G., Mlyniec, K., and Librowski, T. (2017). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of zinc. Zinc-dependent NF-κB signaling. Inflammopharmacology 25 (1), 11–24. doi:10.1007/s10787-017-0309-4

Jomova, K., Makova, M., Alomar, S. Y., Alwasel, S. H., Nepovimova, E., Kuca, K., et al. (2022). Essential metals in health and disease. Chemico-Biological Interact. 367, 110173. article #110173. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110173

Kabil, O., and Banerjee, R. (2014). Enzymology of H2S biogenesis, decay and signaling. Antioxidants and Redox Signal. 20 (5), 770–782. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5339

Kaczynski, J., Cook, T., and Urrutia, R. (2003). Sp1-and Kruppel-like transcription factors. Genome Biol. 4 (2), 206. doi:10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-206

Kalous, K. S., Wynia-Smith, S. L., and Smith, B. C. (2021). Sirtuin oxidative post-translational modifications. Front. Physiol. 12, 763417. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.763417

Kanehisa, M., and Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.27

Kang, E., Seo, J., Yoon, H., and Cho, S. (2021). The post-translational regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-inducing transcription factors in cancer metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (7), 3591. doi:10.3390/ijms22073591

Kasirer-Friede, A., Tjahjono, W., Eto, K., and Shattil, S. J. (2019). SHARPIN at the nexus of integrin, immune, and inflammatory signaling in human platelets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (11), 4983–4988. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819156116

Kawasaki, H., Machida, M., Komatsu, M., Li, H. O., Murata, T., Tsutsui, H., et al. (1996). Specific regulation of gene expression by antisense nucleic acids: a summary of methodologies and associated problems. Artif. Organs 20 (8), 836–848. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1594.1996.tb04556.x

Kedar, V. P., Zucconi, B. E., Wilson, G. M., and Blackshear, P. J. (2012). Direct binding of specific AUF1 isoforms to tandem zinc finger domains of tristetraprolin (TTP) family proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 287 (8), 5459–5471. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.312652

Kimura, H. (2015). Signaling molecules: hydrogen sulfide and polysulfide. Antioxidants and Redox Signal. 22 (5), 362–376. doi:10.1089/ars.2014.5869

Kluska, K., Adamczyk, J., and Krezel, A. (2018). Metal binding properties of zinc fingers with a naturally altered metal binding site. Metallomics 10 (2), 248–263. doi:10.1039/c7mt00256d

Kramer, J., Bar-Or, A., Turner, T. J., and Wiendl, H. (2023). Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 19 (5), 289–304. doi:10.1038/s41582-023-00800-7

Kukulage, D. S. K., Matarage Don, N. N. J., and Ahn, Y. H. (2022). Emerging chemistry and biology in protein glutathionylation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 71, 102221. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2022.102221

Kumar, R., and Banerjee, R. (2021). Regulation of the redox metabolome and thiol proteome by hydrogen sulfide. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 56 (3), 221–235. doi:10.1080/10409238.2021.1893641

Lai, W. S., Carballo, E., Thorn, J. M., Kennington, E. A., and Blackshear, P. J. (2000). Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (23), 17827–17837. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001696200

Lange, M., Ok, K., Shimberg, G. D., Bursac, B., Marko, L., Ivanovic-Burmazovic, I., et al. (2019). Direct zinc finger protein persulfidation by H2S is facilitated by Zn2+. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (24), 7997–8001. doi:10.1002/anie.201900823

Lau, N., and Pluth, M. D. (2019). Reactive sulfur species (RSS): persulfides, polysulfides, potential, and problems. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 49, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.08.012

Lee, S. J., and Michel, S. L. J. (2014). Structural metal sites in nonclassical zinc finger proteins involved in transcriptional and translational regulation. Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (8), 2643–2650. doi:10.1021/ar500182d

Leone, G. M., Mangano, K., Petralia, M. C., Nicoletti, F., and Fagone, P. (2023). Past, present and (foreseeable) future of biological anti-TNF alpha therapy. J. Clin. Med. 12 (4), 1630. doi:10.3390/jcm12041630

Lewis Phillips, G. D., Li, G., Dugger, D. L., Crocker, L. M., Parsons, K. L., Mai, E., et al. (2008). Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. 68 (22), 9280–9290. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776

Li, H., Stoltzfus, A. T., and Michel, S. L. J. (2024). Mining proteomes for zinc finger persulfidation. RSC Chem. Biol. 5 (6), 572–585. doi:10.1039/d3cb00106g

Li, J., Li, M., Wang, C., Zhang, S., Gao, Q., Wang, L., et al. (2020). NaSH increases SIRT1 activity and autophagy flux through sulfhydration to protect SH-SY5Y cells induced by MPP. Cell Cycle 19 (17), 2216–2225.doi:10.1080/15384101.2020.1804179

Lipkowitz, S., and Weissman, A. M. (2011). RINGs of good and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour suppression and oncogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11 (9), 629–643. doi:10.1038/nrc3120

Liu, B., Huang, J., Ashraf, A., Rahaman, O., Lou, J., Wang, L., et al. (2021). The RNase MCPIP3 promotes skin inflammation by orchestrating myeloid cytokine response. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 4105. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24352-w

Liu, F., Yuan, L., Li, L., Yang, J., Liu, J., Chen, Y., et al. (2023a). S-sulfhydration of SIRT3 combats BMSC senescence and ameliorates osteoporosis via stabilizing heterochromatic and mitochondrial homeostasis. Pharmacol. Res. 192, 106788. article #106788. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106788

Liu, M. H., Lin, X. L., and Xiao, L. L. (2023b). Hydrogen sulfide attenuates TMAO-induced macrophage inflammation through increased SIRT1 sulfhydration. Mol. Med. Rep. 28 (1), 129. doi:10.3892/mmr.2023.13016

Liu, Z., Wang, X., Li, L., Wei, G., and Zhao, M. (2020). Hydrogen sulfide protects against paraquat-induced acute liver injury in rats by regulating oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and inflammation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 1–16. doi:10.1155/2020/6325378

Lo, M. N., Damon, L. J., Wei Tay, J., Jia, S., and Palmer, A. E. (2020). Single cell analysis reveals multiple requirements for zinc in the mammalian cell cycle. Elife 9, e51107. article #51107. doi:10.7554/eLife.51107

Louis, J. M., Agarwal, A., Aduri, R., and Talukdar, I. (2021). Global analysis of RNA–protein interactions in TNF-α induced alternative splicing in metabolic disorders. FEBS Lett. 595 (4), 476–490. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.14029

Lu, X., Chen, Q., Liu, H., and Zhang, X. (2021). Interplay between non-canonical NF-κB signaling and hepatitis B virus infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 730684. article #730684. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.730684

Luo, S., Kong, C., Zhao, S., Tang, X., Wang, Y., Zhou, X., et al. (2023). Endothelial HDAC1-ZEB2-NuRD complex drives aortic aneurysm and dissection through regulation of protein S-Sulfhydration. Circulation 147 (18), 1382–1403. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062743

Maeda, K., and Akira, S. (2017). Regulation of mRNA stability by CCCH-type zinc-finger proteins in immune cells. Int. Immunol. 29 (4), 149–155. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxx015

Makita, S., Takatori, H., and Nakajima, H. (2021). Post-transcriptional regulation of immune responses and inflammatory diseases by RNA-binding ZFP36 family proteins. Front. Immunol. 12, 711633. article #711633. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.711633

Maubach, G., Schmadicke, A. C., and Naumann, M. (2017). NEMO links nuclear factor-κb to human diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 23 (12), 1138–1155. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2017.10.004

Maxwell, P. H., Wiesener, M. S., Chang, G. W., Clifford, S. C., Vaux, E. C., Cockman, M. E., et al. (1999). The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399 (6733), 271–275. doi:10.1038/20459

Meng, G., Ma, Y., Xie, L., Ferro, A., and Ji, Y. (2015). Emerging role of hydrogen sulfide in hypertension and related cardiovascular diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172 (23), 5501–5511. doi:10.1111/bph.12900

Meng, G., Xiao, Y., Ma, Y., Tang, X., Xie, L., Liu, J., et al. (2016). Hydrogen sulfide regulates krüppel-like factor 5 transcription activity via specificity protein 1 S-sulfhydration at Cys664 to prevent myocardial hypertrophy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 (9), e004160. article #e004160. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004160

Michalek, J. L., Besold, A. N., and Michel, S. L. J. (2011). Cysteine and histidine shuffling: mixing and matching cysteine and histidine residues in zinc finger proteins to afford different folds and function. Dalton Trans. 40 (47), 12619–12632. doi:10.1039/c1dt11071c

Miles, E. W., and Kraus, J. P. (2004). Cystathionine β-synthase: structure, function, regulation, and location of homocystinuria-causing mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (29), 29871–29874. doi:10.1074/jbc.R400005200

Miller, J., Mclachlan, A. D., and Klug, A. (1985). Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 4 (6), 1609–1614. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03825.x

Mitoma, H., Horiuchi, T., Tsukamoto, H., and Ueda, N. (2018). Molecular mechanisms of action of anti-TNF-α agents – comparison among therapeutic TNF-α antagonists. Cytokine 101, 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.014

Mooney, E. C., and Sahingur, S. E. (2021). The ubiquitin system and A20: implications in health and disease. J. Dent. Res. 100 (1), 10–20. doi:10.1177/0022034520949486

Morita, H., Matsumoto, K., and Saito, H. (2022). Biologics for allergic and immunologic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 150 (4), 766–777. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.009

Mulvey, C. M., Breckels, L. M., Crook, O. M., Sanders, D. J., Ribeiro, A. L. R., Geladaki, A., et al. (2021). Spatiotemporal proteomic profiling of the pro-inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide in the THP-1 human leukaemia cell line. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 5773. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26000-9

Negi, S., Imanishi, M., Hamori, M., Kawahara-Nakagawa, Y., Nomura, W., Kishi, K., et al. (2023). The past, present, and future of artificial zinc finger proteins: design strategies and chemical and biological applications. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 28 (3), 249–261. doi:10.1007/s00775-023-01991-6

Newton, A. C. (2018). Protein kinase C as a tumor suppressor. Seminars Cancer Biol. 48, 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.04.017

O'halloran, T. V., and Culotta, V. C. (2000). Metallochaperones, an intracellular shuttle service for metal ions. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (33), 25057–25060. doi:10.1074/jbc.R000006200

Ok, K., Filipovic, M. R., and Michel, S. L. J. (2021). Targeting zinc finger proteins with exogenous metals and molecules: lessons learned from Tristetraprolin, a CCCH type zinc Finger. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021 (37), 3795–3805. doi:10.1002/ejic.202100402

Oppong, D., Schiff, W., Shivamadhu, M. C., and Ahn, Y. H. (2023). Chemistry and biology of enzymes in protein glutathionylation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 75, 102326. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.102326

Padjasek, M., Kocyla, A., Kluska, K., Kerber, O., Tran, J. B., and Krezel, A. (2020). Structural zinc binding sites shaped for greater works: structure-function relations in classical zinc finger, hook and clasp domains. J. Inorg. Biochem. 204, 110955. article #110955. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.110955

Pan, H., Xie, X., Chen, D., Zhang, J., Zhou, Y., and Yang, G. (2014). Protective and biogenesis effects of sodium hydrosulfide on brain mitochondria after cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 741, 74–82. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.037

Park, H. H. (2018). Structure of TRAF Family: current understanding of receptor recognition. Front. Immunol. 9, 1999. article #1999. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01999

Park, J. M., Lee, T. H., and Kang, T. H. (2018). Roles of tristetraprolin in tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (11), 3384. doi:10.3390/ijms19113384

Paschon, D. E., Lussier, S., Wangzor, T., Xia, D. F., Li, P. W., Hinkley, S. J., et al. (2019). Diversifying the structure of zinc finger nucleases for high-precision genome editing. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 1133. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08867-x

Patial, S., and Blackshear, P. J. (2016). Tristetraprolin as a therapeutic target in inflammatory disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 37 (10), 811–821. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.07.002

Paul, B. D., and Snyder, S. H. (2015). H2S: a novel gasotransmitter that signals by sulfhydration. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40 (11), 687–700. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.007