95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Cell. Neurosci. , 19 May 2022

Sec. Cellular Neurophysiology

Volume 16 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2022.889939

This article is part of the Research Topic Role of Metal Ions in Central Nervous System: Physiology and Pathophysiology View all 7 articles

It is commonly accepted that the role of astrocytes exceeds far beyond neuronal scaffold and energy supply. Their unique morphological and functional features have recently brough much attention as it became evident that they play a fundamental role in neurotransmission and interact with synapses. Synaptic transmission is a highly orchestrated process, which triggers local and transient elevations in intracellular Ca2+, a phenomenon with specific temporal and spatial properties. Presynaptic activation of Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclases represents an important mechanism of synaptic transmission modulation. This involves activation of the cAMP-PKA pathway to regulate neurotransmitter synthesis, release and storage, and to increase neuroprotection. This aspect is of paramount importance for the preservation of neuronal survival and functionality in several pathological states occurring with progressive neuronal loss. Hence, the aim of this review is to discuss mutual relationships between cAMP and Ca2+ signaling and emphasize those alterations at the Ca2+/cAMP crosstalk that have been identified in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

The discoveries made three decades ago that cytosolic Ca2+ rise occurs in astrocytes in response to environmental cues have provided new insights into the essential role of these star-shaped glial cells in the CNS. Nowadays, it is commonly known that astrocytes are highly specialized types of glial cells responsible for synapse formation and regulation of ongoing neuronal transmission. They also interact with other glial cells or blood vessels depending on the brain region (Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018). For instance, the astrocytic support is maintained by the release of neurotrophic factors and diverse transmitters called gliotransmitters, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP)/adenosine, D-serine, glutamate, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at various timescales to sustain complex information processing and metabolic homeostasis in the brain (Steeland et al., 2018; Durkee and Araque, 2019; Pöyhönen et al., 2019). It is estimated that the ratio of glial cells to neurons is roughly 1:1 and astrocytes constitute ~19–40% of all glial cells in the CNS (Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018), nevertheless the total number of neurons and glia has long been controversial (von Bartheld et al., 2016).

The morphological and functional heterogeneity of astrocytes determines various protein expression profiles what may explain the sensitivity of certain areas of the brain to the progress of a specific disease entity (Xin and Bonci, 2018; Matias et al., 2019). Moreover, opposed to the neuro-centric view of brain function, astroglia dysfunction is increasingly considered a fundamental cause in the pathogenesis of neurological diseases (Liu et al., 2017; Robertson, 2018).

In contrast to neurons, astrocytes do not fire an action potential. However, in response to the local changes in intracellular Ca2+, often referred to as “Ca2+ excitability,” they can strongly influence physiological and pathophysiological events in the nervous system. Indeed, astrocytes express the diversity of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that allow detection and reaction to neuronal signals (Durkee and Araque, 2019). Among the second messengers activated by GPCRs, Ca2+, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) are capable of eliciting diverse pleiotropic responses, thus regulating basic cellular functions, such as growth and differentiation, gene transcription and protein expression as well as astrocyte-mediated synaptic plasticity, gliotransmission, energy supply and maintenance of the extracellular environment (Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Horvat and Vardjan, 2019; Zhou et al., 2021). It is supposed that dysregulation of Ca2+ and cAMP exacerbates structural and functional abnormalities in this cell type, hence restoration of imbalanced Ca2+ and/or cAMP signaling may constitute an effective astrocyte-based therapeutic approach Growing body of evidence links deficits in astrocytic Ca2+ and cAMP-controlled mechanisms to various brain pathologies (Ujita et al., 2017; Reuschlein et al., 2019; Kofuji and Araque, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Recent technological progress in two-photon imaging and development of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) as well as genetically encoded sensors for cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA), allowed for high-resolution detection of astrocytic Ca2+/cAMP fluxes in different physiological and pathological conditions (Reeves et al., 2011; Gee et al., 2015; Semyanov et al., 2020; Massengill et al., 2021).

Despite this progress, the cause-effect relationship between temporal and spatial disturbances in intracellular Ca2+/cAMP signaling machinery and the development of neuropathological disorders are still being sought. Therefore, this review summarizes the latest findings on the crosstalk between cAMP and Ca2+ signaling pathways and their contribution to the neurodegenerative process.

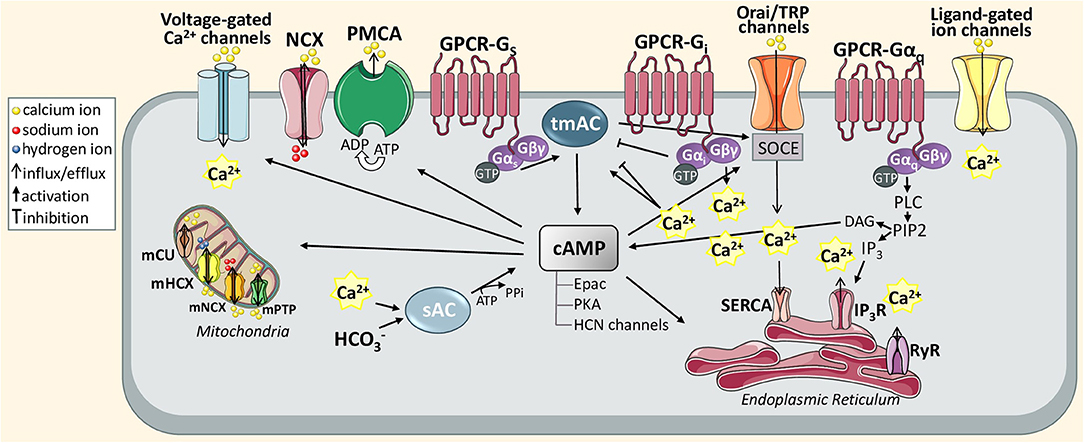

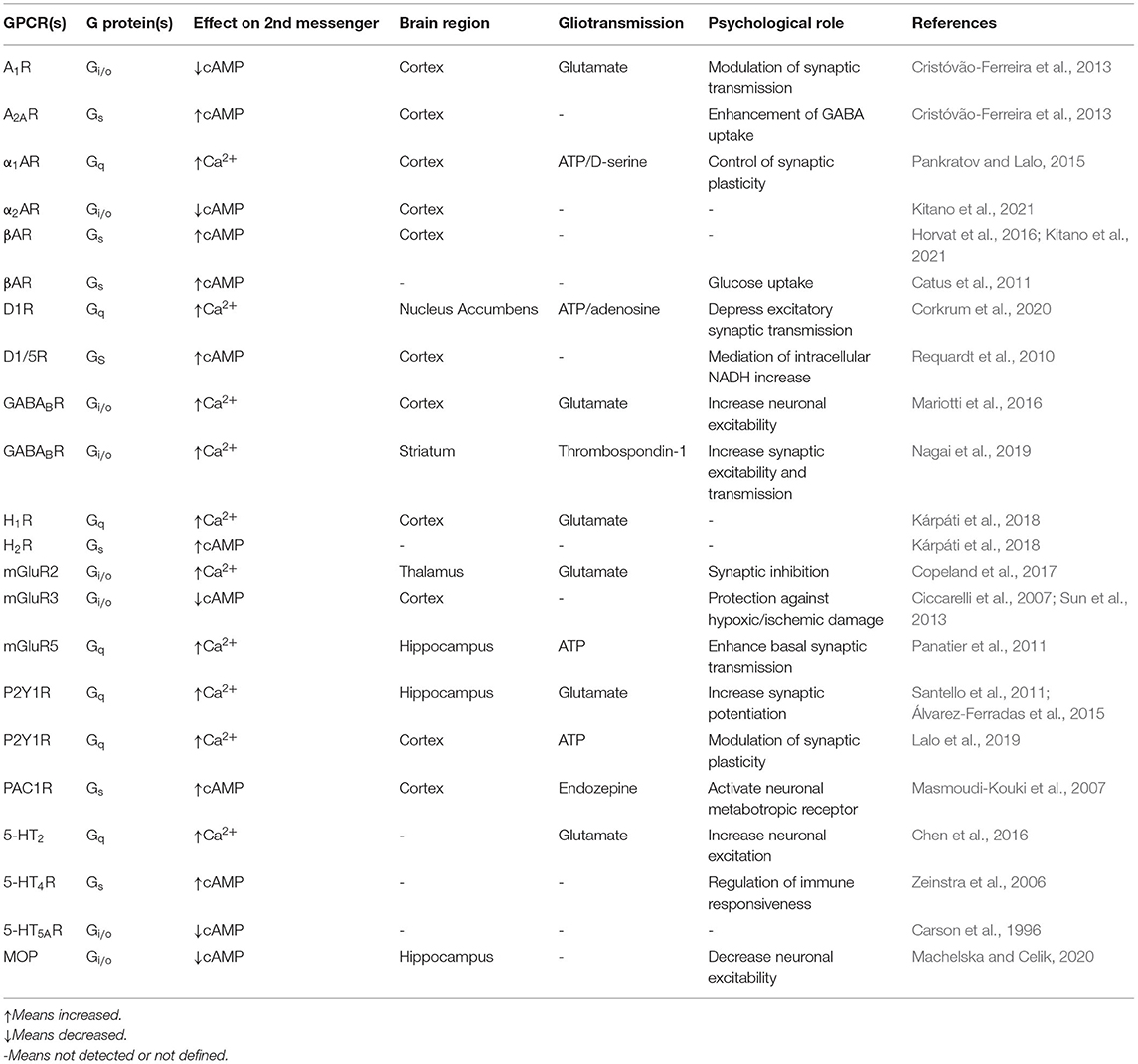

Overall, neuronal information is transferred to astrocytes primarily through spillover of neurotransmitters or other types of neuroligands, which diffuse into the extracellular space and next bind to various astroglial targets, such as membrane ionic channels, transporters or receptors triggering their conformational change (Figure 1). As a result, activated GPCR catalyzes dissociation of a heterotrimeric G protein complex (composed of Gα, Gβ/Gγ subunits) into Gα subunit and βγ dimer by the exchange of GDP for GTP. Based on the sequence homology and functionality of α-subunits, G proteins are divided into four main families: Gαs, Gαi/Gαo, Gαq/Gα11, and Gα12/Gα13 that regulate distinct downstream signaling events (Jastrzebska, 2013). The activation of the Gq subunit stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) that leads to hydrolysis of phosphoinositol diphosphate (PIP2) into diacylglycerol (DAG), known as a membrane-bound regulator of cAMP concentration, and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), known as a soluble messenger triggering the release of Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Hua et al., 2004) or secretory vesicles (Hur et al., 2010). In astrocytes, Gq-coupled receptors, mainly α1-adrenoreceptor (α1-AR; Ding et al., 2013), D1 dopamine receptor (D1R; Corkrum et al., 2020), histamine receptor (H1; Kárpáti et al., 2018), metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR; Sun et al., 2013), serotonin 5-HT2 receptor (Peng and Huang, 2012), and P2Y purinoreceptor (Ding et al., 2009), and also Gi-coupled receptors, such as GABAB receptor (Durkee et al., 2019), generate a wide range of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-dependent Ca2+ oscillations to differently regulate gliotransmission and neuronal modulation (Table 1). For example, synaptically released acetylcholine (ACh) or noradrenaline (NE) can induce an astrocytic Ca2+ increase thereby enhancing synaptic plasticity the in the cortex (Takata et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012) and hippocampus (Navarrete et al., 2012; Papouin et al., 2017). The IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release may also occur spontaneously (King et al., 2020). The canonical function of Gi-GPCR is to suppress adenylate cyclase-dependent signaling cascade and thus, inhibit cAMP activity, which has been also observed in astrocytes (Gould et al., 2014). The Gβγ released from different Gi subunits targets ion channels such as inwardly rectifying potassium channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Jeremic et al., 2021). Interestingly, the GPCR-Gi/o protein signaling in neurons is commonly known to inhibit intracellular Ca2+ events and electrical excitability, whereas a recent study has demonstrated that astrocyte Gi/o GPCR activation may stimulate Ca2+ elevation involved in the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters into the synapse (Huang and Thathiah, 2015; Durkee et al., 2019). Therefore, such functional diversity of GPCRs enables integrated astrocyte-neuron communication.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of astrocytic Ca2+ and cAMP signaling pathways discussed in this review. The action of active GTP-bound Gαi and GTP-bound Gαo stimulates or inhibits transmembrane adenylyl cyclase (tmAC) that produces cAMP. The tmAC may also be controlled indirectly via store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). To maintain Ca2+ homeostasis in the ER, SOCE is orchestrated through the interaction between store-operated plasma membrane calcium channels, called Orai or transient receptor potential (TRP) channel, and can stimulate SERCA pump activity once Ca2+ levels fall below the threshold levels. In particular, this mechanism is generated when Ca2+ stores in the ER are depleted upon activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor via Gαq-phospholipase C (PLC)-IP3 signal transduction pathway. In turn, the DAG produced from PIP2 hydrolysis can also catalyze cAMP synthesis. Another activator of cAMP is Ca2+ sensitive soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC). cAMP itself and cAMP-dependent proteins (Epac PKA, and HCN channels) can differently transmit Ca2+ signals supporting various astrocytic functions including gliotransmission, glycogen metabolism or synaptic homeostasis.

Table 1. Astrocytic Ca2+/cAMP modulation by GPCR receptors and their physiological role in diverse brain areas.

Several interesting results regarding global Ca2+ elevations in astrocytes have been derived from IP3R type 2 knockout mice (Guerra-Gomes et al., 2021). It has been demonstrated that loss of this receptor may contribute to various types of cognitive dysfunctions (Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014; Padmashri et al., 2015) as well as depressive-like behaviors (Cao et al., 2013), but it seems unlikely that its role in shaping astrocytic Ca2+ is predominant (Petravicz et al., 2008, 2014). Although astrocytic IP3R2 expression is required for certain mechanisms of LTD formation, the genetic defects in IP3R2 are not sufficient to fully prevent LTP generation what probably reflects astrocyte diversity in different brain regions (Oberheim et al., 2012). Recently, it has been suggested that IP3R1 and IP3R3 subtypes co-exist in astroglia and retain their functionality by generating local Ca2+ events (Sherwood et al., 2017, 2021). The second key type of Ca2+-permeable receptor channel in the ER is the ryanodine receptor (RyR) but the mechanism of its activation and inhibition by Ca2+ remains largely unexplored and controversial (Rodríguez-Prados et al., 2020; Skowrońska et al., 2020). The latest report has suggested that RyR-mediated Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) in astrocytes may be negatively modulated by neuron-derived factors which may alter the Ca2+ response triggered by ionotropic receptors (Skowrońska et al., 2020). Other types of stores controlling intracellular Ca2+ concentration are mitochondria that buffer cytosolic Ca2+ via the mitochondrial NCX, mitochondrial H+/Ca2+ exchanger (mHCX), mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (mCU), and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP; Agarwal et al., 2017). Interestingly, the expression of some mitochondrial transporters may be controlled by cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB; Shanmughapriya et al., 2015). Primarily, a rise in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration drives energy production needed to modulate glutamate release and prevents excitotoxic neuronal death. On the other hand, Ca2+ overload may lead to astrocytic apoptosis (Stephen et al., 2014). It is worth mentioning that Ca2+ signaling dynamics diffuse between mitochondria and ER (Okubo et al., 2019), and ER stress triggers mitochondrial dysfunction (Britti et al., 2018).

The resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentration independent from IP3-activity is also controlled by transmembrane Ca2+ influx through the transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) channel. Activation of this receptor can induce constitutive D-serine release from astrocytes for NMDA receptor-dependent LTP maintenance (Shigetomi et al., 2013). Blocking of TRPA1 decreases spontaneous Ca2+ events leading to lower extracellular GABA uptake by the astrocyte-specific transporter (GAT3; Shigetomi et al., 2011). In view of that, astrocytic TRPA channels are considered as integral players coordinating Ca2+ dynamics involved in the inhibitory efficacy of the hippocampal synapses. Likewise, intracellular Ca2+ is also tightly regulated by ionotropic receptors, including α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, both gated by glutamate, and ATP-gated purinergic P2X receptors (Palygin et al., 2010, 2011; Ceprian and Fulton, 2019). The plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) are the main regulators of Ca2+ extrusion to the extracellular space while the control of Ca2+ concentration in the ER is ensured by the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) (Brini and Carafoli, 2011). Compared to NCX, PMCA has a lower capacity for ionic transport but its basal affinity for Ca2+ is higher. This property allows PMCA to respond to even subtle changes in Ca2+ concentration within a range of its resting cytosolic level. By contrast, NCX can eliminate significant rises in intracellular Ca2+, although, in the case of increased intracellular Na+ concentration, due to e.g., glutamate or GABA uptake, the NCX may operate in reverse mode increasing Ca2+ influx (Brini and Carafoli, 2011; Rose et al., 2020).

Unlike Ca2+ activity, which can be regulated by multiple distinct pathways, the predominant mechanism of cAMP modulation is mediated by GPCRs coupled to either Gs or Gi leading to activation or inhibition of transmembrane adenylate cyclases (tmACs), respectively. In astrocytes, cAMP is regulated mainly by the activation of adenosine receptors (A1 and A2A), adrenergic receptors (α2 and β1−3), dopamine receptor (D1/5), glutamatergic receptor (mGlu3), histamine receptor (H2), PACAP/VIP receptors, serotonin receptors (5-HT4 and 5-HT5A) and also opioid receptors, all summarized in Table 1. ACs are believed to be pivotal points of integration between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. It is assumed that all of the nine tmAC isoforms, which have also been identified in mice astrocytes (Lee et al., 2018), can be modulated (activated or inhibited) by Ca2+, either directly or indirectly via Ca2+ binding proteins such as calmodulin (CaM), CaM kinase (CaMK), calcineurin (CaN), protein kinase C (PKC), or Gq-coupled receptor activation. For instance, AC8 activated in a Ca2+/CaM-dependent manner binds the Orai1 channel, which is a major functional component responsible for store-operated calcium entry (SOCE; Willoughby et al., 2012a,b). Accordingly, the AC8 seems to be highly sensitive to modest local Ca2+ changes. In primary astrocytic cultures, AC inhibitor 2',5'-dideoxyadenosine prevented cAMP synthesis and significantly decreased SOCE-triggered glycogenolysis. Based on this evidence, the authors proposed a new model for astrocytic coupling of Ca2+ homeostasis, AC8-dependent cAMP production and glycogen metabolism which could also impact on learning and memory processes (Müller et al., 2014). However, the physiological interplay between the molecular players of cAMP signaling and depletion of ER Ca2+ stores still remains to be determined in this subtype of glial cells.

Recent in vitro and in vivo studies provided considerable insight into the differences between Ca2+ and cAMP dynamics in astrocytes in terms of precise spatiotemporal regulation of complex cellular processes (Horvat et al., 2016; Oe et al., 2020). While stimulation of α1AR generated rapid and transient Ca2+ increase enhancing synaptic plasticity, stimulation of βAR triggered slower and long-lasting cAMP elevations and promoted consolidation of cortical memory. It is supposed that threshold levels for activation of respective second messenger are different due to diverse affinities of NE for AR subtypes. According to this, moderate NE release may be sufficient to activate the α1AR coupled to the Gq while activation of βAR coupled to the Gs needs relatively high extracellular NE to elevate cAMP within the cell (Ramos and Arnsten, 2007; Oe et al., 2020). Another type of AC, called soluble AC (sAC), is directly activated by entry via the electrogenic NaHCO3 cotransporter in response to extracellular K+ rises or aglycemia (Choi et al., 2012; Schmid et al., 2014). sAC is also highly expressed in astrocytes to stimulate the production of intracellular cAMP. Elevated cAMP can provide energy supply and metabolic support for the proper functioning of neurons contributing to glycolysis and delivery of lactate from astrocytes (Choi et al., 2012; MacVicar and Choi, 2017). It is worth noting that sAC is found in distinct subcellular microdomains with local cAMP signals (Tresguerres et al., 2011) and even slight changes in the intracellular Ca2+ dynamics may impact the activation of this AC isoform (Gancedo, 2013; Schmid et al., 2014). The fatty acids (Lee et al., 2018), lactate, aspirin (Modi et al., 2013), or some antidepressants (e.g., ketamine or fluoxetin) have been reported to cause the astrocytic cAMP-elevation but their mechanism of action toward second messengers still remains unclear (Kinoshita et al., 2018; Lasič et al., 2019; Stenovec et al., 2020; Stenovec, 2021).

It is commonly known that Ca2+ has multiple downstream targets (Scemes and Giaume, 2006; Bagur and Hajnóczky, 2017). cAMP can transmit Ca2+ signals through isoforms of exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac), Epac1 and Epac2, or PKA or cAMP-gated ion channels called hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels (Halls and Cooper, 2011). cAMP itself or cAMP-dependent proteins may evoke both Ca2+ influx via cation channels (Catterall, 2011) and Ca2+ extrusion by ATP-dependent pumps (Vandecaetsbeek et al., 2011). Phosphorylation of IP3R subtypes seems to be stimulated by PKA or EPAC as well as directly activated by cAMP. This activation requires much higher concentrations of second messengers and is quickly attenuated after removing the AC stimulus (Taylor, 2017). Analysis of acute hippocampal slices has shown that astrocytic cAMP/PKA signaling may modulate oscillatory activity of intracellular Ca2+ (Ujita et al., 2017). In cortical astrocytes, cAMP/PKA-dependent Ca2+ changes may be mediated by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) to maintain the exocytotic secretion of gliotransmitters (Burgos et al., 2007). The cytosolic Ca2+ elevations are necessary for gliotransmission of ATP, serine, and also glutamate to support neuronal plasticity (Harada et al., 2015). In pathological states, the abnormal release of gliosignalling molecules may trigger excitotoxicity and synaptic damage leading to neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative progress (Agulhon et al., 2012; Kawamata et al., 2014).

Both cAMP and cGMP degradation may be driven by a large group of phosphodiesterases (PDEs) classified into 11 families, some of which are regulated by Ca2+ or Ca2+/CaM (Bender and Beavo, 2006; Tenner et al., 2020; Turunen and Koskelainen, 2021). Given that most of tmAC isoforms, PKA and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs), may be located at the scaffold protein complexes called A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), it is plausible that the spatial and temporal organization of AKAPs orchestrates synthesis and degradation of the second messenger at the specific subcellular sites. Although RNA-sequencing of astrocytes purified from mouse brain suggests the presence of genes encoding various AKAP subtypes (e.g., AKAP15/18, AKAP79, gravin, Yotiao; Reuschlein et al., 2019), their functional role in astrocytic cAMP signaling remains to be uncovered. These multi-functional scaffold proteins have been widely characterized in neurons, both in physiological and pathological states (Wild and Dell'Acqua, 2018). The AKAPs associated with cAMP are regulated by local Ca2+ oscillations (Scott and Santana, 2010; Boczek et al., 2021). Global analysis of astroglial transcripts released in 2015 demonstrated that cAMP-dependent signaling regulated 6,221 of 16,594 annotated genes, including 42.1% of them were significantly upregulated whereas the remaining were downregulated by cAMP analogs. As suggested by Gene Ontology enrichment analysis, the upregulated genes were mainly involved in cellular metabolism (e.g., uptake/degradation of catecholamines, glutamate, and glycine) and transport (e.g., Ca2+ or K+ -ion, glucose, or water transport) as well as antioxidant activities, especially glutathione-related defenses. Among genes downregulated by cAMP stimulation, the overwhelming number of encoded modulators of the physiological process as cell cycle, proliferation, or death (e.g., some cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, mitogenic agents, BCL2 family proteins), as well as cytoskeletal proteins and mediators of the immune system. Therefore, cAMP is involved in the regulation of a plethora of cellular functions from the antioxidant systems through the control of the normal state of differentiated astrocytic cells (Paco et al., 2016).

It is apparently becoming clear that the existence of an interplay between cAMP and Ca2+ messenger systems in astrocytes is non-linear and of great complexity. Undoubtedly, spatial and temporal resolution should be taken under consideration to understand their synergistic and antagonistic relationship.

The pathological protein accumulation, such as amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated protein tau are commonly detected hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Neurodegeneration manifested by neuronal integrity loss and white matter lesions or gliosis, is widely recognized in postmortem brain of AD patients (Raskin et al., 2015). During progression of AD, the pathological extra-neuronal Aβ deposits interrupt astrocyte's functions leading to disruption of gliotransmission, neurotransmitter uptake, and Ca2+ handling. The Aβ-induced astrocytic metabolic failure, including the production of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, Ca2+-dependent glutathione depletion, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation and mitochondrial Ca2+ dyshomeostasis, is ultimately linked to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death (Abramov et al., 2004; Abeti et al., 2011). Indeed, Aβ exposure impaired Ca2+ homeostasis via activation of Ca2+ sensitive channels or Ca2+ permeable ionotropic receptors leading to abnormal Ca2+ permeability, and subsequent cytosolic Ca2+ overload (Demuro et al., 2010). The application of Aβ oligomers was found to promote Ca2+ rise associated with ER stress response initiating reactive astrogliosis, which has been characterized both in vitro and in vivo (Alberdi et al., 2013). The development of astrocyte reactivity promotes molecular and morphological remodeling of astrocytes that may have neuroprotective or neurotoxic effects depending on the occurrence of pathological condition in the specific brain region. This phenomenon is observed mainly at the early stages of disease. Remodeled astrocytes usually exhibit changes in gene expression profile, increased level of cytoskeletal structural proteins (GFAP and vimentin), and cellular hypertrophy (Pekny et al., 2016). In animal models of AD, astroglial phenotype transformation emerged around Aβ deposits in the hippocampus, but the reactivity has not been reported in the entorhinal and prefrontal cortex (Verkhratsky et al., 2016). The pro-inflammatory bradykinin which is often elevated in the plasma of AD patients with greater cognitive disruption (Singh et al., 2020), may induce Ca2+ hyperactivity via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in cortical astrocytes cultures (Makitani et al., 2017). It is also worth mentioning that bradykinin is associated with increased NO production and induction of vascular permeability leading to disruption of the BBB barrier integrity (Erickson and Banks, 2013; Makitani et al., 2017).

Loss of dopaminergic neurons, the presence of α-synuclein and inclusion bodies in brain tissue are the hallmarks of Parkinson's disease (PD), the second most recognized neurodegenerative disorder. The α-synuclein proteins secreted from neurons are easily taken up by astrocytes through endocytosis causing inflammatory response such as release of cytokines (IL1, IL6, and TNFα), oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment (Gu et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010). Particularly, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) affect movement control as well as reward response and their progressive degeneration caused by chronic inflammation and reactive astrogliosis, is one of the main factors determining characteristic motor disturbance (e.g., bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor at rest) in PD patients (Michel et al., 2013). Generally, dopamine receptors are classified into two subfamilies, D1-like receptor family coupled to Gs/olf (consists of D1 and D5), and D2-like receptor family coupled to Gi/o (consists of D2, D3, and D4 receptors) to stimulate or inhibit AC/cAMP/PKA transduction pathway, respectively. All five subtypes of dopamine receptors are also expressed in astrocytes. In cultured cortical astrocytes, the application of SKF83959 led to discovery of non-cyclase-coupled D1-like receptor called phosphatidyl-inositol-linked D1 receptor which induces Ca2+ mobilization via the Gq/PLC/IP3 signaling (Liu et al., 2009).

To date, there is no conclusive evidence on the crosstalk between cAMP and Ca2+ in PD pathology, but several reports suggest that mutual modulation of the second messengers in dysfunctional astrocytes likely contributes to neurodegeneration observed in this disorder. So, the following sections highlight this evidence pointing out potential mechanisms that could trigger abnormal Ca2+/cAMP signaling and thus promote loss of supporting astrocyte function.

Astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) defects have been repeatedly demonstrated in numerous neurodegenerative diseases, especially AD, PD but also Huntington's disease (Su et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2019; Hindeya Gebreyesus and Gebrehiwot Gebremichael, 2020). Increased level of Aβ suppresses the expression of two important astroglial transporters: GLAST (glutamate-aspartate transporter, also named EAAT1) and GLT1 (glutamate transporter 1, also named EAAT2) via Gs-coupled A2A receptors decreasing glutamate uptake by astroglia (Matos et al., 2012; Zumkehr et al., 2015). Secondarily, adenosine A2A receptor/PKA signaling pathway regulates intracellular Ca2+ mobilizations and triggers glutamate release. Remarkably, this pathway can stimulate the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration via Ca2+ efflux from intracellular Ca2+ stores independent of IP3 and ryanodine receptor activity (Kanno and Nishizaki, 2012). In AD patients, the overexpression of adenosine A2A receptor gene (ADORA2A) is aggravated (Horgusluoglu-Moloch et al., 2017) which can lead to decreased ability of astrocytes to clear the extracellular glutamate (Matos et al., 2012). In addition to its central function as an energy source, glycogen is also essential to provide energy for glutamate and glutamine synthesis in response to elevated K+ concentrations or neurotransmitters, such as NE, serotonin or ATP (Gibbs et al., 2006; Gibbs, 2016). It is speculated that glycolytic metabolism can be also regulated by coordinated GPCR-coupled cAMP and Ca2+ signals or non-GPCR-coupled Ca2+ and cAMP signals (Bak et al., 2018). Pathologically, disturbance in glycogen homeostasis may decrease glycogenesis and increase glycogenolysis in AD. The glycogen synthesis may be diminished by overactivation of synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) which also promotes abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau and neuroinflammation process (Beurel et al., 2015; Di et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Matellán et al., 2020). Besides, GSK3 activity may be diminished by cAMP-dependent PKA (Llorens-Marítin et al., 2014). On the other hand, exposure to β-amyloid augments the energy consumption of neurons. In such conditions, increased excitability seems to generate a temporary compensation mechanism in response to synaptic loss. Bass and colleagues argue that neuronal metabolic changes drive the depletion of glycogen reserves in the brain via elevated levels of Aβ and astrocytic A2A receptors, ultimately resulting in neuronal hypoactivity as the disease progresses (Bass et al., 2015). Considering that the overactive A2A receptor is sufficient to cause hippocampal-dependent cognitive impairments via PKA/cAMP/CREB signaling (Li et al., 2015) as well as able to affect transcription of genes related to neuroinflammation, angiogenesis and astrocytic reactivity (Paiva et al., 2019), the development of novel therapeutic target against astrocytic A2A receptor-dependent mechanism seems to be rational in the treatment of the AD. In vitro study has demonstrated that A2A receptor antagonism prevented Aβ-induced synaptic degeneration in hippocampus (Gomes et al., 2011). Additionally, the latest results from live-cell imaging of primary cortical astrocytes revealed that application of Aβ25−35 peptide can induce PMCA-mediated Ca2+ extrusion via cAMP signaling. Thus, ATP-dependent Ca2+ extrusion system seems to constitute a protective mechanism aimed to counterbalance the early effects of Ca2+ overload in the presence of neurotoxic Aβ oligomers. On the other hand, their increasing chronic aggregation may impair PMCA activity in astrocytes (Pham et al., 2021).

Additionally, astrocytic Ca2+ signal may generate a rapid astroglial response to the nearby autoreactive immune cells involved in immune-mediated demyelinating disease, called multiple sclerosis (MS). It is believed that this mechanism of intercellular communication may be linked to astrocytic purinergic activation and participation of ATP release to autoinflammation in the CNS (Bijelić et al., 2020). On the other hand, β2-adrenergic-dependent cAMP signaling in reactive astrocytes appears to be downregulated putatively as a result of complete loss of β2-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the MS, what may contribute to disease pathology (De Keyser et al., 1999, 2004). Recently, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)- and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)-linked TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) inclusions have been shown to affect cAMP and Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, most likely due to the downregulation of β2-adrenergic receptors leading to dysregulated astroglial metabolism and disease progression (Velebit et al., 2020).

Similar to AD pathology, reduced glutamate transporters expression has been detected in neurotoxin-induced PD animal models (Holmer et al., 2005; Chung et al., 2008). It is worth noting that the ventral midbrain-derived astrocytes are highly susceptible to D2 receptor-induced Ca2+ signaling. They seem to be relatively insensitive to NE and exhibit significantly different Ca2+-related gene expression profile compared to telencephalic astrocytes (Ibáñez et al., 2019; Xin et al., 2019). In mice SNpc, AAV-mediated GLT1 knockdown elicited reactive astrogliosis, dysfunctional Ca2+ homeostasis (by altered expression of Ca2+ channels and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases) and DA neuronal death generating parkinsonian phenotypes (Zhang et al., 2020). Recent evidence has shown that GLT1 expression is regulated by cAMP and CREB and its internalization depends on Ca2+ mobilization driven mainly by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Liu et al., 2016; Ibáñez et al., 2019). Together, oscillations in Ca2+ and cAMP may be involved at multiple levels in the regulation of glutamate uptake by astrocytes. Hence, accumulation of pathological changes may determine severity of the excitotoxicity in individual brain areas.

Prior post-mortem studies indicated abnormally lowered brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) level in brain tissue of patients with PD (Mogi et al., 1999). Several other evidence showed that BDNF genetic polymorphisms increase the risk of PD-related cognitive impairments (Karamohamed et al., 2005; Altmann et al., 2016). In animal PD models, neurotrophic factors supported the function of dopaminergic system, including prevention from degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and improvement of dopaminergic neurotransmission (Migliore et al., 2014; Palasz et al., 2020). Moreover, the comparable level of BDNF expression between astrocytes and neurons of human brain cortex suggests an equally significant role of astrocytic BDNF in maintaining their neuroprotective and neuroregenerative potential (Koppel et al., 2018). On the other hand, increasing evidence shows that dopaminergic protection depends on changes in astrocytic Ca2+ and cAMP levels (Jennings and Rusakov, 2016). For example, Koppel et al. reported that dopamine-induced BDNF upregulation is dependent on cAMP/CREB stimulation through β-adrenergic receptors in primary astroglia. Likewise, the activation of PI3K/Akt/CREB pathway via FLZ treatment increased GDNF production by astroglia and improved the function of dopaminergic neurons in mouse models of PD (Bao et al., 2020).

One of the main proteins responsible for maintaining cerebral water balance are aquaporins (AQPs), especially type 4 (AQP4). It is highly concentrated in glial endfoot membranes and forms a molecular complex with a transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4 (TRPV4; Benfenati et al., 2011; Lunde et al., 2015). Loss of these channels or their defective membrane assembly, for example during aging, leads to significant impairments in astrocyte polarity, which may exacerbate neurodegenerative progress (Valenza et al., 2020). For example, deletion of AQP4 exacerbated Aβ accumulation and atrophy of astrocytes in APP/PS mouse model of AD (Xu et al., 2015). AQP4 KO mice demonstrated increased 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) neurotoxicity toward dopamine neurons in the striatum. This included alterations in astroglial function and reduced GDNF synthesis (Fan et al., 2008). Another study reported the MPTP treatment led to upregulation of AQP4 expression in mouse substantia nigra. The MRI brain scanning revealed increased water accumulation in the substantia nigra of PD patients (Ofori et al., 2015) suggesting an implication of AQP4 in water imbalance in the PD brain. It has also been reported that the modulation of AQP4 may control inflammatory process and AQP4 dysfunction increased the production of IL1β and TNFα triggering microglial reactivity in the midbrain (Sun et al., 2016).

Song and Gunnarson pointed to the relationship between cAMP signaling in astrocyte water permeability and the extracellular potassium concentration. Uptake of K+ activated AQP4 via PKA-dependent pathway and led to water permeability in astrocytes. Prolonged increase in intracellular K+ due to Kir channel prevented water permeability via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent regulation (Song and Gunnarson, 2012). The relationship between PKA and calmodulin in the regulation of subcellular localization of AQP4 has also been documented (Kitchen et al., 2020). This supports the idea that disrupted Ca2+/cAMP signaling may be involved in altered astrocyte water permeability. The functional coupling between these signaling pathways seems to be involved in neuronal hyperactivity associated with cognitive deficits observed in AD models.

Second messengers, such as Ca2+ and cAMP, orchestrate the release of signaling molecules, including a peptide, called apolipoprotein (ApoE; Kockx et al., 2007), which is primarily synthesized by astrocytes. This peptide is crucial for synthesis, degradation and removal of Aβ from the brain. In vitro, Aβ-upregulated cAMP levels via the classical pathway, Gs-AC, leading to increased ApoE secretion and altered lipid trafficking in astrocytes (Igbavboa et al., 2006; Rossello et al., 2012). Changes in the lipid composition as a result of ApoE4 dysregulation led to pathological Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ hyperactivity in astrocytes (Larramona-Arcas et al., 2020). Compelling evidence suggests that polymorphic variants of APOE gene may correlate with the development of sporadic AD. The presence of the APOE4 allele greatly exacerbates the risk of the disease, while the presence of the APOE2 allele decreases the susceptibility to the disease (Yu et al., 2014; Fernandez et al., 2019). Similarly, current data also indicate various influences of APOE genotypes on αSyn aggregation and APOE4 may exacerbate a series of abnormalities characteristic of PD, such as behavioral disturbances, loss of neural connections and astrogliosis (Zhao et al., 2020).

Taken together, isoform-specific effect of ApoE and alterations in second messenger system may have profound consequences on cholesterol transport and neurotoxicity-induced synaptopathy (Veinbergs et al., 2002; Igbavboa et al., 2006; de Chaves and Narayanaswami, 2008).

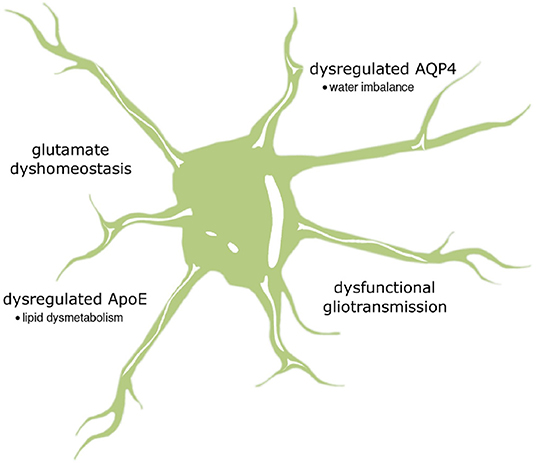

It is commonly known that astrocytes can interact with multiple synapses to receive a vast amount of information. This information is next processed by a system of second messengers acting at different levels. Nonetheless, understanding their intricate interactions remains a challenge for the research environment. This review highlights the importance between cAMP and Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, which modulates the surrounding microenvironment and synaptic plasticity. However, how these mutual relationships contribute to the mechanisms driving neurodegeneration is not fully understood. A growing body of evidence indicates that cAMP and Ca2+ interdependence can effect glutamate clearance from the synaptic cleft, gliotransmitter release and ion and water homeostasis. Even slight abnormalities in these mechanisms may have severe neuropathological consequences (Figure 2). The detailed mechanisms by which Ca2+/cAMP crosstalk in astrocytes affects pathological events leading to neurodegeneration are only beginning to emerge. In conclusion, further studies are essential for a precise understanding of Ca2+ and cAMP dynamics in astrocytes, taking into account the astrocyte region-specific phenotype and the regional susceptibility to synaptic damage and neuronal loss.

Figure 2. The summary of possible impact of astrocytic cAMP and Ca2+ signaling on neurodegenerative pathology. It is supposed that altered relationship between calcium and cAMP may be substantially relevant to the loss of gliotransmission and glutamate uptake as well as changes in the activity of two important proteins, AQP4 and ApoE, regulating water transport and lipid homeostasis, respectively.

MS and TB conceived, designed the topic, and wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Science Center (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) grant no. 2019/33/B/NZ4/00587 and by the Medical University of Lodz grant no. 503/6-086/-2/503-61-001.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abeti, R., Abramov, A. Y., and Duchen, M. R. (2011). β-amyloid activates PARP causing astrocytic metabolic failure and neuronal death. Brain 134, 1658–1672. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr104

Abramov, A. Y., Canevari, L., and Duchen, M. R. (2004). Beta-amyloid peptides induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in astrocytes and death of neurons through activation of NADPH oxidase. J. Neurosci. 24, 565–575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4042-03.2004

Agarwal, A., Wu, P.-H., Hughes, E. G., Fukaya, M., Tischfield, M. A., Langseth, A. J., et al. (2017). Transient opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore induces microdomain calcium transients in astrocyte processes. Neuron 93, 587–605.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.034

Agulhon, C., Sun, M.-Y., Murphy, T., Myers, T., Lauderdale, K., and Fiacco, T. A. (2012). Calcium signaling and gliotransmission in normal vs. reactive astrocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 3, 139. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00139

Alberdi, E., Wyssenbach, A., Alberdi, M., Sánchez-Gómez, M. V., Cavaliere, F., Rodríguez, J. J., et al. (2013). Ca2+-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress correlates with astrogliosis in oligomeric amyloid β-treated astrocytes and in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Aging Cell 12, 292–302. doi: 10.1111/acel.12054

Altmann, V., Schumacher-Schuh, A. F., Rieck, M., Callegari-Jacques, S. M., Rieder, C. R. M., and Hutz, M. H. (2016). Val66Met BDNF polymorphism is associated with Parkinson's disease cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 615, 88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.01.030

Álvarez-Ferradas, C., Morales, J. C., Wellmann, M., Nualart, F., Roncagliolo, M., Fuenzalida, M., et al. (2015). Enhanced astroglial Ca2+ signaling increases excitatory synaptic strength in the epileptic brain. Glia 63, 1507–1521. doi: 10.1002/glia.22817

Bagur, R., and Hajnóczky, G. (2017). Intracellular Ca2+ sensing: role in calcium homeostasis and signaling. Mol. Cell 66, 780–788. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.028

Bak, L. K., Walls, A. B., Schousboe, A., and Waagepetersen, H. S. (2018). Astrocytic glycogen metabolism in the healthy and diseased brain. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7108–7116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.803239

Bao, X.-Q., Wang, L., Yang, H.-Y., Hou, L.-Y., Wang, Q.-S., and Zhang, D. (2020). Induction of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor by the squamosamide derivative FLZ in astroglia has neuroprotective effects on dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res. Bullet. 154, 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.10.008

Bass, B., Upson, S., Roy, K., Montgomery, E. L., Jalonen, T. O., and Murray, I. V. J. (2015). Glycogen and amyloid-beta: key players in the shift from neuronal hyperactivity to hypoactivity observed in Alzheimer's disease? Neural Regen. Res. 10, 1023–1025. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.160059

Bazargani, N., and Attwell, D. (2016). Astrocyte calcium signaling: the third wave. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4201

Bender, A. T., and Beavo, J. A. (2006). Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5

Benfenati, V., Caprini, M., Dovizio, M., Mylonakou, M. N., Ferroni, S., Ottersen, O. P., et al. (2011). An aquaporin-4/transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (AQP4/TRPV4) complex is essential for cell-volume control in astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 2563–2568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012867108

Beurel, E., Grieco, S. F., and Jope, R. S. (2015). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 16, 114–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016

Bijelić, D. D., Milićević, K. D., Lazarević, M. N., Miljković, D. M., Bogdanović Pristov, J. J., Savić, D. Z., et al. (2020). Central nervous system-infiltrated immune cells induce calcium increase in astrocytes via astroglial purinergic signaling. J. Neurosci. Res. 98, 2317–2332. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24699

Boczek, T., Yu, Q., Zhu, Y., Dodge-Kafka, K. L., Goldberg, J. L., and Kapiloff, M. S. (2021). cAMP at perinuclear mAKAPα signalosomes is regulated by local Ca2+ signaling in primary hippocampal neurons. eNeuro 8, 2021. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0298-20.2021

Brini, M., and Carafoli, E. (2011). The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase and the plasma membrane sodium calcium exchanger cooperate in the regulation of cell calcium. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a004168. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004168

Britti, E., Delaspre, F., Tamarit, J., and Ros, J. (2018). Mitochondrial calcium signalling and neurodegenerative diseases. Neuronal. Signal 2:NS20180061. doi: 10.1042/NS20180061

Burgos, M., Pastor, M. D., González, J. C., Martinez-Galan, J. R., Vaquero, C. F., Fradejas, N., et al. (2007). PKCepsilon upregulates voltage-dependent calcium channels in cultured astrocytes. Glia 55, 1437–1448. doi: 10.1002/glia.20555

Cao, X., Li, L.-P., Wang, Q., Wu, Q., Hu, H.-H., Zhang, M., et al. (2013). Astrocyte-derived ATP modulates depressive-like behaviors. Nat. Med. 19, 773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3162

Carson, M. J., Thomas, E. A., Danielson, P. E., and Sutcliffe, J. G. (1996). The 5HT5A serotonin receptor is expressed predominantly by astrocytes in which it inhibits cAMP accumulation: a mechanism for neuronal suppression of reactive astrocytes. Glia 17, 317–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199608)17:4<317::AID-GLIA6>3.0.CO;2-W

Catterall, W. A.. (2011). Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947

Catus, S. L., Gibbs, M. E., Sato, M., Summers, R. J., and Hutchinson, D. S. (2011). Role of β-adrenoceptors in glucose uptake in astrocytes using β-adrenoceptor knockout mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 1700–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01153.x

Ceprian, M., and Fulton, D. (2019). Glial cell AMPA receptors in nervous system health, injury and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2450. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102450

Chen, N., Sugihara, H., Sharma, J., Perea, G., Petravicz, J., Le, C., et al. (2012). Nucleus basalis-enabled stimulus-specific plasticity in the visual cortex is mediated by astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, E2832–2841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206557109

Chen, Y., Du, T., Peng, L., Gibbs, M. E., and Hertz, L. (2016). Sequential astrocytic 5-HT2B receptor stimulation, [Ca2+]i regulation, glycogenolysis, glutamate synthesis, and K+ homeostasis are similar but not identical in learning and mood regulation. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9, 67. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2015.00067

Choi, H. B., Gordon, G. R. J., Zhou, N., Tai, C., Rungta, R. L., Martinez, J., et al. (2012). Metabolic communication between astrocytes and neurons via bicarbonate-responsive soluble adenylyl cyclase. Neuron 75, 1094–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.032

Chung, E. K. Y., Chen, L. W., Chan, Y. S., and Yung, K. K. L. (2008). Downregulation of glial glutamate transporters after dopamine denervation in the striatum of 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 511, 421–437. doi: 10.1002/cne.21852

Ciccarelli, R., D'Alimonte, I., Ballerini, P., D'Auro, M., Nargi, E., Buccella, S., et al. (2007). Molecular signalling mediating the protective effect of A1 adenosine and mGlu3 metabotropic glutamate receptor activation against apoptosis by oxygen/glucose deprivation in cultured astrocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 1369–1380. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031617

Copeland, C. S., Wall, T. M., Sims, R. E., Neale, S. A., Nisenbaum, E., Parri, H. R., et al. (2017). Astrocytes modulate thalamic sensory processing via mGlu2 receptor activation. Neuropharmacology 121, 100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.04.019

Corkrum, M., Covelo, A., Lines, J., Bellocchio, L., Pisansky, M., Loke, K., et al. (2020). Dopamine-evoked synaptic regulation in the nucleus accumbens requires astrocyte activity. Neuron 105, 1036–1047.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.12.026

Cristóvão-Ferreira, S., Navarro, G., Brugarolas, M., Pérez-Capote, K., Vaz, S. H., Fattorini, G., et al. (2013). A1R–A2AR heteromers coupled to Gs and Gi/0 proteins modulate GABA transport into astrocytes. Purinergic Signal 9, 433–449. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9364-5

de Chaves, E. P., and Narayanaswami, V. (2008). Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol in aging and disease in the brain. Fut. Lipidol. 3, 505–530. doi: 10.2217/17460875.3.5.505

De Keyser, J., Wilczak, N., Leta, R., and Streetland, C. (1999). Astrocytes in multiple sclerosis lack beta-2 adrenergic receptors. Neurology 53, 1628–1633. doi: 10.1212/WNL.53.8.1628

De Keyser, J., Zeinstra, E., and Wilczak, N. (2004). Astrocytic beta2-adrenergic receptors and multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 15, 331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.10.012

Demuro, A., Parker, I., and Stutzmann, G. E. (2010). Calcium signaling and amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12463–12468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.080895

Di, J., Cohen, L. S., Corbo, C. P., Phillips, G. R., El Idrissi, A., and Alonso, A. D. (2016). Abnormal tau induces cognitive impairment through two different mechanisms: synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Sci. Rep. 6:20833. doi: 10.1038/srep20833

Ding, F., O'Donnell, J., Thrane, A. S., Zeppenfeld, D., Kang, H., Xie, L., et al. (2013). α1-adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice. Cell Calcium 54, 387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.09.001

Ding, S., Wang, T., Cui, W., and Haydon, P. G. (2009). Photothrombosis ischemia stimulates a sustained astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in vivo. Glia 57, 767–776. doi: 10.1002/glia.20804

Durkee, C. A., and Araque, A. (2019). Diversity and specificity of astrocyte-neuron communication. Neuroscience 396, 73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.11.010

Durkee, C. A., Covelo, A., Lines, J., Kofuji, P., Aguilar, J., and Araque, A. (2019). Gi/o protein-coupled receptors inhibit neurons but activate astrocytes and stimulate gliotransmission. Glia 67, 1076–1093. doi: 10.1002/glia.23589

Erickson, M. A., and Banks, W. A. (2013). Blood–brain barrier dysfunction as a cause and consequence of Alzheimer's disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1500–1513. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.135

Fan, Y., Kong, H., Shi, X., Sun, X., Ding, J., Wu, J., et al. (2008). Hypersensitivity of aquaporin 4-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrindine and astrocytic modulation. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 1226–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.015

Fernandez, C. G., Hamby, M. E., McReynolds, M. L., and Ray, W. J. (2019). The role of APOE4 in disrupting the homeostatic functions of astrocytes and microglia in aging and alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 14. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00014

Gancedo, J. M.. (2013). Biological roles of cAMP: variations on a theme in the different kingdoms of life. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 88, 645–668. doi: 10.1111/brv.12020

Gee, J. M., Gibbons, M. B., Taheri, M., Palumbos, S., Morris, S. C., Smeal, R. M., et al. (2015). Imaging activity in astrocytes and neurons with genetically encoded calcium indicators following in utero electroporation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8, 10. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00010

Gibbs, M. E.. (2016). Role of glycogenolysis in memory and learning: regulation by noradrenaline, serotonin and ATP. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9:70. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2015.00070

Gibbs, M. E., Anderson, D. G., and Hertz, L. (2006). Inhibition of glycogenolysis in astrocytes interrupts memory consolidation in young chickens. Glia 54, 214–222. doi: 10.1002/glia.20377

Gomes, C. V., Kaster, M. P., Tomé, A. R., Agostinho, P. M., and Cunha, R. A. (2011). Adenosine receptors and brain diseases: neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 1380–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.001

Gould, T., Chen, L., Emri, Z., Pirttimaki, T., Errington, A. C., Crunelli, V., et al. (2014). GABAB receptor-mediated activation of astrocytes by gamma-hydroxybutyric acid. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130607. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0607

Gu, X.-L., Long, C.-X., Sun, L., Xie, C., Lin, X., and Cai, H. (2010). Astrocytic expression of Parkinson's disease-related A53T α-synuclein causes neurodegeneration in mice. Mol. Brain 3, 12. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-3-12

Guerra-Gomes, S., Cunha-Garcia, D., Marques Nascimento, D. S., Duarte-Silva, S., Loureiro-Campos, E., Morais Sardinha, V., et al. (2021). IP3 R2 null mice display a normal acquisition of somatic and neurological development milestones. Eur. J. Neurosci. 54, 5673–5686. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14724

Halls, M. L., and Cooper, D. M. F. (2011). Regulation by Ca2+-signaling pathways of adenylyl cyclases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a004143. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004143

Harada, K., Kamiya, T., and Tsuboi, T. (2015). Gliotransmitter release from astrocytes: functional, developmental, and pathological implications in the brain. Front. Neurosci. 9:499. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00499

Hindeya Gebreyesus, H., and Gebrehiwot Gebremichael, T. (2020). The potential role of astrocytes in Parkinson's disease (PD). Med. Sci. 8, 7. doi: 10.3390/medsci8010007

Holmer, H. K., Keyghobadi, M., Moore, C., and Meshul, C. K. (2005). l-dopa-induced reversal in striatal glutamate following partial depletion of nigrostriatal dopamine with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Neuroscience 136, 333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.003

Horgusluoglu-Moloch, E., Nho, K., Risacher, S. L., Kim, S., Foroud, T., Shaw, L. M., et al. (2017). Targeted neurogenesis pathway-based gene analysis identifies ADORA2A associated with hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 60, 92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.08.010

Horvat, A., and Vardjan, N. (2019). Astroglial cAMP signalling in space and time. Neurosci. Lett. 689, 5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.06.025

Horvat, A., Zorec, R., and Vardjan, N. (2016). Adrenergic stimulation of single rat astrocytes results in distinct temporal changes in intracellular Ca(2+) and cAMP-dependent PKA responses. Cell Calcium 59, 156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.01.002

Hua, X., Malarkey, E. B., Sunjara, V., Rosenwald, S. E., Li, W.-H., and Parpura, V. (2004). Ca(2+)-dependent glutamate release involves two classes of endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) stores in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 76, 86–97. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20061

Huang, Y., and Thathiah, A. (2015). Regulation of neuronal communication by G protein-coupled receptors. FEBS Lett. 589, 1607–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.007

Hur, Y. S., Kim, K. D., Paek, S. H., and Yoo, S. H. (2010). Evidence for the existence of secretory granule (dense-core vesicle)-based inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ signaling system in astrocytes. PLoS ONE 5:e11973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011973

Ibáñez, I., Bartolomé-Martín, D., Piniella, D., Giménez, C., and Zafra, F. (2019). Activity dependent internalization of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 requires calcium entry through the NCX sodium/calcium exchanger. Neurochem. Int. 123, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.03.012

Igbavboa, U., Johnson-Anuna, L. N., Rossello, X., Butterick, T. A., Sun, G. Y., and Wood, W. G. (2006). Amyloid beta-protein1-42 increases cAMP and apolipoprotein E levels which are inhibited by β1 and β2-adrenergic receptor antagonists in mouse primary astrocytes. Neuroscience 142, 655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.056

Jastrzebska, B.. (2013). GPCR – G protein complexes – the fundamental signaling assembly. Amino Acids 45, 1303–1314. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1593-y

Jennings, A., and Rusakov, D. A. (2016). Do astrocytes respond to dopamine? Opera Medica et Physiol. 2, 34–43. doi: 10.20388/OMP2016.001.0017

Jeremic, D., Sanchez-Rodriguez, I., Jimenez-Diaz, L., and Navarro-Lopez, J. D. (2021). Therapeutic potential of targeting G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in the central nervous system. Pharmacol. Ther. 223, 107808. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107808

Kanno, T., and Nishizaki, T. (2012). A(2a) adenosine receptor mediates PKA-dependent glutamate release from synaptic-like vesicles and Ca(2+) efflux from an IP(3)- and ryanodine-insensitive intracellular calcium store in astrocytes. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 30, 1398–1412. doi: 10.1159/000343328

Karamohamed, S., Latourelle, J. C., Racette, B. A., Perlmutter, J. S., Wooten, G. F., Lew, M., et al. (2005). BDNF genetic variants are associated with onset age of familial Parkinson disease: GenePD Study. Neurology 65, 1823–1825. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187075.81589.fd

Kárpáti, A., Yoshikawa, T., Nakamura, T., Iida, T., Matsuzawa, T., Kitano, H., et al. (2018). Histamine elicits glutamate release from cultured astrocytes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 137, 122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2018.05.002

Kawamata, H., Ng, S. K., Diaz, N., Burstein, S., Morel, L., Osgood, A., et al. (2014). Abnormal intracellular calcium signaling and SNARE-dependent exocytosis contributes to SOD1G93A astrocyte-mediated toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 34, 2331–2348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2689-13.2014

King, C. M., Bohmbach, K., Minge, D., Delekate, A., Zheng, K., Reynolds, J., et al. (2020). Local resting Ca2+ controls the scale of astroglial Ca2+ signals. Cell Rep. 30, 3466–3477.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.043

Kinoshita, M., Hirayama, Y., Fujishita, K., Shibata, K., Shinozaki, Y., Shigetomi, E., et al. (2018). Anti-depressant fluoxetine reveals its therapeutic effect via astrocytes. EBioMedicine 32, 72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.05.036

Kitano, T., Eguchi, R., Okamatsu-Ogura, Y., Yamaguchi, S., and Otsuguro, K. (2021). Opposing functions of α- and β-adrenoceptors in the formation of processes by cultured astrocytes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 145, 228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2020.12.005

Kitchen, P., Salman, M. M., Halsey, A. M., Clarke-Bland, C., MacDonald, J. A., Ishida, H., et al. (2020). Targeting aquaporin-4 subcellular localization to treat central nervous system edema. Cell 181:784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.037

Kockx, M., Guo, D. L., Huby, T., Lesnik, P., Kay, J., Sabaretnam, T., et al. (2007). Secretion of apolipoprotein E from macrophages occurs via a protein kinase A and calcium-dependent pathway along the microtubule network. Circ. Res. 101, 607–616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157198

Kofuji, P., and Araque, A. (2021). Astrocytes and behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 44, 49–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-101920-112225

Koppel, I., Jaanson, K., Klasche, A., Tuvikene, J., Tiirik, T., Pärn, A., et al. (2018). Dopamine cross-reacts with adrenoreceptors in cortical astrocytes to induce BDNF expression, CREB signaling and morphological transformation. Glia 66, 206–216. doi: 10.1002/glia.23238

Lalo, U., Bogdanov, A., and Pankratov, Y. (2019). Age- and experience-related plasticity of ATP-mediated signaling in the neocortex. Front. Cell Neurosci. 13, 242. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00242

Larramona-Arcas, R., González-Arias, C., Perea, G., Gutiérrez, A., Vitorica, J., García-Barrera, T., et al. (2020). Sex-dependent calcium hyperactivity due to lysosomal-related dysfunction in astrocytes from APOE4 vs. APOE3 gene targeted replacement mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 35. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00382-8

Lasič, E., Lisjak, M., Horvat, A., BoŽić, M., Šakanović, A., Anderluh, G., et al. (2019). Astrocyte specific remodeling of plasmalemmal cholesterol composition by ketamine indicates a new mechanism of antidepressant action. Sci. Rep. 9:10957. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47459-z

Lee, H.-J., Suk, J.-E., Patrick, C., Bae, E.-J., Cho, J.-H., Rho, S., et al. (2010). Direct transfer of α-synuclein from neuron to astroglia causes inflammatory responses in synucleinopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9262–9272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081125

Lee, N., Sa, M., Hong, Y. R., Lee, C. J., and Koo, J. (2018). Fatty acid increases cAMP-dependent lactate and MAO-B-dependent GABA production in mouse astrocytes by activating a gαs protein-coupled receptor. Exp. Neurobiol. 27, 365–376. doi: 10.5607/en.2018.27.5.365

Li, P., Rial, D., Canas, P. M., Yoo, J.-H., Li, W., Zhou, X., et al. (2015). Optogenetic activation of intracellular adenosine A2A receptor signaling in the hippocampus is sufficient to trigger CREB phosphorylation and impair memory. Mol. Psychiatry 20, 1339–1349. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.182

Liu, B., Teschemacher, A. G., and Kasparov, S. (2017). Astroglia as a cellular target for neuroprotection and treatment of neuro-psychiatric disorders. Glia 65, 1205–1226. doi: 10.1002/glia.23136

Liu, J., Wang, F., Huang, C., Long, L.-H., Wu, W.-N., Cai, F., et al. (2009). Activation of phosphatidylinositol-linked novel D1 dopamine receptor contributes to the calcium mobilization in cultured rat prefrontal cortical astrocytes. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 29, 317–328. doi: 10.1007/s10571-008-9323-9

Liu, X., Guo, H., Sayed, M. D. S., Lu, Y., Yang, T., Zhou, D., et al. (2016). cAMP/PKA/CREB/GLT1 signaling involved in the antidepressant-like effects of phosphodiesterase 4D inhibitor (GEBR-7b) in rats. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 12, 219–227. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S90960

Llorens-Marítin, M., Jurado, J., Hernández, F., and Ávila, J. (2014). GSK-3β, a pivotal kinase in Alzheimer disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7:46. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00046

Lunde, L. K., Camassa, L. M. A., Hoddevik, E. H., Khan, F. H., Ottersen, O. P., Boldt, H. B., et al. (2015). Postnatal development of the molecular complex underlying astrocyte polarization. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 2087–2101. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0775-z

Machelska, H., and Celik, M. Ö. (2020). Opioid receptors in immune and glial cells-implications for pain control. Front. Immunol. 11, 300. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00300

MacVicar, B. A., and Choi, H. B. (2017). Astrocytes provide metabolic support for neuronal synaptic function in response to extracellular K. Neurochem. Res. 42, 2588–2594. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2315-8

Makitani, K., Nakagawa, S., Izumi, Y., Akaike, A., and Kume, T. (2017). Inhibitory effect of donepezil on bradykinin-induced increase in the intracellular calcium concentration in cultured cortical astrocytes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 134, 37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.03.008

Mariotti, L., Losi, G., Sessolo, M., Marcon, I., and Carmignoto, G. (2016). The inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA evokes long-lasting Ca2+ oscillations in cortical astrocytes. Glia 64, 363–373. doi: 10.1002/glia.22933

Masmoudi-Kouki, O., Gandolfo, P., Castel, H., Leprince, J., Fournier, A., Dejda, A., et al. (2007). Role of PACAP and VIP in astroglial functions. Peptides 28, 1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.05.015

Massengill, C. I., Day-Cooney, J., Mao, T., and Zhong, H. (2021). Genetically encoded sensors towards imaging cAMP and PKA activity in vivo. J. Neurosci. Methods 362:109298. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2021.109298

Matias, I., Morgado, J., and Gomes, F. C. A. (2019). Astrocyte heterogeneity: impact to brain aging and disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11:59. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00059

Matos, M., Augusto, E., Machado, N. J., dos Santos-Rodrigues, A., Cunha, R. A., and Agostinho, P. (2012). Astrocytic adenosine A2A receptors control the amyloid-β peptide-induced decrease of glutamate uptake. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 31, 555–567. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120469

Michel, P. P., Toulorge, D., Guerreiro, S., and Hirsch, E. C. (2013). Specific needs of dopamine neurons for stimulation in order to survive: implication for Parkinson's disease. FASEB J. 27, 3414–3423. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220418

Migliore, M. M., Ortiz, R., Dye, S., Campbell, R. B., Amiji, M. M., and Waszczak, B. L. (2014). Neurotrophic and neuroprotective efficacy of intranasal GDNF in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience 274, 11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.05.019

Modi, K. K., Sendtner, M., and Pahan, K. (2013). Up-regulation of ciliary neurotrophic factor in astrocytes by aspirin. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 18533–18545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447268

Mogi, M., Togari, A., Kondo, T., Mizuno, Y., Komure, O., Kuno, S., et al. (1999). Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth factor concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 270, 45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00463-2

Müller, M. S., Fox, R., Schousboe, A., Waagepetersen, H. S., and Bak, L. K. (2014). Astrocyte glycogenolysis is triggered by store-operated calcium entry and provides metabolic energy for cellular calcium homeostasis. Glia 62, 526–534. doi: 10.1002/glia.22623

Nagai, J., Rajbhandari, A. K., Gangwani, M. R., Hachisuka, A., Coppola, G., Masmanidis, S. C., et al. (2019). Hyperactivity with disrupted attention by activation of an astrocyte synaptogenic cue. Cell 177, 1280–1292.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.019

Navarrete, M., Perea, G., Fernandez de Sevilla, D., Gómez-Gonzalo, M., Núñez, A., Martín, E. D., et al. (2012). Astrocytes mediate in vivo cholinergic-induced synaptic plasticity. PLoS Biol. 10:e1001259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001259

Oberheim, N. A., Goldman, S. A., and Nedergaard, M. (2012). Heterogeneity of astrocytic form and function. Methods Mol. Biol. 814, 23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_3

Oe, Y., Wang, X., Patriarchi, T., Konno, A., Ozawa, K., Yahagi, K., et al. (2020). Distinct temporal integration of noradrenaline signaling by astrocytic second messengers during vigilance. Nat. Commun. 11:471. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14378-x

Ofori, E., Pasternak, O., Planetta, P. J., Burciu, R., Snyder, A., Febo, M., et al. (2015). Increased free-water in the substantia nigra of Parkinson's disease: a single-site and multi-site study. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.029

Okubo, Y., Kanemaru, K., Suzuki, J., Kobayashi, K., Hirose, K., and Iino, M. (2019). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 2-independent Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum in astrocytes. Glia 67, 113–124. doi: 10.1002/glia.23531

Paco, S., Hummel, M., Plá, V., Sumoy, L., and Aguado, F. (2016). Cyclic AMP signaling restricts activation and promotes maturation and antioxidant defenses in astrocytes. BMC Genom. 17:304. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2623-4

Padmashri, R., Suresh, A., Boska, M. D., and Dunaevsky, A. (2015). Motor-skill learning is dependent on astrocytic activity. Neural Plast. 2015:938023. doi: 10.1155/2015/938023

Paiva, I., Carvalho, K., Santos, P., Cellai, L., Pavlou, M. A. S., Jain, G., et al. (2019). A2A R-induced transcriptional deregulation in astrocytes: an in vitro study. Glia 67, 2329–2342. doi: 10.1002/glia.23688

Palasz, E., Wysocka, A., Gasiorowska, A., Chalimoniuk, M., Niewiadomski, W., and Niewiadomska, G. (2020). BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1170. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031170

Palygin, O., Lalo, U., and Pankratov, Y. (2011). Distinct pharmacological and functional properties of NMDA receptors in mouse cortical astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 1755–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01374.x

Palygin, O., Lalo, U., Verkhratsky, A., and Pankratov, Y. (2010). Ionotropic NMDA and P2X1/5 receptors mediate synaptically induced Ca2+ signalling in cortical astrocytes. Cell Calcium 48, 225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.09.004

Panatier, A., Vallée, J., Haber, M., Murai, K. K., Lacaille, J.-C., and Robitaille, R. (2011). Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell 146, 785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022

Pankratov, Y., and Lalo, U. (2015). Role for astroglial α1-adrenoreceptors in gliotransmission and control of synaptic plasticity in the neocortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:230. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00230

Papouin, T., Dunphy, J., Tolman, M., Dineley, K. T., and Haydon, P. G. (2017). Septal cholinergic neuromodulation tunes the astrocyte-dependent gating of hippocampal NMDA receptors to wakefulness. Neuron 94, 840-854.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.021

Pekny, M., Pekna, M., Messing, A., Steinhäuser, C., Lee, J.-M., Parpura, V., et al. (2016). Astrocytes: a central element in neurological diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 323–345. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1513-1

Peng, L., and Huang, J. (2012). Astrocytic 5-HT(2B) receptor as in vitro and in vivo target of SSRIs. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 7, 243–253. doi: 10.2174/157488912803252078

Perez-Alvarez, A., Navarrete, M., Covelo, A., Martin, E. D., and Araque, A. (2014). Structural and functional plasticity of astrocyte processes and dendritic spine interactions. J. Neurosci. 34, 12738–12744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2401-14.2014

Petravicz, J., Boyt, K. M., and McCarthy, K. D. (2014). Astrocyte IP3R2-dependent Ca(2+) signaling is not a major modulator of neuronal pathways governing behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8:384. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00384

Petravicz, J., Fiacco, T. A., and McCarthy, K. D. (2008). Loss of IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ increases in hippocampal astrocytes does not affect baseline CA1 pyramidal neuron synaptic activity. J. Neurosci. 28, 4967–4973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-07.2008

Pham, C., Hérault, K., Oheim, M., Maldera, S., Vialou, V., Cauli, B., et al. (2021). Astrocytes respond to a neurotoxic Aβ fragment with state-dependent Ca2+ alteration and multiphasic transmitter release. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9:44. doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01146-1

Pöyhönen, S., Er, S., Domanskyi, A., and Airavaara, M. (2019). Effects of neurotrophic factors in glial cells in the central nervous system: expression and properties in neurodegeneration and injury. Front. Physiol. 10:486. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00486

Ramos, B. P., and Arnsten, A. F. T. (2007). Adrenergic pharmacology and cognition: focus on the prefrontal cortex. Pharmacol. Ther. 113, 523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.006

Raskin, J., Cummings, J., Hardy, J., Schuh, K., and Dean, R. A. (2015). Neurobiology of Alzheimer's disease: integrated molecular, physiological, anatomical, biomarker, and cognitive dimensions. Curr. Alzheimer's Res. 12, 712–722. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150701103107

Reeves, A. M. B., Shigetomi, E., and Khakh, B. S. (2011). Bulk loading of calcium indicator dyes to study astrocyte physiology: key limitations and improvements using morphological maps. J. Neurosci. 31, 9353–9358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0127-11.2011

Requardt, R. P., Wilhelm, F., Rillich, J., Winkler, U., and Hirrlinger, J. (2010). The biphasic NAD(P)H fluorescence response of astrocytes to dopamine reflects the metabolic actions of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. J. Neurochem. 115, 483–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06940.x

Reuschlein, A.-K., Jakobsen, E., Mertz, C., and Bak, L. K. (2019). Aspects of astrocytic cAMP signaling with an emphasis on the putative power of compartmentalized signals in health and disease. Glia 67, 1625–1636. doi: 10.1002/glia.23622

Robertson, J. M.. (2018). The gliocentric brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:3033. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103033

Rodríguez-Matellán, A., Avila, J., and Hernández, F. (2020). Overexpression of GSK-3β in adult tet-OFF GSK-3β transgenic mice, and not during embryonic or postnatal development, induces tau phosphorylation, neurodegeneration and learning deficits. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13:175. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.561470

Rodríguez-Prados, M., Rojo-Ruiz, J., García-Sancho, J., and Alonso, M. T. (2020). Direct monitoring of ER Ca2+ dynamics reveals that Ca2+ entry induces ER-Ca2+ release in astrocytes. Pflugers Arch. 472, 439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02364-7

Rose, C. R., Ziemens, D., and Verkhratsky, A. (2020). On the special role of NCX in astrocytes: translating Na+-transients into intracellular Ca2+ signals. Cell Calcium 86:102154. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2019.102154

Rossello, X., Igbavboa, U., Weisman, G. A., Sun, G. Y., and Wood, W. G. (2012). AP-2β regulates amyloid beta-protein stimulation of apolipoprotein E transcription in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1444, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.017

Santello, M., Bezzi, P., and Volterra, A. (2011). TNFα controls glutamatergic gliotransmission in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuron 69, 988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.003

Scemes, E., and Giaume, C. (2006). Astrocyte calcium waves. Glia 54, 716–725. doi: 10.1002/glia.20374

Schmid, A., Meili, D., and Salathe, M. (2014). Soluble adenylyl cyclase in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 2584–2592. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.07.010

Scott, J. D., and Santana, L. F. (2010). A-kinase anchoring proteins: getting to the heart of the matter. Circulation 121, 1264–1271. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.896357

Semyanov, A., Henneberger, C., and Agarwal, A. (2020). Making sense of astrocytic calcium signals — from acquisition to interpretation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 551–564. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0361-8

Shanmughapriya, S., Rajan, S., Hoffman, N. E., Zhang, X., Guo, S., Kolesar, J. E., et al. (2015). Ca2+ signals regulate mitochondrial metabolism by stimulating CREB-mediated expression of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter gene mcu. Sci. Signal 8:ra23. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005673

Sharma, A., Kazim, S. F., Larson, C. S., Ramakrishnan, A., Gray, J. D., McEwen, B. S., et al. (2019). Divergent roles of astrocytic vs. neuronal EAAT2 deficiency on cognition and overlap with aging and Alzheimer's molecular signatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 21800–21811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903566116

Sherwood, M. W., Arizono, M., Hisatsune, C., Bannai, H., Ebisui, E., Sherwood, J. L., et al. (2017). Astrocytic IP3 Rs: contribution to Ca2+ signalling and hippocampal LTP. Glia 65, 502–513. doi: 10.1002/glia.23107

Sherwood, M. W., Arizono, M., Panatier, A., Mikoshiba, K., and Oliet, S. H. R. (2021). Astrocytic IP3Rs: beyond IP3R2. Front. Cell Neurosci. 15:695817. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.695817

Shigetomi, E., Jackson-Weaver, O., Huckstepp, R. T., O'Dell, T. J., and Khakh, B. S. (2013). TRPA1 channels are regulators of astrocyte basal calcium levels and long-term potentiation via constitutive d-serine release. J. Neurosci. 33, 10143–10153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5779-12.2013

Shigetomi, E., Tong, X., Kwan, K. Y., Corey, D. P., and Khakh, B. S. (2011). TRPA1 channels regulate astrocyte resting calcium and inhibitory synapse efficacy through GAT-3. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 70–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.3000

Singh, P. K., Chen, Z.-L., Ghosh, D., Strickland, S., and Norris, E. H. (2020). Increased plasma bradykinin level is associated with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's patients. Neurobiol. Dis. 139:104833. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104833

Skowrońska, K., Kozłowska, H., and Albrecht, J. (2020). Neuron-derived factors negatively modulate ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release in cultured mouse astrocytes. Cell Calcium 92:102304. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2020.102304

Song, Y., and Gunnarson, E. (2012). Potassium dependent regulation of astrocyte water permeability is mediated by cAMP signaling. PLoS ONE 7:e34936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034936

Steeland, S., Gorlé, N., Vandendriessche, C., Balusu, S., Brkic, M., Van Cauwenberghe, C., et al. (2018). Counteracting the effects of TNF receptor-1 has therapeutic potential in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 10:e8300. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201708300

Stenovec, M.. (2021). Ketamine alters functional plasticity of astroglia: an implication for antidepressant effect. Life 11:573. doi: 10.3390/life11060573

Stenovec, M., Li, B., Verkhratsky, A., and Zorec, R. (2020). Astrocytes in rapid ketamine antidepressant action. Neuropharmacology 173:108158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108158

Stephen, T.-L., Gupta-Agarwal, S., and Kittler, J. T. (2014). Mitochondrial dynamics in astrocytes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 1302–1310. doi: 10.1042/BST20140195

Su, Z., Leszczyniecka, M., Kang, D., Sarkar, D., Chao, W., Volsky, D. J., et al. (2003). Insights into glutamate transport regulation in human astrocytes: cloning of the promoter for excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 1955–1960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136555100

Sun, H., Liang, R., Yang, B., Zhou, Y., Liu, M., Fang, F., et al. (2016). Aquaporin-4 mediates communication between astrocyte and microglia: implications of neuroinflammation in experimental Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience 317, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.003

Sun, W., McConnell, E., Pare, J.-F., Xu, Q., Chen, M., Peng, W., et al. (2013). Glutamate-dependent neuroglial calcium signaling differs between young and adult brain. Science 339, 197–200. doi: 10.1126/science.1226740

Takata, N., Mishima, T., Hisatsune, C., Nagai, T., Ebisui, E., Mikoshiba, K., et al. (2011). Astrocyte calcium signaling transforms cholinergic modulation to cortical plasticity in vivo. J. Neurosci. 31, 18155–18165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-11.2011

Taylor, C. W.. (2017). Regulation of IP3 receptors by cyclic AMP. Cell Calcium 63, 48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.10.005

Tenner, B., Getz, M., Ross, B., Ohadi, D., Bohrer, C. H., Greenwald, E., et al. (2020). Spatially compartmentalized phase regulation of a Ca2+-cAMP-PKA oscillatory circuit. eLife 9:e55013. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55013.sa2

Tresguerres, M., Levin, L. R., and Buck, J. (2011). Intracellular cAMP signaling by soluble adenylyl cyclase. Kidney Int. 79, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.95

Turunen, T., and Koskelainen, A. (2021). Functional modulation of phosphodiesterase-6 by calcium in mouse rod photoreceptors. Sci. Rep. 11:8938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88140-8

Ujita, S., Sasaki, T., Asada, A., Funayama, K., Gao, M., Mikoshiba, K., et al. (2017). cAMP-dependent calcium oscillations of astrocytes: an implication for pathology. Cerebr. Cortex 27, 1602–1614. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv310

Valenza, M., Facchinetti, R., Steardo, L., and Scuderi, C. (2020). Altered waste disposal system in aging and Alzheimer's disease: focus on astrocytic aquaporin-4. Front. Pharmacol. 10:1656. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01656

Vandecaetsbeek, I., Vangheluwe, P., Raeymaekers, L., Wuytack, F., and Vanoevelen, J. (2011). The Ca2+ pumps of the endoplasmic reticulum and golgi apparatus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a004184. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004184

Veinbergs, I., Everson, A., Sagara, Y., and Masliah, E. (2002). Neurotoxic effects of apolipoprotein E4 are mediated via dysregulation of calcium homeostasis. J. Neurosci. Res. 67, 379–387. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10138

Velebit, J., Horvat, A., Smoli,č, T., Prpar Mihevc, S., Rogelj, B., Zorec, R., et al. (2020). Astrocytes with TDP-43 inclusions exhibit reduced noradrenergic cAMP and Ca2+ signaling and dysregulated cell metabolism. Sci. Rep. 10:6003. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62864-5

Verkhratsky, A., and Nedergaard, M. (2018). Physiology of astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 98, 239–389. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2016

Verkhratsky, A., Zorec, R., Rodríguez, J. J., and Parpura, V. (2016). Astroglia dynamics in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 26, 74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.09.011

von Bartheld, C. S., Bahney, J., and Herculano-Houzel, S. (2016). The search for true numbers of neurons and glial cells in the human brain: a review of 150 years of cell counting. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 3865–3895. doi: 10.1002/cne.24040