- Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy

Neuropeptides are emerging as key regulators of stem cell niche activities in health and disease, both inside and outside the central nervous system (CNS). Among them, neuropeptide Y (NPY), one of the most abundant neuropeptides both in the nervous system and in non-neural districts, has become the focus of much attention for its involvement in a wide range of physiological and pathological conditions, including the modulation of different stem cell activities. In particular, a pro-neurogenic role of NPY has been evidenced in the neurogenic niche, where a direct effect on neural progenitors has been demonstrated, while different cellular types, including astrocytes, microglia and endothelial cells, also appear to be responsive to the peptide. The marked modulation of the NPY system during several pathological conditions that affect neurogenesis, including stress, seizures and neurodegeneration, further highlights the relevance of this peptide in the regulation of adult neurogenesis. In view of the considerable interest in understanding the mechanisms controlling neural cell fate, this review aims to summarize and discuss current data on NPY signaling in the different cellular components of the neurogenic niche in order to elucidate the complexity of the mechanisms underlying the modulatory properties of this peptide.

Introduction

In adult tissues, stem cells reside in a permissive and specialized microenvironment, or niche, in which different molecular signals coming from the external environment, together with feedback signals from progeny to parent cells, tightly regulate self-renewal, multipotency and stem cell fate (for review see Hsu and Fuchs, 2012). In this regard, many findings underlie the key role played by neurotransmitters on stem cell biology in niches located both inside and outside the central nervous system (CNS; for review see Katayama et al., 2006; Riquelme et al., 2008). Cross-species comparative analysis points out that it could be included in a more general and evolutionary old function, going beyond their role in inter-neuronal communication (for review see Berg et al., 2013). Among them, neuropeptides, molecules released both by neurons, as co-transmitters, and by many additional release sites (for review see van den Pol, 2012), are emerging as important mediators for signaling in both neurogenic and non-neurogenic stem cell niches (for review see Oomen et al., 2000; Louridas et al., 2009; Zaben and Gray, 2013), thus representing possible shared signaling molecules in their biological dynamics.

One of the most abundant neuropeptides in the CNS is neuropeptide Y (NPY), a 36-amino-acid polypeptide that is highly conserved during phylogenesis (Larhammar et al., 1993). Through its ability to modify its levels and expression pattern following environmental changes in both physiological and pathological conditions (Scharfman and Gray, 2006; Zhang et al., 2014), it is involved in many different functions, both inside and outside the CNS. These functions are performed by binding to different G-coupled NPY receptors distributed in different organs (Pedrazzini et al., 2003).

In peripheral organs, NPY can be found in sympathetic nerves, where its release mediates vasoconstrictive effects, in adrenal medulla and in platelets (for review see Hirsch and Zukowska, 2012). NPY takes part in cardiovascular and metabolic response to stress (for review see Hirsch and Zukowska, 2012), in coronary heart disease and hypertension (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1993). More recently, the NPY-induced modulation of different stem cell niches has been highlighted. A direct role in adipogenesis has been indicated (Kuo et al., 2007; Park et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), as well as its angiogenic properties, which have been widely described in different tissues (Ekstrand et al., 2003; Zukowska et al., 2003). The NPY system is also crucially involved in the regulation of the osteogenic niche, where its presence is due to both local production and release from NPY-immunoreactive fibers, and it plays a pivotal function in the neuro-osteogenic network that regulates bone homeostasis (Franquinho et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010, 2011).

Within the CNS, NPY is a major regulator of food consumption and energy homeostasis (for review see Lin et al., 2004), acts as one of the crucial players of the stress-related mechanisms (for review see Hirsch and Zukowska, 2012), and participates in anxiety, memory processing and cognition (for review see Decressac and Barker, 2012). It is also involved in the pathogenesis of several neurologic diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease (revised by Decressac and Barker, 2012) and temporal lobe epilepsy (Marksteiner et al., 1989, 1990; Vezzani and Sperk, 2004), in which anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects have also been observed (for reviews see Vezzani et al., 1999; Vezzani and Sperk, 2004; Gray, 2008; Decressac and Barker, 2012; Malva et al., 2012). At the cellular level, it is either co-released locally by GABAergic interneurons (for review see Sperk et al., 2007; Karagiannis et al., 2009) or comes from the blood by diffusion across the blood-brain barrier (Kastin and Akerstrom, 1999). It modulates excitatory neurotransmission and regulates hyperexcitability, particularly in the hippocampus (Baraban et al., 1997). The Y1, Y2 and Y5 receptors (Y1R, Y2R, Y5R) exhibit specific distribution patterns within the CNS (Parker and Herzog, 1999; Xapelli et al., 2006) and mediate the wide range of NPY physiological functions (Pedrazzini et al., 2003).

Due to the involvement of the NPY system in many of the numerous physiological (e.g., physical activity and learning), and/or pathological stimuli (e.g., stress, seizures, neurodegenerative diseases) (Redrobe et al., 2004; Vezzani and Sperk, 2004; Decressac and Barker, 2012; Hirsch and Zukowska, 2012; Jiang et al., 2014) that strictly regulate the biological dynamics of the neurogenic niche (Kempermann et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2008), its role in the modulation of adult neurogenesis appears particularly relevant (for review see Gray, 2008; Decressac and Barker, 2012; Malva et al., 2012; Zaben and Gray, 2013).

Interestingly, NPY-responsive cells in the CNS are known as not being confined to neurons, but they also include astrocytes (Hösli and Hösli, 1993; Barnea et al., 1998; Ramamoorthy and Whim, 2008; Santos-Carvalho et al., 2013), oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Howell et al., 2007), microglia (Ferreira et al., 2010, 2011) and endothelial cells (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998), which are key components of the specialized microenvironment where adult neurogenesis takes place.

In this context, a comprehensive analysis of relevant data on the NPY-mediated control of adult neurogenesis, focusing on its effects on the different cellular components of the neurogenic niche, could be particularly helpful to improve our understanding of the complex functions of this neuropeptide.

NPY and Neural Stem Cells (NSCs)

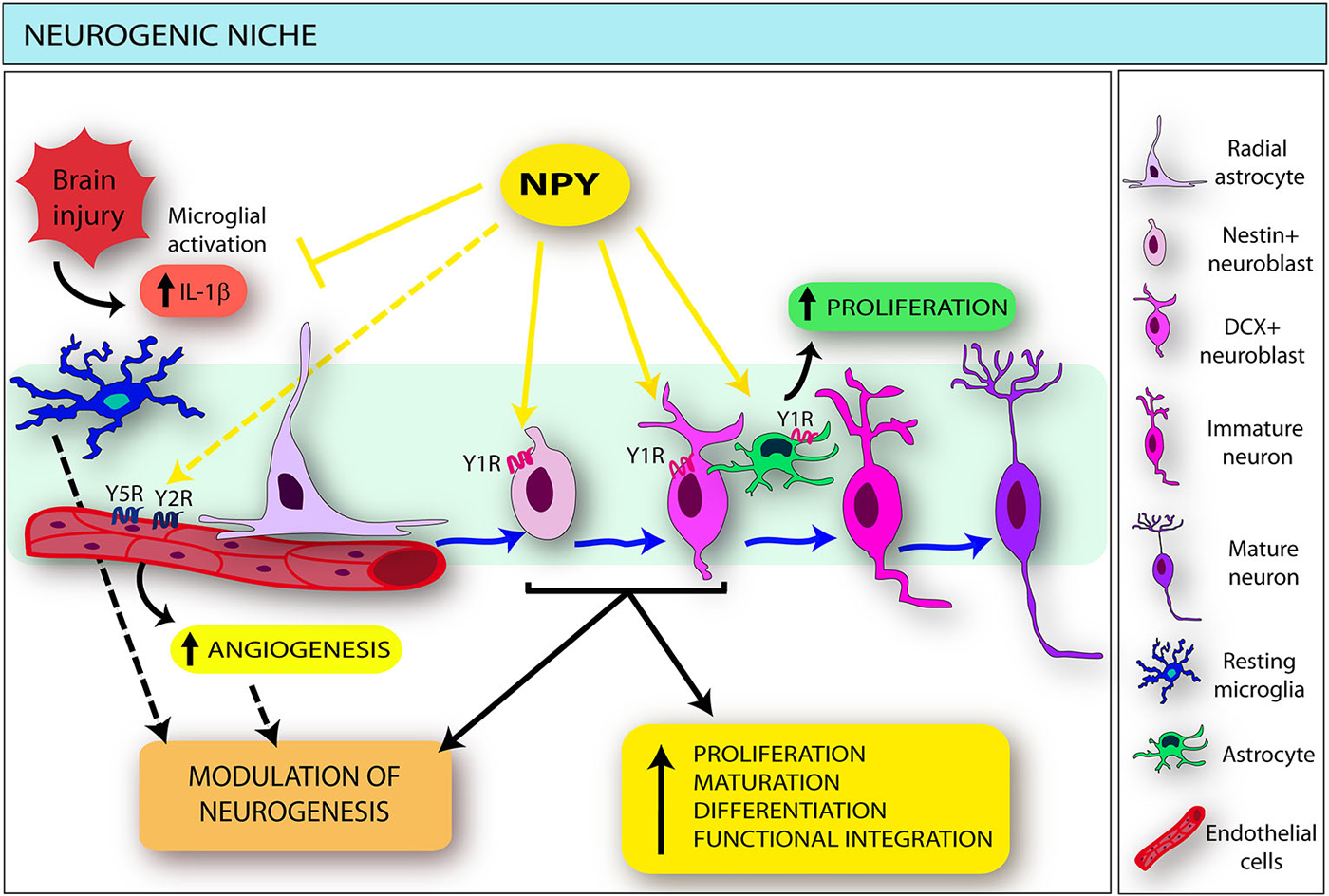

The direct effects of NPY on neural elements of the different neurogenic niches located outside (olfactory epithelium [OE] and retina) or inside the CNS (subventricular zone [SVZ], subcallosal zone [SCZ], subgranular zone [SGZ]) have been widely studied (Figure 1). The proximity to anatomical elements releasing NPY and the stem cell expression of Y1R, as also described in the adipogenic and osteogenic niches (Togari, 2002; Lundberg et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2014), are common elements.

Figure 1. Schematic drawing indicating the main effects exerted by neuropeptide Y (NPY) on the different components of the neurogenic niche. NPY, released by different sources in both physiological and pathological conditions, directly targets selected neural stem cell (NSC) subtypes (namely nestin- and doublecortin [DCX]-positive cells), inducing proliferation, differentiation, migration and functional integration of newly-born neurons. NPY also modulates microglia functions: through the interaction with the Y1R, it inhibits microglial activation and interleukin (IL)-1beta release. The influence of NPY-microglia interactions in the modulation of neurogenesis (dotted black arrow) may be hypothesized. In addition, NPY stimulates astrocyte proliferation mainly via the Y1 receptors (Y1R). NPY also acts on the endothelium through the Y2 receptors (Y2R), in cooperation with the Y5 receptors (Y5R): consequently a direct effect on the endothelial component of the neurogenic niche could be hypothesized (dotted yellow arrow), resulting in increased angiogenesis and possible modulation of endogenous neurogenesis (dotted black arrow).

Effects of NPY on the OE Niche

The vulnerability of olfactory sensory neurons to different environmental factors and the crucial role of the sense of smell in mammalian daily life account for neurogenesis in the OE; as the OE is accessible in living adult humans, it also offers a source of cells useful for understanding the biology of adult neurogenesis in health and disease (Mackay-Sim, 2010).

Hansel et al. provided the first evidence of a proliferative role of NPY on NSCs (namely basal cells) of the OE (Hansel et al., 2001), where the peptide is locally produced by the ensheathing cells of olfactory axon bundles and by sustentacular non-neuronal cells (Ubink et al., 1994).

Experiments performed using transgenic animals and primary olfactory cultures have shown that this effect is mediated by the Y1R (Hansel et al., 2001; Doyle et al., 2008) and involves Protein Kinase C and ERK1/2 pathways, which are ultimately involved in regulating the expression of genes involved in controlling cell proliferation and differentiation (Hansel et al., 2001). NPY release is regulated by ATP, which is constitutively expressed by the OE and preferentially released on injury, and the consequent activation of P2 purinergic receptors (Kanekar et al., 2009; Jia and Hegg, 2012). A role of NPY in the maturation and survival of olfactory receptor neurons has also been proposed (Doyle et al., 2012).

Effects of NPY on the Retinal Niche

Many findings suggest the presence of a regenerative potential within the mammalian retina, in which Muller astrocytes, that are responsible for the homeostatic and metabolic support of retinal neurons, appear capable of proliferating and giving rise to neuronal cells in response to retinal damage (for review see Lin et al., 2014). Both NPY and NPY receptors (Y1R, Y2R and Y5R) are expressed by the different retinal cellular subpopulations, namely neurons, astrocytes, microglia and endothelial cells (Alvaro et al., 2007; Santos-Carvalho et al., 2014). Interestingly, in vitro experiments in Muller cell primary cultures pointed out a modulatory role of NPY on cell proliferation: at low dose it negatively affects the proliferation rate of the cells, while at high doses it increases cell proliferation through the Y1R stimulation and consequent activation of the p44/p42 MAPKs, p38 MAPK and PI3K (Milenkovic et al., 2004). The NPY-mediated proliferative effect has been confirmed in experiments on retinal primary cultures, which revealed that NPY-treatment stimulates retinal neural cell proliferation, through nitric oxide (NO)-cyclic GMP and ERK 1/2 pathways via Y1R, Y2R and Y5R (Alvaro et al., 2008).

Effects of NPY on SGZ

Within the dentate gyrus (DG) NPY is selectively released by GABAergic interneurons located in the hilus, which innervate the granule cell layer in close proximity to the SGZ (for review see Sperk et al., 2007); a physiological role for NPY in the regulation of dentate neurogenesis can therefore be hypothesized. The pro-neurogenic role of NPY on hippocampal NSCs has been evidenced both in vitro (Howell et al., 2003, 2005, 2007) and in vivo (Decressac et al., 2011). In vitro evidence suggests a purely proliferative effect (Howell et al., 2007; Gray, 2008), specifically involving the Y1R, which is mediated by the intracellular NO pathway, through NO/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/cGMP-dependent protein kinase (Cheung et al., 2012), ultimately culminating in the activation of ERK1/2 signaling (Howell et al., 2003; Cheung et al., 2012). Interestingly, in line with the results obtained in the retinal niche (Alvaro et al., 2008), the role of NPY in the modulation of another signaling pathway driving a complex modulation of NSC activities emerges. It is well known, in fact, that NO exerts a dual influence on neurogenesis, depending on the source (for review see Carreira et al., 2012): while intracellular NO is pro-neurogenic, the extracellular form exerts a negative effect (Luo et al., 2010). In this respect the Y1R has also been proposed as a key target in the selective promotion of NO-mediated enhancement of dentate neurogenesis (Cheung et al., 2012).

Decressac et al. confirmed, by in vivo administration of exogenous NPY in both wild type and Y1R knock out mice, that NPY-sensitive cells are the transit amplifying progenitors expressing nestin and doublecortin (DCX), which selectively express the Y1R (Decressac et al., 2011), as also evidenced in vitro (Howell et al., 2003; Figure 1). A preferential differentiation of newly generated cells towards a neuronal lineage has also been reported (Decressac et al., 2011). In this regard, it is worth emphasizing the role also played by NPY in seizure-induced dentate neurogenesis. Studies on NPY−/− mice show a significant reduction in bromodeoxyuridine incorporation in the DG after kainic acid administration (Howell et al., 2007). Interestingly, the DCX-positive cells, besides being selective targets of NPY, are one of the most important neuroblast subpopulations recruited in seizure-induced neurogenesis (Jessberger et al., 2005). These findings are in line with the notion that different neural progenitor subpopulations within the niche show different sensitivity to physiological and/or pathological stimuli (Kempermann et al., 2004; Fabel and Kempermann, 2008), thus representing selective targets for potential drugs aimed at modulating endogenous neurogenesis, of which NPY appears to be a possible candidate.

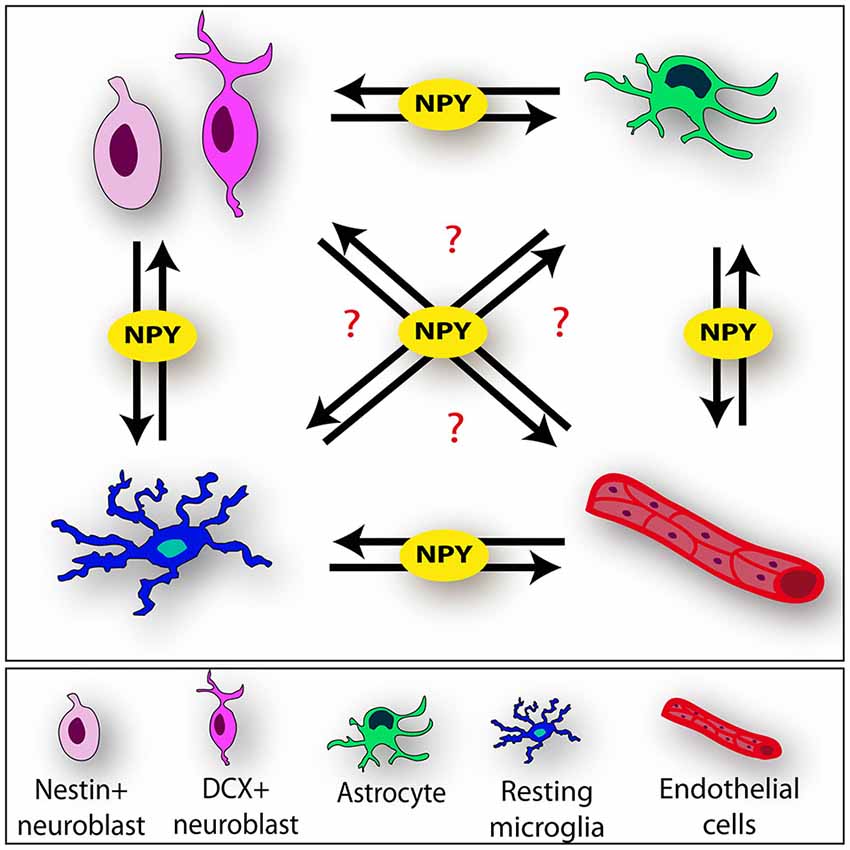

Exogenous NPY has been administered in the Trimethyltin (TMT)-induced model of hippocampal neurodegeneration and temporal lobe epilepsy, in which selective pyramidal cell loss in hippocampal CA1/CA3 subfields (Geloso et al., 1996, 1997), reactive astrogliosis and microglial activation (for review see Geloso et al., 2011; Corvino et al., 2013; Lattanzi et al., 2013) are associated with injury-induced neurogenesis (Corvino et al., 2005). NPY injection in TMT-treated rats results in long-term effects on the hippocampal neurogenic niche, culminating in the functional integration of newly generated neurons into the local circuit (Corvino et al., 2012, 2014). The early events following NPY administration are characterized by the up-regulation of genes involved in different aspects of NSC dynamics. In particular, Noggin, which participates in self-renewal processes (Bonaguidi et al., 2008), Sox-2 and Sonic hedgehog, both involved in the establishment and maintenance of the hippocampal niche (Favaro et al., 2009), NeuroD1, which regulates differentiation and maturation processes (Roybon et al., 2009), Doublecortin, a driver of neuroblast migration (Nishimura et al., 2014) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in different aspects of dentate neurogenesis (Noble et al., 2011), have all been reported to be significantly modulated within the first 24 h following treatment with NPY (Corvino et al., 2012, 2014). These findings suggest that in vivo NPY administration, in association with the peculiar changes in the microenvironment induced by the ongoing neurodegeneration, may trigger a complex mechanism that goes beyond a mere proliferative effect. It can be speculated that it occurs as the result of NPY’s effect on both neural and non-neural elements of the niche and/or as a consequence of multiple cell-cell interactions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) mediates cell-cell interactions within the neurogenic niche. NPY may be involved as key player of the complex communication process among the different components of the niche (neural stem cell [NSCs], microglia, astrocytes and endothelium) (black arrows).

Effects of NPY on SVZ

In the SVZ, the most abundant reservoir of NSCs in the human brain (Doetsch, 2003b; Lim and Alvarez-Buylla, 2014), NPY comes from the cerebrospinal fluid, together with other nutrients and growth factors (Hou et al., 2006). Dense NPY-positive networks also surround this region (Stanic et al., 2008; Thiriet et al., 2011). NPY is also locally expressed by a subset of subependymal cells (Curtis et al., 2005) and by immature neural progenitors, thus suggesting a role as an autocrine/paracrine factor in the control of SVZ neurogenesis (Thiriet et al., 2011).

The effects of the peptide on the SVZ neurogenic niche have been assessed by both in vitro (Agasse et al., 2008; Thiriet et al., 2011) and in vivo studies (Stanic et al., 2008; Decressac et al., 2009). Also in this case the pro-neurogenic role of NPY is essentially played by the Y1R (Agasse et al., 2008; Stanic et al., 2008; Thiriet et al., 2011), which is mainly expressed by DCX-positive neuroblasts in adult mice (Stanic et al., 2008; Figure 1) and in Sox2 and nestin-positive cells in the developing rat (Thiriet et al., 2011). Consistently with the reported effects on dentate and olfactory NSCs, the Y1R mediates a proliferative effect, via phosphorylation of ERK MAP kinases p42 and p44 (Thiriet et al., 2011). The involvement of stress-activated protein kinase/JNK pathways, considered to play an important role in neural differentiation and maturation, has also been reported (Agasse et al., 2008).

It is well known that, while sharing common regulators, the different neurogenic niches may show some differences in specific aspects, including cellular organization, neuronal subtype differentiation and migration of NSCs (Ming and Song, 2011). In this regard, some discrepancies with the SGZ have emerged: in the SVZ, in fact, NPY appears also to exert a direct role on cell migration (Decressac et al., 2009; Thiriet et al., 2011) and neuronal differentiation (Agasse et al., 2008; Decressac et al., 2009), while a mere proliferative role, without instructive signals to differentiation processes, emerged from in vitro studies on SGZ NSCs (Howell et al., 2007). In particular, in vivo administration of NPY in adult wild type mice showed that the newly generated neurons migrate not only to the olfactory bulb, but also towards the striatum, where they preferentially differentiate into GABAergic neurons (Decressac et al., 2009). Experiments performed on Y1R knock out mice indicated that they show a disrupted assembly of neuroblasts in the rostral migratory stream, compared with the chain-like organization present in wild type animals (Stanic et al., 2008), suggesting a role of this receptor also in cell migration. The direct demonstration of a chemokinetic effect of NPY through Y1R activation and MAPK ERK1/2 pathway recruitment in NSCs, was finally given by Thiriet et al. on rat SVZ neurospheres (Thiriet et al., 2011). The possible involvement of the Y2R has also been suggested, since Y2R null mice express a reduced number of migratory neuroblasts in both the SVZ and the rostral migratory stream, with a consequently reduced number of interneurons in the olfactory bulb (Stanic et al., 2008). It should be noted, however, that the Y2R protein was found only in close proximity to rostral migratory stream associated neuroblasts, without evidence of positivity in NSCs and/or astroglial cells (Stanic et al., 2008).

Many neurodegenerative diseases induce changes in SVZ neurogenesis (Curtis et al., 2007). Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, for instance, are accompanied by a reduction in NSC proliferation, while stroke and Huntington’s disease cause an enhancement of SVZ neurogenesis, resulting in an increased number of new neurons, which also migrate into damaged areas (Curtis et al., 2007). Consequently, NPY administration may be of potential interest in cell replacement-based strategies for neurodegenerative diseases affecting SVZ neurogenesis. Decressac et al. demonstrated that NPY administration in the R6/2 model of Huntington disease is able to attenuate striatal atrophy and to induce a proliferative effect on SVZ NSCs (Decressac et al., 2010). However, it did not result in an increased number of newly generated neurons migrating within the striatum. NPY administration was also ineffective in modulating dentate neurogenesis in R6/2 mice. Interestingly, a reduced expression of NPY in the hilus of R6/2 mice was observed, accompanied by a reduction in the number of Y1R positive cells in the DG, thus suggesting that alterations in the NPY system might contribute to the impairment of neurogenesis in this model of Huntington disease (Decressac et al., 2010).

Effects of NPY on SCZ

NPY also exerts its proliferative role in the SCZ, a caudal extension of the SVZ lying between the hippocampus and the corpus callosum that, in basal conditions, essentially generates oligodendrocytes migrating into the corpus callosum (Seri et al., 2006). Acting through the Y1R on nestin-positive cells (Howell et al., 2007), NPY is involved in basal and seizure-induced SCZ progenitor cell proliferation (Howell et al., 2007; Laskowski et al., 2007). Interestingly, SCZ activity appears to be modulated by seizures, resulting in the production of glial progenitors that migrate to the injured hippocampus (Parent et al., 2006), thus raising the intriguing possibility that NPY modulates SCZ oligodendrogliogenesis as well as neurogenesis (Gray, 2008).

NPY and Microglia

Increasing evidence suggests that microglia play a relevant role in the neurogenic niche: unchallenged microglia contribute, through their phagocytic activity, to the maintenance of homeostasis of the neurogenic processes (Sierra et al., 2010), while the different functional phenotypic profiles that microglial cells undergo as a response to microenvironmental changes appear to have a dual role in neurogenesis (Carreira et al., 2012; Kettenmann et al., 2013; Su et al., 2014). Much evidence indicates how the pro-inflammatory cytokines released by activated microglia, such as interleukin (IL)-1beta, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and IL-6, detrimentally affect neurogenesis (Ekdahl et al., 2003; Ekdahl, 2012; Su et al., 2014). On the other hand, in an enriched environment, activated microglia show proneurogenic properties via increased expression of insulin growth factor-1 (Ziv et al., 2006), while, in the presence of T-helper dependent cytokines, they reduce the production of TNF-alpha (Butovsky et al., 2006). In other words, the regulatory function of microglia in neurogenesis seems to be essentially dependent on differences in instructive signals coming from the microenvironment (Ekdahl et al., 2009).

Many studies support the modulatory role of NPY in the immune system, with effects ranging from the modulation of cell migration to macrophage and T helper cell differentiation, cytokine release, natural killer cell activity and phagocytosis, most likely through its Y1R (for review see Hirsch and Zukowska, 2012; Dimitrijević and Stanojević, 2013).

Recent findings also indicate direct interactions between NPY and microglia, the innate defensive system in the CNS (Kettenmann et al., 2013). Ferreira et al. observed that NPY, acting via the Y1R, inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and reduces the associated release of IL-1beta (Ferreira et al., 2010). This effect is mediated by NPY-induced impairment of NO synthesis and reduced inducible form of nitric oxide synthase expression (Ferreira et al., 2010). In addition, NPY also induces impairment of the phagocytic properties of activated microglia (Ferreira et al., 2011) and IL-1beta-induced microglial motility (Ferreira et al., 2012). Taken together, these observations point to the key role played by the peptide in modulating the functional activities of microglia, and consequent release of mediators during inflammation (Figure 1).

Although most of these findings were obtained in in vitro systems, so that further research is needed in order to elucidate whether these interactions produce the same regulatory responses in vivo, a relevant influence of NPY-microglia interactions in the homeostasis of the neurogenic niche may be inferred. Because of the influence exerted by neuroinflammation on neurogenesis (Carreira et al., 2012), NPY-microglia signaling could be particularly relevant in the modulation of injury-induced neurogenesis. Studies exploring the interaction between neuroinflammation and neurogenesis lead to the hypothesis that the early detrimental action of microglia after acute neuronal damage can, in some situations, be modified into a supportive state during the chronic phase (Ekdahl et al., 2009) and NPY could be involved in the modulation of these transient properties of activated microglia. Many findings emphasize the ability of NSCs to modulate their own environment through the release of signaling factors (Klassen et al., 2003; Butti et al., 2014) and mutual interaction between NSCs and microglia have been shown by recent research (Mosher et al., 2012). In this regard, we may speculate that NPY, released by NSCs or coming from the surrounding environment, could be critically involved in this process, acting as a paracrine/autocrine factor which modulates both the state of activation of microglial cells and their interactions with NSCs (Figure 2).

NPY and Astrocytes

Astrocytes are complex cells, whose supporting roles in the healthy CNS includes the regulation of blood flow, the modulation of synaptic function and plasticity and maintenance of the extracellular balance of ions and transmitters (Sofroniew, 2009). They also act as important regulators of the niche environment, through the secretion of diffusible factors (Lie et al., 2005; Barkho et al., 2006; Lu and Kipnis, 2010; Barkho and Zhao, 2011; Wilhelmsson et al., 2012) or through membrane-associated molecules (Barkho and Zhao, 2011). Thanks to their peculiar position between endothelial cells and neurons, astrocytes can mediate the exchange of molecules between vascular and neural compartments (Parpura et al., 2012). In addition, a specific subpopulation of astrocytes, the radial astrocytes, directly generates migrating neuroblasts, via rapidly dividing transit-amplifying cells (Seri et al., 2001; Doetsch, 2003a).

Several studies indicate that the expression of NPY and NPY receptors (namely Y1R) is also extended to some astrocyte subpopulations (Barnea et al., 1998, 2001; St-Pierre et al., 2000), including retinal astrocytes (Alvaro et al., 2007). It has been shown that astrocytes, like neurons, are able to synthesize NPY and show a regulated secretory pathway that is responsible for the release of multiple classes of transmitter molecules: in this regard, the activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors results in a calcium-dependent fusion of NPY-containing dense-core granules with the cell membrane and consequent peptide secretion (Ramamoorthy and Whim, 2008). It has been suggested that this process may be controlled by the RE-1–silencing transcription factor, the same factor that regulates neurosecretion in neurons (Prada et al., 2011). The expression of NPY in astrocytes is controlled by several factors: the post-natal down-regulation of glial peptide transcripts has been reported, as well as its up-regulation in adult astrocytes after brain injury (Ubink et al., 2003).

Interestingly, the in vivo intracerebroventricular administration of NPY significantly increases the proliferation not only of neuroblasts but also of astrocytes within the SVZ, mainly via the Y1R (Decressac et al., 2009; Figure 1). These findings delineate a complex scenario in which the peptide could exert its influence and, although direct evidence is still lacking, a role of NPY-gliotransmission in the modulation of critical steps of adult neurogenesis may be hypothesized, in both physiological and pathological conditions. In particular, it has been reported that the expression of astrocytic NPY also appears to be modulated in a cytokine-specific manner: in this regard, a relevant role of fibroblast growth factor (Barnea et al., 1998) and IL-beta (Barnea et al., 2001) in astrocytic NPY upregulation has emerged in in vitro studies. Both these factors can be released by astrocytes as well as by microglia: since, as previously reported, NPY inhibits microglial production of IL-1beta and IL-1beta-induced phagocytosis (Ferreira et al., 2011, 2012), a role of the peptide in astroglial/microglial interplay could be speculated. It is conceivable that it may be involved in the astrocytic regulation of microglial differentiation and activation, which, in turn, differently affect neurogenesis.

In addition, it has been reported that NPY increases the proliferative effect of the astrocyte-derived growth factor fibroblast growth factor-2 on NSCs, through the increased expression of fibroblast growth factor-receptor 1 on granule cell precursors (Rodrigo et al., 2010). This observation indicates the involvement of NPY also in the neuron-glial crosstalk and further reinforces the hypothesis that it could be one of the molecules significantly involved in the mutual interactions among the different components of the niche (Figure 2).

NPY and the Endothelium

The vasculature is a critical component of the neurogenic niche, and endothelial cells closely interact with NSCs to form “neurovascular niches”, contributing to the regulation and maintenance of the niche (Palmer et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2004, 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2008; Goldberg and Hirschi, 2009; for review Goldman and Chen, 2011).

The molecular cross-talk between NSCs and endothelial cells is mediated by diffusible factors secreted by endothelial cells, such as BDNF and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as well as by cell-cell contact (Leventhal et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2004, 2008; Snapyan et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2010; for review Goldman and Chen, 2011; Vissapragada et al., 2014). Although the characterization of NPY receptors in the cerebral endothelium has not been fully clarified (Abounader et al., 1999; You et al., 2001), much evidence suggests that the endothelium could represent one of the sources, as well as one of the targets, of this peptide (Silva et al., 2005).

In this regard, different subtypes of human and rodent peripheral endothelial cells are now known to synthesize, store and constitutively express some elements of the NPY system, such as NPY itself, the Y1R and Y2R and the dipeptidyl peptidase IV, enzyme which converts NPY from the Y1R ligand to a selective agonist of Y2R (Loesch et al., 1992; Sanabria and Silva, 1994; Jackerott and Larsson, 1997; Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998; Ghersi et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003a; Nan et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2005; Movafagh et al., 2006; Abdel-Samad et al., 2007). NPY also acts on the endothelium, promoting angiogenesis, mainly via the Y2R, in cooperation with the Y5R (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998; Zukowska et al., 2003; Ekstrand et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003a; Pons et al., 2004; Movafagh et al., 2006). VEGF- and NO-dependent pathways are primarily involved (You et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003b). The hypothesis that the endothelium may represent a non-neural store of NPY, where it acts in an autocrine and in a paracrine manner, has also been proposed (Silva et al., 2005).

The angiogenic action of NPY has been confirmed in several in vitro and in vivo models: using specific receptor antagonist or transgenic Y2R knockout mice, these studies reinforced the primary role of the Y2R in mediating NPY’s angiogenic response (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998; Ghersi et al., 2001; Ekstrand et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003a,b; Movafagh et al., 2006; Figure 1).

NPY also appears to exert a relevant role in the regulation and stimulation of angiogenesis in pathological processes and tissue repair, as evidenced in in vivo models of peripheral limb ischemia (Grant and Zukowska, 2000; Lee et al., 2003b; Tilan et al., 2013), skin wound repair (Ekstrand et al., 2003) and oxygen-induced retinopathy (Yoon et al., 2002), in which both exogenous and/or endogenous (released from neural and non-neural stores) NPY significantly contribute to tissue revascularization.

Angiogenesis and neurogenesis are related processes, as evidenced by data showing that cerebral endothelial cells activated by ischemia promote proliferation and differentiation of NSCs, while neural progenitor cells isolated from the ischemic SVZ promote angiogenesis (Teng et al., 2008). In this regard, it has also been shown that both angiogenesis and the expression of pro-angiogenic factors exert important functions in different stages of neurogenesis, such as proliferation, migration and survival (Jin et al., 2002; Louissaint et al., 2002). Interestingly, among these molecules, a relevant role is played by NO signaling, which regulates both angiogenesis and neurogenesis (Carreira et al., 2013), and whose activity is modulated by NPY not only in endothelial cells (You et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003b), but also in NSCs (Cheung et al., 2012) and microglia (Ferreira et al., 2012).

It may be speculated that NPY, possibly released from the endothelium, acts as a diffusible factor that could influence and modulate elements of the neurovascular niche (Figure 2).

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

In summary, existing data provide evidence that NPY modulates the neurogenic niche performing a pro-neurogenic role directly on the NSCs, while the possibility of a concomitant modulatory action on astrocytes, microglia and endothelium activities within the niche is also possible. The involvement of NPY as a key player in the complex process of communication among the different components of the niche may be speculated, and, in this regard, there is evident need for further research to definitely elucidate the mechanisms of NPY-modulated cell/cell interactions. This could yield a more heightened understanding of some critical steps of the complex mechanisms that regulate adult neurogenesis, thus possibly providing knowledge useful to identify selective targets for potential drugs aimed at modulating NSC fate. Moreover, due to the significant involvement of the NPY system also in non-neural stem cell niches, this information could contribute to clarify the systemic role of the peptide, which appears to be involved in a set of basic homeostatic body functions, ranging from food consumption and energy homeostasis to the regulation of stem cell biology in adult tissues.

Authors and Contributors

MCG: She gave substantial contributions to both the conception and design of the work; she contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. She drafted the work and revised it critically. She gave the final approval of the version to be published. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

VC: She gave substantial contributions to the design of the work; she contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. She drafted the work and revised it critically. She gave the final approval of the version to be published. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

VDM: She contributed to the acquisition of data for the work. She drafted the work. She gave the final approval of the version to be published. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

EM: She contributed to the acquisition of data for the work. She drafted the work. She gave the final approval of the version to be published. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

FM: He provided substantial contributions to the design of the work; he contributed to the interpretation of data for the work. He revised critically the work. He gave the final approval of the version to be published. He agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The professional English style of Margaret Wayne is gratefully acknowledged.

References

Abdel-Samad, D., Jacques, D., Perreault, C., and Provost, C. (2007). NPY regulates human endocardial endothelial cell function. Peptides 28, 281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.09.028

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abounader, R., Elhusseiny, A., Cohen, Z., Olivier, A., Stanimirovic, D., Quirion, R., et al. (1999). Expression of neuropeptide Y receptors mRNA and protein in human brain vessels and cerebromicrovascular cells in culture. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 19, 155–163. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199902000-00007

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Agasse, F., Bernardino, L., Kristiansen, H., Christiansen, S. H., Ferreira, R., Silva, B., et al. (2008). Neuropeptide Y promotes neurogenesis in murine subventricular zone. Stem Cells 26, 1636–1645. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0056

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alvaro, A. R., Martins, J., Araújo, I. M., Rosmaninho-Salgado, J., Ambrósio, A. F., and Cavadas, C. (2008). Neuropeptide Y stimulates retinal neural cell proliferation–involvement of nitric oxide. J. Neurochem. 105, 2501–2510. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05334.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alvaro, A. R., Rosmaninho-Salgado, J., Santiago, A. R., Martins, J., Aveleira, C., Santos, P. F., et al. (2007). NPY in rat retina is present in neurons, in endothelial cells and also in microglial and Müller cells. Neurochem. Int. 50, 757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.01.010

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baraban, S. C., Hollopeter, G., Erickson, J. C., Schwartzkroin, P. A., and Palmiter, R. D. (1997). Knock-out mice reveal a critical antiepileptic role for neuropeptide Y. J. Neurosci. 17, 8927–8936.

Barkho, B. Z., Song, H., Aimone, J. B., Smrt, R. D., Kuwabara, T., Nakashima, K., et al. (2006). Identification of astrocyte-expressed factors that modulate neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 15, 407–421. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.407

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barkho, B. Z., and Zhao, X. (2011). Adult neural stem cells: response to stroke injury and potential for therapeutic applications. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 6, 327–338. doi: 10.2174/157488811797904362

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barnea, A., Aguila-Mansilla, N., Bigio, E. H., Worby, C., and Roberts, J. (1998). Evidence for regulated expression of neuropeptide Y gene by rat and human cultured astrocytes. Regul. Pept. 75–76, 293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00081-0

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barnea, A., Roberts, J., Keller, P., and Word, R. A. (2001). Interleukin-1beta induces expression of neuropeptide Y in primary astrocyte cultures in a cytokine-specific manner: induction in human but not rat astrocytes. Brain Res. 896, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02141-2

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Berg, D. A., Belnoue, L., Song, H., and Simon, A. (2013). Neurotransmitter-mediated control of neurogenesis in the adult vertebrate brain. Development 140, 2548–2561. doi: 10.1242/dev.088005

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bonaguidi, M. A., Peng, C. Y., McGuire, T., Falciglia, G., Gobeske, K. T., Czeisler, C., et al. (2008). Noggin expands neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 28, 9194–9204. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3314-07.2008

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Butovsky, O., Ziv, Y., Schwartz, A., Landa, G., Talpalar, A. E., Pluchino, S., et al. (2006). Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 31, 149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Butti, E., Cusimano, M., Bacigaluppi, M., and Martino, G. (2014). Neurogenic and non-neurogenic functions of endogenous neural stem cells. Front. Neurosci. 8:92. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00092

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carreira, B. P., Carvalho, C. M., and Araújo, I. M. (2012). Regulation of injury-induced neurogenesis by nitric oxide. Stem Cells Int. 2012:895659. doi: 10.1155/2012/895659

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carreira, B. P., Morte, M. I., Lourenço, A. S., Santos, A. I., Inácio, A., Ambrósio, A. F., et al. (2013). Differential contribution of the guanylyl cyclase-cyclic GMP-protein kinase G pathway to the proliferation of neural stem cells stimulated by nitric oxide. Neurosignals 21, 1–13. doi: 10.1159/000332811

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, S. H., Fung, P. C., and Cheung, R. T. (2002). Neuropeptide Y-Y1 receptor modulates nitric oxide level during stroke in the rat. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 32, 776–784. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00774-8

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cheung, A., Newland, P. L., Zaben, M., Attard, G. S., and Gray, W. P. (2012). Intracellular nitric oxide mediates neuroproliferative effect of neuropeptide y on postnatal hippocampal precursor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20187–20196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m112.346783

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corvino, V., Geloso, M. C., Cavallo, V., Guadagni, E., Passalacqua, R., Florenzano, F., et al. (2005). Enhanced neurogenesis during trimethyltin-induced neurodegeneration in the hippocampus of the adult rat. Brain Res. Bull. 65, 471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.02.031

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corvino, V., Marchese, E., Giannetti, S., Lattanzi, W., Bonvissuto, D., Biamonte, F., et al. (2012). The neuroprotective and neurogenic effects of neuropeptide Y administration in an animal model of hippocampal neurodegeneration and temporal lobe epilepsy induced by trimethyltin. J. Neurochem. 122, 415–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07770.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corvino, V., Marchese, E., Michetti, F., and Geloso, M. C. (2013). Neuroprotective strategies in hippocampal neurodegeneration induced by the neurotoxicant trimethyltin. Neurochem. Res. 38, 240–253. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0932-9

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corvino, V., Marchese, E., Podda, M. V., Lattanzi, W., Giannetti, S., Di Maria, V., et al. (2014). The neurogenic effects of exogenous neuropeptide Y: early molecular events and long-lasting effects in the hippocampus of trimethyltin-treated rats. PLoS One 9:e88294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088294

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Curtis, M. A., Faull, R. L., and Eriksson, P. S. (2007). The effect of neurodegenerative diseases on the subventricular zone. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 712–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn2216

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Curtis, M. A., Penney, E. B., Pearson, J., Dragunow, M., Connor, B., and Faull, R. L. (2005). The distribution of progenitor cells in the subependymal layer of the lateral ventricle in the normal and Huntington’s disease human brain. Neuroscience 132, 777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.051

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Decressac, M., and Barker, R. A. (2012). Neuropeptide Y and its role in CNS disease and repair. Exp. Neurol. 238, 265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.004

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Decressac, M., Prestoz, L., Veran, J., Cantereau, A., Jaber, M., and Gaillard, A. (2009). Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation, migration and differentiation of neural precursors from the subventricular zone in adult mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.017

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Decressac, M., Wright, B., David, B., Tyers, P., Jaber, M., Barker, R. A., et al. (2011). Exogenous neuropeptide Y promotes in vivo hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus 21, 233–238. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20765

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Decressac, M., Wright, B., Tyers, P., Gaillard, A., and Barker, R. A. (2010). Neuropeptide Y modifies the disease course in the R6/2 transgenic model of Huntington’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 226, 24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.022

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dimitrijević, M., and Stanojević, S. (2013). The intriguing mission of neuropeptide Y in the immune system. Amino Acids 45, 41–53. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1185-7

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Doetsch, F. (2003a). The glial identity of neural stem cells. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1127–1134. doi: 10.1038/nn1144

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Doetsch, F. (2003b). A niche for adult neural stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.012

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Doyle, K. L., Hort, Y. J., Herzog, H., and Shine, J. (2012). Neuropeptide Y and peptide YY have distinct roles in adult mouse olfactory neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. Res. 90, 1126–1135. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23008

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Doyle, K. L., Karl, T., Hort, Y., Duffy, L., Shine, J., and Herzog, H. (2008). Y1 receptors are critical for the proliferation of adult mouse precursor cells in the olfactory neuroepithelium. J. Neurochem. 105, 641–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05188.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ekdahl, C. T. (2012). Microglial activation-tuning and pruning adult neurogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 3:41. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00041

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ekdahl, C. T., Claasen, J. H., Bonde, S., Kokaia, Z., and Lindvall, O. (2003). Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 100, 13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234031100

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ekdahl, C. T., Kokaia, Z., and Lindvall, O. (2009). Brain inflammation and adult neurogenesis: the dual role of microglia. Neuroscience 158, 1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.052

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ekstrand, A. J., Cao, R., Bjorndahl, M., Nystrom, S., Jonsson-Rylander, A. C., Hassani, H., et al. (2003). Deletion of neuropeptide Y (NPY) 2 receptor in mice results in blockage of NPY induced angiogenesis and delayed wound healing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 100, 6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1135965100

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fabel, K., and Kempermann, G. (2008). Physical activity and the regulation of neurogenesis in the adult and aging brain. Neuromolecular Med. 10, 59–66. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8031-4

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Favaro, R., Valotta, M., Ferri, A. L., Latorre, E., Mariani, J., Giachino, C., et al. (2009). Hippocampal development and neural stem cell maintenance require Sox2-dependent regulation of Shh. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1248–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn.2397

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ferreira, R., Santos, T., Cortes, L., Cochaud, S., Agasse, F., Silva, A. P., et al. (2012). Neuropeptide Y inhibits interleukin-1 beta-induced microglia motility. J. Neurochem. 120, 93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07541.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ferreira, R., Santos, T., Viegas, M., Cortes, L., Bernardino, L., Vieira, O. V., et al. (2011). Neuropeptide Y inhibits interleukin-1β-induced phagocytosis by microglial cells. J. Neuroinflammation 8:169. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-169

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ferreira, R., Xapelli, S., Santos, T., Silva, A. P., Cristóvão, A., Cortes, L., et al. (2010). Neuropeptide Y modulation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced nitric oxide production in microglia. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41921–41934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m110.164020

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Franquinho, F., Liz, M. A., Nunes, A. F., Neto, E., Lamghari, M., and Sousa, M. M. (2010). Neuropeptide Y and osteoblast differentiation-the balance between the neuro-osteogenic network and local control. FEBS J. 277, 3664–3674. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07774.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Geloso, M. C., Corvino, V., and Michetti, F. (2011). Trimethyltin-induced hippocampal degeneration as a tool to investigate neurodegenerative processes. Neurochem. Int. 58, 729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.03.009

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Geloso, M. C., Vinesi, P., and Michetti, F. (1996). Parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons are not affected by trimethyltin-induced neurodegeneration in the rat hippocampus. Exp. Neurol. 139, 269–277. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0100

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Geloso, M. C., Vinesi, P., and Michetti, F. (1997). Calretinin-containing neurons in trimethyltin-induced neurodegeneration in the rat hippocampus: an immunocytochemical study. Exp. Neurol. 146, 67–73. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6491

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ghersi, G., Chen, W., Lee, E. W., and Zukowska, Z. (2001). Critical role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in neuropeptide Y mediated endothelial cell migration in response to wounding. Peptides 22, 453–458. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00340-0

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goldberg, J. S., and Hirschi, K. K. (2009). Diverse roles of the vasculature within the neural stem cell niche. Regen. Med. 4, 879–897. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.61

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goldman, S. A., and Chen, Z. (2011). Perivascular instruction of cell genesis and fate in the adult brain. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1382–1389. doi: 10.1038/nn.2963

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Grant, D. S., and Zukowska, Z. (2000). Revascularization of ischemic tissues with SIKVAV and neuropeptide Y (NPY). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 476, 139–154. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4221-6_12

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gray, W. P. (2008). Neuropeptide Y signalling on hippocampal stem cells in heath and disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 288, 52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.021

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hansel, D. E., Eipper, B. A., and Ronnett, G. V. (2001). Neuropeptide Y functions as a neuroproliferative factor. Nature 410, 940–944. doi: 10.1038/35073601

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hirsch, D., and Zukowska, Z. (2012). NPY and stress 30 years later: the peripheral view. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 32, 645–659. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9793-z

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hösli, E., and Hösli, L. (1993). Autoradiographic localization of binding sites for neuropeptide Y and bradykinin on astrocytes. Neuroreport 4, 159–162. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199302000-00011

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hou, C., Jia, F., Liu, Y., and Li, L. (2006). CSF serotonin, 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid and neuropeptide Y levels in severe major depressive disorder. Brain Res. 1095, 154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.026

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Howell, O. W., Doyle, K., Goodman, J. H., Scharfman, H. E., Herzog, H., Pringle, A., et al. (2005). Neuropeptide Y stimulates neuronal precursor proliferation in the post-natal and adult dentate gyrus. J. Neurochem. 93, 560–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03057.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Howell, O. W., Scharfman, H. E., Herzog, H., Sundstrom, L. E., Beck-Sickinger, A., and Gray, W. P. (2003). Neuropeptide Y is neuroproliferative for post-natal hippocampal precursor cells. J. Neurochem. 86, 646–659. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01895.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Howell, O. W., Silva, S., Scharfman, H. E., Sosunov, A. A., Zaben, M., Shatya, A., et al. (2007). Neuropeptide Y is important for basal and seizure-induced precursor cell proliferation in the hippocampus. Neurobiol. Dis. 26, 174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.014

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hsu, Y. C., and Fuchs, E. (2012). A family business: stem cell progeny join the niche to regulate homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 103–114. doi: 10.1038/nrm3272

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jackerott, M., and Larsson, L. I. (1997). Immunocytochemical localization of the NPY/PYY Y1 receptor in enteric neurons, endothelial cells and endocrine-like cells of the rat intestinal tract. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 45, 1643–1650. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501207

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jessberger, S., Römer, B., Babu, H., and Kempermann, G. (2005). Seizures induce proliferation and dispersion of doublecortin-positive hippocampal progenitor cells. Exp. Neurol. 196, 342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.010

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jia, C., and Hegg, C. C. (2012). Neuropeptide Y and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediate injury-induced neuroregeneration in mouse olfactory epithelium. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 49, 158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.11.004

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jiang, P., Dang, R. L., Li, H. D., Zhang, L. H., Zhu, W. Y., Xue, Y., et al. (2014). The impacts of swimming exercise on hippocampal expression of neurotrophic factors in rats exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014:729827. doi: 10.1155/2014/729827

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jin, K., Zhu, Y., Sun, Y., Mao, X. O., Xie, L., and Greenberg, D. A. (2002). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 99, 11946–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182296499

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kanekar, S., Jia, C., and Hegg, C. C. (2009). Purinergic receptor activation evokes neurotrophic factor neuropeptide Y release from neonatal mouse olfactory epithelial slices. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 1424–1434. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21954

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Karagiannis, A., Gallopin, T., Dávid, C., Battaglia, D., Geoffroy, H., Rossier, J., et al. (2009). Classification of NPY-expressing neocortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 3642–3659. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0058-09.2009

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kastin, A. J., and Akerstrom, V. (1999). Nonsaturable entry of neuropeptide Y into brain. Am. J. Physiol. 276(3 Pt. 1), E479–E482.

Katayama, Y., Battista, M., Kao, W. M., Hidalgo, A., Peired, A. J., Thomas, S. A., et al. (2006). Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell 124, 407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kempermann, G., Jessberger, S., Steiner, B., and Kronenberg, G. (2004). Milestones of neuronal development in the adult hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 27, 447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.013

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kettenmann, H., Kirchhoff, F., and Verkhratsky, A. (2013). Microglia: new roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron 77, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.023

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Klassen, H. J., Imfeld, K. L., Kirov, I. I., Tai, L., Gage, F. H., Young, M. J., et al. (2003). Expression of cytokines by multipotent neural progenitor cells. Cytokine 22, 101–106. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00120-0

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuo, L. E., Kitlinska, J. B., Tilan, J. U., Li, L., Baker, S. B., Johnson, M. D., et al. (2007). Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nat. Med. 13, 803–811. doi: 10.1038/nm1611

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Larhammar, D., Blomqvist, A. G., and Söderberg, C. (1993). Evolution of neuropeptide Y and its related peptides. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 106, 743–752.

Laskowski, A., Howell, O. W., Sosunov, A. A., McKhann, G., and Gray, W. P. (2007). NPY mediates basal and seizure-induced proliferation in the subcallosal zone. Neuroreport 18, 1005–10008. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0b013e32815277ab

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lattanzi, W., Corvino, V., Di Maria, V., Michetti, F., and Geloso, M. C. (2013). Gene expression profiling as a tool to investigate the molecular machinery activated during hippocampal neurodegeneration induced by trimethyltin (TMT) administration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 16817–16835. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816817

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, N. J., Doyle, K. L., Sainsbury, A., Enriquez, R. F., Hort, Y. J., Riepler, S. J., et al. (2010). Critical role for Y1 receptors in mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation and osteoblast activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 1736–1747. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.61

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, E. W., Grant, D. S., Movafagh, S., and Zukowska, Z. (2003a). Impaired angiogenesis in neuropeptide Y (NPY)-Y2 receptorknockout mice. Peptides 24, 99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00281-4

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, E. W., Michalkiewicz, M., Kitlinska, J., Kalezic, I., Switalska, H., Yoo, P., et al. (2003b). Neuropeptide Y induces ischemic angiogenesis and restores function of ischemic skeletal muscles. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1853–1862. doi: 10.1172/jci16929

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, N. J., Nguyen, A. D., Enriquez, R. F., Doyle, K. L., Sainsbury, A., Baldock, P. A., et al. (2011). Osteoblast specific Y1 receptor deletion enhances bone mass. Bone 48, 461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.174

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Leventhal, C., Rafii, S., Rafii, D., Shahar, A., and Goldman, S. A. (1999). Endothelial trophic support of neuronal production and recruitment from the adult mammalian subependyma. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 13, 450–464. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0762

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lie, D. C., Colamarino, S. A., Song, H. J., Désiré, L., Mira, H., Consiglio, A., et al. (2005). Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature 437, 1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lim, D. A., and Alvarez-Buylla, A. (2014). Adult neural stem cells stake their ground. Trends Neurosci. 37, 563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.006

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, S., Boey, D., and Herzog, H. (2004). NPY and Y receptors: lessons from transgenic and knockout models. Neuropeptides 38, 189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.05.005

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, T. C., Hsu, C. C., Chien, K. H., Hung, K. H., Peng, C. H., and Chen, S. J. (2014). Retinal stem cells and potential cell transplantation treatments. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 77, 556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.08.001

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Loesch, A., Maynard, K. I., and Burnstock, G. (1992). Calcitonin gene-related peptide- and neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity in endothelial cells after long term stimulation of perivascular nerves. Neuroscience 48, 723–726. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90415-x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Louissaint, A. Jr., Rao, S., Leventhal, C., and Goldman, S. A. (2002). Coordinated interaction of neurogenesis and angiogenesis in the adult songbird brain. Neuron 34, 945–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00722-5

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Louridas, M., Letourneau, S., Lautatzis, M. E., and Vrontakis, M. (2009). Galanin is highly expressed in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and facilitates migration of cells both in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.064

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, Z., and Kipnis, J. (2010). Thrombospondin 1—A key astrocyte-derived neurogenic factor. FASEB J. 24, 1925–1934. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150573

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lundberg, P., Allison, S. J., Lee, N. J., Baldock, P. A., Brouard, N., Rost, S., et al. (2007). Greater bone formation of Y2 knockout mice is associated with increased osteoprogenitor numbers and altered Y1 receptor expression. J. Biol. Chem. 29, 19082–19091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m609629200

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Luo, C. X., Jin, X., Cao, C. C., Zhu, M. M., Wang, B., Chang, L., et al. (2010). Bidirectional regulation of neurogenesis by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase derived from neurons and neural stem cells. Stem Cells 28, 2041–2052. doi: 10.1002/stem.522

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mackay-Sim, A. (2010). Stem cells and their niche in the adult olfactory mucosa. Arch. Ital. Biol. 148, 47–58.

Malva, J. O., Xapelli, S., Baptista, S., Valero, J., Agasse, F., Ferreira, R., et al. (2012). Multifaces of neuropeptide Y in the brain-neuroprotection, neurogenesis and neuroinflammation. Neuropeptides 46, 299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.09.001

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Marksteiner, J., Ortler, M., Bellmann, R., and Sperk, G. (1990). Neuropeptide Y biosynthesis is markedly induced in mossy fibers during temporal lobe epilepsy of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 112, 143–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90193-d

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Marksteiner, J., Sperk, G., and Maas, D. (1989). Differential increases in brain levels of neuropeptide Y and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide after kainic acid-induced seizures in the rat. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 339, 173–177.

Milenkovic, I., Weick, M., Wiedemann, P., Reichenbach, A., and Bringmann, A. (2004). Neuropeptide Y-evoked proliferation of retinal glial (Muller) cells. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 242, 944–950. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0954-3

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ming, G. L., and Song, H. (2011). Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron 70, 687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mosher, K. I., Andres, R. H., Fukuhara, T., Bieri, G., Hasegawa-Moriyama, M., He, Y., et al. (2012). Neural progenitor cells regulate microglia functions and activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1485–1487. doi: 10.1038/nn.3233

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Movafagh, S., Hobson, J. P., Spiegel, S., Kleinman, H. K., and Zukowska, Z. (2006). Neuropeptide Y induces migration, proliferation and tube formation of endothelial cells bimodally via Y1, Y2 and Y5 receptors. FASEB J. 20, 1924–1926. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4770fje

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nan, Y. S., Feng, G. G., Hotta, Y., Nishiwaki, K., Shimada, Y., Ishikawa, A., et al. (2004). Neuropeptide Y enhances permeability across a rat aortic endothelial cell monolayer. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286, H1027–H1033. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00630.2003

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nishimura, Y. V., Shikanai, M., Hoshino, M., Ohshima, T., Nabeshima, Y., Mizutani, K., et al. (2014). Cdk5 and its substrates, Dcx and p27kip1, regulate cytoplasmic dilation formation and nuclear elongation in migrating neurons. Development 141, 3540–3550. doi: 10.1242/dev.111294

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Noble, E. E., Billington, C. J., Kotz, C. M., and Wang, C. F. (2011). The lighter side of BDNF. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300, R1053–R1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00776.2010

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Oomen, S. P., Hofland, L. J., van Hagen, P. M., Lamberts, S. W., and Touw, I. P. (2000). Somatostatin receptors in the haematopoietic system. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 143(Suppl. 1), S9–S14. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.143s009

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Palmer, T. D., Willhoite, A. R., and Gage, F. (2000). Vascular niche for adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 425, 479–494. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001002)425:4<479::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-3

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Parent, J. M., von dem Bussche, N., and Lowenstein, D. H. (2006). Prolonged seizures recruit caudal subventricular zone glial progenitors into the injured hippocampus. Hippocampus 16, 321–328. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20166

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Park, S., Fujishita, C., Komatsu, T., Kim, S. E., Chiba, T., Mori, R., et al. (2014). NPY antagonism reduces adiposity and attenuates age-related imbalance of adipose tissue metabolism. FASEB J. 28, 5337–5348. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-258384

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Parker, R. M. C., and Herzog, H. (1999). Regional distribution of Y-receptor subtype mRNAs in rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 1431–1448. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00553.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Parpura, V., Heneka, M. T., Montana, V., Oliet, S. H., Schousboe, A., Haydon, P. G., et al. (2012). Glial cells in (patho)physiology. J. Neurochem. 121, 4–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07664.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pedrazzini, T., Pralong, F., and Grouzmann, E. (2003). Neuropeptide Y: the universal soldier. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60, 350–377. doi: 10.1007/s000180300029

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pons, J., Lee, E. W., Li, L., and Kitlinska, J. (2004). Neuropeptide Y: multiple receptors and multiple roles in cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5, 957–962.

Prada, I., Marchaland, J., Podini, P., Magrassi, L., D’Alessandro, R., Bezzi, P., et al. (2011). REST/NRSF governs the expression of dense-core vesicle gliosecretion in astrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 193, 537–549. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010126

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ramamoorthy, P., and Whim, M. D. (2008). Trafficking and fusion of neuropeptide Y-containing dense-core granules in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 28, 13815–13827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5361-07.2008

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Redrobe, J. P., Dumont, Y., Herzog, H., and Quirion, R. (2004). Characterization of neuropeptide Y, Y(2) receptor knockout mice in two animal models of learning and memory processing. Mol. Neurosci. 22, 159–166. doi: 10.1385/jmn:22:3:159

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Riquelme, P. A., Drapeau, E., and Doetsch, F. (2008). Brain micro-ecologies: neural stem cell niches in the adult mammalian brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 123–137. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2016

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rodrigo, C., Zaben, M., Lawrence, T., Laskowski, A., Howell, O. W., and Gray, W. P. (2010). NPY augments the proliferative effect of FGF2 and increases the expression of FGFR1 on nestin positive postnatal hippocampal precursor cells, via the Y1 receptor. J. Neurochem. 113, 615–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06633.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roybon, L., Hialt, T., Stott, S., Guilemot, F., Li, J. Y., and Brundin, P. (2009). Neurogenin2 directs granule neuroblast production and amplification while NeuroD1 specifies neuronal fate during hippocampal neurogenesis. PLoS One 4:e4779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004779

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sanabria, P., and Silva, W. I. (1994). Specific 125I neuropeptide Y binding to intact cultured bovine adrenal medulla capillary endothelial cells. Microcirculation 1, 267–273. doi: 10.3109/10739689409146753

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Santos-Carvalho, A., Álvaro, A. R., Martins, J., Ambrósio, A. F., and Cavadas, C. (2014). Emerging novel roles of neuropeptide Y in the retina: from neuromodulation to neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 112, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.002

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Santos-Carvalho, A., Aveleira, C. A., Elvas, F., Ambrósio, A. F., and Cavadas, C. (2013). Neuropeptide Y receptors Y1 and Y2 are present in neurons and glial cells in rat retinal cells in culture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 429–443. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10776

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Scharfman, H. E., and Gray, W. P. (2006). Plasticity of neuropeptide Y in the dentate gyrus after seizures and its relevance to seizure-induced neurogenesis. EXS 95, 193–211. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7417-9_15

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Seri, B., García-Verdugo, J. M., McEwen, B. S., and Alvarez-Buylla, A. (2001). Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 21, 7153–7160.

Seri, B., Herrera, D. G., Gritti, A., Ferron, S., Collado, L., Vescovi, A., et al. (2006). Composition and organization of the SCZ: a large germinal layer containing neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cereb. Cortex 16(Suppl. 1), i103–i111. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk027

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, Q., Goderie, S. K., Jin, L., Karanth, N., Sun, Y., Abramova, N., et al. (2004). Endothelial cells stimulate self-renewal and expand neurogenesis of neural stem cells. Science 304, 1338–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1095505

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, Q., Wang, Y., Kokovay, E., Lin, G., Chuang, S. M., Goderie, S. K., et al. (2008). Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell 3, 289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sierra, A., Encinas, J. M., Deudero, J. J., Chancey, J. H., Enikolopov, G., Overstreet-Wadiche, L. S., et al. (2010). Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell 7, 483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.014

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Silva, A. P., Kaufmann, J. E., Vivancos, C., Fakan, S., Cavadas, C., Shaw, P., et al. (2005). Neuropeptide Y expression, localization and cellular transducing effects in HUVEC. Biol. Cell 97, 457–467. doi: 10.1042/bc20040102

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Snapyan, M., Lemasson, M., Brill, M. S., Blais, M., Massouh, M., Ninkovic, J., et al. (2009). Vasculature guides migrating neuronal precursors in the adult mammalian forebrain via brain derived neurotrophic factor signaling. J. Neurosci. 29, 4172–4188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4956-08.2009

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sofroniew, M. V. (2009). Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 32, 638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sperk, G., Hamilton, T., and Colmers, W. F. (2007). Neuropeptide Y in the dentate gyrus. Prog. Brain Res. 163, 285–297. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(07)63017-9

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stanic, D., Paratcha, G., Ledda, F., Herzog, H., Kopin, A. S., and Hökfelt, T. (2008). Peptidergic influences on proliferation, migration and placement of neural progenitors in the adult mouseforebrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 3610–3615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712303105

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

St-Pierre, J. A., Nouel, D., Dumont, Y., Beaudet, A., and Quirion, R. (2000). Sub-population of cultured hippocampal astrocytes expresses neuropeptide Y Y(1) receptors. Glia 1, 82–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200003)30:1<82::aid-glia9>3.3.co;2-#

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Su, P., Zhang, J., Zhao, F., Aschner, M., Chen, J., and Luo, W. (2014). The interaction between microglia and neural stem/precursor cells. Brain Res. Bull. 109, 32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.09.005

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sun, J., Zhou, W., Ma, D., and Yang, Y. (2010). Endothelial cells promote neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation associated with VEGF activated Notch and Pten signaling. Dev. Dyn. 239, 2345–2353. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22377

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tavazoie, M., Van der Veken, L., Silva-Vargas, V., Louissaint, M., Colonna, L., Zaidi, B., et al. (2008). A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 3, 279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Teng, H., Zhang, Z. G., Wang, L., Zhang, R. L., Zhang, L., Morris, D., et al. (2008). Coupling of angiogenesis and neurogenesis in cultured endothelial cells and neural progenitor cells after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 28, 764–771. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600573

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Thiriet, N., Agasse, F., Nicoleau, C., Guégan, C., Vallette, F., Cadet, J. L., et al. (2011). NPY promotes chemokinesis and neurogenesis in the rat subventricular zone. J. Neurochem. 116, 1018–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07154.x

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tilan, J. U., Everhart, L. M., Abe, K., Kuo-Bonde, L., Chalothorn, D., Kitlinska, J., et al. (2013). Platelet neuropeptide Y is critical for ischemic revascularization in mice. FASEB J. 27, 2244–2255. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213546

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Togari, A. (2002). Adrenergic regulation of bone metabolism: possible involvement of sympathetic innervation of osteoblastic and osteoclastic cells. Microsc. Res. Tech. 58, 77–84. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10121

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ubink, R., Calza, L., and Hökfelt, T. (2003). ‘Neuro’-peptides in glia: focus on NPY and galanin. Trends Neurosci. 11, 604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.003

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ubink, R., Halasz, N., Zhang, X., Dagerlind, A., and Hökfelt, T. (1994). Neuropeptide tyrosine is expressed in ensheathing cells around the olfactory nerves in the rat olfactory bulb. Neuroscience 60, 709–726. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90499-5

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

van den Pol, A. N. (2012). Neuropeptide transmission in brain circuits. Neuron 76, 98–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.014

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vezzani, A., and Sperk, G. (2004). Overexpression of NPY and Y2 receptors in epileptic brain tissue: an endogenous neuroprotective mechanism in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropeptides 38, 245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.05.004

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vezzani, A., Sperk, G., and Colmers, W. F. (1999). Neuropeptide Y: emerging evidence for a functional role in seizure modulation. Trends Neurosci. 22, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01284-3

PubMed Abstract | Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar