- Department of Physiology and Biophysics, College of Medicine, Howard University, Washington, DC, United States

Mitochondrial genomic stability is critical to prevent various human inflammatory diseases. Bacterial infection significantly increases oxidative stress, driving mitochondrial genomic instability and initiating inflammatory human disease. Oxidative DNA base damage is predominantly repaired by base excision repair (BER) in the nucleus (nBER) as well as in the mitochondria (mtBER). In this review, we summarize the molecular mechanisms of spontaneous and H. pylori infection-associated oxidative mtDNA damage, mtDNA replication stress, and its impact on innate immune signaling. Additionally, we discuss how mutations located on mitochondria targeting sequence (MTS) of BER genes may contribute to mtDNA genome instability and innate immune signaling activation. Overall, the review summarizes evidence to understand the dynamics of mitochondria genome and the impact of mtBER in innate immune response during H. pylori-associated pathological outcomes.

Introduction

Mitochondria are essential organelles responsible for energy production and maintaining calcium homeostasis, lipid, and amino acid metabolism (Casanova et al., 2023). The human mitochondria DNA (mtDNA) is present in multiple copies per cell (Filograna et al., 2021). Targeting mitochondria has emerged as a key strategy for bacteria to hijack host cell physiology and promote infection (Blanke, 2005; Fielden et al., 2017). Numerous pathogenic bacteria have evolved strategies to subvert the mitochondrial functions of host cells to support their own proliferation and dissemination (Galmiche et al., 2000; Fischer et al., 2004; Stavru et al., 2011). In addition, bacteria can modulate mitochondrial functions to access nutrients and/or evade the host’s immune system (Spier et al., 2019). Infection by extracellular pathogens including H. pylori is able to change the mitochondrial metabolic and oxidative profile of infected cells (Andrieux et al., 2021). Furthermore, a study has shown that H. pylori infection induces genetic dysfunction in both nDNA and mtDNA (Hiyama et al., 2003).

Notably, mtDNA is a hotspot for constant insult from both exogenous and endogenous stresses (Alexeyev et al., 2013). Cellular and biochemical evidence suggests that mtDNA is more susceptible to oxidized DNA damages than nuclear DNA due to its proximity to the sites of oxidative phosphorylation and lack of protection by histones (Yakes and Van Houten, 1997; Druzhyna et al., 2008). Excessive accumulation of mtDNA damages leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and provokes the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including neurodegeneration, cancer, and diabetes (Wallace, 2005; Nakabeppu et al., 2007; Llanos-Gonzalez et al., 2019). Oxidative DNA damage lesions in mtDNA and/or mtDNA replication blocks are removed by different types of DNA damage repair enzymes (LeDoux et al., 1992; Zhao and Sumberaz, 2020). Most of the repair proteins and/or enzymes are imported from the nucleus, where they process oxidative mtDNA lesions and promote repair (Bohr, 2002; de Souza-Pinto et al., 2009; Gredilla, 2010). However, the loss of these nuclear and mitochondria-encoded repair proteins significantly impairs repair efficiency in mitochondria (Lia et al., 2018). Therefore, the role and function of mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage repair are not expected to be independent of nuclear BER.

In eukaryotic cells, mtDNA molecules are organized into several hundred nucleoids (Legros et al., 2004; Wang and Bogenhagen, 2006; Bogenhagen, 2012; Prachar, 2016), which function as units of mtDNA propagation for replication, segregation, and gene expression (Spelbrink, 2010; Ban-Ishihara et al., 2013; Kolesnikov, 2016). Several proteins are involved in maintaining the integrity of mitochondrial genome replication, including DNA polymerase γ (POLG), TWINKLE (DNA helicase), mitochondrial RNA polymerase (POLRMT), mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein (mtSSB), RNASEH1, DNA ligase III, mitochondrial genome maintenance exonuclease1 (MGME1), flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1), and topoisomerase (Sharma and Sampath, 2019; Fontana and Gahlon, 2020). POLG plays a significant role in maintaining mtDNA replication integrity and participates in base excision repair. Moreover, POLG has 3′–5′ exonuclease and 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) activities associated with its catalytic subunit (Kaguni, 2004; Graziewicz et al., 2006). POLG’s polymerase activity is critical to synthesize DNA, and it also has a weak dRP lyase function that is complemented by DNA polymerase beta (POLB) dRP lyase activity (Longley et al., 1998; Sykora et al., 2017). Furthermore, the primase activity of PrimPol initiates de novo DNA synthesis using deoxynucleotide while discriminating against ribonucleotides (Martinez-Jimenez et al., 2018; Diaz-Talavera et al., 2022). Other DNA repair factors, such as mitochondrial single-stranded binding protein 1 (SSBP1), protect the active replicative DNA regions (Guilliam et al., 2015). Based on several studies, three different models have been proposed for mtDNA replication (Robberson et al., 1972; McKinney and Oliveira, 2013). Among these three models, the strand-displacement model (SDM) is the most accepted model because it best explains the dynamics of mtDNA replication. According to this model, replication starts at the oriH site and proceeds unidirectionally until it reaches the origin of light strand (oriL). At this point, the synthesis of light strand begins in the opposite direction, continuing until the replication of both strands is complete. Importantly, mutations in the mitochondrial replisome’s proteins POLG, TFAM, and MGME1 genes are associated with the accumulation of mtDNA deletions that may also increase susceptibility for infection-induced chronic-inflammation-associated disease (Spelbrink et al., 2001; Longley et al., 2006; Nicholls et al., 2014; Fontana and Gahlon, 2020). In the next section of this manuscript, we will address key questions such as (i) how do host cells handle oxidative stress-associated mtDNA damage via BER in the presence and absence of bacterial infection, (ii) how do oxidative-stress-induced base lesions or repair intermediates impact mtDNA replication dynamics, and (iii) does infection by extracellular bacteria, such as H. pylori, induce mtDNA-mediated innate immune signaling?

mtDNA damage and BER in mitochondria

Upon bacterial infection, a major challenge for host cells is the maintenance of genomic integrity. Pathogenic bacteria can cause DNA damage in host cells, often resulting in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, 2014; Song and Bent, 2014). Numerous studies have reported that H. pylori infection induces DNA damage and alter the DNA repair capacity (Dorer et al., 2010; Lieber, 2010; Toller et al., 2011; Chaturvedi et al., 2014; Koeppel et al., 2015). H. pylori has been found to cause several types of DNA damage, including single-strand breaks (SSBs) and DSBs in nuclear genome (Fox and Wang, 2007; Lieber, 2010). High-throughput genomic analyses have shown that H. pylori causes a specific pattern of DNA damage in the transcribed and telomere-proximal regions of the genome (Chaturvedi et al., 2014). Furthermore, H. pylori infection induces mtDNA damage that includes oxidative damage, adducts formation, base mismatch, and DNA strand breaks (Babbar et al., 2020). Given its proximity to ROS-generating electron transport chain and the absence of histones, mtDNA is more vulnerable to oxidative DNA damage than nDNA (Maynard et al., 2009). Oxidative damage to mtDNA can manifest as base modifications, abasic sites, and various other types of lesions (Cooke et al., 2003). One of the most studied lesions in mtDNA is 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), which is a mutagenic lesion (Kurosaka et al., 1991). Mispairing of 8-oxoG with adenine results in a G–C to T–A transversion during subsequent rounds of replication. Early studies showed that 8-oxoG lesions are 16 times more frequent in mtDNA than in nDNA (Richter et al., 1988). In more definitive studies, Yakes and Van Houten showed that mtDNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nDNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress (Yakes and Van Houten, 1997). In addition, unrepaired mtDNA base damage intermediates, such as single-stranded strand breaks (SSBs), arise as a result of the erroneous or abortive activity of DNA topoisomerase I (Hudson et al., 2012), contributing to mitochondrial genome instability (Zhang et al., 2001). In addition, H. pylori infection may also lead to replication stress in mtDNA that may eventually alter the expression and function of mitochondrial genes and transcription factors that contribute to the accumulation of mtDNA damage (Chatre et al., 2017). It is also possible that the enhanced oxidative stress due to H. pylori infection might be a possible cause of unfit mitochondria for replication in infected host cells. Another important factor for increased mitochondrial DNA damage is mtDNA mutations that occur during replication by insertion/deletion of the wrong nucleotide. Although the POLG has 3′–5′ exonuclease proofreading activity that corrects the mis-incorporation of the nucleotide, the error rate of mDNA replication, however, exceeds the repair capacity, potentially increasing the mutation frequency (Kaguni, 2004). Moreover, H. pylori induces genomic instability in nuclear CA repeats in mice and in mtDNA (MaChado et al., 2009).

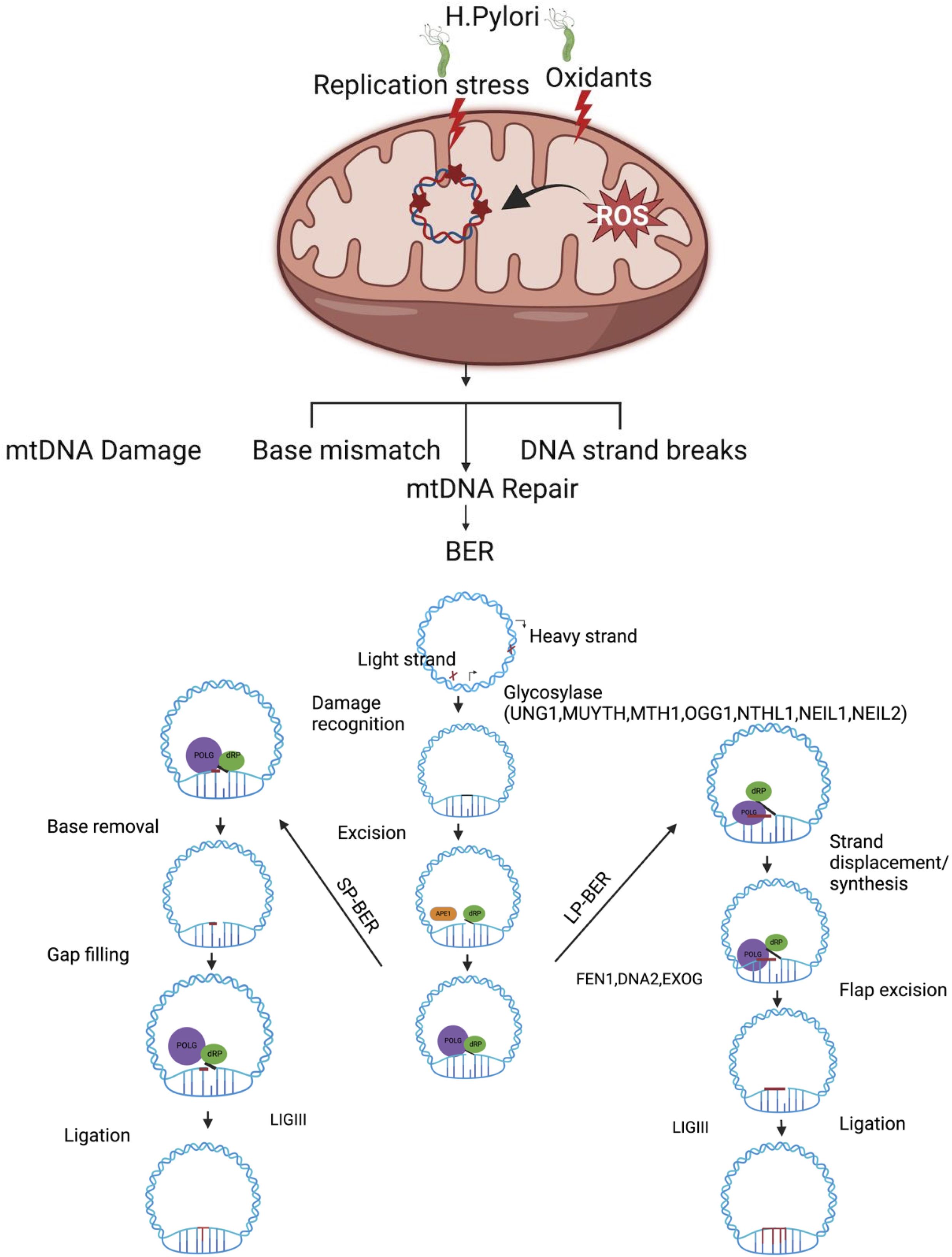

Although various DNA repair pathways have been documented including direct reversal, BER, NER, and MMR in cells (Jalal et al., 2011; Chatterjee and Walker, 2017), the BER pathway is the predominant pathway for repairing mtDNA damage (Bohr and Anson, 1999; Druzhyna et al., 2008). Like nDNA, an efficient mtDNA repair pathway, especially the BER pathway, may play an important role in repairing oxidative mtDNA damage (Figure 1). Mitochondria BER (mtBER) proteins are localized in the inner membrane and co-exist with the TFAM nucleoid structure protein (Stuart et al., 2005). The first step of mtBER involves DNA base damage recognition by seven different DNA glycosylases. These glycosylases contain a mitochondria translocation signaling (MTS) leader sequence, which facilitates their transport into the mitochondria. Once inside, these DNA glycosylases remove damaged mtDNA nucleotide lesions. The second step involves cleaving the sugar–phosphate backbone of the mtDNA using AP endonuclease that processes the abasic site (AP). This is followed by the action of POLG, which re-synthesizes missing DNA patches. Finally, DNA ligase (LIG3) seals the DNA fragments (Szczepanowska and Trifunovic, 2015). The alternative mechanism is that mtDNA repair machinery engages in end processing using distinct gap-tailoring enzymes, including aprataxin (Ahel et al., 2006) and TDP1 (Das et al., 2010). However, if aprataxin proteins are unable to repair the 5′-AMP group, it can block DNA ligase repair activity and generate SSBs (Sykora et al., 2011). The mtDNA damage induced by H. pylori infection may lead to mtDNA single-strand breaks (mtSSBs), mtDNA double-strand breaks (mtDSBs), and base mismatches which are potentially processed via different types of repair machinery (Figure 1). Due to the types of oxidative DNA damage substrate specificity, the preference of DNA glycosylase may vary, and it is possible that they might influence each other’s activity (MaChado et al., 2009). The DNA glycosylases OGG1, UDG1, and MYH (Ohtsubo et al., 2000) are all associated with the particulate fraction of the mitochondria as are POLG, DNA ligase III, and a minor portion of AP endonuclease activity (Stuart et al., 2005). The mitochondria harbor bifunctional 8-oxoguanine, DNA glycosylase-1 (OGG1), and monofunctional uracil–DNA glycosylase (UNG1) to process different mtDNA base lesions (Jacobs and Schar, 2012). These glycosylases are discussed below.

Figure 1. Oxidative stress induced by H. pylori infection leads to damage in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is primarily repaired through the base excision repair (BER) pathway. The BER pathway operates through two different mechanisms to maintain the mitochondrial genome: short-patch BER (SP-BER) removes a single damaged nucleotide, while long-patch BER (LP-BER) removes between two and eight damaged nucleotides during the repair process. H. pylori infection induces genotoxin-mediated mtDNA and increases oxidative-stress-associated mtDNA damage and mtDNA replication stress. A single-base damage or single-strand break on mtDNA is likely processed via BER. mtDNA single-base damage is potentially recognized and removed by one of the DNA glycosylases (UNG1, OGG1, MUTHY MTH1, NTHL1 NEIL1, and NEIL2), followed by end processing via the dRP lyase activity of POLB and gap filling with POLG inserts in the correct base, and LIGII seals the mtDNA nick. In long-patch BER, strand displacement DNA synthesis is processed by POLG and displaces 5′ DNA flap downstream of the repair site, which must be removed by flap endonuclease (FEN1) and other partner/DNA2/EXOG involved to process the 5′ end of the DNA. Once tailoring of the 5′ and 3′ ends of mtDNA is complete, LIGIII seals the mtDNA nick. Figure created with BioRender.com.

DNA glycosylase in mitochondria

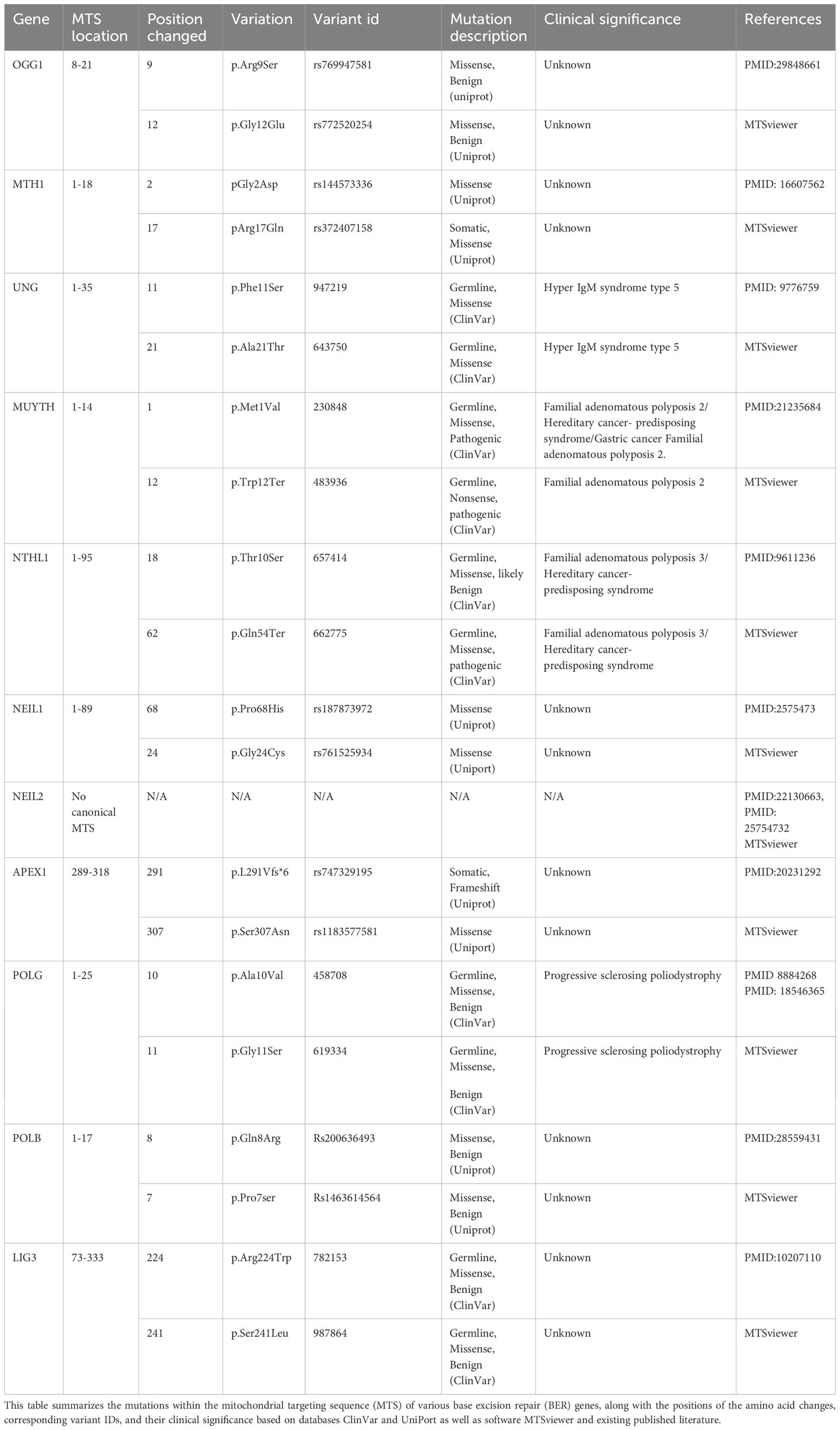

Several studies have identified five bifunctional and two monofunctional DNA glycosylases in the mitochondria (Prakash and Doublie, 2015). Uracil–DNA glycosylase 1 (UDG1 or uracil-N-glycosylase1 [UNG1]) (Anderson and Friedberg, 1980) and MUTYH (MYH), a homolog of the Escherichia coli MutY glycosylase (Ohtsubo et al., 2000), are classified as monofunctional DNA glycosylases. The substrate specificities of UNG1 and MUTYH have been recently reviewed (Svilar et al., 2011). MUTYH is an adenine–DNA glycosylase that preferentially excise adenine when paired with 8-oxoG, initiating a round of base excision repair that restores the 8-oxoG:C pair and protects the DNA from mutagenic 8-oxoG lesions (Michaels et al., 1992). In addition, several studies have shown that mitochondria can repair alkylation lesions using monofunctional glycosylase, MPG (Chakravarti et al., 1991; Pirsel and Bohr, 1993; Ledoux et al., 1998). The UNG1 enzymes cleave substrates from both single-stranded (ss) DNA and double-stranded (ds) DNA with a slight preference for ss over ds substrates. Importantly, UNG1 has a MTS comprising a 30-amino-acid leader sequence at the N-terminal end of the enzyme that likely facilitates entry into the inner mitochondrial membrane (Neupert, 1997). Amino acid substitution (Y147A or N204D) in the catalytic domain of UNG1 switches the substrate specificity of the enzyme and is able to remove thymine and uracil from mtDNA (Kavli et al., 1996). Removing mtDNA base lesions in this manner leaves excess apyrimidinic sites, which are highly genotoxic to the cells (Glassner et al., 1998; Lindahl and Wood, 1999). mtDNA has been shown to accumulate high levels of mutagenic lesions of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, which is the byproduct of guanine hydroxylation (Nakabeppu, 2014). Previous work has shown that 8-oxodG, the most prominent oxidative DNA base lesion, is repaired more efficiently in the mitochondria than in the nucleus (Thorslund et al., 2002). These 8oxoG lesions are recognized and processed by OGG1 glycosylase (Mandal et al., 2012) which localizes to both the nucleus and mitochondria (Klungland et al., 1999; Nishioka et al., 1999; Klungland and Bjelland, 2007). However, the loss of OGG1 compromises the metabolic function of mitochondria, indicating an additional role in maintaining the bioenergetic homeostasis of the cell (Lia et al., 2018). Notably, other DNA glycosylases such as NTHL1 are found in both the nucleus and mitochondria and only active with duplex DNA. NTHL1 is a bifunctional glycosylase involved in the excision of oxidized DNA bases such as Tg, 5-hydroxycytosine (5-hC), 5-hydroxyuracil (5-hU), and the ring-opened 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy) lesions (Prakash and Doublie, 2015). Previously, we have shown that the single-nucleotide variant of NTHL1 promotes genomic instability in cells (Galick et al., 2013). However, the biological significance of this mutant variant in mitochondria is unclear and requires further investigation. Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated that DNA glycosylases, including NEIL1 and NEIL2, form a complex with mitochondrial genes MT-CO2 and MT-CO3 (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 and 3) and mitochondrion-specific POLG (Mandal et al., 2012). NEIL2 interacts with PNK to maintain the mammalian mitochondrial genome (Mandal et al., 2012). NEIL2 shows a unique preference for excising lesions from a DNA bubble. In contrast, NEIL1 efficiently excises 5-hydroxyuracil, an oxidation product of cytosine, from the bubble and single-stranded DNA but does not have strong activity toward 8-oxoguanine in the bubble (Dou et al., 2003). Furthermore, MTH1 DNA glycosylase, which is localized in both the mitochondria and nucleus, plays a significant role in repairing oxidized dATP and ATP, such as 2-OH-dATP and 2-OH-ATP, as well as 8-oxo-dGTP (Bialkowski and Kasprzak, 1998; Fujikawa et al., 1999; Fujikawa et al., 2001; Nakabeppu et al., 2006). The function of those nuclear-encoded DNA glycosylases likely depends on their ability to pass through the mitochondrial membrane via MTS signals. However, there are single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the MTS of these glycosylases that may impact their function and cause mitochondrion-associated human diseases (Table 1). Uncovering the biological significance of these SNPs will likely shed mechanistic insights on the impact of DNA glycosylase in mitochondrial genome integrity and its biological outcomes.

Table 1. Variants associated with mutation on mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) of base excision repair (BER) genes and its clinical significance.

APE1 endonuclease

APE1 is a multifunctional protein that plays a central role in the maintenance of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. APE1 translocates into the mitochondria in response to oxidative stress and increases mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair rate and cell survival (Barchiesi et al., 2020). Protein sequence analysis suggests that APE1 harbors MTS signal sequence within residues 289–318 in the C terminus, which is normally masked by the intact N-terminal structure (Li et al., 2010). Once APE1 is translocated in the mitochondria, it is able to remove the AP sites and hand over the reaction to the next repair factors. In contrast, genetic ablation of APE1 results in the accumulation of damaged mitochondrial mRNA species, impairment in protein translation, and reduced expression of mitochondrial encoded proteins, leading to less efficient mitochondrial respiration (Barchiesi et al., 2020). It is possible that loss of APE1 may increase the number of AP sites, potentially driving mtDNA instability. A few studies suggested that APE1 depletion in cells leads to increased mtDNA copy number (Barchiesi et al., 2021).

DNA polymerase enzymes

The ability to effectively repair various types of DNA damage is achieved through multiple, often overlapping, DNA repair pathways. DNA POLB and POLG are involved in mtDNA repair process (Copeland, 2010). Once the AP site is processed by APE1, the gap is filled by POLG with correct nucleotides. The Wilson study estimated that ~30% of POLB localize to the mitochondria, as shown through the colocalization studies of TOM20 (Prasad et al., 2017). Additional high-quality immunogold electron microscopy (EM) localization studies demonstrated that 20% of POLB localize to the mitochondrial matrix and 60% to the nucleus (Prasad et al., 2017). POLG has DNA polymerase activity to fill DNA gaps but lacks efficient dRP lyase activity to process the 5′dRP groups (Kaufman and Van Houten, 2017). Bohr’s and Wilson’s groups identified a robust dRP lyase activity in the mitochondria belonging to POLB (Sykora et al., 2017). Biochemical characterization indicates that the 5′dRP lyase activity of DNA polymerase beta plays a primary role in complementing POLG by removing the 5′dRP group, thus promoting short-patch-BER in mtDNA. Both POLB and POLG support gap filling in single nucleotide gaps (Kaufman and Van Houten, 2017). POLG is known for its high replication fidelity, which allows it to support both replication and repair functions in the mitochondria. This high fidelity, however, may be detrimental in situations that require the polymerase to bypass a lesion.

DNA ligase

DNA LIG III is a key factor of the BER pathway which is shared between the mitochondria and the nucleus compartment, where it is involved in sealing DNA nicks to complete mtDNA repair processes. LIG3 is the only vertebral mitochondrial DNA ligase identified so far and is essential for mitochondrial DNA maintenance (Gao et al., 2011; Simsek et al., 2011). In the mitochondria, LIG3 interacts with tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1), NEIL1/2 glycosylases, and POLG (Simsek and Jasin, 2011). In vitro work shows that downregulation of LIG3 in human fibroblastoma cell lines decreased the mtDNA copy number, reduces respiration, and leads to the accumulation of DNA SSBs in mtDNA. In contrast, the complete lack of LIG3 in murine cells leads to the full depletion of mtDNA, underlying the essential role of LIG3 in mitochondrial genome integrity (Lakshmipathy and Campbell, 2001; Shokolenko et al., 2013). The somatic and germline variants of LIG3 may contribute to the loss of function and accumulation of mtDNA damage which likely drives mitochondrion-associated human pathologies.

Impact of aberrant BER repair on mitochondrial genomic integrity

Loss of BER results in the accumulation of mutation [(C:G→T transversions] (Whitaker et al., 2017) or DNA single-strand (Lindahl, 1993) or double-strand breaks (DSBs)] (Woodbine et al., 2011; Fridlich et al., 2015), which are principal sources of genomic instability (Khanna and Jackson, 2001; Caldecott, 2008). Dysfunctional mtBER leads to the accumulation of mtDNA D-loop mutation in gastrointestinal cancer (Wang et al., 2018). DNA-repair-deficient mitochondria are more susceptible to oxidative DNA damage agents (Shokolenko et al., 2003). It is possible that loss or mutation in MTS signaling sequence contributes to the lack of mtBER in the mitochondrial compartment. Mutations in MTS of BER genes may prevent the import of the nuclear encoded BER proteins into the mitochondria, resulting in the loss of their biological functions in the mitochondria. Germline and somatic variants of BER genes that harbor MTS mutations likely cause deficiency in mtBER repair pathways, contributing to mitochondrial genome instability and human diseases (Table 1). Germline BER variants with non-synonymous mutations in the MTS sequence likely increase the risk factor for different pathophysiological outcomes. Similarly, mutations in BER genes within tumors may contribute to tumor initiation and progression. It is important to note that the genetic mutations in MTS, analyzed using the MTSViewer platform, suggested MTS mutation sites, and clinical variant scores likely suggest the potential impact of these mutations on protein structure and function in the mitochondria.

Impact of H. pylori infection on mitochondrial genome transactions

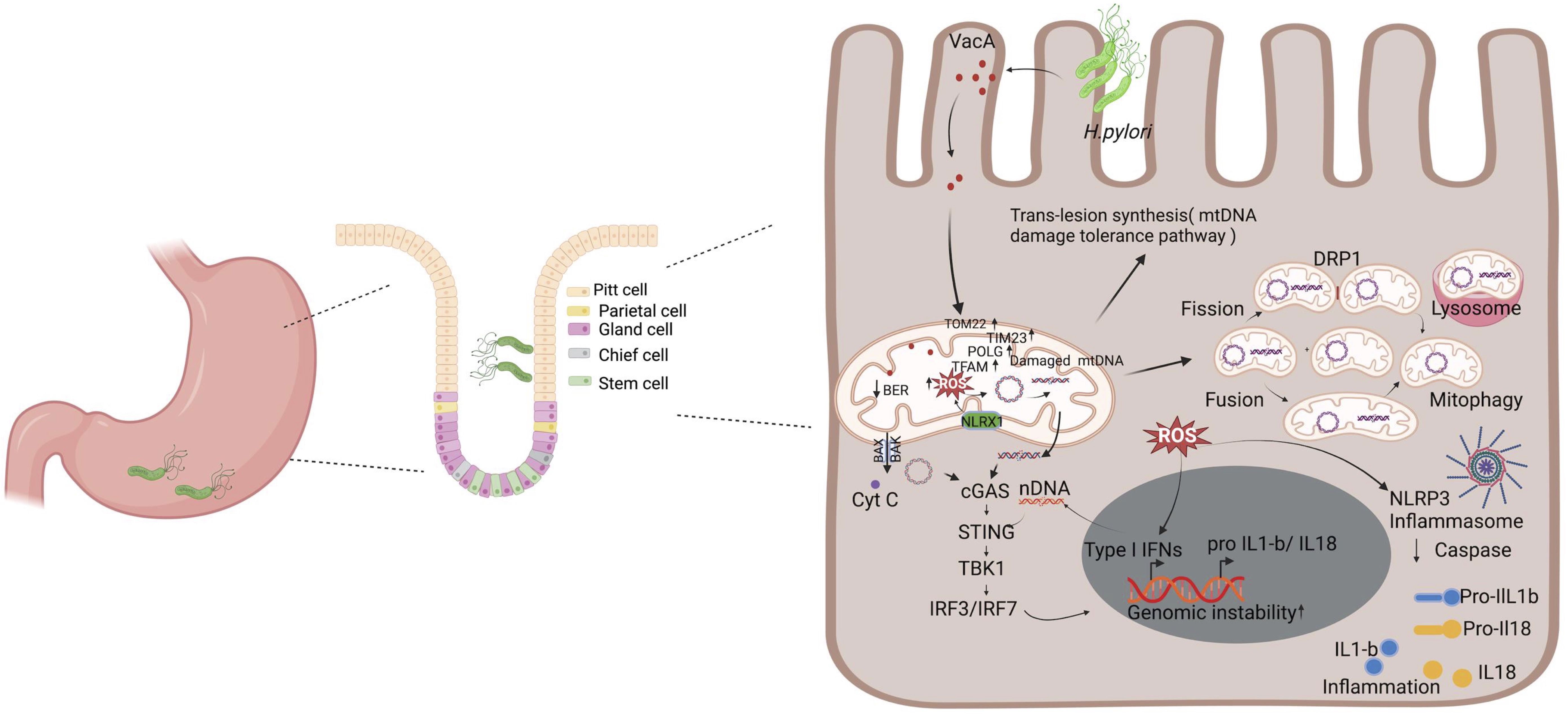

H. pylori infection causes chronic gastric inflammation (Peek and Blaser, 2002), and patients with a previous history of H. pylori infection are at a higher risk to develop gastric cancers (Aoi et al., 2006). Furthermore infection with H. pylori suppresses stomach acidity and may result in a more permissive milieu for colonization with other bacteria (Dicksved et al., 2009). Mitochondrial dynamics play important roles in bacterial pathogenesis, with multiple mitochondrial functions mechanistically linked to their morphology, which is defined by ongoing events of fission and fusion of the outer and inner membranes (Cogliati et al., 2016). H. pylori infection dysregulates the delicate balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion networks (Scott and Youle, 2010). Mitochondrial fusion allows the mitochondria with normal mtDNA to compensate for defects in the mitochondria with damaged mtDNA (Nakada et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2001; Yang and Gao, 2018). These processes are governed by a complex molecular machinery and finely tuned by regulatory proteins (Tilokani et al., 2018). H. pylori-induced mtDNA damage may contribute to trigger this event via genomic instability such as mutations and deletions in mitochondrial DNA that yield a heteroplasmic mixture of wild-type and mutant mitochondrial genomes within one cell (Taylor and Turnbull, 2005). As shown in Figure 2, the mtDNA that harbor extensive damage likely removed from the cellular system via mitochondria fission process to minimize the carryover of undesirable genetic traits to next cell cycle. Furthermore, mitochondrial fission is needed to create not only new mitochondria, but also contributes to quality control by enabling the removal of damaged mitochondria and can facilitate apoptosis during high levels of cellular stress. Therefore, mitochondrial fission is an important element to eliminate infected cells and reduce cell-to-cell-spreading, thus modulating apoptosis and bacterial dissemination (Spier et al., 2019). In contrast mitochondria harboring different genetic lesions likely compensate for their defects by relying on the genetic content from other mitochondria through the fusion process. Damaged and undamaged mtDNAs yield a heteroplasmic mixture of normal and mutant mitochondrial genomes within the same cell (Wonnapinij et al., 2008; Aryaman et al., 2018). The mitochondria fusion scenario likely maintained if the mutation rate in the mitochondria remain below ~ 80% per cell, the mitochondria in heteroplasmic cells complement one another to compensate their defects (Yoneda et al., 1994; Nakada et al., 2001). Mitochondrial Fusion can rescue two mitochondria with mutations in different genes through cross-complementation to one another, and it can mitigate the effects of H. pylori infection induced DNA damage by the exchange of repair proteins and other factors with other mitochondria. It is also important that mitochondrial fusion can therefore maximize oxidative capacity in response to toxic stress and use alternative resource or repair factors to fix the damaged region of mtDNA.

Figure 2. H. pylori-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation. Upon infection, H. pylori secretes toxins such as VacA, which interacts with the mitochondria, leading to the modulation of its function and ultimately promoting pathogenesis. It decreases the mitochondrial membrane potential, leading to reduced ATP production and an increase in cytochrome c release that triggers autophagy. Additionally, VacA enhances the mtDNA damage and the generation of ROS. This triggers a series of stress responses, including the upregulation of mitochondrial DNA repair mechanism factors (e.g., POLG and TFAM) and the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway due to the release of damaged mtDNA and nDNA in the cytosol. Cells have a mechanism to respond to unrepaired mtDNA damages that includes trans-lesion synthesis, fusion, fission, and mitophagy that degrades severely damaged mitochondria. The accumulation of ROS and the release of mitochondrial contents also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to the processing and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Collectively, these processes contribute to chronic inflammation and genomic instability, which are key factors in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-related diseases, including gastritis and gastric cancer. Figure created with BioRender.com.

H. pylori toxin-induced mitochondria dysfunction

Mitochondria play a central role in the innate immune response. It is at the center of the inflammatory response in the case of a viral or bacterial infection or spontaneous cellular damage. Because of their structural similarity to their bacterial ancestor, extracellular mitochondria and their components may operate as a danger signal by means of their interaction with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs are a group of receptors that can specifically detect molecular patterns found on the surfaces of pathogens, apoptotic cells and damaged senescent cells. In the case of an infection by a pathogenic agent, the microorganisms will be detected by PRR that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as flagellins, lipopolysaccharide, mannose, nucleic acids and proteins and the danger-associated molecular motifs (DAMPs) molecules. In addition, the presence of the bacterial virulence factors such as type IV secretion system (T4SS), the bacterial protein CagA and the vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) is associated with chronic inflammation and increased risk of gastric cancer development (Peek and Blaser, 2002). H. pylori strains are categorized into cagA‐positive and cagA‐negative strains based on the presence or absence of the cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI). The cagPAI, is an ~40‐kb DNA segment containing around 30 genes (open reading frames), which include cagA and several genes encoding components of a bacterial Type IV secretion system (T4SS), that delivers CagA into attached gastric epithelial cells (Covacci and Rappuoli, 2000). Cag A is capable to induce cytosolic Ca2+ influx, leading to mitochondria ROS production. In addition, Cag A can upregulate the expression level of spermine oxidase (SMO), which can convert spermine to spermidine and simultaneously releases hydrogen peroxide (Chaturvedi et al., 2011; Cindrilla et al., 2016).

H. pylori is known to target mitochondria through its vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA), which triggers mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in mammalian cells (Calore et al., 2010). In gastric epithelial cells, VacA localizes to endosomal compartments and reaches the mitochondrial inner membrane where it forms anion-conductive channels (Calore et al., 2010; Domanska et al., 2010). VacA reduces mitochondrial membrane potential leading to decreased ATP production and cytochrome c release (Galmiche and Rassow, 2010). The pore-forming VacA toxin of the H. pylori, recruits and activates Drp1 resulting in mitochondrial fission, Bax activation, MOMP and cytochrome c release (Jain et al., 2011). VacA is also an efficient inducer of autophagy (Terebiznik et al., 2009). It is possible that H. pylori deregulate host cell mitochondria at early and late stage of infection with different dynamics. At the early stage of infection, H. pylori induce VacA dependent dysregulation of mitochondria hemostasis, which promotes transient increase in mitochondrial translocases, mitochondrial DNA replication maintenance factors such as POLG and TFAM. In contrast, at late infection stage the mechanism of dysregulation is VacA independent alteration in mitochondrial replication and import components, suggesting the involvement of additional H. pylori activities in mitochondrion-mediated effects (Figure 2).

mtDNA modulates H. pylori infection-associated inflammation

Mitochondria have been reported as modulators of cellular antibacterial immunity and inflammatory response (Andrieux et al., 2021). Abundant lines of research implicate the mitochondria as a key immune modulator in mouse models and human materials. Components of mtDNA such as TFAM, extracellular ATP, and numerous others have the capacity to elicit strong immune responses and, as such, and are thus considered mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (Galluzzi et al., 2012; West et al., 2015; De Gaetano et al., 2021). Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes essential subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation system and is also a major damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) that engages innate immune sensors when released into the cytoplasm, outside of cells or into the circulation. As a DAMP, mtDNA not only contributes to anti-viral resistance but also causes pathogenic inflammation in many disease contexts. Several studies also report that when mtDNA is discharged outside the cell, whether intact or damaged, it shows considerable pro- or anti-inflammatory effects in different models, thus highlighting the paradoxical interactions between these organelles and immune cells (Boudreau et al., 2014; Torralba et al., 2016). Mitochondrial DNA released into the cytosol is recognized by a DNA sensor cGAS, a cGAMP/STING which activates a pathway leading to the enhanced expression of type I interferons (Figure 2). Additionally, mtDNA activates NLRP3 inflammasome, which promotes the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-18 (West et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2018; Swanson et al., 2019). In the endosome, mtDNA can also bind to Toll-like receptor-9, triggering a pathway that results in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (De Gaetano et al., 2021). Stress-induced release of mtDNA or mtRNA into the cytoplasm can activate a type I IFN-I response that confers resistance to viral infection (West et al., 2015; Dhir et al., 2018; Sprenger et al., 2021). Inflammation caused by infection leads to the production of ROS and subsequent oxidative DNA damage (Sahan et al., 2018). ROS partially derives from active immune systems and host cells (Cindrilla et al., 2016). During infection, the stimulation of phagocytic cells, such as neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and macrophages, activates the NADPH oxidase (Nox) pathway, which catalyzes the reduction of oxygen using NADPH and generates superoxide (Brown and Griendling, 2009). In infected cells, the production of ROS is further amplified in the mitochondria via a mechanism involving NLRX1, a member of the intracellular Nod-like receptor (NLR) family that is localized in the mitochondria (Abdul-Sater et al., 2010). The resulting ROS can enter the nucleus and attack the DNA, generating oxidative DNA damage, such as 8-oxo-G, AP sites, and single-strand breaks (SSBs) (Kidane et al., 2014). Overall, further work is needed to uncover whether mtDNA and/or nuclear DNA damage continuously provides the fuel to exacerbate H. pylori infection-mediated inflammation.

Future perspective

Mitochondrial DNA integrity is critical to keep cellular homeostasis and prevent undesirable immune activation. Spontaneous or exogenous-stress-mediated mtDNA damage triggers different types of mitochondrial responses including fission or fusion to restore normal function and physiology. In addition, mtDNA damage activates DNA repair pathways such as BER to process the oxidative- or alkylating-agent-induced mtDNA damage and resolve some of the repair intermediates. Furthermore, unrepaired mtDNA base damage has an ability to deregulate the mtDNA replication dynamics leading to replication stress or blockage. mtDNA damage has been implicated in a variety of bacterial pathogens to drive inflammation and disease—for example, intracellular pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella typhimurium induces typhoid-toxin-dependent mtDNA damage, promotes the release of mtDNA into the cytosol, and triggers the cGAS-STING pathway (Xu et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2024). Mycobaterium abscessus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis also cause mtDNA damage, leading to inflammation via inflammasome activation or cGAS-STING signaling (Wiens and Ernst, 2016; Kim et al., 2020). H. pylori infection potentially impacts the mtDNA integrity and transitory alteration of mitochondrial import translocases and a dramatic upregulation of POLG and TFAM. Spontaneous as well as chronic infection induces excessive accumulation of mtDNA damage which leads to the release of mtDNA into the cytoplasm and activates cGAS/STING-dependent type I interferon response or activate other additional signaling pathways to promote inflammation- and infection-associated pathogenicity. Future risk assessment of patients may look for the potential link between a mutation in the MTS sequence of BER genes and the biological consequence of insufficient mt BER repair factors. In the future, the clinical relevance and the mechanism underlying the altered mtDNA dynamics with or without H. pylori infection probably will provide a new insight for cancer risk assessments and therapeutic planning across different stages of gastric cancer.

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI179899.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdul-Sater, A. A., Saïd-Sadier, N., Lam, V. M., Singh, B., Pettengill, M. A., Soares, F., et al. (2010). Enhancement of reactive oxygen species production and chlamydial infection by the mitochondrial Nod-like family member NLRX1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41637–41645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137885

Ahel, I., Rass, U., El-Khamisy, S. F., Katyal, S., Clements, P. M., McKinnon, P. J., et al. (2006). The neurodegenerative disease protein aprataxin resolves abortive DNA ligation intermediates. Nature 443, 713–716. doi: 10.1038/nature05164

Alexeyev, M., Shokolenko, I., Wilson, G., LeDoux, S. (2013). The maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity–critical analysis and update. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a012641. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012641

Anderson, C. T., Friedberg, E. C. (1980). The presence of nuclear and mitochondrial uracil-DNA glycosylase in extracts of human KB cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 875–888.

Andrieux, P., Chevillard, C., Cunha-Neto, E., Nunes, J. P. S. (2021). Mitochondria as a cellular hub in infection and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111338

Aoi, T., Marusawa, H., Sato, T., Chiba, T., Maruyama, M. (2006). Risk of subsequent development of gastric cancer in patients with previous gastric epithelial neoplasia. Gut 55, 588–589. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086884

Aryaman, J., Johnston, I. G., Jones, N. S. (2018). Mitochondrial heterogeneity. Front. Genet. 9, 718. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00718

Babbar, M., Basu, S., Yang, B., Croteau, D. L., Bohr, V. A. (2020). Mitophagy and DNA damage signaling in human aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 186, 111207. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111207

Ban-Ishihara, R., Ishihara, T., Sasaki, N., Mihara, K., Ishihara, N. (2013). Dynamics of nucleoid structure regulated by mitochondrial fission contributes to cristae reformation and release of cytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11863–11868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301951110

Barchiesi, A., Bazzani, V., Jabczynska, A., Borowski, L. S., Oeljeklaus, S., Warscheid, B., et al. (2021). DNA repair protein APE1 degrades dysfunctional abasic mRNA in mitochondria affecting oxidative phosphorylation. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167125. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167125

Barchiesi, A., Bazzani, V., Tolotto, V., Elancheliyan, P., Wasilewski, M., Chacinska, A., et al. (2020). Mitochondrial oxidative stress induces rapid intermembrane space/matrix translocation of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 protein through TIM23 complex. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 166713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.11.012

Bialkowski, K., Kasprzak, K. S. (1998). A novel assay of 8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine 5’-triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase (8-oxo-dGTPase) activity in cultured cells and its use for evaluation of cadmium(II) inhibition of this activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3194–3201. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3194

Blanke, S. R. (2005). Micro-managing the executioner: pathogen targeting of mitochondria. Trends Microbiol. 13, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.007

Bogenhagen, D. F. (2012). Mitochondrial DNA nucleoid structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819, 914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.11.005

Bohr, V. A. (2002). Repair of oxidative DNA damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, and some changes with aging in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 32, 804–812. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00787-6

Bohr, V. A., Anson, R. M. (1999). Mitochondrial DNA repair pathways. J. Bioenerg Biomembr. 31, 391–398. doi: 10.1023/A:1005484004167

Boudreau, L. H., Duchez, A. C., Cloutier, N., Soulet, D., Martin, N., Bollinger, J., et al. (2014). Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA-secreted phospholipase A2 to promote inflammation. Blood 124, 2173–2183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-573543

Brown, D. I., Griendling, K. K. (2009). Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radical Biol. Med. 47, 1239–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.023

Caldecott, K. W. (2008). Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 619–631. doi: 10.1038/nrg2380

Calore, F., Genisset, C., Casellato, A., Rossato, M., Codolo, G., Esposti, M. D., et al. (2010). Endosome-mitochondria juxtaposition during apoptosis induced by H. pylori VacA. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1707–1716. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.42

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N (2014). Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 513, 202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480

Casanova, A., Wevers, A., Navarro-Ledesma, S., Pruimboom, L. (2023). Mitochondria: It is all about energy. Front. Physiol. 14, 1114231. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1114231

Chakravarti, D., Ibeanu, G. C., Tano, K., Mitra, S. (1991). Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a human cDNA encoding the DNA repair protein N-methylpurine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 15710–15715. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98467-X

Chatre, L., Fernandes, J., Michel, V., Fiette, L., Ave, P., Arena, G., et al. (2017). Helicobacter pylori targets mitochondrial import and components of mitochondrial DNA replication machinery through an alternative VacA-dependent and a VacA-independent mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 7, 15901. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15567-3

Chatterjee, N., Walker, G. C. (2017). Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 58, 235–263. doi: 10.1002/em.22087

Chaturvedi, R., Asim, M., Piazuelo, M. B., Yan, F., Barry, D. P., Sierra, J. C., et al. (2014). Activation of EGFR and ERBB2 by Helicobacter pylori results in survival of gastric epithelial cells with DNA damage. Gastroenterology 146, 1739–51.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.005

Chaturvedi, R., Asim, M., Romero–Gallo, J., Barry, D. P., Hoge, S., de Sablet, T., et al. (2011). Spermine oxidase mediates the gastric cancer risk associated with helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology 141, 1696–708.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.045

Chen, H. Y., Hsieh, W. C., Liu, Y. C., Li, H. Y., Liu, P. Y., Hsu, Y. T., et al. (2024). Mitochondrial injury induced by a Salmonella genotoxin triggers the proinflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat. Commun. 15, 2778. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47190-y

Cindrilla, C., Rajendra Kumar, G., Rike, Z., Thomas, F. M. (2016). Subversion of host genome integrity by bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17. 10.1038/nrm.2016.100

Cogliati, S., Enriquez, J. A., Scorrano, L. (2016). Mitochondrial cristae: where beauty meets functionality. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.001

Cooke, M. S., Evans, M. D., Dizdaroglu, M., Lunec, J. (2003). Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 17, 1195–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev

Copeland, W. C. (2010). The mitochondrial DNA polymerase in health and disease. Subcell Biochem. 50, 211–222. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3471-711

Covacci, A., Rappuoli, R. (2000). Tyrosine-phosphorylated bacterial proteins: Trojan horses for the host cell. J. Exp. Med. 191, 587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.587

Das, B. B., Dexheimer, T. S., Maddali, K., Pommier, Y. (2010). Role of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (TDP1) in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19790–19795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009814107

De Gaetano, A., Solodka, K., Zanini, G., Selleri, V., Mattioli, A. V., Nasi, M., et al. (2021). Molecular mechanisms of mtDNA-mediated inflammation. Cells 10. doi: 10.3390/cells10112898

de Souza-Pinto, N. C., Mason, P. A., Hashiguchi, K., Weissman, L., Tian, J., Guay, D., et al. (2009). Novel DNA mismatch-repair activity involving YB-1 in human mitochondria. DNA Repair (Amst). 8, 704–719. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.021

Dhir, A., Dhir, S., Borowski, L. S., Jimenez, L., Teitell, M., Rotig, A., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signalling in humans. Nature 560, 238–242. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0363-0

Diaz-Talavera, A., Montero-Conde, C., Leandro-Garcia, L. J., Robledo, M. (2022). PrimPol: A breakthrough among DNA replication enzymes and a potential new target for cancer therapy. Biomolecules 12. doi: 10.3390/biom12020248

Dicksved, J., Lindberg, M., Rosenquist, M., Enroth, H., Jansson, J. K., Engstrand, L. (2009). Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 509–516. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007302-0

Domanska, G., Motz, C., Meinecke, M., Harsman, A., Papatheodorou, P., Reljic, B., et al. (2010). Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin/subunit p34: targeting of an anion channel to the inner mitochondrial membrane. PloS Pathog. 6, e1000878. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000878

Dorer, M. S., Fero, J., Salama, N. R. (2010). DNA damage triggers genetic exchange in Helicobacter pylori. PloS Pathog. 6, e1001026. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001026

Dou, H., Mitra, S., Hazra, T. K. (2003). Repair of oxidized bases in DNA bubble structures by human DNA glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49679–49684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308658200

Druzhyna, N. M., Wilson, G. L., LeDoux, S. P. (2008). Mitochondrial DNA repair in aging and disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.002

Fielden, L. F., Kang, Y., Newton, H. J., Stojanovski, D. (2017). Targeting mitochondria: how intravacuolar bacterial pathogens manipulate mitochondria. Cell Tissue Res. 367, 141–154. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2475-x

Filograna, R., Mennuni, M., Alsina, D., Larsson, N. G. (2021). Mitochondrial DNA copy number in human disease: the more the better? FEBS Lett. 595, 976–1002. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14021

Fischer, S. F., Vier, J., Kirschnek, S., Klos, A., Hess, S., Ying, S., et al. (2004). Chlamydia inhibit host cell apoptosis by degradation of proapoptotic BH3-only proteins. J. Exp. Med. 200, 905–916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040402

Fontana, G. A., Gahlon, H. L. (2020). Mechanisms of replication and repair in mitochondrial DNA deletion formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 11244–11258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa804

Fox, J. G., Wang, T. C. (2007). Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111

Fridlich, R., Annamalai, D., Roy, R., Bernheim, G., Powell, S. N. (2015). BRCA1 and BRCA2 protect against oxidative DNA damage converted into double-strand breaks during DNA replication. DNA Repair (Amst). 30, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.03.002

Fujikawa, K., Kamiya, H., Yakushiji, H., Fujii, Y., Nakabeppu, Y., Kasai, H. (1999). The oxidized forms of dATP are substrates for the human MutT homologue, the hMTH1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18201–18205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18201

Fujikawa, K., Kamiya, H., Yakushiji, H., Nakabeppu, Y., Kasai, H. (2001). Human MTH1 protein hydrolyzes the oxidized ribonucleotide, 2-hydroxy-ATP. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 449–454. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.2.449

Galick, H. A., Kathe, S., Liu, M., Robey-Bond, S., Kidane, D., Wallace, S. S., et al. (2013). Germ-line variant of human NTH1 DNA glycosylase induces genomic instability and cellular transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14314–14319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306752110

Galluzzi, L., Kepp, O., Kroemer, G. (2012). Mitochondria: master regulators of danger signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 780–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm3479

Galmiche, A., Rassow, J. (2010). Targeting of Helicobacter pylori VacA to mitochondria. Gut Microbes 1, 392–395. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.6.13894

Galmiche, A., Rassow, J., Doye, A., Cagnol, S., Chambard, J. C., Contamin, S., et al. (2000). The N-terminal 34 kDa fragment of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin targets mitochondria and induces cytochrome c release. EMBO J. 19, 6361–6370. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6361

Gao, Y., Katyal, S., Lee, Y., Zhao, J., Rehg, J. E., Russell, H. R., et al. (2011). DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair. Nature 471, 240–244. doi: 10.1038/nature09773

Glassner, B. J., Rasmussen, L. J., Najarian, M. T., Posnick, L. M., Samson, L. D. (1998). Generation of a strong mutator phenotype in yeast by imbalanced base excision repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9997–10002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9997

Graziewicz, M. A., Longley, M. J., Copeland, W. C. (2006). DNA polymerase gamma in mitochondrial DNA replication and repair. Chem. Rev. 106, 383–405. doi: 10.1021/cr040463d

Gredilla, R. (2010). DNA damage and base excision repair in mitochondria and their role in aging. J. Aging Res. 2011, 257093. doi: 10.4061/2011/257093

Guilliam, T. A., Jozwiakowski, S. K., Ehlinger, A., Barnes, R. P., Rudd, S. G., Bailey, L. J., et al. (2015). Human PrimPol is a highly error-prone polymerase regulated by single-stranded DNA binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1056–1068. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1321

Hiyama, T., Tanaka, S., Shima, H., Kose, K., Kitadai, Y., Ito, M., et al. (2003). Somatic mutation of mitochondrial DNA in Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis in patients with and without gastric cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 12, 169–174. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.12.2.169

Hudson, J. J., Chiang, S. C., Wells, O. S., Rookyard, C., El-Khamisy, S. F. (2012). SUMO modification of the neuroprotective protein TDP1 facilitates chromosomal single-strand break repair. Nat. Commun. 3, 733. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1739

Jacobs, A. L., Schar, P. (2012). DNA glycosylases: in DNA repair and beyond. Chromosoma 121, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0347-4

Jain, P., Luo, Z. Q., Blanke, S. R. (2011). Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) engages the mitochondrial fission machinery to induce host cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16032–16037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105175108

Jalal, S., Earley, J. N., Turchi, J. J. (2011). DNA repair: from genome maintenance to biomarker and therapeutic target. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 6973–6984. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0761

Kaguni, L. S. (2004). DNA polymerase gamma, the mitochondrial replicase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 293–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161455

Kaufman, B. A., Van Houten, B. (2017). POLB: A new role of DNA polymerase beta in mitochondrial base excision repair. DNA Repair (Amst). 60, A1–A5. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.11.002

Kavli, B., Slupphaug, G., Mol, C. D., Arvai, A. S., Peterson, S. B., Tainer, J. A., et al. (1996). Excision of cytosine and thymine from DNA by mutants of human uracil-DNA glycosylase. EMBO J. 15, 3442–3447. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00710.x

Khanna, K. K., Jackson, S. P. (2001). DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat. Genet. 27, 247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798

Kidane, D., Murphy, D. L., Sweasy, J. B. (2014). Accumulation of abasic sites induces genomic instability in normal human gastric epithelial cells during Helicobacter pylori infection. Oncogenesis 3, e128–e12e. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2014.42

Kim, B. R., Kim, B. J., Kook, Y. H., Kim, B. J. (2020). Mycobacterium abscessus infection leads to enhanced production of type 1 interferon and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in murine macrophages via mitochondrial oxidative stress. PloS Pathog. 16, e1008294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008294

Klungland, A., Bjelland, S. (2007). Oxidative damage to purines in DNA: role of mammalian Ogg1. DNA Repair (Amst). 6, 481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.012

Klungland, A., Rosewell, I., Hollenbach, S., Larsen, E., Daly, G., Epe, B., et al. (1999). Accumulation of premutagenic DNA lesions in mice defective in removal of oxidative base damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13300–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13300

Koeppel, M., Garcia-Alcalde, F., Glowinski, F., Schlaermann, P., Meyer, T. F. (2015). Helicobacter pylori infection causes characteristic DNA damage patterns in human cells. Cell Rep. 11, 1703–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.030

Kolesnikov, A. A. (2016). The mitochondrial genome. Nucleoid. Biochem. (Mosc). 81, 1057–1065. doi: 10.1134/S0006297916100047

Kurosaka, M., Ohno, O., Hirohata, K. (1991). Arthroscopic evaluation of synovitis in the knee joints. Arthroscopy 7, 162–170. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90104-6

Lakshmipathy, U., Campbell, C. (2001). Antisense-mediated decrease in DNA ligase III expression results in reduced mitochondrial DNA integrity. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 668–676. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.668

Ledoux, S. P., Shen, C. C., Grishko, V. I., Fields, P. A., Gard, A. L., Wilson, G. L. (1998). Glial cell-specific differences in response to alkylation damage. Glia 24, 304–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199811)24:3<304::AID-GLIA4>3.0.CO;2-1

LeDoux, S. P., Wilson, G. L., Beecham, E. J., Stevnsner, T., Wassermann, K., Bohr, V. A. (1992). Repair of mitochondrial DNA after various types of DNA damage in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Carcinogenesis 13, 1967–1973. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.11.1967

Legros, F., Malka, F., Frachon, P., Lombes, A., Rojo, M. (2004). Organization and dynamics of human mitochondrial DNA. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2653–2662. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01134

Li, M., Zhong, Z., Zhu, J., Xiang, D., Dai, N., Cao, X., et al. (2010). Identification and characterization of mitochondrial targeting sequence of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14871–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069591

Lia, D., Reyes, A., de Melo Campos, J. T. A., Piolot, T., Baijer, J., Radicella, J. P., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial maintenance under oxidative stress depends on mitochondrially localised alpha-OGG1. J. Cell Sci. 131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.213538

Lieber, M. R. (2010). The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131

Lindahl, T. (1993). Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 362, 709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0

Lindahl, T., Wood, R. D. (1999). Quality control by DNA repair. Science 286, 1897–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1897

Llanos-Gonzalez, E., Henares-Chavarino, A. A., Pedrero-Prieto, C. M., Garcia-Carpintero, S., Frontinan-Rubio, J., Sancho-Bielsa, F. J., et al. (2019). Interplay between mitochondrial oxidative disorders and proteostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1444. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01444

Longley, M. J., Clark, S., Yu Wai Man, C., Hudson, G., Durham, S. E., Taylor, R. W., et al. (2006). Mutant POLG2 disrupts DNA polymerase gamma subunits and causes progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78, 1026–1034. doi: 10.1086/504303

Longley, M. J., Prasad, R., Srivastava, D. K., Wilson, S. H., Copeland, W. C. (1998). Identification of 5’-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase gamma and its role in mitochondrial base excision repair in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12244–12248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12244

MaChado, A. M., Figueiredo, C., Touati, E., Maximo, V., Sousa, S., Michel, V., et al. (2009). Helicobacter pylori infection induces genetic instability of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in gastric cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 2995–3002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2686

Mandal, S. M., Hegde, M. L., Chatterjee, A., Hegde, P. M., Szczesny, B., Banerjee, D., et al. (2012). Role of human DNA glycosylase Nei-like 2 (NEIL2) and single strand break repair protein polynucleotide kinase 3’-phosphatase in maintenance of mitochondrial genome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2819–2829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.272179

Martinez-Jimenez, M. I., Calvo, P. A., Garcia-Gomez, S., Guerra-Gonzalez, S., Blanco, L. (2018). The Zn-finger domain of human PrimPol is required to stabilize the initiating nucleotide during DNA priming. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 4138–4151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky230

Maynard, S., Schurman, S. H., Harboe, C., de Souza-Pinto, N. C., Bohr, V. A. (2009). Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage and association with cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis 30, 2–10. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn250

McKinney, E. A., Oliveira, M. T. (2013). Replicating animal mitochondrial DNA. Genet. Mol. Biol. 36, 308–315. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572013000300002

Michaels, M. L., Tchou, J., Grollman, A. P., Miller, J. H. (1992). A repair system for 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyguanine. Biochemistry 31, 10964–10968. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a004

Nakabeppu, Y. (2014). Cellular levels of 8-oxoguanine in either DNA or the nucleotide pool play pivotal roles in carcinogenesis and survival of cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 12543–12557. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712543

Nakabeppu, Y., Kajitani, K., Sakamoto, K., Yamaguchi, H., Tsuchimoto, D. (2006). MTH1, an oxidized purine nucleoside triphosphatase, prevents the cytotoxicity and neurotoxicity of oxidized purine nucleotides. DNA Repair (Amst). 5, 761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.03.003

Nakabeppu, Y., Tsuchimoto, D., Yamaguchi, H., Sakumi, K. (2007). Oxidative damage in nucleic acids and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 919–934. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21191

Nakada, K., Inoue, K., Ono, T., Isobe, K., Ogura, A., Goto, Y. I., et al. (2001). Inter-mitochondrial complementation: Mitochondria-specific system preventing mice from expression of disease phenotypes by mutant mtDNA. Nat. Med. 7, 934–940. doi: 10.1038/90976

Neupert, W. (1997). Protein import into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 863–917. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.863

Nicholls, T. J., Zsurka, G., Peeva, V., Scholer, S., Szczesny, R. J., Cysewski, D., et al. (2014). Linear mtDNA fragments and unusual mtDNA rearrangements associated with pathological deficiency of MGME1 exonuclease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 6147–6162. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu336

Nishioka, K., Ohtsubo, T., Oda, H., Fujiwara, T., Kang, D., Sugimachi, K., et al. (1999). Expression and differential intracellular localization of two major forms of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase encoded by alternatively spliced OGG1 mRNAs. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10, 1637–1652. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1637

Ohtsubo, T., Nishioka, K., Imaiso, Y., Iwai, S., Shimokawa, H., Oda, H., et al. (2000). Identification of human MutY homolog (hMYH) as a repair enzyme for 2-hydroxyadenine in DNA and detection of multiple forms of hMYH located in nuclei and mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 1355–1364. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1355

Ono, T., Isobe, K., Nakada, K., Hayashi, J. I. (2001). Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nat. Genet. 28, 272–275. doi: 10.1038/90116

Peek, R. M., Jr., Blaser, M. J. (2002). Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703

Pirsel, M., Bohr, V. A. (1993). Methyl methanesulfonate adduct formation and repair in the DHFR gene and in mitochondrial DNA in hamster cells. Carcinogenesis 14, 2105–2108. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.10.2105

Prachar, J. (2016). Ultrastructure of mitochondrial nucleoid and its surroundings. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 35, 273–286. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2016008

Prakash, A., Doublie, S. (2015). Base excision repair in the mitochondria. J. Cell Biochem. 116, 1490–1499. doi: 10.1002/jcb.v116.8

Prasad, R., Caglayan, M., Dai, D. P., Nadalutti, C. A., Zhao, M. L., Gassman, N. R., et al. (2017). DNA polymerase beta: A missing link of the base excision repair machinery in mammalian mitochondria. DNA Repair (Amst). 60, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.10.011

Richter, C., Park, J. W., Ames, B. N. (1988). Normal oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA is extensive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 6465–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465

Robberson, D. L., Kasamatsu, H., Vinograd, J. (1972). Replication of mitochondrial DNA. Circular replicative intermediates in mouse L cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69, 737–741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.3.737

Sahan, A. Z., Hazra, T. K., Das, S. (2018). The pivotal role of DNA repair in infection mediated-inflammation and cancer.(Report)(Brief article). Front. Microbiol. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00663

Scott, I., Youle, R. J. (2010). Mitochondrial fission and fusion. Essays Biochem. 47, 85–98. doi: 10.1042/bse0470085

Sharma, P., Sampath, H. (2019). Mitochondrial DNA integrity: role in health and disease. Cells 8. doi: 10.3390/cells8020100

Shokolenko, I. N., Alexeyev, M. F., Robertson, F. M., LeDoux, S. P., Wilson, G. L. (2003). The expression of Exonuclease III from E. coli in mitochondria of breast cancer cells diminishes mitochondrial DNA repair capacity and cell survival after oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amst). 2, 471–482. doi: 10.1016/S1568-7864(03)00019-3

Shokolenko, I. N., Fayzulin, R. Z., Katyal, S., McKinnon, P. J., Wilson, G. L., Alexeyev, M. F. (2013). Mitochondrial DNA ligase is dispensable for the viability of cultured cells but essential for mtDNA maintenance. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26594–26605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472977

Simsek, D., Furda, A., Gao, Y., Artus, J., Brunet, E., Hadjantonakis, A. K., et al. (2011). Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair. Nature 471, 245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature09794

Simsek, D., Jasin, M. (2011). DNA ligase III: a spotty presence in eukaryotes, but an essential function where tested. Cell Cycle 10, 3636–3644. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.21.18094

Song, J., Bent, A. F. (2014). Microbial pathogens trigger host DNA double-strand breaks whose abundance is reduced by plant defense responses. PloS Pathog. 10, e1004030. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004030

Spelbrink, J. N. (2010). Functional organization of mammalian mitochondrial DNA in nucleoids: history, recent developments, and future challenges. IUBMB Life. 62, 19–32. doi: 10.1002/iub.v62:1

Spelbrink, J. N., Li, F. Y., Tiranti, V., Nikali, K., Yuan, Q. P., Tariq, M., et al. (2001). Human mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with mutations in the gene encoding Twinkle, a phage T7 gene 4-like protein localized in mitochondria. Nat. Genet. 28, 223–231. doi: 10.1038/90058

Spier, A., Stavru, F., Cossart, P. (2019). Interaction between intracellular bacterial pathogens and host cell mitochondria. Microbiol. Spectr. 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAI-0016-2019

Sprenger, H. G., MacVicar, T., Bahat, A., Fiedler, K. U., Hermans, S., Ehrentraut, D., et al. (2021). Cellular pyrimidine imbalance triggers mitochondrial DNA-dependent innate immunity. Nat. Metab. 3, 636–650. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00385-9

Stavru, F., Bouillaud, F., Sartori, A., Ricquier, D., Cossart, P. (2011). Listeria monocytogenes transiently alters mitochondrial dynamics during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3612–3617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100126108

Stuart, J. A., Mayard, S., Hashiguchi, K., Souza-Pinto, N. C., Bohr, V. A. (2005). Localization of mitochondrial DNA base excision repair to an inner membrane-associated particulate fraction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 3722–3732. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki683

Svilar, D., Goellner, E. M., Almeida, K. H., Sobol, R. W. (2011). Base excision repair and lesion-dependent subpathways for repair of oxidative DNA damage. Antioxid Redox Signal. 14, 2491–2507. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3466

Swanson, K. V., Deng, M., Ting, J. P. (2019). The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0

Sykora, P., Croteau, D. L., Bohr, V. A., Wilson, D. M., 3rd (2011). Aprataxin localizes to mitochondria and preserves mitochondrial function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7437–7442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100084108

Sykora, P., Kanno, S., Akbari, M., Kulikowicz, T., Baptiste, B. A., Leandro, G. S., et al. (2017). DNA polymerase beta participates in mitochondrial DNA repair. Mol. Cell Biol. 37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00237-17

Szczepanowska, K., Trifunovic, A. (2015). Different faces of mitochondrial DNA mutators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 1362–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.05.016

Taylor, R. W., Turnbull, D. M. (2005). Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrg1606

Terebiznik, M. R., Raju, D., Vazquez, C. L., Torbricki, K., Kulkarni, R., Blanke, S. R., et al. (2009). Effect of Helicobacter pylori’s vacuolating cytotoxin on the autophagy pathway in gastric epithelial cells. Autophagy 5, 370–379. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7663

Thorslund, T., Sunesen, M., Bohr, V. A., Stevnsner, T. (2002). Repair of 8-oxoG is slower in endogenous nuclear genes than in mitochondrial DNA and is without strand bias. DNA Repair (Amst). 1, 261–273. doi: 10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00003-4

Tilokani, L., Nagashima, S., Paupe, V., Prudent, J. (2018). Mitochondrial dynamics: overview of molecular mechanisms. Essays Biochem. 62, 341–360. doi: 10.1042/EBC20170104

Toller, I. M., Neelsen, K. J., Steger, M., Hartung, M. L., Hottiger, M. O., Stucki, M., et al. (2011). Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14944–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100959108

Torralba, D., Baixauli, F., Sanchez-Madrid, F. (2016). Mitochondria know no boundaries: mechanisms and functions of intercellular mitochondrial transfer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 107. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00107

Wallace, D. C. (2005). A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751

Wang, Y., Bogenhagen, D. F. (2006). Human mitochondrial DNA nucleoids are linked to protein folding machinery and metabolic enzymes at the mitochondrial inner membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25791–25802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604501200

Wang, Y., Xu, H., Liu, T., Huang, M., Butter, P. P., Li, C., et al. (2018). Temporal DNA-PK activation drives genomic instability and therapy resistance in glioma stem cells. JCI Insight 3. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98096

West, A. P., Khoury-Hanold, W., Staron, M., Tal, M. C., Pineda, C. M., Lang, S. M., et al. (2015). Mitochondrial DNA stress primes the antiviral innate immune response. Nature 520, 553–557. doi: 10.1038/nature14156

Whitaker, A. M., Schaich, M. A., Smith, M. R., Flynn, T. S., Freudenthal, B. D. (2017). Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage: from mechanism to disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 22, 1493–1522. doi: 10.2741/4555

Wiens, K. E., Ernst, J. D. (2016). The mechanism for type I interferon induction by mycobacterium tuberculosis is bacterial strain-dependent. PloS Pathog. 12, e1005809. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005809

Wonnapinij, P., Chinnery, P. F., Samuels, D. C. (2008). The distribution of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy due to random genetic drift. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.007

Woodbine, L., Brunton, H., Goodarzi, A. A., Shibata, A., Jeggo, P. A. (2011). Endogenously induced DNA double strand breaks arise in heterochromatic DNA regions and require ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Artemis for their repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 6986–6997. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr331

Xu, L., Li, M., Yang, Y., Zhang, C., Xie, Z., Tang, J., et al. (2022). Salmonella Induces the cGAS-STING-Dependent Type I Interferon Response in Murine Macrophages by Triggering mtDNA Release. mBio 13, e0363221. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03632-21

Yakes, F. M., Van Houten, B. (1997). Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 514–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.514

Yang, W., Gao, Y. (2018). Translesion and repair DNA polymerases: diverse structure and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 239–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012405

Yoneda, M., Miyatake, T., Attardi, G. (1994). Complementation of mutant and wild-type human mitochondrial DNAs coexisting since the mutation event and lack of complementation of DNAs introduced separately into a cell within distinct organelles. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 2699–2712. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2699-2712.1994

Zhang, H., Barcelo, J. M., Lee, B., Kohlhagen, G., Zimonjic, D. B., Popescu, N. C., et al. (2001). Human mitochondrial topoisomerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10608–10613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191321998

Zhao, L., Sumberaz, P. (2020). Mitochondrial DNA damage: prevalence, biological consequence, and emerging pathways. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33, 2491–2502. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00083

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA damage and repair, H. pylori, genomic instability, cytosolic DNA, innate immune signaling, Type I interferon response, base excision DNA repair, cGAS-STING

Citation: Shahi A and Kidane D (2025) Decoding mitochondrial DNA damage and repair associated with H. pylori infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14:1529441. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1529441

Received: 16 November 2024; Accepted: 19 December 2024;

Published: 21 January 2025.

Edited by:

Maurizio Sanguinetti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Nadine Laure Samara, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesPeng Li, Westlake University, China

Copyright © 2025 Shahi and Kidane. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dawit Kidane, ZGF3aXQua2lkYW5lLW11bGF0QGhvd2FyZC5lZHU=

Aashirwad Shahi

Aashirwad Shahi Dawit Kidane

Dawit Kidane