- Department of Pulmonology, Affiliated Children's Hospital, Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing, China

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurodegenerative disease that results in progressive and symmetric muscle weakness and atrophy of the proximal limbs and trunk due to degeneration of spinal alpha-motor neurons. Children are classified into types 1–3, from severe to mild, according to the time of onset and motor ability. Children with type 1 are the most severe, are unable to sit independently, and experience a series of respiratory problems, such as hypoventilation, reduced cough, and sputum congestion. Respiratory failure is easily complicated by respiratory infections and is a major cause of death in children with SMA. Most type 1 children die within 2 years of age. Type 1 children with SMA usually require hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infections and invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation in severe cases. These children are frequently infected with drug-resistant bacteria due to repeated hospitalizations and require long hospital stays requiring invasive ventilation. In this paper, we report a case of nebulization combined with intravenous polymyxin B in a child with spinal muscular atrophy with extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia, hoping to provide a reference for the treatment of children with extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia.

1 Clinical data

1.1 General data

The child was a 4-year-old boy who was admitted to the hospital chiefly due to “postnatal hypotonia and intermittent asthmatic cough with dyspnea for 1 month.” The child, G1P1, was born by cesarean section at full term with postnatal hypotonia and delayed gross motor development and was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy (type I) at the age of 10 months after completion of genetic testing. One year prior, the child underwent tracheal intubation and was connected to an invasive ventilator for treatment for 26 days. The tracheal cannula was removed, and the child was discharged without a ventilator and was treated for the original disease with risdiplam orally for 8 months. One month before admission, the child developed a paroxysmal cough without obvious inducement, with more white mucous sputum aspirated, with fever, wheezing, and labored breathing. The child was hospitalized in a local tertiary hospital, and sputum culture showed Acinetobacter baumannii. Piperacillin sodium and tazobactam sodium, cefoperazone sulbactam sodium, tigecycline for anti-infection, fluconazole, and micafungin for antifungal infection were given successively. On the second day of hospitalization, the child’s dyspnea worsened. The dyspnea was relieved after the tracheal cannula was connected to an invasive ventilator for assisted ventilation. The child’s dyspnea worsened after removal of the tracheal cannula and ventilator twice, and the child was reintubated and connected to ventilator-assisted ventilation. The parents refused tracheotomy and transferred the child to our hospital. The child was admitted to the hospital with “bronchopneumonia and spinal muscular atrophy.”

The findings of the physical examination on admission were as follows: height 103 cm (P10–P25), weight 10 kg (<p3), respiration 40 bpm, heart rate 170 bpm, clear consciousness, slightly irritable, shortness of breath, positive nasal fan, and three depression signs. The patient had a bell-shaped thorax, coarse breath sounds in both lungs, scattered medium-fine moist rales, and wheezing sounds that were heard. There was no significant abnormalities in the cardiac and abdominal examinations; there was decreased muscle tone of the extremities, grade II muscle strength of the distal upper extremities, and grade I muscle strength of the proximal upper extremities and lower extremities. Tendon reflexes were not elicited, and both fingers were claw-shaped with contracture.

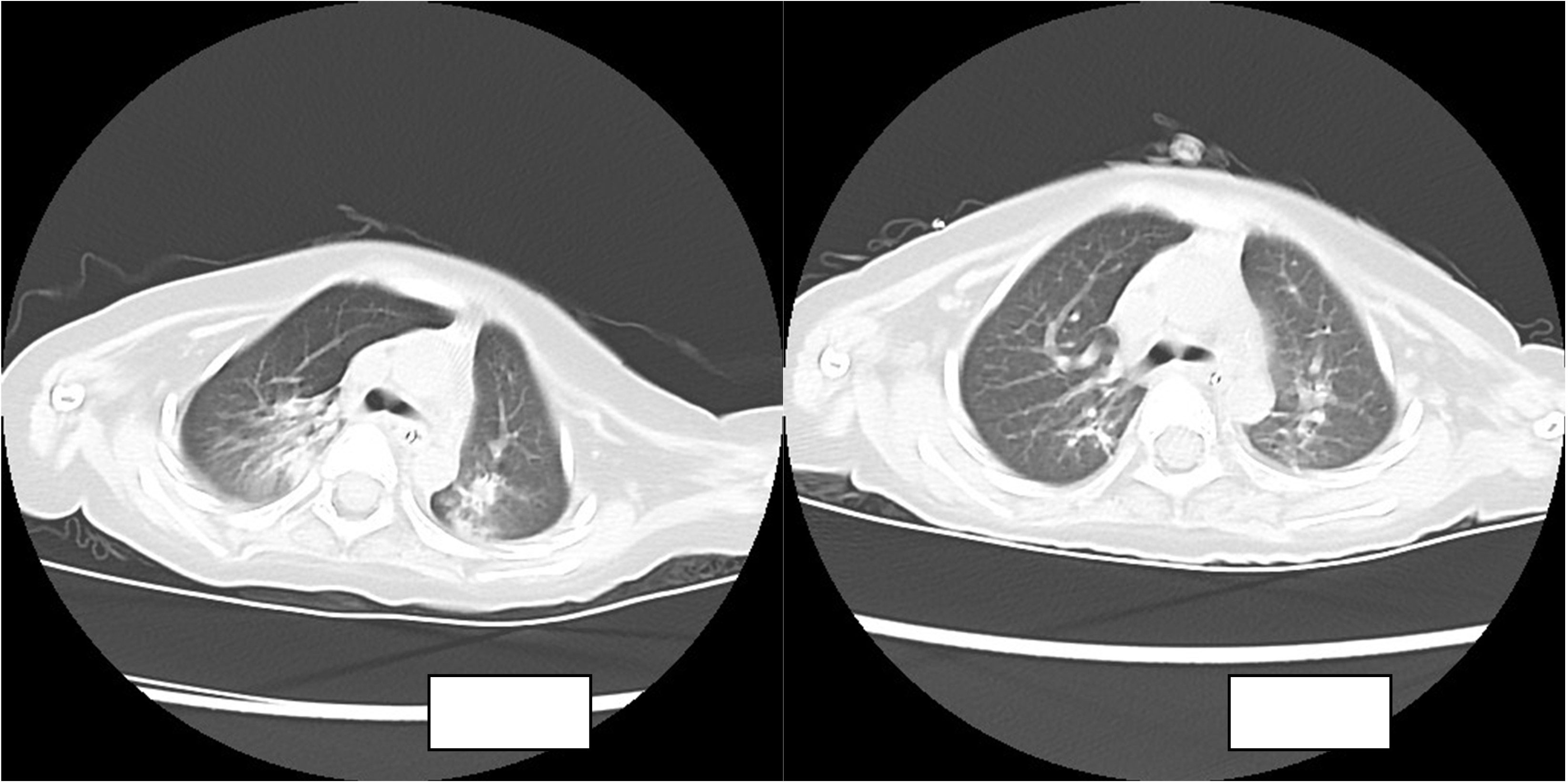

The routine blood results were as follows: WBC 8.21 × 109/l, N 36.1%, L 54%, HGB 110 g/l, PLT 557 × 109/l, CRP 2 mg/l. The blood gas analysis showed the following: P02 57.8 mmHg, PC02 44.1 mmHg, PH 7.413, HC03 27.6 mmol/l, S02 90.4%, and BE 3.1 mmol/l. The chest CT showed the following: there was a right lung upper lobe shadow, the bilateral lung lower lobe volume was decreased, a dense shadow was seen, a bronchial inflation phase was seen inside, there were bronchial gathering signs, there was an impression of pneumonia, and there was atelectasis of the bilateral lower lobes.

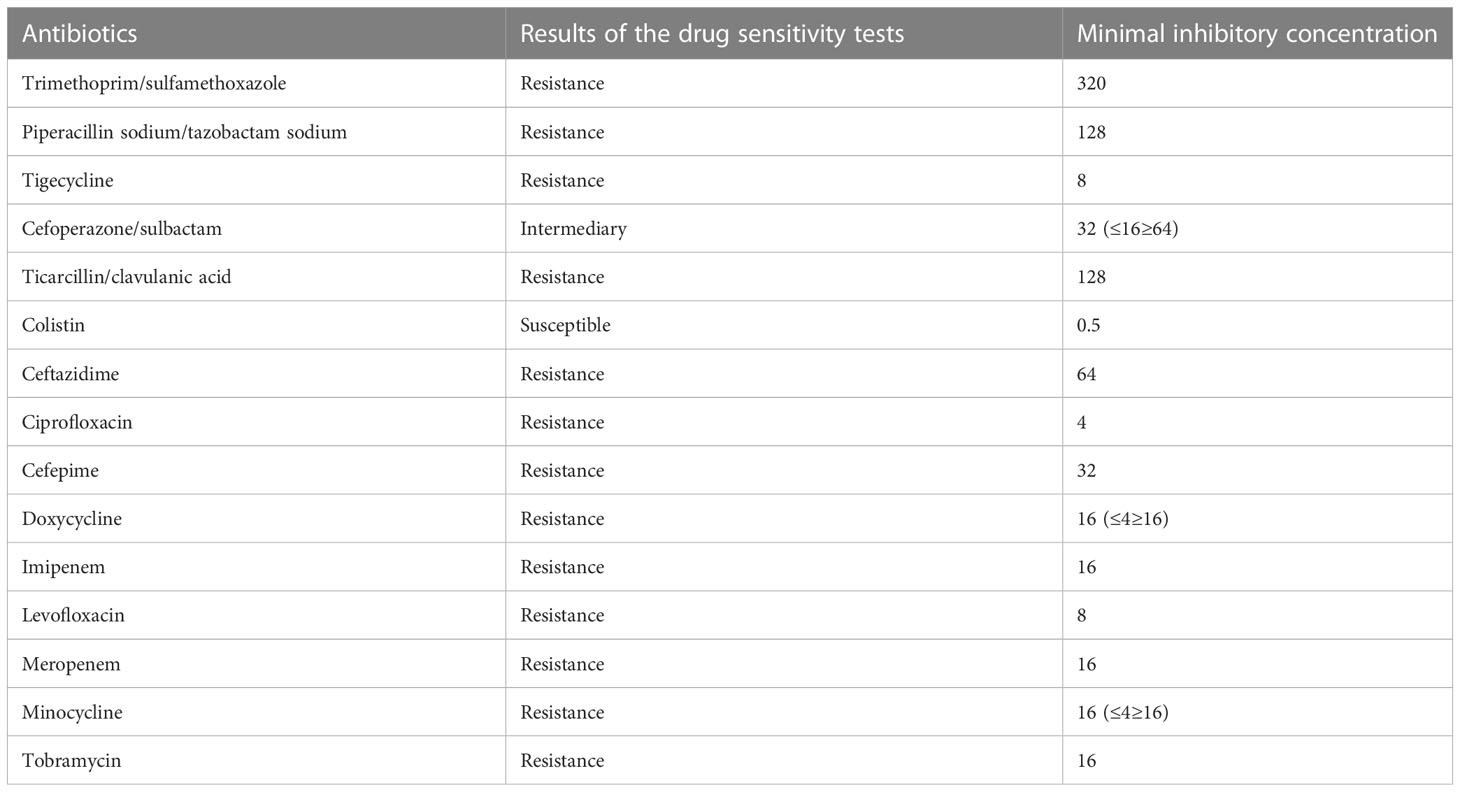

The child was admitted to the hospital with continuous invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation and was given cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium ivgtt for anti-infection and intensive airway management. On the fourth day after admission, the bronchial lavage fluid was positive for A. baumannii, and sputum culture suggested a S. aureus and A. baumannii complex. Levofloxacin and tigecycline were added according to the drug susceptibility test. The child still had intermittent fever, and multiple bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and sputum bacterial cultures suggested the presence of the Acinetobacter baumannii complex, high- throughput gene detection tests on the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid suggested a high confidence level of the Acinetobacter baumannii. On the 44th day after admission, the child’s temperature was normal and his respiration was stable. Therefore, the tracheal cannula was removed, and the patient was changed to non-invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation. After maintenance for 4 days, the child was again fevered and intubated and connected to invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation due to dyspnea. The bacterial culture taken from the tip of the tracheal cannula on the 49th day of admission showed the following: A. baumannii complex, colistin-sensitive, cefoperazone, and sulbactam; the remaining isolates were resistant (including to tigecycline). Table 1 shows our results. Tigecycline and levofloxacin were discontinued, intravenous polymyxin B combined with nebulization were added (intravenous administration: the first intravenous loading dose was 2.5 mg/kg (equivalent to 25,000 U/kg, 250,000 U/dose actually administered), and a maintenance dose at 1.25 mg/kg was given once after 12 h (equivalent to 12,500 U/kg/dose, 125,000 U/dose actually administered). For nebulization, 250,000 U/dose was dissolved in 5 ml saline; the solution was nebulized through a nebulizer device connected to a ventilator line, once/12 h) for anti-infectious treatment. The child’s guardian agreed to the treatment and signed an informed consent form. In the early stage of nebulization of polymyxin B, the respiratory rate increased and the blood oxygen concentration decreased. Therefore, a β2 agonist was inhaled 20 min before nebulization to reduce airway complications and oxygenated nebulization. The late stage of treatment went smoothly. After 5 days of polymyxin B treatment, the sputum culture was negative on two consecutive occasions and the reexamination of chest imaging showed improvement. The tracheal cannula was successfully removed on the 61st day of admission, and the patient was changed to non-invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation. Polymyxin B was discontinued after 14 days of use, and sputum culture showed no extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, with rechecked routine blood results as follows: WBC 4.89 × 109/l, N 25.1%, L 62.4%, HGB 109 g/l, PLT 498 × 109/l, CRP 0.46 mg/l; renal function results showed the following: BUN 5.83 mmol/l, Cr 12.2 µmol/l. The child was discharged uneventfully after a 75-day hospital stay. Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of the patient's chest CT before and after treatment.

Table 1 Results of the bacterial culture taken from the tip of tracheal cannula on the 49th day of admission: Acinetobacter baumannii complex, solistin-sensitive, cefoperazone, and sulbactam; the remaining are resistant (including tigecycline).

1.2 Literature review

The search terms “Polymyxin B,” “Acinetobacter baumannii,” “Extensively drug-resistant,” and “Pneumonia” were searched in PubMed and Web of Science, and the search terms “Polymyxin B,” “Acinetobacter baumannii,” “Extensively drug-resistant,” and “Pneumonia in children” were searched in the CNKI, SinoMed, and Wanfang databases, with the searching time being from database establishment until 01/09/2022.

The search did not include nebulization combined with intravenous polymyxin B for the treatment of childhood-associated pneumonia. Studies reporting nebulization of polymyxin B for the auxiliary treatment of pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections have focused on adult patients. A recent prospective cohort study (Hasan et al., 2021) and a retrospective observational study in China (Zhou et al., 2021) showed that intravenous polymyxin B combined with nebulization therapy resulted in better clinical efficiency and microbial clearance, shortened the extubation time and ICU stay, and reduced the incidence of secondary infections without increasing the risk of renal damage. There are only a few clinical studies on the efficacy and safety of intravenous polymyxin B alone in the treatment of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB) pneumonia in children, and these studies showed clinical efficacy rates of 47.8%–53.8%, microbial clearance rates of 30.8%–70.9%, in-hospital mortality rates of 7.3%–32.7%, and incidences of adverse events of 13.5%–27.3% (Liu et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022).

2 Discussion

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a severe neuromuscular disorder due to a defect in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene (Mercuri et al., 2018). Children with spinal muscular atrophy are easily complicated with upper and lower respiratory tract infections due to reduced cough and impaired secretion clearance, and according to statistics, the proportion of Chinese patients with type 1–3 SMA hospitalized with pulmonary infections ranges from 24.7% to 61.5% (Ge et al., 2012). When SMA patients present with pulmonary infections, in principle, pathogenetic examinations and infection assessments should be performed on a comprehensive case-by-case basis (Guo et al., 2016). Our department has analyzed the clinical characteristics of children admitted with spinal muscular atrophy and pneumonia and published related articles. All six children with long-term tracheal intubation and tracheotomy developed ventilator-associated pneumonia, and all of them had multidrug-resistant bacterial infections that required long-term use and replacement with multiple antibiotics based on the culture and drug susceptibility results, including four cases of Acinetobacter baumannii infection (Guo and Cao, 2020). Active treatment of pulmonary infections is important to achieve the early withdrawal criteria in children with tracheal intubation, with the aim of achieving a better long-term survival.

Acinetobacter baumannii has a strong ability to acquire drug resistance and clonal transmission, and multidrug resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and fully resistant Acinetobacter baumannii is endemic worldwide and has become one of the most important pathogens of nosocomial infections in China (Peleg et al., 2008). The most common site of nosocomial A. baumannii infection is the lung, and it is an important pathogenic bacterium of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), especially ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (Chen et al., 2012). The results of the 2021 CHINET China bacterial drug resistance surveillance (Hu et al., 2021) suggest that A. baumannii ranks fifth in clinical isolates in China, second only to Klebsiella pneumoniae. The resistance rate of A. baumannii was 71.5% to imipenem and 72.3% to meropenem. The resistance rate of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii to polymyxin B was only 0.5%. The results of the 2020 pediatric bacterial drug resistance surveillance by the ISPED (He et al., 2021) showed that the overall detection rate of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) was 33.5% (382/1140) and the overall resistance rate to multiple antibiotics was > 60%. In the face of such serious drug resistance, there are very limited therapeutic drugs available in the clinic, and polymyxins with specific antibacterial mechanisms have returned to the clinic with renewed attention (Infectious Diseases Committee of China Pharmaceutical Education Association et al., 2021). Polymyxin B (PMB) is often used as the last line of clinical defense in the treatment of extensively drug-resistant gram-negative bacillary infections (Lim et al., 2016).

The Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 IDSA/ATS Clinical Practice Guideline (Kalil et al., 2016) recommends that HAP/VAP caused by carbapenem-resistant bacteria be treated with intravenous infusion of polymyxins (colistin or polymyxin B) (strong recommended, moderate quality evidence) supplemented with inhaled colistin (weakly recommended, low quality evidence). In recent years, several additional national and international guidelines and expert consensus have recommended adjuvant polymyxin nebulization with intravenous polymyxin for patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) caused by suspected or confirmed multidrug- resistant (MDR) or extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacterial infections (Committee of Critical Care Medicine, China Society of Research Hospitals et al., 2019; Tsuji et al., 2019; Infectious Diseases Committee of China Pharmaceutical Education Association et al., 2021; Infectious Diseases Group of the Chinese Medical Association and Respiratory Diseases Branch, 2021). The recommended dosage and administration of polymyxin B sulfate nebulization is as follows: 250,000 to 500,000 U is dissolved in 5 ml of distilled water and nebulized with a conventional device, and a β2 agonist is inhaled 20 min before nebulization twice a day. The use of a vibrating mesh nebulizer is recommended.

Current studies on polymyxin B nebulization for the adjuvant treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections have mainly focused on adult patients. In the field of pediatrics, there are only a few clinical studies on the efficacy and safety of intravenous polymyxin B alone in the treatment of pneumonia in children with carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB), and there is a lack of data on the safety and efficacy of polymyxin B nebulization in pediatric patients. In addition to the guidelines and expert consensus, some studies have shown that nebulization of polymyxin B is effective and safe in pneumonia caused by infections due to resistant gram-negative bacilli for which intravenous administration is not effective (Pereira et al., 2007). Polymyxin B nebulization can reduce the course of respiratory-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacillus infections and has low nephrotoxicity (Abdellatif et al., 2016). The efficacy and safety of polymyxin B nebulization have also been reported negatively, and Demirdal et al. (2016) showed that the efficacy of polymyxin B nebulization in combination with intravenous administration for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia or ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by gram-negative bacilli infection did not differ statistically significantly from the efficacy of intravenous administration alone. A case of acute respiratory failure secondary to nebulization of polymyxin B in an asthmatic patient has been reported in the literature (Ma, 1982). In addition, the Expert Consensus on the Rational Use of Nebulization Therapy (2019 Edition) (Chinese Medical Association Clinical Pharmacy Branch, 2019) does not recommend intravenous preparations for nebulization because it may induce asthma or increase the risk of lung infection.

The child in this case had an underlying disease of spinal muscular atrophy, recurrent pulmonary infections requiring tracheal intubation, and invasive ventilator support, and the child also had long-term hospitalizations with a variety of advanced antibiotic therapies. The current pulmonary lesions were serious, and it was difficult to withdraw the ventilator. The child had an extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection, the drug susceptibility results showed colistin sensitivity, and the remaining isolates were resistant (including tigecycline). After the clinicians and pharmacists codeveloped the treatment regimen, the dosage and administration that were recommended were according to the 2021 Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus on the Rational Clinical Use of Polymyxin Antibacterial Drugs in China. At present, there is no nebulization formulation of polymyxin B in China. In this case, the administration route of polymyxin B was nebulization in addition to an intravenous drip, and the treatment process went smoothly.

In this case, during there were no other complications, such as nephrotoxicity, hepatic damage, neurotoxicity, or skin damage, except for a mild decrease in transcutaneous oxygen saturation and increased heart rate at the initial stage of nebulization. The overall treatment was safe and effective, and the shortcoming of this case report is that the blood concentration of polymyxin B could not be monitored. The success of treatment in this case will provide a data reference for the optimal application of polymyxin B in pediatric patients with pulmonary infections. Please note that, since we only had one case, we were unable to confirm the effect of nebulization in the case, although the overall effect was good. Whether nebulization has an ideal effect remains to be discussed further.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Children’s Hospital, Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing, China. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

BC reviewed the literature and analyzed the case. LC supervised the findings of this work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank clinical pharmacist Maowen Guo for treating our patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdellatif, S., Trifi, A., Daly, F., Mahjoub, K., Nasri, R., Lakhal, S. B. (2016). Efficacy and toxicity of aerosolised colistin in ventilator-associated pneumonia:a pro- spective,randomised trial. Ann. Intensive Care 6 (1), 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0127-7

Chen, B. Y., He, L. X., Hu, B. J. (2012). Expert consensus on the diagnosis, treatment and prevention and control of acinetobacter baumannii infection in China. Natl. Med. J. China 02, 76–85. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2012.02.002

Chinese Medical Association Clinical Pharmacy Branch. (2019). The Expert Consensus on the Rational Use of Nebulization Therapy (2019 Edition). Herald Med. 38 (2), 135–146. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1004-0781.2019.02.001

Committee of Critical Care Medicine, China Society of Research Hospitals, Committee of Evidence-based and Translational Infectious Diseases, China Society of Research Hospitals. (2019). Chinese expert consensus on the clinical application of polymyxin [J]. Chin. J. Emerg. Med. 28 (10), 1218–1222. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.10.007

Demirdal, T., Sari, U. S., Nemli, S. A. (2016). Is inhaled colistin benefi- cial in ventilator associated pneumonia or nosocomial pneumonia caused by acinetobacter baumannii? Ann. Clin. Micro Biol. Antimicrobials 15 (1), 1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0123-7

Ge, X., Bai, J., Lu, Y., Qu, Y., Song, F. (2012). The natural history of infant spinal muscular atrophy in China: a study of 237 patients. J. Child Neurol. 27 (4), 471–477. doi: 10.1177/0883073811420152

Guo, W., Cao, L. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 13 children with spinal muscular atrophy combined with pneumonia. Chin. J. Appl. Clin. Pediatr. 35 (21), 1629–1632. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn101070-20190715-00637

Guo, W., Chang, L., Cao, L. (2016). Diagnosis and treatment of respiratory diseases related to spinal muscular atrophy. Chin. J. Med. 51 (11), 10–14. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1070.2016.11.004

Hasan, M. J., Rabbani, R., Anam, A. M., Santini, A., Huq, S. M. R. (2021). The susceptibility of MDR-k. pneumoniae to polymyxin b plus its nebulised form versus polymyxin b alone in critically ill south Asian patients. J. Crit. Care Med. (Targu Mures) 7 (1), 28–36. doi: 10.2478/jccm-2020-0044

He, L., Fu, P., Wu, X., Wang, C., Yu, X., Xu, H., et al. (2021). Antimicrobial resistance profile of clinical strains isolated from children in China: a report from the ISPED program of 2020. Chin. J. Evidence Based Pediatr. 16 (06), 414–420. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2021.06.002

Hu, F., Guo, Y., Zhu, D., Wang, F., Jiang, X., Xu, Y., et al. (2021). CHINET surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among the bacterial isolates in 2021Chin J Infect Chemother 22 (5). doi: 10.16718/j.1009-7708.2022.05.001

Infectious Diseases Committee of China Pharmaceutical Education Association, Respiratory Diseases Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Critical Care Medicine Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Hematology Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Drug Clinical Evaluation Research Committee of Chinese Pharmaceutical Society, et al. (2021). Multi-disciplinary expert consensus on the optimal clinical use of the polymyxins in China. Chin. J. Tubercul. Respir. Dis. 44 (04), 292–310. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20201109-01091

Infectious Diseases Committee of China Pharmaceutical Education Association, Respiratory Diseases Branch of Chinese Medical Association. (2021). Topical application of antimicrobial agents for lower airway infection in adults: a Chinese expert consensus. Chin. J. Tubercul. Respir. Dis. 44 (4), 322–339. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200531-00656

Jia, X., Yin, Z., Zhang, W., Guo, C., Du, S., Zhang, X. (2022). Effectiveness and nephrotoxicity of intravenous polymyxin b in carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections among Chinese children. Front. Pharmacol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.902054

Kalil, A. C., Metersky, M. L., Klompas, M., Muscedere, J., Sweeney, D. A., Palmer, L. B., et al. (2016). Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America and the American thoracic society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63 (5), e61–e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353

Lim, T. P., Hee, D. K. H., Lee, W., Teo, J. C. M., Cai, Y., Chia, S. H. C., et al. (2016). Physicochemical stability study of polymyxin b in various infusion solutions for administra- tion to critically ill patients. Ann. Pharmacother. 50 (9), 790–792. doi: 10.1177/1060028016649598

Liu, X., Li, B., Hua, Y., Wu, K., Hu, M., Fan, T., et al. (2021). Polymyxin b for postoperative carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria-infected pneumonia in children with congenital heart disease. J. Chin. Pract. Diagnosis Ther. 35 (11), 1178–1181. doi: 10.13507/j.issn.1674-3474.2021.11.025

Ma, J. (1982). acute respiratory failure secondary to polymyxin b inhalation. J. Hebei Med. Coll. 3 (1), 39.

Mercuri, E., Finkel, R. S., Muntoni, F., Wirth, B., Montes, J., Main, M., et al. (2018). Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul. Disord. 28 (2), 103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.005

Peleg, A. Y., Seifert, H., Paterson, D. L. (2008). Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 (3), 538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07

Pereira, G. H., Muller, P. R., Levin, A. S. (2007). Salvage treatment of pneumonia and initial treatment of tracheobronchitis caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli with inhaled polymyxin b. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58 (2), 235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.008

Tsuji, B. T., Pogue, J. M., Zavascki, A. P., Paul, M., Daikos, G. L., Forrest, A., et al. (2019). International consensus guidelines for the optimal use of the polymyxins: endorsed by the American college of clinical pharmacy (ACCP), European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases (ESCMID), infectious diseases society of America (IDSA), international society for anti-infective pharmacology (ISAP), society of critical care medicine (SCCM), and society of infectious diseases pharmacists (SIDP). Pharmacotherapy 39 (1), 10–39. doi: 10.1002/phar.2209

Wu, G., Xing, Y., Zhang, M., Ma, S. (2022). Clinical analysis of polymyxins b in treatment of hospital acquired pneumonia with carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria in children. Drugs Clinic 37 (04), 876–881. doi: 10.7501/j.issn.1674-5515.2022.04.037

Zhou, L., Li, C., Weng, Q., Wu, J., Luo, H., Xue, Z., et al. (2021). Clinical study on intravenous combined with aerosol inhalation of polymyxin b for the treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. China Crit. Care Med. 33 (04), 416–420. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20201215-00753

Keywords: polymyxin B, Acinetobacter baumannii, extensively drug-resistant, pneumonia, spinal muscular atrophy

Citation: Cao B and Cao L (2023) Case Report: A case of spinal muscular atrophy with extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia treated with nebulization combined with intravenous polymyxin B: experience and a literature review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13:1163341. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1163341

Received: 10 February 2023; Accepted: 26 May 2023;

Published: 21 June 2023.

Edited by:

Yonghong Yang, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tengfei Song, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, United StatesJiaosheng Zhang, Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, China

Copyright © 2023 Cao and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ling Cao, Y2FvbGluZzk5MTlAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Bingqing Cao

Bingqing Cao Ling Cao

Ling Cao