94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 25 August 2022

Sec. Fungal Pathogenesis

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.923700

This article is part of the Research TopicFungal diagnostics: culture, molecular, mass spectrometryView all 6 articles

Phytophthora cinnamomi causes crown and root wilting in more than 5,000 plant species and represents a significant threat to the health of natural ecosystems and horticultural crops. The early and accurate detection of P. cinnamomi is a fundamental step in disease prevention and appropriate management. In this study, based on public genomic sequence data and bioinformatic analysis of several Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium species, we have identified a new target gene, Pcinn13739; this allowed us to establish a recombinase polymerase amplification–lateral flow dipstick (RPA-LFD) assay for the detection of P. cinnamomi. Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD assay was highly specific to P. cinnamomi. Test results for 12 isolates of P. cinnamomi were positive, but negative for 50 isolates of 25 kinds of Phytophthora species, 13 isolates of 10 kinds of Phytopythium and Pythium species, 32 isolates of 26 kinds of fungi species, and 11 isolates of two kinds of Bursaphelenchus species. By detecting as little as 10 pg.µl−1 of genomic DNA from P. cinnamomi in a 50-µl reaction, the RPA-LFD assay was 100 times more sensitive than conventional PCR assays. By using RPA-LFD assay, P. cinnamomi was also detected on artificially inoculated fruit from Malus pumila, the leaves of Rhododendron pulchrum, the roots of sterile Lupinus polyphyllus, and the artificially inoculated soil. Results in this study indicated that this sensitive, specific, and rapid RPA-LFD assay has potentially significant applications to diagnosing P. cinnamomi, especially under time- and resource-limited conditions.

Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands is a genus in the Oomycetes, a Class in Phylum Pseudofungi within the Kingdom Chromista (Beakes et al., 2012). Oomycetes are a class of ubiquitous, filamentous microorganisms that include some of the biggest threats to global food security and natural ecosystems. P. cinnamomi has been ranked in the Top oomycete plant pathogens based on scientific and economic importance, which can infect more than 5,000 species of plants (Kamoun et al., 2015; Hardham and Blackman, 2018). This pathogen has caused significant economic losses in the agricultural, forestry, and horticultural activities of more than 76 countries. P. cinnamomi had catastrophic consequences on natural ecosystems and biodiversity (Rands, 1922; Zentmyer, 1980; Erwin and Ribeiro, 1996). As a soil-borne pathogen, P. cinnamomi can produce thick-walled oospores in host roots and soil (McCarren et al., 2005). This characteristic allows the pathogen to survive without causing obvious damage to the plants during the initial stages of infection, thus making this pathogen very difficult to manage (Dunstan et al., 2010). An increase in drought stress cycles has led to an exacerbation in the pathogenic effect of P. cinnamomi (Corcobado et al., 2014; Umami et al., 2021). Therefore, P. cinnamomi has become known as a “biological bulldozer” that represented a significant threat to plant species in temperate regions (Engelbrecht et al., 2021). With regards to the morphological comparison of Phytophthora with Phytopythium and Pythium, which also belong to oomycete, it has been established that the papillate sporangium of Phytophthora never shows internal proliferation. The combination of internal proliferation and papillation was unique to the sporangia of Phytopythium and some Pythium species. Pythium species have very large sporangia with a tapering neck rather than distinct papillae (De Cock et al., 2015). Previous research established maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees based on nuclear ribosomal DNA (LSU and SSU) and mitochondrial DNA cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COX I), thus confirming that Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium belong to three distinct branches (De Cock et al., 2015).

Accurate and rapid detection played a fundamental role in the management of P. cinnamomi. Traditional assays for detecting P. cinnamomi included the isolation of samples from symptomatic plant tissues and baiting from soil (Erwin and Ribeiro, 1996). However, these methods required basic knowledge of cultural techniques and ideal laboratory conditions and involve long incubation and growth times. With the advent of molecular technology, several molecular assays have been designed to detect P. cinnamomi, namely, conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Kong et al., 2003), nested PCR (Williams et al., 2009), quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Eshraghi et al., 2011), Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) (Dai et al., 2019), and recombinase polymerase amplification–lateral flow dipstick (RPA-LFD) (Dai et al., 2020).

The choice of the target for molecular detection was the first and most important step in the management of P. cinnamomi. Initially, Kong et al. (2003) designed specific PCR primers for detection based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Williams et al. (2009) used nested multiplex PCR primers based on ITS to detect P. cinnamomi in the southwestern corner of Australia. Eshraghi et al. (2011) established a qPCR assay for detecting P. cinnamomi based on phosphate dikinase (PDK) gene. More recently, faster and easier isothermal assays have been developed, namely, LAMP (Notomi et al., 2000) and RPA. Dai et al. (2019) used whole genome sequencing to identify a new target gene in P. cinnamomi and then used the gene to develop a LAMP assay. The open reading frame (ORF) identification process used in this assay involved bioinformatics-based screening of all putative P. cinnamomi ORFs against eight Phytopthora databases (P. capsica, P. infestans, P. nicotianae, P. ramorum, P. sojae, P. asiatica (= P. cinnamomi var. robiniae), P. parvispora (= P. cinnamomi var. parvispora), and P. vignae. These species are closely related to P. cinnamomi. By combining sequence information from these species with those that were commonly encountered in the forestry environment, it will be helpful to search for target genes that are unique for P. cinnamomi. These genes will represent excellent candidates for application in rapid, field-based diagnostic assays that will be specific to P. cinnamomi.

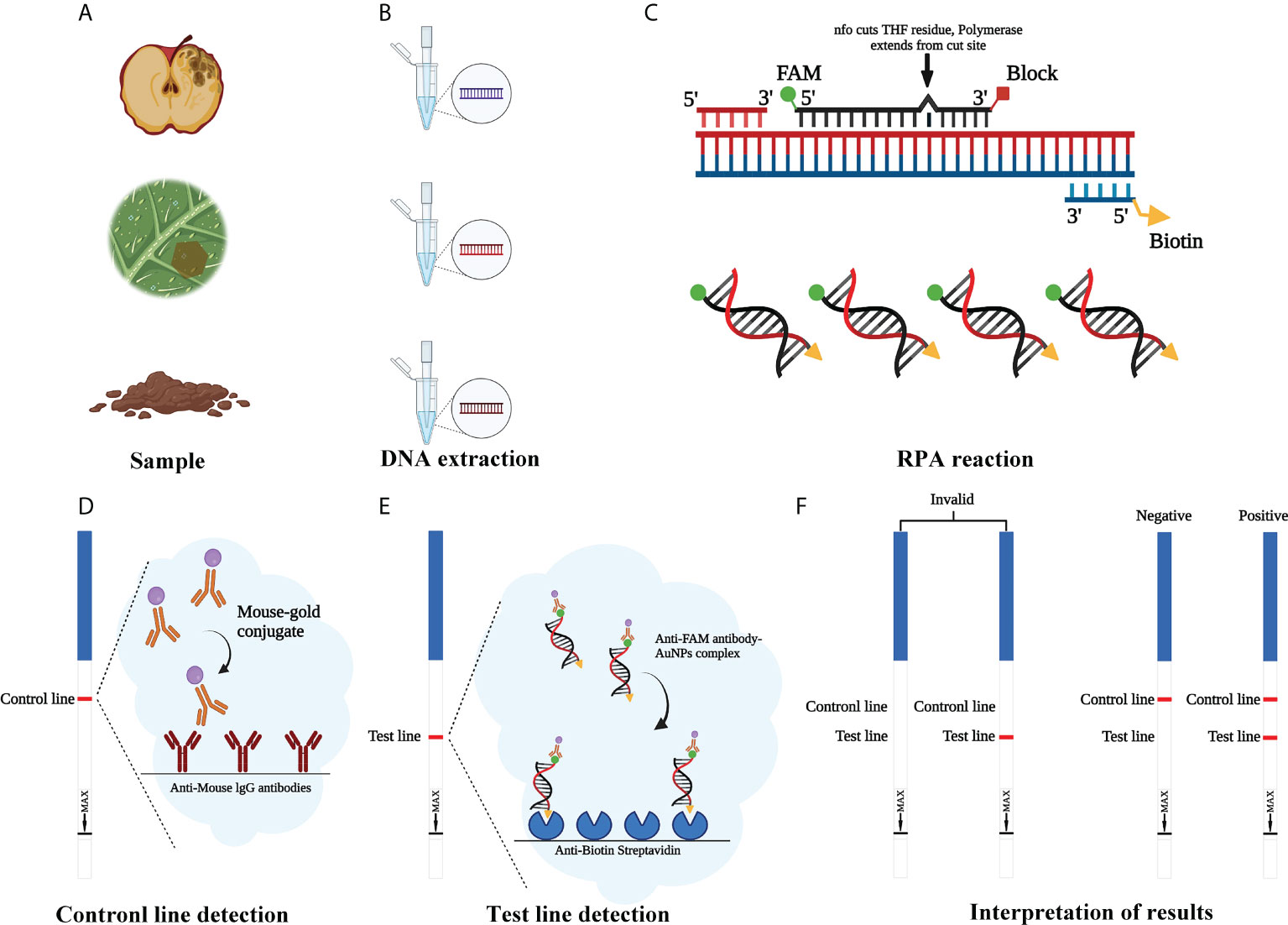

Unlike the conventional PCR that requires denaturation, annealing, and extension and requires gel electrophoresis for imaging, RPA only requires 20 min of isothermal amplification at 37°C and 5 min of LFD to complete the visualization and detection (Daher et al., 2016). The RPA-LFD assays require a pair of forward primer and a 5′-biotin-labeled reverse primer and a special nfo probe with a fluorescein amidites (FAM) (carboxyfluorescein) antigen label at the 5′-end, a C3 spacer (amplification blocker) at the 3′-end, a tetrahydrofuran (THF) spacer (abasic site) in the middle. When the THF site pair and the template could match, the nfo enzyme was activated, the THF was cleaved, and the C3 spacer was excised from the probe. Thus, RPA contained both FAM and biotin, and the mouse anti-FAM antibody was enveloped with AuNPs. After diluted reaction products were added to the sample well, they were moved across the conjugate pad and binded to the anti-FAM AuNPs. The test line, which was enveloped with streptavidin, captures molecules with a biotin label when the amplification products went through. The control line, which was used to validate LFD detection, captured the anti-FAM antibody enveloped with AuNPs, because the anti-FAM antibody is from a mouse (Dai et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2022).

In this study, public genomic sequence data and bioinformatic analysis of several Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium species were utilized for identifying the unique ORFs present in P. cinnamomi. These analyses identified a total of more than 1,000 specific target genes as the candidate genes for P. cinnamomi. Specific primers and probes were designed to amplify the novel target gene Pcinn13739. The specificity of the developed assay was evaluated by testing 50 isolates of Phytophthora species, six isolates of Phytopythium species, seven isolates of Pythium species, 32 isolates of fungal species, and 11 isolates of Bursaphelenchus species. Moreover, the sensitivity of the Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD assay was compared to a conventional PCR-based method.

The isolates of Phytophthora, Phytopythium, Pythium, Bursaphelenchus, and fungi used in this study were isolated from different host plants and regions (Table 1). Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium were cultured on 10% clarified V8 juice agar (cV8A). Isolates of fungi were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 25°C in the dark for 3–5 days. B. xylophilus and B.mucronatus were propagated using the mycelia of Botrytis xylophilus for one generation at 25°C for 4–5 days (Mamiya, 1975). The isolates used in this study are preserved in the Department of Forest Protection at Nanjing Forestry University in Nanjing, China. We used a DNAsecure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) to extract genomic DNA (gDNA) from all isolates. Extracted gDNAs were then quantified using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and diluted accordingly. All DNA samples were stored at -20°C until use.

The annotated genomic sequence of P. cinnamomi at the website (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/Phyci1/Phyci1.home.html) was retrieved. Bioinformatics technology has developed significantly over recent years and, thus, a greater number of whole genome sequences were available for Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium, along with other fungal species that caused soil-borne disease. All 26,131 gene sequences of P. cinnamomi were used as queries to perform BLAST searches against the genomic sequences of 35 Phytophthora species derived from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (E-value cutoff: 1 × 105) (Supplementary Table 1). A total of more than 1,000 P. cinnamomi genes did not share any sequence similarity with any other species of Phytophthora and were used as queries to blast against the NCBI nucletotide database to further exclude genes showing similarity with the other nine Pythium species, five Fusarium species, and Phytopythium vexans. Ten genes (Pcinn13739, Pcinn1025, Pcinn16994, Pcinn18321, Pcinn10079, Pcinn137495, Pcinn14424, Pcinn11754, Pcinn1601, and Pcinn17552) were randomly selected as specific targets to P. cinnamomi for further conventional PCR primer design (Supplementary Table 2). PCR method was used to verify the specificity of these 10 target genes. These genes also did BLAST through the website (https://fungidb.org/fungidb/app/search/transcript/UnifiedBlast) to make sure its specificity and then used MEGA 7.0.20 to establish phylogenetic relationships. Then, we synthesized RPA primers and probes directly with a GenDx ERA Kit (GenDx Biotech, Suzhou, China) based on the specific gene in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines (Supplementary Figure S1). All primers and probes were synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China).

Conventional PCR amplifications were performed in 50-µl reactions. Each reaction included 25 µl of Primer STAR Max Premix (2 × Takara), 21 µl of nuclease-free H2O, 2 µl of purified gDNA (100 ng), and 1 µl of each forward and reverse primer (10 µM). Thermal cycling began at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 33 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; this was followed by 10 min at 72°C for 10 min. PCR was performed on Applied Biosystems Veriti Dx 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Each set of reactions included a non-template control (NTC) to eliminate false positives. Following amplification, PCR products were detected on a 1.5% agarose gel, separated by electrophoresis at 130 V for approximately 25 min, and then visualized with a UV transilluminator. For nested PCR assays, we initially amplified the target gene of P. cinnamomi using specific primers (Pcinn13739-nest-F and Pcinn13739-nest-R). The thermal cycling program was the same as for conventional PCR (Table 1). For the second round of amplification, the PCR products arose from the first round, and then we added 2 μl of PCR products to each reaction and performed amplifications with Pcinn13739-F and Pcinn13739-R. All PCR and nested PCR reactions were repeated at least three times.

RPA assays were performed with a GenDx ERA kit (GenDx Biotech, Suzhou, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Then, 5 µl of amplification product was diluted 60-fold with nuclease-free H2O. LFD was inserted into a centrifuge tube containing the diluted reaction products for 7–10 min to allow analysis of the assay results. When a red band appeared on both the control line (upper line) and test line (lower line) of the LFD, the result was considered to be positive. If it appears only on the control line and not on the test line, the LFD result was negative. Also, if it appears not on the control line, the LFD result was invalid (Figure 1). Tests were repeated at least three times. After visualization, LFDs were photographed using an EOS-750D camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1 Schematic illustration of the RPA-LFD assay used to detect Phytophthora cinnamomi. (A) Collect the samples. (B) Genomic DNA (gDNA) is extracted from samples using the NaOH method. (C) Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). (D) Mouse antibody-gold conjugate binds to immobilized anti-mouse IgG antibodies. (E) The sample enters testing line and anti-FAM antibody-AuNPs complex binds to immobilized anti-biotin streptavidin. (F) Invalid result: no visible dipstick in control line despite the test line. Positive result: one visible dipstick each in control line and test line. Negative result: one visible dipstick in control line. Created with https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates.

The specificity of RPA-LFD system was evaluated with gDNA of 50 isolates of 25 kinds of Phytophthora species, 13 isolates of 10 kinds of Phytopythium and Pythium species, 32 isolates of 26 kinds of fungi (Table 1). A purified isolate of gDNA (100 ng) was used as a template for both assays. A positive control (P. cinnamomi isolate 23B1, 100 ng as a template) and a control (NTC, ddH2O as a template) were included in each set of reactions. All template concentrations were evaluated twice in each assay.

In a comparative evaluation of assay sensitivity, nine serial dilutions of gDNA from P. cinnamomi (100 ng, 10 ng, 1 ng, 100 pg, 10 pg, 1 pg, 100 fg, 10 fg, and 1 fg) were used in 50-µl reactions as templates for conventional PCR, nested PCR, and RPA-LFD assays. Each set of reactions included an NTC (ddH2O as template). All template concentrations were evaluated twice in each assay.

The use of conventional PCR and RPA-LFD assays to detect P. cinnamomi in artificially inoculated fruit from Malus pumila “FuJi,” the leaves of Rhododendron pulchrum Sweet, and the roots of sterile Lupinus polyphyllus Lindl

Prior to inoculation, the fruit of M. pumila “FuJi” and the leaves from R. pulchrum were washed with distilled water, immersed in 70% ethanol for 10 s, and then washed with sterilized distilled water. The fruit of M. pumila “FuJi” was then punctured with a sterile inoculation needle (to a depth of approximately 1 cm). The leaves of R. pulchrum were punctured with a sterile inoculation needle. A 5-day-old cV8A plug (5 × 5 mm) containing mycelium colonized by P. cinnamomi was then placed into the wound sites on six replicate fruits and leaves. Inoculated on the leaves of R. pulchrum using the mycelium with other species such as Phytopythium litorale, Ph. helicoides, and Phytophthora pini were also as controls. Non-inoculated control samples were treated with sterile cV8A plugs as negative controls. All samples were then moisturized and stored in a dark incubator at a temperature of 25°C. Three days later, gDNAs were extracted from decayed sections infested with P. cinnamomi using the NaOH method (Wang et al., 1993). The gDNA extractions were used as detection templates for conventional PCR and RPA-LFD. This experiment was carried out twice. Purified gDNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as the template in positive control reactions and each set of reactions included NTC.

Seeds from Lupinus polyphyllus were first soaked in sterile water for 2 h, drained on filter paper, soaked in 70% ethanol for 30 s, rinsed three times in sterile water, soaked in 30% H2O2 for 10 min, rinsed four to five times in sterile water, and finally drained on sterile gauze for subsequent use. Sterile seeds were placed in Woody Plant Medium (WPM) (McCown and Loyd, 1981), with five seeds placed on each tray on the center line, covered in each WPM medium, sealed with a film cover, and then incubated in an incubator (temperature: 26°C; daylight: 16 h) for 5 days. When the seeds had grown to a root size of 1–2 cm, we selected healthy sterile seedlings for inoculation with P. cinnamomi. Then, we used the NaOH method (Wang et al., 1993) to extract gDNA from the decayed sections infested with P. cinnamomi and used the gDNA as amplification templates for conventional PCR and RPA-LFD. This experiment was carried out twice. Purified gDNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as a template in positive control reactions. Each set of reactions included an NTC.

Ten agar plugs (2 × 2 mm2) of each P. cinnamomi isolate were transferred into 10 ml of 10% V8 juice to produce mycelial mats. After 3 days, the V8 was replaced with sterile water. To stimulate sporangial and zoospore production, three to five drops of soil extract solution (soil collected from healthy fields, immersed in sterile water, and filtered) were added to each plate. Then, 100 g of dried, sterile, and organic soil was inoculated with 50 ml of zoospore suspension (106 zoospore/ml); then, 1-year-old R. pulchrum seedlings were planted in the soil. A portion of non-inoculated sterilized soil was used as a negative control. Ten days later, 100 mg of inoculated and non-inoculated soil was collected, and DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. ® Soil DNA Kit (Omega BIO TEK, Norcross, GA, USA). DNA templates were then used for RPA-LFD detection. This experiment was repeated three times.

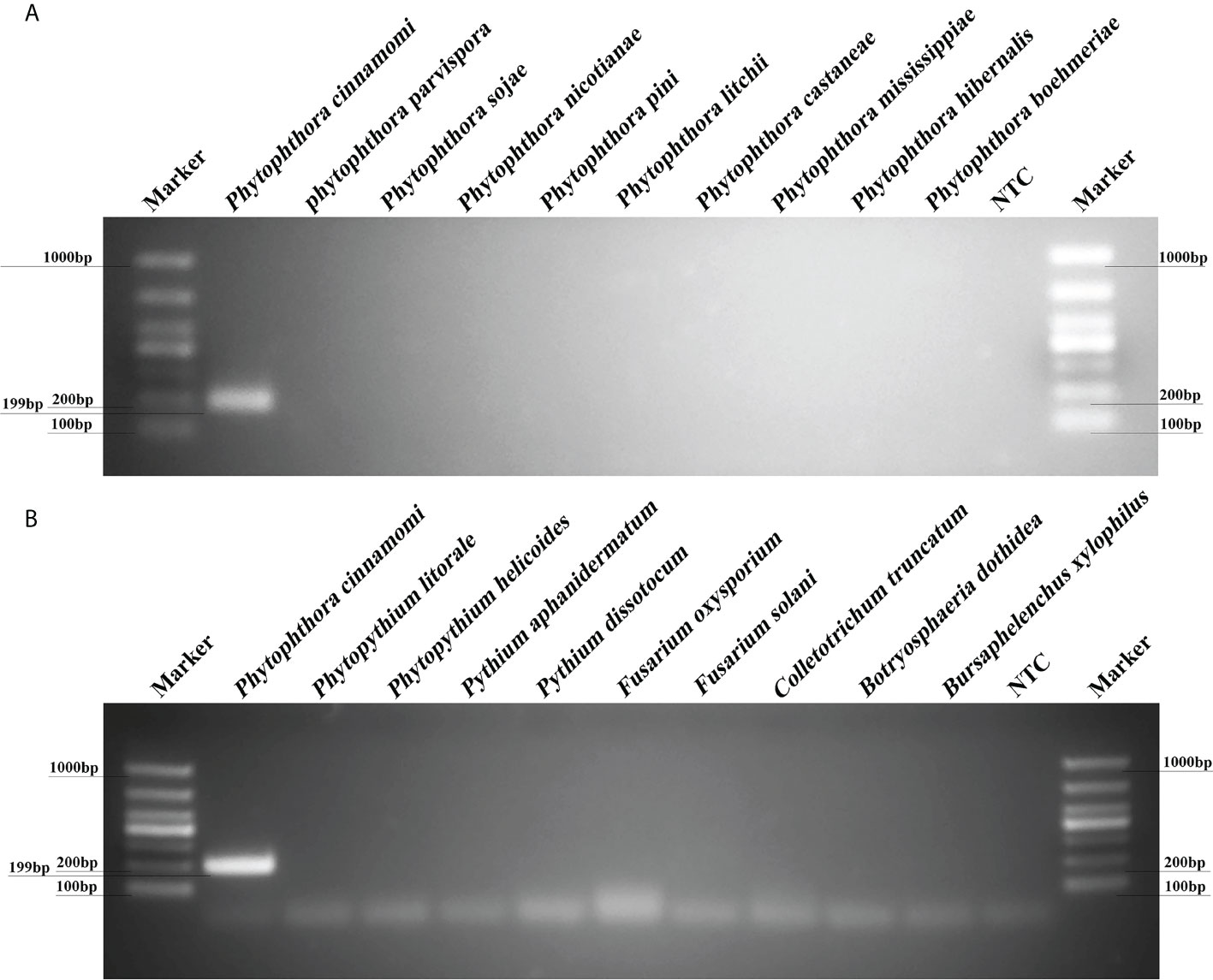

PCR reactions containing gDNAs from 12 isolates of P. cinnamomi isolates and 106 isolates of other Phytophthora species collected from different regions were used to test reaction specificity based on 10 target sequences. The Pcinn13739-PCR primers were designed to amplify specific target genes and were found to specific for P. cinnamomi (Supplementary Table 2). PCR amplicons that were approximately 199 bp in size were detected in PCR reactions containing gDNAs from P. cinnamomi isolates (Figure 2). No PCR amplicons were observed in reactions involving the isolates of 50 other Phytophthora species, six Phytopythium species, seven Pythium species, 32 fungal species, and 11 Bursaphelenchus species, including the closely related genera P. asiatica (= P. cinnamomi var. robiniae), P. parvispora (= P. cinnamomi var. parvispora), and P. vignae; similarly, no PCR amplicons were produced in the NTCs. In contrast, other primers, namely, Pcinn16994-F and Pcinn16994-R (based on Pcinn16994), Pcinn18321-F and Pcinn18321-R (based on Pcinn18321), Pcinn10079-F and Pcinn10079-R (based on Pcinn10079), Pcinn1025-F and Pcinn1025-R (based on Pcinn1025), Pcinn11754-F and Pcinn11754-R (based on Pcinn11754), Pcinn1601-F and Pcinn1601-R (based on Pcinn1601), Pcinn137495-F and Pcinn137495-R (based on Pcinn137495), Pcinn14424-F and Pcinn14424-R (based on Pcinn14424), and Pcinn17552-F and Pcinn17552-R (based on Pcinn17552) were used to test all experimental isolates. Other nine targets were not specific to P. cinnamomi (Supplementary Figures S2-S6). Phylogenetic relationships displayed that Pcinn13739 was also a specific gene (Supplementary Figure S7). PCR amplicons were produced for the remaining nine genes, except for Pcinn13739, in reactions containing the gDNAs from other fungal or oomycete species, thus indicating that there was a lack of specificity for detecting P. cinnamomi DNA.

Figure 2 A new target gene (Pcinn13739) was found to be specific for the detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi. (A) Evaluation of specificity for a PCR assay based on a novel target (Pcinn13739) in Phytophthora species. Amplicons that were approximately 199 bp in size were detected by PCR in reactions containing gDNA from P. cinnamomi isolates. No PCR amplicons were observed for other Phytophthora species. (B) A 199 bp band was detected in P. cinnamomi but not in other Phytopythium, Pythium, fungi, Bursaphelenchus; similarly, no bands were detected in the negative controls NTC, negative control; Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Each group of experiments was repeated in triplicate.

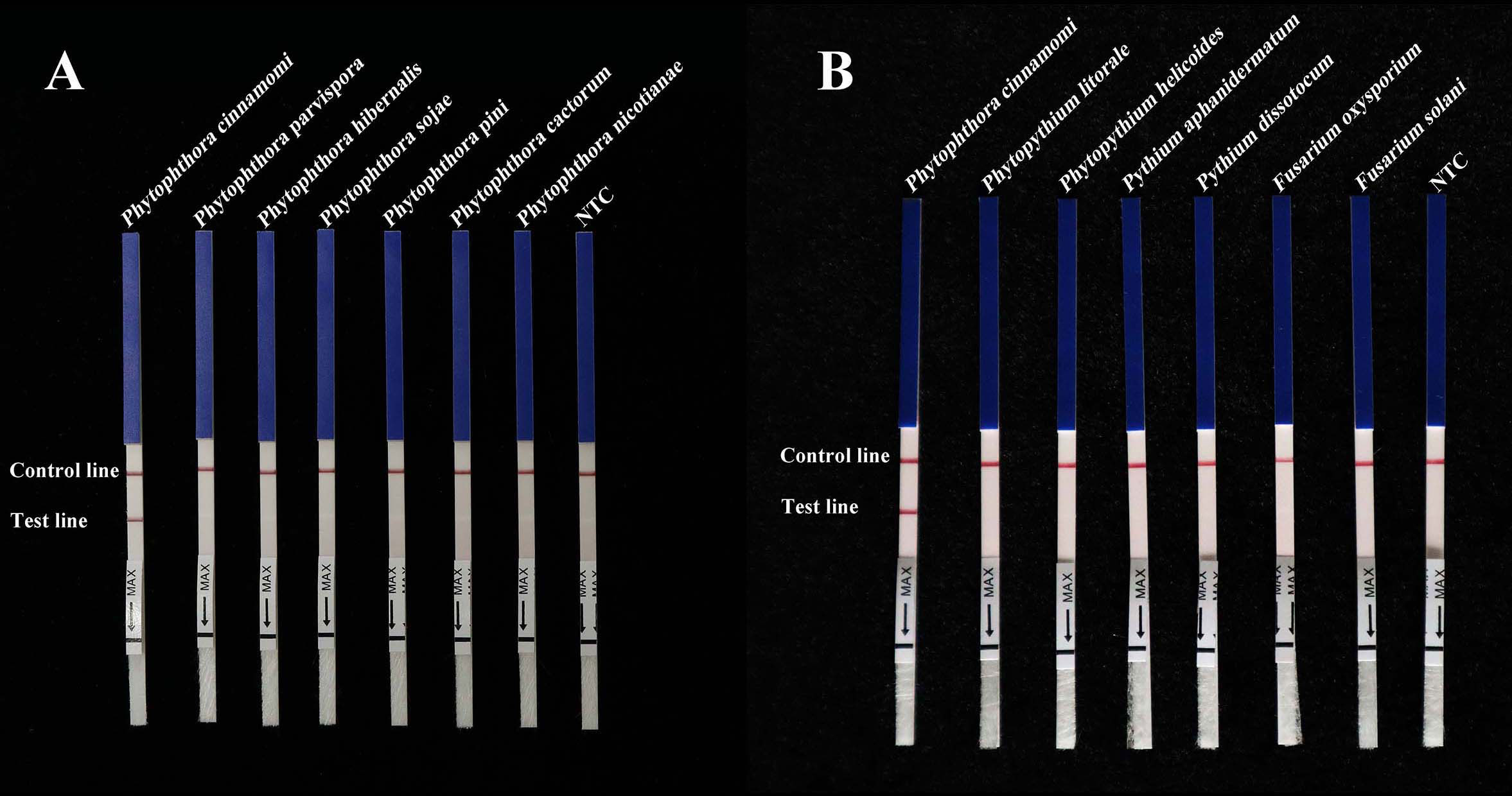

A specific pair of primers (Pcinn13739-RPA-F and Pcinn13739-RPA-R) was designed to exclusively and consistently amplify P. cinnamomi isolates by RPA-LFD assays (Table 1). The 5′-end of the reverse primer was labeled with biotin. A Pcinn13739-probe was also designed in accordance with the instructions provided with the GenDx ERA Kit (GenDx Biotech, Suzhou, China). In the RPA-LFD assay, the specificity of Pcinn13739-RPA-F and Pcinn13739-RPA-R was verified using a variety of different species (50 isolates of Phytophthora spp., 13 isolates of Phytopythium and Pythium spp., 32 isolates of fungi, and 11 isolates of Bursaphelenchus spp. All dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating that the tests were valid. No test lines were detected in gDNAs (100 ng) from other species (Phytophthora, Phytopythium, Pythium, fungi, and Bursaphelenchus) or NTCs (Figure 3). Consistent results were obtained for the RPA-LFD assay in three biological replicates.

Figure 3 RPA-LFD assays were used to specifically detect P. cinnamomi. (A) All dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating validation tests. No test lines were detected in those featuring gDNA (100 ng) from other Phytophthora species or in NTCs. (B) Using the RPA-LFD assay, all dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating valid tests. No test line was detected for the gDNA (100 ng) of Phytopythium species, Pythium species, fungal species, Bursaphelenchus species, or in the NTCs. NTC, negative control. Experiments were repeated three times; all replicates showed the same results.

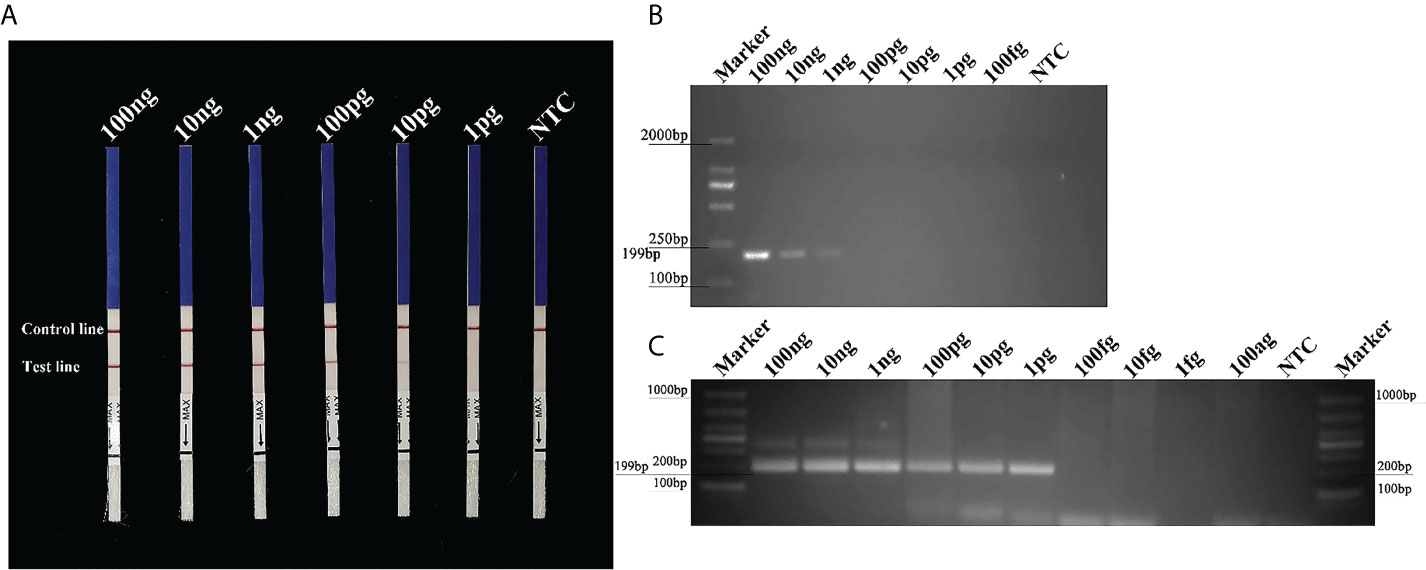

The Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD assays were 100-fold more sensitive than the conventional PCR assay for the detection of gDNA from P. cinnamomi. Sensitivity evaluation showed that RPA- LFDs had a visible control line. Test lines were visible on LFDs from RPA reactions (50 µl) containing at least 0.01 ng (10 pg) of P. cinnamomi gDNA (Figure 4A). No test lines were observed on those containing 1 pg of gDNA or the NTCs (Figure 4A). These results were consistent across three experimental replications. In the PCR assay, approximately 199-bp-long PCR amplicons were detected in reactions containing gDNA of P. cinnamomi isolates; no PCR amplicons were detected in reactions containing a concentration of DNA template that was 0.1 ng or lower (Figure 4B). The nested PCR assay detected 1 pg of P. cinnamomi gDNA and yielded positive detection results (Figure 4C). The sensitivity of nested PCR (1 pg) assay for the detection of P. cinnamomi was 10-fold higher than that of RPA-LFD (10 pg) and 1,000-fold higher than conventional PCR (1 ng). However, the time required for RPA-LFD (0.5 h) was only one-sixth of that required for nested PCR (3 h) and one-third of that for conventional PCR (1.5 h).

Figure 4 Sensitivity of the Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD, conventional PCR and nested PCR assays for P. cinnamomi. (A) All dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating that the test was valid. Test lines were visible on LFDs of RPA reactions (50 µl) containing at least 0.01 ng (10 pg) of P. cinnamomi gDNA. (B) In the conventional PCR assay, the detection threshold was 1 ng. No PCR amplicons were detected in reactions containing DNA template at 0.1 ng or lower. NTC, negative control. Marker DL2000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). (C) Nested PCR assay could detect 1 pg gDNA of P. cinnamomi, yielding positive detection results. NTC, negative control. Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Experiments were repeated three times; all replicates showed the same results.

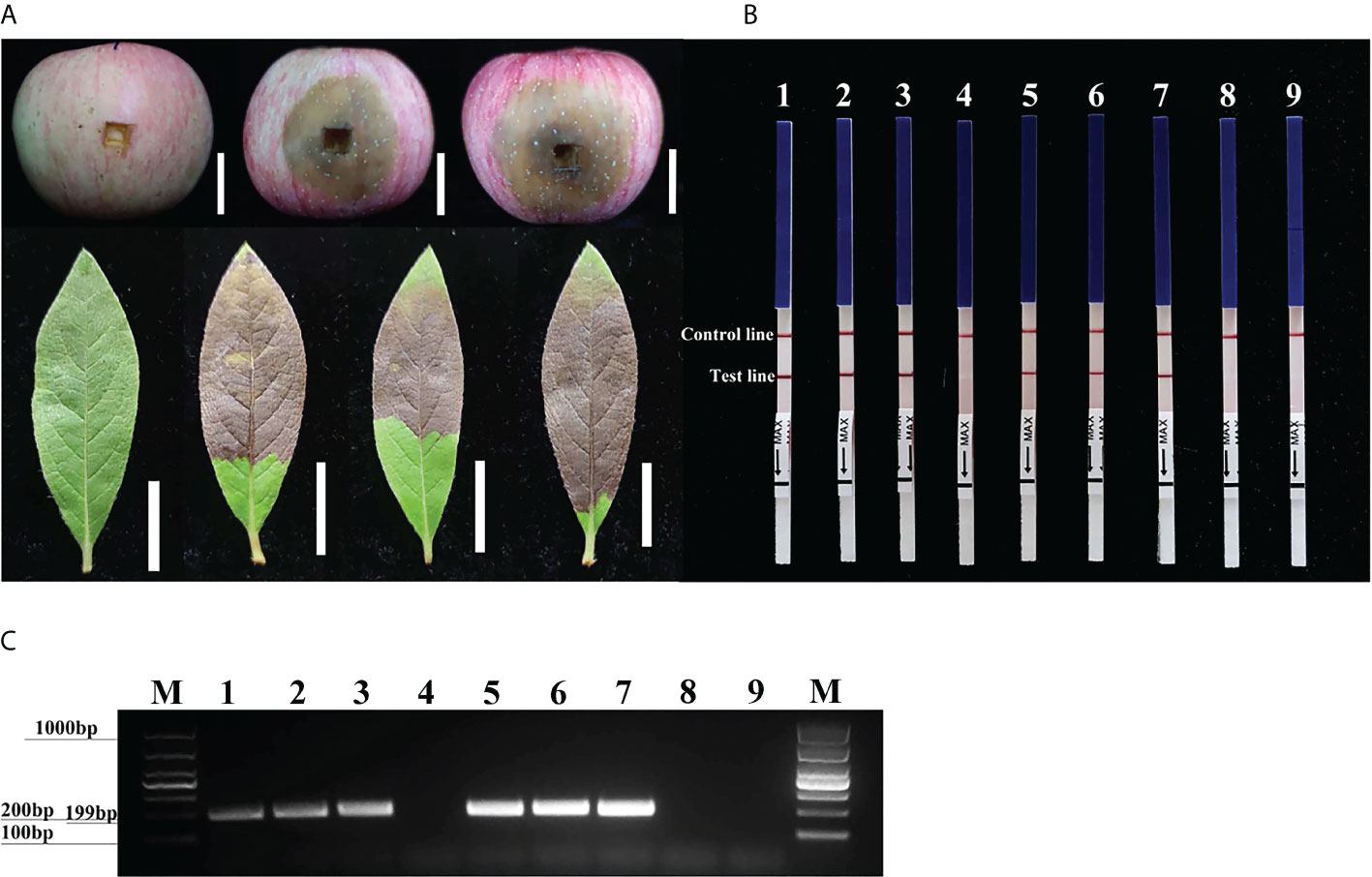

Three days after inoculation with mycelium of P. cinnamomi, we observed typical symptoms at the inoculation sites on the fruit of M. pumila “FuJi” and the leaves of R. pulchrum; however, no such symptoms were evident on the non-inoculated negative controls (Figure 5A). gDNAs were extracted from the fruit of M. pumila “FuJi” and the leaves of R. pulchrum inoculated with P. cinnamomi to act as templates for assays. Red bands were evident on both the control and test lines of the LFDs, indicating positive test results. Correspondingly, two symptomatic fruits (1–2) and three symptomatic leaves (4–6) had positive results in the RPA-LFD assay, whereas the asymptomatic ones (3 and 7) and the NTCs (ddH2O as template) had negative results (Figure 5B). P. cinnamomi was recovered from symptomatic fruits but not from asymptomatic ones or the negative control. The conventional PCR assay also detected P. cinnamomi in the artificially inoculated samples (Figure 5C). PCR amplicons that were approximately 199 bp in size were detected in PCR reactions containing gDNAs from inoculated samples (1–2, 4–6), whereas no PCR amplicons were showed in the asymptomatic ones (3 and 7) and the NTCs (ddH2O as template). Each set of experiments was repeated three times, and the same results were obtained each time.

Figure 5 Detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi in artificially inoculated fruit from Malus pumila “FuJi” Mill. and the leaves of Rhododendron pulchrum Sweet using Pcinn13739 RPA-LFD and conventional PCR assays. (A) 1–2, artificially inoculated M. pumila “FuJi.” 3, a healthy apple as a negative control. 4–6, artificially inoculated R. pulchrum leaves. 7, a healthy leave as a negative control. The white scale bar represents 2cm. (B) The detection of artificially inoculated samples by the RPA-LFD assay. 1–2, artificially inoculated M. pumila “FuJi.” 3, a non-inoculated apple as a negative control. 4–6, artificially inoculated R. pulchrum leaves. 7, non-inoculated leave as a negative control. NTC, ddH2O as template. Genomic DNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as a template in positive control (PTC). All dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating valid tests. (C) Detection of gDNA extracted from artificially inoculated samples by conventional PCR assay. 1–2, artificially inoculated M. pumila “FuJi.” 3, non-inoculated apple as a negative control. 4–6, artificially inoculated R. pulchrum leaves. 7, non-inoculated leave as a negative control. Negative control (NTC), ddH2O as template. M, Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Genomic DNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as a template in positive control (PTC). Each set of experiments was repeated in triplicate with the same results.

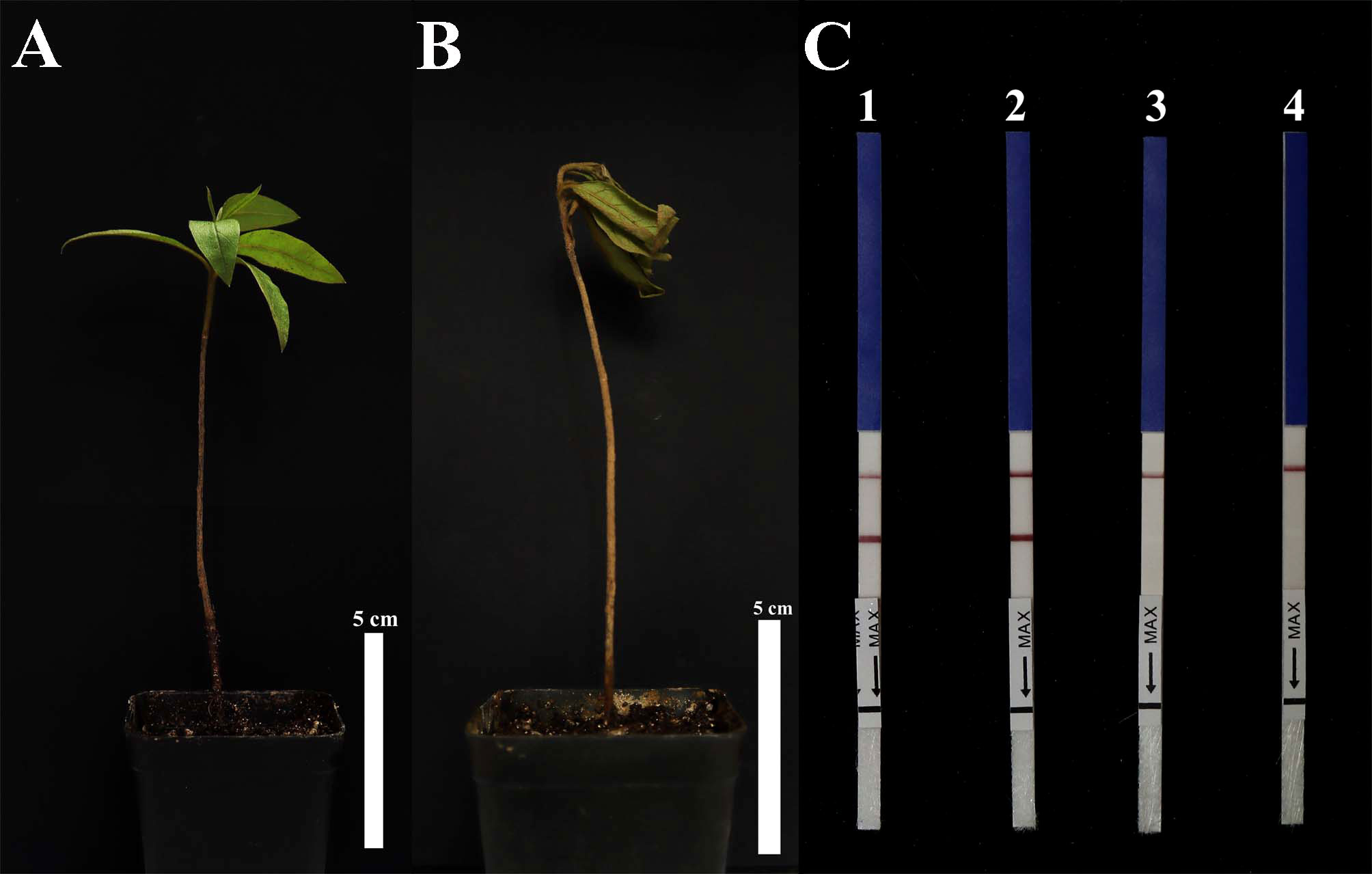

Typical symptoms of brown rot were observed in all roots of artificially inoculated L. polyphyllus samples (1–3) but not in the non-inoculated control L. polyphylla (4) (Figure 6A). In the Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD assay, all dipsticks had visible control lines. Test lines were visible on three dipsticks with total DNAs extracted from inoculated roots, whereas no test lines were observed on those from non-inoculated root and NTC (Figure 6B). PCR amplicons that were approximately 199 bp in size were detected in PCR reactions containing gDNAs from inoculated roots (1–3), whereas no PCR amplicons were showed in the asymptomatic one (4) and the NTC (ddH2O as template) (Figure 6C). Each group of experiments were repeated three times.

Figure 6 Detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi in the artificially inoculated roots of sterile Lupinus polyphyllus Lindl. using Pcinn13739 RPA-LFD and conventional PCR assays. (A) 1–3, roots of artificially inoculated sterile L. polyphyllus. 4, non-inoculated as a control. The white scale bar represents 1 cm. (B) Detection of artificially inoculated samples by the RPA-LFD assay. 1–3, roots of artificially inoculated sterile L. polyphyllus. 4, non-inoculated as a control. Genomic DNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as a template in positive control (PTC), negative control (NTC). All dipsticks yielded visible control lines, indicating valid tests. (C) Detection of artificially inoculated samples by conventional PCR assay. 1–3, roots of artificially inoculated sterile L. polyphyllus. 4, non-inoculated as a control. M, Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Genomic DNA (100 ng) of P. cinnamomi was used as a template in positive control (PTC), negative control (NTC). Each group of experiments was repeated in triplicate and yielded similar results.

Ten days after planting in soil containing zoospore suspension, R. pulchrum seedlings had developed disease symptoms, whereas the controls had no symptom (Figures 7A, B). In total, 100 mg of inoculated and non-inoculated soil was collected, and DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. ® Soil DNA Kit. Then, we used the DNA as templates for RPA-LFD detection. gDNA (100 ng µl-1) purified from P. cinnamomi isolates was used as a positive control, whereas ddH2O was used as an NTC. In the RPA-LFD assay, all dipsticks showed a visible control line. Test lines were also visible on dipsticks containing DNA extracted from artificially P. cinnamomi–inoculated soils and the positive control, However, no test lines were observed from non-inoculated soil or the NTC (Figure 7C). Identical results were obtained from three repeats of this experiment.

Figure 7 Detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi in artificially inoculated soil. (A) R. pulchrum was grown in non-inoculated soil for 10 days. (B) R. pulchrum was grown in artificially inoculated soil for 10 days. (C) Detection of artificially inoculated soil by RPA-LFD assay. 1, positive control. 2, artificially inoculated soil. 3, non-inoculated soil. 4, negative control. Data is representative of three replicate experiments.

P. cinnamomi has led to significant declines of the agricultural livestock ecosystem in the Iberian Peninsula (Rodriguez-Romero et al., 2021) and the production of highbush blueberry in Germany (Nechwatal and Jung, 2021) and also led to root and stem rot in Vaccinium corymbosum L. (Lan et al., 2016a) and Castanea mollissima (Chinese Chestnut) (Lan et al., 2016b). In addition, P. cinnamomi has had severe impacts on kiwifruit production in China (Bi et al., 2019) and has seriously affected the growth and yield of Carya cathayensis in Linan County, China (Tong et al., 2022). Due to the serious economic implications associated with P. cinnamomi, it was vital to develop a reliable and accurate diagnostic tool. To implement timely disease management and avoid unnecessary costs due to misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis, accurate detection of P. cinnamomi was a prerequisite for effective management and successful elimination of pathogens. However, molecular detection methods, such as conventional PCR (Kong et al., 2003), nested PCR (Williams et al., 2009), and LAMP (Dai et al., 2019), were time-consuming and require personnel with professional knowledge, thus making it very difficult to detect P. cinnamomi on a wide scale.

The detection method of the RPA-LFD assay was judged by the test line and the control line which could not detect by gel except basic RPA method. So, we could not use a similar pattern of the figure to show the sensitivity either dipstick or gel or both. However, the three methods were used for detecting P. cinnamomi based on the target Pcinn13739, which have different sensitivity. The sensitivity of the RPA-LFD assay (10 pg) for detecting P. cinnamomi was 100-fold higher than conventional PCR (1 ng) assay. RPA-LFD testing was advantageous, because it was time-saving, sensitive, and required no specialist operators. Dai et al. (2019) developed LAMP assays for detecting P. cinnamomi in soil and targeted a new target gene (Pcinn100006) that had been identified from genomic sequencing data. Over recent years, there have been many reports of pathogens causing crown and root rot in Rhododendron pulchrum, including P. pini (Xu et al., 2021), Phytopythium littorale (Li et al., 2021), and Phytopythium helicoides (Chen et al., 2021) except P. cinnamomi. Therefore, more isolates need to be used to verify the specificity of the RPA-LFD assay, especially those causing diseases in the same host. The number of species (118 isolates from 64 species) tested in this study is greater than the numbers tested in previous studies [76 isolates from 38 species (Dai et al., 2020), 50 isolates from 31 species (Dai et al., 2019), 53 isolates from 22 species (Engelbrecht et al., 2013), 74 isolates from 16 species (Williams et al., 2009), 37 isolates from 29 species (Kong et al., 2003)]. Based on these numbers, RPA primers and probe designed in RPA-LFD assay may be the most reliable for the specific detection of P. cinnamomi. Among the closely related genera, P. parvispora also gave negative results in Pcinn13739 -RPA-LFD assay. Screening for unique target genes was the most critical step for establishing fast and accurate molecular detection methods. ITS region, Ypt1, and β-tubulin loci have been used to identify Phytophthora (Kroon et al., 2004; Yang and Hong, 2018). However, due to the homology of these target genes, molecular detection method based on these genes often generate false positives (Manisha et al., 2017). Dai et al. (2019) developed a LAMP assay to detect P. cinnamomi. However, the LAMP-based assay requires at least four primer pairs and an amplification time of 1 h. Dai et al. (2020) designed a pair of specific primers to develop an RPA-LFD assay for the P. cinnamomi RxLR effector gene PHYCI_587572. However, effectors are secreted by the pathogen during its interaction with the host, interfering with the immune response of the plant and promoting infection (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Evolutionary analysis shows that RxLR and CRN effectors undergo genetic selection pressure (Jiang et al., 2008). Specific primers designed to target RxLR effector genes can result in the failure to amplify their target genes in an appropriate manner or generate false positives due to the presence of genetic selection pressure. With the rapid development of bioinformatics, the combination of bioinformatic analysis and comparative genomics to search for specific target genes has been widely applied, such as Pectobacterium species (Ahmed et al., 2018), P. cinnamomi (Dai et al., 2019), and Schistosoma japonicum (Guo et al., 2021).

In this study, based on public genomic sequence data and bioinformatic analysis of several Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium species, we have identified a new target gene, Pcinn13739, and used as a target gene to develop the conventional PCR and RPA-LFD assays. Unlike the conventional PCR that requires denaturation, annealing, and extension and requires gel electrophoresis for imaging, RPA only requires 20 min of isothermal amplification at 37°C and 5 min of LFD to complete the visualization and detection. There were no other report of isothermal amplification methods such as strand displacement isothermal amplification (SDA), helicase-dependent DNA isothermal amplification (HDA), and rolling loop isothermal amplification technology (RCA) for P. cinnamomi detection. CRISPR assay has become a very popular technology and has been deployed in a huge range of applications. The CRISPER/Cas12a assay is gradually being applied for the detection of pathogens (Chen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). In future, maybe a simple, rapid, sensitive, and unaided eye visualization CRISPR-Cas12a detection system will be developed for molecular identification of P. cinnamomi without requiring technical expertise or ancillary equipment.

A new target gene, Pcinn13739, was identified by aligning the whole-genome sequences of P. cinnamomi with other species of Phytophthora, Phytopythium, and Pythium. We designed specific primers (Pcinn13739-RPA-F and Pcinn13739-R) to this new target gene. The specificity of this target gene was then tested in various assays by testing 50 isolates of other Phytophthora species, six Phytopythium species, seven Pythium species, 32 fungal species, and Bursaphelenchus species. The Pcinn13739-RPA-LFD detection assay was shown to detect 10 pg of P. cinnamomi gDNA in a 50-µl reaction. This assay also detected P. cinnamomi in the artificially inoculated fruit of M. pumila “FuJi,” the leaves of R. pulchrum, the roots of sterile L. polyphyllus, and in artificially inoculated soil. The detection method that we have developed, based on the RPA assay with LFDs, can be visualized without the need for extensive equipment, thus facilitating the early detection and prediction of P. cinnamomi and serving as an early warning system.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

ZC conceptualized and designed the research, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. BJ, JZ, and HH participated in and discussed the experimental design. TD revised the manuscript and directed the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Reference: 2021YFD1400100 and 2021YFD1400103), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK 20191389), the Jiangsu University Natural Science Research Major Project (Reference: 21KJA220003), and the Qinglan Project of 2020 and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

The authors would like to thank Cuiping Wu at Jiangsu Costoms for providing the isolates and DNAs of Phytophthora species used in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.923700/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Sequence of the Pcinn13739 gene of Phytophthora cinnamomi. The nucleotides targeted by the forward primer (Pcinn13739RPA-F), the Pcinn13739RPA-Probe, and the reverse primer (Pcinn13739RPA-R) in the novel recombinant polymerase amplification method are located below their respective arrows. The arrows indicate the direction of amplification.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Evaluation of specificity of the PCR assay based on the target Pcinn16994 and Pcinn18321. (A) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn16994-F and Pcinn16994-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn18321-F and Pcinn18321-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were also detected in samples using gDNA from other Phytophthora species, indicating a lack of specificity in detection of P. cinnamomi DNA. Pcinn16994 and Pcinn18321 were found to be non-specific for detecting P. cinnamomi. Marker DL2000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Negative control (NTC).

Supplementary Figure 3 | Evaluation of specificity of the PCR assay based on the target Pcinn10079 and Pcinn1025. (A) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn10079-F and Pcinn10079-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn1025-F and Pcinn1025-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were also detected in samples using gDNA from other Phytophthora species, indicating a lack of specificity in detection of P. cinnamomi DNA. Pcinn10079 and Pcinn1025 were found to be non-specific for detecting P. cinnamomi. Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Negative control (NTC).

Supplementary Figure 4 | Evaluation of specificity of the PCR assay based on the target Pcinn11754 and Pcinn1601. (A) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn11754-F and Pcinn11754-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn1601-F and Pcinn1601-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were also detected in samples using gDNA from other Phytophthora species, indicating a lack of specificity in detection of P. cinnamomi DNA. Pcinn11754 and Pcinn1601 were found to be non-specific for detecting P. cinnamomi. Marker DL2000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Negative control (NTC).

Supplementary Figure 5 | Evaluation of specificity of the PCR assay based on the target Pcinn137495 and Pcinn14424. (A) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn137495-F and Pcinn137495-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn14424-F and Pcinn14424-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were also detected in samples using gDNA from other Phytophthora species, indicating a lack of specificity in detection of P. cinnamomi DNA. Pcinn137495 and Pcinn14424 were found to be non-specific for detecting P. cinnamomi. Marker DL2000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Negative control (NTC).

Supplementary Figure 6 | Evaluation of specificity of the PCR assay based on the target Pcinn17552. Conventional PCR products amplified with primers Pcinn17552-F and Pcinn17552-R are detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were also detected in samples using gDNA from other Phytophthora species, indicating a lack of specificity in detection of P. cinnamomi DNA. Pcinn17552 was found to be non-specific for detecting P. cinnamomi. Marker DL1000 (Takara Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). Negative control (NTC).

Supplementary Figure 7 | Maximum parsimony phylogeny for Pcinn13739. The phylogenetic relationship of Pcinn13739 derived from maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis. BLAST searches revealed Pcinn13739 in different branches of a phylogenetic tree with nine closely related genes (https://fungidb.org/fungidb/app/search/transcript/UnifiedBlast).

Supplementary Table 1 | Publicly available genome sequences of 34 Phytophthora species, eight Pythium species, five Fusarium species, and Phytopythium vexans.

Supplementary Table 2 | Ten loci were randomly selected for screening by conventional PCR assays from more than 1,000 Phytophthora cinnamomi–specific putative genes.

Ahmed, F. A., Larrea-Sarmiento, A., Alvarez, A. M. (2018). Genome-informed diagnostics for specific and rapid detection of Pectobacterium species using recombinase polymerase amplification coupled with a lateral flow device. Sci. Rep. 8, 15972. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34275-0

Beakes, G. W., Glockling, S. L., Sekimoto, S. (2012). The evolutionary phylogeny of the oomycete “fungi”. Protoplasma 249, 3–19. doi: 10.1007/s00709-011-0269-2

Bi, X. Q., Hieno, A., Otsubo, K., Kageyama, K., Liu, G., Li, M. Z. (2019). A multiplex PCR assay for three pathogenic Phytophthora species related to kiwifruit diseases in china. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 85, 12–22. doi: 10.1007/s10327-018-0822-3

Chen, J. S., Ma, E., Harrington, L. B. (2018). CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Sci 360, 436–439. doi: 10.1126/science

Chen, Z. P., Yang, X., Xu, J. X., Jiao, B. B., Li, Y. X., Xu, Y., et al. (2021). First report of Phytopythium helicoides causing crown and root rot of Rhododendron pulchrum in china. Plant Dis. 105, 713–713. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-20-1798-PDN

Corcobado, T., Cubera, E., Juárez, E. (2014). Drought events determine performance of quercus ilex seedlings and increase their susceptibility to Phytophthora cinnamomi. Agric. For. Meteorol. 192, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2014.02.007

Daher, R. K., Stewart, G., Boissinot, M., Bergeron, M. G. (2016). Recombinase polymerase amplification for diagnostic applications. Clin. Chem 62, 947–958. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.245829

Dai, T. T., Wang, A., Yang, X. (2020). PHYCI_587572: An RxLR effector gene and new biomarker in a recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi. Forests 11, 306. doi: 10.3390/f11030306

Dai, T. T., Yang, X., Hu, T. (2019). A novel LAMP assay for the detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi utilizing a new target gene identified from genome sequences. Plant Dis. 103, 3101–3107. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-19-0781-RE

De Cock, A. W. A. M., Lodhi, A. M., Rintoul, T. L., Bala, K., Robideau, G. P., Abad, Z. G., et al. (2015). Phytopythium: molecular phylogeny and systematics. Persoonia 34, 25–39. doi: 10.3767/003158515X685382

Dunstan, W. A., Rudman, T., Shearer, B. L. (2010). Containment and spot eradication of a highly destructive, invasive plant pathogen (Phytophthora cinnamomi) in natural ecosystems. Biol. Invasions 12, 913–925. doi: 10.1007/s10530-009-9512-6

Engelbrecht, J., Duong, T. A., Prabhu, S. A. (2021). Genome of the destructive oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi provides insights into its pathogenicity and adaptive potential. BMC Genomics 22, 302. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07552-y

Engelbrecht, J., Duong, T. A., van den Berg, N. (2013). Development of a nested quantitative real-time PCR for detecting phytophthora cinnamomi in persea americana rootstocks. Plant Dis. 97, 1012–1017. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-12-1007-RE

Erwin, D. C., Ribeiro, O. K. (1996). Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide. APS Press, St. Paul Mycologia 90, 1092–1093.

Eshraghi, L., Aryamanesh, N., Anderson, J. P., Shearer, B., McComb, J. A., Hardy, G. E. S. J., et al. (2011). A quantitative PCR assay for accurate in planta quantification of the necrotrophic pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 131, 419–430. doi: 10.1007/s10658-011-9819-x

Guo, Q. H., Zhou, K. R., Chen, C., Yue, Y. C., Shang, Z., Zhou, K. K., et al. (2021). Development of a recombinase polymerase amplification assay for Schistosomiasis japonica diagnosis in the experimental mice and domestic goats. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.791997

Hardham, A. R., Blackman, L. M. (2018). Phytophthora cinnamomi. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 260–285. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12568

Jiang, R., Tripathy, S., Govers, F., Tyler, B. M. (2008). RXLR effector reservoir in two Phytophthora species is dominated by a single rapidly evolving superfamily with more than 700 members. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4874–4879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709303105

Kamoun, S., Furzer, O., Jones, J. D. G., Judelson, H. S., Ali, G. S., Dalio, R. J. D., et al. (2015). The top 10 oomycete pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16, 413–434. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12190

Kong, P., Hong, C. X., Richardson, P. A. (2003). Rapid detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi using PCR with primers derived from the Lpv putative storage protein genes. Plant Pathol. 52, 681–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2003.00935.x

Kroon, L. P. N. M., Bakker, F. T., Bonants, P. J., Flier, W. G. (2004). Phylogenetic analysis of Phytophthora species based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences-ScienceDirect. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 766–782. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.03.007

Lan, C. Z., Ruan, H. C., Yao, J. A. (2016a). First report of Phytophthora cinnamomi causing root and stem rot of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) in china. Plant Dis. 100, 2537–2537. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-16-0345-PDN

Lan, C. Z., Ruan, H. C., Yao, J. A. (2016b). First report of Phytophthora cinnamomi causing root rot of Castanea mollissima (Chinese chestnut) in china. Plant Dis. 100, 1248–1248. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-15-1105-PDN

Li, S. Y., Cheng, Q. X., Wang, J. M., Li, X. Y., Zhang, Z., Gao, S., et al. (2018). CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted nucleic acid detection. Cell Discov 4, 20. doi: 10.1038/s41421-019-0083-0

Li, Y. X., Feng, Y. F., Wu, C. P., Xue, J. X., Jiao, B. B., Li, B., et al. (2021). First report of phytopythium litorale causing crown and root rot on Rhododendron pulchrum in china. Plant Dis. 105, 4173–4173. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-21-0830-PDN

Mamiya, Y. (1975). The life history of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus lignicolus. Jpn. J. Nematol 5, 16–25. doi: 10.14855/jjn1972.5.16

Manisha, K., Diane, W., Dunstan, W. A., Hardy, S. J., Vera, A, Burgess, T. I., et al. (2017). Pathways to false positive diagnoses using molecular genetic detection methods; Phytophthora cinnamomi a case study. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364, fnx009. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx009

McCarren, K. L., McComb, J. A., Shearer, B. L., Hardy, G. E. S. (2005). The role of chlamydospores of Phytophthora cinnamomi-a review. Aust. Plant Pathol. 34, 333–338. doi: 10.1071/AP05038

McCown, B. H., Loyd, L. (1981). Woody plant medium (wpm) - a mineral nutrient formulation for microculture of woody plant-species. Hortscience 16, 453.

Nechwatal, J., Jung, T. (2021). A study of phytophthora spp. in declining highbush blueberry in germany reveals that P. cinnamomi can thrive under central european outdoor conditions. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 128, 769–774. doi: 10.1007/s41348-021-00445-y

Notomi, T., Okayama, H., Masubuchi, H., Yonekawa, T., Hase, T. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E63. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181f49ac7

Rands, R. D. (1922). Streepkanker van kaneel, veroorzaakt door Phytophthora cinnamom in. sp. Meded Inst Plantenziekt 54, 1–53.

Rodriguez-Romero, M., Godoy-Cancho, B., Calha, I. M., Passarinho, J. A., Moreira, A. C. (2021). Allelopathic effects of three herb species on Phytophthora cinnamomi, a pathogen causing severe oak decline in mediterranean wood pastures. Forests 12, 285. doi: 10.3390/f12030285

Tong, X. Q., Wu, J. Y., Mei, L., Wang, Y. J. (2022). Detecting Phytophthora cinnamomi associated with dieback disease on Carya cathayensis using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. PloS One 16, e0257785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257785

Umami, M., Parker, L. M., Arndt, S. K. (2021). The impacts of drought stress and Phytophthora cinnamomi infection on short-term water relations in two year-old eucalyptus obliqua. Forests 12, 109. doi: 10.3390/f12020109

Wang, H., Qi, M., Cutler, A. J. (1993). A simple method of preparing plant samples for PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 4152–4154. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.17.4153

Williams, N., Hardy, G. E. S. J., O’Brien, P. A. (2009). Analysis of the distribution of Phytophthora cinnamomi in soil at a disease site in western australia using nested PCR. For. Pathol. 39, 95–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2008.00567.x

Xu, Y., Yang, X., Li, Y. X., Chen, Z. P., Dai, T. T. (2021). First report of Phytophthora pini causing foliage blight and shoot dieback of Rhododendron pulchrum in china. Plant Dis. 105, 1229–1229. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-20-1422-PDN

Yang, X., Hong, C. (2018). Differential usefulness of nine commonly used genetic markers for identifying Phytophthora species. Front. Microbiol. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02334

Zentmyer, G. A. (1980). Phytophthora cinnamomi and the diseases it causes. Am. Phytopathol Soc St. Paul MN.

Zhou, Q. Z., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, H. M., Zhang, X. Y., Lu, Q. A. (2022). Rapid on-site detection of the Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral flow dipstick that eliminates interference from primer-dependent artifacts. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.856109

Keywords: Phytophthora dieback, Phytophthora cinnamomi, rapid diagnosis, recombinase polymerase amplification, lateral flow dipstick

Citation: Chen Z, Jiao B, Zhou J, He H and Dai T (2022) Rapid detection of Phytophthora cinnamomi based on a new target gene Pcinn13739. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:923700. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.923700

Received: 19 April 2022; Accepted: 04 August 2022;

Published: 25 August 2022.

Edited by:

Thuy Le, Duke University, United StatesReviewed by:

Davide Palmieri, University of Molise, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Chen, Jiao, Zhou, He and Dai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tingting Dai, MTM3NzA2NDcxMjNAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.