- 1Centre for Structural Systems Biology, Hamburg, Germany

- 2Heinrich Pette Institut, Leibniz-Institut für Experimentelle Virologie, Hamburg, Germany

- 3Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany

- 4University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

- 5Research Centre for Infectious Diseases, School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 6Burnet Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Apicomplexan parasites, such as human malaria parasites, have complex lifecycles encompassing multiple and diverse environmental niches. Invading, replicating, and escaping from different cell types, along with exploiting each intracellular niche, necessitate large and dynamic changes in parasite morphology and cellular architecture. The inner membrane complex (IMC) is a unique structural element that is intricately involved with these distinct morphological changes. The IMC is a double membrane organelle that forms de novo and is located beneath the plasma membrane of these single-celled organisms. In Plasmodium spp. parasites it has three major purposes: it confers stability and shape to the cell, functions as an important scaffolding compartment during the formation of daughter cells, and plays a major role in motility and invasion. Recent years have revealed greater insights into the architecture, protein composition and function of the IMC. Here, we discuss the multiple roles of the IMC in each parasite lifecycle stage as well as insights into its sub-compartmentalization, biogenesis, disassembly and regulation during stage conversion of P. falciparum.

Introduction

The Apicomplexa represent a phylum of eukaryotic, single celled organisms that include human (i.e., Plasmodium spp., Toxoplasma gondii, and Cryptosporidium spp.) and livestock (i.e., T. gondii, Eimeria spp., and Babesia spp.) parasites with a severe impact on global health and socio-economic development. Human malaria parasites, Plasmodium spp., are the most medically important member of this distinct phylogenetic group and cause more than 400,000 deaths per year (WHO, 2018). Antimalarial resistant P. falciparum, the most lethal human malaria parasite species, are spreading (Dondorp et al., 2009; Imwong et al., 2017; Woodrow and White, 2017) and no efficacious vaccine has been developed to date. The devasting impact on endemic communities due to malaria has the potential to worsen with climate change and disruption of malaria control measures from outbreaks of other infectious diseases such as SARS-CoV-2 and Ebola (Rogerson et al., 2020; Sherrard-Smith et al., 2020).

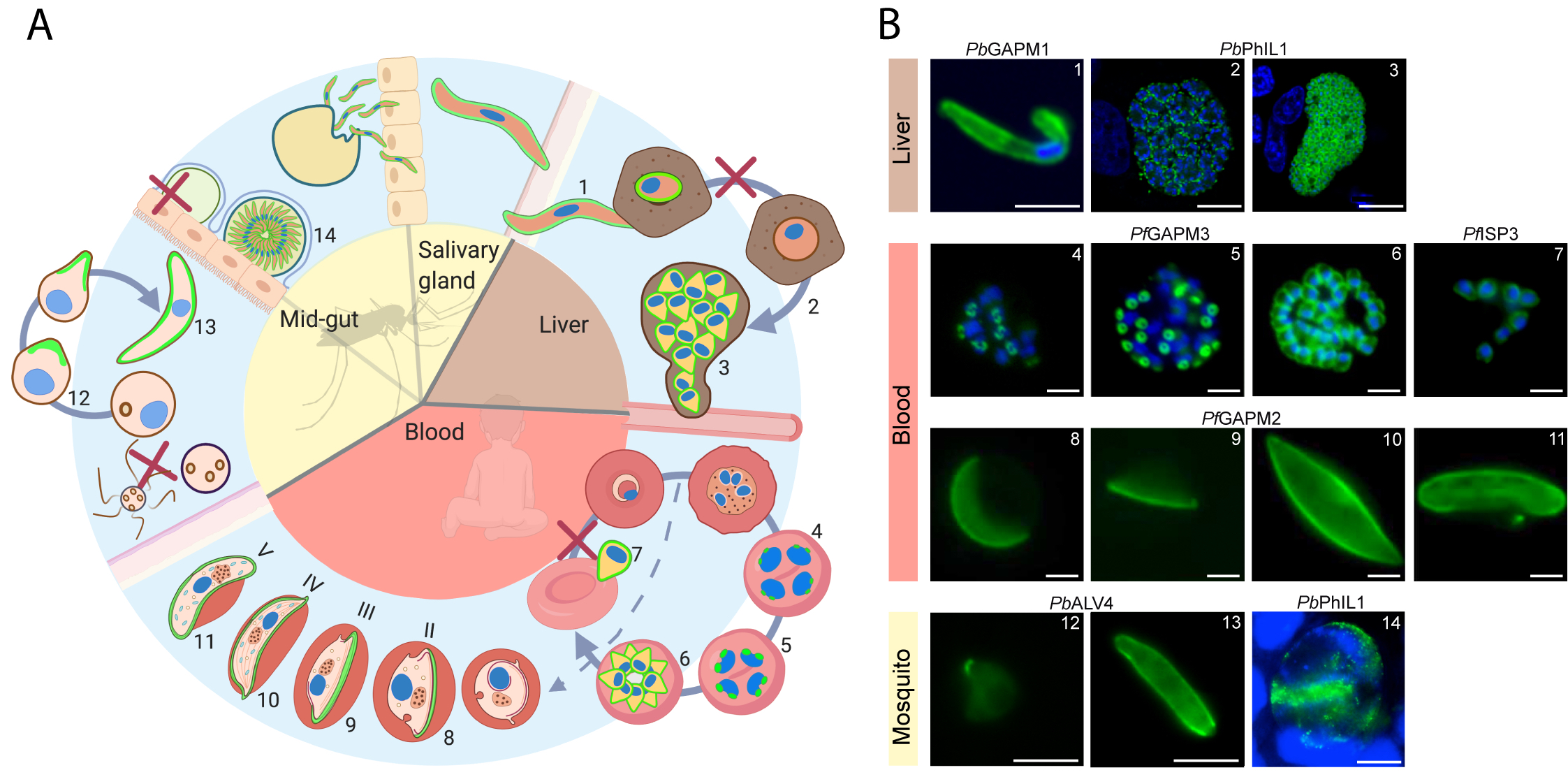

Human malaria infection begins after a bite of a female Anopheles spp. mosquito that injects the parasite into the skin (Figure 1). These parasites, called sporozoites, actively enter blood vessels and reach the liver where they invade hepatocytes. Within hepatocytes, the elongated sporozoites transform into spherical hepatic stages that replicate via multiple fission events and produce thousands of merozoites contained in host-cell derived vesicles known as merosomes (Stanway et al., 2011). The merozoites are released from the liver before they rapidly invade and multiply within red blood cells (RBCs); with this occurring repeatedly every ~48 h for P. falciparum. Mass proliferation in blood stages is responsible for the clinical manifestations of malaria. Some RBC-infecting parasites differentiate into sexual forms called gametocytes, which can be taken up during the blood meal of another mosquito. Male and female gametocytes fuse within the mosquito midgut and form a motile ookinete that transmigrates the mosquito midgut epithelium and differentiates into an oocyst. Oocyst maturation results in the formation of up to 2,000 sporozoites (Stone et al., 2013), which in turn are transmitted to the host during another blood meal of the mosquito.

Figure 1 IMC dynamics through the malaria parasite life cycle. (A) Schematic representation of the lifecycle through the mosquito and human host. The IMC in different stages is highlighted in green. IMC disassembly is marked with a red cross. (B) Fluorescent microscopy images showing the IMC (green) at different stages in the parasite lifecycle. Specific IMC-GFP fusion proteins are indicated above the images. Blue; DAPI stain. Numbers in B refer to those in (A) 1 = Sporozoite (Kono et al., 2012), 2 = IMC biogenesis during liver cell schizogony (Saini et al., 2017), 3 = mature liver schizont (Saini et al., 2017), 4–6 = IMC biogenesis during schizogony in erythrocytes (Kono et al., 2012), 7 = free merozoites (Hu et al., 2010), 8–11 = developing IMC during gametocytogenesis (Kono et al., 2012), 12–13 = IMC biogenesis during ookinetogenesis (Kono et al., 2012), 14 = oocyst (Saini et al., 2017). Scale bars, 2 µm (micrographs 4–11) and 5 µm (micrographs 1, 12, 13, 14) 10 µm (micrographs 2, 3).

In this review we walk through the malaria parasite’s lifecycle and focus on the role of the inner membrane complex (IMC) as the parasite transitions between various host cells such as RBCs, hepatocytes and mosquito midgut cells. The double membrane IMC organelle underlies the plasma membrane (PM) and is present in four of the morphologically distinct stages of the parasite’s lifecycle. These different parasite stages are not only characterized by their distinct physiology, but also by dramatic changes in size, shape and cellular architecture, facilitating growth and multiplication in diverse cellular environments. Here we primarily focus on the IMC of the human pathogen P. falciparum, with additional data from other Plasmodium spp. and T. gondii included to expand and sharpen our functional understanding of this unique membranous system.

The Inner Membrane Complex: A Characteristic Cellular Structure Shared Across the Alveolata

Plasmodium spp., along with T. gondii, ciliates, and dinoflagellates are members of the Alveolata, a group of diverse unicellular eukaryotes. Evidence for a relationship between the diverse organisms that make up this phylogenetic supergroup only became clear from rRNA-sequence derived phylogenetic analysis (Wolters, 1991). Identification of a double membraned organelle below the PM (together called a pellicle) as a synapomorphic morphological feature, originating in ancestral Alveolata and shared across the supergroup, supports the evolutionary relationship between these unicellular eukaryotes (Cavalier-Smith, 1993).

The double membrane organelle underlying the PM, consisting of a series of flattened vesicles and interacting proteins, termed alveoli in ciliates, amphiesma in dinoflagellates and the IMC in the Apicomplexa, fulfills various functions depending on the organism’s diverse lifestyle and habitat. In aquatic ciliates and dinoflagellates, the alveoli play a structural role and can serve as a calcium storage organelle (Länge et al., 1995; Kissmehl et al., 1998; Ladenburger et al., 2009). In the endoparasites belonging to the Apicomplexa, the IMC has evolved additional functions that facilitate the unique strategies the parasites use to survive. As in the ciliates and dinoflagellates, the IMC of apicomplexan parasites provides structural support. However, the IMC also acts as a scaffold during the formation of daughter cells (Kono et al., 2012) and anchors the actin-myosin motor used for the gliding motility that powers host-cell invasion of these parasites, known as the glideosome (Keeley and Soldati, 2004). Like the secretory organelles (Rhoptries, Micronemes, and dense granules)—that form the core of the apical complex and have roles in motility/host cell invasion—the IMC is formed de novo during cytogenesis, starting at the apical pole of the parasite, and is most likely derived from Golgi vesicles (Bannister et al., 2000).

The large diversity in the functions and physiology of the pellicle are not limited to just the groups across the Alveolata, as the biology of the IMC also differs markedly between different apicomplexan parasites. Two examples of this can be found when comparing the IMC of the well-studied parasites P. falciparum and T. gondii. In the asexual cycle of P. falciparum malaria parasites, IMC biogenesis occurs de novo during schizogony (Kono et al., 2012). In T. gondii, the IMC is recycled from the mother cell into the forming daughter cells along with de novo biogenesis of new IMC double membrane during endodyogeny (Ouologuem and Roos, 2014). In T. gondii, the IMC and its associated glideosome are important in egress (Frénal et al., 2010) while this does not appear to be the case in Plasmodium spp. (Perrin et al., 2018).

The diversity in the IMC goes further with differences seen between parasites in different Plasmodium species (Ngotho et al., 2019) and beyond this to large morphological and functional differences in the IMC between each unique P. falciparum parasite stage as we discuss in this review.

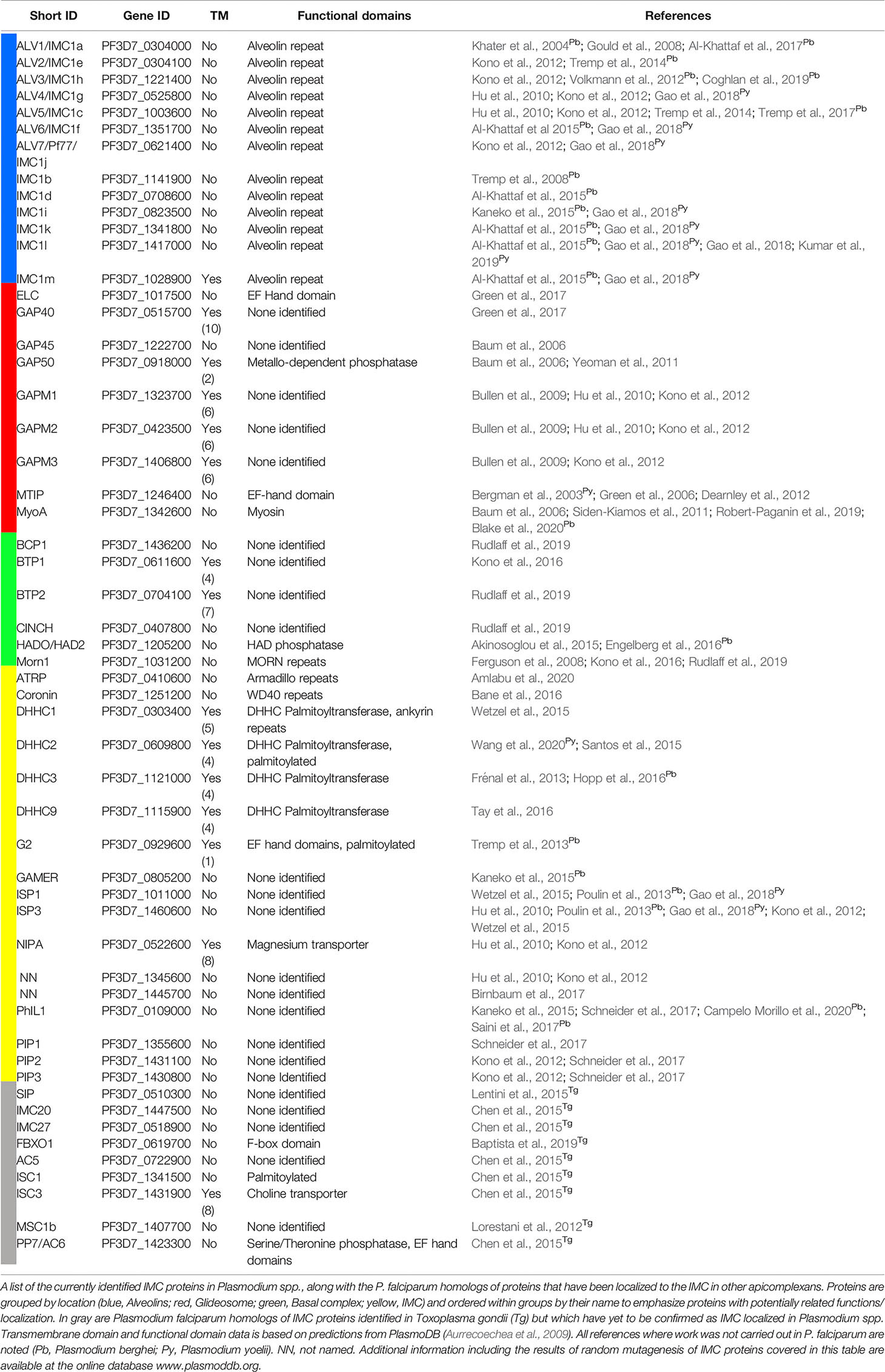

Defining The Inner Membrane Complex: Protein Composition and Complex Formation

To date ~45 IMC proteins have been identified in Plasmodium spp. (Table 1). Phylogenetic profiling of known IMC proteins has shown that the evolution of the IMC involved the repurposing of several ancestral eukaryotic proteins, such as coronin, together with the innovation of alveolate-specific proteins that occurred early in the Alveolata lineage such as the alveolins (Kono et al., 2012). More recent evolution of Plasmodium spp. specific proteins such as PF3D7_1345600 has led to a set of taxon-specific IMC proteins that facilitate the adaptation of the IMC to taxon-specific niches and functions. This evolutionary diversity mirrors the spectrum of functionalities provided by the IMC, from key roles in basic structural integrity for all Alveolates to the machinery that allows endoparasites to invade into and divide within specific host cells.

Table 1 Plasmodium spp. IMC proteins and other apicomplexan IMC proteins with P. falciparum homologs.

The best studied group of IMC proteins are components of the motor complex that drives the locomotion of all motile parasite stages—also referred to as the “glideosome” (Table 1) (Webb et al., 1996; Opitz and Soldati, 2002; Baum et al., 2006). This actin-myosin motor complex powers the motility needed for transmigration, gliding, invasion and potentially egress (Frénal et al., 2010); the physiological trademark of the motile merozoite, sporozoite and ookinete stages of parasite development. Although multiple components of the glideosome such as the glideosome-associated proteins GAP40 GAP45, GAP50, GAP70, and GAPMs (Gaskins et al., 2004; Bullen et al., 2009; Frénal et al., 2010; Yeoman et al., 2011) together with Myosin A (MyoA) (Pinder et al., 1998; Baum et al., 2006; Ridzuan et al., 2012), the myosin A tail-interacting protein [MTIP in Plasmodium spp., or myosin light chain (MLC1) in T. gondii] (Herm-Götz et al., 2002; Bergman et al., 2003) and the “essential light chain 1” protein (ELC1) (Green et al., 2017) have been identified, a comprehensive and systemic identification of all components of the glideosome has not been performed. Recent years have uncovered some structural insights into this protein complex, but this improved understanding is still limited to individual components (Bosch et al., 2006; Bosch et al., 2007; Bosch et al., 2012; Boucher and Bosch, 2014) or to sub-complexes such as the trimeric structure composed of MyoA, ELC1 and MLC1 (Moussaoui et al., 2020; Pazicky et al., 2020) with no structural information on the entire glideosome complex.

Another interesting group of proteins are the so called alveolins, an Alveolata specific and conserved multi-protein family encompassing at least 13 proteins (Table 1) (Gould et al., 2008; Kono et al., 2012; Volkmann et al., 2012; El-Haddad et al., 2013; Tremp et al., 2014; Al-Khattaf et al., 2015). A representative alveolin was initially identified in T. gondii and named Inner Membrane Complex Protein 1 (TgIMC1) (Mann and Beckers, 2001). Alveolins are peripheral membrane proteins that constitute a subpellicular network of proteins located at the cytoplasmic face of the IMC. They are characterized by the presence of one or more highly conserved domains composed of tandem repeat sequences and were recognized as a unique protein family shared across all alveolates (Gould et al., 2008; Kono et al., 2012; El-Haddad et al., 2013; Al-Khattaf et al., 2015). Members of this family show stage specific expression patterns in P. falciparum and have been implicated in parasite morphogenesis and gliding motility at least in sporozoites and ookinetes, although the precise molecular details for these roles have yet to be elucidated for alveolins of Plasmodium spp. (Khater et al., 2004; Tremp et al., 2008; Volkmann et al., 2012). Stage specific transcriptomics in P. falciparum (López-Barragán et al., 2011; Gómez-Díaz et al., 2017; Zanghì et al., 2018) show that some alveolins are expressed across all lifecycle stages (e.g., IMC1a/ALV1, IMC1c/ALV5) while others seem to be absent in specific stages (e.g., IMC1f/ALV6 in gametocytes, IMC1l in asexual blood stages) or are exclusively expressed in one specific stage (e.g., IMC1i in ookinetes). A comprehensive detailed functional mapping of this multi-gene family across different stages of the P. falciparum lifecycle will be instrumental to understand the precise function of individual alveolins.

Beside the alveolins, other additional IMC associated peripheral membrane proteins like the IMC sub-compartment-proteins (ISPs) (Beck et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2010) have been characterized (Tonkin et al., 2004; Fung et al., 2012; Poulin et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). In contrast to integral membrane proteins of the IMC that are most likely trafficked via the ER and Golgi to their final destination (Yeoman et al., 2011), the majority of these peripheral membrane proteins are linked to the IMC membrane by their lipid anchors. For example, the ISP proteins as well as GAP45 depend on their N-terminal palmitoylation and myristoylation motif for membrane association (Wetzel et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2020). This occurs via co-translational and post-translation modification by the cytosolic N-myristoyltransferase (Gunaratne et al., 2000) and IMC embedded palmitoyl acyl transferases (Beck et al., 2013; Frénal et al., 2013; Wetzel et al., 2015). The alveolins, however, do not display a dual acylation motif and how they are trafficked to and interact with the IMC has yet to be described.

Inner Membrane Complex Structure and Function Throughout the Plasmodium Life Cycle

The Asexual Blood Stage

Each individual P. falciparum merozoite within the schizont is surrounded by the double-membrane IMC, which sits approximately 20 nm below the PM (Morrissette and Sibley, 2002). The IMC is described as a mono-vesicle in this stage and appears to be continuous in fluorescence microscopy images, although gaps or discontinuities in the merozoite IMC have been observed in cryo-preserved TEM images (Hanssen et al., 2013; Riglar et al., 2013). At each pole of the merozoite is a defined sub compartment of the IMC. At the apical end of the merozoite, the IMC is supported by subpellicular microtubules (SPMs, 2-3 per merozoite) which are anchored in and organized by a series of rings termed polar rings (Morrissette and Sibley, 2002). At the basal end of the merozoite an additional structure, referred to as the basal complex is located which was first described in T. gondii (Ferguson et al., 2008; Hu, 2008; Lorestani et al., 2010).

The de novo biogenesis of the IMC has been studied in some detail in P. falciparum by fluorescence microscopy (Yeoman et al., 2011; Dearnley et al., 2012; Kono et al., 2012; Ridzuan et al., 2012). This process occurs during schizogony where a new IMC is formed for each of the 16–32 individual daughter merozoites in a schizont (Figure 1). The IMC of the growing daughter cells is established at the apical end of each new merozoite prior to nuclear division. The nucleation of the nascent IMC is closely associated with the centrosome placing it in the center of the developing IMC structure (Kono et al., 2012). The budding IMC grows from a point at the apical end into a ring until, at the end of schizogony; it has expanded to completely cover the newly formed daughter cell. During this process, the basal complex marks the leading edge of the growing IMC and migrates from the apical pole of the daughter cell to the basal pole where it resides after the completion of schizogony (Kono et al., 2016). PfMORN1 (Ferguson et al., 2008; Kono et al., 2016), PfBTP1 (Kono et al., 2016), PfBTP2 (Rudlaff et al., 2019), PfBCP1 (Rudlaff et al., 2019), PfHAD2a (Engelberg et al., 2016), and PfCINCH (Rudlaff et al., 2019) are well established basal complex markers. Parasites deficient in PfCINCH have impaired segmentation of daughter cells, suggesting this protein has an essential role in contraction of the basal complex and pinching off of newly developed daughter cells (Rudlaff et al., 2019) and highlighting the important role of the IMC during cytokinesis. While in P. falciparum, how this contraction works remains unknown, in T. gondii, the apparent role of the myosin, MyoJ, in the contraction implies a mechanism involving the actin-myosin motor (Frénal et al., 2017).

Another process that remains mechanistically completely unknown is the rapid disassembly of the IMC after successful re-invasion of the merozoite into a new RBC. Once invasion is complete, the IMC as a central structure for cytokinesis and motility has outlived its purpose and needs to be disassembled to allow for growth and division of the parasite. The disassembly of the entire IMC may happen in as little as 15 min (Riglar et al., 2013) but definitely appears to be completed within 1 h. How this task is achieved, how it is regulated and what happens to the lipids and proteins from the now superfluous double-membrane structure remains to be explored.

The Sexual Blood Stage: Gametocytes

To achieve transmission from the vertebrate host to the mosquito the parasite produces male and female gametocytes. Sexual stage conversion in P. falciparum is characterized by drastic morphological changes of the parasite that occur over approximately 10–12 days and includes five (I to V) morphologically distinct stages (Figure 1) (Fivelman et al., 2007). Fully mature gametocytes display a falciform shape, from which P. falciparum derives its name. During their maturation, gametocytes lengthen significantly with fully mature gametocytes being 8–12 µm in length, approximately six times bigger than merozoites. Early in gametocytogenesis, their distinct morphology permits the gametocyte to sequester and develop within the bone marrow. Once fully mature, gametocytes migrate back into circulation where their morphology enables them to avoid immune clearance during passage through splenic sinuses unlike asexual parasites (Joice et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2018; De Niz et al., 2018; Obaldia et al., 2018).

The double membrane IMC below the PM in gametocytes was first identified 40 years ago (Smalley and Sinden, 1977). In P. falciparum it is organized in distinct vesicles or plates numbering between 11 (Meszoely et al., 1987) and 13 (Kono et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017) per gametocyte. The IMC plates are thought to be connected via proteinaceous “sutures”, although no direct correlation between the distinct delineating lines seen in fluorescence microscopy and structures in electron microscopy have been made to date. The sutures are hypothesized to support the alignment of microtubules (Kaidoh et al., 1993; Dearnley et al., 2012; Kono et al., 2012) or to connect the IMC with the PM (Meszoely et al., 1987). Presently, two proteins (Pf3D7_1345600 and DHHC1) have been localized to the sutures in gametocytes (Kono et al., 2012; Wetzel et al., 2015), although no functional data connecting these proteins to their distinct localization is available.

Maturation of P. falciparum gametocytes can be accurately assessed by IMC formation. Stage I gametocytes are only distinguishable from asexual trophozoites on the molecular level, through expression of specific marker proteins such as Pfs16 (Bruce et al., 1994) with no IMC proteins detectable at this stage (Dearnley et al., 2012; Kono et al., 2012). Stage II gametocytes are characterized by elongation of the transversal microtubules and the start of IMC biogenesis (Sinden, 1981). IMC marker proteins such as PhIL1 (Schneider et al., 2017), GAP45 (Dearnley et al., 2012) and GAPM2, ISP3 and PF3D7_1345600 (Kono et al., 2012) appear as a spine-like structure with longitudinal orientation in close association with an array of microtubules. Three-dimensional SIM immunofluorescence microscopy shows a ribbon-like arrangement of PhIL1 around the microtubules (Schneider et al., 2017). Although still unclear, it is likely that microtubules provide a scaffold for the placement of the Golgi-derived IMC-bound vesicles that fuse to form the IMC. During stage III, the IMC membranes further wrap around the parasite and show thickened areas at the growing edge (Schneider et al., 2017). This then proceeds to stage IV where the parasite is maximally elongated and has a “banana-like” structure with the IMC completely surrounding the parasites. The final stage V is characterized by disassembly of the microtubule network until only small patches are observed below the IMC, a process initiated by an unknown signal. In parallel with this process, the parasite rounds up and the sutures become less pronounced (Dearnley et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017). Disassembly of the microtubule network leads to changes in the rigidity and deformation of the parasite (Dearnley et al., 2012) that promotes the reentering of these parasites from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood circulation and their uptake by the mosquito.

During uptake by the mosquito, the gametocytes are activated by external stimuli (reduced temperature, xanthurenic acid and pH rise), round up, egress from the RBC and transform into female macrogametes and exflagellated male microgametes. This transformation happens very rapidly (∼2 min) (Sologub et al., 2011) and is highly dependent on disassembly of the IMC as a prerequisite for rounding up. Again it is unclear how this process is initiated, what its molecular basis is, or the fate of the membrane following disassembly. An interesting observation is the formation of nanotubules between forming gametes after gametocyte activation (Rupp et al., 2011). These are membranous cell-to-cell connections that may facilitate mating of the male and female gametes. The authors provide an intriguing hypothesis, which proposes that these may be formed out of the recycled IMC-vesicles as their appearance is coincident with the disappearance of the IMC (Rupp et al., 2011). Interestingly, a recent study in P. berghei suggests that active trans-endothelial migration of gametocytes (De Niz et al., 2018) exhibit an as yet uncharacterized mode of actin-dependent deformability and/or motility that could also be dependent on the IMC.

Taken together, in contrast to its central role in motility in invasion-competent merozoites, ookinetes and sporozoites, the IMCs most prominent role during gametocytogenesis appears to be a structural one which drives this stage’s significant changes in size and shape (Dixon et al., 2012; Kono et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017).

In the Mosquito: From Zygote to Ookinete

Following fusion of the activated male and female gametes in the midgut of mosquitoes, a diploid, non-motile zygote is formed which undergoes meiosis and transforms into immature ookinetes known as retorts (reviewed in Bennink et al., 2016). These intermediate cells develop and 20 h post gametocyte fusion are fully transformed into motile ookinetes (Siciliano et al., 2020), which transmigrate through the epithelial cells to settle beneath the basal lamina of the mosquito midgut (Figure 1).

Like in merozoite maturation in the asexual blood stage, the IMC is formed again de novo during ookinetogenesis, starting as a patch at the apical end of the zygote (Figure 1) (Tremp et al., 2008). The round zygotes undergo huge and rapid morphological changes, gaining a protrusion, elongating and maturing to finally form an elongated, crescent-shaped ookinete (Guttery et al., 2015; Bennink et al., 2016). The ookinete’s apical rings are formed at the same time and organize the SPM of > 40 microtubules (Bertiaux et al., 2020) under the IMC. These are initially seen at the apical protrusion of the zygote but extend during zygote elongation into a “dome-like” structure under the IMC (Wang et al., 2020). The dual acetylated peripheral IMC proteins ISP1 and 3 appear to serve here as a tether linking the SPM with the IMC in order to maintain a proper pellicle cytoskeleton. Congruently, ΔISP1 and ΔISP3 parasites show a reduced rate of zygote to ookinete differentiation, indicating that the IMC has an important role in transitioning from a round zygote to a crescent shaped ookinete (Wang et al., 2020).

Together with its role in mediating some of the large morphological changes that occur during the transformation from round, fertilized zygote to an elongated ookinete, another obvious role of the IMC is the facilitation of ookinete motility. Again, the IMC acts to anchor the glideosome, providing a stable structure from which to produce and exert forward motion. Motility is important for crossing the midgut and establishment of the replicative oocyst stage in the mosquito. Knock out of the IMC protein IMC1b/ALV5 led to reduced ookinete motility and therefore fewer oocysts produced in the mosquito (Tremp et al., 2008). After crossing the mosquito midgut, the ookinete differentiates into an oocyst. The transition from ookinete to early oocyst is also associated with loss of the IMC (Harding and Meissner, 2014) prior to sporogony. No details of this process are known yet, including what triggers and mediates disassembly and what happens to the large amount of the lipid and protein.

Relatively little is known about the architecture and protein composition of the IMC in these mosquito infecting stages. However, freeze fracture SEM images of ookinetes from the poultry parasite P. gallinaceum provide a glimpse of what appears to be a largely distinct IMC morphology from other stages (Alavi et al., 2003). The micrographs show a single vesicle punctured by multiple large pores. The pores have an external diameter of 43 nm and 12-fold symmetry. The single IMC vesicle appears to have a zig-zagged row of proteins connecting it along one edge, which has been termed a suture, as in gametocytes. What these pores are composed of, their function and why they have not been observed in other stages is currently unclear.

Out of the Mosquito: Sporozoite Formation and Motility

Once in the basal lamina the ookinete develops into an oocyst (Figure 1). Sporogony leads to thousands of sporozoites forming within the ~14 days of oocyst development. During sporogony, again, the IMC is formed de novo around each new sporozoite. It appears to be a complex process as the parasite grows larger, transforms from a “solid phase” to a vacuolated phase, undergoes multiple nuclear divisions and forms multiple segregated sporoblasts (Terzakis et al., 1967). Each sporoblast within the oocyst acts as a center for the synchronous budding of hundreds of new sporozoites (Sinden and Matuschewski, 2005). At the initiation of budding, the microtubule organizing center is positioned at the cortex. In a process similar to IMC formation in the merozoite, the apical rings and microtubules are in place and the IMC grows toward the basal end of each elongating parasite until a final contraction at the basal end completes sporogony (Schrevel et al., 2008). The versatile sporozoite emerges from the oocyst (Frischknecht and Matuschewski, 2017), and makes its way to the mosquito salivary glands where it invades first the basal lamina and then the acinar cells (Stering and Aikawa, 1973).

The elongated sporozoite (10–15 µm) is highly motile and moves at speeds of over 2 µm/s (Münter et al., 2009) for multiple minutes. Motility remains after injection into the dermis by the mosquito (Vanderberg, 1974; Amino et al., 2006) until the parasites invade a blood vessel, travel to the liver and finally settle in a hepatocyte. The distinctive crescent sporozoite shape may be due to a linkage of myosin to the subpellicular network (SPN) below the IMC (Khater et al., 2004; Kudryashev et al., 2012). In turn, this shape is likely to contribute to the distinct spiral gliding trajectories of the sporozoite (Akaki and Dvorak, 2005). This unusual gliding motility (Frischknecht and Matuschewski, 2017) depends on proteins of the TRAP (thrombspondin related anonymous protein) family (Sultan et al., 1997). TRAP proteins span the PM and possess a cytoplasmic tail domain that is believed to interact with actin, since mutations in this region led to defects in active locomotion (Ejigiri et al., 2012). TRAP proteins are released from micronemes to the sporozoite surface (Gantt et al., 2000; Carey et al., 2014) and serve as an adaptor and force transmitter between the target cells and the sporozoite.

The sporozoite stage has been studied by cryo-electron tomography, which allows a view of the IMC without artefacts from staining or slicing (Kudryashev et al., 2010). In these cells, the IMC sits approximately 30 nm below the PM and appears to be a highly homogenous flattened vesicle with minor discontinuities noted (Kudryashev et al., 2012).

Into the Blood: Hepatic Schizogony and Merozoite Formation

After invasion of the hepatocyte, the sporozoite dedifferentiates from the elongated motile cell into a rounded cell, starting at its center. This rounding is accompanied by the disassembly of the IMC as well as the sporozoite’s subpellicular network (Jayabalasingham et al., 2010). Intriguingly, the rounding of the sporozoite and disassembly of the IMC does not require a host cell as it can also be triggered outside the cell at 37°C in serum (Kaiser et al., 2003). Early EM images of P. berghei in hepatocytes show the shrinkage of the IMC to cover half the cell at 24 hpi, with just a small section covered at 28 hpi (Meis et al., 1985). This view of IMC disassembly after sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes is supported by fluorescence microscopy studies showing the shrinkage of the IMC to one side of the cell (Kaiser et al., 2003). More recently, EM images appear to show the dispersal of a membrane thought to be the IMC into the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) in hepatocytes infected with P. berghei, which the authors suggest could be a rapid mechanism for clearing this organelle and allowing for the fast growth and multiplication of the parasite (Jayabalasingham et al., 2010). Importantly, IMC disassembly is a prerequisite for the first mass-proliferative stage of schizogony within the host (Meis et al., 1985; Stanway et al., 2011) resulting in up to 29,000 exoerythrocytic merozoites in P. berghei (Baer et al., 2007) and up to 90,000 in P. falciparum (Vaughan et al., 2012). How exactly the disassembly or expulsion of the IMC occurs and what controls it remains to be determined.

Outlook

The IMC is a unique structural compartment that undergoes continuous and profound reconfiguration during the parasite’s lifecycle, mirroring the changes in stage specific architecture and motility that are reliant on IMC function. Although our understanding of the IMC has continuously increased over the years driven by molecular studies in Plasmodium spp. as well as in T. gondii, there are still large gaps in our knowledge and many unanswered questions in the field.

Many evolutionary questions still remain unanswered such as what selection pressures may have led to the evolution of the IMC in the ancestor of alveolates and what contribution did the IMC play in speciation. Clearly, the IMC was repurposed into a useful scaffold from which to drive cell invasion of apicomplexans. How this complex motor came to interact with the IMC scaffold may become apparent as we learn more about the early apicomplexan parasites and their move toward intracellular parasitism.

Many functional questions about the IMC in different stages of parasite development remain open. These include how IMC architecture at molecular resolution differs between stages, what the stage specificity of proteomes is and whether sub-compartmentalization and regulation of IMC assembly and disassembly is different in each stage. Another open question is how the different subcompartments of the IMC switch functions depending on their requirements. While some subcompartments and protein complexes, such as the basal complex and glideosome, have been partially characterized across different stages of the life cycle, such detailed studies have not yet been undertaken for others. Additional intriguing structures such as the apical annuli have been described in T. gondii that appear to be embedded in the IMC (Hu et al., 2006; Beck et al., 2010; Engelberg et al., 2020). Although there is currently no experimental evidence for the presence of such a structure in Plasmodium spp., a homolog of an apical annuli protein has been identified in the genome of P. falciparum that might serve as an “IMC pore” (Engelberg et al., 2020).

Another missing link is between the formation of the IMC and nuclear division. During mitosis, there appears to be a switch from local control of asynchronous rounds of nuclear division to global control. This final, global round of nuclear division occurs in parallel to IMC formation as well as with other processes of daughter cell formation. The molecular drivers of this process remain to be determined. In T. gondii, the bipartite centrosome acts as a signalling hub and coordinates the separation of nuclear division and daughter cell formation (Suvorova et al., 2015). However, although it can be speculated that a similar mechanism is likely to exist in P. falciparum, it has yet to be demonstrated.

A key question for future study is how the IMC’s large quantity of lipid and protein gets recycled or remade in each stage of the lifecycle. Other than a few hints from electron micrographs showing pieces of membranes below the PM in young rings (Riglar et al., 2013) or the apparent expulsion of membrane in hepatocytes (Jayabalasingham et al., 2010), neither of which have been confirmed to be of IMC origin, we have no clear understanding of what happens to the IMC after it is no longer needed at different stages of Plasmodium spp. development. A few different hypotheses could be imagined, including the IMC merging with the PM after selective proteolysis of IMC proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, bulk degradation by macroautophagy or bulk expulsion of the whole organelle. Degradation followed by de novo biogenesis in each stage is energy intensive, making it tempting to imagine a mechanism where the lipids and proteins are recycled. However, whether and how the IMC double membrane and protein is recycled or synthesized across different stages of malaria parasite development, often within a very short time-frame (minutes), is another mystery of this versatile organelle that remains to be elucidated.

Finally, with recent advances in techniques, particularly of imaging methods, we expect that answering the questions outlined above is already or will soon become feasible. As the IMC lies so closely below the PM (~20–30 nm) and its two membranes are extremely close together (~10 nm), few tools have high enough resolution to distinguish the three membranes. Although data from FIB-SEM of plastic embedded samples has not yet reached the resolution required to clearly resolve the IMC in published data, this technique has huge potential for providing 3D overviews of cell morphology (Rudlaff et al., 2020). To obtain more detailed information and easily resolve the three membranes, cryo electron tomography of FIB-milled samples will be necessary. Although EM techniques provide the spatial resolution needed, they only give a snapshot in time. The processes that we have described here are dynamic and vary in their speed. They therefore also need to be studied with tools which provide superior spatial and temporal resolution over, e.g., the period of IMC assembly, motile function and disassembly. The implementation of novel imaging techniques into the malaria field, such as lattice light sheet microscopy, is promising and has the potential to provide high-resolution, temporal insights into the dynamic IMC.

Author Contributions

All authors wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Human Frontier Science Program LT000024/2020-L (JF), Hospital Research Foundation Fellowship (DW), Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (BL), DFG BA5213/3-1 (JW), DAAD/Universities Australia joint research co-operation scheme (T-WG, DW, BL, and DH), and a CSSB Seed Grant (KIF-2019/002).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer RT declared providing some of the pictures used in this review article, and confirms the absence of any other collaboration with the authors to the handling editor.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Volker Heussler, Rebecca Stanway-Limenitakis, Lea Hofer, Maya Kono, and Rita Tewari for contributing to Figure 1B. Figure 1A was made using BioRender (BioRender.com).

References

Akaki M., Dvorak J. A. (2005). A chemotactic response facilitates mosquito salivary gland infection by malaria sporozoites. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 3211–3218. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01756

Akinosoglou K. A., Bushell E. S. C., Ukegbu C. V., Schlegelmilch T., Cho J. S., Redmond S., et al. (2015). Characterization of Plasmodium developmental transcriptomes in Anopheles gambiae midgut reveals novel regulators of malaria transmission. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 254–268. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12363

Alavi Y., Arai M., Mendoza J., Tufet-Bayona M., Sinha R., Fowler K., et al. (2003). The dynamics of interactions between Plasmodium and the mosquito: A study of the infectivity of Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium gallinaceum, and their transmission by Anopheles stephensi, Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti. Int. J. Parasitol. 33, 933–943. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00112-7

Al-Khattaf F. S., Tremp A. Z., Dessens J. T. (2015). Plasmodium alveolins possess distinct but structurally and functionally related multi-repeat domains. Parasitol. Res. 114, 631–639. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4226-9

Al-Khattaf F. S., Tremp A. Z., El-Houderi A., Dessens J. T. (2017). The Plasmodium alveolin IMC1a is stabilised by its terminal cysteine motifs and facilitates sporozoite morphogenesis and infectivity in a dose-dependent manner. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 211, 48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.09.004

Amino R., Thiberge S., Martin B., Celli S., Shorte S., Frischknecht F., et al. (2006). Quantitative imaging of Plasmodium transmission from mosquito to mammal. Nat. Med. 12, 220–224. doi: 10.1038/nm1350

Amlabu E., Ilani P., Opoku G., Nyarko P. B., Quansah E., Thiam L. G., et al. (2020). Molecular Characterization and Immuno-Reactivity Patterns of a Novel Plasmodium falciparum Armadillo-Type Repeat Protein, PfATRP. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 114. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00114

Aurrecoechea C., Brestelli J., Brunk B. P., Dommer J., Fischer S., Gajria B., et al. (2009). PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D539–D543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814

Baer K., Klotz C., Kappe S. H. I., Schnieder T., Frevert U. (2007). Release of hepatic Plasmodium yoelii merozoites into the pulmonary microvasculature. PloS Pathog. 3, 1651–1668. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030171

Bane K. S., Lepper S., Kehrer J., Sattler J. M., Singer M., Reinig M., et al. (2016). The Actin Filament-Binding Protein Coronin Regulates Motility in Plasmodium Sporozoites. PloS Pathog. 12, e1005710. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005710

Bannister L. H., Hopkins J. M., Fowler R. E., Krishna S., Mitchell G. H. (2000). A brief illustrated guide to the ultrastructure of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages. Parasitol. Today 16, 427–433. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01755-5

Baptista C. G., Lis A., Deng B., Gas-Pascual E., Dittmar A., Sigurdson W., et al. (2019). Toxoplasma F-box protein 1 is required for daughter cell scaffold function during parasite replication. PloS Pathog. 15, e1007946. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007946

Baum J., Richard D., Healer J., Rug M., Krnajski Z., Gilberger T. W., et al. (2006). A conserved molecular motor drives cell invasion and gliding motility across malaria life cycle stages and other apicomplexan parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5197–5208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509807200

Beck J. R., Rodriguez-Fernandez I. A., de Leon J. C., Huynh M. H., Carruthers V. B., Morrissette N. S., et al. (2010). A novel family of Toxoplasma IMC proteins displays a hierarchical organization and functions in coordinating parasite division. PloS Pathog. 6, e1001094. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001094

Beck J. R., Fung C., Straub K. W., Coppens I., Vashisht A. A., Wohlschlegel J. A., et al. (2013). A Toxoplasma Palmitoyl Acyl Transferase and the Palmitoylated Armadillo Repeat Protein TgARO Govern Apical Rhoptry Tethering and Reveal a Critical Role for the Rhoptries in Host Cell Invasion but Not Egress. PloS Pathog. 9, e1003162. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003162

Bennink S., Kiesow M. J., Pradel G. (2016). The development of malaria parasites in the mosquito midgut. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 905–918. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12604

Bergman L. W., Kaiser K., Fujioka H., Coppens I., Daly T. M., Fox S., et al. (2003). Myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP) localizes to the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium sporozoites. J. Cell Sci. 116, 39–49. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00194

Bertiaux E., Balestra A., Bournonville L., Brochet M., Guichard P., Hamel V. (2020). Expansion Microscopy provides new insights into the cytoskeleton of malaria parasites including the conservation of a conoid. bioRxiv 1–33. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.08.192328

Birnbaum J., Flemming S., Reichard N., Soares A. B., Mesén-Ramírez P., Jonscher E., et al. (2017). A genetic system to study Plasmodium falciparum protein function. Nat. Methods 14, 450–456. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4223

Blake T. C. A., Haase S., Baum J. (2020). Actomyosin forces and the energetics of red blood cell invasion by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. PloS Pathog. 16, e1009007. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009007

Bosch J., Turley S., Daly T. M., Bogh S. M., Villasmil M. L., Roach C., et al. (2006). Structure of the MTIP-MyoA complex, a key component of the malaria parasite invasion motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 4852–4857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510907103

Bosch J., Turley S., Roach C. M., Daly T. M., Bergman L. W., Hol W. G. J. (2007). The Closed MTIP-Myosin A-Tail Complex from the Malaria Parasite Invasion Machinery. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.016

Bosch J., Paige M. H., Vaidya A. B., Bergman L. W., Hol W. G. J. (2012). Crystal structure of GAP50, the anchor of the invasion machinery in the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Struct. Biol. 178, 61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.02.009

Boucher L. E., Bosch J. (2014). Structure of Toxoplasma gondii fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 1186–1192. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X14017087

Bruce M. C., Carter R. N., Nakamura K., ichiro, Aikawa M., Carter R. (1994). Cellular location and temporal expression of the Plasmodium falciparum sexual stage antigen Pfs16. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 65, 11–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90111-2

Bullen H. E., Tonkin C. J., O’Donnell R. A., Tham W. H., Papenfuss A. T., Gould S., et al. (2009). A novel family of apicomplexan glideosome-associated proteins with an inner membrane-anchoring role. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25353–25363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036772

Campelo Morillo R., Tong X., Xie W., Lenz T., Batugedara G., Tabassum N., et al. (2020). Homeodomain protein 1 is an essential regulator of gene expression during sexual differentiation of malaria parasites. BioRxiv 2, 2020.10.26.352583. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.26.352583

Carey A. F., Singer M., Bargieri D., Thiberge S., Frischknecht F., Ménard R., et al. (2014). Calcium dynamics of Plasmodium berghei sporozoite motility. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 768–783. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12289

Cavalier-Smith T. (1993). Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla. Microbiol. Rev. 57, 953–994. doi: 10.1128/MR.57.4.953-994.1993

Chen A. L., Kim E. W., Toh J. Y., Vashisht A. A., Rashoff A. Q., Van C., et al. (2015). Novel components of the toxoplasma inner membrane complex revealed by BioID. MBio 6, e02357–e02314. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02357-14

Coghlan M. P., Tremp A. Z., Saeed S., Vaughan C. K., Dessens J. T. (2019). Distinct Functional Contributions by the Conserved Domains of the Malaria Parasite Alveolin IMC1h. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 266. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00266

De Niz M., Meibalan E., Mejia P., Ma S., Brancucci N. M. B., Agop-Nersesian C., et al. (2018). Plasmodium gametocytes display homing and vascular transmigration in the host bone marrow. Sci. Adv. 4, 1–15. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat3775

Dearnley M. K., Yeoman J., Hanssen E., Kenny S., Turnbull L., Whitchurch C. B., et al. (2012). Origin, composition, organization and function of the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2053–2063. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099002

Dixon M. W., Dearnley M. K., Hanssen E., Gilberger T., Tilley L. (2012). Shape-shifting gametocytes: how and why does P. falciparum go banana-shaped? Trends Parasitol. 28, 471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.007

Dondorp A. M., Nosten F., Yi P., Das D., Phyo A. P., Tarning J., et al. (2009). Artemisinin Resistance in. Drug Ther. (NY). 361, 455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859

Ejigiri I., Ragheb D. R. T., Pino P., Coppi A., Bennett B. L., Soldati-Favre D., et al. (2012). Shedding of TRAP by a rhomboid protease from the malaria sporozoite surface is essential for gliding motility and sporozoite infectivity. PloS Pathog. 8, e1002725. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002725

El-Haddad H., Przyborski J. M., Kraft L. G. K., McFadden G. I., Waller R. F., Gould S. B. (2013). Characterization of TtALV2, an essential charged repeat motif protein of the Tetrahymena thermophila membrane skeleton. Eukaryot. Cell 12, 932–940. doi: 10.1128/EC.00050-13

Engelberg K., Ivey F. D., Lin A., Kono M., Lorestani A., Faugno-Fusci D., et al. (2016). A MORN1-associated HAD phosphatase in the basal complex is essential for Toxoplasma gondii daughter budding. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1153–1171. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12574

Engelberg K., Chen C. T., Bechtel T., Sánchez Guzmán V., Drozda A. A., Chavan S., et al. (2020). The apical annuli of Toxoplasma gondii are composed of coiled-coil and signalling proteins embedded in the inner membrane complex sutures. Cell. Microbiol. 22, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13112

Ferguson D. J. P., Sahoo N., Pinches R. A., Bumstead J. M., Tomley F. M., Gubbels M. J. (2008). MORN1 has a conserved role in asexual and sexual development across the Apicomplexa. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 698–711. doi: 10.1128/EC.00021-08

Fivelman Q. L., Mcrobert L., Sharp S., Taylor C. J., Saeed M., Swales C. A., et al. (2007). Improved synchronous production of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in vitro. I 154, 119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.04.008

Frénal K., Polonais V., Marq J. B., Stratmann R., Limenitakis J., Soldati-Favre D. (2010). Functional dissection of the apicomplexan glideosome molecular architecture. Cell Host Microbe 8, 343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.09.002

Frénal K., Tay C. L., Mueller C., Bushell E. S., Jia Y., Graindorge A., et al. (2013). Global analysis of apicomplexan protein S-acyl transferases reveals an enzyme essential for invasion. Traffic 14, 895–911. doi: 10.1111/tra.12081

Frénal K., Jacot D., Hammoudi P. M., Graindorge A., MacO B., Soldati-Favre D. (2017). Myosin-dependent cell-cell communication controls synchronicity of division in acute and chronic stages of Toxoplasma gondii. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–18. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15710

Frischknecht F., Matuschewski K. (2017). Plasmodium sporozoite biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025478

Fung C., Beck J. R., Robertson S. D., Gubbels M.-J., Bradley P. J. (2012). Toxoplasma ISP4 is a central IMC sub-compartment protein whose localization depends on palmitoylation but not myristoylation. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 184, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.05.002

Gantt S., Persson C., Rose K., Birkett A. J., Abagyan R., Nussenzweig V. (2000). Antibodies against thrombospondin-related anonymous protein do not inhibit Plasmodium sporozoite infectivity in vivo. Infect. Immun. 68, 3667–3673. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3667-3673.2000

Gao H., Yang Z., Wang X., Qian P., Hong R., Chen X., et al. (2018). ISP1-Anchored Polarization of GCβ/CDC50A Complex Initiates Malaria Ookinete Gliding Motility. Curr. Biol. 28, 2763–2776.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.069

Gaskins E., Gilk S., DeVore N., Mann T., Ward G., Beckers C. (2004). Identification of the membrane receptor of a class XIV myosin in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Biol. 165, 383–393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311137

Gómez-Díaz E., Yerbanga R. S., Lefèvre T., Cohuet A., Rowley M. J., Ouedraogo J. B., et al. (2017). Epigenetic regulation of Plasmodium falciparum clonally variant gene expression during development in Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–17. doi: 10.1038/srep40655

Gould S. B., Tham W.-H., Cowman A. F., McFadden G. I., Waller R. F. (2008). Alveolins, a new family of cortical proteins that define the protist infrakingdom Alveolata. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1219–1230. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn070

Green J. L., Martin S. R., Fielden J., Ksagoni A., Grainger M., Yim Lim B. Y. S., et al. (2006). The MTIP-myosin A complex in blood stage malaria parasites. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.027

Green J. L., Wall R. J., Vahokoski J., Yusuf N. A., Mohd Ridzuan M. A., Stanway R. R., et al. (2017). Compositional and expression analyses of the glideosome during the Plasmodium life cycle reveal an additional myosin light chain required for maximum motility. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 17857–17875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.802769

Gunaratne R. S., Sajid M., Ling I. T., Tripathi R., Pachebat J. A., Holder A. A. (2000). Characterization of N-myristoyltransferase from plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 348, 459–463. doi: 10.1042/bj3480459

Guttery D. S., Roques M., Holder A. A., Tewari R. (2015). Commit and Transmit: Molecular Players in Plasmodium Sexual Development and Zygote Differentiation. Trends Parasitol. 31, 676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.08.002

Hanssen E., Dekiwadia C., Riglar D. T., Rug M., Lemgruber L., Cowman A. F., et al. (2013). Electron tomography of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites reveals core cellular events that underpin erythrocyte invasion. Cell. Microbiol. 15, 1457–1472. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12132

Harding C. R., Meissner M. (2014). The inner membrane complex through development of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 632–641. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12285

Herm-Götz A., Weiss S., Stratmann R., Fujita-Becker S., Ruff C., Meyhöfer E., et al. (2002). Toxoplasma gondii myosin A and its light chain: A fast, single-headed, plus-end-directed motor. EMBO J. 21, 2149–2158. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2149

Hopp C. S., Balaban A. E., Bushell E. S. C., Billker O., Rayner J. C., Sinnis P. (2016). Palmitoyl transferases have critical roles in the development of mosquito and liver stages of Plasmodium. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1625–1641. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12601

Hu K., Johnson J., Florens L., Fraunholz M., Suravajjala S., DiLullo C., et al. (2006). Cytoskeletal components of an invasion machine - The apical complex of Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2, 0121–0138. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020013

Hu G., Cabrera A., Kono M., Mok S., Chaal B. K., Haase S., et al. (2010). Transcriptional profiling of growth perturbations of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 91–98. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1597

Hu K. (2008). Organizational changes of the daughter basal complex during the parasite replication of Toxoplasma gondii. PloS Pathog. 4, e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040010

Imwong M., Suwannasin K., Kunasol C., Sutawong K., Mayxay M., Rekol H., et al. (2017). The spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the Greater Mekong subregion: a molecular epidemiology observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 491–497. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30048-8

Jayabalasingham B., Bano N., Coppens I. (2010). Metamorphosis of the malaria parasite in the liver is associated with organelle clearance. Cell Res. 20, 1043–1059. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.88

Joice R., Nilsson S. K., Montgomery J., Dankwa S., Morahan B., Seydel K. B., et al. (2014). Plasmodium falciparum transmission stages accumulate in the human bone marrow. Genes Brain Behav. 6, 1–16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008882

Kaidoh T., Nath J., Okoye V., Aikawa M. (1993). Novel Structure in the pellicle complex of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. J.Euk. Microbiol. 40, 269–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04916.x

Kaiser K., Camargo N., Kappe S. H. I. (2003). Transformation of sporozoites into early exoerythrocytic malaria parasites does not require host cells. J. Exp. Med. 197, 1045–1050. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022100

Kaneko I., Iwanaga S., Kato T., Kobayashi I., Yuda M. (2015). Genome-Wide Identification of the Target Genes of AP2-O, a Plasmodium AP2-Family Transcription Factor. PloS Pathog. 11, 1004905. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004905

Keeley A., Soldati D. (2004). The glideosome: A molecular machine powering motility and host-cell invasion by Apicomplexa. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.08.002

Khater E. I., Sinden R. E., Dessens J. T. (2004). A malaria membrane skeletal protein is essential for normal morphogenesis, motility, and infectivity of sporozoites. J. Cell Biol. 167, 425–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406068

Kissmehl R., Huber S., Kottwitz B., Hauser K., Plattner H. (1998). Subplasmalemmal Ca-stores in Paramecium tetraurelia. Identification and characterisation of a sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum-like Ca2+-ATPase by phosphoenzyme intermediate formation and its inhibition by caffeine. Cell Calcium 24, 193–203. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4160(98)90128-2

Kono M., Herrmann S., Loughran N. B., Cabrera A., Engelberg K., Lehmann C., et al. (2012). Evolution and architecture of the inner membrane complex in asexual and sexual stages of the malaria parasite. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 2113–2132. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss081

Kono M., Heincke D., Wilcke L., Wong T. W. Y., Bruns C., Herrmann S., et al. (2016). Pellicle formation in the malaria parasite. J. Cell Sci. 129, 673–680. doi: 10.1242/jcs.181230

Kudryashev M., Lepper S., Stanway R., Bohn S., Baumeister W., Cyrklaff M., et al. (2010). Positioning of large organelles by a membrane- associated cytoskeleton in Plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 362–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01399.x

Kudryashev M., Münter S., Lemgruber L., Montagna G., Stahlberg H., Matuschewski K., et al. (2012). Structural basis for chirality and directional motility of Plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 1757–1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01836.x

Kumar V., Behl A., Kapoor P., Nayak B., Singh G., Singh A. P., et al. (2019). Inner membrane complex 1l protein of Plasmodium falciparum links membrane lipids with cytoskeletal element ‘actin’ and its associated motor ‘myosin.’ Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.239

Ladenburger E.-M., Sehring I. M., Korn I., Plattner H. (2009). Novel Types of Ca2+ Release Channels Participate in the Secretory Cycle of Paramecium Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 3605–3622. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01592-08

Länge S., Klauke N., Plattner H. (1995). Subplasmalemmal Ca2+ stores of probable relevance for exocytosis in Paramecium. Alveolar sacs share some but not all characteristics with sarcoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium 17, 335–344. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90107-8

Lee R. S., Waters A. P., Brewer J. M. (2018). A cryptic cycle in haematopoietic niches promotes initiation of malaria transmission and evasion of chemotherapy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1689. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04108-9

Lentini G., Kong-Hap M., El Hajj H., Francia M., Claudet C., Striepen B., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of ToxoplasmaSIP, a conserved apicomplexan cytoskeleton protein involved in maintaining the shape, motility and virulence of the parasite. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 62–78. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12337

López-Barragán M. J., Lemieux J., Quiñones M., Williamson K. C., Molina-Cruz A., Cui K., et al. (2011). Directional gene expression and antisense transcripts in sexual and asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Genomics 12, 587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-587

Lorestani A., Sheiner L., Yang K., Robertson S. D., Sahoo N., Brooks C. F., et al. (2010). A Toxoplasma MORN1 null mutant undergoes repeated divisions but is defective in basal assembly, apicoplast division and cytokinesis. PloS One 5, e12303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012302

Lorestani A., Ivey F. D., Thirugnanam S., Busby M. A., Marth G. T., Cheeseman I. M., et al. (2012). Targeted proteomic dissection of Toxoplasma cytoskeleton sub-compartments using MORN1. Cytoskeleton 69, 1069–1085. doi: 10.1002/cm.21077

Mann T., Beckers C. (2001). Characterization of the subpellicular network, a filamentous.pdf. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 115, 257–268. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00289-4

Meis J. F., Verhaven J. P., Jap P. H., Meuwissen J. H. (1985). Fine structure of exoerythrocytic merozoite formation of Plasmodium bergei in rat liver. J. Protozool. 32 (4), 694–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03104.x

Meszoely C., Erbe E., Steere R., Tropere J., Beaudoin R. L. (1987). Plasmodium falciparum: Freeze-Facture of the Gametocyte Pellicular Complex. Exp. Parasitol. 64, 300–309. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(87)90040-3

Morrissette N. S., Sibley L. D. (2002). Cytoskeleton of Apicomplexan Parasites. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 21–38. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.21-38.2002

Moussaoui D., Robblee J. P., Auguin D., Krementsova E. B., Haase S., Thomas C., et al. (2020). Full-length Plasmodium falciparum myosin A and essential light chain PfELC structures provide new anti-malarial targets. Elife 9, e60581. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60581

Münter S., Sabass B., Selhuber-Unkel C., Kudryashev M., Hegge S., Engel U., et al. (2009). Plasmodium Sporozoite Motility Is Modulated by the Turnover of Discrete Adhesion Sites. Cell Host Microbe 6, 551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.007

Ngotho P., Soares A. B., Hentzschel F., Achcar F., Bertuccini L., Marti M. (2019). Revisiting gametocyte biology in malaria parasites. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 43, 401–414. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz010

Obaldia N., Meibalan E., Sa J. M., Ma S., Clark M. A., Mejia P., et al. (2018). Bone marrow is a major parasite reservoir in plasmodium vivax infection. MBio 9, 1–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00625-18

Opitz C., Soldati D. (2002). “The glideosome”: A dynamic complex powering gliding motion and host cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 597–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03056.x

Ouologuem D. T., Roos D. S. (2014). Dynamics of the Toxoplasma gondii inner membrane complex. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3320–3330. doi: 10.1242/jcs.147736

Pazicky S., Dhamotharan K., Kaszuba K., Mertens H., Gilberger T., Svergun D., et al. (2020). Structural role of essential light chains in the apicomplexan glideosome. Commun. Biol. 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01283-8

Perrin A. J., Collins C. R., Russell M. R. G., Collinson L. M., Baker D. A., Blackman M. J. (2018). The actinomyosin motor drives malaria parasite red blood cell invasion but not egress. MBio 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00905-18

Pinder J. C., Fowler R. E., Dluzewski A. R., Bannister L. H., Lavin F. M., Mitchell G. H., et al. (1998). Actomyosin motor in the merozoite of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum: Implications for red cell invasion. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1831–1839.

Poulin B., Patzewitz E.-M., Brady D., Silvie O., Wright M. H., Ferguson D. J. P., et al. (2013). Unique apicomplexan IMC sub-compartment proteins are early markers for apical polarity in the malaria parasite. Biol. Open 2, 1160–1170. doi: 10.1242/bio.20136163

Ridzuan M.@. A. M., Moon R. W., Knuepfer E., Black S., Holder A. A., Green J. L. (2012). Subcellular location, phosphorylation and assembly into the motor complex of GAP45 during Plasmodium falciparum schizont development. PloS One 7, e33845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033845

Riglar D. T., Rogers K. L., Hanssen E., Turnbull L., Bullen H. E., Charnaud S. C., et al. (2013). Spatial association with PTEX complexes defines regions for effector export into Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Nat. Commun. 4, 1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2449

Robert-Paganin J., Robblee J. P., Auguin D., Blake T. C. A., Bookwalter C. S., Krementsova E. B., et al. (2019). Plasmodium myosin A drives parasite invasion by an atypical force generating mechanism. Nat. Commun. 10, 3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11120-0

Rogerson S. J., Beeson J. G., Laman M., Poespoprodjo J. R., William T., Simpson J. A., et al. (2020). Identifying and combating the impacts of COVID-19 on malaria. BMC Med. 18, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01710-x

Rudlaff R. M., Kraemer S., Streva V. A., Dvorin J. D. (2019). An essential contractile ring protein controls cell division in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10214-z

Rudlaff R. M., Kraemer S., Marshman J., Dvorin J. D. (2020). Three-dimensional ultrastructure of Plasmodium falciparum throughout cytokinesis. PloS Pathog. 16, 1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008587

Rupp I., Sologub L., Williamson K. C., Scheuermayer M., Reininger L., Doerig C., et al. (2011). Malaria parasites form filamentous cell-to-cell connections during reproduction in the mosquito midgut. Cell Res. 21, 683–696. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.176

Saini E., Zeeshan M., Brady D., Pandey R., Kaiser G., Koreny L., et al. (2017). Photosensitized INA-Labelled protein 1 (PhIL1) is novel component of the inner membrane complex and is required for Plasmodium parasite development. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15781-z

Santos J. M., Kehrer J., Franke-Fayard B., Frischknecht F., Janse C. J., Mair G. R. (2015). The Plasmodium palmitoyl-S-acyl-transferase DHHC2 is essential for ookinete morphogenesis and malaria transmission. Sci. Rep. 5, 16034. doi: 10.1038/srep16034

Schneider M. P., Liu B., Glock P., Suttie A., McHugh E., et al. (2017). Disrupting assembly of the inner membrane complex blocks Plasmodium falciparum sexual stage development. PloS Pathog. 13, 1–30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006659

Schrevel J., Asfaux-Foucher G., Hopkins J. M., Robert V., Bourgouin C., Prensier G., et al. (2008). Vesicle trafficking during sporozoite development in Plasmodium berghei: Ultrastructural evidence for a novel trafficking mechanism. Parasitology 135, 1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003629

Sherrard-Smith E., Hogan A. B., Hamlet A., Watson O. J., Whittaker C., Winskill P., et al. (2020). The potential public health consequences of COVID-19 on malaria in Africa. Nat. Med. 26, 1411–1416. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1025-y

Siciliano G., Costa G., Suárez-Cortés P., Valleriani A., Alano P., Levashina E. A. (2020). Critical Steps of Plasmodium falciparum Ookinete Maturation. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00269

Siden-Kiamos I., Ganter M., Kunze A., Hliscs M., Steinbüchel M., Mendoza J., et al. (2011). Stage-specific depletion of myosin A supports an essential role in motility of malarial ookinetes. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1996–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01686.x

Sinden R. E., Matuschewski K. (2005). “The Sporozoite” in: Moleclular Approaches to Malaria. Ed. I. W. Sherman (ASM Press). doi: 10.1128/9781555817558

Sinden R. E. (1981). Sexual development of malarial parasites in their mosquito vectors. Trans. R. Soc Trop. Med. Hyg. 75, 171–172. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90058-4

Smalley M. E., Sinden R. E. (1977). Plasmodium falcparum gametocytes: their longevity and infectivity. Parasitology 74, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000047478

Sologub L., Kuehn A., Kern S., Przyborski J., Schillig R., Pradel G. (2011). Malaria proteases mediate inside-out egress of gametocytes from red blood cells following parasite transmission to the mosquito. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 897–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01588.x

Stanway R. R., Mueller N., Zobiak B., Graewe S., Froehlke U., Zessin P. J. M., et al. (2011). Organelle segregation into Plasmodium liver stage merozoites. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1768–1782. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01657.x

Stering C., Aikawa M. (1973). A Comperative Study of Gametocyte Ultrastructure in Avian Haemosporidia. J. Protozool. 20, 81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1973.tb06008.x

Stone W. J. R., Eldering M., Van Gemert G. J., Lanke K. H. W., Grignard L., Van De Vegte-Bolmer M. G., et al. (2013). The relevance and applicability of oocyst prevalence as a read-out for mosquito feeding assays. Sci. Rep. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep03418

Sultan A. A., Thathy V., Frevert U., Robson K. J. H., Crisanti A., Nussenzweig V., et al. (1997). TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of Plasmodium sporozoites. Cell 90, 511–522. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80511-5

Suvorova E. S., Francia M., Striepen B., White M. W. (2015). A Novel Bipartite Centrosome Coordinates the Apicomplexan Cell Cycle. PloS Biol. 13, 1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002093

Tay C. L., Jones M. L., Hodson N., Theron M., Choudhary J. S., Rayner J. C. (2016). Study of Plasmodium falciparum DHHC palmitoyl transferases identifies a role for PfDHHC9 in gametocytogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1596–1610. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12599

Terzakis J. A., Sprinz H., Ward R. A. (1967). The transformation of the Plasmodium gallinaceum oocyst in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J. Cell Biol. 34, 311–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.1.311

Tonkin C. J., Van Dooren G. G., Spurck T. P., Struck N. S., Good R. T., Handman E., et al. (2004). Localization of organellar proteins in Plasmodium falciparum using a novel set of transfection vectors and a new immunofluorescence fixation method. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 137, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.05.009

Tremp A. Z., Khater E. I., Dessens J. T. (2008). IMC1b is a putative membrane skeleton protein involved in cell shape, mechanical strength, motility, and infectivity of malaria ookinetes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27604–27611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801302200

Tremp A. Z., Carter V., Saeed S., Dessens J. T. (2013). Morphogenesis of Plasmodium zoites is uncoupled from tensile strength. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 552–564. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12297

Tremp A. Z., Al-Khattaf F. S., Dessens J. T. (2014). Distinct temporal recruitment of Plasmodium alveolins to the subpellicular network. Parasitol. Res. 113, 4177–4188. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4093-4

Tremp A. Z., Al-Khattaf F. S., Dessens J. T. (2017). Palmitoylation of Plasmodium alveolins promotes cytoskeletal function. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 213, 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2017.02.003

Vanderberg J. P. (1974). Studies on the Motility of Plasmodium Sporozoites. J. Protozool. 21, 527–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03693.x

Vaughan A. M., Ploss A., Kappe S. H. I., Vaughan A. M., Mikolajczak S. A., Wilson E. M., et al. (2012). Complete Plasmodium falciparum liver-stage development in liver-chimeric mice. J. Clin. Investig. 122, 3618–3628. doi: 10.1172/JCI62684

Volkmann K., Pfander C., Burstroem C., Ahras M., Goulding D., Rayner J. C., et al. (2012). The alveolin IMC1h is required for normal ookinete and sporozoite motility behaviour and host colonisation in plasmodium berghei. PloS One 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041409

Wang X., Qian P., Cui H., Yao L., Yuan J. (2020). A protein palmitoylation cascade regulates microtubule cytoskeleton integrity in Plasmodium. EMBO J. 39 (13), 1–22. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019104168

Webb S. E., Fowler R. E., O’shaughnessy C., Pinder J. C., Dluzewski A. R., Gratzer W. B., et al. (1996). Contractile protein system in the asexual stages of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 112, 451–457. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000076915

Wetzel J., Herrmann S., Swapna L. S., Prusty D., Peter A. T. J., Kono M., et al. (2015). The Role of Palmitoylation for Protein Recruitment to the Inner Membrane Complex of the Malaria Parasite *. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 1712–1728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598094

Wolters J. (1991). The troublesome parasites - molecular and morphological evidence that Apicomplexa belong to the dinoflagellate-ciliate clade. BioSystems 25, 75–83. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(91)90014-C

Woodrow C. J., White N. J. (2017). The clinical impact of artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia and the potential for future spread. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 34–48. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw037

Yeoman J. A., Hanssen E., Maier A. G., Klonis N., Maco B., Baum J., et al. (2011). Tracking Glideosome-associated protein 50 reveals the development and organization of the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot. Cell 10, 556–564. doi: 10.1128/EC.00244-10

Keywords: malaria, Plasmodium, Apicomplexa, Alveolata, inner membrane complex, membrane dynamics

Citation: Ferreira JL, Heincke D, Wichers JS, Liffner B, Wilson DW and Gilberger T-W (2021) The Dynamic Roles of the Inner Membrane Complex in the Multiple Stages of the Malaria Parasite. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:611801. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.611801

Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020;

Published: 08 January 2021.

Edited by:

Maria E. Francia, Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, UruguayReviewed by:

Marc-Jan Gubbels, Boston College, United StatesRita Tewari, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Clare Harding, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Ferreira, Heincke, Wichers, Liffner, Wilson and Gilberger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tim-Wolf Gilberger, Z2lsYmVyZ2VyQGJuaXRtLmRl

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Josie Liane Ferreira

Josie Liane Ferreira Dorothee Heincke

Dorothee Heincke Jan Stephan Wichers

Jan Stephan Wichers Benjamin Liffner

Benjamin Liffner Danny W. Wilson

Danny W. Wilson Tim-Wolf Gilberger

Tim-Wolf Gilberger