94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol., 12 March 2025

Sec. Molecular and Cellular Pathology

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2025.1523489

Qingzhi Ran1†

Qingzhi Ran1† Aoshuang Li2†

Aoshuang Li2† Bo Yao1

Bo Yao1 Chunrong Xiang1

Chunrong Xiang1 Chunyi Qu3

Chunyi Qu3 Yongkang Zhang4,5*

Yongkang Zhang4,5* Xuanhui He1*

Xuanhui He1* Hengwen Chen1*

Hengwen Chen1*Rapid activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) induces phosphorylation of mitochondrial-associated proteins, a process by which phosphate groups are added to regulate mitochondrial function, thereby modulating mitochondrial energy metabolism, triggering an acute metabolic response, and sustaining metabolic adaptation through transcriptional regulation. AMPK directly phosphorylates folliculin interacting protein 1 (FNIP1), leading to the nuclear translocation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) in response to mitochondrial functions. While mitochondrial function is tightly linked to finely-tuned energy-sensing mobility, FNIP1 plays critical roles in glucose transport and sensing, mitochondrial autophagy, cellular stress response, and muscle fiber contraction. Consequently, FNIP1 emerges as a promising novel target for addressing aberrant mitochondrial energy metabolism. Recent evidence indicates that FNIP1 is implicated in mitochondrial biology through various pathways, including AMPK, mTOR, and ubiquitination, which regulate mitochondrial autophagy, oxidative stress responses, and skeletal muscle contraction. Nonetheless, there is a dearth of literature discussing the physiological mechanism of action of FNIP1 as a novel therapeutic target. This review outlines how FNIP1 regulates metabolic-related signaling pathways and enzyme activities, such as modulating mitochondrial energy metabolism, catalytic activity of metabolic enzymes, and the homeostasis of metabolic products, thereby controlling cellular function and fate in different contexts. Our focus will be on elucidating how these metabolite-mediated signaling pathways regulate physiological processes and inflammatory diseases.

The ability to adapt to chronic nutritional deficiencies is a fundamental characteristic of all organisms’ survival. Eukaryotic cells contain highly conserved signaling pathways, which are rapidly activated when intracellular ATP levels decrease, most commonly due to a reduction in oxygen or glucose concentration that disrupts mitochondrial ATP function or in response to mitochondrial toxins or metabolic products that directly interfere with oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytochrome C (Carlisle et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2020). Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is fully phosphorylated and becomes a substrate in OXPHOS inhibition, capable of regulating lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, mitochondrial autophagy, and mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling (Puertollano et al., 2018; Roczniak-Ferguson et al., 2012; Settembre et al., 2012; Vega-Rubin-de-Celis et al., 2017). Prolonged ATP energy stress alters transcriptional changes in gene expression programs controlling various metabolic processes (Young et al., 2016). Transcription factor EB (TFEB) and related TFE3 are activated in response to nutritional deprivation and energy stress, both inhibited by mTORC1 signaling and activated by AMPK signalin (Petit et al., 2013; Tsun et al., 2013). mTORC1 directly phosphorylates TFEB at Ser 122, Ser 142, and Ser 211, sequestration in the cytoplasm. Amino acids (AA) promote the generation of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) through the folliculin (FLCN) and FLCN interacting protein 1 (FNIP1) complex, activating the GTPase-activating protein (GAP) complex. This complex regulates the activity of small GTPases, further modulating the function of mTORC1 and affecting its ability to phosphorylate the transcription factor TFEB. TFEB, as a key transcription factor, regulates autophagy, lysosomal function, and metabolic homeostasis, playing a critical role in cellular energy metabolism, waste clearance, and other processes (Lawrence et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2019). The FLCN-FNIP1 complex determines the GTP loading of GTPase RagC, leading to the release of TFEB and TFE3 from the lysosome and nuclear translocation away from mTORC1 (Settembre et al., 2011). The FLCN/FNIP1 complex regulates the GTP loading of the GTPase RagC, promoting its activation, which drives mTORC1 translocation to the lysosome and activates its function. Furthermore, FLCN/FNIP1 regulates the RagGTPase complex, promoting the release of transcription factors TFEB and TFE3 from the lysosome and their translocation to the nucleus, thereby relieving mTORC1’s inhibition on them and regulating the expression of autophagy and metabolic genes (Tsun et al., 2013). FLCN/FNIP1 also works in concert with AMPK to respond to changes in the cell’s energy status, regulating mTORC1 activity and subsequently influencing cellular metabolic adaptive responses, such as lipid metabolism and glucose metabolism (Puertollano et al., 2018; Roczniak-Ferguson et al., 2012; Settembre et al., 2012; Vega-Rubin-de-Celis et al., 2017). Through these mechanisms, FLCN/FNIP1 plays a crucial role in cellular metabolic homeostasis, energy balance, and stress responses, ensuring that the cell can adaptively regulate according to changes in external nutrient and energy supply (Petit et al., 2013). In the nucleus, TFEB and TFE3 simultaneously bind to the DNA binding elements known as the Coordinated Lysosomal Expression and Regulation (CLEAR) motif (Perera et al., 2019). Under physiological conditions, TFEB and TFE3 remain inactive, but during specific cellular stress, they translocate to the nucleus to promote lysosomal biogenesis and possibly induce autophagy (Collodet et al., 2019). AMPK is essential for the translocation of TFEB to the nucleus during energy stress. Nazma Malik’s 2023 article published in Science confirmed that FNIP1, as a downstream protein dependent on the AMPK signaling pathway, can dictate the translocation of TFEB and TFE3 to the nucleus, facilitating the transcription of CLEAR genes (Malik et al., 2023).

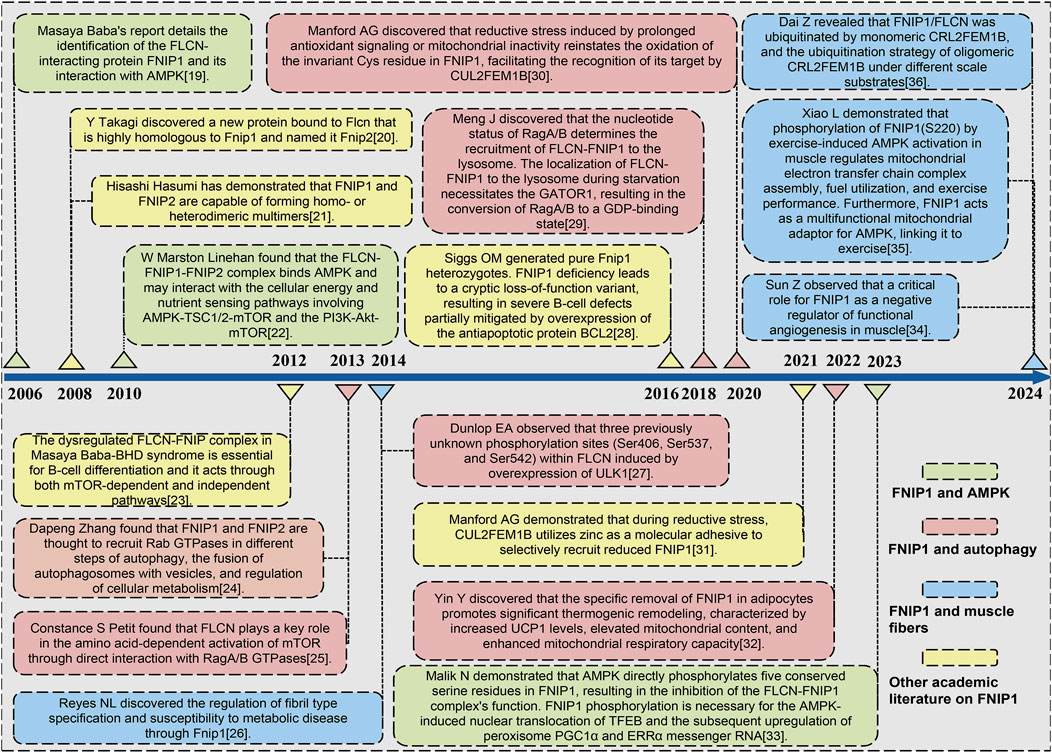

The precise mechanism through which AMPK activates the transcriptional program for mitochondrial biogenesis via FNIP1 has been elucidated. Nazma Malik’s team conducted a time-course analysis of the transcriptional response to mitochondrial OXPHOS inhibitors, revealing a temporal cascade of organelle biogenesis that is genetically dependent on AMPK (Hung et al., 2021). It has been determined that FNIP1, as a direct AMPK substrate, plays a crucial role where its phosphorylation is essential for the activation and nuclear translocation of TFEB. This, in turn, leads to the production of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma, Coactivator 1 Alpha (PGC-1α) and Estrogen-Related Receptor α (ERRα) mRNA, triggering lysosomal biogenesis responses and thus affecting mitochondrial biological processes (Cantó and Auwerx, 2009). FNIP1 acts as a direct substrate of AMPK through the AMPK signaling pathway, and is phosphorylated upon AMPK activation, thereby regulating the transcriptional activity of TFEB (Tsun et al., 2013). Upon AMPK activation, phosphorylation of FNIP1 promotes the translocation of TFEB from the lysosome to the nucleus, activating the transcription of genes related to organelle biogenesis, including Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1 Alpha (PGC-1α) and Estrogen-Related Receptor Alpha (ERRα) (Shen et al., 2019). PGC-1α, as a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, promotes mitochondrial generation and functional recovery, while ERRα regulates mitochondrial metabolic responses (Collodet et al., 2019). Through this process, FNIP1 helps cells maintain energy homeostasis and metabolic adaptation by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and functional regulation under stress conditions, thereby enhancing the cell’s ability to respond to energy depletion and oxidative stress. We have compiled a timeline of key milestone developments in mitochondrial diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and skeletal muscle disorders where Fnip1 signaling has been implicated, as shown in Figure 1 (Baba et al., 2006; Baba et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2024; Dunlop et al., 2014; Hasumi et al., 2008; Linehan, Srinivasan and Schmidt, 2010; Manford et al., 2021; Manford et al., 2020; Meng and Ferguson, 2018; Petit et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2015; Rezvan et al., 2024; Siggs et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2023; Takagi et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2012). Given the novelty and complex pathophysiological mechanisms of FNIP1, this review for the first time retrospectively summarizes the research trajectory and milestones of FNIP1, attempts to summarize the physiological mechanisms of FNIP1 in mitochondria and its pathological mechanisms in various diseases, laying the foundation for understanding the multilevel regulatory signaling pathways and mechanisms of FNIP1. This provides a reference for future development of FNIP1-targeted drug therapies for mitochondrial diseases and improving patients prognosis with reduced stress, inflammatory response, skeletal muscle damage, et.

Figure 1. Timeline of key milestones in the development of FNIP1 signaling. Abbreviations: FLCN, Folliculin; FNIP1, Folliculin Interacting Protein 1; AMPK, Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin. TSC1, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase; AKT1, AKT serine/threonine kinase 1; GATOR1, GAP activity toward Rags 1; GDP, Guanosine diphosphate; PGC1α Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ coactivator l alpha; ERRα, Estrogen Receptor alpha.

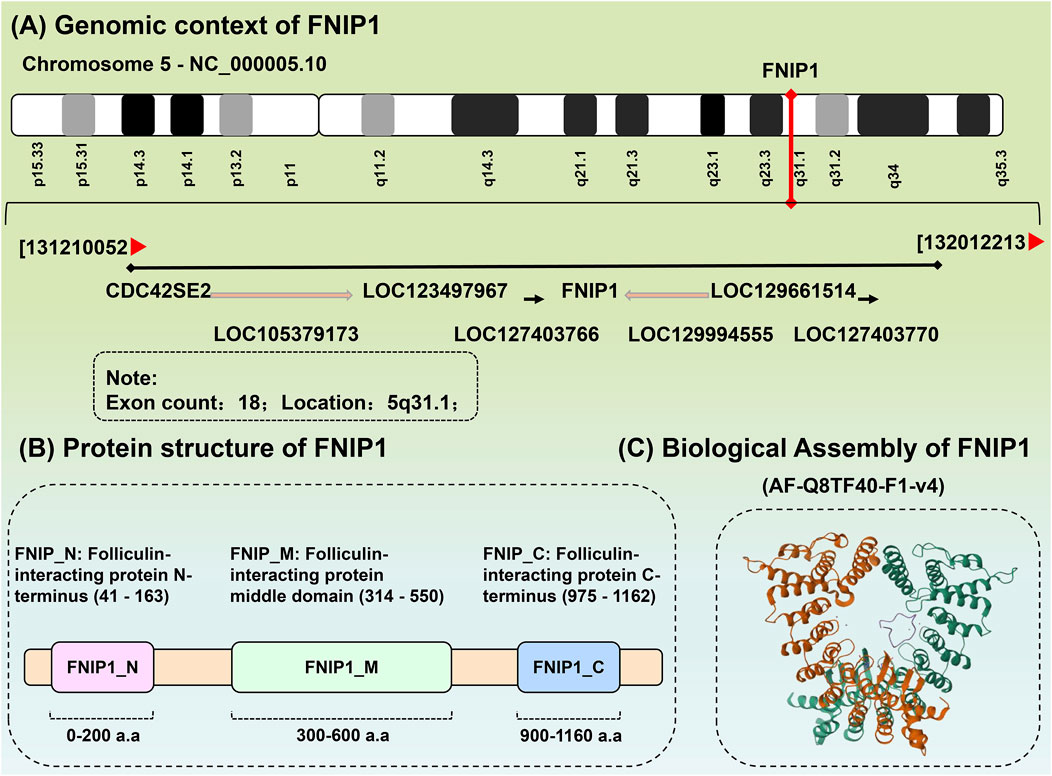

FNIP1 is ubiquitously distributed in 27 different tissues including the heart, testes, and thyroid, with RNA sequence analysis of FNIP1 across these 27 human tissues presented in Table 1. The FNIP1 gene encodes a protein that interacts with the tumor suppressor protein folliculin and AMPK, participating in the regulation of cell metabolism and nutrient sensing through the mTOR pathway (Manford et al., 2020). This gene has a closely related paralog that encodes a protein with similar binding activity. These two related proteins bind to the molecular chaperone Heat Shock Protein-90 (Hsp90) and negatively regulate its ATPase activity, promoting its interaction with folliculin. The genomic context of FNIP1 is shown in Figure 2A, in the context of Chromosome 5 - NC_000005.10. (Exon count:18; Location:5q31.1). Listing from CDC42SE2 to ACSL6-AS1. The protein structure of FNIP1 is depicted in Figure 2B (Zhang et al., 2012), FNIP_N: Folliculin-interacting protein N-terminus (41–163), FNIP_M: Folliculin-interacting protein middle domain (314–550), FNIP_C: Folliculin-interacting protein C-terminus (975–1,162). And the biological assembly of FNIP1 is illustrated in Figure 2C (Petit et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012). We used AlphaFold (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/) for homology modeling. This tool predicts the three-dimensional structure of FNIP1 by aligning it with known homologous protein structures. The identifier for FNIP1 on the AlphaFold website is AF-Q8TF40-F1-v4. Furthermore, Hisashi Hasumi identified a new FLCN-interacting protein, FNIP2, which is homologous to FNIP1 across species and has been shown to form polymers independent of FLCN expression, functioning cooperatively with FLCN. Tissue-specific expression patterns suggest potential tissue specificity in normal cellular signal transduction for FNIP1 and FNIP2. The sequence alignment of FNIP1 and FNIP2, along with key information such as the homology percentage, similarity, and differences between the isoforms, can be found in Supplementary Figure 1. The differences in amino acid sequence homology, domain differences, tissue distribution, and cellular functions between FNIP1 and FNIP2 are summarized in Table 2 (Manford et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2022).

Figure 2. Biochemical structure of FNIP1. (A) The genomic background of FNIP1. (B) Protein structure of FNIP1. (C) Biological assembly of FNIP1.FNIP1, Folliculin Interacting Protein 1. (1) Gene annotation: The FNIP1 gene is located at the center of the diagram (marked in red), with an arrow indicating its direction, representing its transcription direction. Other genes related to FNIP1, such as CDC42SE2, LOC123497967, and LOC129661514, are listed around it, with their transcription directions indicated by arrows. (2) Chromosomal location: The position of the FNIP1 gene is labeled as 5q31.1, indicating that it is located at position 31.1 on the q arm (long arm) of chromosome 5. Its genomic location in the diagram is marked from 131210052 to 132012213, representing the chromosomal region where the FNIP1 gene is found. (3) Number of exons: The annotation in the diagram indicates that the FNIP1 gene has 18 exons. Exons are the coding regions of the gene that, after transcription, are converted into mRNA and involved in protein synthesis. (4) Relative position and relationship of genes: The diagram uses arrows to indicate the relative positions of other genes, showing their locations and transcription directions near the FNIP1 gene. These genes may be related to the function or regulation of FNIP1, such as CDC42SE2 and LOC123497967. (5) Arrows indicate the transcription direction of genes: The direction of each arrow represents the transcription direction of the gene, which is the direction of mRNA synthesis. The direction of the arrow indicates that the transcription of the gene occurs from the 5′ end to the 3′ end, which is the general rule of gene transcription. These arrows are primarily unidirectional, indicating the transcription direction of the gene. In some cases, the arrow may be reversed (e.g., from right to left), indicating that the corresponding gene is transcribed in the reverse direction.

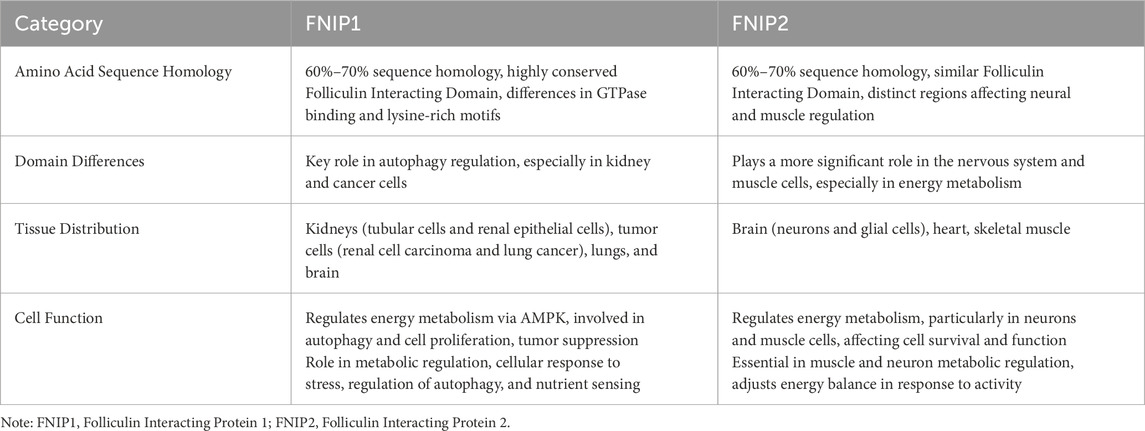

Table 2. Comparison of amino acid sequence homology, domain differences, tissue distribution, and cellular functions between FNIP1 and FNIP2.

AMPK is a cellular energy sensor and a crucial kinase regulating energy homeostasis, serving as one of the central regulators of cell and organism metabolism in eukaryotes. It is responsible for monitoring cellular energy input and output to maintain the smooth operation of cellular physiological activities (Rezvan et al., 2024). AMPK also plays a key role in multiple signaling pathways. It is activated under conditions of energy deficiency, and the classical AMPK signaling pathway is associated with increased AMP/ATP and ADP/ATP ratios (Sun et al., 2023). Activation of AMPK promotes ATP production through anabolic pathways and inhibits energy expenditure to restore energy balance. Additionally, AMPK, as a key regulatory factor in cellular energy sensing, maintains energy balance through various mechanisms when cellular energy is insufficient (Vega-Rubin-de-Celis et al., 2017). First, AMPK promotes ATP synthesis by activating catabolic pathways (such as glycogen breakdown and fatty acid oxidation), alleviating the intracellular environmental disturbance caused by cellular energy metabolism imbalance. Meanwhile, AMPK inhibits anabolic pathways (such as fatty acid synthesis and protein synthesis), reducing ATP consumption and optimizing the efficiency of cellular energy utilization (Xiao et al., 2024). In addition, AMPK regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism by activating the glucose transporter GLUT4 and enhancing the glycolytic pathway, as well as activating key enzymes of fatty acid oxidation (such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1)). AMPK also promotes mitochondrial repair and biogenesis by regulating genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis, such as PGC-1α (Carlisle et al., 2016; Collodet et al., 2019).

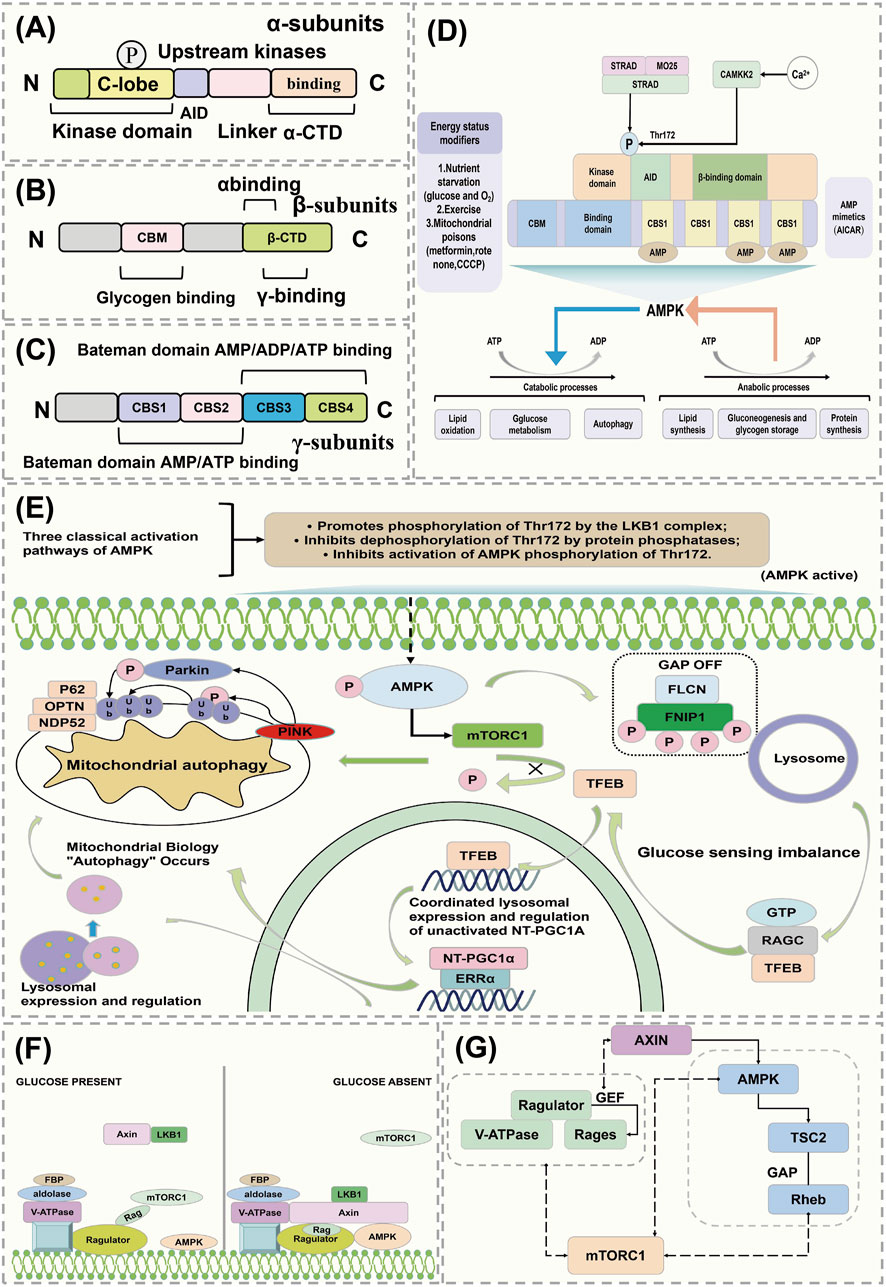

The conventional kinase domain of AMPK is located at the N-terminus of the α-subunit, followed by an autoinhibitory domain (AID). Following the AID is an extended linker peptide (highlighted in red in Figure 3A), which connects the AID to the C-terminal domain of the α-subunit (α-CTD) (Figure 3A) (Parmar et al., 2022). The β-subunit of AMPK contains a carbohydrate binding module (CBM) that may be involved in binding to targets such as glycogen synthase, although this function is not yet confirmed. The C-terminal domain of the β-subunit (β-CTD) interacts with the α-CTD and the γ-subunit, forming the core of the complex (Figure 3B) (Moreno-Corona et al., 2023). The γ-subunit of AMPK contains four tandem repeats of the CBS motif (CBS1-CBS4). These tandem repeats occur in a few other proteins, such as cystathionine β-synthase, and typically assemble as two repeats to form a Bateman domain, with ligand-binding sites in the crevices between the repeats (Hasumi et al., 2015). The CBS core contains four potential ligand-binding sites (Figure 3C). Upstream kinase CAMKK2 is activated by intracellular calcium ions, and the heterotrimeric complex of LKB1 with STRAD and MO25 triggers the mechanistic activation of AMPK (Zhang L. et al., 2023). Activators of AMPK include oxygen stress, glucose starvation, exercise, and mitochondrial toxins. The function of AMPK activation is to promote catabolic metabolism and reduce anabolic processes, decrease ATP consumption, increase ATP synthesis, and maintain energy balance (Figure 3D) (Wang X. et al., 2023).

Figure 3. AMPK regulates the mechanism of action of FNIP1. (A–C) AMPK conventional kinase structure. (D) AMPK maintains energy balance. (E) Mechanism of action of AMPK activation of FNIP1. (F) Activation pathway of AMPK. (G) Mutual regulation of mTOR and AMPK. AID, Activation-induced cytidine deaminase; STRAD, STE20-related kinase adaptor protein; MO25, MO25 alpha/beta (MO25 forms a complex with LKB1 and STRAD proteins involved in the regulation of cell polarity and metabolism); CAMKK2, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2; CBM, Carbohydrate-binding modules; CBS1, Cystathionine beta-synthase 1; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ coactivator l alpha; OPTN, Optineurin; FBP, Fatty acid-binding protein; LKB1, Liver kinase B1; AXIN, Axis Inhibition Protein 1; TSC2, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex.

FNIP1 is a conserved substrate of AMPK that controls the phosphorylation status and localization of TFEB. FNIP1 is an established interacting partner of FLCN and has been reported to co-immunoprecipitate with AMPK (Cai et al., 2024), although the specific details of this regulation by AMPK are still unclear. The FNIP1-FLCN complex acts as an amino acid sensor affecting the mTORC1 signaling pathway, with amino acids playing a role in controlling the activation of TFEB (41). Studies have found that AMPK can regulate FNIP1 to control TFEB independently of amino acids (Herzig and Shaw, 2018). The phosphorylation of FNIP1 by AMPK-dependent mechanisms controls the interaction between mTORC1 and TFEB/TFE3. Phosphorylation of FNIP1 by AMPK inhibits the GAP activity of the FNIP1-FLCN complex, controlling the transcription factor TFE via RagC (Figure 3E) (Carling, 2017; Herzig and Shaw, 2018; Wang X. et al., 2023).

Recent research has revealed that AMPK can sense cellular energy status and also detect glucose availability independently of adenylate changes, through an aldolase mechanism (Trefts and Shaw, 2021). AMPK and mTOR interact, where mTOR can activate AMPK through non-classical pathways, while also being subject to effective regulation by AMPK (Kim et al., 2016). Under high glucose conditions, aldolase is occupied by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), and the Rag activity regulator converts RagA/B to the GTP-bound form, recruiting mTORC1 to the lysosome where mTORC1 may be activated under suitable conditions (GTP-bound forms of RagC/D, GTP-bound form of Rheb) (González et al., 2020). Under low glucose conditions, the absence of FBP in aldolase leads to changes in its interaction with the V-ATPase, causing dissociation of mTORC1 and forming a ‘supercomplex’ that includes V-ATPase, regulator, AXIN, LKB1, and AMPK (based on the AXIN-AMPK activation complex), thereby triggering phosphorylation of AMPK on Thr172, thus activating AMPK (Figure 3F) (Chen et al., 2024; Freemantle and Hardie, 2023). mTORC1 activity is regulated by two parallel mechanisms: under glucose depletion, the regulator’s GEF activity towards RAGs is inhibited, converting RAG to the GDP-bound form and inhibiting mTORC1 (Ramirez Reyes et al., 2021). Additionally, AXIN binds with the regulator, inhibiting its GEF activity towards RAGs. Activated AMPK can also phosphorylate TSC2 and activate its GAP activity to inactivate Rheb, or directly phosphorylate key components of mTORC1 such as Raptor, leading to inhibition of mTORC1 (Figure 3G) (Paquette et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2023).

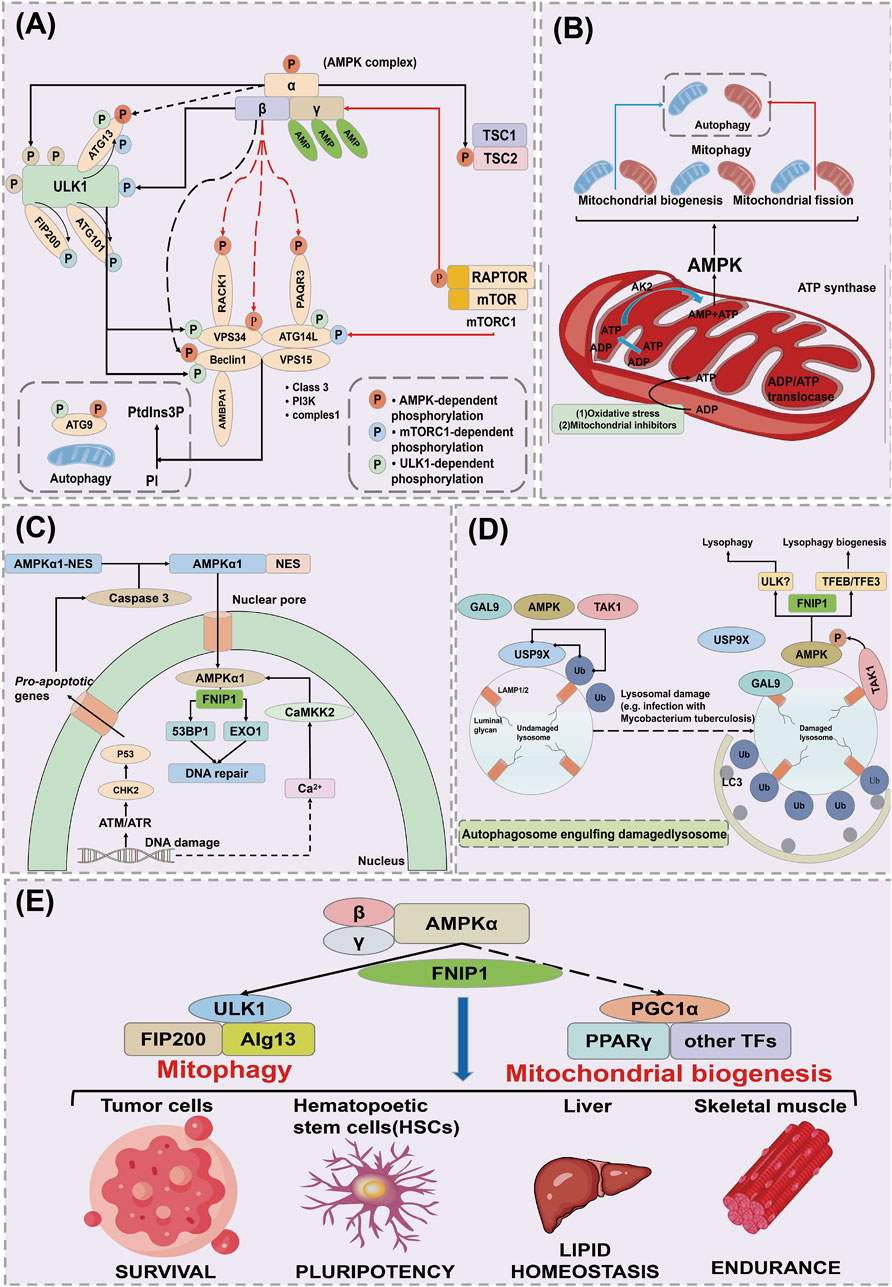

Autophagy is a process by which cells maintain homeostasis, clear waste, and reconstruct cellular structures by self-ingesting and degrading damaged or unnecessary materials within the cell (such as damaged organelles, excess proteins, and pathogens) under both internal and external environmental stress (Russell and Hardie, 2020). Autophagy plays an important role in cellular physiological processes and also serves a protective function in helping cells respond to environmental challenges such as starvation, oxidative stress, and infection. Autophagy is mainly regulated through essential genes-ATG. During the process of autophagy, ULK1 is phosphorylated and activates a PI3K complex composed of VPS34, VPS15, ATG14L, and Beclin1 (MacDonald et al., 2018). This complex generates phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) on nascent autophagosome membranes, forming an autophagic membrane that includes ATG9 (Zhang et al., 2017). ATG9 is the only transmembrane ATG protein, which is activated by the action of ATG4, ATG7, and ATG3 (LC3I), producing LC3II (Zhang et al., 2014). LC3II serves as a marker for autophagy to visualize autophagosomes and quantify autophagy in cells, and it can bind to autophagy receptors such as SQSTM1, NDP52, NBR1, and OPTN (Chen et al., 2017). Subsequently, autophagosomes mature and fuse with lysosomes in a process mediated by a complex composed of VPS34, VPS15, Beclin1, and UVRAG, inducing lysosomal enzymes to degrade targeted cells (Figure 4A) (Kwiatkowski and Manning, 2005).

Figure 4. AMPK regulates the mechanism of action of FNIP1. (A) Mechanisms of cellular autophagy. (B) AMPK acts on mitochondrial autophagy through FNIP1. (C) AMPK acts on DNA damage and repair through FNIP1. (D) AMPK acts through FNIP1 for lysosomal injury. (E) AMPK regulates autophagy through FNIP1 to affect various physiological functions. ULK1, Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1; ATG13, Autophagy Related 13; FIP200, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa; RACK1, Receptor of activated protein kinase C1; VPS34, Vacuolar Protein Sorting 34; ATG14L, Autophagy-related protein 14-like; AMBPA1, Autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1 gene; ATG9, Autophagy-related protein 9; EXO1, Exonuclease 1; CHK2, Checkpoint kinase2; GAL9, Growth arrest-specific protein 9; TAK1, Transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1; USP9X, Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 9X-linked.

AMPK plays a crucial role in sensing and responding to mitochondrial damage by directly phosphorylating FNIP1, leading to the inhibition of the FLCN binding GAP activity of FNIP1 (Avruch et al., 2006). This results in the accumulation of Rag C in its GTP-bound form, causing the dissociation of Rag C, the mTORC1, and the transcription factor EB (TFEB) from the lysosome (Terešak et al., 2022). AMPK plays a crucial role in sensing and responding to mitochondrial damage. AMPK directly phosphorylates FNIP1, inhibiting the GAP activity of FLCN, leading to the accumulation of RagC in its GTP-bound form. The GTP-bound form of RagC promotes its activation and forms a complex with RagA, subsequently activating mTORC1, which translocates to the lysosome. In this process, mTORC1 phosphorylates TFEB, inhibiting its nuclear translocation and preventing TFEB from activating the expression of autophagy-related genes (Vega-Rubin-de-Celis et al., 2017). However, when RagC and mTORC1 are activated, mTORC1 dissociates and relieves the inhibition on TFEB, promoting TFEB’s translocation to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis genes, thereby initiating cellular autophagic and metabolic responses (Ramirez Reyes et al., 2021; Wang X. et al., 2023). Through this mechanism, RagC and mTORC1 regulate autophagic activity in cells under stress conditions, helping cells adapt to energy depletion or damaged environments. Unphosphorylated TFEB translocates to the nucleus, inducing the transcription of lysosomal or autophagy genes, while NT-PGC 1α mRNA levels increase in parallel, consistent with Estrogen-Related Receptor α (ERRα), inducing changes in mitochondrial structure such as enhancing Ca2+ exchange between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This leads to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, excessive opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), and release of cytochrome C (Cyt C), causing mitochondrial dysfunction and disturbances in energy metabolism (Kim et al., 2011). Due to oxidative damage or chemical inhibitors, the F1 ATP synthase located on the cristae surface is inhibited, increasing the mitochondrial inner ADP/ATP ratio (Kumariya et al., 2021). This is conveyed through an increased ADP/ATP ratio in the intermembrane/cristae space via the ATP/ADP translocase, in turn converting ADP to AMP via the catalytic action of adenylate kinase (AK2). This reversible conversion activates AMPK, thereby promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, fission, and mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis (Figure 4B) (Sun et al., 2021).

DNA damage leads to an increase in nuclear Ca2+, potentially due to its release from the nuclear envelope, although its exact source remains unclear. Concurrently, DNA damage may trigger apoptosis through the activation of the DNA damage-sensitive kinases ATM/ATR and CHK2 downstream of p53 (Hao et al., 2022). This results in the activation of cysteine-aspartic acid protease 3 (caspase 3), which cleaves the nuclear export signal (NES) of AMPK α1, causing its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Filali-Mouncef et al., 2022). Within the nucleus, the AMPK complex containing α1 is phosphorylated and activated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2), triggered by the elevation of Ca2+ (Heo et al., 2018). AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits the exonuclease EXO1 and the p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1), assisting in DNA damage repair (Figure 4C) (Tudorica et al., 2024).

In undamaged lysosomes, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP9X removes ubiquitin clusters from the lysosomal surface (Yamano et al., 2024). Lysosomal damage exposes the lumenal glycosides on LAMP1/LAMP2, recruiting the cytosolic lectin galectin-9 (GAL9) (Marchesan et al., 2024). This, in turn, recruits AMPK and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Activated Kinase 1 (TAK1) to the lysosomal surface, displacing USP9X. The absence of USP9X enhances the formation of ubiquitin clusters on the lysosomal surface, thus triggering autophagosome engulfment, and also promotes the formation of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains on the TAK1 complex, leading to its activation and subsequent activation of AMPK (Jia et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2023; Shariq et al., 2024). AMPK promotes lysophagy, possibly involving the phosphorylation of ULK1, while simultaneously activating TFEB/TFE3 to stimulate the biogenesis of new lysosomal components (Figure 4D) (Arhzaouy et al., 2019; Nakamura et al., 2021). After AMPK activation, it phosphorylates TSC2 and RAPTOR, leading to the downregulation of the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which consists of mTOR, RAPTOR, mLST8, DEPTOR, and PRAS40 (Cheng et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024). AMPK activation also phosphorylates ULK1, enhancing its activity and initiating the autophagic process (Jolly et al., 2009). Activated AMPK stimulates mitophagy through ULK1, while simultaneously promoting new mitochondrial production via transcriptional regulation through PGC-1α (Premarathne et al., 2017). This dual regulation process of AMPK can replace defective mitochondria with new functional ones, achieving a “cleansing effect” of the mitochondria (Figure 4E) (Jaiswal et al., 2021).

Redox stress refers to the stress response caused by the imbalance of oxidation-reduction within the intracellular and extracellular environment. This imbalance leads to the generation of large amounts of ROS, subsequently causing lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, protein oxidation, and DNA damage (Liubomirski et al., 2019). While oxidative phosphorylation can efficiently produce ATP, it also generates ROS as a metabolic byproduct. When ROS consumption is below its physiological level (The consumption of ROS within the cell is lower than what is required for normal physiological conditions) (Reyes et al., 2015), this phenomenon is referred to as reductive stress, which is an imbalance in redox state due to either an excessive reduction capacity or an abundance of high-reduction potential substances within the organism (Izrailit et al., 2017). Redox stress plays a crucial role in the development of various diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory diseases. Oxidative Stress (OS) results from the accumulation of ROS, leading to a disturbance in the cellular redox state. The steady-state level of ROS is important for cell physiology and signaling, but excessive ROS can induce reductive stress, ranging from the destruction of biomolecules to apoptosis (Inoki et al., 2002). Additionally, oxidative stress can impair the function of redox-sensitive organelles, including mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

Andrew G Manford in Cell demonstrated that cells mitigate reductive stress by ubiquitination and degradation of the mitochondrial gatekeeper FNIP1, with CUL2FEM1B relying on zinc as a molecular glue to selectively recruit reduced FNIP1 during reductive stress (Huang and Manning, 2009; Inoki et al., 2002; Izrailit et al., 2017; Liubomirski et al., 2019). FNIP1 ubiquitination is gated by the pseudo-substrate inhibitors of the BEX family, preventing premature degradation of FNIP1 to protect cells from unnecessary ROS accumulation. Functional mutations in FEM1B and deficiencies in BEX result in similar developmental syndromes, suggesting that zinc-dependent reductive stress responses must be tightly regulated to maintain cellular and organismal homeostasis (PMID: 34562363) (Hu et al., 2021). Wenqian Zhang found that FNIP1 improves oxidative stress and rescues impaired angiogenesis in HUVECs under high glucose conditions (Wang and Jia, 2023). Zhang developed a novel glucose-responsive HA-PBA-FA/EN106 hydrogel for localized drug delivery and regulation of FNIP1 at diabetic wound sites. Due to the dynamic boronate ester bonds between hyaluronic acid (HA) and phenylboronic acid (PBA), the hydrogel enables glucose-responsive drug release. The release of the FEM1b-FNIP1 axis inhibitor EN106 through the regulation of the FEM1b-FNIP1 axis mitigates oxidative stress and stimulates angiogenesis, offering a promising strategy for chronic diabetic wound healing, and also serves as proof of FNIP1 as an effector of reductive stress (Paul et al., 2023).

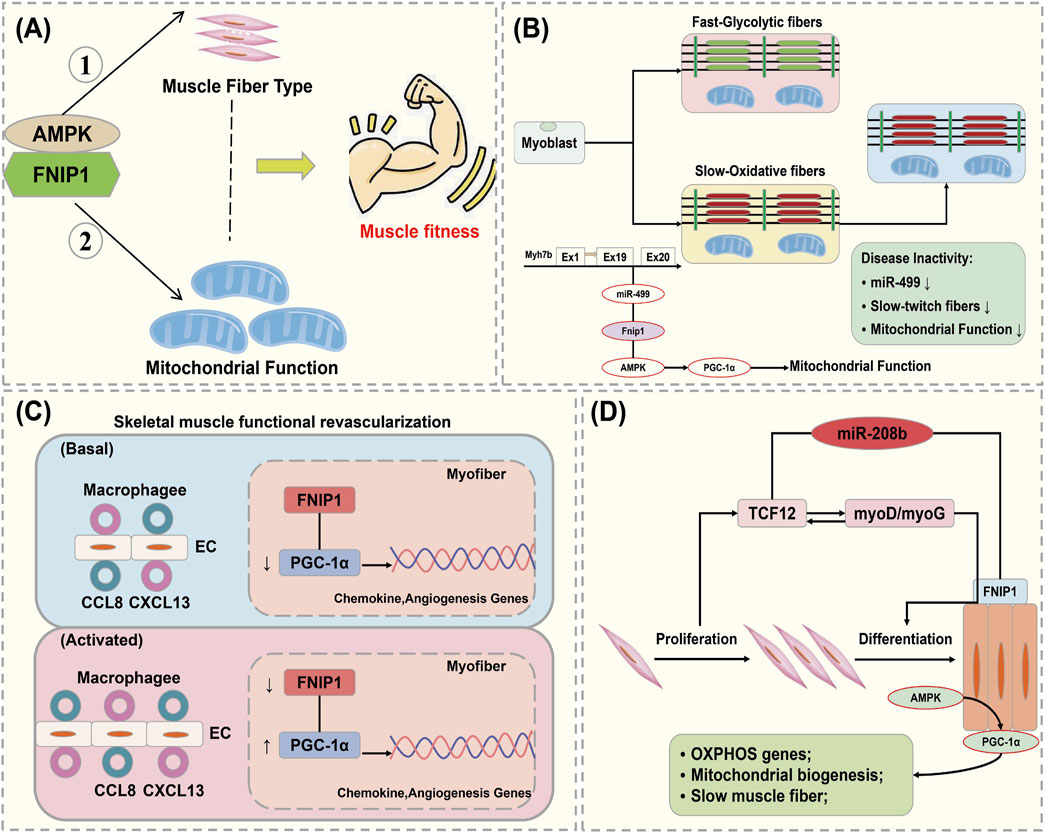

The maintenance of mitochondrial function is crucial for skeletal muscle metabolic homeostasis under both physiological and pathological conditions. Mitochondrial function, muscle fiber contraction, and vascular damage reconstruction all contribute to the physiological mechanisms that maintain muscle function. Xiao L discovered that FNIP1 is associated with skeletal muscle fiber type specification, function, and disease. FNIP1 is specifically expressed in the skeletal muscle of FNIP1 transgenic (FNIP1Tg) mice, and it was found that FNIP1 influences muscle mitochondrial oxidation processes through AMPK signaling (Henning et al., 2022). The action of FNIP1 on type I muscle fiber programming is independent of AMPK and its downstream target PGC-1α. This suggests that FNIP1 serves as a key factor in the coordinated regulation of mitochondrial function and muscle fiber type, which are determinants of muscle health (Figure 5A) (Gilder et al., 2013).

Figure 5. Interaction of FNIP1 with autophagy. (A) FNIP1 and myofiber mitochondrial function, AMPK independent; (A) AMPK/PGC-1 dependent. (B) FNIP1 signaling pathway affects muscle fiber function. (C) FNIP1 and blood vessels. (D) FNIP1 and muscle fiber homeostasis. EC, endothelial cell; CCL8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 8; CXCL13, C-X-C motif ligand 13; TCF12, Transcription Factor 12.

Exercise-induced activation of AMPK and substrate phosphorylation regulates mitochondrial metabolic capacity in skeletal muscle. Liwei Xiao found that AMPK phosphorylation of FNIP1 at serine-220 (S220) controls mitochondrial function and muscle fuel utilization during exercise. The absence of FNIP1 in skeletal muscle leads to increased mitochondrial content and enhanced metabolic capacity, thereby enhancing exercise endurance in mice, and demonstrating that muscle AMPK-induced phosphorylation of FNIP1 (S220) regulates mitochondrial electron transport chain complex assembly, fuel utilization, and exercise performance. Thus, FNIP1 is a multifunctional AMPK effector used for the mechanisms of mitochondrial adaptation to exercise capacity and endurance (Barford, 2011). When skeletal muscle adapts to physiological and pathophysiological stimuli, muscle fiber type and mitochondrial function are coordinately regulated. Preliminary studies identified pathways involved in the control of oxidative fiber contraction proteins. Jing Liu elucidated the mechanisms coupling mitochondrial function with muscle contraction mechanisms during fiber type transition, where the expression of genes encoding type I myosin proteins, Myh7/Myh7b, and their intronic miR-208b/miR-499 is parallel to mitochondrial function during fiber type transition. miR-499 drives PGC-1α-dependent mitochondrial oxidative metabolism to match the changes in slow muscle fiber composition. It was demonstrated that miT-499 directly targets FNIP1, serving as a negative regulator of the AMPK interacting protein (Wang Y. et al., 2023). This implies that inhibiting FNIP1 reactivates AMPK/PGC-1α signaling and mitochondrial function in myocytes, and identifies the miR-499/Fnip1/AMPK signaling pathway as a regulator of muscle fiber type and mitochondrial function mechanisms (Figure 5B) (Tsai et al., 2024).

The main cause of damage and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle cells is impaired blood supply, where mechanisms of functional angiogenesis protect against the damage to myocardial and skeletal muscles by preserving blood flow. Zongchao Sun’s research discovered that FNIP1 controls functional angiogenesis in skeletal muscles, reconstructing muscle blood flow during ischemia. Muscle FNIP1 expression is downregulated by exercise. Genetic overexpression of FNIP1 in muscle fibers restricts angiogenesis in mice, whereas its fiber-specific ablation significantly promotes the formation of functional blood vessels. The increase in muscle vascularization is independent of AMPK but is due to enhanced macrophage recruitment in muscle cells depleted of FNIP1 (Zhang W. et al., 2023). FNIP1 deficiency in muscle fibers induces the activation of PGC-1α and chemotactic factor gene transcription, thereby driving macrophage recruitment and muscle vascularization programs, and the absence of muscle fiber FNIP1 significantly improves blood flow recovery (Figure 5C) (Zhu et al., 2023). Embryonic and neonatal skeletal muscles grow through the proliferation and fusion of myogenic cells, while adult skeletal muscles adapt mainly by remodeling pre-existing fibers and optimizing metabolic balance. Fu L’s research found that miR-208b stimulates the transition between fast and slow fibers and oxidative metabolism programs by targeting FNIP1 rather than the TCF12 gene. Moreover, miR-208b targeting of FNIP1 activates AMPK/PGC-1α signaling and mitochondrial biogenesis. Therefore, miR-208b specifically targets TCF12 and FNIP1 to mediate skeletal muscle development and homeostasis (Figure 5D) (Sopariwala et al., 2021).

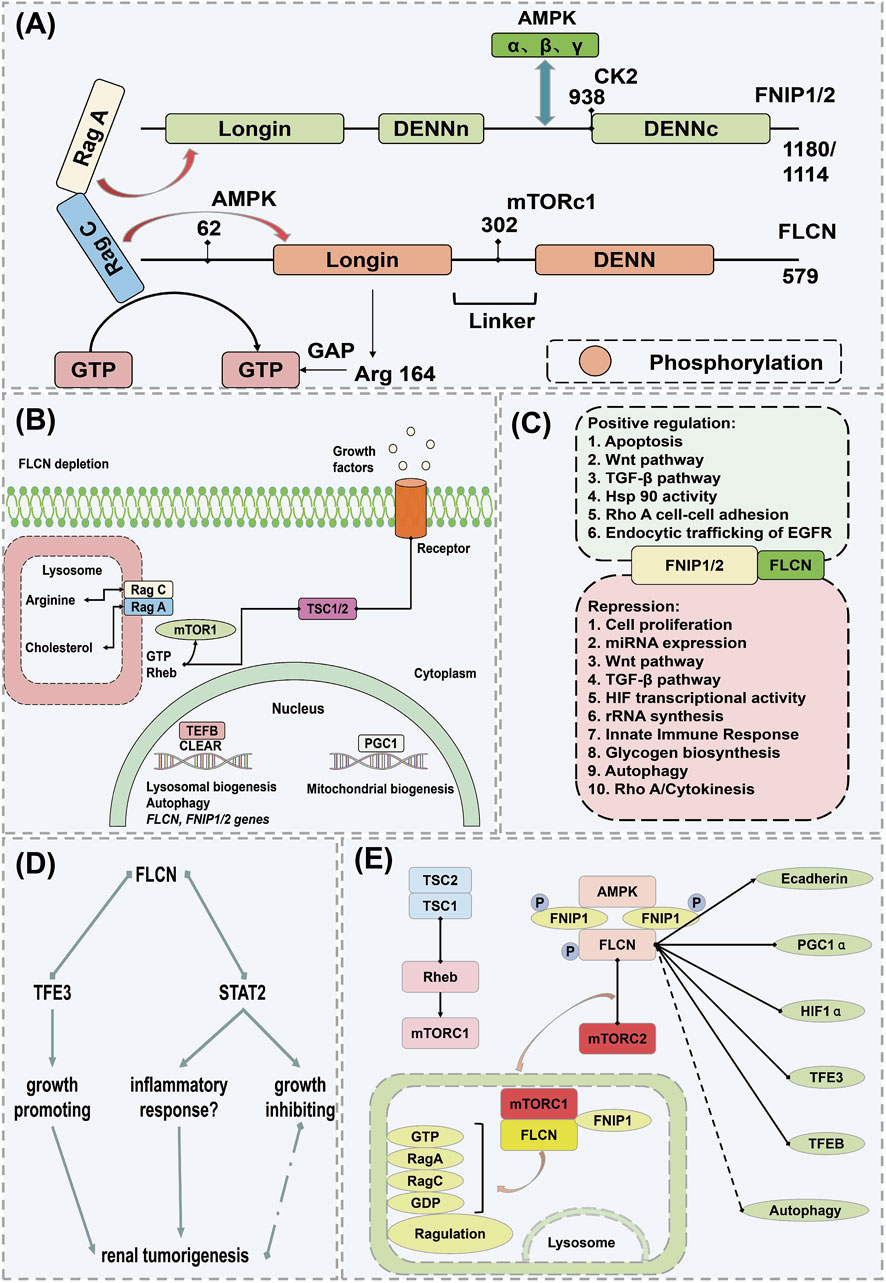

FNIP1 is a protein associated with multiple biological processes and diseases, playing a particularly complex role in the development and progression of tumors (Rowe et al., 2014). FNIP1, closely linked to oncological functions, was initially identified as an interacting protein of the tumor suppressor gene Folliculin (FLCN) (Figure 6A). The Folliculin (FLCN) gene, identified in 2002, is responsible for Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by fibrofolliculomas, pulmonary cysts, increased spontaneous pneumothorax frequency, and bilateral multifocal renal tumors (Blenis, 2017; Hardie, 2011). Folliculin forms complexes with two proteins, FNIP1 and FNIP2, serving as functional partners of FLCN. The dual inactivation of FNIP1/2 in mouse kidneys leads to polycystic kidney enlargement akin to FLCN deficiency, highlighting their roles as tumor suppressors, as mice with FNIP1 and/or FNIP2 knockouts exhibit tumors in multiple organs (Erdogan et al., 2016). As anticipated, the regulatory role of the FLCN/FNIP complex in Rab GTPases and membrane trafficking is delineated (Figure 6B) (Lushchak et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2012). FLCN, a pleiotropic protein, participates in numerous cellular processes. The function of the FLCN/FNIP complex is chiefly mediated through the regulation of two key protein kinases: the mTORC1 and AMPK (Moreno-Corona et al., 2023). The FLCN/FNIP complex promotes balance by coordinating mTORC1 and AMPK activities, with the crosstalk between these pathways further orchestrating metabolic adaptation to nutrient and energy conditions (Figure 6C) (Manford et al., 2020).

Figure 6. Mechanism of action of FNIP1 in causing cancer. (A) Structural domains of FLCN and FNIP and their interacting proteins. (B) Inactive state of Rag C/D under FLCN depletion. (C) Additional pathways and cellular processes regulated by the FLCN/FNIP complex. (D) Mechanistic pathway of FLCN knockout. (E) FLCN-related pathways potentially leading to renal tumor formation under FLCN deficiency. Arrows indicate activation, and dots represent inhibition; if both symbols are present, the interaction is either conflicting or unclear. AMPK, Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase; CAMKK2, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2; ERRα, Estrogen Receptor alpha; FLCN, Folliculin; FBP, Fatty acid-binding protein; FNIP1, Folliculin Interacting Protein 1; GATOR1, GAP activity toward Rags 1; GAL9, Growth arrest-specific protein 9; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; PGC1α, Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ coactivator l alpha; STRAD, STE20-related kinase adaptor protein; TAK1, Transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1; TSC1, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1; TSC2, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex; TCF12, Transcription Factor 12.

Iris E and colleagues demonstrated that disruption of FLC of human renal tubular epithelial cells (RPTEC/TERT1) activates TFE3, which upregulates the expression of its E-box targets, including Ras Related GTP Binding D (RRAGD) and GPNMB, without altering mTORC1 activity. Loss of the FLCN and FNIP1/FNIP2 complex triggered an interferon-independent response gene. FLCN deficiency promoted STAT2 recruitment to chromatin and decelerated cell proliferation, underscoring the FLCN and FNIP1/FNIP2 complex’s distinctive role in the development of human renal tumors and identifying potential prognostic biomarkers (Figure 6D) (Rallis et al., 2013; Schmidt and Linehan, 2018). Hisashi’s scientific team observed that in organs exhibiting a phenotype under Fnip1 deficiency, Fnip2 mRNA copy numbers are lower than those of Fnip1 but comparable to Fnip1 mRNA levels in mouse kidneys. Targeted dual inactivation of FNIP1/FNIP2 led to the enlargement of polycystic kidneys. Heterozygous FNIP1/homozygous FNIP2 double knockout mice developed renal cancer at 24 months, akin to heterozygous FLCN knockout mouse models, thereby reinforcing the significance of FNIP1 and Fnip2 in tumor suppression and suggesting potential molecular targets for novel renal cancer therapies (Hasumi et al., 2016; Mo et al., 2019). Professor Leeanna found that FLCN, FNIP1, and FNIP2 are downregulated in various human cancers, particularly in poorly prognostic invasive basal-like breast cancer, as opposed to luminal, less aggressive subtypes. In luminal breast cancer, the loss of FLCN activates TFE3, which then induces pathways promoting tumor growth, such as autophagy, lysosome biogenesis, aerobic glycolysis, and angiogenesis. Importantly, the induction of aerobic glycolysis and angiogenesis in FLCN-deficient cells results from the activation of the PGC-1α/HIF-1α pathway, which is TFE3-dependent, thereby directly linking TFE3 to Warburg metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis. These findings underscore the broad role of the dysregulated FLCN/TFE3 tumor suppressor pathway in human cancers (de Martín Garrido and Aylett, 2020; Skidmore et al., 2022). Masaya’s team reaffirmed that mutations in FLCN and its interacting partner FNIP1, involved in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, may play a role in energy and nutrient sensing through the AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways. Laura S’s research identified that germline mutations on chromosome 17 in the FLCN gene are responsible for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, with BHD-associated renal tumors displaying inactivation of the wild-type FLCN allele due to somatic mutations or chromosomal loss, thus confirming FLCN as a tumor suppressor gene consistent with the classic two-hit model. FLCN interacts with two novel proteins, FNIP1 and FNIP2, and the negative regulator of mTOR, AMPK. Understanding the FLCN pathway may lead to the development of effective targeted systemic treatments for the disease (Figure 6E) (Furuya and Nakatani, 2013; Zhou et al., 2017).

Through its interaction with FLCN, FNIP1 modulates the mTOR signaling pathway, influencing cellular energy metabolism and viability (Kennedy et al., 2016). Dysfunctions in FNIP1 are associated with various types of cancer, including renal cell carcinoma (Woodford et al., 2021). In renal cancer, reduced expression of FNIP1 is correlated with increased tumor aggressiveness and malignancy (Clausen et al., 2020). Additionally, FNIP1 regulates cellular responses to hypoxic conditions, further linking these to metabolic reprogramming and resistance development in tumors (Schmidt, 2013). Single-cell sequencing technologies have been employed to explore variations in FNIP1 expression across different tumor cells, elucidating FNIP1’s complex role in tumor heterogeneity and progression (Tsun et al., 2013). These studies suggest that FNIP1 may have distinct functions and impacts across various tumor subtypes and microenvironments, offering new insights for precision medicine (Lawrence et al., 2019). Future research should delve into the specific mechanisms of FNIP1 in various cancers and investigate how these findings can be translated into clinical applications, potentially leading to more targeted and effective treatments.

FNIP1, a protein involved in various biological processes, particularly in regulating the mTOR signaling pathway and cellular energy metabolism, demonstrates significant potential for clinical applications. Research on FNIP1’s functions offers new insights and potential strategies for treating mitochondrial diseases, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, disease prognosis assessment, and personalized medicine. FNIP1 plays a crucial role in regulating cellular energy metabolism and mitochondrial function, making it a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in the study and treatment of mitochondrial diseases. Studies indicate that FNIP1 may influence mitochondrial function and stability by regulating processes such as mitochondrial biogenesis, membrane potential, and oxidative phosphorylation (Lawrence et al., 2019). Consequently, therapeutic strategies targeting FNIP1 could represent a new approach to the treatment of mitochondrial diseases. Further research into the mechanisms of FNIP1’s role in the progression of mitochondrial diseases will aid in understanding the pathogenesis of these conditions and provide a theoretical basis for developing new treatment strategies. FNIP1 is clsely associated with the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Initially, FNIP1 is involved in regulating cellular energy metabolism and glucose homeostasis, which are linked to common metabolic disorders in cardiovascular diseases such as atrial fibrillation and arrhythmias (Nakamura et al., 2021; Schmidt and Linehan, 2015). Studies indicate that metabolic disorders are a significant cause of cardiovascular diseases, and FNIP1 may act as a key regulator in these disorders, playing a crucial role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular conditions (Hong et al., 2018; Zhang H. et al., 2023). Furthermore, FNIP1 is closely related to processes such as cardiomyocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis, which play key roles in the development of cardiovascular diseases. Research suggests that abnormal expression of FNIP1 may affect the function of endothelial cells, thereby influencing the stability of blood vessel walls and blood flow, ultimately impacting cardiovascular health (Hasumi et al., 2016; Woodford et al., 2021). Consequently, FNIP1 could serve as a biomarker for assessing cardiovascular disease risk and predicting disease progression. Moreover, studies have found that the expression levels of FNIP1 in patients with cardiovascular diseases are closely linked to treatment outcomes (De Conti et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2021), potentially making FNIP1 an important marker for evaluating the effectiveness of cardiovascular disease treatments and guiding personalized therapy.

FNIP1 also holds promising clinical application prospects in skeletal muscle diseases. It plays a critical role in regulating the metabolism, growth, and function of skeletal muscles, making it a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for the study and treatment of skeletal muscle diseases. Skeletal muscle diseases often involve muscle atrophy, degeneration, and dysfunction, and as a key regulator of cellular energy metabolism and protein synthesis, abnormal expression or dysfunction of FNIP1 can impair skeletal muscle function (Hasumi et al., 2008; Yin et al., 2022). Therefore, studying the expression levels of FNIP1 in patients with skeletal muscle diseases and their correlation with disease severity and prognosis can aid in assessing disease progression and predicting patient outcomes. Some skeletal muscle diseases’ pathogenesis involves mitochondrial dysfunction, and as a crucial regulator of mitochondrial function, abnormal expression or dysfunction of FNIP1 could lead to mitochondrial impairment, thereby affecting skeletal muscle function and stability (Parmar et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2017). FNIP1 may be involved in regulating processes such as protein synthesis, cellular signaling, and muscle regeneration in skeletal muscles, affecting muscle growth and repair. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting FNIP1 could represent a new avenue for treating skeletal muscle diseases and provide a theoretical basis for developing new treatment approaches. The interaction between FNIP1 and FLCN critically regulates the mTOR pathway, affecting cellular responses to energy and nutrients, with aberrant activation of these pathways closely associated with the progression of mitochondrial diseases. Consequently, FNIP1 emerges as a potential pharmacological target for regulating these key biological processes. The development of drugs targeting FNIP1, whether small molecule inhibitors or activators, may pave new therapeutic pathways, particularly for types of mitochondrial diseases where traditional treatments are ineffective. Moreover, FNIP1 also shows broad potential in drug resistance and as a biomarker (Sun et al., 2021; Tsun et al., 2013). With the advancement of personalized medicine, the expression and functional status of FNIP1 could help physicians more accurately determine disease prognosis, select the most appropriate treatment options, and enhance therapeutic outcomes. Although FNIP1 has shown significant potential in laboratory research and preclinical models, its efficacy and safety in clinical applications still require validation through systematic clinical trials. Future research needs to address the dosage, pharmacodynamics, side effects, and long-term effects of FNIP1-targeted therapies. Additionally, research should also explore the role of FNIP1 in oncological diseases, such as its potential involvement in metabolic disorders, neurological diseases, and other possible pathological conditions. The mechanism of action of FNIP1 in clinical practice is shown in Table 3.

FNIP1 has emerged as a pivotal player in cellular metabolism and signaling pathways, making it a compelling candidate for therapeutic targeting. This review delves into the clinical applications of FNIP1, emphasizing its potential as a drug target. We analyze recent advancements in FNIP1 research, elucidating its role in disease modulation and therapeutic efficacy. The landscape of targeted therapeutics has evolved significantly, with the identification of novel molecular targets that offer promise for precision medicine. FNIP1, a key regulator within the mTOR signaling pathway, has garnered attention due to its involvement in metabolic processes and disease pathogenesis. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of FNIP1’s clinical applications, focusing on its relevance as a drug target. By synthesizing findings from recent high-impact studies, we elucidate the potential of FNIP1 in clinical interventions. FNIP1 functions as a crucial modulator of the mTORC1 pathway, integrating signals related to cellular energy status and nutrient availability. It interacts with FLCN, forming a complex that regulates AMPK and mTORC1 activity. Disruptions in FNIP1 expression or function have been linked to metabolic disorders, tumorigenesis, and other pathologies, highlighting its significance in maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Cancer Therapy: FNIP1’s involvement in mTOR signaling makes it a viable target for cancer treatment. Preclinical studies have shown that FNIP1 inhibitors can reduce tumor growth and enhance the efficacy of existing therapies. Metabolic Disorders: By regulating AMPK activity, FNIP1 influences glucose metabolism and lipid homeostasis. Therapeutic modulation of FNIP1 could offer novel treatments for metabolic diseases. Neurodegenerative Diseases: Emerging evidence suggests that FNIP1 plays a role in autophagy and cellular stress responses, providing a potential target for neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

While FNIP1 presents a promising target, several challenges must be addressed to realize its clinical potential. These include: Specificity and Off-target Effects: Developing highly specific FNIP1 inhibitors to minimize off-target effects. Biomarker Development: Identifying biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment monitoring. Combinatorial Approaches: Exploring combination therapies that include FNIP1 targeting to enhance therapeutic outcomes. FNIP1 stands at the forefront of potential therapeutic targets due to its integral role in cellular signaling and metabolism. Continued research and clinical trials are essential to fully harness its potential in treating a wide array of diseases. By advancing our understanding of FNIP1’s mechanisms and interactions, we pave the way for novel, targeted therapeutic strategies that could revolutionize clinical practice. This article discusses the important historical progress and structural features of FNIP1 and introduces its potential links and mechanisms of action with mitochondrial diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and reductive stress diseases through complex mechanisms such as AMPK cellular energy metabolism, mTOR signaling pathway, modification of cellular autophagy, and reductive stress response. Some research conclusions on these mechanisms may be inconsistent, but this also illustrates the complexity of FNIP1’s mechanisms of action. These differing viewpoints are the most interesting parts of scientific research and provide a scientific basis for becoming new therapeutic targets. In summary, as a multifunctional protein, FNIP1 plays an increasingly important role in future biomedical research and therapeutic development. By further exploring its specific roles and mechanisms in various diseases, we can look forward to developing new therapeutic strategies, and offering more effective and safer treatment options for patients.

QR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing–original draft. AL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing–original draft. BY: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft. CX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing–original draft. CQ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft. YZ: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing–original draft. XH: Investigation, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft. HC: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing–original draft.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82074396).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1523489/full#supplementary-material

Arhzaouy, K., Papadopoulos, C., Schulze, N., Pittman, S. K., Meyer, H., and Weihl, C. C. (2019). VCP maintains lysosomal homeostasis and TFEB activity in differentiated skeletal muscle. Autophagy 15 (6), 1082–1099. doi:10.1080/15548627.2019.1569933

Avruch, J., Hara, K., Lin, Y., Liu, M., Long, X., Ortiz-Vega, S., et al. (2006). Insulin and amino-acid regulation of mTOR signaling and kinase activity through the Rheb GTPase. Oncogene 25 (48), 6361–6372. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209882

Baba, M., Hong, S. B., Sharma, N., Warren, M. B., Nickerson, M. L., Iwamatsu, A., et al. (2006). Folliculin encoded by the BHD gene interacts with a binding protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is involved in AMPK and mTOR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103 (42), 15552–15557. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603781103

Baba, M., Keller, J. R., Sun, H. W., Resch, W., Kuchen, S., Suh, H. C., et al. (2012). The folliculin-FNIP1 pathway deleted in human Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is required for murine B-cell development. Blood 120 (6), 1254–1261. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-02-410407

Barford, D. (2011). Structure, function and mechanism of the anaphase promoting complex (APC/C). Q. Rev. Biophys. 44 (2), 153–190. doi:10.1017/s0033583510000259

Blenis, J. (2017). TOR, the gateway to cellular metabolism, cell growth, and disease. Cell 171 (1), 10–13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.019

Cai, L., Lin, L., Lin, S., Wang, X., Chen, Y., Zhu, H., et al. (2024). Highly multiplexing, throughput and efficient single-cell protein analysis with digital microfluidics. Small Methods 8 (12), e2400375. doi:10.1002/smtd.202400375

Cantó, C., and Auwerx, J. (2009). PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20 (2), 98–105. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4

Carling, D. (2017). AMPK signalling in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 45, 31–37. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2017.01.005

Carlisle, M., Lam, A., Svendsen, E. R., Aggarwal, S., and Matalon, S. (2016). Chlorine-induced cardiopulmonary injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1374 (1), 159–167. doi:10.1111/nyas.13091

Chen, J., Ou, Y., Li, Y., Hu, S., Shao, L. W., and Liu, Y. (2017). Metformin extends C. elegans lifespan through lysosomal pathway. Elife 6, e31268. doi:10.7554/eLife.31268

Chen, X., Raiff, A., Li, S., Guo, Q., Zhang, J., Zhou, H., et al. (2024). Mechanism of Ψ-Pro/C-degron recognition by the CRL2(FEM1B) ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 3558. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47890-5

Cheng, X. T., Xie, Y. X., Zhou, B., Huang, N., Farfel-Becker, T., and Sheng, Z. H. (2018). Revisiting LAMP1 as a marker for degradative autophagy-lysosomal organelles in the nervous system. Autophagy 14 (8), 1472–1474. doi:10.1080/15548627.2018.1482147

Clausen, L., Stein, A., Grønbæk-Thygesen, M., Nygaard, L., Søltoft, C. L., Nielsen, S. V., et al. (2020). Folliculin variants linked to Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are targeted for proteasomal degradation. PLoS Genet. 16 (11), e1009187. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009187

Collodet, C., Foretz, M., Deak, M., Bultot, L., Metairon, S., Viollet, B., et al. (2019). AMPK promotes induction of the tumor suppressor FLCN through activation of TFEB independently of mTOR. Faseb J. 33 (11), 12374–12391. doi:10.1096/fj.201900841R

Dai, Z., Liang, L., Wang, W., Zuo, P., Yu, S., Liu, Y., et al. (2024). Structural insights into the ubiquitylation strategy of the oligomeric CRL2(FEM1B) E3 ubiquitin ligase. Embo J. 43 (6), 1089–1109. doi:10.1038/s44318-024-00047-y

De Conti, L., Akinyi, M. V., Mendoza-Maldonado, R., Romano, M., Baralle, M., and Buratti, E. (2015). TDP-43 affects splicing profiles and isoform production of genes involved in the apoptotic and mitotic cellular pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (18), 8990–9005. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv814

de Martín Garrido, N., and Aylett, C. H. S. (2020). Nutrient signaling and lysosome positioning crosstalk through a multifunctional protein, folliculin. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 108. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00108

Dunlop, E. A., Seifan, S., Claessens, T., Behrends, C., Kamps, M. A., Rozycka, E., et al. (2014). FLCN, a novel autophagy component, interacts with GABARAP and is regulated by ULK1 phosphorylation. Autophagy 10 (10), 1749–1760. doi:10.4161/auto.29640

Erdogan, C. S., Hansen, B. W., and Vang, O. (2016). Are invertebrates relevant models in ageing research? Focus on the effects of rapamycin on TOR. Mech. Ageing Dev. 153, 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2015.12.004

Filali-Mouncef, Y., Hunter, C., Roccio, F., Zagkou, S., Dupont, N., Primard, C., et al. (2022). The ménage à trois of autophagy, lipid droplets and liver disease. Autophagy 18 (1), 50–72. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1895658

Freemantle, J. B., and Hardie, D. G. (2023). AMPK promotes lysosomal and mitochondrial biogenesis via folliculin:FNIP1. Life Metab. 2 (5), load027. doi:10.1093/lifemeta/load027

Fromm, S. A., Lawrence, R. E., and Hurley, J. H. (2020). Structural mechanism for amino acid-dependent Rag GTPase nucleotide state switching by SLC38A9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27 (11), 1017–1023. doi:10.1038/s41594-020-0490-9

Furuya, M., and Nakatani, Y. (2013). Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: clinicopathological features of the lung. J. Clin. Pathol. 66 (3), 178–186. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201200

Gilder, A. S., Chen, Y. B., Jackson, R. J., Jiang, J., and Maher, J. F. (2013). Fem1b promotes ubiquitylation and suppresses transcriptional activity of Gli1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 440 (3), 431–436. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.090

González, A., Hall, M. N., Lin, S. C., and Hardie, D. G. (2020). AMPK and TOR: the Yin and Yang of cellular nutrient sensing and growth control. Cell Metab. 31 (3), 472–492. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2020.01.015

Hao, W., Dian, M., Zhou, Y., Zhong, Q., Pang, W., Li, Z., et al. (2022). Autophagy induction promoted by m(6)A reader YTHDF3 through translation upregulation of FOXO3 mRNA. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 5845. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32963-0

Hardie, D. G. (2011). Energy sensing by the AMP-activated protein kinase and its effects on muscle metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 70 (1), 92–99. doi:10.1017/s0029665110003915

Hasumi, H., Baba, M., Hasumi, Y., Furuya, M., and Yao, M. (2016). Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: clinical and molecular aspects of recently identified kidney cancer syndrome. Int. J. Urol. 23 (3), 204–210. doi:10.1111/iju.13015

Hasumi, H., Baba, M., Hasumi, Y., Lang, M., Huang, Y., Oh, H. F., et al. (2015). Folliculin-interacting proteins Fnip1 and Fnip2 play critical roles in kidney tumor suppression in cooperation with Flcn. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112 (13), E1624–E1631. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419502112

Hasumi, H., Baba, M., Hong, S. B., Hasumi, Y., Huang, Y., Yao, M., et al. (2008). Identification and characterization of a novel folliculin-interacting protein FNIP2. Gene 415 (1-2), 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2008.02.022

Henning, N. J., Manford, A. G., Spradlin, J. N., Brittain, S. M., Zhang, E., McKenna, J. M., et al. (2022). Discovery of a covalent FEM1B recruiter for targeted protein degradation applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2), 701–708. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c03980

Heo, J. M., Ordureau, A., Swarup, S., Paulo, J. A., Shen, K., Sabatini, D. M., et al. (2018). RAB7A phosphorylation by TBK1 promotes mitophagy via the PINK-PARKIN pathway. Sci. Adv. 4 (11), eaav0443. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav0443

Herzig, S., and Shaw, R. J. (2018). AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19 (2), 121–135. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.95

Hong, K. H., Song, S., Shin, W., Kang, K., Cho, C. S., Hong, Y. T., et al. (2018). A case of interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma studied by whole-exome sequencing. Genes Genomics 40 (12), 1279–1285. doi:10.1007/s13258-018-0724-y

Hu, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, L., Lin, X., Li, X., Zhuang, H., et al. (2021). The AMPK-MFN2 axis regulates MAM dynamics and autophagy induced by energy stresses. Autophagy 17 (5), 1142–1156. doi:10.1080/15548627.2020.1749490

Huang, J., and Manning, B. D. (2009). A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37 (Pt 1), 217–222. doi:10.1042/bst0370217

Hung, C. M., Lombardo, P. S., Malik, N., Brun, S. N., Hellberg, K., Van Nostrand, J. L., et al. (2021). AMPK/ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of Parkin ACT domain mediates an early step in mitophagy. Sci. Adv. 7 (15), eabg4544. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abg4544

Inoki, K., Li, Y., Zhu, T., Wu, J., and Guan, K. L. (2002). TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 4 (9), 648–657. doi:10.1038/ncb839

Izrailit, J., Jaiswal, A., Zheng, W., Moran, M. F., and Reedijk, M. (2017). Cellular stress induces TRB3/USP9x-dependent Notch activation in cancer. Oncogene 36 (8), 1048–1057. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.276

Jaiswal, A., Murakami, K., Elia, A., Shibahara, Y., Done, S. J., Wood, S. A., et al. (2021). Therapeutic inhibition of USP9x-mediated Notch signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (38), e2101592118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101592118

Jellusova, J., and Rickert, R. C. (2016). The PI3K pathway in B cell metabolism. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 51 (5), 359–378. doi:10.1080/10409238.2016.1215288

Jia, J., Wang, F., Bhujabal, Z., Peters, R., Mudd, M., Duque, T., et al. (2022). Stress granules and mTOR are regulated by membrane atg8ylation during lysosomal damage. J. Cell Biol. 221 (11), e202207091. doi:10.1083/jcb.202207091

Jolly, L. A., Taylor, V., and Wood, S. A. (2009). USP9X enhances the polarity and self-renewal of embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors. Mol. Biol. Cell 20 (7), 2015–2029. doi:10.1091/mbc.e08-06-0596

Kennedy, J. C., Khabibullin, D., and Henske, E. P. (2016). Mechanisms of pulmonary cyst pathogenesis in Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: the stretch hypothesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 52, 47–52. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.014

Kim, J., Kundu, M., Viollet, B., and Guan, K. L. (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13 (2), 132–141. doi:10.1038/ncb2152

Kim, J., Yang, G., Kim, Y., Kim, J., and Ha, J. (2016). AMPK activators: mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp. Mol. Med. 48 (4), e224. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.16

Kumariya, S., Ubba, V., Jha, R. K., and Gayen, J. R. (2021). Autophagy in ovary and polycystic ovary syndrome: role, dispute and future perspective. Autophagy 17 (10), 2706–2733. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1938914

Kwiatkowski, D. J., and Manning, B. D. (2005). Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 (2), R251–R258. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi260

Lawrence, R. E., Fromm, S. A., Fu, Y., Yokom, A. L., Kim, D. J., Thelen, A. M., et al. (2019). Structural mechanism of a Rag GTPase activation checkpoint by the lysosomal folliculin complex. Science 366 (6468), 971–977. doi:10.1126/science.aax0364

Linehan, W. M., Srinivasan, R., and Schmidt, L. S. (2010). The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Urol. 7 (5), 277–285. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2010.47

Liubomirski, Y., Lerrer, S., Meshel, T., Morein, D., Rubinstein-Achiasaf, L., Sprinzak, D., et al. (2019). Notch-mediated tumor-stroma-inflammation networks promote invasive properties and CXCL8 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 10, 804. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00804

Lushchak, O., Strilbytska, O., Piskovatska, V., Storey, K. B., Koliada, A., and Vaiserman, A. (2017). The role of the TOR pathway in mediating the link between nutrition and longevity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 164, 127–138. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2017.03.005

MacDonald, A. F., Bettaieb, A., Donohoe, D. R., Alani, D. S., Han, A., Zhao, Y., et al. (2018). Concurrent regulation of LKB1 and CaMKK2 in the activation of AMPK in castrate-resistant prostate cancer by a well-defined polyherbal mixture with anticancer properties. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18 (1), 188. doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2255-0

Malik, N., Ferreira, B. I., Hollstein, P. E., Curtis, S. D., Trefts, E., Weiser Novak, S., et al. (2023). Induction of lysosomal and mitochondrial biogenesis by AMPK phosphorylation of FNIP1. Science 380 (6642), eabj5559. doi:10.1126/science.abj5559

Manford, A. G., Mena, E. L., Shih, K. Y., Gee, C. L., McMinimy, R., Martínez-González, B., et al. (2021). Structural basis and regulation of the reductive stress response. Cell 184 (21), 5375–5390.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.002

Manford, A. G., Rodríguez-Pérez, F., Shih, K. Y., Shi, Z., Berdan, C. A., Choe, M., et al. (2020). A cellular mechanism to detect and alleviate reductive stress. Cell 183 (1), 46–61. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.034

Marchesan, E., Nardin, A., Mauri, S., Bernardo, G., Chander, V., Di Paola, S., et al. (2024). Activation of Ca(2+) phosphatase Calcineurin regulates Parkin translocation to mitochondria and mitophagy in flies. Cell Death Differ. 31 (2), 217–238. doi:10.1038/s41418-023-01251-9

Meng, J., and Ferguson, S. M. (2018). GATOR1-dependent recruitment of FLCN-FNIP to lysosomes coordinates Rag GTPase heterodimer nucleotide status in response to amino acids. J. Cell Biol. 217 (8), 2765–2776. doi:10.1083/jcb.201712177

Meyer, J. N., Leuthner, T. C., and Luz, A. L. (2017). Mitochondrial fusion, fission, and mitochondrial toxicity. Toxicology 391, 42–53. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2017.07.019

Mo, H. Y., Son, H. J., Choi, E. J., Yoo, N. J., An, C. H., and Lee, S. H. (2019). Somatic mutations of candidate tumor suppressor genes folliculin-interacting proteins FNIP1 and FNIP2 in gastric and colon cancers. Pathol. Res. Pract. 215 (11), 152646. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2019.152646

Moreno-Corona, N., Valagussa, A., Thouenon, R., Fischer, A., and Kracker, S. (2023). A case report of folliculin-interacting protein 1 deficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 43 (8), 1751–1753. doi:10.1007/s10875-023-01559-8

Nakamura, S., Akayama, S., and Yoshimori, T. (2021). Autophagy-independent function of lipidated LC3 essential for TFEB activation during the lysosomal damage responses. Autophagy 17 (2), 581–583. doi:10.1080/15548627.2020.1846292

Nguyen, T. N., Sawa-Makarska, J., Khuu, G., Lam, W. K., Adriaenssens, E., Fracchiolla, D., et al. (2023). Unconventional initiation of PINK1/Parkin mitophagy by Optineurin. Mol. Cell 83 (10), 1693–1709.e9. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2023.04.021

Pan, Y., Nishida, Y., Wang, M., and Verdin, E. (2012). Metabolic regulation, mitochondria and the life-prolonging effect of rapamycin: a mini-review. Gerontology 58 (6), 524–530. doi:10.1159/000342204

Paquette, M., El-Houjeiri, L., L, C. Z., Puustinen, P., Blanchette, P., Jeong, H., et al. (2021). AMPK-dependent phosphorylation is required for transcriptional activation of TFEB and TFE3. Autophagy 17 (12), 3957–3975. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1898748

Parmar, U. M., Jalgaonkar, M. P., Kulkarni, Y. A., and Oza, M. J. (2022). Autophagy-nutrient sensing pathways in diabetic complications. Pharmacol. Res. 184, 106408. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106408

Paul, J. W., Muratcioğlu, S., and Kuriyan, J. (2023). A fluorescence-based sensor for calibrated measurement of protein kinase stability in live cells. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2023.12.07.570636

Perera, R. M., Di Malta, C., and Ballabio, A. (2019). MiT/TFE family of transcription factors, lysosomes, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 3, 203–222. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030518-055835

Petit, C. S., Roczniak-Ferguson, A., and Ferguson, S. M. (2013). Recruitment of folliculin to lysosomes supports the amino acid-dependent activation of Rag GTPases. J. Cell Biol. 202 (7), 1107–1122. doi:10.1083/jcb.201307084

Premarathne, S., Murtaza, M., Matigian, N., Jolly, L. A., and Wood, S. A. (2017). Loss of Usp9x disrupts cell adhesion, and components of the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways in neural progenitors. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 8109. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05451-5

Puertollano, R., Ferguson, S. M., Brugarolas, J., and Ballabio, A. (2018). The complex relationship between TFEB transcription factor phosphorylation and subcellular localization. Embo J. 37 (11), e98804. doi:10.15252/embj.201798804

Rallis, C., Codlin, S., and Bähler, J. (2013). TORC1 signaling inhibition by rapamycin and caffeine affect lifespan, global gene expression, and cell proliferation of fission yeast. Aging Cell 12 (4), 563–573. doi:10.1111/acel.12080

Ramírez, J. A., Iwata, T., Park, H., Tsang, M., Kang, J., Cui, K., et al. (2019). Folliculin interacting protein 1 maintains metabolic homeostasis during B cell development by modulating AMPK, mTORC1, and TFE3. J. Immunol. 203 (11), 2899–2908. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1900395

Ramirez Reyes, J. M. J., Cuesta, R., and Pause, A. (2021). Folliculin: a regulator of transcription through AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 667311. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.667311

Ren, S., Luo, C., Wang, Y., Wei, Y., Ou, Y., Yuan, J., et al. (2021). Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome with rare unclassified renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Med. Baltim. 100 (51), e28380. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000028380

Reyes, N. L., Banks, G. B., Tsang, M., Margineantu, D., Gu, H., Djukovic, D., et al. (2015). Fnip1 regulates skeletal muscle fiber type specification, fatigue resistance, and susceptibility to muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112 (2), 424–429. doi:10.1073/pnas.1413021112

Rezvan, A., Romain, G., Fathi, M., Heeke, D., Martinez-Paniagua, M., An, X., et al. (2024). Identification of a clinically efficacious CAR T cell subset in diffuse large B cell lymphoma by dynamic multidimensional single-cell profiling. Nat. Cancer 5 (7), 1010–1023. doi:10.1038/s43018-024-00768-3

Roczniak-Ferguson, A., Petit, C. S., Froehlich, F., Qian, S., Ky, J., Angarola, B., et al. (2012). The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci. Signal 5 (228), ra42. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2002790

Ross, F. A., Hawley, S. A., Russell, F. M., Goodman, N., and Hardie, D. G. (2023). Frequent loss-of-function mutations in the AMPK-α2 catalytic subunit suggest a tumour suppressor role in human skin cancers. Biochem. J. 480 (23), 1951–1968. doi:10.1042/bcj20230380

Rowe, G. C., Raghuram, S., Jang, C., Nagy, J. A., Patten, I. S., Goyal, A., et al. (2014). PGC-1α induces SPP1 to activate macrophages and orchestrate functional angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Circ. Res. 115 (5), 504–517. doi:10.1161/circresaha.115.303829

Russell, F. M., and Hardie, D. G. (2020). AMP-activated protein kinase: do we need activators or inhibitors to treat or prevent cancer? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (1), 186. doi:10.3390/ijms22010186

Saettini, F., Poli, C., Vengoechea, J., Bonanomi, S., Orellana, J. C., Fazio, G., et al. (2021). Absent B cells, agammaglobulinemia, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in folliculin-interacting protein 1 deficiency. Blood 137 (4), 493–499. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006441

Schmidt, L. S. (2013). Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: from gene discovery to molecularly targeted therapies. Fam. Cancer 12 (3), 357–364. doi:10.1007/s10689-012-9574-y

Schmidt, L. S., and Linehan, W. M. (2015). Clinical features, genetics and potential therapeutic approaches for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 3 (1), 15–29. doi:10.1517/21678707.2014.987124

Schmidt, L. S., and Linehan, W. M. (2018). FLCN: the causative gene for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Gene 640, 28–42. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2017.09.044

Settembre, C., Di Malta, C., Polito, V. A., Garcia Arencibia, M., Vetrini, F., Erdin, S., et al. (2011). TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science 332 (6036), 1429–1433. doi:10.1126/science.1204592

Settembre, C., Zoncu, R., Medina, D. L., Vetrini, F., Erdin, S., Erdin, S., et al. (2012). A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. Embo J. 31 (5), 1095–1108. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.32

Shariq, M., Khan, M. F., Raj, R., Ahsan, N., and Kumar, P. (2024). PRKAA2, MTOR, and TFEB in the regulation of lysosomal damage response and autophagy. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 102 (3), 287–311. doi:10.1007/s00109-023-02411-7

Shen, K., Rogala, K. B., Chou, H. T., Huang, R. K., Yu, Z., and Sabatini, D. M. (2019). Cryo-EM structure of the human FLCN-FNIP2-Rag-ragulator complex. Cell 179 (6), 1319–1329. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.036

Siggs, O. M., Stockenhuber, A., Deobagkar-Lele, M., Bull, K. R., Crockford, T. L., Kingston, B. L., et al. (2016). Mutation of Fnip1 is associated with B-cell deficiency, cardiomyopathy, and elevated AMPK activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113 (26), E3706–E3715. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607592113

Skidmore, Z. L., Kunisaki, J., Lin, Y., Cotto, K. C., Barnell, E. K., Hundal, J., et al. (2022). Genomic and transcriptomic somatic alterations of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic livers. Cancer Genet. 264-265, 90–99. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2022.04.002

Sopariwala, D. H., Likhite, N., Pei, G., Haroon, F., Lin, L., Yadav, V., et al. (2021). Estrogen-related receptor α is involved in angiogenesis and skeletal muscle revascularization in hindlimb ischemia. Faseb J. 35 (5), e21480. doi:10.1096/fj.202001794RR

Sun, K., Jing, X., Guo, J., Yao, X., and Guo, F. (2021). Mitophagy in degenerative joint diseases. Autophagy 17 (9), 2082–2092. doi:10.1080/15548627.2020.1822097

Sun, Z., Yang, L., Kiram, A., Yang, J., Yang, Z., Xiao, L., et al. (2023). FNIP1 abrogation promotes functional revascularization of ischemic skeletal muscle by driving macrophage recruitment. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 7136. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42690-9

Takagi, Y., Kobayashi, T., Shiono, M., Wang, L., Piao, X., Sun, G., et al. (2008). Interaction of folliculin (Birt-Hogg-Dubé gene product) with a novel Fnip1-like (FnipL/Fnip2) protein. Oncogene 27 (40), 5339–5347. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.261

Terešak, P., Lapao, A., Subic, N., Boya, P., Elazar, Z., and Simonsen, A. (2022). Regulation of PRKN-independent mitophagy. Autophagy 18 (1), 24–39. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1888244

Trefts, E., and Shaw, R. J. (2021). AMPK: restoring metabolic homeostasis over space and time. Mol. Cell 81 (18), 3677–3690. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.015

Tsai, J. M., Nowak, R. P., Ebert, B. L., and Fischer, E. S. (2024). Targeted protein degradation: from mechanisms to clinic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25 (9), 740–757. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00729-9

Tsun, Z. Y., Bar-Peled, L., Chantranupong, L., Zoncu, R., Wang, T., Kim, C., et al. (2013). The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol. Cell 52 (4), 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.016

Tudorica, D. A., Basak, B., Puerta Cordova, A. S., Khuu, G., Rose, K., Lazarou, M., et al. (2024). A RAB7A phosphoswitch coordinates Rubicon Homology protein regulation of Parkin-dependent mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 223 (7), e202309015. doi:10.1083/jcb.202309015

Ulaş, S., Naiboğlu, S., Özyilmaz, İ., Öztürk Demir, A. G., Turan, I., Yuzkan, S., et al. (2024). Clinical and immunologic features of a patient with homozygous FNIP1 variant. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 46 (6), e472–e475. doi:10.1097/mph.0000000000002862

Vega-Rubin-de-Celis, S., Peña-Llopis, S., Konda, M., and Brugarolas, J. (2017). Multistep regulation of TFEB by MTORC1. Autophagy 13 (3), 464–472. doi:10.1080/15548627.2016.1271514

Wang, X., and Jia, J. (2023). Magnolol improves Alzheimer's disease-like pathologies and cognitive decline by promoting autophagy through activation of the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114473. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114473

Wang, X., Tan, X., Zhang, J., Wu, J., and Shi, H. (2023). The emerging roles of MAPK-AMPK in ferroptosis regulatory network. Cell Commun. Signal 21 (1), 200. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01170-9

Wang, X. M., Mannan, R., Zhang, Y., Chinnaiyan, A., Rangaswamy, R., Chugh, S., et al. (2024). Hybrid oncocytic tumors (HOTs) in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome patients-A tale of two cities: sequencing analysis reveals dual lineage markers capturing the 2 cellular populations of HOT. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 48 (2), 163–173. doi:10.1097/pas.0000000000002152