- 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

HDAC11 is an epigenetic repressor of gene transcription, acting through its deacetylase activity to remove functional acetyl groups from the lysine residues of histones at genomic loci. It has been implicated in the regulation of different immune responses, metabolic activities, as well as cell cycle progression. Recent studies have also shed lights on the impact of HDAC11 on myogenic differentiation and muscle development, indicating that HDAC11 is important for histone deacetylation at the promoters to inhibit transcription of cell cycle related genes, thereby permitting myogenic activation at the onset of myoblast differentiation. Interestingly, the upstream networks of HDAC11 target genes are mainly associated with cell cycle regulators and the acetylation of histones at the HDAC11 target promoters appears to be residue specific. As such, selective inhibition, or activation of HDAC11 presents a potential therapeutic approach for targeting distinct epigenetic pathways in clinical applications.

Introduction

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are evolutionarily conserved and often found at transcriptionally inactive loci and heterochromatins (Vaquero et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009). They act through their deacetylase activity to remove functional acetyl groups from the lysine residues of histones as well as non-histone proteins. A total of 18 HDACs have been found in mammals, classified as the Zn2+-dependent class I, II, IV, and the NAD+-dependent class III HDACs (Park and Kim, 2020). HDAC11 is the sole member of the class IV HDACs (Gao et al., 2002). Besides the deacetylase property, it also contains potent fatty deacylation and lysine demyristoylation activities (Kutil et al., 2018; Moreno-Yruela et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019; Bagchi et al., 2022). While HDAC inhibition has been employed as a therapeutic approach for cancer treatments (Bondarev et al., 2021), increasing evidence suggests that HDACs can also be targeted selectively for the treatment of other diseases, including muscle related diseases.

HDAC11 in immune response

HDAC11 has been implicated in the regulation of different immune cells and cellular responses. It represses IL-10 gene expression through a direct control of promoter accessibility in antigen-presenting cells (Villagra et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2014). Upregulation of HDAC11 expression through the inhibition of microRNA-145 by type I interferon signaling decreases innate IL-10 production in macrophages (Lin et al., 2013). HDAC11 is also a negative regulator of the expansion and function of myeloid derived suppressor cells (Sahakian et al., 2015) and affects myeloid differentiation such as chemokine and cytokine expression during neutrophil maturation, migration, and phagocytic function (Sahakian et al., 2017). It plays a role in T cell development and tumor biology (Buglio et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2017; Woods et al., 2017; Bora-Singhal et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Interestingly, the deacylation activity of HDAC11 has also been implicated in the regulation of type I interferon signaling (Cao et al., 2019).

HDAC11 in metabolic pathway

HDAC11 has been shown to play a regulatory role in metabolic homeostasis. For example, Hdac11 knockout mice exhibit better metabolic health and less susceptible to high-fat diet induced weight gain (Sun et al., 2018). Ablation of Hdac11 improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, in addition to boosts energy expenditure though promoting thermogenic capacity (Sun et al., 2018). The benefit of Hdac11 deficiency is associated with an increased uncoupling protein one expression and an elevation of brown adipose tissue abundance and activity, but beiging of white adipose tissue (Bagchi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018). Mechanistically, Knockdown of Hdac11 promotes brown adipocyte differentiation and attenuates the suppressive role of Hdac11 on thermogenic program of adipose tissue that is dependent on its physical association with BRD2, a bromodomain and extraterminal acetyl-histone-binding protein (Bagchi et al., 2018). In addition, Hdac11 has been implicated in adrenergic signaling pathway (Bagchi et al., 2022). In skeletal muscle, Hdac11 depletion increases muscle strength and fatigue resistance through AMP-activated protein kinase-acetyl-CoA carboxylase signaling pathway to enhance mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation (Hurtado et al., 2021).

HDAC11 in cell cycle regulation

Chromatin reorganization is important for the processes of DNA replication and cell cycle progression. HDAC11 physically interacts with and deacetylates replication licensing factor Cdt1 (Glozak and Seto, 2009). It is upregulated in several models of renal fibrosis, promoting pro-fibrogenic response likely through the repression of Kruppel-like factor 15 gene expression (Mao et al., 2020). HDAC11 is also overexpressed in several carcinomas, and depletion of HDAC11 decreases cancer cell metabolic activity and viability through apoptosis (Deubzer et al., 2013). A group of cell cycle promoting genes regulated by HDAC11, essential for tumor cell viability, has been identified in neuroblastoma related models, suggesting a regulatory role for HDAC11 in mitotic cell cycle progression and cell division (Thole et al., 2017). In fibroblasts, the level of HDAC11 is low in cycling cells but high in quiescence cell, and overexpression of HDAC11 inhibits cell cycle progression of both transformed and nontransformed cells (Bagui et al., 2013). Likewise, depletion of Hdac11 upregulates cell cycle related genes in skeletal myoblasts (Byun et al., 2017; Núñez-Álvarez et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the molecular pathways by which HDAC11 affects cell cycle progression in myogenic differentiation remains unclear.

HDACs in skeletal muscle development

Adult muscle regeneration is an important physiological process to maintain muscle homeostasis and repair the muscle following injury. The regenerative responses are mediated by resident muscle stem cells (MuSCs) or the satellite cells (Cornelison et al., 2001; Seale et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2013), a population of stem cells found between the myofiber sarcolemma and the basal lamina. Characterized by the expression of the Paired-box protein 7 (PAX7) (Mauro, 1961; Dumont et al., 2015), MuSCs are quiescent in healthy muscle, become activated to proliferate and differentiate into new myofibers upon muscle injury or exercise, but can also revert to the quiescent state to maintain the MuSC pool (self-renewal) for future regeneration (Giordani et al., 2018). Mechanistically, muscle regeneration is a multistage event, consisting of myoblast proliferation, differentiation, and myocyte fusion, which is tightly controlled by different myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), including MyoD and myogenin (Tapscott, 2005). On a molecular level. myogenic differentiation begins with the downregulation of PAX7 and upregulation of MRFs which coordinate the commitment, terminal differentiation, and fusion into myofibers (Berkes and Tapscott, 2005; Blais et al., 2005; le Grand and Rudnicki, 2007; Chang and Rudnicki, 2014; Conerly et al., 2016). In early myoblast differentiation, residue-specific histone acetylation signifies the regulatory loci concerted by MRFs and histone acetyltransferase (HAT) p300 (Hamed et al., 2013; 2017; Khilji et al., 2018; 2020; 2021).

On the other hand, many studies have demonstrated the impact of HDACs on muscle development. Deacetylation of MyoD by HDAC1 silences MyoD-mediated gene expression (Mal, 2001; Mal and Harter, 2003). The Snai1-HDAC1/2 repressive complex excludes MyoD from differentiation-specific regulatory elements in proliferating myoblasts, preventing the entry into myogenic differentiation (Soleimani et al., 2012). HDAC4 interacts with the transcription factor MEF2 and deacetylates myosin heavy chain, exerting a regulatory role in both myogenic differentiation and muscle homeostasis (Lu et al., 2000; Marroncelli et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2019). In addition, HDACs are required for heterochromatin reorganization during terminal myoblast differentiation (Terranova et al., 2005). Interestingly, it has been shown that HDAC11 is expendable for muscle stem cell formation and adult muscle growth, while knockout of Hdac11 in mice encourages muscle regeneration following muscle injury (Byun et al., 2017; Núñez-Álvarez et al., 2021).

HDAC11 in early myoblast differentiation

HDAC function is required for histone deacetylation to suppress target gene expression which is essential for stem cell fate transition. In early myoblast differentiation, Hdac11 is the most significantly upregulated HDACs and change in residue-specific histone acetylation occurs at the promoters of differentially expressed genes (Li et al., 2023). In addition, the Hdac11 gene locus is controlled by histone acetyltransferase (HAT) p300 and the muscle master regulator MyoD (Li et al., 2023), and ablation of Hdac11 in mice results in persistent myoblast proliferation in culture, albeit the induction signal for differentiation (Núñez-Álvarez et al., 2021).

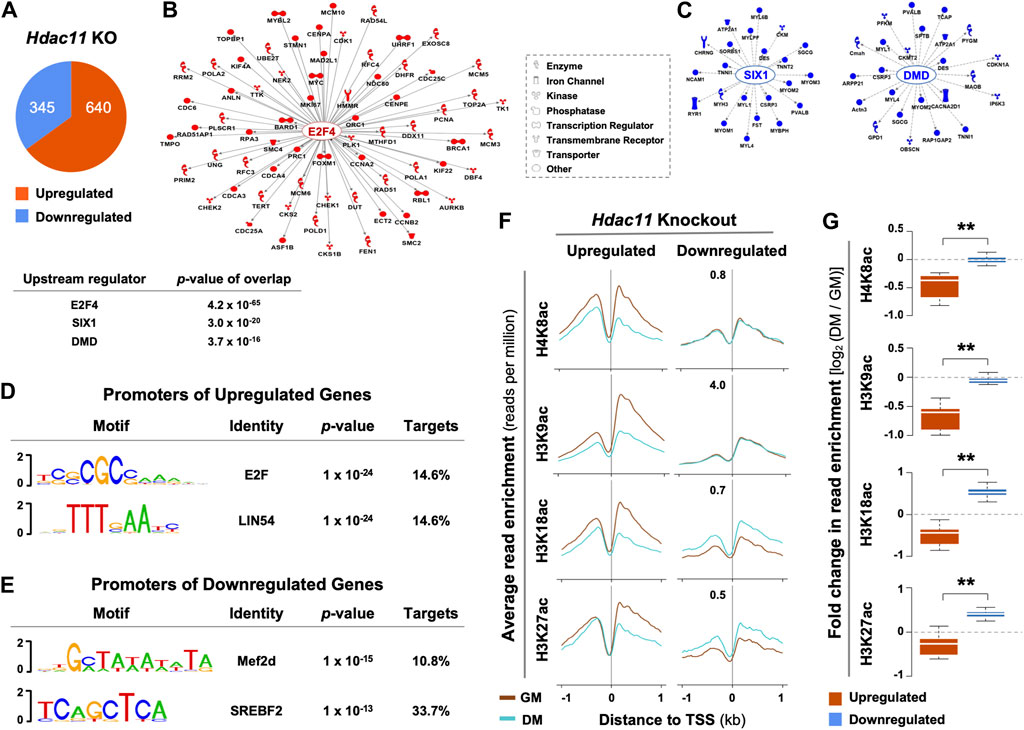

The effects of Hdac11 on myoblast proliferation appears to be mediated at the level of gene expression. Based on the public deposited RNA-seq data of the primary myoblasts isolated from the Hdac11 knockout mice (Núñez-Álvarez et al., 2021), 640 genes were significantly upregulated by over 1.5-fold when compared to the wild-type controls, while 345 genes were downregulated (Figure 1A). Interestingly, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) identified E2F4 as a prominent upstream regulator for 70 upregulated genes that are related to cell cycle and DNA replication processes (Figure 1B). On the other hand, SIX1 and DMD were the top two upstream regulators associated with downregulated genes that are mostly attributed to muscle system process in a smaller gene group (Figure 1C). Additionally, consensus binding sites for E2F and LIN54, known cell cycle regulators (Takahashi et al., 2000; Marceau et al., 2016), were found to be the top two binding motifs found in the promoters of genes upregulated by Hdac11 ablation. (Figure 1D). In contrast, the top two motifs at the promoters of downregulated genes were best matched for Mef2d and SREBF binding (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Upstream regulatory pathways and histone acetylation at the promoters of genes impacted by Hdac11 ablation. (A) Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment (HOMER) was used to annotate genes which were significantly upregulated or downregulated upon Hdac11 knockout in mice (KO, ≥ ±1.5 absolute fold change, GSE147423). (B) QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis was used for the upregulated genes as categorized in Panel (A). The molecular network displays direct gene interactions, and the shapes of the nodes distinguish functional gene classes. (C) Network analysis for the downregulated genes. (D) HOMER was used for motif analysis of the promoters of genes upregulated following the Hdac11 knockout. (E) Motif analysis of the promoters of genes downregulated. (F) The ngs.plot was used to visualize the average enrichment profiles of histone acetylation across the transcription start site (TSS, ±1 kb, GSE94558) in wild type differentiating (DM) or proliferating (GM) myoblasts, corresponding to the genes up- or downregulated upon the Hdac11 knockout. (G) Quantification of log2-fold change in histone acetylation signals as in panel C (Wilcoxon rank sum test, **p < 2.2 × 10−16).

Based on the deposited histone acetylation ChIP-seq data from the wild type myoblasts (GSE94558), H4K8, H3K9, H3K18 and H3K27 acetylation at the promoters of genes upregulated by Hdac11 inactivation, corresponded to a decreased profile in the wild type differentiating myoblasts compared to undifferentiated controls. Conversely, the promoters of downregulated genes correlated with an increased acetylation at H3K18 and H3K27 in the wild type differentiating myoblasts (Figures 1F, G). The fact that the promoters of genes upregulated by Hdac11 knockout were associated with decreased histone acetylation in normal myoblast differentiation supports the notion that HDAC11 deacetylates histones at these promoters to repress gene transcription.

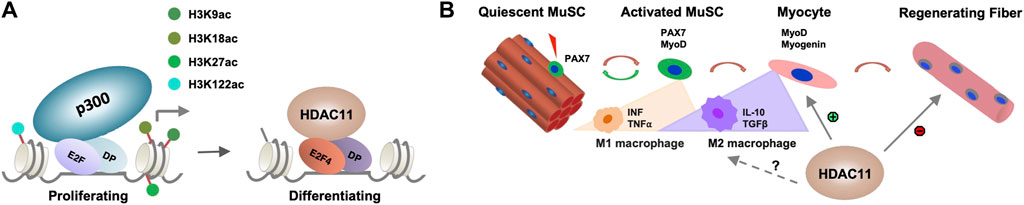

While histone deacetylation is required for switching gene programs from proliferation to differentiation, HDACs do not directly bind to the DNA regulatory elements to repress gene transcription. The E2F family of transcription factors are key cell cycle regulators and can act as either transcriptional activators or repressor depending on cellular context (Takahashi et al., 2000). E2F promoted cell cycle progression critically depends on the function of p300 HAT which is antagonized by HDACs (Morris et al., 2000). Therefore, the interplay of HDAC11 and HAT may be essential for reversible histone acetylation at the target genes to permit stem cell fate transition, in that specific cell cycle regulators are responsible for recruiting HDAC11 to suppress cell cycle progression, which is a prerequisite for the initiation of myogenic differentiation (Figure 2A). Consequently, the downregulation of myogenic expression following Hdac11 ablation, may reflect the paucity of myogenic differentiation because of persistent cell cycle activity.

Figure 2. Molecular mechanisms of HDAC11 function. (A) Role of HDAC11 in cell cycle related genes. E2F related transcription factor and their dimerization partner (DP) recruit HDAC11 to the regulatory loci associated with p300 HAT in proliferating myoblasts for histone deacetylation to permit the onset of differentiation. (B) Potential impact of HDAC11 on immune response in muscle regeneration. During muscle regeneration, the progression of MuSC proliferation to differentiation is associated with a transition of M1 to M2 macrophages which secrete distinct cytokines within the muscle tissue. HDAC11 exerts positive or negative impact on muscle regeneration depending on distinct molecular pathway evoked.

Discussion

To permit myogenic differentiation, cell cycle arrests via histone deacetylation mediated gene repression. Like many other HDACs, HDAC11 is an epigenetic repressor of gene transcription attributed to its deacetylate activity. Although the upstream regulatory networks of Hdac11 target genes are associated with cell cycle regulators in differentiating myoblasts (Figure 1), transcription factors that recruit HDAC11 to the regulatory loci and Hdac11 associated histone deacetylation in myogenic differentiation remain to be determined. Future research with integrated approach of gene specific targeting coupled with omics analyses of transcriptome and genome wide protein-DNA interaction will allow to identify novel regulatory mechanisms associated with HDAC11 function and delineate the molecular basis of HDAC and HAT interplay in reversible histone acetylation during stem cell fate transition.

In addition, MuSC fate and homeostasis are also regulated by non-muscle cells in the muscle microenvironment and different immune cells form essential components of the MuSC niche upon muscle injury (Deng et al., 2012; Dinulovic et al., 2017). The transition of M1 to M2 macrophage is particularly critical to MuSC fate transition (Forcina et al., 2020). Given the described roles for HDAC11 in the regulation of different immune responses, the impact of HDAC11 on skeletal muscle development is no doubt multifaceted, muscle metabolism and growth, MuSC fate transition, and beyond (Figure 2B). As such, delineating the positive or negative role of HDAC11 involved in distinct steps of myogenic differentiation will help develop the best strategy to selectively inhibit or activate HDAC11 for muscle regeneration and repair in muscle therapeutics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. QL: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by an Operating Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to QL (CIHR # 154278).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Yan Z. Mach for excellent assistance in bioinformatic analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bagchi, R. A., Ferguson, B. S., Stratton, M. S., Hu, T., Cavasin, M. A., Sun, L., et al. (2018). HDAC11 suppresses the thermogenic program of adipose tissue via BRD2. JCI Insight 3, e120159. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.120159

Bagchi, R. A., Robinson, E. L., Hu, T., Cao, J., Hong, J. Y., Tharp, C. A., et al. (2022). Reversible lysine fatty acylation of an anchoring protein mediates adipocyte adrenergic signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2119678119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2119678119

Bagui, T. K., Sharma, S. S., Ma, L., and Pledger, W. J. (2013). Proliferative status regulates HDAC11 mRNA abundance in nontransformed fibroblasts. Cell Cycle 12, 3433–3441. doi:10.4161/cc.26433

Berkes, C. A., and Tapscott, S. J. (2005). MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 585–595. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.006

Blais, A., Tsikitis, M., Acosta-Alvear, D., Sharan, R., Kluger, Y., and Dynlacht, B. D. (2005). An initial blueprint for myogenic differentiation. Genes Dev. 19, 553–569. doi:10.1101/GAD.1281105

Bondarev, A. D., Attwood, M. M., Jonsson, J., Chubarev, V. N., Tarasov, V. V., and Schiöth, H. B. (2021). Recent developments of HDAC inhibitors: emerging indications and novel molecules. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 87, 4577–4597. doi:10.1111/bcp.14889

Bora-Singhal, N., Mohankumar, D., Saha, B., Colin, C. M., Lee, J. Y., Martin, M. W., et al. (2020). Novel HDAC11 inhibitors suppress lung adenocarcinoma stem cell self-renewal and overcome drug resistance by suppressing Sox2. Sci. Rep. 10, 4722. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61295-6

Buglio, D., Khaskhely, N. M., Voo, K. S., Martinez-Valdez, H., Liu, Y.-J., and Younes, A. (2011). HDAC11 plays an essential role in regulating OX40 ligand expression in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 117, 2910–2917. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-08-303701

Byun, S. K., An, T. H., Son, M. J., Lee, D. S., Kang, H. S., Lee, E.-W., et al. (2017). HDAC11 inhibits myoblast differentiation through repression of MyoD-dependent transcription. Mol. Cells 40, 667–676. doi:10.14348/molcells.2017.0116

Cao, J., Sun, L., Aramsangtienchai, P., Spiegelman, N. A., Zhang, X., Huang, W., et al. (2019). HDAC11 regulates type I interferon signaling through defatty-acylation of SHMT2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 5487–5492. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815365116

Chang, N. C., and Rudnicki, M. a. (2014) Satellite cells: the architects of skeletal muscle. 1st Edn. Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-416022-4.00006-8

Cheng, F., Lienlaf, M., Perez-Villarroel, P., Wang, H.-W., Lee, C., Woan, K., et al. (2014). Divergent roles of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) and histone deacetylase 11 (HDAC11) on the transcriptional regulation of IL10 in antigen presenting cells. Mol. Immunol. 60, 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2014.02.019

Conerly, M. L., Yao, Z., Zhong, J. W., Groudine, M., and Tapscott, S. J. (2016). Distinct activities of Myf5 and MyoD indicate separate roles in skeletal muscle lineage specification and differentiation. Dev. Cell 36, 375–385. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.01.021

Cornelison, D. D., Filla, M. S., Stanley, H. M., Rapraeger, a C., and Olwin, B. B. (2001). Syndecan-3 and syndecan-4 specifically mark skeletal muscle satellite cells and are implicated in satellite cell maintenance and muscle regeneration. Dev. Biol. 239, 79–94. doi:10.1006/dbio.2001.0416

Deng, B., Wehling-Henricks, M., Villalta, S. A., Wang, Y., and Tidball, J. G. (2012). IL-10 triggers changes in macrophage phenotype that promote muscle growth and regeneration. J. Immunol. 189, 3669–3680. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103180

Deubzer, H. E., Schier, M. C., Oehme, I., Lodrini, M., Haendler, B., Sommer, A., et al. (2013). HDAC11 is a novel drug target in carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 132, 2200–2208. doi:10.1002/ijc.27876

Dinulovic, I., Furrer, R., and Handschin, C. (2017). Plasticity of the muscle stem cell microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1041, 141–169. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69194-7_8

Dumont, N. A., Wang, Y. X., and Rudnicki, M. A. (2015). Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating satellite cell function. Development 142, 1572–1581. doi:10.1242/dev.114223

Forcina, L., Cosentino, M., and Musarò, A. (2020). Mechanisms regulating muscle regeneration: insights into the interrelated and time-dependent phases of tissue healing. Cells 9, 1297. doi:10.3390/cells9051297

Gao, L., Cueto, M. A., Asselbergs, F., and Atadja, P. (2002). Cloning and functional characterization of HDAC11, a novel member of the human histone deacetylase family. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25748–25755. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111871200

Giordani, L., Parisi, A., and le Grand, F. (2018). Satellite cell self-renewal. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 126, 177–203. doi:10.1016/BS.CTDB.2017.08.001

Glozak, M. A., and Seto, E. (2009). Acetylation/deacetylation modulates the stability of DNA replication licensing factor Cdt1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11446–11453. doi:10.1074/jbc.M809394200

Grand, F., and Rudnicki, M. A. (2007). Skeletal muscle satellite cells and adult myogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 628–633. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.012

Hamed, M., Khilji, S., Chen, J., and Li, Q. (2013). Stepwise acetyltransferase association and histone acetylation at the Myod1 locus during myogenic differentiation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2390. doi:10.1038/srep02390

Hamed, M., Khilji, S., Dixon, K., Blais, A., Ioshikhes, I., Chen, J., et al. (2017). Insights into interplay between rexinoid signaling and myogenic regulatory factor-associated chromatin state in myogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 11236–11248. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx800

Huang, J., Wang, L., Dahiya, S., Beier, U. H., Han, R., Samanta, A., et al. (2017). Histone/protein deacetylase 11 targeting promotes Foxp3+ Treg function. Sci. Rep. 7, 8626. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09211-3

Hurtado, E., Núñez-Álvarez, Y., Muñoz, M., Gutiérrez-Caballero, C., Casas, J., Pendás, A. M., et al. (2021). HDAC11 is a novel regulator of fatty acid oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle. FEBS J. 288, 902–919. doi:10.1111/febs.15456

Khilji, S., Hamed, M., Chen, J., and Li, Q. (2018). Loci-specific histone acetylation profiles associated with transcriptional coactivator p300 during early myoblast differentiation. Epigenetics 13, 642–654. doi:10.1080/15592294.2018.1489659

Khilji, S., Hamed, M., Chen, J., and Li, Q. (2020). Dissecting myogenin-mediated retinoid X receptor signaling in myogenic differentiation. Commun. Biol. 3, 315. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-1043-9

Khilji, S., Li, Y., Chen, J., and Li, Q. (2021). Multi-omics approach to dissect the mechanisms of rexinoid signaling in myoblast differentiation. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 746513. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.746513

Kutil, Z., Novakova, Z., Meleshin, M., Mikesova, J., Schutkowski, M., and Barinka, C. (2018). Histone deacetylase 11 is a fatty-acid deacylase. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 685–693. doi:10.1021/acschembio.7b00942

Li, Q., Mach, Y. Z., Hamed, M., Khilji, S., and Chen, J. (2023). Regulation of HDAC11 gene expression in early myogenic differentiation. PeerJ 11, e15961. doi:10.7717/peerj.15961

Lin, L., Hou, J., Ma, F., Wang, P., Liu, X., Li, N., et al. (2013). Type I IFN inhibits innate IL-10 production in macrophages through histone deacetylase 11 by downregulating microRNA-145. J. Immunol. 191, 3896–3904. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203450

Lu, J., McKinsey, T. A., Zhang, C.-L., and Olson, E. N. (2000). Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by association of the MEF2 transcription factor with class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell 6, 233–244. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00025-3

Luo, L., Martin, S. C., Parkington, J., Cadena, S. M., Zhu, J., Ibebunjo, C., et al. (2019). HDAC4 controls muscle homeostasis through deacetylation of myosin heavy chain, PGC-1α, and Hsc70. Cell Rep. 29, 749–763. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.023

Mal, A., and Harter, M. L. (2003). MyoD is functionally linked to the silencing of a muscle-specific regulatory gene prior to skeletal myogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 1735–1739. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437843100

Mal, A., Sturniolo, M., Schiltz, R. L., Ghosh, M. K., and Harter, M. L. (2001). A role for histone deacetylase HDAC1 in modulating the transcriptional activity of MyoD: inhibition of the myogenic program. EMBO J. 20, 1739–1753. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.7.1739

Mao, L., Liu, L., Zhang, T., Qin, H., Wu, X., and Xu, Y. (2020). Histone deacetylase 11 contributes to renal fibrosis by repressing KLF15 transcription. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 235. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00235

Marceau, A. H., Felthousen, J. G., Goetsch, P. D., Iness, A. N., Lee, H.-W., Tripathi, S. M., et al. (2016). Structural basis for LIN54 recognition of CHR elements in cell cycle-regulated promoters. Nat. Commun. 7, 12301. doi:10.1038/ncomms12301

Marroncelli, N., Bianchi, M., Bertin, M., Consalvi, S., Saccone, V., de Bardi, M., et al. (2018). HDAC4 regulates satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by targeting P21 and Sharp1 genes. Sci. Rep. 8, 3448. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21835-7

Mauro, A. (1961). Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 9, 493–495. doi:10.1083/jcb.9.2.493

Moreno-Yruela, C., Galleano, I., Madsen, A. S., and Olsen, C. A. (2018). Histone deacetylase 11 is an ε-N-myristoyllysine hydrolase. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 849–856. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.04.007

Morris, L., Allen, K. E., and La Thangue, N. B. (2000). Regulation of E2F transcription by cyclin E–Cdk2 kinase mediated through p300/CBP co-activators. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 232–239. doi:10.1038/35008660

Núñez-Álvarez, Y., Hurtado, E., Muñoz, M., García-Tuñon, I., Rech, G. E., Pluvinet, R., et al. (2021). Loss of HDAC11 accelerates skeletal muscle regeneration in mice. FEBS J. 288, 1201–1223. doi:10.1111/febs.15468

Park, S.-Y., and Kim, J.-S. (2020). A short guide to histone deacetylases including recent progress on class II enzymes. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 204–212. doi:10.1038/s12276-020-0382-4

Sahakian, E., Chen, J., Powers, J. J., Chen, X., Maharaj, K., Deng, S. L., et al. (2017). Essential role for histone deacetylase 11 (HDAC11) in neutrophil biology. J. Leukoc. Biol. 102, 475–486. doi:10.1189/jlb.1A0415-176RRR

Sahakian, E., Powers, J. J., Chen, J., Deng, S. L., Cheng, F., Distler, A., et al. (2015). Histone deacetylase 11: a novel epigenetic regulator of myeloid derived suppressor cell expansion and function. Mol. Immunol. 63, 579–585. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2014.08.002

Seale, P., Ishibashi, J., Scime, A., Rudnicki, M. A., Scimè, A., and Rudnicki, M. A. (2004). Pax7 is necessary and sufficient for the myogenic specification of CD45+:Sca1+ stem cells from injured muscle. PLoS Biol. 2, E130. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020130

Soleimani, V. D., Yin, H., Jahani-Asl, A., Ming, H., Kockx, C. E. M., van Ijcken, W. F. J., et al. (2012). Snail regulates MyoD binding-site occupancy to direct enhancer switching and differentiation-specific transcription in myogenesis. Mol. Cell 47, 457–468. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.046

Sun, L., Marin de Evsikova, C., Bian, K., Achille, A., Telles, E., Pei, H., et al. (2018). Programming and regulation of metabolic homeostasis by HDAC11. EBioMedicine 33, 157–168. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.06.025

Takahashi, Y., Rayman, J. B., and Dynlacht, B. D. (2000). Analysis of promoter binding by the E2F and pRB families in vivo: distinct E2F proteins mediate activation and repression. Genes Dev. 14, 804–816. doi:10.1101/gad.14.7.804

Tapscott, S. J. (2005). The circuitry of a master switch: myod and the regulation of skeletal muscle gene transcription. Development 132, 2685–2695. doi:10.1242/dev.01874

Terranova, R., Sauer, S., Merkenschlager, M., and Fisher, A. G. (2005). The reorganisation of constitutive heterochromatin in differentiating muscle requires HDAC activity. Exp. Cell Res. 310, 344–356. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.031

Thole, T. M., Lodrini, M., Fabian, J., Wuenschel, J., Pfeil, S., Hielscher, T., et al. (2017). Neuroblastoma cells depend on HDAC11 for mitotic cell cycle progression and survival. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2635. doi:10.1038/cddis.2017.49

Vaquero, A., Scher, M., Lee, D., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., and Reinberg, D. (2004). Human SirT1 interacts with histone H1 and promotes formation of facultative heterochromatin. Mol. Cell 16, 93–105. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.031

Villagra, A., Cheng, F., Wang, H.-W., Suarez, I., Glozak, M., Maurin, M., et al. (2009). The histone deacetylase HDAC11 regulates the expression of interleukin 10 and immune tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 10, 92–100. doi:10.1038/ni.1673

Wang, W., Ding, B., Lou, W., and Lin, S. (2020). Promoter hypomethylation and miR-145-5p downregulation- mediated HDAC11 overexpression promotes sorafenib resistance and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 724. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00724

Wang, Z., Zang, C., Cui, K., Schones, D. E., Barski, A., Peng, W., et al. (2009). Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell 138, 1019–1031. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049

Woods, D. M., Woan, K. V., Cheng, F., Sodré, A. L., Wang, D., Wu, Y., et al. (2017). T cells lacking HDAC11 have increased effector functions and mediate enhanced alloreactivity in a murine model. Blood 130, 146–155. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-08-731505

Keywords: histone acetylation, histone deacetylase, gene regulation, chromatin modification, myogenic differentiation

Citation: Chen J and Li Q (2024) Emerging role of HDAC11 in skeletal muscle biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:1368171. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2024.1368171

Received: 10 January 2024; Accepted: 07 May 2024;

Published: 27 May 2024.

Edited by:

Alejandro Villagra, Georgetown University, United StatesReviewed by:

Naseem Ahamad, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, United StatesManasa Suresh, Georgetown University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Chen and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiao Li, cWxpQHVPdHRhd2EuY2E=

Jihong Chen1

Jihong Chen1 Qiao Li

Qiao Li