94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol., 26 May 2022

Sec. Morphogenesis and Patterning

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.887987

This article is part of the Research TopicEarly Animal Development: From Fertilization to GastrulationView all 11 articles

Nodal proteins provide crucial signals for mesoderm and endoderm induction. In zebrafish embryos, the nodal genes ndr1/squint and ndr2/cyclops are implicated in mesendoderm induction. It remains elusive how ndr1 and ndr2 expression is regulated spatiotemporally. Here we investigated regulation of ndr1 and ndr2 expression using Mhwa mutants that lack the maternal dorsal determinant Hwa with deficiency in β-catenin signaling, Meomesa mutants that lack maternal Eomesodermin A (Eomesa), Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants, and the Nodal signaling inhibitor SB431542. We show that ndr1 and ndr2 expression is completely abolished in Meomesa;Mhwa mutant embryos, indicating an essential role of maternal eomesa and hwa. Hwa-activated β-catenin signaling plays a major role in activation of ndr1 expression in the dorsal blastodermal margin, while eomesa is mostly responsible for ndr1 expression in the lateroventral margin and Nodal signaling contributes to ventral expansion of the ndr1 expression domain. However, ndr2 expression mainly depends on maternal eomesa with minor or negligible contribution of maternal hwa and Nodal autoregulation. These mechanisms may help understand regulation of Nodal expression in other species.

The Nodal gene was first identified in mouse and its encoded protein belongs to a member of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) family (Zhou et al., 1993). Disruption of the mouse Nodal gene results in failure of primitive streak formation and mesoderm induction during embryonic development (Zhou et al., 1993; Conlon et al., 1994). There are three nodal genes in the zebrafish genome, ndr1/squint (sqt) (Erter et al., 1998; Rebagliati et al., 1998), ndr2/cyclops (cyc) (Rebagliati et al., 1998), and ndr3/southpaw (spaw) (Long et al., 2003). Simultaneous deficiency of zebrafish zygotic ndr1 and ndr2, which is caused by gene mutations, leads to loss of most, if not all, endodermal and mesodermal tissues (Feldman et al., 1998), indicating that these two Nodal proteins produced zygotically are mesendoderm inducers during zebrafish embryogenesis. Interestingly, ndr1 is also maternally expressed with maternal transcripts localized in the presumptive dorsal blastomeres during cleavage period (Gore and Sampath, 2002; Gore et al., 2005); it is believed that maternal ndr1 transcripts act as scaffold noncoding RNAs to spatially regulate β-catenin signaling (Lim et al., 2012). Maternal ndr1 has been shown to cooperate with extraembryonic (yolk syncytial layer) ndr1 and extraembryonic ndr2 to specify endoderm and anterior mesoderm fates (Hong et al., 2011), but it remains elusive if this function of maternal ndr1 is executed through classical Nodal signaling. The zebrafish ndr3 gene is not expressed until the completion of gastrulation, and it is required for left-right asymmetrical development after the completion of gastrulation (Long et al., 2003; Hashimoto et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016). The importance of Nodal signaling in mesendoderm induction has also been revealed in frog embryos (Jones et al., 1995; Joseph and Melton, 1997; Osada and Wright, 1999; Agius et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2000; Luxardi et al., 2010). It is now widely accepted that zygotically expressed Nodal proteins are essential for mesendoderm induction and patterning in vertebrate embryos (Schier and Shen, 2000; De Robertis and Kuroda, 2004; Tian and Meng, 2006; Zinski et al., 2018).

In frog and fish embryos, mesendoderm induction occurs during middle to late blastulation. As essential mesendoderm inducers, the expression of zygotic nodal genes is activated by maternal factors soon after midblastula transition (MBT), which happens in zebrafish embryos around 3 h postfertilization (hpf) (1 k-cell stage) (Kimmel et al., 1995). In frog blastulas, the maternal T-box transcription factor VegT activates the expression of Xenopus Nodal-related (Xnr) genes in the vegetal blastomeres and maternally regulated nuclear β-catenin in dorsal blastomeres acts in synergy with VegT to enhance Xnr genes expression so that a Nodal gradient is formed along the dorsal-ventral axis to induce and pattern the mesendoderm (Zhang et al., 1998; Kofron et al., 1999; Agius et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2000; Rex et al., 2002; Xanthos et al., 2002). In the zebrafish, ndr1 and ndr2 genes are initially activated in the dorsal blastodermal margin at about 3.3 h hpf and 3.7 hpf respectively, and their expression domains then extend throughout the blastodermal margin to induce the mesendodermal fate (Feldman et al., 1998; Rebagliati et al., 1998). β-catenin signaling plays a role in activating ndr1 and ndr2 expression in the dorsal blastodermal margin (Kelly et al., 2000; Dougan et al., 2003; Bellipanni et al., 2006). It has been recently disclosed that β-catenin signaling is activated by maternal huluwa (hwa), which encodes a transmembrane protein, in zebrafish and Xenopus blastulas (Yan et al., 2018). Maternal hwa transcripts in both species are located in the vegetal pole of the mature oocyte. Upon fertilization in Xenopus, maternal hwa transcripts shift to one side with cortical rotation and are apparently enriched in the dorsal blastomere at 2-cell stage; after fertilization in zebrafish, hwa transcripts in the vegetal pole transport to the cytoplasm in the animal pole and become ubiquitously distributed in blastulas, but Hwa protein is located in a few blastomeres in the prospective dorsal side at 2.75 hpf (Yan et al., 2018). Zebrafish Mhwa mutants are severely ventralized (Yan et al., 2018), which are similar to the most severe phenotype (Class I) in β-catenin2 deficient ichabod mutants (Kelly et al., 2000). The zebrafish T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin a (Eomesa) is maternally expressed with a vegetal-to-animal gradient distribution of transcripts during cleavage period and around MBT stages (Bruce et al., 2003). We previously demonstrate that zygotic expression of zebrafish ndr1 and ndr2 also requires Eomesa, in particular in ventral and lateral blastodermal margins, which is then assumed to be a zebrafish functional counterpart of frog VegT (Xu P. et al., 2014). It remains genetically unverified whether VegT/Eomesa and Hwa/β-catenin signaling are essential maternal factors for zygotic nodal genes expression in vertebrate embryos, and if they are, it needs to be investigated whether they differentially contribute to initiation, range and level of zygotic nodal genes expression.

Nodal proteins bind to specific receptors on the cytoplasm membrane, which recruit and phosphorylate the intracellular effectors Smad2 and Smad3 (Tian and Meng, 2006; Shen, 2007). The activated Smad2/3 (p-Smad2/3) bind to Smad4 and the formed complexes translocate into the nucleus to activate, with help of FoxH1 or/and other transcription factors, target genes expression. Studies in model animals have disclosed that nodal genes themselves contain Nodal-responsive elements (Adachi et al., 1999; Norris and Robertson, 1999; Osada et al., 2000; Fan et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2011), implying that Nodal signaling reinforces itself via positive feedback regulation. On the other hand, as diffusible proteins (Jones et al., 1996; Chen and Schier, 2002; Schier, 2009; Muller et al., 2012; Muller et al., 2013), Nodal proteins produced in one area are able to transduce the signal to neighboring areas that previously lack nodal transcripts to initiate nodal gene expression for self-propagation or relay (Meno et al., 1999; Hyde and Old, 2000; Brennan et al., 2001; Chen and Schier, 2001; Dougan et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2004; Muller et al., 2012; Xu P.-F. et al., 2014). However, it is unclear how much autoregulation of Nodal signaling adds to Nodal activity during vertebrate mesendoderm induction.

In this study, we systematically investigated spatiotemporal regulation of zygotic ndr1 and ndr2 expression during mesendoderm induction. We show that maternal Eomesa, maternal Hwa-activated β-catenin signaling, and Nodal positive self-regulation, are required, but to different degrees, for correct spatiotemporal expression of ndr1 and ndr2.

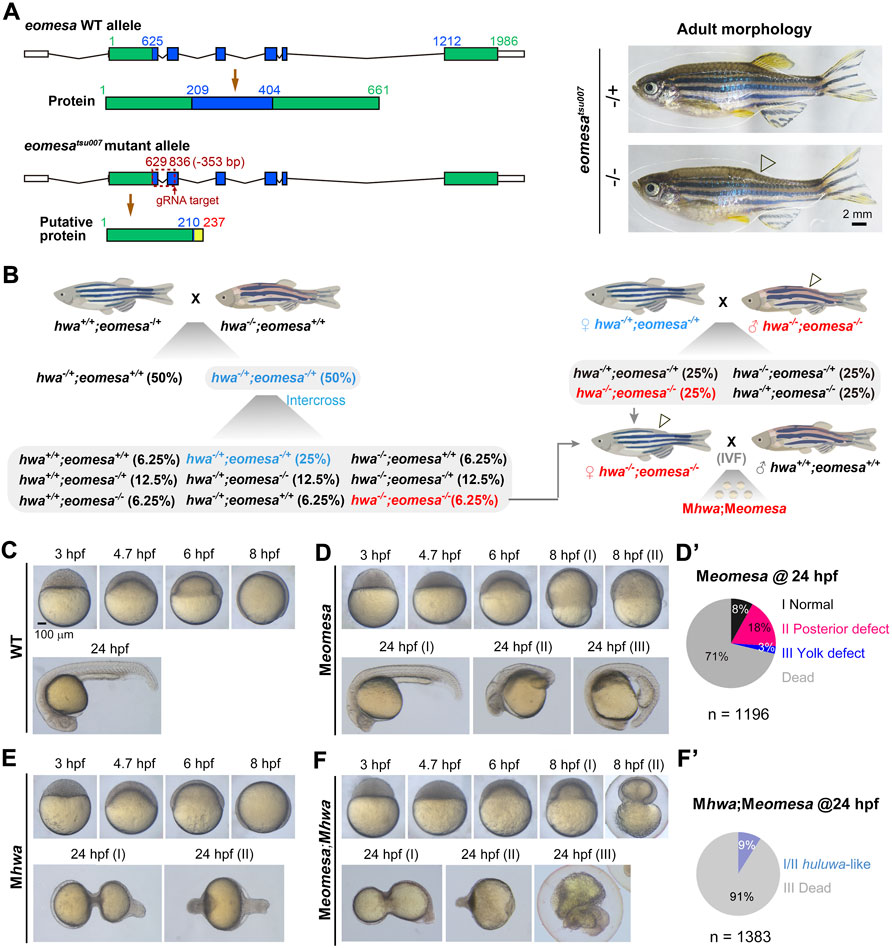

The zebrafish Tuebingen strain was used as wildtype fish and for generating mutants. The eomesatsu007 mutant line that carries a 353-bp deletion was generated by the CRISPR-Cas9 system with a gRNA (5′-ggcggaaagtgggtgacctgcgg-3′) targeting the second exon of eomesa (Figure 1A). For genotyping the eomesatsu007 mutant allele, the upper primer (5′- CTCAGCTCGATGCCCATTC-3′) and the lower primer (5′- ATACAGTCTTTGTCGGAGATG-3′) were used for PCR. Like the previously reported eomesafh105 mutant line (Du et al., 2012), zygotic eomesatsu007 (Zeomesatsu007) homozygous embryos were able to grow up to adulthood with loss of the dorsal fin (Figure 1A). The hwatsu01sm mutant line was used and its genotyping was described before (Yan et al., 2018). The eomesatsu007/+;hwatsu01sm/+ double heterozygotes were obtained by crossing eomesatsu007/+ female to hwatsu01sm/+ male. Then, Zeomesatsu007/tsu007;Zhwatsu01sm/tsu01sm double homozygous fish (i.e., Zeomesa;Zhwa double homozygotes) were obtained by intercrossing the double heterozygotes (Figure 1B). Like Zeomesa mutant female that were unable to naturally ovulate (Du et al., 2012; Xu P. et al., 2014), Zeomesa;Zhwa double homozygous female were unable to naturally ovulate and in vitro fertilization using their squeezed eggs and wildtype male-derived sperms were performed to obtain maternal double mutant (Meomesa;Mhwa) embryos (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. Phenotypes of different mutants at various stages. (A) Generation of eomesatsu007 mutant allele. Left: genomic structures and putative coding products of eomesa WT allele and tsu007 allele. The exons were colored and positions of nucleotides and amino acids were indicated. The mutant allele carries a 353-bp deletion. Right: morphology of eomesa+/tsu007 (heterozygote) and eomesatsu007/tsu007 (zygotic mutant) adults. Note that the posterior dorsal fin (indicated by an hollow arrowhead) is absent in mutant adult. (B) Scheme of generation of Mhwa;Meomesa double mutants. Zygotic genotypes were indicated. Zhwa−/−;Zeomesa−/− homozygous female adults could not ovulate naturally, and eggs squeezed from these fish were used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) using sperms squeezed from wildtype males (Zhwa+/+;Zeomesa+/+). (C) Wildtype (WT) embryos at indicated stages. (D,D’) Meomesa mutants. Mutant embryos exhibited variable phenotypes at 8 hpf and 24 hpf, and the ratios of 24-hpf mutants categorized into different classes (I-III), which were derived from several homozygous females, were shown in (D’). (E) Mhwa mutants at indicated stages. (F,F’) Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants. The ratios of embryos with different phenotypes at 24 hpf were shown in (F’). Embryos were laterally positioned when the dorsal or tail was recognizable. The scale bar in (C) was also applied to (D–F).

Embryos were maintained in Holtfreter’s water at 28.5°C. Developmental stages of WT embryos were determined as described before (Kimmel et al., 1995) while those of mutants were indirectly judged by developmental time matching to WT embryos in the same conditions. Embryo treatment with SB431542 (SB) were performed as described before (Sun et al., 2006). Briefly, One-cell stage embryos of different mutant or WT lines were incubated in Holtfreter’s water with addition of freshly made SB to a final concentration of 50 μM in a dish and then harvested for observation or assays at desired stages. All experiments were approved by Tsinghua University Animal Care and Use Committee.

The plasmids pCS2-eomesa-Myc (Bruce et al., 2003) and pCS2-hwa-HA (Yan et al., 2018) were used to in vitro synthesize capped mRNAs using mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). To knock down zebrafish β-catenin2, β-cat2-MO and its control morpholino (cMO) were used as described before (Zhang et al., 2012). mRNA or MO was injected into embryos at the one-cell stage.

Embryos or eggs (15 per sample) were harvested at desired stages, and used to extract total RNA by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as previously described (Jia et al., 2009). cDNA was synthesized using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and qRT-PCR was performed with TransStart Top Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech) as described (Sun et al., 2018). Expression levels were normalized to the reference gene eif4g2a unless otherwise stated. The Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unequal variance) was used to determine p-values. Primers and sequences for qRT-PCR analysis were as follows: ndr1-F (5′-TTGGATATGCTCCTTGACCC-3′), ndr1-R (5′-ACAGATAAGGCAAACACGCAAA-3′); ndr2-F (5′-GAAATATCATCACCCCAGTCGT-3′), ndr2-R (5′-CTCCACCTGCATGTCCTCGT-3′); tbxta-F (5′-TTGGAACAACTTGAGGGTGA-3′), tbxta-R (5′-CGGTCACTTTTCAAAGCGTAT-3′); sox32-F (5′-TCTGCCACGGTCTGCTTAC-3′), sox32-R (5′-CAGAGAAGGTCCACCCAAAC-3′); gata2a-F (5′-CTCCTCAGCGGATCCGCTTCCAGC-3′), gata2a-R (5′-GGTCGTGGTTGTCTGGCAGTTCGC-3′); gsc-F (5′-GAGACGACACCGAACCATTT-3′), gsc-R (5′-CCTCTGACGACGACCTTTTC-3′).

The graphs and t-test were finished with GraphPad Prism 7. Error bars represent mean ± SD. p values are two-sided. Significance levels were indicated by nonsignificant (ns); *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

The eomesatsu007 mutant allele harbors a 353-bp deletion between the first and the second exon, resulting in a premature stop codon upstream of the T-box coding region (Figure 1A). Maternal eomesa mutants (Meomesatsu007) showed delayed epibolic process; the majority of Meomesatsu007 mutants died before 24 hpf and survivors at 24 hpf had a normal head with thin posterior trunk (posterior defect) or had thin anterior trunk with a bulged yolk extension (yolk defect) (Figures 1C-D’). These defects are similar to those observed in Meomesafh105 mutants (Du et al., 2012).

Using eomesatsu007 and hwatsu01sm lines (Yan et al., 2018), we managed to obtain eomesa;hwa double homozygotes (Zeomesa;Zhwa) female fish, which were fertile and used to produce Meomesa;Mhwa embryos by in vitro fertilization using sperms squeezed from WT males. Generally, the Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants exhibited more severe phenotype than either of single mutants (Figures 1D–F). An average of 91% maternal double mutant embryos were arrested and deformed during gastrulation and the remaining embryos at 24 hpf had a degenerating tail-like structure with missing of other tissues such as head and anterior trunk (Figures 1F, F’), indicating cooperative roles of maternal eomesa and hwa in embryonic survival.

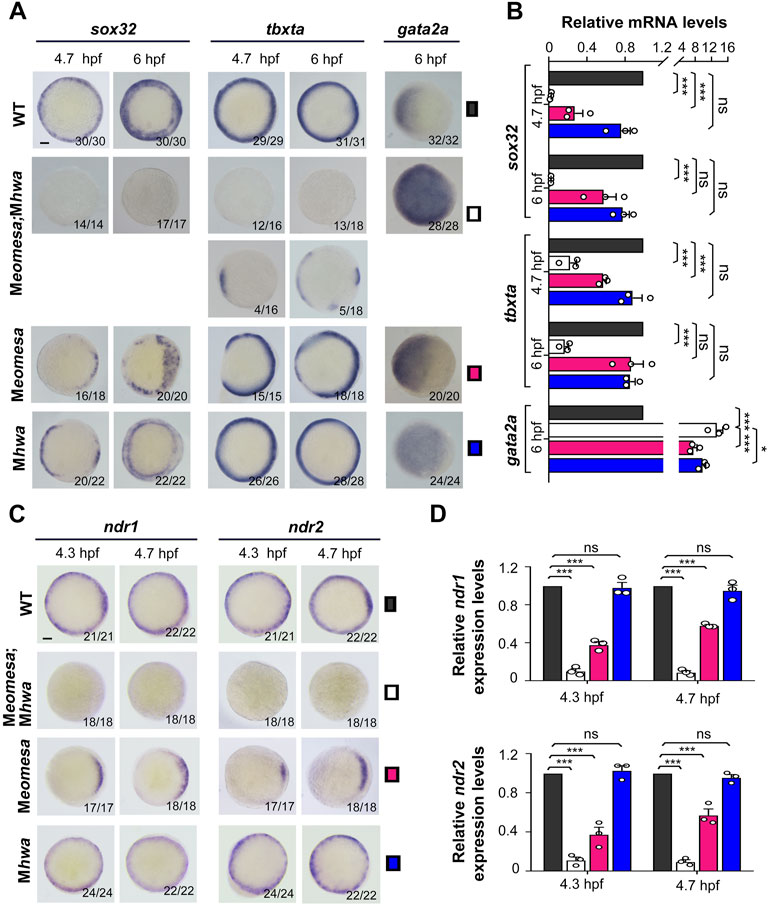

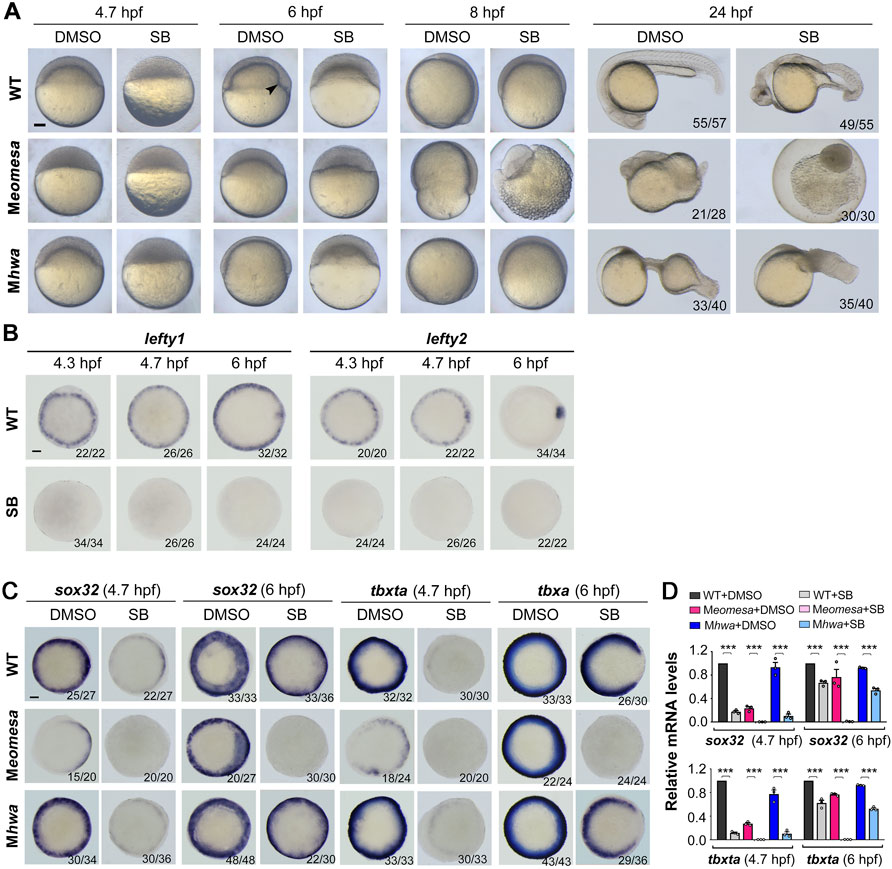

Then, we examined expression patterns of the endodermal marker sox32, the mesodermal marker tbxta (previously named ntla) and the epidermal marker gata2a in the single and double mutants at 4.7 hpf (30% epiboly stage) and 6 hpf (shield stage) by whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) (Figure 2A). Compared to WT embryos, sox32 expression in either of single mutants was weaker with some missing domains in the blastodermal margin, whereas it was completely abolished in Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants. Meomesa mutants showed missing of tbxta expression in some portions of the margin, which is consistent with the pattern observed in Meomesafh105 embryos (Xu P. et al., 2014), and Mhwa mutants appeared to express tbxta in the whole margin; in contrast, 73% of Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants lacked tbxta expression and the remaining proportion had a few small tbxta-expressing patches that might be caused by evoked genetic compensation through unknown mechanisms. The expression domain of gata2a was dorsally expanded in either of single mutants but further expanded throughout the blastoderm in the double mutants. qRT-PCR analysis using specific primers revealed a drastic decrease of sox32 and tbxta expression levels with a concomitant increase of gata2a levels in the double mutants (Figure 2B). These results indicate that maternal eomesa and hwa are two essential genes for mesendoderm induction and the whole blastoderm with their simultaneous loss may acquire the epidermis fate.

FIGURE 2. Expression patterns of mesendodermal markers and nodal genes in WT and mutant embryos. The expression of the endodermal marker sox32, the mesodermal marker tbxta and the epidermal marker gata2a as well as ndr1 and ndr2 was examined by WISH (A,C) or qRT-PCR (B,D) at indicated stages. Embryos in (A,C) were shown in animal-pole view with dorsal to the right if the dorsal was recognizable. The ratio of embryos with the representative pattern was indicated at the right bottom. Note that the majority of Meomesa;Mhwa embryos completely lacked tbxta expression while the other had some tbxta expression. Scale bars: 100 μm. For RT-PCR analysis, 15 embryos were pooled for each assay, and the expression level was normalized to that of eif4g2a in WT embryos at the same stage. Error bars indicated S.D. based on three biological replicates (indicated by small circles). Color keys for embryo types were shown in (A,C). Statistically significant levels: ns, nonsignificant; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Given that Nodal signaling is critical for mesendoderm induction, we wondered how ndr1 and ndr2 expression were altered in Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants. WISH results showed that either ndr1 or ndr2 expression was undetectable in the double mutants at 4.3 hpf and 4.7 hpf while detected in either of the single mutants (Figure 2C). qRT-PCR analyses using embryo pools disclosed that, compared to those in WT embryos, ndr1 and ndr2 levels were decreased significantly in Meomesa mutant embryos and further dropped in Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants whereas their expression levels were not changed significantly in Mhwa embryos (Figure 2D). These results indicate that ndr1 and ndr2 expression is initiated in the absence of either maternal eomesa or hwa but fail to initiate in the absence of both maternal factors.

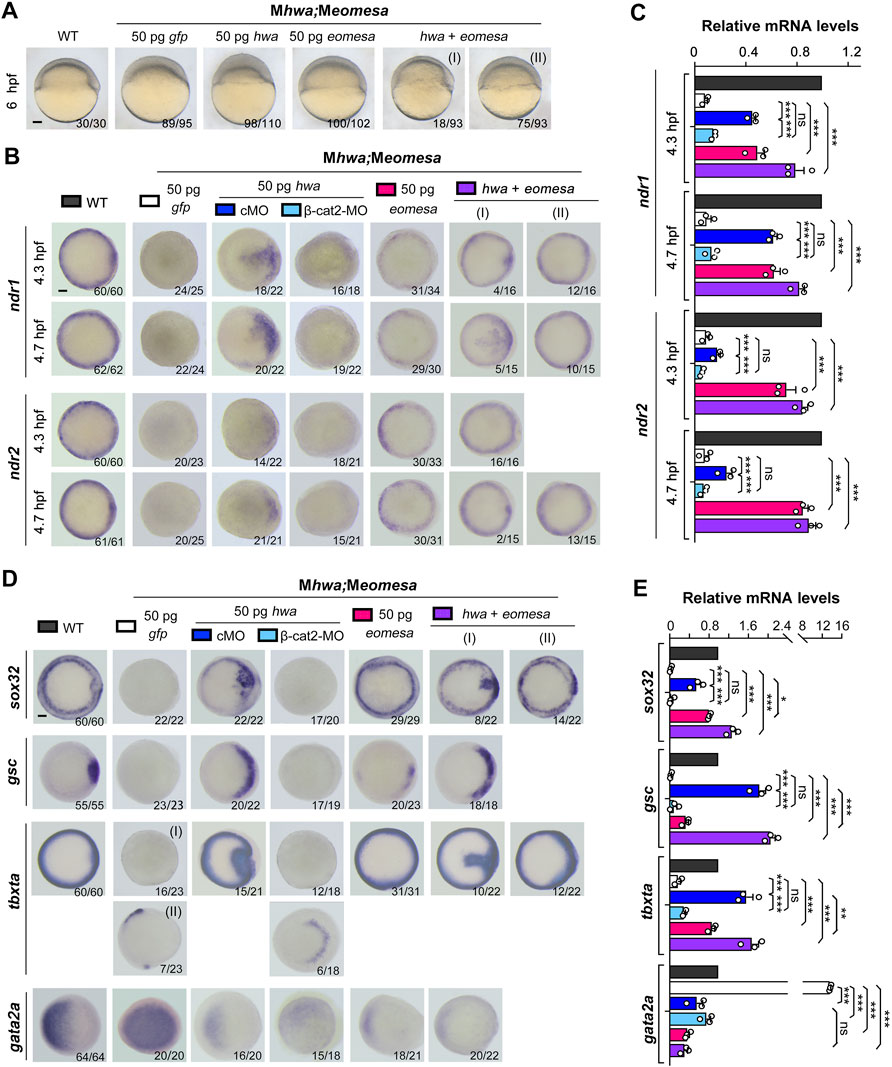

Next, we tested the capability of exogenous eomesa and hwa to induce ndr1 and ndr2 in the absence of both endogenous Eomesa and Hwa. We injected myc-eomesa, hwa or both mRNAs into Meomesa;Mhwa double mutant embryos at the one-cell stage. Morphological observation at 6 hpf indicated that eomesa but not hwa overexpression could largely rescue the Meomesa;Mhwa phenotype of slow epiboly, and co-overexpression of eomesa and hwa could restore the embryonic shield (Figure 3A). The injected embryos were then examined for ndr1 and ndr2 expression at 4.3 hpf and 4.7 hpf by WISH. Results disclosed that myc-eomesa overexpression induced ndr1 and ndr2 expression in the whole blastodermal margin, hwa overexpression activated their expression only in one side of the blastoderm (presumably dorsal side), and co-overexpression induced their expression at higher levels (Figure 3B). The induction of ndr1 and ndr2 by hwa mRNA was abolished when β-cat2 was knocked down with an antisense morpholino, which corroborates that hwa mainly exerts its effect through activation of β-catenin signaling (Yan et al., 2018). Besides, hwa showed a stronger induction activity for ndr1 than for ndr2 while eomesa had a stronger induction activity for ndr2 than for ndr1. These observations were confirmed by qRT-PCR data (Figure 3C). These results imply that either Eomesa or Hwa is sufficient to activate nodal genes expression, however, the former may be a more general activator while the latter may act as a regional activator.

FIGURE 3. Induction of nodal genes and mesendodermal markers in Meomesa;Mhwa mutants by ectopic hwa or/and eomesa. One-cell stage mutant embryos were injected with corresponding mRNA or/and MO and observed for morphology at 6 hpf (A) or harvested at indicated stages for detection of selected genes by WISH (B,D) or by RT-PCR analysis (C,E). Embryos were positioned laterally (A) or in animal-pole view (B,D) with dorsal to the right if the dorsal side was perceptible. The ratio of embryos with the representative pattern was indicated in the right bottom. Scale bars: 100 μm. Injection doses of mRNA or MO: hwa and myc-eomesa, 50 pg/embryo; cMO (as control MO) and β-cat2-MO, 20 ng/embryo. qRT-PCR analysis was performed using 15 embryos per sample, and the expression level was normalized to that of eif4g2a in WT embryos at the same stage. Error bars indicated S.D. based on three biological replicates (indicated by small circles). Color keys for embryo types and treatments were shown in (A,B,D). Statistically significant level: ns, nonsignificant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

We then investigated mesendoderm induction capacity of eomesa and hwa in maternal double mutants. We found that overexpression of eomesa or hwa alone or together in Meomesa;Mhwa embryos could induce expression of sox32, gsc and tbxta but reduce gata2 expression as examined by WISH and qRT-PCR (Figures 3D,E). Notably, overexpression effect of hwa was eliminated (on sox32, gsc and tbxta) or reduced (on tbxta and gata2a) when β-catenin2 was knocked down at the same time, which confirmed dependence of hwa function on β-catenin2 (Yan et al., 2018). Besides, compared to hwa, ectopic eomesa exhibited a stronger inductive effect on sox32 and tbxta but weaker effect on the dorsal mesodermal marker gsc, supporting the idea that eomesa plays a more general role in mesendoderm induction.

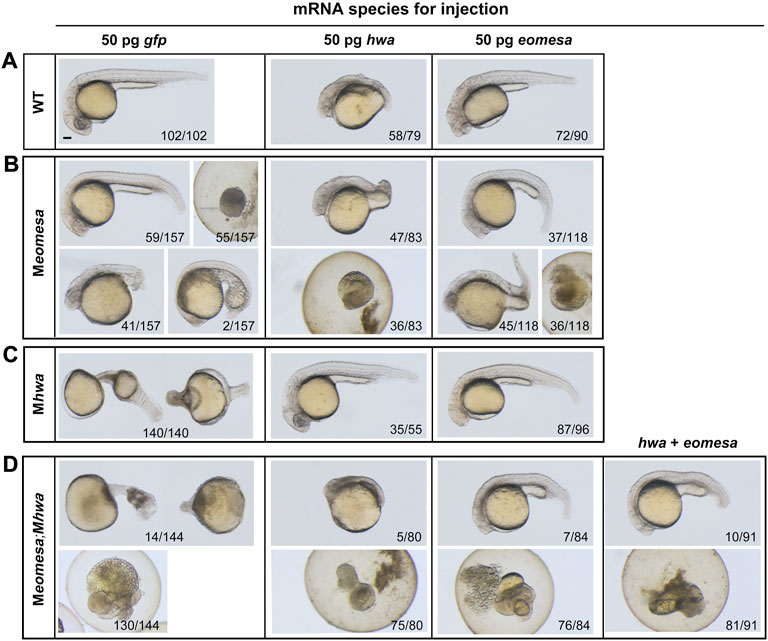

We extended our observation to morphological changes in WT, Mhwa, Meomesa, or Meomesa;Mhwa embryos at 24 hpf after overexpression of eomesa, hwa or together. Generally, hwa overexpression in WT embryos led to strong embryonic dorsalization with missing posterior structures as reported before (Yan et al., 2018), whereas eomesa overexpression caused relatively weak dorsalization with thinner posterior structures (Figure 4A). Notably, 90.6% (n = 96) of Mhwa mutants, which lack the head and anterior trunk structures (Yan et al., 2018), were able to form the head and the whole trunk following eomesa overexpression (Figure 4C), while hwa overexpression in Meomesa mutants still caused strong dorsalized phenotype (Figure 4B). As described above, most of Meomesa;Mhwa double mutants died before 24 hpf and the survivors all had a degenerating tail-like structure without a head; however, overexpression of eomesa or hwa alone or together appeared unable to evidently reduce the mortality (Figure 4D). Nevertheless, eomesa overexpression alone or co-overexpression with hwa allowed 8–11% of embryos to form the head and the trunk, whereas hwa overexpression alone allowed only 6.3% of embryos to form an abnormal head and anterior trunk with missing of posterior trunk structures (Figure 4D). Although the above overexpression effects should be investigated further by titrating dosages of ectopic mRNA species, our observations support an idea that the role of eomesa in development of ventrolateral mesendoderm-derived tissues may not be replaced by hwa.

FIGURE 4. Overexpression effect of eomesa and hwa in WT and different types of mutant embryos on morphological changes at 24 hpf. (A–D) Morphology of WT or mutants at 24 hpf under different mRNAs injection. One-cell stage WT or mutant embryos were injected with corresponding mRNA and observed for morphology at 24 hpf. Embryos were positioned laterally with the head to the left. The ratio of embryos with the representative pattern was indicated at bottom. Injection doses: hwa and myc-eomesa, 50 pg/embryo. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the TGFβ signaling inhibitor SB431542 (SB) or SB505124 can efficiently block Nodal signaling, resulting in loss of mesendodermal tissues in zebrafish embryos (Sun et al., 2006; Hagos and Dougan, 2007). We set out to look into effect of Nodal signaling inhibition on mesendodermal induction in Meomesa, Mhwa or Meomesa;Mhwa mutant embryos. One-cell stage embryos of different mutant or WT lines were incubated in the presence of 50 μM SB until harvested for observation or assays. As shown before (Sun et al., 2006), SB treatment caused loss of the embryonic shield at the shield stage (6 hpf) and most mesendodermal tissues in WT embryos at 24 hpf (Figure 5A). SB-treated Mhwa or Meomesa mutant embryos at 24 hpf also showed more severe defects compared to the untreated control mutants (Figure 5A). The complete loss of the Nodal target genes lefty1 and lefty2 in SB-treated WT embryos confirmed the effectiveness of SB treatment (Figure 5B). Then, we examined expression of sox32 and tbxta at 4.7 hpf and 6 hpf by WISH and qRT-PCR analysis (Figures 5C,D). WISH results showed that sox32 and tbxta expression became very weak at 4.7 hpf and largely recovered at 6 hpf in SB-treated WT and Mhwa embryos; in contrast, their expression appeared undetectable at both stages in SB-treated Meomesa embryos (Figure 5C). qRT-PCR results also confirmed that SB treatment significantly inhibited sox32 and tbxta expression in WT and Mhwa embryos but caused loss of sox32 and tbxta expression in Meomesa embryos (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results suggest that Nodal signaling may contribute to mesendoderm induction at variable levels in different genetic backgrounds.

FIGURE 5. Responses of Meomesa and Mhwa mutants to Nodal signaling inhibition. One-cell stage embryos (10 min postfertilization) were incubated in Holfreter’s water with 1% DMSO (control) or 50 μM SB431542 (SB, the Nodal signaling inhibitor), and harvested at 24 hpf for morphological observation (A) or for detection of marker gene expression by WISH (B,C) or qRT-PCR analysis (D) at indicated stages. Note that inhibition of Nodal signaling aggravated mesendodermal defects in both Meomesa and Mhwa mutants (A). Embryos were positioned laterally (A) or in animal-pole view with dorsal to the right (B,C) if the dorsal or tail was perceptible. The embryonic shield in WT embryo at the shield stage was indicated by an arrowhead. Scale bars, 100 μm. The ratio of embryos with the representative pattern was indicated in the right bottom (B,C). qRT-PCR analysis was performed using 15 embryos per sample, and the expression level was normalized to that of eif4g2a in WT embryos at the same stage. Error bars indicated S.D. based on three biological replicates (indicated by small circles). Statistically significant level: ***, p < 0.001.

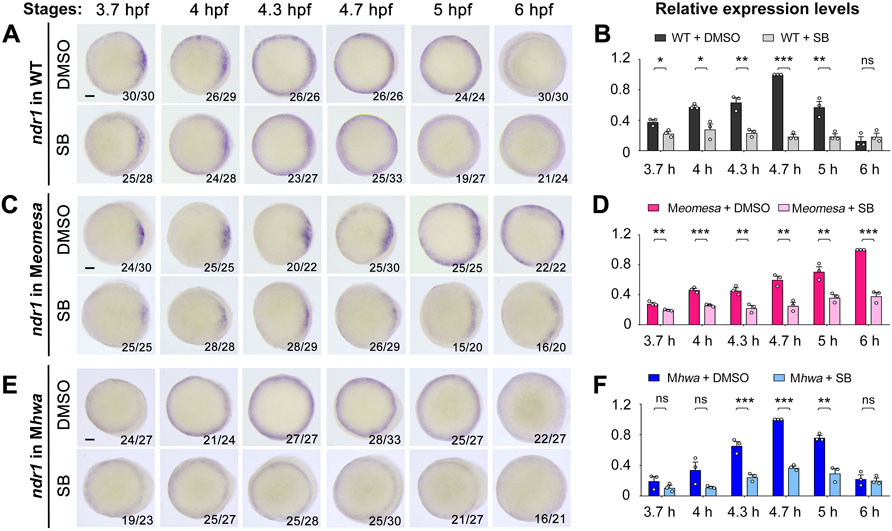

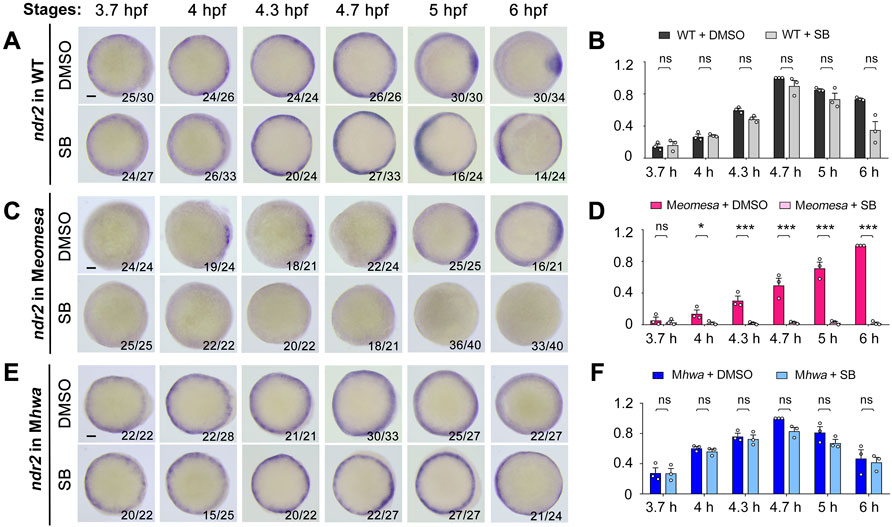

Based on the above data, we hypothesize that the mesendodermal fate in the zebrafish embryo is induced via Ndr1 and Ndr2 by three factors, i.e., maternal eomesa, maternal hwa-activated β-catenin signaling and Nodal autoregulation. We assume that zygotic ndr1 and ndr2 expression in Meomesa mutants depends on maternal hwa and Nodal autoregulation while their expression in Mhwa mutants relies on maternal eomesa and Nodal autoregulation. To assess contributions of individual factors, we examined ndr1 and ndr2 expression patterns by WISH as well as their total levels by qRT-PCR analysis in WT, Meomesa and Mhwa embryos from 3.7 hpf to 6 hpf without or with SB treatment (Figures 6, 7).

FIGURE 6. Effect of Nodal signaling inhibition on ndr1 expression in WT and mutant embryos. WT, Meomesa or Mhwa embryos at the one-cell stage were incubated in Holfreter’s water with 1% DMSO (control) or 50 μM SB431542 (SB) and harvested at indicated stages for detection of ndr1 expression by WISH (A,C,E) or qRT-PCR analysis (B,D,F). Embryos (A,C,E) were positioned in animal-pole view with dorsal to the right if the dorsal side was distinguishable. The ratio of embryos with the representative pattern was indicated in the right bottom. Scale bars, 100 μm. qRT-PCR analysis was performed using 15 embryos per sample. The expression level at 3.7, 4, 4.3, 5 and 6 hpf in WT or Mhwa embryos was normalized to that at 4.7 hpf in WT embryo, while the expression level at different stages in WT or Meomesa embryos was normalized to that at 6 hpf in WT embryos. Error bars indicated S.D. based on three biological replicates (indicated by small circles). Statistically significant levels: ns, nonsignificant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

FIGURE 7. Effect of Nodal signaling inhibition on ndr2 expression in WT and mutant embryos. Embryo treatment and data presentation were similar to those described in Figure 6 legend.

We first investigated ndr1 expression in detail. In SB-treated WT embryos, the expression pattern of ndr1 was unaltered as indicated by WISH (Figure 6A), but its expression level decreased from 3.7 hpf to 6 hpf as examined by qRT-PCR (Figure 6B), which suggest a role of Nodal autoregulation in maintaining ndr1 expression. Interestingly, the degree of ndr1 reduction due to SB treatment gradually increased from 3.7 hpf to 4.7 hpf, implying that Nodal autoregulation contributes to ndr1 expression more and more during that period.

In Meomesa mutants without SB treatment, ndr1 expression was activated in the dorsal margin with a smaller area than in WT embryos at 3.7 hpf, then propagated ventrally with a slower rate than in WT embryos, and occurred in the whole blastodermal margin at 5 hpf (Figure 6C, upper panel), which were consistent with previous observation (Xu P. et al., 2014). In SB-treated Meomesa mutants, in contrast, ndr1 was still activated in the dorsal margin at a reduced level at 3.7 hpf, its expression domain expanded ventrally but never occupied the whole margin (Figure 6C, lower panel). qRT-PCR results showed that SB-treatment caused a significant reduction (by 31%–62%) of the ndr1 expression level from 3.7 hpf to 6 hpf (Figure 6D). Thus, in the absence of maternal eomesa, maternal hwa alone can activate ndr1 expression in the dorsal margin; and the ventral expansion of ndr1 expression domain as well as increments of ndr1 expression heavily depend on positive feedback of Nodal signaling.

In Mhwa mutants without SB treatment, ndr1 expression was not prominent in the dorsal margin but similar to WT in the other marginal areas at 3.7 hpf, and its expression pattern later on was comparable to WT embryos (Figure 6E, upper panel; and also see Figure 2C). In SB-treated Mhwa mutants, ndr1 expression pattern was not obviously altered at all examined stages as detected by WISH (Figure 6E, lower panel); however, qRT-PCR results showed a significant reduction of ndr1 expression level at 4.3 hpf, 4.7 hpf and 5 hpf while changes at other stages were not significant (Figure 6F). Apparently, maternal Eomesa alone is capable of activating ndr1 expression in the whole blastoderm margin but its enhancement during late blastulation requires the contribution of Nodal autoregulation.

Taken together, these results suggest that maternal eomesa can activate ndr1 expression in the whole blastodermal margin, maternal hwa activates ndr1 only in the dorsal margin, and Nodal autoregulation contributes to enhancement of ndr1 expression.

We similarly investigated implication of maternal eomesa, maternal hwa and Nodal autoregulation in ndr2 expression. In SB-treated WT embryos, the ndr2 expression pattern was not obviously altered from 3.7 hpf to 4.7 hpf (Figure 7A). However, unlike in untreated WT embryos, ndr2 expression in SB-treated WT embryos at 5 hpf and 6 hpf was not prominently enriched in the dorsal margin, instead it appeared enhanced in the ventrolateral margin, for which we did not find an explanation at the moment. The total expression level of ndr2 in SB-treated embryos, as revealed by qRT-PCR analysis, was not significantly decreased at all examined stages (Figure 7B). It appears that Nodal autoregulation is less important for ndr2 expression than for ndr1 expression in WT embryos.

In Meomesa mutants without SB treatment (Figure 7C, upper panel), ndr2 expression occurred in the dorsal margin from 4 hpf to 5 hpf and extended to the whole margin at 6 hpf as reported before (Xu P. et al., 2014). In SB-treated Meomesa mutants, however, ndr2 expression was hardly detectable by WISH (Figure 7C, lower panel). qRT-PCR results showed that, compared to untreated Meomesa mutants, the ndr2 expression level in SB-treated Meomesa mutants was almost abolished (Figure 7D). This observation implies that, in the absence of maternal eomesa, maternal hwa might initiate ndr1 expression in the dorsal margin at low levels and existing Ndr1 thereof promotes ndr2 expression through Nodal signaling feedback.

As previously shown in Figure 2D, overall level of ndr2 expression in Mhwa was comparable to that in WT embryos. Surprisingly, we observed that the expression pattern and overall level of ndr2 in Mhwa embryos was unchanged by SB treatment (Figures 7E,F). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that maternal eomesa plays a major role in activation and maintenance of ndr2 expression in WT background.

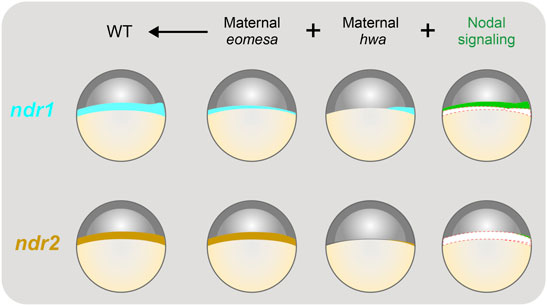

In this study, we delineated the roles of maternal eomesa, maternal Hwa-activated β-catenin signaling and Nodal autoregulation in spatiotemporal regulation of ndr1 and ndr2 expression during early development of zebrafish embryos. As illustrated in Figure 8, maternal hwa contributes to ndr1 expression in the dorsal blastodermal margin, maternal eomesa promotes ndr1 expression throughout the blastodermal margin, and positive feedback of Nodal signaling enhances ndr1 expression (Figure 8, upper panel). By contrast, ndr2 expression mostly relies on maternal eomesa with minor contribution of maternal hwa and Nodal autoregulation during initial activation (Figure 8, lower panel). However, when maternal Eomesa is absent as the case in Meomesa, Nodal signaling feedback, which is most likely derived from existing Ndr1, contributes more to ndr2 expression. Given that hwa is maternally expressed only (Yan et al., 2018) and MZeomesa and Meomesa mutants show the same ndr1 and ndr2 expression patterns before the shield stage (Xu P. et al., 2014), it is unlikely that zygotically expressed eomesa and hwa transcripts participate in activation of zygotic ndr1 and ndr2 expression.

FIGURE 8. Illustration of contributions of maternal eomesa, hwa/β-catenin signaling and Nodal signaling to ndr1 and ndr2 expression. The expression pattern of ndr1 and ndr2 in the late blastula (in lateral view with dorsal to the right and animal pole to the top) is depicted. The overall expression level of ndr1 or ndr2 is the sum of contributions from maternal eomesa (as seen in Mhwa without Nodal signaling), maternal hwa/β-catenin signaling (as seen in Meomesa without Nodal signaling) in and Nodal signaling (autoregulation). In wildtype (WT) embryos, all of the three forces make a significant contribution to ndr1 expression; however, maternal eomesa makes a predominant contribution to ndr2 expression while maternal hwa/β-catenin signaling may contribute a little to ndr2 expression by activating ndr1 in the dorsal blastodermal margin and thereof Nodal signaling. In the last column, ndr1 and ndr2 levels contributed by eomesa and hwa were shown as empty to highlight the contribution of Nodal signaling.

The mouse genome contains a single Nodal gene. Its expression may start in the inner cell mass of blastocysts, well before the onset of gastrulation (Granier et al., 2011; Papanayotou et al., 2014), and will be gradually restricted to the posteroproximal region of the primitive streak at the onset of gastrulation (Shen, 2007). Based on transgenic reporter assay, early expression of Nodal in mouse blastocysts has been suggested to require the pluripotency factor Oct4, Activin/Nodal signaling and β-catenin signaling (Granier et al., 2011; Papanayotou et al., 2014). A previous study demonstrated that the mouse Nodal locus contains an upstream Eomes binding site and overexpression of zebrafish eomesa promotes the expression of endogenous Nodal gene with mesendoderm induction in murine embryonic stem cells (Xu P. et al., 2014). Given that Eomes protein is expressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos (McConnell et al., 2005), maternal Eomes likely participates in early Nodal gene activation in the mouse blastocyst, which needs to be explored in the future.

We observed that the expression of either ndr1 or ndr2 in Meomesa;Mhwa double mutant embryos is completely abolished (Figures 2C,D), suggesting that maternal eomesa and maternal hwa are two essential factors for nodal genes expression. Consequently, none of the double mutants showed the expression of the endodermal marker sox32 (Figures 2A,B), implying that endoderm induction totally depends on Nodal signaling. However, 25–28% of the double mutants retained tbxta expression episodically in the blastodermal margin of the double mutants (Figure 2A). It is likely that the mesodermal fate, or tbxta expression only, might be induced by other factors or compensatory signaling pathway(s) in the complete absence of Nodal signaling. Our observations are consistent with the fact that ndr1;ndr2 double mutants completely lack endodermal tissues but still have some posterior mesodermal tissues (Feldman et al., 1998).

A puzzling observation is that inhibition of Nodal signaling has a little effect on ndr2 expression in WT or Mhwa embryos (Figures 7A,B,E,F), which suggests a minor or negligible role of Nodal autoregulation in ndr2 expression. However, in Meomesa mutant embryos, Nodal autoregulation makes an obvious contribution to ndr2 expression (Figures 7C,D). A possible explanation is that association of Eomesa with the general transcription machinery at the ndr2 locus may mask the Nodal responsive element(s), and these elements can be bound by the Nodal effectors Smad2/3 only when Eomesa is unavailable. The abandonment of Nodal autoregulation for ndr2 expression might facilitate spatial control of ndr2 expression domain and function.

Initiation of zygotic ndr1 and ndr2 expression occurs after MBT (Rebagliati et al., 1998). However, Eomesa protein exists in the cytoplasm of oocytes and fertilized eggs (Bruce et al., 2003) and hwa is also maternally expressed (Yan et al., 2018). An interesting question is why maternal Eomesa and/or maternal Hwa are unable to activate ndr1 and ndr2 expression well before MBT. The timing of the zygotic genome activation (ZGA) is proposed to be controlled by the nucleocytoplasmic ratio or the maternal-clock (Tadros and Lipshitz, 2009; Schulz and Harrison, 2019). It remains elusive which ZGA mechanism is adopted by Eomesa/Hwa-activated ndr1 and ndr2 expression.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Tsinghua University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Conceptualization: AM; Methodology: CX, BG; Validation: CX; Formal analysis: CX, AM; Investigation: CX, YL; Resources: CX, WS, LY, and AM; Data curation: CX; Writing—original draft: CX; Writing—review and editing: AM; Visualization: CX; Supervision: AM; Project administration: AM; Funding acquisition: AM.

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (#2019YFA0801400 and #2018YFC1003304) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31988101 to AM).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Alex Schier for discussions and suggestions. We are also grateful to the members of Meng laboratory for help and discussion and the staff at the Cell Facility in Tsinghua Center of Biomedical Analysis for technical assistance.

Adachi, H., Saijoh, Y., Mochida, K., Ohishi, S., Hashiguchi, H., Hirao, A., et al. (1999). Determination of Left/right Asymmetric Expression of Nodal by a Left Side-specific Enhancer with Sequence Similarity to a Lefty-2 Enhancer. Genes Dev. 13 (12), 1589–1600. doi:10.1101/gad.13.12.1589

Agius, E., Oelgeschlager, M., Wessely, O., Kemp, C., and De Robertis, E. M. (2000). Endodermal Nodal-Related Signals and Mesoderm Induction in Xenopus. Development 127 (6), 1173–1183. doi:10.1242/dev.127.6.1173

Bellipanni, G., Varga, M., Maegawa, S., Imai, Y., Kelly, C., Myers, A. P., et al. (2006). Essential and Opposing Roles of Zebrafish β-catenins in the Formation of Dorsal Axial Structures and Neurectoderm. Development 133 (7), 1299–1309. doi:10.1242/dev.02295

Brennan, J., Lu, C. C., Norris, D. P., Rodriguez, T. A., Beddington, R. S. P., and Robertson, E. J. (2001). Nodal Signalling in the Epiblast Patterns the Early Mouse Embryo. Nature 411 (6840), 965–969. doi:10.1038/35082103

Bruce, A. E. E., Howley, C., Zhou, Y., Vickers, S. L., Silver, L. M., King, M. L., et al. (2003). The Maternally Expressed Zebrafish T-Box Geneeomesodermin Regulates Organizer Formation. Development 130 (22), 5503–5517. doi:10.1242/dev.00763

Chen, Y., and Schier, A. F. (2001). The Zebrafish Nodal Signal Squint Functions as a Morphogen. Nature 411 (6837), 607–610. doi:10.1038/35079121

Chen, Y., and Schier, A. F. (2002). Lefty Proteins are Long-Range Inhibitors of Squint-Mediated Nodal Signaling. Curr. Biol. 12 (24), 2124–2128. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01362-3

Conlon, F. L., Lyons, K. M., Takaesu, N., Barth, K. S., Kispert, A., Herrmann, B., et al. (1994). A Primary Requirement for Nodal in the Formation and Maintenance of the Primitive Streak in the Mouse. Development 120 (7), 1919–1928. doi:10.1242/dev.120.7.1919

De Robertis, E. M., and Kuroda, H. (2004). Dorsal-ventral Patterning and Neural Induction in Xenopus Embryos. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 285–308. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.011403.154124

Dougan, S. T., Warga, R. M., Kane, D. A., Schier, A. F., and Talbot, W. S. (2003). The Role of the Zebrafish Nodal-Related Genes Squint and Cyclopsin Patterning of Mesendoderm. Development 130 (9), 1837–1851. doi:10.1242/dev.00400

Du, S., Draper, B. W., Mione, M., Moens, C. B., and Bruce, A. (2012). Differential Regulation of Epiboly Initiation and Progression by Zebrafish Eomesodermin A. Dev. Biol. 362 (1), 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.036

Erter, C. E., Solnica-Krezel, L., and Wright, C. V. E. (1998). Zebrafish Nodal-Related 2 Encodes an Early Mesendodermal Inducer Signaling from the Extraembryonic Yolk Syncytial Layer. Dev. Biol. 204 (2), 361–372. doi:10.1006/dbio.1998.9097

Fan, X., Hagos, E. G., Xu, B., Sias, C., Kawakami, K., Burdine, R. D., et al. (2007). Nodal Signals Mediate Interactions between the Extra-embryonic and Embryonic Tissues in Zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 310 (2), 363–378. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.008

Feldman, B., Gates, M. A., Egan, E. S., Dougan, S. T., Rennebeck, G., Sirotkin, H. I., et al. (1998). Zebrafish Organizer Development and Germ-Layer Formation Require Nodal-Related Signals. Nature 395 (6698), 181–185. doi:10.1038/26013

Gore, A. V., and Sampath, K. (2002). Localization of Transcripts of the Zebrafish Morphogen Squint is Dependent on Egg Activation and the Microtubule Cytoskeleton. Mech. Dev. 112 (1-2), 153–156. doi:10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00622-0

Gore, A. V., Maegawa, S., Cheong, A., Gilligan, P. C., Weinberg, E. S., and Sampath, K. (2005). The Zebrafish Dorsal axis is Apparent at the Four-Cell Stage. Nature 438 (7070), 1030–1035. doi:10.1038/nature04184

Granier, C., Gurchenkov, V., Perea-Gomez, A., Camus, A., Ott, S., Papanayotou, C., et al. (2011). Nodal Cis-Regulatory Elements Reveal Epiblast and Primitive Endoderm Heterogeneity in the Peri-Implantation Mouse Embryo. Dev. Biol. 349 (2), 350–362. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.036

Hagos, E. G., and Dougan, S. T. (2007). Time-dependent Patterning of the Mesoderm and Endoderm by Nodal Signals in Zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 22. doi:10.1186/1471-213x-7-22

Hashimoto, H., Rebagliati, M., Ahmad, N., Muraoka, O., Kurokawa, T., Hibi, M., et al. (2004). The Cerberus/Dan-Family Protein Charon is a Negative Regulator of Nodal Signaling during Left-Right Patterning in Zebrafish. Development 131 (8), 1741–1753. doi:10.1242/dev.01070

Hong, S.-K., Jang, M. K., Brown, J. L., McBride, A. A., and Feldman, B. (2011). Embryonic Mesoderm and Endoderm Induction Requires the Actions of Non-embryonic Nodal-Related Ligands and Mxtx2. Development 138 (4), 787–795. doi:10.1242/dev.058974

Hyde, C. E., and Old, R. W. (2000). Regulation of the Early Expression of the Xenopus Nodal-Related 1 Gene, Xnr1. Development 127 (6), 1221–1229. doi:10.1242/dev.127.6.1221

Jia, S., Wu, D., Xing, C., and Meng, A. (2009). Smad2/3 Activities are Required for Induction and Patterning of the Neuroectoderm in Zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 333 (2), 273–284. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.037

Jones, C. M., Kuehn, M. R., Hogan, B. L., Smith, J. C., and Wright, C. V. (1995). Nodal-related Signals Induce Axial Mesoderm and Dorsalize Mesoderm during Gastrulation. Development 121 (11), 3651–3662. doi:10.1242/dev.121.11.3651

Jones, C. M., Armes, N., and Smith, J. C. (1996). Signalling by TGF-β Family Members: Short-Range Effects of Xnr-2 and BMP-4 Contrast with the Long-Range Effects of Activin. Curr. Biol. 6 (11), 1468–1475. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00751-8

Joseph, E. M., and Melton, D. A. (1997). Xnr4: A Xenopus Nodal-Related Gene Expressed in the Spemann Organizer. Dev. Biol. 184 (2), 367–372. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8510

Kelly, C., Chin, A. J., Leatherman, J. L., Kozlowski, D. J., and Weinberg, E. S. (2000). Maternally Controlled (Beta)-catenin-mediated Signaling is Required for Organizer Formation in the Zebrafish. Development 127 (18), 3899–3911. doi:10.1242/dev.127.18.3899

Kimmel, C. B., Ballard, W. W., Kimmel, S. R., Ullmann, B., and Schilling, T. F. (1995). Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203 (3), 253–310. doi:10.1002/aja.1002030302

Kofron, M., Demel, T., Xanthos, J., Lohr, J., Sun, B., Sive, H., et al. (1999). Mesoderm Induction in Xenopus is a Zygotic Event Regulated by Maternal VegT via TGFbeta Growth Factors. Development 126 (24), 5759–5770. doi:10.1242/dev.126.24.5759

Lim, S., Kumari, P., Gilligan, P., Quach, H. N. B., Mathavan, S., and Sampath, K. (2012). Dorsal Activity of Maternal Squint is Mediated by a Non-coding Function of the RNA. Development 139 (16), 2903–2915. doi:10.1242/dev.077081

Liu, Z., Lin, X., Cai, Z., Zhang, Z., Han, C., Jia, S., et al. (2011). Global Identification of SMAD2 Target Genes Reveals a Role for Multiple Co-regulatory Factors in Zebrafish Early Gastrulas. J. Biol. Chem. 286 (32), 28520–28532. doi:10.1074/jbc.m111.236307

Long, S., Ahmad, N., and Rebagliati, M. (2003). The Zebrafish Nodal-Related Gene Southpaw is Required for Visceral and Diencephalic Left-Right Asymmetry. Development 130 (11), 2303–2316. doi:10.1242/dev.00436

Luxardi, G., Marchal, L., Thomé, V., and Kodjabachian, L. (2010). Distinct Xenopus Nodal Ligands Sequentially Induce Mesendoderm and Control Gastrulation Movements in Parallel to the Wnt/PCP Pathway. Development 137 (3), 417–426. doi:10.1242/dev.039735

McConnell, J., Petrie, L., Stennard, F., Ryan, K., and Nichols, J. (2005). Eomesodermin is Expressed in Mouse Oocytes and Pre-implantation Embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 71 (4), 399–404. doi:10.1002/mrd.20318

Meno, C., Gritsman, K., Ohishi, S., Ohfuji, Y., Heckscher, E., Mochida, K., et al. (1999). Mouse Lefty2 and Zebrafish Antivin are Feedback Inhibitors of Nodal Signaling during Vertebrate Gastrulation. Mol. Cell 4 (3), 287–298. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80331-7

Müller, P., Rogers, K. W., Jordan, B. M., Lee, J. S., Robson, D., Ramanathan, S., et al. (2012). Differential Diffusivity of Nodal and Lefty Underlies a Reaction-Diffusion Patterning System. Science 336 (6082), 721–724. doi:10.1126/science.1221920

Müller, P., Rogers, K. W., Yu, S. R., Brand, M., and Schier, A. F. (2013). Morphogen Transport. Development 140 (8), 1621–1638. doi:10.1242/dev.083519

Norris, D. P., and Robertson, E. J. (1999). Asymmetric and Node-specific Nodal Expression Patterns are Controlled by Two Distinct Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements. Genes Dev. 13 (12), 1575–1588. doi:10.1101/gad.13.12.1575

Osada, S. I., and Wright, C. V. (1999). Xenopus Nodal-Related Signaling is Essential for Mesendodermal Patterning during Early Embryogenesis. Development 126 (14), 3229–3240. doi:10.1242/dev.126.14.3229

Osada, S. I., Saijoh, Y., Frisch, A., Yeo, C. Y., Adachi, H., Watanabe, M., et al. (2000). Activin/nodal Responsiveness and Asymmetric Expression of a Xenopus Nodal-Related Gene Converge on a FAST-Regulated Module in Intron 1. Development 127 (11), 2503–2514. doi:10.1242/dev.127.11.2503

Papanayotou, C., Benhaddou, A., Camus, A., Perea-Gomez, A., Jouneau, A., Mezger, V., et al. (2014). A Novel Nodal Enhancer Dependent on Pluripotency Factors and Smad2/3 Signaling Conditions a Regulatory Switch during Epiblast Maturation. PLoS Biol. 12 (6), e1001890. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001890

Rebagliati, M. R., Toyama, R., Fricke, C., Haffter, P., and Dawid, I. B. (1998). Zebrafish Nodal-Related Genes are Implicated in Axial Patterning and Establishing Left-Right Asymmetry. Dev. Biol. 199 (2), 261–272. doi:10.1006/dbio.1998.8935

Rex, M., Hilton, E., and Old, R. (2002). Multiple Interactions between Maternally-Activated Signalling Pathways Control Xenopus Nodal-Related Genes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46 (2), 217–226.

Schier, A. F., and Shen, M. M. (2000). Nodal Signalling in Vertebrate Development. Nature 403 (6768), 385–389. doi:10.1038/35000126

Schier, A. F. (2009). Nodal Morphogens. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1 (5), a003459. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003459

Schulz, K. N., and Harrison, M. M. (2019). Mechanisms Regulating Zygotic Genome Activation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20 (4), 221–234. doi:10.1038/s41576-018-0087-x

Shen, M. M. (2007). Nodal Signaling: Developmental Roles and Regulation. Development 134 (6), 1023–1034. doi:10.1242/dev.000166

Sun, Z., Jin, P., Tian, T., Gu, Y., Chen, Y.-G., and Meng, A. (2006). Activation and Roles of ALK4/ALK7-Mediated Maternal TGFβ Signals in Zebrafish Embryo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345 (2), 694–703. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.148

Sun, J., Yan, L., Shen, W., and Meng, A. (2018). Maternal Ybx1 Safeguards Zebrafish Oocyte Maturation and Maternal-To-Zygotic Transition by Repressing Global Translation. Development 145 (19), dev166587. doi:10.1242/dev.166587

Tadros, W., and Lipshitz, H. D. (2009). The Maternal-To-Zygotic Transition: A Play in Two Acts. Development 136 (18), 3033–3042. doi:10.1242/dev.033183

Takahashi, S., Yokota, C., Takano, K., Tanegashima, K., Onuma, Y., Goto, J., et al. (2000). Two Novel Nodal-Related Genes Initiate Early Inductive Events in Xenopus Nieuwkoop Center. Development 127 (24), 5319–5329. doi:10.1242/dev.127.24.5319

Tian, T., and Meng, A. M. (2006). Nodal Signals Pattern Vertebrate Embryos. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63 (6), 672–685. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5503-7

Williams, P. H., Hagemann, A., González-Gaitán, M., and Smith, J. C. (2004). Visualizing Long-Range Movement of the Morphogen Xnr2 in the Xenopus Embryo. Curr. Biol. 14 (21), 1916–1923. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.10.020

Xanthos, J. B., Kofron, M., Tao, Q., Schaible, K., Wylie, C., and Heasman, J. (2002). The Roles of Three Signaling Pathways in the Formation and Function of the Spemann Organizer. Development 129 (17), 4027–4043. doi:10.1242/dev.129.17.4027

Xu, P.-F., Houssin, N., Ferri-Lagneau, K. F., Thisse, B., and Thisse, C. (2014a). Construction of a Vertebrate Embryo from Two Opposing Morphogen Gradients. Science 344 (6179), 87–89. doi:10.1126/science.1248252

Xu, P., Zhu, G., Wang, Y., Sun, J., Liu, X., Chen, Y.-G., et al. (2014b). Maternal Eomesodermin Regulates Zygotic Nodal Gene Expression for Mesendoderm Induction in Zebrafish Embryos. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 (4), 272–285. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mju028

Yan, L., Chen, J., Zhu, X., Sun, J., Wu, X., Shen, W., et al. (2018). Maternal Huluwa Dictates the Embryonic Body axis through β-catenin in Vertebrates. Science 362 (6417), eaat1045. doi:10.1126/science.aat1045

Zhang, J., Houston, D. W., King, M. L., Payne, C., Wylie, C., and Heasman, J. (1998). The Role of Maternal VegT in Establishing the Primary Germ Layers in Xenopus Embryos. Cell 94 (4), 515–524. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81592-5

Zhang, M., Zhang, J., Lin, S.-C., and Meng, A. (2012). β-Catenin 1 and β-Catenin 2 Play Similar and Distinct Roles in Left-Right Asymmetric Development of Zebrafish Embryos. Development 139 (11), 2009–2019. doi:10.1242/dev.074435

Zhang, J., Jiang, Z., Liu, X., and Meng, A. (2016). Eph/ephrin Signaling Maintains the Boundary of Dorsal Forerunner Cell Cluster during Morphogenesis of the Zebrafish Embryonic Left-Right Organizer. Development 143 (14), 2603–2615. doi:10.1242/dev.132969

Zhou, X., Sasaki, H., Lowe, L., Hogan, B. L. M., and Kuehn, M. R. (1993). Nodal is a Novel TGF-β-like Gene Expressed in the Mouse Node during Gastrulation. Nature 361 (6412), 543–547. doi:10.1038/361543a0

Keywords: Nodal, Eomes, Hwa, maternal factor, mesoderm induction, zebrafish

Citation: Xing C, Shen W, Gong B, Li Y, Yan L and Meng A (2022) Maternal Factors and Nodal Autoregulation Orchestrate Nodal Gene Expression for Embryonic Mesendoderm Induction in the Zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10:887987. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.887987

Received: 02 March 2022; Accepted: 05 May 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Silvia L. López, CONICET Instituto de Biología Celular y Neurociencias (IBCN), ArgentinaReviewed by:

Kyo Yamasu, Saitama University, JapanCopyright © 2022 Xing, Shen, Gong, Li, Yan and Meng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anming Meng, mengam@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.