95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol. , 31 May 2021

Sec. Cell Death and Survival

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.689951

This article is part of the Research Topic Editor’s Pick 2021: Highlights in Cell Death and Survival View all 14 articles

The function of the Bcl-2 family member Bok is currently enigmatic, with various disparate roles reported, including mediation of apoptosis, regulation of mitochondrial morphology, binding to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors, and regulation of uridine metabolism. To better define the roles of Bok, we examined its interactome using TurboID-mediated proximity labeling in HeLa cells, in which Bok knock-out leads to mitochondrial fragmentation and Bok overexpression leads to apoptosis. Labeling with TurboID-Bok revealed that Bok was proximal to a wide array of proteins, particularly those involved in mitochondrial fission (e.g., Drp1), endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions (e.g., Stim1), and surprisingly among the Bcl-2 family members, just Mcl-1. Comparison with TurboID-Mcl-1 and TurboID-Bak revealed that the three Bcl-2 family member interactomes were largely independent, but with some overlap that likely identifies key interactors. Interestingly, when overexpressed, Mcl-1 and Bok interact physically and functionally, in a manner that depends upon the transmembrane domain of Bok. Overall, this work shows that the Bok interactome is different from those of Mcl-1 and Bak, identifies novel proximities and potential interaction points for Bcl-2 family members, and suggests that Bok may regulate mitochondrial fission via Mcl-1 and Drp1.

The Bcl-2 family mediates the intrinsic apoptosis pathway through the coordinated actions of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins (Kale et al., 2018). The pro-apoptotic proteins include Bax and Bak, which mediate the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria via mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), an effect opposed by the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and Bcl-xL. Pro-apoptotic sensitizer proteins, including Bad and Noxa, bind the anti-apoptotic proteins to prevent inhibition of apoptosis, while pro-apoptotic activator proteins, such as Bid and Bim, bind and activate Bax and Bak to facilitate MOMP. Many “non-apoptotic” roles for Bcl-2 family members have also been identified, including regulation of mitochondrial dynamics, Ca2+ homeostasis, and autophagy (Chong et al., 2020).

Bcl-2 related ovarian killer (Bok) was initially categorized as a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member that can trigger MOMP (Hsu et al., 1997; Llambi et al., 2016), but many recent studies have also identified non-apoptotic functions (Ke et al., 2012; D’Orsi et al., 2016; Naim and Kaufmann, 2020; Shalaby et al., 2020). For instance, Bok “knock-out” (KO) from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) causes mitochondrial fragmentation, which can be rescued by re-introduction of Bok (Schulman et al., 2019). This phenotype is intriguing, given that Bok is predominantly endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized (Echeverry et al., 2013) and constitutively bound to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) (Schulman et al., 2013, 2016), which are tetrameric channels that release Ca2+ from ER stores. Bok has also been reported to protect IP3Rs from proteolysis (Schulman et al., 2013), mediate ER stress-induced apoptosis (Carpio et al., 2015), and positively regulate uridine metabolism (Srivastava et al., 2019).

Proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) was developed after the discovery that a point mutation, R118G, in the Escherichia coli biotin ligase protein BirA created a promiscuous ligase that could biotinylate proteins within an approximately 20 nm radius in situ, after the addition of exogenous biotin (Roux et al., 2012). Since the inception of BioID, multiple iterative modifications have been made to the original biotin ligase, the most recent being TurboID, which contains 16 mutations, permitting efficient biotin labeling in situ in as little as 15 min (Branon et al., 2018).

Here we show using TurboID that the Bok interactome is wide-ranging, but importantly, contains numerous ER and mitochondrial proteins, including mediators of mitochondrial fission, proteins involved in ER-plasma membrane (PM) contact, and Mcl-1. Further, we show that Bok and Mcl-1 interact physically and functionally and that the interactomes for Bok, Bak, and Mcl-1 are distinct, but overlap somewhat. These results shed light on the cellular roles of Bok and other Bcl-2 family members.

HeLa cells were maintained as described (Pearce et al., 2007). Antibodies raised in rabbits were: anti-Mcl-1 #D35A5 (for immunoblot), anti-Bcl-xL #54H6, anti-Bax #2772, anti-Bcl-2 #50E3, anti-caspase-3 #9662, anti-pDrp1-616 #D9A1 and anti-pDrp1-637 #4867S (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Bak #06-536 (Millipore), anti-IP3R1, anti-IP3R2 and anti-IP3R3 (for immunoprecipitation; IP) (Wojcikiewicz, 1995), anti-erlin2 (Pearce et al., 2007), and anti-Bok (Ke et al., 2012). Mouse monoclonal antibodies were: anti-Flag epitope (M2, Sigma), anti-IP3R3 #610313 (for immunoblot) and anti-Drp1 #611112 (BD Biosciences), anti-V5 epitope tag (GenScript), anti-Mcl-1 #RC13 (for IP) and anti-streptavidin #S10D4 (ThermoFisher), and anti-p97 (Research Diagnostics Inc.). Purified streptavidin was from BioLegend. PCR and Gibson reagents were from New England BioLabs. SDS-PAGE reagents were from Bio-Rad. Lipofectamine 2000 was from ThermoFisher. Cell culture dishes were from Corning. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and all other reagents not listed were from Sigma. Vectors encoding mouse and human Mcl-1 and Bok, and human Bak were kind gifts from Dr. T. Kaufmann (Echeverry et al., 2013). pCag-mouse BokWT (Schulman et al., 2016) and associated mutants used in Figure 4 (BokL34G and BokΔTM, which lacks amino acids 188-213) were created by PCR using existing primers (Schulman et al., 2013). BioRender was used to generate Figures 1A, 2A, 3B and Supplementary Figures 2, 3.

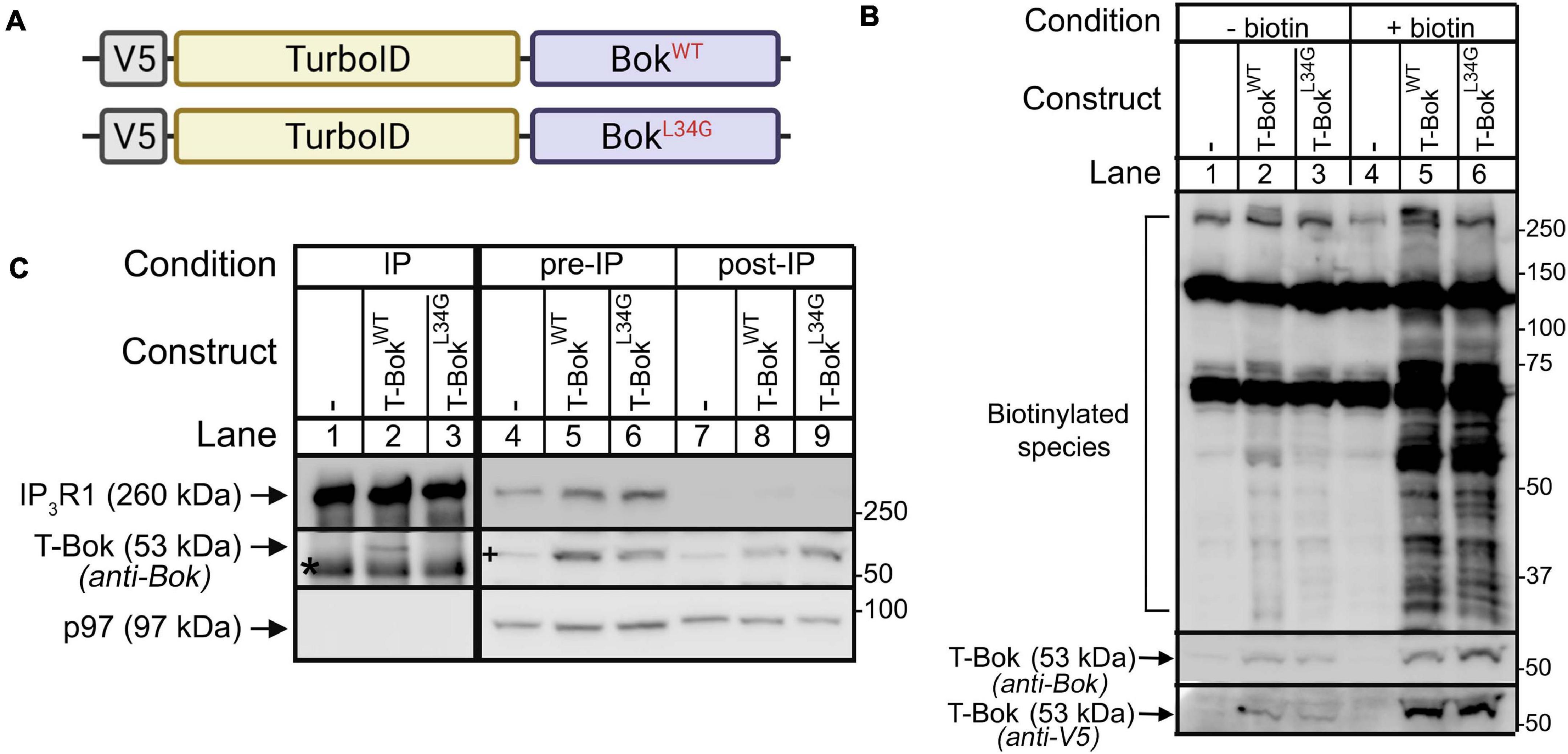

Figure 1. TurboID-Bok construct characterization. (A) V5-TurboID-Bok fusion constructs, T-BokWT and T-BokL34G. (B) Immunoblot for biotin-labeled species (detected with streptavidin/anti-streptavidin) in lysates from Bok KO HeLa cells transfected as indicated to express T-BokWT or T-BokL34G, without or with 2 h media supplementation with 50 μM biotin. Immunoreactivity of T-Bok constructs was assessed with either anti-Bok or anti-V5 (middle and lowest panels, respectively). (C) Anti-IP3R1/IP3R3 IP (lanes 1–3) and lysates (either pre- or post-IP; lanes 4–9) from Bok KO HeLa cells transfected as indicated, probed in immunoblots for the proteins indicated; p97 serves as a loading control. Co-migrating IgG heavy chain seen in the Bok probe of IPs is indicated by the asterisk. A 53kDa background band seen in the Bok probe of Bok KO cell lysates (lane 4) is indicated by the plus sign. Because BokL34G is relatively unstable (Schulman et al., 2016), to obtain equal expression, the amount of cDNA transfected for T-BokL34G was double that for T-BokWT.

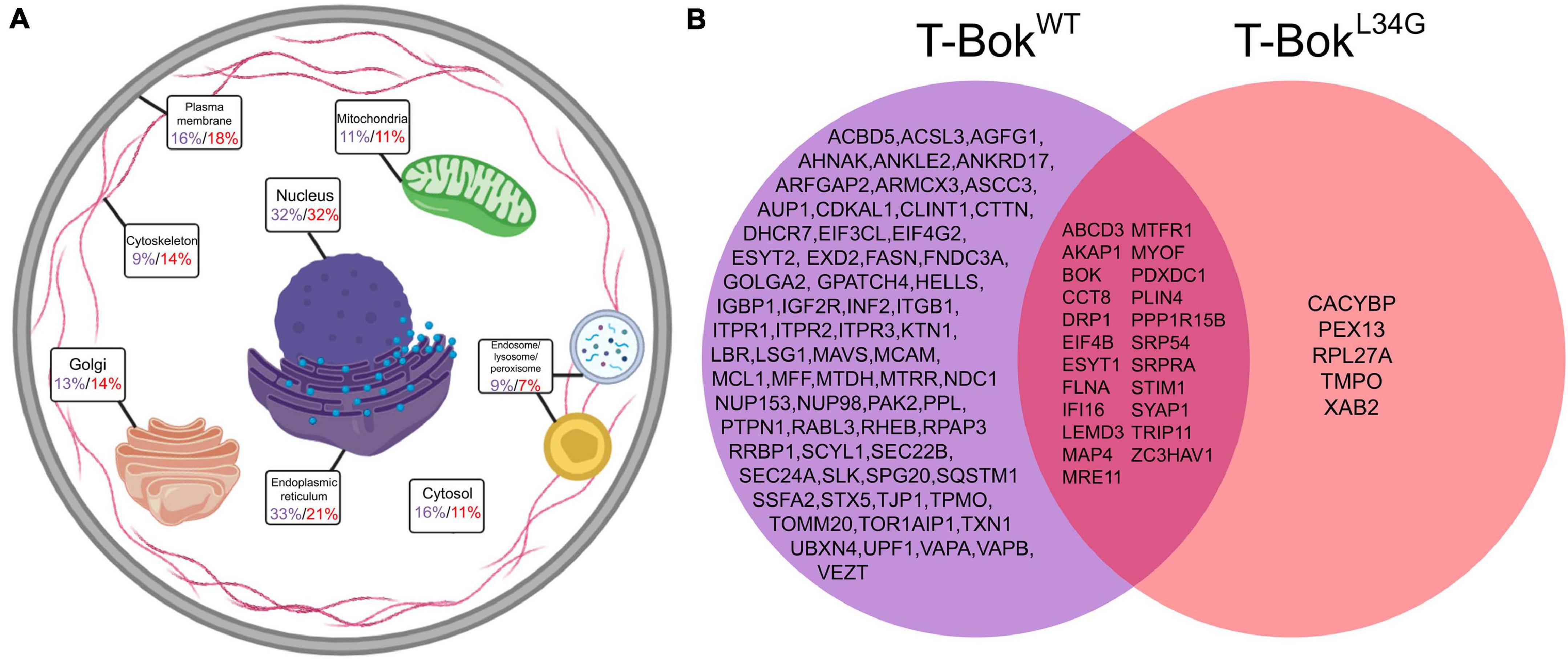

Figure 2. TurboID-BokWT and TurboID-BokL34G interactomes. (A) Localization of proteins identified by T-BokWT (purple) and T-BokL34G (red). Percentage values are the percent of proteins assigned to the specified subcellular compartment; as proteins were assigned to 1–3 compartments, percentages add to >100%. For further information, see Supplementary Tables 1, 2. (B) Comparison of proteins identified by T-BokWT and T-BokL34G. The proteins shown were present in at least 6/7 and 4/5 independent experiments, respectively.

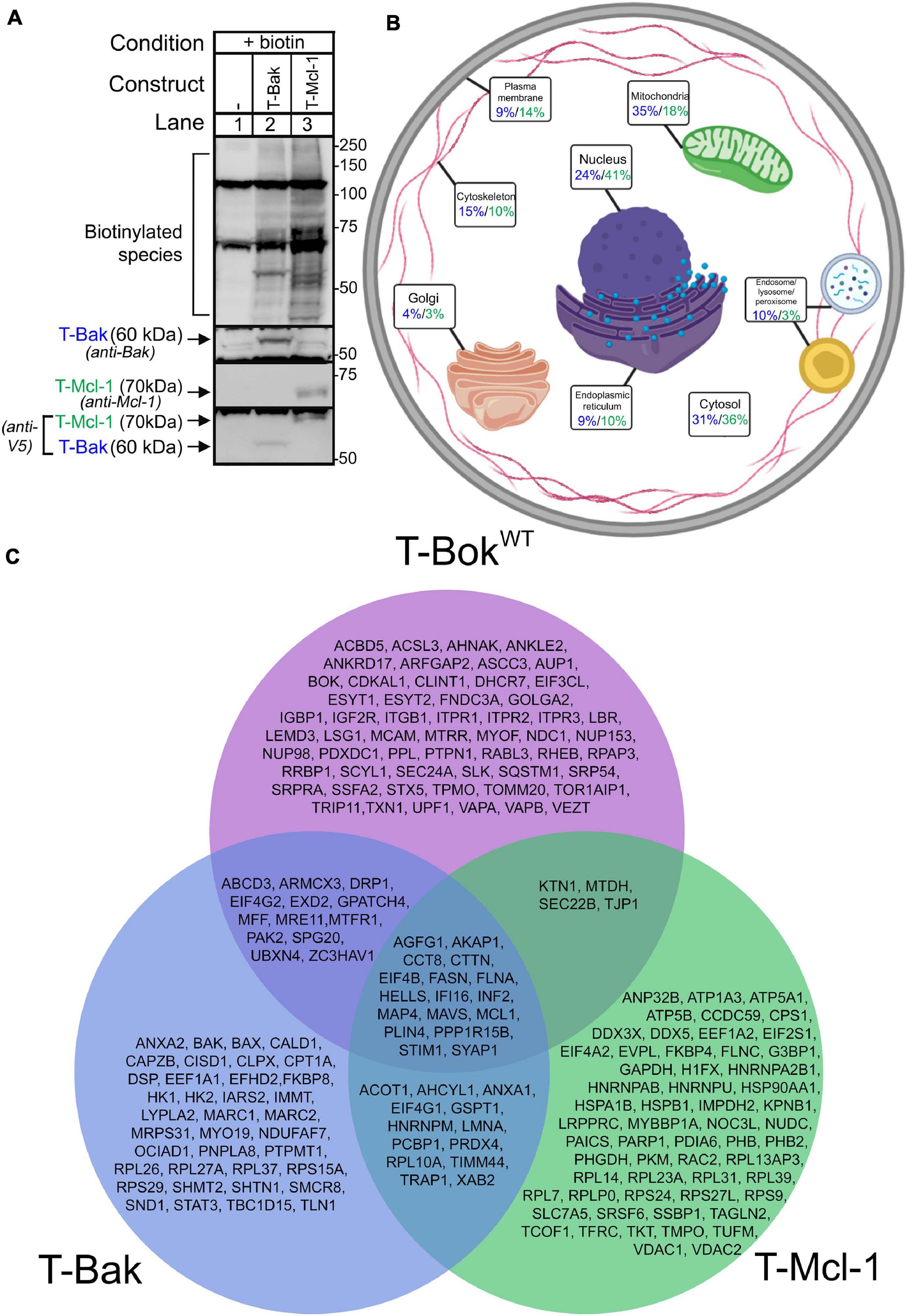

Figure 3. TurboID-Bak and TurboID-Mcl-1 interactomes. (A) Immunoblot for biotin-labeled species (detected with streptavidin/anti-streptavidin) in lysates from Bok KO HeLa cells transfected as indicated to express T-Bak or T-Mcl-1, without or with 2 h media supplementation with 50 μM biotin. Immunoreactivity of TurboID constructs was assessed with either anti-Bak, anti-Mcl-1, or anti-V5 (2nd-4th panels, respectively). (B) Localization of proteins identified by T-Bak (blue) and T-Mcl-1 (green). Percentage values are the percent of proteins assigned to the specified subcellular compartment; as proteins were assigned to 1–3 compartments, percentages add to >100%. For further information, see Supplementary Tables 3, 4. (C) Comparison of proteins identified by T-BokWT, T-Bak, and T-Mcl-1. The proteins shown were present in at least 6/7, 2/3, and 2/3 independent experiments, respectively.

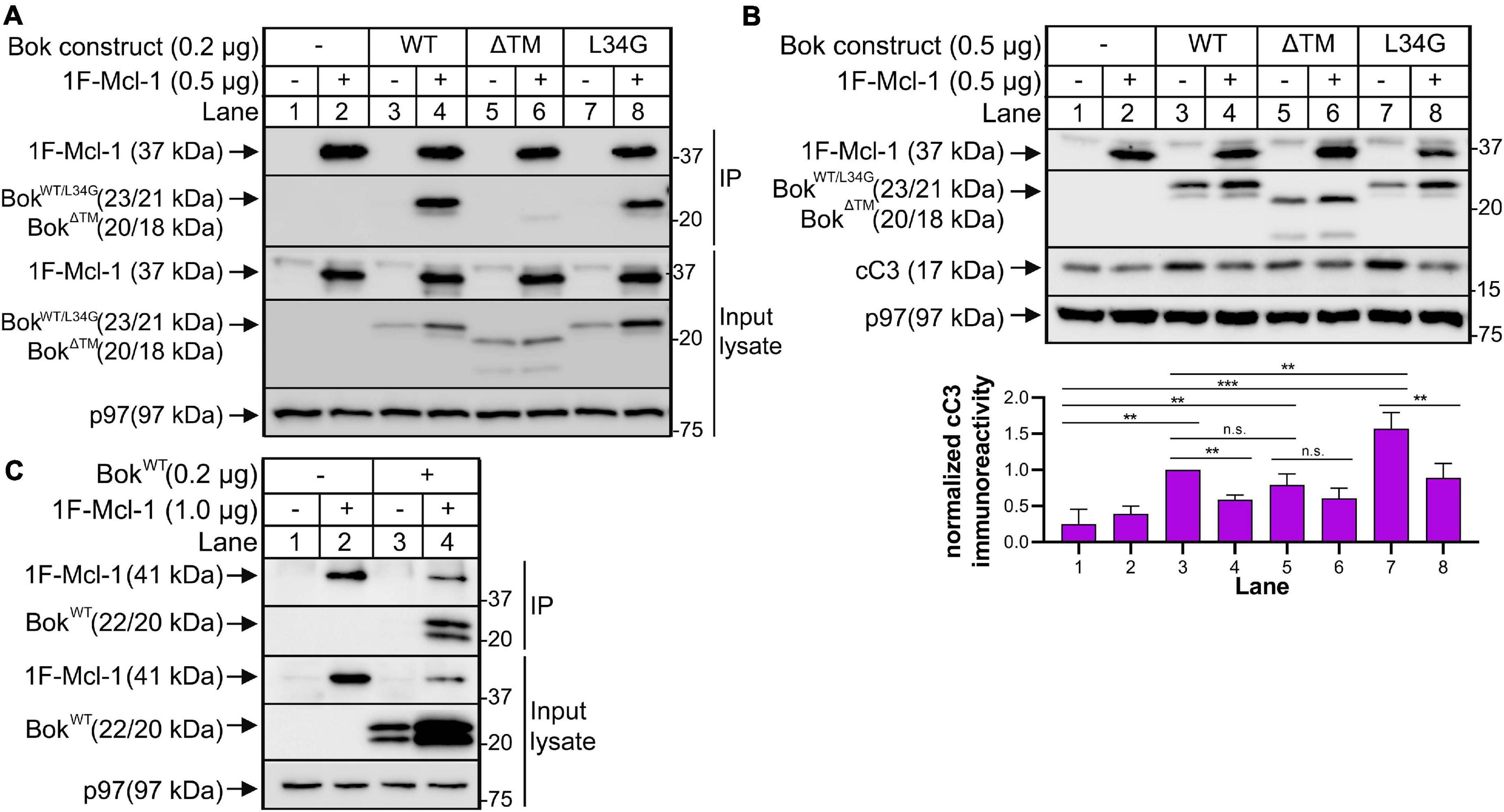

Figure 4. Overexpressed Mcl-1 and Bok interact with consequences on apoptotic signaling. (A) Bok KO HeLa cells were transfected to express 1F-mouse Mcl-1 and mouse BokWT and mutants as indicated for ∼18 h, and cell lysates and anti-Flag IPs were probed as indicated; p97 serves as a loading control. (B) Cleaved caspase-3 (cC3) immunoreactivity, visualized as an ∼17kDa band, was measured and quantified in Bok KO HeLa cells expressing 1F-mouse Mcl-1 and mouse BokWT and mutants as indicated for ∼18 h; a representative immunoblot is shown together with quantification of cC3 immunoreactivity using Image Lab software (mean ± SEM, n = 4). An unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used to determine significance; p < 0.005 is denoted by **, p < 0.0005 is denoted by ***, n.s. = not statistically significant. Data were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. (C) Bok KO HeLa cells were transfected to express 1F-human Mcl-1 and human BokWT as indicated for ∼18 h, and cell lysates and anti-Flag IPs were probed as indicated; p97 serves as a loading control.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system using the pCas-Guide-EF1a-GFP vector (#GE100018, OriGene) was used to generate Bok KO HeLa cells by targeting exon 2 (GTCTGTGGGCGAGCGGTCAA) or exon 4 (GCCCCGCGGCCACCGCATAC). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000, medium was changed after 24 h, and 48 h post-transfection, EGFP-expressing cells were selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and were seeded at one cell/well in a 96-well plate. Colonies were expanded and assessed for Bok immunoreactivity as described (Schulman et al., 2016). Multiple independent Bok KO cell lines for each exon target were used for all experiments.

cDNAs were subcloned from vectors containing mouse BokWT, mouse BokL34G, mouse Mcl-1WT, and human BakWT (Echeverry et al., 2013; Schulman et al., 2016), and were ligated to the 3’ end (C terminus) of V5-TurboID in place of the stop codon (Addgene #107169) (Branon et al., 2018) using Gibson assembly, creating TurboID-BokWT, TurboID-BokL34G, TurboID-Mcl-1, and TurboID-Bak, respectively; the authenticity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Genewiz).

Bok KO HeLa cells in 10 cm dishes were transfected (0.325–1.25 μg cDNA/22.5 μL Lipofectamine), and ∼16 h later, medium was changed, cells were incubated with 50 μM biotin for 2 h, washed thrice with ice-cold PBS, and harvested with ∼500 μL ice-cold lysis buffer for IP as described (Schulman et al., 2016) or for streptavidin pull-down. To purify biotinylated proteins, lysates were incubated with 300μg/mL streptavidin C1 magnetic beads (ThermoFisher) for ∼16 h at 4°C, and beads were washed stringently with buffers containing SDS and detergents as described (Firat-Karalar and Stearns, 2015). All samples were re-suspended in gel loading buffer, boiled for 5 min, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. For pilot experiments (Figures 1B, 3A), lysates were transferred to nitrocellulose, and biotinylated species were detected by incubation with 100 ng/mL purified streptavidin (which binds to biotin with high affinity) for 1 h, anti-streptavidin for ∼16 h, and then developed similarly to other immunoblots. Once biotinylation was confirmed, purified biotinylated proteins were again subjected to SDS-PAGE until the dye front ran ∼2 cm, and lanes were excised for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (described in Supplementary Methods).

The MS data for each TurboID fusion protein underwent two stages of refinement (depicted in Supplementary Figure 3). In the first stage, for each experiment (i) proteins were excluded from further analysis if the q value > 0.01, (ii) keratin proteins were excluded, and (iii) proteins were included only if they were unique or if abundance was 5× increased in TurboID samples versus control samples (abundance = peptide spectrum match number divided by the total number of amino acids in the parent protein). In the second stage, lists of included proteins from a number (n) of independent experiments were compared, and proteins were considered to be “strongly labeled” if they were present in multiple (e.g., at least 6/7) lists. For each TurboID construct, lists of proteins after the first stage of refinement, plus the strongly labeled proteins, are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–4. Protein localization is described in the Supplementary Methods.

Lysates were prepared with ice-cold lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, IPs were prepared with Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B beads (GE Healthcare), and lysates and washed IPs were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described (Schulman et al., 2013, 2016).

We selected HeLa cells for TurboID as they are relatively easy to transfect and have been used previously in proximity labeling studies (Roux et al., 2012). To facilitate analysis of the Bok interactome, we deleted endogenous Bok by CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of Bok exons 2 and 4, with no off-target effects on expression of other Bcl-2 family members or IP3Rs (Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, imaging of these Bok KO cells indicated that Bok deletion causes mitochondrial fragmentation (Supplementary Figure 1B), with image quantification revealing significantly reduced mitochondrial particle length, area, and aspect ratio, while mitochondrial width was unchanged (Supplementary Figures 1C–F). Similar effects of Bok KO have been observed in MEFs (Schulman et al., 2019).

We performed TurboID experiments using wild-type Bok (BokWT) and an L34G Bok mutant that cannot bind IP3Rs (BokL34G) (Schulman et al., 2013) to determine if the proteins proximal to Bok are dependent on the interaction of Bok and IP3Rs. Both BokWT and BokL34G were fused to V5-tagged TurboID, creating TurboID-BokWT and TurboID-BokL34G (T-BokWT and T-BokL34G, respectively, Figure 1A). TurboID was fused to the N- termini to minimize the possibility of mislocalization, since Bok is localized to the ER by its C-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain (Echeverry et al., 2013).

Expression of T-BokWT and T-BokL34G in Bok KO HeLa cells resulted in an exogenous biotin-dependent smear of biotinylated species (Figure 1B, lanes 5, 6). The two prominent bands at ∼130 and 70 kDa, seen in all lanes, were identified by MS analysis as the endogenously biotinylated proteins pyruvate carboxylase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase (Tong, 2013), respectively. It is also noteworthy that the immunoreactivity of the T-Bok constructs increased after the addition of biotin (Figure 1B, lanes 2–3 versus 5–6), consistent with previous findings that TurboID constructs are stabilized by exogenous biotin (Branon et al., 2018).

To determine how well the T-Bok constructs interact with IP3Rs, we examined their ability to co-IP with endogenous IP3Rs (Figure 1C). This showed, as expected, that T-BokWT, but not T-BokL34G, binds IP3Rs (lane 2 versus 3) (Schulman et al., 2013). Importantly, the difference between pre-IP versus post-IP lysates suggest that most of T-BokWT is associated with IP3Rs (lane 5 versus 8).

From cells incubated with biotin as in Figure 1B (lanes 4–6), biotinylated proteins were purified using streptavidin-coated beads followed by SDS-PAGE, trypsin digestion, and MS analysis (Supplementary Figure 2). The initial list of proteins obtained for each T-Bok sample underwent two stages of data refinement to remove non-specifically interacting proteins (Supplementary Figure 3). The first stage excluded any proteins that were also found in control (non-transfected) samples analyzed on the same day, and the second stage included proteins present only in multiple independent experiments; for T-BokWT and T-BokL34G, only proteins present in at least 6/7 and 4/5 experiments, respectively, were included. These “strongly labeled” proteins were categorized for subcellular localization (Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and Figure 2A) and were compared to determine similarities and differences (Figure 2B). Interestingly, fewer proteins were identified by T-BokL34G than T-BokWT (28 versus 90 proteins, respectively), Bok was present on both lists due to self-biotinylation, and only T-BokWT labeled IP3Rs (Itpr1-3), indicating that the approach is valid.

T-BokWT was proximal to a broad array of proteins at different sites (Figure 2A), although ER and nuclear localizations were predominant (33 and 32% of labeled proteins, respectively). While the identification of ER proteins is to be expected due to Bok’s constitutive ER localization with IP3Rs (Echeverry et al., 2013; Schulman et al., 2016), the high number of nuclear proteins is surprising. However, proteins were assigned up to 3 locations, and many of the multi-located proteins included a nuclear assignment. Additionally, several of the nucleus-assigned proteins were nuclear membrane proteins, which is understandable given the contiguous nature of the ER and nuclear membrane (English and Voeltz, 2013). Also in the T-BokWT protein list were several PM (16%), cytosolic (16%), Golgi (13%), and mitochondrial proteins (11%).

More detailed consideration of proteins identified for T-BokWT (Figure 2B) revealed clusters of proteins known to regulate mitochondrial fission (Drp1, Mff, Inf2, Akap1, etc.) (Czachor et al., 2016; Kraus et al., 2021) and ER-PM contact sites (Itpr1-3, Stim1, Vapa, Vapb, etc.) (Murphy and Levine, 2016; Prole and Taylor, 2019). Drp1 is a GTPase well-known for being the main effector protein for mitochondrial fission (Kraus et al., 2021), Stim1 is an ER protein involved in store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) and ER-PM junctions (Prole and Taylor, 2019), and Akap1 is a mitochondrial membrane scaffolding protein that regulates a variety of mitochondrial functions (Czachor et al., 2016). Notably, no Bcl-2 family members were labeled by T-BokWT aside from Mcl-1. Surprisingly, we did not detect uridine monophosphate synthetase, despite recent reports that Bok regulates uridine metabolism by enhancing its activity (Srivastava et al., 2019), or key proteins involved in mitochondrial fusion (e.g., Mfn1/2), despite evidence that Bok can regulate fusion rate (Schulman et al., 2019).

The result that T-BokWT strongly labeled three times as many proteins as T-BokL34G was initially perplexing. However, it is likely that T-BokL34G is rapidly turned over because it cannot interact with IP3Rs (Schulman et al., 2016), and this may impair biotin ligase activity. Indeed, to achieve comparable expression and biotinylation required using twice as much T-BokL34G cDNA than T-BokWT cDNA (Figures 1B,C). Nevertheless, the protein list for T-BokL34G overlapped significantly with that of T-BokWT, suggesting that the mutant protein still localizes to the ER despite not binding to IP3Rs. A comparison of the two T-Bok constructs with a lower threshold for T-BokL34G (i.e., addition of proteins in 3/5 experiments, Supplementary Figure 4) identified more proteins that were also present in the T-BokWT list, including more of the proteins involved in mitochondrial fission (Inf2 and Mff). Overall, the interactome of T-BokL34G has some similarities to that of T-BokWT, but also major differences. Some of these differences may result from localization of T-BokWT to IP3Rs, but likely also reflect the marked differences in T-BokWT and T-BokL34G stability.

To assess T-BokWT proximity labeling specificity and better understand other Bcl-2 family members, we generated TurboID constructs for Bak, which localizes predominantly to mitochondria, and Mcl-1, which also localizes to mitochondria, but is also found at the ER and in the cytosol (Kale et al., 2018). Both TurboID-Bak (T-Bak) and TurboID-Mcl-1 (T-Mcl-1) expressed and induced biotinylation similarly to T-BokWT (Figure 3A).

TurboID was performed in Bok KO HeLa cells to allow for direct comparison with T-BokWT results. The possible impact of the presence of endogenous Mcl-1 and Bak in these cells (Supplementary Figure 1A) on labeling was not examined in this study. Localization of strongly labeled proteins (Figure 3B and Supplementary Tables 3, 4) demonstrates that both T-Bak and T-Mcl-1 did not identify as many ER proteins as T-BokWT (9, 10, and 33%, respectively), as expected. In order of abundance, T-Bak identified mitochondrial (35%), cytosolic (31%), and nuclear proteins (24%), whereas T-Mcl-1 identified nuclear (41%), cytosolic (36%), and mitochondrial proteins (18%). Again, as expected, both T-Bak and T-Mcl-1 labeled more mitochondrial proteins than T-BokWT.

Comparison of the protein lists for the three Bcl-2 family proteins (Figure 3C) demonstrated that each interactome is quite distinct, although there was significant overlap. In particular, Inf2 and Mavs, which are involved in mitochondrial fission (Kraus et al., 2021) and fusion (Koshiba et al., 2011), respectively, were present in all lists, as were Akap1 and Stim1. Also, both T-BokWT and T-Bak labeled Mcl-1, which is consistent with studies indicating that Bok (Hsu et al., 1997) and Bak (Cuconati et al., 2003) can physically interact with Mcl-1.

The protein lists for T-Bak and T-BokWT showed some overlap, and notably, the mitochondrial fission proteins Mff and Mtfr1 were common to both. Many of the proteins unique to the T-Bak list were mitochondrial proteins, and not surprisingly, Bax was among them (Kale et al., 2018). T-Mcl-1 showed only minor overlap with T-BokWT, and uniquely labeled Vdac1/2, consistent with findings that Mcl-1 physically interacts with Vdac and can facilitate Vdac-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Huang et al., 2014). Overall, the discrete proximity labeling patterns for T-BokWT, T-Bak, and T-Mcl-1 validate the TurboID approach, and comparison of the three protein lists reflects the complexity of the Bcl-2 family network and identifies potential novel interactions.

Since T-BokWT labeled Mcl-1 but no other Bcl-2 family member (Figure 2), we wondered whether this signified mere proximity between Bok and Mcl-1, or whether they interact directly. Interestingly, when co-expressed, BokWT did co-IP with 1F-Mcl-1 (Mcl-1 with an N-terminal Flag tag), and 1F-Mcl-1 increased Bok immunoreactivity (Figure 4A, lane 4), suggesting that the interaction stabilizes Bok. This was still observed with BokL34G (lane 8), indicating that it was not mediated by the BH4 domain of Bok that is critical for the interaction with IP3Rs (Schulman et al., 2013), but was markedly reduced for BokΔTM (lane 6), indicating that Bok localization to membranes is important for the interaction, or that it is directly mediated by the Bok TM domain itself (Lucendo et al., 2020). Under the same conditions, endogenous Bok did not co-IP with endogenous Mcl-1 (Supplementary Figure 5), as noted in some other studies (Echeverry et al., 2013; Schulman et al., 2016), indicating that the Bok-Mcl-1 interaction is relatively weak and is only detectable upon protein overexpression. Nevertheless, the interaction between exogenous BokWT and 1F-Mcl-1 has functional significance, as BokWT-mediated increases in cleaved caspase-3 (cC3), were suppressed significantly by 1F-Mcl-1 (Figure 4B, lanes 3 versus 4). Interestingly, BokΔTM increased cC3 levels similarly to BokWT, but the effect of BokΔTM was not significantly suppressed by 1F-Mcl-1 (lanes 5 versus 6), consistent with their much weaker physical interaction (Figure 4A, lane 6). Further, BokL34G induced significantly more cC3 than BokWT (Figure 4B, lanes 3 versus 7), presumably because BokL34G is not sequestered by IP3Rs, although Mcl-1 suppressed the response (lanes 7 versus 8). Overall, these data indicate that the proximity labeling approach can identify fleeting protein-protein interactions of functional significance that might not be detectable by conventional (e.g., co-IP) analysis of endogenous proteins, and that Mcl-1 likely mediates or modulates the effects of Bok. It should be noted that in these studies, we utilized mouse Bok and Mcl-1 expressed in human HeLa cells. However, mouse and human Bok and Mcl-1 amino acid sequences are 95% and 76% identical, respectively, and human Bok and Mcl-1 co-IP like their mouse counterparts when over-expressed in Bok KO HeLa cells (Figure 4C), indicating that the mouse and human proteins behave identically in the HeLa cell context.

Since Drp1 is a crucial mediator of mitochondrial fission (Kraus et al., 2021) and was strongly labeled by T-BokWT (Figure 2), we sought to determine if Bok regulates Drp1 activity, which can be measured through Drp1 phosphorylation (pDrp1). pDrp1S616 is associated with increased mitochondrial fission, whereas pDrp1S637 is associated with decreased mitochondrial fission (Kraus et al., 2021). Using validated antibodies, we examined pDrp1 levels among HeLa cell lines and found that pDrp1S616 and pDrp1S637 levels were not substantially changed by Bok deletion (Supplementary Figure 6). Likewise, given that several proteins related to intracellular Ca2+ signaling at the ER or at ER-PM contact sites were labeled by T-BokWT, we sought to determine whether Bok KO altered Ca2+ mobilization. However, WT and Bok KO HeLa cells responded essentially identically to trypsin (Supplementary Figure 7), indicating that Bok KO does not affect Ca2+ signaling.

Proximity labeling was developed to identify the interactome for a given protein by labeling transient interactions and nearby proteins, providing an alternative to the traditional co-IP or co-purification approaches that reveal only the highest affinity protein-protein interactions (Roux et al., 2012). Here we show that TurboID can efficiently and specifically identify the interactomes for Bok, Mcl-1, and Bak. T-Bok-labeled proteins are predominantly found in the ER, consistent with Bok’s reported subcellular localization. In contrast, T-Bak and T-Mcl-1 mostly labeled mitochondrial and nuclear proteins, respectively, consistent with Bak’s known localization to the mitochondrial membrane, and a more mixed distribution for Mcl-1 (Kale et al., 2018).

While the proteins labeled by T-BokWT were predominantly ER-residents, protein groups in other locations were also identified, indicating a role for Bok at the interface of the ER and other organelles. As Bok deletion causes mitochondrial fragmentation, we particularly focused on mitochondrial proteins. Mitochondria-ER contacts (MERCs), sometimes referred to as mitochondrial-associated membranes (MAMs) when isolated in biophysical protocols, are transient microdomains where ER and mitochondria come within 10-80 nm of each other (Giacomello and Pellegrini, 2016). Several studies report that MERCs are essential for numerous signaling processes, including Ca2+ transfer, lipid trafficking/metabolism, and regulation of cell death or survival (Perrone et al., 2020), and interestingly, a recent study suggests that Bok is integral to the stability of MERCs/MAMs (Carpio et al., 2021). However, aside from IP3Rs, T-Bok did not label any of the proteins reported to be important in the coupling of the ER to mitochondria at MERCs/MAMs, including Vdac1, Grp75, or Mfn2 (Perrone et al., 2020). Rather, T-Bok identified several proteins important for mitochondrial fission, including Drp1, Mff, Akap1, and Inf2 (Czachor et al., 2016; Kraus et al., 2021). This suggests that the role of Bok at the interface of ER and mitochondria is not to maintain MERC/MAM structure or function, but rather to regulate mitochondrial fission. This notion is consistent with findings that the ER is highly involved in mitochondrial fission (Perrone et al., 2020), and that ER projections can wrap around mitochondria to mediate the division process (Friedman et al., 2011).

Could an inhibitory effect of Bok on key fission mediators, such as Drp1, explain the mitochondrial fragmentation seen in Bok KO cells? This is a distinct possibility, since although we were unable to see an effect of Bok KO on Drp1 levels or phosphorylation (a measure of Drp1 activity), Drp1 function is regulated by several post-translational modifications aside from phosphorylation (Chang and Blackstone, 2010), and other fission mediators (e.g., Inf2, Mff), could also be regulated by interfacing with Bok. Further, as indicated below, Mcl-1 could mediate effects of Bok on mitochondrial fission.

That the protein list for T-BokL34G, which does not bind IP3Rs, was considerably shorter than that for T- BokWT and other TurboID-fusion proteins, is likely explained by the instability of T-BokL34G (Schulman et al., 2016); presumably, the rapid turnover of T- BokL34G impairs its ability to elicit significant biotinylation. Unfortunately, this unexpected finding made it impossible to accurately assess the effect of localization to IP3Rs on the T-BokWT interactome. Nevertheless, it is interesting that almost all of the proteins strongly labeled by T-BokL34G were also labeled by T-BokWT, indicating that T-BokL34G is localized similarly to T-BokWT. This is consistent with the ability of BokL34G to restore normal mitochondrial morphology when introduced into Bok KO cells (Schulman et al., 2019).

The overlap in proteins labeled by T-Bok, T-Bak, and T-Mcl-1 is intriguing and may open new research avenues. For example, the scaffolding protein Akap1, which modulates numerous signaling pathways at the mitochondrial surface (Czachor et al., 2016), was labeled by T-Bok, T-Bak, and T-Mcl-1, suggesting that it may be a general mediator of Bcl-2 family-related processes at the mitochondrial membrane. Likewise, all 3 proteins labeled Stim1, an ER membrane protein involved in ER-PM coupling for SOCE (Prole and Taylor, 2019). To the best of our knowledge, interactions between Stim1 and Bok, Bak, or Mcl-1 have not been previously reported, and although we did not detect an effect of Bok KO on Ca2+ signals that include SOCE, Bcl-2 does regulate SOCE (Vanden Abeele et al., 2002; Chiu et al., 2018), suggesting that many Bcl-2 family members may regulate this pathway. Lastly, both T-Bok and T-Bak identified Mcl-1, and Mcl-1 was the only Bcl-2 family member identified by T-Bok. This is consistent with the widespread distribution of Mcl-1 (Kale et al., 2018) and indicates that analysis of the Bok-Mcl-1 interaction may be a fruitful approach to solving the puzzle of how Bok acts within the cell.

Indeed, we were able to show that Bok and Mcl-1 interact physically, albeit only when overexpressed, and that this binding has functional consequences, since Mcl-1 inhibited Bok-mediated apoptotic signaling. These finding are broadly consistent with those of others (Hsu et al., 1997; Stehle et al., 2018; Lucendo et al., 2020), but with some significant differences. In particular, our findings that BokΔTM mediates apoptotic signaling similarly to BokWT contradict a recent study (Stehle et al., 2018) indicating that the TM domain of Bok is required for apoptosis, although this could be accounted for by the different experimental systems used. The Bok-Mcl-1 interaction also provides a potential mechanism for Bok to regulate mitochondrial morphology, since Mcl-1 regulates mitochondrial fission, at least in part, by acting through Drp1 (Moyzis et al., 2020). As we find that T-BokWT strongly labels both Mcl-1 and Drp1, it is possible that Bok inhibits mitochondrial fission rate by modulating the action of Mcl-1. Thus, upon Bok KO, fission rate would be accelerated, explaining the mitochondrial fragmentation observed in Bok KO MEFs (Schulman et al., 2019) and Hela cells (Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, in our previous studies on the mechanism of Bok KO-induced mitochondrial fragmentation we could not measure mitochondrial fission rate directly, but found that Bok KO inhibits fusion rate. Since T-Bok identified mitochondrial fission mediators but not fusion mediators, we speculate that the effect of Bok KO on fusion rate may be an adaptation to a direct effect of Bok KO on fission mediators and fission rate.

It is important to note that the proteins identified by TurboID constructs reveal proximity, but not necessarily functional interactions. As a “shotgun” approach to the study of possible protein-protein interactions, deriving meaning from proximity labeling still requires functional studies, such as those we performed with Bok and Mcl-1. In that particular case, we were able to demonstrate functional consequences from the Bok-Mcl-1 interaction, but it is also inevitable that some, perhaps most, identified proteins will not interact physically, and other methods (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9-mediated protein KO) will be required to establish significance of proximity. Overall, we hope that this study serves to drive further research into Bok and Bcl-2 family interactions, with outcomes that will lead to a better understanding of Bok and cell physiology.

Going forward, it will be particularly interesting to determine if stably expressed Bcl-2 family proteins biotinylate more specifically than the transient expression method used in the present study, how the interactomes might change when apoptosis is triggered, how endogenous Mcl-1 and Bak impact the labeling seen with T-Mcl-1 and T-Bak, and how certain proteins strongly labeled by T-Bok might help explain the various putative roles of Bok. In particular, the interaction with anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 and thus the Bcl-2 family network may explain how manipulating Bok levels can have various effects on apoptotic signaling (Naim and Kaufmann, 2020; Shalaby et al., 2020), the identification of Drp1 and other fission mediators may explain how Bok can influence mitochondrial morphology (Schulman et al., 2019), and the identification of ER-PM and ER-Golgi junctional proteins (e.g., Stim1, Vapa and Vapb) suggest new possible roles for Bok in inter-organelle contact sites.

The authors acknowledge that the data presented in this study must be deposited and made publicly available in an acceptable repository, prior to publication. Frontiers cannot accept a manuscript that does not adhere to our open data policies.

LS performed, guided, and analyzed all the experiments shown and was the primary author of the manuscript. CB designed and implemented screening of HeLa Bok KO cell lines and assisted with image acquisition for Supplementary Figure 1B. RW conceived and coordinated the study with substantial editorial input into the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The research performed in this article was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants DK107944, GM121621, and GM134638.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Thomas Kaufmann, University of Bern, Switzerland, for providing anti-Bok and cDNAs, Ebbing de Jong for assistance with mass spectrometry analysis, Bruce Knutson for providing TurboID cDNA and helpful suggestions, Jacqualyn Schulman for assistance with gRNA vector design, and Katherine Keller and Pranav Suri for technical assistance and helpful suggestions.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.689951/full#supplementary-material

BioID/TurboID, proximity-dependent biotin identification; Bok, Bcl-2-related ovarian killer; cC3, cleaved caspase-3; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; IP, immunoprecipitation; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; KO, knock-out; MAM, mitochondrial-associated membrane; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; MERC, mitochondria-ER contact site; MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; MS, mass spectrometry; pDrp1, phosphorylated Drp1; PM, plasma membrane; SOCE, store-operated calcium entry; T-Bak, TurboID-Bak; T-Bok, TurboID-Bok; T-Mcl-1, TurboID-Mcl-1; TM, transmembrane.

Branon, T. C., Bosch, J. A., Sanchez, A. D., Udeshi, N. D., Svinkina, T., Carr, S. A., et al. (2018). Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 880–887. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4201

Carpio, M. A., Means, R. E., Brill, A. L., Sainz, A., Ehrlich, B. E., and Katz, S. G. (2021). BOK controls apoptosis by Ca(2+) transfer through ER-mitochondrial contact sites. Cell Rep. 34:108827. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108827

Carpio, M. A., Michaud, M., Zhou, W., Fisher, J. K., Walensky, L. D., and Katz, S. G. (2015). BCL-2 family member BOK promotes apoptosis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 7201–7206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421063112

Chang, C. R., and Blackstone, C. (2010). Dynamic regulation of mitochondrial fission through modification of the dynamin-related protein Drp1. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1201, 34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05629.x

Chiu, W. T., Chang, H. A., Lin, Y. H., Lin, Y. S., Chang, H. T., Lin, H. H., et al. (2018). Bcl(-)2 regulates store-operated Ca(2+) entry to modulate ER stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Discov. 4:37.

Chong, S. J. F., Marchi, S., Petroni, G., Kroemer, G., Galluzzi, L., and Pervaiz, S. (2020). Noncanonical Cell Fate Regulation by Bcl-2 Proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 537–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.03.004

Cuconati, A., Mukherjee, C., Perez, D., and White, E. (2003). DNA damage response and MCL-1 destruction initiate apoptosis in adenovirus-infected cells. Genes Dev. 17, 2922–2932. doi: 10.1101/gad.1156903

Czachor, A., Failla, A., Lockey, R., and Kolliputi, N. (2016). Pivotal role of AKAP121 in mitochondrial physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 310, C625–8.

D’Orsi, B., Engel, T., Pfeiffer, S., Nandi, S., Kaufmann, T., Henshall, D. C., et al. (2016). Bok Is Not Pro-Apoptotic But Suppresses Poly ADP-Ribose Polymerase-Dependent Cell Death Pathways and Protects against Excitotoxic and Seizure-Induced Neuronal Injury. J. Neurosci. 36, 4564–4578. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3780-15.2016

Echeverry, N., Bachmann, D., Ke, F., Strasser, A., Simon, H. U., and Kaufmann, T. (2013). Intracellular localization of the BCL-2 family member BOK and functional implications. Cell Death Differ. 20, 785–799. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.10

English, A. R., and Voeltz, G. K. (2013). Endoplasmic reticulum structure and interconnections with other organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a013227. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013227

Firat-Karalar, E. N., and Stearns, T. (2015). Probing mammalian centrosome structure using BioID proximity-dependent biotinylation. Methods Cell Biol. 129, 153–170. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.03.016

Friedman, J. R., Lackner, L. L., West, M., DiBenedetto, J. R., Nunnari, J., and Voeltz, G. K. (2011). ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science 334, 358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385

Giacomello, M., and Pellegrini, L. (2016). The coming of age of the mitochondria-ER contact: a matter of thickness. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1417–1427. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.52

Hsu, S. Y., Kaipia, A., McGee, E., Lomeli, M., and Hsueh, A. J. (1997). Bok is a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein with restricted expression in reproductive tissues and heterodimerizes with selective anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 12401–12406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12401

Huang, H., Shah, K., Bradbury, N. A., Li, C., and White, C. (2014). Mcl-1 promotes lung cancer cell migration by directly interacting with VDAC to increase mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and reactive oxygen species generation. Cell Death Dis. 5:e1482. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.419

Kale, J., Osterlund, E. J., and Andrews, D. W. (2018). BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 25, 65–80. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.186

Ke, F., Voss, A., Kerr, J. B., O’Reilly, L. A., Tai, L., Echeverry, N., et al. (2012). BCL-2 family member BOK is widely expressed but its loss has only minimal impact in mice. Cell Death Differ. 19, 915–925. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.210

Koshiba, T., Yasukawa, K., Yanagi, Y., and Kawabata, S. (2011). Mitochondrial membrane potential is required for MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling. Sci. Signal. 4:ra7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001147

Kraus, F., Roy, K., Pucadyil, T. J., and Ryan, M. T. (2021). Function and regulation of the divisome for mitochondrial fission. Nature 590, 57–66. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03214-x

Llambi, F., Wang, Y. M., Victor, B., Yang, M., Schneider, D. M., Gingras, S., et al. (2016). BOK Is a Non-canonical BCL-2 Family Effector of Apoptosis Regulated by ER-Associated Degradation. Cell 165, 421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.026

Lucendo, E., Sancho, M., Lolicato, F., Javanainen, M., Kulig, W., Leiva, D., et al. (2020). Mcl-1 and Bok transmembrane domains: unexpected players in the modulation of apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 27980–27988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008885117

Moyzis, A. G., Lally, N. S., Liang, W., Leon, L. J., Najor, R. H., Orogo, A. M., et al. (2020). Mcl-1-mediated mitochondrial fission protects against stress but impairs cardiac adaptation to exercise. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 146, 109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.07.009

Murphy, S. E., and Levine, T. P. (2016). (VAP), a Versatile Access Point for the Endoplasmic Reticulum: review and analysis of FFAT-like motifs in the VAPome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1861, 952–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.02.009

Naim, S., and Kaufmann, T. (2020). The Multifaceted Roles of the BCL-2 Family Member BOK. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:574338. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.574338

Pearce, M. M., Wang, Y., Kelley, G. G., and Wojcikiewicz, R. J. (2007). SPFH2 mediates the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and other substrates in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20104–20115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m701862200

Perrone, M., Caroccia, N., Genovese, I., Missiroli, S., Modesti, L., Pedriali, G., et al. (2020). The role of mitochondria-associated membranes in cellular homeostasis and diseases. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 350, 119–196. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2019.11.002

Prole, D. L., and Taylor, C. W. (2019). Structure and Function of IP3 Receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 11:a035063. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035063

Roux, K. J., Kim, D. I., Raida, M., and Burke, B. (2012). A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 196, 801–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112098

Schulman, J. J., Szczesniak, L. M., Bunker, E. N., Nelson, H. A., Roe, M. W., and Wagner, L. E. II (2019). Bok regulates mitochondrial fusion and morphology. Cell Death Differ. 26, 2682–2694. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0327-4

Schulman, J. J., Wright, F. A., Han, X., Zluhan, E. J., Szczesniak, L. M., and Wojcikiewicz, R. J. (2016). The Stability and Expression Level of Bok Are Governed by Binding to Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 11820–11828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m115.711242

Schulman, J. J., Wright, F. A., Kaufmann, T., and Wojcikiewicz, R. J. (2013). The Bcl-2 protein family member Bok binds to the coupling domain of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and protects them from proteolytic cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 25340–25349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m113.496570

Shalaby, R., Flores-Romero, H., and Garcia-Saez, A. J. (2020). The Mysteries around the BCL-2 Family Member BOK. Biomolecules 10:1638. doi: 10.3390/biom10121638

Srivastava, R., Cao, Z., Nedeva, C., Naim, S., Bachmann, D., Rabachini, T., et al. (2019). BCL-2 family protein BOK is a positive regulator of uridine metabolism in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 15469–15474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904523116

Stehle, D., Grimm, M., Einsele-Scholz, S., Ladwig, F., Johanning, J., Fischer, G., et al. (2018). Contribution of BH3-domain and Transmembrane-domain to the Activity and Interaction of the Pore-forming Bcl-2 Proteins Bok. Bak, and Bax. Sci. Rep. 8:12434.

Tong, L. (2013). Structure and function of biotin-dependent carboxylases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 70, 863–891. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1096-0

Vanden Abeele, F., Skryma, R., Shuba, Y., Van Coppenolle, F., Slomianny, C., Roudbaraki, M., et al. (2002). Bcl-2-dependent modulation of Ca(2+) homeostasis and store-operated channels in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Cell 1, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00034-x

Keywords: Bcl-2 related ovarian killer, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family, proximity labeling, myeloid-cell leukemia 1, apoptosis

Citation: Szczesniak LM, Bonzerato CG and Wojcikiewicz RJH (2021) Identification of the Bok Interactome Using Proximity Labeling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:689951. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.689951

Received: 01 April 2021; Accepted: 06 May 2021;

Published: 31 May 2021.

Edited by:

Jochen H. M. Prehn, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, IrelandReviewed by:

Thomas Kaufmann, University of Bern, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2021 Szczesniak, Bonzerato and Wojcikiewicz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Richard J. H. Wojcikiewicz, d29qY2lraXJAdXBzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.