- 1Department of Physiology, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Pathogenesis and Prevention of Neurological Disorders and State Key Disciplines: Physiology, School of Basic Medicine, Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Proteomics, Beijing Proteome Research Center, National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing), Beijing Institute of Lifeomics, Beijing, China

- 3CAS Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 4Peixian People’s Hospital, Xuzhou, China

Developmental down-regulation protein 8 (NEDD8), expressed by neural progenitors, is a ubiquitin-like protein that conjugates to and regulates the biological function of its substrates. The main target of NEDD8 is cullin-RING E3 ligases. Upregulation of the neddylation pathway is closely associated with the progression of various tumors, and MLN4924, which inhibits NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE), is a promising new antitumor compound for combination therapy. Here, we summarize the latest progress in anticancer strategies targeting the neddylation pathway and their combined applications, providing a theoretical reference for developing antitumor drugs and combination therapies.

Introduction

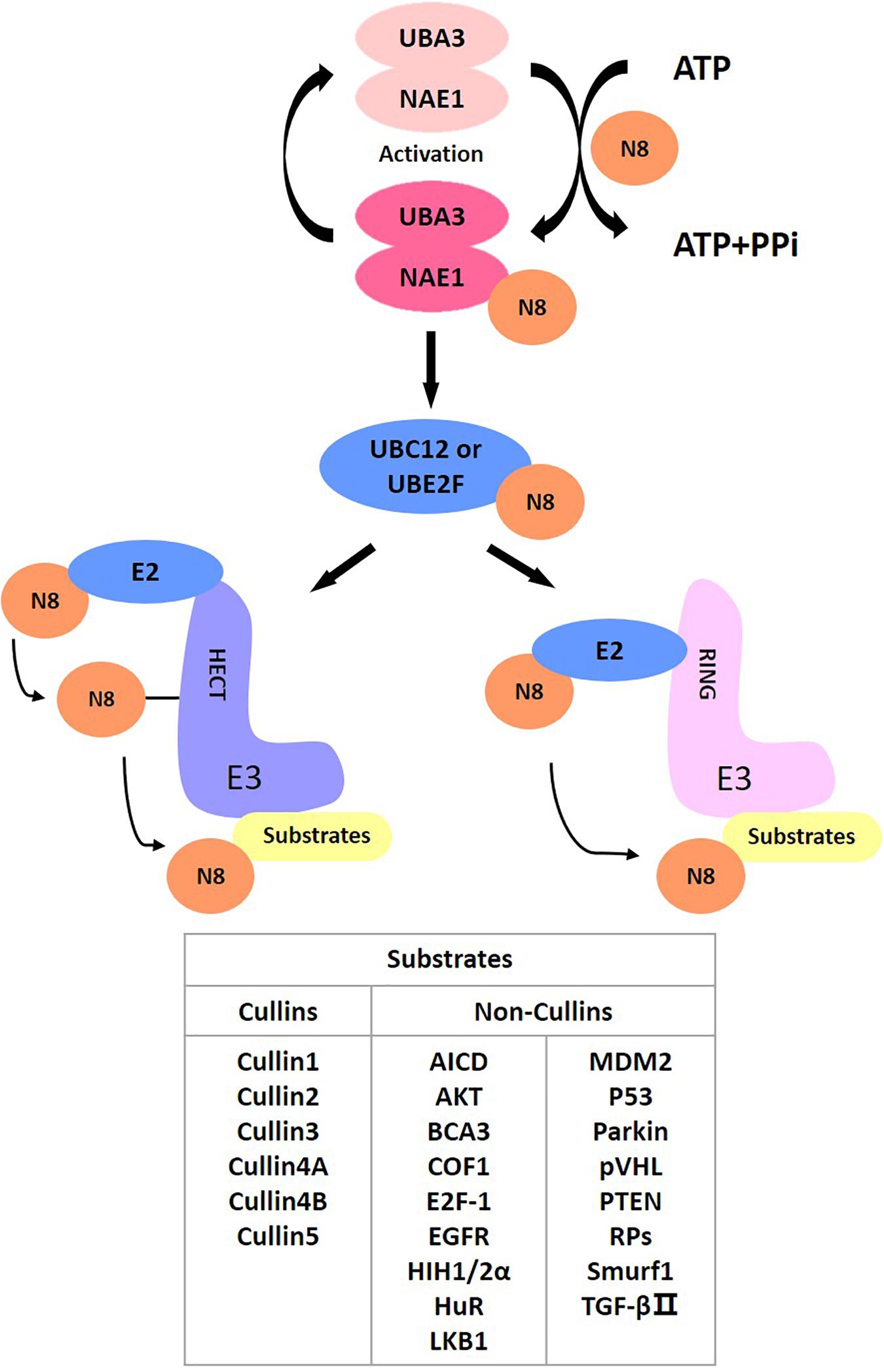

As a post-translational modification, protein neddylation refers to a process where substrate proteins are tagged with a ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8 and participate in cellular activity by regulating protein function. NEDD8 encodes an 81-amino acid polypeptide, which is highly homologous to ubiquitins and is connected to its substrates by forming isopeptide chains. For NEDD8, this linkage occurs between Gly-76 at NEDD8’s C-terminus and the Lys-48 residue of the substrates (Kamitani et al., 1997). Different from ubiquitin, as a precursor, NEDD8 is initially synthesized with five additional downstream residues of Gly-76 that must be cracked by a C-terminal hydrolase (Rabut and Peter, 2008), mainly ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L3 (UCH-L3) (Johnston et al., 1997) and NEDD8 specific-protease cysteine (NEDP1) (Gan-Erdene et al., 2003; Mendoza et al., 2003). After that, an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and an E1 NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) first adenylate and activate mature NEDD8, respectively. NAE is a heterodimer comprising NAE1 (also called APPBP1) and UBA3 (also called NAEβ) (Bohnsack and Haas, 2003; Walden et al., 2003; Kurz et al., 2008). Next, activated NEDD8 transfers to one of two NEDD8-conjugating E2 enzymes (UBC12/UBE2M or UBE2F) (Kamitani et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2005). Finally, the E3 ligase catalyzes the production of isomers of the C-terminal Gly-76 and lysine residue of the substrate protein via covalent attachment, ultimately transferring NEDD8 to the substrates to complete the neddylation process (Kamitani et al., 1997).

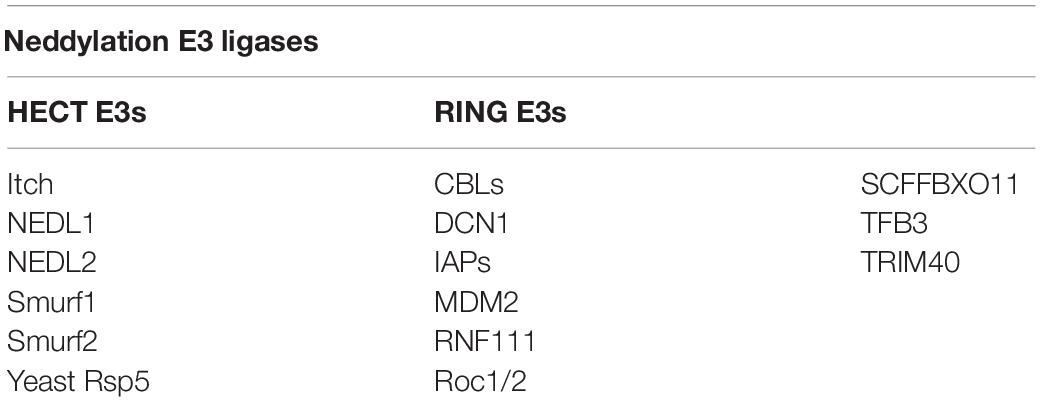

E3 ubiquitin ligases are numerous, but 10 NEDD8 E3 ligases are available. Except for defective cullin neddylation 1 (DCN1) (Kurz et al., 2005, 2008) and DCN1-like proteins (Kurz et al., 2008; Meyer-Schaller et al., 2009), most of these contain the novel gene (RING) domain structure. The 10 NEDD8 E3 ligases are DCN1, RING-box proteins 1 (RBX1) and RBX2 [also known as regulators of cullin 1 (ROC1) and ROC2/SAG, respectively] (Duan et al., 1999; Kamura et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2009), murine double minute 2 (MDM2) (Xirodimas et al., 2004), casitas B-lineage lymphoma (c-CBL) (Oved et al., 2006; Zuo et al., 2013), SCFFBXO11 (Zuo et al., 2013), ring finger protein 111 (RNF111) (Ma et al., 2013), inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) (Broemer et al., 2010), TFB3 (TFIIH/NER complex subunit TFB3) (Rabut et al., 2011), and tripartite motif containing 40 (TRIM40) (Noguchi et al., 2011). The RING-type neddylation ligase acts as a scaffold to bind the E2 ubiquitin complex directly to the substrate, enhancing ubiquitin transfer to the substrate protein (Metzger et al., 2014). Different from RING-type neddylation ligases, HECT-type neddylation ligases act catalytically by constituting a thioester bond with the C-terminal lobe of the HECT domain before the transfer of ubiquitin to its intended substrate (Berndsen and Wolberger, 2014; Zheng and Shabek, 2017). HECT-type neddylation ligases remain less defined than RING-type neddylation ligases, such as Yeast Rsp5, Itch (Li et al., 2016) (E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Itchy homolog), Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor 1 (Smurf1) (Xie et al., 2014), Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor 2 (Smurf2) (Shu et al., 2016), NEDL1 (NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 1) and NEDL2 (NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 1) (Qiu et al., 2016) (Table 1). Furthermore, all NEDD8 E3 ligases identified thus far can be used as ubiquitin E3 ligases (Zhao et al., 2014).

NEDD8 regulates the activities of substrates and participates in various signaling pathways, including cell proliferation, autophagy and transformation. Cullins are the most typical target proteins for neddylation. Typical substrates of cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) include proteins related to cell cycle regulation (e.g., Cyclin D/E, p21, p27, and WEE1) (Jia et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Hua et al., 2015; Paiva et al., 2015; Han et al., 2016; Lan et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016), apoptosis (e.g., BIM, NOXA, BIK, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, and c-FLIP) (Jia et al., 2011; Dengler et al., 2014; Godbersen et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2014; Knorr et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Czuczman et al., 2016; Leclerc et al., 2016; Tong et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017) and signal transduction pathways (e.g., HIF1α, REDD1, β-catenin, and Deptor) (Milhollen et al., 2010; Swords et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2012; Godbersen et al., 2014). Activation of CRLs contributes to cancer progression and degradation of their substrates (Xirodimas, 2008). In addition to cullins, several other targets of neddylation, involving tumor suppressor p53 (Xirodimas et al., 2004), Hu antigen R (HuR) (Stickle et al., 2004), von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL) (Stickle et al., 2004; Embade et al., 2012), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Oved et al., 2006), oncoprotein mouse double minute 2 (Mdm2) (Xirodimas et al., 2004), ribosomal proteins (Xirodimas et al., 2008), AKT, liver kinase B1 (LKB1) (Barbier-Torres et al., 2015), and PTEN (Xie et al., 2020), also effectively affect disease onset and progression. Therefore, targeting neddylation is an effective treatment for treating disease (Figure 1).

The substrate properties dictate the critical effect of neddylation in regulating biological processes and disease management. Recent studies have proposed the relevance of neddylation modifications in cell cycle control, DNA replication regulation, cell cycle progression and cell division. The neddylation pathway is hyperactivated during human cancer evolution (Zhou L. et al., 2019). Blocking the neddylation pathway has become an appealing anti-cancer treatment (Jiang and Jia, 2015). However, inhibiting the neddylation pathway significantly upregulates the expression of the T-cell minus modulator programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), possibly explaining the underlying resistance by evading immune surveillance checkpoints (Zhou S. et al., 2019). In this review, we summarize and analyse the promising potential of the targeted neddylation pathway as a new therapeutic method and effects of MLN4924/pevonedistat/TAK-924 treatment combined with other anticancer therapies, particularly those targeting the antitumor immune axis.

Target Proteins of Neddylation

After activation by neddylation, CRLs are the largest group of multi-unit E3 ubiquitin ligases responsible for ubiquitination, with roughly 20 percent of cellular proteins targeted then degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). The connection between NEDD8 and the lysine residues at the C-terminus of cullins activates CRLs (Sakata et al., 2007; Merlet et al., 2009), resulting in a structural alteration in the CRL complex: it adopts an open conformation to increase the entry of ubiquitinated substrates (Zheng et al., 2002; Duda et al., 2008; Saha and Deshaies, 2008). CRL is a multi-unit E3 comprising the following four components: cullin, a substrate recognition receptor, an adaptor protein, and one RING protein. There are eight cullins, including CUL1-3, CUL4A, CUL4B, CUL5, CUL7, and CUL9, which are the optimal substrates of the NEDD8 pathway; they have an evolutionarily conserved cullin homology domain (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). Every cullin protein is regarded as a molecular framework that promotes the combination of an adaptor protein, an N-terminal substrate receptor protein and a C-terminal RING protein (RBX1 or RBX2) to assemble a CRL (Feldman et al., 1997; Deshaies, 1999; Seol et al., 1999; Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). CRLs regulate many important biological processes, such as cell survival, apoptosis, genomic integrity, tumourigenesis and signal transduction, by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of critical zymolytes (Feldman et al., 1997; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006; Deshaies and Joazeiro, 2009).

Cullin neddylation activates CRLs, but some non-cullin proteins are also protein substrates of neddylation. In 1979, p53 was originally recognized as a factor related to transformation, and researchers have gradually discovered that it is closely associated with the tumor process. In vivo, p53 modifications occur mainly in pathways that promote ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation (Brooks and Gu, 2003). Research has indicated that p53 is an essential target for neddylation as well. The stability and function of p53, a tumor suppressor, are tightly regulated by post-translational modifications, including ubiquitylation and neddylation, in which the MDM2 oncoprotein plays a critical role. Mdm2, as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, binds directly to p53, thereby promoting its polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Nakamura et al., 2000). Furthermore, Mdm2 and F-box protein 11 (FBXO11) facilitate the combination of NEDD8 with p53, thus inhibiting p53 activity (Xirodimas et al., 2004; Abida et al., 2007). Several ribosomal proteins have been identified as potential NEDD8 substrates (Xirodimas et al., 2008). L11 was found to be neddylated by Mdm2 and deneddylated by NEDP1. MDM2-mediated L11 neddylation protects L11 from degradation, and both L11 (Lohrum et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003) and S14 (Zhou et al., 2013) bind to MDM2 and regulate p53 stability. Furthermore, the expression level of the RNA-binding protein HuR is associated with MDM2. HuR could be protected from degradation by neddylation through Mdm2-dependent stabilization (Embade et al., 2012). Other non-cullin substrates of neddylation have been reported, including the following: the tumor suppressor pVHL (Stickle et al., 2004); receptor proteins such as EGFR (Oved et al., 2006) and TGF-β type II receptor (Zuo et al., 2013); and transcriptional regulators such as HIF1α/HIF2α (Ryu et al., 2011), breast cancer-associated protein 3 (BCA3) (Gao et al., 2006), APP intracellular domain (AICD) (Lee et al., 2008), E2F-1 (Loftus et al., 2012), HECT-domain ubiquitin E3 ligase SMURF1 and RBR ubiquitin E3 ligase Parkin (Xie et al., 2014; Enchev et al., 2015). Additionally, new potential neddylation targets exist for LKB1 and Akt (Barbier-Torres et al., 2015).

In addition to the substrates mentioned above, Vogl et al. (2020) recently developed a series of NEDD8-ubiquitin-substrate spectra (sNUSP) that can be used to identify new substrates, such as COF1. The identification of a growing number of substrates suggests that neddylation plays an extensive role in cells with more complex cancer-promoting mechanisms than previously thought, providing a theoretical basis for targeting the neddylation pathway in the treatment of various diseases.

Targeting Protein Neddylation as an Anticancer Strategy

NEDD8 was initially identified as a gene whose expression is downregulated during development in the mouse brain (Kumar et al., 1992). However, it was demonstrated subsequently to exist in various mouse tissues and is highly conserved in vertebrate species and somewhat conserved in yeast (Kumar et al., 1993), suggesting that the neddylation pathway is essential during species evolution. Neddylation is a type of posttranslational modification that modulates substrate protein activity. Neddylation modification is catalyzed by an NAE (E1), a NEDD8-conjugating enzyme (E2), and a NEDD8 ligase (E3); these factors link a ubiquitin-like molecule, NEDD8, to the lysine residues of the substrate protein. Accumulating evidence shows that NEDD8 is overexpressed in some human diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders (Dil Kuazi et al., 2003; Mori et al., 2005) and cancers (Chairatvit and Ngamkitidechakul, 2007; Salon et al., 2007). Thus, targeting protein neddylation has recently been recognized as a popular anticancer method (Watson et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2018). We summarized previous and recent findings in Table 2.

NEDD8-Activating Enzyme (NAE)

NEDD8 is activated through an ATP-dependent reaction via NAE and then is transferred to NEDD8-conjugating enzyme E2. MLN4924 is a selective, effective, first-rate inhibitor of NAE (Gong and Yeh, 1999). This micromolecule inhibits the protein neddylation pathway and is currently under multiple clinical investigations of its anticancer effect against solid tumors and leukemia (Soucy et al., 2009; Godbersen et al., 2014; Swords et al., 2018). The MLN4924 antitumor activity is mediated by its ability to induce cell-associated autophagy, apoptosis and senescence (Milhollen et al., 2010; Han et al., 2016). For example, in liver cancer, MLN4924 induces the DNA damage response (DDR) and apoptosis to inhibit hepatoma cell development in vitro and in vivo and also induces autophagy, whereas MLN4924 induces autophagy mediated by accumulating the mTOR inhibitory protein Deptor and inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated oxidative stress (Peterson et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2012). Identical to its effect in liver cancer, MLN4924 effectively suppresses lymphoma cell growth by inducing cycle arrest of G2 cells and subsequent cell line-dependent apoptosis or senescence. Apoptosis induced by MLN4924 is mediated by the apoptotic signaling pathway, with significantly upregulated pro-apoptotic proteins Bik and Noxa and downregulated anti-apoptotic proteins XIAP, c-IAP1 and c-IAP2, while aging induced by neddylation suppression seemingly depends on the expression of tumor suppressors p21/p27 (Brownell et al., 2010). Mechanistically, when tumor cells are treated with MLN4924, MLN4924 blocks the activities of NAE by binding to its active site to constitute a covalent NEDD8-MLN4924 adduct. Therefore, CRLs are inactivated, leading to the accumulation of tumor-suppressive substrates of CRLs and apoptosis or senescence induction to inhibit cancer cell progression (Karin et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2015).

Consistent with NAE inhibition, MLN4924 treatment of cultured tumor cells results in the inhibition of CRL neddylation and a reciprocal rise in the levels of foregone CRL substrates such as p-IκBα (Soucy et al., 2009). The accumulation of p-IκBα in the cytoplasm inhibits the nuclear translocation of NF-κB transcription factors and suppresses the NF-κB pathway, affecting tumourigenesis and development through transcriptionally controlling genes related to cell growth, angiogenesis, apoptosis, metastasis and cell migration (Karin et al., 2002). For example, in activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (ABC-DLBCL), MLN4924 causes G1-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction by blocking the classic NF-κB pathway. Thus, MLN4924 treatment leads to G1 phase arrest, P-IκBα accumulation and decreased inhibition of NF-κB target genes, significantly affecting MLN4924-mediated antitumor effects (Milhollen et al., 2010).

Autophagy plays a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and is closely associated with the development of many human diseases (Wang and Zhang, 2019). MLN4924 significantly inhibits CRL neddylation modifications and effectively induces autophagy in both dose- and time-dependently in multiple human cancer cell lines (Zhao et al., 2012). MLN4924 inhibits the activity of CRLs, induces the accumulation of its substrate IκBα, blocks the activation of NF-κB and expression of catalase, and promotes the expression of ATF3, thereby inducing autophagy in oesophageal cancer cells (Liang et al., 2020). mTOR is a well-established negative regulator of autophagy (Kim and Guan, 2015). By inactivating CRLs/SCF E3s, MLN4924 can inhibit mTORC1 activity by causing DEPTOR accumulation directly and DEPTOR and HIF1α accumulation via the HIF1-REDD1-TSC1 axis (HIF1α) (Zhao et al., 2012). MLN4924 also triggers autophagy in colon cancer cells by suppressing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Lv et al., 2018). Autophagy may be a novel anti-cancer mechanism for MLN4924 in cancer treatment, providing conceptual evidence for the strategic combination of MLN4924 with autophagy inhibitors to maximize tumor cell killing through enhanced apoptosis.

MLN4924 leads to DNA re-replication, which triggers checkpoint activation, apoptosis, and senescence in cancer cells (Soucy et al., 2009). The replication of genetic material is a critical process of the cell cycle. Re-replication is a known signal that induces DNA damage and causes DNA damage signaling in cells (Zhu et al., 2004; Archambault et al., 2005). Cdt1 is the initiation factor for the induction of DNA re-replication in cells treated with MLN4924 (Lin et al., 2010). Similarly, the DNA damage signaling factors P21 and P53 are important substrates of the NEDD8-mediated neddylation pathway. P21 is crucial in the S-phase of the cell cycle, DNA replication and the cellular senescence pathway (Pérez-Yépez et al., 2018). MLN4924-induced senescence in human colorectal cancer cells relies on recruiting p53 and its downstream adaptor P21 (Lin et al., 2010). For other human tumor-derived cell lines, including HCT116 (colon), Calu-6 (lung), SKOV-3 (ovarian), H460 (lung), DLD-1 (colon), MCF-7 (mammary gland), CWR22 (prostate) and OCI-LY19 (lymphoma), MLN4924 treatment also inhibits proliferation and migration.

Currently, phase I trials for MLN4924 are ongoing in cancers, such as metastatic melanoma (Bhatia et al., 2016), advanced solid tumors (Bhatia et al., 2016), acute myeloid leukemia (Swords et al., 2015), myelodysplastic syndromes (Shah et al., 2016), lymphoma and multiple myeloma (Shah et al., 2016), and these studies have revealed that critical therapeutic effects can be obtained by antagonizing NEDD8-mediated protein degradation (Supplementary Table 1).

Although excellent activity of MLN4924 was observed in early trials, drug resistance was also found in large number of patients. Early preclinical studies have shown that treatment-emergent NAEβ mutations promotes resistance to MLN4924. Additionally, in human leukemic cells, UBA3 mutations increase the enzyme’s affinity for ATP while decreasing its affinity for NEDD8 (Milhollen et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2014); these mutations effectively contribute to decreased MLN4924 potency in vitro. In TCGA, PanCancer Atlas, the frequency of mutations in UBA3 is about 20%, that may suggest that mutations in UBA3 are not the main cause of MLN4924 resistance. Mutations of key molecules are often associated with drug resistance, and in addition to mutations of NAEβ and UBA3, the upregulation of ABCG2 transcription in resistant cells drives clinical resistance (Kathawala et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). Thus, MLN4924 is widely used as an anti-cancer drug in clinical practice but still has some limitations.

NEDD8-Conjugating Enzyme

Activated NEDD8 can be transferred to the subunits of the substrate by the NEDD8-conjugating enzyme E2, which includes two members: UBE2F and UBE2M/Ubc12. RBX proteins can be divided into RBX1 and RBX2 in humans (Nakamura et al., 2000; Brooks and Gu, 2003; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006; Abida et al., 2007). UBE2F pairs with RBX2 to modulate cullin 5 neddylation dependent on E2 RING, while UBE2M functions through RRB1 to mediate the neddylation of cullin 1, 2, 3, 4a, 4b, and 7 (Zhou W. et al., 2017). The E2-RBX-cullin interaction combination determines the in vivo selectivity of neddylation (Huang et al., 2009). The cellular levels of different RBX partners determine the cellular levels of distinct cullins. The two NEDD8 E2s exert different effects in cullin neddylation in vivo (Huang et al., 2009).

Inhibition of E2s, which inhibit one subset of NEDD8 substrates compared with all neddylation substrates, may provide better cytotoxic selectivity than inhibition of E1s, which inactivates the entire neddylation pathway. In lung cancer, targeting UBC12 causes accumulation of the CRL substrates p21, p27, and Wee1, inactivating CRL ubiquitin ligase and arresting the cell cycle in the G2 phase (Li et al., 2019). Therefore, targeting E2s to inhibit neddylation modification blocks the protein neddylation pathway and deactivates CRLs, triggering the aggregation of tumor-suppressive CRL substrates, stopping the cell cycle and impeding tumor growth and metastasis.

NEDD8 E3 Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases based on Cullin are activated by NEDD8 binding to Cullins. Therefore, targeting E2s to inhibit neddylation modification blocks the protein neddylation pathway and deactivates CRLs, triggering the aggregation of tumor-suppressive CRL substrates, stopping the cell cycle and impeding tumor growth and metastasis (Kurz et al., 2008). Human cells express 5 DCN1-like (DCNL) proteins, termed DCNL1–DCNL5 (also named DCUN1D1–5), each encompassing a C-terminal potentiating neddylation domain and an N-terminal ubiquitin-binding (UBA) domain, which we termed the PONY domain, with distinct amino-terminal extensions (Kurz et al., 2005; Kurz et al., 2008; Meyer-Schaller et al., 2009). For example, in various human tumors, activation of squamous cell carcinoma-associated oncogene (SCCRO) triggers its function as an oncogene, and the UBA domain in SCCRO (also called DCUN1D1) works as a feedback regulator of biochemical and oncogenic activity (Huang et al., 2015). Conversely, DCNL3 levels are downregulated in the liver, bladder, and renal tumors (Ma et al., 2008) compared with those in normal controls, indicating that DCNL regulation is critical for human cancer development. Considering the conserved binding characteristics of the UBA domain, targeting these vital proteins could possess therapeutic implications for human cancer treatment.

Targeting Protein Neddylation-Based Combination Therapies

NAE Inhibitor MLN4924 Combined With Chemotherapy Drugs

The effectiveness of radiotherapy for cancer is limited by some of the toxic side effects of dose increases, although existing radiotherapy remains the preferred problem for local cancer control (Lyons et al., 2011; Venur and Leone, 2016). Chemotherapy can improve the efficiency of ionizing radiation by inhibiting DNA repair and overcoming apoptotic resistance (Bandugula and N, 2013). Among anticancer drugs, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) is the most effective inhibitor of glycolysis, glucose metabolism and ATP production (Dwarakanath, 2009). 2-DG increases the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs (such as doxorubicin [DOX] and paclitaxel) in human osteosarcoma and non-small cell lung cancer in vivo (Kern and Norton, 1987). 2-DG + DOX and buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) dramatically promotes cytotoxicity by regulating oxidative stress and interfering with thioethanol metabolism in breast cancer cells (Tagg et al., 2008). MLN4924 can sensitize drug-resistant pancreatic, lung and breast cancer cells to ionizing radiation, although it has little effect on normal lung fibroblasts, indicating that MLN4924 is a new radiation sensitizer (Wei et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Sun and Li, 2013). Therefore, 2-DG plus MLN4924 could be an anti-proliferative and radiation-sensitizing strategy for various human cancers, providing insights on breast cancer treatment (Oladghaffari et al., 2017).

NAE Inhibitor MLN4924 Combined With Targeted Drugs

Endocrine therapy is the standard treatment for oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer and can significantly reduce the risk of disease recurrence and mortality (Anbalagan and Rowan, 2015). However, nearly one-third of patients still experience disease recurrence and metastasis mediated by endocrine resistance at the beginning of treatment or during treatment (deConinck et al., 1995; Anbalagan and Rowan, 2015). Fulvestrant has been approved as a selective oestrogen receptor downregulator (SERD) to cure locally advanced or metastatic breast carcinoma and significantly extends the progression-free survival of patients (Johnston and Cheung, 2010). The neddylation modification pathway is activated in breast carcinoma and is associated with ER-α expression. In anti-breast cancer treatment, the neddylation pathway can downregulate ER-α expression and inhibit ER inactivation, which can have a synergistic anticancer effect with fulvestrant (Jia et al., 2019).

Inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) are anti-apoptotic regulators that prevent apoptosis and are often overexpressed in many human tumors, in which they promote apoptosis evasion and cell survival (Gyrd-Hansen and Meier, 2010). IAP antagonists, also regarded as second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (SMAC) mimetics, have been recognized as new apoptosis-inducing agents for treatment, either alone or in combination with other antitumor drugs (Dineen et al., 2010; Sumi et al., 2013). MLN4924 activates stress-response signaling and works synergistically with IAP antagonists and DNA damage-inducing chemotherapies. The oral IAP antagonist T-3256336 synergistically promotes the anti-proliferative results of the NAE inhibitor MLN4924 in cancer cells (Sumi et al., 2016). The combination of IAP antagonists with MLN4924 inhibits tumor proliferation, demonstrating the promise of a novel cancer combination treatment.

NAE Inhibitor MLN4924 Combined With Drugs Targeting the Antitumor Immune Axis

Because the FDA approved the anti-PD-1 (programmed death-1) antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab, as well as the anti-PD-L1 antibodies atezolimuab, durvalumab and avelumab, the signaling pathway involving PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 has become a research hotspot in the field of tumor immunology and oncology (Dong et al., 2002). However, not all tumors are sensitive to these compounds. Inhibitors of neddylation are potential cancer treatment and may promote cancer-related immunosuppression. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that some traditional and targeted cancer therapies modulate antitumor immunity (Galluzzi et al., 2015; Patel and Minn, 2018), suggesting that cytotoxic anticancer drugs combined with immune checkpoint blockade therapy may be an effective combination. Thus, the combination of MLN4924 and anti-PD-L1 therapy might significantly increase the therapeutic efficacy in vivo compared with that with either agent alone.

Conclusion

MLN4924/pevonedistat/TAK-924, as a micromolecule inhibitor, inhibits NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE), which impedes the ubiquitination modification cascade, inactivating CRLs. MLN4924 is the critical element of the dynamic protein homeostasis pathway. Many clinical studies have shown the impressive antitumor activity of MLN4924, but single-drug treatment has some limitations. Clinical trials have demonstrated that MLN4924 alone or combined with chemotherapy has a good treatment effect. MLN4924 is currently under phase II/III clinical trials for antitumor treatment and shows good safety and tolerability, indicating its good development prospects. We summarize the previous and recent findings in Supplementary Table 1.

Recent studies have shown that MLN4924 has good anti-ubiquitination activity and several activities independent of its ubiquitination effects. MLN4924 induces EGFR dimerization, thus triggering AKT1 activation. However, AKT1 and EGFR inhibitors can eliminate MLN4924’s inhibition of cilia formation (Mao et al., 2019). These results suggest that MLN4924 may have new applications in human cancer therapy that exhibit cilia-dependent increase or drug resistance (Zhou et al., 2016). MLN4924 can also promote glycolysis, and MLN4924 significantly increases the activity of pyruvate kinase (PK), which could improve the survival rate of breast carcinoma cells. Therefore, PKM2 activation, which promotes glycolysis and cell survival, is an adverse outcome of MLN4924 for cancer treatment and careful monitoring is required when using this drug (Zhou Q. et al., 2019). The dosage of MLN4924 is also worthy of our attention. Studies on various signal inhibitors have shown that the tumor sphere stimulation of MLN4924 is primarily regulated by the RAS/MAPK pathway. In mouse skin, MLN4924 accelerates EGF-induced injury recovery. Therefore, a low dose of MLN4924 controls the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells and has different anticancer properties than the high dose. Additionally, MLN4924 has promising application in stem cell treatment and tissue regeneration. In addition to the dosage of MLN4924 that requires caution, the drug resistance of MLN4924 also deserves our attention. In TCGA, PanCancer Atlas, the frequency of mutations in UBA3 in all tumors is approximately 20%, which may suggest that there are other reasons for MLN4924 resistance and that no key gene mutations but the upregulation of ABCG2 transcripts were found in relapsed/refractory patients with MLN4924. Therefore, we can use this hint to look for other causes of drug resistance in MLN4924, and that bring new understanding to the resistance of MLN4924 to better overcome it. To overcome resistance to MLN4924, refining the drug combination may be a more routine and convenient clinical tool, in contrast to the development of a new generation of NAE inhibitors. In parallel, mutant molecules or ABCG2 can be used as clinical biomarkers to predict therapeutic resistance to MLN4924.

Immunotherapy has become a hot topic in cancer precision medicine and has gradually developed into the fourth tumor treatment mode after surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, it is not universally effective, and even the most popular PD-1/PDL-1 therapy only leads to a good response in approximately 20% of patients. The body’s immune system has the function of immune surveillance. When malignant cells appear in the body, the immune system recognizes and specifically clears these “non-self” cells. However, tumor cells can still grow in the body, suggesting that they can either evade attack by the host immune system or somehow modulate the body’s effective antitumor immune response. The inhibition of cell activation caused by tumor cell modification is an important mechanism of tumor immune escape. According to recent research progress, targeted therapy is expected to inhibit tumor immune escape, improve the therapeutic effect of tumor treatment and improve the prognosis of patients.

Author Contributions

LZ, HJ, and CL contributed to the conception of the review. WG wrote the manuscript. ZP helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771110), Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2019ZD31), Taishan Scholars Construction Project, and Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.653882/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Combined application and clinical staging of MLN4924.

References

Abida, W. M., Nikolaev, A., Zhao, W., Zhang, W., and Gu, W. (2007). FBXO11 promotes the Neddylation of p53 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1797–1804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609001200

Anbalagan, M., and Rowan, B. G. (2015). Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 418(Pt 3), 264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.016

Archambault, V., Ikui, A. E., Drapkin, B. J., and Cross, F. R. (2005). Disruption of mechanisms that prevent rereplication triggers a DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6707–6721. doi: 10.1128/mcb.25.15.6707-6721.2005

Bandugula, V. R., and N, R. P. (2013). 2-Deoxy-D-glucose and ferulic acid modulates radiation response signaling in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 34, 251–259. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0545-6

Barbier-Torres, L., Delgado, T. C., García-Rodríguez, J. L., Zubiete-Franco, I., Fernández-Ramos, D., Buqué, X., et al. (2015). Stabilization of LKB1 and Akt by neddylation regulates energy metabolism in liver cancer. Oncotarget 6, 2509–2523. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3191

Berndsen, C. E., and Wolberger, C. (2014). New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 301–307. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2780

Bhatia, S., Pavlick, A. C., Boasberg, P., Thompson, J. A., Mulligan, G., Pickard, M. D., et al. (2016). A phase I study of the investigational NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor pevonedistat (TAK-924/MLN4924) in patients with metastatic melanoma. Invest. New Drugs 34, 439–449. doi: 10.1007/s10637-016-0348-5

Bohnsack, R. N., and Haas, A. L. (2003). Conservation in the mechanism of Nedd8 activation by the human AppBp1-Uba3 heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26823–26830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303177200

Broemer, M., Tenev, T., Rigbolt, K. T., Hempel, S., Blagoev, B., Silke, J., et al. (2010). Systematic in vivo RNAi analysis identifies IAPs as NEDD8-E3 ligases. Mol. Cell 40, 810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.011

Brooks, C. L., and Gu, W. (2003). Ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation: the molecular basis for p53 regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 164–171. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00003-6

Brownell, J. E., Sintchak, M. D., Gavin, J. M., Liao, H., Bruzzese, F. J., Bump, N. J., et al. (2010). Substrate-assisted inhibition of ubiquitin-like protein-activating enzymes: the NEDD8 E1 inhibitor MLN4924 forms a NEDD8-AMP mimetic in situ. Mol. Cell 37, 102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.024

Chairatvit, K., and Ngamkitidechakul, C. (2007). Control of cell proliferation via elevated NEDD8 conjugation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 306, 163–169. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9566-7

Chen, P., Hu, T., Liang, Y., Li, P., Chen, X., Zhang, J., et al. (2016). Neddylation inhibition activates the extrinsic apoptosis pathway through ATF4-CHOP-DR5 axis in human esophageal cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 4145–4157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-2254

Czuczman, N. M., Barth, M. J., Gu, J., Neppalli, V., Mavis, C., Frys, S. E., et al. (2016). Pevonedistat, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, is active in mantle cell lymphoma and enhances rituximab activity in vivo. Blood 127, 1128–1137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-640920

deConinck, E. C., McPherson, L. A., and Weigel, R. J. (1995). Transcriptional regulation of estrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2191–2196. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2191

Dengler, M. A., Weilbacher, A., Gutekunst, M., Staiger, A. M., Vöhringer, M. C., Horn, H., et al. (2014). Discrepant NOXA (PMAIP1) transcript and NOXA protein levels: a potential Achilles’ heel in mantle cell lymphoma. Cell Death Dis. 5:e1013. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.552

Deshaies, R. J. (1999). SCF and cullin/ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435

Deshaies, R. J., and Joazeiro, C. A. (2009). RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809

Dil Kuazi, A., Kito, K., Abe, Y., Shin, R. W., Kamitani, T., and Ueda, N. (2003). NEDD8 protein is involved in ubiquitinated inclusion bodies. J. Pathol. 199, 259–266. doi: 10.1002/path.1283

Dineen, S. P., Roland, C. L., Greer, R., Carbon, J. G., Toombs, J. E., Gupta, P., et al. (2010). Smac mimetic increases chemotherapy response and improves survival in mice with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 2852–2861. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-3892

Dong, H., Strome, S. E., Salomao, D. R., Tamura, H., Hirano, F., Flies, D. B., et al. (2002). Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 8, 793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730

Duan, H., Wang, Y., Aviram, M., Swaroop, M., Loo, J. A., Bian, J., et al. (1999). SAG, a novel zinc RING finger protein that protects cells from apoptosis induced by redox agents. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 3145–3155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3145

Duda, D. M., Borg, L. A., Scott, D. C., Hunt, H. W., Hammel, M., and Schulman, B. A. (2008). Structural insights into NEDD8 activation of cullin-RING ligases: conformational control of conjugation. Cell 134, 995–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.022

Dwarakanath, B. S. (2009). Cytotoxicity, radiosensitization, and chemosensitization of tumor cells by 2-deoxy-D-glucose in vitro. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 5(Suppl. 1), S27–S31. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.55137

Embade, N., Fernández-Ramos, D., Varela-Rey, M., Beraza, N., Sini, M., Gutiérrez de Juan, V., et al. (2012). Murine double minute 2 regulates Hu antigen R stability in human liver and colon cancer through NEDDylation. Hepatology 55, 1237–1248. doi: 10.1002/hep.24795

Enchev, R. I., Schulman, B. A., and Peter, M. (2015). Protein neddylation: beyond cullin-RING ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 30–44. doi: 10.1038/nrm3919

Feldman, R. M., Correll, C. C., Kaplan, K. B., and Deshaies, R. J. (1997). A complex of Cdc4p, Skp1p, and Cdc53p/cullin catalyzes ubiquitination of the phosphorylated CDK inhibitor Sic1p. Cell 91, 221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80404-3

Galluzzi, L., Buqué, A., Kepp, O., Zitvogel, L., and Kroemer, G. (2015). Immunological effects of conventional chemotherapy and targeted anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 28, 690–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.012

Gan-Erdene, T., Nagamalleswari, K., Yin, L., Wu, K., Pan, Z. Q., and Wilkinson, K. D. (2003). Identification and characterization of DEN1, a deneddylase of the ULP family. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28892–28900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302890200

Gao, F., Cheng, J., Shi, T., and Yeh, E. T. (2006). Neddylation of a breast cancer-associated protein recruits a class III histone deacetylase that represses NFkappaB-dependent transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1171–1177. doi: 10.1038/ncb1483

Gao, Q., Yu, G. Y., Shi, J. Y., Li, L. H., Zhang, W. J., Wang, Z. C., et al. (2014). Neddylation pathway is up-regulated in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and serves as a potential therapeutic target. Oncotarget 5, 7820–7832. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2309

Godbersen, J. C., Humphries, L. A., Danilova, O. V., Kebbekus, P. E., Brown, J. R., Eastman, A., et al. (2014). The Nedd8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 thwarts microenvironment-driven NF-κB activation and induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 1576–1589. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-0987

Gong, L., and Yeh, E. T. (1999). Identification of the activating and conjugating enzymes of the NEDD8 conjugation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12036–12042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12036

Gyrd-Hansen, M., and Meier, P. (2010). IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-kappaB, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 561–574. doi: 10.1038/nrc2889

Hammill, J. T., Bhasin, D., Scott, D. C., Min, J., Chen, Y., Lu, Y., et al. (2018). Discovery of an orally bioavailable inhibitor of defective in cullin neddylation 1 (DCN1)-mediated cullin neddylation. J. Med. Chem. 61, 2694–2706. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01282

Han, K., Wang, Q., Cao, H., Qiu, G., Cao, J., Li, X., et al. (2016). The NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 induces G2 arrest and apoptosis in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget 7, 23812–23824. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8068

Hua, W., Li, C., Yang, Z., Li, L., Jiang, Y., Yu, G., et al. (2015). Suppression of glioblastoma by targeting the overactivated protein neddylation pathway. Neuro Oncol. 17, 1333–1343. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov066

Huang, D. T., Ayrault, O., Hunt, H. W., Taherbhoy, A. M., Duda, D. M., Scott, D. C., et al. (2009). E2-RING expansion of the NEDD8 cascade confers specificity to cullin modification. Mol. Cell 33, 483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.011

Huang, D. T., Paydar, A., Zhuang, M., Waddell, M. B., Holton, J. M., and Schulman, B. A. (2005). Structural basis for recruitment of Ubc12 by an E2 binding domain in NEDD8’s E1. Mol. Cell 17, 341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.020

Huang, G., Towe, C. W., Choi, L., Yonekawa, Y., Bommeljé, C. C., Bains, S., et al. (2015). The ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain of SCCRO/DCUN1D1 protein serves as a feedback regulator of biochemical and oncogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 296–309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560169

Jia, L., Li, H., and Sun, Y. (2011). Induction of p21-dependent senescence by an NAE inhibitor, MLN4924, as a mechanism of growth suppression. Neoplasia 13, 561–569. doi: 10.1593/neo.11420

Jia, X., Li, C., Li, L., Liu, X., Zhou, L., Zhang, W., et al. (2019). Neddylation inactivation facilitates FOXO3a nuclear export to suppress estrogen receptor transcription and improve fulvestrant sensitivity. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3658–3672. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-2434

Jiang, Y., and Jia, L. (2015). Neddylation pathway as a novel anti-cancer target: mechanistic investigation and therapeutic implication. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 15, 1127–1133. doi: 10.2174/1871520615666150305111257

Johnston, S. C., Larsen, C. N., Cook, W. J., Wilkinson, K. D., and Hill, C. P. (1997). Crystal structure of a deubiquitinating enzyme (human UCH-L3) at 1.8 A resolution. EMBO J. 16, 3787–3796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3787

Johnston, S. J., and Cheung, K. L. (2010). Fulvestrant – a novel endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 902–914. doi: 10.2174/092986710790820633

Kamitani, T., Kito, K., Nguyen, H. P., and Yeh, E. T. (1997). Characterization of NEDD8, a developmentally down-regulated ubiquitin-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28557–28562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28557

Kamura, T., Conrad, M. N., Yan, Q., Conaway, R. C., and Conaway, J. W. (1999). The Rbx1 subunit of SCF and VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase activates Rub1 modification of cullins Cdc53 and Cul2. Genes Dev. 13, 2928–2933. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2928

Karin, M., Cao, Y., Greten, F. R., and Li, Z. W. (2002). NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780

Kathawala, R. J., Espitia, C. M., Jones, T. M., Islam, S., Gupta, P., Zhang, Y. K., et al. (2020). ABCG2 overexpression contributes to pevonedistat resistance. Cancers 12:429. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020429

Kern, K. A., and Norton, J. A. (1987). Inhibition of established rat fibrosarcoma growth by the glucose antagonist 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Surgery 102, 380–385.

Kim, Y. C., and Guan, K. L. (2015). mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 25–32. doi: 10.1172/jci73939

Knorr, K. L., Schneider, P. A., Meng, X. W., Dai, H., Smith, B. D., Hess, A. D., et al. (2015). MLN4924 induces Noxa upregulation in acute myelogenous leukemia and synergizes with Bcl-2 inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 22, 2133–2142. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.74

Kumar, S., Tomooka, Y., and Noda, M. (1992). Identification of a set of genes with developmentally down-regulated expression in the mouse brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 185, 1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91747-e

Kumar, S., Yoshida, Y., and Noda, M. (1993). Cloning of a cDNA which encodes a novel ubiquitin-like protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 195, 393–399. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2056

Kurz, T., Chou, Y. C., Willems, A. R., Meyer-Schaller, N., Hecht, M. L., Tyers, M., et al. (2008). Dcn1 functions as a scaffold-type E3 ligase for cullin neddylation. Mol. Cell 29, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.012

Kurz, T., Ozlü, N., Rudolf, F., O’Rourke, S. M., Luke, B., Hofmann, K., et al. (2005). The conserved protein DCN-1/Dcn1p is required for cullin neddylation in C. elegans and S. cerevisiae. Nature 435, 1257–1261. doi: 10.1038/nature03662

Lan, H., Tang, Z., Jin, H., and Sun, Y. (2016). Neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 suppresses growth and migration of human gastric cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 6:24218. doi: 10.1038/srep24218

Leclerc, G. M., Zheng, S., Leclerc, G. J., DeSalvo, J., Swords, R. T., and Barredo, J. C. (2016). The NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor pevonedistat activates the eIF2α and mTOR pathways inducing UPR-mediated cell death in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 50, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.09.007

Lee, M. R., Lee, D., Shin, S. K., Kim, Y. H., and Choi, C. Y. (2008). Inhibition of APP intracellular domain (AICD) transcriptional activity via covalent conjugation with Nedd8. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366, 976–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.066

Li, H., Zhu, H., Liu, Y., He, F., Xie, P., and Zhang, L. (2016). Itch promotes the neddylation of JunB and regulates JunB-dependent transcription. Cell. Signal. 28, 1186–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.05.016

Li, L., Kang, J., Zhang, W., Cai, L., Wang, S., Liang, Y., et al. (2019). Validation of NEDD8-conjugating enzyme UBC12 as a new therapeutic target in lung cancer. EBioMedicine 45, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.005

Li, L., Wang, M., Yu, G., Chen, P., Li, H., Wei, D., et al. (2014). Overactivated neddylation pathway as a therapeutic target in lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106:dju083. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju083

Liang, Y., Jiang, Y., Jin, X., Chen, P., Heng, Y., Cai, L., et al. (2020). Neddylation inhibition activates the protective autophagy through NF-κB-catalase-ATF3 Axis in human esophageal cancer cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 18:72. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00576-z

Lin, J. J., Milhollen, M. A., Smith, P. G., Narayanan, U., and Dutta, A. (2010). NEDD8-targeting drug MLN4924 elicits DNA rereplication by stabilizing Cdt1 in S phase, triggering checkpoint activation, apoptosis, and senescence in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 70, 10310–10320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-2062

Loftus, S. J., Liu, G., Carr, S. M., Munro, S., and La Thangue, N. B. (2012). NEDDylation regulates E2F-1-dependent transcription. EMBO Rep. 13, 811–818. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.113

Lohrum, M. A., Ludwig, R. L., Kubbutat, M. H., Hanlon, M., and Vousden, K. H. (2003). Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell 3, 577–587. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00134-x

Luo, Z., Yu, G., Lee, H. W., Li, L., Wang, L., Yang, D., et al. (2012). The Nedd8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 induces autophagy and apoptosis to suppress liver cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 72, 3360–3371. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-12-0388

Lv, Y., Li, B., Han, K., Xiao, Y., Yu, X., Ma, Y., et al. (2018). The Nedd8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 suppresses colon cancer cell growth via triggering autophagy. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 22, 617–625. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.6.617

Lyons, J. A., Woods, C., Galanopoulos, N., and Silverman, P. (2011). Emerging radiation techniques for early-stage breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery. Future Oncol. 7, 915–925. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.61

Ma, T., Chen, Y., Zhang, F., Yang, C. Y., Wang, S., and Yu, X. (2013). RNF111-dependent neddylation activates DNA damage-induced ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 49, 897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.006

Ma, T., Shi, T., Huang, J., Wu, L., Hu, F., He, P., et al. (2008). DCUN1D3, a novel UVC-responsive gene that is involved in cell cycle progression and cell growth. Cancer Sci. 99, 2128–2135. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00929.x

Mao, H., Tang, Z., Li, H., Sun, B., Tan, M., Fan, S., et al. (2019). Neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 suppresses cilia formation by modulating AKT1. Protein Cell 10, 726–744. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-0614-3

Mendoza, H. M., Shen, L. N., Botting, C., Lewis, A., Chen, J., Ink, B., et al. (2003). NEDP1, a highly conserved cysteine protease that deNEDDylates cullins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25637–25643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212948200

Merlet, J., Burger, J., Gomes, J. E., and Pintard, L. (2009). Regulation of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin-ligases by neddylation and dimerization. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1924–1938. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8712-7

Metzger, M. B., Pruneda, J. N., Klevit, R. E., and Weissman, A. M. (2014). RING-type E3 ligases: master manipulators of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and ubiquitination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.026

Meyer-Schaller, N., Chou, Y. C., Sumara, I., Martin, D. D., Kurz, T., Katheder, N., et al. (2009). The human Dcn1-like protein DCNL3 promotes Cul3 neddylation at membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12365–12370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812528106

Milhollen, M. A., Thomas, M. P., Narayanan, U., Traore, T., Riceberg, J., Amidon, B. S., et al. (2012). Treatment-emergent mutations in NAEβ confer resistance to the NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924. Cancer Cell 21, 388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.009

Milhollen, M. A., Traore, T., Adams-Duffy, J., Thomas, M. P., Berger, A. J., Dang, L., et al. (2010). MLN4924, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, is active in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma models: rationale for treatment of NF-{kappa}B-dependent lymphoma. Blood 116, 1515–1523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272567

Mori, F., Nishie, M., Piao, Y. S., Kito, K., Kamitani, T., Takahashi, H., et al. (2005). Accumulation of NEDD8 in neuronal and glial inclusions of neurodegenerative disorders. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 31, 53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00603.x

Nakamura, S., Roth, J. A., and Mukhopadhyay, T. (2000). Multiple lysine mutations in the C-terminal domain of p53 interfere with MDM2-dependent protein degradation and ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 9391–9398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9391-9398.2000

Nakayama, K. I., and Nakayama, K. (2006). Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrc1881

Noguchi, K., Okumura, F., Takahashi, N., Kataoka, A., Kamiyama, T., Todo, S., et al. (2011). TRIM40 promotes neddylation of IKKγ and is downregulated in gastrointestinal cancers. Carcinogenesis 32, 995–1004. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr068

Oladghaffari, M., Shabestani Monfared, A., Farajollahi, A., Baradaran, B., Mohammadi, M., Shanehbandi, D., et al. (2017). MLN4924 and 2DG combined treatment enhances the efficiency of radiotherapy in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 93, 590–599. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2017.1294272

Oved, S., Mosesson, Y., Zwang, Y., Santonico, E., Shtiegman, K., Marmor, M. D., et al. (2006). Conjugation to Nedd8 instigates ubiquitylation and down-regulation of activated receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21640–21651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513034200

Paiva, C., Godbersen, J. C., Berger, A., Brown, J. R., and Danilov, A. V. (2015). Targeting neddylation induces DNA damage and checkpoint activation and sensitizes chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells to alkylating agents. Cell Death Dis. 6:e1807. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.161

Patel, S. A., and Minn, A. J. (2018). Combination cancer therapy with immune checkpoint blockade: mechanisms and strategies. Immunity 48, 417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.007

Pérez-Yépez, E. A., Saldívar-Cerón, H. I., Villamar-Cruz, O., Pérez-Plasencia, C., and Arias-Romero, L. E. (2018). p21 Activated kinase 1: nuclear activity and its role during DNA damage repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 65, 42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.03.004

Peterson, T. R., Laplante, M., Thoreen, C. C., Sancak, Y., Kang, S. A., Kuehl, W. M., et al. (2009). DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell 137, 873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.046

Petroski, M. D., and Deshaies, R. J. (2005). Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547

Qiu, X., Wei, R., Li, Y., Zhu, Q., Xiong, C., Chen, Y., et al. (2016). NEDL2 regulates enteric nervous system and kidney development in its Nedd8 ligase activity-dependent manner. Oncotarget 7, 31440–31453. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8951

Rabut, G., and Peter, M. (2008). Function and regulation of protein neddylation. ‘Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 9, 969–976. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.183

Rabut, G., Le Dez, G., Verma, R., Makhnevych, T., Knebel, A., Kurz, T., et al. (2011). The TFIIH subunit Tfb3 regulates cullin neddylation. Mol. Cell 43, 488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.032

Ryu, J. H., Li, S. H., Park, H. S., Park, J. W., Lee, B., and Chun, Y. S. (2011). Hypoxia-inducible factor α subunit stabilization by NEDD8 conjugation is reactive oxygen species-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6963–6970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188706

Saha, A., and Deshaies, R. J. (2008). Multimodal activation of the ubiquitin ligase SCF by Nedd8 conjugation. Mol. Cell 32, 21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.021

Sakata, E., Yamaguchi, Y., Miyauchi, Y., Iwai, K., Chiba, T., Saeki, Y., et al. (2007). Direct interactions between NEDD8 and ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes upregulate cullin-based E3 ligase activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 167–168. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1191

Salon, C., Brambilla, E., Brambilla, C., Lantuejoul, S., Gazzeri, S., and Eymin, B. (2007). Altered pattern of Cul-1 protein expression and neddylation in human lung tumours: relationships with CAND1 and cyclin E protein levels. J. Pathol. 213, 303–310. doi: 10.1002/path.2223

Seol, J. H., Feldman, R. M., Zachariae, W., Shevchenko, A., Correll, C. C., Lyapina, S., et al. (1999). Cdc53/cullin and the essential Hrt1 RING-H2 subunit of SCF define a ubiquitin ligase module that activates the E2 enzyme Cdc34. Genes Dev. 13, 1614–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1614

Shah, J. J., Jakubowiak, A. J., O’Connor, O. A., Orlowski, R. Z., Harvey, R. D., Smith, M. R., et al. (2016). Phase I study of the novel investigational NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor pevonedistat (MLN4924) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma or lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 34–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-1237

Shu, J., Liu, C., Wei, R., Xie, P., He, S., and Zhang, L. (2016). Nedd8 targets ubiquitin ligase Smurf2 for neddylation and promote its degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 474, 51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.058

Soucy, T. A., Smith, P. G., Milhollen, M. A., Berger, A. J., Gavin, J. M., Adhikari, S., et al. (2009). An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature 458, 732–736. doi: 10.1038/nature07884

Stickle, N. H., Chung, J., Klco, J. M., Hill, R. P., Kaelin, W. G. Jr., and Ohh, M. (2004). pVHL modification by NEDD8 is required for fibronectin matrix assembly and suppression of tumor development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3251–3261. doi: 10.1128/mcb.24.8.3251-3261.2004

Sumi, H., Inazuka, M., Morimoto, M., Hibino, R., Hashimoto, K., Ishikawa, T., et al. (2016). An inhibitor of apoptosis protein antagonist T-3256336 potentiates the antitumor efficacy of the Nedd8-activating enzyme inhibitor pevonedistat (TAK-924/MLN4924). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 480, 380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.058

Sumi, H., Yabuki, M., Iwai, K., Morimoto, M., Hibino, R., Inazuka, M., et al. (2013). Antitumor activity and pharmacodynamic biomarkers of a novel and orally available small-molecule antagonist of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 230–240. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-12-0699

Sun, Y., and Li, H. (2013). Functional characterization of SAG/RBX2/ROC2/RNF7, an antioxidant protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Protein Cell 4, 103–116. doi: 10.1007/s13238-012-2105-7

Swords, R. T., Coutre, S., Maris, M. B., Zeidner, J. F., Foran, J. M., Cruz, J., et al. (2018). Pevonedistat, a first-in-class NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, combined with azacitidine in patients with AML. Blood 131, 1415–1424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-805895

Swords, R. T., Erba, H. P., DeAngelo, D. J., Bixby, D. L., Altman, J. K., Maris, M., et al. (2015). Pevonedistat (MLN4924), a first-in-class NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 1 study. Br. J. Haematol. 169, 534–543. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13323

Swords, R. T., Kelly, K. R., Smith, P. G., Garnsey, J. J., Mahalingam, D., Medina, E., et al. (2010). Inhibition of NEDD8-activating enzyme: a novel approach for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 115, 3796–3800. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254862

Tagg, S. L., Foster, P. A., Leese, M. P., Potter, B. V., Reed, M. J., Purohit, A., et al. (2008). 2-Methoxyoestradiol-3,17-O,O-bis-sulphamate and 2-deoxy-D-glucose in combination: a potential treatment for breast and prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 99, 1842–1848. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604752

Tong, S., Si, Y., Yu, H., Zhang, L., Xie, P., and Jiang, W. (2017). MLN4924 (Pevonedistat), a protein neddylation inhibitor, suppresses proliferation and migration of human clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7:5599. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06098-y

Venur, V. A., and Leone, J. P. (2016). Targeted therapies for brain metastases from breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:1543. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091543

Vogl, A. M., Phu, L., Becerra, R., Giusti, S. A., Verschueren, E., Hinkle, T. B., et al. (2020). Global site-specific neddylation profiling reveals that NEDDylated cofilin regulates actin dynamics. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 210–220. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0370-3

Walden, H., Podgorski, M. S., Huang, D. T., Miller, D. W., Howard, R. J., and Minor, D. L. Jr. et al. (2003). The structure of the APPBP1-UBA3-NEDD8-ATP complex reveals the basis for selective ubiquitin-like protein activation by an E1. Mol. Cell 12, 1427–1437. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00452-0

Wang, J., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Wang, X., Liu, X., Liu, L., et al. (2017). Targeting neddylation pathway with MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) induces NOXA-dependent apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 490, 1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.179

Wang, S., Zhao, L., Shi, X. J., Ding, L., Yang, L., Wang, Z. Z., et al. (2019). Development of highly potent, selective, and cellular active Triazolo[1,5- a]pyrimidine-based inhibitors targeting the DCN1-UBC12 protein-protein interaction. J. Med. Chem. 62, 2772–2797. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00113

Wang, Y., and Zhang, H. (2019). Regulation of autophagy by mTOR signaling pathway. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1206, 67–83. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0602-4_3

Wang, Y., Luo, Z., Pan, Y., Wang, W., Zhou, X., Jeong, L. S., et al. (2015). Targeting protein neddylation with an NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 induced apoptosis or senescence in human lymphoma cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 420–429. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2014.1003003

Watson, I. R., Irwin, M. S., and Ohh, M. (2011). NEDD8 pathways in cancer, Sine Quibus Non. Cancer Cell 19, 168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.002

Wei, D., Li, H., Yu, J., Sebolt, J. T., Zhao, L., Lawrence, T. S., et al. (2012). Radiosensitization of human pancreatic cancer cells by MLN4924, an investigational NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor. Cancer Res. 72, 282–293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-11-2866

Wei, L. Y., Wu, Z. X., Yang, Y., Zhao, M., Ma, X. Y., Li, J. S., et al. (2020). Overexpression of ABCG2 confers resistance to pevonedistat, an NAE inhibitor. Exp. Cell Res. 388:111858. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.111858

Xie, P., Peng, Z., Chen, Y., Li, H., Du, M., Tan, Y., et al. (2020). Neddylation of PTEN regulates its nuclear import and promotes tumor development. Cell Res. 31, 291–311. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00443-z

Xie, P., Yang, J. P., Cao, Y., Peng, L. X., Zheng, L. S., Sun, R., et al. (2017). Promoting tumorigenesis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, NEDD8 serves as a potential theranostic target. Cell Death Dis. 8:e2834. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.195

Xie, P., Zhang, M., He, S., Lu, K., Chen, Y., Xing, G., et al. (2014). The covalent modifier Nedd8 is critical for the activation of Smurf1 ubiquitin ligase in tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 5:3733. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4733

Xirodimas, D. P. (2008). Novel substrates and functions for the ubiquitin-like molecule NEDD8. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 802–806. doi: 10.1042/bst0360802

Xirodimas, D. P., Saville, M. K., Bourdon, J. C., Hay, R. T., and Lane, D. P. (2004). Mdm2-mediated NEDD8 conjugation of p53 inhibits its transcriptional activity. Cell 118, 83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.016

Xirodimas, D. P., Sundqvist, A., Nakamura, A., Shen, L., Botting, C., and Hay, R. T. (2008). Ribosomal proteins are targets for the NEDD8 pathway. EMBO Rep. 9, 280–286. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.10

Xu, G. W., Toth, J. I., da Silva, S. R., Paiva, S. L., Lukkarila, J. L., Hurren, R., et al. (2014). Mutations in UBA3 confer resistance to the NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 in human leukemic cells. PLoS One 9:e93530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093530

Yang, D., Tan, M., Wang, G., and Sun, Y. (2012). The p21-dependent radiosensitization of human breast cancer cells by MLN4924, an investigational inhibitor of NEDD8 activating enzyme. PLoS One 7:e34079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034079

Yao, W. T., Wu, J. F., Yu, G. Y., Wang, R., Wang, K., Li, L. H., et al. (2014). Suppression of tumor angiogenesis by targeting the protein neddylation pathway. Cell Death Dis. 5:e1059. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.21

Zhang, Y., Shi, C. C., Zhang, H. P., Li, G. Q., and Li, S. S. (2016). MLN4924 suppresses neddylation and induces cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis in human osteosarcoma. Oncotarget 7, 45263–45274. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9481

Zhang, Y., Wolf, G. W., Bhat, K., Jin, A., Allio, T., Burkhart, W. A., et al. (2003). Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8902–8912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.23.23.8902-8912.2003

Zhao, Y., Morgan, M. A., and Sun, Y. (2014). Targeting neddylation pathways to inactivate cullin-RING ligases for anticancer therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 2383–2400. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5795

Zhao, Y., Xiong, X., Jia, L., and Sun, Y. (2012). Targeting cullin-RING ligases by MLN4924 induces autophagy via modulating the HIF1-REDD1-TSC1-mTORC1-DEPTOR axis. Cell Death Dis. 3:e386. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.125

Zheng, N., and Shabek, N. (2017). Ubiquitin ligases: structure, function, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 129–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014922

Zheng, N., Schulman, B. A., Song, L., Miller, J. J., Jeffrey, P. D., Wang, P., et al. (2002). Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416, 703–709. doi: 10.1038/416703a

Zhou, H., Lu, J., Liu, L., Bernard, D., Yang, C. Y., Fernandez-Salas, E., et al. (2017). A potent small-molecule inhibitor of the DCN1-UBC12 interaction that selectively blocks cullin 3 neddylation. Nat. Commun. 8:1150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01243-7

Zhou, L., Jiang, Y., Luo, Q., Li, L., and Jia, L. (2019). Neddylation: a novel modulator of the tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 18:77. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0979-1

Zhou, L., Zhang, W., Sun, Y., and Jia, L. (2018). Protein neddylation and its alterations in human cancers for targeted therapy. Cell. Signal. 44, 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.009

Zhou, Q., Li, H., Li, Y., Tan, M., Fan, S., Cao, C., et al. (2019). Inhibiting neddylation modification alters mitochondrial morphology and reprograms energy metabolism in cancer cells. JCI Insight 4:e121582. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121582

Zhou, S., Zhao, X., Yang, Z., Yang, R., Chen, C., Zhao, K., et al. (2019). Neddylation inhibition upregulates PD-L1 expression and enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in glioblastoma. Int. J. Cancer 145, 763–774. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32379

Zhou, W., Xu, J., Li, H., Xu, M., Chen, Z. J., Wei, W., et al. (2017). Neddylation E2 UBE2F promotes the survival of lung cancer cells by activating CRL5 to degrade NOXA via the K11 linkage. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 1104–1116. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-16-1585

Zhou, X., Hao, Q., Liao, J., Zhang, Q., and Lu, H. (2013). Ribosomal protein S14 unties the MDM2-p53 loop upon ribosomal stress. Oncogene 32, 388–396. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.63

Zhou, X., Tan, M., Nyati, M. K., Zhao, Y., Wang, G., and Sun, Y. (2016). Blockage of neddylation modification stimulates tumor sphere formation in vitro and stem cell differentiation and wound healing in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E2935–E2944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522367113

Zhu, W., Chen, Y., and Dutta, A. (2004). Rereplication by depletion of geminin is seen regardless of p53 status and activates a G2/M checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7140–7150. doi: 10.1128/mcb.24.16.7140-7150.2004

Keywords: developmental down-regulation protein 8 (NEDD8), neddylation, MLN4924, treatment, cancer

Citation: Gai W, Peng Z, Liu C, Zhang L and Jiang H (2021) Advances in Cancer Treatment by Targeting the Neddylation Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:653882. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.653882

Received: 15 January 2021; Accepted: 10 March 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Tomokazu Tomo Fukuda, Iwate University, JapanReviewed by:

Guangyang Yu, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, United StatesLijun Jia, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Copyright © 2021 Gai, Peng, Liu, Zhang and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cui Hua Liu, bGl1Y3VpaHVhQGltLmFjLmNu; Lingqiang Zhang, emhhbmdscUBuaWMuYm1pLmFjLmNu; Hong Jiang, aG9uZ2ppYW5nQHFkdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wenbin Gai

Wenbin Gai Zhiqiang Peng

Zhiqiang Peng Cui Hua Liu

Cui Hua Liu Lingqiang Zhang

Lingqiang Zhang Hong Jiang

Hong Jiang