94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol. , 16 April 2021

Sec. Cell Growth and Division

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.649830

This article is part of the Research Topic Hair Bundles - Development, Maintenance, and Function View all 15 articles

Andre Landin Malt

Andre Landin Malt Shaylyn Clancy

Shaylyn Clancy Diane Hwang

Diane Hwang Alice Liu

Alice Liu Connor Smith

Connor Smith Margaret Smith

Margaret Smith Maya Hatley

Maya Hatley Christopher Clemens

Christopher Clemens Xiaowei Lu*

Xiaowei Lu*During development, sensory hair cells (HCs) in the cochlea assemble a stereociliary hair bundle on their apical surface with planar polarized structure and orientation. We have recently identified a non-canonical, Wnt/G-protein/PI3K signaling pathway that promotes cochlear outgrowth and coordinates planar polarization of the HC apical cytoskeleton and alignment of HC orientation across the cochlear epithelium. Here, we determined the involvement of the kinase Gsk3β and the small GTPase Rac1 in non-canonical Wnt signaling and its regulation of the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway in the cochlea. We provided the first in vivo evidence for Wnt regulation of Gsk3β activity via inhibitory Ser9 phosphorylation. Furthermore, we carried out genetic rescue experiments of cochlear defects caused by blocking Wnt secretion. We showed that cochlear outgrowth was partially rescued by genetic ablation of Gsk3β but not by expression of stabilized β-catenin; while PCP defects, including hair bundle polarity and junctional localization of the core PCP proteins Fzd6 and Dvl2, were partially rescued by either Gsk3β ablation or constitutive activation of Rac1. Our results identify Gsk3β and likely Rac1 as downstream components of non-canonical Wnt signaling and mediators of cochlear outgrowth, HC planar polarity, and localization of a subset of core PCP proteins in the cochlea.

Wnt signaling regulates a plethora of developmental processes through the canonical β-catenin-dependent pathway and the non-canonical β-catenin-independent pathway (Komiya and Habas, 2008; Wiese et al., 2018). Upon Wnt ligand binding to the Frizzled receptor, non-canonical Wnt signaling controls cell polarity and morphogenetic movements through the Rho family small GTPases or heterotrimeric G-proteins. In addition, the evolutionarily conserved planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway is a key regulator of tissue morphogenesis, whereby asymmetric localized core PCP protein complexes orient cell polarity and drive polarized cell behaviors within the plane of the tissue (Devenport, 2014). Specifically, two opposing asymmetric protein complexes, one consisting of homologs of Frizzled (Fzd) and Dishevelled (Dvl), and the other Van Gogh and Prickle, bridged across cell membranes by Flamingo (homolog of Celsr1-3), generate a polarity vector across the tissue plane (Butler and Wallingford, 2017). Because the non-canonical Wnt and PCP pathways share many components, including the Fzd receptor, as well as the effectors Dvl and Rho GTPases, the PCP pathway is often considered to be a branch of non-canonical Wnt signaling. However, emerging evidence suggests divergence of, and crosstalk between, the mammalian non-canonical Wnt and PCP pathways. The mammalian genome encodes 19 Wnt, 10 Fzd, and 3 Dvl genes. Fzd3/6 are components of the mammalian PCP pathway (Wang et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2016); however, to date, their specific Wnt ligands have not been identified (Sato et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2012; Voloshanenko et al., 2017). On the other hand, we and others have recently demonstrated that secreted Wnts are required for asymmetric localizations of a subset of PCP proteins in inner ear sensory epithelia, including Fzd3/6 and Dvl2 (Landin Malt et al., 2020; Najarro et al., 2020). Importantly, we have shown that asymmetric localization of Fzd6 is controlled by a Wnt/G-protein/PI3K signaling pathway (Landin Malt et al., 2020). In this study, we leverage the inner ear sensory epithelium and genetic tools available to further illuminate the precise relationship between the mammalian non-canonical Wnt and PCP pathways.

The mouse cochlear sensory epithelium, or the organ of Corti (OC), is a well-established system for studying PCP signaling (Tarchini and Lu, 2019). Crucial for their function as sound receptors, hair cells (HCs) in the OC project on their apical surface a V-shaped hair bundle consisting of rows of actin-based stereocilia organized in a staircase pattern. The vertices of all hair bundles are uniformly aligned along the medial-lateral axis of the cochlear duct. The polarized structure of hair bundles and other apical cytoskeletal elements define cell-intrinsic PCP (iPCP), while uniform hair bundle orientation is a hallmark of tissue-level PCP. Hair bundle formation is coincident with the migration of the microtubule-based kinocilium, which migrates to, and anchors at, the lateral edge of the HC and is tethered to the nascent hair bundle at its vertex. Thus, kinocilium positioning is crucial for hair bundle polarity and orientation. This process is coordinately controlled by intercellular PCP signaling, several iPCP signaling modules, and a novel, non-canonical Wnt/G-protein/PI3K signaling pathway (Tarchini and Lu, 2019; Landin Malt et al., 2020). To shed light on the crosstalk and integration of these signaling pathways, we sought to identify cochlear effectors of non-canonical Wnt signaling. Specifically, we focused on two candidates: the small GTPase Rac1 and the kinase Gsk3β. Rac1 has been shown to be activated by non-canonical Wnt signaling in cultured cells and mediate one of the iPCP signaling modules in the OC (Grimsley-Myers et al., 2009; Sato et al., 2010; Landin Malt et al., 2019). On the other hand, Gsk3β activity is inhibited by both canonical Wnt and PI3K/Akt signaling (Metcalfe and Bienz, 2011; Beurel et al., 2015). Here, we report that epithelium-secreted Wnts promote inhibitory phosphorylation of Gsk3β at Ser9 (S9) in the OC in vivo. We further show that cochlear growth, hair bundle polarity, and core PCP protein localization defects caused by blocking Wnt secretion are partially rescued by genetic ablation of Gsk3β in the cochlear epithelium, and to a lesser extent, constitutive activation of Rac1. Together, these findings identify both Gsk3β and Rac1 as effectors of non-canonical Wnt signaling crucial for hair bundle morphogenesis and cross-regulation of the PCP pathway.

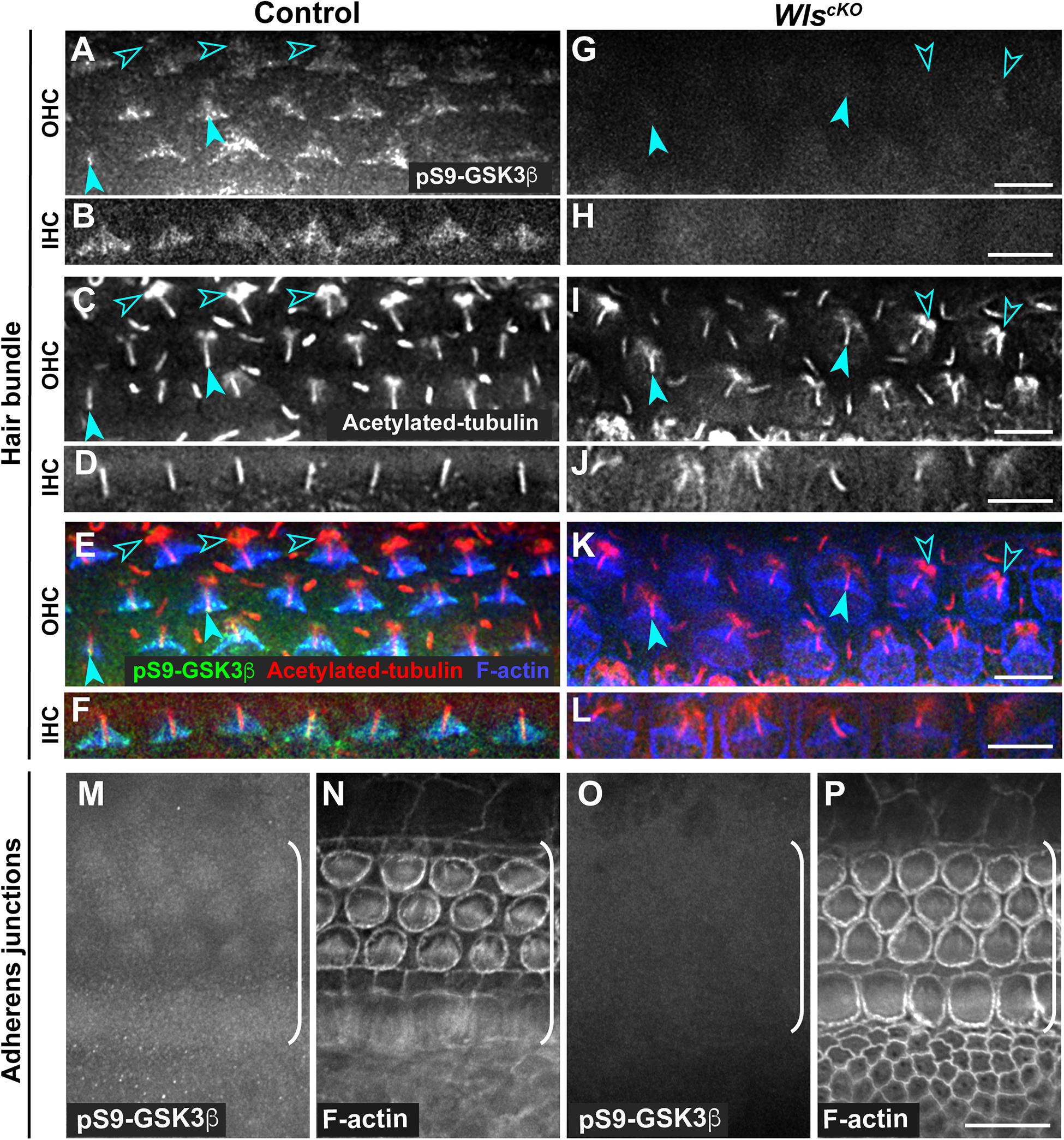

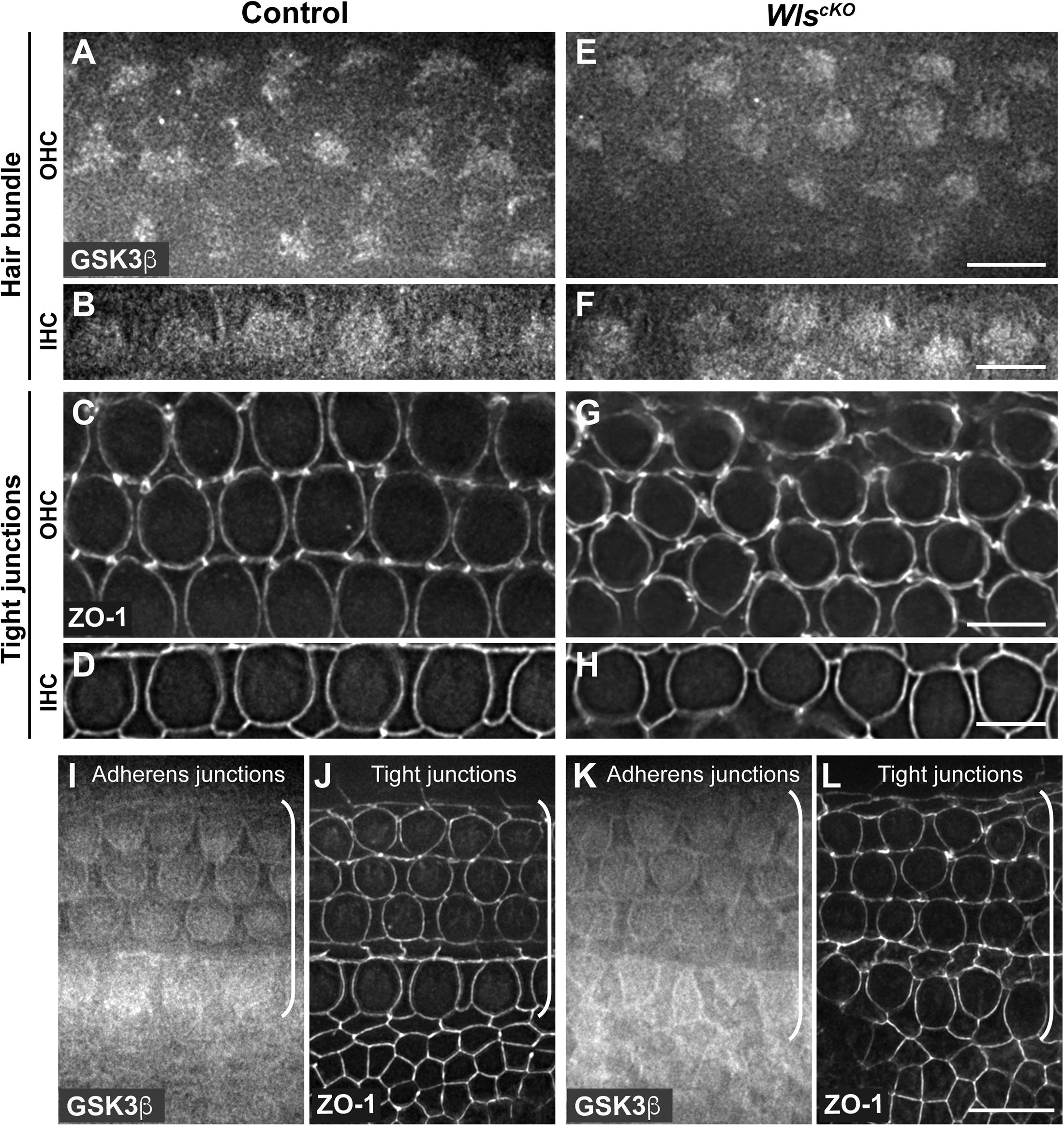

Conditional deletion of Wntless (Wls) driven by Emx2Cre (WlscKO) blocked Wnt secretion from the cochlear epithelium, resulting in stunted cochlear outgrowth and both PCP and iPCP defects. We have identified PI3K as a key effector of non-canonical Wnt signaling in the OC; PI3K activity was decreased in the WlscKO OC, and importantly, PI3K activation rescued most of the WlscKO cochlear phenotypes (Landin Malt et al., 2020). However, the downstream targets of PI3K crucial for cochlear morphogenesis remain unknown. Because PI3K activation of Akt leads to inhibitory phosphorylation of Gsk3β at S9 (Beurel et al., 2015), we examined the localization of pS9-Gsk3β as well as total Gsk3β in WlscKO cochleae, using commercial knockout (KO)-validated anti-pS9-Gsk3β and anti-Gsk3β antibodies. In the control cochlea at embryonic day (E)18.5, pS9-Gsk3β was enriched in the pericentriolar region (Figures 1A–F, open arrowheads), the tip of the kinocilium (Figures 1A–F, arrowheads), and the hair bundle in both inner and outer hair cells (IHCs and OHCs) (Figures 1A–F). In addition, diffused cytoplasmic staining of pS9-Gsk3β was detected in HCs, neighboring supporting cells (SCs), and non-sensory cells surrounding the OC (Figures 1M,N). In contrast, pS9-Gsk3β staining was greatly diminished at all subcellular locations in WlscKO cochleae (Figures 1G–L,O,P). On the other hand, total Gsk3β localization in WlscKO cochleae was similar to the control; Gsk3β was localized to the hair bundle (Figures 2A–H), at the adherens junctions in the OC and in the cytoplasm of both sensory and non-sensory cells (Figures 2I–L). The specificity of the observed staining patterns of pS9-Gsk3β and total Gsk3β was confirmed by their absence in the Gsk3βcKO cochleae driven by Emx2Cre (Supplementary Figures 1, 2). Thus, we conclude that epithelium-secreted Wnts regulate Gsk3β activity by promoting S9 phosphorylation in the developing cochlea.

Figure 1. Wnts promote inhibitory phosphorylation of Gsk3β at Ser9 in the cochlea. (A–L) pS9-Gsk3β (green), acetylated-tubulin (red), and phalloidin (blue) staining at the level of the hair bundle in control (A–F) and WlscKO (G–L) OC at E18.5. Open arrowheads indicate the pericentriolar region. Arrowheads indicate the tip of the kinocilium. (M–P) pS9-Gsk3β and phalloidin staining at the level of adherens junctions in control (M,N) and WlscKO (O,P) OC and surrounding regions. Brackets indicate the OC. Lateral is up. Scale bars: (A–L), 6 μm; (M–P), 10 μm.

Figure 2. Similar Gsk3β localizations in control and WlscKO cochleae. (A–H) Gsk3β staining at the level of hair bundle and ZO-1 staining at the level of tight junctions in control (A–D) and WlscKO (E–H) OC at E18.5. (I–L) Gsk3β staining at the level of adherens junctions and ZO-1 staining at the level of tight junctions in control (I,J) and WlscKO (K,L) OC and surrounding regions. Brackets indicate the OC. Lateral is up. Scale bars: (A–L), 6 μm; (M–P), 10 μm.

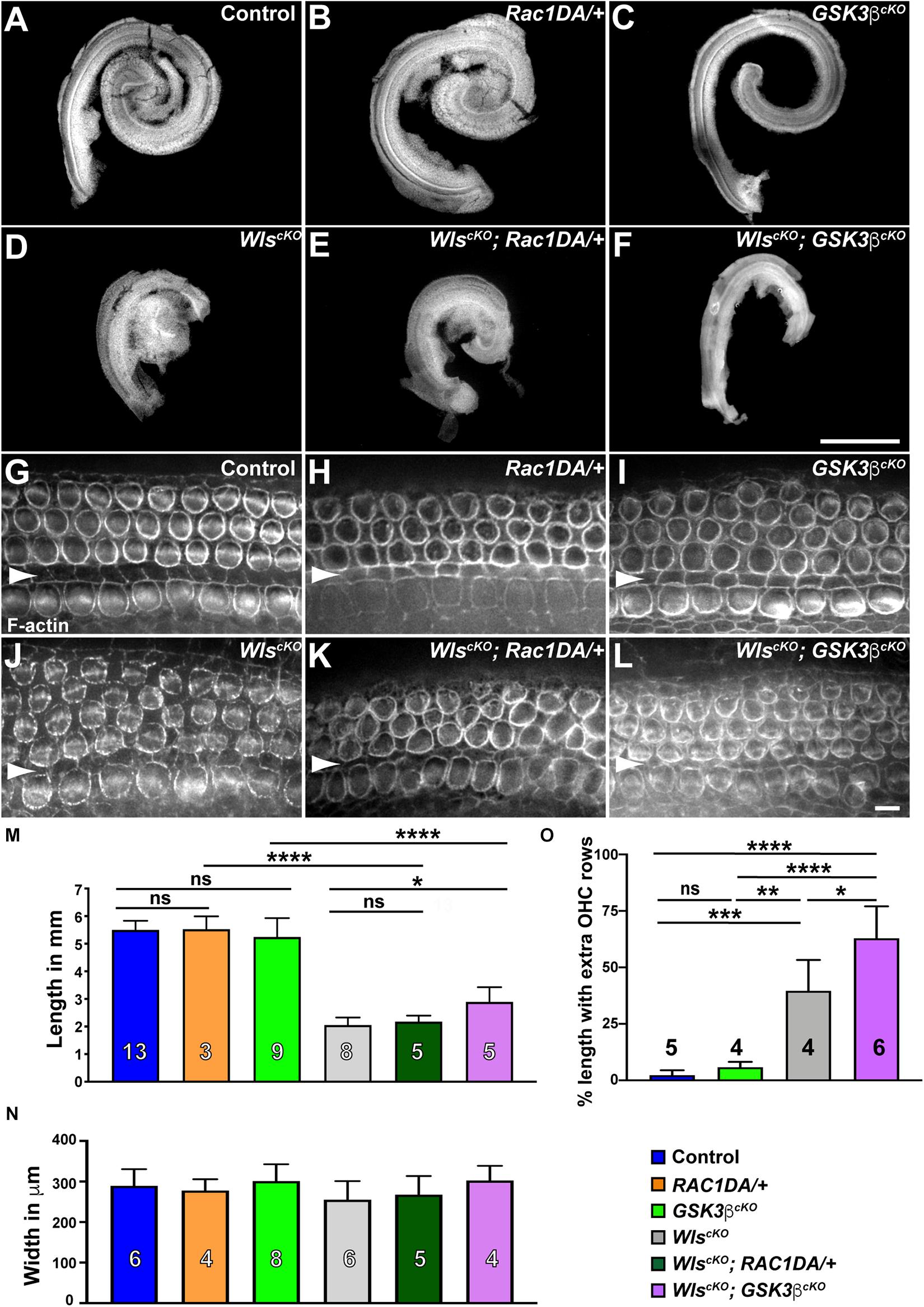

Activation of Rac1 by non-canonical Wnt signaling has been well established in cultured cells; therefore, we hypothesized that Rac1 mediates non-canonical Wnt signaling in the cochlea. To test this, we asked whether constitutive activation of Rac1 was able to rescue cochlear defects of WlscKO mutants. Specifically, we crossed a Cre-inducible, constitutively active Rac1-G12V transgene (R26-LSL-Rac1DA) into WlscKO embryos. We first measured the length of WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ compound mutant cochleae at E18.5. As a control, expression of Rac1-G12V in the cochlear epithelium driven by Emx2Cre (Rac1DA/+) did not significantly alter cochlear length, width, or OC patterning (Figures 3A,B,G,H,M,N). Moreover, Rac1-G12V expression in Wls-deficient cochlear epithelia did not rescue the cochlear length (Figures 3D,E,J,K,M).

Figure 3. Gsk3β inactivation but not Rac1 activation partially rescued cochlear outgrowth of WlscKO mutant. (A–F) Dissected cochlear ducts from E18.5 wild-type control (A), Rac1DA/+ (B), Gsk3βcKO (C), WlscKO (D), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (E), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (F) mutants. (G–L) Flat-mounted OC from the middle region (40–60% cochlear length) of wild-type control (G), Rac1DA/+ (H), Gsk3βcKO (I), WlscKO (J), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (K), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (L) cochleae stained by phalloidin. Arrowheads indicate the inner pillar cell row. Lateral is up. Scale bars: (A–F), 1 mm; (G–L), 6 μm. (M–O) Quantifications of cochlear length (M), cochlear duct width (N), and presence of extra OHC rows (O) in genotypes indicated by the color keys. Cochlear duct width (N) was not significantly different in all pair-wise comparisons. The number of cochleae analyzed is indicated. Ns, not significant.

Next, we analyzed the Gsk3βcKO cochleae to determine the role of Gsk3β in Wnt-mediated cochlear outgrowth. At E18.5, Gsk3βcKO cochleae had largely normal length and OC patterning (Figures 3A,C,G,I,M–O), suggesting that the function of Gsk3 in cell fate regulation at earlier stages was spared in Gsk3βcKO mutants (Ellis et al., 2019). In contrast to Rac1 activation, the length of the WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO compound mutant cochleae was partially but significantly rescued, and an intermittent extra OHC row was present along ∼60% of the total cochlear length (Figures 3D,F,J,L–O). As Gsk3β inactivation, but not Rac1 activation, partially rescued cochlear outgrowth defects of WlscKO mutants, we conclude that Wnt signaling promotes cochlear outgrowth in part through Gsk3β inhibition.

Gsk3 inhibition is a key step in canonical Wnt signaling; sequestration of Gsk3 prevents phosphorylation of β-catenin, thereby stabilizing β-catenin, which translocates into the nucleus and partners with TCF transcription factors to activate Wnt target gene expression (Wiese et al., 2018). During cochlear development, canonical Wnt signaling promotes cell proliferation of otic precursors in the prosensory domain (Jacques et al., 2012). To determine whether the partial rescue of cochlear outgrowth observed in WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO mutants was due to activation of canonical Wnt signaling, we induced the expression of a stabilized β-catenin mutant in the cochlear epithelium by crossing an exon3-floxed β-catenin (Ctnnb1flox(ex3)) allele into WlscKO mutants. Deletion of exon3 driven by Emx2Cre generated a mutant form of β-catenin refractory to inhibitory phosphorylation by Gsk3. Surprisingly, expression of stabilized β-catenin by itself resulted in a shortened cochlea, and cochlear outgrowth was severely stunted in the WlscKO; Ctnnb1Δ ex3/+ compound mutants (Supplementary Figures 3C,D), precluding dissection and assessment of the OC. These results suggest that Gsk3β regulation of cochlear outgrowth is not mediated by stabilization of β-catenin.

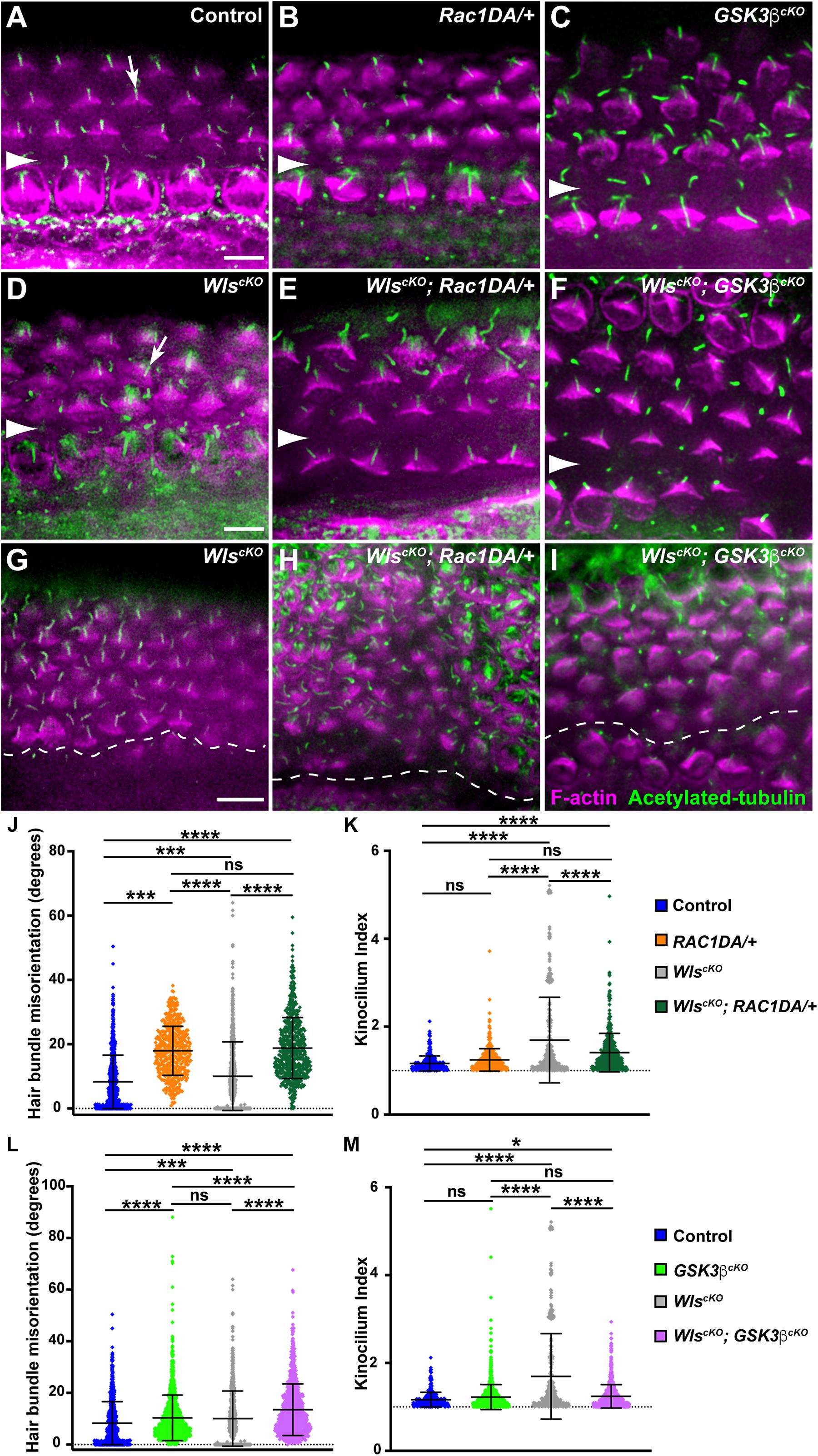

Similar iPCP defects were observed in WlscKO and Rac1-deficient cochleae, including misoriented and misshapen hair bundles with an off-center kinocilium (Grimsley-Myers et al., 2009; Landin Malt et al., 2020), consistent with Rac1 being a downstream effector of Wnt-regulated hair bundle polarity. To test this, we examined hair bundle orientation and kinocilium positioning in WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ cochleae at E18.5. Compared with the wild-type control, Rac1DA/+ had mild but significant hair bundle misorientation (Figures 4A,B,J and Supplementary Figure 4), consistent with the crucial role of localized Rac1 activity in hair bundle orientation (Grimsley-Myers et al., 2009). Interestingly, hair bundle misorientation in WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ cochleae was more severe than the WlscKO mutants (Figures 4E,H,J and Supplementary Figure 4), particularly toward the cochlear apex where many supernumerary, disorganized OHC rows were present (Figures 4G,H).

Figure 4. Partial rescue of hair bundle defects of Wls-deficient mutants by Rac1 activation and Gsk3β inactivation. (A–I) Flat-mounted E18.5 OC stained for acetylated tubulin (green) and F-actin (magenta). (A–F) Basal or mid-basal regions of wild-type control (A), Rac1DA/+ (B), Gsk3βcKO (C), WlscKO (D), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (E), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO OC (F). Arrows in panels (A,D) indicate normal kinocilium position at the hair bundle vertex and an off-center kinocilium, respectively. (G–I) Apical regions of WlscKO (G), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (H), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (I) OC. Arrowheads and the dashed line indicate the inner pillar cell row. Lateral is up. Scale bars: 6 μm. (J–M) Quantifications of hair bundle orientation (J,L) and kinocilium positioning (K,M). Color keys for genotypes are indicated on the right. Ns, not significant.

We next assessed the effect of Rac1 activation on kinocilium positioning within the hair bundle by measuring the kinocilium index (Landin Malt et al., 2020). In the wild type at E18.5, the kinocilium is found at the vertex of the V-shaped hair bundle, with a mean kinocilium index (KI) of 1.16, whereas many hair bundles in WlscKO cochleae had an off-center kinocilium, as shown previously (Figures 4A,D, arrows). Rac1 activation by itself had negligible effect on the KI (mean = 1.24; Figures 4B,K). In the WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ cochleae, kinocilium positioning was partially but significantly rescued compared with WlscKO mutants (Figures 4E,K). Thus, partial rescue of kinocilium positioning but not hair bundle orientation defects of WlscKO mutants by Rac1 activation supports the proposed role of Rac1 as a downstream effector of Wnt-mediated hair bundle polarity.

To determine the role of Gsk3β in hair bundle morphogenesis, we first analyzed hair bundle orientation and kinocilium positioning in Gsk3βcKO cochleae at E18.5. Interestingly, Gsk3βcKO mutants had mild but significant hair bundle misorientation, indicating a requirement of Gsk3β for normal hair bundle orientation (Figures 4C,L and Supplementary Figure 4). On the other hand, the normal V-shape of the hair bundle and kinocilium positioning at the hair bundle vertex were largely intact in Gsk3βcKO cochleae (Figures 4C,M).

Next, we assessed the effect of Gsk3β inactivation on hair bundle defects in WlscKO mutants. Interestingly, in WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO OC at E18.5, hair bundle misorientation was worse than in either single mutant (Figures 4F,I,L and Supplementary Figure 4). However, kinocilium positioning at the vertex of the hair bundle was significantly rescued compared with WlscKO mutants (Figures 4F,I,M). Taken together, these results indicate that a normal level of Gsk3β signaling is required for hair bundle orientation and that Wnts control hair bundle morphogenesis in part through inhibition of Gsk3β.

Our results so far suggest that both Rac1 and Gsk3β are downstream effectors of non-canonical Wnt signaling crucial for HC PCP. To further elucidate their roles in PCP establishment in the OC, we sought to determine whether Rac1 and Gsk3β also play a role in Wnt-dependent asymmetric localization of core PCP proteins.

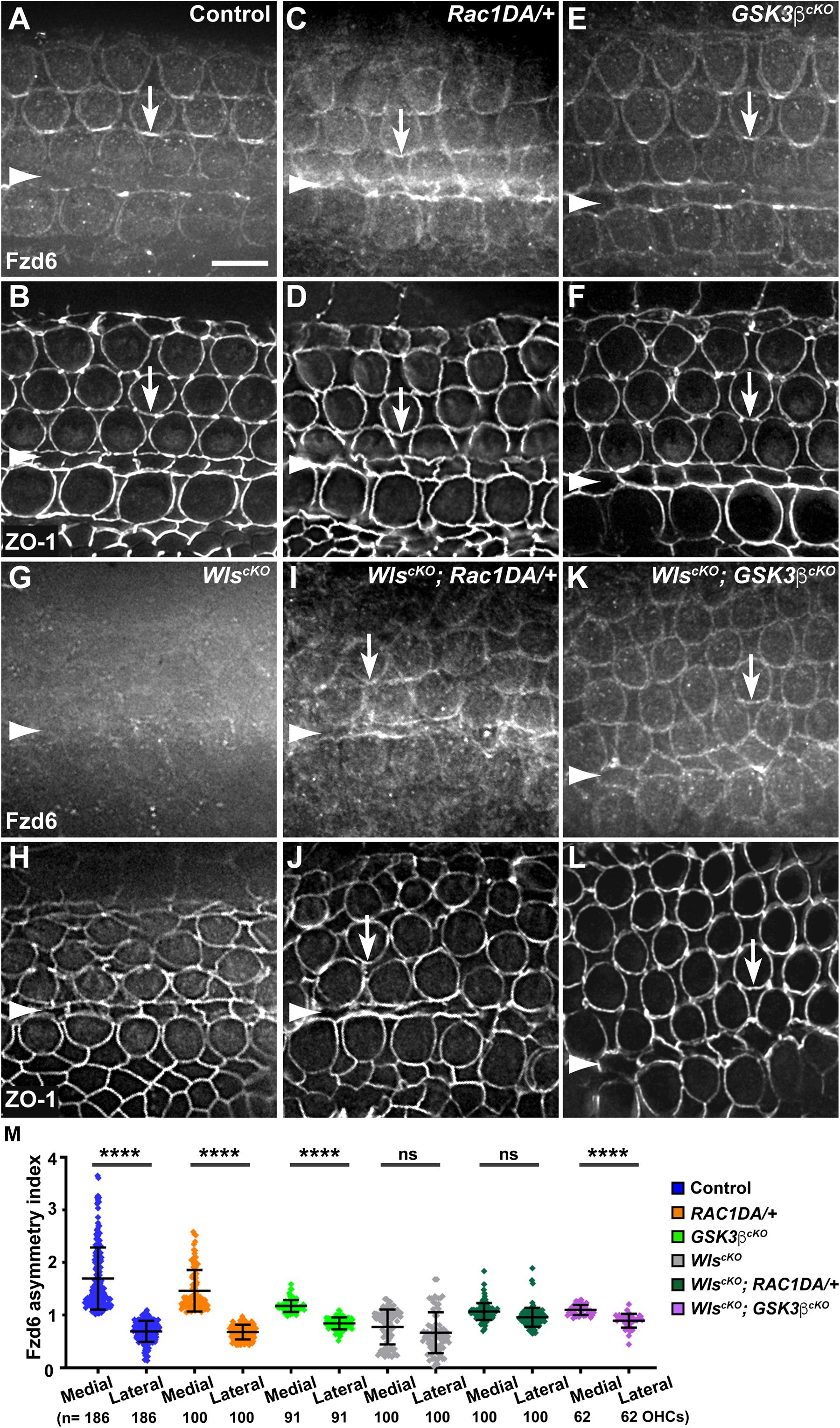

We and others previously uncovered a requirement of secreted Wnt ligands in asymmetric junctional localization of a subset of core PCP proteins (Landin Malt et al., 2020; Najarro et al., 2020). Specifically, Fzd6 is normally enriched along the medial border of HCs (Figures 5A,B, arrows, 7A), and this localization was abolished in the WlscKO cochleae (Figures 5G,H, 7D). Similar to the control, we found that Fzd6 was enriched along medial HC junctions in both the Rac1DA/+ and Gsk3βcKO cochleae (Figures 5C–F, 7B,C). Interestingly, junctional Fzd6 localization was significantly recovered in both WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO cochleae; however, Fzd6 planar asymmetry along the medial-lateral axis was not restored in WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ and only partially restored in WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO cochleae (Figures 5I–M, 7E,F).

Figure 5. Rac1 activation and Gsk3β inactivation recovered Fzd6 junctional localization but not planar asymmetry in Wls-deficient OC. (A–L) Flat-mounted E18.5 wild-type control (A,B), Rac1DA/+ (C,D), Gsk3βcKO (E,F), WlscKO (G,H), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (I,J), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (K,L) OC stained for Fzd6 and ZO-1 as indicated. Arrows indicate Fzd6 crescents along the medial borders of OHCs. Arrowheads indicate the inner pillar cell row. Lateral is up. Scale bar: 6 μm. (M) Quantifications of Fzd6 staining along the medial and lateral junctions of OHCs. Numbers of OHCs scored are indicated on the bottom. Color keys for genotypes are indicated on the right. Ns, not significant.

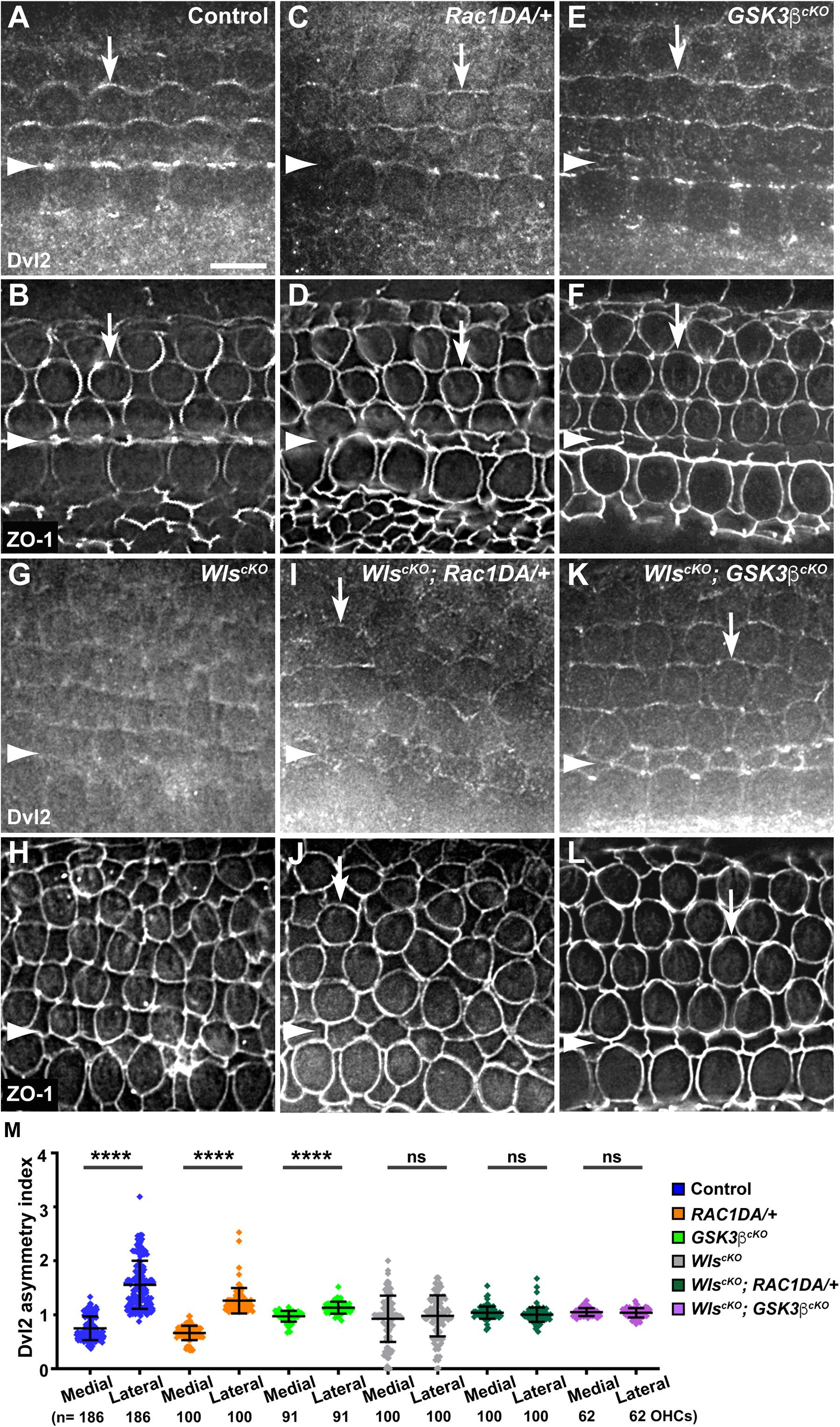

Another Wnt-dependent core PCP protein, Dvl2, is normally enriched along the lateral border of HCs (Figures 6A,B, arrows, 7A) and lost its junctional localization in the WlscKO cochleae (Figures 6G,H, 7D). In both the Rac1DA/+ and Gsk3βcKO cochleae, enrichment of Dvl2 on the lateral HC junctions was largely intact (Figures 6C–F, arrows, 7B,C). In WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO OC, junctional Dvl2 localization was partially recovered (Figures 6I–L, arrows, 7E,F). However, Dvl2 planar asymmetry was not restored in either compound mutant (Figure 6M). Together, these results indicate that both Rac1 and Gsk3β are involved in Wnt-mediated junctional localization of a subset of core PCP proteins; however, neither Rac1 activation nor Gsk3β inactivation was sufficient for generating planar asymmetry of core PCP proteins.

Figure 6. Effects of Rac1 activation and Gsk3β inactivation on Dvl2 localization in Wls-deficient OC. (A–L) Flat-mounted E18.5 wild-type control (A,B), Rac1DA/+ (C,D), Gsk3βcKO (E,F), WlscKO (G,H), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (I,J), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (K,L) OC stained for Dvl2 and ZO-1 as indicated. Arrows indicate Dvl2 crescents along the lateral borders of OHCs. Arrowheads indicate the inner pillar cell row. Lateral is up. Scale bar: 6 μm. (M) Quantifications of Dvl2 staining along the medial and lateral junctions of OHCs. Numbers of OHCs scored are indicated on the bottom. Color keys for genotypes are indicated on the right. Ns, not significant.

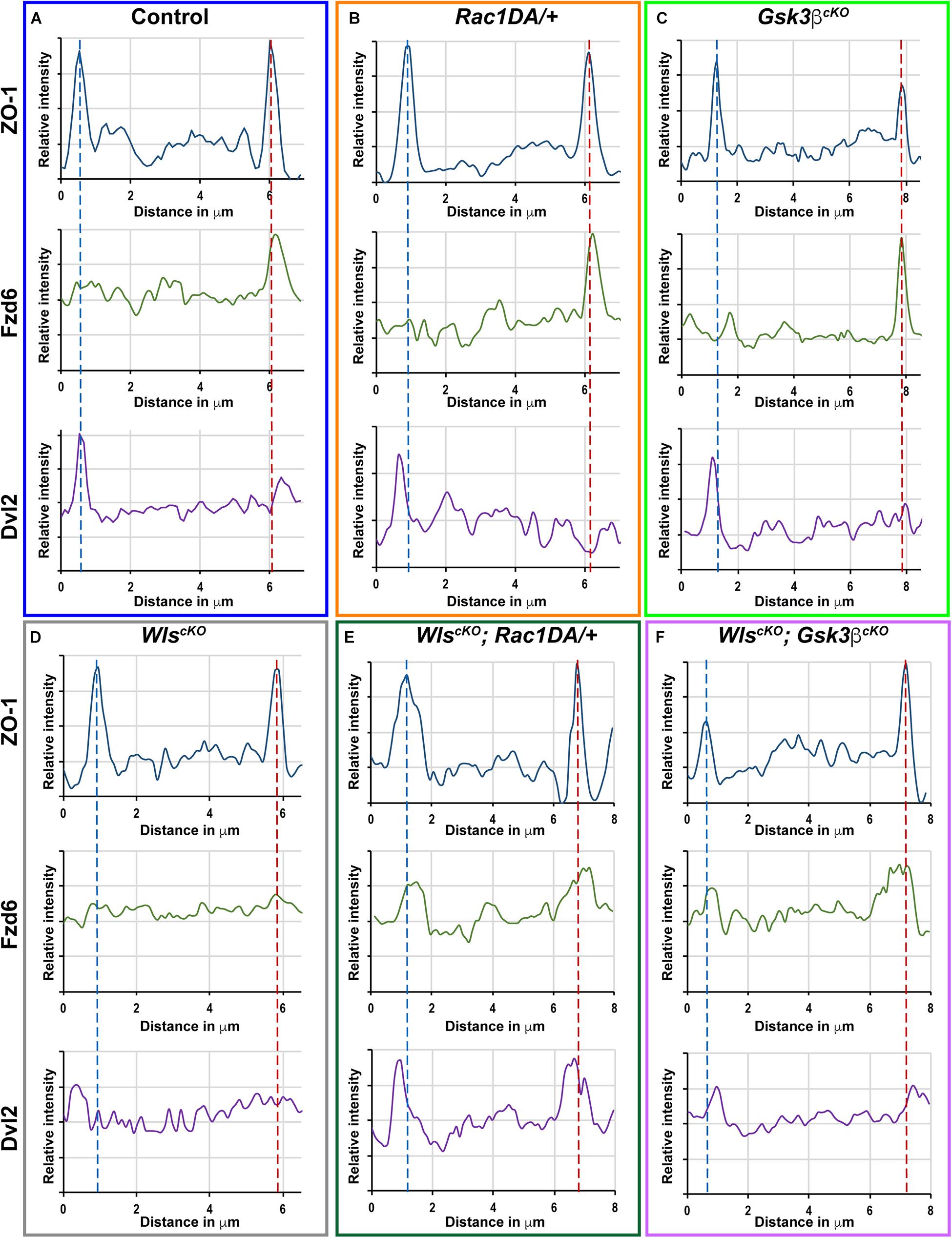

Figure 7. Linescan analysis of junctional localization of Fzd6 and Dvl2 in outer hair cells. (A–F) Representative linescans of individual OHCs from E18.5 wild-type control (A), Rac1DA/+ (B), Gsk3βcKO (C), WlscKO (D), WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ (E), and WlscKO; Gsk3βcKO (F) OC stained for ZO-1, Fzd6, and Dvl2. For each genotype, a line was drawn parallel to the medial–lateral axis bisecting the OHC. Intensity profiles of each image channel were aligned along the distance axis. The lateral and medial junctions of the OHC were identified by peaks of ZO-1 staining and indicated by the blue and red dashed lines, respectively. Junctional Fzd6 and Dvl2 staining was defined by peaks in close proximity to the lateral or medial borders of the OHC.

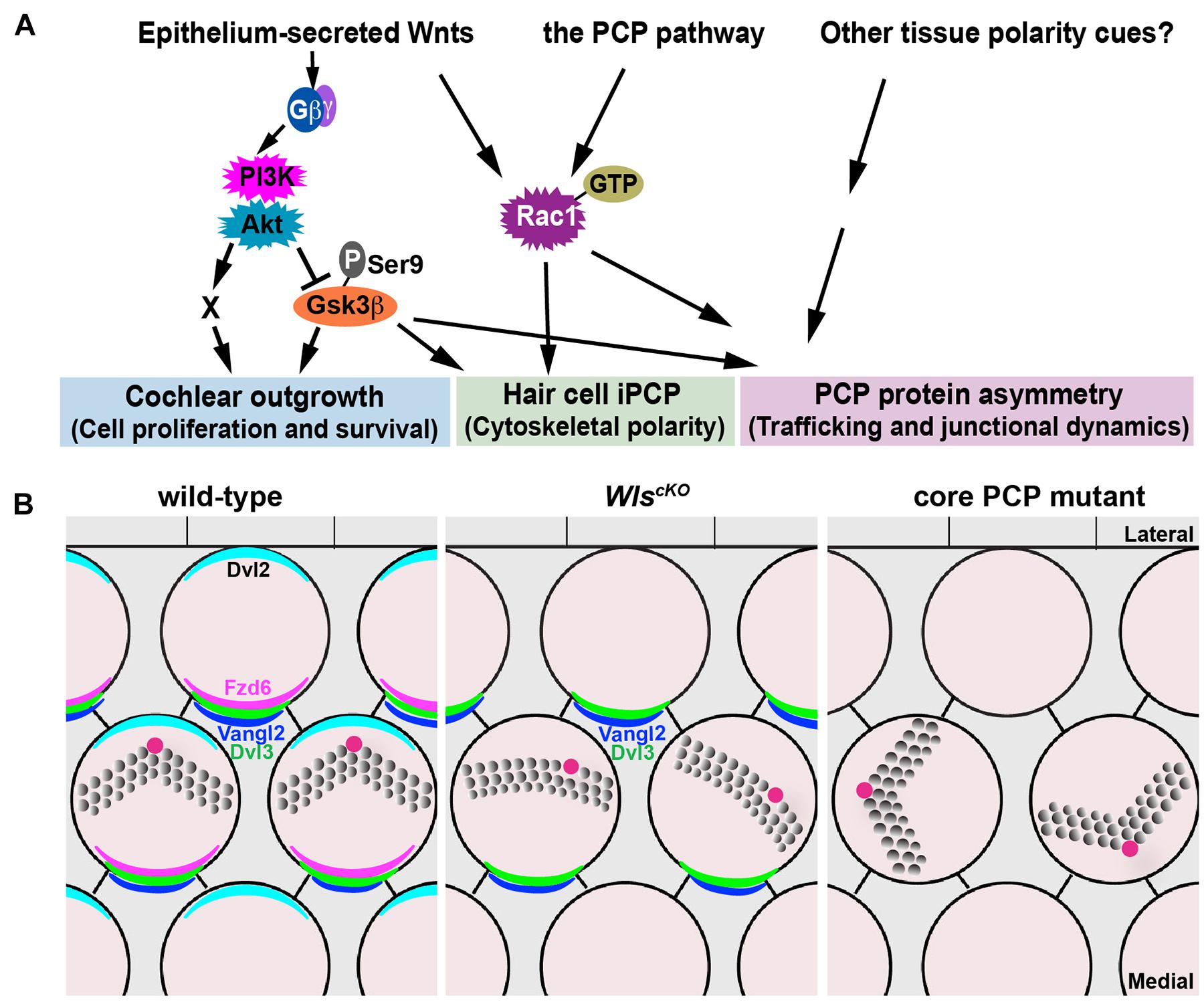

In this study, we have further delineated the non-canonical, Wnt/G-protein/PI3K pathway for cochlear outgrowth and establishment of iPCP and PCP in the cochlea (Figure 8A). Our genetic rescue experiments have provided strong evidence that PI3K, Gsk3β, and Rac1 are all downstream effectors of non-canonical Wnt signaling in the cochlea. The extent to which the cochlear defects of WlscKO mutants were rescued varied among the effectors. Thus, these effectors likely act in parallel and have non-overlapping functions to mediate non-canonical Wnt signaling in the cochlea.

Figure 8. Non-canonical Wnt and PCP pathways act in concert to regulate cochlear morphogenesis. (A) A working model for the concerted actions of the non-canonical Wnt and PCP pathways in regulating different aspects of cochlear morphogenesis. (B) Schematic diagrams comparing PCP defects in the WlscKO and core PCP mutant OC. Kinocilium (the red dot) positioning at the hair bundle vertex was disrupted in WlscKO but not core PCP mutants.

Cochlear elongation is regulated by multiple developmental signals from the epithelium and surrounding mesenchyme and spiral ganglion (Bok et al., 2013; Huh et al., 2015), suggesting integration of multiple molecular pathways. Within the epithelium, while PCP signaling is thought to mediate convergent extension of the OC (Mao et al., 2011; Montcouquiol and Kelley, 2019), the mechanisms underlying Wnt-mediated cochlear elongation remain incompletely understood. We showed that outgrowth of WlscKO cochleae was rescued fully by PI3K activation and partially by Gsk3β inactivation but not rescued by Rac1 activation or expression of stabilized β-catenin, suggesting that Wnt/G-protein/PI3K signaling engages Gsk3β and additional regulators (“X”; Figure 8A) to promote cell proliferation and/or cell survival during cochlear outgrowth.

Our findings suggest that Wnts secreted by the cochlear epithelium act in parallel and crosstalk with the PCP pathway in the mammalian cochlea. Of note, WlscKO and core PCP mutants have distinct hair bundle phenotypes: hair bundle misorientation in WlscKO cochleae was milder than core PCP mutants; moreover, WlscKO but not PCP mutants were defective in kinocilium positioning at the hair bundle vertex (Figure 8B). Epithelium-secreted Wnt ligands likely act in concert with additional tissue polarity cues, including non-epithelial Wnts, to specify the PCP vector and align HC orientation (Figure 8A). Epithelium-secreted Wnt5a, a prototype non-canonical Wnt, is dispensable for cochlear PCP (Najarro et al., 2020), suggesting involvement of other Wnt ligands. In the future, identification of the relevant Wnt ligands in the cochlea will help determine permissive versus instructive roles of Wnt signaling in HC PCP. Importantly, we have uncovered a non-canonical Wnt pathway that signals through PI3K, Rac1, and Gsk3β to promote junctional localization of a subset of core PCP proteins, including Fzd6 and Dvl2, thereby cross-regulating the PCP pathway. This is in stark contrast to the Drosophila PCP pathway, which operates independently of Wnt ligands (Bartscherer et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008; Ewen-Campen et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Wnt signaling may regulate the trafficking of PCP proteins or HC–SC junctional dynamics, which in turn influences asymmetric PCP protein localization (see below).

Although Rac1 is activated by non-canonical Wnt signaling in cultured cells, it remains to be determined whether Wnt signaling stimulates Rac1 activity in the cochlea. At present, we have been unable to address this question, as our attempts to evaluate the localization and levels of active Rac1 by immunostaining or Western blot using a commercially sourced Rac1-GTP-specific antibody were unsuccessful. Thus, more sensitive and specific tools are needed to detect active Rac1 in vivo. PCP defects caused by modest overexpression of Rac1-G12V expression were mild, likely due to the presence of wild-type Rac proteins undergoing the normal GTPase cycle. In the WlscKO; Rac1DA/+ OC, Fzd6 and Dvl2 junctional localization was partially rescued, consistent with Rac1 being a downstream effector of non-canonical Wnt signaling. Rac1 may promote Fzd6 and Dvl2 junctional localization through regulation of junctional and cytoskeletal dynamics (de Curtis and Meldolesi, 2012). In previous studies, we have shown that the activity of p21-activated kinases (PAKs), which are downstream effectors of both Rac1 and Cdc42, are regulated in the OC by multiple mechanisms, including intercellular PCP signaling, plus- and minus-end-directed microtubule motors and the cell polarity protein Par3 (Grimsley-Myers et al., 2009; Sipe and Lu, 2011; Sipe et al., 2013; Landin Malt et al., 2019). Therefore, multiple signaling pathways, including the non-canonical Wnt pathway, likely converge on Rac1 to tightly control its activity in space and time during HC planar polarization.

We show, for the first time, that Wnts secreted by the cochlear epithelium promote inhibitory Ser9 phosphorylation of Gsk3β in vivo. This is different from the mode of Gsk3β inhibition by canonical Wnt signaling, which is thought to occur through sequestration of Gsk3β and dissociation of the disruption complex (Metcalfe and Bienz, 2011; Beurel et al., 2015). Previous studies using pharmacological inhibitors have shown that Gsk3 signaling regulates OC progenitor cell proliferation and fate decision (Jacques et al., 2012; Ellis et al., 2019). Our genetic analyses further reveal multi-faceted roles of Gsk3β in PCP and iPCP regulation in vivo. First, Gsk3β is required for uniform hair bundle orientation. Second, Gsk3β inhibition is crucial for Wnt-dependent kinocilium positioning and junctional localization of Fzd6 and Dvl2. Interestingly, both too little (in Gsk3βcKO mutants) and too much Gsk3β activity (in WlscKO mutants) led to hair bundle orientation defects, suggesting that levels of Gsk3β need to be precisely controlled to achieve uniform HC orientation. In the future, it would be interesting to assess earlier roles of Gsk3β in cochlear patterning in vivo by deleting Gsk3β in the otocyst.

Gsk3β is a promiscuous kinase with numerous known substrates. The crucial Gsk3β targets that mediate kinocilium positioning and PCP protein localization remain to be identified. Gsk3β has a well-established role in regulating neuronal cytoskeletal dynamics through phosphorylation of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) including collapsin response mediator proteins (CRMPs), APC, Tau, MAP1B, and doublecortin (Hur and Zhou, 2010; Morgan-Smith et al., 2014). In the OC, microtubules and microtubule-based motors have been implicated in hair bundle orientation and kinocilium positioning (Sipe and Lu, 2011; Ezan et al., 2013; Sipe et al., 2013). In addition, cytoskeletal molecules disrupted in Usher syndrome and ciliopathies also play a role in hair bundle polarity (Lefevre et al., 2008; Jagger et al., 2011). Thus, HC microtubule and other cytoskeletal regulators are potential targets of Gsk3β during hair bundle morphogenesis.

In other systems, microtubules are also involved in polarized trafficking of core PCP proteins (Vladar et al., 2012; Matis et al., 2014). However, asymmetric PCP protein localization was normal in several mutants affecting HC microtubule organization or transport (Sipe and Lu, 2011; Kirjavainen et al., 2015; Siletti et al., 2017), suggesting alternative mechanisms by which Gsk3β regulates PCP protein localization/trafficking. Interestingly, Gsk3β has been shown to regulate endocytosis/recycling of membrane cargos in different cell types (Roberts et al., 2004; Clayton et al., 2010; Reis et al., 2015; Ferreira et al., 2020). Future investigations will shed light on the mechanisms by which Gsk3β influences HC polarity and core PCP protein trafficking in the OC.

Animal care and use was performed in compliance with the NIH guidelines and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia. Wlsflox (Fu et al., 2011), Gsk3βflox (Patel et al., 2008), and R26-LSL-Rac1DA (Srinivasan et al., 2009) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Stock #012888, #029592, and #012361, respectively). Ctnnb1flox(ex3) and Emx2Cre mice have been described (Harada et al., 1999; Ono et al., 2014). All mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background. To generate Wls conditional and compound mutants, Wlsflox/+; Emx2Cre/+ males were mated with Wlsflox/flox, Wlsflox/flox; R26-LSL-Rac1DA/+, or Wlsflox/flox; Ctnnb1flox(ex3)/+ females, and Wlsflox/+; Gsk3βflox/+; Emx2Cre/+ males with Wlsflox/flox; Gsk3βflox/flox females. For timed pregnancies, the morning of the plug was designated as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5), and the day of birth postnatal day 0 (P0).

Mouse skulls were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 45 min at room temperature (RT) or in 10% TCA for 1 h on ice, then washed three times in PBS. Dissected cochleae were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 5% heat-inactivated horse serum, and 0.02% NaN3 for 1 h at RT, then incubated with primary antibodies for 16–32 h at 4°C. After three washes in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies and phalloidin for 2 h at RT, washed twice in PBS 0.1% Triton X-100, post-fixed for 15 min at RT in 4% paraformaldehyde and then washed two more times. Stained samples are flat mounted in Mowiol with 5% N-propyl gallate. The table above lists the antibodies used.

Control and mutant samples were imaged under identical conditions. For hair bundle and PCP protein localization, images were collected using a Deltavision deconvolution microscope with a 60×/1.35 NA oil-immersion objective controlled by SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision). Whole-mount cochlear ducts were imaged using a Leica MZ16F stereomicroscope. Images were processed using Fiji (National Institutes of Health) and Photoshop (Adobe).

Hair bundle orientation and kinocilium position within the hair bundle along the entire cochlear length were quantified as previously described (Landin Malt et al., 2020). In brief, the hair bundle is labeled by phalloidin staining and the kinocilium by anti-acetylated tubulin staining. A hair bundle with its vertex pointing to the lateral or medial edge of the cochlear duct has a misorientation of 0° and 180°, respectively. The kinocilium index is the length ratio of the long and short hair bundle “halves” as bisected by the kinocilium.

Fzd6 and Dvl2 immunostaining along OHC-Deiters cell junctions from the basal to mid-apical regions was quantified using Fiji, as previously described (Landin Malt et al., 2020). The cochlear apex, where HC–SC junctions were more irregular/less mature, was excluded. In brief, single optic sections with the strongest junctional staining intensity were chosen for each imaging channel. In general, lateral Dvl2 crescents are localized at the level of the tight junction, while medial Fzd6 crescents are localized at a level about 1 μm below the tight junction. Cell junctions were identified using ZO-1 staining. A 30 × 10−, 20 × 10−, and 30 × 5-pixel region of interest (ROI) centered around the medial, lateral, and orthogonal OHC junctions, respectively, was then selected. Following background subtraction, mean fluorescence intensity of Fzd6 or Dvl2 staining for the medial or lateral ROI was normalized to that of the orthogonal ROI of the same OHC and plotted as the asymmetry index.

Line scan analysis was performed using Fiji and Excel to demonstrate the localization of Fzd6 and Dvl2 staining relative to cell junctions. Specifically, a diametral line was drawn intersecting the lateral and medial OHC junctions as marked by ZO-1 immunostaining. Following background subtraction, fluorescence intensity of each imaging channel was plotted in the lateral to medial direction of the line.

Statistical analysis of at least three cochleae from three different litters was performed using GraphPad Prism. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test. p-Values for statistical significance are defined as follows: ∗p ≤ 0.0332; ∗∗p ≤ 0.0021; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0002, and ****p ≤ 0.0001. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia.

ALM and XL designed the research, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SC performed the experiments and analyzed the data. DH, AL, CS, MS, MH, and CC analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by NIH grant R01DC013773 (XL).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Wenxia Li for the technical assistance and Dr. Jeremy Nathans (the Johns Hopkins University) for the reagents.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.649830/full#supplementary-material

Bartscherer, K., Pelte, N., Ingelfinger, D., and Boutros, M. (2006). Secretion of Wnt ligands requires Evi, a conserved transmembrane protein. Cell 125, 523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.009

Beurel, E., Grieco, S. F., and Jope, R. S. (2015). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 148, 114–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016

Bok, J., Zenczak, C., Hwang, C. H., and Wu, D. K. (2013). Auditory ganglion source of Sonic hedgehog regulates timing of cell cycle exit and differentiation of mammalian cochlear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110:13869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222341110

Butler, M. T., and Wallingford, J. B. (2017). Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 375–388.

Chang, H., Smallwood, P. M., Williams, J., and Nathans, J. (2016). The spatio-temporal domains of Frizzled6 action in planar polarity control of hair follicle orientation. Dev. Biol. 409, 181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.10.027

Chen, W. S., Antic, D., Matis, M., Logan, C. Y., Povelones, M., Anderson, G. A., et al. (2008). Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell 133, 1093–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.048

Clayton, E. L., Sue, N., Smillie, K. J., O’Leary, T., Bache, N., Cheung, G., et al. (2010). Dynamin I phosphorylation by GSK3 controls activity-dependent bulk endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 845–851. doi: 10.1038/nn.2571

de Curtis, I., and Meldolesi, J. (2012). Cell surface dynamics – how Rho GTPases orchestrate the interplay between the plasma membrane and the cortical cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 125, 4435. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108266

Devenport, D. (2014). The cell biology of planar cell polarity. J. Cell Biol. 207, 171–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201408039

Ellis, K., Driver, E. C., Okano, T., Lemons, A., and Kelley, M. W. (2019). GSK3 regulates hair cell fate in the developing mammalian cochlea. Dev. Biol. 453, 191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.06.003

Ewen-Campen, B., Comyn, T., Vogt, E., and Perrimon, N. (2020). No evidence that Wnt ligands are required for planar cell polarity in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 32:108121. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108121

Ezan, J., Lasvaux, L., Gezer, A., Novakovic, A., May-Simera, H., Belotti, E., et al. (2013). Primary cilium migration depends on G-protein signalling control of subapical cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1107–1115. doi: 10.1038/ncb2819

Ferreira, A. P. A., Casamento, A., Roas, S. C., Panambalana, J., Subramaniam, S., Schützenhofer, K., et al. (2020). Cdk5 and GSK3β inhibit fast Endophilin-mediated endocytosis. bioRxiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.11.036863

Fu, J., Ivy Yu, H. M., Maruyama, T., Mirando, A. J., and Hsu, W. (2011). Gpr177/mouse Wntless is essential for Wnt-mediated craniofacial and brain development. Dev. Dyn. 240, 365–371. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22541

Grimsley-Myers, C. M., Sipe, C. W., Geleoc, G. S., and Lu, X. (2009). The small GTPase Rac1 regulates auditory hair cell morphogenesis. J. Neurosci. 29, 15859–15869. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3998-09.2009

Harada, N., Tamai, Y., Ishikawa, T., Sauer, B., Takaku, K., Oshima, M., et al. (1999). Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 18, 5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931

Huh, S. H., Warchol, M. E., and Ornitz, D. M. (2015). Cochlear progenitor number is controlled through mesenchymal FGF receptor signaling. Elife 4:e05921.

Hur, E. M., and Zhou, F. Q. (2010). GSK3 signalling in neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 539–551. doi: 10.1038/nrn2870

Jacques, B. E., Puligilla, C., Weichert, R. M., Ferrer-Vaquer, A., Hadjantonakis, A.-K., Kelley, M. W., et al. (2012). A dual function for canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the developing mammalian cochlea. Development 139, 4395. doi: 10.1242/dev.080358

Jagger, D., Collin, G., Kelly, J., Towers, E., Nevill, G., Longo-Guess, C., et al. (2011). Alstrom syndrome protein ALMS1 localizes to basal bodies of cochlear hair cells and regulates cilium-dependent planar cell polarity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 466–481. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq493

Kirjavainen, A., Laos, M., Anttonen, T., and Pirvola, U. (2015). The Rho GTPase Cdc42 regulates hair cell planar polarity and cellular patterning in the developing cochlea. Biol. Open. 4, 516–526. doi: 10.1242/bio.20149753

Komiya, Y., and Habas, R. (2008). Wnt signal transduction pathways. Organogenesis 4, 68–75. doi: 10.4161/org.4.2.5851

Landin Malt, A., Dailey, Z., Holbrook-Rasmussen, J., Zheng, Y., Hogan, A., Du, Q., et al. (2019). Par3 is essential for the establishment of planar cell polarity of inner ear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4999–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816333116

Landin Malt, A., Hogan, A. K., Smith, C. D., Madani, M. S., and Lu, X. (2020). Wnts regulate planar cell polarity via heterotrimeric G protein and PI3K signaling. J. Cell Biol. 219:e201912071.

Lefevre, G., Michel, V., Weil, D., Lepelletier, L., Bizard, E., Wolfrum, U., et al. (2008). A core cochlear phenotype in USH1 mouse mutants implicates fibrous links of the hair bundle in its cohesion, orientation and differential growth. Development 135, 1427–1437. doi: 10.1242/dev.012922

Mao, Y., Mulvaney, J., Zakaria, S., Yu, T., Morgan, K. M., Allen, S., et al. (2011). Characterization of a ⁢em>Dchs1⁢/em> mutant mouse reveals requirements for Dchs1-Fat4 signaling during mammalian development. Development 138:947.

Matis, M., Russler-Germain, D. A., Hu, Q., Tomlin, C. J., and Axelrod, J. D. (2014). Microtubules provide directional information for core PCP function. Elife 3:e02893.

Metcalfe, C., and Bienz, M. (2011). Inhibition of GSK3 by Wnt signalling–two contrasting models. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3537–3544. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091991

Montcouquiol, M., and Kelley, M. W. (2019). Development and patterning of the cochlea: from convergent extension to planar polarity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 10:a033266. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033266

Morgan-Smith, M., Wu, Y., Zhu, X., Pringle, J., and Snider, W. D. (2014). GSK-3 signaling in developing cortical neurons is essential for radial migration and dendritic orientation. Elife 3:e02663.

Najarro, E. H., Huang, J., Jacobo, A., Quiruz, L. A., Grillet, N., and Cheng, A. G. (2020). Dual regulation of planar polarization by secreted Wnts and Vangl2 in the developing mouse cochlea. Development 147:dev191981. doi: 10.1242/dev.191981

Ono, K., Kita, T., Sato, S., O’Neill, P., Mak, S.-S., Paschaki, M., et al. (2014). FGFR1-Frs2/3 signalling maintains sensory progenitors during inner ear hair cell formation. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004118

Patel, S., Doble, B. W., MacAulay, K., Sinclair, E. M., Drucker, D. J., and Woodgett, J. R. (2008). Tissue-specific role of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in glucose homeostasis and insulin action. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6314–6328. doi: 10.1128/mcb.00763-08

Reis, C. R., Chen, P. H., Srinivasan, S., Aguet, F., Mettlen, M., and Schmid, S. L. (2015). Crosstalk between Akt/GSK3beta signaling and dynamin-1 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. EMBO J. 34, 2132–2146. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591518

Roberts, M. S., Woods, A. J., Dale, T. C., van der Sluijs, P., and Norman, J. C. (2004). Protein kinase B/Akt acts via glycogen synthase kinase 3 to regulate recycling of αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.24.4.1505-1515.2004

Sato, A., Yamamoto, H., Sakane, H., Koyama, H., and Kikuchi, A. (2010). Wnt5a regulates distinct signalling pathways by binding to Frizzled2. EMBO J. 29, 41–54. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.322

Siletti, K., Tarchini, B., and Hudspeth, A. J. (2017). Daple coordinates organ-wide and cell-intrinsic polarity to pattern inner-ear hair bundles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E11170–E11179.

Sipe, C. W., Liu, L., Lee, J., Grimsley-Myers, C., and Lu, X. (2013). Lis1 mediates planar polarity of auditory hair cells through regulation of microtubule organization. Development 140, 1785–1795. doi: 10.1242/dev.089763

Sipe, C. W., and Lu, X. (2011). Kif3a regulates planar polarization of auditory hair cells through both ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Development 138, 3441–3449. doi: 10.1242/dev.065961

Srinivasan, L., Sasaki, Y., Calado, D. P., Zhang, B., Paik, J. H., and DePinho, R. A. (2009). PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell 139, 573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041

Tarchini, B., and Lu, X. (2019). New insights into regulation and function of planar polarity in the inner ear. Neurosci. Lett. 709:134373. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134373

Vladar, E. K., Bayly, R. D., Sangoram, A. M., Scott, M. P., and Axelrod, J. D. (2012). Microtubules enable the planar cell polarity of airway cilia. Curr. Biol. 22, 2203–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.046

Voloshanenko, O., Gmach, P., Winter, J., Kranz, D., and Boutros, M. (2017). Mapping of Wnt-Frizzled interactions by multiplex CRISPR targeting of receptor gene families. FASEB J. 31, 4832–4844. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700144r

Wang, Y., Guo, N., and Nathans, J. (2006). The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 26, 2147–2156. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4698-05.2005

Wiese, K. E., Nusse, R., and van Amerongen, R. (2018). Wnt signalling: conquering complexity. Development 145:dev165902. doi: 10.1242/dev.165902

Yu, H., Ye, X., Guo, N., and Nathans, J. (2012). Frizzled 2 and frizzled 7 function redundantly in convergent extension and closure of the ventricular septum and palate: evidence for a network of interacting genes. Development 139, 4383–4394. doi: 10.1242/dev.083352

Keywords: non-canonical Wnt, Gsk3β, Rac1, planar cell polarity, hair bundle, kinocilium, cochlea

Citation: Landin Malt A, Clancy S, Hwang D, Liu A, Smith C, Smith M, Hatley M, Clemens C and Lu X (2021) Non-Canonical Wnt Signaling Regulates Cochlear Outgrowth and Planar Cell Polarity via Gsk3β Inhibition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:649830. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.649830

Received: 05 January 2021; Accepted: 17 March 2021;

Published: 16 April 2021.

Edited by:

Zhigang Xu, Shandong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mireille Montcouquiol, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), FranceCopyright © 2021 Landin Malt, Clancy, Hwang, Liu, Smith, Smith, Hatley, Clemens and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaowei Lu, eGw2ZkB2aXJnaW5pYS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.