- 1Department of Medical Genetics, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Tissue Engineering and Applied Cell Sciences, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3Urology and Nephrology Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

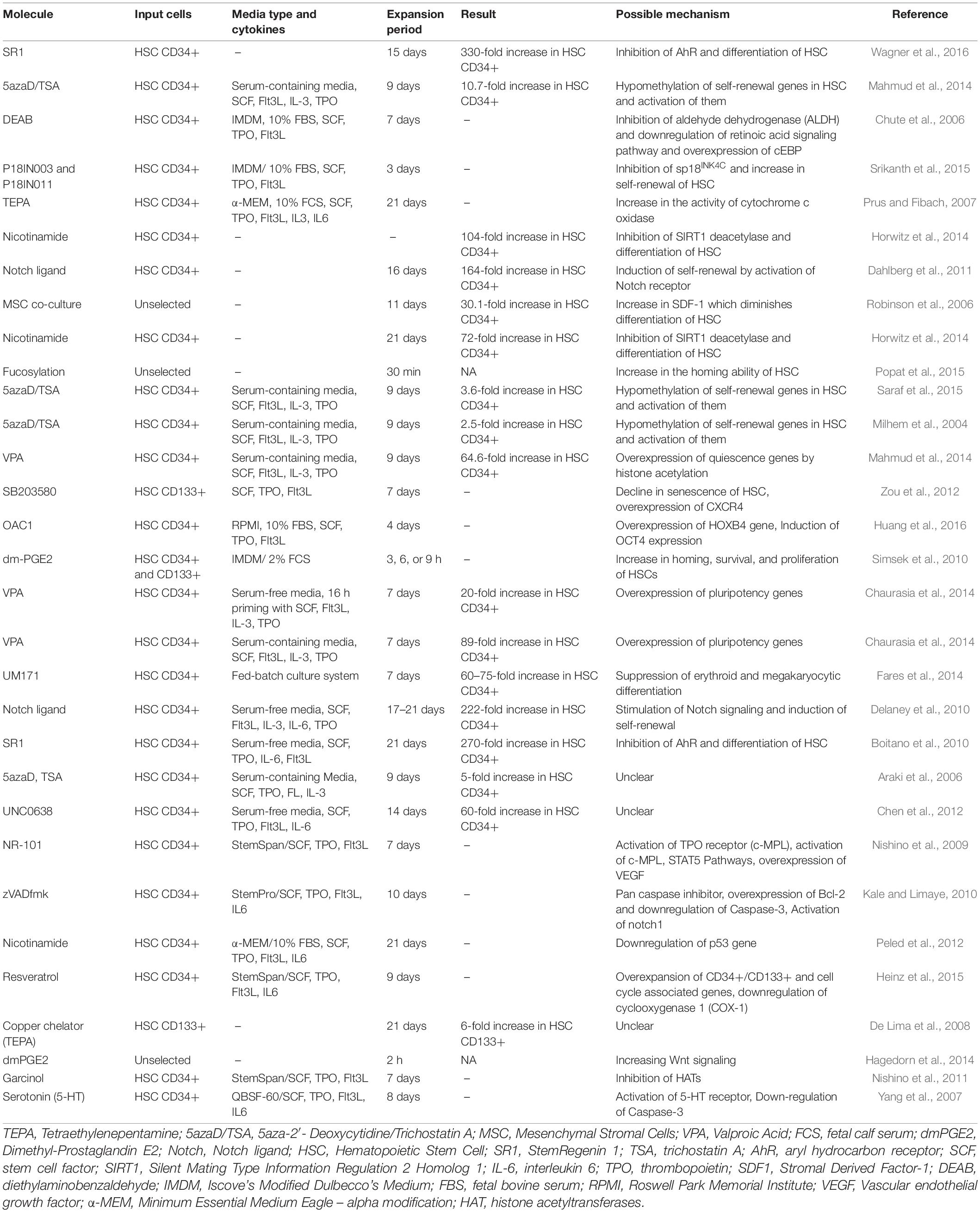

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are a group of cells being produced during embryogenesis to preserve the blood system. They might also be differentiated to non-hematopoietic cells, including neural, cardiac and myogenic cells. Therefore, they have vast applications in the treatment of human disorders. Considering the restricted quantities of HSCs in the umbilical cord blood, inadequate mobilization of bone marrow stem cells, and absence of ethnic dissimilarity, ex vivo expansion of these HSCs is an applicable method for obtaining adequate amounts of HSCs. Several molecules such as NR-101, zVADfmk, zLLYfmk, Nicotinamide, Resveratrol, the Copper chelator TEPA, dmPGE2, Garcinol, and serotonin have been used in combination of cytokines to expand HSCs ex vivo. The most promising results have been obtained from cocktails that influence multipotency and self-renewal features from different pathways. In the current manuscript, we provide a concise summary of the effects of diverse small molecules on expansion of cord blood HSCs.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are a group of cells being produced during embryogenesis to preserve the blood system. Unlike to progenitor cells, these cells have both self-renewal and multipotency. Therefore, HSCs have important applications in the hematopoietic stem cell transplantations (HSCT) and regenerative medicine (Tajer et al., 2019). However, HSCs constitute a minor population of bone marrow cells even less than 0.01% of these cells (Walasek et al., 2012). The fast accessibility and lower need for immune-matching have potentiated the umbilical cord blood as an important source of HSCs for transplantation (Chou et al., 2010). Considering the restricted quantities of HSCs in the umbilical cord blood and inadequate mobilization of bone marrow stem cells (Daniel et al., 2016), ex vivo expansion of these HSCs represents an applicable method for obtaining substantial quantities of HSCs. Several strategies have been used to expand these cells among them is addition of several cytokines to the culture media. Yet, this method did not lead to adequate and long lasting expansions (Zhang and Lodish, 2008). Lack of sustained self-renewal and induction of differentiation in HSCs obtained from these protocols (Seita and Weissman, 2010) have restricted the application of these methods. However, more recent studies have attained promising results using hematopoietic expansion medium, comprising cytokines and nutritional complements (Zhang et al., 2019). Other modalities for ex vivo expansion of HSCs include co-culture with stromal cells (McNiece et al., 2004), forced over-expression of specific genes (Walasek et al., 2012), and using recombinant proteins for modulation of developmental pathways (Krosl et al., 2003). Besides, lentivirus vectors have been used to deliver a number of genes to enhance engraftment of short term repopulating HSCs (Abraham et al., 2016). Numerous small-sized chemical agents have also been used for such purpose (De Lima et al., 2008; Nishino et al., 2009; Peled et al., 2012). In the current manuscript, we provide a concise summary of the effects of diverse small molecules on expansion of cord blood HSCs.

StemRegenin-1 (SR-1)

StemRegenin–1 has been shown to enhance expansion of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors through antagonizing aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Boitano et al., 2010). Co-culture of HSCs with SR-1 and several other factors such as stem cell factor (SCF), FLT-3L, TPO, and IL-6 has resulted to expansion of larger quantities of CD34+ cells (Wagner et al., 2016). In a clinical trial conducted by Wagner et al. (2016) SR–1 has resulted in a 330-fold expansion of CD34+ cells resulting in fast engraftment of neutrophils and platelets in all of assessed patients. According to remarkable effect of this substance on HSCs expansion, non-existence of graft failure and high hematopoietic recovery, SR-1 has been suggested as a solitary agent for HSCT for defeating the major problem of umbilical cord blood transplantation (Wagner et al., 2016).

Epigenetic Modifiers

Mahmud et al. (2014) have assessed expansion of HSCs when exposed to histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors valproic acid (VPA) and trichostatin A (TSA). These cells were exposed to these agents alone or along with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5azaD). Their experiment showed the superior effects of VPA on expansion of CD34+CD90+ cells and progenitor cells. In vivo studies verified the impacts of VPA on prevention of HSC defects. Besides, combination of 5azaD and TSA resulted in expansion of HSCs that preserve their features through serial transplantation. Expression analysis revealed differential expression of genes participating in the expansion and maintenance of HSCs in 5azaD/TSA- and VPA-treated cells, respectively. Overexpression of quiescence genes by histone acetylation has been suggested as the underlying mechanism of these observations (Mahmud et al., 2014). Saraf et al. (2015) have assess the effects of sequential treatment of CD34+ mobilized human peripheral blood (MPB) with 5azaD and TSA in accompany with cytokines. They observed significant expansion of CD34+CD90+ cells in 5azaD/TSA-treated cells. They also detected over-expression of genes participating in self-renewal in these cells. Such over-expression was accompanied by global hypomethylation (Saraf et al., 2015). Milhem et al. (2004) have treated human bone marrow CD34+ cells with a cytokine cocktail, 5azaD, and TSA. They observed remarkable expansion of a group of these cells. Notably, 5azaD- and TSA-pre-exposed cells but not those treated with cytokines alone preserved the capacity to repopulate NOD mice (Milhem et al., 2004). After a period of cytokine priming, VPA-exposed CD34+ cells have produced CD34+CD90+ multipotent cells. Co-culture of CD34+ cells with combination of cytokines and VPA has resulted in a more remarkable expansion of these cells. Such exposure has led to enhancement of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, and over-expression of a number of cell surface proteins namely CD90, CD117, CD49f, and CD184. Treatment of CD34+ cells with VPA has led to production of higher quantities of repopulating cells in the immune deficient mice (Chaurasia et al., 2014).

Nicotinamide

As a suppressor of SIRT1, Nicotinamide has been shown to preclude differentiation and enhance expansion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) (Peled et al., 2012). Horwitz et al. (2014) have used an ex vivo–expanded cell product that contains nicotinamide (NiCord) in a phase I clinical trial. They reported total or fractional neutrophil and T cell engraftment in most of patients. Moreover, they reported stability of NiCord engraftment in all individual during the follow-up period. Median neutrophil recovery was faster in individuals transplanted with NiCord (Horwitz et al., 2014).

Serotonin

The neurotransmitter serotonin has various extraneuronal roles. This substance has been shown to induce megakaryocytopoiesis through 5−HT2 receptors (Yang et al., 1996). In addition, serotonin promotes expansion of CD34+ cells to early stem/progenitors and multilineage committed progenitors. The effects of this agents on repopulating cells in the expansion culture has also been verified in SCID mice suggesting the impact of serotonin in the development of HSCs and modulation of bone marrow niche (Yang et al., 2007).

Table 1 summarizes the results of studies which assessed the effects of small molecules on ex vivo expansion of cord blood hematopoietic stem cells.

Discussion

Ex vivo expansion of HSCs obtained from umbilical cord blood has become a major research field because of its application in the treatment of several hematological disorders (Flores-Guzmán et al., 2013). This process is expected to mimic the normal bone marrow niche which is consisted of stromal cells and their produced materials. Thus, nearly all expansion protocols contain early- and late-acting cytokines to enhance growth of hematopoietic cells. Moreover, various kinds of stromal cells such as primary MSCs can improve the efficiency of expansion. Several promising results have been obtained from these experiments leading to design of nearly optimal protocols. Different combinations of cytokines can promote commitment of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) from certain lineages, i.e., erythroid or myeloid ones. Thus, selection of appropriate cytokines is important in reaching the optimal yield. The possibility of differentiation of HSCs to non-hematopoietic cells, including neural, cardiac and myogenic cells have expanded their applications in the treatment of human disorders (Flores-Guzmán et al., 2013). Moreover, expanded HSC have been used in clinical trials to inhibit Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following HSCT. Examples of these clinical trials are those conducted by Nohla Therapeutics1 and exciting trials by ExCellThera2. The latter has received Food and Drug Administration orphan drug designation for ECT-001. ECT-001 comprises a small molecule, UM171, and an adjusted culture method for expansion of HSC. The primary results of this trial have been promising in reduction of risk of GVHD3.

Small molecules represent novel modalities for ex vivo expansion of cord blood HSCs. These molecules have also been used for the purpose of expansion of HSPCs with primitive phenotype. Screening of a patented library containing tens of small molecules has shown the necessity of including SCF, thrombopoietin and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand in the cocktail for enhancing expansion of these cells in addition to C7. Moreover, adding insulin like growth factor binding protein 2 to the cocktail slightly increased expansion (Bari et al., 2016).

The efficacy of these molecules is different in various aspects of HSCT. For instance, SR-1, Notch-ligand and nicotinamide-based methods has been associated with fast neutrophil recovery (Delaney et al., 2010; Horwitz et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2016). Epigenetic modifiers such as VPA are among the mostly assessed agents in ex vivo expansion studies. Such agents increase expression of multipotency and self-renewal genes mainly through global modifications in epigenetic marks.

Small molecules exert their effects through different routes including induction of expression of pluripotency genes, modulation of methylation pattern of self-renewal genes and regulation of retinoic acid, Wnt, and Notch signaling pathways. Inhibition of apoptosis is another putative mechanism of participation of small molecules in ex vivo expansion of HSCs, as the caspase and calpain inhibitors have been proved to be effective in this regard (Kale and Limaye, 2010). Such strategy has been proved to be effective in enhancement of efficacy of transplantation in animal models, since temporary up-regulation of prosurvival BCL-XL as considerably promoted survival and engraftment of HSCs and progenitor cells (Kollek et al., 2017). In some cases, the exact molecular mechanism of their impacts on HSCs is not clear. Identification of such mechanisms would facilitate design of optimal protocols and avoidance of possible side-effects of associated therapies.

As a rule, strong expansion of HSPCs with sustaining engraftment requires the synergistic functions of several enhancers of HSC expansion (Pineault and Abu-Khader, 2015). This fact has been reflected in better therapeutic results and enhanced engraftment in clinical trials that used the synergistic effects of cytokines and HSPC expansion enhancers (Pineault and Abu-Khader, 2015). Therefore, application of combination of small molecules and cytokines is a suggested strategy for expansion of HSCs and inhibition of their differentiation (Wang et al., 2017). The underlying mechanism of such observations might be the effect of small molecules in modulation of regulatory roles of cytokines on signaling pathways. The results of in vitro studies have been verified in a number of experiments using irradiated NOD/SCID mice (Eldjerou et al., 2010; Budak-Alpdogan et al., 2012). These types of studies would help in the evaluation of cell viability and engraftment capacity in vivo. Functional consequences of HSC expansion strategies in the clinical settings have been assessed through different methods. The time to neutrophil or platelet engraftments, enhancement of patients’ survival, occurrence of GVHD, infectious conditions, or relapse rates are among parameters which have been recognized as clinically relevant parameters in this regard (Kiernan et al., 2017). The most important parameter seems to be patients’ survival. It is worth mentioning that in spite of important developments in ex vivo expansion of HSCs, the capability to follow HSC fate decisions within the bone marrow microenvironment is inadequate (Papa et al., 2020).

Another application of small-molecules-induced expansion of HSCs is that transcriptome analysis of these cells can facilitate identification of the crucial pathways and molecules of HSC self-renewal, thus providing novel target molecules for in vitro expansion of these cells (Zhang et al., 2020).

Taken together, several molecules such as SR-1, NR-101, the caspases inhibitor zVADfmk, the calpain inhibitor zLLYfmk, Nicotinamide, Resveratrol, the Copper chelator TEPA, dmPGE2, Garcinol, and serotonin have been used in combination of cytokines to expand HSCs ex vivo. The most promising results have been obtained from cocktails that influence multipotency and self-renewal features from different pathways. These cocktails include several growth factors, molecules that regulate signaling pathways and vectors that manipulate expression of genes. Putative target genes in this regard are HOX genes and cell cycle associated genes as well as those participating in Wnt, Notch, and Shh pathways. Each constituent of these cocktails might affect some aspects of multipotency and self-renewal, constructing a synergic system to yield the best results. These elements should enhance self-renewal, suspend differentiation, promote homing, and suppress apoptosis of HSCs (Zhang and Gao, 2016). Precise assessment of the expansion aptitude of cell populations through quantification of the generated cells using immunophenotypic methods or functional assessments is an important requirement of comparison studies for identification of best ex vivo expansion methods. Aptitude of expansion and preservation of multipotent HPCs can be precisely assessed by the numbers of lineage specific colony-forming units and colony-forming unit mix and Human Long-Term Culture-Initiating Cell (LTC-IC) activity (Ali et al., 2014). Concomitant conduction of these methods is crucial for identification the expanded lineage in each experimental condition.

As different methods have been used for such quantifications, it is not easy to precisely compare the results of different studies. Most mentioned studies has used CD34+ HSCs as input cell population. Yet, a number of studies lave used unselected cell populations which complicate the comparison studies due to different extents of enrichment for primitive cells.

Considering the complexity of natural HSC milieu and existence of a wide range of cells and their produced molecules in addition to secreted cytokines, application of multifaceted strategies seems to yield more promising results. Examples of such strategies are co-culture of stromal cells with other niche components including extracellular matrix proteins (Deutsch et al., 2010; Celebi et al., 2011) or Sonic hedgehog (Bhardwaj et al., 2001) and induction of expression of genes which promote self-renewal (Watts et al., 2010; Aguila et al., 2011).

Finally, documentation of expansion of actual HSCs rather than HPCs is an important prerequisite of clinical applications although both cell population have their own clinical uses. Such important step has been missed in some early studies in this field.

Author Contributions

MT and SG-F wrote the draft of the manuscript and revised it. AB and VN designed the tables and collected the data. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01690520

- ^ https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04103879

- ^ https://www.insidertracking.com/excellthera-receives-fda-orphan-drug-designation-for-ect-001-for-the-prevention-of-graft-versus-host-disease

References

Abraham, A., Kim, Y.-S., Zhao, H., Humphries, K., and Persons, D. A. (2016). Increased engraftment of human short term repopulating hematopoietic Cells in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice by lentiviral expression of NUP98-HOXA10HD. PLoS One 11:e0147059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147059

Aguila, J. R., Liao, W., Yang, J., Avila, C., Hagag, N., Senzel, L., et al. (2011). SALL4 is a robust stimulator for the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 118, 576–585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333641

Ali, I., Jiao, W., Wang, Y., Masood, S., Yousaf, M. Z., Javaid, A., et al. (2014). Ex vivo expansion of functional human UCB-HSCs/HPCs by coculture with AFT024-hkirre cells. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014:412075.

Araki, H., Mahmud, N., Milhem, M., Nunez, R., Xu, M., Beam, C. A., et al. (2006). Expansion of human umbilical cord blood SCID-repopulating cells using chromatin-modifying agents. Exp. Hematol. 34, 140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.10.002

Bari, S., Zhong, Q., Chai, C. L., Chiu, G. N., and Hwang, W. Y. (2016). Small Molecule Based Ex Vivo Expansion of CD34+ CD90+ CD49f+ Hematopoietic Stem & Progenitor Cells from Non-Enriched Umbilical Cord Blood Mononucleated Cells. Blood 128, 2321. doi: 10.1182/blood.v128.22.2321.2321

Bhardwaj, G., Murdoch, B., Wu, D., Baker, D. P., Williams, K. P., Chadwick, K., et al. (2001). Sonic hedgehog induces the proliferation of primitive human hematopoietic cells via BMP regulation. Nat. Immunol. 2, 172–180. doi: 10.1038/84282

Boitano, A. E., Wang, J., Romeo, R., Bouchez, L. C., Parker, A. E., Sutton, S. E., et al. (2010). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science 329, 1345–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1191536

Budak-Alpdogan, T., Jeganathan, G., Lee, K. C., Mrowiec, Z. R., Medina, D. J., Todd, D., et al. (2012). Irradiated allogeneic cells enhance umbilical cord blood stem cell engraftment in immunodeficient mice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 1569–1576. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.69

Celebi, B., Mantovani, D., and Pineault, N. (2011). Effects of extracellular matrix proteins on the growth of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Biomed. Mater. 6:055011. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/6/5/055011

Chaurasia, P., Gajzer, D. C., Schaniel, C., D’Souza, S., and Hoffman, R. (2014). Epigenetic reprogramming induces the expansion of cord blood stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2378–2395. doi: 10.1172/jci70313

Chen, X., Skutt-Kakaria, K., Davison, J., Ou, Y.-L., Choi, E., Malik, P., et al. (2012). G9a/GLP-dependent histone H3K9me2 patterning during human hematopoietic stem cell lineage commitment. Genes Dev. 26, 2499–2511.

Chou, S., Chu, P., Hwang, W., and Lodish, H. (2010). Expansion of human cord blood hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation. Cell Stem Cell 7, 427–428. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.09.001

Chute, J. P., Muramoto, G. G., Whitesides, J., Colvin, M., Safi, R., Chao, N. J., et al. (2006). Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase and retinoid signaling induces the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 103, 11707–11712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603806103

Dahlberg, A., Delaney, C., and Bernstein, I. D. (2011). Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 117, 6083–6090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-283606

Daniel, M. G., Pereira, C.-F., Lemischka, I. R., and Moore, K. A. (2016). Making a hematopoietic stem cell. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 202–214.

De Lima, M., McMannis, J., Gee, A., Komanduri, K., Couriel, D., Andersson, B. S., et al. (2008). Transplantation of ex vivo expanded cord blood cells using the copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine: a phase I/II clinical trial. Bone Marrow Transp. 41, 771–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705979

Delaney, C., Heimfeld, S., Brashem-Stein, C., Voorhies, H., Manger, R. L., and Bernstein, I. D. (2010). Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat. Med. 16, 232–236.

Deutsch, V., Hubel, E., Kay, S., Ohayon, T., Katz, B. Z., Many, A., et al. (2010). Mimicking the haematopoietic niche microenvironment provides a novel strategy for expansion of haematopoietic and megakaryocyte-progenitor cells from cord blood. Br. J. Haematol. 149, 137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08041.x

Eldjerou, L. K., Chaudhury, S., Baisre-de Leon, A., He, M., Arcila, M. E., Heller, G., et al. (2010). An in vivo model of double-unit cord blood transplantation that correlates with clinical engraftment. Blood 116, 3999–4006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276212

Fares, I., Chagraoui, J., Gareau, Y., Gingras, S., Ruel, R., Mayotte, N., et al. (2014). Pyrimidoindole derivatives are agonists of human hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Science 345, 1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1256337

Flores-Guzmán, P., Fernández-Sánchez, V., and Mayani, H. (2013). Concise review: ex vivo expansion of cord blood-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: basic principles, experimental approaches, and impact in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2, 830–838. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0071

Hagedorn, E. J., Durand, E. M., Fast, E. M., and Zon, L. I. (2014). Getting more for your marrow: boosting hematopoietic stem cell numbers with PGE2. Exp. cell Res. 329, 220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.030

Heinz, N., Ehrnström, B., Schambach, A., Schwarzer, A., Modlich, U., and Schiedlmeier, B. (2015). Comparison of different cytokine conditions reveals resveratrol as a new molecule for ex vivo cultivation of cord blood-derived hematopoietic stem cells. Stem cells Trans. Med. 4, 1064–1072. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0284

Horwitz, M. E., Chao, N. J., Rizzieri, D. A., Long, G. D., Sullivan, K. M., Gasparetto, C., et al. (2014). Umbilical cord blood expansion with nicotinamide provides long-term multilineage engraftment. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3121–3128. doi: 10.1172/jci74556

Huang, X., Lee, M.-R., Cooper, S., Hangoc, G., Hong, K.-S., Chung, H.-M., et al. (2016). Activation of OCT4 enhances ex vivo expansion of human cord blood hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by regulating HOXB4 expression. Leukemia 30, 144–153. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.189

Kale, V. P., and Limaye, L. S. (2010). Expansion of cord blood CD34+ cells in presence of zVADfmk and zLLYfmk improved their in vitro functionality and in vivo engraftment in NOD/SCID mouse. PLoS One 5:e12221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012221

Kiernan, J., Damien, P., Monaghan, M., Shorr, R., McIntyre, L., Fergusson, D., et al. (2017). Clinical studies of ex vivo expansion to accelerate engraftment after umbilical cord blood transplantation: a systematic review. Transfusion Med. Rev. 31, 173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2016.12.004

Kollek, M., Voigt, G., Molnar, C., Murad, F., Bertele, D., Krombholz, C. F., et al. (2017). Transient apoptosis inhibition in donor stem cells improves hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2967–2983. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161721

Krosl, J., Austin, P., Beslu, N., Kroon, E., Humphries, R. K., and Sauvageau, G. (2003). In vitro expansion of hematopoietic stem cells by recombinant TAT-HOXB4 protein. Nat. Med. 9, 1428–1432. doi: 10.1038/nm951

Mahmud, N., Petro, B., Baluchamy, S., Li, X., Taioli, S., Lavelle, D., et al. (2014). Differential effects of epigenetic modifiers on the expansion and maintenance of human cord blood stem/progenitor cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transp. 20, 480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.12.562

McNiece, I., Harrington, J., Turney, J., Kellner, J., and Shpall, E. J. (2004). Ex vivo expansion of cord blood mononuclear cells on mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 6, 311–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240410004871

Milhem, M., Mahmud, N., Lavelle, D., Araki, H., DeSimone, J., Saunthararajah, Y., et al. (2004). Modification of hematopoietic stem cell fate by 5aza 2’ deoxycytidine and trichostatin A. Blood 103, 4102–4110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2431

Nishino, T., Miyaji, K., Ishiwata, N., Arai, K., Yui, M., Asai, Y., et al. (2009). Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells by a small-molecule agonist of c-MPL. Exp Hematol. 37, 1364–77.e4.

Nishino, T., Wang, C., Mochizuki-Kashio, M., Osawa, M., Nakauchi, H., and Iwama, A. (2011). Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells by garcinol, a potent inhibitor of histone acetyltransferase. PLoS One 6:e24298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024298

Papa, L., Djedaini, M., and Hoffman, R. (2020). Ex vivo HSC expansion challenges the paradigm of unidirectional human hematopoiesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 1466:39. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14133

Peled, T., Shoham, H., Aschengrau, D., Yackoubov, D., Frei, G., Rosenheimer, G. N., et al. (2012). Nicotinamide, a SIRT1 inhibitor, inhibits differentiation and facilitates expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells with enhanced bone marrow homing and engraftment. Exp Hematol. 40, 342–55.e1.

Pineault, N., and Abu-Khader, A. (2015). Advances in umbilical cord blood stem cell expansion and clinical translation. Exp. Hematol. 43, 498–513. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.04.011

Popat, U., Mehta, R. S., Rezvani, K., Fox, P., Kondo, K., Marin, D., et al. (2015). Enforced fucosylation of cord blood hematopoietic cells accelerates neutrophil and platelet engraftment after transplantation. Blood 125, 2885–2892.

Prus, E., and Fibach, E. (2007). The effect of the copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine on reactive oxygen species generation by human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 16, 1053–1056. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0052

Robinson, S., Ng, J., Niu, T., Yang, H., McMannis, J., Karandish, S., et al. (2006). Superior ex vivo cord blood expansion following co-culture with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Transp. 37, 359–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705258

Saraf, S., Araki, H., Petro, B., Park, Y., Taioli, S., Yoshinaga, K. G., et al. (2015). Ex vivo expansion of human mobilized peripheral blood stem cells using epigenetic modifiers. Transfusion 55, 864–874. doi: 10.1111/trf.12904

Seita, J., and Weissman, I. L. (2010). Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2, 640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86

Simsek, T., Kocabas, F., Zheng, J., DeBerardinis, R. J., Mahmoud, A. I., Olson, E. N., et al. (2010). The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell stem cell 7, 380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.011

Srikanth, L., Sunitha, M. M., Venkatesh, K., Kumar, P. S., Chandrasekhar, C., Vengamma, B., et al. (2015). Anaerobic glycolysis and HIF1 [alpha] expression in haematopoietic stem cells explains its quiescence nature. J. Stem Cells 10:97.

Tajer, P., Pike-Overzet, K., Arias, S., Havenga, M., and Staal, F. J. T. (2019). Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells for therapeutic purposes: lessons from development and the niche. Cells 8:169. doi: 10.3390/cells8020169

Wagner, J. E. Jr., Brunstein, C. G., Boitano, A. E., DeFor, T. E., McKenna, D., Sumstad, D., et al. (2016). Phase I/II trial of StemRegenin-1 expanded umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells supports testing as a stand-alone graft. Cell stem cell 18, 144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.004

Walasek, M. A., van Os, R., and de Haan, G. (2012). Hematopoietic stem cell expansion: challenges and opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1266, 138–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06549.x

Wang, L., Guan, X., Wang, H., Shen, B., Zhang, Y., Ren, Z., et al. (2017). A small-molecule/cytokine combination enhances hematopoietic stem cell proliferation via inhibition of cell differentiation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8:169.

Watts, K. L., Delaney, C., Humphries, R. K., Bernstein, I. D., and Kiem, H. P. (2010). Combination of HOXB4 and Delta-1 ligand improves expansion of cord blood cells. Blood 116, 5859–5866. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286062

Yang, M., Li, K., Ng, P. C., Chuen, C. K. Y., Lau, T. K., Cheng, Y. S., et al. (2007). Promoting effects of serotonin on hematopoiesis: ex vivo expansion of cord blood CD34+ stem/progenitor cells, proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells, and antiapoptosis. Stem Cells 25, 1800–1806. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0048

Yang, M., Srikiatkhachorn, A., Anthony, M., and Chong, B. H. (1996). Serotonin stimulates megakaryocytopoiesis via the 5-HT2 receptor. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis Int. J. Haemost. Thromb. 7, 127–133. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199603000-00004

Zhang, B., Wen, R., Dong, C., Zhao, L., and Yang, Y. (2020). A small-molecule combination promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood-derived hematopoietic stem cells. Cytotherapy 22:S65.

Zhang, C. C., and Lodish, H. F. (2008). Cytokines regulating hematopoietic stem cell function. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15:307. doi: 10.1097/moh.0b013e3283007db5

Zhang, Y., and Gao, Y. (2016). Novel chemical attempts at ex vivo hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Int. J. Hematol. 103, 519–529. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-1962-x

Zhang, Y., Shen, B., Guan, X., Qin, M., Ren, Z., Ma, Y., et al. (2019). Safety and efficacy of ex vivo expanded CD34+ stem cells in murine and primate models. Stem cell Res. Ther. 10:173.

Keywords: small molecules, ex vivo expansion, hematopoietic stem cell, expression, mesenchymal stromal cells

Citation: Ghafouri-Fard S, Niazi V, Taheri M and Basiri A (2021) Effect of Small Molecule on ex vivo Expansion of Cord Blood Hematopoietic Stem Cells: A Concise Review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:649115. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.649115

Received: 03 January 2021; Accepted: 22 March 2021;

Published: 09 April 2021.

Edited by:

Hiroki Shibata, Kyushu University, JapanReviewed by:

Bradley Wayne Doble, University of Manitoba, CanadaWilairat Leeanansaksiri, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Copyright © 2021 Ghafouri-Fard, Niazi, Taheri and Basiri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Taheri, bW9oYW1tYWRfODIzQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Abbas Basiri, YmFzaXJpQHVucmMuaXI=

Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard

Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard Vahid Niazi2

Vahid Niazi2 Mohammad Taheri

Mohammad Taheri