94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol., 11 March 2021

Sec. Molecular and Cellular Pathology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.629326

This article is part of the Research TopicZebrafish Models for Human Disease StudiesView all 36 articles

Thalidomide, a sedative drug that was once excluded from the market owing to its teratogenic properties, was later found to be effective in treating multiple myeloma. We had previously demonstrated that cereblon (CRBN) is the target of thalidomide embryopathy and acts as a substrate receptor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, Cullin-Ring ligase 4 (CRL4CRBN) in zebrafish and chicks. CRBN was originally identified as a gene responsible for mild intellectual disability in humans. Fetuses exposed to thalidomide in early pregnancy were at risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, suggesting that CRBN is involved in prenatal brain development. Recently, we found that CRBN controls the proliferation of neural stem cells in the developing zebrafish brain, leading to changes in brain size. Our findings imply that CRBN is involved in neural stem cell growth in humans. Accumulating evidence shows that CRBN is essential not only for the teratogenic effects but also for the therapeutic effects of thalidomide. This review summarizes recent progress in thalidomide and CRBN research, focusing on the teratogenic and therapeutic effects. Investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of thalidomide and its derivatives, CRBN E3 ligase modulators (CELMoDs), reveals that these modulators provide CRBN the ability to recognize neosubstrates depending on their structure. Understanding the therapeutic effects leads to the development of a novel technology called CRBN-based proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) for target protein knockdown. These studies raise the possibility that CRBN-based small-molecule compounds regulating the proliferation of neural stem cells may be developed for application in regenerative medicine.

Thalidomide—originally developed as a sedative-hypnotic drug and used worldwide approximately 60 years ago—is an effective antiemetic and prescribed for morning sickness during pregnancy. This drug was withdrawn from the market because newborns showed multiple birth defects when pregnant women consumed the drug during early pregnancy. Thalidomide is associated with a range of teratogenicity, termed thalidomide embryopathy, in the ears, eyes, face, limbs, genitalia, and internal organs, including heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract (Miller and Strömland, 1999; Vargesson, 2015). Thalidomide teratogenicity shows different critical exposure periods during embryogenesis. Previous research indicates that the earliest exposure to thalidomide increases the risk of autism and epilepsy (Strömland et al., 1994; Miller and Strömland, 1999; Miller et al., 2005). Notably, limb malformations in embryos exposed to thalidomide were observed in humans and rabbits but not in rodents, implying that thalidomide teratogenicity is species-specific (Fratta et al., 1965; Schumacher et al., 1968).

We previously identified cereblon (CRBN) as a primary direct target of thalidomide (Ito et al., 2010). CRBN, encoding a 442-amino-acid protein, is identified as a gene responsible for autosomal recessive non-syndromic intellectual disability; a nonsense mutation, p.R419X, generates a truncated CRBN lacking 24 amino acids at the C-terminal owing to the presence of a premature stop codon (Higgins et al., 2004). Another missense mutation in CRBN is also associated with severe intellectual disability and seizures (Sheereen et al., 2017). CRBN serves as a substrate receptor of the Cullin-Ring ligase 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (CRL4CRBN) that recognizes substrates for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (Ito et al., 2010). CRBN is identified as a protein directly interacting with the cytosolic carboxy-terminus of large conductance, Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+ (BK) channel α subunit (Jo et al., 2005). However, the significance of these mutations with respect to intellectual disability and cellular functions of CRBN is still unclear.

Although the mechanisms underlying the sedative function of thalidomide has not been elucidated, thalidomide has been found to have therapeutic effects in the context of erythema nodosum leprosum and multiple myeloma. At present, thalidomide and its derivatives lenalidomide and pomalidomide are repurposed as immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) for blood cancers. Accumulating evidence suggests that thalidomide and IMiDs bind to CRBN, thereby altering substrate recognition depending on the ligand structure and exerting therapeutic effects by degrading different ligand-specific substrates (neosubstrates) (Chamberlain and Cathers, 2019; Ito and Handa, 2020). Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of action of thalidomide and IMiDs promoted the development of a new protein knockdown technique, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), originally developed using another E3 ubiquitin ligase, von Hippel-Lindau (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Pettersson and Crews, 2019).

We demonstrated that thalidomide caused limb defects through CRBN in chicks and zebrafish (Ito et al., 2010; Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019), suggesting that basic molecular mechanisms of limb development involving CRBN are evolutionarily conserved among vertebrates. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is an excellent model organism to investigate molecular genetic and pathogenic mechanisms underlying human diseases that have a developmental origin (Lieschke and Currie, 2007). Each fish lays many eggs, and the transparent small embryos develop externally in a dish, enabling us to easily observe and analyze the effects on development by gene expression, knockdown, knockout, and screening of small-molecule libraries using living whole embryos (Driever et al., 1994; Kaufman et al., 2009; D’Amora and Giordani, 2018). Furthermore, many transgenic lines, mutants, and disease models are currently available for studying neurodevelopmental disorders in zebrafish (Meshalkina et al., 2018; Sakai et al., 2018; Vaz et al., 2019).

In this mini review, we summarize recent advances in our understanding of the teratogenic and therapeutic effects of thalidomide and its derivatives, currently called cereblon E3 ligase modulators (CELMoDs), and describe the potential of CELMoDs for developing small-molecule compounds that regulate neural stem cell (NSC) proliferation and their significance in regenerative medicine.

In human fetal development, 4–15 weeks gestation (3–14 weeks post-conception) is the organogenesis period; especially, 4–9 weeks gestation (3–8 weeks post-conception) is critical for organogenesis. Human embryos in the first 8 weeks are highly sensitive to teratogens (Wilson, 1973; Hill, 2007). The earliest exposure to thalidomide (20–24 days post-fertilization) has been reported to increase the risk of autism and epilepsy (Strömland et al., 1994; Miller and Strömland, 1999; Miller et al., 2005). Brain development initially begins with the induction of neuroectoderm from ectoderm during gastrulation. This neural induction occurs 3 weeks post-fertilization in humans, roughly corresponding to the critical period for autism elicited by thalidomide exposure (Strömland et al., 1994; Miller and Strömland, 1999; Miller et al., 2005). This suggests that thalidomide has the potential to affect early brain development when neuroectodermal cells, including NSCs, dramatically proliferate and differentiate.

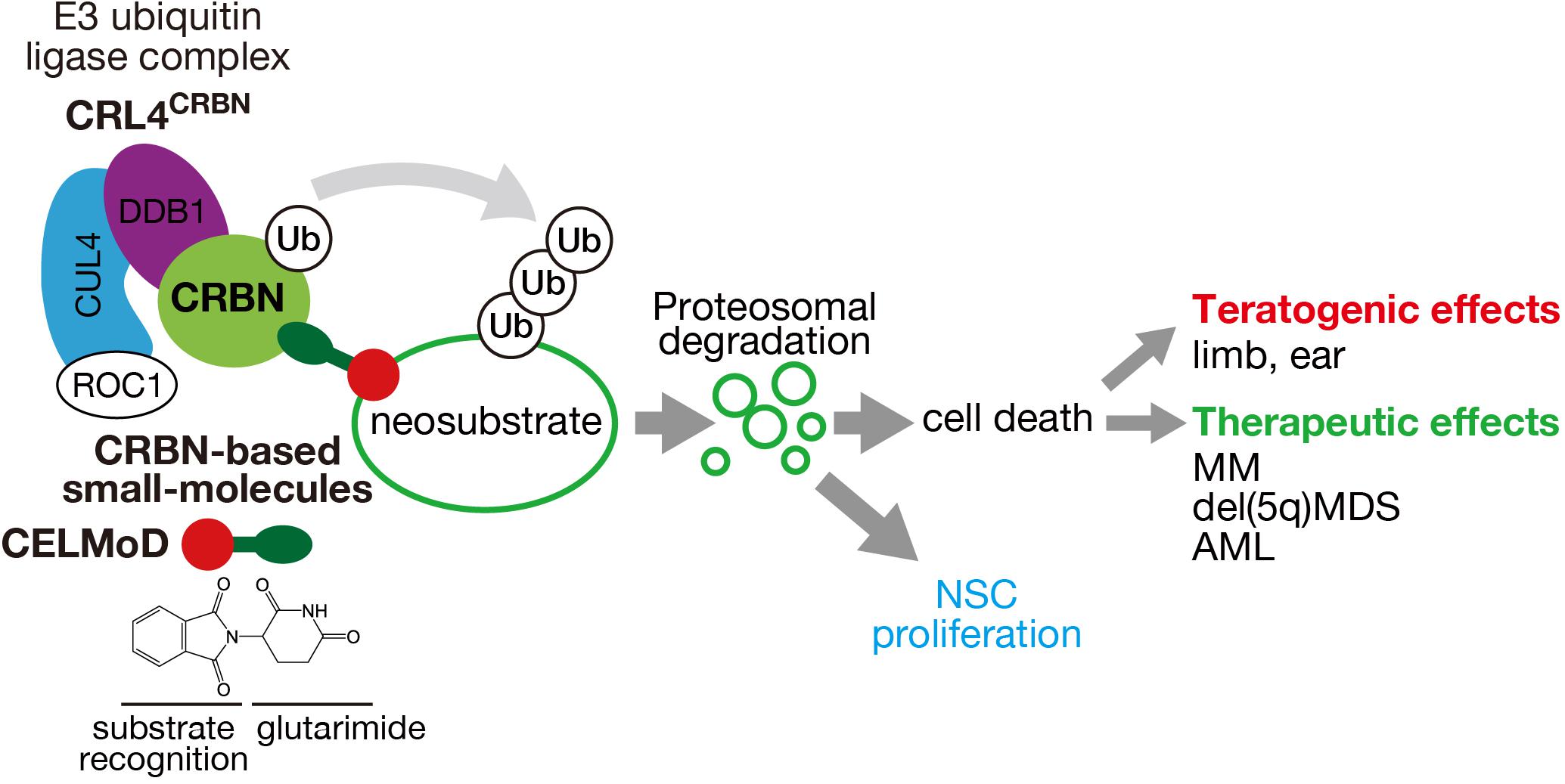

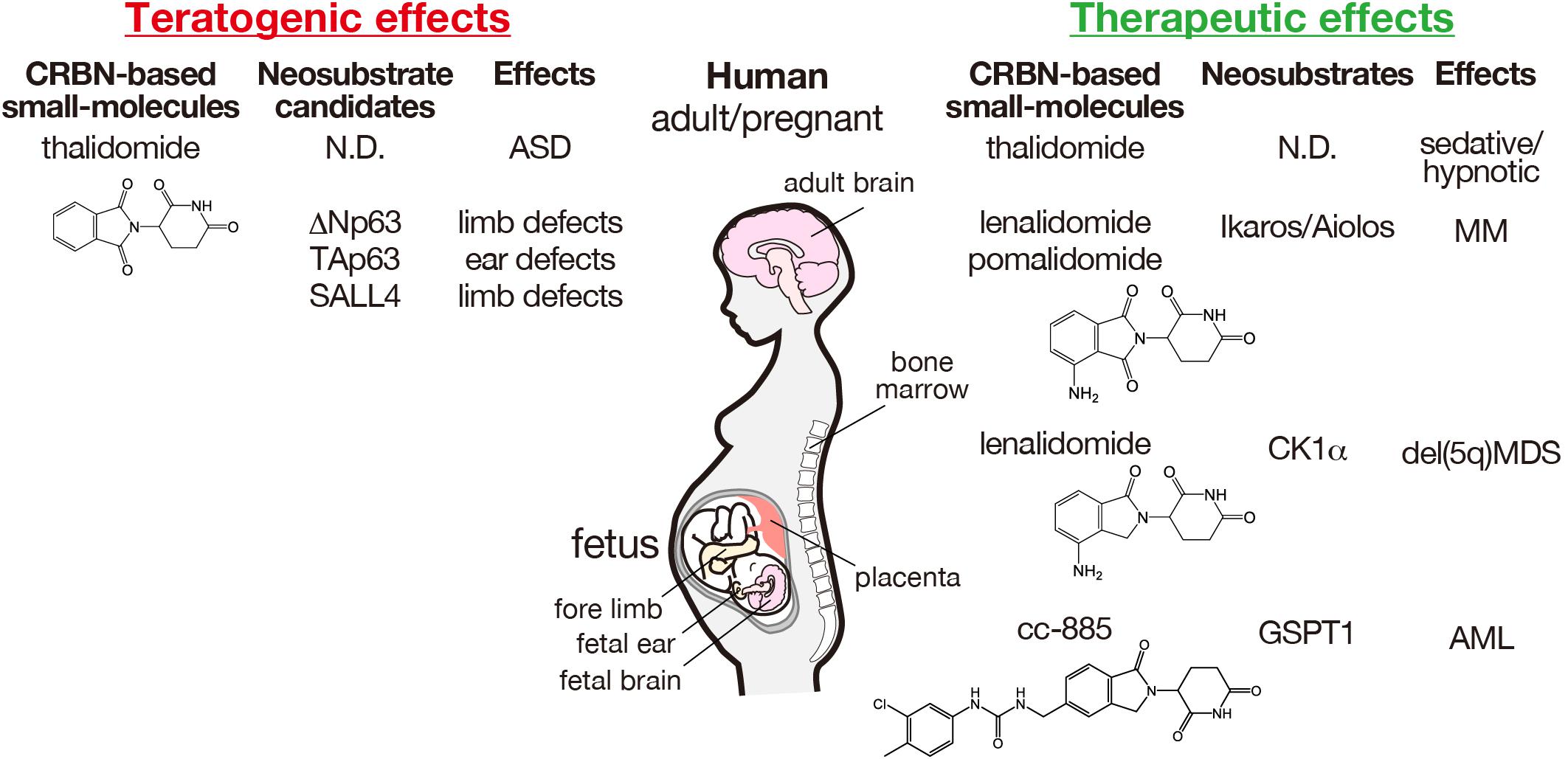

Although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying thalidomide teratogenicity remain obscure, multiple teratogenic effects were considered due to the functional CRBN inhibition, as CRBN is a direct protein target of thalidomide that inhibits the auto-ubiquitination of CRBN (Ito et al., 2010). Furthermore, thalidomide teratogenicity implies that CRBN plays a critical role in human fetal development. However, CRBN-knockout mice exhibit normal brain development, but show impaired presynaptic function owing to enhanced BK channel activity and deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory via exaggerated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity (Higgins et al., 2004; Bavley et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2018). Forebrain-specific conditional CRBN-knockout mice also show hippocampus-dependent deficits in associative learning (Rajadhyaksha et al., 2012). Although the role of CRBN in brain development remains poorly understood, investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of thalidomide and IMiDs revealed that CELMoDs bind to CRBN to alter substrate recognition, leading to ligand-specific neosubstrate degradation (Figure 1). Two different proteins, spalt-like transcription factor 4 (SALL4) and tumor protein 63 (TP63, p63), have been identified as CRBN neosubstrates responsible for the teratogenic effects of thalidomide in the limb and ear (Donovan et al., 2018; Matyskiela et al., 2018; Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019, 2020; Figure 2). In contrast, the original substrates for CRBN during development and any endogenous ligands have not yet been clarified.

Figure 1. Mechanism of action of CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase and its effects through CRBN-based small molecules. CRBN, a substrate receptor of CRL4CRBN, binds to CRBN-based small molecules (IMiDs, CELMoDs, PROTACs) through the glutarimide moiety (green ellipse) and recognizes different neosubstrates depending on the structure (red circle). Polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the target neosubstrates cause cell death or presumably NSC proliferation that leads to various teratogenic and therapeutic effects.

Figure 2. Teratogenic and therapeutic effects of CRBN-based small molecules and the corresponding neosubstrates in humans. The structures of thalidomide and its derivatives are indicated. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; ND, not determined.

SALL4 is a member of the spalt-like family of C2H2 zinc finger transcription factors that is involved in embryonic development. Mutations in SALL4 are associated with Duane-radial ray syndrome/Okihiro syndrome and SALL4-related Holt-Oram syndrome, both of which show phenotypes similar to those of thalidomide embryopathy (Al-Baradie et al., 2002; Kohlhase et al., 2002, 2003). Consistent with these observations, thalidomide was found to induce SALL4 degradation in a species-specific manner (Donovan et al., 2018). SALL4 is expressed in early embryos, including the inner cell mass, heart, and neuroectoderm. Thus, SALL4-deficient mice are embryonic lethal (Sakaki-Yumoto et al., 2006). SALL4 haploinsufficiency results in death in utero, anorectal and heart anomalies, and exencephaly in mice. Therefore, SALL4 may be involved in thalidomide-induced miscarriage or other birth defects in humans. Sall4 is also required for pectoral fin outgrowth (Harvey and Logan, 2006) that seems consistent with thalidomide-induced limb defects in zebrafish (Ito et al., 2010; Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019). However, zebrafish SALL4 is resistant to thalidomide-induced degradation (Donovan et al., 2018), suggesting the presence of other neosubstrates.

We identified p63 as another thalidomide-dependent CRBN neosubstrate and found that it was involved in teratogenic effects in the limb and ear (Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019). P63 is a member of the p53 transcription factor family, also known as tumor suppressors, and plays an important role in limb development (Yang et al., 2002). P63-deficient mouse embryos show severe limb defects similar to thalidomide-induced amelia and defects in craniofacial and epithelial development, suggesting that p63 is essential for ectodermal differentiation, epithelial development, and morphogenesis (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). In humans, mutations in TP63 cause ectodermal dysplasia, cleft lip/palate syndrome, and congenital limb malformations (Rinne et al., 2006). Consistently, knockdown of a p63 isoform, ΔNp63, showed disruptions in epidermal growth and limb development in zebrafish (Lee and Kimelman, 2002). The similarity of these phenotypes to thalidomide embryopathy prompted us to explore the possibility of p63 as a thalidomide-dependent neosubstrate. Using zebrafish, we demonstrated that p63 isoforms ΔNp63α and TAp63α were responsible for teratogenicity in the limb and ear through thalidomide-dependent degradation, respectively (Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019, 2020). P63 is also expressed in the embryonic and adult mouse and human telencephalon (Hernandez-Acosta et al., 2011). Genetic p63 knockdown in the embryonic telencephalon causes embryonic cortical precursor cell apoptosis that is rescued by ΔNp63 expression (Dugani et al., 2009). Nevertheless, constitutive p63 ablation results in no deficits in neural development (Holembowski et al., 2011). In contrast, inducible p63 ablation from embryonic day 12 leads to an increase in neural precursor cell apoptosis in the embryonic cortex (Cancino et al., 2015). These observations suggest that p63 plays an important pro-survival role in the developing brain (Joseph and Hermanson, 2010), also implying that p63 may be a potential neosubstrate for thalidomide teratogenicity in the brain.

The effectiveness of thalidomide against multiple myeloma encouraged Celgene Corporation to develop its derivatives, lenalidomide and pomalidomide that have higher immunomodulation activities (Bartlett et al., 2004). Thalidomide and its derivatives were therefore referred to IMiDs. Consistent with their immunomodulatory activity, we demonstrated that lenalidomide and pomalidomide bounded more strongly to CRBN than to thalidomide (Lopez-Girona et al., 2012), indicating that CRBN is required for both their teratogenic and therapeutic effects. Because CRBN is a CRL4CRBN substrate receptor, the substrates responsible for the therapeutic effects were explored; different ligand-dependent substrates (neosubstrates) have been identified for the therapeutic effects of thalidomide and its derivatives (Kronke et al., 2014, 2015; Lu et al., 2014; Matyskiela et al., 2016; Ito and Handa, 2020; Figure 2).

The transcription factors Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3) that belong to the Ikaros zinc finger family (IKZF), were first identified as lenalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN substrates in multiple myeloma cell lines (Kronke et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014). Ikaros and Aiolos degradation is the main mediator of the anti-myeloma effects of lenalidomide. We revealed that lenalidomide and pomalidomide also induced Ikaros and Aiolos degradation in T cells (Gandhi et al., 2014).

Casein kinase 1A1 (CK1α) was identified as another lenalidomide-dependent CRL4CRBN neosubstrate responsible for the therapeutic effect of lenalidomide against myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion (Kronke et al., 2015). CK1α is a serine/threonine kinase that plays important roles in embryonic and tumor development. CK1α inhibits p53 and negatively regulates Wnt signaling (Huart et al., 2009; Elyada et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012). Consistently, homozygous deletion of the CK1α gene, Csnk1a1, in hematopoietic cells results in apoptosis through p53 activation in conditional knockout mice (Schneider et al., 2014). CK1α degradation by lenalidomide was substantially more extensive than that by thalidomide or pomalidomide, indicating that substrate recognition by CRBN differs depending on the ligand structure (Kronke et al., 2015).

In a thalidomide derivative library developed by Celgene, CC-885 was discovered to possess remarkable therapeutic effects against acute myelogenous leukemia. We identified a CC-885-dependent neosubstrate, G1-to-S phase transition 1 (GSPT1), by immuno-affinity purification and found that CC-885 has an anti-proliferative effect by degrading this neosubstrate (Matyskiela et al., 2016). Because the effects of CC-885 were beyond the scope of immunomodulatory drugs, thalidomide and its derivatives IMiDs have been collectively termed CELMoDs. This recent progress in elucidating the molecular function of CELMoDs supports the hypothesis that these small-molecule compounds confer neosubstrates on CRBN by altering substrate recognition (Chamberlain and Cathers, 2019; Ito and Handa, 2020; Figure 1).

The CRBN-based PROTAC technique utilizes thalidomide or other CRBN-binding compounds combined with small-molecule compounds that interact with the proteins of interest, allowing us to target protein degradation by recruiting CRL4CRBN (Winter et al., 2015; Burslem and Crews, 2020). This targeted protein knockdown with PROTACs opens new possibilities for CELMoDs in drug discovery (Chamberlain and Hamann, 2019; Pettersson and Crews, 2019).

The number of NSCs is determined by the balance of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Caspase-3 and -9 knockout suppresses apoptosis, causing expansion of NSCs/radial glial cells (RGCs), leading to a larger and consequently convoluted cortical surface (Haydar et al., 1999; Rakic, 2009). NSC proliferation and differentiation are strictly regulated during brain development (Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009; Rakic, 2009; Aimone et al., 2014; Florio and Huttner, 2014). In the developing brain, NSCs/RGCs proliferate through symmetric cell divisions or give rise to intermediate (basal) progenitor cells or neurons by asymmetric cell division in the ventricular zone. Intermediate progenitor cells migrate basally along radial fibers and produce two neurons by symmetric cell divisions in the subventricular zone. Thus, NSCs produce differentiated cells (progenitor cells or neurons) at the expense of proliferation. Consequently, the number of NSCs/RGCs at early developmental stages impacts brain size at later stages (Golzio et al., 2012; Malhotra and Sebat, 2012). Indeed, multiple human genes associated with microcephaly, macrocephaly, and megalencephaly are involved in cell division and cell cycle regulation, such as mitotic spindle orientation, centromere formation, microtubule organization, cytokinesis, and signal transduction (Williams et al., 2008; Pirozzi et al., 2018). Moreover, microcephaly and macrocephaly are observed in neurodevelopmental disorders, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability, suggesting that impaired neurogenesis in the embryonic brain accounts for susceptibility to these neurodevelopmental disorders (Courchesne et al., 2007; Vorstman et al., 2017; Bonnet-Brilhault et al., 2018).

During brain development, newly generated neurons migrate into different layers depending on the timing of their generation from RGCs (Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009). Early-born neurons are distributed in the deeper layers, and later-born neurons in the superficial layers; thus, cortical layers are developed in an inside-out manner. A disrupted balance between NSC/RGC proliferation and differentiation could affect cortical circuit organization, as projection neuron subtypes are determined by the cortical layers in which the neurons reside (Greig et al., 2013). Indeed, multiple susceptibility genes for neurodevelopmental disorders, such as PTEN, CHD8, and SYNGAP1 for autism spectrum disorder; KRAS and RHEB for intellectual disability; and DISC1, NRG1, and MAPK3 for schizophrenia are implicated in embryonic neurogenesis, including NSC/NPC proliferation and differentiation, neuron generation and migration, and post-mitotic neuron differentiation during brain development (Abrahams and Geschwind, 2008; Amaral et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2015; Vorstman et al., 2017; Sacco et al., 2018), suggesting that neurodevelopmental disorders are attributed to impaired neurogenesis in the fetal brain (Kaushik and Zarbalis, 2016; Muhle et al., 2018; Sacco et al., 2018). The pathogenic mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders support the hypothesis that fetal development affected by in utero environments, including exposure to teratogens, pathogens, or maternal stress, leads to later-onset diseases (Gluckman et al., 2007).

Fetal exposure to teratogens, including thalidomide as well as other small-molecule compounds such as valproic acid (antiepileptic), misoprostol (antiulcer drug), and ethanol, is associated with autism (Dufour-Rainfray et al., 2011). Prenatal exposure during the first trimester to antidepressants such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), fluoxetine was associated with an increased risk of autism (Velasquez et al., 2013; Andalib et al., 2017; Millard et al., 2017). Fluoxetine promotes neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus and has been proposed to contribute to the therapeutic effects on mood disorders such as major depression in humans (Santarelli et al., 2003; Micheli et al., 2018; Planchez et al., 2020). Consistently, serotonin (5-HT) has multiple roles in adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Song et al., 2017). Most notably, it promotes NSC proliferation through the 5-HT1A receptor in the adult hippocampus (Radley and Jacobs, 2002; Banasr et al., 2004) suggesting that embryonic and adult neurogenesis share a common molecular mechanism mediated by targets of small-molecule compounds. However, adult hippocampal neurogenesis reduces dramatically with age not only in rodents (Altman and Das, 1965; Kempermann et al., 2015), but also in humans (Snyder, 2018; Sorrells et al., 2018). Therefore, reactivation of quiescent NSCs and expansion of endogenous NSCs/NPCs in the brain will be an ideal symptomatic treatment for patients with impaired adult neurogenesis resulting in neurodevelopmental disorders, mood disorders, and neurodegenerative disorders (Li et al., 2013; Herrera-Arozamena et al., 2016; Duncan and Valenzuela, 2017).

We found that thalidomide treatment during early gastrulation resulted in the generation of small heads and eyes in zebrafish embryos (Ando et al., 2019). This is consistent with thalidomide-induced birth defects in mice and humans, indicating that the mechanism underlying thalidomide teratogenicity in brain development is conserved among vertebrates (Miller and Strömland, 1999; Hallene et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2008). Knockdown of CRBN the direct target of thalidomide, elicited p53-dependent apoptosis in the presumptive brain region, suggesting that CRBN is required for neuroepithelial cell survival, including that of NSCs. This is consistent with the teratogenic effects of thalidomide in zebrafish embryos in which thalidomide induces apoptosis in the developing fin bud (Asatsuma-Okumura et al., 2019). A discrepancy in phenotypes between CRBN-knockdown zebrafish and CRBN-knockout mice, as observed for p63, remains an open question, although genetic compensation by mutant mRNA degradation was reported as the molecular mechanism underlying such discrepancies (Rossi et al., 2015; El-Brolosy et al., 2019).

CRBN overexpression by injection of mRNA into one-cell-stage embryos caused expansion of the head at later stages in zebrafish (Ando et al., 2019). CRBN overexpression caused expanded NSC marker sox2 expression in the presumptive brain field as well as an increase in mitotic cells in the telencephalon and an increase in her5-positive NSCs in the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. The effects of CRBN overexpression on early brain development lead to the expanded expression of neural and glial marker genes and results in an enlarged brain. These results suggest that CRBN overexpression promotes the proliferation of sox2-positive NSCs in the developing brain. This conclusion is supported by the fact that another E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, CRL4Mahj, using Mahjong as a substrate receptor, promotes the exit of NSCs from quiescence and leads to the reactivation of proliferation in Drosophila (Ly et al., 2019). These observations may indicate that newly developed CELMoDs including thalidomide analogs corresponding to CRBN overexpression can enhance NSC proliferation if they promote stabilization by inhibition of auto-ubiquitination or degradation of endogenous substrates more efficiently or by degradation of CELMoD-dependent neosubstrates that leads to cell cycle progression or growth factor signal propagation. This type of CELMoD is a potential candidate for therapeutic drugs for treating diseases that affect adult neurogenesis.

Thalidomide has multiple teratogenic effects depending on the time of exposure during development. Early exposure to thalidomide caused a small head in zebrafish embryos, consistent with an increase in the risk of autism and mild intellectual disability that often affect head size in humans. Brain size is primarily affected by the number of NSCs that is determined by the balance of growth, differentiation, and apoptosis during development. Early exposure to small molecules affecting adult neurogenesis, such as antidepressants, increases the risk of autism, suggesting a common molecular mechanism underlying NSC growth and differentiation in the developing and adult brain. Our finding that thalidomide’s direct target, CRBN, regulates NSC proliferation in zebrafish embryonic brain implies that small-molecule compounds, including CELMoDs, can promote NSC growth in the adult brain and thus might be developed as effective therapeutic drugs for regenerative medicine.

TS wrote this article. TS and HH contributed to the conceptualization. TI and HH contributed to the review and editing of this article. All authors approved the study for publication.

This study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (grant nos. 18K09271 to TS and 18H05502 to TI).

HH has received research support from Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abrahams, B. S., and Geschwind, D. H. (2008). Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 341–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2346

Aimone, J. B., Li, Y., Lee, S. W., Clemenson, G. D., Deng, W., and Gage, F. H. (2014). Regulation and function of adult neurogenesis: from genes to cognition. Physiol. Rev. 94, 991–1026. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2014

Al-Baradie, R., Yamada, K., St Hilaire, C., Chan, W. M., Andrews, C., Mcintosh, N., et al. (2002). Duane radial ray syndrome (Okihiro syndrome) maps to 20q13 and results from mutations in SALL4, a new member of the SAL family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1195–1199. doi: 10.1086/343821

Altman, J., and Das, G. D. (1965). Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 124, 319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303

Amaral, D. G., Schumann, C. M., and Nordahl, C. W. (2008). Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 31, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005

Andalib, S., Emamhadi, M. R., Yousefzadeh-Chabok, S., Shakouri, S. K., Hoilund-Carlsen, P. F., Vafaee, M. S., et al. (2017). Maternal SSRI exposure increases the risk of autistic offspring: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur. Psychiatry 45, 161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.06.001

Ando, H., Sato, T., Ito, T., Yamamoto, J., Sakamoto, S., Nitta, N., et al. (2019). Cereblon control of zebrafish brain size by regulation of neural stem cell proliferation. iScience 15, 95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.04.007

Asatsuma-Okumura, T., Ando, H., De Simone, M., Yamamoto, J., Sato, T., Shimizu, N., et al. (2019). p63 is a cereblon substrate involved in thalidomide teratogenicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0366-7

Asatsuma-Okumura, T., Ito, T., and Handa, H. (2020). Molecular mechanisms of the teratogenic effects of thalidomide. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 13:95. doi: 10.3390/ph13050095

Banasr, M., Hery, M., Printemps, R., and Daszuta, A. (2004). Serotonin-induced increases in adult cell proliferation and neurogenesis are mediated through different and common 5-HT receptor subtypes in the dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 450–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300320

Bartlett, J. B., Dredge, K., and Dalgleish, A. G. (2004). The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 314–322. doi: 10.1038/nrc1323

Bavley, C. C., Rice, R. C., Fischer, D. K., Fakira, A. K., Byrne, M., Kosovsky, M., et al. (2018). Rescue of learning and memory deficits in the human nonsyndromic intellectual disability cereblon knock-out mouse model by targeting the AMP-activated protein kinase-mTORC1 translational pathway. J. Neurosci. 38, 2780–2795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0599-17.2018

Bonnet-Brilhault, F., Rajerison, T. A., Paillet, C., Guimard-Brunault, M., Saby, A., Ponson, L., et al. (2018). Autism is a prenatal disorder: evidence from late gestation brain overgrowth. Autism Res. 11, 1635–1642. doi: 10.1002/aur.2036

Burslem, G. M., and Crews, C. M. (2020). Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell 181, 102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031

Cancino, G. I., Fatt, M. P., Miller, F. D., and Kaplan, D. R. (2015). Conditional ablation of p63 indicates that it is essential for embryonic development of the central nervous system. Cell Cycle 14, 3270–3281. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1087618

Chamberlain, P. P., and Cathers, B. E. (2019). Cereblon modulators: low molecular weight inducers of protein degradation. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 31, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.02.004

Chamberlain, P. P., and Hamann, L. G. (2019). Development of targeted protein degradation therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 937–944. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0362-y

Choi, T. Y., Lee, S. H., Kim, Y. J., Bae, J. R., Lee, K. M., Jo, Y., et al. (2018). Cereblon maintains synaptic and cognitive function by regulating BK channel. J. Neurosci. 38, 3571–3583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2081-17.2018

Courchesne, E., Pierce, K., Schumann, C. M., Redcay, E., Buckwalter, J. A., Kennedy, D. P., et al. (2007). Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron 56, 399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016

D’Amora, M., and Giordani, S. (2018). The utility of zebrafish as a model for screening developmental neurotoxicity. Front. Neurosci. 12:976. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00976

Donovan, K. A., An, J., Nowak, R. P., Yuan, J. C., Fink, E. C., Berry, B. C., et al. (2018). Thalidomide promotes degradation of SALL4, a transcription factor implicated in Duane Radial Ray syndrome. Elife 7:e38430. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38430

Driever, W., Stemple, D., Schier, A., and Solnica-Krezel, L. (1994). Zebrafish: genetic tools for studying vertebrate development. Trends Genet. 10, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90091-4

Dufour-Rainfray, D., Vourc’h, P., Tourlet, S., Guilloteau, D., Chalon, S., and Andres, C. R. (2011). Fetal exposure to teratogens: evidence of genes involved in autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 1254–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.013

Dugani, C. B., Paquin, A., Fujitani, M., Kaplan, D. R., and Miller, F. D. (2009). p63 antagonizes p53 to promote the survival of embryonic neural precursor cells. J. Neurosci. 29, 6710–6721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5878-08.2009

Duncan, T., and Valenzuela, M. (2017). Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and stem cell therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8:111. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0567-5

El-Brolosy, M. A., Kontarakis, Z., Rossi, A., Kuenne, C., Gunther, S., Fukuda, N., et al. (2019). Genetic compensation triggered by mutant mRNA degradation. Nature 568, 193–197. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1064-z

Elyada, E., Pribluda, A., Goldstein, R. E., Morgenstern, Y., Brachya, G., Cojocaru, G., et al. (2011). CKIalpha ablation highlights a critical role for p53 in invasiveness control. Nature 470, 409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature09673

Fan, Q. Y., Ramakrishna, S., Marchi, N., Fazio, V., Hallene, K., and Janigro, D. (2008). Combined effects of prenatal inhibition of vasculogenesis and neurogenesis on rat brain development. Neurobiol. Dis. 32, 499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.007

Florio, M., and Huttner, W. B. (2014). Neural progenitors, neurogenesis and the evolution of the neocortex. Development 141, 2182–2194. doi: 10.1242/dev.090571

Fratta, I. D., Sigg, E. B., and Maiorana, K. (1965). Teratogenic effects of thalidomide in rabbits, rats, hamsters, and mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 7, 268–286. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(65)90095-5

Gandhi, A. K., Kang, J., Havens, C. G., Conklin, T., Ning, Y., Wu, L., et al. (2014). Immunomodulatory agents lenalidomide and pomalidomide co-stimulate T cells by inducing degradation of T cell repressors Ikaros and Aiolos via modulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4(CRBN.). Br. J. Haematol. 164, 811–821. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12708

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., and Beedle, A. S. (2007). Early life events and their consequences for later disease: a life history and evolutionary perspective. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 19, 1–19. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20590

Golzio, C., Willer, J., Talkowski, M. E., Oh, E. C., Taniguchi, Y., Jacquemont, S., et al. (2012). KCTD13 is a major driver of mirrored neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 copy number variant. Nature 485, 363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature11091

Greig, L. C., Woodworth, M. B., Galazo, M. J., Padmanabhan, H., and Macklis, J. D. (2013). Molecular logic of neocortical projection neuron specification, development and diversity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 755–769. doi: 10.1038/nrn3586

Hallene, K. L., Oby, E., Lee, B. J., Santaguida, S., Bassanini, S., Cipolla, M., et al. (2006). Prenatal exposure to thalidomide, altered vasculogenesis, and CNS malformations. Neuroscience 142, 267–283. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.017

Harvey, S. A., and Logan, M. P. (2006). Sall4 acts downstream of tbx5 and is required for pectoral fin outgrowth. Development 133, 1165–1173. doi: 10.1242/dev.02259

Haydar, T. F., Kuan, C. Y., Flavell, R. A., and Rakic, P. (1999). The role of cell death in regulating the size and shape of the mammalian forebrain. Cereb. Cortex 9, 621–626. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.621

Hernandez-Acosta, N. C., Cabrera-Socorro, A., Morlans, M. P., Delgado, F. J., Suarez-Sola, M. L., Sottocornola, R., et al. (2011). Dynamic expression of the p53 family members p63 and p73 in the mouse and human telencephalon during development and in adulthood. Brain Res. 1372, 29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.041

Herrera-Arozamena, C., Marti-Mari, O., Estrada, M., De La Fuente Revenga, M., and Rodriguez-Franco, M. I. (2016). Recent advances in neurogenic small molecules as innovative treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 21:1165. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091165

Higgins, J. J., Pucilowska, J., Lombardi, R. Q., and Rooney, J. P. (2004). A mutation in a novel ATP-dependent Lon protease gene in a kindred with mild mental retardation. Neurology 63, 1927–1931. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000146196.01316.a2

Hill, M. A. (2007). Early human development. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 50, 2–9. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31802f119d

Holembowski, L., Schulz, R., Talos, F., Scheel, A., Wolff, S., Dobbelstein, M., et al. (2011). While p73 is essential, p63 is completely dispensable for the development of the central nervous system. Cell Cycle 10, 680–689. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14859

Huart, A. S., Maclaine, N. J., Meek, D. W., and Hupp, T. R. (2009). CK1alpha plays a central role in mediating MDM2 control of p53 and E2F-1 protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32384–32394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052647

Ito, T., Ando, H., Suzuki, T., Ogura, T., Hotta, K., Imamura, Y., et al. (2010). Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science 327, 1345–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1177319

Ito, T., and Handa, H. (2020). Molecular mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 96, 189–203. doi: 10.2183/pjab.96.016

Jo, S., Lee, K. H., Song, S., Jung, Y. K., and Park, C. S. (2005). Identification and functional characterization of cereblon as a binding protein for large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 94, 1212–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03344.x

Joseph, B., and Hermanson, O. (2010). Molecular control of brain size: regulators of neural stem cell life, death and beyond. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.012

Kaufman, C. K., White, R. M., and Zon, L. (2009). Chemical genetic screening in the zebrafish embryo. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1422–1432. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.144

Kaushik, G., and Zarbalis, K. S. (2016). Prenatal neurogenesis in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Chem. 4:12. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2016.00012

Kempermann, G., Song, H., and Gage, F. H. (2015). Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a018812. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018812

Kohlhase, J., Heinrich, M., Schubert, L., Liebers, M., Kispert, A., Laccone, F., et al. (2002). Okihiro syndrome is caused by SALL4 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2979–2987. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2979

Kohlhase, J., Schubert, L., Liebers, M., Rauch, A., Becker, K., Mohammed, S. N., et al. (2003). Mutations at the SALL4 locus on chromosome 20 result in a range of clinically overlapping phenotypes, including Okihiro syndrome, Holt-Oram syndrome, acro-renal-ocular syndrome, and patients previously reported to represent thalidomide embryopathy. J. Med. Genet. 40, 473–478. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.7.473

Kriegstein, A., and Alvarez-Buylla, A. (2009). The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600

Kronke, J., Fink, E. C., Hollenbach, P. W., Macbeth, K. J., Hurst, S. N., Udeshi, N. D., et al. (2015). Lenalidomide induces ubiquitination and degradation of CK1alpha in del(5q) MDS. Nature 523, 183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature14610

Kronke, J., Udeshi, N. D., Narla, A., Grauman, P., Hurst, S. N., Mcconkey, M., et al. (2014). Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science 343, 301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1244851

Lee, H., and Kimelman, D. (2002). A dominant-negative form of p63 is required for epidermal proliferation in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2, 607–616. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00166-1

Li, W., Li, K., Wei, W., and Ding, S. (2013). Chemical approaches to stem cell biology and therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell 13, 270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.002

Lieschke, G. J., and Currie, P. D. (2007). Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 353–367. doi: 10.1038/nrg2091

Lopez-Girona, A., Mendy, D., Ito, T., Miller, K., Gandhi, A. K., Kang, J., et al. (2012). Cereblon is a direct protein target for immunomodulatory and antiproliferative activities of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Leukemia 26, 2326–2335. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.119

Lu, G., Middleton, R. E., Sun, H., Naniong, M., Ott, C. J., Mitsiades, C. S., et al. (2014). The myeloma drug lenalidomide promotes the cereblon-dependent destruction of Ikaros proteins. Science 343, 305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1244917

Ly, P. T., Tan, Y. S., Koe, C. T., Zhang, Y., Xie, G., Endow, S., et al. (2019). CRL4Mahj E3 ubiquitin ligase promotes neural stem cell reactivation. PLoS Biol. 17:e3000276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000276

Malhotra, D., and Sebat, J. (2012). Genetics: fish heads and human disease. Nature 485, 318–319. doi: 10.1038/485318a

Matyskiela, M. E., Couto, S., Zheng, X., Lu, G., Hui, J., Stamp, K., et al. (2018). SALL4 mediates teratogenicity as a thalidomide-dependent cereblon substrate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 981–987. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0129-x

Matyskiela, M. E., Lu, G., Ito, T., Pagarigan, B., Lu, C. C., Miller, K., et al. (2016). A novel cereblon modulator recruits GSPT1 to the CRL4(CRBN) ubiquitin ligase. Nature 535, 252–257. doi: 10.1038/nature18611

Meshalkina, D. A., Kizlyk, M. N., Kysil, E. V., Collier, A. D., Echevarria, D. J., Abreu, M. S., et al. (2018). Zebrafish models of autism spectrum disorder. Exp. Neurol. 299, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.02.004

Micheli, L., Ceccarelli, M., D’andrea, G., Costanzi, M., Giacovazzo, G., Coccurello, R., et al. (2018). Fluoxetine or Sox2 reactivate proliferation-defective stem and progenitor cells of the adult and aged dentate gyrus. Neuropharmacology 141, 316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.08.023

Millard, S. J., Weston-Green, K., and Newell, K. A. (2017). The effects of maternal antidepressant use on offspring behaviour and brain development: implications for risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80, 743–765. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.008

Miller, M. T., and Strömland, K. (1999). Teratogen update: thalidomide: a review, with a focus on ocular findings and new potential uses. Teratology 60, 306–321. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199911)60:5<306::AID-TERA11<3.0.CO;2-Y

Miller, M. T., Strömland, K., Ventura, L., Johansson, M., Bandim, J. M., and Gillberg, C. (2005). Autism associated with conditions characterized by developmental errors in early embryogenesis: a mini review. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 23, 201–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.06.007

Mills, A. A., Zheng, B., Wang, X. J., Vogel, H., Roop, D. R., and Bradley, A. (1999). p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398, 708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531

Muhle, R. A., Reed, H. E., Stratigos, K. A., and Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. (2018). The emerging clinical neuroscience of autism spectrum disorder: a review. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 514–523. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4685

Pettersson, M., and Crews, C. M. (2019). PROteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) - past, present and future. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 31, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002

Pirozzi, F., Nelson, B., and Mirzaa, G. (2018). From microcephaly to megalencephaly: determinants of brain size. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 20, 267–282. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.4/gmirzaa

Planchez, B., Surget, A., and Belzung, C. (2020). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressants effects. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 50, 88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2019.11.009

Radley, J. J., and Jacobs, B. L. (2002). 5-HT1A receptor antagonist administration decreases cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 955, 264–267. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03477-7

Rajadhyaksha, A. M., Ra, S., Kishinevsky, S., Lee, A. S., Romanienko, P., Duboff, M., et al. (2012). Behavioral characterization of cereblon forebrain-specific conditional null mice: a model for human non-syndromic intellectual disability. Behav. Brain Res. 226, 428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.09.039

Rakic, P. (2009). Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719

Rinne, T., Hamel, B., Van Bokhoven, H., and Brunner, H. G. (2006). Pattern of p63 mutations and their phenotypes–update. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 140, 1396–1406. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31271

Rossi, A., Kontarakis, Z., Gerri, C., Nolte, H., Holper, S., Kruger, M., et al. (2015). Genetic compensation induced by deleterious mutations but not gene knockdowns. Nature 524, 230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature14580

Sacco, R., Cacci, E., and Novarino, G. (2018). Neural stem cells in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 48, 131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.12.005

Sakai, C., Ijaz, S., and Hoffman, E. J. (2018). Zebrafish models of neurodevelopmental disorders: past, present, and future. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:294. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00294

Sakaki-Yumoto, M., Kobayashi, C., Sato, A., Fujimura, S., Matsumoto, Y., Takasato, M., et al. (2006). The murine homolog of SALL4, a causative gene in Okihiro syndrome, is essential for embryonic stem cell proliferation, and cooperates with Sall1 in anorectal, heart, brain and kidney development. Development 133, 3005–3013. doi: 10.1242/dev.02457

Sakamoto, K. M., Kim, K. B., Kumagai, A., Mercurio, F., Crews, C. M., and Deshaies, R. J. (2001). Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141230798

Santarelli, L., Saxe, M., Gross, C., Surget, A., Battaglia, F., Dulawa, S., et al. (2003). Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 301, 805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328

Sato, T., Sato, F., Kamezaki, A., Sakaguchi, K., Tanigome, R., Kawakami, K., et al. (2015). Neuregulin 1 type II-ErbB signaling promotes cell divisions generating neurons from neural progenitor cells in the developing zebrafish brain. PLoS One 10:e0127360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127360

Schneider, R. K., Adema, V., Heckl, D., Jaras, M., Mallo, M., Lord, A. M., et al. (2014). Role of casein kinase 1A1 in the biology and targeted therapy of del(5q) MDS. Cancer Cell 26, 509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.08.001

Schumacher, H., Blake, D. A., Gurian, J. M., and Gillette, J. R. (1968). A comparison of the teratogenic activity of thalidomide in rabbits and rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 160, 189–200.

Sheereen, A., Alaamery, M., Bawazeer, S., Al Yafee, Y., Massadeh, S., and Eyaid, W. (2017). A missense mutation in the CRBN gene that segregates with intellectual disability and self-mutilating behaviour in a consanguineous Saudi family. J. Med. Genet. 54, 236–240. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104117

Snyder, J. S. (2018). Questioning human neurogenesis. Nature 555, 315–316. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-02629-3

Song, N. N., Huang, Y., Yu, X., Lang, B., Ding, Y. Q., and Zhang, L. (2017). Divergent roles of central serotonin in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:185. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00185

Sorrells, S. F., Paredes, M. F., Cebrian-Silla, A., Sandoval, K., Qi, D., Kelley, K. W., et al. (2018). Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature25975

Strömland, K., Nordin, V., Miller, M., Akerstrom, B., and Gillberg, C. (1994). Autism in thalidomide embryopathy: a population study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 36, 351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11856.x

Vargesson, N. (2015). Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: history and mechanisms. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 105, 140–156. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21096

Vaz, R., Hofmeister, W., and Lindstrand, A. (2019). Zebrafish models of neurodevelopmental disorders: limitations and benefits of current tools and techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:1296. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061296

Velasquez, J. C., Goeden, N., and Bonnin, A. (2013). Placental serotonin: implications for the developmental effects of SSRIs and maternal depression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:47. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00047

Vorstman, J. A. S., Parr, J. R., Moreno-De-Luca, D., Anney, R. J. L., Nurnberger, J. I. Jr., and Hallmayer, J. F. (2017). Autism genetics: opportunities and challenges for clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 362–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.4

Williams, C. A., Dagli, A., and Battaglia, A. (2008). Genetic disorders associated with macrocephaly. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 146A, 2023–2037. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32434

Winter, G. E., Buckley, D. L., Paulk, J., Roberts, J. M., Souza, A., Dhe-Paganon, S., et al. (2015). DRUG DEVELOPMENT. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science 348, 1376–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1433

Wu, S., Chen, L., Becker, A., Schonbrunn, E., and Chen, J. (2012). Casein kinase 1alpha regulates an MDMX intramolecular interaction to stimulate p53 binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 4821–4832. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00851-12

Yang, A., Kaghad, M., Caput, D., and Mckeon, F. (2002). On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 18, 90–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02595-7

Keywords: zebrafish, thalidomide, cereblon, neural stem cells, brain development, CELMoDs, PROTAC

Citation: Sato T, Ito T and Handa H (2021) Cereblon-Based Small-Molecule Compounds to Control Neural Stem Cell Proliferation in Regenerative Medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:629326. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.629326

Received: 14 November 2020; Accepted: 15 February 2021;

Published: 11 March 2021.

Edited by:

Yasuhito Shimada, Mie University, JapanReviewed by:

Arupratan Das, Indiana University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Sato, Ito and Handa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomomi Sato, dG9zYXRvQHNhaXRhbWEtbWVkLmFjLmpw; Hiroshi Handa, aGhhbmRhQHRva3lvLW1lZC5hYy5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.