- Laboratory of Molecular Oncology, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy and Cancer Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University Collaborative Innovation Center of Biotherapy, Chengdu, China

Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1) is an evolutionally conserved and unique enzyme that specifically catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of phosphorylated serine/threonine-proline (pSer/Thr-Pro) motif and, subsequently, induces the conformational change of its substrates. Mounting evidence has demonstrated that Pin1 is widely overexpressed and/or overactivated in cancer, exerting a critical influence on tumor initiation and progression via regulation of the biological activity, protein degradation, or nucleus-cytoplasmic distribution of its substrates. Moreover, Pin1 participates in the cancer hallmarks through activating some oncogenes and growth enhancers, or inactivating some tumor suppressors and growth inhibitors, suggesting that Pin1 could be an attractive target for cancer therapy. In this review, we summarize the findings on the dysregulation, mechanisms, and biological functions of Pin1 in cancer cells, and also discuss the significance and potential applications of Pin1 dysregulation in human cancer.

Introduction

Cellular processes are spatially and temporally regulated by a number of molecular machineries consisting of proteins and nucleic acids (Csizmok et al., 2016; Koelwyn et al., 2017; Hentze et al., 2018). Diverse regulatory mechanisms have been well established to interpret cellular processes, such as epigenetic changes, allosteric regulations, and post-translational modifications (Aebersold and Mann, 2016; Changeux and Christopoulos, 2016; Luo et al., 2018). Among them, post-translational modifications are currently emerging as an important regulator of cell fate and thus have a strong potential to be implicated in cellular disorders (Barber et al., 2018; Steklov et al., 2018). As a dominative component of post-translational modifications, protein phosphorylation in response to extracellular or intracellular stimuli mainly controls the signal transduction within cells (Boss and Im, 2012), which often includes conformational changes in kinase-phosphorylated substrates (He et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2016). Therein, the conformational switch of peptide bonds precisely regulated by prolyl cis-trans isomerization plays a central role in many aspects of cellular processes (Lu et al., 2007; Marsolier et al., 2015).

Proline residues in proteins have cis and trans peptide bond conformations, which are tightly orchestrated by prolyl cis-trans isomerization (Lummis et al., 2005; Zosel et al., 2018). Proline conversion occurs very slowly in aqueous solution (Fischer and Aumuller, 2003). But in the presence of peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerases (PPIases), the cis-trans rotation of peptide bond is stimulated, thereby adjusting the spatial arrangement of protein backbone segments (Theuerkorn et al., 2011). There are four evolutionally conserved PPIase subfamilies: cyclophilins, FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs), parvulins, and protein phosphatase 2A phosphatase activator (PTPA) (Thapar, 2015; Zhou and Lu, 2016). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1), a member of parvulins subfamily, was originally identified in 1996 (Lu et al., 1996), and is a unique enzyme that specifically catalyzes the isomerization of phosphorylated serine-proline or phosphorylated threonine-proline (pSer/Thr-Pro) motifs, representing a novel mechanism that protein conformation after Ser/Thr-Pro phosphorylation can be regulated by Pin1 to display alterable biological functions (Lu and Hunter, 2014; Zhou and Lu, 2016). Furthermore, the data from global mass spectrometry analysis have suggested a high percentage of serine/threonine phosphorylation in all phosphorylated proteins (Shi, 2009). Thus, Pin1 is of great interest to scientists committing to the research of molecular cell biology.

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that Pin1-mediated prolyl isomerization exerts a pivotal effect on multiple physiological processes including cell growth, cell cycle regulation, immune response, neuronal differentiation, and tumorigenesis (Sacktor, 2010; Tun-Kyi et al., 2011; Daza-Martin et al., 2019). In cancer—one of the leading causes of human death worldwide (Bray et al., 2018)—Pin1 is widely overexpressed and/or overactivated compared with normal cells or tissues (Pang et al., 2004; Pulikkan et al., 2010; Lu and Hunter, 2014). A high level of Pin1 overexpression/overactivation closely correlates to poor clinical prognosis of diverse cancers (Wang et al., 2015; Zhou and Lu, 2016). Through multiple regulatory mechanisms, Pin1 promotes tumor initiation, development, and drug resistance by acting as an activator of some oncogenes and growth enhancers, or as an inactivator of some tumor suppressors and growth inhibitors (Yeh and Means, 2007; Lu and Hunter, 2014; Zhou and Lu, 2016). Therefore, these achievements provide strong evidence that Pin1 is an attractive target for cancer therapy, leading to the discovery of Pin1 inhibitors for treating cancer and preventing drug resistance.

Given the critical role of Pin1 in cancer, here we review the recent findings about dysregulation, mechanisms, and biological functions of Pin1 in cancer cells, and also discuss the significance and potential applications of Pin1 dysregulation in human cancer.

Pin1 Dysregulation in Cancer

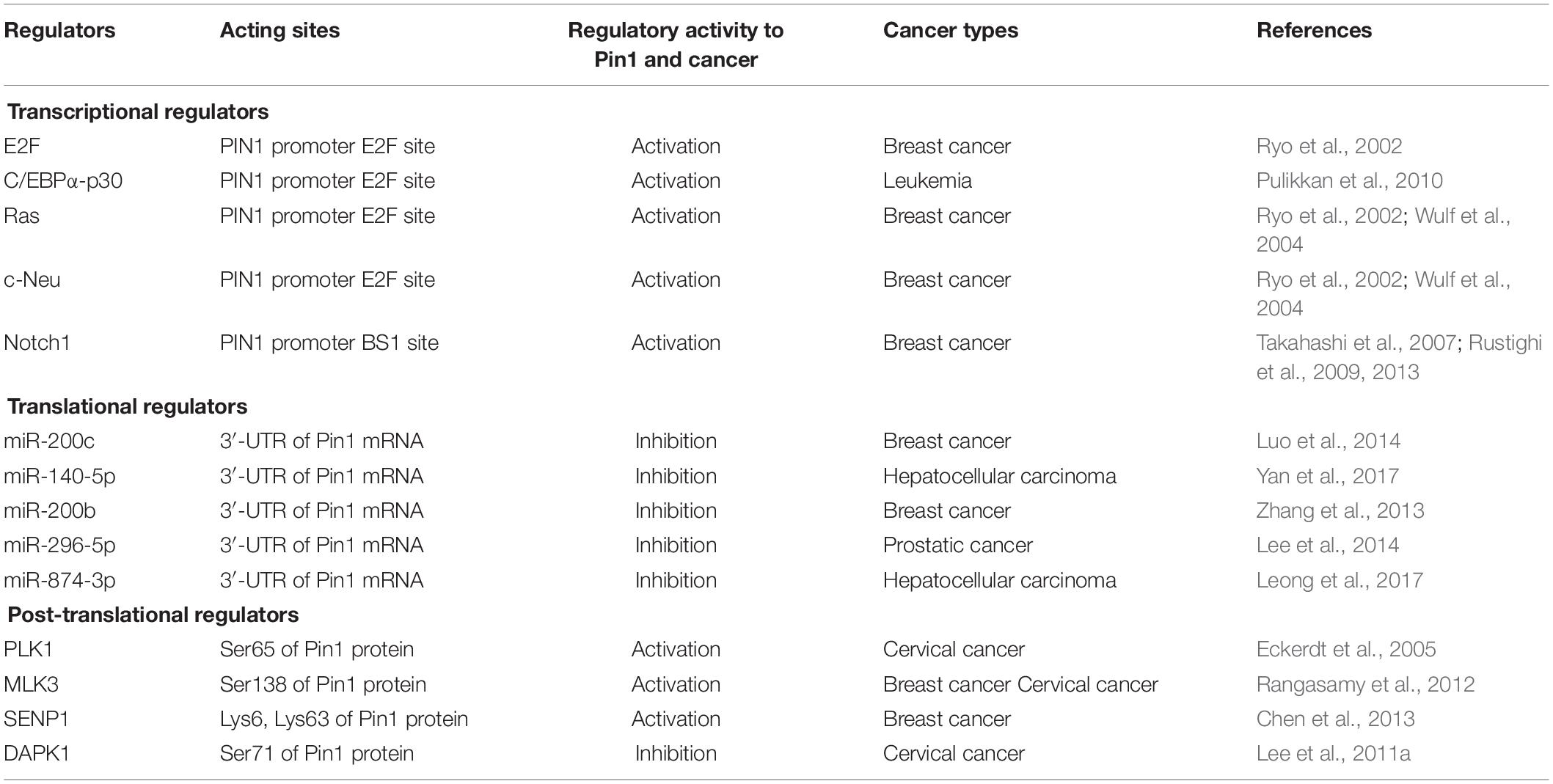

The PIN1 gene is located on chromosome 19p13.2 and encodes Pin1 isomerase, composed of 163 amino acids (Lu et al., 1996; Ranganathan et al., 1997; Modena et al., 2006). In normal tissues and cells, the level of Pin1 expression is usually closely correlated to the cell proliferation potential (Saegusa et al., 2010), and Pin1 level in tissues decreases with aging (Lee et al., 2011b). However, Pin1 is aberrantly upregulated or overactivated in many tumors or cells with a tendency to differentiate into tumors (Chen et al., 2018). Varied transcriptional, translational, and post-translational factors contribute to Pin1 dysregulation in cancer cells (Table 1).

Pin1 expression is regulated by a series of transcriptional factors. The E2F family are highly active in nearly all cancer types, regulating gene expression driven by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)-Rb-E2F axis (Dick et al., 2018; Kent and Leone, 2019). PIN1 transcription is stimulated by the E2F family, which is located on the E2F binding sites of the PIN1 promoter (Ryo et al., 2002). Additionally, E2Fs-mediated Pin1 transcription is also activated by other transcriptional factors. C/EBPα-p30, a mutant of transcription factor C/EBPα, which was found in around 9% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, induces Pin1 expression by recruiting E2F1 in the PIN1 promoter and enhances leukemia (Pulikkan et al., 2010). PIN1 promoter activity is also induced by Neu and Ras signaling via E2F activation in breast cancer (Ryo et al., 2002; Wulf et al., 2004). Unlike other transcriptional factors, Notch1 specifically binds the distal BS1 element of PIN1 promoter and directly triggers PIN1 transcription, where Pin1 potentiates Notch1 cleavage by γ-secretase to increase Notch1 transcriptional activity, thereby generating a positive loop to upregulate Pin1 expression in human breast cancer (Takahashi et al., 2007; Rustighi et al., 2009, 2013). Because transcriptional factors of Pin1 are generally overactivated by upstream oncogenic signaling (Pabst et al., 2001; Giuli et al., 2019; Kent and Leone, 2019), the above-mentioned evidence gives an explanation, at least in part, for the upregulation of Pin1 in cancer cells.

Along with transcriptional regulation, Pin1 expression is also controlled at post-transcriptional levels, including mRNA stability and protein translation. miRNAs are a class of small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by repressing protein translation or destabilizing target mRNAs by forming a functional RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Garzon et al., 2010; Inui et al., 2010). Diverse miRNAs are found to regulate Pin1 expression. For example, miR-200c is reported to directly target the 3′-UTR of Pin1 mRNA, thus decreasing Pin1 level in breast cancer (Luo et al., 2014). MiR-140-5p is also identified as a potential negative regulator of Pin1 expression by directly binding to the 3′-UTR of Pin1 mRNA, inhibiting Pin1 translation in hepatocellular carcinoma (Yan et al., 2017). Moreover, miR-200b, miR-296-5p, and miR-874-3p were found to be Pin1-targeted miRNAs (Zhang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Leong et al., 2017). Given the fact that global miRNA expression is downregulated in tumors (Lu et al., 2005; Hermeking, 2012; Zhang et al., 2015), this reduced miRNA expression could lead to Pin1 overexpression in cancer.

Post-translational regulation is another strategy affecting Pin1 dysregulation. PLK1, a trigger for G2/M transition, mediates phosphorylation of Ser65 in Pin1, stabilizing Pin1 by inhibiting its ubiquitination in human cancer cells (Eckerdt et al., 2005). MLK3, a MAP3K family member, phosphorylates Pin1 on a Ser138 site to activate its catalytic function and nuclear translocation, driving the cell cycle and promoting cyclin D1 stability and centrosome amplification of cancer cells (Rangasamy et al., 2012). By contrast, DAPK1, a known tumor suppressor, associates with and phosphorylates Pin1 on Ser71, which suppresses Pin1 nuclear localization and sustains cell cycle by activating cyclin D1 promoter in cells (Lee et al., 2011a). In addition, SENP1 binds to and deSUMOylates Pin1, leading to increased Pin1 stability and enhanced centrosome amplification and cell transformation during tumorigenesis (Chen et al., 2013). Collectively, Pin1 is aberrantly overexpressed/overactivated in multiple tumors through transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational regulations.

Pin1 Participates in Tumorigenesis Via Multiple Mechanisms

Pin1 is mainly localized in the nucleus of both normal and cancer cells, colocalizing with a series of nucleoproteins, such as NEK6 (Chen et al., 2006), but its nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution could be changed upon phosphorylation by kinases including the above-mentioned DAPK1 and MLK3 (Lee et al., 2011a; Rangasamy et al., 2012). Recently, Chen et al. (2018) reviewed 81 Pin1 targets in human cancer. We have checked these targets based on published articles and found that Pin1 regulates 29 targets in the nucleus and 35 targets in the cytoplasm (the rest are unknown for their cellular localization), indicating that Pin1 has no apparent preference between its nuclear or cytoplasmic clients. Additionally, Pin1 participates in cancer development via transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational mechanisms, and these mechanisms operate in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Lu and Hunter, 2014; Zhou and Lu, 2016). Thus, Pin1 has both nuclear and cytoplasmic functions, and is extensively involved in the initiation and progression of cancer.

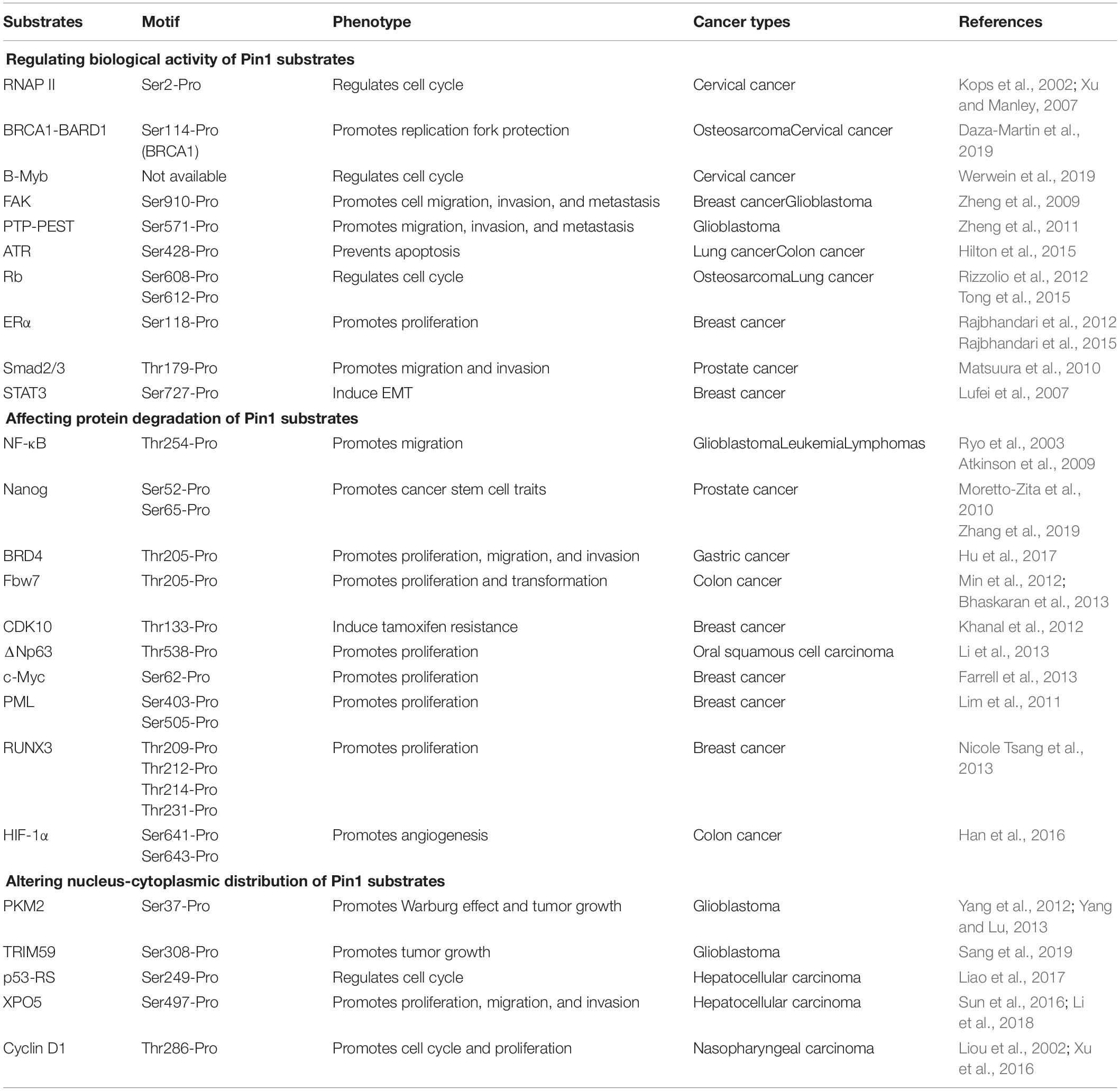

Structurally, Pin1 contains an N-terminal WW domain and a C-terminal PPIase domain, and these two domains are connected by a flexible sequence (Yaffe et al., 1997). It is well-established that WW domain is responsible for specifically recognizing and binding the pSer/Thr-Pro segment of its substrates (Lu et al., 1999; Verdecia et al., 2000), while PPIase domain is the bona fide component catalyzing the conformation change of pSer/Thr-Pro’s peptide bond (Yaffe et al., 1997; Lu et al., 2007). Recently, a new opinion has emerged that the WW domain is also an allosteric effector. Substrate binding to Pin1 WW domain changes the intra/inter domain mobility under a stereoselective manner, thereby altering the binding and catalysis in the distal PPIase domain (Namanja et al., 2011; Peng, 2015). The data from computational calculations also support this opinion and further predicts that Ile28 at the flexible sequence between the PPIase and WW domains is a potential key residue responsible for bridging the communication between the two domains to realize Pin1 allostery (Barman and Hamelberg, 2016; Momin et al., 2018). Considering the phosphorylated state of its substrates, Pin1 renders a functional diversity and/or pathological consequences of given substrates (Zhou and Lu, 2016; Chen et al., 2018), which is achieved mainly through three mechanisms: regulating biological activity, protein degradation, and nucleus-cytoplasm distribution of its substrates (Table 2).

Regulating Biological Activity of Pin1 Substrates

The biological activities of most human proteins are conformationally specific (Papaleo et al., 2016). Pin1-mediated conformational change significantly impacts their functions. The C-terminal domain (CTD) of the RNA polymerase (RNAP) II plays a critical role in pre-mRNA transcription (Bentley, 2014; Jeronimo et al., 2016). Pin1 affects CTD phosphorylation and RNAP II activity during initiation of the transcription cycle, and not during elongation, suggesting the functional role of Pin1 in RNA transcription (Kops et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2003; Xu and Manley, 2007). Pin1 also enhances BRCA1-BARD1 interaction with RAD51, thereby increasing the presence of RAD51 at stalled replication structures and governing replication fork protection during cancer development (Daza-Martin et al., 2019). Moreover, B-Myb phosphorylated by CDK is isomerized by Pin1, enabling PLK1 docking and subsequent PLK1-mediated B-Myb phosphorylation to stimulate transcription of late cell cycle genes (Werwein et al., 2019). In Ras-activated tumor cells, the function of FAK and PTP-PEST are also regulated by Pin1. Pin1 isomerizes both Ser910-phosphorylated FAK and Ser571-phosphorylated PTP-PEST to enhance the interaction between PTP-PEST and FAK, leading to the dephosphorylation of FAK Tyr397 by PTP-PEST and the promotion of migration, invasion, and metastasis of Ras-related tumor cells (Zheng et al., 2009, 2011).

In addition to activating substrate activity, Pin1 is also able to deactivate substrates. ATR, a PI3K-like protein kinase, has an antiapoptotic activity at mitochondria in response to UV-induced DNA damage. In cancer cells, this mitochondrial activity is reduced by Pin1 that catalyzes ATR from cis-isomer to trans-isomer at the phosphorylated Ser428-Pro motif (Hilton et al., 2015). Moreover, the function of the tumor suppressor Rb is largely regulated by a dynamic balance of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Pin1 directly interacts with the spacer domain of Rb protein, and allows the interaction between CDK/cyclin complexes and Rb in mid/late G1, leading to the inactivation of Rb (Rizzolio et al., 2012; Tong et al., 2015). Subsequently, the Pin1-induced Rb inactivation leads to the dissociation of E2F from Rb and increased E2F transcriptional activity, triggering the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins and promoting cell cycle progression through the G1 checkpoint in cancer cells (Cheng and Tse, 2018).

Affecting Protein Degradation of Pin1 Substrates

Pin1 has the ability to prevent protein degradation of oncogenes and growth-promoting regulators. For example, Pin1 associates with the pThr254-Pro motif of transcription factor NF-κB p65 subunit, leading to the increased protein stability of p65 and enhanced transcriptional activity of NF-κB in various cancers, including leukemia, lymphomas, and glioblastoma (Ryo et al., 2003; Atkinson et al., 2009). In prostate cancer, tumor suppressor SPOP interacts with Nanog and promotes Nanog poly-ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, but Pin1 functions as an upstream Nanog regulator and impairs its recognition by SPOP, stabilizing Nanog to promote the cancer stem cell traits and tumor progression (Zhang et al., 2019). Moreover, Pin1 directly binds to and isomerizes phosphorylated Thr204-Pro205 motif of BRD4 to enhance its stability by inhibiting its polyubiquitination, promoting BRD4’s interaction with CDK9 and its transcriptional activity. Substitution of BRD4 with Pin1-binding-defective BRD4-T204A mutant reduces BRD4 stability, which attenuates BRD4-mediated gene expression and suppresses cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumor formation, suggesting the positive correlation of Pin1 function and BRD4 stability in gastric cancer cells (Hu et al., 2017).

Pin1 could also promote the protein degradation of tumor suppressors and growth-inhibitory regulators. Fbw7 is the substrate recognition component of the E3 ligase complex and is critical for ubiquitylation and degradation of given proteins (Ji et al., 2015). Pin1 interacts with Fbw7 and induces Fbw7 self-ubiquitination and protein degradation by disrupting Fbw7 dimerization, contributing to oncogenesis. By contrast, depletion of Pin1 in cancer cells leads to elevated Fbw7 expression, which subsequently reduces Mcl-1 abundance, sensitizing cancer cells to taxol treatment (Min et al., 2012; Bhaskaran et al., 2013). An inverse correlation between the expression of CDK10 and the degree of tamoxifen resistance suggests CDK10 could be an important determinant of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Pin1 facilitates CDK10 degradation as a result of its interaction with, and subsequent ubiquitination of, CDK10, thereby suggesting that the Pin1-mediated CDK10 ubiquitination is a major regulator of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cell growth and survival (Khanal et al., 2012).

Altering Nucleus-Cytoplasmic Distribution of Pin1 Substrates

Changing the nucleus-cytoplasm distribution is another mechanism of Pin1 function. A typical example is PKM2. Upon the activation of EGFR signaling, Ser37-phosphorylated PKM2 recruits Pin1 for cis-trans isomerization and promotes PKM2 binding to importin α5 and translocating to the nucleus, where nuclear PKM2 acts as a coactivator of β-catenin to promotes the Warburg effect and tumorigenesis (Yang et al., 2012; Yang and Lu, 2013). This process is similar to the recently published mechanism of TRIM59 (Sang et al., 2019). In addition, the mechanism underlying the gain-of-function of p53-R249S (p53-RS), a p53 mutant frequently detected in hepatocellular carcinoma, is also mediated by Pin1. In detail, Pin1 isomerizes p53-RS phosphorylated by CDK4 in the G1/S phase and enhances nuclear localization of p53-RS, resulting in a p53-RS-c-Myc interaction and an elevated c-Myc-dependent rDNA transcription key for ribosomal biogenesis, which promotes cell cycle progression and cell growth of hepatocellular carcinoma (Liao et al., 2017).

Recently, we have demonstrated that Pin1 plays an important role in miRNA biogenesis. XPO5-mediated nucleus-to-cytoplasm export of precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) is a post-transcriptional step in the process of miRNA biogenesis (Lin and Gregory, 2015; Peng and Croce, 2016; Wu et al., 2018). Pin1 blocks nucleus-to-cytoplasm export of XPO5 phosphorylated by ERK kinase, decreasing mature miRNA biogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma (Sun et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Pu et al., 2018). Moreover, this impaired miRNA biogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma could be restored by novel Pin1 inhibitors and their formulations (Pu et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019), giving new insight into the therapy of liver cancer.

Significance of Pin1 Dysregulation in Tumor

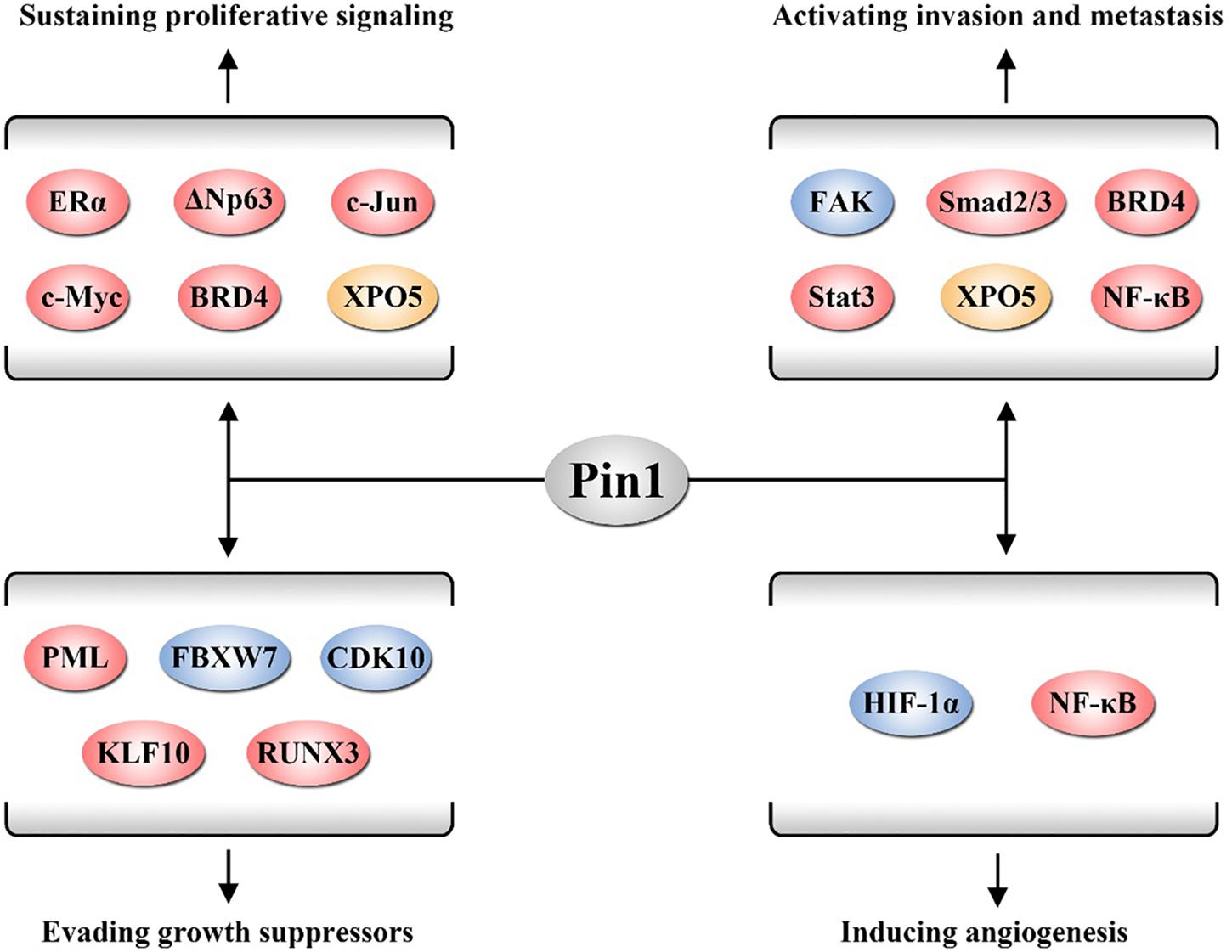

Following the epoch-making conclusion by Hanahan and Weinberg (2011), the major cancer hallmarks are summarized, such as sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, activating invasion and metastasis, and inducing angiogenesis. Emerging evidence demonstrates that Pin1 promotes cancer by acting as an activator of numerous oncogenes and growth enhancers or as an inactivator of numerous tumor suppressors and growth inhibitors to affect cancer hallmarks (Zhou and Lu, 2016). In this section, we review the roles of Pin1 in these cancer hallmarks (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pin1 is involved in several cancer hallmarks. Pin1 activates a number of oncogenic proteins to sustain proliferative signaling, evade growth suppressors, activate invasion and metastasis, and induce angiogenesis. The proteins displayed in red, yellow, and blue participate in these hallmarks through regulating biological activity, affecting protein degradation, and altering nucleus-cytoplasm distribution of its substrates, respectively.

Pin1 Sustains the Proliferative Signaling

Cancer cells possess an excessive cell proliferation ability that sustains proliferative signaling (Samatar and Poulikakos, 2014; Bykov et al., 2018). Pin1 is initially identified as a regulator of mitosis and gives rise to sustaining proliferative signaling in multiple cancers.

Cyclin D1, a pivotal cell cycle regulator, promotes cell cycle progression in human cancer (Sherr, 1996). Pin1 interacts with and isomerizes cyclin D1 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, enhancing the nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1 and triggering cells into cell cycle, and promotes cell proliferation (Liou et al., 2002). Dysregulation of ERα expression also contributes to the proliferation of cancer, especially breast cancer (Brisken, 2013). Pin1 promotes ERα function through several mechanisms. Pin1 isomerizes the Ser118-Pro bond of ERα AF1 region to increase AF1 transcriptional activity, promoting the growth of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells (Rajbhandari et al., 2012). Furthermore, Pin1 can directly regulate the adjacent DNA binding domain of ERα in an allosteric manner, enhancing the DNA binding function of ERα to drive breast cancer proliferation (Rajbhandari et al., 2015).

ΔNp63s, the N-terminal truncated isoforms of p63 lacking the transactivation domain, are associated with human tumorigenesis (Chen et al., 2017). Pin1 interacts with Thr538-Pro of ΔNp63α and disrupts p63α-WWP1 interaction to inhibit the proteasomal degradation mediated by E3 ligase WWP1, promoting ΔNp63α-induced cell proliferation of human oral squamous cell carcinoma (Li et al., 2013). Moreover, Pin1 enhances the stability of BRD4 by inhibiting its ubiquitination and increasing transcriptional activity of BRD4 to promote the proliferation of gastric cancer (Hu et al., 2017). In addition, Pin1 also activates many pro-proliferative proteins to enhance tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth, including c-Myc and XPO5 (Farrell et al., 2013; Li et al., 2018).

Pin1 Evades Growth Suppressors

There are a number of tumor suppressors that negatively regulate cancer progression within cells, but cancer cells are able to bypass these barriers via various mechanisms. Several works suggest that Pin1 is an expert in injuring tumor suppressors.

The promyelocytic leukemia (PML) is a tumor suppressor involved in apoptosis and DNA damage repair. Pin1 binds and targets PML for degradation in an ERK-dependent manner by targeting Ser403 and Ser505 of PML, inducing the development of breast cancer cells (Lim et al., 2011). Moreover, KLHL20 coordinates with Pin1 and CDK1/2 to mediate hypoxia-induced PML proteasomal degradation, thereby potentiating multiple tumor hypoxia responses in human prostate cancer (Yuan et al., 2011). Furthermore, Pin1 also stabilizes the oncogenic fusion protein PML-RARα, resulting in a decreased anti-proliferative activity of ATRA in AML (Gianni et al., 2009).

Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) is an ERα inhibitor in breast cancer (Huang et al., 2012). Pin1 recognizes four phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro motifs in RUNX3 via its WW domain to suppress the transcriptional activity of RUNX3 and induce the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of RUNX3 in breast cancer (Nicole Tsang et al., 2013). KLF10 is a member of the Krüppel-like transcription factor family and acts as a tumor suppressor, mimicking the anti-proliferative effect of TGF-β in various cancer cells. Pin1 interacts with KLF10 and promotes its protein degradation, blocking the anti-proliferative function of KLF10 in cancer cells (Hwang et al., 2013). Pin1 also interacts with Fbw7 and CDK10 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and promotes their ubiquitination and degradation, which suppresses their function to trigger cell proliferation and transformation of cancer cells (Khanal et al., 2012; Min et al., 2012).

Pin1 Activates Invasion and Metastasis

Invasion and metastasis are the leading causes of death in cancer patients and remain the greatest challenges in the clinical management of cancer (Lambert et al., 2017). Mounting works have demonstrated the invasion- and metastasis-promoting function of Pin1 in human cancer.

The transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling pathway is a key player in tumor development, modulating processes including cell motility, where Smad proteins are major downstream effectors of TGF-β signaling (Lamouille et al., 2014). Phosphorylated Thr179-Pro motif of Smad2/3 interacts with Pin1 in a TGF-β-dependent manner, inducing migration and invasion via N-cadherin in prostate cancer cells (Matsuura et al., 2010). In turn, Pin1–Smad3 interaction is reduced by the inhibition of CDK-mediated Smad3 phosphorylation, leading to the suppression of triple negative breast cancer cells (Thomas et al., 2017).

Ras and STAT3 signaling has a significant impact on tumor metastasis. Pin1 binding and prolyl isomerizing of FAK cause PTP-PEST to interact with and dephosphorylate FAK Tyr397, promoting Ras-induced cell migration, invasion, and metastasis of numerous cancers (Zheng et al., 2009, 2011). Pin1 associates with STAT3 upon cytokine/growth factor stimulation to promote STAT3 transcriptional activity and target gene expression as well as recruit transcription coactivator p300, inducing epithelial–mesenchymal transition of MCF-7 cells (Lufei et al., 2007). Additionally, Pin1 enhances the invasion and metastasis of multiple cancers by activating NF-κB, BRD4, and XPO5 (Hu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Nakada et al., 2019).

Pin1 Induces Angiogenesis

Solid tumors rely on angiogenesis to supply sufficient nutrients and oxygen as well as to eliminate metabolic waste and carbon dioxide for rapidly expanded cancer cells (Chung et al., 2010). The angiogenesis is strictly controlled in vivo. Increasing evidence has illustrated that Pin1 is involved in cancer-associated angiogenesis.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is responsible for promoting the expression of many genes involved in angiogenesis (Rosmorduc and Housset, 2010). Pin1 directly interacts with HIF-1α at both exogenous and endogenous levels to stabilize the HIF-1α protein in human colon cancer cells and upregulating expression of VEGF, a major contributor to angiogenesis (Han et al., 2016). Moreover, Pin1 cooperates with KLHL20 to induce the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of PML, an inhibitor of HIF-1α-induced angiogenesis, resulting in the activation of angiogenesis in many cancers (Yuan et al., 2011). Additionally, NF-κB is also triggered by Pin1 to promote angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma (Shinoda et al., 2015). By contrast, inhibition of Pin1, through RNAi or small molecular inhibitors, significantly reduces the cancer-induced angiogenesis (Ryo et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2012), further supporting the crucial role of Pin1 in angiogenesis.

Conclusion

Pin1 is identified as a unique enzyme mediating the cis-trans isomerization of pSer/Thr-Pro motif of proteins specifically, extensively participating in the initiation and progression of many human cancers. In this article, we reviewed the existing works on the dysregulation, biological function, molecular mechanism, and significance of Pin1 in cancer cells. These works commonly report that Pin1 is an excellent target for the diagnosis and therapy of diverse cancers. Over the past two decades, diverse small-molecule Pin1 inhibitors were developed and some of them, such as ATRA, KPT-6566, arsenic trioxide, and API-1, exhibited attractive in vitro and in vivo activity toward human cancer, including acute PML, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Wei et al., 2015; Campaner et al., 2017; Kozono et al., 2018; Pu et al., 2018). However, to date, no Pin1 inhibitors are submitted to clinical trial for cancer treatment. Moreover, Pin1 is also not applied in clinical cancer diagnosis, even though Pin1 seems to be a potential cancer-specific biomarker. Therefore, more effort should be made to fill these gaps.

Despite these efforts, a number of highly relevant questions remain unanswered. First, Pin1 enrichment is precisely orchestrated by multiple regulatory mechanisms. However, the theory about the epigenetic regulation and protein decay of Pin1 is rarely studied. So, the origin of Pin1 dysregulation is not fully understood. Second, mounting data have indicated that non-coding RNAs, especially regulatory non-coding RNAs including miRNA, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), and circular RNA (circRNA), construct a complex molecular network along with numerous functional proteins to regulate cellular processes as well as canceration (Anastasiadou et al., 2018). But the relationship of Pin1 and non-coding RNAs is still unclear. Third, post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acylation, sumoylation, and glycosylation, could positively or negatively change protein activity without altering the sequences of proteins (Han et al., 2018). However, little is known on how the post-translational modifications modulate Pin1 function. We expect that the answers to these questions will be found in the coming years, pushing Pin1 toward a truly clinical application.

Author Contributions

WP, YZ, and YP wrote the manuscript, performed revisions, and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81772960 to YP, 81702980 to WP), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2019JDTD0013 to YP), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2018SCUH0018 to YP), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Sichuan University (2019SCU12037 to WP), Postdoctoral Interdisciplinary Innovative Foundation of Sichuan University (0040204153078 to WP), and the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18030 to YP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aebersold, R., and Mann, M. (2016). Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature 537, 347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature19949

Anastasiadou, E., Jacob, L. S., and Slack, F. J. (2018). Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 5–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.99

Atkinson, G. P., Nozell, S. E., Harrison, D. K., Stonecypher, M. S., Chen, D., and Benveniste, E. N. (2009). The prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates the NF-kappaB signaling pathway and interleukin-8 expression in glioblastoma. Oncogene 28, 3735–3745. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.232

Barber, K. W., Muir, P., Szeligowski, R. V., Rogulina, S., Gerstein, M., Sampson, J. R., et al. (2018). Encoding human serine phosphopeptides in bacteria for proteome-wide identification of phosphorylation-dependent interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 638–644. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4150

Barman, A., and Hamelberg, D. (2016). Coupled dynamics and entropic contribution to the allosteric mechanism of Pin1. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 8405–8415. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b02123

Bentley, D. L. (2014). Coupling mRNA processing with transcription in time and space. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 163–175. doi: 10.1038/nrg3662

Bhaskaran, N., van Drogen, F., Ng, H. F., Kumar, R., Ekholm-Reed, S., Peter, M., et al. (2013). Fbw7α and Fbw7γ collaborate to shuttle cyclin E1 into the nucleolus for multiubiquitylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 85–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00288-12

Boss, W. F., and Im, Y. J. (2012). Phosphoinositide signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 409–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103840

Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., and Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

Brisken, C. (2013). Progesterone signalling in breast cancer: a neglected hormone coming into the limelight. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 385–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc3518

Bykov, V. J. N., Eriksson, S. E., Bianchi, J., and Wiman, K. G. (2018). Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.109

Campaner, E., Rustighi, A., Zannini, A., Cristiani, A., Piazza, S., Ciani, Y., et al. (2017). A covalent PIN1 inhibitor selectively targets cancer cells by a dual mechanism of action. Nat. Commun. 8:15772. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15772

Changeux, J. P., and Christopoulos, A. (2016). Allosteric modulation as a unifying mechanism for receptor function and regulation. Cell 166, 1084–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.015

Chen, C. H., Chang, C. C., Lee, T. H., Luo, M., Huang, P., Liao, P. H., et al. (2013). SENP1 deSUMOylates and regulates Pin1 protein activity and cellular function. Cancer Res. 73, 3951–3962. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4360

Chen, J., Li, L., Zhang, Y., Yang, H., Wei, Y., Zhang, L., et al. (2006). Interaction of Pin1 with Nek6 and characterization of their expression correlation in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341, 1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.228

Chen, Y., Peng, Y., Fan, S., Li, Y., Xiao, Z. X., and Li, C. (2017). A double dealing tale of p63: an oncogene or a tumor suppressor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 965–973. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2666-y

Chen, Y., Wu, Y. R., Yang, H. Y., Li, X. Z., Jie, M. M., Hu, C. J., et al. (2018). Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 9:883. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0844-y

Cheng, C. W., and Tse, E. (2018). PIN1 in cell cycle control and cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1367. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01367

Chung, A. S., Lee, J., and Ferrara, N. (2010). Targeting the tumour vasculature: insights from physiological angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 505–514. doi: 10.1038/nrc2868

Csizmok, V., Follis, A. V., Kriwacki, R. W., and Forman-Kay, J. D. (2016). Dynamic protein interaction networks and new structural paradigms in signaling. Chem. Rev. 116, 6424–6462. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00548

Daza-Martin, M., Starowicz, K., Jamshad, M., Tye, S., Ronson, G. E., MacKay, H. L., et al. (2019). Isomerization of BRCA1-BARD1 promotes replication fork protection. Nature 571, 521–527. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1363-4

Dick, F. A., Goodrich, D. W., Sage, J., and Dyson, N. J. (2018). Non-canonical functions of the RB protein in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 442–451. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0008

Eckerdt, F., Yuan, J., Saxena, K., Martin, B., Kappel, S., Lindenau, C., et al. (2005). Polo-like kinase 1-mediated phosphorylation stabilizes Pin1 by inhibiting its ubiquitination in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36575–36583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504548200

Fan, X., He, H., Li, J., Luo, G., Zheng, Y., Zhou, J. K., et al. (2019). Discovery of 4,6-bis(benzyloxy)-3-phenylbenzofuran as a novel Pin1 inhibitor to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma via upregulating microRNA biogenesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27, 2235–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.‘.2019.04.028

Farrell, A. S., Pelz, C., Wang, X., Daniel, C. J., Wang, Z., Su, Y., et al. (2013). Pin1 regulates the dynamics of c-Myc DNA binding to facilitate target gene regulation and oncogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2930–2949. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01455-12

Fischer, G., and Aumuller, T. (2003). Regulation of peptide bond cis/transisomerization by enzyme catalysis and its implication in physiological processes. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 148, 105–150. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0011-3

Garzon, R., Marcucci, G., and Croce, C. M. (2010). Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179

Gianni, M., Boldetti, A., Guarnaccia, V., Rambaldi, A., Parrella, E., and Raska, I. Jr. et al. (2009). Inhibition of the peptidyl-prolyl-isomerase Pin1 enhances the responses of acute myeloid leukemia cells to retinoic acid via stabilization of RARalpha and PML-RARalpha. Cancer Res. 69, 1016–1026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2603

Giuli, M. V., Giuliani, E., Screpanti, I., Bellavia, D., and Checquolo, S. (2019). Notch signaling activation as a hallmark for triple-negative breast cancer subtype. J. Oncol. 2019:8707053. doi: 10.1155/2019/8707053

Han, H. J., Kwon, N., Choi, M. A., Jung, K. O., Piao, J. Y., Ngo, H. K., et al. (2016). Peptidyl prolyl isomerase PIN1 directly binds to and stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. PLoS One 11:e0147038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147038

Han, Z. J., Feng, Y. H., Gu, B. H., Li, Y. M., and Chen, H. (2018). The post-translational modification, SUMOylation, and cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 52, 1081–1094. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4280

Hanahan, D., and Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

He, Y., Chen, Y., Mooney, S. M., Rajagopalan, K., Bhargava, A., Sacho, E., et al. (2015). Phosphorylation-induced conformational ensemble switching in an intrinsically disordered cancer/testis antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 25090–25102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.658583

Hentze, M. W., Castello, A., Schwarzl, T., and Preiss, T. (2018). A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 327–341. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.130

Hermeking, H. (2012). MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrc3318

Hilton, B. A., Li, Z., Musich, P. R., Wang, H., Cartwright, B. M., Serrano, M., et al. (2015). ATR Plays a Direct Antiapoptotic Role at Mitochondria, which Is Regulated by Prolyl Isomerase Pin1. Mol. Cell 60, 35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.008

Hu, X., Dong, S. H., Chen, J., Zhou, X. Z., Chen, R., Nair, S., et al. (2017). Prolyl isomerase PIN1 regulates the stability, transcriptional activity and oncogenic potential of BRD4. Oncogene 36, 5177–5188. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.137

Huang, B., Qu, Z., Ong, C. W., Tsang, Y. H., Xiao, G., Shapiro, D., et al. (2012). RUNX3 acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by targeting estrogen receptor α. Oncogene 31, 527–534. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.252

Hwang, Y. C., Yang, C. H., Lin, C. H., Ch’ang, H. J., Chang, V. H. S., and Yu, W. C. Y. (2013). Destabilization of KLF10, a tumor suppressor, relies on thr93 phosphorylation and isomerase association. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 3035–3045. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.010

Inui, M., Martello, G., and Piccolo, S. (2010). MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrm2868

Jeronimo, C., Collin, P., and Robert, F. (2016). The RNA polymerase II CTD: the increasing complexity of a low-complexity protein domain. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 2607–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.006

Ji, S., Qin, Y., Shi, S., Liu, X., Hu, H., Zhou, H., et al. (2015). ERK kinase phosphorylates and destabilizes the tumor suppressor FBW7 in pancreatic cancer. Cell Res. 25, 561–573. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.30

Kent, L. N., and Leone, G. (2019). The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 326–338. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0143-7

Khanal, P., Yun, H. J., Lim, S. C., Ahn, S. G., Yoon, H. E., Kang, K. W., et al. (2012). Proyl isomerase Pin1 facilitates ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase 10 to induce tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 31, 3845–3856. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.548

Kim, J. A., Kim, M. R., Kim, O., Phuong, N. T., Yun, J., Oh, W. K., et al. (2012). Amurensin G inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer via Pin1 inhibition. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50, 3625–3634. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.027

Koelwyn, G. J., Quail, D. F., Zhang, X., White, R. M., and Jones, L. W. (2017). Exercise-dependent regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 620–632. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.78

Kops, O., Zhou, X. Z., and Lu, K. P. (2002). Pin1 modulates the dephosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain by yeast Fcp1. FEBS Lett. 513, 305–311. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02288-3

Kozono, S., Lin, Y. M., Seo, H. S., Pinch, B., Lian, X., Qiu, C., et al. (2018). Arsenic targets Pin1 and cooperates with retinoic acid to inhibit cancer-driving pathways and tumor-initiating cells. Nat. Commun. 9:3069. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05402-2

Lambert, A. W., Pattabiraman, D. R., and Weinberg, R. A. (2017). Emerging biological principles of metastasis. Cell 168, 670–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.037

Lamouille, S., Xu, J., and Derynck, R. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758

Lee, K. H., Lin, F. C., Hsu, T. I., Lin, J. T., Guo, J. H., Tsai, C. H., et al. (2014). MicroRNA-296-5p (miR-296-5p) functions as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer by directly targeting Pin1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.001

Lee, T. H., Chen, C. H., Suizu, F., Huang, P., Schiene-Fischer, C., Daum, S., et al. (2011a). Death-associated protein kinase 1 phosphorylates Pin1 and inhibits its prolyl isomerase activity and cellular function. Mol. Cell 42, 147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.005

Lee, T. H., Pastorino, L., and Lu, K. P. (2011b). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase Pin1 in ageing, cancer and Alzheimer disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 13:e21. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001906

Leong, K. W., Cheng, C. W., Wong, C. M., Ng, I. O., Kwong, Y. L., and Tse, E. (2017). miR-874-3p is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and negatively regulates PIN1 expression. Oncotarget 8, 11343–11355. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14526

Li, C., Chang, D. L., Yang, Z., Qi, J., Liu, R., He, H., et al. (2013). Pin1 modulates p63α protein stability in regulation of cell survival, proliferation and tumor formation. Cell Death Dis. 4:e943. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.468

Li, J., Pu, W., Sun, H. L., Zhou, J. K., Fan, X., Zheng, Y., et al. (2018). Pin1 impairs microRNA biogenesis by mediating conformation change of XPO5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 25, 1612–1624. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0065-z

Liao, P., Zeng, S. X., Zhou, X., Chen, T., Zhou, F., Cao, B., et al. (2017). Mutant p53 gains its function via c-Myc activation upon CDK4 phosphorylation at serine 249 and consequent PIN1 binding. Mol. Cell 68, 1134.e6–1146.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.006

Lim, J. H., Liu, Y., Reineke, E., and Kao, H. Y. (2011). Mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 phosphorylates and promotes Pin1 protein-dependent promyelocytic leukemia protein turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 44403–44411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.289512

Lin, S., and Gregory, R. I. (2015). MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 321–333. doi: 10.1038/nrc3932

Liou, Y. C., Ryo, A., Huang, H. K., Lu, P. J., Bronson, R., Fujimori, F., et al. (2002). Loss of Pin1 function in the mouse causes phenotypes resembling cyclin D1-null phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1335–1340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032404099

Lu, J., Getz, G., Miska, E. A., Alvarez-Saavedra, E., Lamb, J., Peck, D., et al. (2005). MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 435, 834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702

Lu, K. P., Finn, G., Lee, T. H., and Nicholson, L. K. (2007). Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 619–629. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35

Lu, K. P., Hanes, S. D., and Hunter, T. (1996). A human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase essential for regulation of mitosis. Nature 380, 544–547. doi: 10.1038/380544a0

Lu, P. J., Zhou, X. Z., Shen, M. H., and Lu, K. P. (1999). Function of WW domains as phosphoserine- or phosphothreonine-binding modules. Science 283, 1325–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1325

Lu, Z., and Hunter, T. (2014). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 in cancer. Cell Res. 9, 1033–1049. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.109

Lufei, C., Koh, T. H., Uchida, T., and Cao, X. (2007). Pin1 is required for the Ser727 phosphorylation-dependent STAT3 activity. Oncogene 26, 7656–7664. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210567

Lummis, S. C., Beene, D. L., Lee, L. W., Lester, H. A., Broadhurst, R. W., and Dougherty, D. A. (2005). Cis-trans isomerization at a proline opens the pore of a neurotransmitter-gated ion channel. Nature 438, 248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature04130

Luo, C., Hajkova, P., and Ecker, J. R. (2018). Dynamic DNA methylation: in the right place at the right time. Science 361, 1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.aat6806

Luo, M. L., Gong, C., Chen, C. H., Lee, D. Y., Hu, H., Huang, P., et al. (2014). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 acts downstream of miR200c to promote cancer stem-like cell traits in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 3603–3616. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2785

Marsolier, J., Perichon, M., DeBarry, J. D., Villoutreix, B. O., Chluba, J., Lopez, T., et al. (2015). Theileria parasites secrete a prolyl isomerase to maintain host leukocyte transformation. Nature 520, 378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature14044

Martin, E. W., Holehouse, A. S., Grace, C. R., Hughes, A., Pappu, R. V., and Mittag, T. (2016). Sequence determinants of the conformational properties of an intrinsically disordered protein prior to and upon multisite phosphorylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15323–15335. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10272

Matsuura, I., Chiang, K. N., Lai, C. Y., He, D., Wang, G., Ramkumar, R., et al. (2010). Pin1 promotes transforming growth factor-beta-induced migration and invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1754–1764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063826

Min, S. H., Lau, A. W., Lee, T. H., Inuzuka, H., Wei, S., Huang, P., et al. (2012). Negative regulation of the stability and tumor suppressor function of Fbw7 by the Pin1 prolyl isomerase. Mol. Cell 46, 771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.012

Modena, P., Lualdi, E., Facchinetti, F., Veltman, J., Reid, J. F., Minardi, S., et al. (2006). Identification of tumor-specific molecular signatures in intracranial ependymoma and association with clinical characteristics. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 5223–5233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3701

Momin, M., Yao, X. Q., Thor, W., and Hamelberg, D. (2018). Substrate sequence determines catalytic activities, domain-binding preferences, and allosteric mechanisms in Pin1. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 6521–6527. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b03819

Moretto-Zita, M., Jin, H., Shen, Z., Zhao, T., Briggs, S. P., and Xu, Y. (2010). Phosphorylation stabilizes Nanog by promoting its interaction with Pin1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13312–13317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005847107

Nakada, S., Kuboki, S., Nojima, H., Yoshitomi, H., Furukawa, K., Takayashiki, T., et al. (2019). Roles of Pin1 as a key molecule for EMT induction by activation of STAT3 and NF-κB in human gallbladder cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 907–917. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-07132-7

Namanja, A. T., Wang, X. J., Xu, B., Mercedes-Camacho, A. Y., Wilson, K. A., Etzkorn, F. A., et al. (2011). Stereospecific gating of functional motions in Pin1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019382108

Nicole Tsang, Y. H., Wu, X. W., Lim, J. S., Wee Ong, C., Salto-Tellez, M., Ito, K., et al. (2013). Prolyl isomerase Pin1 downregulates tumor suppressor RUNX3 in breast cancer. Oncogene 32, 1488–1496. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.178

Pabst, T., Mueller, B. U., Zhang, P., Radomska, H. S., Narravula, S., Schnittger, S., et al. (2001). Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha), in acute myeloid leukemia Nat. Genet. 27, 273–270. doi: 10.1038/85820

Pang, R., Yuen, J., Yuen, M. F., Lai, C. L., Lee, T. K., Man, K., et al. (2004). PIN1 overexpression and beta-catenin gene mutations are distinct oncogenic events in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 24, 4182–4186. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207493

Papaleo, E., Saladino, G., Lambrughi, M., Lindorff-Larsen, K., Gervasio, F. L., and Nussinov, R. (2016). The role of protein loops and linkers in conformational dynamics and allostery. Chem. Rev. 116, 6391–6423. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00623

Peng, J. W. (2015). Investigating dynamic interdomain allostery in Pin1. Biophys. Rev. 7, 239–249. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0171-9

Peng, Y., and Croce, C. M. (2016). The role of microRNAs in human cancer. Signal. Transd. Target Ther. 1:15004. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4

Pu, W., Li, J., Zheng, Y., Shen, X., Fan, X., Zhou, J. K., et al. (2018). Targeting Pin1 by inhibitor API-1 regulates microRNA biogenesis and suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatology 68, 547–560. doi: 10.1002/hep.29819

Pulikkan, J. A., Dengler, V., Peer Zada, A. A., Kawasaki, A., Geletu, M., Pasalic, Z., et al. (2010). Elevated PIN1 expression by C/EBPalpha-p30 blocks C/EBPalpha-induced granulocytic differentiation through c-Jun in AML. Leukemia 24, 914–923. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.37

Rajbhandari, P., Finn, G., Solodin, N. M., Singarapu, K. K., Sahu, S. C., Markley, J. L., et al. (2012). Regulation of estrogen receptor α N-terminus conformation and function by peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 445–457. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06073-11

Rajbhandari, P., Ozers, M. S., Solodin, N. M., Warren, C. L., and Alarid, E. T. (2015). Peptidylprolyl isomerase Pin1 directly enhances the DNA binding functions of estrogen receptor α. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 13749–13762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.621698

Ranganathan, R., Lu, K. P., Hunter, T., and Noel, J. P. (1997). Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell 89, 875–686. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80273-1

Rangasamy, V., Mishra, R., Sondarva, G., Das, S., Lee, T. H., Bakowska, J. C., et al. (2012). Mixed-lineage kinase 3 phosphorylates prolyl-isomerase Pin1 to regulate its nuclear translocation and cellular function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8149–8154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200804109

Rizzolio, F., Lucchetti, C., Caligiuri, I., Marchesi, I., Caputo, M., Klein-Szanto, A. J., et al. (2012). Retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor protein phosphorylation and inactivation depend on direct interaction with Pin1. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1152–1161. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.202

Rosmorduc, O., and Housset, C. (2010). Hypoxia: a link between fibrogenesis, angiogenesis, and carcinogenesis in liver disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 30, 258–270. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255355

Rustighi, A., Tiberi, L., Soldano, A., Napoli, M., Nuciforo, P., Rosato, A., et al. (2009). The prolyl-isomerase Pin1 is a Notch1 target that enhances Notch1 activation in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 133–142. doi: 10.1038/ncb1822

Rustighi, A., Zannini, A., Tiberi, L., Sommaggio, R., Piazza, S., Sorrentino, G., et al. (2013). Prolyl-isomerase Pin1 controls normal and cancer stem cells of the breast. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 99–119. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302909

Ryo, A., Liou, Y. C., Wulf, G., Nakamura, M., Lee, S. W., and Lu, K. P. (2002). PIN1 is an E2F target gene essential for Neu/Ras-induced transformation of mammary epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5281–5295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.15.5281-5295.2002

Ryo, A., Suizu, F., Yoshida, Y., Perrem, K., Liou, Y. C., Wulf, G., et al. (2003). Regulation of NF-kappaB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol. Cell 12, 1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00490-8

Ryo, A., Uemura, H., Ishiguro, H., Saitoh, T., Yamaguchi, A., Perrem, K., et al. (2005). Stable suppression of tumorigenicity by Pin1-targeted RNA interference in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 7523–7531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0457

Saegusa, M., Hashimura, M., and Kuwata, T. (2010). Pin1 acts as a modulator of cell proliferation through alteration in NF-κB but not β-catenin/TCF4 signalling in a subset of endometrial carcinoma cells. J. Pathol. 222, 410–420. doi: 10.1002/path.2773

Samatar, A. A., and Poulikakos, P. I. (2014). Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 928–942. doi: 10.1038/nrd4281

Sang, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Alvarez, A. A., Yu, B., Zhang, W., et al. (2019). CDK5-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of TRIM59 promotes macroH2A1 ubiquitination and tumorigenicity. Nat. Commun. 10:4013. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12001-2

Shi, Y. (2009). Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 139, 468–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006

Shinoda, K., Kuboki, S., Shimizu, H., Ohtsuka, M., Kato, A., and Yoshitomi, H. (2015). Pin1 facilitates NF-κB activation and promotes tumour progression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 113, 1323–1331. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.272

Steklov, M., Pandolfi, S., Baietti, M. F., Batiuk, A., Carai, P., Najm, P., et al. (2018). Mutations in LZTR1 drive human disease by dysregulating RAS ubiquitination. Science 362, 1177–1182. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7607

Sun, D., Tan, S., Xiong, Y., Pu, W., Li, J., Wei, W., et al. (2019). MicroRNA biogenesis is enhanced by liposome-encapsulated Pin1 inhibitor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics 9, 4704–4716. doi: 10.7150/thno.34588

Sun, H. L., Cui, R., Zhou, J., Teng, K. Y., Hsiao, Y. H., Nakanishi, K., et al. (2016). ERK activation globally downregulates miRNAs through phosphorylating exportin-5. Cancer Cell 30, 723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.001

Takahashi, K., Akiyama, H., Shimazaki, K., Uchida, C., Akiyama-Okunuki, H., Tomita, M., et al. (2007). Ablation of a peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1 from p53-null mice accelerated thymic hyperplasia by increasing the level of the intracellular form of Notch1. Oncogene 26, 3835–3845. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210153

Thapar, R. (2015). Roles of prolyl isomerases in RNA-mediated gene expression. Biomolecules 2, 974–999. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00590

Theuerkorn, M., Fischer, G., and Schiene-Fischer, C. (2011). Prolyl cis/trans isomerase signalling pathways in cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 4, 281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.03.007

Thomas, A. L., Lind, H., Hong, A., Dokic, D., Oppat, K., Rosenthal, E., et al. (2017). Inhibition of CDK-mediated Smad3 phosphorylation reduces the Pin1-Smad3 interaction and aggressiveness of triple negative breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle 16, 1453–1464. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1338988

Tong, Y., Ying, H., Liu, R., Li, L., Bergholz, J., and Xiao, Z. X. (2015). Pin1 inhibits PP2A-mediated Rb dephosphorylation in regulation of cell cycle and S-phase DNA damage. Cell Death Dis. 6:e1640. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.3

Tun-Kyi, A., Finn, G., Greenwood, A., Nowak, M., Lee, T. H., Asara, J. M., et al. (2011). Essential role for the prolyl isomerase Pin1 in Toll-like receptor signaling and type I interferon-mediated immunity. Nat. Immunol. 12, 733–741. doi: 10.1038/ni.2069

Verdecia, M. A., Bowman, M. E., Lu, K. P., Hunter, T., and Noel, J. P. (2000). Structural basis for phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IV WW domains. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 639–643. doi: 10.1038/77929

Wang, J. Z., Liu, B. G., and Zhang, Y. (2015). Pin1-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for breast cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 93, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.12.005

Wei, S., Kozono, S., Kats, L., Nechama, M., Li, W., Guarnerio, J., et al. (2015). Active Pin1 is a key target of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia and breast cancer. Nat. Med. 21, 457–466. doi: 10.1038/nm.3839

Werwein, E., Cibis, H., Hess, D., and Klempnauer, K. H. (2019). Activation of the oncogenic transcription factor B-Myb via multisite phosphorylation and prolyl cis/trans isomerization. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 103–121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky935

Wu, K., He, J., Pu, W., and Peng, Y. (2018). The role of exportin-5 in microRNA biogenesis and cancer. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 16, 120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.09.004

Wulf, G., Garg, P., Liou, Y. C., Iglehart, D., and Lu, K. P. (2004). Modeling breast cancer in vivo and ex vivo reveals an essential role of Pin1 in tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 23, 3397–3407. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600323

Xu, M., Cheung, C. C., Chow, C., Lun, S. W., Cheung, S. T., and Lo, K. W. (2016). Overexpression of PIN1 enhances cancer growth and aggressiveness with cyclin D1 induction in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One 11:e0156833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156833

Xu, Y. X., Hirose, Y., Zhou, X. Z., Lu, K. P., and Manley, J. L. (2003). Pin1 modulates the structure and function of human RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 17, 2765–2776. doi: 10.1101/gad.1135503

Xu, Y. X., and Manley, J. L. (2007). Pin1 modulates RNA polymerase II activity during the transcription cycle. Genes Dev. 21, 2950–2962. doi: 10.1101/gad.1592807

Yaffe, M. B., Schutkowski, M., Shen, M. H., Zhou, X. Z., Stukenberg, P. T., Rahfeld, J., et al. (1997). Sequence-specific and phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization: a potential mitotic regulatory mechanism. Science 278, 1957–1960. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1957

Yan, X., Zhu, Z., Xu, S., Yang, L. N., Liao, X. H., Zheng, M., et al. (2017). MicroRNA-140-5p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma by directly targeting the unique isomerase Pin1 to block multiple cancer-driving pathways. Sci. Rep. 7:45915. doi: 10.1038/srep45915

Yang, W., and Lu, Z. (2013). Nuclear PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect. Cell Cycle 12, 3154–3158. doi: 10.4161/cc.26182

Yang, W., Zheng, Y., Xia, Y., Ji, H., Chen, X., Guo, F., et al. (2012). ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/ncb2629

Yeh, E. S., and Means, A. R. (2007). PIN1, the cell cycle and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 381–388. doi: 10.1038/nrc2107

Yuan, W. C., Lee, Y. R., Huang, S. F., Lin, Y. M., Chen, T. Y., Chung, H. C., et al. (2011). A Cullin3-KLHL20 ubiquitin ligase-dependent pathway targets PML to potentiate HIF-1 signaling and prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 20, 214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.008

Zhang, J., Chen, M., Zhu, Y., Dai, X., Dang, F., Ren, J., et al. (2019). SPOP promotes Nanog destruction to suppress stem cell traits and prostate cancer progression. Dev. Cell 48, 329.e5–344.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.11.035

Zhang, L., Zhang, S., Yao, J., Lowery, F. J., Zhang, Q., Huang, W. C., et al. (2015). Microenvironment-induced PTEN loss by exosomal microRNA primes brain metastasis outgrowth. Nature 527, 100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature15376

Zhang, X., Zhang, B., Gao, J., Wang, X., and Liu, Z. (2013). Regulation of the microRNA 200b (miRNA-200b) by transcriptional regulators PEA3 and ELK-1 protein affects expression of Pin1 protein to control anoikis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 32742–32752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.478016

Zheng, Y., Pu, W., Li, J., Shen, X., Zhou, Q., Fan, X., et al. (2019). Discovery of a prenylated flavonol derivative as a Pin1 inhibitor to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating microRNA biogenesis. Chem. Asian J. 14, 130–134. doi: 10.1002/asia.201801461

Zheng, Y., Xia, Y., Hawke, D., Halle, M., Tremblay, M. L., Gao, X., et al. (2009). FAK phosphorylation by ERK primes ras-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation of FAK mediated by PIN1 and PTP-PEST. Mol. Cell 35, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.013

Zheng, Y., Yang, W., Xia, Y., Hawke, D., Liu, D. X., and Lu, Z. (2011). Ras-induced and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 phosphorylation-dependent isomerization of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP)-PEST by PIN1 promotes FAK dephosphorylation by PTP-PEST. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 4258–4269. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05547-11

Zhou, X. Z., and Lu, K. P. (2016). The isomerase PIN1 controls numerous cancer-driving pathways and is a unique drug target. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 463–478. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.49

Keywords: Pin1, PPIase isomerase, phosphorylation, cis-trans isomerization, cancer hallmarks

Citation: Pu W, Zheng Y and Peng Y (2020) Prolyl Isomerase Pin1 in Human Cancer: Function, Mechanism, and Significance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:168. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00168

Received: 19 December 2019; Accepted: 29 February 2020;

Published: 31 March 2020.

Edited by:

Futoshi Suizu, Hokkaido University, JapanReviewed by:

Chi-Wai Cheng, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongDonald Hamelberg, Georgia State University, United States

Shin-ichi Tate, Hiroshima University, Japan

Copyright © 2020 Pu, Zheng and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Peng, eW9uZ3BlbmdAc2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

Wenchen Pu

Wenchen Pu Yuanyuan Zheng

Yuanyuan Zheng Yong Peng

Yong Peng