94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

EDITORIAL article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med., 24 March 2025

Sec. Hypertension

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1589305

This article is part of the Research TopicPulmonary Hypertension in Atrial Septal DefectView all 5 articles

Editorial on the Research Topic

Pulmonary hypertension in atrial septal defect

This issue of Frontiers covers important topics in the area of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD). This is a complex heterogeneous population that poses major challenges in terms of diagnosis and treatment. PAH-CHD is categorised into four major clinical/pathophysiological groups: Group A (Eisenmenger syndrome, the extreme end of the spectrum with severe PAH and cyanosis), Group B (PAH with a “predominant” left-to-right shunt and no cyanosis), Group C (PAH with a “coincidental” congenital shunt) and Group D (PAH following congenital defect repair) (1). This classification is essential and clinically useful, as it separates PAH-CHD groups by pathophysiology, clinical presentation, natural history and treatment options (1). All patients should, thus, be classified into one of these groups for clinical and research purposes, though refinements in the definitions and inclusion criteria are needed to ensure that all patients can be classified correctly and managed accordingly.

In this issue, Wacker et al. propose changes to the current classification of PAH-CHD, mainly focusing on two areas. They address the issue of PAH in patients with an atrial septal defect (ASD), which has long been a clinical conundrum. ASDs allow left-to-right shunting, thus causing an increase in pulmonary blood flow and, potentially, significant volume but not pressure overload to the pulmonary circulation (though pressure may increase as a result of the excessive pulmonary blood flow, a condition recently defined as “unclassified PH” by the 2024 PH World Symposium) (2). Shear stress to pulmonary arteries is far inferior to that posed by large post-tricuspid shunts; hence, only a small minority of patients with an ASD develop pulmonary vascular disease (PVD) characterised by a rise in PVR, in contrast to patients with a large post-tricuspid shunt in whom PVD is ubiquitous within a few years after birth (3, 4). The timing of diagnosis of PAH, and the type of RV (mal-)adaptation are also more in keeping with idiopathic PAH, which may suggest an independent mechanism responsible for the development of PAH in patients with an ASD, possibly “triggered” by the shunt (3, 4). These patients are currently included in group A when the PVD is severe enough to cause shunt reversal and hypoxia, or group B (1). Wacker et al. propose that these patients should always be classified under group C, where the CHD defect is considered a “bystander”. While a move from groups A or B to group C recognises the fact that haemodynamics alone do not explain why these patients develop PAH, it completely dismisses any contribution of the shunt to its pathogenesis. Available data would, in fact, point towards a multifactorial aetiology, with the potential contribution of genetics (5–7).

Wacker et al. also address the issue of “transient” shunts, typically ventricular septal defects (VSDs) in patients with complete (d-) transposition of the great arteries (TGA) who undergo timely repair (currently arterial switch procedure), but still develop PAH. The authors propose a new group in the PAH-CHD classification i.e., “group E”, which was also endorsed by the PH World symposium (8). Indeed, even large VSDs would not be expected to cause PVD when repaired early, though significant variability exists in terms of individual susceptibility to PVD and pulmonary haemodynamics in early life (9). Moreover, it is not clear why any (isolated) VSD, without TGA, could not fulfil criteria for inclusion in the new group E. Or indeed, why a patient with PAH after timely TGA (or VSD) repair cannot fall under group D, where patients are classified if PAH is diagnosed early or late after repair, regardless of the background CHD. This debate demonstrates the potential overlap between the established PAH-CHD groups, and the need for clarification and consensus.

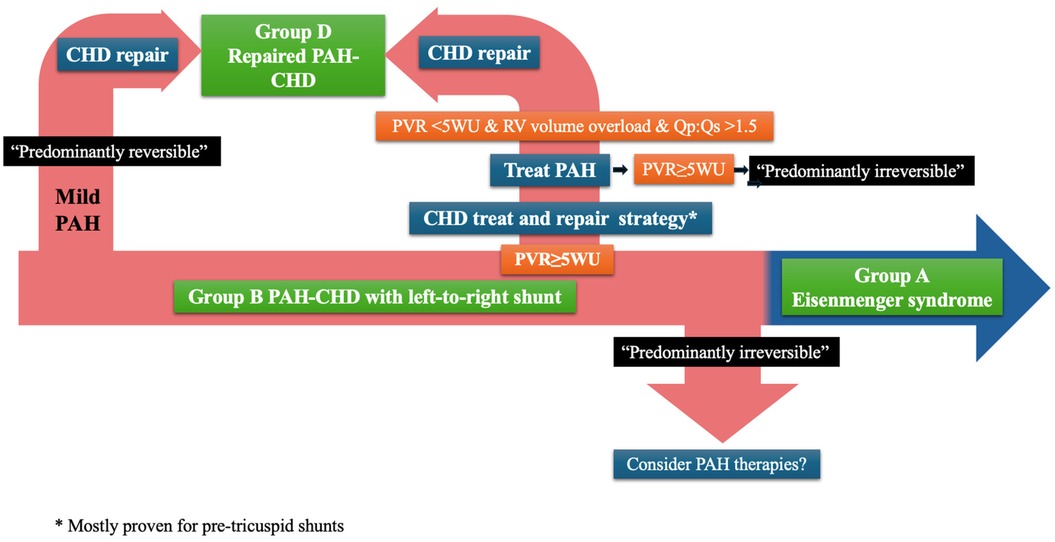

Ferrero et al. further enhance the need for clarification of the PAH-CHD classification, with a focus on group B. They provide a systematic description of the spectrum of phenotypes included in the group and propose further classification into “predominantly reversible” vs. “predominantly irreversible” PVD (Figure 1). The former includes patients previously classified as “correctable” but recognises the possibility of (at least partial) regression of PAH after repair (in patients with milder forms of PVD, as described by Heath and Edwards, and Wagenvoort) (10–12), but also the potential for residual PAH, while acknowledging the role of the “treat and repair” approach (that uses PAH therapies to “reverse” some of the PAH). “Predominantly irreversible” group B PAH-CHD identifies patients with more advanced PVD but not yet Eisenmenger syndrome (i.e., without hypoxia/cyanosis), in whom the defect should be left open and the focus should fall on managing PAH, though evidence of the use of PAH therapies is lacking.

Figure 1. Classification and management of PAH-CHD. CHD, congenital heart disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; WU, wood units; RV, right ventricle.

Both Ferrero et al. and Wacker et al. highlight the difference in presentation and pathophysiology between patients with pre- vs. post-tricuspid shunts in group B, and overall PAH-CHD, and they list several established culprit genes, including mutations in the SOX-17 and TBX4 genes. Novel, rare mutations are continuously emerging, with one such example in the paper by Wang et al. in this issue of Frontiers: they describe a chromosome 2p16.1p15 microduplication mutation in an infant with an ASD who developed significant PAH. The microduplication has been reported in another 12 cases, but this was the only case in which PAH developed, while another two cases had an isolated ASDs without PAH. Ba et al. in this issue also describe PAH in a patient with an ASD and Kabuki syndrome. Once again, the ASD was felt to be a bystander and coincidental to the development of PAH-CHD, which was rapidly progressive.

These cases highlight the overlap between ASDs and PAH. Though there is a clear association, it cannot be explained by haemodynamics alone, and genetics may provide answers. Enhancing our understanding of the role of genetics in this setting, not only provides a potential explanation for the development of PAH, but will also allow better risk stratification and genetic counselling. PAH-CHD, and CHD in general, are likely to follow the path of cardiomyopathies, a group of conditions in which genetics has risen to a crucial role in clinical management (13).

KK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IR: Writing – review & editing. KD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Endorsed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the European Reference Network on Rare Respiratory Diseases (ERN-LUNG). Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:3618–731. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237

2. Kovacs G, Bartolome S, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Gu S, Khanna D, et al. Definition, classification and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401324. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01324-2024

3. D’Alto M, Mahadevan VS. Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev. (2012) 21:328–37. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00004712

4. Nashat H, Montanaro C, Li W, Kempny A, Wort SJ, Dimopoulos K, et al. Atrial septal defects and pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Thorac Dis. (2018) 10:S2953–65. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.08.92

5. Andersen M, Lyngborg K, Moller I, Wennevold A. The natural history of small atrial septal defects: long term follow up with serial heart catheterizations. Am Heart J. (1976) 92:302–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(76)80111-1

6. Arcilla RA, Agustsson MH, Bicoff JP, Lynfield J, Weinberg M Jr, Fell EH, et al. Further observations on the natural history of isolated ventricular septal defects in infancy and childhood. Serial cardiac catheterization studies in 75 patients. Circulation. (1963) 28:560–71. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.28.4.560

7. Bloomfield DK. The natural history of ventricular septal defect in patients surviving infancy. Circulation. (1964) 29(6):914–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.29.6.914

8. Ivy D, Rosenzweig EB, Abman SH, Beghetti M, Bonnet D, Douwes JM, et al. Embracing the challenges of neonatal and paediatric pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. (2024) 64(4):2401345. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01345-2024

9. McLaughlin VV, Presberg KW, Doyle RL, Abman SH, McCrory DC, Fortin T, et al. Prognosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension*: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. (2004) 126:78S–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1_suppl.78S

10. Heath D, Edwards JE. The pathology of hypertensive pulmonary vascular disease. Circulation. (1958) 18:533–47. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.18.4.533

11. Wagenvoort CA. Morphological substrate for the reversibility and irreversibility of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. (1988) 9:7–12. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/9.suppl_J.7

12. Wagenvoort CA, Wagenvoort N. Primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. (1970) 42:1163–84. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.42.6.1163

13. Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, Arbustini E, Barriales-Villa R, Basso C, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies: developed by the task force on the management of cardiomyopathies of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:3503–626. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194

Keywords: genetics, congenital heart defect (CHD), atrial septal defect, pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease

Citation: Krishnathasan K, Rafiq I and Dimopoulos K (2025) Editorial: Pulmonary hypertension in atrial septal defect. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1589305. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1589305

Received: 7 March 2025; Accepted: 11 March 2025;

Published: 24 March 2025.

Edited and Reviewed by: Guido Iaccarino, Federico II University Hospital, Italy

Copyright: © 2025 Krishnathasan, Rafiq and Dimopoulos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: K. Dimopoulos, ay5kaW1vcG91bG9zMDJAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.