- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medical Translational Sciences, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy

- 2Department of Advanced Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy

- 3Department of Human Sciences and Promotion of the Quality of Life, San Raffaele Roma Open University, Rome, Italy

- 4Departmental Unit of Electrophysiology, Evaluation and Treatment of Arrhythmias, Monaldi Hospital, Naples, Italy

- 5Department of Anesthesiology, Monaldi Hospital, Napoli, Italy

- 6Department of Cardiology, AORN dei Colli-Monaldi Hospital, Naples, Italy

Introduction: Subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD) is an alternative to a transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (TV-ICD) system in selected patients not in need of pacing or resynchronization. Currently, little is known about the effectiveness and safety of S-ICD in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM). The aim of our study was to describe the clinical features and the drivers of S-ICD implantation among patients with ICM, as well as the clinical performance of S-ICD vs. TV-ICD among this subset of patients during a long-term follow-up.

Materials and methods: All ICM patients with both S-ICD and TV-ICD implanted and followed at Monaldi Hospital from January 1, 2015, to January 1, 2024, were evaluated; among them, only ICD recipients with no pacing indication were included. We collected clinical and anamnestic characteristics, as well as ICD inappropriate therapies, ICD-related complications and infections.

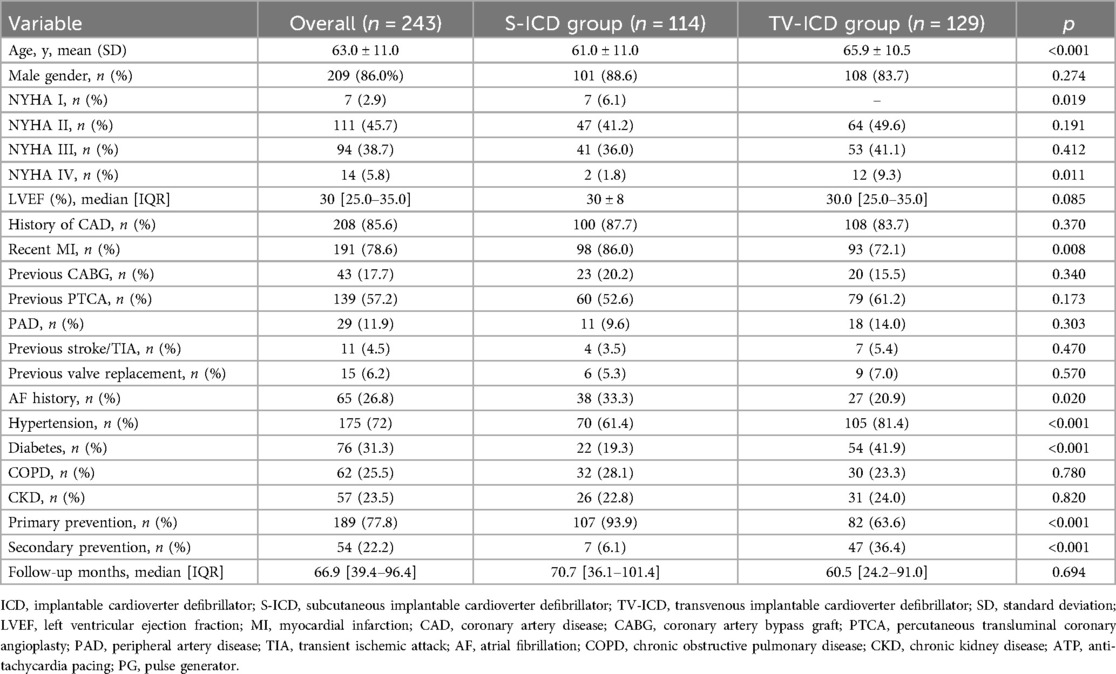

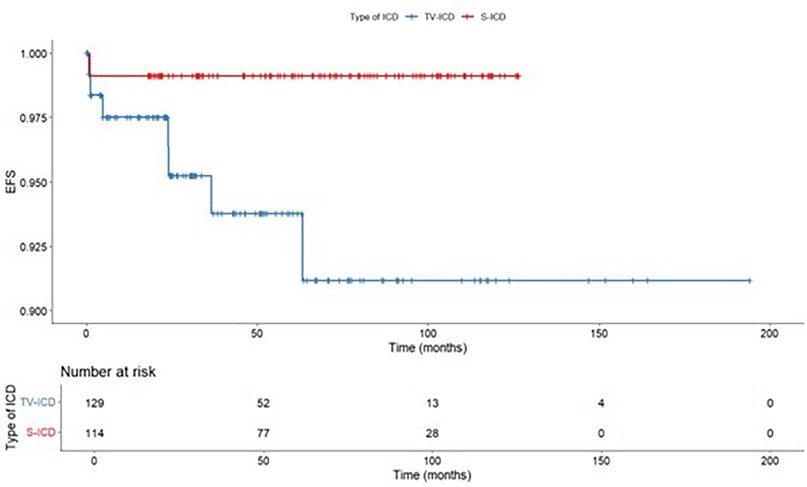

Results: A total of 243 ICM patients (mean age 63.0 ± 11.0, male 86.0%) implanted with TV-ICD (n: 129, 53.1%) and S-ICD (n: 114, 46.9%) followed at our center for a median follow-up of 66.9 [39.4–96.4] months were included in the study. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed no significant difference in the risk of inappropriate ICD therapies (log-rank p = 0.137) or ICD-related complications (log-rank p = 0.055) between S-ICD and TV-ICD groups. TV-ICD patients showed a significantly higher risk of ICD-related infections compared to those in the S-ICD group (log-rank p = 0.048). At multivariate logistic regression analysis, the only independent predictors of S-ICD implantation were female sex [OR: 52.62; p < 0.001] and primary prevention [OR: 17.60; p < 0.001].

Conclusions: Among patients with ICM not in need of pacing or resynchronization (CRT), the decision to implant an S-ICD was primarily influenced by female gender and primary prevention indications. No significant differences in inappropriate ICD therapies and complications were found; in contrast, the S-ICD group showed a numerically reduced risk of ICD-related infections.

Introduction

Ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) is currently defined a myocardial disease characterized by impaired systolic left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) and represents the most common cause of heart failure (1). Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is effective for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) among ICM patients (2). Subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD) is an alternative to a transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (TV-ICD) system in selected patients not in need of pacing or CRT (3–10).

Currently, no sub-analysis of randomized clinical trials including ICM patients are available and real-world data comparing the effectiveness and safety of S-ICD in this clinical setting are lacking (11). The aim of our study was to describe the clinical features and the drivers of S-ICD implantation among patients with ICM, as well as the clinical performance of S-ICD vs. TV-ICD among this subset of patients during a long-term follow-up.

Materials and methods

This is a single-center, retrospective observational study. Data for this study were sourced from Monaldi Hospital Rhythm Registry (NCT05072119), which includes all patients who underwent ICD implantation and followed up at our Institution through both outpatient visits, every 3–6 months, and remote device monitoring. During the follow-up, the occurrence and the causes of inappropriate and appropriate ICD therapies, and ICD-related complications were assessed and recorded in the electronic data management system. For the present analysis, we selected all consecutive patients with ICM who received subcutaneous (S-ICD Group) and transvenous (TV-ICD Group) in primary or secondary prevention, from January 1, 2015 to January 1, 2024, according to the European guidelines and recommendations available at the time of implantation (12, 13). Only patients not in need of pacing or CRT that underwent TV-ICD implantation were included in the analysis. At our center, the choice between S-ICD and TV-ICD is guided by a shared decision-making process, which includes both implanting physician and patient preference. All S-ICDs were implanted under deep sedation and using the intermuscular two-incision technique (14, 15). The local institutional review boards approved the study (ID 553-19), and all patients provided written informed consent for data storage and analysis.

ICD programming

The programming of the parameters for the detection of ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) was done according to the guideline's recommendations at the time of the implant. We routinely activate for primary prevention only one VF zone (30 intervals at 250 bpm) and for secondary prevention two windows of detection (VF: 30 intervals at 250 bpm; VT2: 30 intervals at 187 bpm or 10–20 bpm < VT rate) with shocks and up to three anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) and eight shocks in VT2 zone. S-ICD devices were programmed with a conditional zone, between 200 and 250 bpm, and a shock zone > 250 bpm. The programmed sensing vector was primary (60.3%) or secondary (37.5%) for most patients and alternate in small percentage of cases (2.2%).

Outcomes

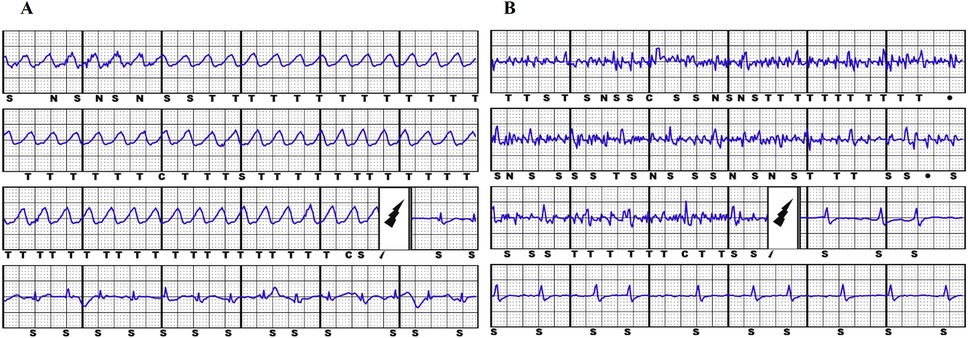

The primary study endpoints were ICD inappropriate therapies, defined as ATP and/or shocks for conditions other than VT/VF (Figure 1); ICD-related complications, defined as peri-procedural implantation complications, pulse generator or lead-related complications, infections which required complete removal of the system. The secondary endpoints were the clinical variables associated to S-ICD implantation.

Figure 1. Example of appropriate S-ICD shock due to ventricular fibrillation (panel A) and inappropriate S-ICD shock due to muscular noise (panel B).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were expressed as number and percentage, whereas continuous variables were expressed as either median [interquartile range (IQR)] or mean ± standard deviation (SD), based on their distribution. Between-group differences for categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test, with Yates' correction applied where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using either the parametric Student's t-test or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, depending on their distribution. Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to evaluate the main outcomes of interest, stratified by ICD type, with survival curves compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards univariate and multivariate regression was used to assess the relationship between the variables of interest and the risk of adverse outcomes. Additionally, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify baseline characteristics associated with S-ICD implantation. All analyses were performed using RStudio software (RStudio, Boston, MA).

Results

Study population

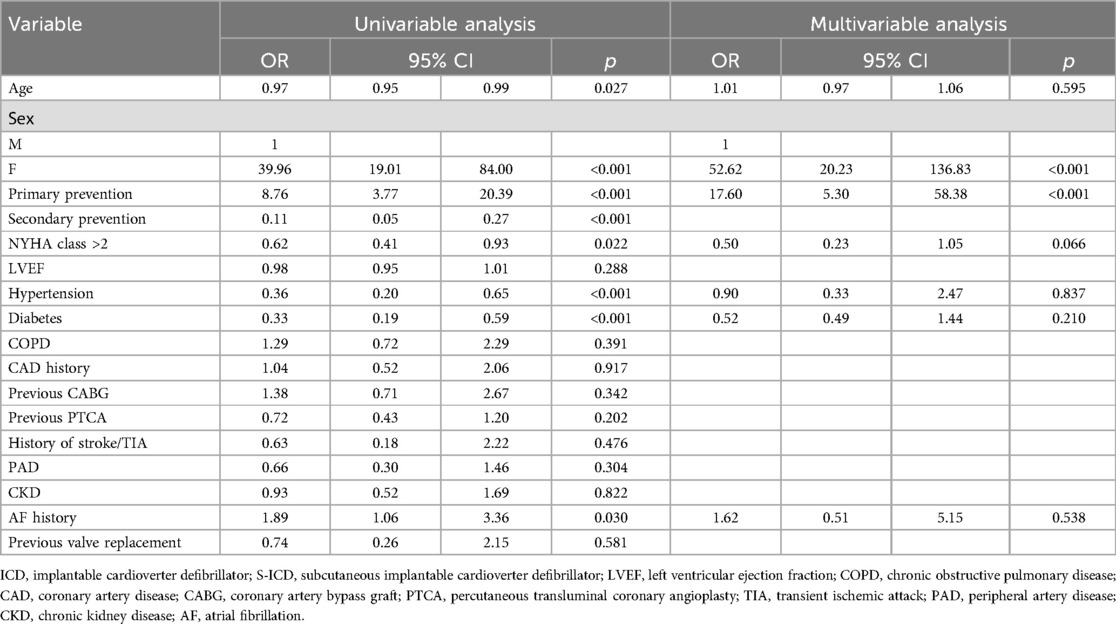

A total of 243 ICM patients (mean age 63.0 ± 11.0, male 86.0%) with TV-ICD (n: 129, 53.1%) and S-ICD (n: 114, 46.9%) followed at our center for a median follow-up of 66.9 [39.4–96.4] months were included in the study. The indication for ICD implantation was primary prevention in 189 patients (77.8%) and secondary prevention in 54 patients (22.2%). S-ICD patients were younger (61.0 ± 11.0 vs. 65.9 ± 10.5 years, p < 0.001) and showed less frequently hypertension (61.4% vs. 81.4%, p = <0.001) and diabetes (19.3% vs. 41.9%, p = <0.001). The baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. At multivariate logistic regression analysis, the only independent predictors of S-ICD implantation were female sex [odds ratio (OR): 52.62; 95% confidence interval (CI) 20.23–136.83; p < 0.001] and primary prevention [OR: 17.60; 95% CI 5.30–58.38; p < 0.001] (Table 2). Regarding S-ICD group, no patients required device extraction due to the need for pacing or CRT.

Clinical outcomes

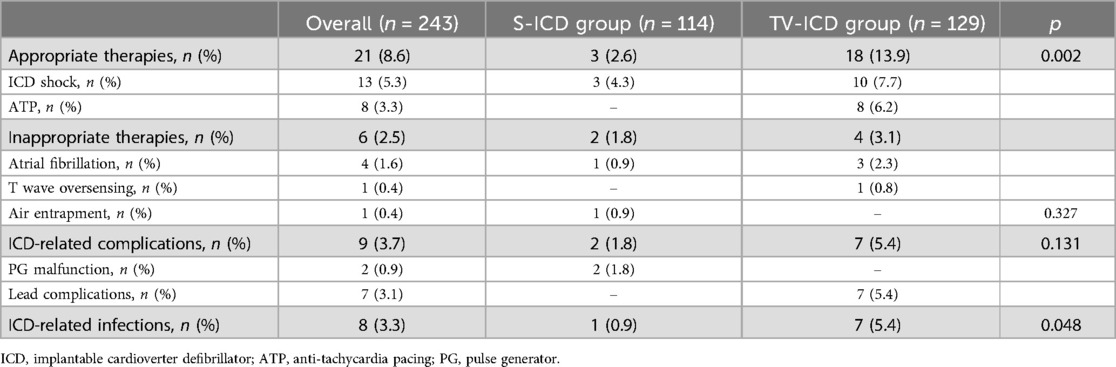

Among our study population, ICD inappropriate therapies were experienced by 6 patients (2.5%); of them, 2 (1.6%) in S-ICD group and 4 (3.5%) in the TV-ICD group (p = 0.327) (Table 3).

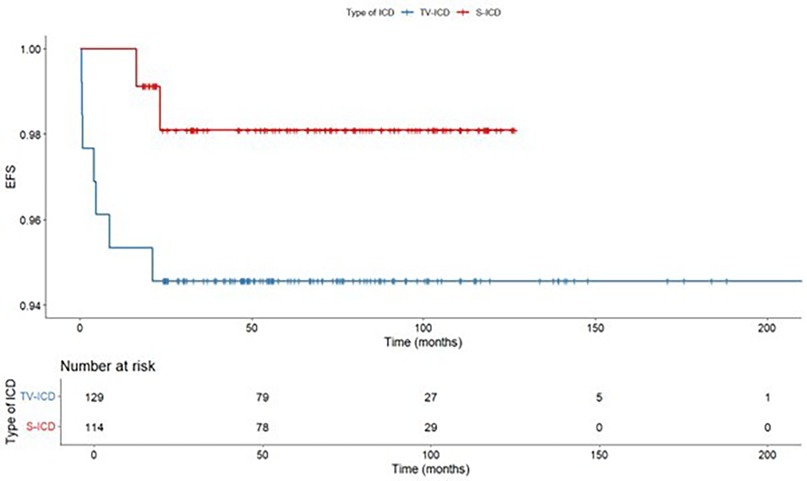

The annual incident rate of ICD inappropriate therapies over 5 years was 0.4%. The Kaplan–Meyer analysis did not show a significantly different risk of inappropriate ICD therapies between the two subgroups (log-rank p = 0.319) (Figure 2). At Cox multivariate analysis no patients' clinical characteristic, including S-ICD, was associated with inappropriate ICD therapies (Supplementary Table S1).

ICD related complications requiring surgical revision occurred in 9 patients (3.7%), of them, 2 (1.8%) in S-ICD group and 7 (5.4%) in the TV-ICD group (p = 0.131) (Table 3). S-ICD complications were exclusively attributed to PG malfunctions, whereas all TV-ICD complications were associated with lead-related issues. The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of ICD related complications between the two subgroups (log-rank p = 0.137) (Figure 3). At Cox multivariate analysis no patients' clinical characteristics, including S-ICD, was associated with ICD complications (Supplementary Table S2).

ICD-related infections occurred in 8 patients (3.3%), of them, 1 (0.9%) in S-ICD group and 7 (5.4%) in the TV-ICD group (p = 0.048) (Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show a significantly different risk of ICD-related infections between the two subgroups (log-rank p = 0.055) (Figure 4).

All infected TV-ICD patients underwent lead extraction and subsequent S-ICD implantation; in two cases, a combined pacemaker leadless implantation was performed. The infected S-ICD patient was not re-implanted due to the absence of indication at clinical re-assessment after extraction.

At Cox multivariate analysis, a history of stroke/TIA [hazard ratio (HR) 7.77; 95% CI: 1.39–43.42; p = 0.020] and previous valve replacement (HR: 5.84; 95% CI: 1.25–27.28; p = 0.025) were independently associated with ICD infections, whereas S-ICD implantation was not (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

The main findings of our study are as follows: (1) Among patients with ICM, no significant differences were observed in inappropriate ICD therapies or ICD-related complications between S-ICD and TV-ICD. However, TV-ICD was associated with a numerically higher, though not statistically significant, rate of ICD-related infections during follow-up compared to S-ICD. (2) Female gender and primary prevention were the only clinical factors independently associated with S-ICD implantation in ICM patients.

S-ICD is an established therapy for SCD prevention and an alternative to TV-ICD system in selected patients (1, 2). S-ICD showed a non-inferiority vs. TV-ICD for device-related complications or inappropriate shocks in patients with an indication for defibrillator therapy and not in need of pacing or CRT (3–10). Recently, two real-world registries showed S-ICD may be a valuable alternative to TV-ICD in patients with cardiomyopathies (16) and in those with heart failure (17); however, the potential risk of IAS, mainly due to non-cardiac oversensing, was not negligible.

Among different studies comparing the efficacy and safety of S-ICD vs. TV-ICD, the percentage of patients with ICM ranged from 27% to 67% (5, 9). No sub-analysis of randomized clinical trials including this subset of patients are currently available. In the EFFORTLESS registry (13), which included 28.1% of S-ICD patients with ICM, the ischemic etiology was an independent predictor of treated episodes for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia at five years. In a single-center retrospective study by Willy et al. (18) which included 45 patients with ischemic heart disease and S-ICD for primary or secondary prevention, no change to transvenous ICDs for anti-tachycardia pacing delivery was necessary, moreover, no surgical revision was required, and no system-related infections were reported during a mean follow-up of 2.5 ± 8.3 months. In an international observational study on 1,698 patients, of whom 31.7% had ischemic cardiomyopathy, no differences emerged between ischemic and non-ischemic patients regarding ICD appropriate shocks and device-related complications. However, ischemic patients showed a reduced risk of inappropriate ICD therapies (19).

Our data confirms in a large population the previous findings about the safety of S-ICD in patients with ICM. Among our study population, the cumulative incidence of inappropriate therapies was lower than previously reported (19, 20), mainly due to our strategy to optimize the TV-ICD programming at each follow-up visit or based on remote monitoring reporting. Moreover, the generation S-ICD systems implanted at our Institution have an additional high-pass filter to the sensing methodology, called SmartPass (SP), designed to reduce the inappropriate therapies (21, 22).

Among S-ICD patients, the air entrapment has been recently described as undetected cause of inappropriate therapies in the early post-procedural period (23–25). Regarding the complications, we observed a numerically reduction of overall ICD-related complications in the S-ICD group, mainly driven by less frequent lead-related complications. The low annual rate of ICD infections at our Institution confirms the reduced number of infections in high implantation volume centers (26); as we expected, the TV-ICD group showed a numerically higher incidence compared to the S-ICD group. These data may be explained by the multiprongest strategies we apply to reduce the cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) infection, including the proper patients' selection, the basic preparation of the operating theater; the efforts to reduce hematoma formation; the use of an antibiotic-impregnated mesh envelope or antimicrobial solution during implantation in high-risk individuals. This evidence is of pivotal importance since systemic infections represent an important predictor of death for all causes, regardless of the result of the extraction procedure (27).

Among ICM patients, our data suggest a tendency to consider S-ICD the preferred choice for female patients and those in primary prevention. No data are available about the gender impact on the choice of ICD type. However, previous studies support for gender disparities in quality of life among ICD patients, with female patients reporting poorer mental health and more anxiety (28–31).

This preference for S-ICD in female patients may be explained by efforts to reduce the aesthetical impact of the TV-ICD wound in the anterior subclavian position, preferring instead for the more posterior and cranial placement of the S-ICD, where it minimally interferes with the position of the bra (32). Female S-ICD recipients experienced less likely appropriate ICD therapy, with similar risk of device-related complications compared to males; moreover, they were more likely to be at a low-risk of ventricular arrhythmias conversion failure (33).

Among our study population, the history of stroke/TIA and previous valve replacement were independently associated with ICD infections. According to the current guidelines, patients with prosthetic heart valves arec onsidered at high risk of infective endocardites (IE) and those receiving a CIED are considered at an intermediary IE risk (34). The combination of undergoing an prosthetic valve replacemente and having or getting a CIED may result in an even higher risk of IE, independently from the timing of the CIED implantation (35).

The evidence that previous stroke/TIA is a risk factor for CIED infection might be related to the type and magnitude of loss of function following the acute event. In a systematic review by Martino et al. the dysphagia occurs in 37%–78% of stroke patients and increases the risk for pneumonia 3-fold and 11-fold in patients with confirmed aspiration (36). In addition, a stroke may lead to an induced immunodepression, a systemic anti-inflammatory response that is related to susceptibility to infection (37, 38).

In clinical practice, the use of S-ICD in patients with ICM who do not require pacing or CRT remains challenging. This is primarily due to concerns about the potential for sustained VT that may require ATP or the risk of incident bradyarrhythmias that could necessitate pacing (39). However, it should be noted that only 15–20% of patients experienced a high rate of monomorphic VT during the first year after the implant with a subsequent risk is 1.8%/year; moreover, the proportion of both monomorphic VT and successful ATP was comparable between patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (40). Finally, no studies have still addressed whether the efficacy of ATP translates into hard outcomes such as mortality benefits, prevention of inappropriate shocks, and risks of pro-arrhythmias (41). Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy had significantly less inappropriate therapy compared to patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and appear to be appropriate patients for this type of device (39, 40). Moreover, patients with ischemic heart disease are particularly exposed to the risk of CIED-related complications due to their multiple comorbidities. This highlights the need for a patient-centered, tailored approach to device selection, rather than relying solely on the etiology of cardiomyopathy (ischemic vs. non-ischemic). Such an approach should consider not only the potential mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias but also other patient-specific factors, including susceptibility to systemic infections, the concomitant use of other cardiac devices (42) and the risk of long-term device-related complications.

In the clinical contest of TV-ICD explanation, S-ICD has proven to offer a viable alternative for both infection and lead failure, since the S-ICD recipient mortality did not appear to be correlated with the presence of a prior infection, S-ICD therapy (appropriate or inappropriate), or S-ICD complications but rather to worsening of HF or other comorbidities (43, 44). Moreover, advancements in modular pacing-defibrillator systems offer promising solutions for patients requiring antitachycardia or bradycardia pacing. A recently developed system combines a leadless pacemaker with a subcutaneous ICD, enabling wireless communication to provide both pacing modalities. Early data have demonstrated freedom from major complications related to the leadless pacemaker and its communication with the S-ICD. Furthermore, at six months, the majority of patients achieved adequate pacing thresholds, with a pulse width of 0.4 ms and a pacing voltage of up to 2.0 V (30). This innovation underscores the potential for further improving outcomes in this complex patient population by combining the benefits of S-ICD with advanced pacing technologies (45).

Study limitations

Our results should be interpreted considering the limitations related to the study's retrospective, observational, and single-center nature; however, it is the largest study evaluating the clinical performance of S-ICD vs. TV-ICD among patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy not in need of pacing or CRT. The findings of our study may be influenced by the high level of experience in ICD implantation and management at our center. The follow-up duration is relatively short, approximately 65 months; however, it remains the longest observational study including this subset of patients. Additionally, no data on pharmacological therapies or biomarkers were collected at the time of outcome events (46). An additional limitation is the small number of patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation (4 in the TV-ICD group and 1 in the S-ICD group), which precluded meaningful analysis of its impact. This contrasts with findings from Schiavone et al., who reported improved long-term outcomes, including reduced arrhythmic events and cardiovascular mortality, in S-ICD carriers undergoing ablation (47). Furthermore, the associations between female sex and primary prevention as independent predictors of S-ICD implantation warrant further investigation in a multicenter study, ideally including comparisons with patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, to better assess their broader applicability and clinical significance.

Conclusions

In our clinical practice, the decision to implant an S-ICD in ICM patients was mainly driven by female sex and primary SCD prevention. No significant difference in inappropriate ICD therapies or ICD-related complications has been observed between TV-ICD and S-ICD; even if these latter showed a numerically lower risk of ICD-related infections. Our findings suggest that S-ICD may be a viable alternative to TV-ICD in ICM patients; however further prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these results and explore their broader applicability.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria, “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale “Ospedale dei Colli”; approval ID 553-19. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

VR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VB: Writing – review & editing. AR: Writing – review & editing. EA: Writing – review & editing. AP: Writing – review & editing. ND: Writing – review & editing. AG: Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing. AD: Writing – review & editing. PG: Writing – review & editing. ED: Writing – review & editing. GN: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

All authors confirm that the following manuscript is a transparent and honest account of the reported research. This research is related to a previous study by the same authors titled “Device-Related Complications and Inappropriate Therapies Among Subcutaneous vs. Transvenous Implantable Defibrillator Recipients: Insight Monaldi Rhythm Registry”. The previous study was performed on all patients who received an ICD implantation during the study period and the current submission is focusing on patients with ICM. Additionally, the follow-up period has been extended, providing more comprehensive insights into long-term outcomes. The study follows the methodology explained in the previous publication, including patient selection criteria, data collection processes, and statistical analyses, with modifications to account for the specific focus on ischemic cardiomyopathy and the extended follow-up period.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1539125/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Del Buono MG, Moroni F, Montone RA, Azzalini L, Sanna T, Abbate A. Ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2022) 24(10):1505–15. doi: 10.1007/s11886-022-01766-6

2. Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(40):3997–4126. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262

3. Boersma LV, El-Chami MF, Bongiorni MG, Burke MC, Knops RE, Aasbo JD, et al. Understanding outcomes with the EMBLEM S-ICD in primary prevention patients with low EF study (UNTOUCHED): clinical characteristics and perioperative results. Heart Rhythm. (2019) 16(11):1636–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.04.048

4. Knops RE, Olde Nordkamp LRA, Delnoy PHM, Boersma LVA, Kuschyk J, El-Chami MF, et al. Subcutaneous or transvenous defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383(6):526–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915932

5. Brouwer TF, Yilmaz D, Lindeboom R, Buiten MS, Olde Nordkamp LR, Schalij MJ, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of subcutaneous versus transvenous implantable defibrillator therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 68(19):2047–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.044

6. Boersma L, Barr C, Knops R, Theuns D, Eckardt L, Neuzil P, et al. Implant and midterm outcomes of the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry: the EFFORTLESS study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70(7):830–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.040

7. Rordorf R, Casula M, Pezza L, Fortuni F, Sanzo A, Savastano S, et al. Subcutaneous versus transvenous implantable defibrillator: an updated meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. (2021) 18(3):382–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.11.013

8. Russo V, Rago A, Ruggiero V, Cavaliere F, Bianchi V, Ammendola E, et al. Device-related complications and inappropriate therapies among subcutaneous vs. transvenous implantable defibrillator recipients: insight monaldi rhythm registry. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:879918. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.879918

9. Russo V, Ciabatti M, Brunacci M, Dendramis G, Santobuono V, Tola G, et al. Opportunities and drawbacks of the subcutaneous defibrillator across different clinical settings. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2023) 21(3):151–64. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2023.2184350

10. Russo V, Caturano A, Guerra F, Migliore F, Mascia G, Rossi A, et al. Subcutaneous versus transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator among drug-induced type-1 ECG pattern Brugada syndrome: a propensity score matching analysis from IBRYD study. Heart Vessels. (2023) 38(5):680–8. doi: 10.1007/s00380-022-02204-x

11. Pedersen CT, Kay GN, Kalman J, Borggrefe M, Della-Bella P, Dickfeld T, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. (2014) 11(10):e166–96. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.024

12. Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. (2015) 36(41):2793–867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316

13. Lambiase PD, Barr C, Theuns DA, Knops R, Neuzil P, Johansen JB, et al. Worldwide experience with a totally subcutaneous implantable defibrillator: early results from the EFFORTLESS S-ICD registry. Eur Heart J. (2014) 35(25):1657–65. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu112

14. Migliore F, Pittorru R, Giacomin E, Dall'Aglio PB, Falzone PV, Bertaglia E, et al. Intermuscular two-incision technique for implantation of the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a 3-year follow-up. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2023). doi: 10.1007/s10840-023-01478-z

15. Botto GL, Ziacchi M, Nigro G, D'Onofrio A, Dello Russo A, Francia P, et al. Intermuscular technique for implantation of the subcutaneous implantable defibrillator: a propensity-matched case-control study. Europace. (2023) 25(4):1423–31. doi: 10.1093/europace/euad028

16. Migliore F, Biffi M, Viani S, Pittorru R, Francia P, Pieragnoli P, et al. Modern subcutaneous implantable defibrillator therapy in patients with cardiomyopathies and channelopathies: data from a large multicentre registry. Europace. (2023) 25(9):euad239. doi: 10.1093/europace/euad239

17. Schiavone M, Gasperetti A, Laredo M, Breitenstein A, Vogler J, Palmisano P, et al. Inappropriate shock rates and long-term complications due to subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillators in patients with and without heart failure: results from a multicenter, international registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2023) 16(1):e011404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.122.011404

18. Willy K, Reinke F, Bögeholz N, Ellermann C, Rath B, Köbe J, et al. The role of entirely subcutaneous ICD™ systems in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. (2020) 75(5):567–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.10.005

19. Gasperetti A, Schiavone M, Milstein J, Compagnucci P, Vogler J, Laredo M, et al. Differences in underlying cardiac substrate among S-ICD recipients and its impact on long-term device-related outcomes: real-world insights from the iSUSI registry. Heart Rhythm. (2024) 21(4):410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.12.007

20. Sedláček K, Ruwald AC, Kutyifa V, McNitt S, Thomsen PEB, Klein H, et al. The effect of ICD programming on inappropriate and appropriate ICD therapies in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy: the MADIT-RIT trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2015) 26(4):424–33. doi: 10.1111/jce.12605

21. Theuns DAMJ, Brouwer TF, Jones PW, Allavatam V, Donnelley S, Auricchio A, et al. Prospective blinded evaluation of a novel sensing methodology designed to reduce inappropriate shocks by the subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm. (2018) 15(10):1515–22. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.011

22. Francia P, Ziacchi M, De Filippo P, Viani S, D'Onofrio A, Russo V, et al. Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator eligibility according to a novel automated screening tool and agreement with the standard manual electrocardiographic morphology tool. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2018) 52(1):61–7. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0326-2

23. Iavarone M, Rago A, Nigro G, Golino P, Russo V. Inappropriate shocks due to air entrapment in patients with subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: a meta-summary of case reports. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2022) 45(10):1210–5. doi: 10.1111/pace.14584

24. Iavarone M, Russo V. Air entrapment as a cause of S-ICD inappropriate shocks. Heart Rhythm. (2022) 19(10):1751–2. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2022.05.012

25. Iavarone M, Ammendola E, Rago A, Russo V. Air entrapment as a cause of early inappropriate shocks after subcutaneous defibrillator implant: a case series. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. (2023) 23(3):84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2023.02.001

26. Tarakji KG, Mittal S, Kennergren C, Corey R, Poole JE, Schloss E, et al. Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380(20):1895–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901111

27. Tarakji KG, Wazni OM, Harb S, Hsu A, Saliba W, Wilkoff BL. Risk factors for 1-year mortality among patients with cardiac implantable electronic device infection undergoing transvenous lead extraction: the impact of the infection type and the presence of vegetation on survival. Europace. (2014) 16:1490–5. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu147

28. Brouwers C, van den Broek KC, Denollet J, Pedersen SS. Gender disparities in psychological distress and quality of life among patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2011) 34:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03084.x

29. Bilge AK, Ozben B, Demircan S, Cinar M, Yilmaz E, Adalet K. Depression and anxiety status of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator and precipitating factors. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2006) 29:619–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00409.x

30. Habibovic M, van den Broek KC, Theuns D, Jordaens L, Alings M, van der Voort PH, et al. Gender disparities in anxiety and quality of life in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Europace. (2011) 13:1723–30. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur252

31. Nesti M, Russo V, Palamà Z, Panchetti L, Garibaldi S, Startari U, et al. The subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: a patient perspective. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(20):6675. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206675

32. van der Stuijt W, Quast ABE, Baalman SWE, Olde Nordkamp LRA, Wilde AAM, Knops RE. Improving the care for female subcutaneous ICD patients: a qualitative study of gender-specific issues. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 317:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.05.091

33. Schiavone M, Gasperetti A, Vogler J, Compagnucci P, Laredo M, Breitenstein A, et al. Sex differences among subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients: a propensity-matched, multicentre, international analysis from the i-SUSI project. Europace. (2024) 26(5):euae115. doi: 10.1093/europace/euae115

34. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). endorsed by: european association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. (2015) 36(44):3075–128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

35. Østergaard L, Valeur N, Bundgaard H, Gislason G, Torp-Pedersen C, Eske Bruun N, et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device and associated risk of infective endocarditis in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. Europace. (2018) 20(10):e164–70. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux360

36. Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Diamant N, Speechley M, Teasell R. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. (2005) 36:2756–63. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190056.76543.eb

37. Chamorro A, Amaro S, Vargas M, Obach V, Cervera A, Torres F, et al. Interleukin 10, monocytes and increased risk of early infection in ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2006) 77:1279–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100800

38. Haeusler KG, Schmidt WU, Fohring F, Meisel C, Helms T, Jungehulsing GJ, et al. Cellular immunodepression preceding infectious complications after acute ischemic stroke in humans. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2008) 25:50–8. doi: 10.1159/000111499

39. Bloch Thomsen PE, Jons C, Raatikainen MJ, Moerch Joergensen R, Hartikainen J, Virtanen V, et al. Long-term recording of cardiac arrhythmias with an implantable cardiac monitor in patients with reduced ejection fraction after acute myocardial infarction: the cardiac arrhythmias and risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction (CARISMA) study. Circulation. (2010) 122(13):1258–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902148

40. Cheng A, Joung B, Brown ML, Koehler J, Lexcen DR, Sanders P, et al. Characteristics of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and their susceptibility to antitachycardia pacing termination in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a patient-level meta-analysis of three large clinical trials. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2020) 31(10):2720–6. doi: 10.1111/jce.14688

41. Ho G, Birgersdotter-Green U. Antitachycardia pacing: a worthy cause? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2020) 31:2727–9. doi: 10.1111/jce.14684

42. Migliore F, Schiavone M, Pittorru R, Forleo GB, De Lazzari M, Mitacchione G, et al. Left ventricular assist device in the presence of subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator: data from a multicenter experience. Int J Cardiol. (2024) 400:131807. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131807

43. Russo V, Viani S, Migliore F, Nigro G, Biffi M, Tola G, et al. Lead abandonment and subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (S-ICD) implantation in a cohort of patients with ICD lead malfunction. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:692943. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.692943

44. Giacomin E, Falzone PV, Dall'Aglio PB, Pittorru R, De Lazzari M, Vianello R, et al. Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator after transvenous lead extraction: safety, efficacy and outcome. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2022) 400. doi: 10.1007/s10840-022-01293-y

45. Knops RE, Lloyd MS, Roberts PR, Wright DJ, Boersma LVA, Doshi R, et al. A modular communicative leadless pacing-defibrillator system. N Engl J Med. (2024) 391(15):1402–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2401807

46. D'Onofrio A, Russo V, Bianchi V, Cavallaro C, Leonardi S, De Vivo S, et al. Effects of defibrillation shock in patients implanted with a subcutaneous defibrillator: a biomarker study. Europace. (2018) 20(FI2):f233–9. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux330

47. Schiavone M, Gasperetti A, Compagnucci P, Vogler J, Laredo M, Montemerlo E, et al. Impact of ventricular tachycardia ablation in subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator carriers: a multicentre, international analysis from the iSUSI project. Europace. (2024) 26(4):euae066. doi: 10.1093/europace/euae066

Keywords: subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD), transvenous ICD, complications, infections, inappropriate shock therapy, ischemic cardiomyopathy

Citation: Russo V, Caturano A, Bianchi V, Rago A, Ammendola E, Papa AA, Della Cioppa N, Guarino A, Masi A, D'Onofrio A, Golino P, Di Lorenzo E and Nigro G (2025) Clinical performance of subcutaneous vs. transvenous implantable defibrillator in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: data from Monaldi Rhythm Registry. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1539125. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1539125

Received: 10 December 2024; Accepted: 5 February 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

Federico Migliore, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Manuel De Lazzari, University Hospital of Padua, ItalyRaimondo Pittorru, University of Padua, Italy

Copyright: © 2025 Russo, Caturano, Bianchi, Rago, Ammendola, Papa, Della Cioppa, Guarino, Masi, D'Onofrio, Golino, Di Lorenzo and Nigro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vincenzo Russo, vincenzo.russo@unicampania.it

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Vincenzo Russo

Vincenzo Russo