Abstract

Objective:

Research on predictive models for hospital mortality in patients who have survived 24 h following cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is limited. We aim to explore the factors associated with hospital mortality in these patients and develop a predictive model to aid clinical decision-making and enhance the survival rates of patients post-resuscitation.

Methods:

We sourced the data from a retrospective study within the Dryad dataset, dividing patients who suffered cardiac arrest following CPR into a training set and a validation set at a 7:3 ratio. We identified variables linked to hospital mortality in the training set using Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression, as well as univariate and multivariate logistic analyses. Utilizing these variables, we developed a prognostic nomogram for predicting mortality post-CPR. Calibration curves, the area under receiver operating curves (ROC), decision curve analysis (DCA), and clinical impact curve were used to assess the discriminability, accuracy, and clinical utility of the nomogram.

Results:

The study population comprised 374 patients, with 262 allocated to the training group and 112 to the validation group. Of these, 213 patients were dead in the hospital. Multivariate logistic analysis revealed age (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08), witnessed arrest (OR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.11–0.73), time to return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.08), non-shockable rhythm (OR 3.41, 95% CI: 1.61–7.18), alkaline phosphatase (OR 1.01, 95% CI: 1–1.01), and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15–1.4) were independent risk factors for hospital mortality for patients who survived 24 h after CPR. ROC of the nomogram showed the AUC in the training and validation group was 0.827 and 0.817, respectively. Calibration curves, DCA, and clinical impact curve demonstrated the nomogram with good accuracy and clinical utility.

Conclusion:

Our prediction model had accurate predictive value for hospital mortality in patients who survived 24 h after CPR, which will be beneficial for assisting in identifying high-risk patients and intervention. Further confirmation of the model's accuracy required external validation data.

Introduction

In the United States, 420,000 people suffer from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest each year, and the survival rate is only about 6% (1, 2). Early assessment in patients with cardiac arrest can improve their prognosis and reduce the mortality rate (3). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the only effective treatment for cardiac arrest (4–6). In recent years, remarkable progress has been made in the field of CPR, such as the optimization of compression techniques, the popular application of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), and comprehensive treatment strategies after CPR. Every innovation and improvement may have a significant impact on the survival rate of patients. The widespread dissemination of education and training has enabled more members of the public to master this life-saving skill, thereby providing timely assistance in emergencies. Despite recent progress in resuscitation medicine and critical care medicine, the mortality rate after cardiac arrest remains high, especially in the case of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (7). Accurate prognosis assessment is an important method for improving treatment efficiency, enhancing outcomes, preserving patient dignity, and reducing the burden of cardiac arrest.

Several studies have developed predictive models for hospital mortality following CPR, yet these models possess certain limitations, including their application primarily to pediatric patients or those experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, suboptimal prediction accuracy, and the omission of clinical laboratory variables (8–11). Therefore, we aimed to investigate the variables associated with hospital mortality for patients who survived 24 h after CPR, and then construct a predictive model that can guide clinical treatment decisions and improve resuscitation survival.

Methods and materials

Data resource

The data resource in this study are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.qv6fp83), which is an open data publishing platform devoted to the open availability and reuse of all research data.

Study population

This retrospective study was conducted by Iesu et al. (12) in the Intensive Care Unit of Erasme Hospital in Brussels (Belgium). 435 patients with coma (Glasgow Coma Scale, GCS < 9) after cardiac arrest were recruited in the study from January 2007 to December 2015, 61 patients with missing clinical data or death less than 24 h after admission were excluded, and finally 374 patients were included in our analysis. Patients were treated with standard post-resuscitation management broadly described elsewhere (12, 13).

Data collection

We collected these data for analysis in our study: (1) demographics: age, sex and weight; (2) comorbidities: chronic heart failure, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/asthma, neurological disease, chronic renal failure, acute kidney injury (AKI), liver cirrhosis, HIV; (3) arrest characteristics: witnessed, time to return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), adrenaline, out of hospital, non-shockable rhythm, ICU mortality, hospital mortality, by stander CPR; (4) Severity of disease: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score; (5) laboratory test: lactate, central venous oxygen saturation or mixed venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2/SvO2), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamine transferase (GGT), total bilirubin, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), platelets, proteins, glucose, pH, PaCO2, PaO2, mean arterial pressure (MAP), creatine, C-reactive protein (CRP); (6) treatment during hospital: targeted temperature management (TTM), intra-aortic balloon counter pulsation (IABP), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 27 and R 4.1.3 software were used in our analysis. Continuous data was presented as X ± S and a comparison between two groups was used t-test. Nonparametric variables were supplied as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and comparison between groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test. When appropriate, categorical variables were assessed using Fisher's exact or the χ2 test and given as numbers (percentage). The dataset is partitioned into a training set and a validation set at a ratio of 7:3. Within the training set, variable selection is initially conducted using LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression, which is a regression analysis method that performs both variable selection and regularization to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the statistical model by shrinking the coefficients of less important predictors to exactly zero. Following this, univariate logistic regression is applied to further screen the variables. Variables with univariate P-values less than 0.05 are included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors associated with the prognosis. Finally, a nomogram prediction model is constructed based on the variables selected through this rigorous process. The prediction model was evaluated by ROC, calibration curve, DCA, and clinical impact curve. The difference with P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the training and test group

A total of 435 patients were enrolled in the study. However, 61 patients were excluded due to missing clinical data or death occurring within 24 h of admission. Finally 374 patients were included in our analysis, with 262 patients assigned to the training group and 112 patients to the validation group. Of these, 213 patients succumbed to their condition in the hospital. The baseline characteristics for the training and validation groups were presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | All N = 374 |

The training group N = 262 |

The validaiton group N = 112 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.00 [51.25; 74.00] | 62.00 [52.00; 74.75] | 62.50 [50.75; 72.25] | 0.425 |

| Weight, kg | 77.00 [67.25; 85.00] | 76.50 [67.25; 85.00] | 79.50 [67.75; 85.00] | 0.379 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.733 | |||

| Female | 104 (27.81%) | 71 (27.10%) | 33 (29.46%) | |

| Male | 270 (72.19%) | 191 (72.90%) | 79 (70.54%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.104 | |||

| No | 215 (57.49%) | 143 (54.58%) | 72 (64.29%) | |

| Yes | 159 (42.51%) | 119 (45.42%) | 40 (35.71%) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0.076 | |||

| No | 283 (75.67%) | 191 (72.90%) | 92 (82.14%) | |

| Yes | 91 (24.33%) | 71 (27.10%) | 20 (17.86%) | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 0.329 | |||

| No | 228 (60.96%) | 155 (59.16%) | 73 (65.18%) | |

| Yes | 146 (39.04%) | 107 (40.84%) | 39 (34.82%) | |

| COPD/Asthma, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No | 311 (83.16%) | 218 (83.21%) | 93 (83.04%) | |

| Yes | 63 (16.84%) | 44 (16.79%) | 19 (16.96%) | |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No | 296 (79.14%) | 207 (79.01%) | 89 (79.46%) | |

| Yes | 78 (20.86%) | 55 (20.99%) | 23 (20.54%) | |

| Previous neurologic disease, n (%) | 0.238 | |||

| No | 320 (85.56%) | 220 (83.97%) | 100 (89.29%) | |

| Yes | 54 (14.44%) | 42 (16.03%) | 12 (10.71%) | |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 0.273 | |||

| No | 311 (83.16%) | 222 (84.73%) | 89 (79.46%) | |

| Yes | 63 (16.84%) | 40 (15.27%) | 23 (20.54%) | |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 0.749 | |||

| No | 357 (95.45%) | 249 (95.04%) | 108 (96.43%) | |

| Yes | 17 (4.55%) | 13 (4.96%) | 4 (3.57%) | |

| Corticoids, n (%) | 0.797 | |||

| No | 289 (77.27%) | 201 (76.72%) | 88 (78.57%) | |

| Yes | 85 (22.73%) | 61 (23.28%) | 24 (21.43%) | |

| Chronic anticoagulation, n (%) | 0.544 | |||

| No | 309 (82.62%) | 219 (83.59%) | 90 (80.36%) | |

| Yes | 65 (17.38%) | 43 (16.41%) | 22 (19.64%) | |

| Witnessed arrest, n (%) | 0.829 | |||

| No | 54 (14.44%) | 39 (14.89%) | 15 (13.39%) | |

| Yes | 320 (85.56%) | 223 (85.11%) | 97 (86.61%) | |

| Bystander CPR, n (%) | 0.556 | |||

| No | 120 (32.09%) | 87 (33.21%) | 33 (29.46%) | |

| Yes | 254 (67.91%) | 175 (66.79%) | 79 (70.54%) | |

| Time to ROSC, min | 15.00 [7.00; 25.00] | 15.00 [7.00; 25.00] | 14.50 [7.00; 24.00] | 0.495 |

| Non cardiac etiology, n (%) | 0.762 | |||

| No | 221 (59.09%) | 153 (58.40%) | 68 (60.71%) | |

| Yes | 153 (40.91%) | 109 (41.60%) | 44 (39.29%) | |

| Non-shockable rhythm, n (%) | 0.125 | |||

| No | 153 (40.91%) | 100 (38.17%) | 53 (47.32%) | |

| Yes | 221 (59.09%) | 162 (61.83%) | 59 (52.68%) | |

| Epinephrine, mg | 3.00 [2.00; 5.00] | 3.00 [1.25; 5.00] | 3.00 [2.00; 5.00] | 0.724 |

| Out of hospital, n (%) | 0.046 | |||

| No | 166 (44.39%) | 107 (40.84%) | 59 (52.68%) | |

| Yes | 208 (55.61%) | 155 (59.16%) | 53 (47.32%) | |

| TTM, n (%) | 0.978 | |||

| No | 42 (11.23%) | 30 (11.45%) | 12 (10.71%) | |

| Yes | 332 (88.77%) | 232 (88.55%) | 100 (89.29%) | |

| Hospital death, n (%) | 0.328 | |||

| No | 161 (43.05%) | 108 (41.22%) | 53 (47.32%) | |

| Yes | 213 (56.95%) | 154 (58.78%) | 59 (52.68%) | |

| IABP, n (%) | 0.752 | |||

| No | 350 (93.58%) | 244 (93.13%) | 106 (94.64%) | |

| Yes | 24 (6.42%) | 18 (6.87%) | 6 (5.36%) | |

| ECMO, n (%) | 0.592 | |||

| No | 327 (87.43%) | 227 (86.64%) | 100 (89.29%) | |

| Yes | 47 (12.57%) | 35 (13.36%) | 12 (10.71%) | |

| Shock, n (%) | 0.753 | |||

| No | 174 (46.52%) | 120 (45.80%) | 54 (48.21%) | |

| Yes | 200 (53.48%) | 142 (54.20%) | 58 (51.79%) | |

| ICU Vasopressor therapy, n (%) | 0.645 | |||

| No | 91 (24.33%) | 66 (25.19%) | 25 (22.32%) | |

| Yes | 283 (75.67%) | 196 (74.81%) | 87 (77.68%) | |

| ICU dobutamine, n (%) | 0.702 | |||

| No | 173 (46.26%) | 119 (45.42%) | 54 (48.21%) | |

| Yes | 201 (53.74%) | 143 (54.58%) | 58 (51.79%) | |

| CRRT, n (%) | 0.815 | |||

| No | 313 (83.69%) | 218 (83.21%) | 95 (84.82%) | |

| Yes | 61 (16.31%) | 44 (16.79%) | 17 (15.18%) | |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 0.910 | |||

| No | 187 (50.00%) | 130 (49.62%) | 57 (50.89%) | |

| Yes | 187 (50.00%) | 132 (50.38%) | 55 (49.11%) | |

| Beta lactams, n (%) | 0.383 | |||

| No | 216 (57.75%) | 147 (56.11%) | 69 (61.61%) | |

| Yes | 158 (42.25%) | 115 (43.89%) | 43 (38.39%) | |

| AKI, n (%) | 0.876 | |||

| No | 153 (40.91%) | 106 (40.46%) | 47 (41.96%) | |

| Yes | 221 (59.09%) | 156 (59.54%) | 65 (58.04%) | |

| Lowest ScvO2, % | 62.00 [56.10; 66.10] | 62.00 [56.00; 66.47] | 62.00 [56.95; 66.00] | 0.953 |

| Minimum platelets, /mm3 | 132.50 [79.25; 187.00] | 132.50 [72.50; 183.25] | 132.50 [88.75; 193.50] | 0.356 |

| Lactate, mEq/L | 5.10 [4.10; 7.70] | 5.15 [4.20; 7.60] | 4.70 [3.88; 7.80] | 0.188 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 40.00 [14.25; 83.50] | 40.00 [16.50; 80.00] | 35.00 [9.00; 90.00] | 0.330 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.20 [0.90; 1.60] | 1.20 [0.90; 1.60] | 1.20 [0.90; 1.50] | 0.386 |

| ScvO2/SvO2 on admission, % | 68.85 [63.70; 74.40] | 68.75 [63.28; 74.30] | 69.00 [64.60; 74.75] | 0.299 |

| AST, IU/L | 95.00 [47.00; 192.50] | 100.50 [51.00; 208.25] | 85.50 [40.00; 151.25] | 0.063 |

| ALT, IU/L | 68.00 [32.00; 152.75] | 72.00 [33.00; 166.00] | 58.50 [30.00; 113.50] | 0.044 |

| LDH, IU/L | 335.50 [240.00; 488.00] | 343.50 [245.25; 486.75] | 329.50 [233.75; 489.50] | 0.435 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 77.00 [58.00; 106.00] | 74.50 [59.00; 101.75] | 81.50 [57.00; 116.50] | 0.519 |

| GGT, IU/L | 69.00 [43.00; 102.00] | 69.00 [43.00; 101.49] | 72.50 [42.00; 104.00] | 0.822 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.51 [0.33; 0.86] | 0.51 [0.33; 0.87] | 0.51 [0.35; 0.85] | 0.733 |

| APTT, sec | 32.30 [27.25; 44.10] | 33.25 [27.40; 44.72] | 31.50 [27.12; 42.25] | 0.284 |

| PT, % | 65.00 [47.00; 79.00] | 62.00 [46.00; 77.75] | 69.00 [53.00; 81.25] | 0.014 |

| INR | 1.26 [1.12; 1.54] | 1.30 [1.12; 1.61] | 1.21 [1.12; 1.42] | 0.027 |

| Platelets on admission, /mm3 | 201.00 [138.25; 266.25] | 201.00 [138.25; 250.75] | 199.00 [138.75; 282.00] | 0.506 |

| Protein, mg/dl | 5.70 [5.00; 6.40] | 5.70 [5.10; 6.50] | 5.70 [5.00; 6.23] | 0.444 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 199.50 [155.00; 289.25] | 206.50 [152.25; 293.75] | 190.50 [159.75; 278.25] | 0.273 |

| pH | 7.30 [7.21; 7.38] | 7.29 [7.20; 7.38] | 7.30 [7.22; 7.39] | 0.445 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 111.00 [85.00; 178.00] | 119.00 [87.00; 183.00] | 104.50 [84.75; 152.00] | 0.076 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 37.00 [33.00; 44.00] | 37.00 [32.00; 44.00] | 39.00 [34.00; 44.00] | 0.176 |

| MAP, mmHg | 86.00 [75.25; 103.00] | 86.00 [75.00; 103.00] | 89.00 [76.75; 105.25] | 0.475 |

| APACHE II | 25.00 [20.00; 29.00] | 25.00 [20.00; 29.00] | 24.00 [20.00; 30.00] | 0.855 |

| SOFA | 11.00 [9.00; 14.00] | 11.00 [9.00; 14.00] | 10.50 [8.00; 14.00] | 0.117 |

Baseline characteristics of the training and validation group.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; APACHE II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation score; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment score; ScvO2/SvO2, central venous oxygen saturation or mixed venous oxygen saturation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GGT, γ-glutamine transferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; TTM, targeted temperature management; IABP, intra-aortic balloon counter pulsation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy; AKI, acute kidney injury.

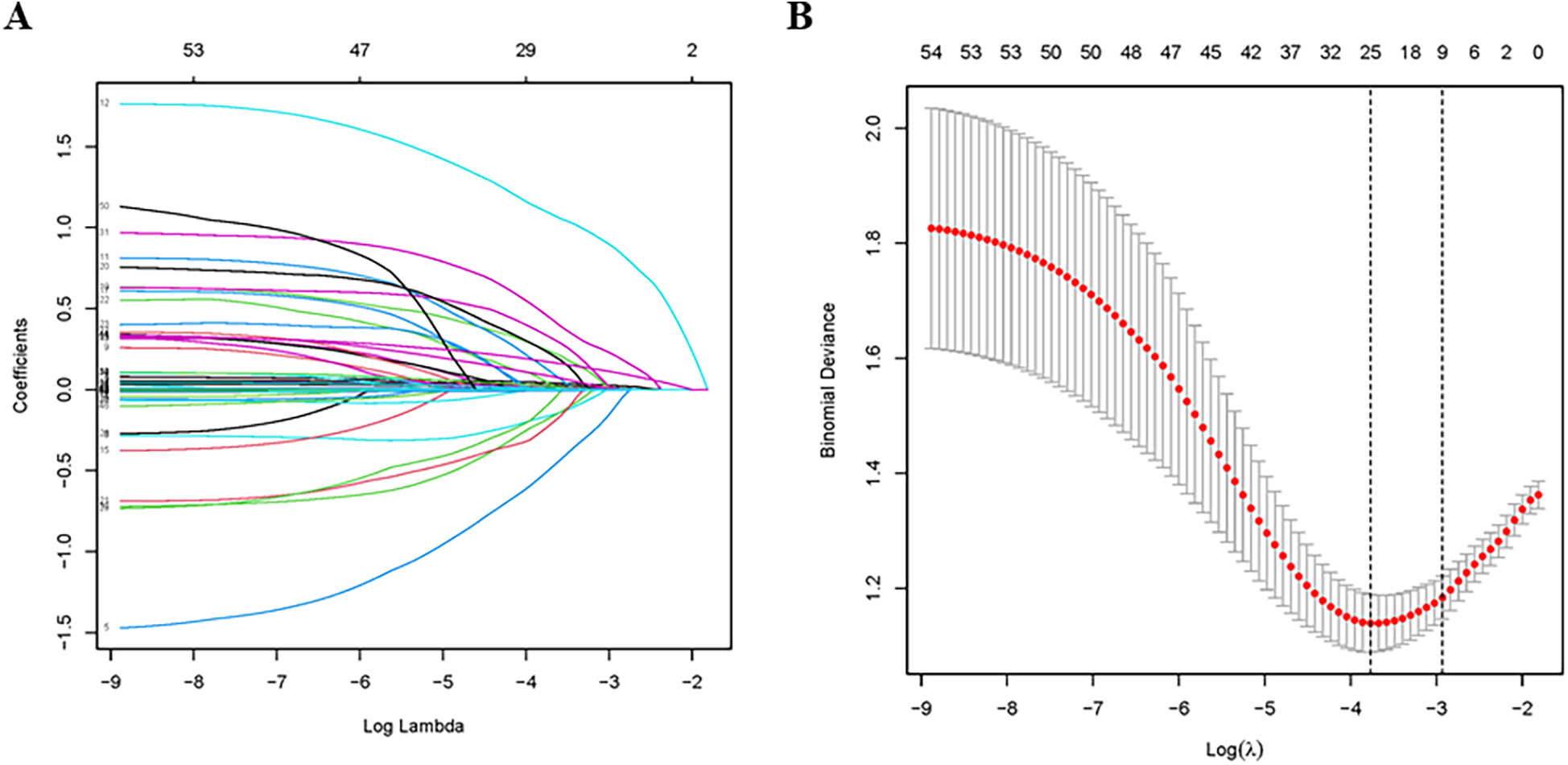

Variables associated with hospital mortality in the training group

The LASSO logistic regression was performed for variable selection and Lambda min was chosen as the best model. 25 variables were selected from 54 variables in the training group (Table 2), including age, witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, time to ROSC, epinephrine, TTM, non-cardiac etiology, non-shockable rhythm, hypertension, COPD/asthma, previous neurological disease, chronic renal failure, liver cirrhosis, CRRT, AKI, lowest ScvO2, lactate, ScvO2/SvO2, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, APTT, proteins, PaO2, MAP and SOFA (Figure 1). We initiated the analysis with a univariate logistic regression on 25 preselected variables. The results of this preliminary analysis retained 12 variables with a significance level of P < 0.05 for further examination through multivariate logistic regression, which was conducted following a stepwise regression approach. Ultimately, six independent variables were identified for the construction of the nomogram: age [odds ratio [OR] 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–1.08], witnessed arrest (OR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.11–0.73), time to return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.08), non-shockable rhythm (OR 3.41, 95% CI: 1.61–7.18), alkaline phosphatase levels (OR 1.01, 95% CI: 1–1.01), and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15–1.4). These findings are detailed in Table 3.

Table 2

| Variables | N = 262 | Survivor = 108 | Death = 154 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.00 [52.00; 74.75] | 59.00 [50.75; 71.00] | 65.00 [54.00; 76.00] | 0.012 |

| Weight, kg | 76.50 [67.25; 85.00] | 76.50 [70.00; 85.00] | 76.00 [65.00; 85.00] | 0.564 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.435 | |||

| Female | 71 (27.10%) | 26 (24.07%) | 45 (29.22%) | |

| Male | 191 (72.90%) | 82 (75.93%) | 109 (70.78%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.385 | |||

| No | 143 (54.58%) | 55 (50.93%) | 88 (57.14%) | |

| Yes | 119 (45.42%) | 53 (49.07%) | 66 (42.86%) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0.435 | |||

| No | 191 (72.90%) | 82 (75.93%) | 109 (70.78%) | |

| Yes | 71 (27.10%) | 26 (24.07%) | 45 (29.22%) | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 0.877 | |||

| No | 155 (59.16%) | 65 (60.19%) | 90 (58.44%) | |

| Yes | 107 (40.84%) | 43 (39.81%) | 64 (41.56%) | |

| COPD/Asthma, n (%) | 0.058 | |||

| No | 218 (83.21%) | 96 (88.89%) | 122 (79.22%) | |

| Yes | 44 (16.79%) | 12 (11.11%) | 32 (20.78%) | |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 0.958 | |||

| No | 207 (79.01%) | 86 (79.63%) | 121 (78.57%) | |

| Yes | 55 (20.99%) | 22 (20.37%) | 33 (21.43%) | |

| Previous neurological disease, n (%) | 0.100 | |||

| No | 220 (83.97%) | 96 (88.89%) | 124 (80.52%) | |

| Yes | 42 (16.03%) | 12 (11.11%) | 30 (19.48%) | |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No | 222 (84.73%) | 92 (85.19%) | 130 (84.42%) | |

| Yes | 40 (15.27%) | 16 (14.81%) | 24 (15.58%) | |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 0.098 | |||

| No | 249 (95.04%) | 106 (98.15%) | 143 (92.86%) | |

| Yes | 13 (4.96%) | 2 (1.85%) | 11 (7.14%) | |

| Corticoids, n (%) | 0.168 | |||

| No | 201 (76.72%) | 88 (81.48%) | 113 (73.38%) | |

| Yes | 61 (23.28%) | 20 (18.52%) | 41 (26.62%) | |

| Chronic anticoagulation, n (%) | 0.451 | |||

| No | 219 (83.59%) | 93 (86.11%) | 126 (81.82%) | |

| Yes | 43 (16.41%) | 15 (13.89%) | 28 (18.18%) | |

| Witnessed arrest, n (%) | 0.049 | |||

| No | 39 (14.89%) | 10 (9.26%) | 29 (18.83%) | |

| Yes | 223 (85.11%) | 98 (90.74%) | 125 (81.17%) | |

| Bystander CPR, n (%) | 0.153 | |||

| No | 87 (33.21%) | 30 (27.78%) | 57 (37.01%) | |

| Yes | 175 (66.79%) | 78 (72.22%) | 97 (62.99%) | |

| Time to ROSC, min | 15.00 [7.00; 25.00] | 12.50 [5.75; 20.00] | 18.00 [10.00; 26.75] | 0.005 |

| Non-cardiac etiology, n (%) | 0.008 | |||

| No | 153 (58.40%) | 74 (68.52%) | 79 (51.30%) | |

| Yes | 109 (41.60%) | 34 (31.48%) | 75 (48.70%) | |

| Non-shockable rhythm, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 100 (38.17%) | 62 (57.41%) | 38 (24.68%) | |

| Yes | 162 (61.83%) | 46 (42.59%) | 116 (75.32%) | |

| Epinephrine, mg | 3.00 [1.25; 5.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 4.00] | 4.00 [2.00; 7.00] | 0.001 |

| Out of Hospital, n (%) | 0.682 | |||

| No | 107 (40.84%) | 42 (38.89%) | 65 (42.21%) | |

| Yes | 155 (59.16%) | 66 (61.11%) | 89 (57.79%) | |

| TTM, n (%) | 0.217 | |||

| no | 30 (11.45%) | 16 (14.81%) | 14 (9.09%) | |

| yes | 232 (88.55%) | 92 (85.19%) | 140 (90.91%) | |

| IABP, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No | 244 (93.13%) | 101 (93.52%) | 143 (92.86%) | |

| Yes | 18 (6.87%) | 7 (6.48%) | 11 (7.14%) | |

| ECMO, n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| No | 227 (86.64%) | 94 (87.04%) | 133 (86.36%) | |

| Yes | 35 (13.36%) | 14 (12.96%) | 21 (13.64%) | |

| Shock, n (%) | 0.043 | |||

| No | 120 (45.80%) | 58 (53.70%) | 62 (40.26%) | |

| Yes | 142 (54.20%) | 50 (46.30%) | 92 (59.74%) | |

| ICU vasopressor therapy, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| No | 66 (25.19%) | 38 (35.19%) | 28 (18.18%) | |

| Yes | 196 (74.81%) | 70 (64.81%) | 126 (81.82%) | |

| ICU Dobutamine, n (%) | 0.385 | |||

| No | 119 (45.42%) | 53 (49.07%) | 66 (42.86%) | |

| Yes | 143 (54.58%) | 55 (50.93%) | 88 (57.14%) | |

| CRRT, n (%) | 0.831 | |||

| No | 218 (83.21%) | 91 (84.26%) | 127 (82.47%) | |

| Yes | 44 (16.79%) | 17 (15.74%) | 27 (17.53%) | |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 0.465 | |||

| No | 130 (49.62%) | 57 (52.78%) | 73 (47.40%) | |

| Yes | 132 (50.38%) | 51 (47.22%) | 81 (52.60%) | |

| Beta lactams, n (%) | 0.630 | |||

| No | 147 (56.11%) | 63 (58.33%) | 84 (54.55%) | |

| Yes | 115 (43.89%) | 45 (41.67%) | 70 (45.45%) | |

| AKI, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| No | 106 (40.46%) | 57 (52.78%) | 49 (31.82%) | |

| Yes | 156 (59.54%) | 51 (47.22%) | 105 (68.18%) | |

| Lowest ScvO2, % | 62.00 [56.00; 66.47] | 60.85 [55.35; 65.85] | 63.00 [57.00; 67.00] | 0.114 |

| Minimum platelets, /mm3 | 132.50 [72.50; 183.25] | 133.00 [92.50; 177.75] | 132.00 [66.00; 187.00] | 0.605 |

| Lactate, mEq/L | 5.15 [4.20; 7.60] | 4.60 [3.88; 6.12] | 5.60 [4.40; 8.67] | 0.001 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 40.00 [16.50; 80.00] | 32.50 [12.00; 73.25] | 43.50 [20.00; 86.25] | 0.149 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.20 [0.90; 1.60] | 1.10 [0.90; 1.50] | 1.20 [0.90; 1.80] | 0.215 |

| ScvO2/SvO2, % | 68.75 [63.28; 74.30] | 67.15 [62.45; 72.65] | 69.40 [63.70; 75.40] | 0.039 |

| AST, IU/L | 100.50 [51.00; 208.25] | 85.00 [46.75; 209.25] | 108.00 [53.00; 205.50] | 0.218 |

| ALT, IU/L | 72.00 [33.00; 166.00] | 74.00 [33.00; 172.75] | 72.00 [33.00; 150.50] | 0.935 |

| LDH, IU/L | 343.50 [245.25; 486.75] | 310.00 [235.50; 459.50] | 352.00 [251.00; 507.25] | 0.079 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 74.50 [59.00; 101.75] | 69.00 [58.00; 86.00] | 82.50 [59.25; 109.00] | 0.005 |

| GGT, IU/L | 69.00 [43.00; 101.49] | 62.50 [40.75; 101.49] | 76.50 [45.25; 101.12] | 0.169 |

| Total bilirubin, IU/L | 0.51 [0.33; 0.87] | 0.48 [0.32; 0.78] | 0.54 [0.36; 1.10] | 0.042 |

| APTT, sec | 33.25 [27.40; 44.72] | 31.50 [26.17; 44.28] | 34.25 [28.60; 45.65] | 0.105 |

| PT, sec | 61.28 (23.33) | 64.92 (23.74) | 58.73 (22.78) | 0.036 |

| INR | 1.30 [1.12; 1.61] | 1.24 [1.08; 1.49] | 1.34 [1.20; 1.66] | 0.012 |

| Platelets, /mm3 | 201.00 [138.25; 250.75] | 204.00 [150.75; 249.25] | 191.00 [126.25; 258.25] | 0.337 |

| Proteins, mg/dl | 5.70 [5.10; 6.50] | 5.80 [5.30; 6.53] | 5.60 [5.00; 6.50] | 0.404 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 206.50 [152.25; 293.75] | 195.00 [135.75; 275.50] | 210.00 [161.25; 303.75] | 0.184 |

| PH | 7.29 [7.20; 7.38] | 7.30 [7.22; 7.38] | 7.29 [7.19; 7.38] | 0.452 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 119.00 [87.00; 183.00] | 132.50 [87.00; 178.50] | 112.00 [84.00; 185.50] | 0.480 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 37.00 [32.00; 44.00] | 39.00 [32.00; 45.00] | 36.00 [32.00; 43.00] | 0.134 |

| MAP, mmHg | 86.00 [75.00; 103.00] | 93.00 [81.50; 108.00] | 83.00 [72.00; 96.75] | <0.001 |

| APACHE II | 24.26 (6.93) | 23.18 (6.29) | 25.02 (7.27) | 0.030 |

| SOFA | 11.00 [9.00; 14.00] | 10.00 [8.75; 12.00] | 13.00 [10.00; 15.00] | <0.001 |

Variables associated with hospital mortality in the training group.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; APACHE II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation score; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment score; ScvO2/SvO2, central venous oxygen saturation or mixed venous oxygen saturation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GGT, γ-glutamine transferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; TTM, targeted temperature management; IABP, intra-aortic balloon counter pulsation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy; AKI, acute kidney injury.

Figure 1

Variable selection using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression model. (A) LASSO coefficient profiles of the 54 candidate predictors; (B) tuning parameter (λ) selection used 10-fold cross-validation in the LASSO model.

Table 3

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age, years | 1.02 | 1–1.04 | 0.019 | 1.05 | 1.03–1.08 | <0.001 |

| Witnessed Arrest | 0.44 | 0.2–0.95 | 0.036 | 0.28 | 0.11–0.73 | 0.01 |

| Bystander CPR | 0.65 | 0.38–1.12 | 0.119 | |||

| Time to ROSC, min | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.008 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | <0.001 |

| Epinephrine, mg | 1.13 | 1.04–1.21 | 0.002 | |||

| TTM | 1.74 | 0.81–3.73 | 0.156 | |||

| Non-cardiac etiology | 2.07 | 1.24–3.46 | 0.006 | 1.76 | 0.81–3.79 | 0.151 |

| Non-shockable rhythm | 4.11 | 2.42–6.98 | <0.001 | 3.41 | 1.61–7.18 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.78 | 0.47–1.28 | 0.32 | |||

| COPD/Asthma | 2.1 | 1.03–4.29 | 0.042 | 2.44 | 1–5.96 | 0.05 |

| Previous neurological disease | 1.94 | 0.94–3.98 | 0.072 | |||

| Chronic renal failure | 1.06 | 0.53–2.11 | 0.865 | |||

| Liver cirrhosis | 4.08 | 0.89–18.78 | 0.071 | |||

| CRRT | 1.14 | 0.59–2.21 | 0.703 | |||

| AKI | 2.39 | 1.44–3.98 | 0.001 | 1.82 | 0.95–3.51 | 0.073 |

| Lowest ScvO2 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.169 | |||

| Lactate, mEq/L | 1.11 | 1.02–1.21 | 0.012 | |||

| ScvO2/SvO2 | 1.03 | 1–1.06 | 0.037 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.096 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 1.01 | 1–1.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1–1.01 | 0.021 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 1.34 | 1–1.78 | 0.048 | 1.26 | 0.95–1.68 | 0.112 |

| APTT, sec | 1 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.813 | |||

| Proteins, mg/dl | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.394 | |||

| PaO2, mmHg | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.468 | |||

| MAP, mmHg | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.97–1 | 0.142 |

| SOFA | 1.18 | 1.1–1.28 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 1.15–1.4 | <0.001 |

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for variables selection associated with hospital mortality.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment score; ScvO2/SvO2, central venous oxygen saturation or mixed venous oxygen saturation; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; MAP, mean arterial pressure; TTM, targeted temperature management.

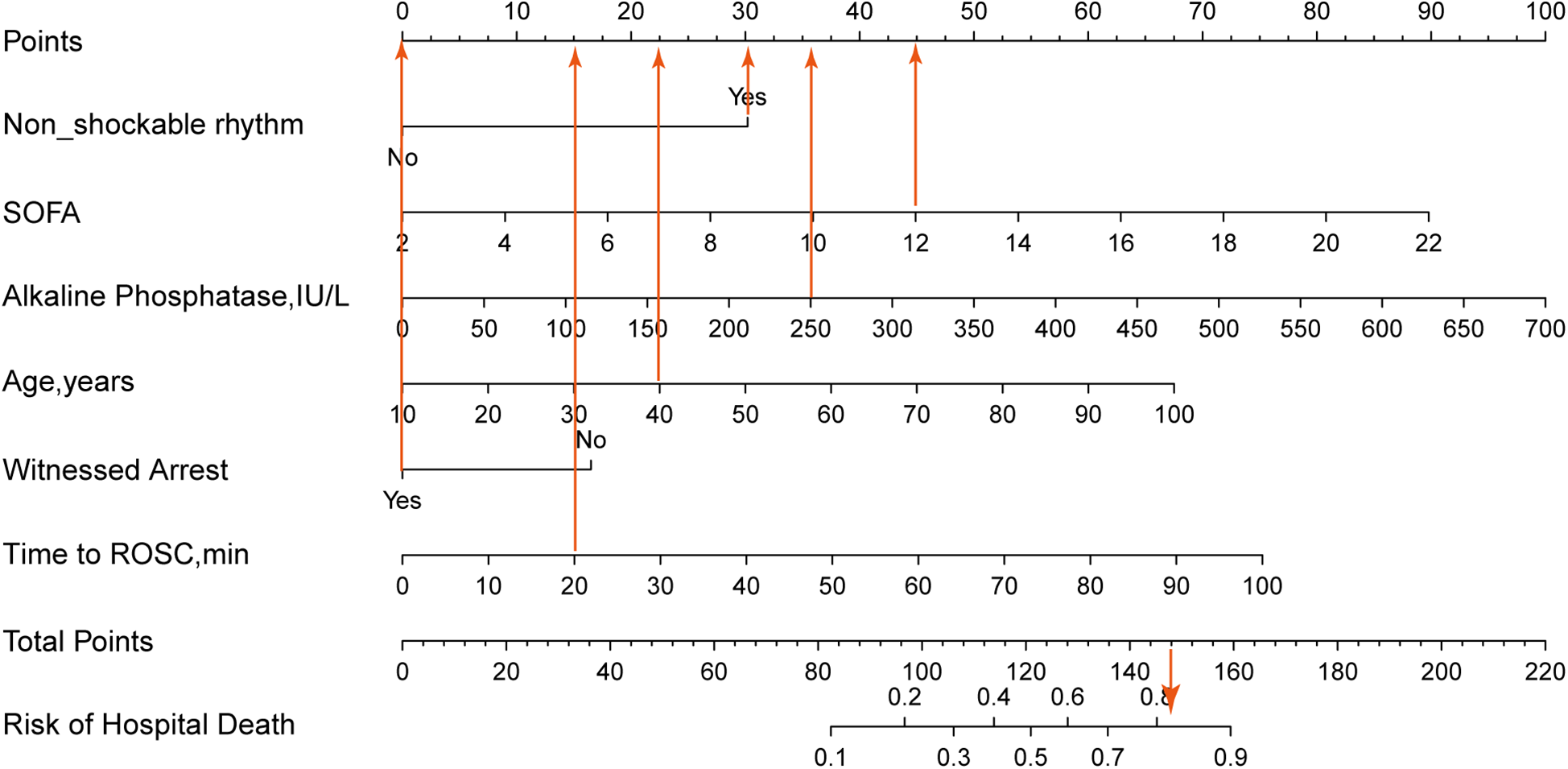

Construction of a prediction nomogram

Based on the 6 independent variables (age, witnessed arrest, time to ROSC, non-shockable rhythm, alkaline phosphatase and SOFA), a prediction nomogram was constructed and we could accurately predict the probability of hospital mortality for individuals with cardiac arrest who survived 24 h after CPR (Figure 2). Each variable was assigned a different score within the range of 0–100 based on its level of importance. We summed the individual scores to calculate a total point. This total point was then converted into a unique risk percentage for hospital mortality, ranging from 0% to 100%. It was proposed that a higher total point from the predictive nomogram signified a greater risk of hospital mortality, whereas a lower total point implied a lesser likelihood of developing hospital mortality. In terms of the clinical application of the nomogram, if a 40-year-old patient had non-shockable rhythm, a SOFA score of 12, alkaline phosphatase of 250 IU/L, with a by-stander witnessed arrest, and with a time of ROSC of 20 min and the corresponding scores for the various factors would be 22.5, 30, 45, 35.5, 0, and 15, summing up to a total of 148 points. Consequently, this person's risk of hospital mortality was approximately 82%, indicating a relatively high risk of developing hospital mortality.

Figure 2

The nomogram was constructed based on the 6 variables from multivariate logistic regression. The nomogram adds up the points for each variable to get a total points and then reflects the probability of death based on the probability of the total points. If a 40-year-old patient had non-shockable rhythm, a SOFA score of 12, alkaline phosphatase of 250 IU/L, with a by-stander witnessed arrest, and with a time of ROSC of 20 min, and the corresponding scores for the various factors would be 22.5, 30, 45, 35.5, 0, and 15, summing up to a total of 148 points. Consequently, this person's risk of hospital mortality is approximately 82%, indicating a relatively high risk of developing hospital mortality.

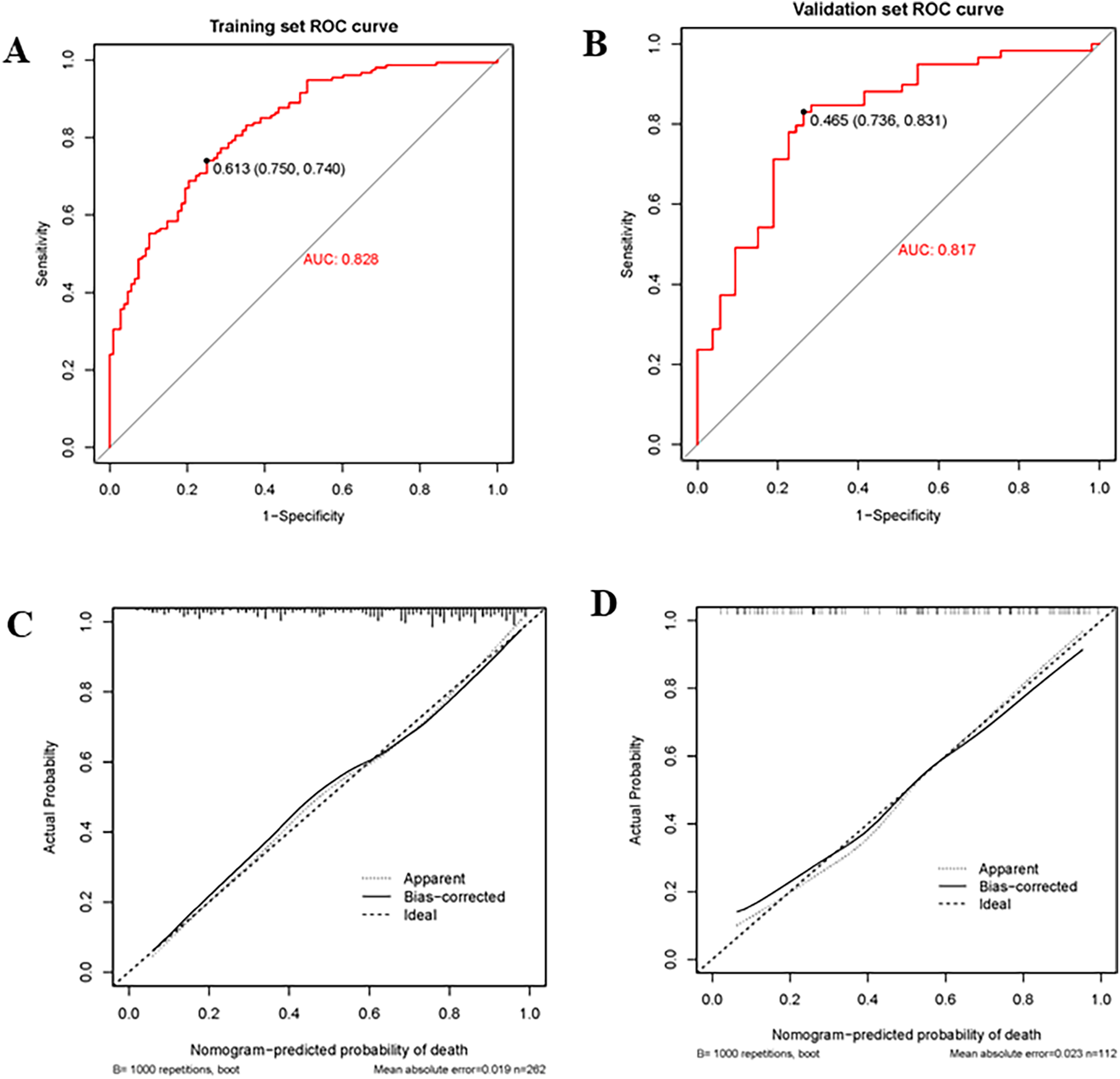

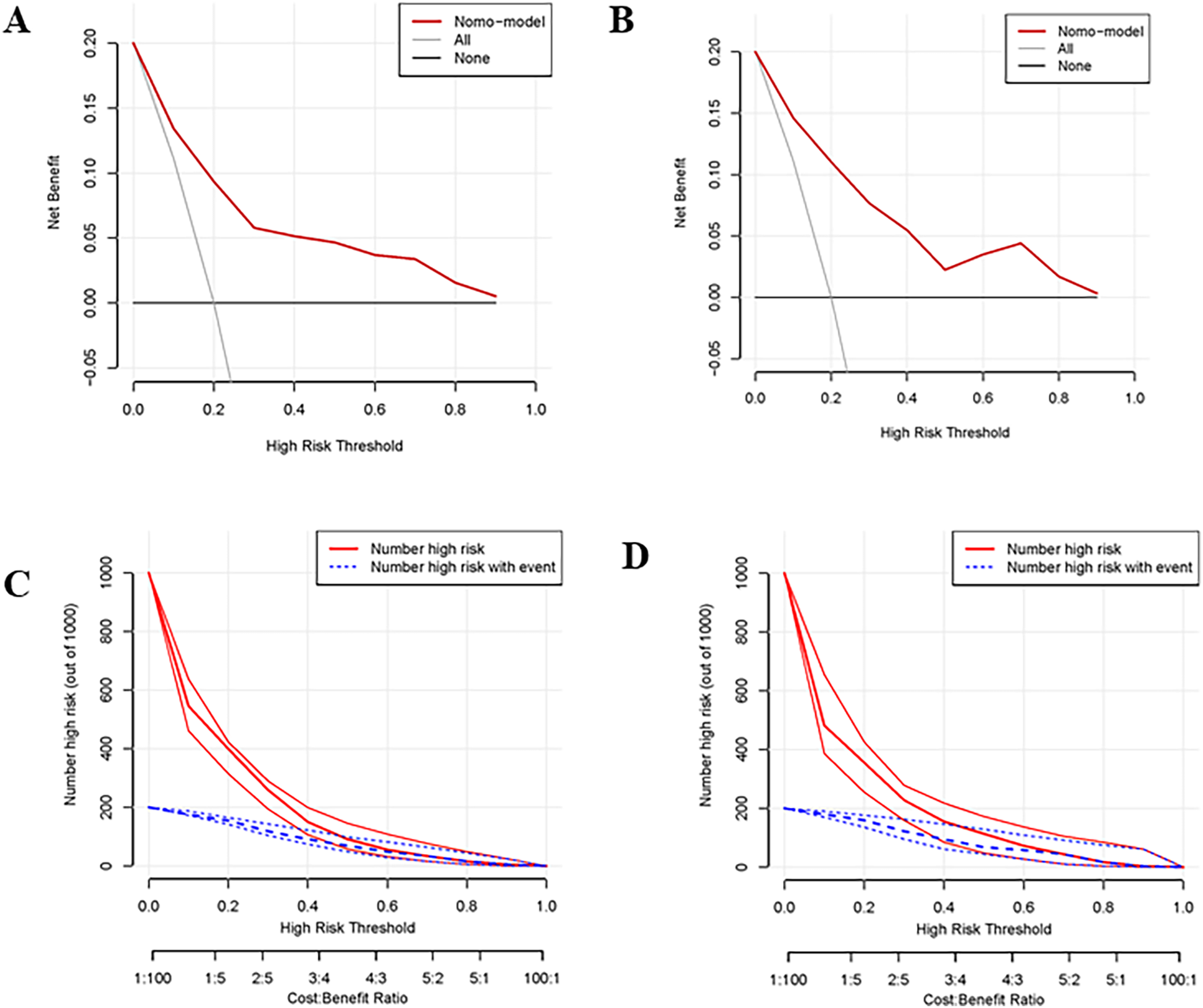

Evaluation and calibration of the nomogram

The nomogram had a good discriminating ability in the training group (AUC = 0.827; 95% CI: 0.778–0.876) and validation group (AUC = 0.817; 95% CI: 0.738–0.896) according to the area under receiver operating curves (Figures 3A,B). On the calibration curve, the death probability predicted by the model was close to the observed death probability (Figures 3C,D). The decision curve (Figures 4A,B) and clinical impact curve (Figures 4C,D) in the training and validation group demonstrated that this nomogram had good clinical utility.

Figure 3

Receiver operating curve (ROC), area under the curve (AUC), and calibration curve in the training group and validation group. (A,B) Showed the receiver operating curve (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) in the training group and validation group; (C,D) Showed calibration curves in the training group and validation group. The dashed line was the reference line of the ideal nomogram, the dotted line reflected the performance of the nomogram, while the solid line corrected for any bias in the nomogram.

Figure 4

Decision curve and clinical impact curve of the training group and validation group. (A,B) Showed the decision curve of the training group and validation group. The black horizontal line indicated that all patients are not treated, so there is no net benefit. The gray sloping line indicated that all patients received treatment, corresponding to the net benefit at different thresholds. The red curve was the net benefit at different risk thresholds based on the risk probability estimated by the constructed model. It can be seen that the net benefit of the model was higher than the net benefit of the horizontal and sloping line within a large threshold range indicating that the prediction value of the model was good. (C,D) Showed the clinical impact curve of the training group and validation group. The red curve indicated the number of patients classified as positive (high risk) by the model at each threshold probability, and the blue curve was the number of high risks with an event.

Discussion

We included 374 patients who underwent CPR after cardiac arrest from the database, with 262 patients in the training group and 112 patients in the validation group. Our study indicated that age (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08), witnessed arrest (OR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.11–0.73), time to ROSC (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.08), non-shockable rhythm (OR 3.41, 95% CI: 1.61–7.18), alkaline phosphatase (OR 1.01, 95% CI: 1–1.01) and SOFA (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15–1.4) were independent critical factors for predicting the risk of death 24 h after CPR. Furthermore, we constructed a nomogram based on these selected factors, which demonstrated good discrimination, accuracy, and clinical utility.

In the early stages of cardiac arrest, multiple organs in the body were still in a better state of oxygenation, and shockable rhythms were more likely to be successfully resuscitated at this stage, thereby increasing the proportion of good prognosis. In contrast, non-shockable rhythms often indicated cardiac energy depletion, failure of function, and a low percentage of successful resuscitation (14, 15). Shockable rhythms, including ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (PVT), were traditionally regarded as arrhythmias that could be reversed. By administering defibrillation, these rhythms can be corrected to restore the heart's normal rhythm and ensure proper blood flow to organs, thus enhancing the likelihood of survival (14, 16). One study showed that despite the presence of refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, patients with shockable rhythms were more likely to have a lower risk of poor prognosis (180-day mortality), with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.27 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.18–0.41 (17). Another study showed that patients with shockable rhythms after sudden cardiac arrest had a higher rate of survival discharged from the hospital (OR 5.21, 95% CI: 2.99–9.07) than those with non-shockable rhythms, after adjusting for sex, age, comorbidities, and ethnicity (18). Non-shockable rhythm typically referred to asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA), leading to prolonged ischemia of the brain and other organs, resulting in poor neurological outcomes (19–22).

SOFA score was a simple method for assessing and monitoring organ dysfunction in critically ill patients and had been widely used to assess the severity of critically ill patients and predict their prognosis. The SOFA score comprised six criteria to reflect organ system function (respiratory system, blood system, liver system, cardiovascular system, nervous system, and kidney system) (23). Matsuda et al. (24) conducted a study in 231 cardiovascular arrest patients and found that the SOFA score was lower in those people who survived and SOFA score on admission was a strong predictor of survival at 30 days (OR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.59–0.78). Choi et al. (25) studied the prognosis of 173 patients without-hospital cardiac arrest and found the area under the curve of SOFA score for prediction of 30-day mortality of post-cardiac arrest patients was 0.641 (95% CI: 0.564–0.712). These studies indicated that a decrease in the SOFA score was associated with an increased rate of patient survival, and the SOFA score on admission was significant for predicting the survival rate within 30 days. These findings and our results emphasize the importance of considering the SOFA score in the initial assessment and treatment of patients with cardiac arrest.

When cardiac arrest strikes, time is crucial, with every passing second holding immense significance. Within a span of 4 to 6 min, most patients will start experiencing irreversible brain damage, leading to biological death within a few minutes thereafter. A prompt recognition of cardiac arrest by a bystander, followed by the immediate administration of high-quality CPR, is pivotal in achieving a successful resuscitation outcome. For every 1-minute delay in CPR in cardiac arrest patients, their survival rate decreased by about 10% (26–28). Although numerous studies had demonstrated the importance of bystander CPR when someone witnesses an arrest, the rate of bystander CPR remained relatively low in many countries (29). Nevertheless, we know little about bystanders' perceptions that influenced the decision to start CPR. Our study found that witnessed arrest was independently associated with hospital mortality rate 24 h after CPR, which further reinforced the importance of teaching the early recognition of cardiac arrest.

ROSC was not only a sign of successful CPR but also was the starting point for further treatment and prognosis assessment. In the clinical practice, physicians closely monitored the status of ROSC and adjusted treatment plans accordingly, to improve patient survival rate and quality of life. However, the time to ROSC after CPR varied in different situations, and the ultimate outcomes were also different. In a Swedish cohort study, the median duration of CPR with ROSC was 5 (IQR 2–12) minutes (30). Data from the GWTG-R (Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation) registry have shown that the median time to achieve ROSC was 11 (IQR 6–21) minutes (31). Although longer duration of resuscitation was associated with worse outcomes, individuals could still benefit from prolonged CPR. Data from the American Heart Association GWTG-R registry showed that 88% of patients achieved sustained ROSC within 30 min (32). These studies indicated that the duration of CPR was closely associated with the success rate of ROSC, but the specific median time to ROSC varied. Therefore, understanding the median time to ROSC can help assess the effectiveness of CPR and may guide clinical decision-making. Our results showed a similar conclusion. The duration from cardiac arrest to the ROSC significantly impacted the survival probability and the shorter duration correlated with improved survival prospects.

Elderly patients were prone to many comorbidities and were therefore more likely to have a poor prognosis after cardiac arrest (33, 34). and some studies had revealed that advanced age was a strong predictor of mortality (31, 35). Sender et al. (36) conducted a study on patients with cardiac arrest in 6 interventional cardiology centers and found that elderly patients over 75 years old were more likely to have adverse neurological function prognosis at 6 months follow-up. Ester et al. (37) retrospectively analyzed 1,285 adult patients with cardiac arrest and found that older patients had worse neurological outcomes and a higher proportion of death after cardiac arrest compared with younger patients. Li et al. (38) retrospectively analyzed the risk factors, and in-hospital outcomes of 320 patients with acute coronary syndrome suffering cardiac arrest and they revealed that age less than 70 was demonstrated to be a strong predictor of survival. However, some studies have found that age was not a risk factor for survival after cardiac arrest, suggesting that when assessing the prognosis of patients who had experienced cardiac arrest, other clinical factors should also be considered in addition to age (39–43).

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a metalloenzyme in membrane-bound glycoprotein, and also an enzyme that catalyzes calcification inhibitor pyrophosphate hydrolysis. ALP is widely distributed in various organs and tissues of the human body, with the highest activity in the liver. The abnormalities can be seen in liver cancer, obstructive jaundice, and other diseases of the liver and bile system, as well as intestinal diseases, metabolic abnormalities, chronic renal insufficiency, and bone metabolism abnormalities (44, 45). Studies have shown that ALP was a new inflammatory mediator of cardiovascular diseases, and the increase of serum ALP level was associated with a variety of atherosclerotic diseases, indicating that ALP was closely related to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and its specific mechanism might be leading to increased vascular calcification and vascular dysfunction and thus to promote the release of inflammatory mediators (46–48). Zhong et al. (49) showed that the risk of the early death of stroke patients with high ALP levels was 2.19 times higher than that of stroke patients with low ALP level. Moreover, there was a significant linear relationship between serum ALP level and hospital mortality of cerebral infarction, which further revealed that serum ALP level was associated with poor recovery of neurological function, increased mortality, and overall poor prognosis of cerebral infarction patients. Another study showed that in patients with coronary heart disease, elevated ALP was an independent risk factor for increased 3-year all-cause mortality (50). Therefore, it was speculated that ALP, as an inflammatory indicator, reflected the occurrence and development of cardiac arrest patients to a certain extent, and could be used to predict the prognosis of cardiac arrest patients.

Our nomogram prediction model, based on these selected predictors, had accurate predictive value for hospital mortality in patients who survived 24 h after CPR, which will be beneficial for assisting in identifying high-risk patients and intervention. Compared with the predictive model from Chen et al. (51), we include more variables, up to 54 variables, and thus the predictive model may be more comprehensive and representative.

Limitations

Our research had some limitations. Firstly, it's an observational study with a relatively small sample size, and selection bias was inevitable, making it difficult to ensure an even distribution of all variables. Secondly, all participants were from Belgium. Further researches were needed to verify whether these findings were also applicable to different ethnicities and external validation data was required to further clarify the accuracy of this model. Thirdly, we analyzed a mixed population of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and in-hospital cardiac arrest, but there was a significant difference between the two groups, such as cause, prevention, and treatment, and these conditions should be taken into account.

Conclusion

Our research showed that non-shockable rhythm, SOFA score, witnessed arrest, time-to-ROSC, age, and alkaline phosphatase were significantly associated with hospital mortality for these patients who survived 24 h after CPR. Our nomogram prediction model had accurate predictive value for hospital mortality in patients who survived 24 h after CPR, which will be beneficial for assisting in identifying high-risk patients and intervention. Further confirmation of the model's accuracy required external validation data.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Dryad Digital Repository (https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.qv6fp83).

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Comite' d'Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire Erasme-ULB (P2017/264). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because The informed consent of patients was waived by the Ethics Committee due to the study's retrospective nature.

Author contributions

RZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LP: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported and funded by Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (No. 2023AFC016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Iesu et al. (12) for providing the data to be analyzed in our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Grasner JT Bossaert L . Epidemiology and management of cardiac arrest: what registries are revealing. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. (2013) 27(3):293–306. 10.1016/j.bpa.2013.07.008

2.

Go AS Mozaffarian D Roger VL Benjamin EJ Berry JD Blaha MJ et al Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2014) 129(3):e28–e292. 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80

3.

Girotra S Chan PS Bradley SM . Post-resuscitation care following out-of-hospital and in-hospital cardiac arrest. Heart. (2015) 101(24):1943–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307450

4.

D'Arrigo S Cacciola S Dennis M Jung C Kagawa E Antonelli M et al Predictors of favourable outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest treated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. (2017) 121:62–70. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.10.005

5.

Andersen LW Holmberg MJ Berg KM Donnino MW Granfeldt A . In-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. JAMA. (2019) 321(12):1200–10. 10.1001/jama.2019.1696

6.

Wang C Zheng W Zheng J Shao F Zhu Y Li C et al A national effort to improve outcomes for in-hospital cardiac arrest in China: the BASeline investigation of cardiac arrest (BASIC-IHCA). Resusc Plus. (2022) 11:100259. 10.1016/j.resplu.2022.100259

7.

Kitamura T Iwami T Kawamura T Nitta M Nagao K Nonogi H et al Nationwide improvements in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. Circulation. (2012) 126(24):2834–43. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109496

8.

Potpara TS Mihajlovic M Stankovic S Jozic T Jozic I Asanin MR et al External validation of the simple NULL-PLEASE clinical score in predicting outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Med. (2017) 130(12):1464.e13–e21. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.035

9.

Holmberg MJ Moskowitz A Raymond TT Berg RA Nadkarni VM Topjian AA et al Derivation and internal validation of a mortality prediction tool for initial survivors of pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2018) 19(3):186–95. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001416

10.

Baldi E Caputo ML Savastano S Burkart R Klersy C Benvenuti C et al An Utstein-based model score to predict survival to hospital admission: the UB-ROSC score. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 308:84–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.01.032

11.

Tonna JE Selzman CH Girotra S Presson AP Thiagarajan RR Becker LB et al Resuscitation using ECPR during in-hospital cardiac arrest (RESCUE-IHCA) mortality prediction score and external validation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15(3):237–47. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.09.032

12.

Iesu E Franchi F Zama Cavicchi F Pozzebon S Fontana V Mendoza M et al Acute liver dysfunction after cardiac arrest. PLoS One. (2018) 13(11):e0206655. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206655

13.

Tujjar O Mineo G Dell'Anna A Poyatos-Robles B Donadello K Scolletta S et al Acute kidney injury after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. (2015) 19(1):169. 10.1186/s13054-015-0900-2

14.

Perkins GD Handley AJ Koster RW Castrén M Smyth MA Olasveengen T et al European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation. Resuscitation. (2015) 95:81–99. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.015

15.

Han Y Hu H Shao Y Deng Z Liu D . The link between initial cardiac rhythm and survival outcomes in in-hospital cardiac arrest using propensity score matching, adjustment, and weighting. Sci Rep. (2024) 14(1):7621. 10.1038/s41598-024-58468-y

16.

Berdowski J Berg RA Tijssen JG Koster RW . Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation. (2010) 81(11):1479–87. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.006

17.

Havranek S Fingrova Z Rob D Smalcova J Kavalkova P Franek O et al Initial rhythm and survival in refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Post-hoc analysis of the Prague OHCA randomized trial. Resuscitation. (2022) 181:289–96. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.10.006

18.

Woolcott OO Reinier K Uy-Evanado A Nichols GA Stecker EC Jui J et al Sudden cardiac arrest with shockable rhythm in patients with heart failure. Heart Rhythm. (2020) 17(10):1672–8. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.038

19.

Fugate JE Rabinstein AA Claassen DO White RD Wijdicks EF . The FOUR score predicts outcome in patients after cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. (2010) 13(2):205–10. 10.1007/s12028-010-9407-5

20.

Aschauer S Dorffner G Sterz F Erdogmus A Laggner A . A prediction tool for initial out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation. (2014) 85(9):1225–31. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.007

21.

Kudenchuk PJ Brown SP Daya M Rea T Nichol G Morrison LJ et al Amiodarone, lidocaine, or placebo in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374(18):1711–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514204

22.

Rossetti AO Rabinstein AA Oddo M . Neurological prognostication of outcome in patients in coma after cardiac arrest. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15(6):597–609. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00015-6

23.

Meyer MAS Bjerre M Wiberg S Grand J Obling LER Meyer ASP et al Modulation of inflammation by treatment with tocilizumab after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and associations with clinical status, myocardial- and brain injury. Resuscitation. (2023) 184:109676. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.109676

24.

Matsuda J Kato S Yano H Nitta G Kono T Ikenouchi T et al The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score predicts mortality and neurological outcome in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. J Cardiol. (2020) 76(3):295–302. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.03.007

25.

Choi JY Jang JH Lim YS Jang JY Lee G Yang HJ et al Performance on the APACHE II, SAPS II, SOFA and the OHCA score of post-cardiac arrest patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia. PLoS One. (2018) 13(5):e0196197. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196197

26.

group S-Ks. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders with chest compression only (SOS-KANTO): an observational study. Lancet. (2007) 369(9565):920–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60451-6

27.

Ishikawa S Niwano S Imaki R Takeuchi I Irie W Toyooka T et al Usefulness of a simple prognostication score in prediction of the prognoses of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Int Heart J. (2013) 54(6):362–70. 10.1536/ihj.54.362

28.

Zhang X Zheng X Dai Z Zheng H . The development and validation of a nomogram to determine neurological outcomes in cardiac arrest patients. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23(1):289. 10.1186/s12871-023-02251-5

29.

Brinkrolf P Metelmann B Scharte C Zarbock A Hahnenkamp K Bohn A . Bystander-witnessed cardiac arrest is associated with reported agonal breathing and leads to less frequent bystander CPR. Resuscitation. (2018) 127:114–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.04.017

30.

Rohlin O Taeri T Netzereab S Ullemark E Djarv T . Duration of CPR and impact on 30-day survival after ROSC for in-hospital cardiac arrest-A Swedish cohort study. Resuscitation. (2018) 132:1–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.08.017

31.

Chan PS Spertus JA Krumholz HM Berg RA Li Y Sasson C et al A validated prediction tool for initial survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172(12):947–53. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2050

32.

Goldberger ZD Chan PS Berg RA Kronick SL Cooke CR Lu M et al Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Lancet. (2012) 380(9852):1473–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60862-9

33.

Harrison DA Patel K Nixon E Soar J Smith GB Gwinnutt C et al Development and validation of risk models to predict outcomes following in-hospital cardiac arrest attended by a hospital-based resuscitation team. Resuscitation. (2014) 85(8):993–1000. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.05.004

34.

McNamara RL Kennedy KF Cohen DJ Diercks DB Moscucci M Ramee S et al Predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 68(6):626–35. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.049

35.

Ebell MH Jang W Shen Y Geocadin RG . Get with the guidelines-resuscitation I. Development and validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation (GO-FAR) score to predict neurologically intact survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA Intern Med. (2013) 173(20):1872–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10037

36.

Seder DB Patel N McPherson J McMullan P Kern KB Unger B et al Geriatric experience following cardiac arrest at six interventional cardiology centers in the United States 2006–2011: interplay of age, do-not-resuscitate order, and outcomes. Crit Care Med. (2014) 42(2):289–95. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a26ec6

37.

Holmstrom E Efendijev I Raj R Pekkarinen PT Litonius E Skrifvars MB . Intensive care-treated cardiac arrest: a retrospective study on the impact of extended age on mortality, neurological outcome, received treatments and healthcare-associated costs. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2021) 29(1):103. 10.1186/s13049-021-00923-0

38.

Li H Wu TT Liu PC Liu XS Mu Y Guo YS et al Characteristics and outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest in adults hospitalized with acute coronary syndrome in China. Am J Emerg Med. (2019) 37(7):1301–6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.003

39.

Aguila A Funderburk M Guler A McNitt S Hallinan W Daubert JP et al Clinical predictors of survival in patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia following cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. (2010) 81(12):1621–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.004

40.

Kantamineni P Emani V Saini A Rai H Duggal A . Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the hospitalized patient: impact of system-based variables on outcomes in cardiac arrest. Am J Med Sci. (2014) 348(5):377–81. 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000290

41.

Yukawa T Kashiura M Sugiyama K Tanabe T Hamabe Y . Neurological outcomes and duration from cardiac arrest to the initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a retrospective study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2017) 25(1):95. 10.1186/s13049-017-0440-7

42.

Bartos JA Grunau B Carlson C Duval S Ripeckyj A Kalra R et al Improved survival with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite progressive metabolic derangement associated with prolonged resuscitation. Circulation. (2020) 141(11):877–86. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042173

43.

Lauridsen KG Lasa JJ Raymond TT Yu P Niles D Sutton RM et al Association of chest compression pause duration prior to E-CPR cannulation with cardiac arrest survival outcomes. Resuscitation. (2022) 177:85–92. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.05.004

44.

Sheen CR Kuss P Narisawa S Yadav MC Nigro J Wang W et al Pathophysiological role of vascular smooth muscle alkaline phosphatase in medial artery calcification. J Bone Miner Res. (2015) 30(5):824–36. 10.1002/jbmr.2420

45.

Millan JL Whyte MP . Alkaline phosphatase and hypophosphatasia. Calcif Tissue Int. (2016) 98(4):398–416. 10.1007/s00223-015-0079-1

46.

Kim J Song TJ Song D Lee HS Nam CM Nam HS et al Serum alkaline phosphatase and phosphate in cerebral atherosclerosis and functional outcomes after cerebral infarction. Stroke. (2013) 44(12):3547–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002959

47.

Haarhaus M Brandenburg V Kalantar-Zadeh K Stenvinkel P Magnusson P . Alkaline phosphatase: a novel treatment target for cardiovascular disease in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2017) 13(7):429–42. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.60

48.

Ndrepepa G Holdenrieder S Cassese S Fusaro M Xhepa E Laugwitz KL et al A comparison of gamma-glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase as prognostic markers in patients with coronary heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 28(1):64–70. 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.09.005

49.

Zhong C You S Chen J Zhai G Du H Luo Y et al Serum alkaline phosphatase, phosphate, and in-hospital mortality in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2018) 27(1):257–66. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.08.041

50.

Ndrepepa G Xhepa E Braun S Cassese S Fusaro M Schunkert H et al Alkaline phosphatase and prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. (2017) 47(5):378–87. 10.1111/eci.12752

51.

Chen J Mei Z Wang Y Shou X Zeng R Chen Y et al A nomogram to predict in-hospital mortality in post-cardiac arrest patients: a retrospective cohort study. Pol Arch Intern Med. (2023) 133(1):16325. 10.20452/pamw.16325

Summary

Keywords

hospital mortality, nomogram, cardiac arrest, LASSO, cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Citation

Zhang R, Liu Z, Liu Y and Peng L (2025) Development and validation of a prediction model of hospital mortality for patients with cardiac arrest survived 24 hours after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1510710. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1510710

Received

18 October 2024

Accepted

14 January 2025

Published

27 January 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Konstantinos Athanasios Gatzoulis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Reviewed by

Stergios Soulaidopoulos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Leonidas Koliastasis, CHU Saint-Pierre, Belgium

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Liu, Liu and Peng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yumin Liu liuyumin9381@126.com Li Peng pengli3669@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.