- 1Department of Cardiology, Angiology, Haemostaseology and Medical Intensive Care, Medical Faculty Mannheim, University Medical Center Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany

- 2Department of Molecular and Experimental Cardiology, Institut für Forschung und Lehre (IFL), Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

- 3Department of Cellular and Translational Physiology and Institut für Forschung und Lehre (IFL), Molecular and Experimental Cardiology, Institute of Physiology, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

Background: Women with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) often experience worse clinical outcomes compared to men, including higher rates of mortality, hospitalization, and congestion. However, the effects of sacubitril/valsartan on these outcomes, as well as on ventricular tachyarrhythmias, have not been well studied in women with HFrEF.

Methods: This study included consecutive series of patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan at University Hospital Mannheim from 2016 to 2020. Baseline and follow-up data were compared between women and men. The endpoints included all-cause mortality, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, all-cause hospitalization, and congestion.

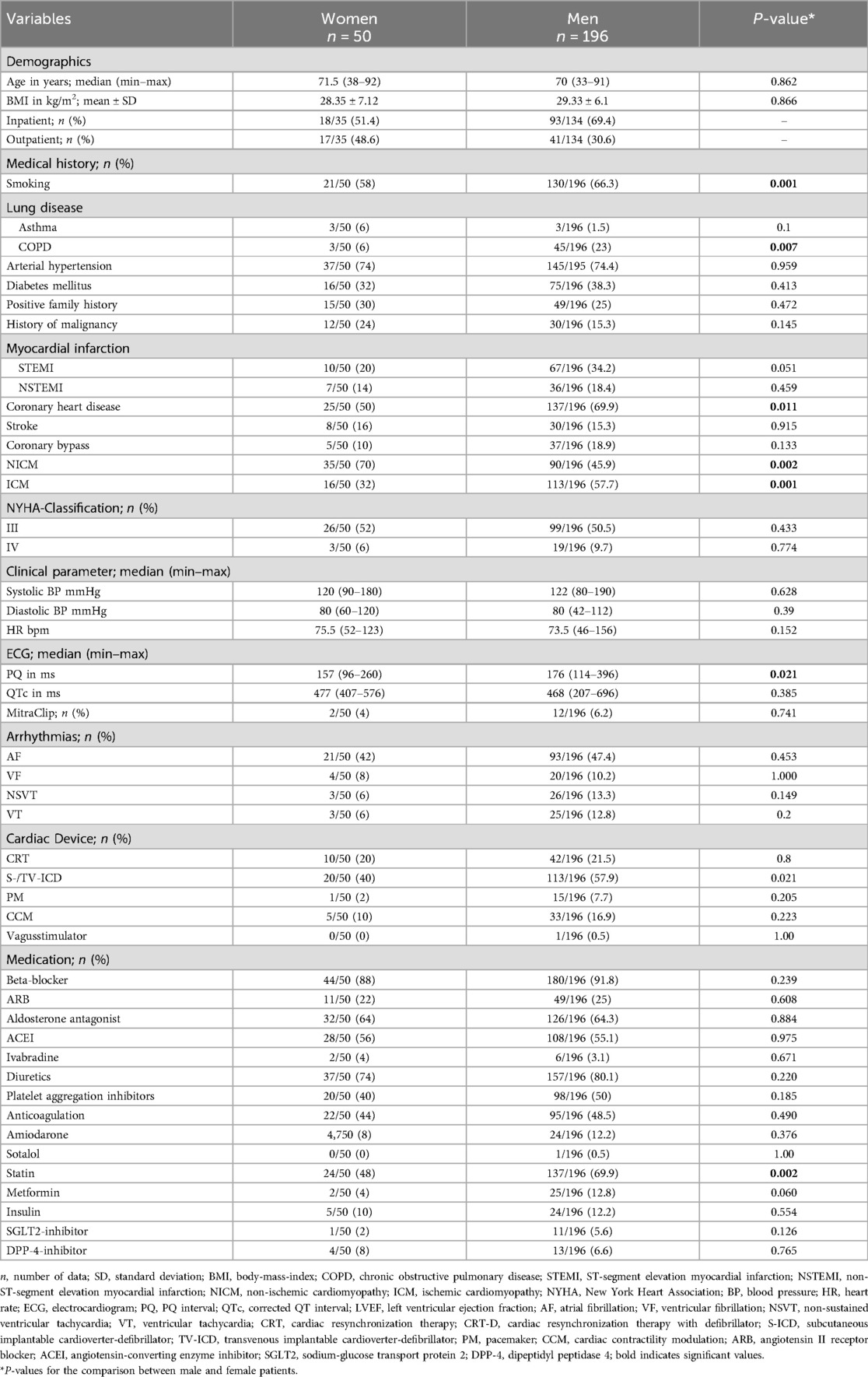

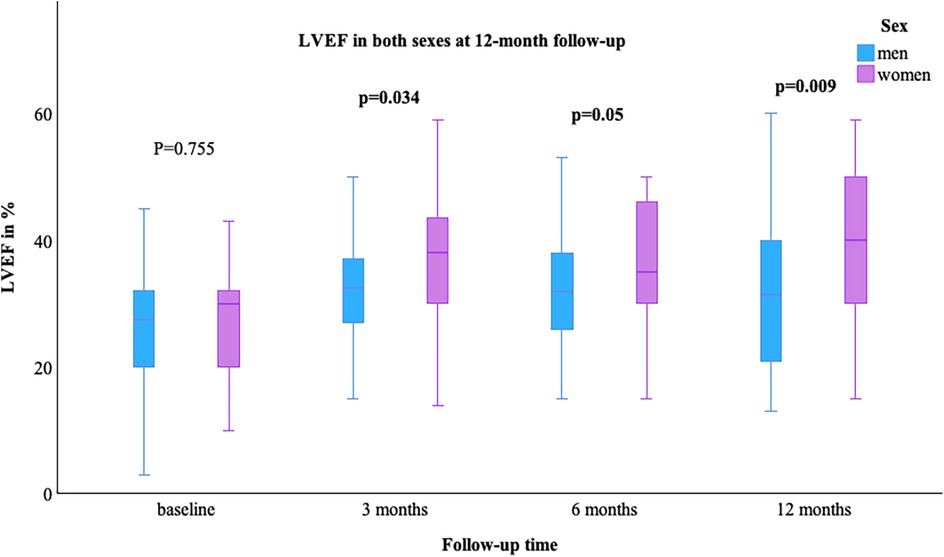

Results: A total of 246 patients were analyzed, comprising 50 (20.3%) women and 196 (79.7%) men. The study population consisted of 34.3% ambulatory patients and 65.7% hospitalized patients admitted for acute decompensated or symptomatic HF. The sex distribution was as follows: among women, 48.6% were ambulatory and 51.4% were hospitalized, while among men, 30.6% were ambulatory and 69.4% were hospitalized. Ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) was less common as a cause of heart failure (HF) in women than in men (32% vs. 57.7%, p = 0.001). During the 12-month follow-up, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) improved more significantly in women than in men, increasing from 29.0% (10.0–45.0) to 40.0% (15.0–59.0) in women (p = 0.009) compared to an increase from 28.0% (3.0–65.0) to 33.0% (13.0–60.0) in men. There were no significant differences in all-cause mortality at 12-month between women and men (4% vs. 6.7%; p = 0.742). The results indicated no significant differences between the sexes in the incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias [ventricular fibrillation [VF] and sustained ventricular tachycardia [VT]] (4.5% vs. 0.6%; p = 0.121) (2.3% vs. 3.9%; p = 1.00), hospitalizations (70.2% vs. 67.8%; p = 0.769), congestion at 12-month follow-up (11.4% vs. 10.1%; p = 0.762). Female sex was not identified as a predictor for the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or mortality rate at 12 months [hazard ratio (HR), 0.586; 95%-confidence interval (CI) 0.17–2.016; p = 0.397] (HR, 1.898; 95%-CI 0.381–9.464; p = 0.434).

Conclusion: Women with HFrEF treated with sacubitril/valsartan showed a greater improvement in LVEF compared to men, though clinical outcomes were similar across sexes. Female sex was not a predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or mortality at 12 months.

Introduction

The treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has changed within the last years, including the advent of the combination drug sacubitril/valsartan (1–5). In the PARADIGM-HF trial, the combination of the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril with the angiotensin receptor antagonist valsartan demonstrated a significant reduction in the occurrence of the composite endpoint, which consisted of death, death from cardiovascular cause, and the need for hospitalization for heart failure (HF), when compared to the treatment with enalapril alone (6). While women have a lower risk of developing HFrEF, men have an 84% higher relative risk (7). In addition, women have a lower risk of first HF hospitalization, cardiovascular death, and fewer comorbidities compared to men. Overall, there is an underuse of heart failure-specific or cardiovascular drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), statins, aspirin, and anticoagulants, as well as implantable devices in women with chronic heart failure (8). It remains unclear whether treatment with sacubitril/valsartan might improve the outcome of women and men with HFrEF to the same extent in a real-world setting. One study based on a real-world setting demonstrated a higher number of treatment discontinuations in women yet did not address the clinical outcome (9). A recent pooled analysis of the data from the PARADIMG-HF and the PARAGON-HF studies indicated that women may benefit from treatment, not only at low, but also at high levels of the LVEF (10). However, real-world data on treatment response to sacubitril/valsartan by sex are limited. This analysis shows real-world data in the treatment of HFrEF patients with sacubitril/valsartan according to sex. We also compared clinical outcomes including death from any cause, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, all-cause hospitalization, and congestion at 12 months.

Methods

A total of 245 consecutive patients were included in the study at the Department of Cardiology, Angiology, Haemostaseology and Medical Intensive Care, University Medical Center Mannheim, Heidelberg University. These patients were diagnosed with HFrEF in accordance with the 2016 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines (ESC) (11). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The presence of heart failure symptoms, as defined by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification system, in patients who have been optimally treated with ACEIs or angiotensin-II-receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MCRA); (2) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%; (3) implantation of cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT); and (4) receipt and tolerance of sacubitril/valsartan. Initially, patients received a dose of 24/26 mg twice daily, which was increased to 97/103 mg twice daily over a period of 3–6 weeks, contingent on tolerability.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human subjects and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty Mannheim Heidelberg University.

Data collection

The data and clinical outcomes of patients were gathered from the source data, assessed through chart review, and contacts with the outpatient practice at follow-up. Baseline characteristics of patients presenting before sacubitril/valsartan, including demographics, medical history, NYHA classification, clinical parameters, electrocardiogram (ECG), arrhythmias assessed by querying the ICD or CRT, cardiac devices, and medications, were available. LVEF was measured using the Simpson biplane method. Laboratory parameters were also evaluated, including potassium in mmol/L, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in ml/min, troponin I (TNI) in ng/ml, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in pg/ml, hemoglobin (Hb) in g/dl, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in%. Arrhythmias [ventricular fibrillation (VF), non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), and ventricular tachycardia (VT)] were also collected. Hospitalizations, congestions, and mortality were also gathered at baseline and after the initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in women as compared to men.

Definitions

For the purposes of this study, hospitalization is defined as any readmission to our hospital. Congestion is defined as the presence of one or more fluid overload symptoms, including pulmonary rales, third heart sound, jugular venous stasis, hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, high levels of NT-proBNP, and acute depression of heart function. These symptoms are diagnosed by echocardiography and radiographic signs of decompensation.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoints were 12-month mortality and the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VF, NSVT, VT). Secondary endpoints included atrial fibrillation (AF), hospitalization, congestion, and improvement of LVEF and NYHA classification. These endpoints reflect both short- and long-term patient health and align with previous studies assessing the clinical efficacy of HF therapies.

Statistics

The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables with a normal distribution, median (min–max) for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution, and frequency (%) for categorical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess normal distribution. Continuous variables with normal and non-normal distributions were compared by student's t-test and Mann-Whitney-U-test, respectively. The chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was employed to assess categorical variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized for paired nonparametric quantitative variables. The McNemar test was applied to paired qualitative variables. A p-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Univariate analysis was employed to identify predictors of mortality and the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. The predictors with a p-value <0.05 were subjected to a multivariate regression analysis using the Cox method. The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software version 27.0.

Results

Comparison of women and men

The patients were divided into two categories according to sex: women (n = 50, 20.3%) and men (n = 196, 79.7%). The median age of women was 71.5 years [median (min–max): 38–92 years], while that of men was 70 years (33–91 years). The mean body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2 (±SD) was similar in both groups, with a mean of 28.35 ± 7.12 in women and 29.33 ± 6.1 in men. The incidence of ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) was less in women than in men (32% vs. 57.7%, p = 0.001), while the incidence of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM) was higher in women than in men (70% vs. 45.9%, p = 0.002). Baseline characteristics, including medical history, NYHA classification, clinical parameters, arrhythmias, cardiac devices, and medication, are presented in Table 1.

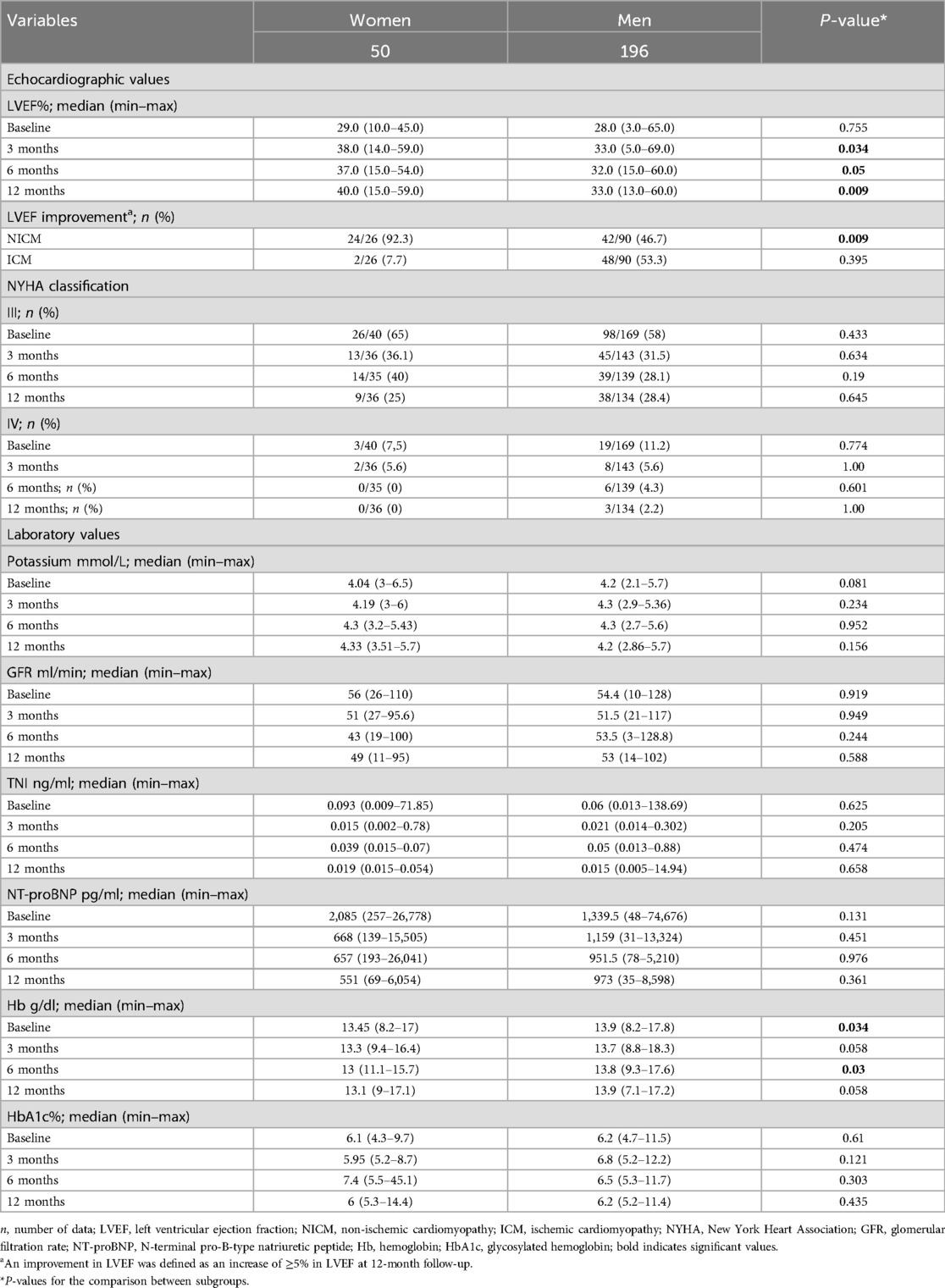

Echocardiographic values, NYHA classification, and laboratory values

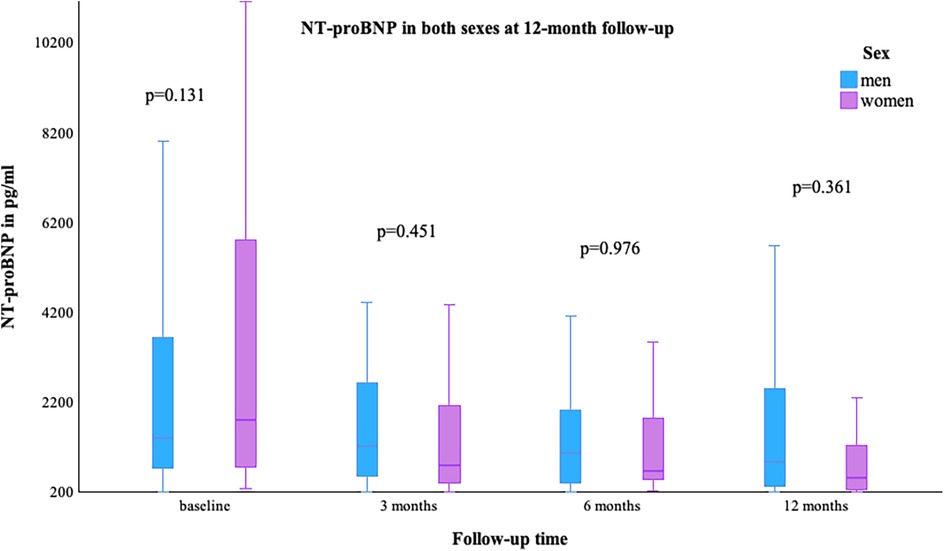

The LVEF [median (min–max)] was comparable at baseline in both sexes, with a value of 29.0% (10.0–45.0) in women and 28.0% (3.0–65.0) in men; p = 0.755. At the 12-month follow-up, an improvement in LVEF was observed in more women than men [women 40.0% (15.0–59.0) vs. men 33.0% (13.0–60.0)], Figure 1. NYHA class improved in both groups, as shown in Table 2. The value of NT-proBNP decreased in both groups. In women, the value decreased from 2,085 pg/ml (257–26,778) to 551 pg/ml (69–6,054), while in men, it decreased from 1,339.5 pg/ml (48–74,676) to 973 pg/ml (35–8,598); p = 0.361, Figure 2. Table 2 presents the remaining laboratory values.

Figure 1. LVEF in both sexes at 12-month follow-up. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; bold indicates significant values.

Table 2. Echocardiographic, LVEF improvement, laboratory, and NYHA classifications in women versus men with hFrEF at baseline and 12-month follow-up after sacubitril/valsartan.

Clinical outcomes

The mortality rate (primary endpoint) was comparable in both sexes at the 12-month follow-up (4% vs. 6.7%; p = 0.742). Ventricular tachyarrhythmias at the 12-month follow-up were comparable between the two groups (VF: 4.5% vs. 0.6%; p = 0.121; VT: 2.3% vs. 3.9%; p = 1.00). Hospitalization and congestion at the 12-month follow-up were also comparable in both sexes following the initiation of sacubitril/valsartan, as shown in Table 3.

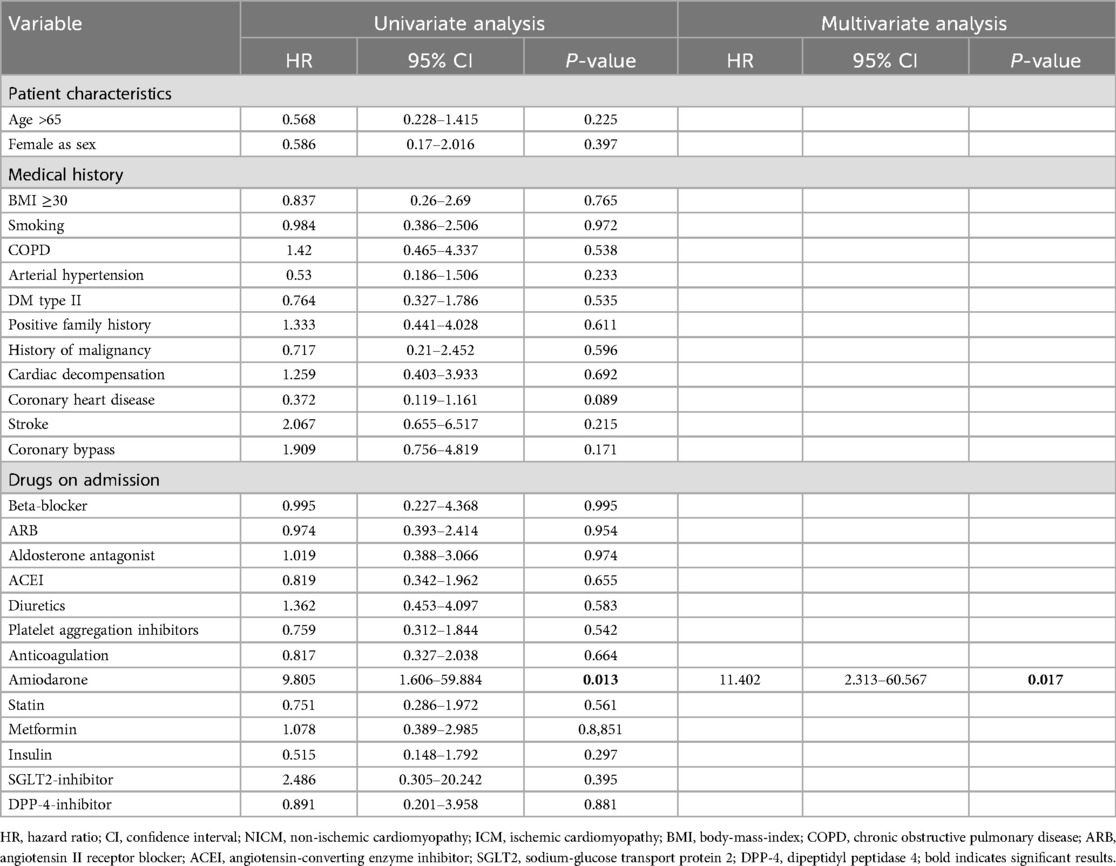

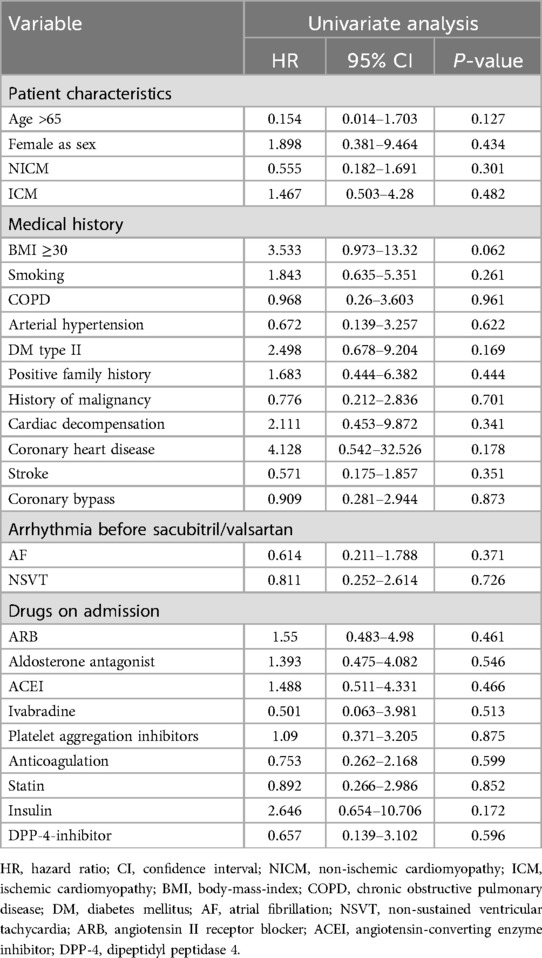

Predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and mortality

Female sex was not identified as a predictor for the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or mortality rate at 12 months; hazard ratio (HR) 0.586 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17–2.016; p = 0.397] for ventricular tachyarrhythmias; HR 1.898 (95% CI 0.381–9.464; p = 0.434) for mortality rate. However, amiodarone was identified as a negative predictor for the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias at the 12-month follow-up (HR 11.402 (95% CI 2.313–60.567; p = 0.017), Tables 4, 5.

Discussion

The present study examines the impact of sacubitril/valsartan on women and men over a 12-month period. The primary findings of this study are as follows: (1) Female sex was not identified as a predictor for the occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or mortality. (2) Mortality, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, hospitalization, and congestion were comparable in both sexes. (3) There was a significantly greater improvement in LVEF in women than in men.

Sex differences represent a traditional risk factor, as well as sex-specific risk factors that influence the prevalence and manifestation of HF in unique ways. Ischemic heart disease, which results in myocardial dysfunction and ICM, is the primary cause of HFrEF. The majority of patients with HFrEF are men, while women tend to display heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (12). The reasons for this finding remain unclear. Several biological, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics are discussed in generating this observation. Among these are differences in heart morphology and structure of women and men, a lower incidence of ischemic heart disease but a higher mortality rate due to acute myocardial ischemia in women, an influence of sex hormones and their receptors, and finally, an influence of the maternally inherited mitochondria on the cardiovascular system (12). All of them being in part the reason for the Yentl Syndrome. The unequal distribution of sexes among patients with HFrEF is exemplified by the fact that even the large PARADIGM-HF study, which introduced sacubitril/valsartan as a treatment for HFrEF, demonstrated an unequal number of women and men (13). In our study, fewer women than men were present, although the enrollment process specifically included each patient starting on sacubitril/valsartan in our hospital. In accordance with the aforementioned primary etiology of HFrEF, our study revealed that coronary artery disease and ICM were less prevalent in women than in men. Despite the potential efficacy of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and novel thienopyridines in the treatment of ICM, NICM may result from tachycardiomyopathy, myocarditis, or other potentially reversible conditions with higher recovery rates. This also explains the observed differences in LVEF improvement, with women demonstrating a higher rate of improvement than men. Furthermore, we postulated that the prevalence of scar tissue in ICM patients is higher than in NICM. Consequently, the improvement in LVEF observed in women is attributable to a higher incidence of NICM in this group. Previous study has also reported that patients with HFrEF showed an improvement in LVEF after the initiation of sacubitril/valsartan therapy (14). Notably, in a smaller subset of our cohort from a prior study, women demonstrated greater LVEF improvement than men at the 12-month follow-up (15). While another study has identified female sex as an independent predictor of functional class improvement, our findings do not support this association (16).

The clinical outcomes, including mortality and hospitalization, were found to be comparable in both groups, as corroborated by the findings of our study (17). In a meta-analysis, women and men with HFrEF exhibited similar rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalizations (17). A different study found that women with HFrEF were more likely to be hospitalized and to have NYHA classes III or IV than men while being treated with ACEI and ARB, but not sacubitril/valsartan. Furthermore, other comorbidities were observed in women, including anemia (12). Registry data indicated that female sex was a predictor of functional class improvement (16). However, Dewan et al. reported that women with HFrEF exhibited a more unfavorable outcome than men (8). Nevertheless, further studies with a larger number of women are required to ascertain the long-term outcomes of women with HFrEF.

Regarding the risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, female sex was not identified as a predictor. In general, it has been reported that the initiation of sacubitril/valsartan was associated with a lower degree of VT/VF, resulting in a reduction in the number of ICD interventions (18). Moreover, sacubitril/valsartan was found to reduce ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate ICD shocks as well as cardiac arrest in patients with HFrEF compared to ACEIs and ARBs (19–23). Another study demonstrated that NICM patients with reduced EF and ICD undergoing sacubitril/valsartan treatment experienced a reduction in the incidence of both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, along with an improvement in ICD atrial electrical parameters (24). In addition, sacubitril/valsartan was found to be associated with a reduction in acute systemic inflammatory markers, as well as a reduction in total scar and border zone mass on late gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with decreasing the risk of ventricular arrhythmias (25). However, other studies have reported no effect of sacubitril/valsartan on arrhythmias (26). The beneficial effect on ventricular arrhythmias may be attributed to a direct pharmacological effect of sacubitril/valsartan on cardiac reverse remodeling and/or small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel type 2 (KCNN2)-associated electrical remodeling (27, 28). However, data on sex differences in HFrEF are limited.

Summarizing, the long-term mortality rate was comparable between women and men. The improvement in LVEF observed in women may be attributed to a variety of factors, including different etiologies. However, it is also possible that other, as yet unknown, reasons may be responsible.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFrEF, regardless of sex. Moreover, female sex was not identified as a predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or mortality. However, LVEF showed a more pronounced improvement in women, which may be due to the higher prevalence of NICM in this group.

Study limitations

This study is a retrospective single-center study with a limited follow-up period and a small number of patients. LVEF was not systematically evaluated using, for example, cardiac magnetic resonance tomography. NYHA class was evaluated without using a qualitative evaluation questionnaire. Some patients did not receive the target dose in ambulatory practice. LVEF was evaluated by the same cardiologists to reduce the intra- and inter-observer variability. Therefore, caution is required when interpreting the data. Furthermore, it is not possible to exclude the possibility of bias due to unknown confounders, given the retrospective nature of the study. The documentation of arrhythmias was conducted via device interrogation. However, this study represents real-world data, which provides valuable insights into the efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan in clinical practice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Mannheim Heidelberg University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CK: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. JD: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. CP: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. TS: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MB: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KS: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. IE-B: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. IA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. El-Battrawy I, Demmer J, Abumayyaleh M, Crack C, Pilsinger C, Zhou X, et al. The impact of sacubitril/valsartan on outcome in patients suffering from heart failure with a concomitant diabetes mellitus. ESC Heart Fail. (2023) 10(2):943–54. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14239

2. Abumayyaleh M, Demmer J, Krack C, Pilsinger C, El-Battrawy I, Aweimer A, et al. Incidence of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias in obese patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction treated with sacubitril/valsartan. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2023) 25(10):2999–3011. doi: 10.1111/dom.15198

3. Abumayyaleh M, Demmer J, Krack C, Pilsinger C, El-Battrawy I, Behnes M, et al. Hemodynamic effects of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction over 24 months: a retrospective study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. (2022) 22(5):535–44. doi: 10.1007/s40256-022-00525-w

4. Abumayyaleh M, El-Battrawy I, Behnes M, Borggrefe M, Akin I. Current evidence of sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Future Cardiol. (2020) 16(4):227–36. doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0002

5. Abumayyaleh M, El-Battrawy I, Kummer M, Pilsinger C, Sattler K, Kuschyk J, et al. Comparison of the prognosis and outcome of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan according to age. Future Cardiol. (2021) 17(6):1131–42. doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0213

6. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. (2014) 371(11):993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077

7. Ho JE, Enserro D, Brouwers FP, Kizer JR, Shah SJ, Psaty BM, et al. Predicting heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: the international collaboration on heart failure subtypes. Circ Heart Fail. (2016) 9(6):10.1161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003116

8. Dewan P, Rorth R, Jhund PS, Shen L, Raparelli V, Petrie MC, et al. Differential impact of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2019) 73(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.081

9. Backelin CN, Fu M, Ljungman C. Early experience of sacubitril-valsartan in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in real-world clinical setting. ESC Heart Fail. (2020) 7(3):1049–55. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12644

10. Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Packer M, Zile M, Swedberg K, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan across the Spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure. Circulation. (2020) 141(5):352–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044586

11. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37(27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

12. De Bellis A, De Angelis G, Fabris E, Cannata A, Merlo M, Sinagra G. Gender-related differences in heart failure: beyond the “one-size-fits-all” paradigm. Heart Fail Rev. (2020) 25(2):245–55. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09824-y

13. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz M, Rizkala AR, et al. Baseline characteristics and treatment of patients in prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. (2014) 16(7):817–25. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.115

14. Januzzi JL Jr, Prescott MF, Butler J, Felker GM, Maisel AS, McCague K, et al. Association of change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril-valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. (2019) 322(11):1085–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12821

15. Landolfo M, Piani F, Esposti DD, Cosentino E, Bacchelli S, Dormi A, et al. Effects of sacubitril valsartan on clinical and echocardiographic parameters of outpatients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. (2020) 31:100656. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100656

16. Vicent L, Ayesta A, Esteban-Fernandez A, Gomez-Bueno M, De-Juan J, Diez-Villanueva P, et al. Sex influence on the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan. Cardiology. (2019) 142(2):73–8. doi: 10.1159/000498984

17. Nuechterlein K, AlTurki A, Ni J, Martinez-Selles M, Martens P, Russo V, et al. Real-world safety of sacubitril/valsartan in women and men with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. CJC Open. (2021) 3(12 Suppl):S202–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2021.09.009

18. Martens P, Nuyens D, Rivero-Ayerza M, Van Herendael H, Vercammen J, Ceyssens W, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan reduces ventricular arrhythmias in parallel with left ventricular reverse remodeling in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Clin Res Cardiol. (2019) 108(10):1074–82. doi: 10.1007/s00392-019-01440-y

19. Acquaro M, Scelsi L, Pasotti B, Seganti A, Spolverini M, Greco A, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan effects on arrhythmias and left ventricular remodelling in heart failure: an observational study. Vascul Pharmacol. (2023) 152:107196. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2023.107196

20. Medeiros P, Coelho C, Costa-Oliveira C, Rocha S. The effect of sacubitril-valsartan on ventricular arrhythmia burden in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Cureus. (2023) 15(2):e34508. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34508

21. de Diego C, Gonzalez-Torres L, Nunez JM, Centurion Inda R, Martin-Langerwerf DA, Sangio AD, et al. Effects of angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition compared to angiotensin inhibition on ventricular arrhythmias in reduced ejection fraction patients under continuous remote monitoring of implantable defibrillator devices. Heart Rhythm. (2018) 15(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.11.012

22. Wang R, Ye H, Ma L, Wei J, Wang Y, Zhang X, et al. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan on reducing the risk of arrhythmia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:890481. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.890481

23. Fernandes ADF, Fernandes GC, Ternes CMP, Cardoso R, Chaparro SV, Goldberger JJ. Sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin inhibitors and arrhythmia endpoints in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Heart Rhythm O2. (2021) 2(6Part B):724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2021.09.009

24. Russo V, Bottino R, Rago A, Papa AA, Liccardo B, Proietti R, et al. The effect of sacubitril/valsartan on device detected arrhythmias and electrical parameters among dilated cardiomyopathy patients with reduced ejection fraction and implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J Clin Med. (2020) 9(4):1111. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041111

25. Martinez-Falguera D, Aranyo J, Teis A, Ferrer-Curriu G, Monguio-Tortajada M, Fadeuilhe E, et al. Antiarrhythmic and anti-inflammatory effects of sacubitril/valsartan on post-myocardial infarction scar. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2024) 17(5):e012517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.123.012517

26. El-Battrawy I, Pilsinger C, Liebe V, Lang S, Kuschyk J, Zhou X, et al. Impact of sacubitril/valsartan on the long-term incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in chronic heart failure patients. J Clin Med. (2019) 8(10):1582. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101582

27. Pozzi A, Abete R, Tavano E, Kristensen SL, Rea F, Iorio A, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan and arrhythmic burden in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. (2023) 28(6):1395–403. doi: 10.1007/s10741-023-10326-1

Keywords: sex, women, men, sacubitril/valsartan, ARNI, ventricular tachyarrhythmias

Citation: Abumayyaleh M, Krack C, Demmer J, Pilsinger C, Schupp T, Behnes M, Sattler K, El-Battrawy I, Hamdani N and Akin I (2024) Sex differences and clinical outcomes, including ventricular tachyarrhythmias, of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction treated with sacubitril/valsartan. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1503414. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1503414

Received: 28 September 2024; Accepted: 6 December 2024;

Published: 19 December 2024.

Edited by:

Anita Cote, Trinity Western University, CanadaReviewed by:

Julie KK Vishram-Nielsen, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkGordana Krljanac, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Copyright: © 2024 Abumayyaleh, Krack, Demmer, Pilsinger, Schupp, Behnes, Sattler, El-Battrawy, Hamdani and Akin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Abumayyaleh, bW9oYW1tYWQuYWJ1bWF5eWFsZWhAbWVkbWEudW5pLWhlaWRlbGJlcmcuZGU=

Mohammad Abumayyaleh

Mohammad Abumayyaleh Carina Krack1

Carina Krack1 Tobias Schupp

Tobias Schupp Michael Behnes

Michael Behnes Katherine Sattler

Katherine Sattler Ibrahim El-Battrawy

Ibrahim El-Battrawy Nazha Hamdani

Nazha Hamdani Ibrahim Akin

Ibrahim Akin