- 1Department of Psychology “Renzo Canestrari”, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2Division of Cardiology, Bellaria Hospital, AUSL Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 3Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University of Göttingen Medical Centre, Göttingen, Germany

- 4Center for Behavioral Health, Media, and Technology, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 5Department of Psychology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Background: There are few studies investigating patients’ needs in healthcare focusing on disease severity and psychological characteristics of elderly heart failure (HF) patients with multimorbidity, specifically addressed by a care manager (CM).

Aims: To explore the role of a CM dealing with elderly multimorbid HF patients’ needs/preferences according to NYHA class, ejection fraction, psychological/psychosomatic distress and quality of life (QoL), utilizing a Blended Collaborative Care (BCC) approach (ESCAPE; Grant agreement No 945377).

Methods: Cue cards, self-reported questionnaires, and a semi-structured interview were used to collect data.

Results: Twenty-five Italian patients (mean age ± SD = 77.5 ± 6.68) were enrolled between June 2021 and March 2022. The most relevant patients’ needs to be addressed by a CM were: education (e.g., on medical comorbidities), individual treatment tailoring (e.g., higher number of appointments with cardiologists) and symptom monitoring.

Conclusion: The study highlights the importance of targeting HF patients’ needs according to psychological characteristics, whose healthcare requires person-centered care with CM assistance. In view of ESCAPE BCC intervention, a CM should consider specific patients’ needs of elderly multimorbid HF patients with psychological, psychosomatic distress, particularly somatization, and lower QoL to achieve a more personalized health care pathway.

Study registration: The «Evaluation of a patient-centred biopsychosocial blended collaborative care pathway for the treatment of multi-morbid elderly patients» (ESCAPE) study has been registered at the University of Göttingen Medical Centre (UMG Reg. No 02853) and the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00025120).

1 Introduction

Elderly heart failure (HF) patients with multimorbidity usually experience both physical and psychological difficulties. Approximately 60% of elderly HF patients have at least three comorbidities, such as hypertension, heart rhythm disorders, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus and anemia (1). Furthermore, depressive symptoms are common among patients with HF, with prevalence rates ranging from 41.9% for any severity to 28.1% for moderate to severe (2). Therefore, elderly HF patients require specific health care based on their needs and preferences not only according to health-related goals. Specific needs may differ case by case and can be related to disease trajectory, symptom severity, and complexity of patients’ condition and psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety (3, 4). According to the literature, advanced New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes were found to be associated with needs of physical, psychological, social and existential support (5, 6), as well as needs related to acute symptoms management, information about the disease, alternative treatments, better communication with healthcare personnel and assistance with daily life activities (5–7). Moreover, preserved ejection fraction (EF) seems to be associated with specific treatment-related problems and needs, such as diagnostic difficulty, unclear illness perceptions and disease management complexity (8). Furthermore, existing literature underlines that psychosomatic distress, in particular allostatic overload (9), is associated with cardiovascular diseases, by affecting patients’ clinical course and outcomes (9, 10). Moreover, elderly HF patients with advanced NYHA classes report higher disheartenment within demoralization and lower quality of life (QoL) (11, 12).

The Collaborative Care (CC) approach which is based on the widely-used and evidence-based Chronic Care Model (CCM) (13) has been shown effective as a health care support for chronically ill patients such as those affected by HF, who often also present with somatic and mental comorbidities (14, 15). CC aims to guide patients through fragmented medical and nursing services, effectively enhance their self-management and use informal support services. On the basis of previous literature, the ESCAPE project defines a care manager (CM) as a trained health provider (typically a nurse) in different local healthcare settings, who plays a specific role in educating and discussing patient's care needs through a proactive, shared-decision approach to improve patients’ self-management. Specifically, a CM should implement individual care plan by integrating both patient's preferences and healthcare needs in prioritizing multiple treatments and behavior modification, monitoring symptoms, coordinating care across formal carers, connecting patients with external resources, motivating and supporting patients in behavioral change (16).

Pertaining to the Italian National Health Service, the role of a CM has not been widely implemented. Although a variety of models based on CCM have been studied across Italy (17–19), only few reported CM involvement in chronic care management of HF patients. For example, the “Leonardo Project” introduced a trained nurse as CM in primary healthcare settings in order to test the feasibility of disease and care management programs among patients with HF, as well as with other chronic illnesses. In this project, CM performed initial and follow-up assessments at patients’ home, educated patients on specific conditions, implemented individual care plan with consideration of patients health-related goals, assisted with service coordination and provided one-to-one coaching session to address individual patients’ concerns and aims (17). The study suggested that a cooperative and collaborative team of physicians, specialists, CMs and patients was beneficial for patients’ self-management skills, changes in health-related behaviors and increased patients’ disease-related knowledge (17).

Although a previous study within the ESCAPE project (20) acknowledged the potential role of the CM in collecting and addressing needs and preferences of elderly HF multimorbid patients in view of Blended Collaborative Care (BCC), to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the potential role of CMs in addressing those patients’ needs, according to HF severity and psychological burden.

2 Materials and methods

The aim of the present study was to explore the role of a CM in addressing patients’ needs and preferences according to disease severity (e.g., NYHA class and ejection fraction <40%), psychological/psychosomatic distress and QoL.

2.1 Design

This study represents an exploratory descriptive cross-sectional hypothesis-generating research. It refers to the Patient Public Involvement phase within the framework of a large, international and multi-center trial entitled “Evaluation of a patient-centered biopsychosocial blended collaborative care pathway for the treatment of multi-morbid elderly patients” (ESCAPE project; Horizon 2020; Grant Agreement No. 945377). The study has been registered at the University of Göttingen Medical Centre (UMG Reg. No. 02853) and the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00025120). The detailed description of ESCAPE project is available elsewhere (16). The present study followed the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by all the local Ethics Committees. All participants were fully informed about the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, confidentiality and anonymity, and they all gave their written consent to participate.

2.2 Sample

Between June 2021 and March 2022, a convenience sample, including 25 elderly outpatients diagnosed with HF, was enrolled at the Division of Cardiology of Bellaria Hospital in Bologna (Italy). Inclusion criteria were: (a) clinically confirmed chronic HF, (b) at least two other somatic chronic comorbidities, (c) age ≥ 65 years, (d) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (a) life expectancy less than one year due to other medical conditions than HF, (b) communication difficulties (speech, hearing, no means of contact such as telephone), (c) bipolar disorder, active suicidality, schizophrenia, and dementia. The local Ethics Committee approved the study.

2.3 Assessment

The assessment procedure in the current study was based on ESCAPE project protocol (16), supplemented by the inclusion of the Semi-Structured Interview based on the revised version of Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR-R) (16) to assess the presence of psychosomatic syndromes, such as allostatic overload and demoralization, which represented a deviation from the ESCAPE protocol.

2.3.1 Anamnestic data

Socio-demographic data and clinical characteristics were collected by patient self-report with a specifically designed questionnaire, which included information on age, gender, residence, educational, marital and occupational status, as well as physical measurements (e.g., weight and height), number of comorbidities and duration of HF.

2.3.2 Disease severity

NYHA classes were investigated through medical records consultation. The classification system categorizes HF into four classes, ranging from no symptoms and no physical activity limitations (Class I) to severe limitations with symptoms even at rest (Class IV).

2.3.3 Systolic function

Ejection fraction has been defined as “low” (EF ≤ 40%), mid-range (41–49) and “preserved” (EF ≥ 50%) (21), and it has been collected through medical records.

2.3.4 Psychological distress

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) (22), a self-rated measure to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms, was used. GAD-7 score can range from 0 to 21, since each of the 7 items can be scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The total scores are categorized as follows: minimal/no anxiety (0–4), mild anxiety (5–9), moderate anxiety (10–14), or severe anxiety (15–21) (23). For the purposes of this study, a score of 5 was set as a cut-off to divide the sample into sub-groups according to the presence of “mild-severe anxiety” (≥5) vs. “no anxiety” (<5).

Patient Health Questionnaire, 9 items (PHQ-9) (24), a self-report measure to assess the severity of depression symptoms, was used. PHQ-9 score can range from 0 to 27, since each of the 9 items can be scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (24). The total scores are categorized as follows: minimal/no depression (0–4), mild depression (5–9), moderate depression (10–14), or severe depression (15–27) (25). For the purposes of this study, a score of 5 was set as a cut-off to divide the sample into sub-groups according to the presence of “mild-severe depression” (≥ 5) vs. “no depression” (<5).

2.3.5 Psychosomatic distress

Patient Health Questionnaire, 15 items (PHQ-15) (26), a self-report measure to assess the severity of somatic symptoms, was used. PHQ-15 score can range from 0 to 30, since each of the 15 items can be scored from 0 (not bothered at all) to 2 (bothered at all). The total scores are categorized as follows: minimal/no somatization (0–4), mild somatization (5–9), moderate somatization (10–14), or severe somatization (15–30) (25). For the purposes of this study, a score of 5 was set as a cut-off to divide the sample into sub-groups according to the presence of “mild-severe somatization” (≥5) vs. “no somatization” (<5).

The Semi-Structured Interview based on the revised version of Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR-R) (27); to investigate allostatic overload and demoralization was used. The instrument reported good levels of reliability and validity (28), and the joint application of the DCPR and DSM-5 has been shown to improve the identification of psychological problems in patients with a variety of medical disorders (9, 29, 30).

2.3.6 Quality of life

The European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions, 3 Level Version (EQ-5D-3L) (31), represents a self-report measure to assess quality of life according to five questions addressing mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. It consists of 5 items, each with response options on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (no problem) to 3 (extreme problems). The raw score is transformed in an index (from 0 to 1) in order to be compared with normative data, which were calculated among general population in five European countries, including Italy (32). An additional item, the European Quality Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), has been included in order to evaluate perceived health status. The respondent has to mark, in a vertical scale ranging from 0 (“the worst health you can imagine”) to 100 (“the best health you can imagine”), his/her current health status (31). For the purposes of this study, patients were allocated to “low” QoL/perceived health or “good” QoL/perceived health group, respectively, according to normative data stratified by age and sex (32).

2.3.7 Patients’ needs

We used cue cards to identify patients’ needs that can be addressed by a CM, as well as an interview, to collect quantitative data. The description of the cards is detailed elsewhere (20). The themes of the cards are based on BCC intervention described by Herbeck Belnap et al. (33). In order to ask questions comprehensibly, the cards were presented according to 6 main topics: education (e.g., areas patients would like to get more information about, such as healthy lifestyle, different topics around the diseases, common HF comorbidities; preferred means of education), individual tailoring (e.g., areas patients would like their healthcare to be more personalized, such as medical treatment, personal life, ability to actively engage in improving own health, treatment burden), monitoring (e.g., aspects of the disease CM should keep an eye on, such as physical symptoms, medical information related to other conditions and personal life, medications prescription, adherence to treatment recommendations), support (e.g., areas in which patients need support by a CM, such as adaptation of treatment plan to daily life, health behaviors, emotional burden, communication with GP and/or informal carer), coordination (e.g., aspects a CM should help coordinate, such as updates to GP, collaboration with informal carer in patient's health management, finding specialists or community resources, specialist referrals, non-medical problems) and communication (e.g., means of communication with CM, such as in-person meetings, telephone, video calls or modern technologies) (33).

2.4 Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and the significance level was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

In the total sample, descriptive analyses were performed. Socio-demographic, medical and psychological characteristics, as well as patients’ needs and preferences, were presented as frequencies and/or means (SD). Concerning needs and preferences, only the first priority card was considered.

Chi-square test, applied to contingency tables, was used to compare different patients’ needs/preferences according to NYHA classes (I, II, III) and EF (<40% vs. ≥40%) and to evaluate the null hypothesis of independence between the different variables. If the test results to be significant (p < 0.05), then we have dependence between the two considered variables, otherwise there is no sufficient empirical evidence to reject the null hypothesis of independence.

Chi-square test, applied to contingency tables, was also used to compare different patients’ needs/preferences according to psychological, psychosomatic distress and QoL.

3 Results

3.1 Description of the sample

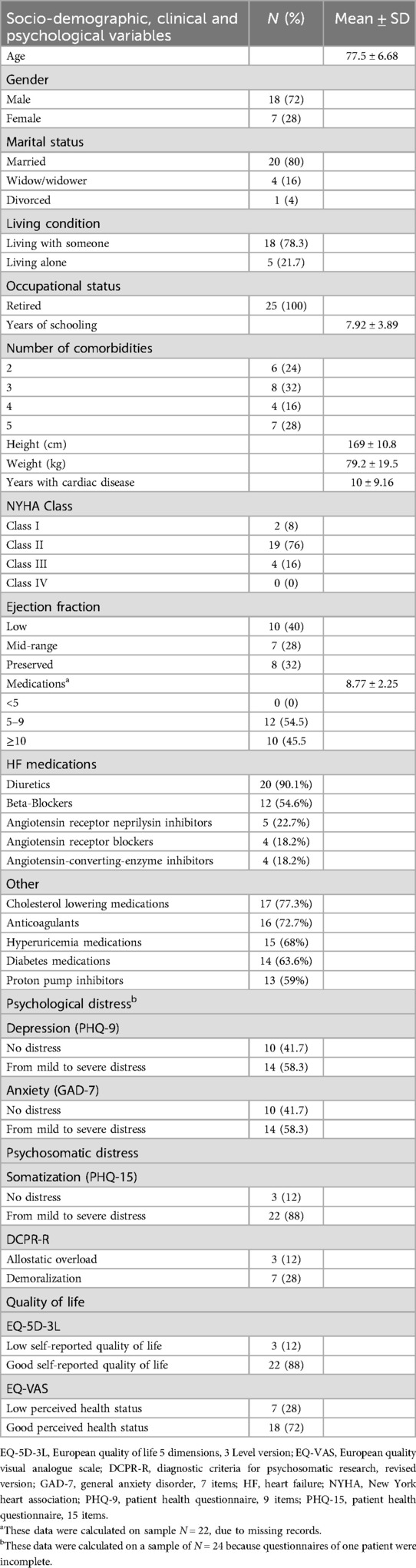

The present sample (N = 25) is characterized by 72% of men, with a mean age of 77.5 (SD = 6.68), ranging from 65 to 89 years. Regarding participants’ education, the average school attendance was 7.92 (SD = 3.89) years. Of all patients, 78.3% confirmed living with someone, whereas 21.7% lived alone. Most of the participants (76%) reported at least 3 comorbidities, 76% had NYHA II class and 40% had low (<40%) ejection fraction. All patients in the sample were prescribed with ≥5 medications, with 45.5% of them taking ≥10 medications. In terms of HF medications, 90.1% of the patients were prescribed diuretics, 54.6% beta-blockers, and 22.7% angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs). As for other common medications, the prevalence of cholesterol-lowering agents (77.3%), anticoagulants (72.7%), hyperuricemia (68%) medications, diabetes medications (63.6%), and proton pump inhibitors (59%) was also notable. Among all patients, 58.3% reported depression and anxiety. Regarding psychosomatic distress, 12% reported allostatic overload and 28% demoralization. The majority of the participants (88%) reported somatization. Only 12% of the patients self-reported low QoL, whereas 28% reported low perceived health status (Table 1).

3.2 Patients’ needs

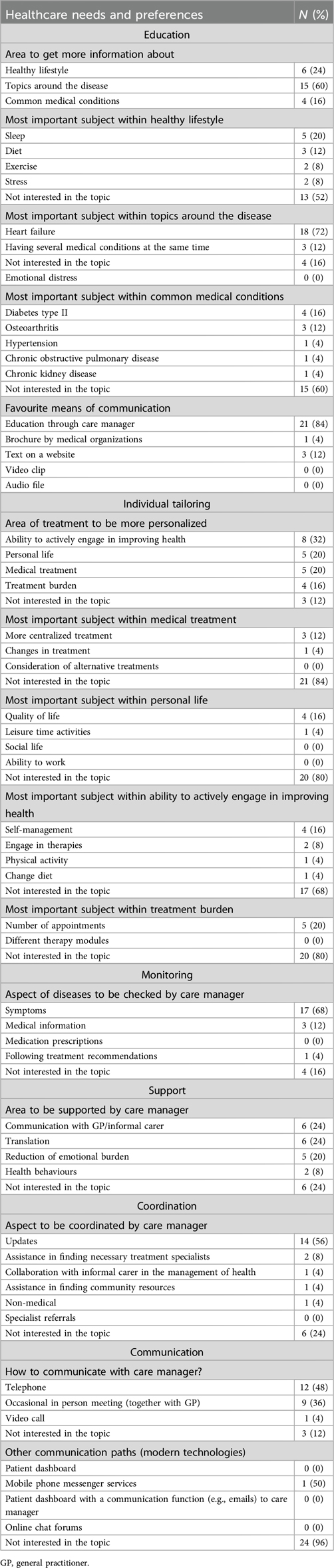

The most frequent patients’ needs within each area are presented in Table 2.

3.3 Specific patients’ needs in association with disease severity, ejection fraction, psychological, psychosomatic distress and quality of life

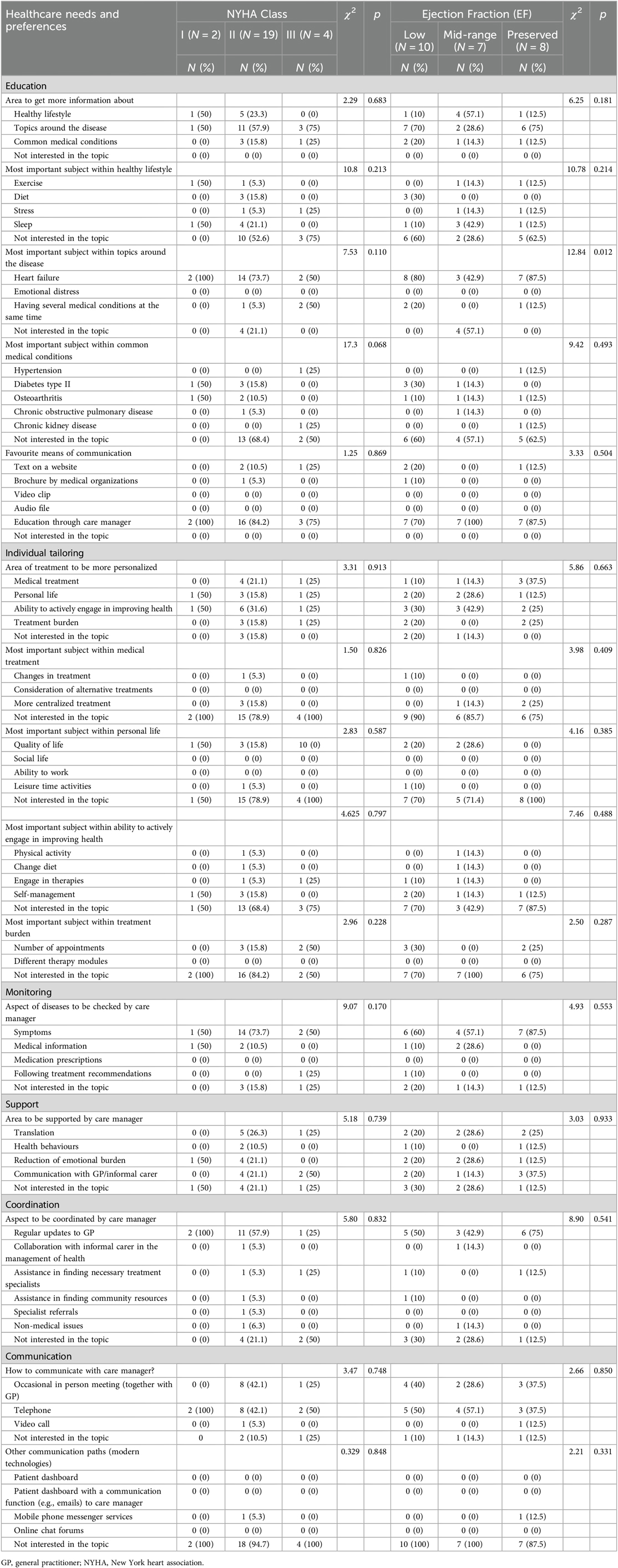

According to disease severity (NYHA class and EF), patients did not differ in their report of patients’ needs to be directly or indirectly addressed by a CM (Table 3). However, depending on systolic function impairment (i.e., EF), most of the patients preferred to get information from CM about HF (χ2 = 12.8; p = 0.012) (Table 3).

Table 3. Needs And preferences according to disease severity: NYHA classes and ejection fraction (EF).

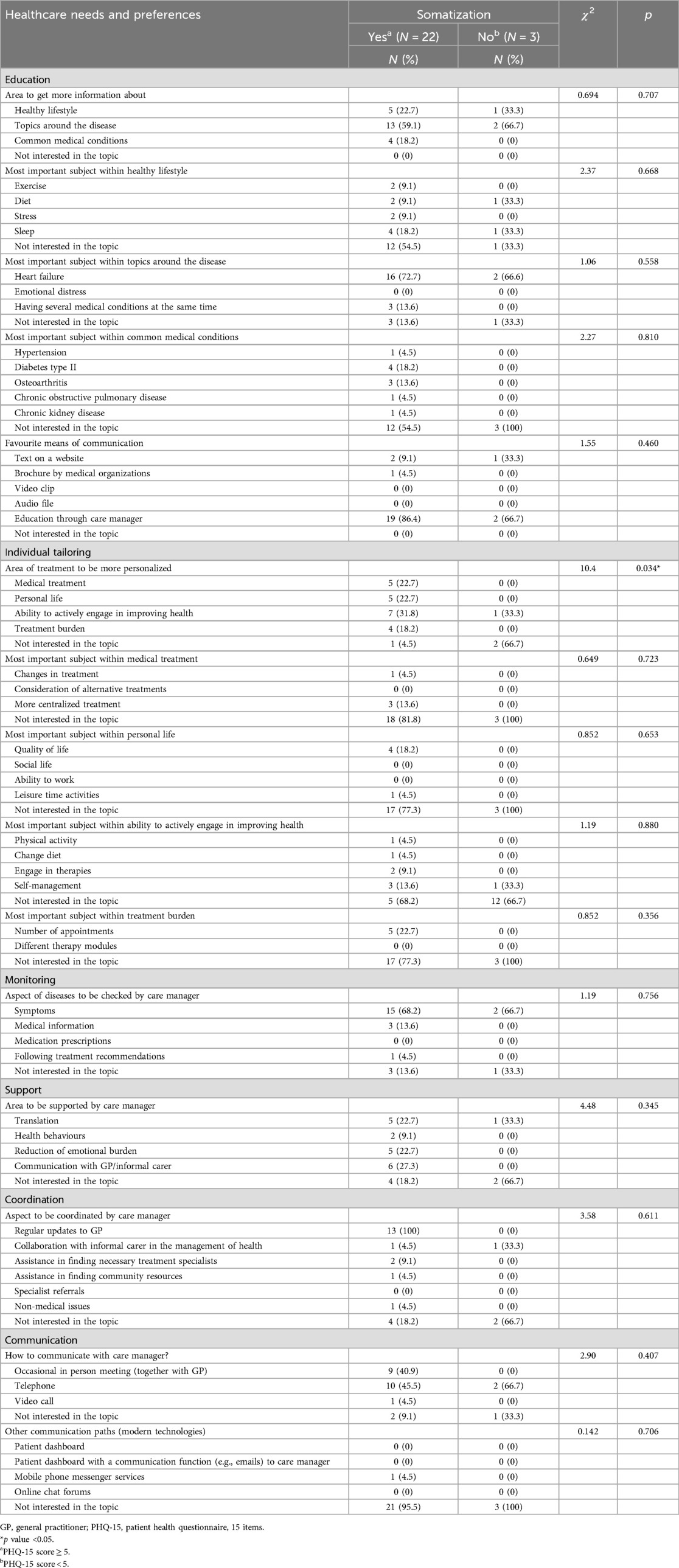

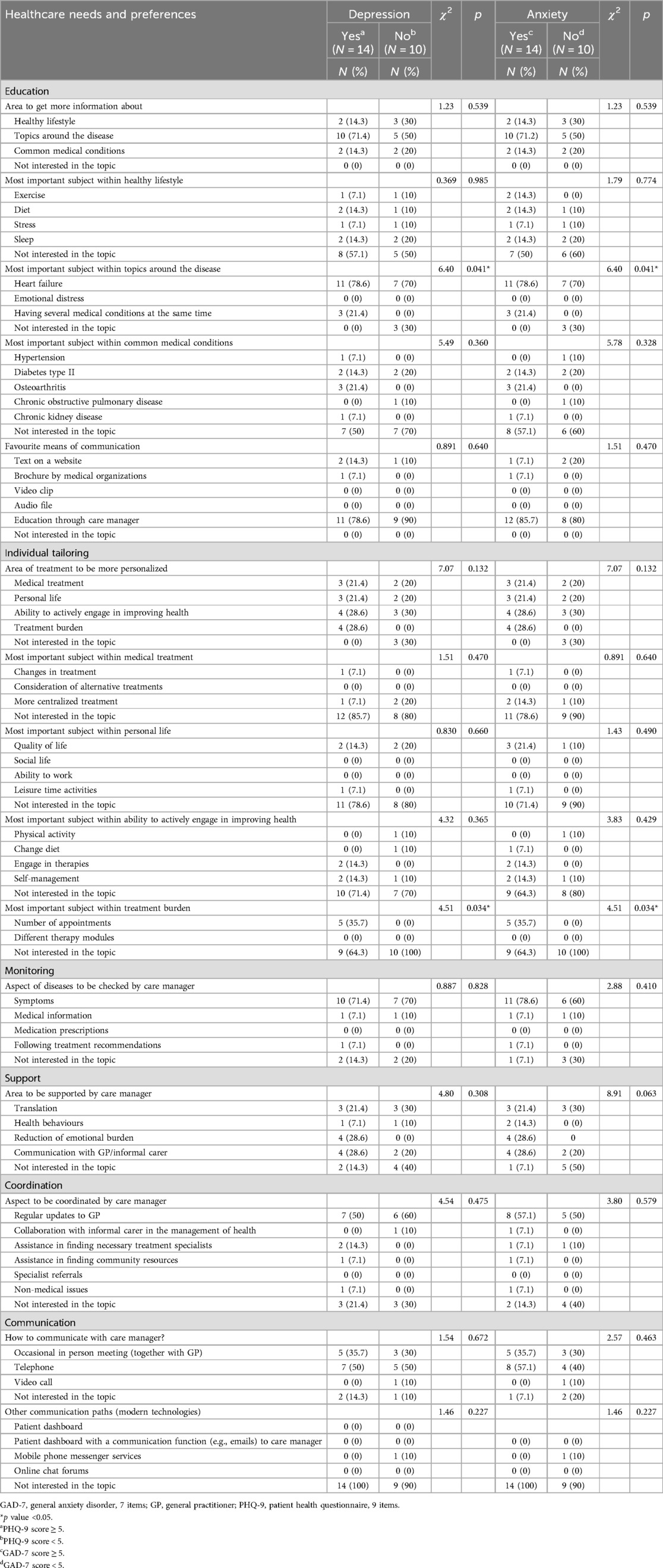

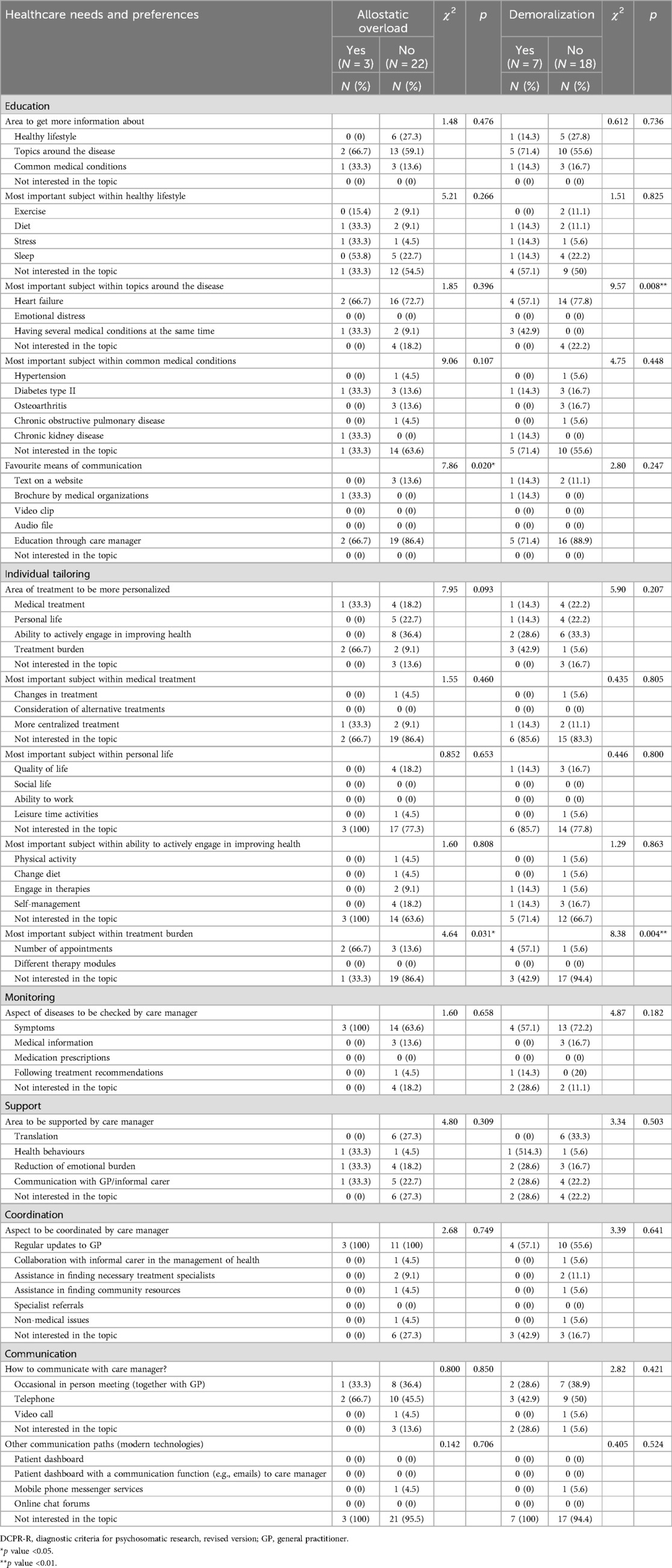

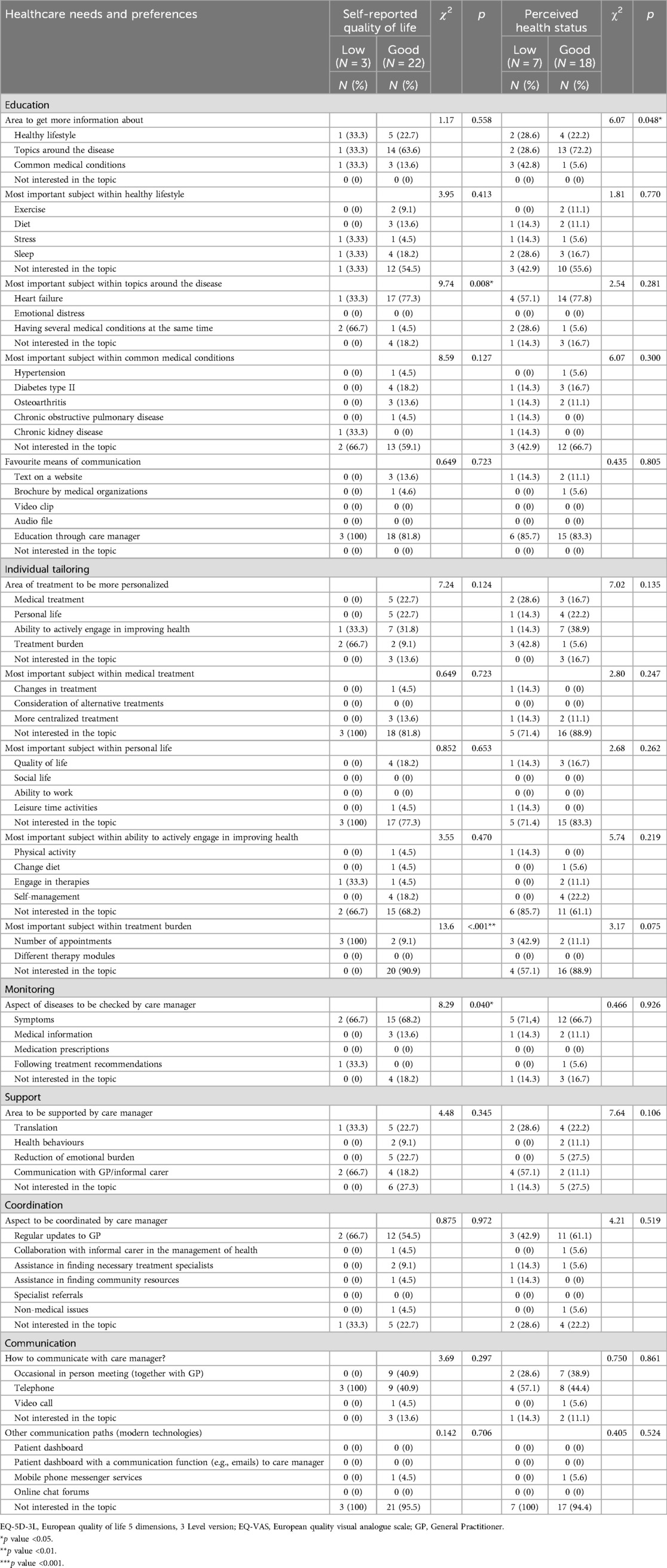

Among the six topics considered, patients experiencing psychological distress, psychosomatic complaints, and low QoL expressed different patients’ needs related to education, individual treatment tailoring and monitoring. These needs were to be directly or indirectly addressed by a CM (Tables 4–7).

Table 4. Needs and preferences according to psychological distress: depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7).

Table 5. Needs and preferences according to psychosomatic distress: allostatic overload and demoralization (DCPR-R).

Table 7. Needs and preferences according to self-reported quality of life (EQ-5D-3L) and perceived health status (EQ-VAS).

Specifically, as to the topic of education, most of the patients with anxiety (78.6%) and depression (78.6%) preferred to get information on their comorbidities in addition to HF (χ2 = 6.40; p = 0.041) (Table 4). With regards to the topic of individual tailoring, even though all the patients without psychological distress (100%) and more than a half of patients with depression (64.3%) and anxiety (64.3%) were not interested in personalizing their treatment in terms of addressing treatment burden (χ2 = 4.51; p = 0.034), all the participants who were interested in the mentioned issue reported depression and anxiety; in particular, these patients asked to get a higher number of appointments with their cardiologists (Table 4).

As to psychosomatic distress, compared with patients without DCPR demoralization who mainly (77.8%) expressed the need for more information exclusively on HF (topic of education), demoralized participants were interested in getting information not only on HF (57.1%), but also regarding their multimorbidity (42.9%) (χ2 = 9.57, p = 0.008). Moreover, as to the topic of individual tailoring, even though 42.9% of demoralized patients were not interested in personalizing their treatment in terms of addressing treatment burden, 80% of those participants who would like more frequent appointments with cardiologists presented with demoralization (χ2 = 8.38; p = 0.004) (Table 5). On the same vein, two-thirds of patients with DCPR allostatic overload (66.7%) expressed the need of a higher number of visits (χ2 = 4.64; p = 0.031) (Table 5). Furthermore, this sub-group of patients would like to receive health-related information through brochure by medical organization (topic of education), in addition to education through CM him/herself, differently from patients without the same syndrome who preferred text on a website in addition to in-person education by CM (χ2 = 7.86; p = 0.020) (Table 5). Finally, compared with participants without somatic complaints, patients with PHQ-15 somatization were more interested in tailoring their treatment (χ2 = 10.4, p = 0.034), in particular in learning how to improve their own ability to actively enhance their health (31.8%) (Table 6).

Compared with most of the patients (77.3%) with good self-reported QoL (EQ-5D-3L) who preferred education on HF, two-thirds of those with low QoL required information about having several medical conditions at the same time (χ2 = 9.74, p = 0.008) (Table 7). Moreover, patients with low self-reported QoL expressed the need of increasing the frequency of appointments with the cardiologists (χ2 = 13.6; p < 0.001) (topic of individual tailoring), and having physical symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath, weight gain, blood pressure, glucose, LDL and other lab results) and treatment recommendation adherence monitored by CM (χ2 = 8.29, p = 0.040) (Table 7). Finally, compared with patients with good perceived health status (EQ-VAS) who mainly required more information about issues related to their medical condition (72.2%), those with low perceived health status reported heterogeneous educational needs concerning also comorbidities (such as hypertension, type II diabetes, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease) and lifestyle (χ2 = 6.07; p = 0.048) (Table 7).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge few studies investigated HF patient's needs and preferences within a BCC approach, including recognition of CM role in collecting patients’ needs and preferences (20). However, no studies explored and described CM's role in addressing those healthcare needs according to disease severity, psychological, psychosomatic distress and QoL, in elderly HF patients with multimorbidity. Our study is the first one that tries to fill this gap in the literature.

In contrast to existing literature, in our study no significant differences in patients’ preferences and needs in association with NYHA classes were reported. However, the majority of the patients in the current study belonged to NYHA II class, whereas in the literature differences in needs were reported mainly between I-II and III-IV classes (5, 6). The results regarding EF showed that HF patients, based on their EF category, preferred receiving education and information about their condition from a CM. These findings are consistent with previous research, indicating that HF patients have treatment-related preferences linked to their EF, its associated symptoms, and management needs (8). Indeed, patients with low EF, which is associated with symptoms such as chest pain, heart palpitations, coughing (sometimes with blood), fatigue, and dizziness, might have different health management needs and preferences compared to those with mid-range or preserved EF. Additionally, the observed differences may be attributed to the higher prevalence of low EF among younger men compared to preserved EF, which is more commonly reported among older women (34).

Patients with psychological and psychosomatic distress, as well as low QoL, reported patients’ needs to be addressed by CM related to education, individual treatment tailoring, and monitoring. Most of the patients, especially those with psychological distress, demoralization and low self-reported QoL preferred to tailor their treatment with CM assistance by getting a higher number, in terms of frequency, of appointments with the cardiologists and receiving information about HF or their medical comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes type II, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, in addition to HF. According to the literature (35, 36), patients with a chronic disease re-evaluate the importance of communication with their GP, especially in adaptation of their treatment plans into their daily life and living conditions, due to perceived loss of independence. Presence of comorbidities is associated with psychological distress and decreased QoL (37). Since in our study the majority of the patients presented at least three comorbidities, this may explain why the patients requested from CM additional information about them.

Patients with allostatic overload preferred to receive health-related information also from brochures by medical organizations, in addition to education by CM. The results are in line with existing literature that suggests that allostatic overload is associated with cognitive loss, in particular with advanced age (38, 39), which could result in difficulties in memorizing and processing information related to complex treatment plans. Also, patients with low self-reported QoL preferred CM's support regarding symptom monitoring, such as shortness of breath, weight gain, blood pressure, glucose, LDL and other lab results, in addition to assistance with following treatment recommendations. The results of the present study are also in line with existing literature, as majority of the elderly patients reported at least 3 comorbidities in addition to HF that is associated with poor treatment coordination and reduced health-related quality of life (40, 41).

Despite that psychological and psychosomatic distress, as well as low QoL are common among elderly HF multimorbid patients, according to our knowledge there is a lack of information about CM's role in addressing these patients’ needs and preferences. The results of the current study highlight the importance of targeting patients with their needs whose healthcare requires person-centered care (42) with CM assistance. CM inclusion in complex treatment plans that address somatic and mental comorbidities are suggested to benefit quality of the provided health care (43) and increase patients’ satisfaction with treatment management. Furthermore, coordinated by a nurse, healthcare for elderly and multimorbid HF patients is suggested to be effective by RCTs in US (14). However, in the Italian healthcare system comparable support by a CM is not widely available. Instead, in Italy, usually nurses, as case managers, assist patients with acute conditions at home-care level, in order to prevent further progression of patients’ illness (19, 44). Only the “Leonardo Project” tested the use of CMs in a BCC approach, who assisted patients with multiple chronic conditions, supported them in following complex treatment plans, but only for a 18 month period (17).

Finally, in the present study patients with psychological or psychosomatic distress seem to belong to two separate categories, those who are not interested in taking actions to improve their healthcare vs. those patients who expressed specific needs to be addressed by a CM. This may support findings from another qualitative international study of elderly multimorbid HF patients’ healthcare needs (45) that identified three main patients’ profiles: those who need and want support; those who actively engage in self-care and only reach out to the health care system when needed; those who feel neglected by the health care system and do not believe in professional support. The lack of interest showed by some of the patients in the present study could thus be related to the latter two profiles.

4.1 Limitations

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size that cannot be considered representative of all elderly multimorbid patients with HF. Moreover, the utilization of a convenience sampling strategy resulted in a predominance of males and absence of patients with NYHA class IV heart failure, thereby limiting the generalizability and applicability of the study findings. We acknowledge that the significance of the chi-square test results also could have been influenced by the small sample size. However, this study is preliminary and exploratory in nature and it does not intend to establish definitive correlations; instead, it aimed at informing ESCAPE-recruited CMs, in order to help them in delivering BCC. Due to a cross-sectional design of the study, this research acquires data at a singular time point, therefore constraining the capacity to establish the potential evolution of patients’ needs and preferences over time. Additionally, the absence of a control group poses difficulties to ascertain whether the identified needs and preferences are specific to elderly HF patients or common among elderly individuals with other chronic conditions. Lastly, the monocentricity of study could have affected the study's external validity. Despite all these limitations the present study gives the opportunity to focus on the role a CM may play in addressing needs in relation to severity of disease, psychological, psychosomatic distress and QoL in elderly HF patients with multimorbidity.

4.2 Conclusion

In the Italian healthcare setting, the introduction of the CM role, supported by a Specialist Team, looks promising for enhancing the care of elderly HF patients. Future studies should consider patients’ needs and preferences considering the cited associations. The results of this study may also inform researchers interested in developing holistic treatments for elderly patients suffering from multiple physical and mental health conditions.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author, CR, upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by “Comitato Etico di Area Vasta Emilia Centro, CE-AVEC” at Sant'Orsola-Malpighi Polyclinic, University of Bologna (“Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi”, Protocol N. PG0012699/2021). The study is within the scope of the Patient Public Involvement phase of the European project entitled “Evaluation of a patient-centred biopsychosocial blended collaborative care pathway for the treatment of multi-morbid elderly patients” (ESCAPE; Grant agreement No 945377). All participants were fully informed about the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, confidentiality and anonymity, and they all gave their written consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SG: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization. RS: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization. FG: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization. FB: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. AC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Investigation. GG: Writing – review & editing. BH: Writing – review & editing. DD: Writing – review & editing, Resources. SU: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. CR: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Project administration, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No 945377), within the scope of the Patient Public Involvement (PPI) phase of the “Evaluation of a patient-centred biopsychosocial blended collaborative care pathway for the treatment of multi-morbid elderly patients” (ESCAPE) trial.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1432588/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Marinescu M, Oprea VD, Nechita A, Tutunaru D, Nechita L-C, Romila A. The use of brain natriuretic peptide in the evaluation of heart failure in geriatric patients. Diagnostics. (2023) 13:1512. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13091512

2. Moradi M, Doostkami M, Behnamfar N, Rafiemanesh H, Behzadmehr R. Global prevalence of depression among heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2021) 47(6):100848. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.100848

3. Hwang B, Moser DK, Dracup K. Knowledge is insufficient for self-care among heart failure patients with psychological distress. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:588–96. doi: 10.1037/a0033419

4. Mangolian Shahrbabaki P, Nouhi E, Kazemi M, Ahmadi F. The sliding context of health: the challenges faced by patients with heart failure from the perspective of patients, healthcare providers and family members. J Clin Nurs. (2017) 26:3597–609. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13729

5. Kraai IH, Vermeulen KM, Hillege HL, Jaarsma T. Perception of impairments by patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2016) 15:178–85. doi: 10.1177/1474515115621194

6. Schäfer-Keller P, Santos GC, Denhaerynck K, Graf D, Vasserot K, Richards DA, et al. Self-care, symptom experience, needs, and past health-care utilization in individuals with heart failure: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2021) 20:464–74. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvaa026

7. Arenas Ochoa LF, González-Jaramillo V, Saldarriaga C, Lemos M, Krikorian A, Vargas JJ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with heart failure needing palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. (2021) 20:184. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00850-y

8. Sowden E, Hossain M, Chew-Graham C, Blakeman T, Tierney S, Wellwood I, et al. Understanding the management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a qualitative multiperspective study. Br J Gen Pract. (2020) 70:e880–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713477

9. Gostoli S, Bonomo M, Roncuzzi R, Biffi M, Boriani G, Rafanelli C. Psychological correlates, allostatic overload and clinical course in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). Int J Cardiol. (2016) 220:360–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.246

10. Offidani E, Rafanelli C, Gostoli S, Marchetti G, Roncuzzi R. Allostatic overload in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 165:375–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.08.026

11. Chen H-M, Tsai L-M, Shie Y-H. Demoralization syndrome affects health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients with heart failure. (2017). Available online at: https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/622029 (accessed November 15, 2022).

12. Rubio R, Palacios B, Varela L, Fernández R, Camargo Correa S, Estupiñan MF, et al. Quality of life and disease experience in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in Spain: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e053216. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053216

13. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. (1996) 74(4):511–44. doi: 10.2307/3350391

14. Bekelman DB, Hooker S, Nowels CT, Main DS, Meek P, McBryde C, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a collaborative care intervention to improve symptoms and quality of life in chronic heart failure: mixed methods pilot trial. J Palliat Med. (2014) 17:145–51. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0143

15. Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Beach SR, Celano CM, DuBois CM, Healy BC, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety disorders in patients with recent cardiac events: the management of sadness and anxiety in cardiology (MOSAIC) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2014) 174:927–35. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.739

16. Zelenak C, Nagel J, Bersch K, Derendorf L, Doyle F, Friede T, et al. Integrated care for older multimorbid heart failure patients: protocol for the ESCAPE randomized trial and cohort study. ESC Heart Fail. (2023) 10(3):2051–65. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14294

17. Ciccone MM, Aquilino A, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Sassara M, Mola E, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a disease and care management model in the primary health care system for patients with heart failure and diabetes (Project Leonardo). Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2010) 6:297–305. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s9252

18. Longhini J, Canzan F, Mezzalira E, Saiani L, Ambrosi E. Organisational models in primary health care to manage chronic conditions: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30(3):e565–88. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13611

19. Petrelli F, Cangelosi G, Nittari G, Pantanetti P, Debernardi G, Scuri S, et al. Chronic Care Model in Italy: a narrative review of the literature. Prim Health Care Res Dev. (2021) 22:e32. doi: 10.1017/S1463423621000268

20. Gostoli S, Bernardini F, Subach R, Engelmann P, Jaarsma T, Andréasson F, et al. Healthcare needs in elderly patients with chronic heart failure in view of a personalized blended collaborative care intervention: a cross sectional study. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1332356. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1332356

21. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42:3599–726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

23. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

25. Kocalevent R-D, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35:551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:258–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008

27. Fava GA, Cosci F, Sonino N. Current psychosomatic practice. Psychother Psychosom. (2017) 86:13–30. doi: 10.1159/000448856

28. Galeazzi GM, Ferrari S, Mackinnon A, Rigatelli M. Interrater reliability, prevalence, and relation to ICD-10 diagnoses of the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research in consultation-liaison psychiatry patients. Psychosomatics. (2004) 45:386–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.386

29. Piolanti A, Offidani E, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Fava GA, Sonino N. Use of the psychosocial index: a sensitive tool in research and practice. Psychother Psychosom. (2016) 85:337–45. doi: 10.1159/000447760

30. Ruini C, Ottolini F, Rafanelli C, Tossani E, Ryff CD, Fava GA. The relationship of psychological well-being to distress and personality. Psychother Psychosom. (2003) 72:268–75. doi: 10.1159/000071898

31. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. (2001) 33:337–43. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087

32. Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Shaw JW. General population normative data for the EQ-5D-3l in the five largest European economies. Eur J Health Econ. (2021) 22:1467–75. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01326-9

33. Herbeck Belnap B, Anderson A, Abebe KZ, Ramani R, Muldoon MF, Karp JF, et al. Blended collaborative care to treat heart failure and comorbid depression: rationale and study design of the hopeful heart trial. Psychosom Med. (2019) 81:495–505. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000706

34. Stewart S, Playford D, Scalia GM, Currie P, Celermajer DS, Prior D, et al. Ejection fraction and mortality: a nationwide register-based cohort study of 499 153 women and men. Eur J Heart Fail. (2021) 23:406–16. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2047

35. Abdi S, Spann A, Borilovic J, de Witte L, Hawley M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: a scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. (2019) 19:195. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1189-9

36. Parrish E. Comorbidity of mental illness and chronic physical illness: a diagnostic and treatment conundrum. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2018) 54:339–40. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12311

37. Makovski TT, Schmitz S, Zeegers MP, Stranges S, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2019) 53:100903. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.04.005

38. Crook Z, Booth T, Cox SR, Corley J, Dykiert D, Redmond P, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype does not moderate the associations of depressive symptoms, neuroticism and allostatic load with cognitive ability and cognitive aging in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0192604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192604

39. D’Amico D, Amestoy ME, Fiocco AJ. The association between allostatic load and cognitive function: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2020) 121:104849. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104849

40. Collins DM, Downer B, Kumar A, Krishnan S, Li C, Markides KS, et al. Impact of multiple chronic conditions on activity limitations among older Mexican-American care recipients. Prev Chronic Dis. (2018) 15:170358. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170358

41. Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan ECK, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2018) 17:1185–96. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1546841

42. Östman M, Bäck-Pettersson S, Sundler AJ, Sandvik A. Nurses’ experiences of continuity of care for patients with heart failure: a thematic analysis. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 30:276–86. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15547

43. Alleyne J, Jumaa MO. Building the capacity for evidence-based clinical nursing leadership: the role of executive co-coaching and group clinical supervision for quality patient services. J Nurs Manag. (2007) 15:230–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00750.x

44. Barsanti S, Guarneri F. Chronic disease management: discussing the perspectives of general practitioners in Italy. Health Serv Manage Res. (2019) 33:13–23. doi: 10.1177/0951484819871011

45. Kohlmann S, Jaarsma T, Rafanelli C, Andréeasson F, Gostoli S, Löwe B, et al. Needs of multimorbid elderly with chronic heart failure regarding a blended- collaborative care: a qualitative interview study in preparation of an intervention within the EU project ESCAPE. J Psychosom Res. (2022) 157:110871. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110871

Keywords: care manager, patient’s needs, blended collaborative care, psychological distress, psychosomatic distress, somatization, quality of life

Citation: Gostoli S, Subach R, Guolo F, Bernardini F, Cammarata A, Gigante G, Herbeck Belnap B, Della Riva D, Urbinati S and Rafanelli C (2024) Care manager role for older multimorbid heart failure patients’ needs in relation to psychological distress and quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1432588. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1432588

Received: 14 May 2024; Accepted: 2 September 2024;

Published: 30 September 2024.

Edited by:

Mitja Lainscak, University of Ljubljana, SloveniaReviewed by:

Natasa Sedlar, General Hospital Murska Sobota, SloveniaPiotr Z. Sobanski, Schwyz Hospital, Switzerland

Copyright: © 2024 Gostoli, Subach, Guolo, Bernardini, Cammarata, Gigante, Herbeck Belnap, Della Riva, Urbinati and Rafanelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chiara Rafanelli, Y2hpYXJhLnJhZmFuZWxsaUB1bmliby5pdA==

†These authors share first authorship

‡Membership of the ESCAPE Consortium is provided in the

Sara Gostoli

Sara Gostoli Regina Subach

Regina Subach Francesco Guolo

Francesco Guolo Francesco Bernardini

Francesco Bernardini Alessandra Cammarata

Alessandra Cammarata Graziano Gigante

Graziano Gigante Birgit Herbeck Belnap3,4

Birgit Herbeck Belnap3,4 Diego Della Riva

Diego Della Riva Stefano Urbinati

Stefano Urbinati Chiara Rafanelli

Chiara Rafanelli