- 1Department of Pediatrics, The Second People’s Hospital of Changzhou, Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China

- 2Department of Cardiology, Wujin Hospital Affiliated with Jiangsu University, The Wujin Clinical College of Xuzhou Medical University, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China

- 3Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The Affiliated Changzhou Second People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou, China

Background: Distal radial artery (DRA) access is an infrequent alternative access for pediatric catheterization. The feasibility of using the DRA for arterial catheterization in children depends on the vessel's size.

Objectives: This study aims to provide a reference for pediatric catheterization via DRA access by evaluating the diameter of the DRA in the anatomic snuffbox (AS).

Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of clinical and vascular ultrasound data of 412 children (ages 3–12) who were scheduled for arterial blood gas analysis via the DRA due to serious respiratory diseases between June 2023 and October 2023.

Results: The corrected DRA diameter in the AS was 1.97 ± 0.37 mm overall, with no significant difference between males (1.98 ± 0.38 mm) and females (1.95 ± 0.35 mm) (p = 0.457). The anteroposterior, transverse, and corrected DRA diameters increased significantly with age (p < 0.05). The DRA diameter was significantly smaller than the proximal radial artery (PRA) diameter (1.97 ± 0.37 mm vs. 2.05 ± 0.33 mm, p < 0.001) but larger than the ulnar artery (UA) diameter (1.97 ± 0.37 mm vs. 1.88 ± 0.33 mm, p < 0.001). The proportions of patients with a DRA diameter greater than 2.0 mm and 1.5 mm were 38.83% and 86.89%, respectively. The proportions of patients with DRA diameters >2.0 mm and >1.5 mm increased significantly with age (p < 0.01). The percentages of individuals with a DRA/PRA ratio ≥1.0 were 55.10% overall, 52.12% in males, and 58.60% in females. DRA diameter showed significant correlations with age (r = 0.275, p < 0.01), height (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), weight (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), BMI (r = 0.241, p < 0.01), wrist circumference (r = 0.354, p < 0.01), PRA diameter (r = 0.521, p < 0.01), and UA diameter (r = 0.272, p < 0.01).

Conclusion: The DRA diameter in children increases with age and size, making cardiac catheterization is theoretically feasible. Preoperative evaluation of the vessel diameter and intraoperative ultrasound-guided intervention are recommended for paediatric catheterization via the DRA access.

Introduction

In recent years, proximal radial artery (PRA) access has emerged as an alternative access to femoral artery access for arterial catheterization in children, including cardiovascular interventions and invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring (1, 2). However, vessel intima injury during catheterization via PRA access and compression hemostasis can lead to radial artery occlusion (RAO) (3). RAO in children not only limits the future use of the radial artery but also affects limb development (4).

Compared to PRA access, distal radial artery (DRA) access in the anatomic snuffbox (AS) has been associated with a decreased risk of RAO, increased patient comfort and reduced hemostatic time (5–7). This approach has gained increased attention as an alternative for cardiac catheterization in adults (5–7). From the perspective of radial artery protection, catheterization via DRA access in children seems even more important (8). However, the DRA diameter in children is smaller than in adults, which increases the difficulty of puncturing and mastering the learning curve. Additionally, sheath-to-vessel mismatch may increase the risk of vascular injury (9).

To date, few studies have evaluated the DRA diameter and the feasibility of the catheterization via DRA access in children (10). Therefore, whether catheterization via DRA access in children is safe and effective needs further evaluation. This study aims to provide a reference for clinical catheterization via DRA access in children by measuring the DRA diameter in the AS.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective review of clinical and vascular ultrasound data of children (ages 3 to 12 years) who were scheduled for arterial blood gas analysis via the DRA due to serious respiratory diseases. These children were treated at the pediatric outpatient or inpatient department of the Changzhou Second People's Hospital between June 2023 and October 2023. The exclusion criteria included children aged ≤2 years, a history of PRA or DRA puncture, a history of peripheral artery disease, or a lack of ultrasound data. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Changzhou Second People's Hospital [Approval number: (2023)YLJSA069], and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Ultrasound examination

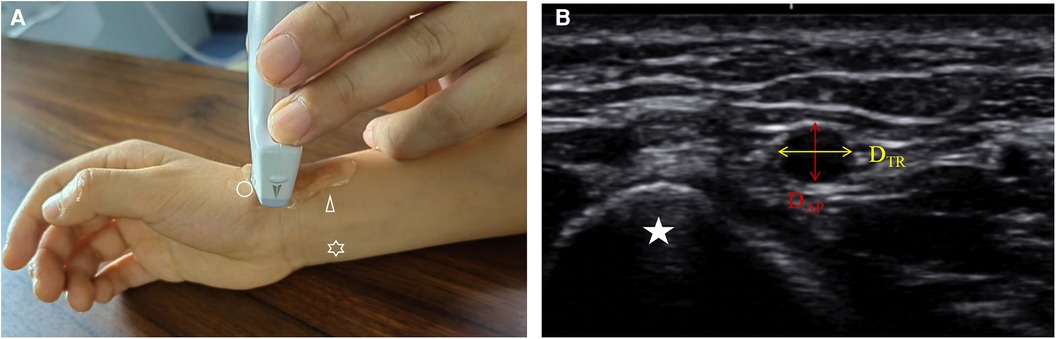

A portable ultrasound machine (Konica Minolta SONIMAGE HS1 PLUS) with a “line array” probe (18-4 MHz) was used to measure the vessel diameter. During the examination, the operators gently placed the probe on the skin using their left thumb, index finger, and middle finger. Simultaneously, the little finger was positioned on the examinee's arm as a support to reduce the pressure of the probe on the tissue. Once the cross-sectional image of the vessel was displayed on the screen, slight adjustments were made to clearly observe the adventitia. The transverse diameter (DTR) and anteroposterior diameter (DAP) of the vessel were obtained simultaneously. To further reduce the risk of measurement error, the corrected diameter (DC) was calculated using the following formula: π(DAP/2) × (DTR/2) = π(DC/2)2 (11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The measurement of DRA diameter in children by ultrasound. (A) the site of ultrasound measure. Circle: distal radial artery; Triangle: proximal radial artery; Star: ulnar artery. (B) the cross-sectional image of the distal radial artery in anatomic snuffbox. Star, scaphoid; DTR, transverse diameter; DAP, anteroposterior diameter.

The diameters of the PRA and ulnar artery (UA) were measured at the site 2 cm proximal to the wrist striation. The diameter of the DRA was measured at the AS. The depth of the DRA defined as the distance from the skin to the upper edge of the DRA. All diameters were measured three times by a single operator (Tao Chen), and the average value was taken. Additionally, 20 samples were measured simultaneously by two operators (Tao Chen and Yidong Zhao) to assess intra-observer agreement.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 26.0 statistical software. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and comparisons performed using the χ2 test. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, with comparisons conducted using two independent sample t-tests or one-way analysis of variance. The trend of the increase in DRA diameter with age was evaluated using the P for trend test. To analysis the proportions of DRA diameter >2.0 mm and >1.5 mm in different weight groups, the patients were divided into ten subgroups according to the declines of weight. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyse the correlation between the DRA and other factors. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was used to analyze the predictive value of patients’ factors for DRA diameter >2.0 mm. Multiple comparisons were corrected by the Bonferroni method. Inter- and intraobserver agreement was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficients. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

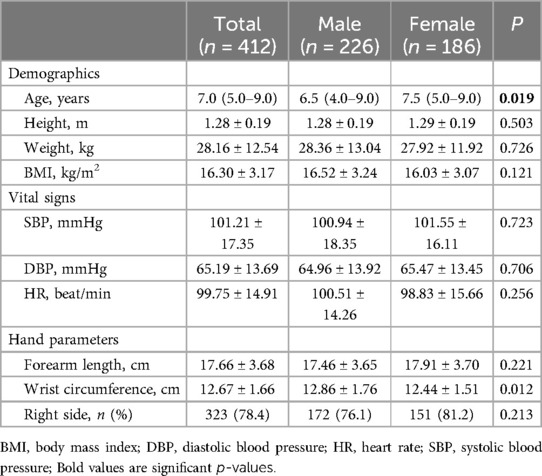

A total of 412 children aged 3–12 years were included in the study. The characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics, vital signs, or hand parameters between the male and female groups, except for wrist circumference. The proportion of males was 54.85% (226/412), and the mean BMI was 16.3 ± 3.17 kg/m2. Ultrasound data for 78.4% (323/412) of the individuals were obtained via the right hand. The depth of the DRA in males was significantly greater than in females (4.04 ± 1.06 mm vs. 3.91 ± 0.91 mm, p < 0.05).

DRA diameter in children

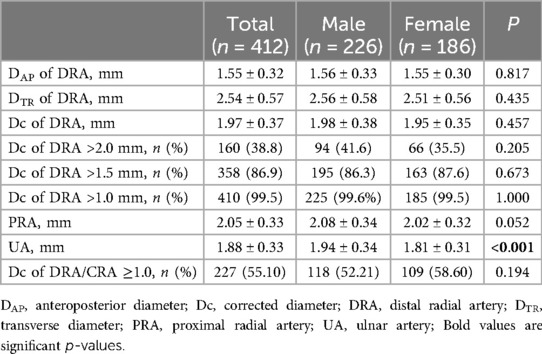

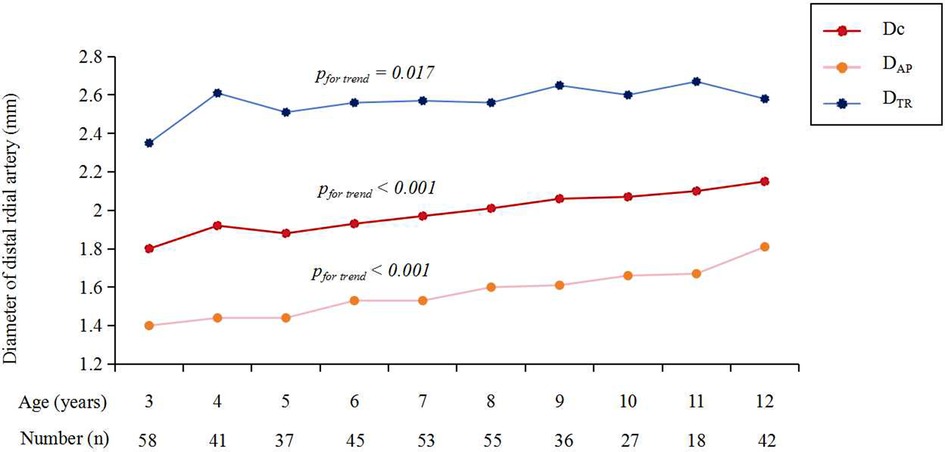

The Dc of DRA in the AS was 1.97 ± 0.37 mm overall, with no significant difference between males (1.98 ± 0.38 mm) and females (1.95 ± 0.35 mm) (p = 0.457) (Table 2). The DAP, DTR, DC of DRA increased significantly with age (Figure 2). The increasing trend of DRA diameter was also significant in both male and female subgroups.

Figure 2. The diameter of DRA in different age groups. DRA, distal radial artery; DAP, anteroposterior diameter; Dc, corrected diameter; DTR, transverse diameter.

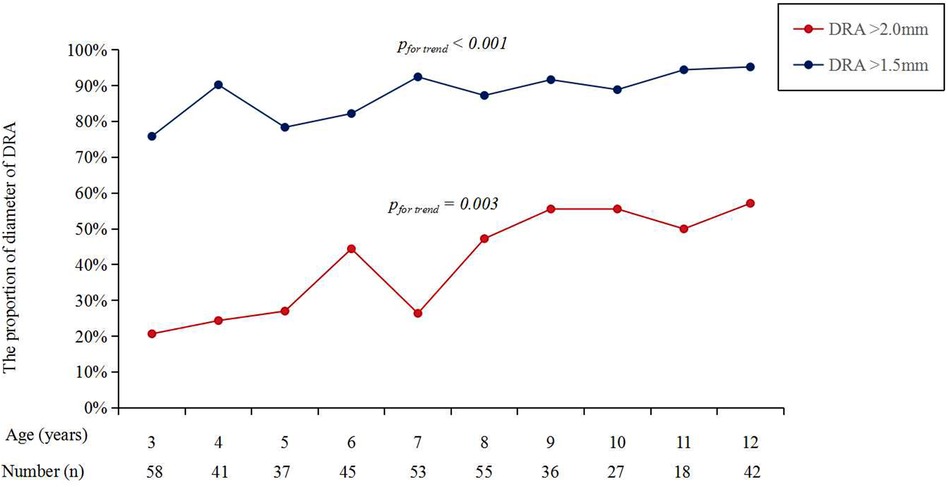

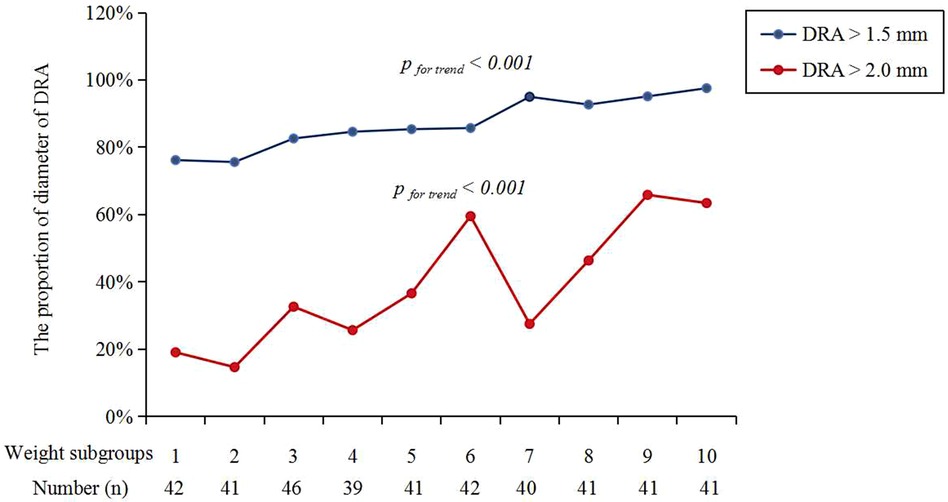

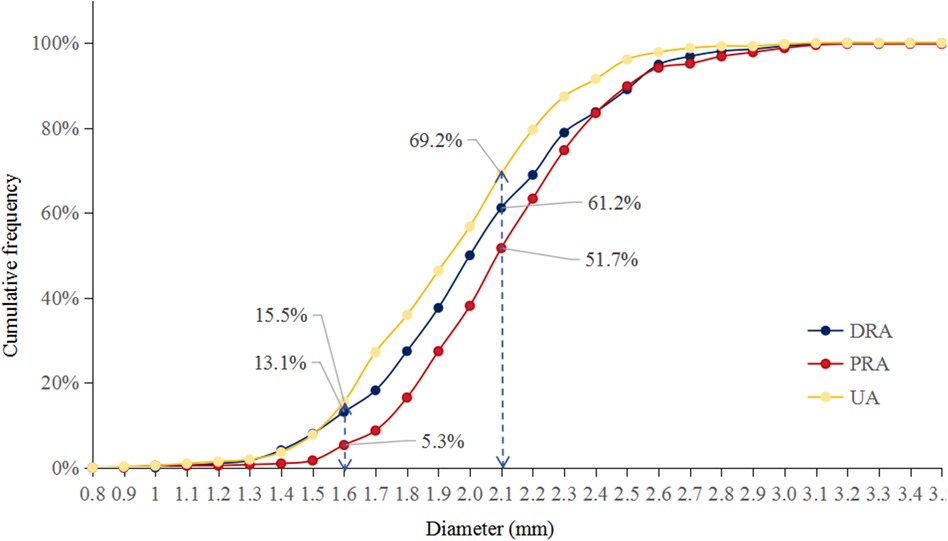

Figure 3 shows the cumulative frequency of DRA diameter. Overall, the proportions of patients with a DRA diameter greater than 2.0 mm and 1.5 mm were 38.83% and 86.89%, respectively (Table 2). The proportions of patients with DRA diameters >2.0 mm and >1.5 mm according to age are shown in Figure 4, demonstrating a significant gradual increase with age (p < 0.01). Additionally, the proportions of patients with DRA diameters >2.0 mm and >1.5 mm according to weight are shown in Figure 5, demonstrating a significant gradual increase with weight (p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Cumulative frequency. The proportions of vessel diameter >2.0 mm was 38.8% in DRA, 48.3% in PRA, and 30.8% in UA, respectively. The proportions of vessel diameter >1.5 mm was 86.9% in DRA, 94.7% in PRA, and 84.5% in UA, respectively; DRA, distal radial artery; PRA, proximal radial artery; UA, ulnar artery.

The DRA diameter was significantly smaller than the PRA diameter (1.97 ± 0.37 mm vs. 2.05 ± 0.33 mm, p < 0.001) but larger than the UA diameter (1.97 ± 0.37 mm vs. 1.88 ± 0.33 mm, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The percentages of individuals with a DRA/PRA ratio ≥1.0 were 55.10% overall, 52.12% in males, and 58.60% in females (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with a DRA/PRA ratio ≥1.0 between male and female groups (p = 0.194).

Correlations between the DRA diameter and other factors

The DRA diameter was significantly positively associated with age (r = 0.275, p < 0.01), height (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), weight (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), BMI (r = 0.241, p < 0.01), wrist circumference (r = 0.354, p < 0.01), PRA diameter (r = 0.521, p < 0.01), and UA diameter (r = 0.272, p < 0.01).

Predictive factors for the DRA diameter >2.0 mm

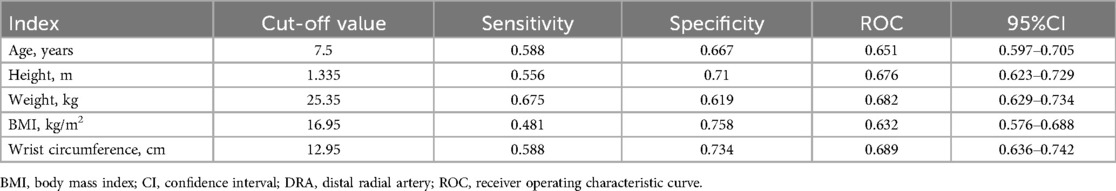

ROC was used to analyze the predictive value of patients’ factors for DRA diameter >2.0 mm (Table 3). The AUC of age, height, weight, BMI and wrist circumference were 0.651, 0.676, 0.682, 0.632, and 0.689, respectively. The cut-off values were 7.5 years old, 1.335 m, 25.35 kg, 16.95 kg/m2, and 12.95 cm, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first large sample-size study to measure the DRA diameter in children using high-frequency ultrasound. The study revealed that the Dc of the DRA was 1.97 ± 0.37 mm and that the DRA diameter gradually increased with age, height, weight, BMI, wrist circumference, PRA diameter, and UA diameter in children.

The majority of pediatric cardiocerebrovascular interventions can be successfully performed using femoral artery access. In recent years, PRA, carotid, and axillary arterial access have emerged as attractive alternatives to femoral access and have been reported as safe and effective for cardiocerebrovascular intervention (12–14). The 4 Fr and/or 5 Fr sheath can be safely and effectively used for cardiovascular diagnosis and intervention via PRA access in children with diameters of 1.96 mm and 2.29 mm respectively (10). In children, the mean PRA diameter was reported to be 1.39 mm in females and 1.57 mm in males, correlated with sex, age, and body weight (15). Alehaideb A et al. reported that the mean corrected PRA diameter was 1.86 mm in 134 children younger than 18 years. However, studies have shown that cardiovascular intervention via PRA access may cause injury to the forearm radial artery in adults, increase the thickness of the vessel intima, and raise the incidence of RAO, potentially limiting the reuse of the radial artery (16).

The DRA access has been proven to have significantly fewer access-related complications, including forearm RAO, due to its unique anatomical structure (7). Moreover, the DRA has safely and effectively used as an alternative access for invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring under surgical anesthesia and in the ICU due to its good blood pressure consistency with the PRA (17, 18). In adults, the DRA diameter was reported to be about 2.0 mm, smaller than the PRA diameter, with a DRA/PRA ratio of approximately 0.8 (19–22). However, the DRA is not always smaller than the PRA (19). Predictive factors for DRA diameter vary; for instance, in Koreans, female sex and a low BMI were reported as independent predictors of a DRA diameter <2.3 mm (22), while in Japanese patients, no association was found between patient characteristics and vessel diameter (20).

Few studies have evaluated the DRA diameter and explored the feasibility of interventional diagnosis and treatment via DRA access in children (10). Theoretically, DRA access may provide better protection for the forearm radial artery in children compared to PRA access. Although DRA puncture in children is more challenging due to the small vessel size. methods such as the use of thin-walled sheaths, vasodilators, and ultrasound-guided puncture can significantly increase the success rate of small vessel punctures and reduce puncture-related complications (23–25). In a small sample size study, Srinivasan VM et al. reported that the DRA diameter was 2.09 ± 0.54 mm, similar to the PRA diameter (10). In our study, the corrected DRA diameter in the AS was 1.97 ± 0.37 mm and gradually increased with age. It was significantly smaller than the PRA and larger than the UA. More than 50% of children had a DRA/PRA ratio ≥1.0, significantly higher than in adults (19). This discrepancy may be due to developmental imbalances in children's vessels and superficial location of the DRA in the AS. Despite using appropriate methods to relieve probe pressure during examination, the corrected diameter may not reflect the true lumen size. Compared to adults, children have fewer underlying diseases, which might affect vessel size differently. In this study, the DRA diameter was significantly positively associated with age, height, weight, BMI, wrist circumference, PRA diameter, and UA diameter.

Limitations

First, the children in the study were not consecutively enrolled and were from a single hospital, which may have led to the selection bias. Second, although the sample size was relatively large, the number of patients per age group was small. Previous studies have shown that the increase in the diameter of the PRA plateaus after 12 years of age (11). In this study, the diameter of the DRA gradually increased with age until 12 years of age; however, we cannot conclude whether it has reached a plateau. Third, the diameter of the DRA was measured from adventitia to adventitia, and corrected using a formula, which does not reflect the true inner diameter of the DRA. Fourth, there was a lack of comparison between the two sides. Fifth, the children in this study were from urban areas in Changzhou, Jiangsu, with relatively higher economic status compared to children from other regions. Differences in growth and development among children might affect the size of the DRA.

Conclusion

The diameter of the DRA in children increases with age, making catheterization via the DRA access theoretically feasible. Preoperative evaluation of the vessel diameter and intraoperative ultrasound-guided intervention are recommended for pediatric catheterization via DRA access.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Changzhou Second People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Ethics Committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Due to the retrospective study design, the patients were not required to sign the informed consent.

Author contributions

YZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LY: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. YW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. HD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. GC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This study was supported by grants from the Applied Basic Research Programs of Science, Technology Department Of Changzhou City (CJ20230067 to ZH), The Changzhou High Level Medical Talents Training Project (2022CZBJ102 to GC) and Changzhou Health Commission Youth Talent Science and Technology Project (QN202232 to LY).

Acknowledgments

We thank all our colleagues at the Department of Pediatric, the Second People's Hospital of Changzhou, Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AS, anatomic snuffbox; DRA, distal radial artery; PRA, proximal radial artery; RAO, radial artery occlusion; UA, ulnar artery.

References

1. Irving C, Zaman A, Kirk R. Transradial coronary angiography in children and adolescents. Pediatr Cardiol. (2009) 30(8):1089–93. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9502-6

2. Takeshita J, Nakayama Y, Tachibana K, Nakajima Y, Shime N. Ultrasound-guided short-axis out-of-plane approach with or without dynamic needle tip positioning for arterial line insertion in children: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. (2023) 42(3):101206. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101206

3. Tsigkas G, Papanikolaou A, Apostolos A, Kramvis A, Timpilis F, Latta A, et al. Preventing and managing radial artery occlusion following transradial procedures: strategies and considerations. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2023) 10:283. doi: 10.3390/jcdd10070283

4. Mounsey CA, Mawhinney JA, Werner RS, Taggart DP. Does previous transradial catheterization preclude use of the radial artery as a conduit in coronary artery bypass surgery? Circulation. (2016) 134:681–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022992

5. Ferrante G, Condello F, Rao SV, Maurina M, Jolly S, Stefanini GG, et al. Distal vs conventional radial access for coronary angiography and/or intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15:2297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.09.006

6. Chen T, Li L, Li F, Lu W, Shi G, Li W, et al. Comparison of long-term radial artery occlusion via distal vs. Conventional transradial access (CONDITION): a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. (2024) 22:62. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03281-7

7. Cai G, Huang H, Li F, Shi G, Yu X, Yu L. Distal transradial access: a review of the feasibility and safety in cardiovascular angiography and intervention. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2020) 20:356. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01625-8

8. Chadow D, Soletti GJ, Gaudino M. Never again. Once used for cardiac catherization the radial artery cannot be used for CABG. J Card Surg. (2021) 36:4799–800. doi: 10.1111/jocs.16045

9. Dharma S, Kamarullah W, Nurcahyani MR, Josephine CM. Association of 5F and 6F radial sheath with the incidence of radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Coron Artery Dis. (2022) 31:e94–6. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000001097

10. Srinivasan VM, Hadley CC, Prablek M, LoPresti M, Chen SH, Peterson EC, et al. Feasibility and safety of transradial access for pediatric neurointerventions. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:893–6. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-015835

11. Alehaideb A, Ha W, Bickford S, Dmytriw AA, Bhatia K, Amirabadi A, et al. Can children be considered for transradial interventions?: prospective study of sonographic radial artery diameters. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13:e009251. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.009251

12. Raphael CK, El Hage Chehade NA, Khabsa J, Akl EA, Aouad-Maroun M, Kaddoum R. Ultrasound-guided arterial cannulation in the paediatric population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2023) 3:CD011364. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011364.pub3

13. Haddad RN, Karmustaji F, Alloush R, Al Soufi M, Kasem M. Systematic approach to obtain axillary arterial access for pediatric heart catheterizations. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1332152. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1332152

14. Yamani N, Ali SH, Sadiq M, Ahmed AB, Bhojwani KD, Lohana VP, et al. Trans-femoral versus trans-carotid access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Sci OA. (2024) 10:FSO930. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2023-0101

15. Babuccu O, Ozdemir H, Hosnuter M, Kargi E, Söğüt A, Ayoglu FN. Cross-sectional internal diameters of radial, thoracodorsal, and dorsalis pedis arteries in children: relationship to subject sex, age, and body size. J Reconstr Microsurg. (2006) 22:49–52. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-931907

16. Rashid M, Kwok CS, Pancholy S, Chugh S, Kedev SA, Bernat I, et al. Radial artery occlusion after transradial interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. (2016) 5:e002686. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002686

17. Xiong J, Xu M, Hui K, Zhou J, Zhang J, Duan M, et al. Agreement between distal and forearm radial arterial pressures in patients undergoing prone spinal surgery: a prospective, self-controlled, observational study. J Int Med Res. (2023) 51:3000605231188285. doi: 10.1177/03000605231188285

18. Oi M, Maruhashi T, Kurihara Y, Asari Y. Evaluation of a new insertion site for arterial pressure line in intensive care unit management: a prospective study. J Clin Monit Comput. (2023) 37:867–72. doi: 10.1007/s10877-022-00957-4

19. Naito T, Sawaoka T, Sasaki K, Iida K, Sakuraba S, Yokohama K, et al. Evaluation of the diameter of the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuff box using ultrasound in Japanese patients. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. (2019) 34:312–6. doi: 10.1007/s12928-018-00567-5

20. Norimatsu K, Kusumoto T, Yoshimoto K, Tsukamoto M, Kuwano T, Nishikawa H, et al. Importance of measurement of the diameter of the distal radial artery in a distal radial approach from the anatomical snuffbox before coronary catheterization. Heart Vessels. (2019) 34:1615–20. doi: 10.1007/s00380-019-01404-2

21. Lee JW, Son JW, Go TH, Kang DR, Lee SJ, Kim SE, et al. Reference diameter and characteristics of the distal radial artery based on ultrasonographic assessment. Korean J Intern Med. (2022) 37:109–18. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2020.685

22. Deora S, Sharma SK, Choudhary R, Kaushik A, Garg PK, Khera PS, et al. Assessment and comparison of distal radial artery diameter in anatomical snuffbox with conventional radial artery before coronary catheterization. Indian Heart J. (2022) 74:322–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2022.06.007

23. Demirkıran A, Aydın C. Methods for increasing distal radial artery diameter. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2023) 27:1875–80. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202303_31553

24. Corder W, Stoller JZ, Fraga MV. A retrospective observational study of real-time ultrasound-guided peripheral arterial cannulation in infants. J Vasc Access. (2023) 2023:11297298231186299. doi: 10.1177/11297298231186299

25. Takeshita J, Nakayama Y, Tachibana K, Nakajima Y, Hamaba H, Shime N. Comparison of radial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries for ultrasound-guided arterial catheterisation with dynamic needle tip positioning in paediatric patients: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. (2023) 131:739–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.07.022

Keywords: cardiac catheterization, children, congenital heart disease, radial artery, unusual access

Citation: Zhao Y, Chen T, Yang L, Mao W, Wan Y, Zhang L, Ding H, Cai G and Huang Z (2024) Is catheterization via distal transradial access feasible in children? From vessel diameter perspective. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1428083. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1428083

Received: 5 May 2024; Accepted: 23 July 2024;

Published: 2 August 2024.

Edited by:

Nazmi Narin, Izmir Katip Celebi University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Raymond N. Haddad, Hôpital Universitaire Necker-Enfants Malades, FranceKaan Yildiz, Izmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye

© 2024 Zhao, Chen, Yang, Mao, Wan, Zhang, Ding, Cai and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gaojun Cai, Y2FpZ2FvanVuQHdqcm15eS5jbg==; Zhiying Huang, aHp5OTgyQDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡ORCID:

Gaojun Cai

orcid.org/0000-0003-4250-180X

Zhiying Huang

orcid.org/0000-0002-7075-0777

Yidong Zhao1,†

Yidong Zhao1,† Tao Chen

Tao Chen Zhiying Huang

Zhiying Huang