95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 02 February 2023

Sec. General Cardiovascular Medicine

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1119729

Calcium signaling is required in bodily functions essential for survival, such as muscle contractions and neuronal communications. Of note, the voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) expressed on muscle and neuronal cells, as well as some endocrine cells, are transmembrane protein complexes that allow for the selective entry of calcium ions into the cells. The α1 subunit constitutes the main pore-forming subunit that opens in response to membrane depolarization, and its biophysical functions are regulated by various auxiliary subunits–β, α2δ, and γ subunits. Within the cardiovascular system, the γ-subunit is not expressed and is therefore not discussed in this review. Because the α1 subunit is the pore-forming subunit, it is a prominent druggable target and the focus of many studies investigating potential therapeutic interventions for cardiovascular diseases. While this may be true, it should be noted that the direct inhibition of the α1 subunit may result in limited long-term cardiovascular benefits coupled with undesirable side effects, and that its expression and biophysical properties may depend largely on its auxiliary subunits. Indeed, the α2δ subunit has been reported to be essential for the membrane trafficking and expression of the α1 subunit. Furthermore, the β subunit not only prevents proteasomal degradation of the α1 subunit, but also directly modulates the biophysical properties of the α1 subunit, such as its voltage-dependent activities and open probabilities. More importantly, various isoforms of the β subunit have been found to differentially modulate the α1 subunit, and post-translational modifications of the β subunits further add to this complexity. These data suggest the possibility of the β subunit as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases. However, emerging studies have reported the presence of cardiomyocyte membrane α1 subunit trafficking and expression in a β subunit-independent manner, which would undermine the efficacy of β subunit-targeting drugs. Nevertheless, a better understanding of the auxiliary β subunit would provide a more holistic approach when targeting the calcium channel complexes in treating cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, this review focuses on the post-translational modifications of the β subunit, as well as its role as an auxiliary subunit in modulating the calcium channel complexes.

Calcium is one of the most important elements in organism, participating various physiological processes, such as heartbeat, muscle contraction, and neuronal communication (1,2). Ca2+ enter into the nerve, muscle, and some endocrine cells mainly through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs). Based on the membrane voltage required for activation, 10 subtypes of VGCCs were subsequently classified into high-voltage activated (HVA) and low-VA (LVA) calcium channels (3). Further studies classified Ca2+ currents into L- (Long-lasting), N-(Neural), P(Purkinje)/ Q-, R- (Residual), and T-(Transient) type currents, which exhibit distinct biophysical and pharmacological properties (4).

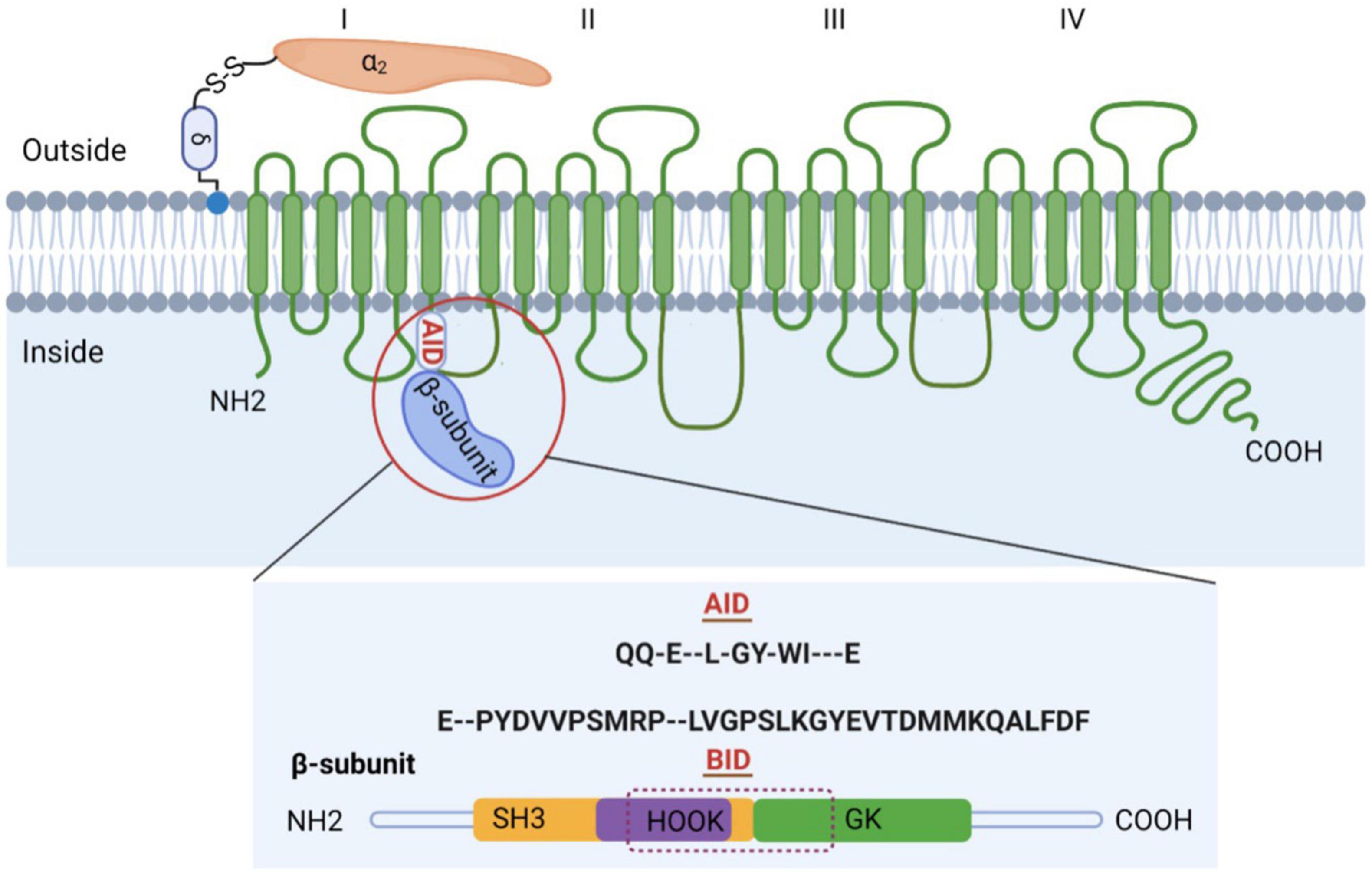

The purified channel complex is composed of the pore-forming subunit α1 (175 kDa) and two auxiliary subunits: α2δ (about 160 kDa), β (54 kDa) (Figure 1) (5). The α1 subunit (Cavα1) is the principal component of VGCCs and is responsible for their unique biophysical and pharmacological properties. However, proper trafficking and functions of L-, N-, P/ Q-, and R-type channels require the auxiliary subunits. In particular, β subunit is indispensable for HVA CaV1 and CaV2 Ca2+ channels. β subunit acts in many different aspects by enhancing Ca2+ channel currents through prevention of proteasomal degradation (6), changing the voltage dependence and kinetics of activation and inactivation, and modulating Cav1 and Cav2 channels by protein kinases or G protein (7).

Figure 1. Subunit composition of high voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). Schematic representation of the predicted transmembrane topology of VGCCs subunits. The complex is composed of the pore-forming subunit α1 (175 kDa) and two auxiliary subunits: α2δ and β. The AID, marked in red, is located on the I–II loop. β subunit is comprised of GK domain, Src homology 3 (SH3), HOOK region, NH2 terminus, and carboxyl terminus, with BID spanning across SH3-HOOK-GK motif. Both AID and BID have a conserved consensus motif, that is, QQ-E–L-GY-WI—E (AID) and E–PYDVVPSMRP–LVGPSLKGYEVTDMMKQALFDF (BID) (36).

β subunit has four subfamilies (β1–β4). β1 subunit is mainly expressed in brain, heart, skeletal muscle, spleen, T-cells (Table 1) (4). The β1a isoform, however, is exclusively expressed in skeletal muscle where it partners with skeletal muscle Cav1.1, and is irreplaceable for excitation-contraction coupling (7). β2 subunit is found in brain, heart, lung, nerve, nerve endings at the neuro-muscular junction, T-cells, osteoblasts (Table 1) (4). It is also the predominant β subunit in the heart, especially β2b (8). β2 subunit knockout mice die prenatally at embryonic day 10.5 due to lack of cardiac contractions (9, 10), indicating the significant role of β2b subunit in cardiovascular human diseases. More importantly, Antzelevitch et al. (11) pointed out that S481L mutation in the C-terminus of β2b subunit contributed to a type of sudden death syndrome characterized by a short-QT interval and an elevated ST-segment. Cordeiro et al. (12) further found that T11l mutation in the β2b N-terminus led to accelerated inactivation of cardiac L-type channels and was linked to the Brugada syndrome.

β3 mostly expressed in brain, but also in heart, aorta and smooth muscle, regulating pain, memory, emotion, and even blood pressure (Table 1) (4). β3 subunit knockout mice showed reduced perception of inflammatory pain but not mechanically or thermally induced pain, which is probably due to reduced N-type calcium channel expression in dorsal root ganglia (13). Behaviorally, β3-null mice exhibit impaired working memory, lowered anxiety and increased aggression and nighttime activity (14,15). Moreover, a high-salt diet induced abnormally elevated blood pressure, reduced plasma catecholamine levels (16) and hypertrophic heart and aortic smooth muscle in β3 subunit knockout mice (17). These results point to a compromised sympathetic control in β3 subunit knockout mice, likely due to reduced N- and L-type channel activity (18). A recent study comparing epileptic patients with non-epileptic individuals identified three mutations in β3 subunit that were present only in patients (19), which further associated β3 subunit with brain disorders.

β4 subunit expressed in cerebellum, kidney, and skeletal muscle, but not in the cardiac muscle of adults (Table 1) (4). β4 subunit knockout mice, which was generated by an insertion that causes exon skipping and a premature stop codon in the gene for β4 subunit, exhibited ataxia, seizures, absence epilepsy, and paroxysmal dyskinesia (20). This could be caused by a 50% up-regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in thalamic neurons (21). Recent studies have, respectively, indicated that lethargic mice also show impairment of parallel fiber volley and Purkinje cell firing in cerebellum (22) and a modified electro-oculogram (23). More importantly, three mutations in the gene encoding of β4, that is, R468Q, R482X, and C104F, were identified in patients with seizures and epilepsy (24, 25).

Overall, β subunit is crucial not only in the protein expression level of calcium channels, but also in the channel activation and inactivation. Various heterologous expression systems with all four subfamilies of β subunit and all CaV1 and CaV2 subunits have shown that β subunit can function as a chaperone to dramatically increase the surface expression of CaV1 and CaV2 channels (26). Moreover, β1 and β2 knockout mice have severely reduced Ca2+ currents in heart, while overexpression of β subunit using adenoviruses can increase Ca2+ channel current density in native cardiac cells (27,28). β subunit can also prevent proteasomal degradation of calcium channels induced by increased ubiquitination via K48-linked ubiquitin chain, which was caused by its association with ret finger protein 2 (RFP2), an ER-localized RING finger E3 ligase (6,29). In addition, studies on β subunit knockout mice have shown that β subunit can shift the voltage dependence of activation to more hyperpolarized voltages by 10–15 mV (10). This shift is also visible at the single-channel level, as indicated by Luvisetto et al. (30). Furthermore, β subunit also modulates voltage-dependent inactivation, which reduces the amount of Ca2+ entering the cell following depolarization and decreases the number of channels responsible to subsequent depolarizations, causing a shift to more depolarized voltages by 10–20 mV (8, 31).

Previous studies have revealed that β subunit is comprised of five distinct regions, namely, guanylate kinase (GK) domain, Src homology 3 (SH3), HOOK region, NH2 terminus, and β-interaction domain (BID), based on amino acid sequence alignment, biochemical and functional studies, and molecular modeling (8,32). The GK domain, SH3 domain, and HOOK region constitute the core of β subunit. GKs can catalyze the reversible phosphoryl transfer from ATP to guanosine monophosphate (GMP) to produce ADP and GDP. SH3 domain contains a well-preserved PxxP motif-binding site and thus has the potential to bind PxxP motif-containing proteins. Therefore, the GK domain and SH3 domain are protein interaction modules in β subunit, engaging in protein-protein interactions (33).

With the development of crystallography, the crystal structure of the β subunit core was reported in 2004, verifying that β core indeed contains an SH3 domain and a GK domain, linked by HOOK region (34–36). Crystal structures of yeast GKs show that these enzymes have a catalytic site harboring the GMP- and ATP-binding pockets (37), which further explains its catalytic ability. The SH3 domain has a similar folding as canonical SH3 domains do. However, its last two β sheets are non-continuous, separated by the HOOK region (34–36). The HOOK region is variable in length and amino acid sequence among the β subfamilies. In the crystal structures, a large portion of the HOOK is unresolved due to poor electron density, indicating that it has a high degree of flexibility (34–36). A recent study also revealed the NMR structure of the NH2 terminus, which consists of two α-helices and two antiparallel β sheets (38). One of the two α-helices in the NMR structure is equivalent to the very first α-helix in the β core structures. Superposition of this helix in the two structures reveals that the NH2 terminus is oriented away from the core.

Crystal structure of the β core not only verified the component of β core, but also showed that SH3 and GK domains interact intramolecularly (34–36). The interaction is strong enough such that hemi-β fragments containing the NT-SH3βstrand 1–4-HOOK module and the SH3βstrand 5-GK-CT module can associate biochemically in vitro and reconstitute the functionality of full-length β subunits when they are coexpressed in cells (39–41). The strong intramolecular SH3-GK interaction comes from the last β sheet of β-SH3 (SH3βstrand 5), which is directly connected to the GK domain, and interacts extensively with both the GK domain and the rest of the SH3 domain, strengthening the otherwise weak interactions at the SH3-GK interface (42). Apart from the interaction between SH3 and GK domains within β subunit, Pragnell et al. (32) also found that β subunit binds to α-interaction domain (AID) domain within α1 subunit, a high-affinity site located in the cytoplasmic loop connecting the first two homologous repeats of α1 subunit. AID is comprised of 18 residues, with a conserved consensus motif (QQxExxLxGYxxWIxxxE) in all CaV1 and CaV2 channels. The AID binds to all four β subunits through the BID, a 31-amino acid segment of β subunit (43). Single mutations in either AID or BID can greatly weaken the α1–β interaction, as indicated by in vitro binding experiments (44).

The calcium channel β subunits are known to be regulated by various post-translational modifications, namely, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Pioneering studies from the 1980s revealed the rapid phosphorylation of the RRPTP motif of the β1a subunit by protein kinase A (PKA) and cAMP-dependent kinases within skeletal muscles (45). Notably, in cardiomyocytes, cAMP-dependent phosphorylation was later identified to be the primary phosphorylation of the β subunits (46). As such, phosphorylation of the β subunits was thought to be a signal transduction pathway for the up-regulation of L-type calcium channels.

β2a, the main β subunit within the cardiac milieu, was empirically reported to be phosphorylated by PKA on three serine residues–Ser459, Ser 478, and Ser479 of the C-terminus (47). Interestingly, these phosphorylation sites were not conserved within the other β subunit isoforms. This therefore raises the question for whether phosphorylation of the β2a subunit is indeed important for its function. However, an overexpression paradigm in cardiomyocytes revealed no significant modulation of the CaV1.2 channels by the β2a subunit (48). In that study, it was observed that a phosphorylation-deficient β2a subunit mutant equally up-regulated the functions of CaV1.2 channels in heart cells. This result suggests that the phosphorylation of the β2a subunits in heart cells may be involved in the facilitation of other signaling pathways rather than modulating CaV1.2 channel functions. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the presence of the β2a subunit is still important for increasing the open probability (Po) of the α1 subunit even when compared to the other β subunit isoforms (8).

In a more recent study, the use of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) elucidated the in vivo phosphorylation of two residues of the β1a–Ser193 and Thr205 (49). Both residues are located within the HOOK domain of the β1a subunit, and, interestingly, are conserved across the various β subunit isoforms. Although in silico prediction models suggested the possible phosphorylation of Ser193 of the β1a by casein kinase II, in vitro experiments proved otherwise, however, on the other hand, Thr205 of the β1a was observed to be phosphorylated by PKA. Functionally, electrophysiological whole-cell patch clamp techniques revealed the phosphor-modulatory functions of the two residues. Through the site-directed substitutions of the conserved phosphorylated residues, S152E phosphomimetic of the conserved Ser residue within β2b showed a significantly decrease in the peak current density of CaV1.2 channels. Moreover, the voltage-dependent activation and inactivation of CaV1.2 channels were right-shifted toward more positive potentials. As expected, S152A phospho inhibitory substitution showed opposing effects. Conversely, it is interesting to note that neither the phosphomimetic nor phospho inhibitory substitution of T164D and T164A of β2b, respectively, revealed no observable differences in either CaV1.2 peak currents or its voltage-dependent activities. However, it was noted that calcium-dependent inactivation of β2bT164D was significantly increased but not in β2aT164D, thus suggesting a subunit-specific effect. It may be possible that the differential effect arose from other modifications of the β2a subunit, such as palmitoylation. Nevertheless, it is clear that phosphorylation of either the conserved Ser or Thr residues within the HOOK domain of β subunits allowed for the modulation of the α1 channel properties.

Even more recently, a β subunit-dependent modulation of CaV1.2 channels by Rad protein was reported (50–52). Rad is a member of the Ras/GTPase superfamily and was characterized for its unique GTPase-activating protein (GAP)-like activity (53). It was reported that substitution of specific residues into alanine in Rad (Arg208 and Leu235) or β2a subunit (Asp244, Asp320, and Asp322) abolished the interaction between these two proteins (54). Furthermore, these mutations also attenuated the hyperpolarizing shift in the current-voltage curve of CaV1.2 channels, thereby leading the authors to conclude that the interaction between Rad and β2a is necessary for the cAMP-PKA regulation of CaV1.2 channels. Moreover, using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), the authors further showed the robust interaction between Rad and β2a, which complements the reports from earlier studies (50,55). Here, the coexpression of only the PKA catalytic subunit with Rad abolished the interaction between Rad and β2a. It was also reported that similar results were observed between phosphorylated Rad and the other β subunit isoforms. Therefore, taken together, these data strongly suggest that the phosphorylation of Rad functions to inhibit its interaction with the β subunits. Further studies showed that Rad-phosphosite-mutant mice (4SA-Rad) displayed weakened adrenergic activation of calcium channels, which thus produced profound physiological effects: reduced heart rate with increased pauses, reduced basal contractility, attenuated of β-adrenergic contractile response, and diminished exercise capacity (52).

In addition to PKA, protein kinase C (PKC) has also been identified to phosphorylate the β subunit (56). Here, proline and serine residues within the BID were phosphorylated, and are located between the SH3 and GK domains (43). Similarly, phosphomimetic substitutions of phosphorylated residues were made and the function of the resultant phosphomimetic β1b subunit mutants were tested. In their study using Xenopus oocyte cells, peak current density of the α1 subunit was observed to be increased by P221R but decreased by S228R when compared to wild-type β1b subunit. Both P221R and S228R decreased voltage-dependent activation of the α1 channels. On the other hand, while S237R did not affect α1 current density, S237R increased voltage-dependent activation of the α1 channels. Biochemical results revealed that P221R and S228R mutants were able to interact with the α1 subunit similar to that of the wild-type β1b subunit. However, S237R completely abolished any interactions with the α1 subunit. Therefore, these results suggest that PKC phosphorylation of residues within the BID serves to regulate specific functions of the β subunit, thereby modulating the α1 channel properties accordingly.

As aforementioned, the β2a subunit, unlike the other β subunit isoforms, is also regulated by palmitoylation, which describes the process of covalent attachment of fatty acid chains to cysteine residues via a thioester linker (57–59). Palmitoylation of the β2a subunit has been reported in various cell lines such as HEK 293 and Sf9 insect cells and was later identified to occur on Cys3 and Cys4 of the N-terminus. Functionally, confocal imaging revealed that palmitoylation of the β2a subunit was important for regulating the localization of the protein toward the plasma membrane (57). In contrast, palmitoylation-deficient β2a subunits remained largely punctate and intracellular. Moreover, through whole-cell patch clamp experiments, it was observed that the ICa,L of CaV1.2 channels was much less per amount of charge movement when co-expressed with a palmitoylation-deficient β2a subunit. Palmitoylated wild-type β2a subunits also slowed inactivation of the channel complex. However, it should still be noted that even in the absence of palmitoylation, the β2a mutant was still able to facilitate CaV1.2 surface membrane trafficking, presumably through preventing CaV1.2 turnover via ERAD (6).

β subunits are also modified by S-nitrosylation, a reversible post-translational modification of proteins whereby cysteines are S-nitrosylated at sulfhydryl groups (60). β subunit S-nitrosylation was reported to be required for nitric oxide-mediated CaV2.2 down-regulation in a subtype-dependent manner as β1 or β3 subunits resulted in stronger reduction in Ca2+ currents compared with β2 or β4 subunits (61). Moreover, Cys346Ala substitution of β3 subunit significantly ablated the inhibitory effect of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), a nitric oxide donor, on CaV2.2 channel function (61). Therefore, while not expressed within the cardiovascular system, N-type calcium channels are important for proper neurological function and S-nitrosylation is currently being investigated for pain treatment, whereby CaV2.2 channels have been reported to be important for the modulation of pain (62). However, the molecular mechanisms by which β subunit S-nitrosylation affects calcium channel function remain to be investigated. In contrast, a recent study on CaV1.2 channel reported that β subunit is not involved in the nitric oxide-mediated down-regulation of CaV1.2 channels (63) as the β subunits-free S-nitrosylated CaV1.2 channels were still able to degraded at lysosome, a novel mechanism underlying nitric oxide-induced vasodilation. It is noteworthy that β3 subunit mutant carrying Cys346Ala substitution could be used in the CaV1.2 study to further confirm the roles of β subunit S-nitrosylation in CaV1.2 down-regulation by nitric oxide.

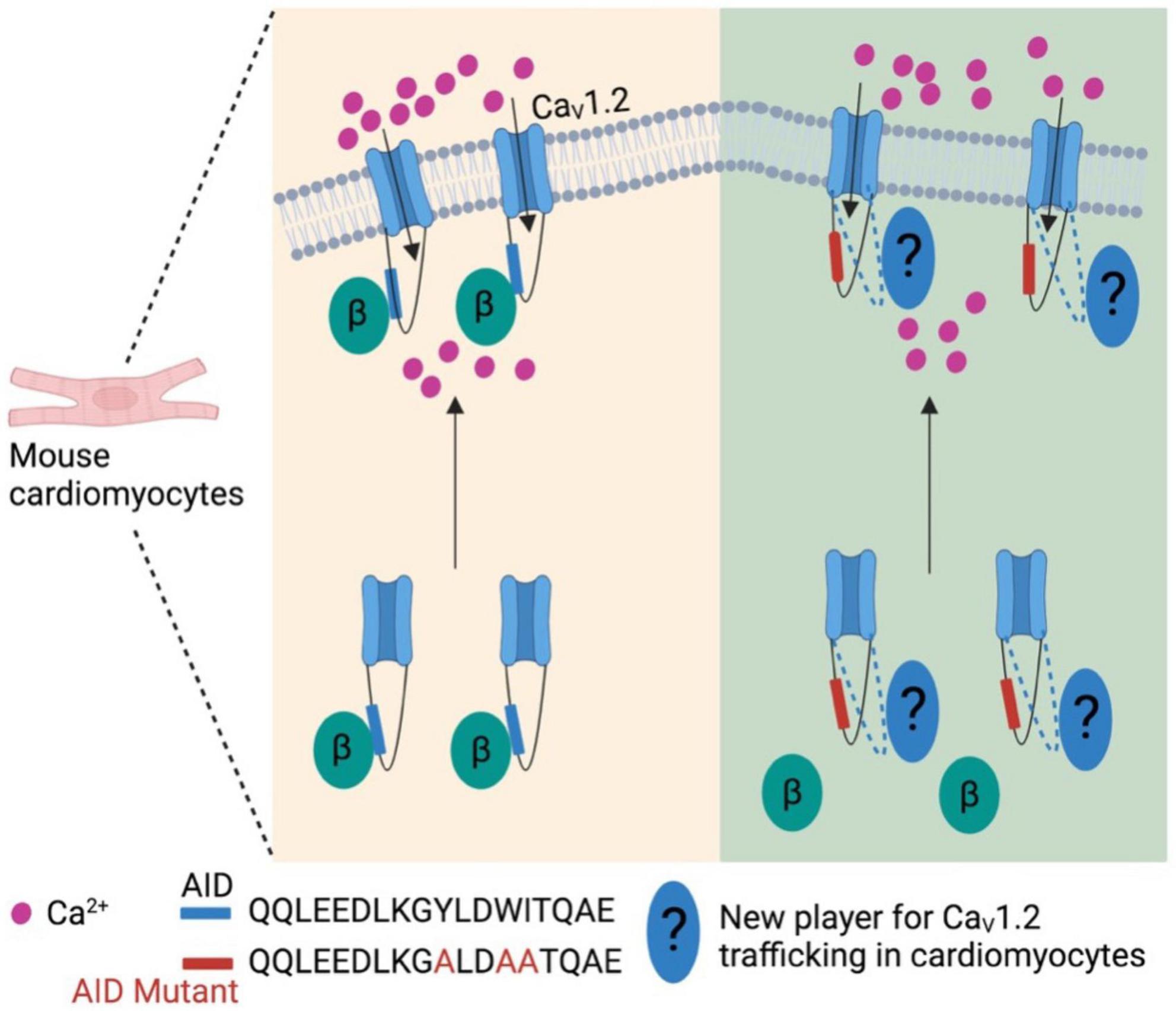

More recently, the generally accepted notion that the β subunit is integral for membrane trafficking of α1 subunits is now brought back into discussion. In cardiomyocytes expressing transgenic α1C mutants that is unable to bind β subunits, α1C subunits were still observed to be trafficked to the sarcolemma in vivo, and was also able to sustain normal excitation-contraction coupling (Figure 2) (64). However, these α1C mutants were not stimulated by agonists of the β-adrenergic pathway, thereby showing significant impairment of β-adrenergic stimulation of contractility. Taken together, these data suggest that while the β subunit is still integral for modulating channel biophysical properties, it may be dispensable in the context of maintaining proper α1 subunit membrane trafficking and basal electrophysiological functions in specific cell types. Nevertheless, further work needs to be done to validate this hypothesis as well as identify potential targets that may replace β subunit for the α1 subunit membrane trafficking in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2. β subunit-less CaV1.2 channels are still trafficked to cell surface in mouse cardiomyocytes. At least in mouse cardiomyocytes β subunit is required for β-adrenergic stimulation on CaV1.2 channels, but not trafficking to plasma membrane. This indicates new player(s) is involved in the trafficking of cardiac CaV1.2 channels.

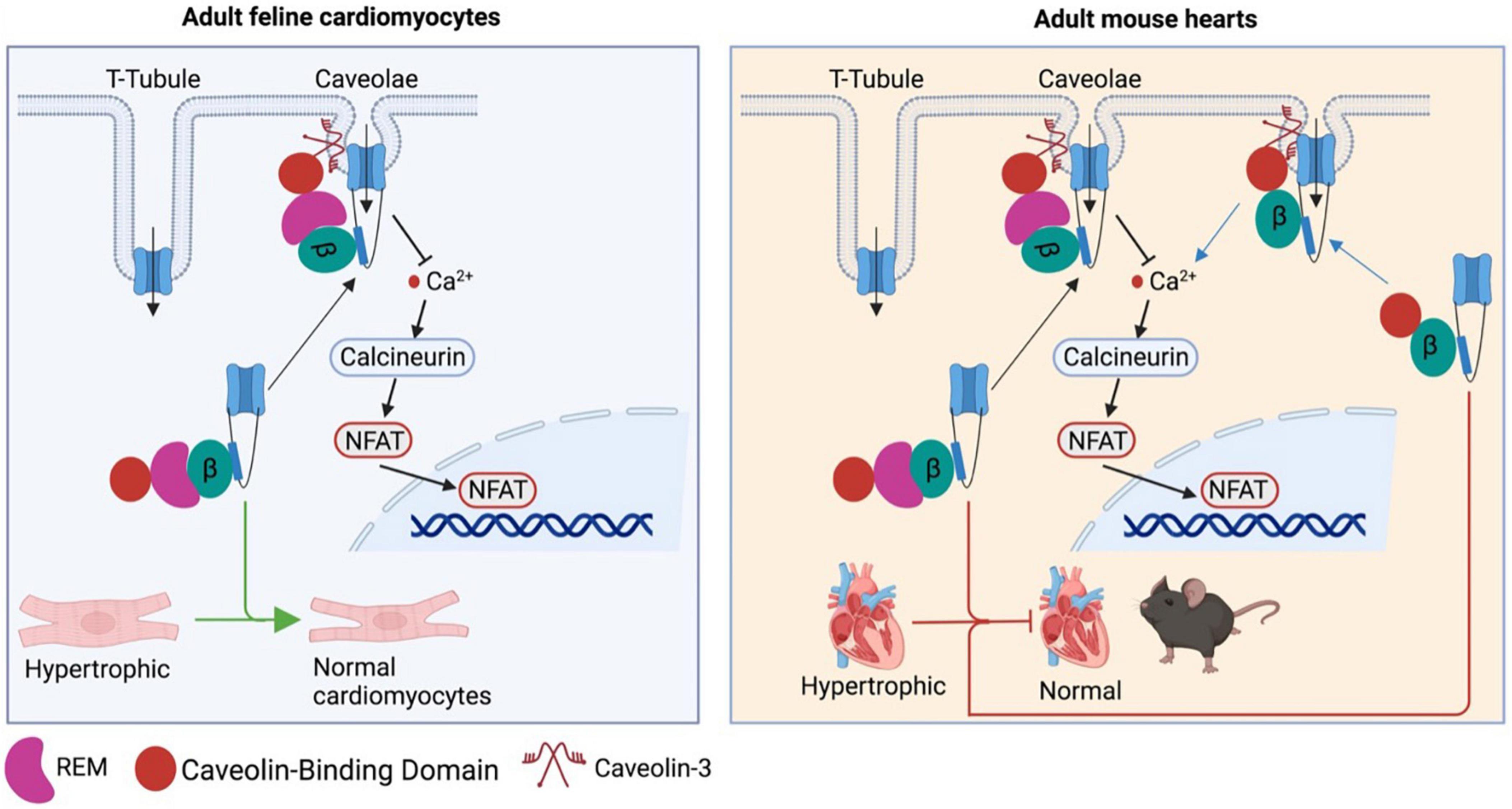

β subunits play important roles in heart and vessels based on their dramatic effects on L-type calcium channels. Cardiac−specific β2a overexpression was reported to induce cardiac hypertrophy with reduced ejection fraction in 6-month-old mice. This could be due to the increased Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2 channels and activated hypertrophic Calcineurin-NFAT3 (nuclear factor of activated T cells) and CaMKII/HADC5 (calcium/calmodulin−dependent protein kinase II/histone deacetylase 5) signaling pathways in β2a-transgenic mice (65). Moreover, another study also reported that the same β2a−transgenic line displayed more severe cardiac hypertrophy under phenylephrine stimulation, while non-phosphorylated mutant β2a-overexpressing mice showed weakened responses to phenylephrine-induced cardiac hypertrophy. This study revealed that CaMKII−mediated phosphorylation of β2a subunits in caveolae is essential for cardiac dysfunction induced by chronic α1-adrenergic stimulation (66). These results are in line with the study that reduction in Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2 channels by short hairpin-mediated knockdown of β2 subunits attenuated the cardiac hypertrophy-induced by pressure overload in mice (67).

Although β subunits are involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy, it remains unclear how β subunits regulate CaV1.2 channel function in cardiomyocytes as CaV1.2 channels were localized at two different microdomains in ventricular and atrial cardiomyocytes: T−tubule and caveolae (68–71). Moreover, there has been a debate on where is the source of hypertrophic Ca2+. A CaV1.2-inhibitory domain of REM, a member of the Rad, Rem, Rem2, and Gem/Kir (RGK) GTPase family that is known to potently inhibit CaV1.2 channel function (72), was fused to a caveolin−binding domain to generate the chimeric protein Caveolin-binding domain (CBD)-REM. CBD-REM was shown to inhibit the NFAT translocation to nucleus in adult feline left ventricular myocytes, although it had no effects on total Ca2+ current density (Figure 3) (73). This work indicates that CaV1.2 channels from caveolae could be the pathway for hypertrophic Ca2+, while T-tubule-resident CaV1.2 channels mainly account for contractile Ca2+. In contrast, with cardiac-specific overexpression of CBD−REM or a caveolae−targeted CaV1.2 activator (CBD−β2a, a mutated β2aC3S/C4S fused C−terminal to CBD) in mice, both transgenic mice with pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy did not display significant changes in cardiac function compared to wild-type mice (Figure 3) although CBD−β2a potentiated the NFAT translocation in feline cardiomyocytes (74).

Figure 3. Controversy over the caveolae-resident CaV1.2 calcium channel as the hypertrophic Ca2+ source. CBD-REM generated by a CaV1.2-inhibitory domain of REM fused to a caveolin–binding domain is able to significantly inhibit the hypertrophic signaling by blocking the NFAT translocation to nucleus in adult feline left ventricular cardiomyocytes, while selective overexpression CBD-REM or CBD-CBD–β2a in cardiac muscles fail to alter cardiac function of mice subjected to pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction.

The mechanisms underlying the differential effects of CBD−β2a in mouse heart and feline ventricular myocyte remain to be investigated. As L-type calcium channels were reported to be redistributed to caveolae from T-tubule in failing human and rat cardiomyocytes, which led to increased open probability of CaV1.2 channels and early afterdepolarization (75), one could expect that the effect of CBD−β2a on caveolae-resident CaV1.2 channels may be weakened by increased CaV1.2 channel numbers in caveolae of failing mouse cardiomyocytes. In addition, it is noteworthy that caveolin-3 was reported to bind to β2c and β2a only, not β2b, β2d, β3, β4 in mouse ventricular myocytes, and a Caveolin-3P104L mutant overexpressed in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes remarkedly reduced the β2c trafficking to cell surface through Caveolin-3 retention in Golgi complex (76). This finding raises a concern that CBD−β2a may not be able to bring sufficient CaV1.2 channels to caveolae in cardiomyocytes. More importantly, as mentioned above in this review β subunit-less CaV1.2 channels are still able to be trafficked to cell surface in mouse ventricular myocytes (64), which indicates that overexpression of CBD−β2a may not produce significant effects on CaV1.2 levels at plasma membrane.

In addition to heart diseases, β subunits also have essential roles in vascular diseases. It has been reported that both total CaV1.2 channel level in aortas and L-type Ca2+ current in isolated aortic smooth muscle cells were reduced in β3–/– mice, although the basal systolic blood pressure remained normal (16, 17, 77). However, compared to wild-type mice, β3–/– mice developed significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure when fed with high salt diet (17) or subcutaneously infused with Angiotensin II for 2 weeks (77). Why global loss of β3 does not induce the phenotype of hypertension? It could be due to the abundant expression of β3 subunits in multiple organs as mentioned in section “1. Introduction.” β3–/– mice have been found to exhibit enhanced performance in several memory tasks through increased N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor (NMDAR) currents and NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (14), suggesting that β3 loss is able to activate NMDAR. Intriguingly, NMDA receptor activation induces renal vasodilation by increasing the epithelial sodium channel-dependent connecting tubule-glomerular feedback responses (78). These results suggest lack of gross phenotype in hypertension in β3–/– mice could be due to the compensatory effects from activation of NMDAR in kidney. A smooth muscle-specific knockout mouse of β3 subunits may more precisely validate the roles of β3 subunit in blood pressure regulation.

Given that β subunits play key roles in regulating the function of L-type calcium channels, the major calcium channels in cardiovascular systems (29, 79), thus β subunits have been considered as targets for developing new therapeutics of cardiovascular diseases.

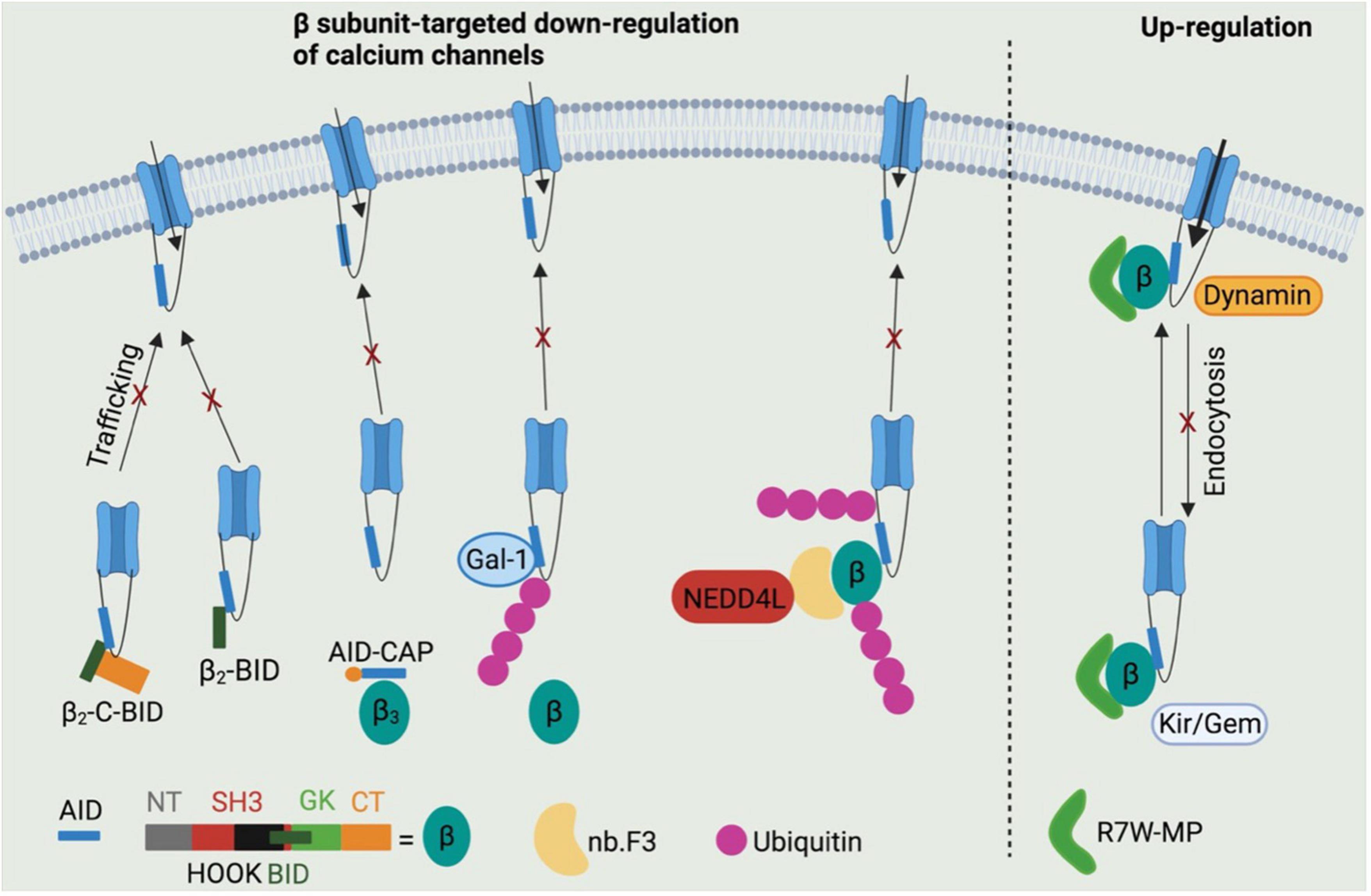

Two truncated N-terminus-less β2 subunit including the BID and C-terminus (β2-C-BID) or BID only (β2-BID) have been reported to bind to CaV1.2 channels intracellularly, while lacking the motifs required to target the CaV1.2 channel complex to cell surface (80). Both β2-C-BID and β2-BID displayed strong dominant-negative effects on L-type Ca2+ current density in HL-1 cells as shown in Figure 4 (80), a cardiac muscle cell line derived from AT-1 mouse atrial cardiomyocyte tumor lineage (81). These β2 subunit decoys represent potential therapeutics to reduce CaV1.2 surface expression in cardiovascular pathologies featured by up-regulation of CaV1.2 channels. However, the ability of β2-C-BID and β2-BID to interfere with the protein interactions between L-type calcium channels and β2 subunits and to reduce total and surface CaV1.2 channels remains to be tested.

Figure 4. Potential β subunits-targeted therapeutic development through modulating calcium channel functions. β2-C-BID and β2-BID, lacking for the channel trafficking-required motifs, occupy the β subunits-binding sites within AID domain, thereby leading to reduced trafficking of channels to cell surface. Stapled AID peptides disrupt the interactions between calcium channels and β3 subunits, but not β2 subunits, which also results in down-regulation of calcium channel function. Galectin-1 is able to displace β subunits from calcium channels by binding to exon 9 C-terminus and thus to inhibit channel function by exposing lysines within I–II loops to ubiquitination. A β subunit-binding nanobody nb.F3 fused with catalytic domain of NEDD4L E3 ligase significantly blocks the calcium channel function by strongly enhancing the ubiquitination level. R7W-MP peptide, which binds to tail-binding domain (TID) domain within the β2 subunit Src homology 3 (SH3) domain, is able to up-regulate calcium channel function via multiple mechanisms, such as preventing channel degradation via ubiquitin-protease system, inhibiting the channel endocytosis by displacing dynamin from β subunits and facilitating the channel trafficking to cell surface by displacing Kir/Gem from β subunits.

In addition to BID domain, α1-ID within I–II loop of L-type calcium channels is also considered a target to regulate the protein interactions between β subunits and calcium channels. An AID peptide with meta-xylyl (m-xylyl) staple incorporated at N-terminal (AID-CAP) was designed to enhanced helical content that bind to β subunits in a native-like manner (82). AID-CAP was shown to significantly reduce the peak Ca2+ current in Xenopus oocytes co-expressing β3 subunits and wild-type CaV1.2 channels, or β2 subunits and mutant CaV1.2Y437A channels carrying a mutation within AID that weakens the β-binding affinity by about 1,000-fold (Figure 4) (83). In contrast, AID-CAP failed to alter the Ca2+ current in Xenopus oocytes expressing β2 subunits and wild-type CaV1.2 channels, suggesting that CaV1.2-β2a protein complexes stably resist kinetic competition by injected AID-CAP peptides. This could be due to the similar binding affinity of wild-type CaV1.2 channels or AID-CAP to β2 subunits (82) or palmitoylation mediated β2a subunit anchoring to the membrane (84). Overall, the stapled AID peptides show strong binding affinity to CaV1.2 channels with negatively regulatory effects in β isoform-selective manner. However, further studies need to conducted to validate their effects of CaV1.2 protein levels and the CaV1.2-β protein interactions by biochemical assays and to test their roles in cardiovascular diseases using multiple rodent models, such as roles in hypertension using spontaneously hypertensive rats.

Regarding the CaV1.2-β protein interactions, Galectin-1, a member of β-galactoside-binding protein family (85), has been identified as a new CaV1.2-binding partner that interact with I–II loop in a splice isoform-specific and CaV1.2 channel-selective manner (86), and has emerged as a novel target for hypertension treatment through disrupting CaV1.2-β protein interaction and promoting the proteasomal degradation of CaV1.2 channels (87). Galectin-1 was reported to bind to residues Asp457 and Glu459 within exon 9*-null I–II loop of CaV1.2 channels, thereby removing β subunits from CaV1.2 channels and masking the endoplasmic reticulum export signals within exon 9 fragment. β subunit displacement further exposed lysines within I–II loop to poly ubiquitination, which increases the proteasomal degradation of CaV1.2 channels (Figure 4) (87). More importantly, the negative regulation on CaV1.2 channels function by Galectin-1 was found to effectively and stably control hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats when Galectin-1 was overexpressed in smooth muscles using adeno-associated virus as a vector (87). It is noteworthy that the CaV1.2-binding sites within Galectin-1, which may help to develop anti-hypertensive Galectin-1-based peptides, have not been identified.

Recently an immunized llama nanobody nb.F3 has been isolated and found to interact with β2b with a high binding affinity (Kd = 13.2 ± 7.2 nM) (88). The nanobody itself has no effects on calcium channel function. Intriguingly, when the C-terminus of nb.F3 was fused to the catalytic Homologous to the E6-AP Carobxyl Terminal (HECT) domain of NEDD4L, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (89), the resulted construct, named CaV-aβlator, completely blocked the Ca2+ current from various high VGCCs overexpressed in HEK 293 cells, and from endogenous calcium channels in guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes, murine dorsal root ganglion neurons and pancreatic β cells (Figure 4) (88). This study proposed a potent genetically encoded general inhibitor for β subunit-binding calcium channels, which, however, remains to be validated in disease models.

In addition to β subunits-targeted negative modulation of calcium channel function, a peptide R7W-MP containing an oligoarginine (R7W) cell-penetrating peptide and a fragment of β2 subunit C-terminal coiled-coil tail was designed to stabilize CaV1.2 channels. Akt-phosphorylated β2 subunit C-terminal tail was reported to bind to the tail-binding domain (TID) within β2 SH3 domain, which induced a structural rearrangement of β2 subunit and thereby stabilized CaV1.2 channels by preventing the proteasomal degradation (90,91). R7W-MP peptide, by targeting TID domain within the β2 subunit SH3 domain, was able to prevent Dynamin from binding to β2 subunit SH3 domain, thereby protecting CaV1.2 channels against endocytosis (91,92). Moreover, R7W-MP peptide also facilitated CaV1.2 chaperoning to the plasma membrane by preventing the interaction between β2 subunits and Kir/Gem (Figure 4) (91), a member of the RGK small GTP-binding protein family reported to decrease the level of L-type calcium channels at cell surface (93, 94). More importantly, R7W-MP restores cardiac function in a diabetic cardiomyopathy mouse model through increasing CaV1.2 current density.

β subunits have been widely studied in various cardiovascular disease conditions and plays important roles in cardiac hypertrophy, diabetic cardiomyopathy, and hypertension, although some controversies remain. More strategies modulating high VGCCs have been developed by selectively targeting β subunit itself or the protein interactions between calcium channels and β subunits. Compared to calcium channel blockers to completely ablate the activity of L-type calcium channels, it may be advantageous to partially reduce Ca2+ influx by inhibiting the up-regulation of CaV1.2 channels in cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension. These findings provide proof-of-principle for this concept by showing that targeting β subunits could normalize CaV1.2 channel expression, which may be used as new targets for therapeutics of cardiovascular diseases.

ZH, KL, and CL outlined, drafted, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TS critically edited and finalized the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Academic Research Fund Tier 2 Grant (T2EP30221-0042 to TS) from the Singapore Ministry of Education and Open Fund-Individual Research Grant (OF-IRG) (OFIRG20nov-0123 to TS) from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ouyang M, Zhu Y, Wang J, Zhang Q, Hu Y, Bu B, et al. Mechanical communication-associated cell directional migration and branching connections mediated by calcium channels. Integrin beta1, and N-cadherin. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:942058. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.942058

2. Martinez-Banaclocha M. Astroglial isopotentiality and calcium-associated biomagnetic field effects on cortical neuronal coupling. Cells. (2020) 9:439. doi: 10.3390/cells9020439

3. Carbone E, Lux HD. A low voltage-activated, fully inactivating ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurones. Nature. (1984) 310:501–2. doi: 10.1038/310501a0

4. Buraei Z, Yang J. The Ss subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. (2010) 90:1461–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009

5. Takahashi M, Seagar M, Jones J, Reber B, Catterall W. Subunit structure of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels from skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1987) 84:5478–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5478

6. Altier C, Garcia-Caballero A, Simms B, You H, Chen L, Walcher J, et al. The cavbeta subunit prevents Rfp2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nat Neurosci. (2011) 14:173–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.2712

7. Buraei Z, Yang J. Structure and function of the B subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. (2013) 1828:1530–40.

8. Colecraft H, Alseikhan B, Takahashi S, Chaudhuri D, Mittman S, Yegnasubramanian V, et al. Novel functional properties of ca(2+) channel beta subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J Physiol (2002) 541(Pt. 2):435–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018515

9. Ball S, Powers P, Shin H, Morgans C, Peachey N, Gregg R. Role of the beta(2) subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the retinal outer plexiform layer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2002) 43:1595–603.

10. Weissgerber P, Held B, Bloch W, Kaestner L, Chien K, Fleischmann B, et al. Reduced cardiac L-type Ca2+ current in Ca(V)Beta2-/- embryos impairs cardiac development and contraction with secondary defects in vascular maturation. Circ Res. (2006) 99:749–57. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243978.15182.c1

11. Antzelevitch C, Pollevick G, Cordeiro J, Casis O, Sanguinetti M, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by st-segment elevation, short Qt intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. (2007) 115:442–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392

12. Cordeiro J, Marieb M, Pfeiffer R, Calloe K, Burashnikov E, Antzelevitch C. Accelerated inactivation of the L-type calcium current due to a mutation in Cacnb2b underlies brugada syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2009) 46:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.014

13. Li L, Cao X, Chen S, Han H, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood A, et al. Up-regulation of cavbeta3 subunit in primary sensory neurons increases voltage-activated Ca2+ channel activity and nociceptive input in neuropathic pain. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287:6002–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310110

14. Jeon D, Song I, Guido W, Kim K, Kim E, Oh U, et al. Ablation of Ca2+ channel beta3 subunit leads to enhanced n-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent long term potentiation and improved long term memory. J Biol Chem. (2008) 283:12093–101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800816200

15. Murakami M, Nakagawasai O, Yanai K, Nunoki K, Tan-No K, Tadano T, et al. Modified behavioral characteristics following ablation of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta3 subunit. Brain Res. (2007) 1160:102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.041

16. Murakami M, Yamamura H, Murakami A, Okamura T, Nunoki K, Mitui-Saito M, et al. Conserved smooth muscle contractility and blood pressure increase in response to high-salt diet in mice lacking the beta3 subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2000) 36(Suppl. 2):S69–73. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200000006-00015

17. Murakami M, Yamamura H, Suzuki T, Kang M, Ohya S, Murakami A, et al. Modified cardiovascular L-type channels in mice lacking the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel beta3 subunit. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:43261–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211380200

18. Felix R, Calderon-Rivera A, Andrade A. Regulation of high-voltage-activated Ca(2+) channel function, trafficking, and membrane stability by auxiliary subunits. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Membr Transp Signal. (2013) 2:207–20. doi: 10.1002/wmts.93

19. Klassen T, Davis C, Goldman A, Burgess D, Chen T, Wheeler D, et al. Exome sequencing of ion channel genes reveals complex profiles confounding personal risk assessment in epilepsy. Cell. (2011) 145:1036–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.025

20. Burgess D, Jones J, Meisler M, Noebels J. Mutation of the Ca2+ channel beta subunit gene CCHB4 is associated with ataxia and seizures in the lethargic (Lh) mouse. Cell. (1997) 88:385–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81877-2

21. Zhang Y, Mori M, Burgess D, Noebels J. Mutations in high-voltage-activated calcium channel genes stimulate low-voltage-activated currents in mouse thalamic relay neurons. J Neurosci. (2002) 22:6362–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06362.2002

22. Benedetti B, Benedetti A, Flucher B. Loss of the calcium channel beta4 subunit impairs parallel fibre volley and purkinje cell firing in cerebellum of adult ataxic mice. Eur J Neurosci. (2016) 43:1486–98. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13241

23. Marmorstein L, Wu J, McLaughlin P, Yocom J, Karl M, Neussert R, et al. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1). J Gen Physiol. (2006) 127:577–89. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509473

24. Ohmori I, Ouchida M, Miki T, Mimaki N, Kiyonaka S, Nishiki T, et al. A cacnb4 mutation shows that altered ca(v)2.1 function may be a genetic modifier of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Neurobiol Dis. (2008) 32:349–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.07.017

25. Escayg A, De Waard M, Lee D, Bichet D, Wolf P, Mayer T, et al. Coding and noncoding variation of the human calcium-channel beta4-subunit gene cacnb4 in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and episodic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. (2000) 66:1531–9. doi: 10.1086/302909

26. Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, et al. A xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94:1703–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703

27. Obermair G, Schlick B, Di Biase V, Subramanyam P, Gebhart M, Baumgartner S, et al. Reciprocal interactions regulate targeting of calcium channel beta subunits and membrane expression of alpha1 subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:5776–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044271

28. Wei S, Colecraft H, DeMaria C, Peterson B, Zhang R, Kohout T, et al. Ca(2+) channel modulation by recombinant auxiliary beta subunits expressed in young adult heart cells. Circ Res. (2000) 86:175–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.175

29. Loh K, Liang M, Soong T, Hu Z. Regulation of cardiovascular calcium channel activity by post-translational modifications or interacting proteins. Pflugers Arch. (2020) 472:653–67. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02398-x

30. Luvisetto S, Fellin T, Spagnolo M, Hivert B, Brust P, Harpold M, et al. Modal gating of human Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channels: i. the slow and the fast gating modes and their modulation by beta subunits. J Gen Physiol. (2004) 124:445–61. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409034

31. Dzhura I, Neely A. Differential modulation of cardiac Ca2+ channel gating by beta-subunits. Biophys J. (2003) 85:274–89. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74473-7

32. Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch T, Campbell K. Calcium channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the i-ii cytoplasmic linker of the alpha 1-subunit. Nature. (1994) 368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0

33. Elias G, Nicoll R. Synaptic trafficking of glutamate receptors by maguk scaffolding proteins. Trends Cell Biol. (2007) 17:343–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.005

34. Chen Y, Li M, Zhang Y, He L, Yamada Y, Fitzmaurice A, et al. Structural basis of the alpha1-beta subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature. (2004) 429:675–80. doi: 10.1038/nature02641

35. Opatowsky Y, Chen C, Campbell K, Hirsch J. Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta subunit functional core and its complex with the alpha 1 interaction domain. Neuron. (2004) 42:387–99. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00250-8

36. Van Petegem F, Clark K, Chatelain F, Minor D Jr. Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel beta-subunit and an alpha-subunit domain. Nature. (2004) 429:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02588

37. Blaszczyk J, Li Y, Yan H, Ji X. Crystal structure of unligated guanylate kinase from yeast reveals gmp-induced conformational changes. J Mol Biol. (2001) 307:247–57. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4427

38. Vendel A, Rithner C, Lyons B, Horne W. Solution structure of the n-terminal a domain of the human voltage-gated Ca2+channel beta4a subunit. Protein Sci. (2006) 15:378–83. doi: 10.1110/ps.051894506

39. Maltez J, Nunziato D, Kim J, Pitt G. Essential Ca(V)beta modulatory properties are aid-independent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2005) 12:372–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb909

40. Takahashi S, Miriyala J, Colecraft H. Membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like properties of beta-subunits required for modulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2004) 101:7193–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306665101

41. Takahashi S, Miriyala J, Tay L, Yue D, Colecraft HMA. Cavbeta Sh3/guanylate kinase domain interaction regulates multiple properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol. (2005) 126:365–77. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509354

42. Chen Y, He L, Buchanan D, Zhang Y, Fitzmaurice A, Yang J. Functional dissection of the intramolecular src homology 3-guanylate kinase domain coupling in voltage-gated Ca2+ channel beta-subunits. FEBS Lett. (2009) 583:1969–75. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.001

43. De Waard M, Pragnell M, Campbell K. Ca2+ channel regulation by a conserved beta subunit domain. Neuron. (1994) 13:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90363-8

44. Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Naranjo D, Hidalgo P, Neely A. Mutations of nonconserved residues within the calcium channel alpha1-interaction domain inhibit beta-subunit potentiation. J Gen Physiol. (2008) 132:383–95. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709901

45. Röhrkasten A, Meyer H, Nastainczyk W, Sieber M, Hofmann F. Camp-dependent protein kinase rapidly phosphorylates serine- 687 of the skeletal muscle receptor for calcium channel blockers. J Biol Chem. (1988) 263:15325–9.

46. Haase H, Karczewski P, Beckert R, Krause E. Phosphorylation of the L-type calcium channel β subunit is involved in β-adrenergic signal transduction in canine myocardium. FEBS Lett. (1993) 335:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80733-B

47. Gerhardstein B, Puri T, Chien A, Hosey M. Identification of the sites phosphorylated by cyclic amp-dependent protein kinase on the B 2 subunit of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels†. Biochemistry. (1999) 38:10361–70. doi: 10.1021/bi990896o

48. Miriyala J, Nguyen T, Yue D, Colecraft H. Role of Cavβ subunits, and lack of functional reserve, in protein kinase a modulation of cardiac Cav1.2 channels. Circul Res. (2008) 102:e54–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171736

49. Brunet S, Emrick M, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall W. Phosphorylation sites in the hook domain of Cavβ subunits differentially modulate Cav1.2 channel function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 87:248–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.08.006

50. Liu G, Papa A, Katchman A, Zakharov S, Roybal D, Hennessey J, et al. Mechanism of adrenergic Ca(V)1.2 stimulation revealed by proximity proteomics. Nature. (2020) 577:695–700. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1947-z

51. Papa A, Kushner J, Hennessey J, Katchman A, Zakharov S, Chen B, et al. Adrenergic Ca(V)1.2 activation via rad phosphorylation converges at alpha(1c) I-Ii loop. Circ Res. (2021) 128:76–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317839

52. Papa A, Zakharov SI, Katchman AN, Kushner JS, Chen BX, Yang L, et al. Rad regulation of Cav1.2 channels controls cardiac fight-or-flight response. Nat Cardiovasc Res. (2022) 1:1022–38. doi: 10.1038/s44161-022-00157-y

53. Zhu J, Reynet C, Caldwell J, Kahn C. Characterization of rad, a new member of Ras/Gtpase superfamily, and its regulation by a unique gtpase-activating protein (Gap)-like activity. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:4805–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4805

54. Beguin P, Ng Y, Krause C, Mahalakshmi R, Ng M, Hunziker W. Rgk small gtp-binding proteins interact with the nucleotide kinase domain of ca2+-channel beta-subunits via an uncommon effector binding domain. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:11509–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606423200

55. Chang D, Colecraft H. Rad and rem are non-canonical g-proteins with respect to the regulatory role of guanine nucleotide binding in Ca(V)1.2 channel regulation. J Physiol. (2015) 593:5075–90. doi: 10.1113/JP270889

56. Dolphin A. B subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerget Biomembr. (2003) 35:599–620. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000008026.37790.5a

57. Chien A, Carr K, Shirokov R, Rios E, Hosey M. Identification of palmitoylation sites within the L-type calcium channel β;2a subunit and effects on channel function. J Biol Chem. (1996) 271:26465–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26465

58. Chien A, Hosey M. Post-translational modifications of β subunits of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Bioenerget Biomembr. (1998) 30:377–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1021941706726

59. Resh M. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. (1999) 1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(99)00075-0

60. Kovacs I, Lindermayr C. Nitric oxide-based protein modification: formation and site-specificity of protein s-nitrosylation. Front Plant Sci. (2013) 4:137. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00137

61. Zhou M, Bavencoffe A, Pan H. Molecular basis of regulating high voltage-activated calcium channels by s-nitrosylation. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:30616–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.685206

62. Lee S. Pharmacological inhibition of voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels for chronic pain relief. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2013) 11:606–20. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311060005

63. Hu Z, Zhang B, Lim L, Loh W, Yu D, Tan B, et al. S-nitrosylation-mediated reduction of Ca(V)1.2 surface expression and open probability underlies attenuated vasoconstriction induced by nitric oxide. Hypertension. (2022) 79:2854–66. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19103

64. Yang L, Katchman A, Kushner J, Kushnir A, Zakharov S, Chen BX, et al. Cardiac Cav1.2 channels require β subunits for β-adrenergic–mediated modulation but not trafficking. J Clin Investigat. (2019) 129:647–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI123878

65. Chen X, Nakayama H, Zhang X, Ai X, Harris D, Tang M, et al. Calcium influx through Cav1.2 Is a proximal signal for pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2011) 50:460–70. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.012

66. Tonegawa K, Otsuka W, Kumagai S, Matsunami S, Hayamizu N, Tanaka S, et al. Caveolae-specific activation loop between camkii and L-type Ca(2+) channel aggravates cardiac hypertrophy in alpha1-adrenergic stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2017) 312:H501–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00601.2016

67. Cingolani E, Ramirez Correa G, Kizana E, Murata M, Cho H, Marban E. Gene therapy to inhibit the calcium channel beta subunit: physiological consequences and pathophysiological effects in models of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. (2007) 101:166–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155721

68. Glukhov A, Balycheva M, Sanchez-Alonso J, Ilkan Z, Alvarez-Laviada A, Bhogal N, et al. Direct evidence for microdomain-specific localization and remodeling of functional L-type calcium channels in rat and human atrial myocytes. Circulation. (2015) 132:2372–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018131

69. Best J, Kamp T. Different subcellular populations of L-type Ca2+ channels exhibit unique regulation and functional roles in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2012) 52:376–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.014

70. Shaw R, Colecraft HML-. Type calcium channel targeting and local signalling in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. (2013) 98:177–86. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt021

71. Balijepalli R, Foell J, Hall D, Hell J, Kamp T. Localization of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) channels to a caveolar macromolecular signaling complex is required for beta(2)-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:7500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503465103

72. Xu X, Marx S, Colecraft H. Molecular mechanisms, and selective pharmacological rescue, of rem-inhibited Cav1.2 channels in heart. Circ Res. (2010) 107:620–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224717

73. Makarewich C, Correll R, Gao H, Zhang H, Yang B, Berretta R, et al. A caveolae-targeted L-type Ca(2)+ channel antagonist inhibits hypertrophic signaling without reducing cardiac contractility. Circ Res. (2012) 110:669–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.264028

74. Correll R, Makarewich C, Zhang H, Zhang C, Sargent M, York A, et al. Caveolae-localized L-type Ca2+ channels do not contribute to function or hypertrophic signalling in the mouse heart. Cardiovasc Res. (2017) 113:749–59. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx046

75. Sanchez-Alonso J, Bhargava A, O’Hara T, Glukhov A, Schobesberger S, Bhogal N, et al. Microdomain-specific modulation of l-type calcium channels leads to triggered ventricular arrhythmia in heart failure. Circ Res. (2016) 119:944–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308698

76. Ravi C, Balijepalli JDF, Jing W, Best JM, Kamp TJ. Targeting of Cav1.2 channels to caveolae requires cavβ subunit association with caveolin-3 in the cardiomyocytes. AHA Scientific Sessions 2008. Circulation (2008). doi: 10.1161/circ.118.suppl_18.S_339-b

77. Kharade S, Sonkusare S, Srivastava A, Thakali K, Fletcher T, Rhee S, et al. The beta3 subunit contributes to vascular calcium channel upregulation and hypertension in angiotensin ii-infused C57bl/6 mice. Hypertension. (2013) 61:137–42. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197863

78. Romero C, Wang H, Wynne B, Eaton D, Wall S. ENaC and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors interact in the connecting tubule inducing renal vasodilation and blood pressure changes. FASEB J. (2021) 35. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2021.35.S1.03028

79. Hu Z, Liang M, Soong T. Alternative splicing of L-type Ca(V)1.2 calcium channels: implications in cardiovascular diseases. Genes.(2017) 8:344. doi: 10.3390/genes8120344

80. Telemaque S, Sonkusare S, Grain T, Rhee S, Stimers J, Rusch N, et al. Design of mutant beta2 subunits as decoy molecules to reduce the expression of functional ca2+ channels in cardiac cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2008) 325:37–46. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.128215

81. Claycomb W, Lanson N Jr., Stallworth B, Egeland D, Delcarpio J, Bahinski A, et al. Hl-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1998) 95:2979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979

82. Findeisen F, Campiglio M, Jo H, Abderemane-Ali F, Rumpf C, Pope L, et al. Stapled voltage-gated calcium channel (CAV) alpha-interaction domain (AID) peptides act as selective protein-protein interaction inhibitors of Cav function. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2017) 8:1313–26. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00454

83. Van Petegem F, Duderstadt K, Clark K, Wang M, Minor D Jr. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis defines a conserved energetic hotspot in the cavalpha1 aid-cavbeta interaction site that is critical for channel modulation. Structure. (2008) 16:280–94. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.11.010

84. Chien A, Gao T, Perez-Reyes E, Hosey M. Membrane targeting of L-type calcium channels. role of palmitoylation in the subcellular localization of the beta2a subunit. J Biol Chem. (1998) 273:23590–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23590

85. Camby I, Le Mercier M, Lefranc F, Kiss R. Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology. (2006) 16:137R–57R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl025

86. Wang J, Thio S, Yang S, Yu D, Yu C, Wong Y, et al. Splice variant specific modulation of Cav1.2 calcium channel by galectin-1 regulates arterial constriction. Circ Res. (2011) 109:1250–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248849

87. Hu Z, Li G, Wang J, Chong S, Yu D, Wang X, et al. Regulation of blood pressure by targeting Cav1.2-galectin-1 protein interaction. Circulation. (2018) 138:1431–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031231

88. Morgenstern T, Park J, Fan Q, Colecraft HM. A potent voltage-gated calcium channel inhibitor engineered from a nanobody targeted to auxiliary cavbeta subunits. eLife. (2019) 8:e49253. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49253

89. Ding Y, Zhang Y, Xu C, Tao Q, Chen Y. Hect domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4l negatively regulates Wnt signaling by targeting dishevelled for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:8289–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433185

90. Catalucci D, Zhang D, DeSantiago J, Aimond F, Barbara G, Chemin J, et al. Akt regulates L-type Ca2+ channel activity by modulating cavalpha1 protein stability. J Cell Biol. (2009) 184:923–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805063

91. Rusconi F, Ceriotti P, Miragoli M, Carullo P, Salvarani N, Rocchetti M, et al. Peptidomimetic targeting of Cavbeta2 overcomes dysregulation of the l-type calcium channel density and recovers cardiac function. Circulation. (2016) 134:534–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021347

92. Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Neely A, Hidalgo P. The Src homology 3 domain of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels promotes endocytosis via dynamin interaction. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:2156–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609071200

93. Beguin P, Nagashima K, Gonoi T, Shibasaki T, Takahashi K, Kashima Y, et al. Regulation of Ca2+ channel expression at the cell surface by the small g-protein kir/gem. Nature. (2001) 411:701–6. doi: 10.1038/35079621

Keywords: voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC), CaVβ subunits, Ca2+, cardiovascular disease, post-translational modification (PTM)

Citation: Loh KWZ, Liu C, Soong TW and Hu Z (2023) β subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1119729. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1119729

Received: 09 December 2022; Accepted: 16 January 2023;

Published: 02 February 2023.

Edited by:

Ping Liao, National Neuroscience Institute (NNI), SingaporeReviewed by:

Boon-Seng Wong, Singapore Institute of Technology, SingaporeCopyright © 2023 Loh, Liu, Soong and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tuck Wah Soong,  cGhzc3R3QG51cy5lZHUuc2c=; Zhenyu Hu,

cGhzc3R3QG51cy5lZHUuc2c=; Zhenyu Hu,  cGhzaHpAbnVzLmVkdS5zZw==

cGhzaHpAbnVzLmVkdS5zZw==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.