- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 2National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Study on Abnormal Gametes and Reproductive Tract (Anhui Medical University), Hefei, China

- 3School of Pharmacy, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 4The Key Laboratory of Major Autoimmune Diseases, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 5Department of Cardiovascular, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

Mitochondria are cellular energy powerhouses that play important roles in regulating cellular processes. Mitochondrial quality control (mQC), including mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, mitochondrial fusion and fission, maintains physiological demand and adapts to changed conditions. mQC has been widely investigated in neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and cancer because of the high demand for ATP in these diseases. Although placental implantation and fetal growth similarly require a large amount of energy, the investigation of mQC in placental-originated preeclampsia (PE) is limited. We elucidate mitochondrial morphology and function in different pregnancy stages, outline the role of mQC in cellular homeostasis and PE and summarize the current findings of mQC-related PE studies. This review also provides suggestions on the future investigation of mQC in PE, which will lead to the development of new prevention and therapy strategies for PE.

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia (PE) is a leading cause of neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality, affecting 2–8% of pregnant women worldwide (1, 2). Preeclampsia is diagnosed by new-onset hypertension (systolic>140 mmHg and diastolic>90 mmHg) after 20 weeks of gestation accompanied by one or more other features: proteinuria, other maternal organ dysfunction (including liver, kidney and neurological), hematological involvement, and/or uteroplacental dysfunction, such as fetal growth restriction and/or abnormal Doppler ultrasound findings of utero-placental blood flow (3). Pre-term delivery is often the only definite treatment for PE, which is associated with adverse short- and long-term health outcomes in offspring, including a high prevalence of subsequent endocrine and metabolic diseases in children (4). Other effective treatment options are limited.

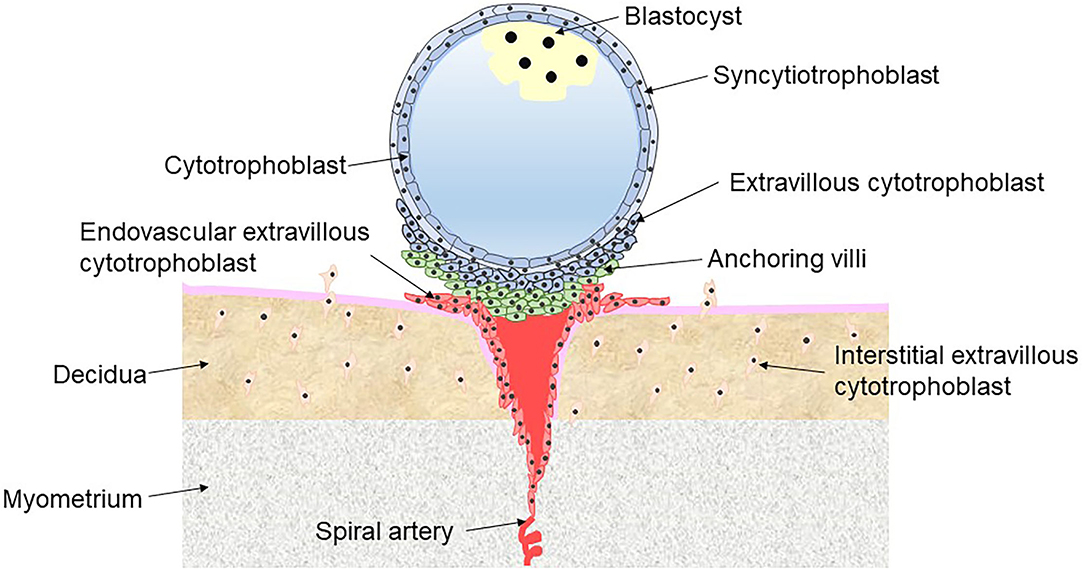

PE is a placental interface-originated disease affecting multiple organ systems (5). Abundant evidence suggests that defective implantation of placentation is the core risk factor for PE, characterized by abnormal trophoblast invasion and remodeling of the spiral arteries (6). Under normal conditions, the blastocyst is encapsulated by a shell of cytotrophoblast (CT) cells, which adhere to the uterus, penetrate into the decidua and continue to proliferate and differentiate in the first trimester. CT is an undifferentiated and proliferative trophoblast that either fuses into multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast (ST) on the surface of the shell or differentiates into extravillous cytotrophoblast (EVT) through a partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition at the interface between the outer surface of the shell and the tips of anchoring villi. ST cells facilitate the uptake of nutrients and oxygen from maternal blood and produce large quantities of placental hormones (including progesterone and hCG) to maintain pregnancy. There are two types of EVT. Interstitial EVT migrates into the lumen of the maternal decidua via the invasion of the endometrium, while endovascular EVT invades the myometrial spiral arteries involving the remodeling spiral arteries (Figure 1) (7). The myometrial spiral arteries are remodeled from high-resistance, coiled vessels to dilated low-resistance vessels because of the intervillous space at the terminal portion entered by endovascular EVT. Remodeling of the myometrial spiral arteries adapts to the increased cardiac output during pregnancy and slows the blood flow into the intervillous space of placenta, meeting the oxygen and nutrition requirements of the developing fetus (8).

Shallow placental implantation and defective spiral artery remodeling lead to placental ischemia, releasing angiogenic markers such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEng) (9). Impaired placental implantation could be triggered by the abnormalities of CT fusion into ST or abnormalities of ST differentiation into EVT (10). Flt-1 is a receptor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PIGF), which are mediators of the transformation from epithelial to endothelial phenotype to regulate the endothelial cell function. sFlt-1, a splice variant of Flt1 lacking the trans-membrane and cytoplasmic domains, performs as an antagonist of VEGF and PIGF resulting in endothelial dysfunction (11). Similarly, sEng is the shed Eng from the endothelial cell surface into maternal circulation, which binds to transforming growth factor beta 1 in circulation. Thus, free transforming growth factor beta 1 is decreased, and the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells are inhibited (9). Elevated sFlt-1 and sEng have been found in PE in dozens of human studies (9) and thus have been recognized as predictive or diagnostic biomarkers of PE (12, 13). These antiangiogenic factors lead to the following vasoconstrictive state, oxidative stress and microemboli that contribute to the clinical features of PE (9). Moreover, the administration of sEng or sFlt-1 has been shown to induce severe PE signs or adverse birth outcomes in pregnant rats (11, 14).

Mitochondrial Morphology and Function During Pregnancy

Mitochondria are the main resource of energy production for placental implantation and development. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis requires five subunit protein complexes (i.e., complexes I-V) of the electron transport chain through oxidative phosphorylation in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion (IMM). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide 2 (FADH2) produced from the tricarboxylic acid cycle expedite electrons to the electron transport chain at complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) and complex III (ubiquinone cytochrome c reductase), respectively. The electrons flow to Complex IV, reducing O2 to H2O. Meanwhile, protons (H+) are transferred from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space at complexes I, III, and IV, leading to the proton gradient and transmembrane electrical potential. The energy stored at proton gradient is used to synthesize ATP (15).

The mitochondrion is a double-membrane organelle with an ion-permeable IMM and an outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) (16). Mitochondrial morphology and function vary in different trimesters of pregnancy. In the first trimester, CT differentiation into ST leads to a shift from the classical morphology of mitochondria (0.2–0.8 μm) with lamellar cristae into small (<0.1 μm), irregular shapes with no defined cristae and low-density matrix, and this adaptation meets the increased requirement of energy production in mitochondria for embryo development (17). The smaller mitochondria in ST might facilitate the transport of cholesterol and steroidogenesis, which requires cytochrome P450scc and 3 s-hydroxysteroiddehydrogenase-Δ4−5 isomerase type I located in the IMM, to transform cholesterol into pregnenolone and then convert into progesterone (18). Sufficient steroid hormone progesterone synthesized in human placental mitochondria is essential for the maintenance of pregnancy (19). With the development of the placenta, the mitochondrial content is greater in the third trimester than in the first trimester (20). However, the respiratory rate in the third trimester is similar to that in the first trimester. Thus, the efficiency of mitochondrial respiration using oxygen is lower in the later trimester after normalization to the mitochondrial content (20).

Mitochondria consume 90% cellular O2 to synthesize ATP and are thus sensitive to oxygen tension. In the early first trimester (6–10 weeks), the spiral arteries are plugged by endovascular EVT so that oxygen tension is lower around the placenta, ~20 mmHg in the placenta and ~60 mmHg in the decidua (21). Relative hypoxia limits ATP synthesis by mitochondria, but the endometrial glands consume D-glucose to supply a large amount of ATP (22). Low O2 pressure promotes trophoblast proliferation and angiogenesis in the placenta (23, 24). With embryo growth, the spiral arteries become unblocked at the end of the first trimester, and the oxygen tension rises to ~60 mm Hg at the placenta and ~70 mm Hg at the decidua through the villous tress to meet the increased metabolic requirement (21). High O2 pressure promotes CT fusion into the ST and further invasion in the placenta (23, 25).

Hypoxic condition increases the secretion of sFlt-1 that related to the pathogenesis of PE (26). Hypoxia has been shown to reduce mitochondrial content, mitochondrial oxidative capacity and the expression of key molecules involved in the electron transport chain (27, 28). However, the dynamic alteration of mitochondrial morphology and function in PE has never been observed, which should be investigated in the future to comprehensively understand the role of mitochondria in the pathology of PE.

Reactive Free Radicals and PE

Reactive free radicals (ROS) are byproducts of oxidative phosphorylation, including superoxide (), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (OH) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−). Most ROS are produced when electrons leak from complexes I/III: the leaked electrons reduce O2 to generate , of those generated at complex I are delivered into the matrix and of those generated at complex III are released into both the matrix and the intermembrane space, and then the dismutation of to H2O2 is induced by superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in the matrix and SOD1 in the intermembrane space. Glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins are antioxidant enzymes that decompose H2O2 to . The balance between ROS and antioxidant defense maintains cellular physical function. During pregnancy, a low level of ROS upregulates transcription factor E26 transformation-specific oncogene homolog 1 and VEGF to promote angiogenesis (29) and increases mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling to facilitate trophoblast differentiation and placental development (30).

Excessive ROS overwhelm antioxidant defense, leading to detrimental effects on cell physiologies such as lipids, proteins and DNAs. Excessive ROS production and an impaired enzymatic antioxidant system are detected in PE (31). Both the direct measurement of /H2O2 and the indirect measurement of oxidative phosphorylation capacity (complex I-IV, cytochrome c oxidase) are reduced in PE (32, 33). Moreover, alterations in various proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation have been found (34, 35). On the other hand, the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes, including SODs, GPXs, thioredoxin reductases and catalase, are suppressed in PE placentas and trophoblasts (36). The decreased expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes result in the low efficiency of ATP synthesis, leading to electronic leakage and subsequent high production of ROS (37). ROS accumulation then triggers increased lipid peroxidation, including malondialdehyde (MDA), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (i.e., a production of MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal-modified proteins (38, 39).

Several well-known antioxidant nutrient supplementations have been found to prevent PE in small randomized trials, but a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that vitamin C and E, selenium, L-arginine, allicin, lycopene or coenzyme Q10 did not effectively prevent PE (40). This could be because that antioxidants increase the concentration of circulating antioxidants but cannot repair the imbalance between ROS and antioxidants (41). Moreover, a recent study (42) found that potent antioxidant MitoQ administration during late gestation alleviated PE, but treatment during early gestation exacerbated reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP)-induced PE in mice. Mild ROS has been shown to improve the proliferation, invasion and migration of CT-characterized HTR8-S/Veno cells for early placental implantation, and this could be blunted by antioxidants (42). Because mitochondrion is the main source of ROS, the lack of an effect of antioxidant therapy on PE brings out the consideration whether that mitochondrial-targeted interventions would be effective in preventing PE (40).

Mitochondrial Quality Control and PE

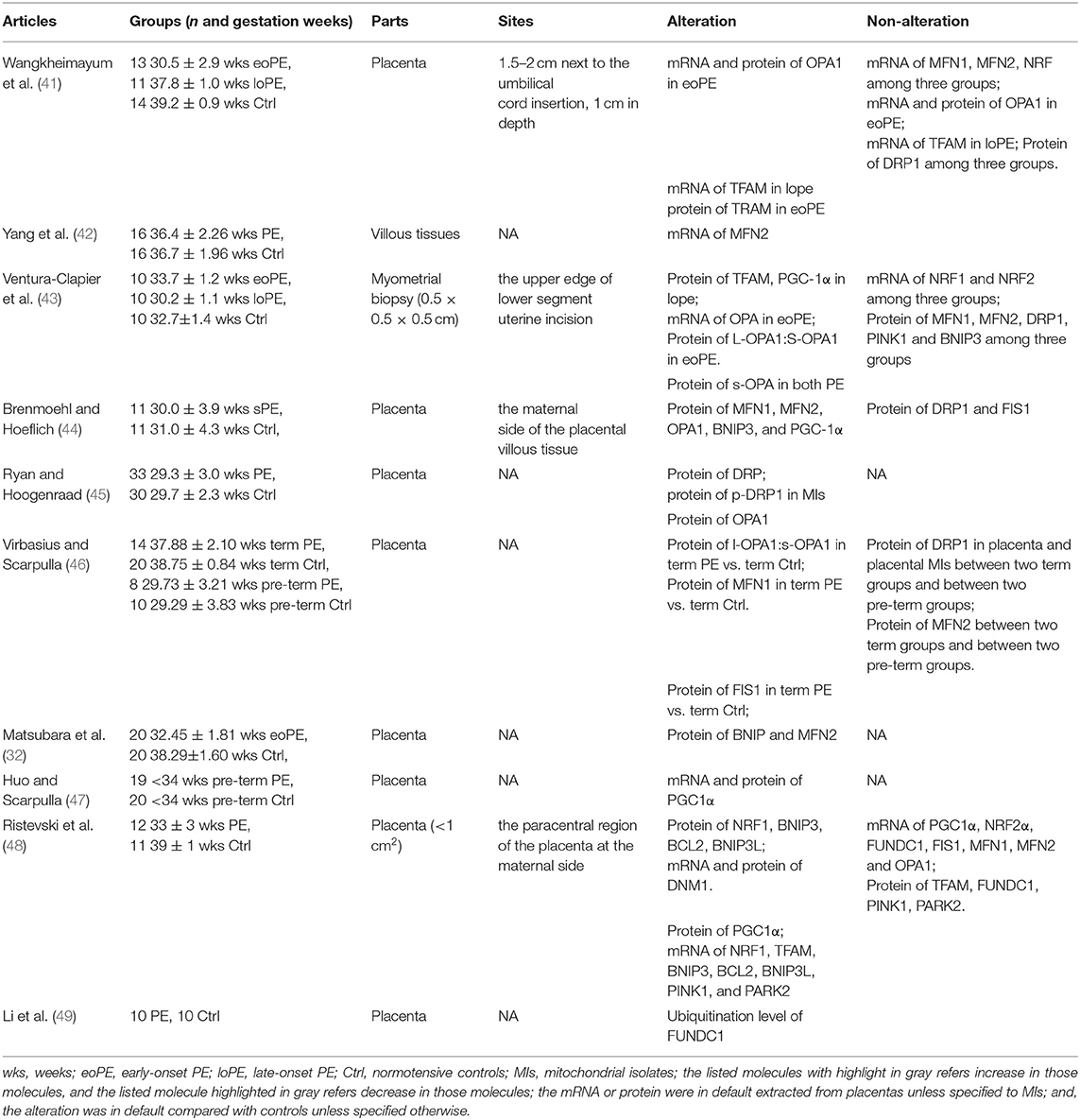

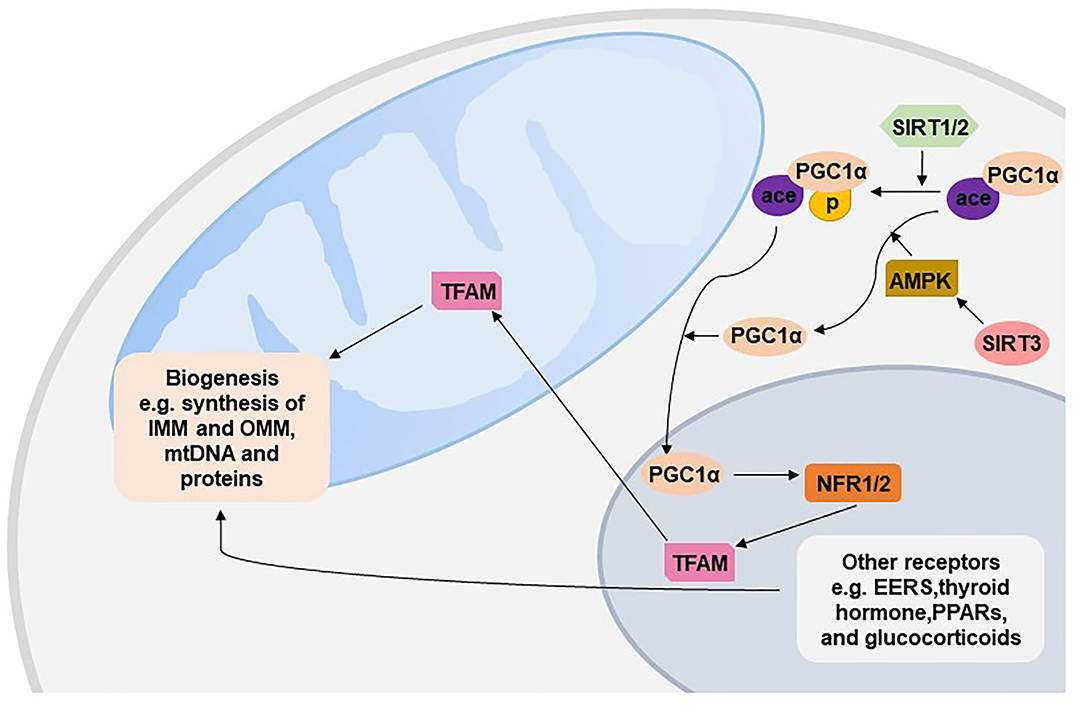

Mitochondria cannot be synthesized de novo but contain their own self-replicating genome. Coordination between mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) and biogenesis to deal with irreparably damaged mitochondria is essential for maintaining the mitochondrial volumes and determining the rate of mitochondrial turnover. Damaged mitochondrial proteins or parts of mitochondrial organelles are removed by mitophagy, and damaged components are renewed by adding proteins and lipids through biogenesis. Both mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy require mitochondrial dynamics fusion and fission. Mitochondrial dynamics, including mitochondrial fission and fusion nested in the tube-like mitochondrial network, continuously occur in response to metabolic or environmental stresses such as caloric restriction and low temperature. The integration of fusion, fission, mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis is referred to as mitochondrial quality control (mQC, Figure 2). The following text will introduce the process of mQC processes and the related predominant proteins. To our knowledge, 10 articles reported the expression of mQC-related genes in PE (Table 1), and this will also be overviewed.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of mitochondrial quality control. PINK, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; DRP1, dynamin-related protein 1; FIS1, fission 1; MFF, mitochondrial fission factor; MID49, mitochondrial dynamics protein of 49 kDa; and MID51, mitochondrial dynamics protein of 51 kDa.

Mitochondria Biogenesis

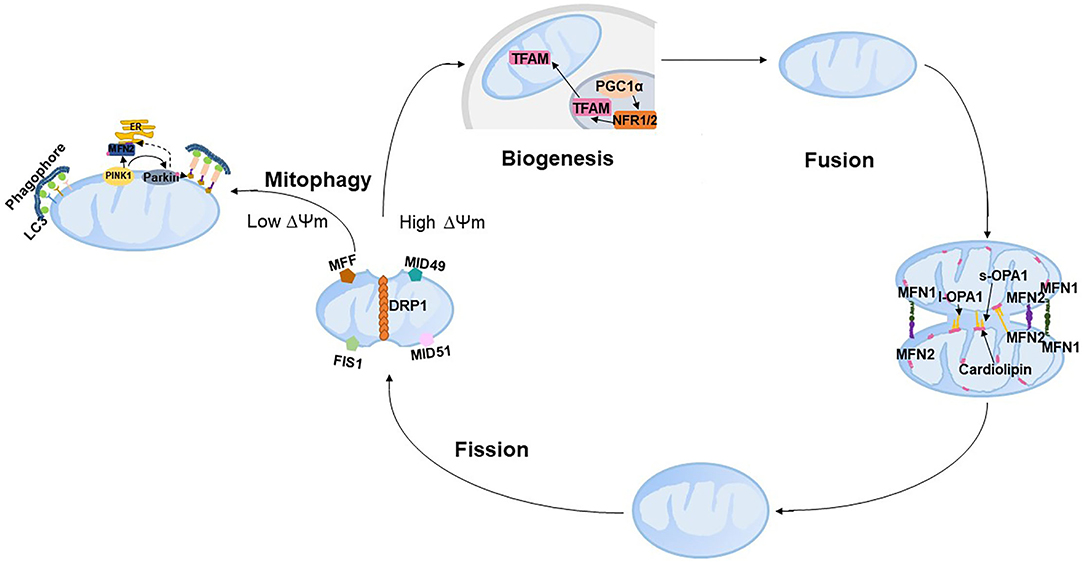

Mitochondrial biogenesis produces new mitochondria based on pre-existing mitochondria to respond to internal and external stresses such as oxidative stress, inflammation and mitochondrial drug toxicity. Mitochondrial biogenesis involves synthesis of IMM and OMM and mitochondrial encoded proteins; replication of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA); and synthesis and import of nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins. The vast majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded by the nuclear genome, and thus mitochondrial biogenesis requires exquisite coordination of both mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, such as target, importation and correction of mRNA from nuclear to mitochondria (43). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, which is activated by either phosphorylation or deacetylation in the cytoplasm and then translocates to the nucleus (44, 45). Activated c-1α in the nucleus stimulates the expression of two key transcription factors, nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) and NRF2, and further interacts with NFR1/2 to increase their transcriptional activity, leading to the increased activity of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) to replicate mtDNA and encode mitochondrial proteins (46). Moreover, NRF1/2 are essential for nuclear-mitochondrial crosstalk to adapt to mitochondrial biomass and oxidative metabolism, especially in the developmental stage. NRF1-null mice exhibit lethality at early embryos due to the dramatic lack of mtDNA content and mitochondrial membrane potential in blastocysts (47). Embryos homozygous for the null NRF2 allele die prior to implantation, which highlights the critical mitochondrial roles of NRF2 during cleavage events of the embryo (48). PGC-1α also interacts with other nuclear transcription factors, such as estrogen-related receptors, thyroid hormone, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, and glucocorticoids, to regulate mitochondrial energy metabolism, respiration, and biogenesis (43).

Mitochondrial biogenesis can be regulated by several cell signaling pathways (49). AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) activated by exercise and starvation directly phosphorylates PGC-1a or indirectly deacetylates PGC-1a to stimulate biogenesis (50). The human Sirtuin isoforms SIRT1-2 have been shown to deacetylate PGC-1a and then increase the activity of PGC-1a (51, 52); SIRT3 has been shown to increase the expression of PGC-1a through AMPK (Figure 3) (44). Recently, a decreasing trend of SIRT1 and activated AMPK/PGC-1a protein have been found in PE placentas (53), and inhibited SIRT1 and PGC-1a have been found in a group of patients with both intrauterine growth restriction and PE (54). Moreover, downregulated proteins of both SIRT3 and PGC1a were found in severe PE (55). Numerous regulators, including calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV, Akt, AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), NO, and PPARa, also activate mitochondrial biogenesis (56).

Figure 3. Mitochondrial biogenesis. EERs, estrogen-related receptors; PPARs, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; NFR, nuclear respiratory factor; SIRT, Sirtuin; AMPK, AMP-activated kinase; IMM, inner membrane of the mitochondrion; OMM, outer membrane of the mitochondrion.

Recent studies have shown decreased protein levels of PGC-1α in PE patients compared with controls (53, 55, 57), and the transcriptional level of PGC-1α was reduced in pre-term PE and pre-term controls (53) but was not altered between pre-term PE relative to term counterparts (57). All the current studies only assessed the mRNA or protein level of PGC-1α; however, activated PGC-1α (i.e., phosphorylated or deacetylated PGC-1α) has never been reported, and the expression of PGC-1α was not specified in the cytoplasm or mitochondrion. The protein level of NRF1 in pre-term PE patients has been shown to be higher than that in term controls, while the mRNA level of NRF1 was lower (57). Another study reported no difference in either the protein or mRNA expression of NRF1 between pre-term PE and pre-term counterparts (58). The number of cases of each group in the above three studies was relatively similar (i.e., 10–20), and the inconsistent results might result from the unmatched gestational age at delivery and unspecified subcellular organelles (e.g., nucleus or cytoplasm) from which PGC-1α was extracted. NFR2 has only been found to be decreased in hypoxia-induced BeWo cells (27). TFAM was 1.8-fold lower in late-onset PE placentas but not altered in early-onset PE placentas compared with control placentas (59).

Mitophagy

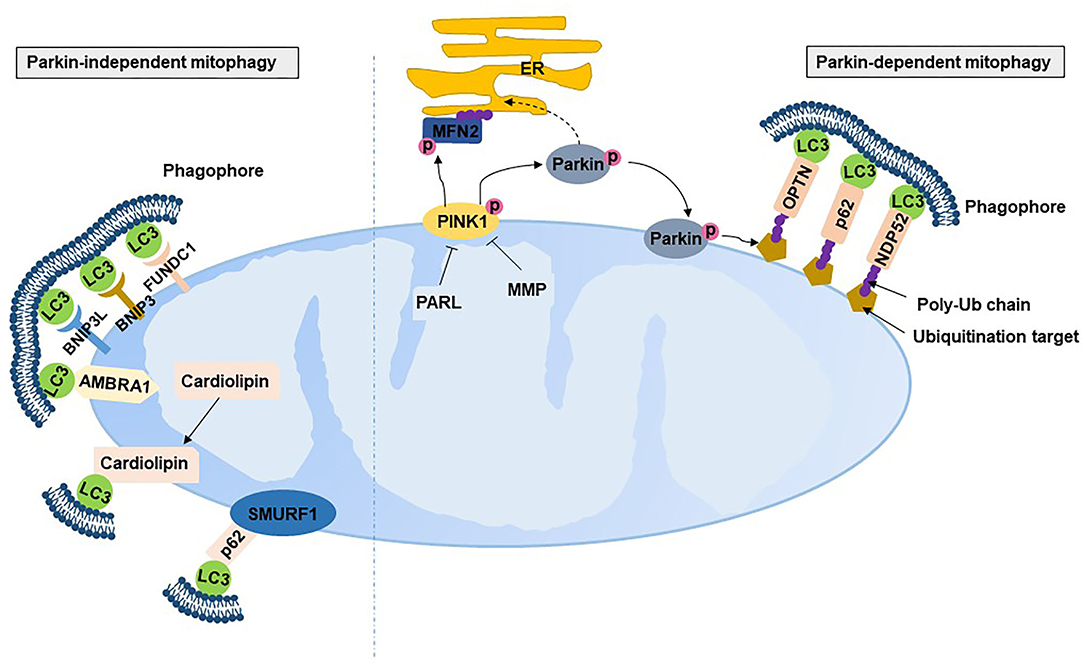

Mitophagy is the selective autophagic degradation of damaged mitochondria by autophagosomes and lysosomes. The best studied mitophagic process is the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)-Parkin mitophagy pathway. PINK1 is a serine/thereonine kinase mainly localized to the OMM (60). Under normal conditions, PINK1 located at the OMM is imported into the IMM through the translocase of the inner and outer membrane complex and then cleaved and degraded by proteases, including mitochondrial-processing protease and inner membrane presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protease (PARL) (61–63). In contrast, damaged mitochondria with an indication of depolarized membrane potential are unable to import and degrade PINK1, resulting in the accumulation of PINK1 on the OMM (61). The accumulated PINK1 on the OMM is activated by autophosphorylation, which phosphorylates the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin by phosphorylating Thr175 and Thr217 on Parkin's linker region and translocates Parkin from the cytosol to mitochondria (61). Activated Parkin binds to phosphorylated ubiquitin tethering to the OMM, leading to the conjugation of ubiquitin to various substrates and the formation of polyubiquitin (poly-Ub) chains (64). The poly-Ub chain provokes the recruitment of Ub-binding autophagy receptors, including p62/sequestosome 1, nuclear dot protein 52 and optineurin, to connect with microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and further facilitates the selective engulfment of ubiquitinated mitochondria by the autophagosome (Figure 4). A recent study has revealed that ubiquitination of the mitofusion 2 (MFN2) is one of the very first step of mitophagy that occurs prior to autophagosomal engulfment of the organelle (65). PINK1 can explicitly facilitate Parkin-dependent mitophagy and be activated in other manners. This is evidenced by Parkin mutants having more severe phenotypes than PINK-null flies (66), while Parkin overexpression rescued mitochondrial morphology (67) and arrested mitochondrial motility (68). Parkin also simulates mitochondrial biogenesis, presumably to replace damaged mitochondria with healthy and functional organelles by degrading transcriptional repression (i.e., parkin-interacting substrate) on the depolarized mitochondrion (69).

Figure 4. Mitophagy. PARL, presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protease; MMP, mitochondrial-processing protease; PINK, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; NDP52, nuclear dot protein 52; OPTN, optineurin; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; BNIP3, Bcl2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3; BNIP3L, Bcl2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3-like; FUNDC1, fun14 domain containing 1; AMBRA1, autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1; SMURF1, SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1.

Mounting evidence suggests that there are Parkin-independent mitophagic mechanisms. Several Parkin-independent proteins localize to mitochondria to recruit autophagosomes by interacting with LC3, including Bcl2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), BNIP3-like (BNIP3L) and Fun14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) (70). BNIP3 and BNIP3L bonding to Bcl-2 separates the complex of Bcl-2 with Beclin-2, resulting in the initiation of autophagosomes (71). BNIP3 and BNIP3L have been shown to be complementary to mitophagy (71) and protect against excessive ROS (72). FUNDC1 localized on the OMM can be dephosphorylated under hypoxia to interact with LC3 on autophagosome membranes (73, 74). In addition, SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 and autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1 also induce LC3 dependence in a Parkin-independent mitophagic manner (75, 76). Cardiolipin, a membrane lipid in IMM, is also an LC3 receptor. Cardiolipin translates from the IMM to the OMM with external adverse stimulation and then interacts with the N-terminal helices of LC3 (77), indicating that cardiolipin also participates in mitophagy. Studies have found that mitochondria-derived vesicles stimulated by ROS instead of mitochondrial depolarization induced a faster rate of mitochondrial turnover with the requirement of Pink1/Parkin by delivering the mitochondrial content to the lysosome, where degradation of the mitochondrial content occurs (78, 79).

Compared with Parkin-dependent mitophagy, Parkin-independent mitophagy tends to play a more crucial role in PE. One study found that PINK163kDa/53kDa ratio was increased in line with the increase in Parkin in the placentas of PE (80). PINK1 is 63 kDa under normal conditions, and cleaved PINK1 is 53 kDa. Mitophagy, as indicated by the PINK1 and Parkin proteins, was exhibited in the placentas of PE mice (81). In contrast, BNIP3-mediated mitophagy has been found to be involved in PE, evidenced by the higher protein expression of BNIPB and BNIP3L and higher mRNA expression of FUNDC1 in pre-term PE placentas compared to term controls (57). BNIP3 was inhibited in term severe PE placentas compared with term controls (55), while BNIP3 was upregulated in the pre-term early-onset PE placentas compared with the term controls (34). The ubiquitination level of FUNDC1 was low in hypoxic HTR8-S/Veno cells and the placenta of pregnant women with PE (82).

Mitochondrial Fusion

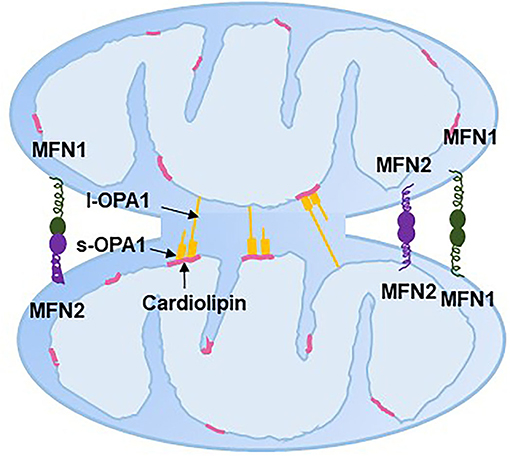

Mitochondrial fusion helps to mitigate metabolic or environmental stresses by distributing the mitochondrial contents between partially damaged mitochondria and healthy mitochondria (83). The fused mitochondria can be prevented from mitophagy (84). Mitochondrial fusion includes the fusion of both OMM and IMM and a mixture of mitochondrial contents. Mitochondrial fusion in mammalian cells is regulated by the fusion proteins MFN1/2 on the OMM and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) on the IMM, which all belong to the dynamin-related family of large nucleotide guanosine triphosphates (GTPases). The GTPase domain of MFN1/2 hydrolyses GTP, which promotes homo- and hetero-oligomerization of MFN to dock on two OMMs and initiates OMM fusion (85–87) (Figure 5). Although the GTPase activity of MFN1 was ~eightfold higher than that of MFN2, the affinity for GTP of MFN2 was more than 100-fold higher than that of MFN1 (85). This could be because that the internal interaction between the first and second heptad repeat domains of MFN2 resulted in the closed conformation of MFN2 and sequent fusion-deficiency. The closed conformation is activated by the phosphorylation at MFN2 Ser 378 (88). Replacing Ser 378 with Asp that cannot be phosphorylated has normal MFN2-mediated fusion features (88). Moreover, genetic mutations of MFN2 in murine embryonic fibroblasts interrupt mitochondrial fusion and produce large mitochondrial fragments (89). Interestingly, mutation in human MFN2 but not MFN1 results in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2A, a neurodegenerative disorder disease (90, 91). However, in MFN1-deficient Hela cells, mitochondrion failed to bind to each other and resulted in fragmentation of mitochondrion (92). Loss of either MFN1 or MFN2 causes lethality in mice, and the extracted cells from these mice display obviously fragmented mitochondria (87). These evidences suggest that MFN1/2 are dispensable for mitochondrial fusion.

Figure 5. Mitochondrial fusion. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MFN, mitofusin; l-OPA1, long-optic atrophy 1; s-OPA1, short-optic atrophy 1.

OPA1 typically has two isoforms: long/membrane-bound (l-OPA1) and short/soluble OPA1 (s-OPA1). l-OPA1 is located in the IMM, and s-OPA1 is integral in the intermembrane space. l-OPA1 can be further cleaved to s-OPA1, while overexpression of s-OPA1 leads to mitochondrial fragmentation, which might be the result of mitochondrial fission (93). The interaction between l-OPA1 on one IMM and cardiolipin on another IMM has been shown to be essential to mitochondrial fusion in vitro, with evidence that the absence of cardiolipin caused the loss of membrane fusion activity (94). Whether s-OPA1 is required for IMM fusion is still controversial. Ishihara et al. (95) and Tondera et al. (96) found that l-OPA1 is sufficient to facilitate IMM fusion, while other studies showed that both s-OPA1 and l-OPA1 are required for efficient and fast fusion (97, 98). Moreover, the l-OPA1:s-OPA1 ratio is thought to mediate the balance between fission and fusion (97). OPA1 has also been discovered to be involved in mitochondrial crista remodeling with inner membrane organization (99).

Decreased mRNA levels of MFN2 have been found in term PE placentas (100). However, a proteomics analysis found the upregulated expression of MFN2 in pre-term early-onset PE placentas compared with pre-term controls (34). The gene expression of OPA increased 2.5-fold in pre-term early-onset PE placentas compared with term controls, but there was no difference between term early-onset PE and term late-onset PE placentas (59). In contrast, the protein expression of the l-OPA1/s-OPA1 ratio and OPA1 significantly increased in placenta from term PE patients compared with term controls, but the difference was not observed between pre-term PE placenta and pre-term normal placenta (101). Another study found decreased protein expression of OPA1 in pre-term PE placentas compared with pre-term controls (80). Neither MFN1/2 nor OPA1 was altered in term PE placentas compared with controls (27), but OPA1 was upregulated in the myometrium of pre-term early-onset PE compared to pre-term controls (58). OPA1 and MFN1/2 were downregulated in severe PE placentas (55). Although the findings of mitochondrial fusion-related genes in PE patients are inconsistent, the results in PE-like trophoblast cells are coincident. Decreased mRNA and protein levels of MFN2 have been confirmed in hypoxia-induced TEV-1 cells (100), and decreased transcript levels of MFN1 and MFN2 have been found in hypoxia-induced BeWo cells (27).

Mitochondrial Fission

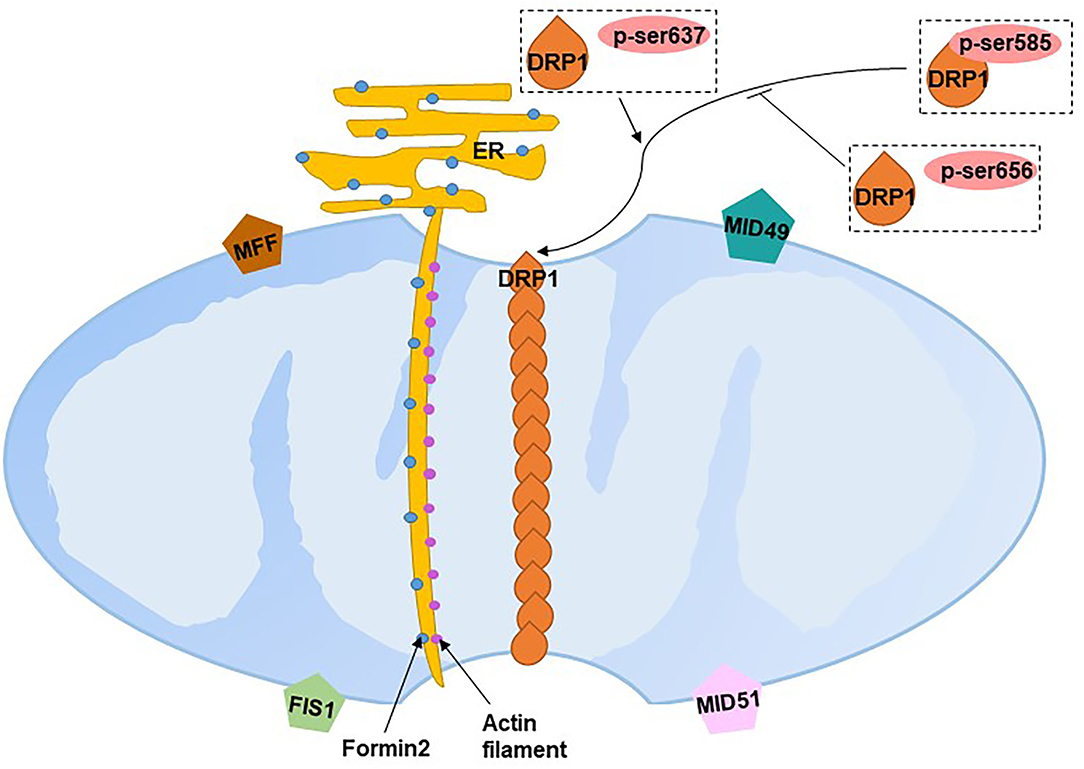

Fission segregates and uncouples damaged mitochondrial sub-organelles by dividing mitochondria from mitochondrial networks to maintain adequate numbers of mitochondria. Mitochondrial fission is primarily carried out by dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), a large GTPase. The translocation of DRP1 from the cytosol to mitochondria interacts with four receptor proteins in the OMM: fission 1 (FIS1), mitochondrial fission factor (MFF), mitochondrial dynamics protein of 49 kDa (MID49) and MID51, which initiate fission by constricting mitochondria (102). The translocation of DRP1 requires the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation at Ser of DRP1: Ser585 is phosphorylated by Cdk1/Cyclin B leading to the increased DRP1 GTPase activity at the onset of mitosis (103); the Ser656 phosphatased by PKA inhibits mitochondrial scission (104); and, dephosphorylation at Ser637 by the mitochondrial phosphatase phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 recruits DRP1 to mitochondria to drive scission (105–107). However, DRP1 recruitment at the reticulum–mitochondria contact site has been found to occur prior to recruitment at the mitochondria constrict site, where the mitochondrion starts to segregate (108). The endoplasmic reticulum tubules first wrap around the constricted parts of mitochondria in the form of rings (108). Actin filaments then accumulate between mitochondrial and inverted formin 2-enriched endoplasmic reticulum membranes at the constriction sites, which initially recruits DRP1 to drive mitochondrial fission (109) (Figure 6). DRP1, FIS1 and MFF have been found to localize to peroxisomal membranes involved in peroxisomal fission (110).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial fission. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; DRP1, dynamin-related protein 1; FIS1, fission 1; MFF, mitochondrial fission factor; MID49, mitochondrial dynamics protein of 49 kDa; MID51, mitochondrial dynamics protein of 51 kDa. Blue dots on the ER refer to formin 2, purple dots between the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum refer to actin filaments.

A recent study found two distinct types of fission on African green monkey Cos-7 cells and mouse cardiomyocytes (111). Fission at the mitochondrial periphery (<25% from a tip) divides damaged mitochondria into smaller daughter mitochondria for sequent mitophagy, whereas division at the mid-zone of mitochondria (within the central 50%) leads to mitochondrial biogenesis (111). Compared with mid-zone fission, mitochondrial fission occurring at the periphery tends to have the following characteristics: reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, matrix pH, elevated ROS and increased Ca+. Although both types are regulated by DRP1, mitochondrial-endoplasmic reticulum contact, actin preconstruction and MFF play crucial roles in mid-zone fission, whereas mitochondrial-lysosomal contact and FIS1 play essential roles in peripheral fission. Divided mitochondrial fragmentation has two fates. Daughter mitochondria with higher membrane potential (presumably good quality mitochondria) proceed to fusion, while depolarized daughter mitochondria (presumably bad quality mitochondria) are degraded by mitophagy (112).

PE placentas show increased numbers of mitochondria in CTs, but with reduced size (80, 113), which is suggestive of increased mitochondrial fission. Although the mRNA transcript level of FIS-1 was not changed (55, 57), the fission-related dynamin-1-like protein (DNM1L) protein and mRNA transcript levels were increased in placentas complicated with PE (57). The protein expression of FIS1 was decreased in term PE relative to term controls (101). Increases in DRP1 expression, activation and phosphorylation have been found in pre-term PE placentas compared with pre-term controls (80). However, there was no difference in DRP1 expression levels in either pre-term PE or term PE compared with corresponding controls (55, 59). Neither FIS-1 nor DNM1L was unaltered in hypoxia-induced placental explants, but both were increased in hypoxia-induced BeWo cells (27).

The Interaction Between Mitochondrial Dynamics and Biogenesis/Mitophagy

Many studies have found that mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, fusion or fission could be simultaneously affected by external stimuli, but the interaction between mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis/mitophagy has rarely been confirmed by intervention one molecule to observe the effect on another mQC molecule. Mitochondrial biogenesis has been found to be mediated by fusion- and fission-related proteins (114), but this lacks further confirmation. Mitochondrial dynamics are closely related to mitophagy. MFN2 phosphorylated by PINK1 regulates the recruitment of Parkin to depolarize mitochondria and facilitates Parkin-mediated ubiquitination (115). Chen and Dorn (115). found that the absence of MFN2 in mouse cardiac myocytes prevented the translocation of Parkin to depolarized mitochondria and then inhibited mitophagy OPA1 has also been shown to interact with lysine 70 of FUNDC1, which facilitates OPA1-mediated fusion, moreover, mutants of lysine 70 inhibit the interaction and thus promote FUNDC1-regulated mitophagy (116). Overexpressing OPA1 reduces the majority of mitophagy (117). Fission is required for mitophagy, as evidenced by mitophagy being prevented with a dominant-negative mutant of DRP1 (117, 118). Inhibition of mitochondrial fission by lowering the expression of FIS1 also reduces mitochondrial mitophagy (117, 118). Fusion and fission have been shown to be paired consecutive events, and fission quickly follows fusion (117). Furthermore, DRP1 interacts with MFN to increase elongated mitochondria by promoting fusion and inhibiting fission (119). However, the interaction between mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis/mitophagy in PE has not been investigated, and this requires further studies to be helpful to explore the mQC-targeted treatment.

Summary of Current Studies in Humans and Future Directions

Ten human studies have reported the alteration of mQC-related molecules in PE since 2015, while there are several limitations: (1) The numbers of clinical cases were small, ranging from 10 to 33. (2) 60% of these studies did not elucidate where the examined tissues were collected (e.g., at the maternal side or the fetal side). (3) In 30% of these studies, the gestational week at delivery between control and PE groups was not comparable. The expression of mQC-related molecules varies on the different gestational weeks, and thus the gestational week should be equivalent for comparison. (4) Only two studies isolated mitochondrial mRNA and protein from total mRNA and protein. The subcellular organelle where the mRNA or protein extracted is critical for molecular examination because several mQC-related molecules widely distribute in the cytosol, nucleus and mitochondrion, but the research scope of the above studies limit to the mitochondria. (5) The assessment of mQC-related molecules in humans should be verified in trophoblast cells or RUPP rats to reduce the bias of species differences and large fluctuation of human individuals. Therefore, future studies should be performed with larger sample size, comparable gestational weeks, clear distinction of the site where tissues were collected and the subcellular organelle where the molecules were assessed, and verification of results in other species. The future comprehensive human mQC-related PE studies will help to provide the clinical basis for mQC-targeted treatment of PE.

Conclusion

mQC has been emerged as the treatment target of several diseases, including neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Current studies have revealed that mQC-related molecules are associated with PE, although there are several drawbacks of these studies. These findings suggest that mQC plays an important role in the progression of PE, but further investigations for deeper elucidation are required. The future investigation of mQC in PE may provide a new insight on prevention and therapy strategies for PE.

Author Contributions

XP contributed to relevant studies collection and summarisation and drafted manuscript. RH and YY: contributed to relevant studies collection and summarisation. ZL and YC: contributed to project conception and critical revision of manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work has been supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-82000399).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. (2010) 376:631–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6

2. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 133:e1–25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003018

3. Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy FP, Saito S, et al. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregn Hypertens. (2018) 13:291–310. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.05.004

4. Walani SR. Global burden of pre-term birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2020) 150:31–3. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13195

5. Ives CW, Sinkey R, Rajapreyar I, Tita ATN, Oparil S. Preeclampsia-pathophysiology and clinical presentations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.014

6. Sircar M, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. (2015) 24:131–8. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000105

7. Boss AL, Chamley LW, James JL. Placental formation in early pregnancy: how is the centre of the placenta made? Hum Reprod Update. (2018) 24:750–60. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy030

8. Abbas Y, Turco MY, Burton GJ, Moffett A. Investigation of human trophoblast invasion in vitro. Hum Reprod Update. (2020) 26:501–13. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmaa017

9. Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352

10. Farah O, Nguyen C, Tekkatte C, Parast MM. Trophoblast lineage-specific differentiation and associated alterations in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Placenta. (2020) 102:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.02.007

11. Maynard SE, Min J-Y, Merchan J, Lim K-H, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. (2003) 111:649–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189

12. Leanos-Miranda A, Navarro-Romero CS, Sillas-Pardo LJ, Ramirez-Valenzuela KL, Isordia-Salas I, Jimenez-Trejo LM. Soluble endoglin as a marker for preeclampsia, its severity, and the occurrence of adverse outcomes. Hypertension. (2019) 74:991–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13348

13. Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine F, Vatish M, Staff AC, Sennstrom M, et al. Predictive value of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in women with suspected preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414838

14. Chang X, Yao J, He Q, Liu M, Duan T, Wang K. Exosomes from women with preeclampsia induced vascular dysfunction by delivering sFlt (Soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase)-1 and sEng (Soluble Endoglin) to endothelial cells. Hypertension. (2018) 72:1381–90. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11706

15. Hu XQ, Zhang L. Hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction in pregnancy complications. Antioxidants. (2021) 10:405. doi: 10.3390/antiox10030405

16. Balaban RS. Regulation of oxidative phosphorylation in the mammalian cell. Am J Physiol. (1990) 258(3 Pt 1):C377–89. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.3.C377

17. Holland O, Dekker Nitert M, Gallo LA, Vejzovic M, Fisher JJ, Perkins AV. Review: placental mitochondrial function and structure in gestational disorders. Placenta. (2017) 54:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.012

18. Tuckey RC, Kostadinovic Z, Cameron KJ. Cytochrome P-450scc activity and substrate supply in human placental trophoblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (1994) 105:103–9. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90041-8

19. Tuckey RC. Progesterone synthesis by the human placenta. Placenta. (2005) 26:273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.012

20. Holland OJ, Hickey AJR, Alvsaker A, Moran S, Hedges C, Chamley LW, et al. Changes in mitochondrial respiration in the human placenta over gestation. Placenta. (2017) 57:102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.06.011

21. Jauniaux E, Watson A, Burton G. Evaluation of respiratory gases and acid-base gradients in human fetal fluids and uteroplacental tissue between 7 and 16 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2001) 184:998–1003. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111935

22. Frolova AI, O'Neill K, Moley KH. Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits glucose flux through the pentose phosphate pathway in human and mouse endometrial stromal cells, preventing decidualization and implantation. Mol Endocrinol. (2011) 25:1444–55. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-0026

23. Genbacev O, Zhou J, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science. (1997) 277:1669–72. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669

24. Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Jauniaux E. Regulation of vascular growth and function in the human placenta. Reproduction. (2009) 138:895–902. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0092

25. Aye I, Aiken CE, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS. Placental energy metabolism in health and disease-significance of development and implications for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 226:S928–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.005

26. Li H, Gu B, Zhang Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y. Hypoxia-induced increase in soluble Flt-1 production correlates with enhanced oxidative stress in trophoblast cells from the human placenta. Placenta. (2005) 26:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.05.004

27. Vangrieken P, Al-Nasiry S, Bast A, Leermakers PA, Tulen CBM, Janssen GMJ, et al. Hypoxia-induced mitochondrial abnormalities in cells of the placenta. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0245155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245155

28. Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Higgins JS, Vaughan OR, Murray AJ, Fowden AL. Placental mitochondria adapt developmentally and in response to hypoxia to support fetal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 116:1621–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816056116

29. Yasuda M, Ohzeki Y, Shimizu S, Naito S, Ohtsuru A, Yamamoto T, et al. Stimulation of in vitro angiogenesis by hydrogen peroxide and the relation with ETS-1 in endothelial cells. Life Sci. (1999) 64:249–58. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00560-8

30. Mudgett JS, Ding J, Guh-Siesel L, Chartrain Na, Yang L, Gopal S, et al. Essential role for p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97:10454–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316397

31. Bharadwaj SK, Vishnu Bhat B, Vickneswaran V, Adhisivam B, Bobby Z, Habeebullah S. Oxidative stress, antioxidant status and neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates born to pre-eclamptic mothers. Indian J Pediatr. (2018) 85:351–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2560-5

32. Matsubara S, Minakami H, Sato I, Saito T. Decrease in cytochrome c oxidase activity detected cytochemically in the placental trophoblast of patients with pre-eclampsia. Placenta. (1997) 18:255–9. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(97)80059-8

33. Furui T, Kurauchi O, Tanaka M, Mizutani S, Ozawa T, Tomoda Y. Decrease in cytochrome c oxidase and cytochrome oxidase subunit I messenger RNA levels in preeclamptic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. (1994) 84:283–8.

34. Xu Z, Jin X, Cai W, Zhou M, Shao P, Yang Z, et al. Proteomics analysis reveals abnormal electron transport and excessive oxidative stress cause mitochondrial dysfunction in placental tissues of early-onset preeclampsia. Proteomics Clin Appl. (2018) 12:e1700165. doi: 10.1002/prca.201700165

35. Shi Z, Long W, Zhao C, Guo X, Shen R, Ding H. Comparative proteomics analysis suggests that placental mitochondria are involved in the development of pre-eclampsia. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e64351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064351

36. Kumar CA, Das UN. Lipid peroxides, anti-oxidants and nitric oxide in patients with pre-eclampsia and essential hypertension. Med Sci Monit. (2000) 6:901–7.

37. Vaka VR, McMaster KM, Cunningham MW Jr, Ibrahim T, Hazlewood R, Usry N, et al. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species in mediating hypertension in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. (2018) 72:703–11. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11290

38. Shibata ENH, Ejima K, Araki M, Fukuda J, Yoshimura K, Toki N, et al. Enhancement of mitochondrial oxidative stress and up-regulation of antioxidant protein peroxiredoxin III/SP-22 in the mitochondria of human pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta. (2003) 24:698–705. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(03)00083-3

39. Wang Y, Walsh SW. Placental mitochondria as a source of oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia. Placenta. (1998) 19:581–6. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(98)90018-2

40. Tenorio MB, Ferreira RC, Moura FA, Bueno NB, Goulart MOF, Oliveira ACM. Oral antioxidant therapy for prevention and treatment of preeclampsia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 28:865–76. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.06.002

41. Wangkheimayum S, Kumar S, Suri V. Effect of vitamin E on sP-selectin levels in pre-eclampsia. Indian J Clin Biochem. (2011) 26:169–71. doi: 10.1007/s12291-010-0102-2

42. Yang Y, Xu P, Zhu F, Liao J, Wu Y, Hu M, et al. The potent antioxidant mitoq protects against preeclampsia during late gestation but increases the risk of preeclampsia when administered in early pregnancy. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2021) 34:118–36. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7891

43. Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. (2008) 79:208–17. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098

44. Brenmoehl J, Hoeflich A. Dual control of mitochondrial biogenesis by sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3. Mitochondrion. (2013) 13:755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.04.002

45. Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. Mitochondrial-nuclear communications. Annu Rev Biochem. (2007) 76:701–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.091720

46. Virbasius JV, Scarpulla RC. Activation of the human mitochondrial transcription factor A gene by nuclear respiratory factors: a potential regulatory link between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression in organelle biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1994) 91:1309–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1309

47. Huo L, Scarpulla RC. Mitochondrial DNA instability and peri-implantation lethality associated with targeted disruption of nuclear respiratory factor 1 in mice. Mol Cell Biol. (2001) 21:644–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.644-654.2001

48. Ristevski S, O'Leary DA, Thornell AP, Owen MJ, Kola I, Hertzog PJ. The ETS transcription factor GABPalpha is essential for early embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24:5844–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5844-5849.2004

49. Li PA, Hou X, Hao S. Mitochondrial biogenesis in neurodegeneration. J Neurosci Res. (2017) 95:2025–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24042

50. Cantó C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2009) 20:98–105. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4

51. Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. (2005) 434:113–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03354

52. Krishnan J, Danzer C, Simka T, Ukropec J, Walter KM, Kumpf S, et al. Dietary obesity-associated Hif1α activation in adipocytes restricts fatty acid oxidation and energy expenditure via suppression of the Sirt2-NAD+ system. Genes Dev. (2012) 26:259–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.180406.111

53. Hastie R, Brownfoot FC, Pritchard N, Hannan NJ, Cannon P, Nguyen V, et al. EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) signaling and the mitochondria regulate sFlt-1 (Soluble FMS-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1) secretion. Hypertension. (2019) 73:659–70. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12300

54. Poidatz D, Dos Santos E, Duval F, Moindjie H, Serazin V, Vialard F, et al. Involvement of estrogen-related receptor-γ and mitochondrial content in intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Fertil Steril. (2015) 104:483–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.005

55. Zhou X, Han TL, Chen H, Baker PN, Qi H, Zhang H. Impaired mitochondrial fusion, autophagy, biogenesis and dysregulated lipid metabolism is associated with preeclampsia. Exp Cell Res. (2017) 359:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.07.029

56. Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. (2010) 47:69–84. doi: 10.1042/bse0470069

57. Vangrieken P, Al-Nasiry S, Bast A, Leermakers PA, Tulen CBM, Schiffers PMH, et al. Placental mitochondrial abnormalities in preeclampsia. Reprod Sci. (2021) 28:2186–99. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00464-y

58. Vishnyakova PA, Volodina MA, Tarasova NV, Marey MV, Kan NE, Khodzhaeva ZS, et al. Alterations in antioxidant system, mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy in preeclamptic myometrium. BBA Clin. (2017) 8:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2017.06.002

59. Vishnyakova PA, Volodina MA, Tarasova NV, Marey MV, Tsvirkun DV, Vavina OV, et al. Mitochondrial role in adaptive response to stress conditions in preeclampsia. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:32410. doi: 10.1038/srep32410

60. Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2011) 12:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028

61. Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. (2010) 1:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298

62. Deas E, Plun-Favreau H, Gandhi S, Desmond H, Kjaer S, Loh SH, et al. PINK1 cleavage at position A103 by the mitochondrial protease PARL. Hum Mol Genet. (2011) 5:867–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq526

63. Greene AW, Grenier K, Aguileta MA, Muise S, Farazifard R, Haque ME, et al. Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Rep. (2012) 4:378–85. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.14

64. Okatsu K, Koyano F, Kimura M, Kosako H, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, et al. Phosphorylated ubiquitin chain is the genuine Parkin receptor. J Cell Biol. (2015) 209:111–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410050

65. McLelland GL, Goiran T, Yi W, Dorval G, Chen CX, Lauinger ND, et al. Mfn2 ubiquitination by PINK1/parkin gates the p97-dependent release of ER from mitochondria to drive mitophagy. Elife. (2018) 7:e32866. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32866

66. Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:1638–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105

67. Greene JC, Whitworth AJ, Kuo I, Andrews LA, Feany MB, Pallanck LJ. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:4078–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100

68. Wang X, Winter D, Ashrafi G, Schlehe J, Wong YL, Selkoe D, et al. PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell. (2011) 147:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.018

69. Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee YI, Pletinkova O, et al. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1α contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Cell. (2011) 144:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010

70. Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. (2009) 16:939–46. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.16

71. Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouysségur J, et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol. (2009) 29:2570–81. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00166-09

72. Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. (2008) 283:10892–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200

73. Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, Chen M, Zheng Q, Song P, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. (2012) 14:177–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb2422

74. Chen G, Han Z, Feng D, Chen Y, Chen L, Wu H, et al. A regulatory signaling loop comprising the PGAM5 phosphatase and CK2 controls receptor-mediated mitophagy. Mol Cell. (2014) 54:362–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.034

75. Orvedahl A, Sumpter R Jr, Xiao G, Ng A, Zou Z, Tang Y, et al. Image-based genome-wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors. Nature. (2011) 480:113–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10546

76. Strappazzon F, Nazio F, Corrado M, Cianfanelli V, Romagnoli A, Fimia GM, et al. AMBRA1 is able to induce mitophagy via LC3 binding, regardless of PARKIN and p62/SQSTM1. Cell Death Differ. (2015) 22:419–32. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.139

77. Chu CT, Ji J, Dagda RK, Jiang JF, Tyurina YY, Kapralov AA, et al. Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat Cell Biol. (2013) 15:1197–205. doi: 10.1038/ncb2837

78. McLelland G-L, Soubannier V, Chen CX, McBride HM, Fon EA. Parkin and PINK1 function in a vesicular trafficking pathway regulating mitochondrial quality control. EMBO J. (2014) 4:282–95. doi: 10.1002/embj.201385902

79. Martinus RD, Garth GP, Webster TL, Cartwright P, Naylor DJ, Hoj PB, et al. Selective induction of mitochondrial chaperones in response to loss of the mitochondrial genome. Eur J Biochem. (1996) 240:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0098h.x

80. Ausman J, Abbade J, Ermini L, Farrell A, Tagliaferro A, Post M, et al. Ceramide-induced BOK promotes mitochondrial fission in preeclampsia. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:298. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0360-0

81. Chen G, Lin Y, Chen L, Zeng F, Zhang L, Huang Y, et al. Role of DRAM1 in mitophagy contributes to preeclampsia regulation in mice. Mol Med Rep. (2020) 22:1847–58. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11269

82. Chen G, Chen L, Huang Y, Zhu X, Yu Y. Increased FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) ubiquitination level inhibits mitophagy and alleviates the injury in hypoxia-induced trophoblast cells. Bioengineered. (2021) 3:3620–33. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1997132

83. Youle RJ, Van Der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science. (2012) 337:1062–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1219855

84. Rambold AS, Kostelecky B, Elia N, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:10190–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107402108

85. Ishihara N, Eura Y, Mihara K. Mitofusin 1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via GTPase activity. J Cell Sci. (2004) 117(Pt 26):6535–46. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01565

86. Ishihara N, Otera H, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation and physiologic functions of GTPases in mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2013) 19:389–99. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4830

87. Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. (2003) 160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046

88. Rocha AG, Franco A, Krezel AM, Rumsey JM, Alberti JM, Knight WC, et al. MFN2 agonists reverse mitochondrial defects in preclinical models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A. Science. (2018) 360:336–41. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1785

89. Franco A, Kitsis RN, Fleischer JA, Gavathiotis E, Kornfeld OS, Gong G, et al. Correcting mitochondrial fusion by manipulating mitofusin conformations. Nature. (2016) 540:74–9. doi: 10.1038/nature20156

90. Züchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet. (2004) 36:449–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1341

91. Rouzier C, Bannwarth S, Chaussenot A, Chevrollier A, Verschueren A, Bonello-Palot N, et al. The MFN2 gene is responsible for mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy 'plus' phenotype. Brain. (2012) 135(Pt 1):23–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr323

92. Eura Y, Ishihara N, Yokota S, Mihara K. Two mitofusin proteins, mammalian homologues of FZO, with distinct functions are both required for mitochondrial fusion. J Biochem. (2003) 134:333–44. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg150

93. Anand R, Wai T, Baker MJ, Kladt N, Schauss AC, Rugarli E, et al. The i-AAA protease YME1L and OMA1 cleave OPA1 to balance mitochondrial fusion and fission. J Cell Biol. (2014) 204:919–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308006

94. Ban T, Ishihara T, Kohno H, Saita S, Ichimura A, Maenaka K, et al. Molecular basis of selective mitochondrial fusion by heterotypic action between OPA1 and cardiolipin. Nat Cell Biol. (2017) 19:856–63. doi: 10.1038/ncb3560

95. Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J. (2006) 25:2966–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184

96. Tondera D, Grandemange S, Jourdain A, Karbowski M, Mattenberger Y, Herzig S, et al. SLP-2 is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J. (2009) 28:1589–600. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.89

97. Ge Y, Shi X, Boopathy S, McDonald J, Smith AW, Chao LH. Two forms of Opa1 cooperate to complete fusion of the mitochondrial inner-membrane. Elife. (2020) 9:e50973. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50973

98. Song Z, Chen H, Fiket M, Alexander C, Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. (2007) 178:749–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110

99. Meeusen S, DeVay R, Block J, Cassidy-Stone A, Wayson S, McCaffery JM, et al. Mitochondrial inner-membrane fusion and crista maintenance requires the dynamin-related GTPase Mgm1. Cell. (2006) 127:383–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.021

100. Yu J, Guo X, Chen R, Feng L. Downregulation of mitofusin 2 in placenta is related to preeclampsia. Biomed Res Int. (2016) 2016:6323086. doi: 10.1155/2016/6323086

101. Holland OJ, Cuffe JSM, Dekker Nitert M, Callaway L, Kwan Cheung KA, Radenkovic F, et al. Placental mitochondrial adaptations in preeclampsia associated with progression to term delivery. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:1150. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1190-9

102. Ni HM, Williams JA, Ding WX. Mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial quality control. Redox Biol. (2015) 4:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.11.006

103. Taguchi N, Ishihara N, Jofuku A, Oka T, Mihara K. Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:11521–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607279200

104. Cribbs JT, Strack S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep. (2007) 8:939–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401062

105. Kalia R, Wang RY, Yusuf A, Thomas PV, Agard DA, Shaw JM, et al. Structural basis of mitochondrial receptor binding and constriction by DRP1. Nature. (2018) 558:401–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0211-2

106. Wang Z, Jiang H, Chen S, Du F, Wang X. The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways. Cell. (2012) 148:228–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.030

107. Moujalled DM, Cook WD, Murphy JM, Vaux DL. Necroptosis induced by RIPK3 requires MLKL but not Drp1. Nature. (2015) 517:311–20. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.18

108. Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M, DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J, Voeltz GK. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. (2011) 334:358–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385

109. Farida Korobova VR, Henry Higgs N. An Actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2. Science. (2013) 339:464–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1228360

110. Camoes F, Bonekamp NA, Delille HK, Schrader M. Organelle dynamics and dysfunction: a closer link between peroxisomes and mitochondria. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2009) 32:163–80. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1018-3

111. Kleele T, Rey T, Winter J, Zaganelli S, Mahecic D, Perreten Lambert H, et al. Distinct fission signatures predict mitochondrial degradation or biogenesis. Nature. (2021) 593:435–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03510-6

112. Zorov DB, Vorobjev IA, Popkov VA, Babenko VA, Zorova LD, Pevzner IB, et al. Lessons from the discovery of mitochondrial fragmentation (fission): a review and update. Cells. (2019) 8:175. doi: 10.3390/cells8020175

113. Zsengellér ZK, Rajakumar A, Hunter JT, Salahuddin S, Rana S, Stillman IE, et al. Trophoblast mitochondrial function is impaired in preeclampsia and correlates negatively with the expression of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1. Pregn Hypertens. (2016) 6:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.06.004

114. Yin K, Zhu R, Wang S, Zhao RC. Low-level laser effect on proliferation, migration, and antiapoptosis of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. (2017) 26:762–75. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0332

115. Chen Y, Dorn GW II. PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. (2013) 340:471–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031

116. Chen M, Chen Z, Wang Y, Tan Z, Zhu C, Li Y, et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy. (2016) 12:689–702. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1151580

117. Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. (2008) 27:433–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963

118. Shirihai OS, Song M, Dorn GW II. How mitochondrial dynamism orchestrates mitophagy. Circ Res. (2015) 116:1835–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306374

Keywords: mitochondrial quality control, mitophagy, biogenesis, fusion, fission, preeclampsia

Citation: Peng X, Hou R, Yang Y, Luo Z and Cao Y (2022) Current Studies of Mitochondrial Quality Control in the Preeclampsia. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:836111. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.836111

Received: 15 December 2021; Accepted: 02 February 2022;

Published: 28 February 2022.

Edited by:

María Galán, Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research, SpainReviewed by:

Antonietta Franco, Washington University in St. Louis, United StatesMarco Mongillo, University of Padua, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Peng, Hou, Yang, Luo and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunxia Cao, Y2FveXVueGlhNTk3MkBhaG11LmVkdS5jbg==; Zhigang Luo, cGVuZ3hxOTJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Xiaoqing Peng

Xiaoqing Peng Ruirui Hou3,4

Ruirui Hou3,4 Yunxia Cao

Yunxia Cao