- 1Cancer Institute, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China

- 2Department of Dermatology, The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China

- 3Candidate Branch of National Clinical Research Center for Skin Diseases, Beijing, China

Background: Several studies have investigated the relationship between psoriasis and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Previous meta-analyses have shown psoriasis to be a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. However, the relationship has become uncertain with the emergence of many new studies.

Objective: This study aimed to conduct an updated meta-analysis on cohort studies about the relationship between psoriasis and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods: Electronic databases (accessed till January 2022) were searched systematically for cohort studies assessing the cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients. This was a meta-analysis using a random-effect model; pooled analyses of several cardiovascular outcomes were also conducted.

Results: A total of 31 [hazard ratio (HR), 23; rate ratio (RR), 8] studies involving 665,009 patients with psoriasis and 17,902,757 non-psoriatic control subjects were included for the meta analysis. The pooled analyses according to each cardiovascular outcome revealed that pooled RR of patients for developing myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, ischemic heart disease, thromboembolism and arrhythmia were 1.17 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11–1.24), 1.19 (95% CI, 1.11–1.27), 1.46 (95% CI, 1.26–1.69), 1.17 (95% CI, 1.02–1.34), 1.36 (95% CI, 1.20–1.55) and 1.35 (95% CI, 1.30–1.40), respectively. Meanwhile, the pooled RR of patients with mild and severe psoriasis for developing adverse cardiovascular outcomes were 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13–1.24) and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.31–1.52), respectively.

Conclusion: The pooled analyses revealed that psoriasis is associated with all adverse cardiovascular outcomes of interest, especially in severe patients. Psoriasis remains an independent risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, which needs more attention from clinicians.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease (1) which affects sixty million adults and children worldwide (2). It is mainly characterized by dry, erythematous, round or scaly patches of the skin. The disease affects the daily activities and sleeps of patients and significantly reduces their quality of life (3). Studies have shown that psoriasis shares the same risk factors with cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as hypertension, obesity, smoking, and diabetes mellitus (4). Moreover, psoriasis also shares a similar immune-inflammatory mechanism with atherosclerosis, one of the CVDs, which all involve T-helper cell type 1 and type 17 activation and decreased T-regulatory cell function (4, 5). Therefore, psoriasis might be an independent risk factor for the development of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Generally speaking, CVD is a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels, including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and aortic atherosclerosis. Unexpected sudden events caused by CVD such as myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death etc. are also called cardiovascular events (CVE) in clinic practice. CVD is a major public health concern that affecting millions of people worldwide. It was the leading cause of death in the twenty-first century, accounting for about a third of all global deaths (6). Obesity and hypertension are known and established risk factors for CVD (7–10); however, due to the complex etiology of CVD, other related risk factors still need to be further recognized and confirmed. So far, the correlation between psoriasis and CVD was investigated by several studies, but the results were inconsistent (11–13). Although two meta-analyses summarized the relationship between psoriasis and cardiovascular outcomes, they included more case–control studies than cohort studies (14, 15). An updated meta-analysis was needed to confirm this relationship with the emergence of many new clinical studies. Hence, we intended to conduct a meta-analysis of the original cohort studies published before January 2022, which represents the highest level of evidence of the relationship between psoriasis and adverse cardiovascular outcomes among all observational studies.

Materials and Methods

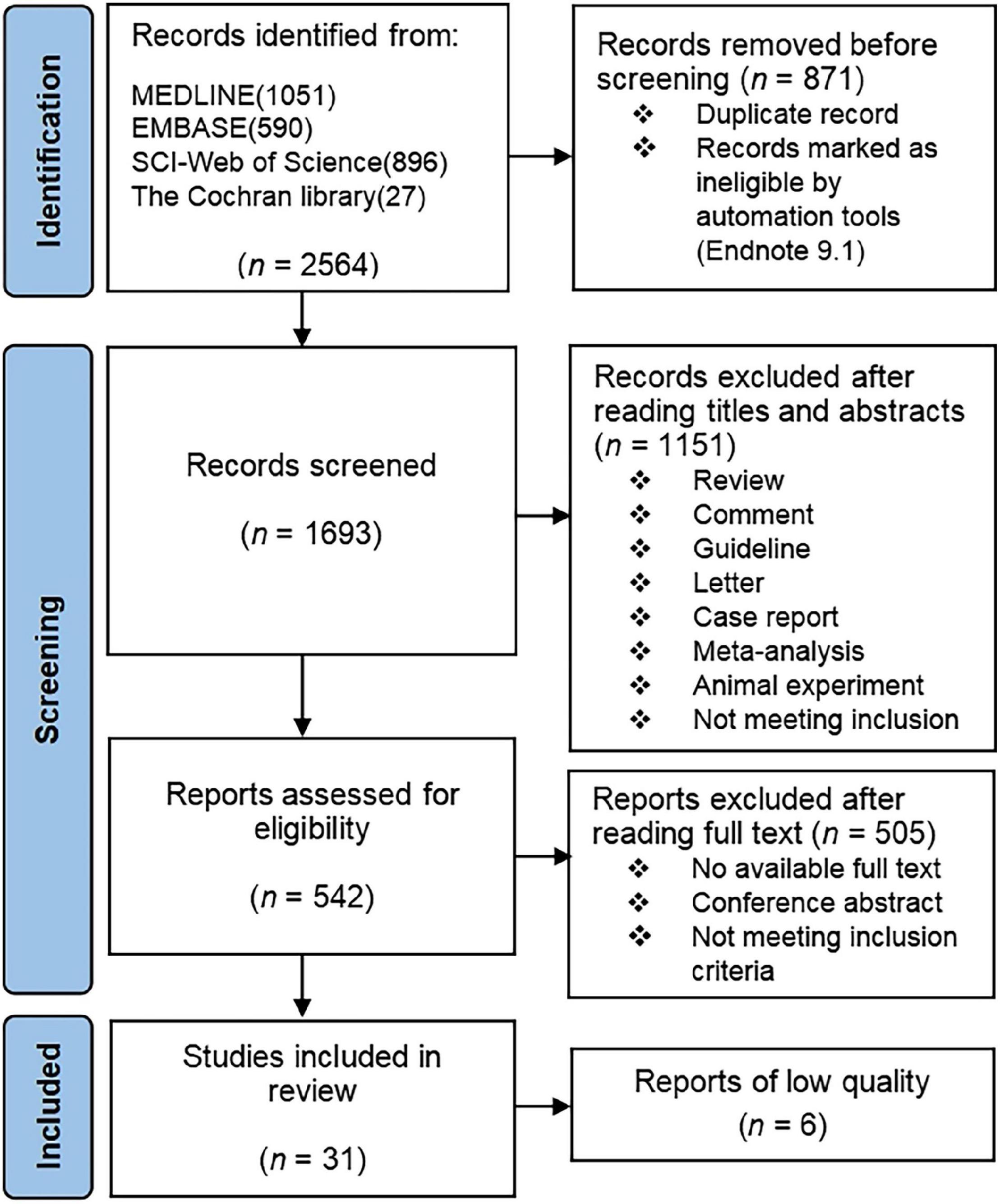

In our study, the exposure factor was psoriasis, and the outcome was adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, we used psoriasis patients as the exposure group and non-psoriatic subjects as the control group. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as a guideline for our study and mapped the PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Source and Search

The searches were performed in collaboration with an informatics specialist in four electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCI–Web of science and the Cochrane Library) for all relevant studies on psoriasis and adverse cardiovascular outcome published before January 2022. The records were screened by two reviewers independently using Endnote 9.1.

Our retrieval strategy consisted of three modules, each of which was required to contain at least one of the following terms: “psoriasis” OR “Psoriases” OR “Pustulosis of Palms and Soles” OR “Pustulosis Palmaris et Plantaris” OR “Palmoplantaris Pustulosis” OR “Pustular Psoriasis of Palms and Soles”; “cardiovascular diseases” OR “Cardiovascular Disease” OR “Disease, Cardiovascular” OR “Diseases, Cardiovascular”; “risk” OR “mortality” OR “mortality” OR “cohort”. Supplementary Table 1 summarized the specific retrieval strategies and results used for each database.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Cohort studies about the relationship between psoriasis and cardiovascular outcome in adults (≥ 18 years old); psoriasis patients that were diagnosed in regular hospitals or had records in other medical and health institutions; the outcome indicator of the study was hazard ratio (HR) or rate ratio (RR). It has been shown that the practical meaning of HR and RR are very similar, so we converted HR directly to RR for merging and the final effect size is represented by RR (16).

Exclusion Criteria

Summaries, systematic reviews, conference abstract and studies with inappropriate control groups or lacking primary data were excluded. For research that lack original data, we contacted the author twice via email. Invalid email addresses or failure to receive a response would result in the exclusion of the research from the study. If there was more than one control group of psoriasis patients in the study, the most appropriate group was selected as the control group. If there were duplicates in the study, we selected only data that were more homogeneous with other studies.

Definition of “Exposure” and “Outcome”

In our study, CVD included ischemic heart disease, aortic valve stenosis and atherosclerosis. CVE were defined as conditions such as cardiovascular death, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, arrhythmia, venous thromboembolism, aneurysm, stroke and transient ischemic attack. All of the above diseases served as the outcome events observed in this study.

Psoriasis was divided into three categories according to severity, namely, mild, moderate, and severe. “Mild” was defined as patients requiring only topical treatment, whereas “moderate” and “severe”, which were combined into one group, were patients requiring systemic treatment as well as those with psoriatic arthritis.

The diagnosis of all diseases must be based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or other authoritative diagnostic basis.

Data Extraction

The following information was obtained from each article: author, journal, year of publication, country of origin, selection and characteristics of psoriasis patients and non-psoriatic subjects, demographics, ethnicity, HR (or RR), and 95% confidence interval (CI). For subjects of different ethnicities, data were extracted separately and categorized as European and Asian. For articles in non-English languages, we translated them using Zhiyun translator (V7.0).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the STATA statistics software V16.0 and Review manager V5.3 using random-effects model.

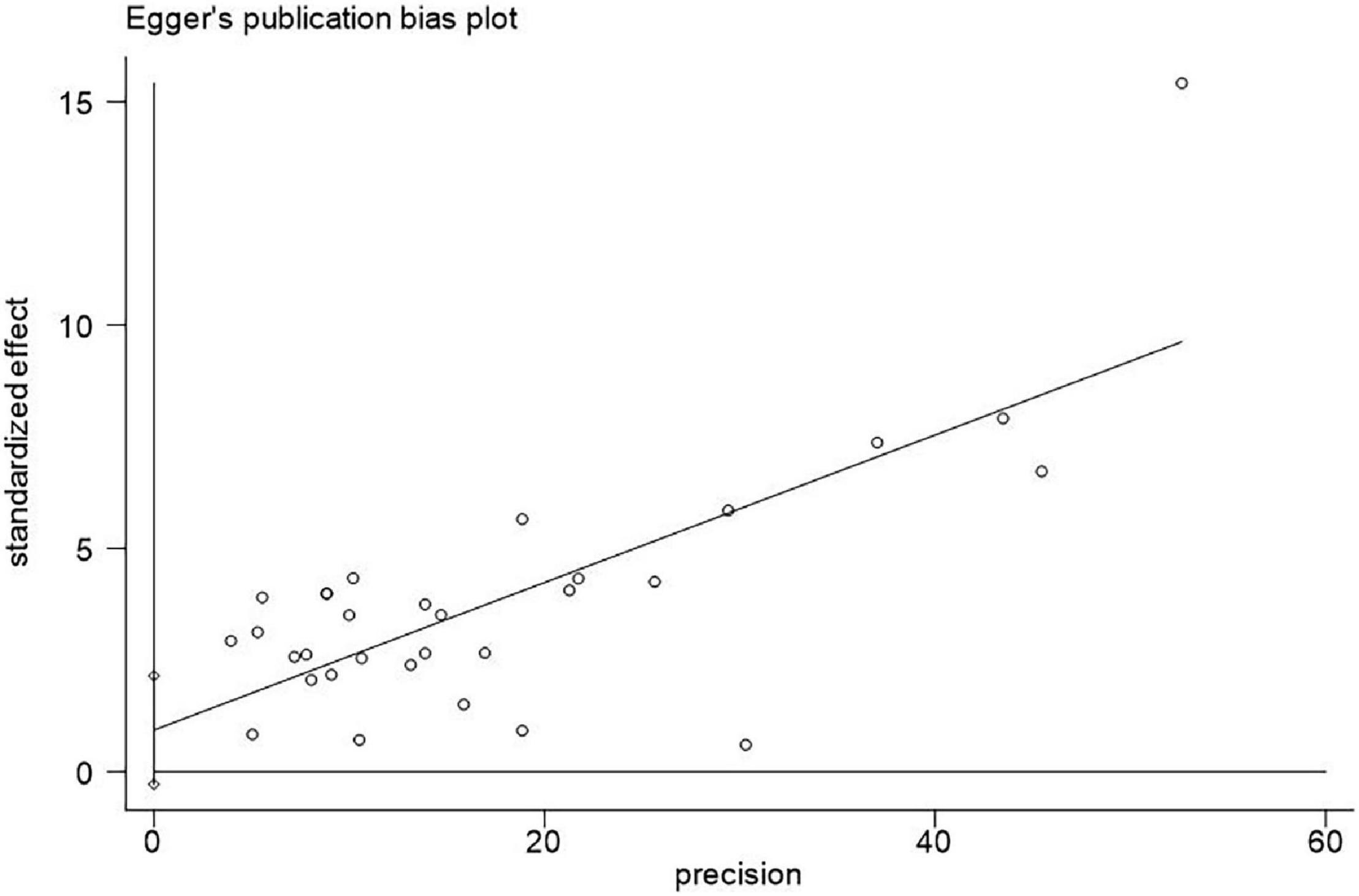

First, we tested for publication bias by funnel plots of Egger’s test and Begg’s test. If the P-value of the tests was less than 0.1, there was publication bias. In addition, the Egger’s test is usually considered more sensitive than the Begg’s test (17). We chose the result of Egger’s test if they were inconsistent.

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS, range 0--9)1 was used to assess the quality of each study. A score > 6 was regarded as high quality. Studies with a score ≤ 6 will be excluded.

Statistical heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 statistic (9), which was interpreted as follows: 25–75%, moderate heterogeneity; > 75%, substantial heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted to ensure the stability of the results. To effectively detect heterogeneity, we used a more conservative random-effects model (18).

In addition to comparisons of total number of subjects, we also classified the studies according to the ethnicity, severity of psoriasis, and cardiovascular outcomes for different analyses (if a particular group was included in only one or two published studies, it would be classified into the “Other” group for convenience). If a study contains data of two outcomes, it will be included in analyses for each outcome separately. For each group, we evaluated heterogeneity among studies using the χ2-based Q-test (19), and the heterogeneity was significant if P < 0.05.

To ensure that patients with psoriasis and no psoriasis were not counted several times, we selected data with the largest number of participants if a medical database was used by multiple studies in adjacent time periods and the number of psoriasis patients were similar.

Ethics Approval Statement

Institutional review board approval was not required, given that the analysis was based on unidentified secondary data from previously published studies.

Results

Literature Search

We found 2,564 eligible references in four databases; 2,533 references were excluded upon screening. The screening process is presented in Figure 1, and Table 1 summarized the characteristics of the 31 included studies. A total of 31 studies involving 665,009 psoriasis patients and 17,902,757 non-psoriatic control subjects were included in the meta-analysis (4, 12, 13, 20–47). The number of participants in studies with population duplication was not counted. Six low-quality articles were excluded (11, 48–52). Of the 31 studies, 9 were retrospective cohort studies, while the others were prospective. The mean follow-up time for the included studies was 7.1 years. Several studies had collected more than one observed outcome. Three relevant studies were excluded due to no access to full texts (53–55).

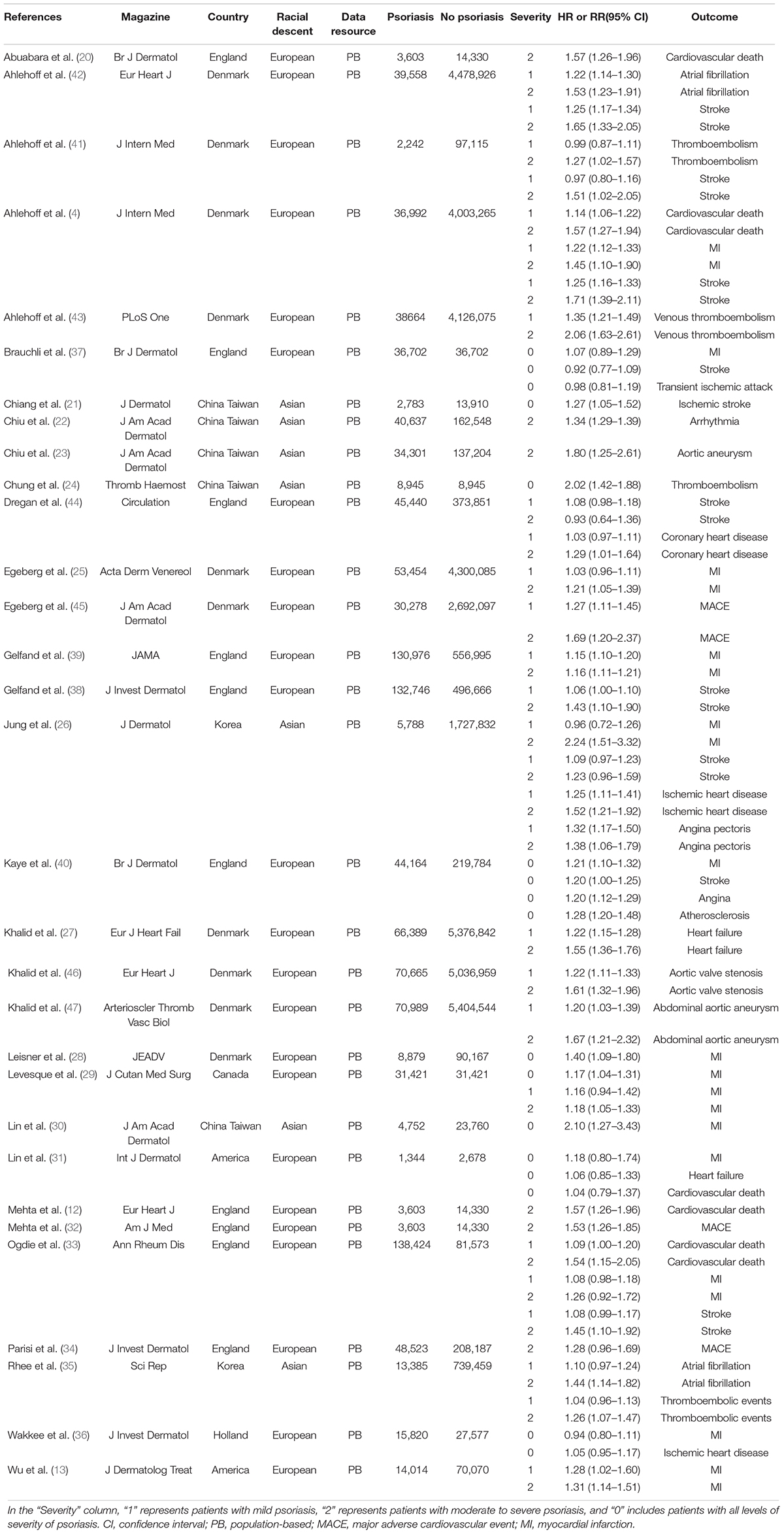

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies investigated the association between psoriasis and cardiovascular diseases/events risk.

Quality Assessment

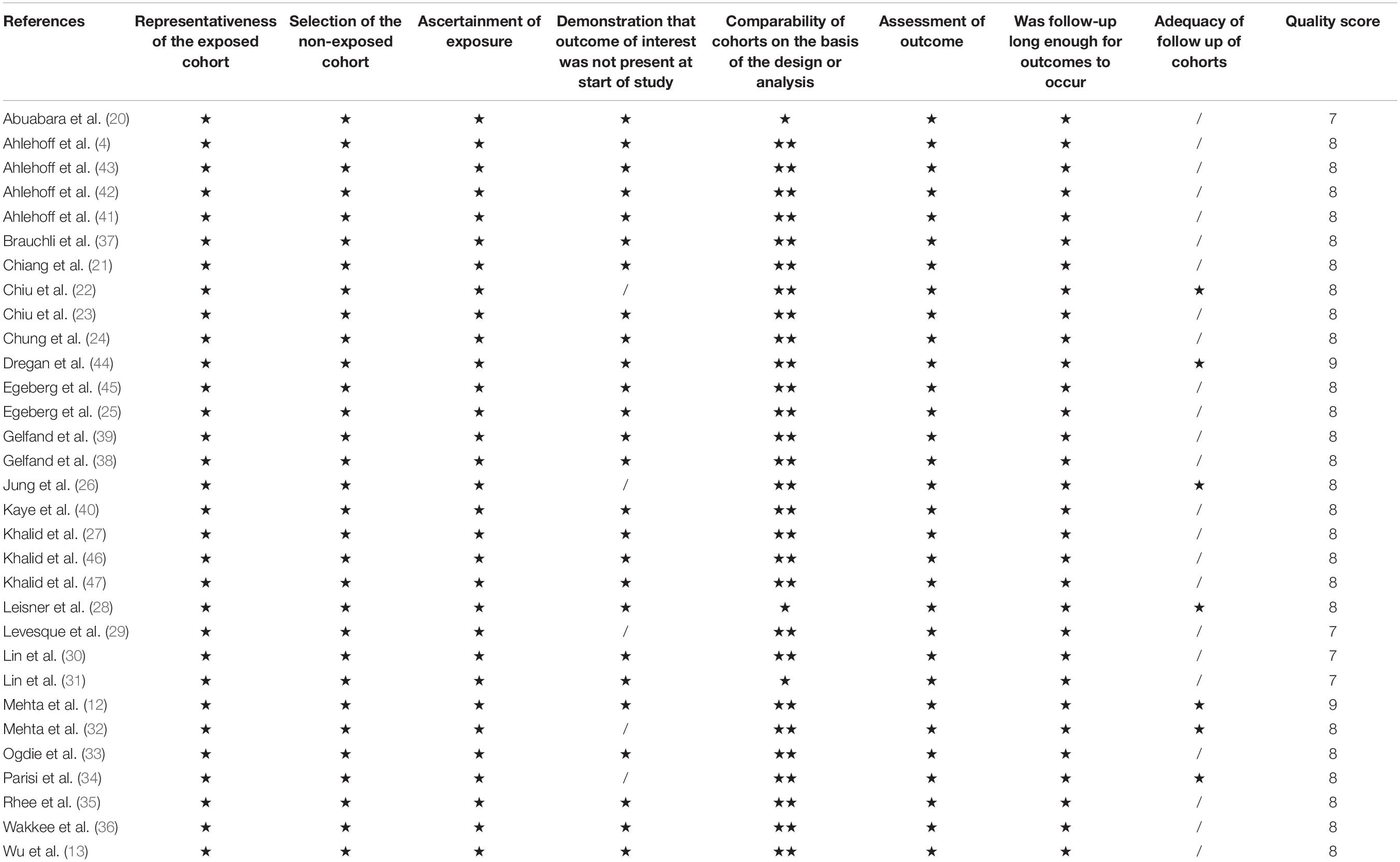

We conducted quality assessment of the 31 studies based on the NOS. The scores for these studies ranged from 7 to 9, and the mean of the quality scores was 7.94 (standard deviation ± 0.44). Table 2 summarized the specific items of NOS tool for each included study.

Table 2. The quality assessment of 31 included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (range 0–9).

Publication Bias

We visually examined the funnel plot of the 31 articles and concluded that it was symmetrical (presented in Figure 2). Begg’s test showed a significant publication bias among these studies (P = 0.003). However, Egger’s test revealed that there was no obvious publication bias (P = 0.125). The Egger’s test was used in the present study since it is usually considered more sensitive than the Begg’s test (17).

Figure 2. Egger’s test for publication bias of 31 included articles for adverse cardiovascular outcomes (P = 0.125).

Pooled Analysis

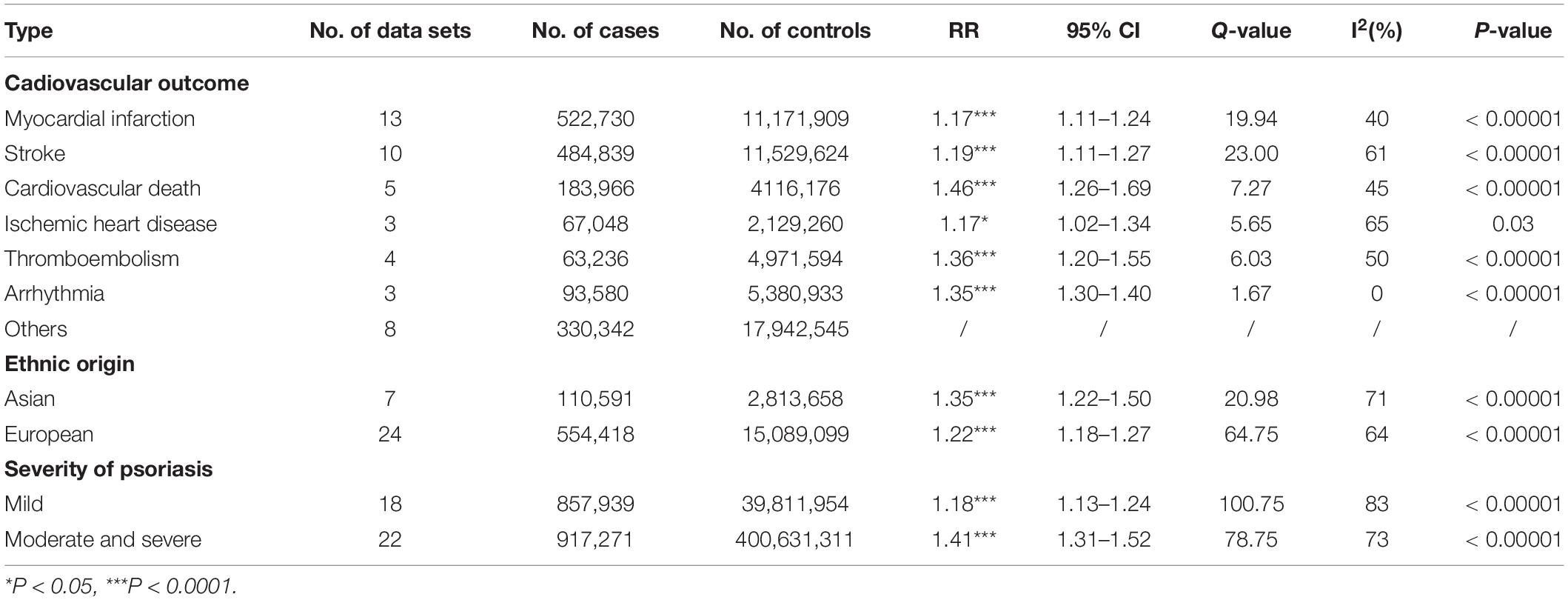

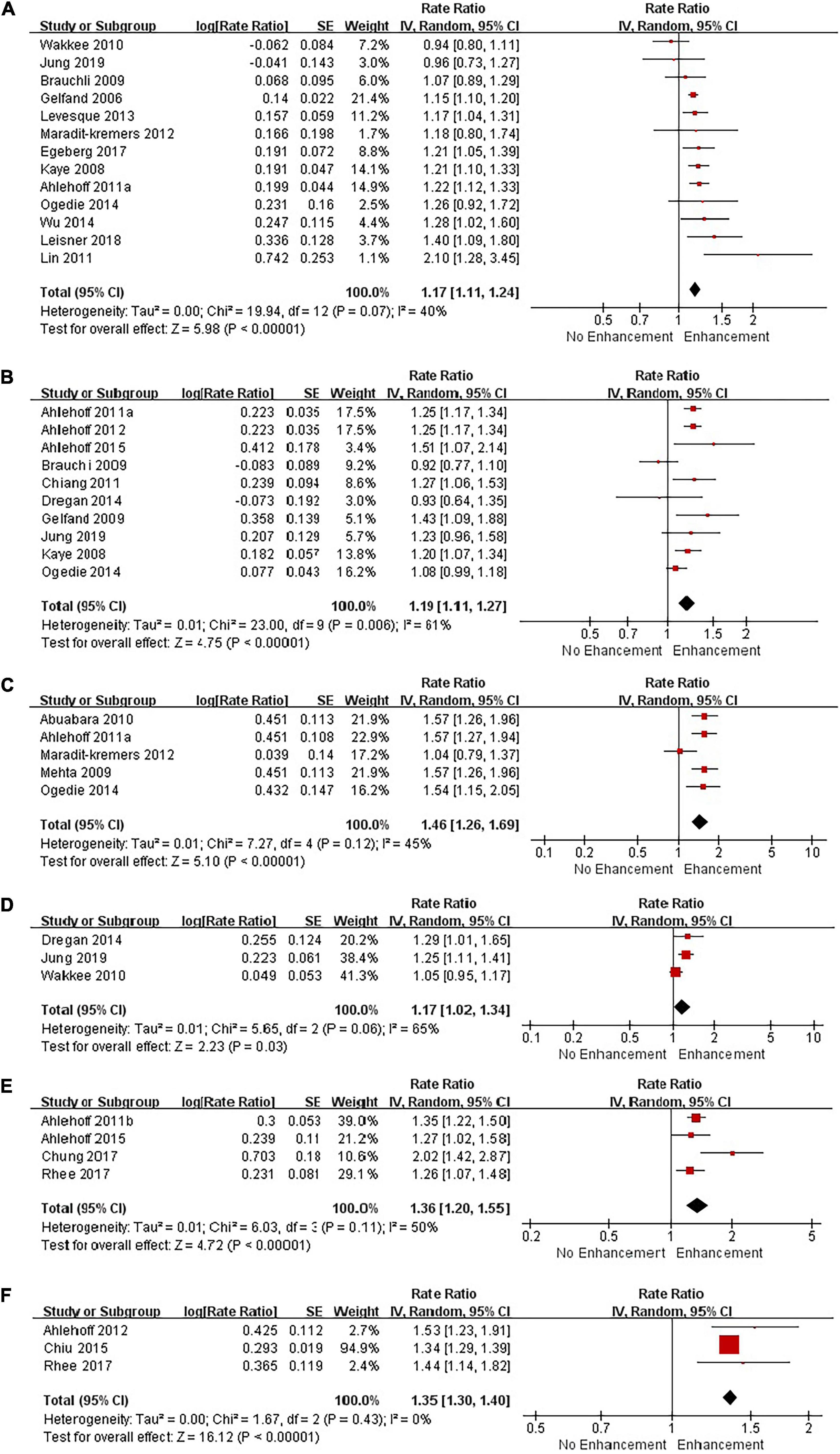

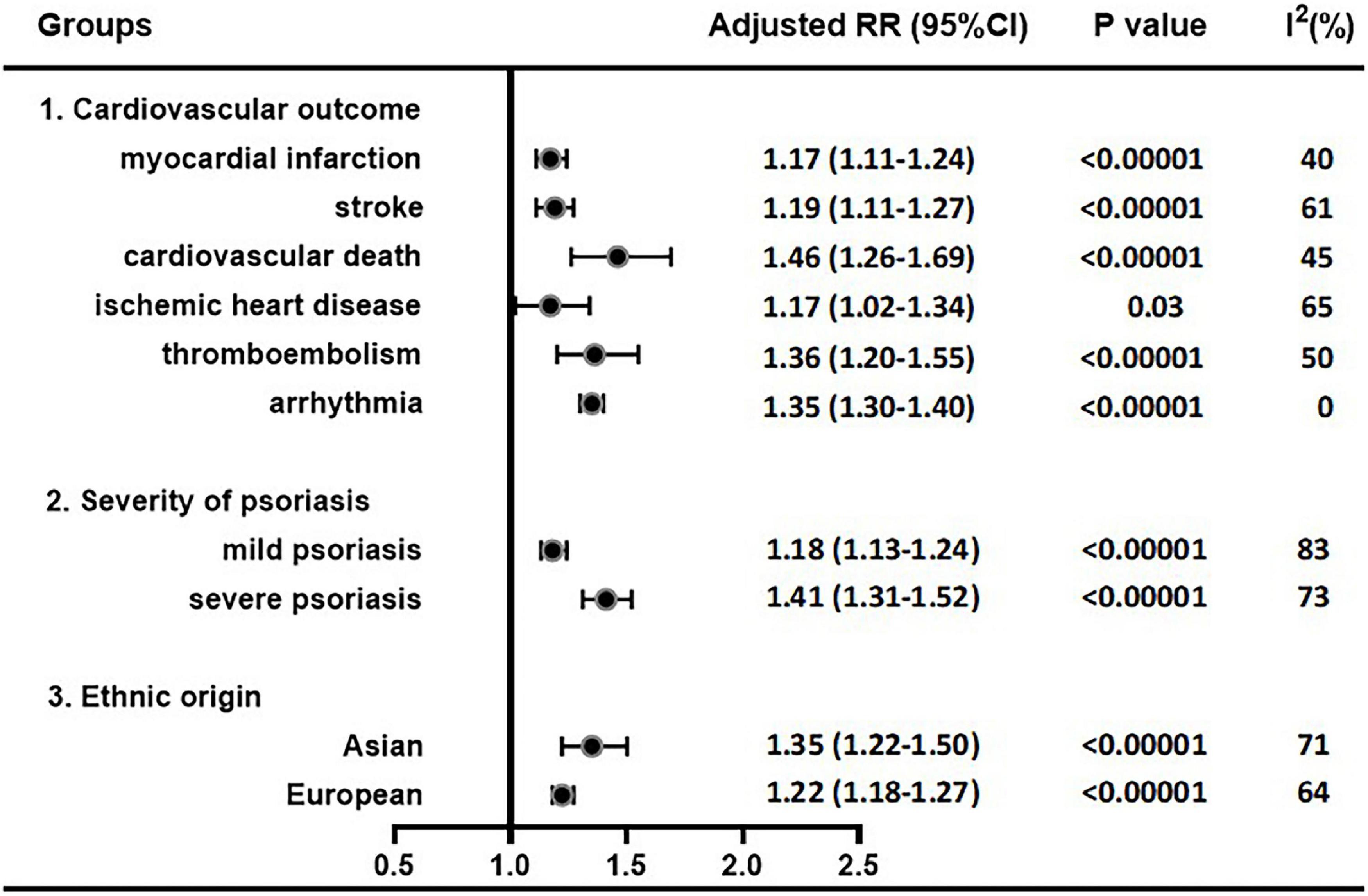

We performed combined analysis in terms of each cardiovascular outcome, ethnic origin, and severity of psoriasis. Table 3 presents a summary of RR estimates, corresponding 95% CI, Q-test, and I2 estimates for each analysis (presented in Figures 3, 4).

Table 3. Estimates of RRs and the 95% CIs for adverse cardiovascular disease and heterogeneity test for studies with Cochran’s Q-test and the quantity I2.

Figure 3. Forest plot of adverse cardiovascular outcomes based on Review Manager. (A) Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis; (B) risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis; (C) risk of cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis; (D) risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with psoriasis; (E) risk of thromboembolism in patients with psoriasis; (F) risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis.

Figure 4. Pooled adjusted RR estimates in each cardiovascular outcome, psoriasis severity and ethnic origin.

Pooled Analysis of Main Cardiovascular Outcomes

Myocardial Infarction

Thirteen studies investigated the risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis, including 522,730 patients and 11,171,909 non-psoriatic control subjects. Our meta-analysis with random-effects model showed a moderately increased risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis (1.17; 95% CI 1.11–1.24). Heterogeneity test showed no significant difference among these studies (Q = 19.94 with 12 df, P = 0.07; I2 = 40%). Therefore, our meta-analysis showed that psoriasis was a related risk factor for myocardial infarction.

Stroke

Ten studies investigated the risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis, including 484,839 psoriasis patients and 11,529,624 non-psoriatic control subjects. Our meta-analysis showed a significant association of psoriasis with stroke (1.19; 95% CI 1.11–1.27). Heterogeneity test showed a difference among these studies (Q = 23.0 with 9 df, P = 0.006; I2 = 61%). Sensitivity analysis showed that statistical heterogeneity can be effectively removed (Q = 13.87 with 8 df, P = 0.09; I2 = 42%) when the data sets of a study (37) were excluded, and the result was consistent with the previous trend. Our meta-analysis showed that psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of stroke.

Cardiovascular Death

Five studies investigated the risk of cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis in Europeans, including 183,966 psoriasis patients and 4,116,176 non-psoriatic control subjects. Heterogeneity test demonstrated that there was no heterogeneity among these studies (Q = 7.27 with 4 df, P = 0.12; I2 = 45%). Our meta-analysis with random-effects model showed a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis (1.46; 95% CI 1.26–1.69). Thus, our meta-analysis result showed that psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death.

Ischemic Heart Disease

Three studies investigated the risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with psoriasis in Europeans, including 67,048 psoriasis patients and 2,129,260 non-psoriatic control subjects. The pooled RR estimate was 1.17 (95% CI 1.02–1.34). There was no significant heterogeneity when these data sets were analyzed together (Q = 5.65 with 2 df, P = 0.06; I2 = 65%), which showed psoriasis patients had a higher risk of ischemic heart disease.

Thromboembolism

Four studies investigated the risk of thromboembolism in patients with psoriasis, including 63,236 psoriasis patients and 4,971,594 non-psoriatic control subjects. The pooled RR estimate was 1.36 (95% CI 1.20–1.55). Heterogeneity tests showed no difference among these studies (Q = 6.03 with 3 df, P = 0.11; I2 = 50%). Our meta-analysis result showed that patients with psoriasis had a higher risk of thromboembolism.

Arrhythmia

Three studies investigated the risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis, including 93,580 psoriasis patients and 5,380,933 non-psoriatic control subjects. The pooled RR estimate was 1.35 (95% CI 1.30–1.40). There was no significant heterogeneity when these data sets were analyzed together (Q = 1.67 with 2 df, P = 0.43; I2 = 0%), which showed psoriasis patients had a higher risk of arrhythmia.

Others

Eight studies involving 330,342 psoriasis patients and 17,942,545 non-psoriatic control subjects had addressed the risk of other adverse cardiovascular outcomes in psoriasis patients, including heart failure, angina, aortic aneurysm, aortic valve stenosis, atherosclerosis and transient ischemic attack. The pooled analysis of these outcomes was not performed since the studies were insufficient and the results were poorly represented.

Pooled Analysis in Terms of Ethnic Origin

Seven studies investigated the risk of CVD or CVE in Asian patients with psoriasis, including 110,591 psoriasis patients and 2,813,658 non-psoriatic control subjects; twenty-four studies in European patients, including 554,418 psoriasis patients and 15,089,099 non-psoriatic subjects. We found increased adverse cardiovascular outcomes risks in European (1.22; 95% CI, 1.18–1.27) and Asian (1.35; 95% CI, 1.22–1.50) groups, but there was no significant difference between two groups (P = 0.076). After eliminating heterogeneity, the combined RR estimates for the Asian and European groups were 1.33 (95% CI, 1.29–1.38) and 1.24 (95% CI, 1.20–1.28), respectively.

Pooled Analyses in Terms of Severity of Psoriasis

Eighteen studies detected the risk of CVD or CVE in patients with mild psoriasis, involving 857,939 psoriasis patients and 39,811,954 non-psoriatic subjects; 22 studies involving 917,271 psoriasis patients and 40,063,131 non-psoriatic subjects detected in moderate and severe psoriasis patients. Our results revealed a significantly increased risk in both mild (1.18; 95% CI 1.13–1.24) and moderate-to-severe patients (1.41; 95% CI 1.31–1.52), with a higher RR in moderate-to-severe patients (P = 0.001). The result of heterogeneity test showed significant differences among these studies. After eliminating heterogeneity, the combined RR estimates were 1.20 (95% CI, 1.16–1.24) for mild psoriasis and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.33–1.50) for moderate and severe psoriasis.

Certainty of Evidence Assessment

Evidence assessment was performed using GRADE profiler, and grades of cohort studies were all slightly lower than randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, we believe cohort studies provided the highest level of evidence for the meta-analysis conducted in the present study based on the following considerations. (1) The present systematic review included 31 high-quality cohort studies according to the NOS scale, and all low-quality studies had been excluded. (2) RCT was not applicable to the etiological research of CVDs due to ethical constraints.

Discussion

This research was a large-scale cohort meta-analysis of the correlation between psoriasis and CVD that included 31 cohort studies involving 665,009 psoriasis patients and 17,902,757 non-psoriatic control subjects. Our meta-analysis revealed that psoriasis patients had significantly increased the risk for developing adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Patients with psoriasis, especially severe psoriasis, had a higher risk of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, thromboembolism, arrhythmia and cardiovascular death.

Samarasekera et al. conducted a meta-analysis (15) included 14 cohort studies, 7 of them met our inclusion criteria and were included in our meta-analysis. The results of their analysis indicated that the risk of CVD was significantly related to severe psoriasis (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.26–1.96), which was consistent with our findings. We found that cardiovascular morbidity was also significantly increased in patients with mild psoriasis compared with non-psoriatic subjects, which was not observed in their study. Another published meta-analysis (14) that included 75 observational studies (38 cross-sectional studies, 32 case–control studies, and 5 cohort studies) arrived at a similar conclusion with us only in case–control studies.

According to the World Health Organization, CVD is a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels, including coronary artery disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, etc.), peripheral arterial disease (stroke), rheumatic heart disease, and congenital heart disease. Traditional risk factors for CVD include hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, obesity, diabetes etc. (56). To recognize the role of psoriasis for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, it was necessary to adjust for the influence of as many known traditional factors as possible. In our study, 27 of the included studies had adjusted CVD traditional factors, although the type and number of factors varied from study to study, which included age, gender, socioeconomic status, prior CVD, current smoking, body mass index, total cholesterol etc. Thus, our conclusions had a high degree of credibility.

At present, there are a number of clinical options for the treatment of psoriasis, including TNF-α inhibitors, oral/phototherapy, systematic treatment with traditional medicine, and topical treatments (57–61). Different treatment modalities may affect the cardiovascular risk of patients with psoriasis. A study demonstrated that treatment of psoriasis with TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, or adalimumab) significantly reduced the risk and incidence of myocardial infarction compared with treatment with topical medication. Also, treatment of psoriasis with TNF inhibitors had no significant difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction compared with treatment with oral medications (i.e., cyclosporine, acitretin, and methotrexate)/phototherapy (59). In a national study of patients with severe psoriasis (57), it was shown that systemic anti-inflammatory therapy with biologics (TNF-α inhibitors and interleukin inhibitors) or methotrexate significantly reduced the incidence of CVD compared with patients treated with other anti-psoriatic therapies. Interestingly, two published meta-analyses of 22 and 38 RCTs concluded that there was no significant difference in the incidence of major adverse CVE between biologically treated patients and placebo patients (62, 63). Due to the lack of optimal random-effects modeling methods, the poor data quality, and the short control periods of the experiment, their conclusions had subsequently been questioned, and even the authors themselves share this concern (61). Therefore, different treatment modalities are likely to alter the cardiovascular risk of patients with psoriasis. The lack of data on the treatment of patients with psoriasis in our included studies may be a reason for the heterogeneity.

This research also has several limitations. Above all, the association between psoriasis and ischemic heart disease may be greatly underestimated. As for ischemic heart disease, all three studies included in our meta-analysis used ICD to identify the disease, but in silent ischemic cases, it could only be detected by coronary angiography (CAG) or CT angiography (CTA). Given that it’s unknown whether all subjects received CAG or CTA on a regular basis, some cases of ischemic heart disease may remain undetected, resulting in significant underestimation of the true relationship between psoriasis and ischemic heart disease. Furthermore, our results indicated that the strongest association occurred in the cardiovascular mortality group. However, we found that four of the five included studies were of severe psoriasis patients, which may have led to an overestimation of the risk of cardiovascular mortality from psoriasis. These limitations may be sources for heterogeneity.

Nonetheless, our meta-analysis holds some key strengths in several aspects. Firstly, due to ethical constraints, cohort studies are the most appropriate research method for comorbidity studies. Therefore, the highest level of evidence was provided in the present systematic review of cohort studies. Secondly, large numbers of psoriasis patients and non-psoriatic subjects were pooled from 31 included studies, which significantly improved the statistical power of the analysis. Thirdly, according to the NOS scale, the quality of cohort studies included in the present study was high (≥ 7 points). Fourthly, we performed a more comprehensive analysis and further confirmed that psoriasis was associated with multiple adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

We recommend that clinicians, while treating patients with psoriasis, pay more attention to the cardiovascular risk of patients. First, we call on doctors or communities to educate people at a high risk for CVD on prevention so people can care for their health. In a way, the guidelines for cardiovascular prevention may also be valid for psoriasis patients. This is an enhanced primary prevention of CVD, which is a guideline to reduce the incidence of CVD in patients with psoriasis. An RCT of 303 cases revealed that a 20-week dietetic intervention associated with increased physical exercise reduced psoriasis severity in systemically treated overweight or obese patients with active psoriasis (64). Meanwhile, several studies had found that exercise not only reduces the risk of psoriasis, but also promotes cardiovascular health (65, 66). Exercise avoidance in patients with psoriasis can lead to an increased risk of CVD (67). Second, regular stress-testing to monitor the presence of coronary artery disease may be a useful screening for psoriasis patients.

Conclusion

Overall, our meta-analysis found that psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of all pooled observed adverse cardiovascular outcomes regardless of ethnic origin or severity, including myocardial infarction, stroke, thromboembolism, arrhythmia and cardiovascular death. This association was even stronger in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. This suggested that psoriasis may be an independent risk factor for all adverse CVE, which requires more attention from clinicians.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

GZ and NW: supervision, concept, and design. GZ, NW, XH, and LL: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. LL and SC: drafting of the manuscript. LL and ML: statistical analysis. All authors critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Lee Min-Geol for his data support. In addition, there was no collaboration with anyone other than the named authors, and no one else provided any of the data included in this meta-analysis. We are grateful to Enago for English polishing service.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.829709/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Mahil SK, Smith CH. Psoriasis biologics: a new era of choice. Lancet. (2019) 394:807–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31772-6

2. Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. (2021) 397:1301–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6

3. Guo F, Yu Q, Liu Z, Zhang C, Li P, Xu Y, et al. Evaluation of life quality, anxiety, and depression in patients with skin diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e22983. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022983

4. Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, Jorgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. (2011) 270:147–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x

5. Alexandroff AB, Pauriah M, Camp RD, Lang CC, Struthers AD, Armstrong DJ. More than skin deep: atherosclerosis as a systemic manifestation of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (2009) 161:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09281.x

6. Lau WB, Ohashi K, Wang Y, Ogawa H, Murohara T, Ma XL, et al. Role of Adipokines in cardiovascular disease. Circ J. (2017) 81:920–8. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0458

7. Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2013) 309:71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905

8. Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. (2016) 118:1752–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306883

9. Huang Y, Wang S, Cai X, Mai W, Hu Y, Tang H, et al. Prehypertension and incidence of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. (2013) 11:177. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-177

11. Dowlatshahi EA, Kavousi M, Nijsten T, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Psoriasis is not associated with atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events: the Rotterdam study. J Invest Dermatol. (2013) 133:2347–54. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.131

12. Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the general practice research database. Eur Heart J. (2010) 31:1000–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp567

13. Wu JJ, Choi YM, Bebchuk JD. Risk of myocardial infarction in psoriasis patients: a retrospective cohort study. J Dermatolog Treat. (2015) 26:230–4. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.952609

14. Miller IM, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, Jemec GB. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2013) 69:1014–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053

15. Samarasekera EJ, Neilson JM, Warren RB, Parnham J, Smith CH. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. (2013) 133:2340–6. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.149

16. Dahabreh IJ, Sheldrick RC, Paulus JK, Chung M, Varvarigou V, Jafri H, et al. Do observational studies using propensity score methods agree with randomized trials? A systematic comparison of studies on acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33:1893–901. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs114

17. Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in met a-analysis. BMJ. (2001) 323:101–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101

18. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446

19. Wang N, Zhou R, Wang C, Guo X, Chen Z, Yang S, et al. -251 T/A polymorphism of the interleukin-8 gene and cancer risk: a HuGE review and meta-analysis based on 42 case-control studies. Mol Biol Rep. (2012) 39:2831–41. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1042-5

20. Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the U.K. Br J Dermatol. (2010) 163:586–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09941.x

21. Chiang CH, Huang CC, Chan WL, Huang PH, Chen YC, Chen TJ, et al. Psoriasis and increased risk of ischemic stroke in Taiwan: a nationwide study. J Dermatol. (2012) 39:279–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01401.x

22. Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, Wen YW, Tsai YW, Tsai TF. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2015) 73:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.023

23. Chiu HY, Lo PC, Huang WF, Tsai YW, Tsai TF. Increased risk of aortic aneurysm (AA) in relation to the severity of psoriasis: a national population-based matched-cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2016) 75:747–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.002

24. Chung WS, Lin CL. Increased risks of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriasis. A nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. (2017) 117:1637–43. doi: 10.1160/TH17-01-0039

25. Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Jensen P, Gislason GH, Skov L. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. (2017) 97:819–24. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2657

26. Jung KJ, Kim TG, Lee JW, Lee M, Oh J, Lee SE, et al. Increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among patients with psoriasis in Korea: a 15-year nationwide population-based cohort study. J Dermatol. (2019) 46:859–66. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15052

27. Khalid U, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Kristensen SL, Skov L, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Psoriasis and risk of heart failure: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. (2014) 16:743–8. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.113

28. Leisner MZ, Lindorff Riis J, Gniadecki R, Iversen L, Olsen M. Psoriasis and risk of myocardial infarction before and during an era with biological therapy: a population-based follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2018) 32:2185–90. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15021

29. Levesque A, Lachaine J, Bissonnette R. Risk of myocardial infarction in canadian patients with psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Cutan Med Surg. (2013) 17:398–403. doi: 10.2310/7750.2013.13052

30. Lin HW, Wang KH, Lin HC, Lin HC. Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis: a 5-year population-based study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2011) 64:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.050

31. Maradit-Kremers H, Dierkhising RA, Crowson CS, Icen M, Ernste FC, McEvoy MT. Risk and predictors of cardiovascular disease in psoriasis: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. (2013) 52:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05430.x

32. Mehta NN, Yu Y, Pinnelas R, Krishnamoorthy P, Shin DB, Troxel AB, et al. Attributable risk estimate of severe psoriasis on major cardiovascular events. Am J Med. (2011) 124:775.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.03.028

33. Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, Love TJ, Maliha S, Jiang Y, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2015) 74:326–32. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205675

34. Parisi R, Rutter MK, Lunt M, Young HS, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of major cardiovascular events: cohort study using the clinical practice research datalink. J Invest Dermatol. (2015) 135:2189–97. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.87

35. Rhee TM, Lee JH, Choi EK, Han KD, Lee H, Park CS, et al. Increased risk of atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism in patients with severe psoriasis: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:9973. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10556-y

36. Wakkee M, Herings RM, Nijsten T. Psoriasis may not be an independent risk factor for acute ischemic heart disease hospitalizations: results of a large population-based Dutch cohort. J Invest Dermatol. (2010) 130:962–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.321

37. Brauchli YB, Jick SS, Miret M, Meier CR. Psoriasis and risk of incident myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischaemic attack: an inception cohort study with a nested case-control analysis. Br J Dermatol. (2009) 160:1048–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09020.x

38. Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, Azfar RS, Kurd SK, Wang X, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. (2009) 129:2411–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.112

39. Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. (2006) 296:1735–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735

40. Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (2008) 159:895–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08707.x

41. Ahlehoff O, Gislason G, Lamberts M, Folke F, Lindhardsen J, Larsen CT, et al. Risk of thromboembolism and fatal stroke in patients with psoriasis and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. (2015) 277:447–55. doi: 10.1111/joim.12272

42. Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jorgensen CH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot M, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33:2054–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr285

43. Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Lindhardsen J, Charlot MG, Jorgensen CH, Olesen JB, et al. Psoriasis carries an increased risk of venous thromboembolism: a Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e18125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018125

44. Dregan A, Charlton J, Chowienczyk P, Gulliford MC. Chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and stroke: a population-based cohort study. Circulation. (2014) 130:837–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009990

45. Egeberg A, Bruun LE, Mallbris L, Gislason GH, Skov L, Wu JJ, et al. Family history predicts major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in young adults with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2016) 75:340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1227

46. Khalid U, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Skov L, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen PR. Increased risk of aortic valve stenosis in patients with psoriasis: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:2177–83. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv185

47. Khalid U, Egeberg A, Ahlehoff O, Smedegaard L, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Nationwide study on the risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with psoriasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2016) 36:1043–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307449

48. Gladman DD, Ang M, Su L, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT. Cardiovascular morbidity in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2009) 68:1131–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094839

49. Han C, Robinson DW Jr, Hackett MV, Paramore LC, Fraeman KH, Bala MV. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. (2006) 33:2167–72.

50. Li WQ, Han JL, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Rexrode KM, Curhan GC, et al. Psoriasis and risk of nonfatal cardiovascular disease in U.S. women: a cohort study. Br J Dermatol. (2012) 166:811–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10774.x

51. McDonald CJ, Calabresi P. Psoriasis and occlusive vascular disease. Br J Dermatol. (1978) 99:469–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb02012.x

52. No DJ, Amin M, Duan L, Egeberg A, Ahlehoff O, Wu JJ. Risk of aortic aneurysm in patients with psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2018) 32:e54–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14496

53. Solovãstru GL, Vâţă D, Batog AH, Siriac O, Alupoaiei A, Diaconu D. [Comorbidities in psoriatic patients of iaşi dermatological clinic from 2004-2008]. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. (2009) 113:751–6.

54. Ena P, Madeddu P, Glorioso N, Cerimele D, Rappelli A. High prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and enhanced activity of the renin-angiotensin system in psoriatic patients. Acta Cardiol. (1985) 40:199–205.

55. Török L, Tóth E, Bruncsák A. [Correlation between psoriasis and cardiovascular diseases (author’s transl)]. Z Hautkr. (1982) 57:734–9.

56. Ma LY, Chen WW, Gao RL, Liu LS, Zhu ML, Wang YJ, et al. China cardiovascular diseases report 2018: an updated summary. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2020) 17:1–8. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.01.001

57. Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, Lindhardsen J, Kristensen SL, Iversen L, et al. Cardiovascular disease event rates in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs: a Danish real-world cohort study. J Intern Med. (2013) 273:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02593.x

58. Haycraft K, Cooke L. Rapid and sustained improvement in a patient with plaque psoriasis switched to brodalumab after failing treatment clearance on six other biologic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. (2020) 19:86–8. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.4583

59. Wu JJ, Poon KY, Channual JC, Shen AY. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. (2012) 148:1244–50. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2502

60. Polistena B, Calzavara-Pinton P, Altomare G, Berardesca E, Girolomoni G, Martini P, et al. The impact of biologic therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis from a societal perspective: an analysis based on Italian actual clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2015) 29:2411–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13307

61. Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A, Toulis K. Biologic therapies for chronic plaque psoriasis and cardiovascular events. JAMA. (2011) 306:2095. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1660

62. Ryan C, Leonardi CL, Krueger JG, Kimball AB, Strober BE, Gordon KB, et al. Association between biologic therapies for chronic plaque psoriasis and cardiovascular events: a meta -analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. (2011) 306:864–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1211

63. Rungapiromnan W, Yiu ZZN, Warren RB, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Impact of biologic therapies on risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with psoriasis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. (2017) 176:890–901. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14964

64. Naldi L, Conti A, Cazzaniga S, Patrizi A, Pazzaglia M, Lanzoni A, et al. Diet and physical exercise in psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. (2014) 170:634–42. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12735

65. Balato N, Megna M, Palmisano F, Patruno C, Napolitano M, Scalvenzi M, et al. Psoriasis and sport: a new ally? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2015) 29:515–20. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12607

66. Auker L, Cordingley L, Griffiths CEM, Young HS. Physical activity is important for cardiovascular health and cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2021) 47:289–96. doi: 10.1111/ced.14872

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, cohort study, meta-analysis, systematic review, psoriasis

Citation: Liu L, Cui S, Liu M, Huo X, Zhang G and Wang N (2022) Psoriasis Increased the Risk of Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes: A New Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:829709. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.829709

Received: 06 December 2021; Accepted: 02 March 2022;

Published: 25 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ole Ahlehoff, Rigshospitalet, DenmarkReviewed by:

Weiyi Mai, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, ChinaWengen Zhu, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2022 Liu, Cui, Liu, Huo, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Na Wang, aGJ5a2R4d25AMTYzLmNvbQ==; Guoqiang Zhang, emx4MDkwNzAyQDE2My5jb20=

Lu Liu

Lu Liu Saijin Cui

Saijin Cui Meitong Liu

Meitong Liu Xiangran Huo

Xiangran Huo Guoqiang Zhang

Guoqiang Zhang Na Wang

Na Wang