95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 21 December 2022

Sec. Coronary Artery Disease

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1018802

This article is part of the Research Topic Inflammatory Factors in Coronary Heart Disease: Mechanism, diagnosis and therapy View all 12 articles

Jung-Joon Cha1

Jung-Joon Cha1 Soon Jun Hong1*

Soon Jun Hong1* Ju Hyeon Kim1

Ju Hyeon Kim1 Subin Lim1

Subin Lim1 Hyung Joon Joo1

Hyung Joon Joo1 Jae Hyoung Park1

Jae Hyoung Park1 Cheol Woong Yu1

Cheol Woong Yu1 Jeehoon Kang2

Jeehoon Kang2 Hyo-Soo Kim2

Hyo-Soo Kim2 Hyeon-Cheol Gwon3

Hyeon-Cheol Gwon3 Woo Jung Chun4

Woo Jung Chun4 Seung-Ho Hur5

Seung-Ho Hur5 Seung Hwan Han6

Seung Hwan Han6 Seung-Woon Rha7

Seung-Woon Rha7 In-Ho Chae8

In-Ho Chae8 Jin-Ok Jeong9

Jin-Ok Jeong9 Jung Ho Heo10

Jung Ho Heo10 Junghan Yoon11

Junghan Yoon11 Jong-Seon Park12

Jong-Seon Park12 Myeong-Ki Hong13

Myeong-Ki Hong13 Joon-Hyung Doh14

Joon-Hyung Doh14 Kwang Soo Cha15

Kwang Soo Cha15 Doo-Il Kim16

Doo-Il Kim16 Sang Yeub Lee17

Sang Yeub Lee17 Kiyuk Chang18

Kiyuk Chang18 Byung-Hee Hwang19

Byung-Hee Hwang19 So-Yeon Choi20

So-Yeon Choi20 Myung Ho Jeong21

Myung Ho Jeong21 Young Bin Song3

Young Bin Song3 Ki Hong Choi3

Ki Hong Choi3 Chang-Wook Nam5

Chang-Wook Nam5 Bon-Kwon Koo2

Bon-Kwon Koo2 Do-Sun Lim1

Do-Sun Lim1Background: Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a critical risk factor for the pathogenesis and progression of coronary artery disease, with a higher prevalence of complex coronary artery disease, including bifurcation lesions. This study aimed to elucidate the optimal stenting strategy for coronary bifurcation lesions in patients with DM.

Methods: A total of 905 patients with DM and bifurcation lesions treated with second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) from a multicenter retrospective patient cohort were analyzed. The primary outcome was the 5-year incidence of target lesion failure (TLF), which was defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularization.

Results: Among all patients with DM with significant bifurcation lesions, 729 (80.6%) and 176 (19.4%) were treated with one- and two-stent strategies, respectively. TLF incidence differed according to the stenting strategy during the mean follow-up of 42 ± 20 months. Among the stent strategies, T- and V-stents were associated with a higher TLF incidence than one-stent strategy (24.0 vs. 7.3%, p < 0.001), whereas no difference was observed in TLF between the one-stent strategy and crush or culotte technique (7.3 vs. 5.9%, p = 0.645). The T- or V-stent technique was an independent predictor of TLF in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio, 3.592; 95% confidence interval, 2.117–6.095; p < 0.001). Chronic kidney disease, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, and left main bifurcation were independent predictors of TLF in patients with DM.

Conclusion: T- or V-stenting in patients with DM resulted in increased cardiovascular events after second-generation DES implantation.

Clinical trial registration: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03068494?term=03068494&draw=2&rank=1, identifier: NCT03068494.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an independent predictor of long-term death, myocardial infarction, and revascularization in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (1–3). This may be due to impaired endothelial function caused by DM, which promotes a pro-inflammatory vasoconstrictive state and prompts arterial atherothrombosis (4, 5). Thus, newer-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) are recommended for patients with DM undergoing PCI rather than bare-metal stent or early-generation DESs (6). However, despite stent technology and strategy improvements, patients with DM after PCI presented poorer clinical outcomes than patients without DM (7, 8).

A new stent technology achieving high therapeutic drug concentrations in the arterial tissue using a reservoir recently presented better clinical outcomes in patients with DM after PCI (9). These results may lead to identifying DM-specific treatments. However, little is known concerning the optimal stent strategy for complex PCI cases, such as coronary bifurcation diseases associated with atherosclerosis progression and thrombosis due to higher endothelial shear stress, especially in patients with DM (10, 11). In addition, clinical outcomes of stent strategies for coronary bifurcation lesions in patients with DM using second-generation DES have not been fully elucidated.

Thus, this study aimed to investigate the impact of stenting strategies on clinical outcomes in patients with DM and coronary bifurcation lesions using second-generation DES.

This retrospective study cohort was based on the coronary bifurcation stent III registry (NCT03068494) and consisted of 2,648 patients treated between January 2010 and December 2014 in 21 Korean tertiary hospitals. The design and detailed description of the registry have been previously reported (12). The coronary bifurcation stent III registry is a real-world registry of second-generation DES use, and from the registry, patients with DM (N = 905) were included in this study. The inclusion criteria were age >19 years and main vessel (MV) diameter ≥2.5 mm and side branch (SB) diameter ≥2.3 mm, confirmed using core laboratory quantitative coronary angiography analysis. Patients who experienced cardiogenic shock or cardiopulmonary resuscitation during hospitalization, had protected left main disease, or had severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction <30%) were excluded from the registry. The institutional review board of each hospital approved the study protocol, which was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each institutional review board waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Index PCI was performed according to the relevant standard guidelines during each procedure. Before PCI, all patients received loading doses of antiplatelet medications (aspirin 300 mg and P2Y12 inhibitors [clopidogrel 300–600 mg, prasugrel 60 mg, or ticagrelor 180 mg]) unless they had previously received antiplatelet therapy. An activated clotting time of 250–300 s was maintained during PCI using low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin. The PCI strategy, including stent strategy, proximal optimization technique (POT) or re-POT, access site, DES type, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use, and intravascular imaging or invasive physiological assessments, was based on the operator's discretion. In addition, the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy and DM medication was at the operator's discretion.

Patient information, including demographics; medication; and laboratory, angiographic, and procedural data, was collected for analysis through a web-based reporting system. Follow-up clinical outcomes were obtained from electronic medical records of the outpatient clinic. For the quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) analysis, an angiographic core laboratory (Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea) with a validated automated edge-detection system (Centricity CA 1000; GE, Waukesha, WI, USA) reviewed and analyzed all baseline and procedural coronary angiograms. QCA analysis was performed pre- and post-procedure, bifurcation angle (the angle between the distal MV and the SB at its origin, measured using the angiographic projection with the widest separation of both branches), minimum lumen diameter, reference vessel diameter, and lesion length for each vessel were measured. In addition, percent diameter stenosis (100 × [reference vessel diameter/minimum lumen diameter]/reference vessel diameter) for each vessel was determined.

The primary outcome was the 5-year incidence of target lesion failure (TLF), defined as the composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (TVMI), and target lesion revascularization (TLR). The secondary outcomes were the individual components of the primary outcome. An independent clinical event adjudication committee composed of independent interventional cardiology experts who had not participated in patient enrollment verified all the clinical events. Deaths were of cardiac cause unless an undisputed non-cardiac cause could be established. TVMI was myocardial infarction with evidence of an elevated creatine kinase-myocardial band or a troponin level higher than the standard upper limit with concomitant ischemic symptoms or electrocardiography findings indicative of ischemia in the vascular territory of the previously treated target vessels. TLR was repeat PCI of the lesion within 5 mm of the stent deployment.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using the Student's t-test for parametric data and the Mann–Whitney test for non-parametric data. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages) and were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. The cumulative incidences of clinical events are presented as Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared using a log-rank test. Patients were censored at 5 years (1,825 days) or when events occurred. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards models. In multivariable models, variables with p-values <0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis using backward elimination and multivariable Cox regression to determine the independent predictors of clinical events. After univariate analysis, adjusted HR was obtained from Cox regression based on taking insulin for DM, chronic kidney disease, preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; ≥50%), left main (LM) bifurcation, stent strategy, post-procedural distal minimal lumen diameter of the SB, and final kissing balloon (FKB) inflation. All probability values were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were significant. Propensity scores were estimated using a non-parsimonious multiple logistic regression model for stent strategy. Age, sex, initial presentation, hypertension, taking insulin for DM, dyslipidemia, current smoking status, chronic kidney disease, previous myocardial infarction, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, left ventricular ejection fraction <50%, transradial approach, use of intravascular ultrasound, left main bifurcation, and true bifurcation were selected to estimate the propensity score. A local optimal algorithm using the caliper method was used to develop propensity score-matched pairs without replacement (2:1 matching). To ensure that poorly fitting matches were excluded, a matching caliper of 0.2 SDs from the estimated propensity score logit was enforced using the MatchIt package in R Core Team (2015). R: Language and environment for statistical computing (version 3.6.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/). SPSS version 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the results.

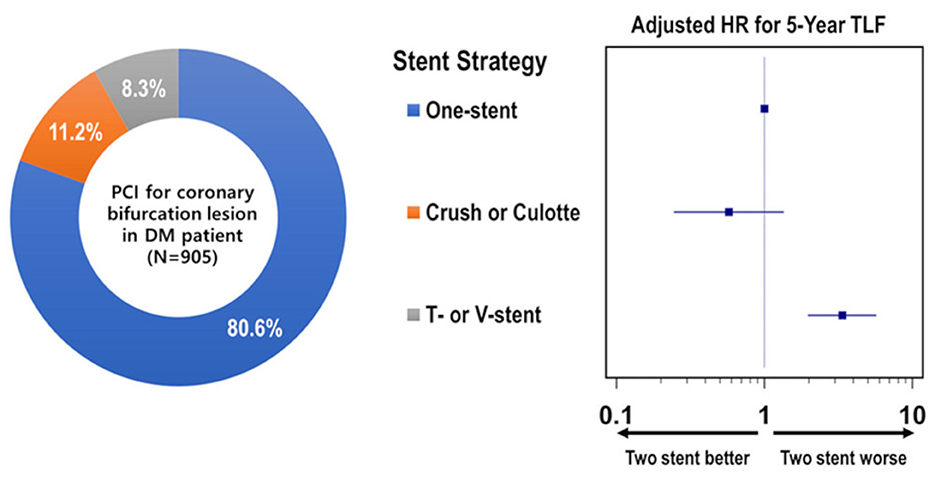

A total of 905 patients with DM and significant bifurcation lesions were enrolled in the study: 729 (80.6%) were treated with a one-stent strategy, and 176 (19.4%) were treated with a two-stent strategy. The baseline clinical and procedural characteristics of all patients with DM according to the stenting strategy are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the two-stent and one-stent groups except in the prevalence of insulin use (14.2 vs. 8.2%, p = 0.022). The two-stent group had a higher prevalence of intravascular ultrasound use (54.5 vs. 35.8%, p < 0.001), LM bifurcation (53.4 vs. 35.9%, p < 0.001), true bifurcation lesions (78.4 vs. 38.8%, p < 0.001), and FKB inflation (87.5 vs. 17.3%, p < 0.001) than the one-stent group. The transradial approach was used less often in the two-stent group than in the one-stent group (38.1 vs. 61.2%, p < 0.001). The QCA results are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

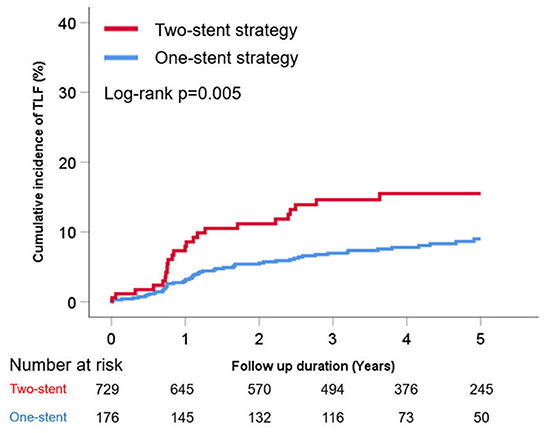

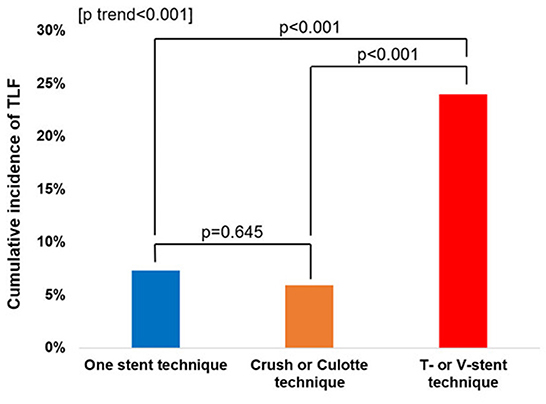

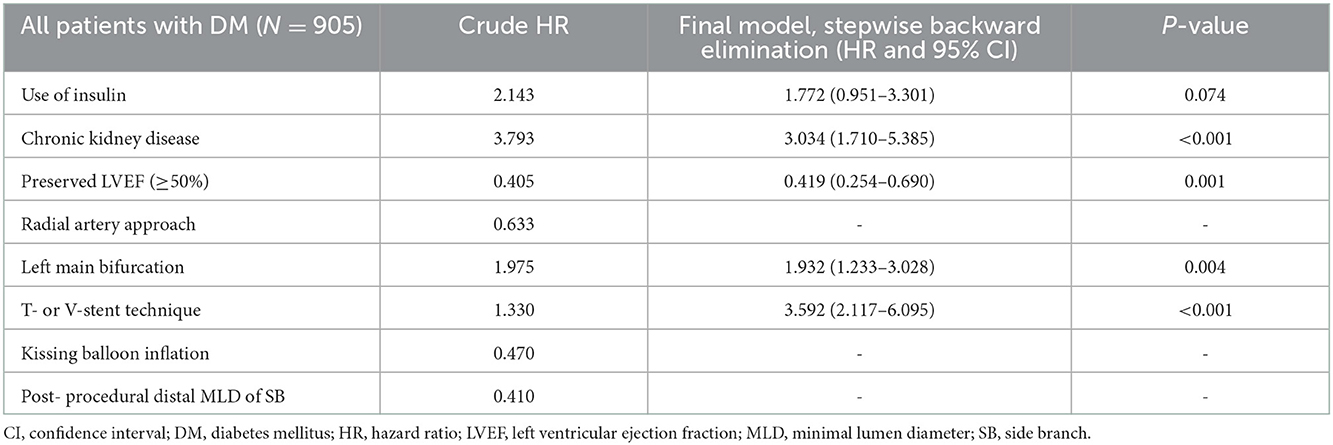

The cumulative TLF incidence was higher in patients treated with two- than one-stent strategy (13.6 vs. 7.3%, p = 0.005; Figure 1). Notably, at a mean follow-up of 42 ± 20 months, there was a significant difference in TLF incidence based on the stenting strategy (Supplementary Figure 1; p for trend <0.001), and the T- or V-stent strategy demonstrated a higher TLF incidence than the one-stent strategy (24.0 vs. 7.3%, p < 0.001). However, the crush or culotte technique and the one-stent strategy presented similar outcomes (5.9 vs. 7.3%, p = 0.645; Figure 2). In the Cox multivariate analysis, the T- or V-stent technique remained significantly associated with TLF (HR, 3.349; 95% CI, 1.960–5.721; p < 0.001), mainly driven by TLR (HR, 4.688; 95% CI, 2.478–8.869; p < 0.001), with no significant differences in cardiac death or TVMI. Meanwhile, the crush and culotte techniques did not have significantly different clinical outcomes (Figure 3). In addition, chronic kidney disease (CKD; HR, 3.071; 95% CI, 1.728–5.456; p < 0.001), reduced LVEF (HR, 2.436; 95% CI, 1.478–4.017; p < 0.001), and LM bifurcation (HR, 2.030; 95% CI, 1.290–3.195; p = 0.002) during follow-up were independent predictors of TLF in patients with DM after multivariate adjustment (Table 2). After propensity score matching (Supplementary Table 2), although there was no TLF difference between the one- and two-stent groups (11.8 vs. 8.9%, p = 0.334; Supplementary Figure 2A), the T- or V-stent technique had a higher TLF incidence than the others (Supplementary Figure 2B; p for trend = 0.025). In addition, the T- or V-stent technique remained significantly associated with TLF (HR, 2.269; 95% CI, 1.123–4.584; p = 0.022) in the propensity score matching.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of target lesion failure (TLF) of one- vs. two-stent strategy for treating coronary bifurcation lesions in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2. Incidence of target lesion failure (TLF) for one-stent, T-stent, V-stent, and crush or culotte techniques.

Figure 3. Distribution and individual risk of stent strategy for coronary bifurcation lesions in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Table 2. Independent predictors of 5-year target lesion failure in DM patients treated for coronary bifurcation lesion with stent implantation.

This study investigated the impact of stenting strategies on the clinical outcomes of patients with DM who were treated for coronary bifurcation lesions. This study revealed that the one-stent strategy for coronary bifurcation lesions presented a lower TLF incidence than the two-stent strategy, in patients with DM. The T- or V-stent technique also revealed a higher TLF incidence, mainly driven by TLR, than the one-stent strategy and crush or culotte technique. Furthermore, except for the T- or V-stent techniques, there was no difference in TLF incidence between the one- and two-stent strategies. Additionally, using the T- or V-stent technique in patients with DM undergoing PCI for coronary bifurcation lesions was an independent predictor of TLF in the multivariate analysis. CKD, reduced LVEF, and left main bifurcation lesions were independent TLF predictors.

Patients with DM are at high risk of progressive atherosclerosis regarding coronary plaque rupture and neointimal proliferation, which leads to an increased incidence of adverse clinical outcomes (4, 13). Moreover, PCI with coronary bifurcation lesions presented a higher incidence of MI, thrombosis, and revascularization than PCI with simple coronary lesions (14). A plausible explanation for the adverse prognosis after coronary bifurcation PCI is the unique local flow pattern that increases the endothelial shear stress and affects plaque development. According to our previous study, the 5-year TLF incidence was 7.8% in patients with and without DM who underwent PCI for coronary bifurcation lesions (15). The 5-year incidence rates of TLF for the one- and two-stent strategies were 7.6 and 12.1%, respectively. In this study, the 5-year incidence rate of TLF in patients with DM was 8.5%. This difference in TLF rate between the total and DM populations was primarily due to the different events in the two-stent strategy (12.1 vs. 13.6%, respectively).

To date, no randomized controlled trial or large-scale observational study has reported the clinical outcomes of coronary bifurcation lesions in patients with DM regarding stent strategy in the second-generation drug-eluting stent era. In this study, the T- or T and small protrusion (TAP) technique and V- or simultaneous kissing stenting revealed a higher TLF incidence than the other techniques and were independent predictors of TLF in multivariable analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal that different stent strategies in the two-stent technique may be associated with clinical outcomes in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions. Consistent with this study, a meta-analysis of various randomized controlled trials on coronary bifurcation stent strategies reported that the TLR rate of the T-stent or TAP technique was higher than that of other techniques (16). In the DEFINITION II trial, which included 35% of patients with DM, the double kissing crush technique had a 1-year TLR rate, superior to that of the provisional stent group (14.5 %) using the T-stent or TAP technique for bailout stenting (17).

A possible explanation for these results is the association between DM and shear stress at the bifurcation level (18). The T-stent technique is commonly used when the SB is compromised during provisional stenting; however, it has the inherent risk of suboptimal SB ostium coverage, which may lead to restenosis (19). The V-stent technique has a similar limitation regarding the suboptimal coverage of the SB ostium. The TAP stent technique has a lower risk of missing the SB ostium (19); however, it creates a metallic neocarina, where a significant portion of the unappositioned stent remains in the vessel. In addition, the post-procedural minimal lumen diameter of the main branch ostium was an independent TLF predictor. Theoretically, metallic neocarina may risk narrowing the main branch ostium. A recent study suggested obtaining the maximal diameter of the main vessel stent in PCI for a non-left main bifurcation lesion (12). In our previous study, DM was an independent TLF predictor in non-LM lesions but not in LM bifurcation lesions (12). DM is a potential factor in atherosclerosis progression and neointimal proliferation (4) and a vasoconstrictive endothelial response along with an inflammatory and prothrombotic milieu in DM. A synergistic relationship with shear stress at the bifurcation level may lead to a worse prognosis (13, 18, 20). In this study's subgroup analysis, except for the T-stent, TAP stent, and V-stent techniques, there was no significant difference in the TLF between the one- and two-stent strategies. These observations suggest that accurate stent deployment and optimization of the bifurcation carina site could reduce TLF incidence, especially in the very high-risk population with DM and bifurcation CAD (19).

In addition, CKD, reduced LVEF, and LM bifurcation were independent TLF predictors in the diabetic population. CKD is associated with a poor prognosis due to its strong correlation with various risk factors, such as hypertension, DM, and dyslipidemia, which could be a cause or consequence (21). In addition, DM is an extremely high-risk factor for patients referred for treatment of LM bifurcation. Our study also emphasizes that PCI for LM bifurcation is an independent TLF predictor in patients with DM, even in the second-generation DES era, consistent with that reported in previous studies (12, 15, 22, 23).

This study had several limitations. First, its inherent limitation is the nature of the observational registry. The multivariate adjustment was performed; nonetheless, potential bias due to unmeasured variables or confounding factors, such as body mass index, serum glucose level, and mean blood pressure, could not be excluded. Second, the range of baseline and follow-up glycemic levels of these patients could have influenced our results, and insulin use revealed a borderline significant risk of TLF (adjusted HR, 1.811; p = 0.061), which suggests that poor DM control may affect clinical outcomes, highlighting the need for further research. Finally, treatment strategy, intravascular imaging, stent type, and concomitant medication use were based on the physician's preferences. In this context, FKB inflation was relatively poorly performed in patients treated with the two-stent strategy, and the rate of POT was relatively low. However, our study has analyzed the largest real-world PCI dataset for bifurcation lesions in patients with DM.

T- or V-stenting in patients with DM showed increased cardiovascular events after second-generation DES implantation compared with one- or other two-stent strategies.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital including Korea University Anam Hospital and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by the Korean Bifurcation Club and the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology. All authors declare that the funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to publish.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1018802/full#supplementary-material

1. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, Ge L, Sangiorgi GM, Stankovic G, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. (2005) 293:2126–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2126

2. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 79:e21–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

3. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

4. Arnold SV, Bhatt DL, Barsness GW, Beatty AL, Deedwania PC, Inzucchi SE, et al. Clinical management of stable coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2020) 141:e779–806. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000766

5. Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E, et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2006) 48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042

6. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Fusaro M, Amoroso N, Kirtane AJ, Byrne RA, et al. Outcomes with various drug eluting or bare metal stents in patients with diabetes mellitus: mixed treatment comparison analysis of 22,844 patient years of follow-up from randomised trials. BMJ. (2012) 345:e5170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5170

7. Park KW, Lee JM, Kang SH, Ahn HS, Kang HJ, Koo BK, et al. Everolimus-eluting Xience v/Promus versus zotarolimus-eluting resolute stents in patients with diabetes mellitus. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2014) 7:471–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.12.201

8. Stone GW, Kedhi E, Kereiakes DJ, Parise H, Fahy M, Serruys PW, et al. Differential clinical responses to everolimus-eluting and Paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation. (2011) 124:893–900. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.111.031070

9. Romaguera R, Salinas P, Gomez-Lara J, Brugaletta S, Gómez-Menchero A, Romero MA, et al. Amphilimus- vs. zotarolimus-eluting stents in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease: the SUGAR trial. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:1320–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab790

10. D'Ascenzo F, Iannaccone M, Saint-Hilary G, Bertaina M, Schulz-Schüpke S, Wahn Lee C, et al. Impact of design of coronary stents and length of dual antiplatelet therapies on ischaemic and bleeding events: a network meta-analysis of 64 randomized controlled trials and 102,735 patients. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38:3160–72. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx437

11. Nakazawa G, Yazdani SK, Finn AV, Vorpahl M, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Pathological findings at bifurcation lesions: the impact of flow distribution on atherosclerosis and arterial healing after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2010) 55:1679–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.021

12. Cha JJ, Hong SJ, Joo HJ, Park JH, Yu CW, Ahn TH, et al. Differential factors for predicting outcomes in left main versus non-left main coronary bifurcation stenting. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:43024. doi: 10.3390/jcm10143024

13. Elia E, Montecucco F, Portincasa P, Sahebkar A, Mollazadeh H, Carbone F. Update on pathological platelet activation in coronary thrombosis. J Cell Physiol. (2019) 234:2121–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27575

14. Sawaya FJ, Lefèvre T, Chevalier B, Garot P, Hovasse T, Morice MC, et al. Contemporary approach to coronary bifurcation lesion treatment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9:1861–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.06.056

15. Choi KH, Song YB, Lee JM, Park TK, Yang JH, Hahn JY, et al. Prognostic effects of treatment strategies for left main versus non-left main bifurcation percutaneous coronary intervention with current-generation drug-eluting stent. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13:e008543. doi: 10.1161/circinterventions.119.008543

16. Elbadawi A, Shnoda M, Dang A, Gad M, Abdelazeem M, Saad M, et al. Meta-analysis comparing outcomes with bifurcation percutaneous coronary intervention techniques. Am J Cardiol. (2022) 165:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.10.048

17. Zhang JJ, Ye F, Xu K, Kan J, Tao L, Santoso T, et al. Multicentre, randomized comparison of two-stent and provisional stenting techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: the definition II trial. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:2523–36. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa543

18. Kumar A, Hung OY, Piccinelli M, Eshtehardi P, Corban MT, Sternheim D, et al. Low coronary wall shear stress is associated with severe endothelial dysfunction in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11:2072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.004

19. Burzotta F, Lassen JF, Lefèvre T, Banning AP, Chatzizisis YS, Johnson TW, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation coronary lesions: the 15(th) consensus document from the European Bifurcation club. EuroIntervention. (2021) 16:1307–17. doi: 10.4244/eij-d-20-00169

20. Irace C, Cutruzzolà A, Parise M, Fiorentino R, Frazzetto M, Gnasso C, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on brachial artery shear stress and endothelial function in subjects with type 2 diabetes: results from an exploratory study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. (2020) 17:1479164119883540. doi: 10.1177/1479164119883540

21. Sarnak MJ, Amann K, Bangalore S, Cavalcante JL, Charytan DM, Craig JC, et al. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2019) 74:1823–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1017

22. Yu CW, Yang JH, Song YB, Hahn JY, Choi SH, Choi JH, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of final kissing ballooning in coronary bifurcation lesions treated with the 1-stent technique: results from the COBIS II Registry (Korean coronary bifurcation stenting registry). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2015) 8:1297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.04.015

Keywords: coronary bifurcation angioplasty, diabetes mellitus, stent strategy, second-generation drug-eluting stent, clinical outcome, percutaneous coronary intervention (complex PCI)

Citation: Cha J-J, Hong SJ, Kim JH, Lim S, Joo HJ, Park JH, Yu CW, Kang J, Kim H-S, Gwon H-C, Chun WJ, Hur S-H, Han SH, Rha S-W, Chae I-H, Jeong J-O, Heo JH, Yoon J, Park J-S, Hong M-K, Doh J-H, Cha KS, Kim D-I, Lee SY, Chang K, Hwang B-H, Choi S-Y, Jeong MH, Song YB, Choi KH, Nam C-W, Koo B-K and Lim D-S (2022) Bifurcation strategies using second-generation drug-eluting stents on clinical outcomes in diabetic patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:1018802. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1018802

Received: 14 August 2022; Accepted: 01 December 2022;

Published: 21 December 2022.

Edited by:

Tommaso Gori, University Medical Centre, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyReviewed by:

Giuseppe Signoriello, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Cha, Hong, Kim, Lim, Joo, Park, Yu, Kang, Kim, Gwon, Chun, Hur, Han, Rha, Chae, Jeong, Heo, Yoon, Park, Hong, Doh, Cha, Kim, Lee, Chang, Hwang, Choi, Jeong, Song, Choi, Nam, Koo and Lim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Soon Jun Hong,  cHN5Y2hlOTRAZ21haWwuY29t

cHN5Y2hlOTRAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.