95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 16 December 2020

Sec. General Cardiovascular Medicine

Volume 7 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.596583

This article is part of the Research Topic What do we know about COVID-19 implications for cardiovascular disease? View all 109 articles

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality have consistently been higher in men compared to women. The possible biological and behavioral factors underlying this difference have recently been analyzed by Capuano et al. (1). The ideas raised by the authors define a clear need for a more adequate approach to sex differences in case fatality rate. The higher mortality rate in men has indeed been described extensively in literature (2–4). However, the impact of the current pandemic reaches far beyond mortality rates. To tackle this pandemic effectively, an integrated response is essential (5). That is why in this article, we would like to draw attention to some of the main structural, psychological, social and economic impacts this pandemic has on women, as observed by academics, practitioners and international organizations.

Although we acknowledge gender to be complex, social, and non-binary, we will mainly focus on the impact of the current pandemic on women and refer to other publications about the impact on transgender and non-binary populations (6–8).

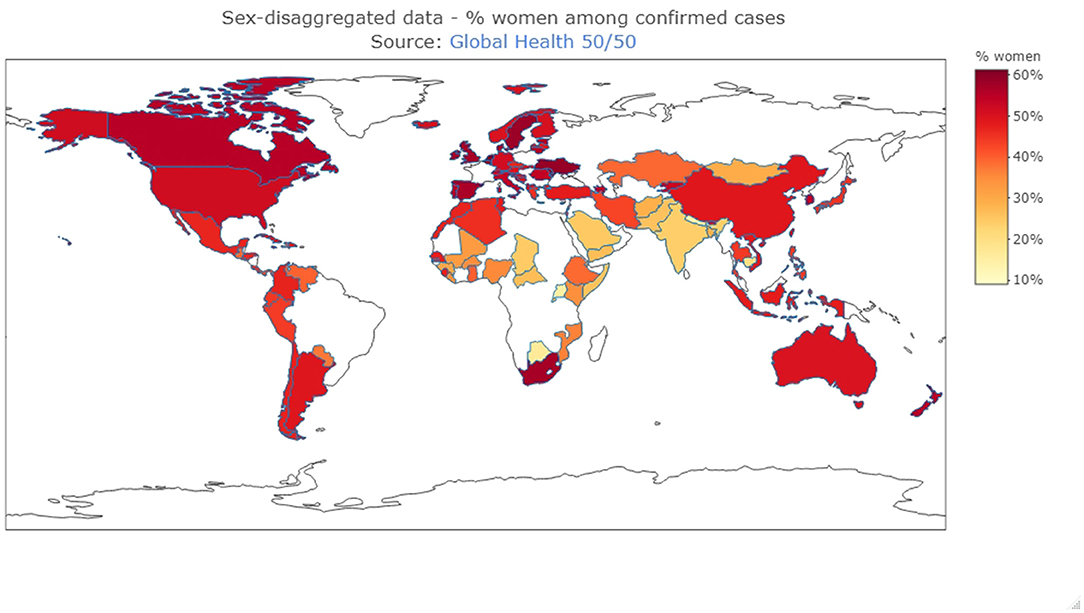

Sex- and gender-disaggregated data on COVID-19 confirmed cases are important in order to address gender disparities in COVID-19 health outcomes and ensure a gender-responsive approach. However, sex disaggregated data is lacking for most countries and gender disaggregated data is nearly absent. As of August 3, 2020, 18.07 million cases were reported worldwide. Data presented in Figure 1 (n = 8,587,718 sex-disaggregated cases), therefore, represent only 47.5% of all reported cases, highlighting the current lack of these valuable data. Furthermore, a striking difference in the percentage of women among confirmed cases is seen, with 60% in countries such as Belgium, the United Kingdom, and Canada, to 20% in countries such as the Central African Republic, Uganda, and India. Indeed, recent data show that among all persons tested for COVID-19 in the Central African Republic, only 26% were women.

Figure 1. Sex-disaggregated data (Source: Global Health 50/50, https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/sex-disaggregated-data-tracker/, 15/08/2020) Data are reported from the date that sex-disaggregated data was last available. The map was created using R Statistical Software (version 4.0.2. 2020-06-22, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), “plotly” package.

Women face a higher risk of becoming infected during a pandemic because of their position in society as reported by the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (9–11). As doctors, nurses, midwives, and community health workers, women are overrepresented at the frontlines, making up 70% of the global health and social workforce (11). Particular issues are the global lack of personal appropriate protective equipment (PPE) and the fact that most PPE are based on a “default man” size providing a suboptimal barrier to most women and leaving them more exposed (12). Data from several outbreaks Ebola outbreaks and the SARS outbreak of 2003 demonstrate that nurses and other caretakers have been heavily infected in comparison to other groups in society (13).

As a result of traditional social roles and stereotypes, women still act as the primary caregiver in households, globally spending three to four times more time on unpaid domestic work than men [The International Labor Organization (ILO)] (14). The additional care burden associated with childcare and homeschooling during lockdowns and the care for sick family members can lead to considerable health impacts including e.g., psychological stress. Usual coping mechanisms are limited, given the reduced contact with peers and the disruption of supportive networks. This especially hits single-parent households, of which the majority are headed by women (21% of households with children in the United States compared to 4% by men) (15). Furthermore, as a result, having less time for education, paid work, and career advancement, women can experience increased social inequality during this pandemic (15, 16). Stay-at-home measures together with financial and security concerns can put considerable strain on families, which in some situations can lead to domestic abuse and sexual violence. UN-reports show that violence against women and girls has increased by 25% in several countries and even doubled in some countries since the outbreak of COVID-19 (17).

Across the globe, women and girls earn less, have less access to educational opportunities, more often hold insecure jobs, and have limited access to financial resources and digital technology (18). Apart from deepening these existing inequalities, multiple studies show that the COVID-19 pandemic has a disproportionately large economic effect on women because the sectors in which they are most active are hard-hit (19). First of all, the manufacturing-and-retail industry has experienced large fallbacks in export and sales because of lockdown and distancing measures. The World Trade Organization (WTO) reports that female employees represent 80% of the workforce in ready-made garment production in Bangladesh, in which industry orders declined by 81% in April alone (20). Moreover, a larger share of women than men work in tourism and business travel which are highly disrupted by travel restrictions and will require a long recovery period (16, 18). Relying on face-to-face interactions, these occupations do not lend themselves to teleworking. Finally, this economic downturn will also be felt by female start-up entrepreneurs who are increasingly finding their way to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) (21). MSMEs tend to be the first businesses impacted in times of recession. Given the long-term economic impact that COVID-19 will have, protecting female entrepreneurship should be on the priority list of governments in order to build a faster and more inclusive growth during the economic recovery period.

The Secretary General of the Council of Europe put it best: “While the virus is resulting in the tragic loss of life, we must nonetheless prevent it from destroying our way of life” (22). Human rights reflect the minimum standards necessary for people to live with dignity. While the COVID-19 crisis is fast becoming a socio-economic crisis it adds pressure on human rights. For women and girls, the problems identified form an undeniable increased threat to their right to life and right to health (23). Various international law instruments [e.g., The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 25 (24)] recognize the right to health as an inclusive right, encompassing a wide range of factors that help humans lead a healthy life (25). These factors include safe drinking water, safe food, sanitation, but also health-related education and information, the right to access to health care, and gender equality. As the UN state in their latest Policy Brief, the economic impact and prevalence of poverty among women, their experience of violence, their position in society, the limited power many women have over their sexual and reproductive lives, and their lack of influence in decision-making are social realities that adversely impact women's human rights and that should move to global action (9).

Prevention and response management is hindered when gendered impacts of outbreaks are ignored obscuring critical trends. In order to minimize these impacts, different steps should be undertaken. In Table 1 we provide a list of important recommendations made by international organizations.

Gendered differences of COVID-19 are present not only at the biological level, but also at the psychological, social and societal level. Although literature shows that men are clearly predisposed to COVID-19 related mortality, women are just as well victimized, albeit in a different way. The current pandemic painfully highlights that gender inequality is still insufficiently addressed in our society. Public health should never be a predominantly men affair mainly focusing on the male body—a one-man show. In contrast, more gender-sensitive approaches that take into account different physical, mental, and social needs across the full gender spectrum are indispensable to guarantee optimal well-being of all.

JV and KD conceived and wrote the manuscript. KV and WO critically revised the manuscript and provided important intellectual contribution. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Capuano A, Rossi F, Paolisso G. Covid-19 kills more men than women: an overview of possible reasons. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:131. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00131

2. Gagliardi MC, Tieri P, Ortona E, Ruggieri A. ACE2 expression and sex disparity in COVID-19. Cell Death Discov. (2020) 6:37. doi: 10.1038/s41420-020-0276-1

3. Elgendy IY, Pepine CJ. Why are women better protected from COVID-19: clues for men? Sex and COVID-19. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 315:105–06. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.05.026

4. Agrawal H, Das N, Nathani S, Saha S, Saini S, Kakar SS, et al. An assessment on impact of COVID-19 infection in a gender specific manner. Stem Cell Rev Rep. (2020) 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10048-z

5. Wenham C, Smith J, Davies SE, Feng H, Grépin KA, Harman S, et al. Women are most affected by pandemics - lessons from past outbreaks. Nature. (2020) 583:194–8. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02006-z

6. Salerno JP, Williams ND, Gattamorta KA. LGBTQ populations: psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. (2020) 12:S239–42. doi: 10.1037/tra0000837

7. Wang Y, Pan B, Liu Y, Wilson A, Ou J, Chen R. Health care and mental health challenges for transgender individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2020) 8:564–5. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30182-0

8. Sevelius JM, Gutierrez-Mock L, Zamudio-Haas S, McCree B, Ngo A, Jackson A, et al. Research with marginalized communities: challenges to continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. (2020) 24:2009–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02920-3

9. United Nations. The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en.pdf?la=en&vs=1406 (accessed November 9, 2020).

10. World Health Organization? Gender and COVID-19: Advocacy Brief (2020). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332080 (accessed November 9, 2020).

11. World Health Organization. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. (2019). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed August 16, 2020).

12. Trades Union Congress. Personal Protective Equipment and Women. (2017). Available online at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/PPEandwomenguidance.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

13. World Health Organization. Addressing Sex and Gender in Epidemic-Prone Infectious Diseases. (2007). Available online at: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/SexGenderInfectDis.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

14. International Labour Organization. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. (2018). Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

15. Alon T, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt M. The impact of COVID-19 on Gender equality. In: Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers. (2020) 4:62–85.

16. World Bank Group. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. (2020). Available online at: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/618731587147227244/pdf/Gender-Dimensions-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

17. UN Women. COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls. (2020). Available online at: https://prod.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-en.pdf?la=es&vs=5006 (accessed August 16, 2020).

18. World Trade Organization. The Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women in Vulnerable Sectors and Economies. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news20_e/info_note_covid_05aug20_e.pdf?fbclid=IwAR131NFWHhdwPQIOM3GN6_jYpnwae5JTleO9pPqgFVo5sKubCi8NkNxOr6I (accessed August 16, 2020).

19. World Trade Organization. Trade in Services in the Context of COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/services_report_e.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

20. Financial Express. Bangladesh's RMG Export in April Declines Nearly 85 per cent. (2020). Available online at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1187514.shtml (accessed August 16, 2020).

21. World Trade Organization. World Trade Report 2019 – The Future of Services Trade. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/00_wtr19_e.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

22. Council of Europe. Speeches 2020 - Saint Petersburg International Legal Forum. (2020). Available online at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/secretary-general/-/saint-petersburg-international-legal-forum (accessed August 16, 2020).

23. United Nations. COVID-19 and Human Rights – We are All in This Together. (2020). Available online at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief_on_human_rights_and_covid_23_april_2020.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2ojuGQlNSdbBUOEfG-gsWWtc4FSI8f4KI7-DypyTpGBU_IiPO5R7cOSD0 (accessed August 16, 2020).

24. United Nations. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (1948). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

25. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The Right to Health, Fact Sheet No. 31. (2008). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf (accessed August 16, 2020).

26. UNICEF. Five Actions for Gender Equality in the COVID-19 Response. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/66306/file/Five%20Actions%20for%20Gender%20Equality%20in%20the%20COVID-19%20Response:%20UNICEF%20Technical%20Note.pdf (accessed on November 9, 2020)

Keywords: COVID-19, gender equality, human rights, public health, women

Citation: Van den Eynde J, De Vos K, Van Daalen KR and Oosterlinck W (2020) Women and COVID-19: A One-Man Show? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 7:596583. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.596583

Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020;

Published: 16 December 2020.

Edited by:

Shuyang Zhang, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaoxiang Yan, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Van den Eynde, De Vos, Van Daalen and Oosterlinck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jef Van den Eynde, amVmLnZhbmRlbmV5bmRlQHN0dWRlbnQua3VsZXV2ZW4uYmU=; Karen De Vos, a2FyZW4uZGV2b3NAc3R1ZGVudC5rdWxldXZlbi5iZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.