- 1Department of Pharmacology and Physiology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 2Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, Wexner Medical Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

- 3Department of Physiology, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Wexner Medical Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

Aims: Activation and expression of large conductance calcium and voltage-activated potassium channel (BKCa) by pharmacological agents have been implicated in cardioprotection from ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury possibly by regulating mitochondrial function. Given the non-specific effects of pharmacological agents, it is not clear whether activation of BKCa is critical to cardioprotection. In this study, we aimed to decipher the mechanistic role of BKCa in cardioprotection from IR injury by genetically activating BKCa channels.

Methods and Results: Hearts from adult (3 months old) wild-type mice (C57/BL6) and mice expressing genetically activated BKCa (Tg-BKCaR207Q, referred as Tg-BKCa) along with wild-type BKCa were subjected to 20 min of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion with or without ischemic preconditioning (IPC, 2 times for 2.5 min interval each). Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) was recorded using Millar's Mikrotip® catheter connected to ADInstrument data acquisition system. Myocardial infarction was quantified by 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining. Our results demonstrated that Tg-BKCa mice are protected from IR injury, and BKCa also contributes to IPC-mediated cardioprotection. Cardiac function parameters were also measured by echocardiography and no differences were observed in left ventricular ejection fraction, fractional shortening and aortic velocities. Amplex Red® was used to assess reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in isolated mitochondria by spectrofluorometry. We found that genetic activation of BKCa reduces ROS after IR stress. Adult cardiomyocytes and mitochondria from Tg-BKCa mice were isolated and labeled with Anti-BKCa antibodies. Images acquired via confocal microscopy revealed localization of cardiac BKCa in the mitochondria.

Conclusions: Activation of BKCa is essential for recovery of cardiac function after IR injury and is likely a factor in IPC mediated cardioprotection. Genetic activation of BKCa reduces ROS produced by complex I and complex II/III in Tg-BKCa mice after IR, and IPC further decreases it. These results implicate BKCa-mediated cardioprotection, in part, by reducing mitochondrial ROS production. Localization of Tg-BKCa in adult cardiomyocytes of transgenic mice was similar to BKCa in wild-type mice.

Introduction

The large conductance calcium and voltage-activated potassium channels (MaxiK, BKCa, KCa1.1) encoded by Kcnma1 gene are ubiquitously expressed in excitable and non-excitable cells (1, 2). The functional channel is comprised of four pore-forming α-subunits, each with seven transmembrane domains where S4 serves as a voltage sensor and C-terminus contains Ca2+-sensing RCK1 and RCK2 domains (3). Ca2+ and voltage sensing allow activation of BKCa (4), resulting in its physiological involvement in neurotransmitter release and secretion (2). Increasing evidence indicates that BKCa channels are located in intracellular organelles in addition to the plasma membrane, extending their functional roles in cellular physiology from organelle to organ level (1, 2, 5–10).

Studies involving activation (10–15) and inactivation (11, 16) with pharmacological and genetic tools, including global (10), and tissue-specific knockouts (17), have implicated BKCa channels in cardiac function, neuroprotection (18), and cardioprotection from ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury, in addition to IR-induced inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption in the small intestine (19). Further, it was shown that BKCa is present in the mitochondria of adult cardiomyocytes (10, 20). Tissue-specific knockouts in which BKCa was ablated in adult cardiomyocytes showed that expression of mitochondrial BKCa is responsible for its cardioprotective effect (17). It has been shown that agonists or antagonists have no effect on global (10) and cardiomyocytes-specific (17) knockouts. However, mice expressing activated BKCa have not been tested for cardioprotection from IR injury (8). Genetically modifying BKCa in mice by introducing a mutation responsible for its constitutive activation (8), independent of pharmacological agents, can further support the role of BKCa in cardioprotection from IR injury.

One of the possible outcomes of pharmacological activation or inactivation of BKCa is decrease/increase in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (21–24). The reduction in the levels of ROS accompanied by “mild” mitochondrial uncoupling (25) by BKCa agonists is assigned as a possible mechanism for organ and cellular protection from IR injury (26). As stated earlier, all of these studies rely on the use of pharmacological tools with possible non-specific effects. To understand the role of activation of BKCa and its influence on mitochondrial ROS generation, studies need to be performed independent of the pharmacological agents. Non-specific and off-target effects of pharmacological tools have generated reservations (12) on the role of BKCa in modulating levels of mitochondrial ROS as well as cardioprotection from IR injury.

In the current study, we have used genetically-activated mice where BKCa is constitutively active due to incorporation of a gain of function mutation (Tg-BKR207Q or Tg-BKCa) (8) to test the role of BKCa activation in mitochondrial ROS generation and cardioprotection from IR injury. We have established that the activation of BKCa is vital for a cardioprotective effect in both IR as well as IPC using an ex vivo isolated perfused heart model. We have further shown that activation of BKCa, attenuates ROS from complex I and complex II/III of mitochondria only after IR injury. Our results presented here further corroborate the role of BKCa in cardioprotection.

Methods

All of the experiments on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Drexel University and the Ohio State University. Animals were housed in the vivarium with food and water available ad libitum. Experiments were carried out on 3 month-old male and female. Experimentalists were blinded for the genotype of mice used.

Materials

Horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich # P6782), DCTM protein assay kit (BIO-RAD Laboratories, #500-0113, 500-0114, 500-0115), glutamate (Sigma-Aldrich # G1626), malate (Sigma-Aldrich # M6773), succinate (Fluka # 14160), pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich # P2256), Amplex® Red (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific # A12222), anti-BKCa antibody (Alomone labs, APC-21 lot #5) were procured for the study.

Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Model ex vivo

Wild-type mice or mice co-expressing genetically activated BKCa (Tg-BKCa) (8) were anesthetized with 87 mg/kg of ketamine and 13 mg/kg of xylazine by administering these agents intraperitoneally (i.p). The hearts were rapidly excised, washed in ice-cold modified Krebs-Henseleit (KH, pH 7.4, concentrations in mM: 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 24 NaHCO3, 11.1 Glucose, 2 CaCl2, 1 sodium pyruvate) solution, mounted on a cannula and perfused with KH solution at 37°C at a constant volume (2 mL/min). A pressure transducer (Millar Mikrotip® catheter) was introduced to the left ventricle, and after achieving a stable baseline, hearts were subjected to 20 min of global ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion (27). A subgroup of hearts was subjected to IPC before IR to evaluate the role of BKCa in IPC-mediated cardioprotection. Two sets of 2.5 min of ischemia and 2.5 min of reperfusion were used to precondition hearts before IR. Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) was recorded using Powerlab® hardware data acquisition system along with LabChart data acquisition and analysis software (ADInstrument, USA). After recording cardiac function, hearts either were analyzed for myocardial infarction by TTC staining or used to rapidly isolate mitochondria and measure ROS. WT IR, WT IPC, Tg-BKCa IR, and Tg-BKCa IPC group had 7, 8, 6, and 7 mice, respectively, for studying cardiac function and myocardial infarction in section- Measurement of Myocardial Infarction.

Measurement of Myocardial Infarction

Isolated hearts were thawed, cut into 5 horizontal 2-mm sections using a heart slicer matrix, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature in 2% (w/v) TTC solution in phosphate buffer saline at a pH of 7.4. Images were obtained using Nikon SMZ1000 microscope connected to Nikon digital sight DS-Fi2 camera and analyzed with Image J. WT IR, WT IPC, Tg-BKCa IR, and Tg-BKCa IPC group had 7, 8, 6, and 7 mice, respectively.

Measurement of Cardiac Function by Echocardiography

To ensure that the results obtained related to cardiovascular function and the myocardial infarction is not due to the altered cardiac function of transgenic mice, we recorded the echocardiograph of WT (n = 6) and Tg-BKCa (n = 5) mice before they were used for IR or IPC study. Vevo2100® imaging system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) with MS400 probe was used to acquire images (28). Briefly, mice were anesthetized using 2% (v/v) isoflurane in carbogen(95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide) with heart rate was maintained at more than 450 bpm. Cardiac functions were measured in both B and M mode with the probe positioned in long axis. Mean and peak velocities of the ascending and descending aorta were also recorded using color Doppler. Images were analyzed using Vevo Lab 3.1.1 analysis software.

Measurement of ROS

In case of some hearts, after reperfusion for 10 min, the cardiac tissue was rapidly cut into pieces in 2 mL of ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer A (sucrose 70 mM, mannitol 210 mM, EDTA 1 mM, Tris HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4) and homogenized using a hand-held glass homogenizer without using any detergent. The homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C, 2,500 g for 5 min and supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 4°C, 12,000 g for 10 min. The mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of mitochondria isolation buffer B (sucrose 70 mM, mannitol 210 mM, EDTA 0.1 mM, Tris HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4) and again centrifuged at 4°C, 12,500 g for 5 min. The pellets were again resuspended in 100 μL of ROS buffer (EGTA 1mM, EDTA 1mM, Tris HCl 20 mM, sucrose 250 mM, pH 7.4, 0.15% BSA was added before use) and centrifuged at 4°C, 12,000 g for 5 min. The pellets were then resuspended in 55 μL of ROS buffer and stored on ice until used for quantifying the generation of ROS. Horse Radish Peroxidase (0.5 μL of 10 mg/mL in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 6) solutions were added to 2 mL of ROS buffer in the cuvette and the solutions were continuously stirred with a magnetic stirrer at 37°C. Basal absorbance was recorded at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelength using Hitachi F-2710 fluorescence spectrophotometer. After 1 min, 2 μL of 10 μM amplex red was added to the cuvette. After another 1 min, 25 μL of the mitochondrial suspension was added to the cuvette. Subsequently, mitochondrial substrates, either glutamate (5 mM) and malate (5 mM) (WT IR, n = 3; WT IPC, n = 4; Tg-BKCa IR, n = 4; Tg-BKCa IPC, n = 4) or succinate (3 mM) (WT IR, n = 3; WT IPC, n = 4; Tg-BKCa IR, n = 4; Tg-BKCa IPC, n = 4), were added after 90 s and absorbance was recorded for a total duration of 45 min. Glutamate and malate are substrates for complex I mediated ROS production, and succinate as a substrate for complex II result in ROS production from complex III and by backflow of electrons to complex I. ROS generated was normalized per μg of mitochondrial protein. The remaining mitochondrial samples were used for measuring the protein concentration using DCTM protein assay kit from BIO-RAD Laboratories, Inc. and SPECTRAmax® spectrometer from Molecular Devices. The level of ROS produced was recorded using FL solutions software (Hitachi, USA) and ROS produced in arbitrary fluorescence units (a.u.) per μg of mitochondria were measured (29). For baseline ROS measurements, hearts from WT (n = 3) and Tg-BKCa mice (n = 3) were used without exposing the hearts to IR and IPC.

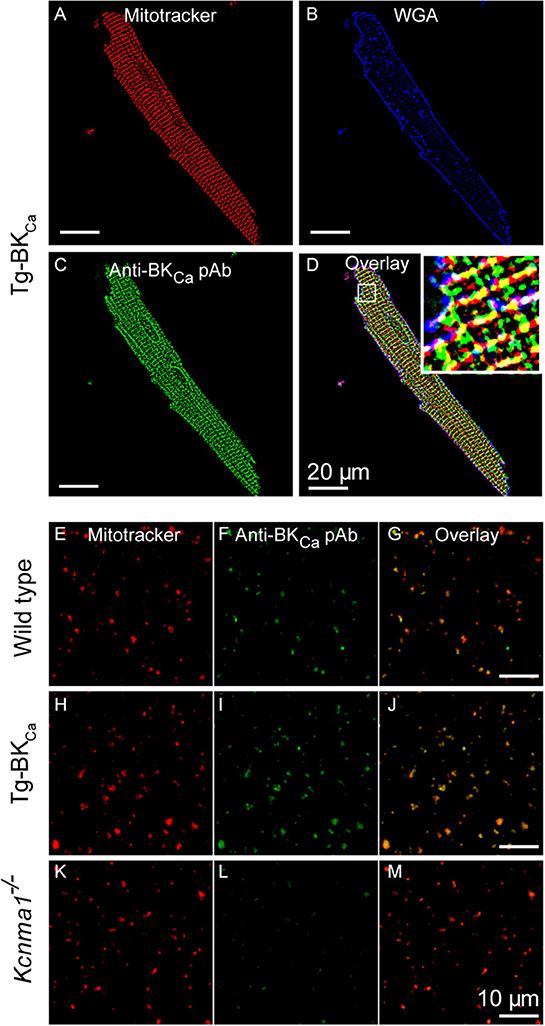

Visualization of BKca

Adult mice cardiomyocytes were isolated and loaded with mitotracker (100 nM, excitation: 579 nm and emission: 599 nm) for 60 min at 4°C followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cardiomyocytes loaded with mitotracker (n = 5) were labeled with anti-BKCa antibodies (Alomone labs, APC21, 1:200) to study the localization of BKCa in mitochondria. For studying the localization of BKCa on plasma membrane, cardiomyocytes labeled with anti-BKCa antibodies were also marked with plasma membrane marker, wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (WGA, 1:1,000, n = 5) as described earlier (10). Isolated cardiac mitochondria from wild-type (n = 6), Tg-BKCa (n = 5), and Kcnma1−/− (n = 5) mice were loaded with mitotracker and labeled with anti-BKCa antibodies as described earlier (10). Atto647N anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to label BKCa. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus) and median filtered (29).

Statistical Analysis

Student's t-test (unpaired and one-tailed) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests were used to measure the statistical difference between groups. Values are presented as mean ± SEM of 3–8 observations. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Overall, our results demonstrate that expression and activation of BKCa are vital for cardioprotection from IR injury as well as IPC-mediated cardioprotection. Cardioprotection mediated by BKCa is possibly modulated by mitochondrial ROS production.

Genetic Activation of BKCa Preserves Cardiac Function Recovery During Reperfusion

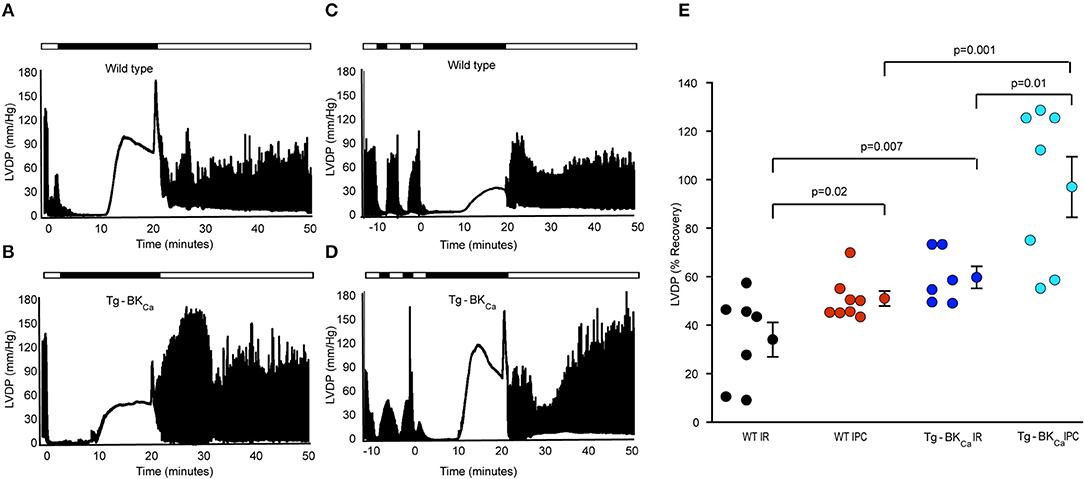

The role of activation of BKCa in cardioprotection has been demonstrated by usage of pharmacological tools (1, 10, 11, 13, 14, 30–32), and these drugs are known to have non-specific effects (12). Even though the expression of BKCa is vital for cardioprotection from IR injury (10, 17), the role of activation of BKCa in cardioprotection is not yet well-characterized. We have utilized Tg-BKCa mice expressing genetically activated BKCa in a DEC splice variant background (GenBank: JX429072.1) (8) and carried out IR injury assays with and without IPC (Figures 1A–D). Tg-BKCa mice are viable, normal in body weight (8), and exhibit increased BKCa protein expression in a wide variety of tissues as well as display increased BKCa channel currents (8). Tg-BKCa is under Period1 (Per1) promoter which is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues. Tg-BKCa mice express the R207Q mutation in the S4 voltage sensor of the BKCa α subunit which strongly augments voltage-dependent gating of the channel without affecting the Ca2+-dependent activation (33). In the Tg-BKCa mice, cardiac functional recovery was higher in comparison to the wild-type control (Figures 1B vs. A). Percentage recovery of LVDP after IR-injury was significantly higher (p = 0.02) for Tg-BKCa mice (60 ± 5%, n = 6), in comparison to WT mice (34 ± 7%, n = 7) (Figures 1A,B,E).

Figure 1. Activation of BKCa and IPC promotes the recovery of cardiovascular function from IR-injury. LVDP traces of heart of WT animal subjected to IR (A) and IPC (C) along with the LVDP traces of the heart of Tg-BKCa animal subjected to IR (B) and IPC (D) are shown. LDVP of WT hearts subjected to IPC (n = 8) showed improved recovery, in comparison to IR (n = 7) (A,C,E). LDVP of Tg-BKCa hearts subjected to IPC (n = 7), in comparison to IR (n = 6) also recovered better (B,D,E). LDVP of Tg-BKCa hearts (n = 6) subjected to IR exhibited improved recovery, in comparison to WT (n = 7) hearts (A,B,E). IPC promoted recovery of hearts from Tg-BKCa mice (n = 7) better than WT mice (n = 8) (C,D,E). The average baseline values of LVDP was 80 mmHg for 28 animals from 4 different groups. Baseline LVEDP ranged from 5 to 10 mmHg. The contractures during ischemia and reperfusion were seen in few hearts from each group in this study. The ischemic contractions are dependent on depletion of ATP during ischemia and reperfusion-induced increase in the cytosolic calcium ion. (E) Quantification of percentage recovery of LVDP as shown in (A–D), black circles indicate WT subjected to IR; red, WT IPC; blue, TG-BKCa IR and light blue Tg-BKCa IPC. The values are presented as mean ± SEM of 6–8 readings.

Genetic Activation of BKCa Confers Protection During Ischemic Preconditioning

In addition to protecting the heart from IR injury, pharmacological activation or blocking of BKCa has also been implicated in mediating cardioprotection through IPC (17, 32, 34). We have also tested whether activation of BKCa plays a role in cardioprotection mediated by IPC. Two brief IPC events before IR provided cardioprotection to wild-type (Figures 1A,C,E) as well as Tg-BKCa mice (Figures 1B,D,E). The percentage recovery of LVDP seen with the hearts from Tg-BKCa mice exposed to IPC (n = 7) was significantly higher than in Tg-BKCa mice hearts exposed to IR (p = 0.01, n = 6) and in WT mice hearts exposed to IPC (p = 0.001, n = 8). Percentage recovery of LVDP at the end of reperfusion was 51 ± 3% (n = 8) and 97 ± 12% (n = 7) for WT IPC and Tg-BKCa IPC groups, respectively.

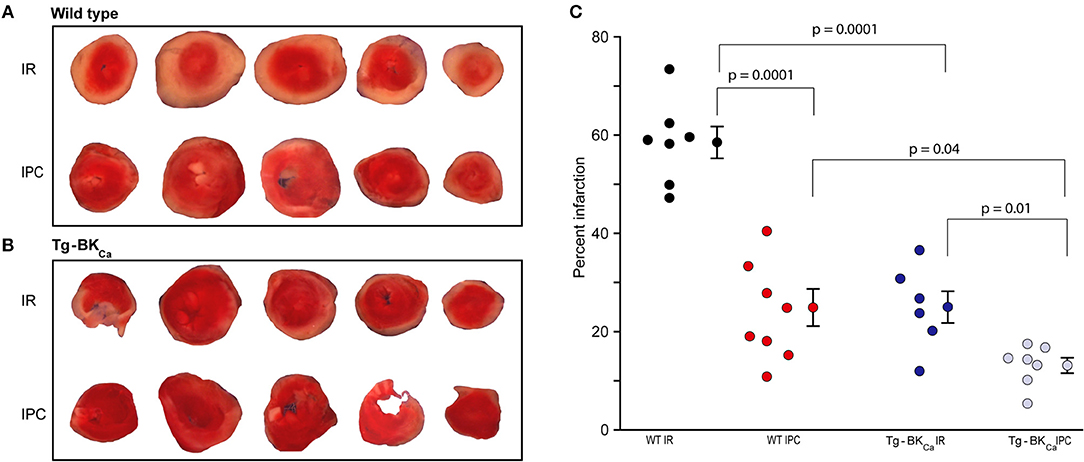

Genetic Activation of BKCa Attenuates Myocardial Infarction Following IR

The degree of myocardial infarction was quantified following IR using TTC staining. Viable cells appeared red while dead cells appeared pale yellow (Figure 2). The degree of infarction was higher in WT IR group (n = 7) with 59 ± 3% cell death but infarction was significantly less in (p = 0.0001) in WT IPC group (n = 8) with only 25 ± 4% cell death (Figures 2A–C). Hearts from Tg-BKCa mice sustained less infarction [25 ± 3% (n = 6), p = 0.04] after IR in comparison to hearts from WT mice [59 ± 3% (n = 7)] (Figures 2A–C, p = 0.0001). IPC further protected myocardium of the Tg-BKCa (n = 7) mice which exhibited the least infarction to the heart cells (13 ± 2%), (Figures 2A–C).

Figure 2. Activation of BKCa and IPC protect hearts from IR-injury. TTC staining differentiated between infarcted (white) and viable cells (red) in the hearts of WT (A) and Tg-BKCa (B) mice. (C) The infarcted area was quantified by planimetry using ImageJ. Quantification of (A,B), black circles indicate WT subjected to IR; red, WT IPC; blue, TG-BKCa IR and light blue Tg-BKCa IPC. Hearts of WT mice subjected to IPC (n = 8) presented less infarction as compared to hearts subjected to only IR (n = 7) (A,C). Similarly, the hearts of Tg-BKCa mice subjected to IPC (n = 7) were protected better than hearts subjected to only IR (n = 6) (B,C). The hearts from Tg-BKCa mice were better protected from WT mice when subjected to IR and IPC (A–C). Values are presented as mean ± SEM of 6–8 readings.

Taken together, our results (Figures 1, 2) implicate genetic activation of BKCa in cardioprotection from IR injury as well as cardioprotection mediated by IPC.

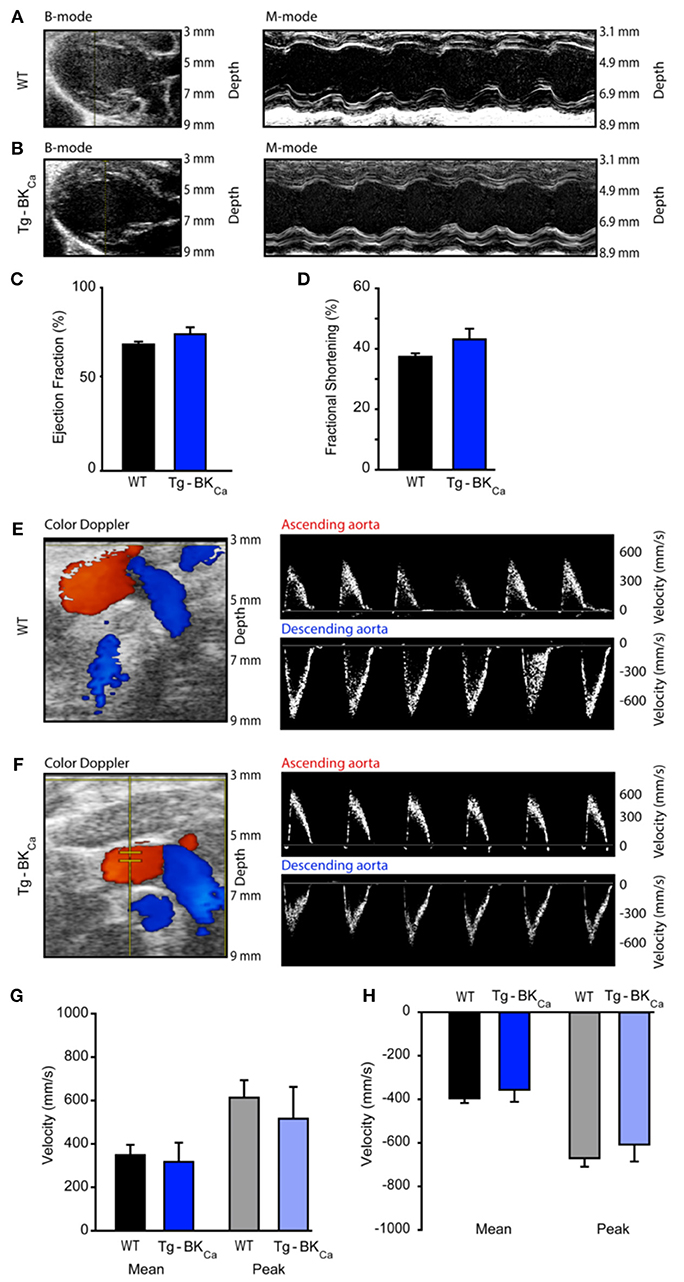

Cardiac Functional Parameters of WT and Tg-BKCa Mice Did Not Alter at the Baseline

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and fractional shortening (LVFS) assessed by echocardiography (Figures 3A,B) did not demonstrate any differences. The LVEF of WT and Tg-BKCa were 69 ± 2% (n = 6) and 75 ± 4% (n = 5), respectively (Figure 3C). The fractional shortening of WT and Tg-BKCa were 37 ± 1% (n = 6) and 43 ± 4% (n = 5), respectively (Figure 3D). Similarly, we did not observe any difference in the mean and peak velocities in the ascending aorta and descending aorta of both the WT and Tg-BKCa mice (Figures 3E–H). Mean ascending aorta velocities of WT and Tg-BKCa were 347 ± 47 mm/s (n = 6) and 315 ± 88 mm/s (n = 5), respectively (Figure 3G). The peak ascending aorta velocities of WT and Tg-BKCa were 611 ± 80 and 515 ± 145 mm/s, respectively (Figure 3G). The mean descending aorta velocities of WT and Tg-BKCa were −398 ± 22 mm/s (n = 6) and −358 ± 56 mm/s (n = 5), respectively (Figure 3H). The peak descending aorta velocities of WT and Tg-BKCa were −661 ± 38 mm/s (n = 6) and −616 ± 79 mm/s (n = 5), respectively (Figure 3H).

Figure 3. Cardiovascular function of WT and Tg-BKCa mice. WT and Tg-BKCa mice were anesthetized and comprehensive echocardiography measurements were obtained to evaluate cardiac function. (A,B) Representative B-mode and M-mode of mice hearts from both groups. Left ventricular ejection fraction (C) and fractional shortening (D) were measured using the parasternal long axis view. There was no difference between WT (black) and Tg-BKCa (blue) mice. (E,F) Color Doppler of ascending (red) and descending (blue) aorta from both groups. The right panel shows representative images of peak velocities of ascending and descending aorta from both groups. (G) Mean (black and blue) and peak (gray and light blue) velocities of ascending aorta of WT and Tg-BKCa mice showed no difference. (H) Mean (black and blue) and peak (gray and light blue) velocities of descending aorta of WT and Tg-BKCa mice showed no difference. The values are presented as mean ± SEM of 5–6 readings.

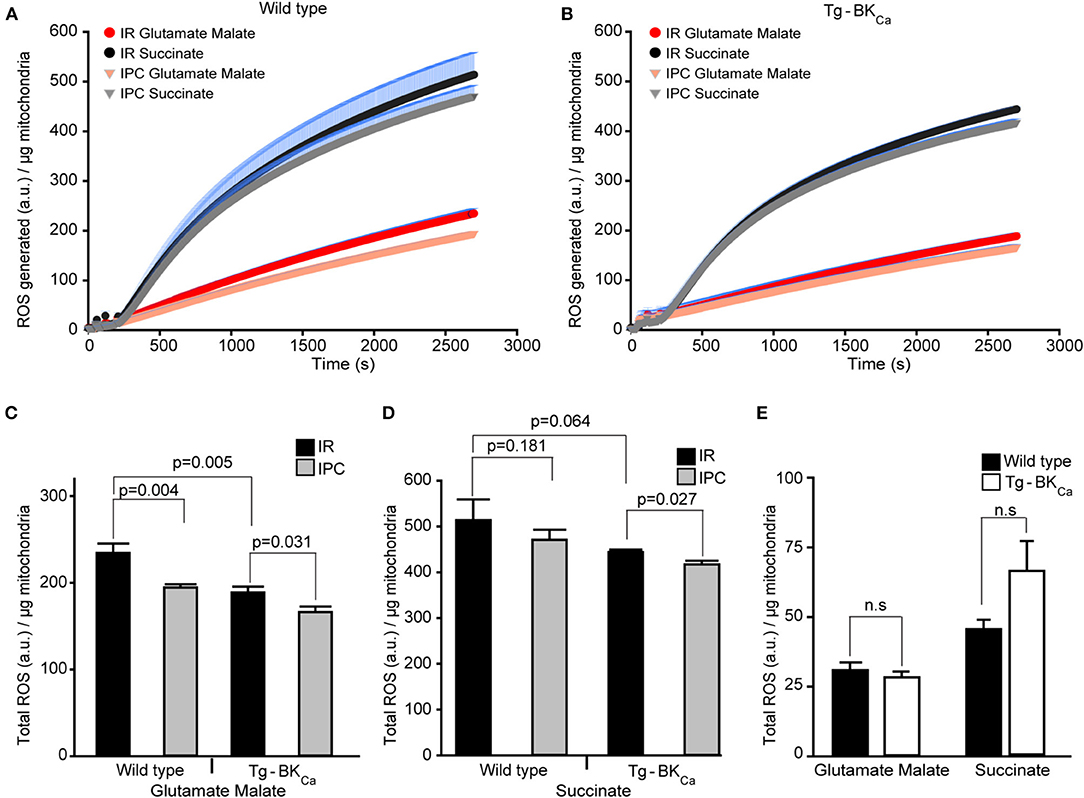

Genetic Activation of BKCa Reduces the Production of Mitochondrial ROS

ROS produced during IR-mediated injury is well-characterized in cardiac cell death (35), and BKCa has been pharmacologically implicated in the modulation of cardiac mitochondrial ROS generation (17, 19, 21, 22, 24, 26, 32, 36, 37). Given that BKCa is present exclusively in mitochondria of adult cardiomyocytes (10) and plays a direct role in cardioprotection from IR injury (17), we tested whether activation of BKCa can directly modulate mitochondrial ROS production. We quantified the amount of ROS produced by isolated mitochondria after 20 min of ischemia and 10 min of reperfusion (Figures 4A,B). With IPC (n = 4), the amount of ROS produced with glutamate and malate as substrates for mitochondria from hearts of WT mice were significantly (p = 0.004) reduced, in comparison to hearts only exposed to IR (n = 3) (234 ± 10 a.u./μg of mitochondria vs. 193 ± 4 a.u./μg of mitochondria, Figure 4C). The amount of ROS produced after IPC (n = 4) with glutamate and malate as substrates from the heart of Tg-BKCa mice was also significantly (p = 0.003) reduced, in comparison to hearts only exposed to IR (n = 4) (188 ± 7 a.u./μg of mitochondria vs. 166 ± 6 a.u./μg of mitochondria, Figure 4C). Surprisingly, ROS produced from mitochondria isolated from hearts of Tg-BKCa mice subjected to IR showed similar levels of ROS as wild-type subjected to IPC (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Cardioprotection is inversely proportional to the amount of ROS produced during reperfusion. ROS produced by the mitochondria from the heart of WT (A) or Tg-BKCa (B) mice exposed to IR with or without IPC. The generation of ROS by succinate (black and gray) is higher than glutamate and malate (red and orange). (C) Quantification of total ROS produced with glutamate and malate as substrate. ROS produced by mitochondria from the heart of WT mice exposed to IR (n = 3) is higher, in comparison to heart exposed to IPC (n = 4). Similarly, ROS produced by mitochondria from the heart of Tg-BKCa mice exposed to IR (n = 4) is higher, in comparison to heart exposed to IPC (n = 4). ROS produced with glutamate and malate by mitochondria from the heart of WT mice exposed to IR is higher than Tg-BKCa heart exposed to IR. (D) Quantification of total ROS produced with succinate as substrate. Mitochondrial ROS from the heart of WT mice exposed to IR (n = 3) is not different, in comparison to heart exposed to IPC (n = 4). However, ROS produced by cardiac mitochondria isolated from the heart of Tg-BKCa mice exposed to IR (n = 4) is higher than heart exposed to IPC (n = 4). (E) The amount of ROS produced by the mitochondria isolated from the heart of BKCa and Tg-BKCa mice not subjected to IR are not different in presence of any substrate. Mitochondrial protein yield was measured, and it was between 0.3 and 0.6 μg/μL. ROS accumulated / μg of mitochondrial protein was expressed for 45min continuously in (A,B). ROS produced a.u./μg of mitochondrial protein was expressed for 45th min in (C–E). Values are presented as mean ± SEM of 3–4 independent experiments.

The ROS produced by succinate as a substrate for cardiac mitochondria isolated from Tg-BKCa mice exposed to IPC (n = 4) was significantly (p = 0.027) decreased, in comparison to hearts exposed to IR (n = 4) (444 ± 6 a.u./μg of mitochondria vs. 417 ± 8 a.u./μg of mitochondria, Figures 4B,D). However, the ROS produced by succinate from the heart of WT mice exposed to IPC (n = 4) was similar (p = 0.181) to WT mice hearts exposed to IR (n = 3) alone (514 ± 45 a.u./μg of mitochondria vs. 471 ± 21 a.u./μg of mitochondria, Figures 4B,D). These results indicate that IPC decreases ROS levels from complex I (Figure 4C) with glutamate and malate as a substrate, and not from complex II/III (Figure 4D) where succinate was used as a substrate in wild-type mice. ROS produced in presence of glutamate and malate, or succinate was lower in Tg-BKCa mice (Figures 4C,D).

We further measured ROS levels in mitochondria rapidly (29) isolated from hearts of wild-type (n = 3) and Tg-BKCa mice (n = 3) which were not subjected to any ischemic stress. Surprisingly, there were no differences observed in ROS produced by mitochondria in the presence of glutamate-malate or succinate (Figure 4E). Although the ROS produced by succinate in Tg-BKCa mice was ~30% higher, in comparison to WT mice, we did not see any statistical difference due to wide variation in the level of ROS even with 95% power. The cardioprotective effect shown here using transgenic Tg-BKCa mice is similar to that of pharmacological preconditioning using activators of BKCa (38, 39).

BKCa Co-localizes to Mitochondria of Mice Cardiomyocytes

As stated earlier, in adult cardiomyocytes BKCa has been exclusively localized to the inner membrane of mitochondria (10, 20). Our results implicate BKCa in mitochondrial ROS generation under ischemic stress. We tested whether BKCa localizes to cardiac mitochondria of Tg-BKCa mice. In adult cardiomyocytes, BKCa localizes to mitochondria loaded with mitotracker but not in the plasma membrane in Tg-BKCa mice (Figures 5A–D). Protein proximity index (10) for BKCa to mitotracker and plasma membrane loaded mitochondria was 0.54 ± 0.1 (n = 5), and 0.2 ± 0.09 (n = 5) indicating a stronger correlation with mitochondria than plasma membrane. We further isolated mitochondria from the heart of WT and Tg-BKCa mice and observed mitochondrial localization of BKCa (PPI of 0.6 ± 0.1, n = 6 and 0.71 ± 0.2, n = 5, respectively, Figures 5E–M). Our observations indicate that the genetic alteration of BKCa (BKR207Q) does not affect its cardiac distribution or its mitochondrial localization. No specific signals were observed for BKCa channels in the mitochondria of Kcnma1−/− mice (n = 5) as demonstrated with immunostaining (Figures 5K–M).

Figure 5. BKCa and Tg-BKCa localize in the mitochondria of heart. We isolated the cardiomyocytes by enzymatic digestion from the heart of Tg-BKCa animals using Langendorff apparatus. The cardiomyocytes were fixed and labeled with mitochondrial marker (MitoTrackerTM) (A) plasma membrane marker (wheat germ agglutinin/WGA) (B) and BKCa marker (C). Overlay of these images (D) confirmed that Tg-BKCaR207Q are found to be localized in the mitochondria. Mitochondria were isolated from the cardiomyocytes of WT mice and labeled with mitotracker (E) and Anti-BKCa polyclonal antibody (F). Overlay of both the images (G) showed that BKCa is present in the mitochondria. Similarly, mitochondria were isolated from the cardiomyocytes of Tg-BKCa mice and labeled with mitotracker (H) and Anti-BKCa polyclonal antibody (I). Overlay of both the images (J) showed that Tg-BKCaR207Q is present in the mitochondria. Mitochondria were also isolated from the cardiomyocytes of Kcnma1−/− mice, and labeled with mitotracker (K) and Anti-BKCa polyclonal antibody (L). Overlay of both the images (M) showed that BKCa was effectively deleted in the mice (n = 5).

Discussion

BKCa channels are modulated by calcium, voltage, and several other cellular components, making them key pathophysiological targets. Auxiliary proteins, β and γ subunits also directly regulate the activity of BKCa channels, as well as, their sensitivity toward channel activators and blockers. One of the major breakthroughs in BKCa-centric research over the past two decades is the availability of small molecular openers for BKCa channels. These small molecules and pharmacological agents have provided ample opportunities to decipher the role of BKCa channels in physiological functions. The use of several pharmacological agents including, NS1619 and NS11021, to activate BKCa has been shown to play a vital role in cardioprotection and neuroprotection from IR injury. However, due to non-specific and off-target effects of drugs (40–44), clinical application of BKCa agonists is not yet initiated. Preclinical and basic research provides sufficient evidence for a translational aspect of BKCa activators but due to limitations related to specificity and the lack of potency (40–44), concerns have been raised on the role of activation of BKCa in pathological conditions (45). The need to revisit the issue related to the role of activation of BKCa in a pathological condition such as IR injury is critical in the light of recent findings that expression of BKCa is vital for cardioprotection using global (10, 32) and cardiac-specific (17) knockout mice.

In this study, we have used transgenic mice expressing the mutant subunit driven by Per1 locus. Per1 is ubiquitously expressed in a wide variety of tissues and in a previous study, it was shown that Tg- mice displayed overexpression of constitutively-activated BKCa in several different tissues including aorta. In adult cardiomyocytes and cardiac mitochondria isolated from Tg-BKCa mice, there were no differences observed in the localization of BKCa, implying that overexpression of the mutant does not interfere with its cellular or organelle localization. We have not observed any abnormal phenotype or behavior in Tg-BKCa mice. Cardiovascular analysis using echocardiography also did not demonstrate abnormal cardiac function, in comparison to the wild-type mice. Hence, Tg-BKCa mice provide an appropriate tool to test whether overexpression and activation of BKCa play a role in cardioprotection as shown by global (10) and cardiomyocytes-specific (17) null mutant mice.

In the last two decades, several studies using pharmacological tools have suggested a protective role of BKCa from IR injury and in IPC-mediated cardioprotection and are summarized in recent reviews (1, 5). The first study to implicate BKCa in cardioprotection (i.e., improved LVDP and reduced infarction) from global IR injury was conducted using the agonist NS1619, the effects of which were blocked by paxilline (20). Improved LVDP by preconditioning with 3 μM NS1619 was confirmed by Stowe et al. (38) possibly by modulating mitochondrial ROS and Ca2+ concentrations. The same group has proposed that opening of BKCa elevates the level of K+ in the matrix of mitochondria, which is exchanged for H+ ion by a K+/H+ exchanger (46). Increase in the level of H+ in the mitochondrial matrix stabilizes mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) so that unutilized electrons combine with oxygen to generate a small amount of mitochondrial oxygen radicals and other ROS, which then protects the cardiomyocytes by stimulating downstream protective signaling pathways. In addition to NS1619, studies involving other BKCa channel openers, NS11021 (14) and naringenin (47), have also demonstrated that cellular and cardioprotection from IR injury further provide strong evidence for the role of BKCa in cardioprotection. However, in primary rat cortical neurons, NS1619-preconditioning caused mitochondrial depolarization which could not be prevented by paxilline (48).

Pharmacological data using agonists and antagonists provides strong evidence for the role of BKCa in cardioprotection. However, the same set of drugs have resulted in non-specific effects in cells and organs. Paxilline, although is a specific BKCa-blocker, abolished isoflurane-mediated cardioprotection in wild-type as well as Kcnma1−/− mice12. NS1619 (>10 μM) is known to inhibit SERCA (49), mitochondrial respiratory chain (44, 50), and H+/K+ leak (46). These issues have largely been addressed by using low concentrations (≤10μM) of NS1619 in conjunction with global (10) and cardiomyocytes specific (17) BKCa knockout mice. Our results using activated BKCa reiterated and further supported the studies involving global (10, 12, 32) and cardiomyocytes specific (17) knockout mice.

Interestingly, we observed an increase in the LVDP amongst a few hearts from Tg-BKCa mice exposed to IPC (4 out of 7) beyond 100% during the reperfusion stage, in comparison to the baseline. We used a constant flow approach for this experiment. We anticipate that in the presence of some degree of infarction, the remaining cardiomyocytes would contract more and beat faster to balance the pressure overload arising due to the constant flow of buffer solution to the isolated heart. An increase in LVDP and + dp/dt was also observed by Okazaki et al. after IR-injury (51). Similarly, Papanicolaou et al., also observed an increase in LDVP up to 150% in mitofusin-2 deleted hearts after 10 min of ischemia and 20 min of reperfusion ex vivo, using Langendorff model (52). Moreover, an increase in the LVDP is associated with an increase in the flow rate (51) in ex vivo IR study and BKCa activator, rottlerin, is known to increase the flow rate post ex vivo IR (24).

As others have shown, we too provide evidence that BKCa is exclusively present in mitochondria of adult cardiomyocytes and modulate mitochondrial function. In a recently published study, the notion of BKCa in adult cardiomyocytes playing a role in cardioprotection was confirmed, and cardioprotective role via BKCa in smooth muscle cells was ruled out by using tissue-specific knockouts (17). However, an argument regarding the role or necessity of activation of BKCa to provide cardioprotection from IR injury is still valid. Our study involving mice expressing activated BKCa without any pharmacological tools support the notion that in addition to the expression of BKCa, activation of BKCa is also important in cardioprotection from IR injury. Expression of protected the heart from IR injury, as well, as improved the recovery of LVDP after IPC and IR injury. Further, we also noticed a remarkable decrease in myocardial infarction in hearts isolated from Tg-BKCa mice as compared to wild-type mice. IPC as anticipated, reduced myocardial infarction in wild-type mice which was further augmented in Tg-BKCa mice, implying that activation of BKCa can further enhance the IPC-mediated cardioprotection from IR injury. Soltysinka et al. (32) demonstrated a cause-effect relationship between “IPC-mediated cardioprotection” and “BKCa” using global BKCa knockout mice. Cardioprotective property of IPC was lost in the hearts collected from BKCa knockout mice (31). Our results along with other studies using global or tissue-specific knockout mice imply that expression and activation of BKCa play an important role in cardioprotection from IR injury.

In IR injury, ROS is well-characterized to be the major player as a second messenger involved in preconditioning (53). Complex III of the electron transport chain (ETC) is the main site for ROS production, and the ROS produced is directed away from the antioxidant defenses of the mitochondrial matrix (54). However, complex I mediated ROS products are released in the mitochondrial matrix in the proximity of defense enzyme systems and is known to change the redox state of proteins present in the mitochondrial matrix, which causes a deleterious impact on cellular physiology (55). Association of K+ channels to mitochondrial ROS has been well-established (56, 57). Specifically, KATP channels mediate influx of K+ into the mitochondrial matrix resulting in a small augmentation of ROS production to induce cardioprotection (56, 57). In contrast, pharmacological tools aimed at BKCa channels indicate that the opening of BKCa reduces IR-induced large-scale ROS production whereas closing the BKCa channel increases deleterious ROS production (22, 24, 58). Recently, using cardiac-specific BKCa knockout mice, it was shown that the absence of BKCa increases ROS (17) which has been proposed earlier to regulate endoplasmic calcium release (59). Increase in ROS in the knockout mice is independent of change in expression of ROS degrading enzymes such as CuZnSOD (SOD1) and MnSOD (SOD2) (17). We have observed that activation of BKCa does not affect the ROS production at the basal levels, however, after IR injury, activation of BKCa results in a reduction in ROS production. The decline was observed for both complexes of the ETC in isolated mitochondria from Tg-BKCa mice. The other factor to be taken into account is the amount in addition to the site of production of ROS available in the cell (55). IPC reduced ROS generated by complexe I in wild-type mice which indicate that reducing the total amount of ROS can also protect the cardiac tissue.

Activation of BKCa is also known to increase the Ca2+ retention capacity of mitochondria (10). Our recent findings on Ca2+ (10), and ROS in this study, and studies from other groups have indicated that BKCa-mediated cardioprotection involves an interplay between ROS, Ca2+ and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) (1, 5, 22, 31, 38, 46, 60–62). One possible mechanism is an increase in Ca2+ retention capacity possibly by modulating a mitochondrial Ca2+ pump on activation of BKCa, hence allowing more Ca2+ uptake during ischemia-reperfusion. Also, blocking BKCa channels either pharmacologically or genetically enhances ROS production, hence increasing myocardial infarction. The precise manner of how Ca2+ modulates ROS generation is not well-understood. However, three-dimensional conformational changes induced by Ca2+ in the ETC complexes, such as changes in complex IV have been reported (63, 64). Direct addition of BKCa channel activator in isolated mitochondrial preparation results in depolarization (5, 46) of mitochondrial membrane potential which made it difficult to study mitochondrial BKCa channels in isolated preparations. However, the use of genetic approaches clearly indicates that partial activation (Tg-BKCa) does not change mitochondrial ROS generation under physiological conditions. During stress, the increase in Ca2+ influx could further increase the open probability of the channel which could result in a reduction of ROS as observed in our studies. Since the decrease in ROS levels has been associated with cardioprotection from IR injury (65, 66), we anticipate that activation of BKCa reduces deleterious ROS production, hence decreases Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum and reduction in an influx of Ca2+ to the matrix and prevents Ca2+ overload in mitochondria (59). This complex interplay between Ca2+ and ROS is known to result in apoptosis, possibly by opening the mPTP. Hence, activation of BKCa can be linked to delay in the formation and/or closing of mPTP.

In summary, our study implicates overexpression of activated BKCa in cardioprotection against IR injury, and cardioprotection is mediated, in part, by decreasing deleterious mitochondrial ROS generation.

Limitations of the Study

Even though, our study does not involve pharmacological tools, there are several limitations which should be mentioned. The Tg-BKCa mice are not homozygous but are generated in the background of wild-type mice as the homozygous mouse is embryonic lethal (8). The animals are phenotypically normal. This finding is important as usage of heterozygous mice suggests that partial activation of BKCa is sufficient for cardioprotection and reduction of mitochondrial ROS. The gain-of-function BKCa is present in all the cells under Per1 locus. Since Per1 is present in most cells types, the effect we observed could also arise from non-cardiomyocytes. Non-cardiomyocyte cells such as cardiac neurons are known to play a role in cardioprotection as well as cellular protection as reported earlier (12). Our study does not rule out the role of non-cardiomyocyte BKCa in cardioprotection from IR injury. Our ex vivo approach using the Langendorff method partially rules out non-cardiac BKCa as the heart is excised and isolated from other organs during the experiment. Since hearts were not paced at a constant rate, ± dp/dt may not be a good index of cardiac function. Therefore, we did not report ± dp/dt. We further isolated mitochondria and measured ROS levels with and without IR. Our results also indicate that BKCa channel activation can modulate mitochondrial ROS levels. We have observed statistical significance in between WT and Tg-BKCa IR for LVDP, infarction, and ROS production but not in WT IR vs. IPC when one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests was used. This could be due to the shorter duration of reperfusion (30 min).

Tg-BKCa construct is generated on DEC splice variant (8) which is known to facilitate localization of BKCa to mitochondria (10), and we did not observe any change in localization of BKCa in cardiomyocytes or isolated mitochondria. Therefore, we corroborate earlier findings involving pharmacological and global, as well as cardiac-specific null mutant mice, in addition to the expression of BKCa, activation of BKCa plays an important role in cardioprotection from IR injury.

Ethics Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations from National Institute of Health. All protocols involving animals were approved by the Drexel University College of Medicine and the Ohio State University IACUC.

Author Contributions

SKG, DP, ATH, KS, PK, SGR, MK, and HS performed the research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. ALM generated Tg-BK and BK mutant mice.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust, American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant 11SDG230059 (HS), American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 16GRNT29430000 (HS), National Institute of Health R01-HL133050 (HS), R01-HL102758 (ALM), R01-HL136232 (MK), and Drexel University College of Medicine startup funds to HS.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Rajika Roy and Prof. Walter J. Koch at Center for Translational Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, for their help in quantifying the level of myocardial infarction and discussions. We would also like to thank Dr. Chun-An (Andy) Chen, and Dr. Naresh Kumar from the Khan laboratory at the Ohio State University for their help with Langendorff system and microscopy, respectively. We thank Dr. Parmpreet Gill for proofreading the manuscript.

References

1. Singh H, Stefani E, Toro L. Intracellular BK(Ca) (iBK(Ca)) channels. J Physiol. (2012) 590:5937–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.215533

2. Toro L, Li M, Zhang Z, Singh H, Wu Y, Stefani E. MaxiK channel and cell signalling. Pflugers Arch. (2012) 466:875–86. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1359-0

3. Hite RK, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis for gating the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature (2017) 541:52–7. doi: 10.1038/nature20775

4. Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2006) 7:921–31. doi: 10.1038/nrn1992

5. Balderas E, Zhang J, Stefani E, Toro L. Mitochondrial BKCa channel. Front Physiol. (2015) 6:104. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00104

6. Li B, Jie W, Huang L, Wei P, Li S, Luo Z, et al. Nuclear BK channels regulate gene expression via the control of nuclear calcium signaling. Nat Neurosci. (2014) 17:1055–63. doi: 10.1038/nn.3744

7. Meredith AL, Thorneloe KS, Werner ME, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Overactive bladder and incontinence in the absence of the BK large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem. (2004) 279:36746–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405621200

8. Montgomery JR, Meredith AL. Genetic activation of BK currents in vivo generates bidirectional effects on neuronal excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:18997–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205573109

9. Singh H, Li M, Hall L, Chen S, Sukur S, Lu R, et al. MaxiK channel interactome reveals its interaction with GABA transporter 3 and heat shock protein 60 in the mammalian brain. Neuroscience (2016) 317:76–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.058

10. Singh H, Lu R, Bopassa JC, Meredith AL, Stefani E, Toro L. mitoBKCa is encoded by the Kcnma1 gene, and a splicing sequence defines its mitochondrial location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:10836–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302028110

11. Shi Y, Jiang MT, Su J, Hutchins W, Konorev E, Baker JE. Mitochondrial big conductance KCa channel and cardioprotection in infant rabbit heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2007) 50:497–502. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318137991d

12. Wojtovich AP, Nadtochiy SM, Urciuoli WR, Smith CO, Grunnet M, et al. A non-cardiomyocyte autonomous mechanism of cardioprotection involving the SLO1 BK channel. Peer J. (2013) 1:e48. doi: 10.7717/peerj.48

13. Shintani Y, Node K, Asanuma H, Sanada S, Takashima S, Asano Y, et al. Opening of Ca2+-activated K+ channels is involved in ischemic preconditioning in canine hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2004) 37:1213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.09.012

14. Bentzen BH, Osadchii O, Jespersen T, Hansen RS, Olesen SP, Grunnet M. Activation of big conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BK) protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pflugers Arch. (2009) 457:979–88. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0583-5

15. Behmenburg F, Dorsch M, Huhn R, Mally D, Heinen A, Hollmann MW, et al. Impact of mitochondrial Ca2+-sensitive potassium (mBKCa) channels in sildenafil-induced cardioprotection in rats. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0144737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144737

16. Patel NH, Johannesen J, Shah K, Goswami SK, Patel NJ, Ponnalagu D, et al. Inhibition of BKCa negatively alters cardiovascular function. Physiol Rep. (2018) 6:e13748. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13748

17. Frankenreiter S, Bednarczyk P, Kniess A, Bork NI, Straubinger J, Koprowski P, et al. cGMP-elevating compounds and ischemic conditioning provide cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury via cardiomyocyte-specific BK channels. Circulation (2017) 136:2337–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028723

18. Liao Y, Kristiansen AM, Oksvold CP, Tuvnes FA, Gu N, Rundén-Pran E, et al. Neuronal Ca2+-activated K+ channels limit brain infarction and promote survival. PLoS ONE (2010) 5:e15601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015601

19. Dai H, Wang M, Patel PN, Kalogeris T, Liu Y, Durante W. Preconditioning with the BKCa channel activator NS-1619 prevents ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation and mucosal barrier dysfunction: roles for ROS and heme oxygenase-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2017) 313:H988–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00620.2016

20. Xu W, Liu Y, Wang S, McDonald T, Van Eyk JE, Sidor A, et al. Cytoprotective role of Ca2+- activated K+ channels in the cardiac inner mitochondrial membrane. Science (2002) 298:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1074360

21. Kulawiak B, Kudin AP, Szewczyk A, Kunz WS. BK channel openers inhibit ROS production of isolated rat brain mitochondria. Exp Neurol. (2008) 212:543–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.05.004

22. Heinen A, Aldakkak M, Stowe DF, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Varadarajan SG, et al. Reverse electron flow-induced ROS production is attenuated by activation of mitochondrial Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2007) 293:H1400–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00198.2007

23. Facundo HT, Fornazari M, Kowaltowski AJ. Tissue protection mediated by mitochondrial K+ channels. Biochim Biophys Acta (2006) 1762:202–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.06.003

24. Cordeiro B, Terentyev D, Clements RT. BKCa channel activation increases cardiac contractile recovery following hypothermic ischemia/reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2015) 309:H625–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00818.2014

26. Szewczyk A, Jarmuszkiewicz W, Kunz WS. Mitochondrial potassium channels. IUBMB Life (2009) 61:134–43. doi: 10.1002/iub.155

27. Xi L, Hess ML, Kukreja RC. Ischemic preconditioning in isolated perfused mouse heart: reduction in infarct size without improvement of post-ischemic ventricular function. Mol Cell Biochem. (1998) 186:69–77.

28. Kohut A, Patel N, Singh H. Comprehensive echocardiography assessment of the right ventricle in murine models. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. (2016) 24:229–38. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2016.24.3.229

29. Singh H, Lu R, Rodríguez PF, Wu Y, Bopassa JC, Stefani E, et al. Visualization and quantification of cardiac mitochondrial protein clusters with STED microscopy. Mitochondrion (2012) 12:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.09.004

30. Sato T, Saito T, Saegusa N, Nakaya H. Mitochondrial Ca2+-activated K+ channels in cardiac myocytes: a mechanism of the cardioprotective effect and modulation by protein kinase A. Circulation (2005) 111:198–203. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151099.15706.B1

31. Stumpner J, Lange M, Beck A, Smul TM, Lotz CA, Kehl F, et al. Desflurane-induced post-conditioning against myocardial infarction is mediated by calcium-activated potassium channels: role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Br J Anaesth. (2012) 108:594–601. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer496

32. Soltysinska E, Bentzen BH, Barthmes M, Hattel H, Thrush AB, Harper ME. KCNMA1 encoded cardiac BK channels afford protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e103402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103402

33. Díaz L, Meera P, Amigo J, Stefani E, Alvarez O, Toro L, et al. Role of the S4 segment in a voltage-dependent calcium-sensitive potassium (hSlo) channel. J Biol Chem. (1998) 273:32430–6.

34. Cao CM, Xia Q, Gao Q, Chen M, Wong TM. Calcium-activated potassium channel triggers cardioprotection of ischemic preconditioning. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2005) 312:644–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074476

35. Garlid AO, Jaburek M, Jacobs JP, Garlid KD. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: which ROS signals cardioprotection? Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol. (2013) 305:H960–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00858.2012

36. Tang XD, Garcia ML, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Reactive oxygen species impair Slo1 BK channel function by altering cysteine-mediated calcium sensing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2004) 11:171–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb725

37. Gaifullina AS, Yakovlev AV, Mustafina AN, Weiger TM, Hermann A, Sitdikova GF. Homocysteine augments BK channel activity and decreases exocytosis of secretory granules in rat GH3 cells. FEBS Lett. (2016) 590:3375–84. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12381

38. Stowe DF, Aldakkak M, Camara AK, Riess ML, Heinen A, Varadarajan SG, et al. Cardiac mitochondrial preconditioning by Big Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel opening requires superoxide radical generation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2016) 290:H434–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2005

39. Stowe DF, Yang M, Heisner JS, Camara AKS. Endogenous and agonist-induced opening of mitochondrial big versus small Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels on cardiac cell and mitochondrial protection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2017) 70:314–28. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000524

40. Saleh SN, Angermann JE, Sones WR, Leblanc N, Greenwood IA. Stimulation of Ca2+-gated Cl− currents by the calcium-dependent K+ channel modulators NS1619 [1,3-dihydro-1-[2-hydroxy-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2H-benzi midazol-2-one] and isopimaric acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2007) 321:1075–84. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118786

41. Park WS, Kang SH, Son YK, Kim N, Ko JH, Kim HK, et al. The mitochondrial Ca2+-activated K+ channel activator, NS 1619 inhibits L-type Ca2+ channels in rat ventricular myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2007) 362:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.057

42. Olesen SP, Munch E, Moldt P, Drejer J. Selective activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels by novel benzimidazolone. Eur J Pharmacol. (1994) 251:53–9.

43. Holland M, Langton PD, Standen NB, Boyle JP. Effects of the BKCa channel activator, NS1619, on rat cerebral artery smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. (1996) 117:119–29.

44. Cancherini DV, Queliconi BB, Kowaltowski AJ. Pharmacological and physiological stimuli do not promote Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel activity in isolated heart mitochondria. Cardiovasc Res. (2007) 73:720–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.035

45. Bentzen BH, Olesen SP, Ronn LC, Grunnet M. BK channel activators and their therapeutic perspectives. Front Physiol. (2014) 5:389. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00389

46. Aldakkak M, Stowe DF, Cheng Q, Kwok WM, Camara AK. Mitochondrial matrix K+ flux independent of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opening. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2010) 298:C530–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00468.2009

47. Testai L, Martelli A, Marino A, D'Antongiovanni V, Ciregia F, Giusti L, et al. The activation of mitochondrial BK potassium channels contributes to the protective effects of naringenin against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Pharmacol. (2013) 85:1634–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.018

48. Gáspár T, Domoki F, Lenti L, Katakam PV, Snipes JA, Bari F, et al. Immediate neuronal preconditioning by NS1619. Brain Res. (2009) 1285:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.008

49. Wrzosek A. The potassium channel opener NS1619 modulates calcium homeostasis in muscle cells by inhibiting SERCA. Cell Calcium (2014) 56:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.03.005

50. Kicinska A, Szewczyk A. Large-conductance potassium cation channel opener NS1619 inhibits cardiac mitochondria respiratory chain. Toxicol Mech Methods (1996) 14:59–61. doi: 10.1080/15376520490257482

51. Okazaki Y, Cao ZL, Ohtsubo S, Hamada M, Naito K, Rikitake K, et al. Leukocyte-depleted reperfusion after long cardioplegic arrest attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury of the coronary endothelium and myocardium in rabbit hearts. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2000) 18:90–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00436-x

52. Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, et al. Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol. (2011) 31:1309–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00911-10

53. Garlid KD, Costa AD, Quinlan CL, Pierre SV, Dos Santos P. Cardioprotective signaling to mitochondria. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2009) 46:858–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.019

54. Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:36027–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200

55. Sanz A. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: do they extend or shorten animal lifespan? Biochim Biophys Acta (2016) 1857:1116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.018

56. Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Sun X, Schindler PA. The mitochondrial KATP channel as a receptor for potassium channel openers. J Biol Chem. (1996) 271:8796–9.

57. Andrukhiv A, Costa AD, West IC, Garlid KD. Opening mitoKATP increases superoxide generation from complex I of the electron transport chain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2006) 291:H2067–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00272.2006

58. Stowe DF, Camara AK. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2009) 11:1373–414. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2008.2331

59. Booth DM, Enyedi B, Geiszt M, Varnai P, Hajnoczky G. Redox nanodomains are induced by and control calcium signaling at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell (2016) 63:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.040

60. Aldakkak M, Camara AK, Heisner JS, Yang M, Stowe DF. Ranolazine reduces Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress and improves mitochondrial integrity to protect against ischemia reperfusion injury in isolated hearts. Pharmacol Res. (2011) 64:381–92. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.06.018

61. Aldakkak M, Stowe DF, Chen Q, Lesnefsky EJ, Camara AK. Inhibited mitochondrial respiration by amobarbital during cardiac ischaemia improves redox state and reduces matrix Ca2+ overload and ROS release. Cardiovasc Res. (2008) 77:406–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.08.008

62. Heinen A, Camara AK, Aldakkak M, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Stowe DF. Mitochondrial Ca2+-induced K+ influx increases respiration and enhances ROS production while maintaining membrane potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2007) 292:C148–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2006

63. Wikstrom M, Saari H. A spectral shift in cytochrome a induced by calcium ions. Biochim Biophys Acta (1975) 408:170–9.

64. Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2004) 287:C817–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004

65. Ponnalagu D, Singh H. Anion channels of mitochondria. Handb Exp Pharmacol. (2017) 240:71–101. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_39

Keywords: cardiac mitochondria, BKCa channels, reactive oxygen species, ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, ischemic preconditioning

Citation: Goswami SK, Ponnalagu D, Hussain AT, Shah K, Karekar P, Gururaja Rao S, Meredith AL, Khan M and Singh H (2019) Expression and Activation of BKCa Channels in Mice Protects Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury of Isolated Hearts by Modulating Mitochondrial Function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 5:194. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00194

Received: 26 June 2018; Accepted: 18 December 2018;

Published: 28 January 2019.

Edited by:

Amadou K. S. Camara, Medical College of Wisconsin, United StatesReviewed by:

David F. Stowe, Medical College of Wisconsin, United StatesQun Chen, Virginia Commonwealth University, United States

Robert Lukowski, University of Tubingen, Germany

Copyright © 2019 Goswami, Ponnalagu, Hussain, Shah, Karekar, Gururaja Rao, Meredith, Khan and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Harpreet Singh, aGFycHJlZXQuc2luZ2hAb3N1bWMuZWR1

Sumanta Kumar Goswami1,2

Sumanta Kumar Goswami1,2 Andrea L. Meredith

Andrea L. Meredith Harpreet Singh

Harpreet Singh