- 1 Department of Art Design and Creative Industry, Nanfang College Guangzhou, Guanghzou, China

- 2 Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau, Macau, China

Given the current low level of public participation and limited channels of participation in Chinese urban planning. Social media has become an important platform for public participation in China. Taking the banyan tree relocation and felling incident in Guangzhou City as an example. This paper explores how social media-facilitated public participation can effectively influence urban planning decisions through case study and discourse power analysis. It is found that place attachment may serve as a significant motivator for public participation in urban planning. Social media plays a dual role in this process. On one hand, it can improve the effectiveness of public participation in urban planning and ultimately fulfil the role of advancing democratic government decision-making. On the other hand, the paper reveals challenges such as information homogenization, emotionalized communication, and elite dominance. These issues underscore the need for further improvements in regulatory mechanisms and technical support. Therefore, future urban planning policies should take people's emotions into account, and also need to accelerate the construction of improved systems, mechanisms and technologies for social media public participation to achieve high-level public participation goals.

1 Introduction

Public participation has always been an important part of the urban planning process, and although the Western planning literature has always emphasised the importance of civic engagement, the practice of participatory urban planning in China has been limited by institutional and social circumstances (Morrison and Xian, 2016a). However, the recent development of social media has introduced new dynamics to public participation in China, particularly in urban planning (Shao and Wang, 2017). These changes have moved public involvement beyond “resident participation” to “resident empowerment”, enabling greater public input into planning decisions traditionally led by the government (Yang et al., 2018). In this context, social media discourse has begun to influence urban policy-making. Despite these advancements, there remains a lack of research on the perception and use of online social media discourse in public participation. Specifically, limited attention has been given to understanding how social media discourse can promote government decision-making in urban renewal and a dearth of empirical studies exists in this area.

Research on public participation in urban planning in China has mainly focused on urban redevelopment and less on urban tree planning studies (Li and Liu, 2018). This gap is notable given the increasing spatial conflicts between early-planted urban trees and the rapid development of new buildings, roads and utilities. Resulting in these trees not being able to adapt to the current urban construction (Jim, 2003). The government had to replace some of the urban trees to accommodate the current urban development needs. The shaded environments created by urban trees provide residents with abundant green spaces. More importantly, urban trees also represent the culture and identity of a city, carrying historical significance. This fosters a deeper emotional attachment among residents, who regard these trees as an integral part of the city’s culture. Such cultural connections not only strengthen residents’ sense of identity with the city but also influence their desire for preservation. In this context, urban regeneration can change place attachment in traditional environments (Ujang and Zakariya, 2015). For instance, place attachment to familiar environments often makes residents more inclined to preserve their original surroundings, resisting environmental changes (Aalbers and Sehested, 2018). This phenomenon has triggered public participation in environmental protection actions, so it is particularly important to explore the public participation triggered based on place attachment. The paper on place attachment of individual urban trees is insufficient and lacks to explore the process of place attachment formation between people and urban trees.

As a vital component of Guangzhou’s natural environment, banyan trees embody a combination of historical and cultural significance, ecological functions, and social interaction spaces. Historically, since the 10th century, banyan trees have served as feng shui trees for worship and gatherings at temples and village entrances, carrying the emotional attachments of Guangzhou residents. Ecologically, their dense canopies provide shaded resting areas, improve the urban environment, and enhance residents’ quality of life (Bai and Li, 2024). Socially, banyan tree spaces represent the street culture of South China, serving as key venues for interaction and communication, while bearing collective memory and cultural identity. In the process of urbanization, these spaces have faced threats of deforestation, triggering residents to express dissatisfaction through social movements, which ultimately led the government to take accountability and amend relevant laws.

Therefore, this paper is based on the government’s decision to cut down and relocate banyan trees as part of the Guangzhou Municipal Government’s urban landscape optimisation policy in China, which provoked significant triggered dissatisfaction. Residents expressed their feelings towards the banyan trees and opposed the government’s decision through social media, effectively mobilising public participation to protect these trees. Their actions eventually influenced the public participation policy to urban planning. This case paper aims to achieve the following: Firstly, explore the special mode of public participation in urban planning activities at the current stage in China. Secondly, based on the ambivalence analysis of public participation in the banyan tree incident in Guangzhou, it proposes that place attachment is an important influencing factor for residents’ participation in public engagement. Finally, it explores how public participation fuelled by social media can effectively influence urban planning decisions. Using a case study methodology, the paper evaluates public participation in the Guangzhou Banyan Tree Incident, focusing on the policy frameworks, participation processes and the use of social media discourse. And through discourse analysis (Hajer and Versteeg, 2005), discussing how social media is used for public engagement and expressing emotions.

2 Methods

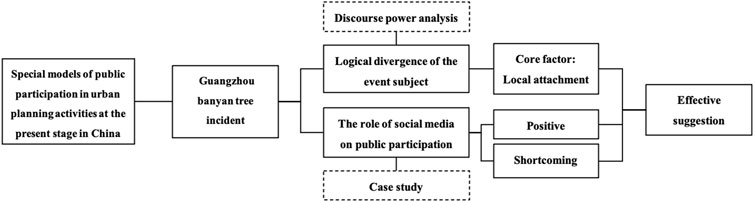

This paper primarily employs case study and discourse power analysis methodologies. Using the relocation and felling of banyan trees in Guangzhou as an example. Through an analysis of the contradictions in public participation, it explores how social media-facilitated public engagement can effectively influence urban planning decisions (Figure 1).

Firstly, the study examines the unique model of public participation in urban planning in contemporary China. While public participation procedures have been formalized in urban governance. The lack of effective public involvement continues to impact social stability. It led to the focal event of this research—the Guangzhou banyan tree incident.

Secondly, using discourse power analysis, the study investigates the logical discrepancies between the government and residents involved in the event. Based on a summary of public participation in the Guangzhou banyan tree incident. It identifies the core factor driving the event’s escalation: place attachment. By analyzing differences in the perceived value of protection and public engagement. The discourse power analysis focuses on identity and textual content to summarize the logical demands of various groups.

Finally, through a case study approach, the study examines the role of social media in public participation (Bai et al., 2024a). The Guangzhou banyan tree case is analyzed to understand the process of social media-driven public engagement and the influence of place attachment in this context. This provides a nuanced perspective on the role of social media in public participation by summarizing both its strengths and shortcomings, along with offering practical and effective recommendations.

3 Special models of public participation in urban planning activities at the present stage in China

Public participation is a form of government governance that demonstrates inclusiveness in urban planning decision-making processes (Farinosi et al., 2019). It involves refers to the participation of residents, relevant interest groups and professionals. Public participation means that residents, relevant interest groups and professionals (Zhao et al., 2022), through proposals, communications, inquiries, hearings and online discourse (Zhou et al., 2021). As urban areas evolve, public participation plays an important role in the pre-study, planning and design, management and maintenance phases of urban landscape regeneration (Deng and Wang, 2019). However, at present, public participation in urban renewal plays an important role in China. Despite its growing significance, the current public participation in urban planning activities in China is a mode of participation to avoid conflicts. The purpose of public participation is to follow government decisions and to justify them, not to consult public opinion (Tang et al., 2021). Therefore, even though public participation procedures have been standardised in the process of urban governance in China, the limited involvement of the public often still lead to social stability and unresolved tensions.

3.1 Limitations of public participation

Public participation is positive for the sustainable development of urban planning, as it allows the masses to participate in specific planning, thereby increasing social cohesion (Amado et al., 2010). However, in China it has not yet been fully realised. At present, the right to public participation belongs to a small group of people and expert representatives. While the vast majority of the masses do not have the means or rights to participate. As urban planning, urban residents should have equal participation rights. However, in China, experts are assumed to be the most knowledgeable public about the project. Experts have long been representatives of public participation in urban planning, but they are limited to providing opinions and it is unknown whether they will be adopted (Morrison and Xian, 2016b). Therefore, the participation mode of the general public is basically a low-level form of participation with the right to know. This approach fails to promote social cohesion urban development and may even exacerbate societal conflicts.

3.2 Social media fuelling public engagement

Since the age of the Internet, with the rise of various social media such as microblogs and WeChat in China, public participation has also begun to use social media. Compared to the limitations of traditional public participation, social media has several advantages. First, it enables the freedom of speech of ordinary citizens and builds new network relationships (Lin, 2022). Citizens can support or refute government decisions on open platforms and exchange views rapidly through functions such as online groups and topic groups. And forming a strong interactive relationship. And in such frequent exchanges, they continue to merge and split, holding together to form different interest and opinion groups (Niu and Dong, 2017). Social media has the ability to spread quickly. Secondly, social media has the characteristics of fast dissemination speed, wide access to information and large influence. It offers real-time dissemination of information, enabling the formation of public discussion topics. These discussions may be introduced invisibly and amplify the topic’s visibility and impact (Ye et al., 2017). For example, on social media, each individual can act as a self-media platform. Personal posts, once shared, commented on, or widely discussed, can lead to large-scale discussion. Especially in China’s context, the “elite group”, “celebrity effect” and “acquaintance effect” further magnify this collective power, may increase the influence of the event itself. Third, social media allows for anonymous and has a low barrier to entry. It crosses social, economic, and political boundaries and reduces the burden of pressure on speech. While social media has the obvious advantage that it fuels the breadth of residents’ public participation. But at present, the most important reason for Chinese residents to choose social media for public participation is still that the public and the government have not achieved real two-way communication (Buijs et al., 2019) This is also the reason why residents use social media to conduct collective large-scale online cyber actions to call for policy optimisation (Wu and Lin, 2018). Given these dynamics, it is crucial to focus on the origins behind social media public participation.

3.3 Place attachment triggers public participation in urban planning

Place attachment refers to the positive emotional connection between people and places. This emotion is the individual’s identification with and attachment to the place. In urban planning, place attachment is currently an important theoretical basis and measurement index for studying the emotional relationship between people and the environment, and exploring the attachment emotion between residents and the landscape. Scannell and Gifford proposed that place attachment can be divided into social attributes and physical environmental attributes. Social attributes include social relationships and a sense of security, while physical environmental attributes encompass the inherent characteristics of the environment (Scannell and Gifford, 2010). In urban planning, urban trees can provide residents with spaces for daily activities, facilitating the development of stable social relationships. Their natural features also play a critical role in enhancing the aesthetic quality of the environment and offering recreational functions. Therefore, it plays an important role in place attachment. Such as environmental feature creation (Wu and Lin, 2018), behavioural decision-making (Wang and Xiang, 2020), managing local affairs (Kuo et al., 2021), formation of pro-environmental behaviour (Budruk et al., 2009), urban landscape aesthetics (Jaśkiewicz, 2015) and urban regeneration.

Place attachment is a condition for residents to be concerned about environmental change (Chapin et al., 2012) and a prerequisite for triggering public participation. First, place attachment can motivate residents to protect the urban landscape (Fornara et al., 2020). This is because such landscapes record their specific culture, history, and identity symbols (Manzo and Perkins, 2006). Second, place attachment shapes public participation in decision-making by internalising shared values. When an individual identifies with the group’s perceptions, they feel a sense of belonging and thus participates in the same values and interests collective activities (Chang et al., 2022). Third, place attachment reflects the attitude of public participation. It reveals the relationship between identity and rights (Lewicka, 2011). The importance of identity and rights will make them pay more attention to whether they have the right to participate in or decide on things. It can represent their own identity and symbols. Fourth, the irreplaceability of the urban historic landscape strengthens the strength of public participation (Kaltenborn and Bjerke, 2002). The Chinese Feng Shui “qi” and the Western “spirit of place” have some intrinsic connection (Yu, 2021). Chinese feng shui “qi” and western “spirit of place” have some intrinsic connection. Historic landscapes can reflect collective memory, cultural bonds and emotional identity (Lo and Jim, 2015a). While can trigger environmental awareness and attitudes (Cheung and Hui, 2018). Thus, public participation triggered by place attachment is influenced by many factors and is a dynamic process.

4 The public participation debate in the Guangzhou banyan tree incident

4.1 Background to the Guangzhou banyan tree incident

Guangzhou is a city with more than 2,000 years of history and culture. On 15 February 1921, Guangzhou was founded. It developed from the original city and was the first established city in Chinese history. The city’s current administrative division is divided into 11 districts. Three old urban districts among them have mostly preserved traditional Lingnan cultural relics, historical buildings and old trees. According to the Guangzhou Greening Statistics 2021, Guangzhou has 9,873 registered old and valuable trees. Of which more than 2,000 are banyan trees, accounting for 20 per cent of the total. Banyan trees in Guangzhou are mainly distributed around streets, villages, parks, temples and old neighbourhoods (Zhang J. et al., 2020). It has witnessed the development and transformation of Guangzhou city.

Guangzhou, as one of the most rapidly urbanising cities in China, has been implementing urban renewal practices since 2000. Subsequently, Guangzhou implemented the “Road Greening Quality Improvement” and “City Park Renovation and Upgrading” projects in order to create a forested city. The goals are to protect biodiversity, promote harmony between human beings and nature, and enhance the city’s taste. The government’s decision to cut down banyan trees and replace them with phoenix trees. And lawns is a planning decision that will expand the area of green space in the city, make the city’s roads smoother and make the urban environment more aesthetically pleasing. All with the aim of creating an environmentally friendly city.

However, in Guangzhou, this series of urban renewal projects has challenged the survival space of banyan trees. Specifically, firstly, the chaotic layout of banyan trees is an object of optimisation and renewal in old districts. Early planted banyan trees are distributed in the shanty towns and old districts in Guangzhou’s old city. Due to the lack of reasonable layout, the banyan trees are too close to the residential buildings. Blocking the light of the houses, bringing in a large number of mosquitoes and destroying the roads in the districts (Cui, 2016). Guangzhou’s “Three Olds” policy is aimed at upgrading and optimising the layout of these unreasonable old districts. This will inevitably lead to the felling and replanting of banyan trees. Secondly, the use of banyan trees as roads is not in line with the indicators of forest city construction. According to the National Forest City Evaluation Indicators, one tree in the city should not exceed 20% of the total number of trees. While in Guangzhou, the number of banyan trees is 276,200, which accounts for as much as 47.13% of the overall tree species. It is a serious exceeding of the indicator regulations. Thirdly, the banyan tree in urban parks is the object of relocation of the policy of dense trees and sparse atmospheric urban parks. Taking Guangzhou People’s Park as an example, 213 trees were removed and replaced with green space during the urban renewal process, including 60 ficus trees.

Banyan trees seem to have many shortcomings as urban trees. And they are difficult to adapt to Guangzhou’s urban development. So the Guangzhou government decided to cut down and relocate the banyan trees in the city. However, when the banyan trees were cut down and relocated for planting in large numbers, the local people expressed their strong dissatisfaction. And they erupted into a large-scale action on social media to protect the banyan trees. Some kept posting questions online. Some went to the gardening authorities to write letters. Some complained to higher authorities. And some reflected to the central government through specific channels. A garden expert said bitterly, “This is an ecological havoc and ecological disaster for the city.” Veteran media person Zhuang Shenzhi shouted at the relevant departments on a self-media platform: “You are ‘legal’, but you are ‘committing a crime’! You are chopping and digging up the roots of Guangzhou’s urban culture.” A resident posted a nostalgic article about the banyan tree and initiated a “tree-hugging” activity, which swept the local network and was read by over 100,000 people in a short period of time. The Guangdong Association for the Promotion of Environmental Education also conducted a questionnaire survey on “What do you think of the banyan tree” through its official public website. According to statistics, 94 per cent of the participants expressed support for the use of banyan trees as street trees and opposition to the government’s “Banyan Tree” campaign.

In order to respond to the public’s voice of doubt, but also for their own behaviour. Guangzhou Municipal Forestry and Landscape Architecture Bureau issued a situation note, listed the banyan tree “four sins”. But public opinion did not stop there. After much consultation and discussion, the Guangzhou Municipal Government admitted in the symposium that part of the work was not done properly. And the lack of participation of residents. However, the Guangzhou residents were still angry and reported the incident to the central government through special channels. Eventually the top leaders gave important instructions on the matter, criticising the felling of the banyan tree. It was pointed out that the incident had damaged the city’s natural ecological environment and historical and cultural landscape. Hurt the people’s fond memories and deep feelings towards the city. It is a typical destructive “construction” behaviour that has caused significant negative impacts and irreversible losses. More than 10 important Guangzhou officials have been held accountable.

4.2 Logical differences between the government and residents in the Guangzhou banyan tree incident

4.2.1 Logical differences in protection values

In this controversial incident, there is actually a difference in viewpoints between the Government and the residents. Firstly, there is a logical difference in the value of protection. In fact, as early as 1,304, the Hainan Chronicle recorded the fine-leaved banyan tree in Guangzhou. It is regarded as a sacred tree of Buddhism. And in Guangzhou, the Six Banyan Temple, an old Buddhist temple, was named after the six banyan trees in the temple. The ancient banyan tree at Guangzhou Guangxiao Temple is the oldest banyan tree in the country. Most of the banyan trees throughout the country were introduced from here (Luo and Zhuang, 2004). There is also a saying in Cantonese folklore that “where there are many banyan trees, the land will flourish”. Villagers in Guangdong prefer to plant banyan trees at the entrance of their villages. It is also known as “feng shui tree” as it is a symbol of good luck and prosperity. As time changes, the banyan tree has become a living witness or symbol of the development of ancient villages, condensing nostalgia (Yang, 2019). Therefore, the banyan tree is full of historical significance and sacred symbols for the people of Guangzhou.

4.2.1.1 Logic of government: scientific and rational view of the banyan tree

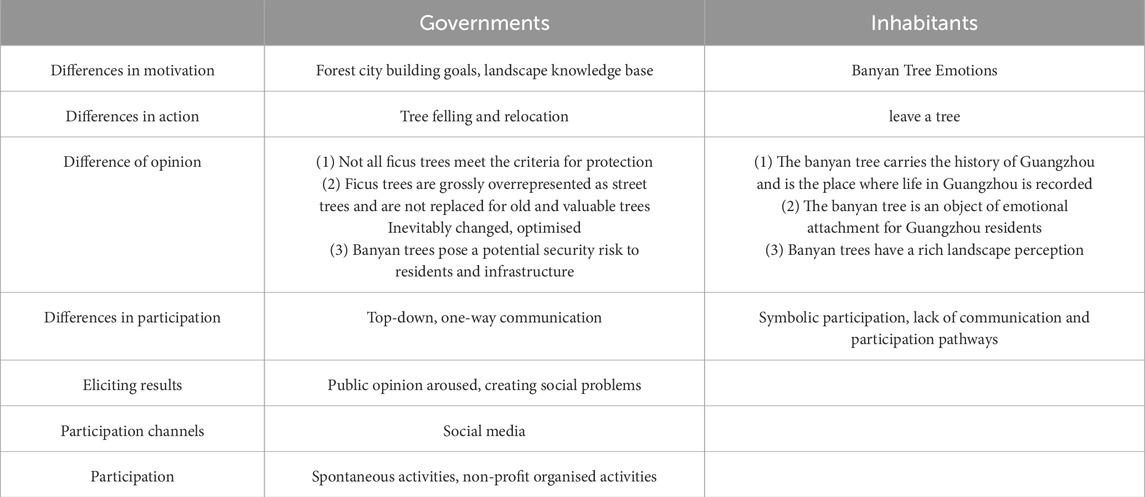

However, from the Government’s logic, it seems that whether banyan trees should be preserved should also be viewed rationally.

Firstly, not all banyan trees meet the criteria for preservation. Banyan trees as spiritual symbols refer to those in traditional villages and temples, which are endowed with historical value. However, most of the banyan trees in Guangzhou are roadside trees. Not banyan trees at the entrance of villages and temples, which symbolise “nostalgia” and “spirituality”. Therefore, most of the banyan trees belonging to the roadside trees do not meet the criteria for protection. And there is no uniform standard for the protection of banyan trees (Table 1).

Secondly, the number of banyan trees as roadside trees in Guangzhou has seriously exceeded the target. And no replacement of old and valuable trees has been carried out. According to the National Forest City Evaluation Indicators, the number of banyan trees in Guangzhou has seriously exceeded the target. Moreover, the replacement of tree species has been carried out in strict accordance with the National Forest City Evaluation Indicators. The urban greening optimisation and upgrading project has been implemented on the principle of conservation (Table 1).

Thirdly, banyan trees pose potential safety risks to residents and infrastructure. Analysed over time, in 1926 Guangzhou’s roadside banyan trees were planted on the principle of “convenience, aesthetics and cost saving” (Li and Yang, 2016). At that time, there was no experience in the planting of roadside trees in China. And in Guangzhou the road construction and planting of roadside trees was a precedent for the modernisation of Chinese cities. However, with the development of the city, the problems of the banyan tree are gradually exposed. They are also not entirely suitable for the construction of Guangzhou city. At the same time, the Guangzhou Municipal Bureau of Landscape Architecture also pointed out some problems. Such as the existence of safety hazards, tree crowns and road space competition, some narrow road trees blocking, interfering with street buildings, affecting the lighting and safety of the houses, the root system of the crowded pedestrian and vehicular space, damage to pavements and underground pipelines (Table 1).

As a result, the Guangzhou government does not consider most of the banyan trees in Guangzhou to be of historical significance. Especially those along the Pearl River that were the focus of attention in the Guangzhou banyan tree incident. For the urban street trees in the entire old city, the beautification and environmental optimisation value is greater than the historical environmental value according to the priority (Table 1).

4.2.1.2 Resident logic: the banyan tree is a symbol of place attachment

For the residents of Guangzhou, the logic of its conservation value is equally threefold.

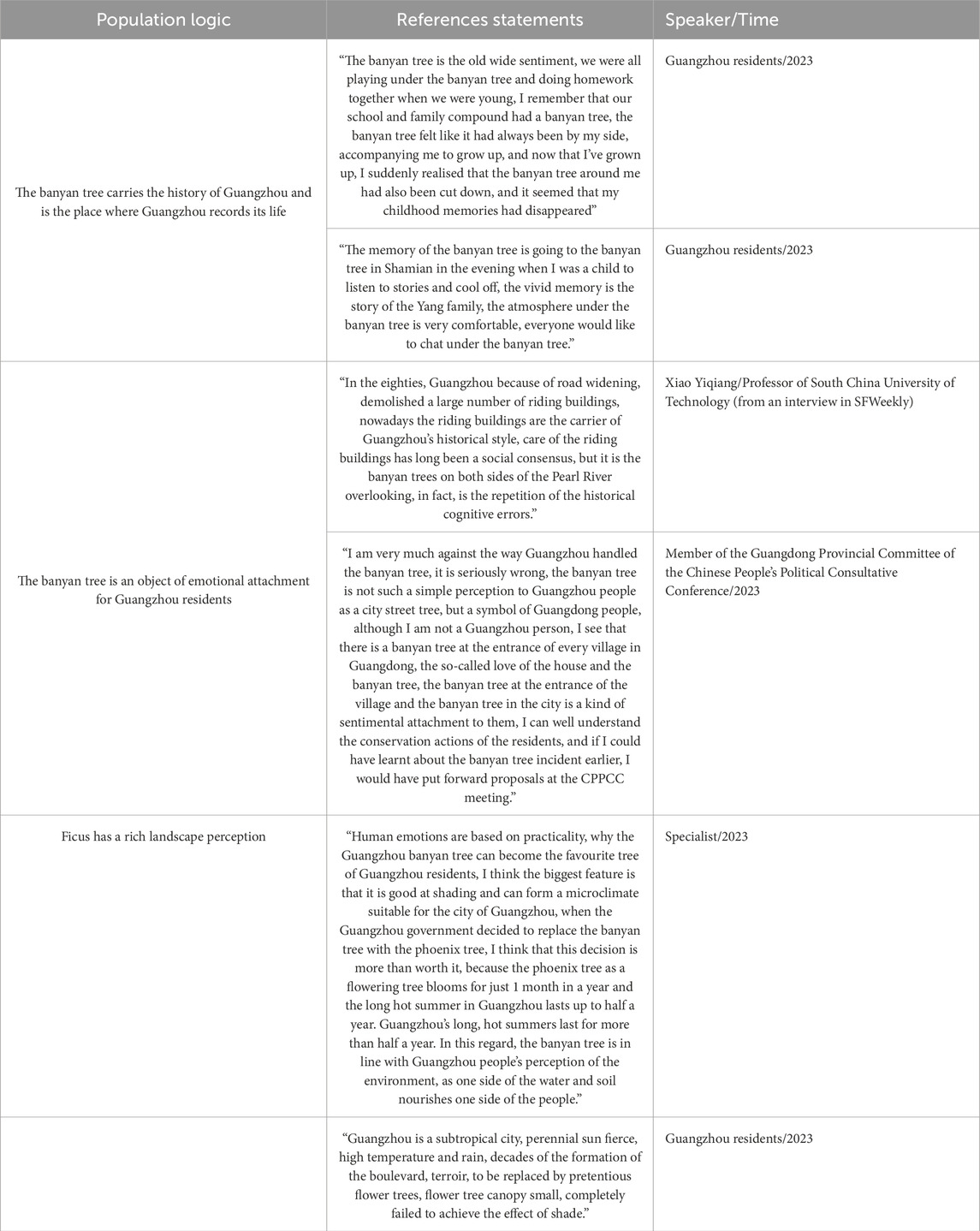

Firstly, the banyan tree carries the history of Guangzhou and is the place where Guangzhou records its life. The “banyan tree complex” of Lingnan people can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty. At the end of the Tang Dynasty, Lingnan people planted banyan trees in front of and behind their houses. At the base of the ponds along the roads, along the banks of the Shashui River, which became a spectacular sight in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. And scholars such as Soini have also suggested that the residents’ place attachment was influenced by social ties, social bonds and a sense of place (Soini et al., 2012). The large and dense canopy of banyan trees in modern Guangzhou is a place for Guangzhou residents to cool off. Especially in the past when there was no air-conditioning, the banyan trees accompanied a group of Guangzhou residents through their childhood, middle age and old age. At the same time, the “Banyan Tree Head” space formed under the banyan trees is a unique synonym for street culture and residents’ lives in South China. And a temporary stronghold for pedestrians to stop by at the end of the streets and alleys, as well as a traditional community centre (Table 2). Therefore, banyan trees reflect the contrasting living environments of the past and present, serving as a bridge for dialogue between history and modernity.

Secondly, the banyan tree is an object of emotional attachment for Guangzhou residents. Milton suggested that trees are living entities and are often personified as a source of spiritual solace (Milton, 2003). Their capacity to provide comfort makes people feel that nature is a friend, fostering dialogues between humans and nature, which ultimately leads to nature attachment (Phillips and Atchison, 2020). For the people of Guangzhou, banyan trees serve as emotional anchors. Because the preservation of the banyan tree is a sign of respect for the shared history, culture and memory. The banyan trees constitute a landscape that is historical and cultural in nature. Von Wirth argues that major changes in the urban environment can challenge residents’ wellbeing and attachment to place, also can lead to resentment of environmental change (von Wirth et al., 2016). He argues that major changes in the urban environment can challenge residents’ wellbeing and place attachment. While it can lead to resentment of environmental change (Kuo et al., 2021). The felling of banyan trees alters local residents’ attachment to the environment, the continuation of cultural memory. While stimulating pro-environmental behaviour (Chen et al., 2021) and resistance to place-related changes (Fornara et al., 2020). The felling of banyan trees changes local people’s dependence on the environment, perpetuates cultural memory, stimulates pro-environmental behaviour and resists place-related changes (Table 2).

Thirdly, banyan trees have a rich landscape perception. From the perspective of environmental perception, landscape perception refers to the aesthetic and use values of the environment. Landscape perceptions of trees include reducing the greenhouse effect, providing shade, rainwater management and aesthetic optimisation of the environment (Soini et al., 2012). Banyan trees have a peculiar tree form, luxuriant branches and leaves, huge crowns and very tenacious vitality. In the old city of Guangzhou, lush, green and shade-covered banyan landscapes can be seen everywhere, bringing the city a gardened space to enjoy (Li et al., 2021). Guangzhou residents are also emotionally attached to the banyan tree because it meets the hot climate environment of Guangzhou. Residents also rely on the shade space formed by the banyan tree. At the same time, identify with the banyan tree space in the city as the most suitable boulevard in Guangzhou. This kind of dependence and identification is exactly the classical two-dimensional structure of place attachment - place dependence and place identification (Table 2).

As a result, Guangzhou residents believe that the banyan tree is a place that carries history, records life and provides emotional support and enrichment of perceptions. And it should not be cut down entirely. The residents have a deep attachment to the banyan trees in Guangzhou.

4.2.2 Logical differences in public participation

4.2.2.1 Government logic: scientifically sound public participation

In terms of the methods of public participation, according to the Urban and Rural Planning Law and other relevant regulations. In China, the methods of public participation in urban planning include two main categories: public announcements and consultation. At present, in the decision-making process of various types of planning, the main forms of participation are announcements. Expert demonstration meetings and symposiums. Currently, there are also many laws and regulations that provide institutional protection for public participation (Weng, 2020). By checking the official website of the Guangzhou Forestry and Landscape Bureau, it can be seen the government has made public the information on the greening relocation and felling construction plan, the relocation and felling list and the resolution of administrative licensing, etc. And set up the relevant public notices on the site. This is a completely legal and compliant process.

On the other hand, at present, the cognitive level and maturity of the main body of public participation are not high in China. Only when the participating representatives have certain sensitivity and relevant knowledge can they really play a role in participating in planning decision-making (Yang et al., 2019). The public can only really participate in planning decision-making if the representatives have certain sensitivity and relevant knowledge. However, the vast majority of the public objectively lacks the knowledge, decision-making ability, information resources and reliable ways to effectively participate in urban planning. Even if they are willing to participate in urban planning and construction. It is difficult for them to have the motivation to speak out for the public interest rather than just for their own personal interests. As Kowalik argues, some of the social media postings of public participation are merely emotional outbursts. Rather than genuine participation in the discussion of events (Kowalik, 2021). Therefore, public participation in China is currently more appropriate for a lower level of top-down participation (Table 3).

Table 3. Logical differences between the government and residents in the Guangzhou banyan tree incident.

4.2.2.2 Resident logic: ineffective public participation

Currently, China’s mechanism for public participation in urban planning is still predominantly crude and needs to be refined. It is still based on announcements. There is a lack of targeted participation mechanisms for different groups of the public. According to the eight levels of the “ladder of public participation” proposed by Arnstein, it can be seen that most of the public participation in China stays at the level of “consultative participation”. It is only a symbolic participation. As far as the public is concerned, it is very difficult for public participation to influence planning decisions. Even if there is a public notice, it is only a symbolic administrative act after the planning decision is made.

Furthermore, public participation in urban planning is through representative selection mechanisms, which currently face problems of insufficient disclosure and low public awareness. It fail to improve the representativeness of public participation. Darga shows that participation in decision-making is not only managerial, but also political. That all citizens have the right to have a say in urban change (Dargan, 2009). Especially in the renewal of cultural and natural landscapes and historical sites, there is a need to understand the public’s ideas, values and interests (Jones, 2007).

It can be seen that Guangzhou residents believe that during the consultation stage of urban tree felling. The government only communicates in a one-way top-down manner. And the residents did not participate in the discussion of the banyan tree incident (Reed et al., 2018). The residents did not participate in the discussion of the banyan tree incident. Real public participation was not realised (Table 3).

5 The role of social media on public participation

5.1 Analysis of the public participation process fuelled by social media

Based on the development of public participation in social media, this paper broadly divides the social media participation process of the Guangzhou Banyan Tree incident into three stages:

5.1.1 Karmic empathy stage

The banyan trees evoke a sense of shared resonance among residents through place attachment. Under the policy of “Guangzhou National Forest City Quality Enhancement Construction”, the Guangzhou government initiated the cutting down and relocation of banyan trees. During period a number of banyan trees were cut down in the streets of Guangzhou. Residents, who frequently engaged in activities under the banyan trees, noticed the decline of these familiar urban trees, which drew their attention. In addition, on 23 December 2020, the Construction and Water Affairs Bureau of Yuexiu District approved the relocation of banyan trees from People’s Park. Many of these banyan trees in People’s Park are centuries-old heritage trees. The series of government actions involving the large-scale felling and relocation of banyan trees disrupted residents’ sense of familiarity with the local environment. They lamented the decline of the banyan trees, the destruction of trees that had witnessed the city’s history, and the loss of their familiar leisure and cooling spaces. This exacerbated residents’ dissatisfaction with the ongoing removal of banyan trees.

5.1.2 Social media engagement phase

As more and more residents are unhappy with the felling of the banyan tree, individuals and organisations have begun to engage, appeal and spread the word through social media. Some launched the “Embrace the Banyan Tree in Guangzhou” campaign, leveraging the emotional bond between people and trees to raise awareness about the banyan tree felling incident. This campaign triggered extensive reposts and comments. Others using public accounts to explain Guangzhou’s policies and regulations on the felling and relocation of banyan trees, as well as the feelings of Guangzhou residents towards banyan trees. On one hand, this approach overcame spatial and temporal constraints, achieving rapid dissemination and drawing greater public attention to the banyan tree issue. On the other hand, it provided platforms for people to voice their opinions, guiding the public to express their attachment to the banyan trees. Furthermore, the Guangdong Association for the Promotion of Environmental Education also released a questionnaire on “Your Views on Banyan Trees” on its official public number, collecting over 40,000 responses. They worked with professional groups to develop standardized participation frameworks and guided public involvement, ultimately producing statistical data. Subsequently, professional media outlets joined the discussion. Sanlian Life Weekly also published an article on Guangzhou’s banyan tree sentiment and the banyan tree incident. As well as interviews with self-published media bloggers, industry experts and scholars. The story was read more than 100,000 times online and sparked a nationwide discussion involving netizens.

As a result of the growing influence and public pressure, the Government has continued to respond to and explain the matter. It communicated with residents on the relocation of the banyan tree by issuing an information note, posting a thematic consultation on the online interactive exchange platform, holding a thematic symposium and holding a leadership interview day. After repeated co-ordination and consultation, the Government changed its initial decision on the matter. They stating the tree would not be cut down again and public opinion would be fully consulted.

This stage reflects the fact social media participation is guided by the professional power of self-published media, environmental organisations and the media. On the one hand, these groups professionally and effectively buttressed netizens’ emotional expression of the banyan tree. While they paid more sustained and wider attention to the Guangzhou banyan tree incident through social media. On the other hand, public participation in social media influenced the government’s relevant decisions. For this incident, the government went from explaining the policy, to explaining the incident, to emphasising the policy decision not to cut down any more trees. It reflecting the effectiveness of social media participation in this incident.

5.1.3 Policy optimisation phase

In the end, both the State and the Government made statements on the incident. Under growing public influence and mounting pressure from public opinion, the government responded by providing explanations and updates on the issue. Communication efforts included releasing official updates, hosting thematic consultations on online interactive platforms, organizing specialized forums, and holding leadership meet-and-greet events to engage with residents regarding the relocation of banyan trees. After repeated coordination and negotiations, the government reversed its initial decision, announcing that no more trees would be felled and committing to fully consider public opinion. Ultimately, both national and local authorities issued statements on the incident. The National Supervisory Commission of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) criticised the banyan tree incident, prompting the Guangzhou Municipal Government to propose solutions for addressing the banyan tree problem. Additionally, the Guangzhou Forestry Bureau issued a policy document regulating the management of urban trees. Not only did the incident end up with a completely different outcome from the government’s initial decision. But it also contributed to the improvement of the relevant norms and policies.

The incident not only resulted in outcomes entirely different from the government’s original decision but also led to improvements in related regulations and policies. Throughout this process, the government’s progression from explaining policies, to clarifying events, and finally emphasizing its revised decision not to fell trees highlighted the effectiveness of social media participation in shaping this outcome. The public participation of social media has played a clear role in promoting the optimisation of policies related to urban trees. This reflects the Chinese government’s goal of improving urban planning, construction and governance. It also reflects that public participation in urban planning can be carried out more systematically and deeply with the help of social media.

5.2 The influence of local attachment in the process of public participation

First, place attachment can drive individuals to more actively engage in activities aimed at protecting urban trees. In traditional Chinese culture, trees have long been regarded as symbols of spiritual pursuit, reflecting the sense of belonging bestowed by nature. When individuals develop a deep emotional attachment to a place, they are more likely to take action to protect and maintain that place (Lo and Jim, 2015c). As a historical and cultural symbol of Guangzhou, the banyan tree easily evokes emotional resonance among residents. When social media initiates related campaigns, this emotional connection further enhances residents’ willingness to express their views and engage in protection efforts. Moreover, an important factor influencing place attachment is social relationships. “Friend circles” on social media are an extension of these relationships, significantly increasing the likelihood of public participation.

Second, in China, speech on social media is subject to a certain degree of regulation. Especially on topics might affect social stability and national security (Chen and Zhang, 2011). However, emotional expressions are not typically within the scope of stringent controls. The public takes advantage of the freedom to express emotions on social media to participate in discussions about urban management and voice their opinions. Thus advancing the process of public engagement.

Third, urban trees, as public resources, offer ecological benefits equitably to all residents, making it easier for them to recognize their value and actively engage in conservation efforts. Social media, as an open platform for public participation, provides a convenient channel for residents to express their opinions and emotions. In discussions on public topics such as urban tree conservation, residents can quickly generate resonance by sharing their views and demands through social media.

Finally, place attachment can offer a platform for public discussion, bringing together groups with similar perceptions and focusing public attention on specific issues, leading to a collective discussion effect. The public discussion triggered by place attachment builds a bridge for the dissemination and acquisition of information, deepening the group’s understanding of the issue at hand and strengthening their willingness to take action and participate (Halla and Laine, 2022a).

Furthermore, place attachment promotes the accumulation of social capital (Zhu and Fu, 2017a). Including trust, networks and norms. It form the foundation for collective action. When people feel emotionally attached to a shared place, they are more inclined to unite and collaborate for the wellbeing and protection of that place. Online discussions lower the barriers to participation, attracting more people to join collective actions for place protection. Therefore, the combination of emotional drive from place attachment with social media platforms stimulates public participation in urban tree conservation, driving collective action and promoting ecological preservation.

5.3 Positive aspects of social media engagement

However, the role and significance of social media in this incident is worth exploring at a deeper level. Its positive effects are very obvious. Social media has undoubtedly played a positive role in expanding the mode of public participation, diversifying the subjects and extending the level. At the same time, social media participation in the Guangzhou Banyan Tree Incident also has the positive significance. Such as enlightening the general public, triggering academic thinking and promoting democratic decision-making by the government and optimising urban planning policies.

First, place attachment drives individuals to participate more actively in activities aimed at protecting urban trees. In Chinese traditional culture, trees have long been regarded as symbols of spiritual aspiration, reflecting a sense of belonging endowed by nature. When people develop strong emotional attachments to a place, they are more likely to take action to protect and preserve it (Lo and Jim, 2015b). As a historical and cultural symbol of Guangzhou, banyan trees readily evoke emotional resonance among residents. When related activities are initiated on social media, this emotional identification further strengthens residents’ willingness to express opinions and engage in protective actions. Additionally, a significant factor influencing place attachment is social relationships, and the “friend circle” on social media serves as an extension of these relationships, significantly enhancing the likelihood of public participation.

Second, in China, social media discourse is subject to a certain degree of regulation (Chen and Zhang, 2011). Particularly concerning topics that could impact social stability or national security. However, expressions of emotion are not strictly controlled. The public leverages the relative freedom to express emotions on social media to participate in discussions about urban management and voice their opinions, thereby advancing the process of public participation (Afzalan and Muller, 2014).

Third, as public resources, urban trees provide ecological benefits equitably to all, making it easier for residents to recognize their value and actively engage in protection efforts (Zhang L. et al., 2020). Social media, as an open platform for public participation, facilitates the expression of opinions and emotions. In public topics such as urban tree conservation, residents use social media to share their views and demands, quickly eliciting widespread resonance (Friedmann, 2005).

Fourth, place attachment provides a shared cognitive platform for groups, creating an online, open space for discussion that focuses public participation and generates a clustering effect. The open discussions spurred by place attachment build a bridge for disseminating and acquiring information, deepening group understanding of related issues and strengthening their motivation and willingness to act (Halla and Laine, 2022b).

Finally, place attachment fosters the accumulation of social capital (Zhu and Fu, 2017b). Including trust, networks and norm. They are essential for collective action. When people share an emotional connection to a place, they are more inclined to collaborate and contribute to its welfare and protection. Online discussions lower the barriers to participation, attracting more individuals to collective actions aimed at preserving places. Therefore, the combination of emotion-driven place attachment and social media platforms stimulates public willingness to participate in urban tree protection, facilitating collective action and ecological conservation.

5.4 Shortcomings and reflections on social media engagement

At the same time, there are shortcomings in the process of social media engagement. The power of “social elites” in social media may have a narrow group mentality. The “social elite” includes various professionals, local academics and environmental organisations. They play a major role in online public participation (Zhao et al., 2018). Additionally, some social media users are not private individuals but representatives of organizations, institutions, businesses, public figures, or influential groups (Marwick and boyd, 2011). These users often craft tailored comments to reach and influence a large audience, sometimes driven by personal interests such as increasing their follower count. This indicates that the data generated on such platforms may be shaped by public relations teams or external communication managers, who might predefine the narrative direction of trending topics.

Moreover, a specific group mentality prevalent in online communities can further shape participation. Even “social elites” may exhibit this mindset, which manifests as a form of narrow group behavior. Participants may genuinely wish to engage in environmental protection activities but might hesitate to voice differing opinions for fear of rejection by their peers. Instead, they are inclined to share statements they believe will resonate with the majority. This collective mentality can undermine the diversity and authenticity of public participation, limiting the representation of varied perspectives in public discourse.

The extensive nature of social media needs to be urgently channelled. Under the realistic conditions of general immaturity of public participation subjects, China also faces irrational destruction of discourse and behaviour. Users tend to prioritize sharing intense and extreme emotional responses while overlooking deeper, more nuanced emotions. This tendency can contribute to heightened emotional polarization, particularly when addressing sensitive issues involving personal interests. Emotions such as anger and disgust are especially prone to rapid activation and widespread dissemination in these contexts. This also makes netizens’ discourse and responsibility unequal. Expression and venting are prone to go in the direction of bigotry and irrationality (Yu, 2013). At the same time, the subjects of public participation are fragmented. With the potential for multiple divergences in their values and cognitive abilities to perceive events. Discourse expression often pursues emotional expression rather than factual truth, resulting in relatively less rational discussion. And they do not have the capacity to hold an institutionalized approach to particular events.

Social media platforms face significant challenges in regulation. Algorithms designed with emotional learning and filtering mechanisms can amplify negative emotions, often prioritizing content that aligns with users’ existing negative feelings, which in turn deepens their emotional experiences (Martí et al., 2019). Furthermore, personalized recommendation algorithms frequently expose users to information that reinforces their own viewpoints, leading to information homogenization and the formation of “echo chambers.” These dynamics intensify divisions between groups and heighten emotional polarization. Striking a balance between content regulation and freedom of speech poses a complex dilemma. Excessively strict regulation risks infringing on free expression, while overly lenient oversight can allow the spread of misinformation, hate speech, and other harmful content. Thus, a key challenge for social media platforms is finding ways to uphold the authenticity and diversity of information while protecting freedom of speech.

6 Conclusion and discussion

6.1 Conclusion

For urban planning, how to carry out effective and fair public participation needs to be widely and fully discussed. There are two key points. Firstly, it is necessary to recognise the contradictions in public participation, identify the important factors influencing public participation and then improve the policies and mechanisms. Secondly, it is important to open up avenues of participation and break down barriers to information. It can be done through the newly emerging social media for information collection and planning assessment.

The Guangzhou banyan tree incident reveals that the banyan trees themselves were cut down and relocated in order to create an environmentally friendly city due to their inherent problems. However, significant changes to the urban environment can challenge the wellbeing of residents and the emotional connection of individuals to their place (Bai et al., 2024b). The felling of the banyan trees changed local residents’ reliance on the environment and the continuation of their cultural memories. Ultimately triggering mass discontent. Guangzhou residents’ emotional expression of the banyan tree exploded on online social media. Posted online by individuals or organisations. Creating a common ideology and civil society movement (Kumar and Thapa, 2015). Some Guangzhou residents were attached to the banyan tree and felt sorry and dissatisfied when it was cut down. But others are simply using social media as a window to vent their discontent with society and the government (Kowalik, 2021). Or based on social events to rub heat to get personal purpose behaviour. Based on the Internet is worth thinking about how much real emotional input.

In terms of theoretical approach, this paper highlights social media as an effective tool for overcoming institutional barriers to public participation in China, offering valuable insights and practical implications for related research fields. As an innovative platform for information sharing and interaction, social media reduces the barriers to public engagement and diversifies channels for expression. This is particularly impactful in domains like urban governance and ecological protection, where it addresses limitations in traditional public participation mechanisms. Additionally, the paper identifies place attachment as a pivotal factor influencing public participation. Place attachment reflects the deep emotional connection residents establish with the natural, cultural and historical characteristics of their environment. This bond not only enhances their awareness of local issues, but also motivates active involvement in urban planning and management processes. By integrating the concept of place attachment, this paper expands the theoretical framework of public participation, introducing an emotional dimension to engagement mechanisms. It provides a foundation for developing more inclusive, interactive and sustainable public participation policies, offering both theoretical and practical contributions to future urban planning initiatives.

In terms of planning practice, as a public policy with strong implementation and externalities (XU et al., 2022). All parties have the right to discuss and express their positions. Therefore, exploring practical and useful participation channels, breaking down the communication barriers between different groups, conducting multi-dimensional and multi-level information collection and planning evaluation should become an important research topic in the field of public participation in urban planning in the future.

6.2 Discussion

But with the rising public awareness of citizens, the improvement of public participation system and more channels for effective participation. Public policies such as urban planning may face controversy more and more frequently. Therefore, for addressing the issue of public participation in urban planning, the following recommendations are proposed:

• Cities should establish online platforms to facilitate public participation, enhancing the procedural and transparent nature of engagement.

• Governments need to improve their responsiveness to public involvement by refining feedback mechanisms and ensuring that reasonable public demands are addressed in a timely manner.

• Leverage big data and advanced recognition software to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of public participation, improving the scientific basis of planning decisions.

• Emphasize residents’ emotional factors, fully understanding and respecting their emotional attachment and place identity in urban spaces. Ensure that residents’ emotional needs are adequately considered in the planning process to increase recognition and acceptance of the plans.

• Strengthen awareness campaigns and educational efforts to cultivate a modern sense of civic responsibility. Thereby enhancing the rationality and legitimacy of public participation.

Through these comprehensive measures, public participation in urban planning can be effectively promoted, advancing the goal of achieving high-quality public engagement. It is recommended that city managers take the people’s emotions into account when formulating urban planning policies. Also accelerate the construction of improved systems, mechanisms and technologies for social media public participation to achieve the goal of high-level public participation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

YO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing–original draft. XB: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the reviewers for their insightful comments on the early version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the paper was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aalbers, C. B. E. M., and Sehested, K. (2018). Critical upscaling. How citizens’ initiatives can contribute to a transition in governance and quality of urban greenspace. Urban For. and Urban Green. 29, 261–275. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2017.12.005

Afzalan, N., and Muller, B. (2014). The role of social media in green infrastructure planning: a case study of neighborhood participation in park siting. J. Urban Technol. 21, 67–83. doi:10.1080/10630732.2014.940701

Amado, M. P., Santos, C. V., Moura, E. B., and Silva, V. G. (2010). Public participation in sustainable urban planning.

Bai, X., and Li, Y. (2024). The temporal and spatial changes in official facilities in Dali under the bureaucratization of native officers. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng., 1–21. doi:10.1080/13467581.2024.2399691

Bai, X., Xu, D., and Sun, X. (2024a). A study on the changes of cultural and educational facilities in Dali City during the Ming and Qing dynasties. City Built Enviro 2, 10. doi:10.1007/s44213-024-00034-3

Bai, X., Zhou, M., and Li, W. (2024b). Analysis of the influencing factors of vitality and built environment of shopping centers based on mobile-phone signaling data. PLoS ONE 19, e0296261. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0296261

Budruk, M., Thomas, H., and Tyrrell, T. (2009). Urban green spaces: a study of place attachment and environmental attitudes in India. Soc. and Nat. Resour. 22, 824–839. doi:10.1080/08941920802628515

Buijs, A., Hansen, R., Van der Jagt, S., Ambrose-Oji, B., Elands, B., Lorance Rall, E., et al. (2019). Mosaic governance for urban green infrastructure: upscaling active citizenship from a local government perspective. Urban For. and Urban Green. 40, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.06.011

Chang, K., Chen, H., and Hsieh, C. (2022). Effects of relational capital on relationship between place attachment and resident participation. Community and Appl. Soc Psy 32, 19–41. doi:10.1002/casp.2531

Chapin, F. S., Mark, A. F., Mitchell, R. A., and Dickinson, K. J. M. (2012). Design principles for social-ecological transformation toward sustainability: lessons from New Zealand sense of place. Ecosphere 3, 1–22. doi:10.1890/ES12-00009.1

Chen, K., and Zhang, X. (2011). Trial by media: overcorrection of the inadequacy of the right to free speech in contemporary China. Crit. Arts 25, 46–57. doi:10.1080/02560046.2011.552207

Chen, W., Zhao, M., Tang, T., Wang, D., Xie, C., and Cui, Q. (2021). Mechanisms influencing residents’ environmental responsibility behavioural intention in a national park community. For. Econ. 43, 5–20. doi:10.13843/j.cnki.lyjj.20210428.001

Cheung, L. T. O., and Hui, D. L. H. (2018). Influence of residents’ place attachment on heritage forest conservation awareness in a peri-urban area of Guangzhou, China. Urban For. and Urban Green. 33, 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.05.004

Cui, Z. (2016). Problems and their countermeasures of Ficus spp. application in the gardens of Guangzhou City. South. Agric. 10, 82–83. doi:10.19415/j.cnki.1673-890x.2016.15.047

Dargan, L. (2009). Participation and local urban regeneration: the case of the new deal for communities (NDC) in the UK. Reg. Stud. 43, 305–317. doi:10.1080/00343400701654244

Deng, Y., and Wang, X. (2019). Public participation in urban green space management and maintenance - a case study of tannerspree park. Chin. Gard. 35, 139–144. doi:10.19775/j.cla.2019.08.0139

Farinosi, M., Fortunati, L., O’Sullivan, J., and Pagani, L. (2019). Enhancing classical methodological tools to foster participatory dimensions in local urban planning. Cities 88, 235–242. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.11.003

Fornara, F., Scopelliti, M., Carrus, G., Bonnes, M., and Bonaiuto, M. (2020). “Place attachment and environment-related behavior,” in Place attachment (London: Routledge).

Friedmann, J. (2005). Globalization and the emerging culture of planning. Prog. Plan. 64, 183–234. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2005.05.001

Hajer, M., and Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: achievements, challenges, perspectives. J. Environ. Policy and Plan. 7, 175–184. doi:10.1080/15239080500339646

Halla, T., and Laine, J. (2022a). To cut or not to cut – emotions and forest conflicts in digital media. J. Rural Stud. 94, 439–453. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.07.019

Halla, T., and Laine, J. (2022b). To cut or not to cut – emotions and forest conflicts in digital media. J. Rural Stud. 94, 439–453. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.07.019

Jaśkiewicz, M. (2015). Place attachment, place identity and aesthetic appraisal of urban landscape. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 46, 573–578. doi:10.1515/ppb-2015-0063

Jim, C. Y. (2003). Protection of urban trees from trenching damage in compact city environments. Cities 20, 87–94. doi:10.1016/S0264-2751(02)00096-3

Jones, M. (2007). The European landscape convention and the question of public participation. Landsc. Res. 32, 613–633. doi:10.1080/01426390701552753

Kaltenborn, B. P., and Bjerke, T. (2002). Associations between landscape preferences and place attachment: a study in røros, southern Norway. Landsc. Res. 27, 381–396. doi:10.1080/0142639022000023943

Kowalik, K. (2021). Social media as a distribution of emotions, not participation. Polish exploratory study in the EU smart city communication context. Cities 108, 102995. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102995

Kumar, R., and Thapa, D. (2015). Social media as a catalyst for civil society movements in India: a study in Dehradun city. New Media and Soc. 17, 1299–1316. doi:10.1177/1461444814523725

Kuo, H.-M., Su, J.-Y., Wang, C.-H., Kiatsakared, P., and Chen, K.-Y. (2021). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior: the mediating role of destination psychological ownership. Sustainability 13, 6809. doi:10.3390/su13126809

Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Li, B., and Liu, C. (2018). Emerging selective regimes in a fragmented authoritarian environment: the ‘three old redevelopment’ policy in Guangzhou, China from 2009 to 2014. Urban Stud. 55, 1400–1419. doi:10.1177/0042098017716846

Li, C., Weng, S., and Pang, R. (2021). Health assessment of 14 commonly used landscape trees in Guangzhou. J. Northwest For. Coll. 25, 203–207.

Li, Z., and Yang, Y. (2016). Implications of street tree construction for social governance in Guangzhou during the early Republic of China. Soc. Gov. 5, 121–129. doi:10.16775/j.cnki.10-1285/d.2016.05.020

Lin, Y. (2022). Social media for collaborative planning: a typology of support functions and challenges. Cities 125, 103641. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2022.103641

Lo, A. Y., and Jim, C. Y. (2015a). Community attachment and resident attitude toward old masonry walls and associated trees in urban Hong Kong. Cities 42, 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.09.006

Lo, A. Y., and Jim, C. Y. (2015b). Community attachment and resident attitude toward old masonry walls and associated trees in urban Hong Kong. Cities 42, 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.09.006

Lo, A. Y., and Jim, C. Y. (2015c). Protest response and willingness to pay for culturally significant urban trees: implications for Contingent Valuation Method. Ecol. Econ. 114, 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.012

Luo, Z., and Zhuang, X. (2004). Application of Ficus spp. in lingnan gardens. Guangdong Gard. 3, 30–33.

Manzo, L. C., and Perkins, D. D. (2006). Finding common ground: the importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. J. Plan. Literature 20, 335–350. doi:10.1177/0885412205286160

Martí, P., Serrano-Estrada, L., and Nolasco-Cirugeda, A. (2019). Social Media data: challenges, opportunities and limitations in urban studies. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 74, 161–174. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2018.11.001

Marwick, A. E., and boyd, danah (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media and Soc. 13, 114–133. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313

Milton, K. (2003). Loving nature: towards an ecology of emotion. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203421413

Morrison, N., and Xian, S. (2016a). High mountains and the faraway emperor: overcoming barriers to citizen participation in China’s urban planning practices. Habitat Int. 57, 205–214. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.08.001

Morrison, N., and Xian, S. (2016b). High mountains and the faraway emperor: overcoming barriers to citizen participation in China’s urban planning practices. Habitat Int. 57, 205–214. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.08.001

Niu, Q., and Dong, Z. (2017). A planning public engagement method based on mobile social platform. Planner 33, 46–51.

Phillips, C., and Atchison, J. (2020). Seeing the trees for the (urban) forest: more-than-human geographies and urban greening. Aust. Geogr. 51, 155–168. doi:10.1080/00049182.2018.1505285

Reed, M. S., Vella, S., Challies, E., de Vente, J., Frewer, L., Hohenwallner-Ries, D., et al. (2018). A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? a theory of participation. Restor. Ecol. 26, S7–S17. doi:10.1111/rec.12541

Scannell, L., and Gifford, R. (2010). The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 30, 289–297. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.010

Shao, P., and Wang, Y. (2017). How does social media change Chinese political culture? The formation of fragmentized public sphere. Telematics Inf. 34, 694–704. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.018

Soini, K., Vaarala, H., and Pouta, E. (2012). Residents’ sense of place and landscape perceptions at the rural–urban interface. Landsc. Urban Plan. 104, 124–134. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.10.002

Tang, P., Wang, S., and Tao, W. (2021). Temporary home: a case study of a rural–urban migrant family’s homemaking practices in Guangzhou, China. Mobilities 16, 843–858. doi:10.1080/17450101.2021.1922202

Ujang, N., and Zakariya, K. (2015). The notion of place, place meaning and identity in urban regeneration. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 170, 709–717. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.073

von Wirth, T., Grêt-Regamey, A., Moser, C., and Stauffacher, M. (2016). Exploring the influence of perceived urban change on residents’ place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 46, 67–82. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.03.001

Wang, Z., and Xiang, Q. (2020). The influence and divergence of landscape perception and place attachment on residents’ perceptions of cultural compensation. Econ. Geogr. 40, 220–229. doi:10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2020.05.024

Weng, S. (2020). A study on the classification and stratification of public participation in urban planning decision-making. J. Wuhan Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 22, 61–68.

Wu, A., and Lin, G. (2018). Exploring the influencing factors of place attachment among urban park users - a case study of Liuhua Lake Park and Zhujiang Park in Guangzhou City. Chin. Gard. 34, 88–93.

Xu, Y., Cong, Y., and Wei, L. (2022). Observation and inspiration of planning disputes from the perspective of discourse analysis: a case study base on dispute over renewal of hubei ancient village in shenzhen. South Archit. 01, 18–25.

Yang, H. (2019). Aesthetic exploration of banyan tree cultural landscape in southern guangdong--taking lijiao ancient village in Guangzhou as an example. J. Guangzhou City Vocat. Coll. 13, 1–7.

Yang, X., Mao, Q., Gao, W., and Song, C. (2019). Reflections on third-party professional forces to help urban renewal public participation - a case study of Hu Bei renewal. Urban Plan. 43, 78–84.

Yang, X., Song, C., and Mao, Q. (2018). Institutional innovation of planning public participation from the “120 Plan” incident. Planner 34, 130–135.

Ye, Y., Xu, P., and Zhang, M. (2017). Social media, public discourse and civic engagement in modern China. Telematics Inf. 34, 705–714. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.021

Yu, J. (2013). Problems and solutions for public participation in the “we media” era——a case study of 2012 major group events. J. Shanghai Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 30, 1–8.

Yu, W. (2021). A review of the evolution and development of “place” theory in China. Geogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 37, 100–105+113.

Zhang, J., Bi, K., Wu, C., Huo, L., Deng, J., and Sun, L. (2020a). Study on the occurrence pattern of pests and diseases of Ficus spp. in Guangzhou. Garden 9, 8–14.

Zhang, L., Lin, Y., Hooimeijer, P., and Geertman, S. (2020b). Heterogeneity of public participation in urban redevelopment in Chinese cities: Beijing versus Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 57, 1903–1919. doi:10.1177/0042098019862192

Zhao, J., Li, X., Xing, J., and Cai, J. (2022). Public participation in the construction of auckland botanic garden in New Zealand. Chin. Gard. 38, 44–49. doi:10.19775/j.cla.2022.10.0044

Zhao, M., Lin, Y., and Derudder, B. (2018). Demonstration of public participation and communication through social media in the network society within Shanghai. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 45, 529–547. doi:10.1177/2399808317690154

Zhou, Z., Zhang, J., and Wang, Z. (2021). Reconstruction of public participation system in territorial spatial planning: a deduction and analysis based on the theory of communicative action. Urban Plan. 45, 83–91.

Zhu, Y., and Fu, Q. (2017a). Deciphering the civic virtue of communal space: neighborhood attachment, social capital, and neighborhood participation in urban China. Environ. Behav. 49, 161–191. doi:10.1177/0013916515627308

Keywords: urban planning, public participation events, democratic decision-making, emotional factors, place attachment

Citation: Ouyang Y and Bai X (2025) Social media for public participation in urban planning in China based on place attachment-- a case of the Guangzhou banyan tree incident. Front. Built Environ. 10:1523576. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2024.1523576

Received: 09 November 2024; Accepted: 12 December 2024;

Published: 06 January 2025.

Edited by:

Wei Lang, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Hasim Altan, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi ArabiaShiqi Chen, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Danhong Fu, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2025 Ouyang and Bai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaohe Bai, dTIyMDkyMTIwNDYzQGNpdHl1Lm1v

Yifei Ouyang

Yifei Ouyang Xiaohe Bai

Xiaohe Bai