- Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction and City Development (EiABC), Addis Ababa University (AAU), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

This article explores into the relationship between urban morphology and renewable energy, specifically focusing on the potential for active solar and wind energy in building facades and non-built-up spaces within blocks in Addis Ababa, a typical Sub-Saharan Africa city. The study involved the analysis of eleven urban blocks representing four different urban morphology typologies selected with geospatial clustering. Solar and wind data are obtained from satellite-based and meteorological sources. Wind and solar analyses are conducted using computational fluid dynamics through Ansys Fluent and Rhino Grasshopper in Ladybug, respectively, with the support of ArcGIS. The findings reveal that the changes in the values of some morphological descriptors have inverse relationship when comparing solar and wind potential on building facades. Conversely, changes in the values of other morphological descriptors generally show a direct relationship independently on solar and wind potential on the non-built up space. It is recommended that the combined effects of solar and wind potential on urban facades be considered based on morphological descriptors. Similarly, the independent effects of solar and wind potential on non-built-up spaces should also be recommended according to these descriptors.

Introduction

A significant shift in the energy sector is necessary to effectively address global concerns such as energy security, energy access, sustainable development, and climate change in this century (IEA, 2009). The risk of shortages of fossil fuels and their effects on climate change, indicate once again the importance of renewable energy. The only energy resources that could be considered as sustainable were those that would be available forever and had zero or very low impacts (Elliott, 2007). Renewable energy, with its low carbon footprint, rapid deployability in both developed and developing communities, and its potential to create new businesses and green jobs, is a crucial component of the transition to a “Green Economy” (ICLEI, UNEP, UN-Habitat, 2009).

A growing number of cities worldwide have established renewable energy targets, with a strong concentration in Europe and North America. However, developing countries, particularly those in Africa, are better positioned to afford technological leapfrogging toward renewable energy due to their lack of dependence on existing energy infrastructure, resulting in lower costs. For cities to develop sustainable and climate-resilient energy systems, renewables should play a central role (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2020). In Ethiopia, the absence of access to modern, clean, and environmentally sustainable energy services is a critical constraint on economic growth and sustainable development (Guta et al., 2015). Addis Ababa Capital Region accounts for 42% of the total power demand in Ethiopia at peak demand. The power distribution loss in Addis Ababa is estimated to be between 20% and 22.7%, surpassing the international standard of 12%–13% (Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc, 2017). Moreover, some substations and distribution equipment in Addis Ababa are over 30–40 years old and have deteriorated, the provision of efficient and highly reliable power is unfeasible (Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc, 2017).

The integration of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind into the local land use and built environment within cities can provide valuable energy services (ICLEI, UNEP, UN-Habitat, 2009). Solar energy is expected to become the most widely used form of renewable energy for buildings and cities in the coming decades, even though it is not the most energy-productive (Elliott, 2007). Studying the development pattern and buildings’ morphology of a city is essential for understanding the potential impact of solar energy harvested by buildings’ facades and roofs (Kanters and Horvat, 2012; Kanters et al., 2014; Sarralde et al., 2015; Lobaccaro and Frontini, 2014; Amado and Poggi, 2014; Morganti et al., 2017). Other researchers have also expressed similar views (Cheng et al., 2006; Montavon, 2006; Li et al., 2015; Martins et al., 2016; Salvati et al., 2017; Natanian et al., 2019; Poon et al., 2020). Additionally, the city’s morphology, including building height and arrangement, can impact wind flow direction and speed, influencing the potential gain of wind energy (Oke, 1987; Stankovic et al., 2009; Beller, 2011; Yin et al., 2014; Kuspa, 2007; Micallef and Bussel, 2018; International Renewable Energy Agency, 2020). Similar research has also supported this argument (Lu and Ip, 2009; Wang et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015; Juan et al., 2022).

Ongoing attempts in research related to urban solar energy study are reviewed as follow. Morganti et al. (2017) developed urban morphology indicators to identify solar availability on façades which is influenced by the morphology of the urban context. Kanters and Horvar, (2012) performed annual solar irradiation analysis in order to develop guideline. Amado and Poggi (2014) have applied methodology to plan the correct orientation and form of new buildings to guarantee the optimal efficiency of photovoltaic roof and façade systems and calculate their solar energy production. Amado and Poggi (2014) had again developed a five-step methodology to study solar potential. Lobaccaro and Frontini, (2014) developed a new solar urban planning approach for building densification and preservation in existing urban areas. Kanters et al. (2014) performed exploration of geometrical forms of urban blocks and the potential of solar energy to the local production of energy. Sarralde et al. (2015) analyzed different possible scenarios of urban morphology and variables of urban form are tested with the aim of increasing the solar energy potential of neighborhoods.

The utilization of wind turbines in urban settings is primarily in the research and development stage. Recent studies suggest that vertical-axis turbines show great promise for urban use, as they can generate power from the turbulent and multidirectional winds found in cities (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2020). Although urban wind energy is still in its early stages, the number of projects is increasing and the driving forces behind them are gaining momentum. Continued research efforts in the field of urban wind studies are examined below. Yin et al. (2014) investigated the relationship between wind speed and urban morphology, revealing correlations in various scenarios. Kuspa, (2007) conducted a study in San Francisco to enhance the understanding of wind resources in urban environments through wind tunnel testing, expanding the potential for urban wind energy usage. Oke (1987) and Stankovic et al. (2009) identified the environmental characteristics of wind in an urban canyon based on height-to-width ratio. Beller, (2011) characterized urban wind using a coefficient to determine the roughness length and displacement height of the urban wind profile. Micallef and Bussel (2018) analyzed the results of CFD simulations of the urban wind environment in a GIS to facilitate more informed decisions regarding the placement of urban wind turbines based on expected power production.

Currently, research is underway to investigate the combined potential of wind and solar energy production on a larger scale (Ali et al., 2018; Kuznetsov et al., 2021; Burhan et al., 2023). Ali et al. (2018) conducted a study to assess the suitability of sites for wind and solar farms in Songkhla, Thailand. However, there are still gaps in understanding how wind and solar energy can be integrated in the built environment. This research aims to address this gap by examining the urban morphological response to the combined use of wind and solar energy. In light of global sustainable energy demands, this article examines the morphological typologies of Addis Ababa city to better comprehend the impact of solar radiation and wind speed on the active energy potential of building facades and non-built-up spaces. To date, there has been no research conducted on the relationship between morphology and renewable energy potential in the context of Addis Ababa. Given the strong interrelation between building outlines and open spaces, this study considers facades and open spaces. Additionally, this article explores how building envelopes respond to solar irradiation and sun paths within the urban morphology, as well as how wind behavior within urban blocks can be leveraged for maximum energy production. The combined effect of these two active energy sources on urban morphology is also investigated.

Material and method

Description of the study areas and selection procedure

Addis Ababa, a city in Sub-Saharan Africa, serves as the capital of Ethiopia and is situated in the eastern part of the continent. It is positioned at an average altitude of 2,500 m above sea level, with coordinates of 90 N latitude and 390 E longitude. The city has experienced unplanned growth, resulting in the emergence of diverse micro-dynamic elements throughout, despite ongoing efforts to regulate development through planning interventions. Encompassing over 53,000 ha, Addis Ababa has evolved as a low-rise and low-density settlement, characterized by seemingly haphazard building heights and block arrangements. While certain areas have experienced increased density and the development of medium-rise structures, a sense of disorder still persists (Addis Ababa City Planning Project Office, 2017; Office for the Revision of the Addis Ababa Master Plan, 2002; Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, 2011a; Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, 2011b).

The power demand in Addis Ababa is projected to quadruple between 2014 and 2034, primarily due to population growth and development plans. Challenges in providing efficient and reliable power stem from high demand, aging power supply equipment, frequent outages, and high distribution loss. However, given the city’s tropical location, there is potential for solar and wind energy exploitation. Ethiopia’s average annual irradiance is estimated at 5.2 KWh/m2/day, with seasonal variations ranging from 4.5 KWh/m2/day in July to 5.6 KWh/m2/day in February and March (Shanko et al., 2009). Additionally, Ethiopia possesses substantial wind resources, with wind speeds ranging from 7 to 9 m/s and an estimated wind energy potential of 10,000 MW.

The representative urban blocks for active urban solar and wind energy potential are sampled after doing optimized outlier analysis using Arc GIS to identify high to low clusters excluding non-significant values. This is important for typical Sub-Saharan cities that have haphazard development pattern to find suitable urban forms for the study. All building data in the city from G + 1 to G + 52 considered. The buildings have been categorized into four height ranges: G + 1 to G + 3, G + 4 to G + 7, G + 8 to G + 12, and G + 13 to G + 21 + designated as typologies A, B, C and D respectively (see Figure 1). After completion of the analysis with geospatial clustering (see Figure 1, right), the sampled urban blocks are selected based on combination of the following criterion.

• Morphological typologies

• Orientation for solar: N-S/E-W and NE-SW/NW-SE

• Solar irradiation based on location

• Wind direction: NE, E and SW

• Wind speed: low speed within inner city and medium speed outskirt

Based on the criteria eleven sampled urban blocks are taken for this study from four morphological typologies (see Figure 1, left) following geospatial clustering result. Seven sample blocks from typology A are chosen from suburb and intermediate zones, which are mainly characterized by regularly planned low-rise residential areas. Two sample blocks from typology B are a mix of regularly and irregularly developed parts of the intermediate and inner zones, where mid-rise commercial and residential blocks are predominant. One sample block from typology C is selected from high-rise irregularly developed commercial city centers, while one sample block from typology D is chosen from regularly planned high-rise residential suburb areas.

Research design and procedure

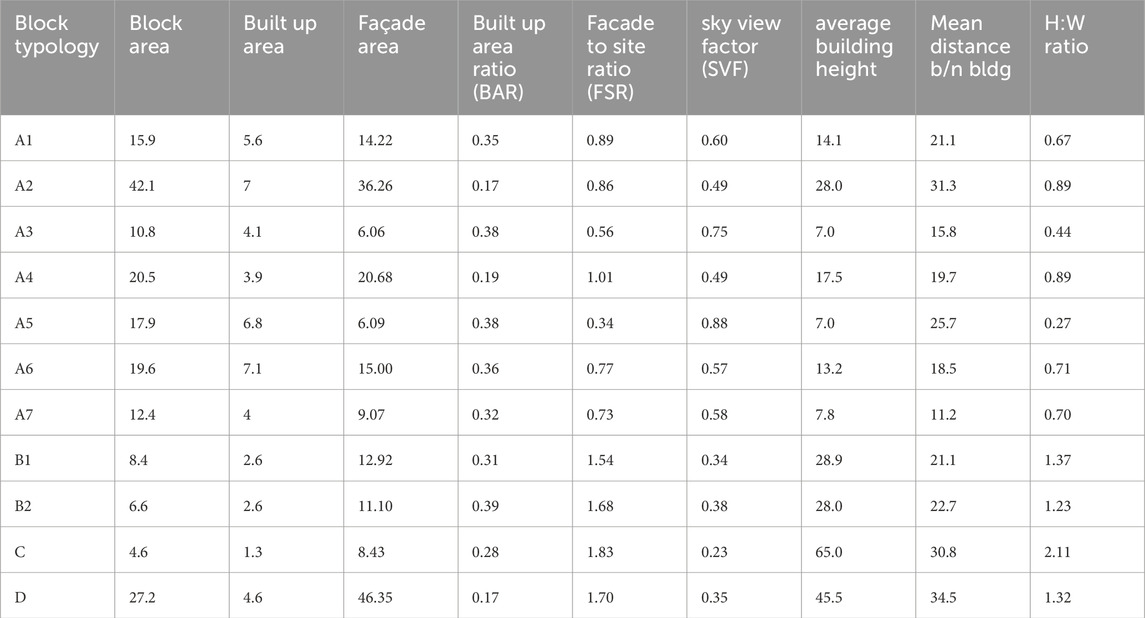

The hypothesis to be tested pertains to how the facades of buildings and the non-built-up spaces interact with solar irradiation and wind speed within the urban environment, with the goal of maximizing solar and wind energy capture. The independent variables are morphological typologies with their corresponding descriptors such as built-up area ratio (BAR), facade to site ratio (FSR), sky view factor (SVF), average building height, mean distance between buildings, and height to width ratio (H:W). The dependent variables are solar and wind energy potential obtained based on the change in the listed descriptor.

The research obtained solar and wind data from meteorological and satellite-based sources. Meteorological data was used for precise, high-frequency verification of specific areas, while satellite data provided a broader, long-term analysis of larger areas. Combining both types of data is advantageous, allowing for correlation and adaptation of the satellite model to the specific site of interest (Syngellakis and Traylor, 2007). The first option relies on data from the Ethiopian Meteorological Agency, which includes long-term information on wind speed, direction, solar irradiance, and sunshine hours from 2011 to 2021 at a local station in Bole International Airport, Addis Ababa. The second option utilizes wind and solar data from the Global Wind Atlas (GWA) and Global Solar Atlas (GSA) respectively. These resources are free, web-based tools designed to help policymakers, planners, and investors identify areas with high wind or solar resources for energy generation around the world, and conduct initial calculations (https://energypedia.info/wiki/).

Wind analysis is conducted using CFD with Ansys Fluent, a fluid simulation software. Each urban block is modeled using Rhinoceros before performing the analysis. Ansys Fluent is a versatile computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software used to simulate fluid flow, heat and mass transfer, chemical reactions, and more (Author anonymous, 2024). The wind speed and direction data are obtained from GWA, representing the mean wind speed for the 10% windiest area. Additionally, the speed is compared with the 10-year meteorological annualized mean speed for validation. A two-dimensional analysis at a height of 10 m on the horizontal plane where the wind intersects with the buildings is done for horizontal wind flow. For building blocks lower or higher than this height, wind speed is calculated using the common logarithmic expression of wind shear, derived from the 10 m high mean speed, as per the equation adopted from AWS Truepower (2010). Similarly two-dimensional wind analysis in vertical planes for wind profile is done along prevailing wind direction with reference wind speed at 200 m height using user defined function, UDF.

The analysis of solar data for the sampled blocks is carried out using Rhino Grasshopper with the Ladybug plugin. Ladybug enables visualization and examination of weather data within Grasshopper, including the presentation of charts depicting sun movement, radiation analysis, shadow studies, and image analysis (https://rhino3d.online/en/product/ladybug). The solar radiation and sun hours utilized by Grasshopper are sourced from an epw (EnergyPlus Weather file), which is a standard EnergyPlus format containing data for over 2,100 locations in 100 countries worldwide (Author anonymous, 2015). The outcome is cross-referenced with the Global Solar Atlas’s results of annual solar irradiance in KWh/m2/day for DNI, GHI, and DIF (DHI) using an equation adapted from Todorova, 2018.

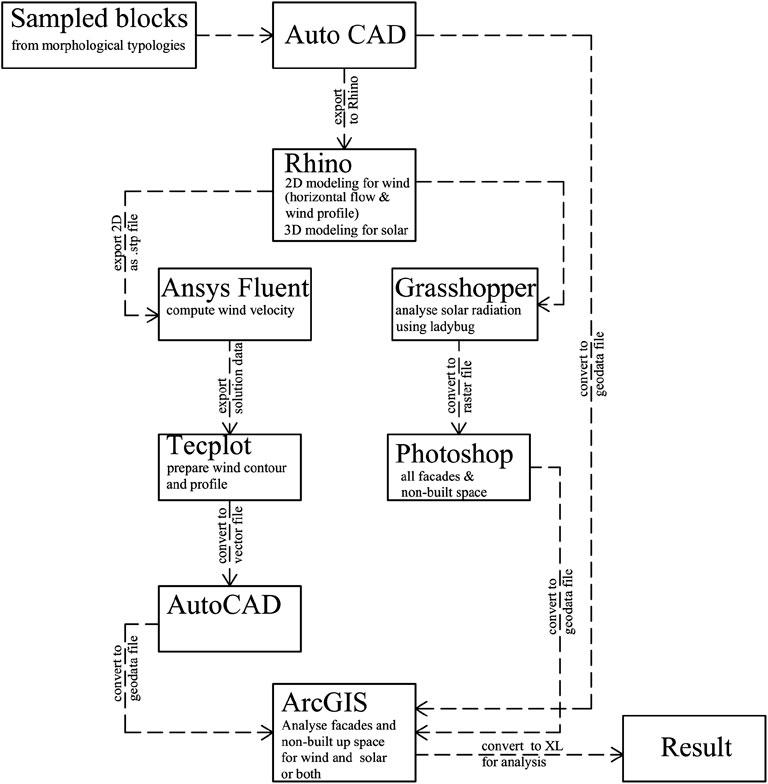

Due to number of variables the research design goes through broad process as describe in Figure 2 showing research design flow chart.

Results

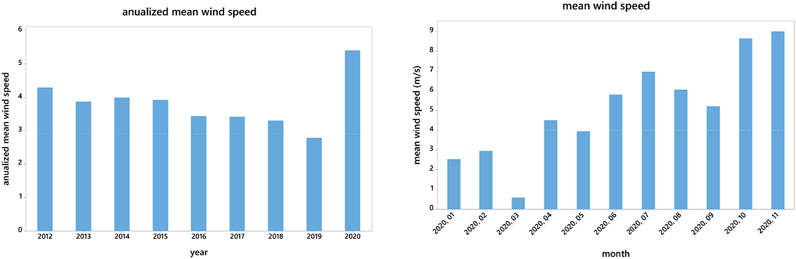

Analyzing wind and solar data on sampled urban blocks from satellite-based data and meteorological data

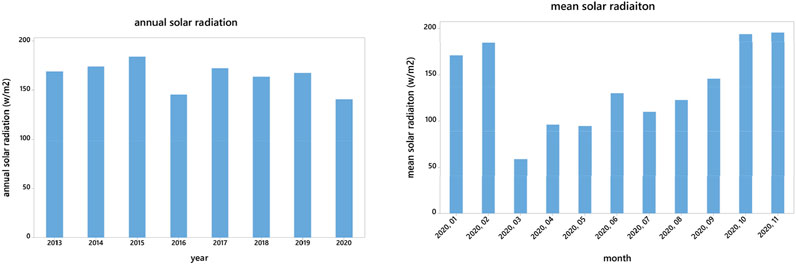

Table 1 presents the average wind speed and annual solar radiation data obtained from GWA and GSA. The wind profile extracted from GWA reveals that wind displacement is higher, and wind speed decreases as we move from planned low-rise residential areas in the suburb (typology A) to areas with mid-rise commercial and residential blocks (typology B) and finally to areas with high-rise irregularly developed commercial centers in the city center (typology C). Figure 3 displays the mean wind speed and annualized mean wind speed from the EMA station at Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, along with mean solar radiation data. According to GWA, the average wind speed at eleven selected study areas at 10 and 100 m height is 2.45 m/s and 4.33 m/s, respectively. The computed mean wind speed from the EMA station at an open airport field is 5.11 m/s annually. Considering the impact of roughness factors due to urban structure, the GWA data is used for this study. GSA indicates that the annual average DNI of the 11 sites is 1734 kWh/m2 per year. The calculated mean annual solar radiation from EMA data is 1,445 kWh/m2 per year as analyzed from Figure 4.

Figure 3. Annualized mean wind speed for 2020 (left) and mean wind speed of nine successive years (right).

Figure 4. Annual mean solar radiation for 2020 (left) and mean solar radiation of eight successive years (right).

Analyzing wind and solar energy potentials on sampled urban blocks

The analysis of wind energy potential involves a comprehensive process that starts with summarizing wind characteristics on sampled urban block typologies. The selected urban sampled block clusters are exported from AutoCAD to Rhino, where geometrically simplified blocks and boundary domains are edited to suit the wind environment in the horizontal plane for horizontal flow at specified mean speed and vertical plane for wind profile up to 200 m height. For the horizontal wind flow, the Rhino file in horizontal plane is exported as a “. step file” to ANSYS for fluent analysis. For the wind profile, Rhino file in vertical plane is exported as a “. step file” to ANSYS for fluent analysis. The solution data from ANSYS is exported to TECPLOT, and the wind mesh is then exported as a vector file to DXF and AutoCAD for calculating the length of building lines and height of façade lines intercepted by wind above specified mean speed, as well as to determine the non-built-up area between blocks above specified mean speed. Finally, the results are exported to GIS, and the Geodata file is transferred to XL for further analysis of:

• percentage of façade area above specified mean wind speed

• percentage of non-built-up space between blocks above specified mean wind speed

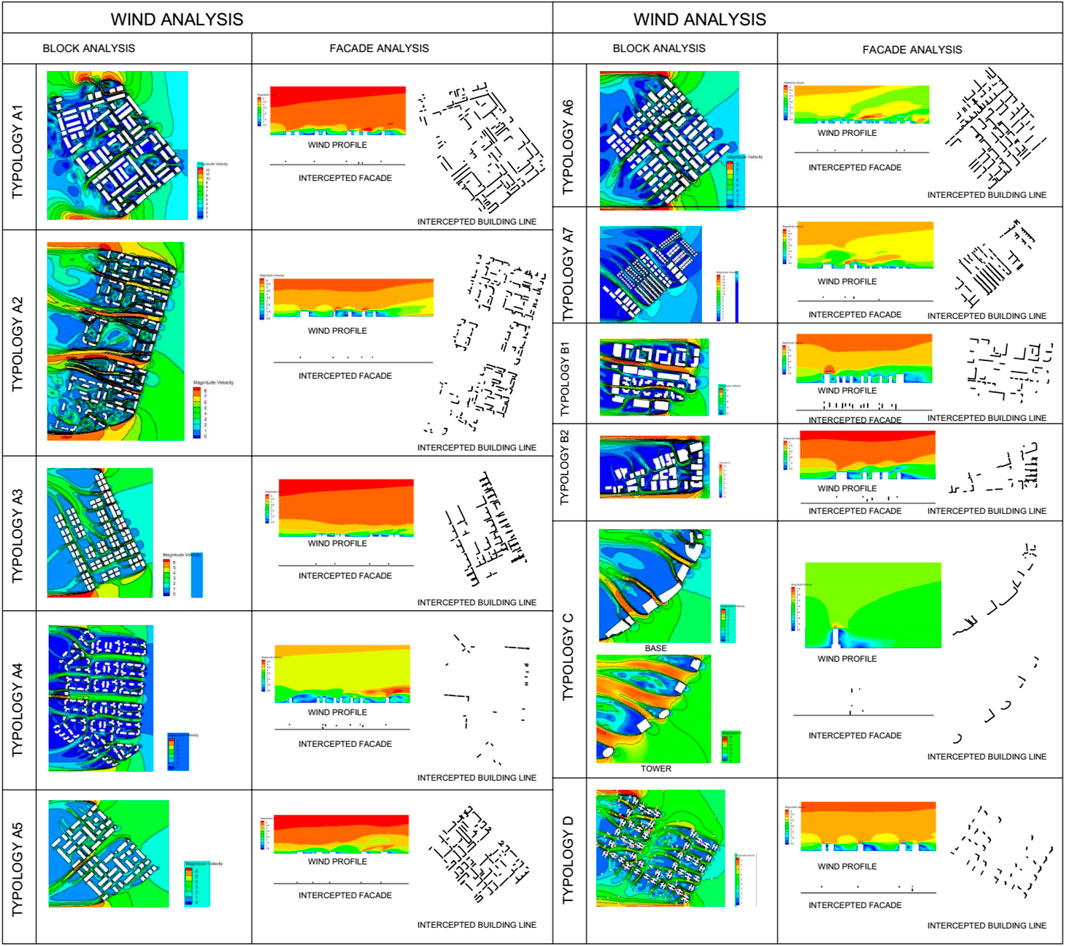

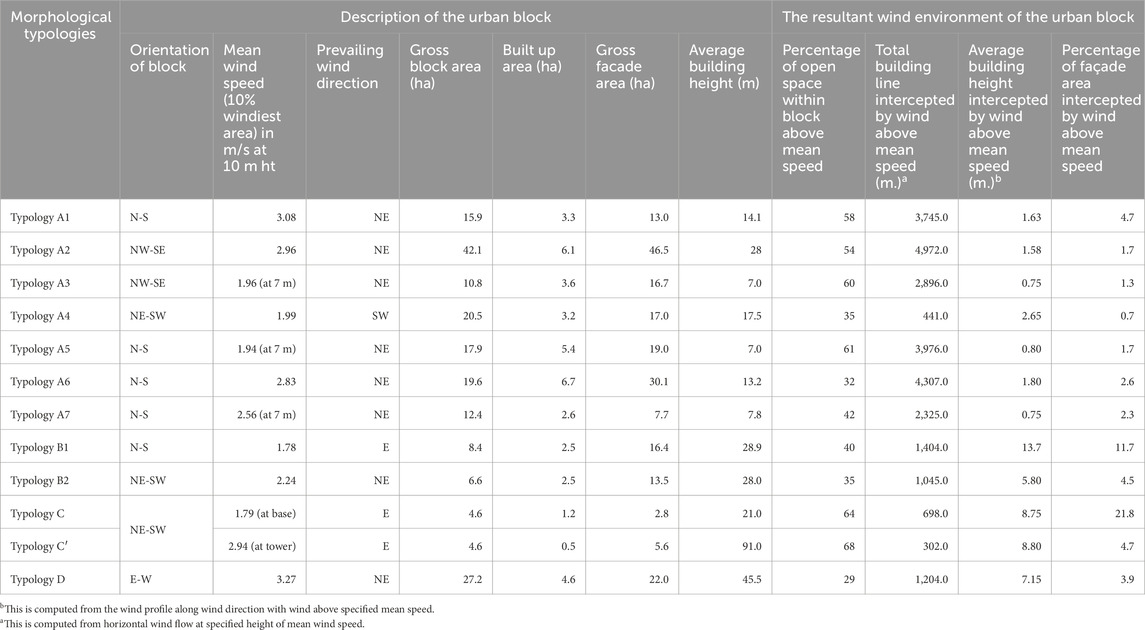

In Figure 5, the wind contour and building lines intercepted by the prevailing wind direction in horizontal plane are depicted. The diagram makes it evident that facades aligned normal to the wind direction have fewer building lines within blocks compared to facades at an angle to the wind, as seen in typologies A4, B1, and B2, which experience more turbulent wind flow on the leeward side as opposed to the windward side. Similarly the wind profile diagram shows more disturbed wind profile in between blocks and increased speed at the edges as building height increased from low-rise suburb area to high-rise within city center as seen in typologies B1, B2, C, and D. Upon analyzing the summarized data in Table 2, which illustrates the resultant wind characteristics of the urban block, it is observed that the percentage of facade area intercepted above a specified mean wind speed increases from low-rise building aggregates to high-rise building aggregates, regardless of other factors such as building orientations in relation to the prevailing wind direction and the specified mean wind speed of the blocks. Upon considering the logical sampling based on wind direction and block alignment, it is found that urban blocks facing the wind direction approximately normal receive less coverage of facades suitable for wind than blocks angled to the wind direction, with average results of 4.7% and 5.4% respectively. Conversely, blocks oriented normal to the wind direction offered more non-built-up space suitable for wind compared to blocks at an angle, with average results of 49% and 44% respectively.

Figure 5. Result of wind analysis from Ansys Fluent for horizontal wind flow and vertical wind shear.

Table 2. Summary showing description of resultant wind environment in terms of percentage of open spaces and facades intercepted by wind above specified mean wind speed.

The horizontal wind flow diagram in Figure 5 shows how building lines intersect with the prevailing wind direction. It is clear that buildings with facades perpendicular to the wind have fewer obstructions within blocks compared to buildings with facades at an angle to the wind, like typologies A4, B1, and B2. The latter experience more turbulent wind flow on the leeward side rather than the windward side. On the vertical wind flow diagram, as the building height increases wind speed at the top edges and on facades increases mostly.

The analysis of solar energy involves a specific process that begins with summarizing solar data and sampling block typologies. After extracting the chosen urban sampled blocks cluster from AutoCAD drawings to Rhino, the blocks are then modeled in three dimensions. The solar radiation analysis is carried out in Rhinoceros using the Ladybug plugin. The solar radiation on the facades and ground surface is analyzed separately, and the resulting baked raster image is exported to ArcGIS. In ArcGIS, the raster image (a “. tiff file”) is reclassified, converted to a polygon, and split by attribute. The attribute is then exported to Excel, where each envelope element is analyzed to calculate:

• percentage of façades area (east, west, north, south and all facades) above and below the average radiation

• percentage of open/non built up space between blocks above and below the average radiation

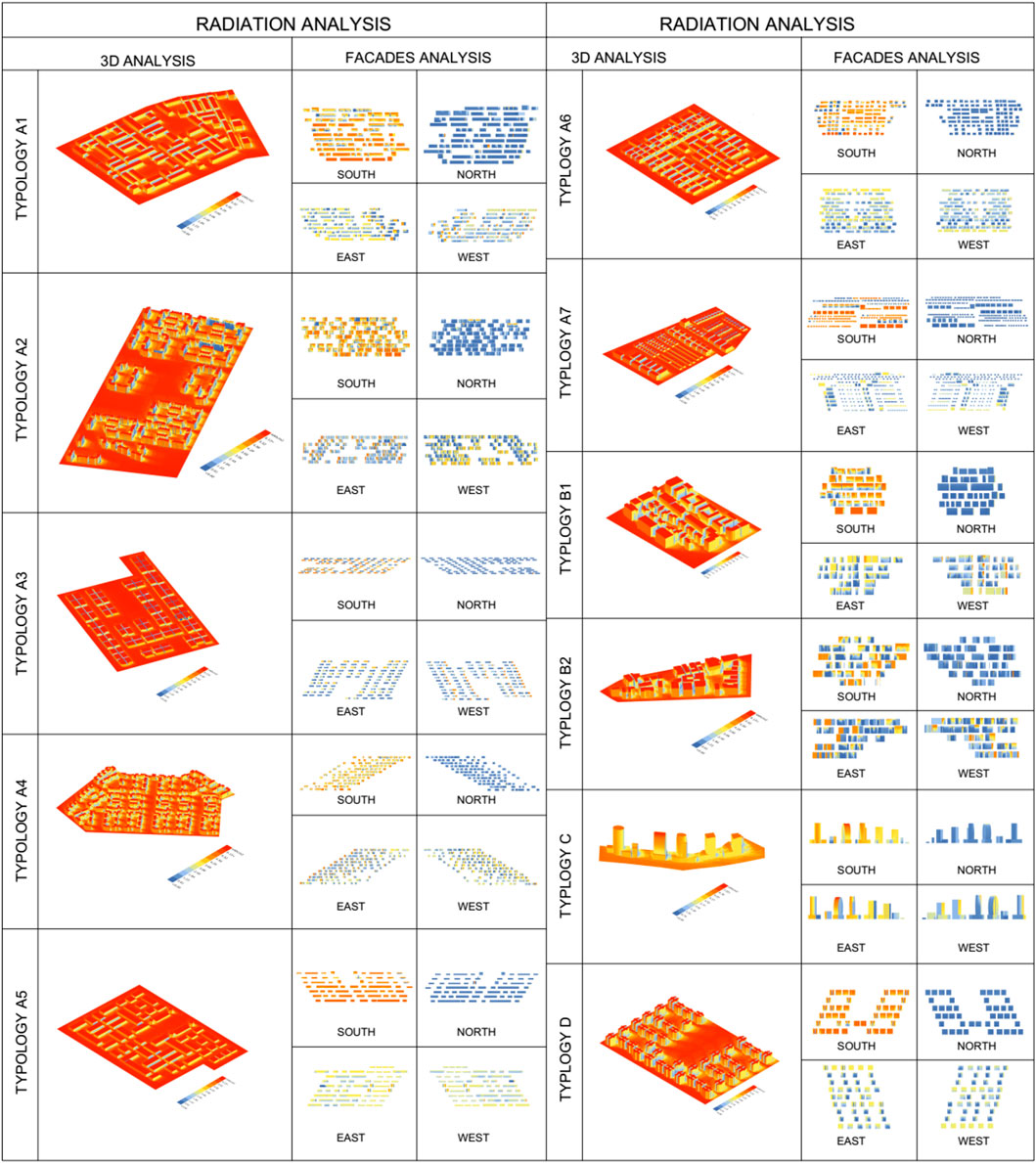

The data presented in Figure 6 indicates that as building height increases, solar radiation on building facades increases while solar radiation on non-built-up space between buildings decreases. Upon analysis of the summarized Table 3, it is evident that south-facing facades receive the highest percentage of solar radiation, followed by east, west, and north facades in succession. When considering a balanced mix of sample blocks based on solar orientation and built-up density, it becomes apparent that blocks with a north-south/east-west orientation receive more radiation on the facade than northeast-southwest/northeast-southeast urban blocks, with average results of 39% and 34% respectively. This is attributed to the potential for direct radiation from the east and west. Conversely, urban blocks with northeast-southwest/northwest-southeast direction receive more solar radiation on non-built-up space between blocks than north-south/east-west oriented blocks, with an average result of 65% and 59% respectively. This is due to the possibility of solar access through an angled building layout to the ground surface.

Figure 6. Result of 3D and façade analysis of sampled block typology from Grasshopper Ladybug plug-in.

Table 3. Summary showing description of the resultant solar irradiation of the urban block below and above average result.

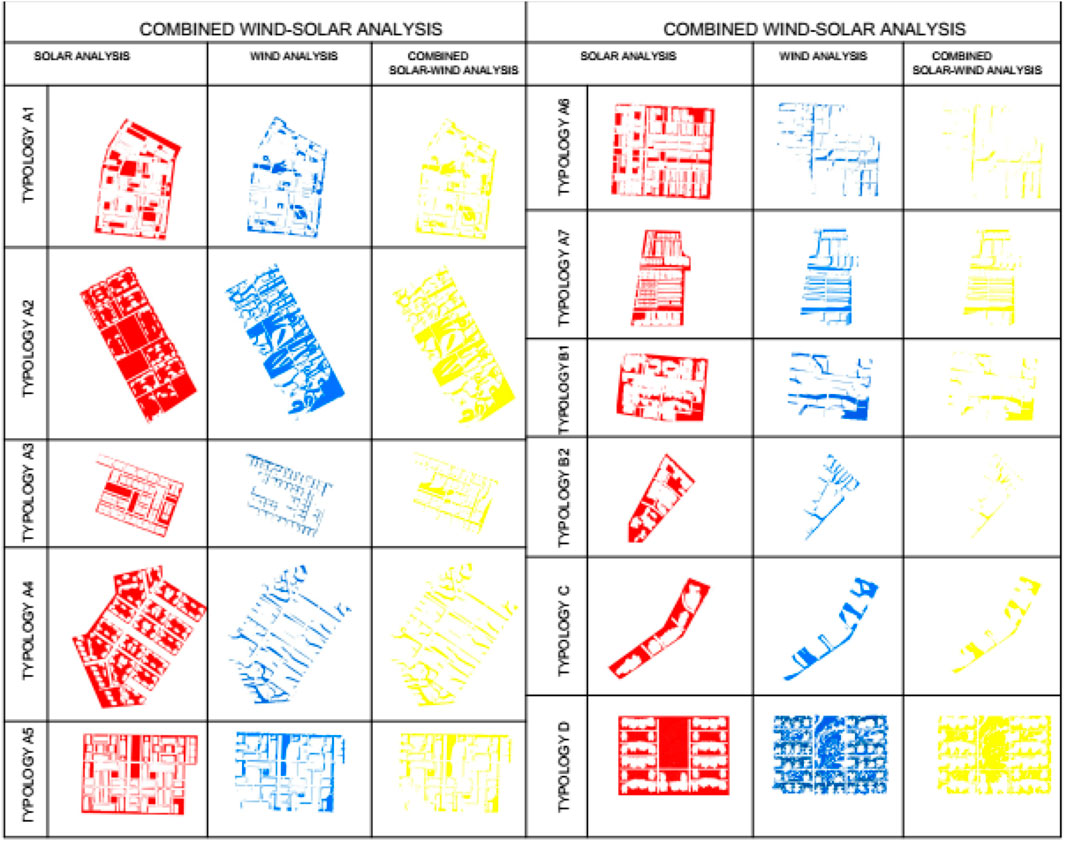

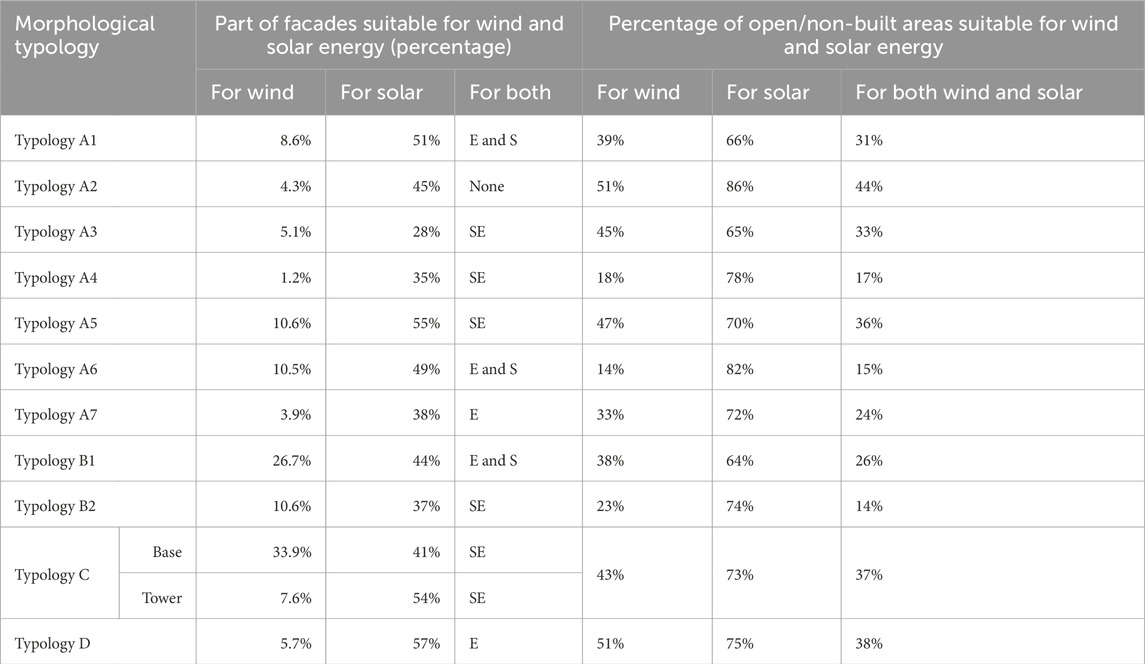

The combined effect of solar and wind suitability is analysed. Figure 7 shows the resulting suitable areas for wind, solar, or both. To assess the potential for wind and solar energy, the previous tables have been further refined to determine the percentage of open/non-built areas suitable for wind and solar, or both. From Table 4, we can see that low-rise residential suburbs and intermediate zones have 35%, 74%, and 29% suitable non-built areas for wind, solar, and both; mid-rise mixed areas in intermediate and inner zones have 31%, 69%, and 20%; high-rise commercial areas within the city centre have 47%, 73%, and 37%; and high-rise residential suburbs have 51%, 75%, and 38% for wind, solar, and both, respectively. It is important to note that roads have been excluded from these calculations on non-built up space. Those facades that face solar orientation and wind direction are considered for façade calculation.

Table 4. Summary of typology of blocks’ non-built up area and façade suitable for wind, solar or both.

The analysis of wind and solar energy potential on urban block facades has been further developed from previous data to determine the percentage of suitable areas. After examining the typologies of urban blocks in Table 4, it was found that low-rise residential areas in the suburbs and intermediate zones have 6.3% and 43%, mid-rise mixed areas in intermediate and inner zones have 18.7% and 41%, high-rise commercial areas in the city centre have 20.8% and 34%, and high-rise residential areas in the suburbs have 5.7% and 57% suitable areas for wind and solar energy, respectively. It is important to note that further refinement may be necessary to exclude openings, windows, and other architectural features.

Discussion

The hypothesis being tested is how building facades and the space in between respond to solar irradiation and wind speed within the urban morphology to maximize solar and wind energy gain. Eleven urban blocks for active urban solar and wind energy potential have been selected based on criteria such as morphology, orientation, wind direction, and wind speed after performing geospatial clustering throughout the city. From the result, regression analysis conducted in statistical software to study the relationship of percentage of suitable facades and non-built up space for solar and wind energy potential. Some morphological descriptors such as built up area ratio (BAR), facade to site ratio (FSR), sky view factor (SVF), average building height, mean distance between buildings, and height to width ratio (H:W) were analyzed using Arc GIS, XL, and mathematical calculations and the result is summarized in Table 5.

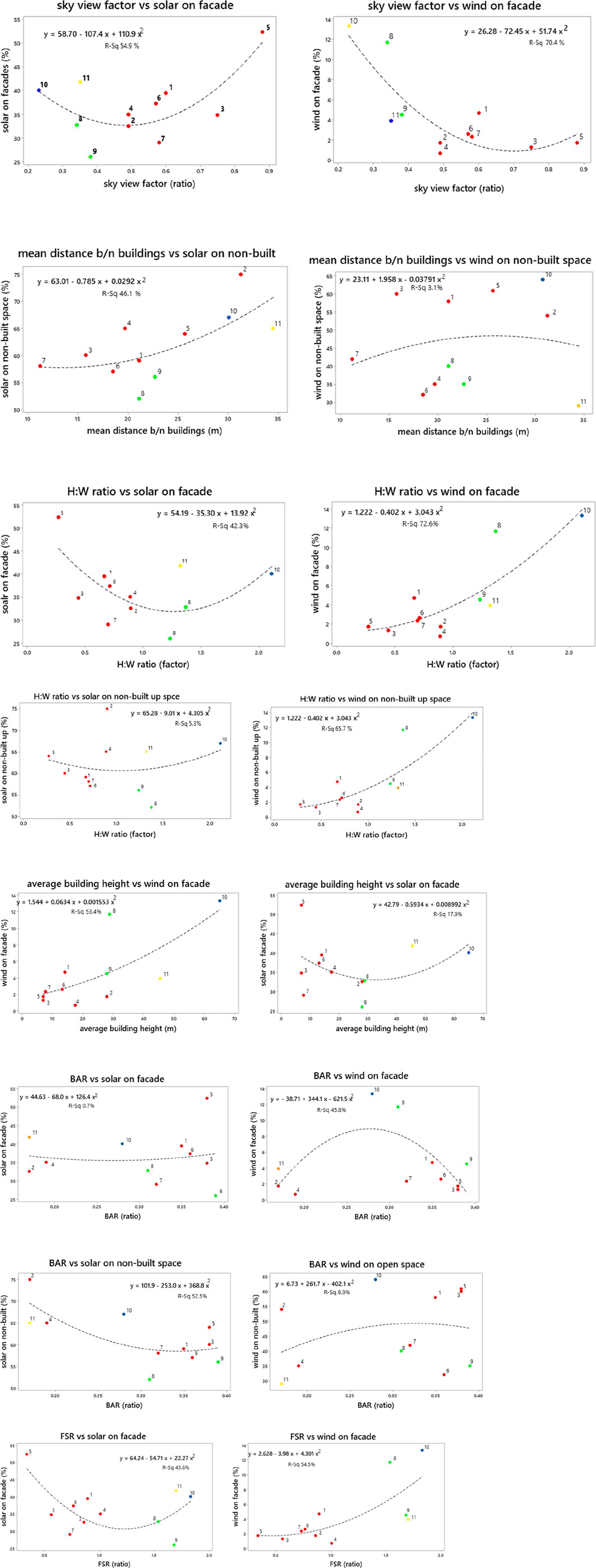

In order to understand the causal relationship between the morphological descriptors and the solar and wind energy potential on facades and non-built up space we used regression analysis as represented in Figure 8. The finding revealed the following pairwise relationships.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on facades with sky view factor are good and much better respectively with R2 value of 54.9% for solar and 70.4% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on non-built spaces with mean distance between buildings are moderate and absent respectively with R2 value of 46.1% for solar and 3.1% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on facades with H: W ratio is moderate and much better respectively with R2 value of 42.3% for solar and 72.6% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on non-built space with H:W ratio are absent and much better respectively with R2 value of 5.3% for solar and 65.7% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on facades with average building height are good and less respectively with R2 value of 53.4% for solar and 17.9% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on facade with BAR are absent and moderate respectively with R2 value of 0.7% for solar and 45.8% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on non-built up space with BAR are good and absent respectively with R2 value of 52.5% for solar and 8.9% for wind.

• The relationship between solar and wind potentials on facade with FSR are moderate and good respectively with R2 value of 43.6% for solar and 54.5% for wind.

Figure 8. Regression analysis between morphological descriptors and solar and wind suitability on facades and non-built up space. 1. Typology A1, 2. Typology A2, 3. Typology A3, 4. Typology A4, 5. Typology A5, 6. Typology A6, 7. Typology A7, 8. Typology B1, 9. Typology B2, 10. Typology C, 11. Typology D.

Among the pairwise comparison that sounds more is discussed as follows. The effect of sky view factor with solar and wind potential on facades is invers. As the SVF increases facades exposure for solar increases but wind speed deceases probably due to lower roughness factor that usually decreases turbulence of wind speed in between blocks. Solar and wind potential on facades with H:W ratio is more or less inverse. As H:W ratio increases facades exposure for solar decreases due to smaller setbacks that can reduce solar access. But more façade surface increases with height which led for more wind-facades intercept. The effect of FSR on wind and solar potential over facades is also inverse. As FSR increases solar access to blocks decreases which could be due to densification. On the contrary wind speed increases due to the dynamic effect of wind with closer setbacks of facades.

On the remaining pair-wise comparison the change in one variable does not necessarily bring a change in the other. For example, the change in mean distance, average building height, BAR and FSR bring effect on one aspect and remained constant on the other. For instance as mean distance between buildings increases solar and wind potential on non-built up space increases and remain constant respectively. As H: W ratio increases solar and wind potential on non-built up space remain constant and increases respectively. As average building height increases solar and wind potential on facades increases and remain constant respectively. As BAR increases solar and wind potential on non-built up space decreases and remain constant respectively.

Conclusion

This article investigates the morphological typologies of Addis Ababa city to better comprehend the impact of solar radiation and wind speed on the active energy potential of building facades and non-built-up spaces. The research concludes by addressing the existent of relationship between morphological descriptors and the combined or independent effect of solar and wind potential directly and inversely. It is noted that as the average building height and mean distance increases from the suburb to the city center (i.e., from typology A through B to C), wind potential on facade and solar potential on non-built up spaces increase respectively. As the H:W ratio and FSR increases from the suburb to the city center (i.e., from typology A through B to C), solar and wind potential on facade will have inverse relationship. To conclude, in the case of urban facades, combining solar and wind energy potential looks recommendable depending on morphological descriptor. On the contrary in the case of non-built-up space, separate solar and wind energy potential is recommendable depending on morphological descriptor. There are limitations as morphological descriptors’ effect on the alignment of urban blocks with solar and wind direction can not better explain even though the effect is complicated that needs further investigation.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

WD: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. TA: Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to edit paragraphs written by the author.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Addis Ababa City Planning Project Office (2017). Addis Ababa city structure plan: summary report (2017-2027). Addis Ababa.

Ali, S., Taweekun, J., Techato, K., Waewsak, J., and Gyawali, S. (2018). GIS based site suitability assessment for wind and solar farms in Songkhla, Thailand. Renew. Energy 132, 1360–1372. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.09.035

Amado, M., and Poggi, F. (2014). Solar urban planning: a parametric approach. Energy Procedia 48, 1539–1548. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.02.174

Author anonymous (2015). Global climate action partnership. Available at: https://globalclimateactionpartnership.org/.

Author anonymous (2024). Getting started with Ansys fluent: basics. Available at: https://innovationspace.ansys.com.

Burhan, M., Montanholi, Y., and Huda, Q. (2023). Hybrid wind-solar energy system for remote locations in Northern Alberta. Arrivet 1, 2023. doi:10.56007/arrivet.v1i1.14

Cheng, V., Steemers, K., Montavon, M., and Compagnon, R. (2006). Urban Form, Density and Solar Potential. Geneve, Switzerland: PLEA 2006

Elliott, D. (2007). Sustainable energy: opportunities and limitations. New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan.

Energypedia (2019). Available at: https://energypedia.info/wiki/Global_Solar_Atlas_(GSA.

Ethiopian Institute of Architecture (2011a) Building construction and city development (EiABC) in Evaluation of the Addis Ababa city development plan (2003-2010): executive summary. Addis Ababa.

Ethiopian Institute of Architecture (2011b) Building construction and city development (EiABC) in Report on building height regulation updating study for Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa.

Guta, F., Damte, A., and Ferede, T. (2015). The residential demand for electricity in Ethiopia. EfD DP 15-07.

ICLEI, UNEP, UN-Habitat (2009). Sustainable urban energy planning: a handbook for cities and towns in developing countries.

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) (2020). Rise of renewables in cities: energy solutions for the urban future. Abu Dhabi: IRENA.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), NEWJEC Inc (2017). Data collection survey on Addis Ababa transmission and distribution system: final report. Ethiopia-EEU, EEP.

Juan, Y. H., Rezaeiha, A., Montazeri, H., Nlocken, B., Wen, C. Y., and Yang, A. S. (2022). CFD assessment of wind energy potential for generic high-rise buildings in close proximity: impact of building arrangement and height. Sci. Appl. Energy 321, 119328. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119328

Kanters, J., and Horvat, M. (2012). Solar energy as a design parameter in urban planning. Energy Procedia 30, 1143–1152. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2012.11.127

Kanters, J., Walla, M., and Dubois, M. (2014). Typical values for active solar energy in urban planning. Energy Procedia 48, 1607–1616. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.02.181

Kuznetsov, P., Rimar, M., Yakimovich, B., Kulikova, O., Lopusniak, M., Voronin, D., et al. (2021). Parametric optimization of combined wind-solar energy power plants for sustainable smart city development. Basel, Switzerland: MDPI, applied sciences.

Ladybug Plug-in for grasshopper. Available at: https://rhino3d.online/en/product/ladybug.

Li, D., Liu, G., and Liao, S. (2015). Solar potential in urban residential buildings. Sol. Energy 111, 225–235. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2014.10.045

Lobaccaro, G., and Frontini, F. (2014). Solar energy in urban environment: how urban densification affects existing buildings. Energy Procedia 48, 1559–1569. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.02.176

Lu, L., and Ip, K. Y. (2009). Investigation on the feasibility and enhancement methods of wind power utilization in high-rise buildings of Hong Kong. Renew. Sustain. energy Rev. 13 (2), 450–461. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2007.11.013

Martins, T. A. L. M., Adolphe, L., Bastos, L. E. G., and Martins, M. A. L. M. (2016). Sensitivity analysis of urban morphology factors regarding solar energy potential of buildings in Brazilian tropical context. Solar energy 137, 11–24. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2016.07.053

Micallef, D., and Bussel, G. (2018). A review of urban wind energy research: aerodynamics and other challenges. Energies 11, 2204. doi:10.3390/en11092204

Montavon, M., Steemers, K., Cheng, V., and Compagnon, R. (2006). La ville radieuse’ by Le corbusier.

Morganti, M., Salvatia, A., Coch, H., and Cecere, C. (2017). Urban morphology indicators for solar energy analysis. Energy Procedia 134, 807–814. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.09.533

Natanian, J., Aleksandrowicz, O., and Auer, T. (2019). A parametric approach to optimizing urban form, energy balance and environmental quality: the case of Mediterranean districts. Appl. Energy 254, 113637. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113637

Office for the Revision of the Addis Ababa Master Plan (2002). Addis Ababa city development plan: executive summary. Addis Ababa.

Oke, T. R. (1987). Boundary layer climates. 2nd edition. Taylor and Francis e-Library, Routledge (an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group. British.

Poon, K. H., Kampf, J. H., Tay, S. E. R., Wong, N. H., and Reindl, T. G. (2020). Parametric study of urban morphology on building solar energy potential in Singapore context. Sci. Urban Clim. 33, 100624. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100624

Salvati, A., Coch, H., and Morganti, M. (2017). Distributed urban energy systems (Urban form, energy and technology, urban hub): effects of urban compactness on the building energy performance in Mediterranean climate. Sci. Energy Procedia 122, 499–504. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.07.303

Sarralde, J. J., Quinn, D. J., Wiesmann, D., and Steemers, K. (2015). Solar energy and urban morphology: scenarios for increasing the renewable energy potential of neighbourhoods in London. Renew. Energy 73, 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2014.06.028

Shanko, M. (2009). Ethiopia’s solar energy market: target market analysis. Editors M. Hankins, A. Saini, and P. Kirai (Berlin, Germany: (Megen Power), IES) GTZ.

Syngellakis, K., and Traylor, H. (2007). Urban Wind Resource Assessment in the UK: an introduction to wind resource assessment in the urban environment. United Kingdom: European Commission.

Todorova, D.Environmental Research Institute (2018). Resource assessment toolkit for solar energy. United Kingdom: GREBE Generating Renewable Energy Business Enterprise.

Wang, B., Cot, L. D., Adolphe, L., Geoffray, S., and Morchain, J. (2015). Estimation of wind energy over roof of two perpendicular buildings. Energy Build. 88, 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.11.072

Wang, B., Cot, L. D., Adolphe, L., Geoffray, S., and Sun, S. (2015). Cross indicator analysis between wind energy potential and urban morphology. Sci. Renew. energy 113, 989–1006. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2017.06.057

Yang, A. S., Su, Y. M., Wen, C. Y., Juan, Y. H., Wang, W. S., and Cheng, C. H. (2016). Estimation of wind power generation in dense urban area. Appl. Energy 171, 213–230. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.03.007

Keywords: solar energy, wind energy, urban morphology, ArcGIS, ANSYS fluent, rhino-grasshopper

Citation: Debebe W and Assefa T (2025) Active solar and wind energy potential of urban morphologies on building facades and non-built-up space in between: a case study in Addis Ababa, a Sub-Saharan Africa city. Front. Built Environ. 10:1506294. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2024.1506294

Received: 08 October 2024; Accepted: 12 December 2024;

Published: 09 January 2025.

Edited by:

Elena Lucchi, Polytechnic University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Sanja Stevanovic, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, SerbiaHasim Altan, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2025 Debebe and Assefa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wondwosen Debebe, d29uZHdvc3Nlbi5kZWJlYmVAZWlhYmMuZWR1LmV0, d29uZGVfZWR1QHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Wondwosen Debebe

Wondwosen Debebe Tibebu Assefa

Tibebu Assefa