94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Built Environ., 07 September 2023

Sec. Indoor Environment

Volume 9 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2023.1218659

Background: Sick building syndrome (SBS) consists of a group of mucosal, skin, and general symptoms temporally that is related to residential buildings of unclear causes. Consequently, a cross-sectional study was carried out to identify the prevalence and contributing factors of SBS in adult people living in Hodan district, Mogadishu Somalia.

Methods: A community based cross sectional study was conducted from September to October 2022 using a convenient sampling to include 261 individuals. The data was collected through structured questionnaire and an observational checklist. SBS was assessed using 15 building-related symptoms and four socio-demographic characteristics. Five SBS conformation criteria were used. Descriptive statistics were presented, while bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the association between the dependent and independent variables.

Results: The prevalence of SBS was 41% from the total of 261 participants. Based on the findings, SBS had a significant association with being female [AOR = 3.044, 95% CI = (1.813, 5.110)], lack of functional windows [AOR = 3.543, 95% CI = (1.293, 9.710)], fungal growth in the buildings [AOR = 3.433, 95% CI = (1.223, 9.638)], recent use of pesticides, paints, and solvents [AOR = 2.541, 95% CI = (1.018, 6.343)], cooking inside building [AOR = 4.709, 95% CI = (1.469, 15.095)], outdoor air pollutant [AOR = 6.364, 95% CI = (2.387, 16.966)], use of charcoal for cooking [AOR = 1.846, 95% CI = (1.013, 3.365)], incensing habits of occupants [AOR = 4.375, 95% CI = (2.303, 8.308)] fan use [AOR = 2.067, 95% CI = (1.099, 3.886)] and dust in the living rooms [AOR = 5.151, 95% CI = (2.380, 11.152).

Conclusion: SBS had a significant association with occupants’ sex, lack of functional windows, fungal growth in the buildings, recent use of pesticides, paints, and solvents, cooking inside the building, outdoor air pollutants, use of charcoal for cooking, incensing habits of occupants, and dust in the living rooms. High prevalence and poor understanding of sick building syndrome could threaten the health status of the occupants. Measures such as mass health education on identifiable risk factors should be taken to cope with these problems.

Housing is one of the elementary requirements of a human being and essential for health. Over 90% of people’s time is spent indoors (Belachew et al., 2018a). Housing is progressively becoming a major public health problem. For many years, housing conditions have been identified as one of the essential settings that affect the health of human beings. During the 1970 s energy crisis, engineers and building managers were compelled to maintain and design the indoor environment more effectively by sealing the buildings. This resulted in a lower ventilation rate to save electricity (Norhidayah et al., 2013). The most significant risk factors for home health are poor indoor air quality, noise, humidity and mold development, interior temperatures, volatile organic compounds (VOC), and a lack of sanitation and hygiene equipment (Burge, 2004). Sick building syndrome (SBS) and building-related illnesses (BRI) are two main categories of building-related problems (Marmot et al., 2006).

The method definition of SBS varies across the literature. However, it is mainly derived from the World Health Organization (WHO) explanation is a term used to describe circumstances in which building occupants experience rapid health effects and comfort issues that appear to be connected to time spent in a building. However, no recognized condition or cause can be recognized (Jafari and Asghar, 2015). SBS is also defined by mucosal, skin and general symptoms directly connected to houses and offices. SBS is characterized by a group of symptoms that have no recognized explanation. These symptoms are separated into mucous membrane symptoms affecting the eyes, nose, throat, and dry skin, as well as what is frequently referred to as general symptoms, such as headache and fatigue (Li et al., 2015a).

The cause of SBS is usually attributed to a number of interacting factors; including Inadequate ventilation/poor indoor air quality, etc. Because of the increased reliance on artificial items and the increase of the time spent in indoors, health problems have recently been linked to indoor environments (Al Momani and Ali, 2008). This rise of SBS overtime is attributable to a variety of factors, including urbanization, a shift in activities from outside to inside events, and an increase in reliance on automobiles. This means that if the space is unhealthy, the people who live there will experience symptoms and pain. The main sources of SBS are believed to be air conditioning systems and pollutants in the atmosphere from both inside and outside the building.

This pollution is subsequently spread throughout the structure, causing enough contaminants such as CO, CO2, VOCs, and particles to be harmful to the Indoor Air Quality (IAQ). Many research has been conducted on indoor air quality (IAQ) as a result of scientists’ growing concern about the consequences of indoor air pollution on health, particularly for persons who spend more time indoors than outside (Vesitara and Surahman, 2019).

Indoor air pollution is the result of a mix of contributions from both outside and inside sources. Air pollution can contribute to high-rise buildings near motorways or industrial estates in some situations. Outside sources enter the building through the windows, doors, and ventilation systems, altering the quality of the internal air. Furthermore, some meteorological conditions can contribute to air pollution in the room (Jafta et al., 2017).

Several studies have shown that the type of ventilation system has an impact on SBS, with the SBS being greater in buildings with mechanical ventilation systems than in buildings with conventional ventilation systems (Norhidayah et al., 2013). The SBS symptoms are common in the general population in Somalia. However, SBS symptoms and their contributing factors are poorly understood, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa including Somalia. The main reason is that Somalia has not had a strong health system and research institutions for over three decades now. As a result, communities either seek care from an expensive private healthcare system, or those who do not afford it, relies on traditional health, mainly spiritual healing. This community-based cross-sectional study was, therefore, conducted to assess prevalence and contributing factors of SBS in Mogadishu.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from September to October 2022 among adults living in the Hodan district Moqadishu Somalia. The data was collected from Bangaaria, Xero-Ruush, and African Village. The Adults (≥18 years) who had been residing in the study area for at least 1 year were includedin the study, while those who declined to participate in or had communication difficulties were excluded from the study.

The study employed single population proportion formula to determine the sample size due to lack of information regarding the total number of individuals in the study population. To our knowledge there is no published research of SBS in Somalia. Therefore, to estimate the prevalence of Sick Building Syndrome, the study relied on the SBS Prevalence data from previous study conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia, where the prevalence (p) was found to be 21.7%. (Belachew et al., 2018b), The formula also considered a standard normal distribution value (z) of 1.96, a margin error (d) of 5% (representing a 95% confidence interval) and the value of Q, which represent (1-p), where p is the estimated prevalence of SBS.

The study employed a convenient sampling technique to select both houses and participants. Data was collected using a structured face-to-face interview questionnaire, which was initially developed in English and then translated into Somali, along with an observational checklist. The questionnaire covered socio-demographic information, housing conditions, and Sick Building Syndrome symptoms.

The primary outcome variable was experiencing at least one housing condition-related symptom within the past year. Participants were asked if they had experienced any general symptoms (i.e., fatigue, headache, dizziness, fever), mucosal symptoms (e.g., dry throat, cough, eye irritation, nose irritation), or skin symptoms (e.g., skin rashes, dry or flushed facial skin, scaling/itching scalp or ears, lip dryness) in the past year. To determine if the symptoms were SBS-related, the following criteria were used: (a) symptoms worsen when at home, (b) symptoms improve or disappear when away from home, (c) symptoms reappear upon returning home, (d) symptoms worsen at night, and (e) symptoms improve when the room is ventilated or cleaned.

The ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Ethical Clearance Committee of the School of Public Health and Research (SPHR) at Somali National University (SNU). Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The data was entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 20). Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage were used to summarize variables. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 from chi-square analysis were imported into multivariable logistic regression analysis. Multicollinearity was tested using linear regression analysis with VIF >5 was considered multicollinearity between predictors. The strength of association between the predictors and the outcome variable (sick building syndrome) was determined using a crude odds ratio (COR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) corresponding to p-value. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

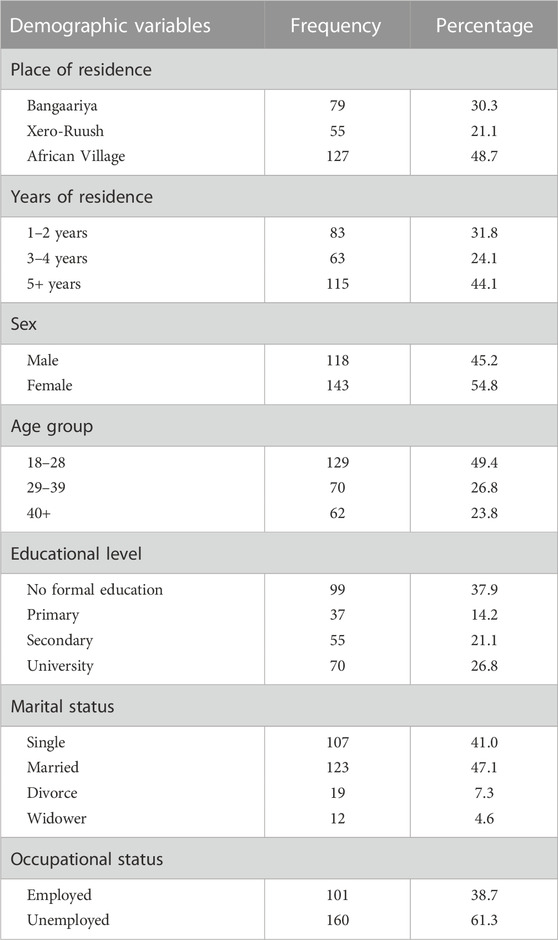

A total of 261 residential buildings were visited to partake in the study, and the respondse rate was 100%. Thus all 261 adults (male and female) residents were included in the survey. 143 (54%) study subjects were female. About half, 129 (49.4%), of the study’s participants ranged in age from 18 to 28 years. Only 37 (14.2%) participants graduated from colleges or universities. The vast majority, almost two-third (61.3%) participants were unemployed. 101 (38.7%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Socio-demographic information of the adult people living in Hodan district in Mogadishu, Somalia, 2022.

The majority, 241 (92.3%), of the study participant lived in residences composed of brick walls, while 20 (7.7%) lived in wood-walled houses. Two hundred twenty-eight (87.4%) of the study participants mentioned that their home’s floor was cement/tiles, and 33 (12.6%) were reported to live earth floor houses. Nearly two-thirds, 171 (65.5%), of the research participants, reported to have functional windows in their residence, and 90 (34.5%) had no functional windows. We observed fungal growth with 73 (28%) of the participants’ houses. A total of one hundred seventy-six (67.4%) of the study members informed that they recently did not use pesticides, paints, and solvents, and the remaining 85 (32.6%) used them recently. Two hundred twenty-eighty (87.4%) members of the study participants reported that not cooking inside the living quarters is common practice, while the remaining partakers practice cooking inside the living quarters. Moreover, Two hundred and eight (79.7%) of the study participants reported that outdoor air pollutant sources (like garages and roads) were not found around their homes, and 53 (20.3%) were found to have these pollutant sources. Two hundred and five (78.5%) of the study participants said that none of their family members smoke cigarettes, while 56 (21.5%) of them have said that at least one member of their family does. More than two-third (68.6%) of the study members use charcoal as an energy source, whereas one-third (31.4%) do not. Incensing and utilization of a joss stick was not a common habit in 136 (52.1%) participants’ houses, while 125 (47.9%) practiced it. The majority, 189 (72.4%), of the study participants reported that they had a fan in their house, whereas 72 (27.6%) had no fan in their houses. Of the study participants, 234 (89.7%) reported using light from electricity, and 27 (10.3%) used other sources. Nearly two-thirds (65.9%) of the study participants complain of dust in their living rooms, whereas one-third (34.1%) do not complain about dust. Two hundred twenty-nine (87.7%) of the study participants resided in residences with an appropriate lightining system, while 32 (12.3%) lived in houses with no adequate lightining system. The majority of the houses of 190 (72.8%) subjects were clean, whereas 71 (27.2%) were not clean (Table 2).

Of 261 participants, 107 reported experiencing one or more symptoms associated with poor housing conditions, resulting in a 41% prevalence of sick building syndrome. The reported symptoms were categorized as mucosal (33%), skin (29.5%), and general symptoms (23.8%). Specific symptoms included eye irritation (28.7%), skin itchiness (22.2%), headache (20.3%), nasal irritation (20.3%), dry throat (18.4%), lip dryness (17.2%), cough (16.5%), fatigue and dry skin (12.3%), ear itching (11.1%), fever (10.7%), and dizziness (10%) (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Prevalence of sick building syndromes among the population in Hodan district in Mogadishu, Somalia.

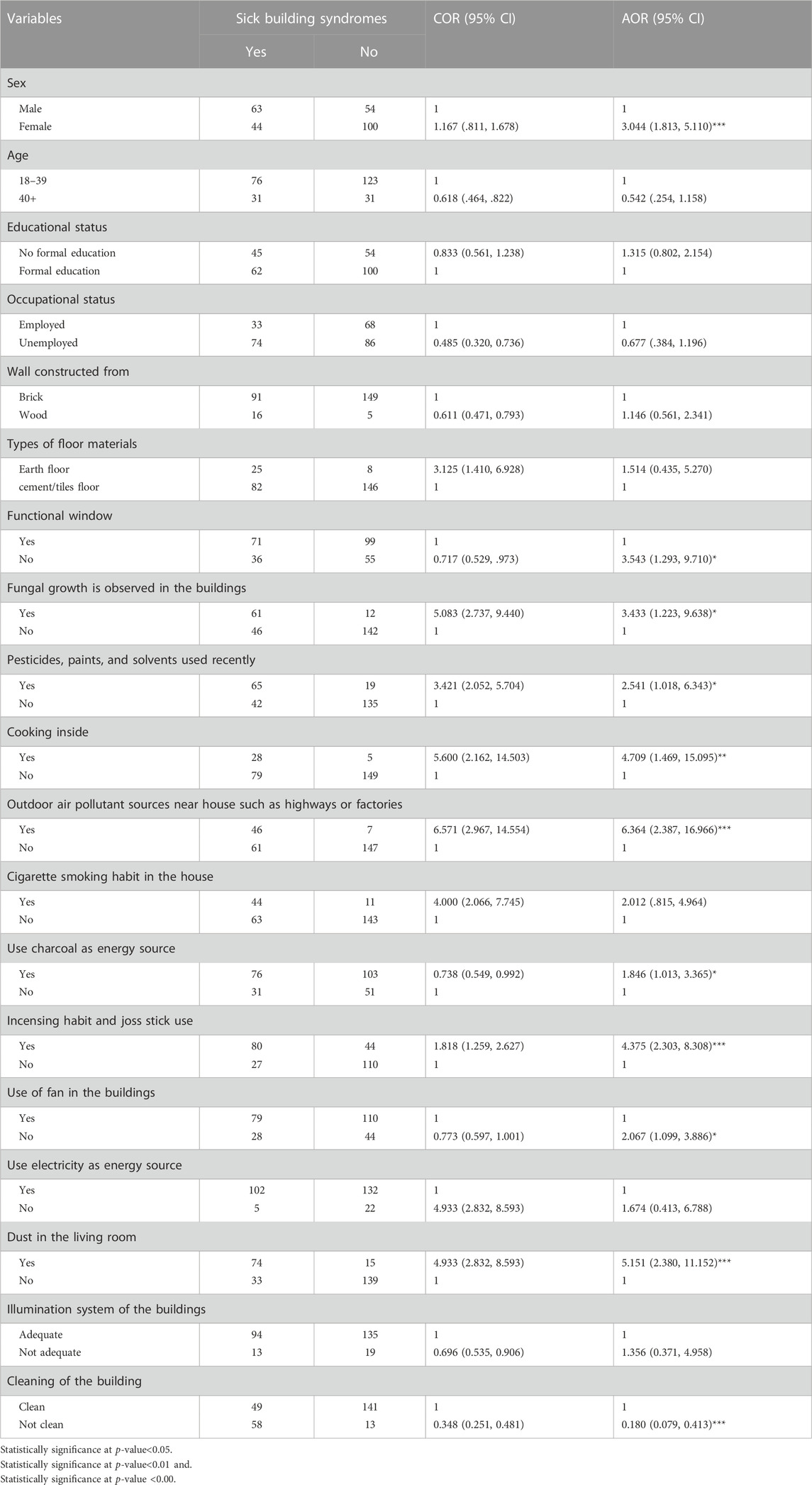

Table 4 demonstrates that factors associated with sick building syndrome (SBS) include sex, functional window status, fungal growth in buildings, recent use of pesticides, paints, and solvents, indoor cooking, proximity to outdoor air pollutants sources like highways or factories, use of charcoal as an energy source, incense and joss stick usage, presence of fans in buildings, utilization of electricity as an energy source, dust in the living room, and building cleanliness.

TABLE 4. Factors associated with sick building syndromes among the adult people living in Hodan district in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Females were three times more likely to develop SBS than males [AOR = 3.044, 95% CL= (1.813, 5.110)]. The prevalence of sick building syndrome was Nearly four times higher among respondents living in buildings without functional windows [AOR = 3.543, 95% CL= (1.293, 9.710)]. The likelihood of experiencing sick building syndrome was more than three times greater for participants living in buildings observed fungal growth [AOR = 3.433, 95% CL= (1.223, 9.638)]. Residents who recently used pesticides, paints, and solvents had a higher risk of having SBS than those who did not use them [AOR = 2.541, 95% CI = (1.018, 6.343)]. Additionally, residents who cooked inside their living spaces had a approximately five times greater chance of developing sick building syndrome than those who did not cook indoors [AOR = 4.709, 95% CL= (1.469, 15.095)].

Residents living in buildings with outdoor pollutants had six times higher odds of developing SBS compared to those without outdoor pollutants [AOR = 6.364, 95% CI = (2.387, 16.966)]. The odds of experiencing SBS were almost two times greater for occupants using charcoal as a cooking energy source than those using gas [AOR = 1.846, 95% CI = (1.013, 3.365)]. The likelihood of having SBS was more than fout times higher among occupants who habitually burn incense and use joss sticks [AOR = 4.375, 95% CI = (2.303, 8.308)]. SBS prevalence was two times higher for participants living in buildings without fan use [AOR = 2.067, 95% CL= (1.099, 3.886)].

The prevalence of sick building syndrome (SBS) was five times higher among residents living in buildings with dust compared to those residing in buildings without dust [AOR = 5.151, 95% CI = (2.380, 11.152)].

The prevalence of SBS in the designated sites in the Hodan district was found to be 41% (95% CI = 35.04%–49.96%), with 33% experiencing mucosal symptoms, 29.5% having skin symptoms, and 23.8% reporting general symptoms. These prevalence rates for mucosal, skin, and general symptoms were higher than those observed in previous studies conducted in China (Wang et al., 2013). Three North European cities, (Sahlberg et al., 2013).

Japan, (Suzuki et al., 2021). These differences may be due to the variance in housing situations, demographic characteristics, sample sizes, and environmental circumstances.

This study found that female participants had a higher prevalence of sick-building syndrome than male participants and this could interprate that the majority of the females stay house way longer than males. According to this study, SBS was statistically related to the availability of functional windows, where as residents without functional windows were nearly four times more likely to have SBS comparing to those have functional windows. Many studies also reported the influence of general ventilation on the health of the residents (Gomzi and Bobić, 2009). This point can be explained by the fact that the presence of functional windows as means of ventilating a building naturally maintenances the external fresh air to the living buildings and eliminates the internal exhausted air, which in turn decreases the amount of contamination with substances or microorganisms so that increased ventilation can be seen as an effective treatment of SBS (Gomzi and Bobić, 2009). SBS was significantly associated with fungus infestation or molds in the living building.

Occupants living in houses where fungal growth was detected reported higher SBS than their counterparts. The finding of this study is supported by other studies (Burge et al., 2015).

This study reported that SBS was associated with household cooking energy sources, cooking practices, and incensing habits of occupants. The prevalence of SBS was higher among occupants who used charcoal as a cooking energy source. Similar other studies by Wang et al. (2013); Lu et al. (2016) found same results. This can be justified that charcoal use and incensing habits are incomplete combustion processes that can generate gracious pollutants. Generally, cooking energy sources and cooking practices are the main sources of gracious pollutants to the indoor air (Zhang et al., 2015).

SBS was also associated with pesticides, paints, and solvents used recently and outdoor air pollutants. Residents who use pesticides, paints, and solvents used recently had nearly three times higher risk to develop SBS. People who lived in buildings with outdoor pollutants such as highways and factories were higher risk to develop SBS than those without outdoor pollutants. These findings were similar to those of (Lu et al., 2016). The current study also showed that fan use in living residences was significantly associated with sick building syndrome. The prevalence of sick building syndrome was higher among respondents who lived in a house without fan use. Other studies also described the same findings (Chen et al., 2016). The ventilation of indoor air quality develops due to fan usage (Yang et al., 2019).

Dust and SBS were significantly associated as well. Residents who lived in buildings with dust were more likely to develop SBS than those respondents who lived in buildings with no dust.

Our study has certain limitations, including, that the research did not employ appropriate instrument to measure indoor air quality, temperature, humidity, and nose level within the residential buildings. Additionally, it is important to note that the study was conducted in older buildings, which may have contributed to a higher prevalence of SBS.

The study revealed a high prevalence of Sick building syndrome (SBS), with 41% of participants experiencing symptoms. The prevalence rate of mucosal, skin, and general symptoms was notably higher than in previous studies reported in the literature.

SBS had a significant association with occupants’ sex, lack of functional windows, fungal growth in the buildings, recent use of pesticides, paints, and solvents, cooking inside the building, outdoor air pollutants, use of charcoal for cooking, incensing habits of occupants, fan use, and dust in the living rooms. Residents living in building without functional windows were nearly four times more likely to be at risk of developing sick building syndrome (SBS) compared to those living in building with functional windows. Furthermore, individuals who cook within their living spaces faced approximately five times greater susceptibility to SBS compared to their counterpart. Additionally, building located in close proximity to outdoor pollution sources had a six-fold higher likelihood of experiencing SBS. On the other hand, individuals who regularly use burning incense and joss stick were four times more likely to be at risk of experiencing SBS.

These findings highlight the importance of addressing various environmental and lifestyle factors to reduce the prevalence of SBS and improve the health and wellbeing of residents in Hodan district and other similar settings. Minister of Public Works Reconstruction and Housing in Somalia should prioritize the development and implementation of national standard for healthy housing and Measures such as mass health education on identifiable risk factors should be taken to cope with these problems.

Futures researchers should focus on sick bulding syndrome in School settings.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

SY played a crucial role in conducting research. He was responsible for handling the research process, GD and AS, the supervisor and co-supervisors, respectively, contributed significantly to the conception and design of the research. MH took charge of data analyzing and presentation. SH contributed to the data collection process and also played a role in drafting the research article, and AG was responsible for developing the final manuscript. He oversaw the integration of all contributions, ensuring the research findings were presented cohesively and in accordance with journal standard.

The publication charge of this manuscript received support from the World Health Organization’s Somalia office and the responsibility of its content lies solely with the authors.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Al Momani, H. M., and Ali, H. H. (2008). Sick building syndrome in apartment buildings in Jordan. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2 (4), 391–403.

Belachew, H., Assefa, Y., Guyasa, G., Azanaw, J., Adane, T., Dagne, H., et al. (2018a). Sick building syndrome and associated risk factors among the population of Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 23 (1), 54–59. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0745-9

Belachew, H., Assefa, Y., Guyasa, G., Azanaw, J., Adane, T., Dagne, H., et al. (2018b). Sick building syndrome and associated risk factors among the population of Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 23 (1), 54. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0745-9

Burge, P. S., Lung, O., and Unit, D. (2015). Sick building syndrome. Occup. Environ. Med. 61 (2), 185–190. March 2004. doi:10.1136/oem.2003.008813

Burge, P. S. (2004). Sick building syndrome. Occup. Environ. Med. 61 (2), 185–190. doi:10.1136/oem.2003.008813

Chen, A., Gall, E. T., and Chang, V. W. C. (2016). Indoor and outdoor particulate matter in primary school classrooms with fan-assisted natural ventilation in Singapore. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23 (17), 17613–17624. doi:10.1007/s11356-016-6826-7

Ghaffarianhoseini, A., AlWaer, H., Omrany, H., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Alalouch, C., Clements-Croome, D., et al. (2018). Sick building syndrome: are we doing enough? Archit. Sci. Rev. 61 (3), 99–121. doi:10.1080/00038628.2018.1461060

Gomzi, M., and Bobić, J. (2009). Sick building syndrome: do we live and work in unhealthy environment? Period. Biol. 111 (1), 79–84.

Jafari, M. J., Asghar, A., Mousavi Najarkola, S. A., Yekaninejad, M. S., Pourhoseingholi, M. A., Omidi, L., et al. (2015). Association of sick building syndrome with indoor air parameters. TANAFFOS 14 (1), 55–62.

Jafta, N., Barregard, L., Jeena, P. M., and Naidoo, R. N. (2017). Indoor air quality of low and middle income urban households in Durban, South Africa. Environ. Res. 156 (3), 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.008

Li, L., Adamkiewicz, G., Zhang, Y., Spengler, J. D., Qu, F., and Sundell, J. (2015a). Effect of traffic exposure on sick building syndrome symptoms among parents/grandparents of preschool children in Beijing, China. PLoS ONE 10 (6), e0128767. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128767

Li, L., Adamkiewicz, G., Zhang, Y., Spengler, J. D., Qu, F., and Sundell, J. (2015b). Effect of traffic exposure on sick building syndrome symptoms among parents/grandparents of preschool children in Beijing, China. PLoS ONE 10 (6), e0128767. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128767

Lu, C., Deng, Q., Li, Y., Sundell, J., and Norbäck, D. (2016). Outdoor air pollution, meteorological conditions and indoor factors in dwellings in relation to sick building syndrome (SBS) among adults in China. Sci. Total Environ. 560–561, 186–196. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.04.033

Marmot, A. F., Eley, J., Stafford, M., Stansfeld, S. A., Warwick, E., and Marmot, M. G. (2006). Building health: an epidemiological study of “sick building syndrome” in the whitehall ii study. Occup. Environ. Med. 63 (4), 283–289. doi:10.1136/oem.2005.022889

Norhidayah, A., Lee, C. K., Azhar, M. K., and Nurulwahida, S. (2013). Indoor air quality and sick building syndrome in three selected buildings. Procedia Eng. 53, 93–98. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2013.02.014

Sahlberg, B., Gunnbjörnsdottir, M., Soon, A., Jogi, R., Gislason, T., Wieslander, G., et al. (2013). Airborne molds and bacteria, microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOC), plasticizers and formaldehyde in dwellings in three North European cities in relation to sick building syndrome (SBS). Sci. Total Environ. 444, 433–440. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.10.114

Suzuki, N., Nakayama, Y., Nakaoka, H., Takaguchi, K., Tsumura, K., Hanazato, M., et al. (2021). Risk factors for the onset of sick building syndrome: A cross-sectional survey of housing and health in Japan. Build. Environ. 202 (4), 107976. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107976

Vesitara, R. A. K., and Surahman, U. (2019). Sick building syndrome: assessment of school building air quality. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1375 (1), 012087. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1375/1/012087

Wang, J., Li, B. Z., Yang, Q., Wang, H., Norback, D., and Sundell, J. (2013). Sick building syndrome among parents of preschool children in relation to home environment in Chongqing, China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 58 (34), 4267–4276. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-5814-2

Yadav, A. K., Ghosh, C., and Banerjee, B. D. (2019). A review on indoor air pollution and associated health impacts with special reference to building designs. Int. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 8 (4), 1–11.

Keywords: prevelence, sick building syndrome, indoor air pollutant, residential building, adults

Citation: Yussuf SM, Dahir G, Salad AM, Hayir T. M M, Hassan SA and Gele A (2023) Sick building syndrome and its associated factors among adult people living in Hodan district Moqadishu Somalia. Front. Built Environ. 9:1218659. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1218659

Received: 27 May 2023; Accepted: 16 August 2023;

Published: 07 September 2023.

Edited by:

Hasim Altan, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Claudio Martani, Purdue University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Yussuf, Dahir, Salad, Hayir T. M, Hassan and Gele. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gallad Dahir, Z2FsbGFkLnNwaHJAc251LmVkdS5zbw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.